Richard O'Connor on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

At the end of the war, O'Connor reverted to his rank of captain and served as regimental adjutant from April to December 1919.

Italy declared war on Britain and France on 10 June 1940 and, soon after, O'Connor was appointed commander of the

Italy declared war on Britain and France on 10 June 1940 and, soon after, O'Connor was appointed commander of the  During November, O'Connor was appointed an acting lieutenant-general in recognition of the increased size of his command.

The counteroffensive,

During November, O'Connor was appointed an acting lieutenant-general in recognition of the increased size of his command.

The counteroffensive,  In early January 1941, the Western Desert Force was redesignated XIII Corps. On 9 January, the offensive resumed. By 12 January the strategic fortress port of

In early January 1941, the Western Desert Force was redesignated XIII Corps. On 9 January, the offensive resumed. By 12 January the strategic fortress port of

On 21 January 1944 O'Connor became commander of VIII Corps, which consisted of the Guards Armoured Division, 11th Armoured Division, 15th (Scottish) Infantry Division, along with 6th Guards Tank Brigade, 8th Army Group Royal Artillery and 2nd Household Cavalry Regiment. The corps formed part of the

On 21 January 1944 O'Connor became commander of VIII Corps, which consisted of the Guards Armoured Division, 11th Armoured Division, 15th (Scottish) Infantry Division, along with 6th Guards Tank Brigade, 8th Army Group Royal Artillery and 2nd Household Cavalry Regiment. The corps formed part of the

General

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

Sir Richard Nugent O'Connor, (21 August 1889 – 17 June 1981) was a senior British Army

The British Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of the United Kingdom. the British Army comprises 73,847 regular full-time personnel, 4,127 Brigade of Gurkhas, Gurkhas, 25,742 Army Reserve (United Kingdom), volunteer reserve perso ...

officer

An officer is a person who has a position of authority in a hierarchical organization. The term derives from Old French ''oficier'' "officer, official" (early 14c., Modern French ''officier''), from Medieval Latin ''officiarius'' "an officer," fro ...

who fought in both the First and Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

s, and commanded the Western Desert Force

The Western Desert Force (WDF) was a British Army formation active in Egypt during the Western Desert Campaign of the Second World War.

On 17 June 1940, the headquarters of the British 6th Infantry Division was designated as the Western Des ...

in the early years of the Second World War. He was the field commander for Operation Compass

Operation Compass (also ) was the first large British military operation of the Western Desert Campaign (1940–1943) during the Second World War. British metropolitan, Imperial and Commonwealth forces attacked the Italian and Libyan forces of ...

, in which his forces destroyed a much larger Italian army

The Italian Army ( []) is the Army, land force branch of the Italian Armed Forces. The army's history dates back to the Italian unification in the 1850s and 1860s. The army fought in colonial engagements in China and Italo-Turkish War, Libya. It ...

– a victory which nearly drove the Axis

An axis (: axes) may refer to:

Mathematics

*A specific line (often a directed line) that plays an important role in some contexts. In particular:

** Coordinate axis of a coordinate system

*** ''x''-axis, ''y''-axis, ''z''-axis, common names ...

from Africa, and in turn, led Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

to send the Afrika Korps

The German Africa Corps (, ; DAK), commonly known as Afrika Korps, was the German expeditionary force in Africa during the North African campaign of World War II. First sent as a holding force to shore up the Italian defense of its Africa ...

under Erwin Rommel

Johannes Erwin Eugen Rommel (; 15 November 1891 – 14 October 1944), popularly known as The Desert Fox (, ), was a German '' Generalfeldmarschall'' (field marshal) during World War II. He served in the ''Wehrmacht'' (armed forces) of ...

to try to reverse the situation. O'Connor was captured by an Italian reconnaissance patrol during the night of 7 April 1941 and spent over two years in an Italian prisoner of war camp

A prisoner-of-war camp (often abbreviated as POW camp) is a site for the containment of enemy fighters captured as prisoners of war by a belligerent power in time of war.

There are significant differences among POW camps, internment camps, ...

. He eventually escaped after the fall of Mussolini in the autumn of 1943. In 1944 he commanded VIII Corps in the Battle of Normandy

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the Allied operation that launched the successful liberation of German-occupied Western Europe during World War II. The operation was launched on 6 June 1944 (D-Day) with the N ...

and later during Operation Market Garden. In 1945 he was General Officer in Command of the Eastern Command in India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

and then, in the closing days of British rule in the subcontinent, he headed Northern Command. His final job in the army was Adjutant-General to the Forces

The Adjutant-General to the Forces, commonly just referred to as the Adjutant-General (AG), was for just over 250 years one of the most senior officers in the British Army. The AG was latterly responsible for developing the Army's personnel polic ...

in London, in charge of the British Army's administration, personnel and organisation.

In honour of his war service, O'Connor was recognised with the highest level of knighthood

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of a knighthood by a head of state (including the pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church, or the country, especially in a military capacity.

The concept of a knighthood ...

in two different orders of chivalry

An order of chivalry, order of knighthood, chivalric order, or equestrian order is a society, fellowship and college of knights, typically founded during or inspired by the original Catholic military orders of the Crusades ( 1099–1291) and p ...

. He was also awarded the Distinguished Service Order

The Distinguished Service Order (DSO) is a Military awards and decorations, military award of the United Kingdom, as well as formerly throughout the Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth, awarded for operational gallantry for highly successful ...

(twice), the Military Cross

The Military Cross (MC) is the third-level (second-level until 1993) military decoration awarded to officers and (since 1993) Other ranks (UK), other ranks of the British Armed Forces, and formerly awarded to officers of other Commonwealth of ...

, the French Croix de Guerre

The (, ''Cross of War'') is a military decoration of France. It was first created in 1915 and consists of a square-cross medal on two crossed swords, hanging from a ribbon with various degree pins. The decoration was first awarded during World ...

and the Legion of Honour

The National Order of the Legion of Honour ( ), formerly the Imperial Order of the Legion of Honour (), is the highest and most prestigious French national order of merit, both military and Civil society, civil. Currently consisting of five cl ...

, and served as aide-de-camp to King George VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until his death in 1952. He was also the last Emperor of In ...

. He was also mentioned in despatches

To be mentioned in dispatches (or despatches) describes a member of the armed forces whose name appears in an official report written by a superior officer and sent to the high command, in which their gallant or meritorious action in the face of t ...

nine times for actions in the First World War, once in Palestine

Palestine, officially the State of Palestine, is a country in West Asia. Recognized by International recognition of Palestine, 147 of the UN's 193 member states, it encompasses the Israeli-occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and th ...

in 1939 and three times in the Second World War.

Early life

Richard Nugent O'Connor was born inSrinagar

Srinagar (; ) is a city in Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir in the disputed Kashmir region.The application of the term "administered" to the various regions of Kashmir and a mention of the Kashmir dispute is supported by the tertiary ...

, Kashmir

Kashmir ( or ) is the Northwestern Indian subcontinent, northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term ''Kashmir'' denoted only the Kashmir Valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir P ...

, India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

, on 21 August 1889. His father, Maurice O'Connor, was a major

Major most commonly refers to:

* Major (rank), a military rank

* Academic major, an academic discipline to which an undergraduate student formally commits

* People named Major, including given names, surnames, nicknames

* Major and minor in musi ...

in the Royal Irish Fusiliers

The Royal Irish Fusiliers (Princess Victoria's) was an Irish line infantry (later changed to light infantry) regiment of the British Army, formed by the amalgamation of the 87th (Prince of Wales's Irish) Regiment of Foot and the 89th (Princess ...

, and his mother, Lilian Morris, was the daughter of a former governor of India's central provinces.Keegan (2005), p. 185 He attended Tonbridge

Tonbridge ( ) (historic spelling ''Tunbridge'') is a market town in Kent, England, on the River Medway, north of Royal Tunbridge Wells, south west of Maidstone and south east of London. In the administrative borough of Tonbridge and Mall ...

Castle School in 1899 and The Towers School in Crowthorne

Crowthorne is a village, and civil parish, in the Bracknell Forest district of southeastern Berkshire, England. It had a population of 7,806 at the United Kingdom Census 2021, 2021 census.

Crowthorne is the location of Wellington College, Be ...

in 1902. In 1903, aged 13, and after his father's death in an accident, he moved to Wellington College. "His career there was not distinguished in any way", however, although he enjoyed his time there.

Following this, he went to the Royal Military College at Sandhurst in January 1908. Despite his success in later life, his time there, as at Wellington (only a few miles away from Sandhurst), was not remarkable, and he did not mention his time there even in his later life. A year ahead of him at the college was a man who would play a significant role in O'Connor's future military career and life. This was Bernard Montgomery

Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, 1st Viscount Montgomery of Alamein (; 17 November 1887 – 24 March 1976), nicknamed "Monty", was a senior British Army officer who served in the First World War, the Irish War of Independence and the ...

, about two years older than O'Connor, although it is unknown if the two men knew of each other at this very early stage of their military careers.

Passing out 38th in the order of merit, in September of the following year O'Connor, anxious to join a Scottish regiment, was commissioned, as a second lieutenant and posted to the 2nd Battalion of his new regiment, Cameronians (Scottish Rifles)

The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) was a rifle regiment of the British Army, the only regiment of rifles amongst the Scottish regiments of infantry. It was formed in 1881 under the Childers Reforms by the amalgamation of the 26th Cameronian Reg ...

, the regiment of his choice, recruiting from Glasgow

Glasgow is the Cities of Scotland, most populous city in Scotland, located on the banks of the River Clyde in Strathclyde, west central Scotland. It is the List of cities in the United Kingdom, third-most-populous city in the United Kingdom ...

and Lanarkshire

Lanarkshire, also called the County of Lanark (; ), is a Counties of Scotland, historic county, Lieutenancy areas of Scotland, lieutenancy area and registration county in the Central Lowlands and Southern Uplands of Scotland. The county is no l ...

, and with which he was to maintain close ties with for the rest of his life. The battalion was initially stationed in Aldershot

Aldershot ( ) is a town in the Rushmoor district, Hampshire, England. It lies on heathland in the extreme north-east corner of the county, south-west of London. The town has a population of 37,131, while the Farnborough/Aldershot built-up are ...

when O'Connor joined them in October 1909 before being rotated, in January 1910, to Colchester

Colchester ( ) is a city in northeastern Essex, England. It is the second-largest settlement in the county, with a population of 130,245 at the 2021 United Kingdom census, 2021 Census. The demonym is ''Colcestrian''.

Colchester occupies the ...

. It was here where he received signals and rifle training, after attending courses for both, resulting in his being appointed a regimental signals officer for the former, and becoming a distinguished marksman after attending the Small Arms School at Hythe, Kent

Hythe () is an old market town and civil parish on the edge of Romney Marsh in Kent, England. ''Hythe'' is an Old English word meaning haven or landing place.

History

The earliest reference to Hythe is in Domesday Book (1086) though there i ...

. In September 1911 the battalion sailed for Malta

Malta, officially the Republic of Malta, is an island country in Southern Europe located in the Mediterranean Sea, between Sicily and North Africa. It consists of an archipelago south of Italy, east of Tunisia, and north of Libya. The two ...

where it was to remain for the next three years as part of a Malta brigade, with O'Connor, now a lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a Junior officer, junior commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations, as well as fire services, emergency medical services, Security agency, security services ...

(having been promoted to that rank in May), continuing in his role as regimental signals officer. By now it was becoming obvious that a war in Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

was on the horizon. As a result, for O'Connor, who at some point was appointed the Malta brigade's signals officer, the years of 1913 and 1914 were spent in training the men under his command for the duties that they would one day have to perform in battle.

First World War

During theFirst World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, O'Connor initially served as signals officer of the 22nd Brigade in the 7th Division and captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

in command of the 7th Division's Signals Company. From October 1916, as a captain and later as a brevet major, he served as brigade major of 91st Brigade, 7th Division. He was awarded the Military Cross

The Military Cross (MC) is the third-level (second-level until 1993) military decoration awarded to officers and (since 1993) Other ranks (UK), other ranks of the British Armed Forces, and formerly awarded to officers of other Commonwealth of ...

(MC) in February 1915. In March of that year he saw action at Arras

Arras ( , ; ; historical ) is the prefecture of the Pas-de-Calais department, which forms part of the region of Hauts-de-France; before the reorganization of 2014 it was in Nord-Pas-de-Calais. The historic centre of the Artois region, with a ...

and Bullecourt. O'Connor was awarded the Distinguished Service Order

The Distinguished Service Order (DSO) is a Military awards and decorations, military award of the United Kingdom, as well as formerly throughout the Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth, awarded for operational gallantry for highly successful ...

(DSO) and appointed brevet lieutenant-colonel while he was in command of the 2nd Infantry Battalion of the Honourable Artillery Company

The Honourable Artillery Company (HAC) is a reserve regiment in the British Army. Incorporated by royal charter in 1537 by King Henry VIII, it is the oldest regiment in the British Army and is considered the second-oldest military unit in the w ...

, part of the 7th Division, in June 1917. The citation for his DSO reads:

In November of that year, the division was ordered to support the Italians against the Austro-Hungarian

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military and diplomatic alliance, it consist ...

forces at the River Piave which then formed part of the Italian Front. In late October 1918 the 2nd Battalion captured the island of Grave di Papadopoli on the Piave River for which O'Connor received the Italian Silver Medal of Military Valor and a Bar to his DSO.Papers of General Sir Richard O'ConnorAt the end of the war, O'Connor reverted to his rank of captain and served as regimental adjutant from April to December 1919.

Between the wars

O'Connor attended theStaff College, Camberley

Staff College, Camberley, Surrey, was a staff college for the British Army and the presidency armies of British India (later merged to form the Indian Army). It had its origins in the Royal Military College, High Wycombe, founded in 1799, which ...

in 1920. O'Connor's other service in the years between the world war

A world war is an international War, conflict that involves most or all of the world's major powers. Conventionally, the term is reserved for two major international conflicts that occurred during the first half of the 20th century, World War I ...

s included an appointment from 1921 to 1924 as brigade major of the Experimental Brigade (or 5 Brigade) under the command of J. F. C. Fuller

Major-General John Frederick Charles "Boney" Fuller (1 September 1878 – 10 February 1966) was a senior British Army officer, military historian, and strategist, known as an early theorist of modern armoured warfare, including categorisin ...

, which was formed to test methods and procedures for using tank

A tank is an armoured fighting vehicle intended as a primary offensive weapon in front-line ground combat. Tank designs are a balance of heavy firepower, strong armour, and battlefield mobility provided by tracks and a powerful engine; ...

s and aircraft in co-ordination with infantry

Infantry, or infantryman are a type of soldier who specialize in ground combat, typically fighting dismounted. Historically the term was used to describe foot soldiers, i.e. those who march and fight on foot. In modern usage, the term broadl ...

and artillery

Artillery consists of ranged weapons that launch Ammunition, munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during sieges, and l ...

.

He returned to his old unit, the Cameronians (Scottish Rifles)

The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) was a rifle regiment of the British Army, the only regiment of rifles amongst the Scottish regiments of infantry. It was formed in 1881 under the Childers Reforms by the amalgamation of the 26th Cameronian Reg ...

, as adjutant

Adjutant is a military appointment given to an Officer (armed forces), officer who assists the commanding officer with unit administration, mostly the management of “human resources” in an army unit. The term is used in French-speaking armed ...

from February 1924 to 1925. From 1925 to 1927 he served as a company commander

A company is a military unit, typically consisting of 100–250 soldiers and usually commanded by a major or a captain. Most companies are made up of three to seven platoons, although the exact number may vary by country, unit type, and struc ...

at Sandhurst.Keegan (2005), p. 199 He returned to the Staff College, Camberley as an instructor from October 1927 to January 1930. In 1930 O'Connor again served with the 1st Battalion, Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) in Egypt and from 1931 to 1932 in Lucknow

Lucknow () is the List of state and union territory capitals in India, capital and the largest city of the List of state and union territory capitals in India, Indian state of Uttar Pradesh and it is the administrative headquarters of the epon ...

, India. From April 1932 to January 1935 he was a general staff officer, grade 2 at the War Office

The War Office has referred to several British government organisations throughout history, all relating to the army. It was a department of the British Government responsible for the administration of the British Army between 1857 and 1964, at ...

. He attended the Imperial Defence College in London in 1935. In April 1936 O'Connor was promoted to full colonel and appointed temporary brigadier

Brigadier ( ) is a military rank, the seniority of which depends on the country. In some countries, it is a senior rank above colonel, equivalent to a brigadier general or commodore (rank), commodore, typically commanding a brigade of several t ...

to assume command of the Peshawar Brigade in north west India. In September 1938 O'Connor was promoted to major-general and appointed General Officer Commanding

General officer commanding (GOC) is the usual title given in the armies of the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth (and some other nations, such as Ireland) to a general officer who holds a command appointment.

Thus, a general might be the GOC ...

7th Infantry Division in Palestine

Palestine, officially the State of Palestine, is a country in West Asia. Recognized by International recognition of Palestine, 147 of the UN's 193 member states, it encompasses the Israeli-occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and th ...

, along with the additional responsibility as Military Governor of Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

. For his services in Palestine O'Connor was mentioned in despatches.

In August 1939, shortly before the outbreak of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, the 7th Division was transferred to the fortress at Mersa Matruh

Mersa Matruh (), also transliterated as Marsa Matruh ( Standard Arabic ''Marsā Maṭrūḥ'', ), is a port in Egypt and the capital of Matrouh Governorate. It is located west of Alexandria and east of Sallum on the main highway from the Nile ...

, Egypt, where O'Connor was concerned with defending the area against a potential attack from the massed forces of the Italian Tenth Army over the border in Libya. The 7th Division later converted to become the 6th Division in November 1939. He was appointed a Companion of the Order of the Bath

Companion may refer to:

Relationships Currently

* Any of several interpersonal relationships such as friend or acquaintance

* A domestic partner, akin to a spouse

* Sober companion, an addiction treatment coach

* Companion (caregiving), a caregi ...

in July 1940.

Second World War

Italian Offensive and Operation Compass

Italy declared war on Britain and France on 10 June 1940 and, soon after, O'Connor was appointed commander of the

Italy declared war on Britain and France on 10 June 1940 and, soon after, O'Connor was appointed commander of the Western Desert Force

The Western Desert Force (WDF) was a British Army formation active in Egypt during the Western Desert Campaign of the Second World War.

On 17 June 1940, the headquarters of the British 6th Infantry Division was designated as the Western Des ...

. He was tasked by Lieutenant-General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the battlefield, who was normall ...

Henry Maitland Wilson

Field Marshal Henry Maitland Wilson, 1st Baron Wilson, (5 September 1881 – 31 December 1964), also known as Jumbo Wilson, was a senior British Army officer of the 20th century. He saw active service in the Second Boer War and then during the ...

, commander of the British troops in Egypt, to push the Italian force out of Egypt, to protect the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal (; , ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, Indo-Mediterranean, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia (and by extension, the Sinai Peninsula from the rest ...

and British interests from attack.

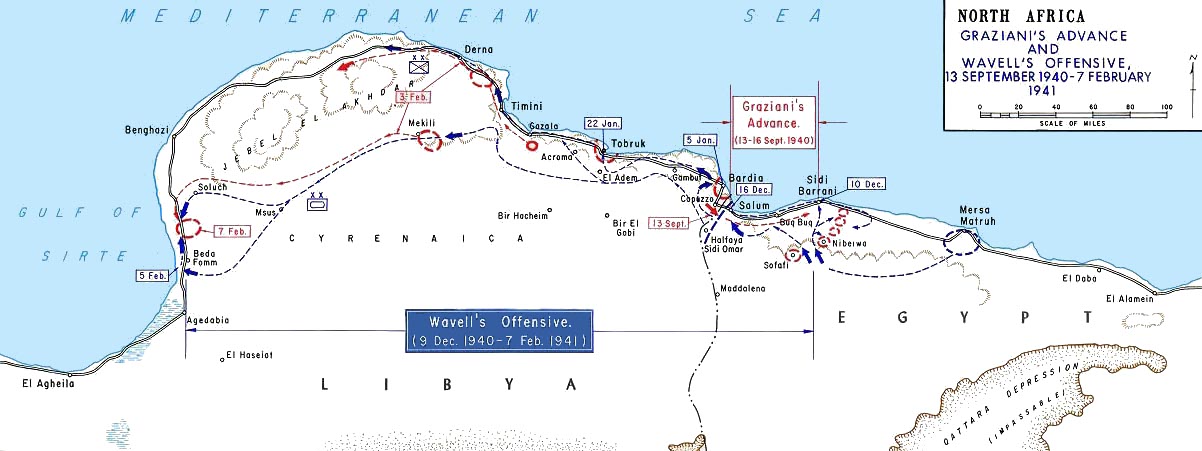

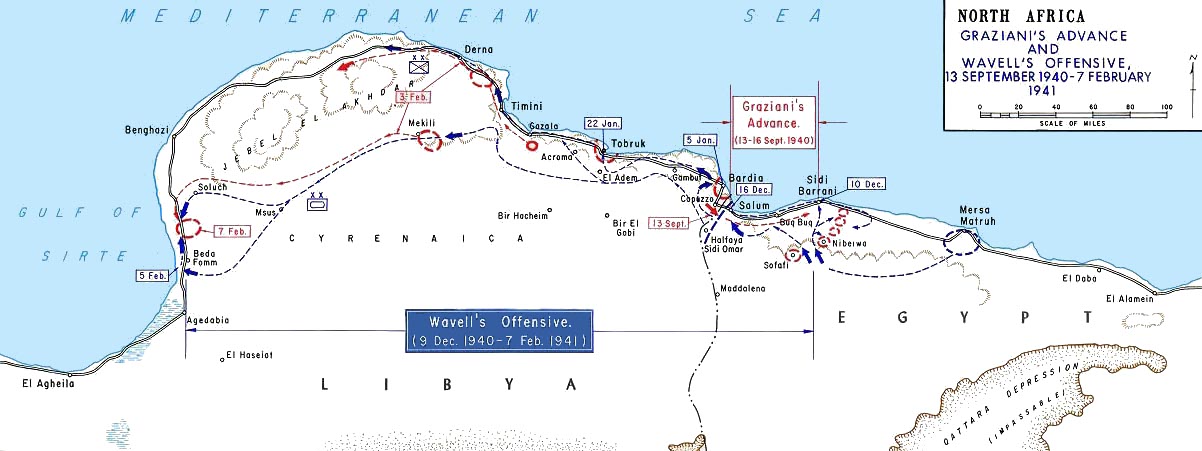

On 13 September, Graziani struck: his leading divisions advanced sixty miles into Egypt where they reached the town of Sidi Barrani

Sidi Barrani ( ) is a town in Egypt, near the Mediterranean Sea, about east of the Egypt–Libya border, and around from Tobruk, Libya.

Named after Sidi es-Saadi el Barrani, a Senussi sheikh who was a head of its Zawiya, the village ...

and, short of supplies, began to dig in. O'Connor then began to prepare for a counterattack. He had the 7th Armoured Division and the Indian 4th Infantry Division along with two brigades. British and Commonwealth troops in Egypt totalled around 36,000 men. The Italians had nearly five times as many troops along with hundreds more tanks and artillery pieces and the support of a much larger air force, albeit most of the Italian tank force comprised obsolete tankette

A tankette is a tracked armoured fighting vehicle that resembles a small tank, roughly the size of a car. It is mainly intended for light infantry support and scouting.

s. Meanwhile, small raiding columns were sent out from the 7th Armoured and newly formed Long Range Desert Group

The Long Range Desert Group (LRDG) was a reconnaissance and raiding unit of the British Army during the Second World War.

Originally called the Long Range Patrol (LRP), the unit was founded in Egypt in June 1940 by Major Ralph Alger Bagnold, ...

to probe, harass, and disrupt the Italians (this marked the start of what became the Special Air Service

The Special Air Service (SAS) is a special forces unit of the British Army. It was founded as a regiment in 1941 by David Stirling, and in 1950 it was reconstituted as a corps. The unit specialises in a number of roles including counter-terr ...

). The Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

and Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the Air force, air and space force of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It was formed towards the end of the World War I, First World War on 1 April 1918, on the merger of t ...

supported by bombarding enemy strongpoints, airfields and rear areas.Keegan (2005), p. 189

During November, O'Connor was appointed an acting lieutenant-general in recognition of the increased size of his command.

The counteroffensive,

During November, O'Connor was appointed an acting lieutenant-general in recognition of the increased size of his command.

The counteroffensive, Operation Compass

Operation Compass (also ) was the first large British military operation of the Western Desert Campaign (1940–1943) during the Second World War. British metropolitan, Imperial and Commonwealth forces attacked the Italian and Libyan forces of ...

, began on 8 December 1940. O'Connor's relatively small force of 31,000 men, 275 tanks and 120 artillery pieces, ably supported by an RAF wing and the Royal Navy, broke through a gap in the Italian defences at Sidi Barrani near the coast. The Desert Force cut a swath through the Italian rear areas, stitching its way between the desert and the coast, capturing strongpoint after strongpoint by cutting off and isolating them. The Italian guns proved to be no match for the heavy British Matilda tanks and their shells bounced off the armour. By mid-December the Italians had been pushed completely out of Egypt, leaving behind 38,000 prisoners and large stores of equipment.

The Desert Force paused to rest briefly before continuing the assault into Italian Libya against the remainder of Graziani's disorganised army. At that point, the Commander-in-Chief Middle East General Sir Archibald Wavell ordered the 4th Indian Division withdrawn to spearhead the invasion of Italian East Africa

Italian East Africa (, A.O.I.) was a short-lived colonial possession of Fascist Italy from 1936 to 1941 in the Horn of Africa. It was established following the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, which led to the military occupation of the Ethiopian ...

.Keegan (2005), p. 191 This veteran division was to be replaced by the inexperienced 6th Australian Division, which, although tough, was untrained for desert warfare. Despite this setback, the offensive continued with minimal delay. By the end of December the Australians besieged and took Bardia

Bardia, also El Burdi or Bardiyah ( or ) is a Mediterranean seaport in the Butnan District of eastern Libya, located near the border with Egypt. It is also occasionally called ''Bórdi Slemán''.

The name Bardia is deeply rooted in the ancient ...

along with 40,000 more prisoners and 400 guns.

In early January 1941, the Western Desert Force was redesignated XIII Corps. On 9 January, the offensive resumed. By 12 January the strategic fortress port of

In early January 1941, the Western Desert Force was redesignated XIII Corps. On 9 January, the offensive resumed. By 12 January the strategic fortress port of Tobruk

Tobruk ( ; ; ) is a port city on Libya's eastern Mediterranean coast, near the border with Egypt. It is the capital of the Butnan District (formerly Tobruk District) and has a population of 120,000 (2011 est.)."Tobruk" (history), ''Encyclop� ...

was surrounded. On 22 January it fell and another 27,000 Italian POW

POW is "prisoner of war", a person, whether civilian or combatant, who is held in custody by an enemy power during or immediately after an armed conflict.

POW or pow may also refer to:

Music

* P.O.W (Bullet for My Valentine song), "P.O.W" (Bull ...

s were taken along with valuable supplies, food, and weapons. As Tobruk fell it was decided to have XIII Corps answerable directly to Wavell at HQ Middle East Command, removing HQ British troops Egypt from the chain of command. On 26 January the remaining Italian divisions in eastern Libya began to retreat to the northwest along the coast. O'Connor promptly moved to pursue and cut them off, sending his armour southwest through the desert in a wide flanking movement, while the infantry gave chase along the coast to the north. The lightly armoured advance units of 4th Armoured Brigade arrived at Beda Fomm before the fleeing Italians on 5 February, blocking the main coast road and their route of escape. Two days later, after a costly and failed attempt to break through the blockade, and with the main British infantry force fast bearing down on them from Benghazi

Benghazi () () is the List of cities in Libya, second-most-populous city in Libya as well as the largest city in Cyrenaica, with an estimated population of 859,000 in 2023. Located on the Gulf of Sidra in the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean, Ben ...

to the north, the demoralised, exhausted Italians unconditionally capitulated. O'Connor and Eric Dorman-Smith cabled back to Wavell, "Fox killed in the open..."

In two months, the XIII Corps/Western Desert Force had advanced over , destroyed an entire Italian army of ten divisions, taken over 130,000 prisoners, 400 tanks and 1,292 guns at the cost of 500 killed and 1,373 wounded. In recognition of this, O'Connor was made a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by King George I of Great Britain, George I on 18 May 1725. Recipients of the Order are usually senior British Armed Forces, military officers or senior Civil Service ...

.

Reversal and capture

In a strategic sense, however, the victory of Operation Compass was not yet complete; the Italians still controlled most of Libya and possessed forces which would have to be dealt with. The Axis foothold inNorth Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

would remain a potential threat to Egypt and the Suez Canal so long as this situation continued. O'Connor was aware of this and urged Wavell to allow him to push on to Tripoli with all due haste to finish off the Italians. Wavell concurred as did Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Maitland Wilson, now the military governor of Cyrenaica

Cyrenaica ( ) or Kyrenaika (, , after the city of Cyrene), is the eastern region of Libya. Cyrenaica includes all of the eastern part of Libya between the 16th and 25th meridians east, including the Kufra District. The coastal region, als ...

, and XIII Corps resumed its advance. However, O'Connor's new offensive would prove short-lived: when the corps reached El Agheila, just to the southwest of Beda Fomm, Churchill ordered the advance to halt there. The Axis had invaded Greece and Wavell was ordered to send all available forces there as soon as possible to oppose this. Wavell took the 6th Australian Division, along with part of 7th Armoured Division and most of the supplies and air support for this ultimately doomed operation. XIII Corps HQ was wound down and in February 1941 O'Connor was appointed General Officer Commanding-in-Chief the British Troops in Egypt

British Troops in Egypt was a command of the British Army.

History

A British Army commander was appointed in the late 19th century after the Anglo-Egyptian War in 1882. The British Army remained in Egypt throughout the First World War and, after t ...

.

Matters were soon to become much worse for the British. By March 1941, Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

had dispatched General Erwin Rommel

Johannes Erwin Eugen Rommel (; 15 November 1891 – 14 October 1944), popularly known as The Desert Fox (, ), was a German '' Generalfeldmarschall'' (field marshal) during World War II. He served in the ''Wehrmacht'' (armed forces) of ...

along with the Afrika Korps

The German Africa Corps (, ; DAK), commonly known as Afrika Korps, was the German expeditionary force in Africa during the North African campaign of World War II. First sent as a holding force to shore up the Italian defense of its Africa ...

to bolster the Italians in Libya. Wavell and O'Connor now faced a formidable foe under a commander whose cunning, resourcefulness, and daring would earn him the nickname "the Desert Fox". Rommel wasted little time in launching his own offensive on 31 March. The inexperienced 2nd Armoured Division was soundly defeated and on 2 April Wavell came forward to review matters with Lieutenant-General Sir Philip Neame, by now the commander of British and Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the 15th century. Originally a phrase (the common-wealth ...

troops in Cyrenaica (Wilson having left to command the Allied expeditionary force in Greece). O'Connor was called forward and arrived from Cairo the next day, but declined to assume Neame's command because of his lack of familiarity with the prevailing conditions. However, he agreed to stay to advise.

On 6 April O'Connor and Neame, while travelling to their headquarters which had been withdrawn from Maraua to Timimi, were captured by a German patrol near Martuba.

Captivity and escape

O'Connor spent the next two and a half years as aprisoner of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of war for a ...

, mainly at the Castello di Vincigliata near Florence

Florence ( ; ) is the capital city of the Italy, Italian region of Tuscany. It is also the most populated city in Tuscany, with 362,353 inhabitants, and 989,460 in Metropolitan City of Florence, its metropolitan province as of 2025.

Florence ...

, Italy. Here he and Neame were in the company of such figures as Major-General Sir Adrian Carton de Wiart and Air Vice Marshal Owen Tudor Boyd. Although the conditions of their imprisonment were not unpleasant, the officers soon formed an escape club and began planning a break-out. Their first attempt, a simple attempt to climb over the castle walls, resulted in a month's solitary confinement. The second attempt, by an escape tunnel built between October 1942 and March 1943, had some success, with two New Zealander brigadiers, James Hargest and Reginald Miles, reaching Switzerland. O'Connor and Carton de Wiart, travelling on foot, were at large for a week but were captured near Bologna

Bologna ( , , ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in northern Italy. It is the List of cities in Italy, seventh most populous city in Italy, with about 400,000 inhabitants and 150 different nationalities. Its M ...

in the Po Valley. Once again, a month's solitary confinement was the result.

It was only after the Italian surrender in September 1943 that the final, successful, attempt was made. With help from the Italian resistance movement

The Italian Resistance ( ), or simply ''La'' , consisted of all the Italian resistance groups who fought the occupying forces of Nazi Germany and the fascist collaborationists of the Italian Social Republic during the Second World War in Italy ...

, Boyd, O'Connor and Neame escaped while being transferred from Vincigliati. After a failed rendezvous with a submarine

A submarine (often shortened to sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. (It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability.) The term "submarine" is also sometimes used historically or infor ...

, they arrived by boat at Termoli

Termoli ( Molisano: ''Térmëlë'') is a ''comune'' (municipality) on the south Adriatic coast of Italy, in the province of Campobasso, region of Molise. It has a population of around 32,000, having expanded quickly after World War II, and it is a ...

, then went on to Bari

Bari ( ; ; ; ) is the capital city of the Metropolitan City of Bari and of the Apulia Regions of Italy, region, on the Adriatic Sea in southern Italy. It is the first most important economic centre of mainland Southern Italy. It is a port and ...

where they were welcomed as guests by General Sir Harold Alexander, commanding the Allied Armies in Italy (AAI), then fighting on the Italian Front, along with the American General Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

, on 21 December 1943. Upon his return to Britain, O'Connor was presented with the knighthood he had been awarded in 1941 and promoted to lieutenant-general. Montgomery suggested that O'Connor be his successor as British Eighth Army

The Eighth Army was a field army of the British Army during the Second World War. It was formed as the Western Army on 10 September 1941, in Egypt, before being renamed the Army of the Nile and then the Eighth Army on 26 September. It was cr ...

commander, but that post was instead given to Oliver Leese and O'Connor was given a corps to command.

VIII Corps and Normandy

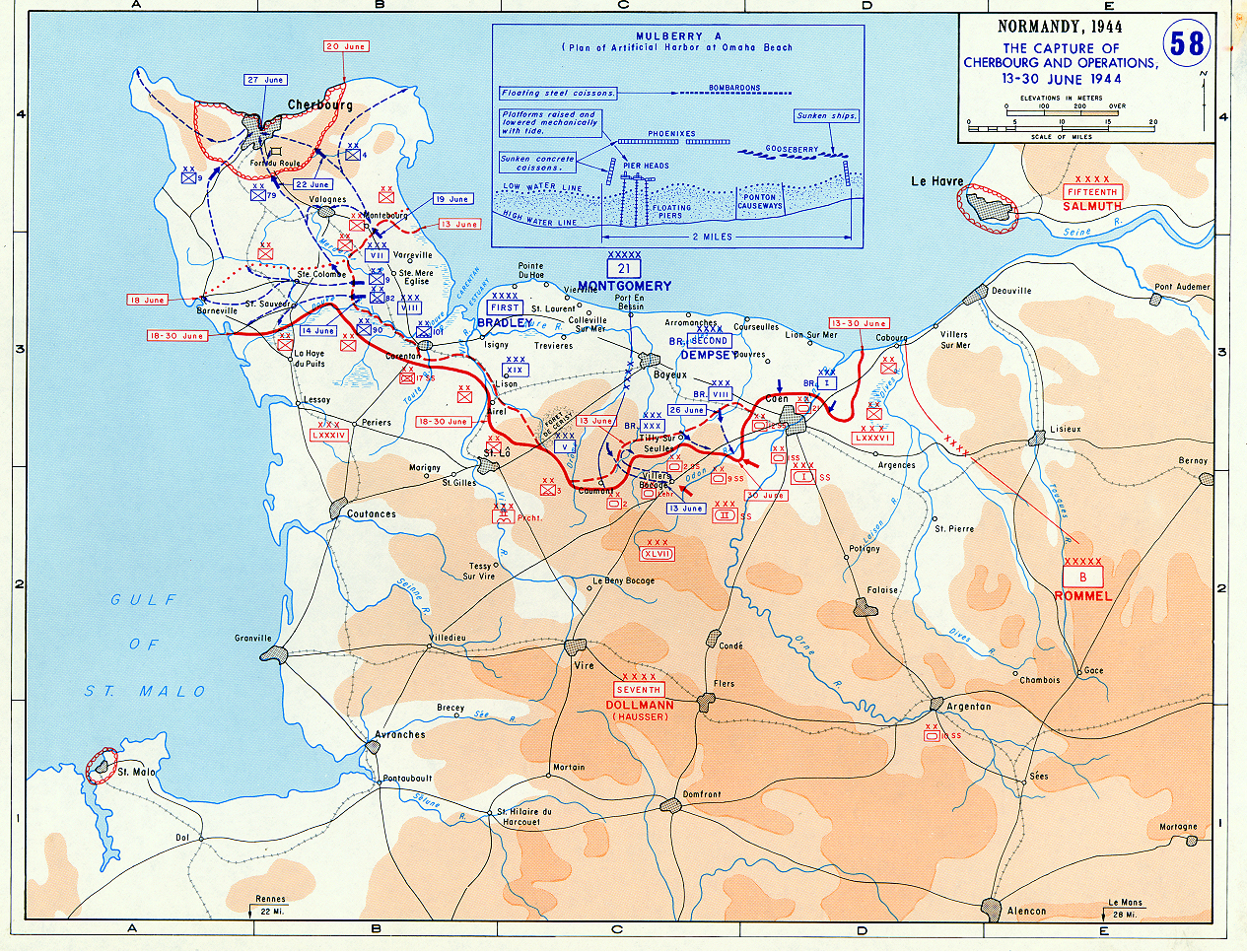

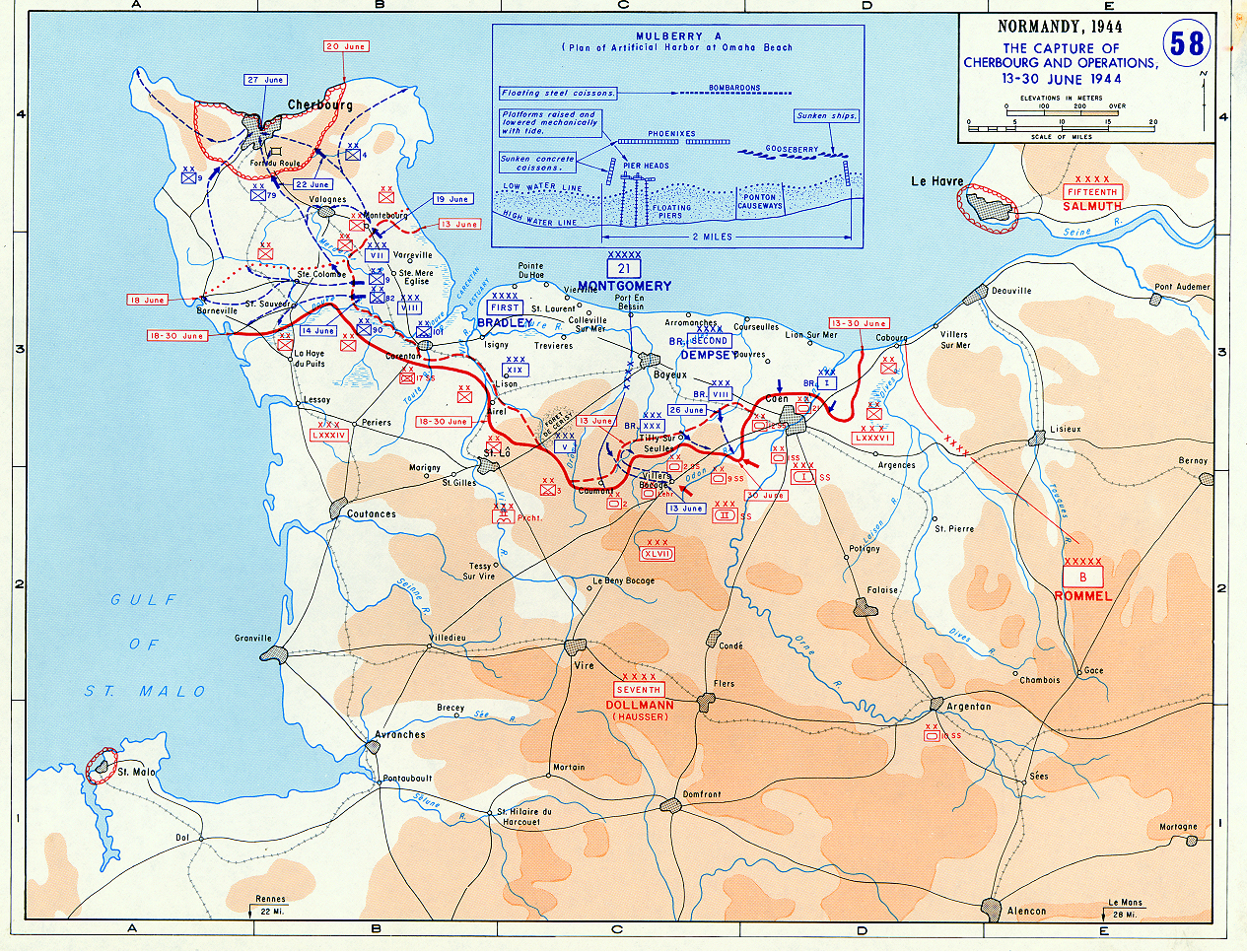

On 21 January 1944 O'Connor became commander of VIII Corps, which consisted of the Guards Armoured Division, 11th Armoured Division, 15th (Scottish) Infantry Division, along with 6th Guards Tank Brigade, 8th Army Group Royal Artillery and 2nd Household Cavalry Regiment. The corps formed part of the

On 21 January 1944 O'Connor became commander of VIII Corps, which consisted of the Guards Armoured Division, 11th Armoured Division, 15th (Scottish) Infantry Division, along with 6th Guards Tank Brigade, 8th Army Group Royal Artillery and 2nd Household Cavalry Regiment. The corps formed part of the British Second Army

The British Second Army was a Field Army active during the World War I, First and World War II, Second World Wars. During the First World War the army was active on the Western Front (World War I), Western Front throughout most of the war and later ...

, commanded by Lieutenant-General Miles Dempsey, which itself was part of the Anglo-Canadian 21st Army Group

The 21st Army Group was a British headquarters formation formed during the Second World War. It controlled two field armies and other supporting units, consisting primarily of the British Second Army and the First Canadian Army. Established ...

, commanded by General Sir Bernard Montgomery, a friend who had also been a fellow instructor at the Staff College, Camberley in the 1920s, in addition to having served together in Palestine some years before. O'Connor's new command was to take part in Operation Overlord

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the Allies of World War II, Allied operation that launched the successful liberation of German-occupied Western Front (World War II), Western Europe during World War II. The ope ...

, the Allied invasion of German-occupied France

The Military Administration in France (; ) was an interim occupation authority established by Nazi Germany during World War II to administer the occupied zone in areas of northern and western France. This so-called ' was established in June 19 ...

, although it was not scheduled for the initial landings as it was to form part of the second wave to go ashore.

On 11 June 1944, five days after the initial landings in Normandy, O'Connor and the leading elements of VIII Corps arrived in Normandy in the sector around Caen

Caen (; ; ) is a Communes of France, commune inland from the northwestern coast of France. It is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Calvados (department), Calvados. The city proper has 105,512 inha ...

, which would be the scene of much hard fighting during the next few weeks. O'Connor's first mission (with the 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division

The 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division was an infantry Division (military), division of Britain's Territorial Army (United Kingdom), Territorial Army (TA). The division was first formed in 1908, as the Wessex Division. During the World War I, First ...

under command, replacing the Guards Armoured Division) was to mount Operation Epsom

Operation Epsom, also known as the First Battle of the Odon, was a British offensive in the Second World War between 26 and 30 June 1944, during the Operation Overlord, Battle of Normandy. The offensive was intended to outflank and seize the ...

, a break out from the bridgehead established by the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division

The 3rd Canadian Division is a formation of the Canadian Army responsible for the command and mobilization of all army units in the provinces of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta and British Columbia, as well as Northwestern Ontario including the ...

, cross the Odon and Orne

Orne (; or ) is a département in the northwest of France, named after the river Orne. It had a population of 279,942 in 2019.Bretteville-sur-Laize and cut Caen off from the south. The break-out and river crossings were accomplished promptly. The army group commander, Montgomery, congratulated O'Connor and his VIII Corps on their success. But cutting off Caen would prove much harder. VIII Corps was pushed back over the Orne. O'Connor tried to re-establish a bridgehead during Operation Jupiter with the 43rd (Wessex) Division, but met with little success. Although the operation had failed to achieve its tactical objectives, Montgomery was pleased with the strategic benefits in the commitment and fixing of the German armoured reserves to the Caen sector.

After being withdrawn into reserve on 12 July, the next major action for VIII Corps would be Operation Goodwood, for which the corps was stripped of its infantry divisions but had a third armoured division ( 7th Armoured Division) attached. The attack began on 18 July with a massive aerial bombardment by the 9th USAAF, and ended on 20 July with a three-pronged drive to capture Bras and Hubert-Folie on the right, Fontenay on the left, and Bourguébus Ridge in the centre. However, the attack ground to a halt in pouring rain, turning the battlefield into a quagmire, with the major objectives still not taken, notably the Bourguebus Ridge which was the key to any break-out.

Restored to its pre-invasion formation but with

A swift drive was followed by fierce fighting to the south during the first two days of the advance, with both sides taking heavy losses. As the allies prepared to pursue the Germans from France, O'Connor learned that VIII Corps would not take part in this phase of the campaign. VIII Corps was placed in reserve, and its transport used to supply XXX Corps and XII Corps. His command was reduced in mid-August, with the transfer of the Guards Armoured Divisions and 11th Armoured Division to XXX Corps and 15th (Scottish) Division to XII Corps. While in reserve, O'Connor maintained an active correspondence with Montgomery,

(O'Connor, 5/3/41- 5/3/44 Aug 24, 26 1944)

O'Connor remained in command of VIII Corps, for the time being, and was given the task of supporting Lieutenant-General Brian Horrocks' XXX Corps in Operation Market Garden, the plan by Montgomery to establish a bridgehead across the

O'Connor remained in command of VIII Corps, for the time being, and was given the task of supporting Lieutenant-General Brian Horrocks' XXX Corps in Operation Market Garden, the plan by Montgomery to establish a bridgehead across the

Richard O’Connor Desert War.netImperial War Museum Interview

* , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:OConnor, Richard 1889 births 1981 deaths Graduates of the Royal College of Defence Studies British Army generals of World War II British Army personnel of World War I British escapees British military personnel of the 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine British people of Irish descent British World War II prisoners of war Cameronians officers Commanders of the Legion of Honour Companions of the Distinguished Service Order Escapees from Italian detention Graduates of the Royal Military College, Sandhurst Graduates of the Staff College, Camberley Honourable Artillery Company officers Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath Knights of the Thistle Lords High Commissioner to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland Lord-lieutenants of Ross and Cromarty People educated at Wellington College, Berkshire People from Srinagar Recipients of the Croix de Guerre (France) Recipients of the Military Cross Recipients of the Silver Medal of Military Valor World War II prisoners of war held by Italy Academics of the Royal Military College, Sandhurst Academics of the Staff College, Camberley

British 3rd Infantry Division

The 3rd (United Kingdom) Division, also known as The Iron Division, is a regular army division of the British Army. It was created in 1809 by Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, as part of the Anglo-Portuguese Army, for service in the P ...

attached, the corps was switched to the southwest of Caen to take part in Operation Bluecoat. 15th (Scottish) Division attacked towards Vire to the east and west of Bois du Homme in order to facilitate the American advance in Operation Cobra

Operation Cobra was an offensive launched by the First United States Army under Lieutenant General Omar Bradley seven weeks after the D-Day landings, during the Normandy campaign of World War II. The intention was to take advantage of the dis ...

br>(O'Connor, 5/3/25 July 29 1944)A swift drive was followed by fierce fighting to the south during the first two days of the advance, with both sides taking heavy losses. As the allies prepared to pursue the Germans from France, O'Connor learned that VIII Corps would not take part in this phase of the campaign. VIII Corps was placed in reserve, and its transport used to supply XXX Corps and XII Corps. His command was reduced in mid-August, with the transfer of the Guards Armoured Divisions and 11th Armoured Division to XXX Corps and 15th (Scottish) Division to XII Corps. While in reserve, O'Connor maintained an active correspondence with Montgomery,

Hobart

Hobart ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the island state of Tasmania, Australia. Located in Tasmania's south-east on the estuary of the River Derwent, it is the southernmost capital city in Australia. Despite containing nearly hal ...

and others, making suggestions for improvements of armoured vehicles and addressing various other problems such as combat fatigue

Combat stress reaction (CSR) is acute behavioral disorganization as a direct result of the trauma of war. Also known as "combat fatigue", "battle fatigue", "operational exhaustion", or "battle/war neurosis", it has some overlap with the diagnosis ...

. Some of his recommendations were followed up; such as for mounting "rams

In engineering, reliability, availability, maintainability and safety (RAMS)hedgerow

A hedge or hedgerow is a line of closely spaced (3 feet or closer) shrubs and sometimes trees, planted and trained to form a barrier or to mark the boundary of an area, such as between neighbouring properties. Hedges that are used to separate ...

countr(O'Connor, 5/3/41- 5/3/44 Aug 24, 26 1944)

Operation Market Garden and India

O'Connor remained in command of VIII Corps, for the time being, and was given the task of supporting Lieutenant-General Brian Horrocks' XXX Corps in Operation Market Garden, the plan by Montgomery to establish a bridgehead across the

O'Connor remained in command of VIII Corps, for the time being, and was given the task of supporting Lieutenant-General Brian Horrocks' XXX Corps in Operation Market Garden, the plan by Montgomery to establish a bridgehead across the Rhine

The Rhine ( ) is one of the List of rivers of Europe, major rivers in Europe. The river begins in the Swiss canton of Graubünden in the southeastern Swiss Alps. It forms part of the Swiss-Liechtenstein border, then part of the Austria–Swit ...

in the Netherlands. Following their entry into Weert

Weert (; ) is a Municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality and city in the southeastern Netherlands located in the western part of the Provinces of the Netherlands, province of Limburg (Netherlands), Limburg. It lies on the Eindhoven–Maas ...

at the end of September, VIII Corps prepared for and took part in Operation Aintree, the advance towards Venray

Venray or Venraij (; ) is a Municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality and a city in Limburg (Netherlands), Limburg, the Netherlands.

The municipality of Venray consists of 14 towns over an area of , with 43,494 inhabitants as of July 2016 ...

and Venlo

Venlo () is a List of cities in the Netherlands by province, city and List of municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality in southeastern Netherlands, close to the border with Germany. It is situated in the province of Limburg (Netherlands), ...

beginning on 12 October.

However, on 27 November O'Connor was removed from his post and was ordered to take over from Lieutenant-General Sir Mosley Mayne as GOC-in-C, Eastern Command, India. Smart's account says that Montgomery prompted the move for, "not being ruthless enough with his American subordinates", although Mead states that the initiative was taken by Field Marshal Sir Alan Brooke, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff

Chief of the General Staff (CGS) has been the title of the professional head of the British Army since 1964. The CGS is a member of both the Chiefs of Staff Committee and the Army Board; he is also the Chair of the Executive Committee of the A ...

(CIGS), but Montgomery made no attempt to retain O'Connor. He was succeeded as GOC VIII Corps by Major-General Evelyn Barker

General (United Kingdom), General Sir Evelyn Hugh Barker, (22 May 1894 – 23 November 1983) was a British Army officer who saw service in both the First World War and the Second World War. During the latter, he commanded the 10th Infantry Br ...

, a much younger man and formerly the GOC of the 49th (West Riding) Infantry Division who had been one of O'Connor's students at the Staff College at Camberley in the late 1920s. This marked the end of a long and distinguished combat career, although the new job was an important one, controlling the lines of communication of the Fourteenth Army. O'Connor was mentioned in despatches for the thirteenth and final time of his career on 22 March 1945.

Having been promoted to full general in April 1945, O'Connor was appointed GOC-in-C North Western Army in India in October that year (the formation was renamed Northern Command in November of that year). By now the war was over.

Post-war

From 1946 to 1947 he wasAdjutant-General to the Forces

The Adjutant-General to the Forces, commonly just referred to as the Adjutant-General (AG), was for just over 250 years one of the most senior officers in the British Army. The AG was latterly responsible for developing the Army's personnel polic ...

and aide-de-camp general to the King. His career as adjutant general was to be short-lived, however. After a disagreement over a cancelled demobilisation

Demobilization or demobilisation (see spelling differences) is the process of standing down a nation's armed forces from combat-ready status. This may be as a result of victory in war, or because a crisis has been peacefully resolved and milita ...

for troops stationed in the Far East, O'Connor offered his resignation in September 1947, which was accepted. Montgomery, by then the CIGS in succession to Brooke, maintained that he had been sacked, rather than resigned, for being, "not up to the job." Not long after this he was installed as a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by King George I on 18 May 1725. Recipients of the Order are usually senior military officers or senior civil servants, and the monarch awards it on the advice of His ...

.

Retirement and final years

O'Connor retired in 1948 at the age of fifty-eight. However, he maintained his links with the army and took on other responsibilities. He was Commandant of theArmy Cadet Force

The Army Cadet Force (ACF), generally shortened to Army Cadets, is a national Youth organisations in the United Kingdom, youth organisation sponsored by the United Kingdom's Ministry of Defence (United Kingdom), Ministry of Defence and the Bri ...

in Scotland from 1948 to 1959; Colonel

Colonel ( ; abbreviated as Col., Col, or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a colon ...

of the Cameronians, 1951 to 1954; Lord lieutenant

A lord-lieutenant ( ) is the British monarch's personal representative in each lieutenancy area of the United Kingdom. Historically, each lieutenant was responsible for organising the county's militia. In 1871, the lieutenant's responsibility ov ...

of Ross and Cromarty

Ross and Cromarty (), is an area in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland. In modern usage, it is a registration county and a Lieutenancy areas of Scotland, lieutenancy area. Between 1889 and 1975 it was a Shires of Scotland, county.

Historical ...

from 1955 to 1964 and served as Lord High Commissioner to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland

The Lord High Commissioner to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland is the monarch's personal representative to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland (the Kirk), reflecting the Church's role as the national church of Scotla ...

in 1964. His first wife, Jean, died in 1959, and in 1963 he married Dorothy Russell.

In July 1971, he was created Knight of the Order of the Thistle. O’Connor was interviewed concerning North African operations in episode 8, "The Desert: North Africa (1940–1943)”, of the acclaimed British documentary television series, ''The World at War

''The World at War'' is a 26-episode British documentary television series that chronicles the events of the Second World War. Produced in 1973 at a cost of around £880,000 (), it was the most expensive factual series ever made at the time. ...

.'' O'Connor died in London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

on 17 June 1981, just two months shy of his 92nd birthday. There was a small funeral, attended only by his family. There were also two memorial services, one held in London on 15 July, with O'Connor's great friend and admirer, Field Marshal Lord Harding, as he was now known, giving the address, where he stated the following:

The second memorial service was held in Edinburgh on 11 August, where Lieutenant General Sir George Collingwood, who had been O'Connor's aide-de-camp in the late 1930s, made the address. Making references to O'Connor's campaign in the desert some forty years earlier, he then mentioned his numerous attempts to escape from captivity, along with his happy private life and his two "wonderful partners in the home", before ending his address with:

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * *External links

* *Richard O’Connor Desert War.net

* , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:OConnor, Richard 1889 births 1981 deaths Graduates of the Royal College of Defence Studies British Army generals of World War II British Army personnel of World War I British escapees British military personnel of the 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine British people of Irish descent British World War II prisoners of war Cameronians officers Commanders of the Legion of Honour Companions of the Distinguished Service Order Escapees from Italian detention Graduates of the Royal Military College, Sandhurst Graduates of the Staff College, Camberley Honourable Artillery Company officers Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath Knights of the Thistle Lords High Commissioner to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland Lord-lieutenants of Ross and Cromarty People educated at Wellington College, Berkshire People from Srinagar Recipients of the Croix de Guerre (France) Recipients of the Military Cross Recipients of the Silver Medal of Military Valor World War II prisoners of war held by Italy Academics of the Royal Military College, Sandhurst Academics of the Staff College, Camberley