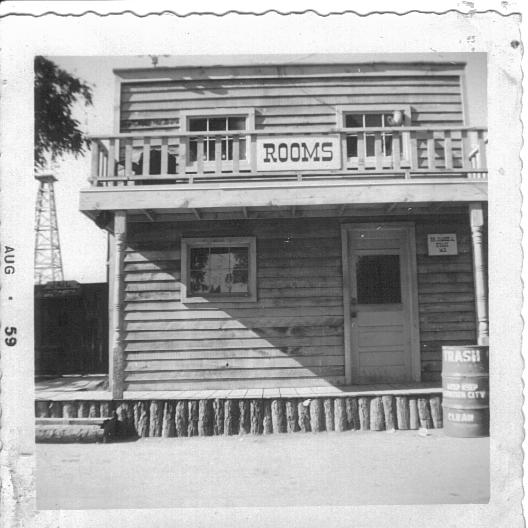

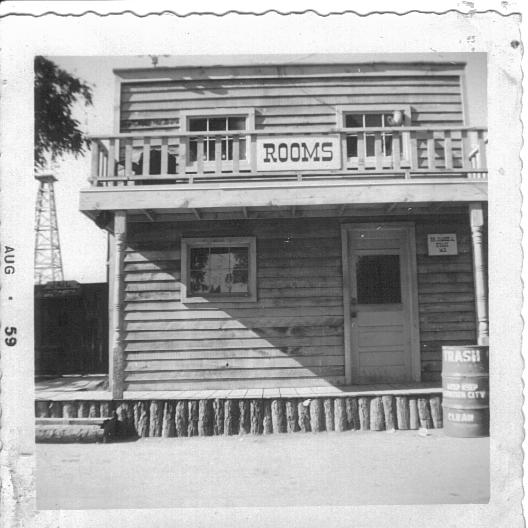

Rooming House on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A rooming house, also called a "multi-tenant house", is a "dwelling with multiple rooms rented out individually", in which the tenants share kitchen and often bathroom facilities. Rooming houses are often used as housing for low-income people, as rooming houses (along with single room occupancy units in hotels) are the least expensive housing for single adults. Rooming houses are usually owned and operated by private landlords. Rooming houses are better described as a "living arrangement" rather than a specially "built form" of housing; rooming houses involve people who are not related living together, often in an existing house, and sharing a kitchen, bathroom (in most cases), and in some cases a living room or dining room. Rooming houses in this way are similar to group homes and other roommate situations. While there are purpose-built rooming houses, these are rare.

A rooming house, also called a "multi-tenant house", is a "dwelling with multiple rooms rented out individually", in which the tenants share kitchen and often bathroom facilities. Rooming houses are often used as housing for low-income people, as rooming houses (along with single room occupancy units in hotels) are the least expensive housing for single adults. Rooming houses are usually owned and operated by private landlords. Rooming houses are better described as a "living arrangement" rather than a specially "built form" of housing; rooming houses involve people who are not related living together, often in an existing house, and sharing a kitchen, bathroom (in most cases), and in some cases a living room or dining room. Rooming houses in this way are similar to group homes and other roommate situations. While there are purpose-built rooming houses, these are rare.

Prior to the 1920s, commercial rooming houses were often former boardinghouses. After the US Civil War, boarding houses became less common, declining from 40% of rental listings in 1875 (in San Francisco) to 10% in 1900, and less than 1% by 1910.Groth, Paul. Living Downtown: The History of Residential Hotels in the United States. Chapter Four—Rooming Houses and the Margins of Respectability. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft6j49p0wf/ One reason for this change was that in the decades after the 1880s, urban reformers began working on modernizing cities; their efforts to create "uniformity within areas, less mixture of social classes, maximum privacy for each family, much lower density for many activities, buildings set back from the street, and a permanently built order" all meant that housing for single people had to be cut back or eliminated. By the early 1930s, urban reformers were typically using codes and zoning to enforce "uniform and protected single-use residential district of private houses", the reformers' preferred housing type. In 1936, the FHA Property Standards defined a dwelling as "any structure used principally for residential purposes", noting that "commercial rooming houses and tourist homes, sanitariums, tourist cabins, clubs, or fraternities would not be considered dwellings" as they did not have the "private kitchen and a private bath" that reformers viewed as essential in a "proper home".

The FHA rules called the existence of stores, offices or rental housing as "adverse influences" and "undesirable community conditions", which reduced the investment and repair support provided in any neighbourhood that deviated from the preferred single-family-home use. Land use reformers also passed zoning rules that indirectly reduced rooming houses: banning mixed residential and commercial use in neighbourhoods, an approach which meant that any remaining rooming house residents would find it hard to eat at a local cafe or walk to a nearby corner grocery to buy food. Non-residential uses such as religious institutions (churches) and professional offices (doctors, lawyers) were still permitted under these new zoning rules, but working-class people (plumbers, mechanics) were not allowed to operate their businesses.

By 1910, commercial rooming houses began to resemble an "inexpensive hotel", with multi-story buildings, often 25 to 40 years old, with the owners using the house as an income property. The operators, typically former boarding house managers, were getting out of the business of providing meals. This enabled the owner to convert the shared dining room and parlour into additional rental rooms and stop paying for the preparation of meals. There were often sixteen to eighteen rooms, with either central heating or tiny in-room heating stoves. A single bathroom was usually provided, with hot water only available on certain days and limits to the number of baths allowed per week. Blacks were not allowed in most rooming houses, due to segregation, except in black rooming houses. Old run-down hotels were converted into rooming houses. Some entrepreneurs even converted empty warehouses into inexpensive rooming houses. Prior to 1900, elevators were rare, so rooming house residents had to climb stairs. The hasty conversion of old houses and warehouses into blocks of rooms typically meant that the walls were thin, so residents could hear each other.

A study of San Francisco rooming houses in 1926 found rough living conditions:

Prior to the 1920s, commercial rooming houses were often former boardinghouses. After the US Civil War, boarding houses became less common, declining from 40% of rental listings in 1875 (in San Francisco) to 10% in 1900, and less than 1% by 1910.Groth, Paul. Living Downtown: The History of Residential Hotels in the United States. Chapter Four—Rooming Houses and the Margins of Respectability. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft6j49p0wf/ One reason for this change was that in the decades after the 1880s, urban reformers began working on modernizing cities; their efforts to create "uniformity within areas, less mixture of social classes, maximum privacy for each family, much lower density for many activities, buildings set back from the street, and a permanently built order" all meant that housing for single people had to be cut back or eliminated. By the early 1930s, urban reformers were typically using codes and zoning to enforce "uniform and protected single-use residential district of private houses", the reformers' preferred housing type. In 1936, the FHA Property Standards defined a dwelling as "any structure used principally for residential purposes", noting that "commercial rooming houses and tourist homes, sanitariums, tourist cabins, clubs, or fraternities would not be considered dwellings" as they did not have the "private kitchen and a private bath" that reformers viewed as essential in a "proper home".

The FHA rules called the existence of stores, offices or rental housing as "adverse influences" and "undesirable community conditions", which reduced the investment and repair support provided in any neighbourhood that deviated from the preferred single-family-home use. Land use reformers also passed zoning rules that indirectly reduced rooming houses: banning mixed residential and commercial use in neighbourhoods, an approach which meant that any remaining rooming house residents would find it hard to eat at a local cafe or walk to a nearby corner grocery to buy food. Non-residential uses such as religious institutions (churches) and professional offices (doctors, lawyers) were still permitted under these new zoning rules, but working-class people (plumbers, mechanics) were not allowed to operate their businesses.

By 1910, commercial rooming houses began to resemble an "inexpensive hotel", with multi-story buildings, often 25 to 40 years old, with the owners using the house as an income property. The operators, typically former boarding house managers, were getting out of the business of providing meals. This enabled the owner to convert the shared dining room and parlour into additional rental rooms and stop paying for the preparation of meals. There were often sixteen to eighteen rooms, with either central heating or tiny in-room heating stoves. A single bathroom was usually provided, with hot water only available on certain days and limits to the number of baths allowed per week. Blacks were not allowed in most rooming houses, due to segregation, except in black rooming houses. Old run-down hotels were converted into rooming houses. Some entrepreneurs even converted empty warehouses into inexpensive rooming houses. Prior to 1900, elevators were rare, so rooming house residents had to climb stairs. The hasty conversion of old houses and warehouses into blocks of rooms typically meant that the walls were thin, so residents could hear each other.

A study of San Francisco rooming houses in 1926 found rough living conditions:

However, with the boom in housing in the 1950s, middle class newcomers could increasingly afford their own homes or apartments, which meant that rooming and boarding houses became used mainly by post-secondary "students, the working poor, or the unemployed". By the 1960s, rooming and boarding houses were deteriorating, as official city policies tended to ignore them. By the 1970s, investors started buying up city houses, turning them into temporary rooming houses to make rental income until the desired price in the housing market for selling off the properties was reached, a process called gentrification . From 1977 to 1987, Montreal lost about 40% of its rooming houses, which has created a shortage in affordable housing for low-income people.

By 2014, rooming houses were disappearing from Winnipeg due to a complicated regulatory framework involving multiple government departments and "market pressure" in the housing market. A 2014 report about Toronto rooming houses noted the increase in suburban rooming houses, often in basements; this change challenges the perception that rooming houses are just an inner city phenomenon.

However, with the boom in housing in the 1950s, middle class newcomers could increasingly afford their own homes or apartments, which meant that rooming and boarding houses became used mainly by post-secondary "students, the working poor, or the unemployed". By the 1960s, rooming and boarding houses were deteriorating, as official city policies tended to ignore them. By the 1970s, investors started buying up city houses, turning them into temporary rooming houses to make rental income until the desired price in the housing market for selling off the properties was reached, a process called gentrification . From 1977 to 1987, Montreal lost about 40% of its rooming houses, which has created a shortage in affordable housing for low-income people.

By 2014, rooming houses were disappearing from Winnipeg due to a complicated regulatory framework involving multiple government departments and "market pressure" in the housing market. A 2014 report about Toronto rooming houses noted the increase in suburban rooming houses, often in basements; this change challenges the perception that rooming houses are just an inner city phenomenon.

A rooming house, also called a "multi-tenant house", is a "dwelling with multiple rooms rented out individually", in which the tenants share kitchen and often bathroom facilities. Rooming houses are often used as housing for low-income people, as rooming houses (along with single room occupancy units in hotels) are the least expensive housing for single adults. Rooming houses are usually owned and operated by private landlords. Rooming houses are better described as a "living arrangement" rather than a specially "built form" of housing; rooming houses involve people who are not related living together, often in an existing house, and sharing a kitchen, bathroom (in most cases), and in some cases a living room or dining room. Rooming houses in this way are similar to group homes and other roommate situations. While there are purpose-built rooming houses, these are rare.

A rooming house, also called a "multi-tenant house", is a "dwelling with multiple rooms rented out individually", in which the tenants share kitchen and often bathroom facilities. Rooming houses are often used as housing for low-income people, as rooming houses (along with single room occupancy units in hotels) are the least expensive housing for single adults. Rooming houses are usually owned and operated by private landlords. Rooming houses are better described as a "living arrangement" rather than a specially "built form" of housing; rooming houses involve people who are not related living together, often in an existing house, and sharing a kitchen, bathroom (in most cases), and in some cases a living room or dining room. Rooming houses in this way are similar to group homes and other roommate situations. While there are purpose-built rooming houses, these are rare.

Condition

A study of rooming houses in Ottawa, Ontario in 2016 found that "many units are in very poor condition", with issues such as mould, cockroaches, bedbugs, and broken locks. An article about Montreal rooming houses stated that the units often contain bedbugs and "faulty plumbing". Rooming houses tend to be located in places close to access, amenities and markets. Specialist builders tend to build up to nine high-standard, low-maintenance micro apartments where once a single occupancy dwelling would have returned just one rental.Residents

In one Ottawa study, more than 50% of the occupants in rooming houses were found to have mental health diagnoses. A 1998 study of Toronto rooming house residents found that they had poorer health than the general population and low incomes. A study of 295 residents from 171 rooming houses in Toronto found that "residents aged 35 years and older had significantly poorer health status than their counterparts in the Canadian general population" and the residents had a "high prevalence of ill health", with the worst-off residents (from a health perspective) living in the poorest-maintained and most substandard rooming houses. An article about rooming houses in Montreal stated that rooming houses are the "last stop before the street" for low-income people at risk of homelessness.Government intervention

Regulations

Not all rooming houses are legal, inspected units, as some landlords also rent out unlicensed rooms. In Winnipeg, four branches of city government regulate rooming houses: a licensing branch, a business branch, a "livability" living standards bylaw and the fire prevention branch. The livability standards bylaw requires at least one bathroom for 10 residents (some health researchers have called for one bathroom for every four tenants). Despite efforts by the city of Toronto to regulate rooming houses, there is an invisible, unregistered rooming house sector, which are advertised online or on bulletin boards, often in suburban basements which are subdivided into rooms. Increasing regulation of rooming houses can lead to a decline in the number of rooming houses that are available, as landlords may choose not to apply for and pay the fees for a city licence, and complete the needed safety requirements (sprinklers, fire escapes, etc.). In 2018, the city of Ottawa (Ontario) created rules to limit the number of bedrooms in newly built houses, to prevent the creation of houses with five to eight bedrooms, which can become illegal rooming houses, colloquially known as "bunkhouses".Subsidies

In New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Manitoba, the provincial government have funding programs that provides financial assistance to owners and landlords of rooming houses that serve low-income people; the funding must be used to do repairs of a structural, electrical, plumbing, or fire safety nature.History

Prior to the 1920s, commercial rooming houses were often former boardinghouses. After the US Civil War, boarding houses became less common, declining from 40% of rental listings in 1875 (in San Francisco) to 10% in 1900, and less than 1% by 1910.Groth, Paul. Living Downtown: The History of Residential Hotels in the United States. Chapter Four—Rooming Houses and the Margins of Respectability. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft6j49p0wf/ One reason for this change was that in the decades after the 1880s, urban reformers began working on modernizing cities; their efforts to create "uniformity within areas, less mixture of social classes, maximum privacy for each family, much lower density for many activities, buildings set back from the street, and a permanently built order" all meant that housing for single people had to be cut back or eliminated. By the early 1930s, urban reformers were typically using codes and zoning to enforce "uniform and protected single-use residential district of private houses", the reformers' preferred housing type. In 1936, the FHA Property Standards defined a dwelling as "any structure used principally for residential purposes", noting that "commercial rooming houses and tourist homes, sanitariums, tourist cabins, clubs, or fraternities would not be considered dwellings" as they did not have the "private kitchen and a private bath" that reformers viewed as essential in a "proper home".

The FHA rules called the existence of stores, offices or rental housing as "adverse influences" and "undesirable community conditions", which reduced the investment and repair support provided in any neighbourhood that deviated from the preferred single-family-home use. Land use reformers also passed zoning rules that indirectly reduced rooming houses: banning mixed residential and commercial use in neighbourhoods, an approach which meant that any remaining rooming house residents would find it hard to eat at a local cafe or walk to a nearby corner grocery to buy food. Non-residential uses such as religious institutions (churches) and professional offices (doctors, lawyers) were still permitted under these new zoning rules, but working-class people (plumbers, mechanics) were not allowed to operate their businesses.

By 1910, commercial rooming houses began to resemble an "inexpensive hotel", with multi-story buildings, often 25 to 40 years old, with the owners using the house as an income property. The operators, typically former boarding house managers, were getting out of the business of providing meals. This enabled the owner to convert the shared dining room and parlour into additional rental rooms and stop paying for the preparation of meals. There were often sixteen to eighteen rooms, with either central heating or tiny in-room heating stoves. A single bathroom was usually provided, with hot water only available on certain days and limits to the number of baths allowed per week. Blacks were not allowed in most rooming houses, due to segregation, except in black rooming houses. Old run-down hotels were converted into rooming houses. Some entrepreneurs even converted empty warehouses into inexpensive rooming houses. Prior to 1900, elevators were rare, so rooming house residents had to climb stairs. The hasty conversion of old houses and warehouses into blocks of rooms typically meant that the walls were thin, so residents could hear each other.

A study of San Francisco rooming houses in 1926 found rough living conditions:

Prior to the 1920s, commercial rooming houses were often former boardinghouses. After the US Civil War, boarding houses became less common, declining from 40% of rental listings in 1875 (in San Francisco) to 10% in 1900, and less than 1% by 1910.Groth, Paul. Living Downtown: The History of Residential Hotels in the United States. Chapter Four—Rooming Houses and the Margins of Respectability. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft6j49p0wf/ One reason for this change was that in the decades after the 1880s, urban reformers began working on modernizing cities; their efforts to create "uniformity within areas, less mixture of social classes, maximum privacy for each family, much lower density for many activities, buildings set back from the street, and a permanently built order" all meant that housing for single people had to be cut back or eliminated. By the early 1930s, urban reformers were typically using codes and zoning to enforce "uniform and protected single-use residential district of private houses", the reformers' preferred housing type. In 1936, the FHA Property Standards defined a dwelling as "any structure used principally for residential purposes", noting that "commercial rooming houses and tourist homes, sanitariums, tourist cabins, clubs, or fraternities would not be considered dwellings" as they did not have the "private kitchen and a private bath" that reformers viewed as essential in a "proper home".

The FHA rules called the existence of stores, offices or rental housing as "adverse influences" and "undesirable community conditions", which reduced the investment and repair support provided in any neighbourhood that deviated from the preferred single-family-home use. Land use reformers also passed zoning rules that indirectly reduced rooming houses: banning mixed residential and commercial use in neighbourhoods, an approach which meant that any remaining rooming house residents would find it hard to eat at a local cafe or walk to a nearby corner grocery to buy food. Non-residential uses such as religious institutions (churches) and professional offices (doctors, lawyers) were still permitted under these new zoning rules, but working-class people (plumbers, mechanics) were not allowed to operate their businesses.

By 1910, commercial rooming houses began to resemble an "inexpensive hotel", with multi-story buildings, often 25 to 40 years old, with the owners using the house as an income property. The operators, typically former boarding house managers, were getting out of the business of providing meals. This enabled the owner to convert the shared dining room and parlour into additional rental rooms and stop paying for the preparation of meals. There were often sixteen to eighteen rooms, with either central heating or tiny in-room heating stoves. A single bathroom was usually provided, with hot water only available on certain days and limits to the number of baths allowed per week. Blacks were not allowed in most rooming houses, due to segregation, except in black rooming houses. Old run-down hotels were converted into rooming houses. Some entrepreneurs even converted empty warehouses into inexpensive rooming houses. Prior to 1900, elevators were rare, so rooming house residents had to climb stairs. The hasty conversion of old houses and warehouses into blocks of rooms typically meant that the walls were thin, so residents could hear each other.

A study of San Francisco rooming houses in 1926 found rough living conditions:

"There were dark rooms where it was impossible to find the washstand without first turning on electric light; dingy rooms where the carpets had a musty smell, and the furniture was shabby and faded; sleeping rooms with lumpy double beds and dirty lace curtains. . . . Most of the rooms had such dim lights that no one could read in the evening."Before the 1920s, the wages for women working as seamstresses or servers was often too low for them to afford their own room, so often women shared a room with another woman. Due to the sectors where rooming house residents lived, they often had to move, either due to seeking new jobs, because of seasonal work or due to layoffs, which meant that the tenants in a rooming house would change throughout a year. As such, rooming house residents tended to have only one or two bags or a single trunk of possessions. Another change between the 19th century and the turn of the 20th century was the separation of rooming houses according to religion (Catholic, Protestant), ethnic origin (Irish) or occupation (mechanics, cooks); while this was common in the 19th century, it became less common in the early 20th century. In rooming houses in the 20th century, homosexual couples of men or women could live together if they appeared to be friends sharing a room and unmarried heterosexual couples could share a room without disapproval. With the removal of the meal service of boarding houses, rooming houses needed to be near diners and other inexpensive food businesses. Rooming houses attracted criticism: in "1916, Walter Krumwilde, a Protestant minister, saw the rooming house or boardinghouse system s"spreading its web like a spider, stretching out its arms like an octopus to catch the unwary soul." In the 1930s and 1940s, "rooming or boarding houses had been taken for granted as respectable places for students, single workers, immigrants, and newlyweds to live when they left home or came to the city". In Toronto, rooming houses were common in the 1930s, during the Great Depression, because "wealthy homeowners" who had guest houses would rent out empty rooms to be able to keep their homes. After WWII, the city ensured that rooming house spaces were available for returning soldiers. In 1949, a sociologist called a Los Angeles rooming house neighbourhood a "universe of anonymous transients." Since traditional class roles were based around home and family, residents in rooming houses did not fit into working class, middle class or upper class patterns; instead, they were in a sort of "social and cultural limbo", with many hoping to rise.

However, with the boom in housing in the 1950s, middle class newcomers could increasingly afford their own homes or apartments, which meant that rooming and boarding houses became used mainly by post-secondary "students, the working poor, or the unemployed". By the 1960s, rooming and boarding houses were deteriorating, as official city policies tended to ignore them. By the 1970s, investors started buying up city houses, turning them into temporary rooming houses to make rental income until the desired price in the housing market for selling off the properties was reached, a process called gentrification . From 1977 to 1987, Montreal lost about 40% of its rooming houses, which has created a shortage in affordable housing for low-income people.

By 2014, rooming houses were disappearing from Winnipeg due to a complicated regulatory framework involving multiple government departments and "market pressure" in the housing market. A 2014 report about Toronto rooming houses noted the increase in suburban rooming houses, often in basements; this change challenges the perception that rooming houses are just an inner city phenomenon.

However, with the boom in housing in the 1950s, middle class newcomers could increasingly afford their own homes or apartments, which meant that rooming and boarding houses became used mainly by post-secondary "students, the working poor, or the unemployed". By the 1960s, rooming and boarding houses were deteriorating, as official city policies tended to ignore them. By the 1970s, investors started buying up city houses, turning them into temporary rooming houses to make rental income until the desired price in the housing market for selling off the properties was reached, a process called gentrification . From 1977 to 1987, Montreal lost about 40% of its rooming houses, which has created a shortage in affordable housing for low-income people.

By 2014, rooming houses were disappearing from Winnipeg due to a complicated regulatory framework involving multiple government departments and "market pressure" in the housing market. A 2014 report about Toronto rooming houses noted the increase in suburban rooming houses, often in basements; this change challenges the perception that rooming houses are just an inner city phenomenon.

See also

* House in multiple occupation, UK-specific term for rooming houses with specific legislationFurther reading

* Distasio, J., Dudley, M., Maunder, M. (2002). ''Out of the Long Dark Hallway: Voices from Winnipeg’s Rooming Houses''. Social Services and Humanities Research Council of Canada. * Mifflin, E., & Wilton, R. (2005). "No place like home: Rooming houses in contemporary urban context". ''Environment and Planning'', 37, 403–421.References

{{reflist House types Affordable housing Living arrangements