Rowse, A. L. on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Alfred Leslie Rowse (4 December 1903 – 3 October 1997) was a British historian and writer, best known for his work on

Alfred Leslie Rowse (4 December 1903 – 3 October 1997) was a British historian and writer, best known for his work on

As well as his own appearances on radio and television, Rowse has been depicted in various TV drama documentaries about British politics in the 1930s and

As well as his own appearances on radio and television, Rowse has been depicted in various TV drama documentaries about British politics in the 1930s and

The Elizabethans and America: The Trevelyan Lectures at Cambridge, 1958

', London, Macmillan, 1959 * ''

1984 3rd edition

* ''A Cornishman at

abstract with table of contents, Taylor & Francis website

* ''Court and Country: Studies in Tudor Social History'', Brighton: Harvester Press, 1987 * '' Froude the Historian: Victorian Man of Letters'', Gloucester: Alan Sutton, 1987 * '' Quiller-Couch: a Portrait of "Q"'', London: Methuen, 1988 * ''A. L. Rowse's Cornwall: a Journey through Cornwall's Past and Present'', London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1988 * ''Friends and Contemporaries'', London: Methuen, 1989 * ''The Controversial Colensos'', Redruth: Dyllansow Truran, 1989 * ''Discovering

A. L. Rowse: A Bibliophile's Extensive Bibliography

', Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press * Cauveren, Sydney (2001), "A. L. Rowse: Historian and Friend", ''

article in the ''International Literary Quarterly''

* Slattery-Christy, David (2017)

Other People's Fu**ing! An Oxford Affair

New play exploring the relationship between A.L. Rowse and Adam von Trott during the 1930s in Oxford. Published by Christyplays. www.christyplays.com

Papers of A L Rowse: research, literary and personal manuscripts at the University of Exeter

{{DEFAULTSORT:Rowse, A. L. 1903 births 1997 deaths 20th-century English biographers 20th-century English historians 20th-century English poets 20th-century English male writers Academics of the London School of Economics Alumni of Christ Church, Oxford Bards of Gorsedh Kernow Burials in Cornwall English LGBTQ poets English LGBTQ politicians English book and manuscript collectors English gay writers Fellows of All Souls College, Oxford Fellows of the British Academy Fellows of the Royal Historical Society Fellows of the Royal Society of Literature Historians of Cornwall Labour Party (UK) parliamentary candidates Members of the Order of the Companions of Honour People educated at St Austell Grammar School People from St Austell Poets from Cornwall Shakespearean scholars People associated with Merton College, Oxford People associated with the Huntington Library Historians of the University of Oxford English literary historians Historians of English literature

Alfred Leslie Rowse (4 December 1903 – 3 October 1997) was a British historian and writer, best known for his work on

Alfred Leslie Rowse (4 December 1903 – 3 October 1997) was a British historian and writer, best known for his work on Elizabethan

The Elizabethan era is the epoch in the Tudor period of the history of England during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I (1558–1603). Historians often depict it as the golden age in English history. The Roman symbol of Britannia (a female per ...

England and books relating to Cornwall

Cornwall (; or ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is also one of the Celtic nations and the homeland of the Cornish people. The county is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, ...

.

Born in Cornwall and raised in modest circumstances, he was encouraged to study for Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

by fellow-Cornishman Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch

Sir Arthur Thomas Quiller-Couch (; 21 November 186312 May 1944) was a Cornish people, British writer who published using the pen name, pseudonym Q. Although a prolific novelist, he is remembered mainly for the monumental publication ''The Oxfor ...

. He was elected a fellow

A fellow is a title and form of address for distinguished, learned, or skilled individuals in academia, medicine, research, and industry. The exact meaning of the term differs in each field. In learned society, learned or professional society, p ...

of All Souls College

All Souls College (official name: The College of All Souls of the Faithful Departed, of Oxford) is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. Unique to All Souls, all of its members automatically become fellows (i.e., full me ...

and later appointed lecturer at Merton College

Merton College (in full: The House or College of Scholars of Merton in the University of Oxford) is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. Its foundation can be traced back to the 1260s when Walter de Merton, chancellor ...

. Best known of his many works was ''The Elizabethan Age'' trilogy. His work on Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

included a claim to have identified the '' Dark Lady of the Sonnets'' as Emilia Lanier

Emilia Lanier (; 1569–1645) was the first woman in England to assert herself as a professional poet, through her volume '' Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum'' (''Hail, God, King of the Jews'', 1611). Attempts have been made to equate her with Shakesp ...

, which attracted much interest from scholars, but also many counterclaims. Rowse was in popular demand as a lecturer in North America.

In the 1930s, he stood unsuccessfully as the Labour candidate

A candidate, or nominee, is a prospective recipient of an award or honor, or a person seeking or being considered for some kind of position. For example, one can be a candidate for membership in a group (sociology), group or election to an offic ...

for Penryn and Falmouth, though later in life he became a Conservative.

Life and politics

Rowse was born at Tregonissey, nearSt Austell

Saint Austell (, ; ) is a town in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom, south of Bodmin and west of the border with Devon.

At the 2021 Census in the United Kingdom, census it had a population of 20,900.

History

St Austell was a village centred ...

, Cornwall, the son of Annie (née Vanson) and Richard Rowse, a china clay

Kaolinite ( ; also called kaolin) is a clay mineral, with the chemical composition aluminium, Al2Silicon, Si2Oxygen, O5(hydroxide, OH)4. It is a layered silicate mineral, with one tetrahedron, tetrahedral sheet of silica () linked through oxygen ...

worker. Despite his modest origins and his parents' limited education, he won a place at St Austell

Saint Austell (, ; ) is a town in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom, south of Bodmin and west of the border with Devon.

At the 2021 Census in the United Kingdom, census it had a population of 20,900.

History

St Austell was a village centred ...

County Grammar School

A grammar school is one of several different types of school in the history of education in the United Kingdom and other English-speaking countries, originally a Latin school, school teaching Latin, but more recently an academically oriented Se ...

and then a scholarship to Christ Church, Oxford

Christ Church (, the temple or house, ''wikt:aedes, ædes'', of Christ, and thus sometimes known as "The House") is a Colleges of the University of Oxford, constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. Founded in 1546 by Henry V ...

, in 1921. He was encouraged in his pursuit of an academic career by a fellow Cornish man of letters, Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch

Sir Arthur Thomas Quiller-Couch (; 21 November 186312 May 1944) was a Cornish people, British writer who published using the pen name, pseudonym Q. Although a prolific novelist, he is remembered mainly for the monumental publication ''The Oxfor ...

, of Polperro, who recognised his ability from an early age. Rowse endured doubting comments about his paternity, thus he paid particular attention to his mother's association with a local farmer and butcher from Polgooth, near St Austell, Frederick William May (1872–1953). Any such frustrations were channelled into academia, which reaped him dividends later in life.

Rowse had planned to study English literature

English literature is literature written in the English language from the English-speaking world. The English language has developed over more than 1,400 years. The earliest forms of English, a set of Anglo-Frisian languages, Anglo-Frisian d ...

, having developed an early love of poetry, but was persuaded to read history. He was a popular undergraduate and made many friendships that lasted for life. He graduated with first class honours in 1925 and was elected a fellow

A fellow is a title and form of address for distinguished, learned, or skilled individuals in academia, medicine, research, and industry. The exact meaning of the term differs in each field. In learned society, learned or professional society, p ...

of All Souls College

All Souls College (official name: The College of All Souls of the Faithful Departed, of Oxford) is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. Unique to All Souls, all of its members automatically become fellows (i.e., full me ...

the same year. In 1927 Rowse was appointed lecturer at Merton College

Merton College (in full: The House or College of Scholars of Merton in the University of Oxford) is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. Its foundation can be traced back to the 1260s when Walter de Merton, chancellor ...

, where he stayed until 1930. He then became a lecturer at the London School of Economics

The London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), established in 1895, is a public research university in London, England, and a member institution of the University of London. The school specialises in the social sciences. Founded ...

. In 1929, he proceeded to a Master of Arts

A Master of Arts ( or ''Artium Magister''; abbreviated MA or AM) is the holder of a master's degree awarded by universities in many countries. The degree is usually contrasted with that of Master of Science. Those admitted to the degree have ...

degree. While at Oxford, Rowse met Adam von Trott zu Solz who was attending Oxford as a Rhodes scholar. Rowse became deeply infatuated with Trott, a man whom he madly loved and who influenced his thinking about Germany. Trott took Rowse on a number of tours of Berlin, Hamburg and Dresden to introduce him to German high culture. Rowse's biographer, Richard Ollard, described Trott as "...the most longest and most intense love" of Rowse's life, a man whom he was never able to get over despite a rift that had developed between them by the late 1930s. Rowse described Trott as "six feet tall" and "well aware of his shattering beauty", but complained that he was "fundamentally heterosexual". He later stated that his relationship with Trott was "an ideal love-affair, platonic in a philosophical sense; we never exchanged a kiss, let alone an embrace. We were both extremely high-minded, perhaps too much so".

In 1931, Rowse contested the parliamentary seat of Penryn and Falmouth for the Labour Party, but was unsuccessful, finishing third behind a Liberal. In the general election of 1935 he again stood unsuccessfully, but managed to finish in second place, ahead of the Liberal. In both the 1931 and 1935 elections, Maurice Petherick was returned as a Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

MP to Parliament, albeit with a minority of the vote. Rowse supported calls made by Sir Stafford Cripps

Sir Richard Stafford Cripps (24 April 1889 – 21 April 1952) was a British Labour Party (UK), Labour Party politician, barrister, and diplomat.

A wealthy lawyer by background, Cripps first entered Parliament at a 1931 Bristol East by-election ...

and others for a "Popular Front". Cripps was expelled from the Labour Party for his views. In 1937, Rowse wrote in his diary: "My emotional life was engulfed in Adam, quite anguished enough in itself". By this point, Rowse and Trott were drifting apart as Trott sought to make a diplomatic career in the highly elitist ''Auswärtiges Amt'' (Foreign Office), which offended Rowse as serving in the ''Auswärtiges Amt'' meant serving the Nazis. Moreover, Trott was a German ultra-nationalist committed to recovering all of the lands lost under the Treaty of Versailles, which led him to a certain support for Nazi foreign policy, a position that Rowse could not accept. Trott's viewpoint that he did not particularly like the Nazis, but was willing to serve them insofar as Nazi foreign policy was aimed at undoing the Treaty of Versailles was dismissed by Rowse as amoral.

Rowse worked to get agreement by Labour and Liberal parties in Devon and Cornwall, making a common cause with the Liberal MP Sir Richard Acland. A general election was expected to take place in 1939, and Rowse, who was again Labour's candidate for Penryn & Falmouth, was not expected to have a Liberal opponent. That would increase his chances of winning. But, due to outbreak of war, the election did not take place and his political career was effectively ended.

Undeterred, Rowse chose to continue his career by seeking administrative positions at Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

becoming Sub-Warden of All Souls College

All Souls College (official name: The College of All Souls of the Faithful Departed, of Oxford) is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. Unique to All Souls, all of its members automatically become fellows (i.e., full me ...

. In 1952, he failed in his candidacy for election as Warden against John Sparrow. Shortly afterwards he began what became regular trips to The Huntington Library in Southern California, where for many years he was a senior research fellow. He received a doctorate ( DLitt) from Oxford University in 1953. After delivering the British Academy

The British Academy for the Promotion of Historical, Philosophical and Philological Studies is the United Kingdom's national academy for the humanities and the social sciences.

It was established in 1902 and received its royal charter in the sa ...

's 1957 Raleigh Lecture on history about Sir Richard Grenville's place in English history, Rowse was selected as a fellow of the academy ( FBA) in 1958.

Rowse published about 100 books. By the mid-20th century, he was a celebrated author and much-travelled lecturer, especially in the United States. He also published many popular articles in newspapers and magazines in Great Britain and the United States. His brilliance was widely recognised. His knack for the sensational, as well as his academic boldness (which some considered to be irresponsible carelessness), sustained his reputation. His opinions on rival popular historians, such as Hugh Trevor-Roper

Hugh Redwald Trevor-Roper, Baron Dacre of Glanton, (15 January 1914 – 26 January 2003) was an English historian. He was Regius Professor of Modern History (Oxford), Regius Professor of Modern History at the University of Oxford.

Trevor-Rope ...

and A. J. P. Taylor, were expressed sometimes in very ripe terms. In 1977, he sparked much controversy with his book ''Homosexuals in History'' which linked creativity in the arts with being gay. Rowse wrote that his book was a study on the "predisposing conditions of creativeness, the psychological rewards of ambivalence, the doubled response to life, the sharping of perception, the tensions that led to achievement". ''Homosexuals in History'' attracted critical reviews as some of the artists identified as being gay in the book were based on only circumstantial evidence; the book had no footnotes or endnotes; his theory of a connection between artistic creativity and homosexuality was ill-defined; and his opinionated writing style full of arch comments alienated many. The American scholar Richard Aldrich wrote that for its flaws ''Homosexuals in History'' was one of the first serious studies in gay history and that many of the artists whom Rowse "outed" in his book were indeed gay, which marked the first time that this aspects of their lives was discussed in a mainstream book.

In his later years, Rowse moved increasingly towards the political right, and many considered him to be part of the Tory

A Tory () is an individual who supports a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalist conservatism which upholds the established social order as it has evolved through the history of Great Britain. The To ...

tradition by the time he died. One of Rowse's lifelong themes in his books and articles was his condemnation of the Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

-dominated National Government's policy of appeasement

Appeasement, in an International relations, international context, is a diplomacy, diplomatic negotiation policy of making political, material, or territorial concessions to an aggressive power (international relations), power with intention t ...

of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

in the 1930s, and the economic and political consequences for Great Britain of fighting a Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

with Germany. He also criticised his former Labour Party colleagues–including George Lansbury

George Lansbury (22 February 1859 – 7 May 1940) was a British politician and social reformer who led the Labour Party (UK), Labour Party from 1932 to 1935. Apart from a brief period of ministerial office during the Labour government of 1 ...

, Kingsley Martin

Basil Kingsley Martin (28 July 1897 – 16 February 1969) usually known as Kingsley Martin, was a British journalist who edited the left-leaning political magazine the ''New Statesman'' from 1930 to 1960.

Early life

He was the son of (Dav ...

and Richard Crossman—for endorsing appeasement, writing "not one of the Left

Left may refer to:

Music

* ''Left'' (Hope of the States album), 2006

* ''Left'' (Monkey House album), 2016

* ''Left'' (Helmet album), 2023

* "Left", a song by Nickelback from the album ''Curb'', 1996

Direction

* Left (direction), the relativ ...

intellectuals could republish what they wrote in the Thirties without revealing what idiotic judgments they made about events." Another was his horror at the degradation of standards in modern society. He is reported as saying: "... this filthy twentieth century. I hate its guts".

Despite international academic success, Rowse remained proud of his Cornish roots. He retired from Oxford in 1973 to Trenarren House, his Cornish home, from where he remained active as writer, reviewer and conversationalist until immobilised by a stroke in 1996. He died at home on 3 October 1997. His ashes are buried in the Campdowns Cemetery, Charlestown near St Austell

Saint Austell (, ; ) is a town in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom, south of Bodmin and west of the border with Devon.

At the 2021 Census in the United Kingdom, census it had a population of 20,900.

History

St Austell was a village centred ...

.

Elizabethan and Shakespearean scholarship

Rowse's early works focus on 16th-century England and his first full-length historical monograph, ''Sir Richard Grenville of the Revenge'' (1937), was a biography of a 16th-century sailor. His next was ''Tudor Cornwall'' (1941), a lively detailed account of Cornish society in the 16th century. He consolidated his reputation with a one-volume general history of England, ''The Spirit of English History'' (1943), but his most important work was the historical trilogy ''The Elizabethan Age'': ''The England of Elizabeth'' (1950), ''The Expansion of Elizabethan England'' (1955), and ''The Elizabethan Renaissance'' (1971–72), respectively examine the society, overseas exploration, and culture of late 16th-century England. In 1963 Rowse began to concentrate onWilliam Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

, starting with a biography in which he claimed to have dated all the sonnets

A sonnet is a fixed poetic form with a structure traditionally consisting of fourteen lines adhering to a set Rhyme scheme, rhyming scheme. The term derives from the Italian word ''sonetto'' (, from the Latin word ''sonus'', ). Originating in ...

, identified Christopher Marlowe

Christopher Marlowe ( ; Baptism, baptised 26 February 156430 May 1593), also known as Kit Marlowe, was an English playwright, poet, and translator of the Elizabethan era. Marlowe is among the most famous of the English Renaissance theatre, Eli ...

as the suitor's rival and solved all but one of the other problems posed by the sonnets. His failure to acknowledge his reliance upon the work of other scholars alienated some of his peers, but he won popular acclaim. In 1973 he published ''Shakespeare the Man'', in which he claimed to have solved the final problem – the identity of the ' Dark Lady': from a close reading of the sonnets and the diaries of Simon Forman, he asserted that she must have been Emilia Lanier

Emilia Lanier (; 1569–1645) was the first woman in England to assert herself as a professional poet, through her volume '' Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum'' (''Hail, God, King of the Jews'', 1611). Attempts have been made to equate her with Shakesp ...

, whose poems he would later collect. He suggested that Shakespeare had been influenced by the feud between the Danvers and Long families in Wiltshire, when he wrote ''Romeo and Juliet

''The Tragedy of Romeo and Juliet'', often shortened to ''Romeo and Juliet'', is a Shakespearean tragedy, tragedy written by William Shakespeare about the romance between two young Italians from feuding families. It was among Shakespeare's ...

''. The Danverses were friends of Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton

Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton, (pronunciation uncertain: "Rezley", "Rizely" (archaic), (present-day) and have been suggested; 6 October 1573 – 10 November 1624) was the only son of Henry Wriothesley, 2nd Earl of Sou ...

.

Rowse's "discoveries" about Shakespeare's sonnets amount to the following:

# The Fair Youth was the 19-year-old Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton

Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton, (pronunciation uncertain: "Rezley", "Rizely" (archaic), (present-day) and have been suggested; 6 October 1573 – 10 November 1624) was the only son of Henry Wriothesley, 2nd Earl of Sou ...

, extremely handsome and bisexual.

# The sonnets were written 1592–1594/5.

# The "rival poet" was Christopher Marlowe

Christopher Marlowe ( ; Baptism, baptised 26 February 156430 May 1593), also known as Kit Marlowe, was an English playwright, poet, and translator of the Elizabethan era. Marlowe is among the most famous of the English Renaissance theatre, Eli ...

.

# The "Dark Lady" was Emilia Lanier

Emilia Lanier (; 1569–1645) was the first woman in England to assert herself as a professional poet, through her volume '' Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum'' (''Hail, God, King of the Jews'', 1611). Attempts have been made to equate her with Shakesp ...

. His use of the diaries of Simon Forman, which contained material about her, influenced other scholars.

# Christopher Marlowe's death is recorded in the sonnets.

# Shakespeare was a heterosexual

Heterosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or sexual behavior between people of the opposite sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, heterosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions ...

man, who was faced with an unusual situation when the handsome, young, bisexual

Bisexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or sexual behavior toward both males and females. It may also be defined as the attraction to more than one gender, to people of both the same and different gender, or the attraction t ...

Earl of Southampton fell in love with him.

Rowse was dismissive of those who rejected his views. He supported his conclusions. In the case of Shakespeare's sexuality, he emphasised the playwright's heterosexual inclinations by noting that he had impregnated an older woman by the time he was 18, and was consequently obliged to marry her. Moreover, he fathered three children by the time he was 21. In the sonnets, Shakespeare's explicit erotic interest lies with the Dark Lady; he obsesses about her. Shakespeare was still married and Rowse believes he was having an extramarital affair.

Personal attitudes

The diary excerpts published in 2003 reveal that "he was an overt even rather proud homosexual in a pre- Wolfenden age, fascinated by young policemen and sailors, obsessively speculating on the sexual proclivities of everyone he meets". Much later, following retirement, he said, "of course, I used to be a homo; but now, when it doesn't matter, if anything I'm a hetero". He was aware of his own intelligence from earliest childhood, and obsessed that others either did not accept this fact, or not quickly enough. The diaries describe what he said were "a series of often inane jealousies". He described a "Slacker State": "I don't want to have my money scalped off me to maintain other people's children. I don't like other people; I particularly don't like their children; I deeply disapprove of their proliferation making the globe uninhabitable. The fucking idiots – I don't want to pay for their fucking."Literary career

Rowse's first book was ''On History, a Study of Present Tendencies'' published in 1927 as the seventh volume of Kegan Paul's ''Psyche Miniature General Series''. In 1931 he contributed to T. S. Eliot's quarterly review '' The Criterion''. In 1935 he co-edited Charles Henderson's ''Essays in Cornish History'' for theClarendon Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the publishing house of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world. Its first book was printed in Oxford in 1478, with the Press officially granted the legal right to print books ...

. His best-seller was his first volume of autobiography, ''A Cornish Childhood'', first published by Jonathan Cape in 1942, which has gone on to sell nearly half a million copies worldwide. It describes his hard struggle to get to the University of Oxford and his love/hate relationship with Cornwall.

From the 1940s to the 1970s, he served as the General Editor for the popular "Teach Yourself History" and "Men and their Times" series, published by the English Universities Press.

Rowse wrote poetry all his life. He contributed poems to ''Public School Verse'' whilst at St Austell Grammar School. He also had verse published in ''Oxford 1923'', ''Oxford 1924'', and ''Oxford 1925''. His collected poems ''A Life'' were published in 1981. The poetry is mainly autobiographical, descriptive of place (especially Cornwall) and people he knew and cared for, e.g. ''The Progress of Love'', which describes his platonic love for Adam von Trott, a handsome and aristocratic German youth who studied at Oxford in the 1930s and who was later executed for his part in the July Plot of 1944 to kill Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

. Unusually for a British poet, Rowse wrote a great number of poems inspired by American scenery.

His most controversial book (at the time of publication) was on the subject of human sexuality

Human sexuality is the way people experience and express themselves sexually. This involves biological, psychological, physical, erotic, emotional, social, or spiritual feelings and behaviors. Because it is a broad term, which has varied ...

: ''Homosexuals in History'' (1977).

Biographer

He wrote other biographies of English historical and literary figures, and many other historical works. His biographies include studies of Shakespeare, Marlowe, and the Earl of Southampton, the major players in the sonnets, as well as later luminaries of English literature such asJohn Milton

John Milton (9 December 1608 – 8 November 1674) was an English poet, polemicist, and civil servant. His 1667 epic poem ''Paradise Lost'' was written in blank verse and included 12 books, written in a time of immense religious flux and politic ...

, Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift (30 November 1667 – 19 October 1745) was an Anglo-Irish writer, essayist, satirist, and Anglican cleric. In 1713, he became the Dean (Christianity), dean of St Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin, and was given the sobriquet "Dean Swi ...

and Matthew Arnold

Matthew Arnold (24 December 1822 – 15 April 1888) was an English poet and cultural critic. He was the son of Thomas Arnold, the headmaster of Rugby School, and brother to both Tom Arnold (academic), Tom Arnold, literary professor, and Willi ...

. A devoted cat-lover, he also wrote the biographies of several cats who came to live with him at Trenarren, claiming that it was as much a challenge to write the biography of a favourite cat as it was a Queen of England. He also published a number of short stories, mainly about Cornwall, of interest more for their thinly veiled autobiographical resonances than their literary merit. His last book, ''My View of Shakespeare'', published in 1996, summed up his life-time's appreciation of ''The Bard of Stratford''. The book was dedicated ''"To HRH The Prince of Wales in common devotion to William Shakespeare".''

Bibliophile

One of Rowse's great enthusiasms was collecting books, and he owned many first editions, many of them bearing his acerbic annotations. For example, his copy of the January 1924 edition of ''The Adelphi

''The Adelphi'' or ''New Adelphi'' was an English literary journal founded by John Middleton Murry and published between 1923 and 1955. The first issue appeared in June 1923, with issues published monthly thereafter. Between August 1927 and Se ...

'' magazine edited by John Middleton Murry

John Middleton Murry (6 August 1889 – 12 March 1957) was an English writer. He was a prolific author, producing more than 60 books and thousands of essays and reviews on literature, social issues, politics, and religion during his lifetime. ...

bears a pencilled note after Murry's poem ''In Memory of Katherine Mansfield

Kathleen Mansfield Murry (née Beauchamp; 14 October 1888 – 9 January 1923) was a New Zealand writer and critic who was an important figure in the Literary modernism, modernist movement. Her works are celebrated across the world and have been ...

'': 'Sentimental gush on the part of JMM. And a bad poem. A.L.R.'

Upon his death in 1997 he bequeathed his book collection to the University of Exeter

The University of Exeter is a research university in the West Country of England, with its main campus in Exeter, Devon. Its predecessor institutions, St Luke's College, Exeter School of Science, Exeter School of Art, and the Camborne School of ...

, and his personal archive of manuscripts, diaries, and correspondence. In 1998 the University Librarian selected about sixty books from Rowse's own working library and a complete set of his published books. The Royal Institution of Cornwall selected some of the remaining books and the rest were sold to dealers. The London booksellers Heywood Hill produced two catalogues of books from his library.

Honours

Rowse was elected aFellow of the British Academy

Fellowship of the British Academy (post-nominal letters FBA) is an award granted by the British Academy to leading academics for their distinction in the humanities and social sciences. The categories are:

# Fellows – scholars resident in t ...

(FBA), of the Royal Historical Society

The Royal Historical Society (RHS), founded in 1868, is a learned society of the United Kingdom which advances scholarly studies of history.

Origins

The society was founded and received its royal charter in 1868. Until 1872 it was known as the H ...

(FRHistS

The Royal Historical Society (RHS), founded in 1868, is a learned society of the United Kingdom which advances scholarly studies of history.

Origins

The society was founded and received its royal charter in 1868. Until 1872 it was known as the H ...

) and of the Royal Society of Literature

The Royal Society of Literature (RSL) is a learned society founded in 1820 by King George IV to "reward literary merit and excite literary talent". A charity that represents the voice of literature in the UK, the RSL has about 800 Fellows, elect ...

(FRSL

The Royal Society of Literature (RSL) is a learned society founded in 1820 by George IV of the United Kingdom, King George IV to "reward literary merit and excite literary talent". A charity that represents the voice of literature in the UK, the ...

).

In addition to his DLitt (Oxon) degree (1953), Rowse received the honorary degrees of DLitt from the University of Exeter

The University of Exeter is a research university in the West Country of England, with its main campus in Exeter, Devon. Its predecessor institutions, St Luke's College, Exeter School of Science, Exeter School of Art, and the Camborne School of ...

in 1960 and DCL from the University of New Brunswick

The University of New Brunswick (UNB) is a public university with two primary campuses in Fredericton and Saint John, New Brunswick. It is the oldest English language, English-language university in Canada, and among the oldest public universiti ...

, Fredericton, Canada, the same year.

In 1968 he was made a Bard

In Celtic cultures, a bard is an oral repository and professional story teller, verse-maker, music composer, oral historian and genealogist, employed by a patron (such as a monarch or chieftain) to commemorate one or more of the patron's a ...

of Gorseth Kernow, taking the bardic name

A bardic name (, ) is a pseudonym used in Wales, Cornwall, or Brittany by poets and other artists, especially those involved in the eisteddfod movement.

The Welsh language, Welsh term bardd ('poet') originally referred to the Welsh poets of the M ...

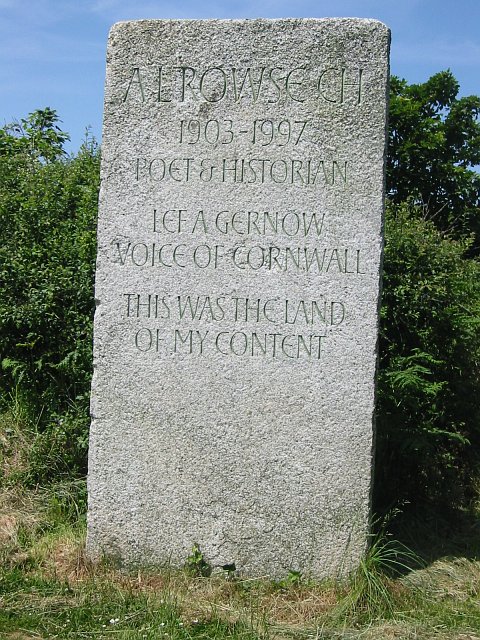

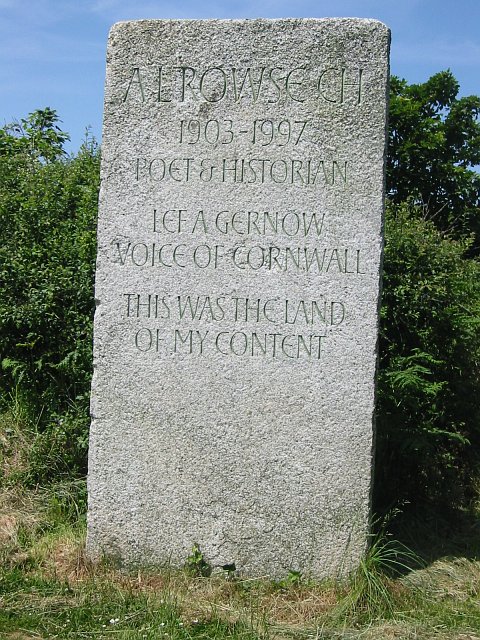

''Lef A Gernow'' ('Voice of Cornwall'), reflecting his high standing in the Cornish community.

He was elected to the Athenaeum Club under Rule II in 1972, and received the Benson Medal of the Royal Society of Literature

The Royal Society of Literature (RSL) is a learned society founded in 1820 by King George IV to "reward literary merit and excite literary talent". A charity that represents the voice of literature in the UK, the RSL has about 800 Fellows, elect ...

in 1982.

Rowse was appointed a Member of the Order of the Companions of Honour ( CH) in the 1997 New Year Honours.

Posthumous reputation

As well as his own appearances on radio and television, Rowse has been depicted in various TV drama documentaries about British politics in the 1930s and

As well as his own appearances on radio and television, Rowse has been depicted in various TV drama documentaries about British politics in the 1930s and appeasement

Appeasement, in an International relations, international context, is a diplomacy, diplomatic negotiation policy of making political, material, or territorial concessions to an aggressive power (international relations), power with intention t ...

.

Christopher William Hill's radio play ''Accolades'', rebroadcast on BBC Radio 4

BBC Radio 4 is a British national radio station owned and operated by the BBC. The station replaced the BBC Home Service on 30 September 1967 and broadcasts a wide variety of spoken-word programmes from the BBC's headquarters at Broadcasti ...

in March 2007 as a tribute to its star, Ian Richardson, who had died the previous month, covers the period leading up to the publication of ''Shakespeare the Man'' in 1973 and publicity surrounding Rowse's unshakable confidence that he had discovered the identity of the Dark Lady of the Sonnets. It was broadcast again on 9 July 2008.

''A Cornish Childhood'' has also been adapted for voices (in the style of ''Under Milk Wood

''Under Milk Wood'' is a 1954 radio drama by Welsh people, Welsh poet Dylan Thomas. The BBC commissioned the play, which was later adapted for the stage. The first public reading was in New York City in 1953.

A Under Milk Wood (1972 film), f ...

'') by Judith Cook.

Selected works

* ''On History: a Study of Present Tendencies'', London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., 1927 * ''Science and History: a New View of History'', London: W. W. Norton, 1928 * ''Politics and the Younger Generation'', London: Faber & Faber, 1931 * ''The Question of theHouse of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the lower house, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. One of the oldest ext ...

'', London: Hogarth Press, 1934

* '' Queen Elizabeth and Her Subjects'' (with G. B. Harrison), London: Allen & Unwin, 1935

* ''Mr. Keynes and the Labour Movement'', London: Macmillan, 1936

* '' Sir Richard Grenville of the "Revenge"'', London: Jonathan Cape, 1937

* ''What is Wrong with the Germans?'', 1940

* ''Tudor Cornwall'', London: Jonathan Cape, 1941

* ''A Cornish Childhood'', London: Jonathan Cape, 1942

* ''The Spirit of English History'', London: Jonathan Cape, 1943

* ''The English Spirit: Essays in History and Literature'', London: Macmillan, 1944

* ''West-Country Stories'', London: Macmillan, 1945

* ''The Use of History'' (key volume in the ''"Teach Yourself History"'' series), London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1946

* ''The End of an Epoch: Reflections on Contemporary History'', London: Macmillan, 1947

* ''The England of Elizabeth: the Structure of Society''. London: Macmillan, 1950

* ''The English Past: Evocation of Persons and Places'', London: Macmillan, 1951

* ''An Elizabethan Garland'', London: Macmillan, 1953

* ''The Expansion of Elizabethan England'', London: Macmillan, 1955

* ''The Early Churchills'', London: Macmillan, 1956

* ''The Later Churchills'', London: Macmillan, 1958

* The Elizabethans and America: The Trevelyan Lectures at Cambridge, 1958

', London, Macmillan, 1959 * ''

St Austell

Saint Austell (, ; ) is a town in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom, south of Bodmin and west of the border with Devon.

At the 2021 Census in the United Kingdom, census it had a population of 20,900.

History

St Austell was a village centred ...

: Church, Town, Parish'', St Austell: H. E. Warne, 1960

* '' All Souls and Appeasement

Appeasement, in an International relations, international context, is a diplomacy, diplomatic negotiation policy of making political, material, or territorial concessions to an aggressive power (international relations), power with intention t ...

: a Contribution to Contemporary History'', London: Macmillan, 1961

* '' Ralegh and the Throckmortons'', London: Macmillan, 1962

* ''William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

: a Biography'', London: Macmillan, 1963

* ''Christopher Marlowe

Christopher Marlowe ( ; Baptism, baptised 26 February 156430 May 1593), also known as Kit Marlowe, was an English playwright, poet, and translator of the Elizabethan era. Marlowe is among the most famous of the English Renaissance theatre, Eli ...

: a biography'', London: Macmillan, 1964

* ''Shakespeare's Sonnets'', London: Macmillan, 19641984 3rd edition

* ''A Cornishman at

Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

'', London: Jonathan Cape, 1965

* ''Shakespeare's Southampton: Patron of Virginia'', London: Macmillan, 1965

* ''Bosworth Field and the Wars of the Roses

The Wars of the Roses, known at the time and in following centuries as the Civil Wars, were a series of armed confrontations, machinations, battles and campaigns fought over control of the English throne from 1455 to 1487. The conflict was fo ...

'', London: Macmillan, 1966

* ''Cornish Stories'', London: Macmillan, 1967

* ''A Cornish Anthology'', London: Macmillan, 1968

* ''The Cornish in America'', London: Macmillan, 1969

* ''The Elizabethan Renaissance: the Life of Society'', London: Macmillan, 1971

* ''The Elizabethan Renaissance: the Cultural Achievement'', London: Macmillan, 1972

* ''The Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic citadel and castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London, England. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamle ...

in the History of the Nation'', London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1972

* ''Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

The Man'', London: Macmillan, 1973

* ''Windsor Castle

Windsor Castle is a List of British royal residences, royal residence at Windsor, Berkshire, Windsor in the English county of Berkshire, about west of central London. It is strongly associated with the Kingdom of England, English and succee ...

In the History of the Nation'', London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1974

* ''Victorian and Edwardian Cornwall from old photographs'', London: Batsford, 1974 (Introduction and commentaries by Rowse; ten extracts from Betjeman)

* '' Simon Forman: Sex and Society in Shakespeare's Age'', London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1974

* ''Discoveries and Reviews: from Renaissance to Restoration'', London: Macmillan, 1975

* ''Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

: In the History of the Nation'', London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1975

* ''Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift (30 November 1667 – 19 October 1745) was an Anglo-Irish writer, essayist, satirist, and Anglican cleric. In 1713, he became the Dean (Christianity), dean of St Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin, and was given the sobriquet "Dean Swi ...

: Major Prophet'', London, Thames & Hudson, 1975

* ''A Cornishman Abroad'', London: Jonathan Cape, 1976

* ''Matthew Arnold

Matthew Arnold (24 December 1822 – 15 April 1888) was an English poet and cultural critic. He was the son of Thomas Arnold, the headmaster of Rugby School, and brother to both Tom Arnold (academic), Tom Arnold, literary professor, and Willi ...

: Poet and Prophet'', London: Thames & Hudson, 1976

* ''Homosexuals in History'', London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1977

* ''Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

the Elizabethan'', London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1977

* '' Milton the Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to rid the Church of England of what they considered to be Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should b ...

: Portrait of a Mind'', London: Macmillan, 1977

* ''The Byrons and the Trevanions'', London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1978

* ''A Man of the Thirties'', London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1979

* ''Memories of Men and Women'', London: Eyre Methuen, 1980

* ''A Man of Singular Virtue: being a Life of Sir Thomas More by his Son-in-Law William Roper, and a Selection of More's Letters'', London: Folio Society, 1980 (Editor)

* ''Shakespeare's Globe: his Intellectual and Moral Outlook'', London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1981

* ''A Life: Collected Poems'', Edinburgh: William Blackwood, 1981

* ''Eminent Elizabethans'', London: Macmillan, 1983

* ''Night at the Carn and Other Stories'', London: William Kimber, 1984

* ''Shakespeare's Characters: a Complete Guide'', London: Methuen, 1984

* ''Glimpses of the Great'', London: Methuen, 1985

* ''The Little Land of Cornwall'', Gloucester: Alan Sutton, 1986

* ''A Quartet of Cornish Cats'', London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1986

* ''Stories From Trenarren'', London: William Kimber, 1986

* ''Reflections on the Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to rid the Church of England of what they considered to be Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should b ...

Revolution'', London: Methuen, 1986

* ''The Poet Auden: a Personal Memoir'', London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1987abstract with table of contents, Taylor & Francis website

* ''Court and Country: Studies in Tudor Social History'', Brighton: Harvester Press, 1987 * '' Froude the Historian: Victorian Man of Letters'', Gloucester: Alan Sutton, 1987 * '' Quiller-Couch: a Portrait of "Q"'', London: Methuen, 1988 * ''A. L. Rowse's Cornwall: a Journey through Cornwall's Past and Present'', London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1988 * ''Friends and Contemporaries'', London: Methuen, 1989 * ''The Controversial Colensos'', Redruth: Dyllansow Truran, 1989 * ''Discovering

Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

: a Chapter in Literary History'', London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1989

* ''Four Caroline Portraits'', London: Duckworth, 1993

* '' All Souls in My Time'', London: Duckworth, 1993

* ''The Regicides and the Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to rid the Church of England of what they considered to be Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should b ...

Revolution'', London: Duckworth, 1994

* ''Historians I Have Known'', London: Duckworth, 1995

* ''My View of Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

'', London: Duckworth, 1996

* ''Cornish Place Rhymes'', Tiverton: Cornwall Books, 1997 (posthumous commemorative volume begun by the author; preface by the editor, S. Butler)

* ''The Elizabethan Age'' (a four-volume set composed of ''The England of Elizabeth''; ''The Expansion of Elizabethan England''; ''The Elizabethan Renaissance: The Life of the Society''; ''The Elizabethan Renaissance: The Cultural Achievement''), London: Folio Society, 2012

Biography and bibliography

* * Capstick, Tony (1997), ''A. L. Rowse: An Illustrated Bibliography'', Wokingham: Hare's Ear Publication * Cauveren, Sydney (2000),A. L. Rowse: A Bibliophile's Extensive Bibliography

', Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press * Cauveren, Sydney (2001), "A. L. Rowse: Historian and Friend", ''

Contemporary Review

''The Contemporary Review'' is a British biannual, formerly quarterly, magazine. It has an uncertain future as of 2013.

History

The magazine was established in 1866 by Alexander Strahan and a group of intellectuals intent on promoting their v ...

'', December 2001, pp. 340–346

* Jacob, Valerie (2001), ''Tregonissey to Trenarren: A. L. Rowse – The Cornish Years'', St. Austell: Valerie Jacob

*

* Ollard, Richard (2003), ''The Diaries of A. L. Rowse'', London: Allen Lane

* Whetter, James (2003), ''Dr. A. L. Rowse: Poet, Historian, Lover of Cornwall'', Gorran, St. Austell: Lyfrow Trelyspen

* Payton, Philip (2005), ''A. L. Rowse and Cornwall'', Exeter: University of Exeter Press

* Donald Adamson is due to publish a biography of A. L. Rowse (from a friend's perspective), searticle in the ''International Literary Quarterly''

* Slattery-Christy, David (2017)

Other People's Fu**ing! An Oxford Affair

New play exploring the relationship between A.L. Rowse and Adam von Trott during the 1930s in Oxford. Published by Christyplays. www.christyplays.com

References

External links

*Papers of A L Rowse: research, literary and personal manuscripts at the University of Exeter

{{DEFAULTSORT:Rowse, A. L. 1903 births 1997 deaths 20th-century English biographers 20th-century English historians 20th-century English poets 20th-century English male writers Academics of the London School of Economics Alumni of Christ Church, Oxford Bards of Gorsedh Kernow Burials in Cornwall English LGBTQ poets English LGBTQ politicians English book and manuscript collectors English gay writers Fellows of All Souls College, Oxford Fellows of the British Academy Fellows of the Royal Historical Society Fellows of the Royal Society of Literature Historians of Cornwall Labour Party (UK) parliamentary candidates Members of the Order of the Companions of Honour People educated at St Austell Grammar School People from St Austell Poets from Cornwall Shakespearean scholars People associated with Merton College, Oxford People associated with the Huntington Library Historians of the University of Oxford English literary historians Historians of English literature