Raid Of Holyrood on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Raid of Holyrood was an attack on

Francis Stewart, Earl of Bothwell was a nephew of

Francis Stewart, Earl of Bothwell was a nephew of

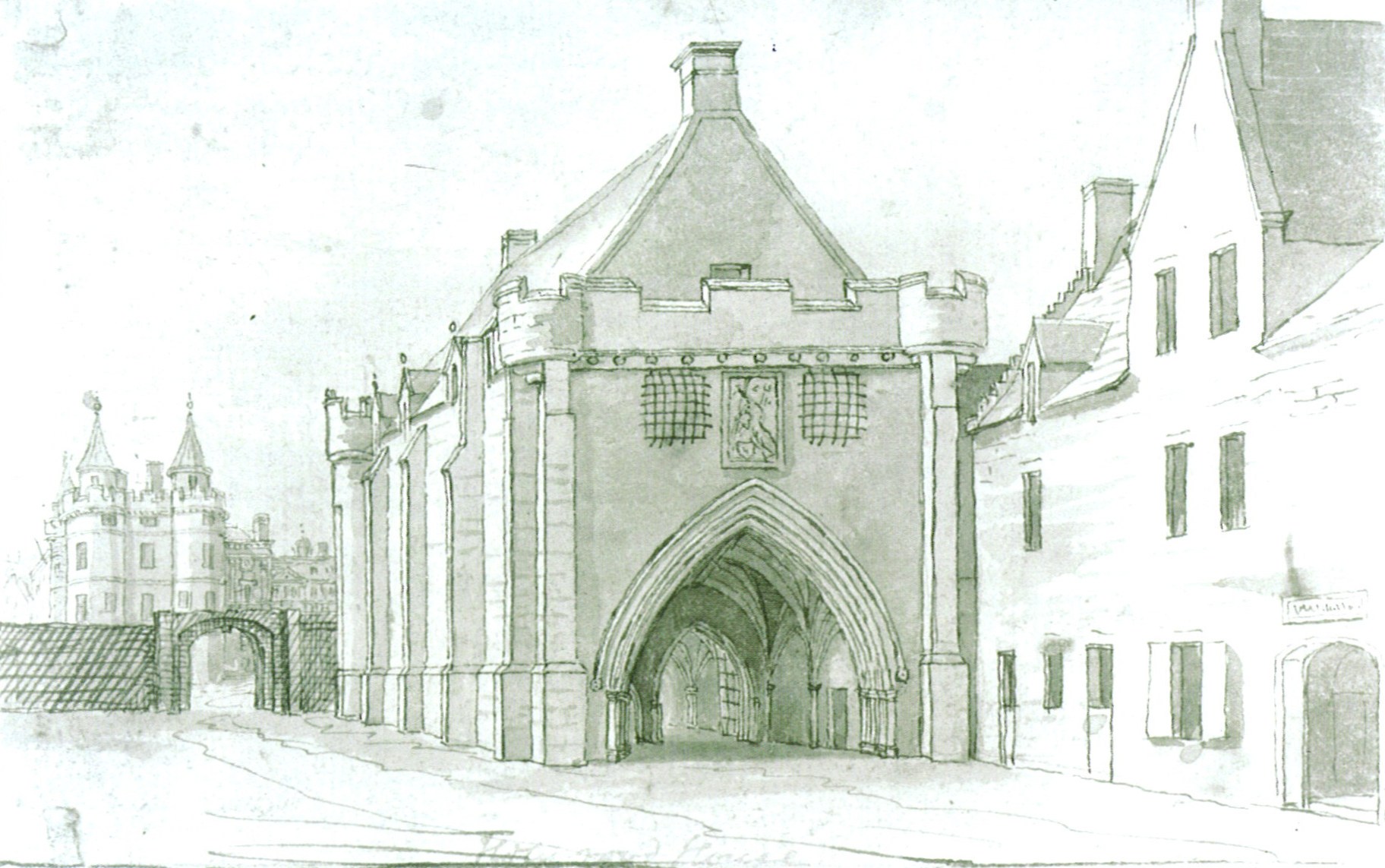

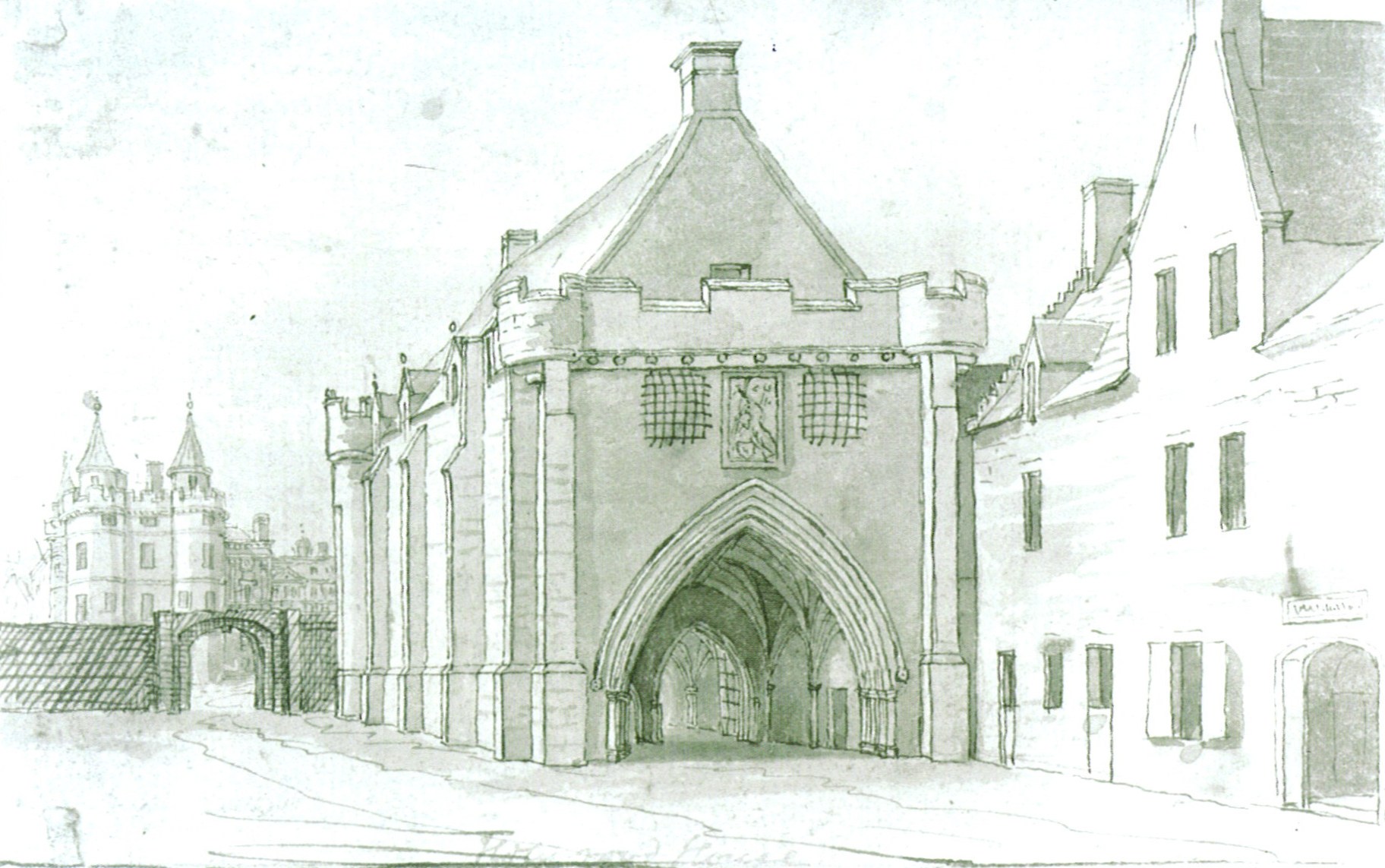

Holyrood Palace

The Palace of Holyroodhouse ( or ), commonly referred to as Holyrood Palace or Holyroodhouse, is the official residence of the British monarch in Scotland. Located at the bottom of the Royal Mile in Edinburgh, at the opposite end to Edinbu ...

, Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

on 27 December 1591 by Francis Stewart, 5th Earl of Bothwell

Francis may refer to:

People

*Pope Francis, the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State and Bishop of Rome

* Francis (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters

*Francis (surname)

Places

* Rural ...

in order to gain the favour of King James VI of Scotland

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until hi ...

.

Background

Francis Stewart, Earl of Bothwell was a nephew of

Francis Stewart, Earl of Bothwell was a nephew of Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legitimate child of James V of Scot ...

. He fell from the favour of James VI and was accused of witchcraft during the North Berwick witch trials

The North Berwick witch trials were the trials in 1590 of a number of people from East Lothian, Scotland, accused of witchcraft in the St Andrew's Auld Kirk in North Berwick on Halloween night. They ran for two years, and implicated over seventy ...

. Expelled from court, he broke into Holyrood Palace

The Palace of Holyroodhouse ( or ), commonly referred to as Holyrood Palace or Holyroodhouse, is the official residence of the British monarch in Scotland. Located at the bottom of the Royal Mile in Edinburgh, at the opposite end to Edinbu ...

(twice) and tried to capture Falkland Palace

Falkland Palace, in Falkland, Fife, Scotland, is a royal palace of the Scottish Kings. It was one of the favourite places of Mary, Queen of Scots, providing an escape from political and religious turmoil. Today it is under the stewardship of ...

(once) and planned to enter Dalkeith Palace

Dalkeith Palace is a country house in Dalkeith, Midlothian, Scotland. It was the seat of the Dukes of Buccleuch from 1642 until 1914, and is owned by the Buccleuch Living Heritage Trust. The present palace was built 1701–1711 on the site of th ...

, either to regain the King's favour or to kidnap him. Bothwell could count on a number of loyal followers amongst the Scottish lairds. Despite his following, he was forced into exile and died in Naples in 1612.

First raid on Holyrood, December 1591

Sir James Melville of Halhill, a gentleman in the household ofAnne of Denmark

Anne of Denmark (; 12 December 1574 – 2 March 1619) was the wife of King James VI and I; as such, she was Queen of Scotland

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the constitutional fo ...

, the courtier Roger Aston

Sir Roger Aston (died 23 May 1612) of Cranford, Middlesex, was an English courtier and favourite of James VI of Scotland.

Biography

Aston was the illegitimate son of Thomas Aston (died 1553), Thomas Aston (died 1553). Scottish sources spell his n ...

, and the English ambassador Robert Bowes, described the first raid on Holyrood Palace. Bothwell came with sixty followers after supper on Monday 27 December 1591, including the lairds James Douglas of Spott

James Douglas of Spott (died 1615) was a Scottish landowner and conspirator.

Career

He was a son of James Douglas, 4th Earl of Morton, the Regent Morton. He was appointed Prior of Pluscarden in 1577 by his father, and given a lease of lead mines ...

, Archibald Wauchope of Niddrie

Archibald Wauchope of Niddrie ( – 1597) Scottish landowner and rebel.

He was the son of Robert Wauchope of Niddrie, who died in 1598, and Margaret Dundas, daughter of James Dundas of Dundas.

He was known as the "Laird of Niddrie, younger". Th ...

, John Colville, and Archibald Douglas (a son of the Earl of Morton

The title Earl of Morton was created in the Peerage of Scotland in 1458 for James Douglas of Dalkeith. Along with it, the title Lord Aberdour was granted. This latter title is the courtesy title for the eldest son and heir to the Earl of Morto ...

).

Douglas of Spott went to release some of his servants that were imprisoned in the gatehouse or "porter lodge" on suspicion of the murder of the old laird of Spott. The space was originally a workshop for a glazier, Thomas Peebles and James V

James V (10 April 1512 – 14 December 1542) was King of Scotland from 9 September 1513 until his death in 1542. He was crowned on 21 September 1513 at the age of seventeen months. James was the son of King James IV and Margaret Tudor, and duri ...

had converted it into a workshop for mending the royal tapestries. Now it was a prison where one man, Sleich of Cumlege in the Merse, had been tortured with the "boot

A boot is a type of footwear. Most boots mainly cover the foot and the ankle, while some also cover some part of the lower calf. Some boots extend up the leg, sometimes as far as the knee or even the hip. Most boots have a heel that is cle ...

", a device for crushing the legs, on Christmas Day. Spott's action raised the alarm more quickly than Bothwell's party wanted. The king and his courtiers barricaded themselves inside the palace helped by Harry Lindsay of Kinfauns, while Andrew Melville of Garvock

Andrew Melville of Garvock (died 1617) was a Scottish courtier and servant of Mary, Queen of Scots.

Family background

Andrew Melville was a younger son of John Melville of Raith in Fife and Helen Napier of Merchiston. His older brother James M ...

and Sir James Sandilands brought help from outside.

James VI and Anne of Denmark

Anne of Denmark (; 12 December 1574 – 2 March 1619) was the wife of King James VI and I; as such, she was Queen of Scotland

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the constitutional fo ...

retreated to the tower of the palace, while most of the court were still at supper in the great hall. Accorded to Roger Aston they "ram-forst the dores" against Bothwell's men until help came from the people of Edinburgh. Bothwell's men tried to break through with hammers and burn doors. The Chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

John Maitland of Thirlestane

Thirlestane Castle is a castle set in extensive parklands near Lauder in the Borders of Scotland. The site is aptly named Castle Hill, as it stands upon raised ground. However, the raised land is within Lauderdale, the valley of the Leader Wate ...

was besieged in his chamber. Harry Lindsay defended the queen's door. Both the King and Queen were in the tower secured with an iron yett

A yett (from the Old English and Scots language word for "gate") is a gate or grille of latticed wrought iron bars used for defensive purposes in castles and tower houses. Unlike a portcullis, which is raised and lowered vertically using mecha ...

.

A shot from the chancellor's chamber window killed Robert Scott, a brother of the Laird of Balwearie, and another raider was hit on the backside. The courtiers fought back with "staffs and other invasive weapons". Taking advantage of the darkness, Bothwell's men retreated through the stables. Seven of Bothwell's men were captured and hanged. Anne of Denmark successfully pleaded with James VI for the lives of some, especially John Naysmyth

John Naysmith (or Naismyth or Nasmyth) (1556 – 16 September 1613) was a Scottish surgeon who became surgeon to King James VI of Scotland and was appointed Royal Herbalist in London when the monarch became King James VI and I at the Union of the C ...

.

Archibald Wauchope of Niddrie was shot and injured in the hand by John Schaw, a gentleman of the equerry. John Shaw, or both of the Schaw twins were fatally injured in the struggle in the stable and they were commemorated in a poem by Alexander Montgomerie

Alexander Montgomerie (Scottish Gaelic: Alasdair Mac Gumaraid) (c. 1550?–1598) was a Scottish Jacobean courtier and poet, or makar, born in Ayrshire. He was a Scottish Gaelic speaker and a Scots speaker from Ayrshire, an area which wa ...

, the ''Epitaph of Jhone and Patrik Shaues'' which compares John and his twin brother Patrick to Castor and Pollux

Castor; grc, Κάστωρ, Kástōr, beaver. and Pollux. (or Polydeukes). are twin half-brothers in Greek and Roman mythology, known together as the Dioscuri.; grc, Διόσκουροι, Dióskouroi, sons of Zeus, links=no, from ''Dîos'' ('Z ...

.By CASTOR and by POLLUX you may boste,It was said that during the raid

Deid SHAWIS ye live, suppose your lyfis be loste.

Margaret Douglas, Countess of Bothwell

Margaret Douglas, Countess of Bothwell (died 1640) was a Scottish aristocrat and courtier.

She was a daughter of David Douglas, 7th Earl of Angus and Margaret Hamilton, daughter of John Hamilton of Samuelston, sometimes called "Clydesdale John", ...

, waited in a house nearby in the Canongate

The Canongate is a street and associated district in central Edinburgh, the capital city of Scotland. The street forms the main eastern length of the Royal Mile while the district is the main eastern section of Edinburgh's Old Town. It began ...

with jewels and money, ready to receive the captive queen. She left secretly in the night in fear after the retreat. The Privy Council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mon ...

later banished her from the King's presence, declaring that,the said Erllis wyffe, quha, as is knowne, hes bene a griter mellair in thir treassounable actionis and counsellis then become a woman; bot, howsoevir his Majestie, in respect of hir sex and present conditioun, thocht nocht convenient to deal so hardlie with hir at this tyme as she had worthelie deservit, yit meanit nocht nor nawayes allow that she sould remane ewest his persone or repair to his presensSuspicion fell on the

Or in modern spelling: the said Earl's wife, who, as is known, has been a greater dealer in these treasonable actions and counsels than becomes a woman; but, however his Majesty, in respect of her sex and present condition regnancy thought it not convenient to deal so hardly with her at this time as she had worthily deserved, yet means not in any way to allow that she should remain near his person or repair to his presence.

Duke of Lennox

The title Duke of Lennox has been created several times in the peerage of Scotland, for Clan Stewart of Darnley. The dukedom, named for the district of Lennox in Dumbarton, was first created in 1581, and had formerly been the Earldom of Lenno ...

because one his retainers, William Stewart, took part in the Raid and fled. Chancellor Maitland distrusted Lennox' offer of a refuge during the Raid. A list of fifty suspected to have been at the Raid of Holyrood includes the Earl's half-brother Hercules Stewart, Robert Hepburn in Hailes, John Ormiston in Smailholm

Smailholm ( sco, Smailhowm) is a small village in the historic county of Roxburghshire in south-east Scotland. It is at

and straddles the B6397 Gordon to Kelso road. The village is almost equidistant from both, standing northwest of the abbey ...

, and John Gibson, the grieve of Crichton, who was taken to the gallows but reprieved. James VI made a proclamation against the masked riders, conspirators who "rydis missellit" with their faces covered and disguised.

Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

El ...

wrote to Anne of Denmark

Anne of Denmark (; 12 December 1574 – 2 March 1619) was the wife of King James VI and I; as such, she was Queen of Scotland

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the constitutional fo ...

in French to congratulate her on escaping Bothwell's "wicked miserable enterprise" and that she should encourager James VI to punish the offenders and be as vigilant as her father, Frederick II of Denmark

Frederick II (1 July 1534 – 4 April 1588) was King of Denmark and Norway and Duke of Schleswig and Holstein from 1559 until his death.

A member of the House of Oldenburg, Frederick began his personal rule of Denmark-Norway at the age of ...

had been.

Raid of Falkland, June 1592

On 28 June, between one and two o'clock in the morning, Bothwell, with 300 followers, attempted to capture Falkland Palace and the king. Forewarned, the king and queen and his immediate courtiers withdrew to the tower and locked it from within. Bothwell's main assault was at the back gate near the tennis court. The defenders fired on his supporters from the tower. Melville of Halhill alleged that some who liked Bothwell loaded their guns with paper, while Bothwell refrained from using the explosivepetard

A petard is a small bomb used for blowing up gates and walls when breaching fortifications. It is of French origin and dates back to the 16th century. A typical petard was a conical or rectangular metal device containing of gunpowder, with a s ...

s he had brought to blow the gates open.

Bothwell gave up and left with the horses from the royal stables. The English border reiver

Border reivers were raiders along the Anglo-Scottish border from the late 13th century to the beginning of the 17th century. They included both Scottish and English people, and they raided the entire border country without regard to their vi ...

Richie Graham of Brackenhill and his companions including Thomas Musgrave of Bewcastle

Bewcastle is a large civil parish in the City of Carlisle district of Cumbria, England. It is in the historic county of Cumberland.

According to the 2001 census the parish had a population of 411, reducing to 391 at the 2011 Census. The pari ...

sacked Falkland town, taking horses, clothing, and money. On 29 and 30 June proclamations were issued for Bothwell's pursuit and the arrest of his accomplices, including James Scott of Balwearie

James Scott of Balwearie (died 1606) was a Scottish landowner and supporter of the rebel earls.

He was the son of Walter Scott of Balwearie and Janet Lindsay, a daughter of John Lindsay of Dowhill. His mother had been married to Andrew Lundie, a ...

, Martine of Cardone, and Lumsden of Airdrie.

According to James Melville of Halhill, he and his brother had a warning of the plot to take the King and Queen at Falkland. They advised the royal couple to ride north to Ballinbreich Castle

Ballinbreich Castle is a ruined tower house castle in Fife, Scotland.

The castle was built in the 14th century by Clan Leslie, and subsequently rebuilt several times. There may have been an outer curtain-wall though this no longer survives. Much ...

on the River Tay

The River Tay ( gd, Tatha, ; probably from the conjectured Brythonic ''Tausa'', possibly meaning 'silent one' or 'strong one' or, simply, 'flowing') is the longest river in Scotland and the seventh-longest in Great Britain. The Tay originates ...

for greater safety. This counsel was overruled and the Melville brothers were told to ride south to summon reinforcements to Falkland. They discovered that Bothwell was close by and sent a servant, Robert Athlek, back to Falkland. His story was not believed. On his way back from Falkland he encountered Bothwell's forces on the Lomond Hills

The Lomond Hills (meaning either beacon hills or bare hills), also known outside the locality as the Paps of Fife, are a range of hills in central Scotland. They lie in western central Fife and Perth and Kinross, Scotland. At West Lomond is the ...

in the dark. He was believed when he came back a second time, and so the royals moved into the gatehouse tower for extra security.

Second raid of Holyrood, July 1593

On Tuesday 24 July 1593, the Earl of Bothwell in disguise, helped byMarie Ruthven, Countess of Atholl

Marie Ruthven, Countess of Atholl was a Scottish aristocrat.

She was a daughter of William Ruthven, 1st Earl of Gowrie and Dorothea Stewart, the oldest daughter of Henry Stewart, 1st Lord Methven and Janet Stewart, a daughter of John Stewart, 2n ...

, smuggled himself into Holyroodhouse and forced himself into the King's presence, in his bedchamber. The Countess of Atholl had access to a back gate which led to her mother, Dorothea Stewart, Countess of Gowrie

Dorothea Stewart, Countess of Gowrie was a Scottish aristocrat. The dates of the birth and death of Dorothea Stewart are unknown.

Early life

She was the oldest daughter of Henry Stewart, 1st Lord Methven and Janet Stewart, daughter of John S ...

's house.

It was said that Bothwell hid behind the tapestry or hangings until the best moment. Accounts say the King was in his "retiring place" or "secret place". According to John Spottiswoode

John Spottiswoode (Spottiswood, Spotiswood, Spotiswoode or Spotswood) (1565 – 26 November 1639) was an Archbishop of St Andrews, Primate of All Scotland, Lord Chancellor, and historian of Scotland.

Life

He was born in 1565 at Greenbank in ...

, James VI saw Bothwell's drawn sword, and said, "Strike Traitor! and make an end of thy work, for I desire not to live any longer". Bothwell kneeled and offered his sword to the king so he could behead him if he wished. James declined. Soon numerous Bothwell supporters also entered the room. William Keith of Delny

Sir William Keith of Delny (died 1599) was a Scottish courtier and Master of the Royal Wardrobe. He also served as ambassador for James VI to various countries. He was an important intermediary between George Keith, 5th Earl Marischal and the kin ...

and the Earl of Mar

There are currently two earldoms of Mar in the Peerage of Scotland, and the title has been created seven times. The first creation of the earldom is currently held by Margaret of Mar, 31st Countess of Mar, who is also clan chief of Clan Mar. T ...

offered some resistance.

Bothwell told his version of this dialogue to William Reed in Berwick-upon-Tweed

Berwick-upon-Tweed (), sometimes known as Berwick-on-Tweed or simply Berwick, is a town and civil parish in Northumberland, England, south of the Anglo-Scottish border, and the northernmost town in England. The 2011 United Kingdom census recor ...

. When James saw Bothwell, he said "Francis, thou will do me no ill!". Bothwell kneeled and offered his sword. The Duke and the Earl of Atholl came in the room and spoke on Bothwell's behalf, "May it please your grace, this is a noble man of your own blood, who would be loth to see you take any ill, and be ready always to venture his life with you. Your Grace is to take things in hand now which cannot be well done without the assistance of this man who you may be assured of". According to Bothwell, the king forgave him, saying, "Francis, you ask us pardon, for what would you have pardon?" as if his entrance to the palace had been no offence.

The Provost of Edinburgh, Alexander Home, came to the palace to help, but the king said things were fine and Bothwell told him to get packing. Various noblemen were present and Lord Ochiltree

Lord Ochiltree (or Ochiltrie) of Lord Stuart of Ochiltree was a title in the Peerage of Scotland. In 1542 Andrew Stewart, 2nd Lord Avondale (see the Earl Castle Stewart for earlier history of the family) exchanged the lordship of Avondale with Si ...

offered to fight Bothwell over the issue of the killing of his brother Sir William Stewart in 1588. There was no fighting. The king accepted Bothwell's protestations of loyalty and an agreement for his pardon from charges of treason was reached. Bothwell was never returned to favour and went into exile.

Two Danish ambassadors, Niels Krag

Niels Krag (1550-1602), was a Danish academic and diplomat.

Krag was a Doctor of Divinity, Professor at the University of Copenhagen, and historiographer Royal.

Mission to Scotland

In August 1589 the Danish council decided that Peder Munk, Breide ...

and Steen Bille

Steen Bille (1565–1629) was a Danish councillor and diplomat.

He was the son of Jens Bille and Karen Rønnow, and is sometimes called "Steen Jensen Bille". His father compiled a manuscript of ballads, Jens Billes visebog.

As a young man Bille ...

, who had come to inspect the queen's jointure settlement and land rentals, were in Edinburgh during the raid. They were lodged in the Canongate

The Canongate is a street and associated district in central Edinburgh, the capital city of Scotland. The street forms the main eastern length of the Royal Mile while the district is the main eastern section of Edinburgh's Old Town. It began ...

at John Kinloch's house close to the palace. They recorded events in a Latin journal of their embassy. James VI had to explain the circumstances of Bothwell's appearance at Holyrood to them in a meeting with the Privy Council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mon ...

in the Tolbooth

A tolbooth or town house was the main municipal building of a Scottish burgh, from medieval times until the 19th century. The tolbooth usually provided a council meeting chamber, a court house and a jail. The tolbooth was one of three essen ...

. The Danish ambassadors had another audience with James VI in the palace garden on 25 July.

The English ambassador Robert Bowes thought that Marie Ruthven, Countess of Atholl was a dependable ally of Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

El ...

and opposed to the faction of the Earl of Huntly

Marquess of Huntly (traditionally spelled Marquis in Scotland; Scottish Gaelic: ''Coileach Strath Bhalgaidh'') is a title in the Peerage of Scotland that was created on 17 April 1599 for George Gordon, 6th Earl of Huntly. It is the oldest existin ...

, and in October 1593 he advised that Elizabeth should send her a jewel as a token of support. The king's favourite, Sir George Home, was now lodged in the house by Holyrood, for extra security. Some unjustly accused Anne of Denmark of trying helping Bothwell reach the king.Maureen Meikle

Maureen M. Meikle is an academic historian.

Her 1988 Phd thesis at the University of Edinburgh was titledLairds and gentlemen: A study of the landed families of the Eastern Anglo-Scottish Borders c.1540-1603.

She is writing a new biography of Ann ...

, 'A meddlesome princess: Anna of Denmark and Scottish court politics, 1589-1603', Julian Goodare

Julian Goodare is a professor of history at University of Edinburgh.

Academic career

Goodare studied at the University of Edinburgh in the 1980s, afterwards engaged as a postdoctoral fellow. He lectured at the University of Wales, and at the Univ ...

& Michael Lynch, ''The Reign of James VI'' (East Linton: Tuckwell, 2000), pp. 133-4.

References

{{Reflist History of Edinburgh Court of James VI and I Conflicts in 1591 Judicial torture in Scotland 1590s conflicts 1591 in Scotland 1592 in Scotland 1593 in Scotland