Reptiles, as commonly defined, are a group of

tetrapod

A tetrapod (; from Ancient Greek :wiktionary:τετρα-#Ancient Greek, τετρα- ''(tetra-)'' 'four' and :wiktionary:πούς#Ancient Greek, πούς ''(poús)'' 'foot') is any four-Limb (anatomy), limbed vertebrate animal of the clade Tetr ...

s with an

ectotherm

An ectotherm (), more commonly referred to as a "cold-blooded animal", is an animal in which internal physiological sources of heat, such as blood, are of relatively small or of quite negligible importance in controlling body temperature.Dav ...

ic metabolism and

amniotic development. Living traditional reptiles comprise four

orders

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* A socio-political or established or existing order, e.g. World order, Ancien Regime, Pax Britannica

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

* H ...

:

Testudines

Turtles are reptiles of the order (biology), order Testudines, characterized by a special turtle shell, shell developed mainly from their ribs. Modern turtles are divided into two major groups, the Pleurodira (side necked turtles) and Crypt ...

,

Crocodilia

Crocodilia () is an order of semiaquatic, predatory reptiles that are known as crocodilians. They first appeared during the Late Cretaceous and are the closest living relatives of birds. Crocodilians are a type of crocodylomorph pseudosuchia ...

,

Squamata

Squamata (, Latin ''squamatus'', 'scaly, having scales') is the largest Order (biology), order of reptiles; most members of which are commonly known as Lizard, lizards, with the group also including Snake, snakes. With over 11,991 species, it i ...

, and

Rhynchocephalia

Rhynchocephalia (; ) is an order of lizard-like reptiles that includes only one living species, the tuatara (''Sphenodon punctatus'') of New Zealand. Despite its current lack of diversity, during the Mesozoic rhynchocephalians were a speciose g ...

. About 12,000 living species of reptiles are listed in the

Reptile Database

The Reptile Database is a scientific database that collects taxonomic information on all living reptile species (i.e. no fossil species such as dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared ...

. The study of the traditional reptile orders, customarily in combination with the study of modern

amphibian

Amphibians are ectothermic, anamniote, anamniotic, tetrapod, four-limbed vertebrate animals that constitute the class (biology), class Amphibia. In its broadest sense, it is a paraphyletic group encompassing all Tetrapod, tetrapods, but excl ...

s, is called

herpetology

Herpetology (from Ancient Greek ἑρπετόν ''herpetón'', meaning "reptile" or "creeping animal") is a branch of zoology concerned with the study of amphibians (including frogs, salamanders, and caecilians (Gymnophiona)) and reptiles (in ...

.

Reptiles have been subject to several conflicting

taxonomic

280px, Generalized scheme of taxonomy

Taxonomy is a practice and science concerned with classification or categorization. Typically, there are two parts to it: the development of an underlying scheme of classes (a taxonomy) and the allocation ...

definitions.

In

Linnaean taxonomy

Linnaean taxonomy can mean either of two related concepts:

# The particular form of biological classification (taxonomy) set up by Carl Linnaeus, as set forth in his ''Systema Naturae'' (1735) and subsequent works. In the taxonomy of Linnaeus th ...

, reptiles are gathered together under the

class

Class, Classes, or The Class may refer to:

Common uses not otherwise categorized

* Class (biology), a taxonomic rank

* Class (knowledge representation), a collection of individuals or objects

* Class (philosophy), an analytical concept used d ...

Reptilia ( ), which corresponds to common usage. Modern

cladistic taxonomy

Cladistics ( ; from Ancient Greek 'branch') is an approach to biological classification in which organisms are categorized in groups ("clades") based on hypotheses of most recent common ancestry. The evidence for hypothesized relationships is ...

regards that group as

paraphyletic

Paraphyly is a taxonomic term describing a grouping that consists of the grouping's last common ancestor and some but not all of its descendant lineages. The grouping is said to be paraphyletic ''with respect to'' the excluded subgroups. In co ...

, since

genetic and

paleontological

Paleontology, also spelled as palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of the life of the past, mainly but not exclusively through the study of fossils. Paleontologists use fossils as a means to classify organisms, measure geolo ...

evidence has determined that

bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class (biology), class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the Oviparity, laying of Eggshell, hard-shelled eggs, a high Metabolism, metabolic rate, a fou ...

s (class Aves), as members of

Dinosauria, are more closely related to living

crocodilian

Crocodilia () is an Order (biology), order of semiaquatic, predatory reptiles that are known as crocodilians. They first appeared during the Late Cretaceous and are the closest living relatives of birds. Crocodilians are a type of crocodylomorp ...

s than to other reptiles, and are thus nested among reptiles from an evolutionary perspective. Many cladistic systems therefore redefine Reptilia as a

clade

In biology, a clade (), also known as a Monophyly, monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that is composed of a common ancestor and all of its descendants. Clades are the fundamental unit of cladistics, a modern approach t ...

(

monophyletic

In biological cladistics for the classification of organisms, monophyly is the condition of a taxonomic grouping being a clade – that is, a grouping of organisms which meets these criteria:

# the grouping contains its own most recent co ...

group) including birds, though the precise definition of this clade varies between authors.

Others prioritize the clade

Sauropsida

Sauropsida (Greek language, Greek for "lizard faces") is a clade of amniotes, broadly equivalent to the Class (biology), class Reptile, Reptilia, though typically used in a broader sense to also include extinct stem-group relatives of modern repti ...

, which typically refers to all

amniote

Amniotes are tetrapod vertebrate animals belonging to the clade Amniota, a large group that comprises the vast majority of living terrestrial animal, terrestrial and semiaquatic vertebrates. Amniotes evolution, evolved from amphibious Stem tet ...

s more closely related to modern reptiles than to

mammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

s.

The earliest known proto-reptiles originated from the

Carboniferous

The Carboniferous ( ) is a Geologic time scale, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), system of the Paleozoic era (geology), era that spans 60 million years, from the end of the Devonian Period Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the ...

period, having evolved from advanced

reptiliomorph

Reptiliomorpha (meaning reptile-shaped; in PhyloCode known as ''Pan-Amniota'') is a clade containing the amniotes and those tetrapods that share a more recent common ancestor with amniotes than with living amphibians (lissamphibians). It was defi ...

tetrapods which became increasingly adapted to life on dry land. The earliest known

eureptile

Sauropsida (Greek for "lizard faces") is a clade of amniotes, broadly equivalent to the class Reptilia, though typically used in a broader sense to also include extinct stem-group relatives of modern reptiles and birds (which, as theropod dinosaur ...

("true reptile") was ''

Hylonomus

''Hylonomus'' (; ''hylo-'' "forest" + ''nomos'' "dweller") is an extinct genus of reptile that lived during the Bashkirian stage of the Late Carboniferous. It is the earliest known crown group amniote and the oldest known unquestionable reptile, ...

'', a small and superficially lizard-like animal which lived in

Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada, located on its east coast. It is one of the three Maritime Canada, Maritime provinces and Population of Canada by province and territory, most populous province in Atlan ...

during the

Bashkirian

The Bashkirian is in the International Commission on Stratigraphy geologic timescale the lowest stage (stratigraphy), stage or oldest age (geology), age of the Pennsylvanian (geology), Pennsylvanian. The Bashkirian age lasted from to Mega annu ...

age of the

Late Carboniferous

Late or LATE may refer to:

Everyday usage

* Tardy, or late, not being on time

* Late (or the late) may refer to a person who is dead

Music

* Late (The 77s album), ''Late'' (The 77s album), 2000

* Late (Alvin Batiste album), 1993

* Late!, a pseudo ...

, around .

[ Genetic and fossil data argues that the two largest lineages of reptiles, ]Archosauromorpha

Archosauromorpha ( Greek for "ruling lizard forms") is a clade of diapsid reptiles containing all reptiles more closely related to archosaurs (such as crocodilians and dinosaurs, including birds) than to lepidosaurs (such as tuataras, lizards, ...

(crocodilians, birds, and kin) and Lepidosauromorpha

Lepidosauromorpha (in PhyloCode known as Pan-Lepidosauria) is a group of reptiles comprising all diapsids closer to lizards than to archosaurs (which include crocodiles and birds). The only living sub-group is the Lepidosauria, which contains tw ...

(lizards, and kin), diverged during the Permian

The Permian ( ) is a geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system which spans 47 million years, from the end of the Carboniferous Period million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Triassic Period 251.902 Mya. It is the s ...

period. In addition to the living reptiles, there are many diverse groups that are now extinct

Extinction is the termination of an organism by the death of its Endling, last member. A taxon may become Functional extinction, functionally extinct before the death of its last member if it loses the capacity to Reproduction, reproduce and ...

, in some cases due to mass extinction events. In particular, the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event

The Cretaceous–Paleogene (K–Pg) extinction event, also known as the K–T extinction, was the extinction event, mass extinction of three-quarters of the plant and animal species on Earth approximately 66 million years ago. The event cau ...

wiped out the pterosaur

Pterosaurs are an extinct clade of flying reptiles in the order Pterosauria. They existed during most of the Mesozoic: from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous (228 million to 66 million years ago). Pterosaurs are the earli ...

s, plesiosaurs

The Plesiosauria or plesiosaurs are an Order (biology), order or clade of extinct Mesozoic marine reptiles, belonging to the Sauropterygia.

Plesiosaurs first appeared in the latest Triassic Period (geology), Period, possibly in the Rhaetian st ...

, and all non-avian dinosaurs

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic Geological period, period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the #Evolutio ...

alongside many species of crocodyliforms and squamates

Squamata (, Latin ''squamatus'', 'scaly, having scales') is the largest order of reptiles; most members of which are commonly known as lizards, with the group also including snakes. With over 11,991 species, it is also the second-largest order ...

(e.g., mosasaur

Mosasaurs (from Latin ''Mosa'' meaning the 'Meuse', and Ancient Greek, Greek ' meaning 'lizard') are an extinct group of large aquatic reptiles within the family Mosasauridae that lived during the Late Cretaceous. Their first fossil remains wer ...

s). Modern non-bird reptiles inhabit all the continents except Antarctica.

Reptiles are tetrapod vertebrates

Vertebrates () are animals with a vertebral column (backbone or spine), and a cranium, or skull. The vertebral column surrounds and protects the spinal cord, while the cranium protects the brain.

The vertebrates make up the subphylum Vertebra ...

, creatures that either have four limbs or, like snakes, are descended from four-limbed ancestors. Unlike amphibian

Amphibians are ectothermic, anamniote, anamniotic, tetrapod, four-limbed vertebrate animals that constitute the class (biology), class Amphibia. In its broadest sense, it is a paraphyletic group encompassing all Tetrapod, tetrapods, but excl ...

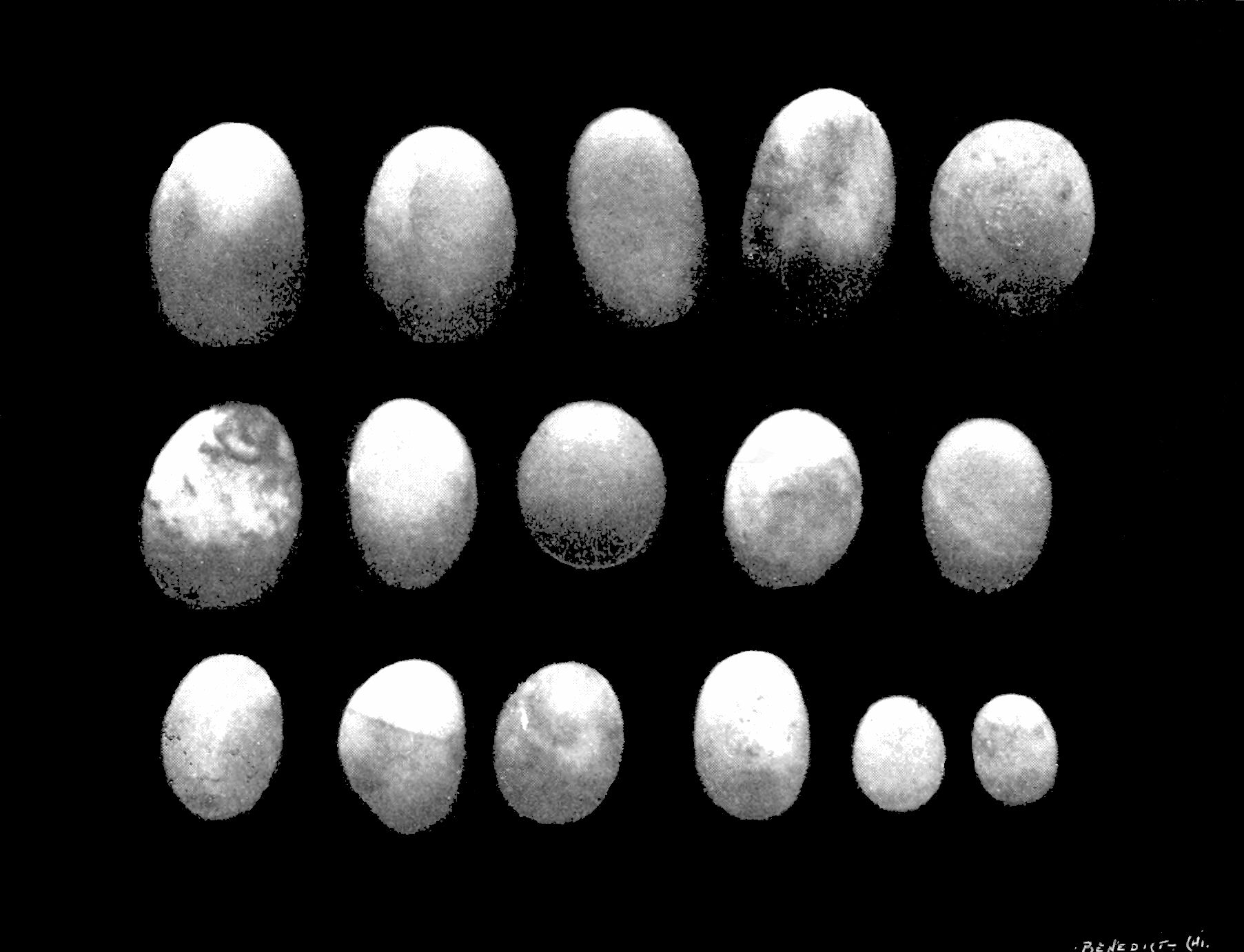

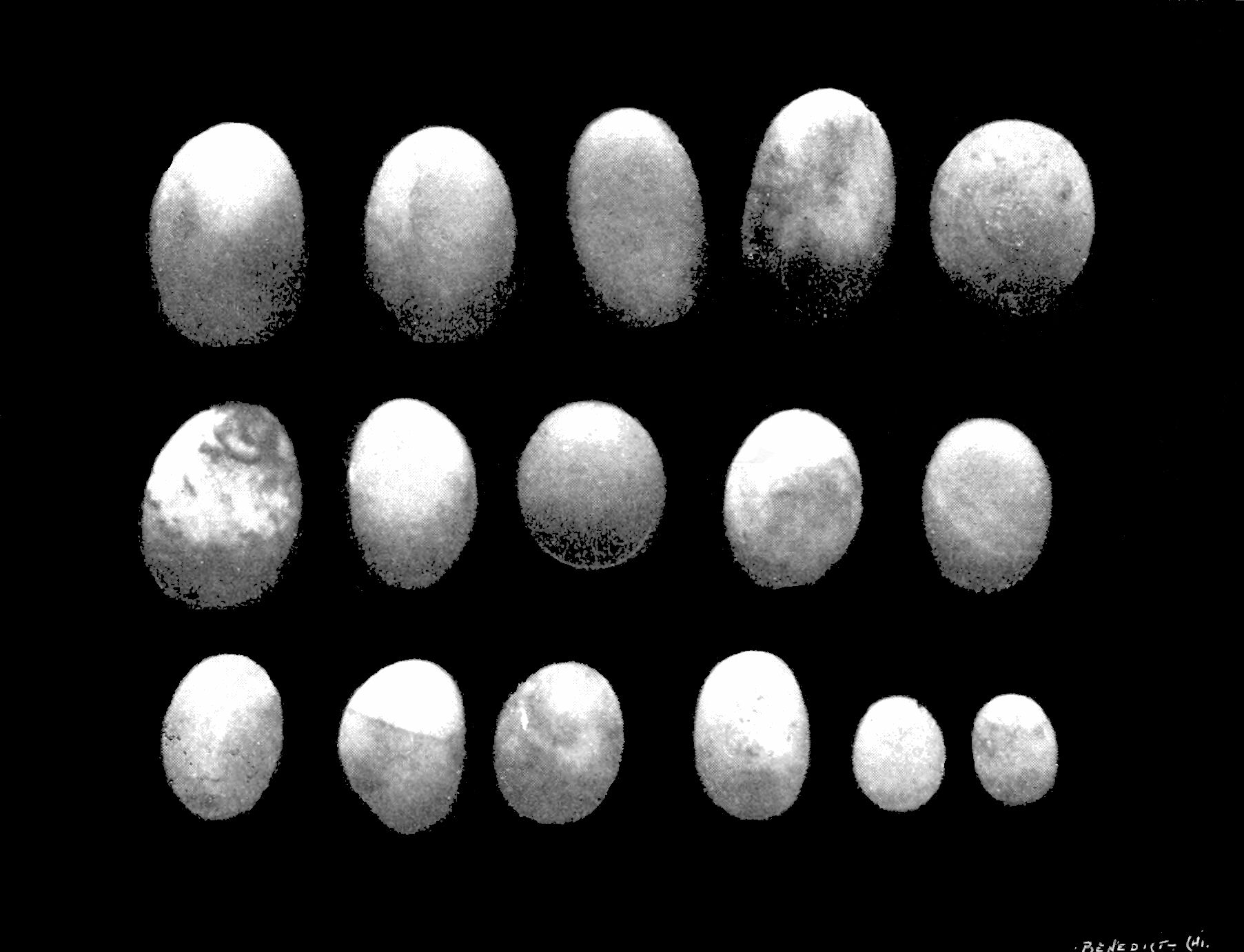

s, reptiles do not have an aquatic larval stage. Most reptiles are oviparous

Oviparous animals are animals that reproduce by depositing fertilized zygotes outside the body (i.e., by laying or spawning) in metabolically independent incubation organs known as eggs, which nurture the embryo into moving offsprings kno ...

, although several species of squamates are viviparous

In animals, viviparity is development of the embryo inside the body of the mother, with the maternal circulation providing for the metabolic needs of the embryo's development, until the mother gives birth to a fully or partially developed juve ...

, as were some extinct aquatic cladeseggshell

An eggshell is the outer covering of a hard-shelled egg (biology), egg and of some forms of eggs with soft outer coats.

Worm eggs

Nematode eggs present a two layered structure: an external vitellin layer made of chitin that confers mechanical ...

. As amniotes, reptile eggs are surrounded by membranes for protection and transport, which adapt them to reproduction on dry land. Many of the viviparous species feed their fetus

A fetus or foetus (; : fetuses, foetuses, rarely feti or foeti) is the unborn offspring of a viviparous animal that develops from an embryo. Following the embryonic development, embryonic stage, the fetal stage of development takes place. Pren ...

es through various forms of placenta analogous to those of mammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

s, with some providing initial care for their hatchlings. Extant

Extant or Least-concern species, least concern is the opposite of the word extinct. It may refer to:

* Extant hereditary titles

* Extant literature, surviving literature, such as ''Beowulf'', the oldest extant manuscript written in English

* Exta ...

reptiles range in size from a tiny gecko, ''Sphaerodactylus ariasae

''Sphaerodactylus ariasae'', commonly called the Jaragua sphaero or the Jaragua dwarf gecko, is the smallest species of lizard in the family Sphaerodactylidae.

Description

''Sphaerodactylus ariasae'' is the world's smallest known reptile. The ...

'', which can grow up to to the saltwater crocodile

The saltwater crocodile (''Crocodylus porosus'') is a crocodilian native to saltwater habitats, brackish wetlands and freshwater rivers from India's east coast across Southeast Asia and the Sundaland to northern Australia and Micronesia. It ha ...

, ''Crocodylus porosus'', which can reach over in length and weigh over .

Classification

Research history

In the 13th century, the category of ''reptile'' was recognized in Europe as consisting of a miscellany of egg-laying creatures, including "snakes, various fantastic monsters, lizards, assorted amphibians, and worms", as recorded by

In the 13th century, the category of ''reptile'' was recognized in Europe as consisting of a miscellany of egg-laying creatures, including "snakes, various fantastic monsters, lizards, assorted amphibians, and worms", as recorded by Beauvais

Beauvais ( , ; ) is a town and Communes of France, commune in northern France, and prefecture of the Oise Departments of France, département, in the Hauts-de-France Regions of France, region, north of Paris.

The Communes of France, commune o ...

in his ''Mirror of Nature''.

In the 18th century, the reptiles were, from the outset of classification, grouped with the amphibian

Amphibians are ectothermic, anamniote, anamniotic, tetrapod, four-limbed vertebrate animals that constitute the class (biology), class Amphibia. In its broadest sense, it is a paraphyletic group encompassing all Tetrapod, tetrapods, but excl ...

s. Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné,#Blunt, Blunt (2004), p. 171. was a Swedish biologist and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the modern system of naming o ...

, working from species-poor Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north, and Finland to the east. At , Sweden is the largest Nordic count ...

, where the common adder and grass snake

The grass snake (''Natrix natrix''), sometimes called the ringed snake or water snake, is a Eurasian semi-aquatic non- venomous colubrid snake. It is often found near water and feeds almost exclusively on amphibians.

Subspecies

Many subspecie ...

are often found hunting in water, included all reptiles and amphibians in class

Class, Classes, or The Class may refer to:

Common uses not otherwise categorized

* Class (biology), a taxonomic rank

* Class (knowledge representation), a collection of individuals or objects

* Class (philosophy), an analytical concept used d ...

in his '' Systema Naturæ''.herpetology

Herpetology (from Ancient Greek ἑρπετόν ''herpetón'', meaning "reptile" or "creeping animal") is a branch of zoology concerned with the study of amphibians (including frogs, salamanders, and caecilians (Gymnophiona)) and reptiles (in ...

.

It was not until the beginning of the 19th century that it became clear that reptiles and amphibians are, in fact, quite different animals, and P.A. Latreille erected the class ''Batracia'' (1825) for the latter, dividing the

It was not until the beginning of the 19th century that it became clear that reptiles and amphibians are, in fact, quite different animals, and P.A. Latreille erected the class ''Batracia'' (1825) for the latter, dividing the tetrapod

A tetrapod (; from Ancient Greek :wiktionary:τετρα-#Ancient Greek, τετρα- ''(tetra-)'' 'four' and :wiktionary:πούς#Ancient Greek, πούς ''(poús)'' 'foot') is any four-Limb (anatomy), limbed vertebrate animal of the clade Tetr ...

s into the four familiar classes of reptiles, amphibians, birds, and mammals. The British anatomist T.H. Huxley made Latreille's definition popular and, together with Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist and paleontology, palaeontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkabl ...

, expanded Reptilia to include the various fossil "antediluvian

The antediluvian (alternatively pre-diluvian or pre-flood) period is the time period chronicled in the Bible between the fall of man and the Genesis flood narrative in biblical cosmology. The term was coined by Thomas Browne (1605–1682). The n ...

monsters", including dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic Geological period, period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the #Evolutio ...

s and the mammal-like (synapsid

Synapsida is a diverse group of tetrapod vertebrates that includes all mammals and their extinct relatives. It is one of the two major clades of the group Amniota, the other being the more diverse group Sauropsida (which includes all extant rept ...

) ''Dicynodon

''Dicynodon'' (from Ancient Greek '' δίς'' "two" and '' κυνόδους'' "canine teeth", often translated to "two canine-teeth" or "two dog-teeth") is a genus of dicynodont therapsid that lived in southern and eastern Africa during the Lat ...

'' he helped describe. This was not the only possible classification scheme: In the Hunterian lectures delivered at the Royal College of Surgeons

The Royal College of Surgeons is an ancient college (a form of corporation) established in England to regulate the activity of surgeons. Derivative organisations survive in many present and former members of the Commonwealth. These organisations ...

in 1863, Huxley grouped the vertebrates into mammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

s, sauroids, and ichthyoids (the latter containing the fishes and amphibians). He subsequently proposed the names of Sauropsida

Sauropsida (Greek language, Greek for "lizard faces") is a clade of amniotes, broadly equivalent to the Class (biology), class Reptile, Reptilia, though typically used in a broader sense to also include extinct stem-group relatives of modern repti ...

and Ichthyopsida

The anamniotes are an informal group of craniates comprising all fish and amphibians, which lay their eggs in aquatic environments. They are distinguished from the amniotes (reptiles, birds and mammals), which can reproduce on dry land either b ...

for the latter two groups. In 1866, Haeckel

Ernst Heinrich Philipp August Haeckel (; ; 16 February 1834 – 9 August 1919) was a German zoologist, naturalist, eugenicist, philosopher, physician, professor, marine biologist and artist. He discovered, described and named thousands of new s ...

demonstrated that vertebrates could be divided based on their reproductive strategies, and that reptiles, birds, and mammals were united by the amniotic egg

Amniotes are tetrapod vertebrate animals belonging to the clade Amniota, a large group that comprises the vast majority of living terrestrial and semiaquatic vertebrates. Amniotes evolved from amphibious stem tetrapod ancestors during the C ...

.

The terms ''Sauropsida'' ("lizard faces") and '' Theropsida'' ("beast faces") were used again in 1916 by E.S. Goodrich to distinguish between lizards, birds, and their relatives on the one hand (Sauropsida) and mammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

s and their extinct relatives (Theropsida) on the other. Goodrich supported this division by the nature of the hearts and blood vessels in each group, and other features, such as the structure of the forebrain. According to Goodrich, both lineages evolved from an earlier stem group, Protosauria ("first lizards") in which he included some animals today considered reptile-like amphibians, as well as early reptiles.Procolophonia

Procolophonia is an extinct suborder (clade) of herbivorous reptiles that lived from the Middle Permian till the end of the Triassic period. They were originally included as a suborder of the Cotylosauria (later renamed Captorhinida Carroll ...

, Eosuchia

Eosuchians are an extinct order of diapsid reptiles. Depending on which taxa are included the order may have ranged from the late Carboniferous to the Eocene but the consensus is that eosuchians are confined to the Permian and Triassic.

Eosuchi ...

, Millerosauria, Chelonia (turtles), Squamata

Squamata (, Latin ''squamatus'', 'scaly, having scales') is the largest Order (biology), order of reptiles; most members of which are commonly known as Lizard, lizards, with the group also including Snake, snakes. With over 11,991 species, it i ...

(lizards and snakes), Rhynchocephalia

Rhynchocephalia (; ) is an order of lizard-like reptiles that includes only one living species, the tuatara (''Sphenodon punctatus'') of New Zealand. Despite its current lack of diversity, during the Mesozoic rhynchocephalians were a speciose g ...

, Crocodilia

Crocodilia () is an order of semiaquatic, predatory reptiles that are known as crocodilians. They first appeared during the Late Cretaceous and are the closest living relatives of birds. Crocodilians are a type of crocodylomorph pseudosuchia ...

, " thecodonts" (paraphyletic

Paraphyly is a taxonomic term describing a grouping that consists of the grouping's last common ancestor and some but not all of its descendant lineages. The grouping is said to be paraphyletic ''with respect to'' the excluded subgroups. In co ...

basal Archosaur

Archosauria () or archosaurs () is a clade of diapsid sauropsid tetrapods, with birds and crocodilians being the only extant taxon, extant representatives. Although broadly classified as reptiles, which traditionally exclude birds, the cladistics ...

ia), non- avian dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic Geological period, period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the #Evolutio ...

s, pterosaur

Pterosaurs are an extinct clade of flying reptiles in the order Pterosauria. They existed during most of the Mesozoic: from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous (228 million to 66 million years ago). Pterosaurs are the earli ...

s, ichthyosaur

Ichthyosauria is an order of large extinct marine reptiles sometimes referred to as "ichthyosaurs", although the term is also used for wider clades in which the order resides.

Ichthyosaurians thrived during much of the Mesozoic era; based on fo ...

s, and sauropterygia

Sauropterygia ("lizard flippers") is an extinct taxon of diverse, aquatic diapsid reptiles that developed from terrestrial ancestors soon after the end-Permian extinction and flourished during the Triassic before all except for the Plesiosau ...

ns.occipital condyle

The occipital condyles are undersurface protuberances of the occipital bone in vertebrates, which function in articulation with the superior facets of the Atlas (anatomy), atlas vertebra.

The condyles are oval or reniform (kidney-shaped) in shape ...

, a jaw joint formed by the quadrate and articular

The articular bone is part of the lower jaw of most vertebrates, including most jawed fish, amphibians, birds and various kinds of reptiles, as well as ancestral mammals.

Anatomy

In most vertebrates, the articular bone is connected to two o ...

bones, and certain characteristics of the vertebrae

Each vertebra (: vertebrae) is an irregular bone with a complex structure composed of bone and some hyaline cartilage, that make up the vertebral column or spine, of vertebrates. The proportions of the vertebrae differ according to their spinal ...

. The animals singled out by these formulations, the amniote

Amniotes are tetrapod vertebrate animals belonging to the clade Amniota, a large group that comprises the vast majority of living terrestrial animal, terrestrial and semiaquatic vertebrates. Amniotes evolution, evolved from amphibious Stem tet ...

s other than the mammals and the birds, are still those considered reptiles today. The synapsid/sauropsid division supplemented another approach, one that split the reptiles into four subclasses based on the number and position of

The synapsid/sauropsid division supplemented another approach, one that split the reptiles into four subclasses based on the number and position of temporal fenestra

Temporal fenestrae are openings in the temporal region of the skull of some amniotes, behind the orbit (eye socket). These openings have historically been used to track the evolution and affinities of reptiles. Temporal fenestrae are commonly (al ...

e, openings in the sides of the skull behind the eyes. This classification was initiated by Henry Fairfield Osborn

Henry Fairfield Osborn, Sr. (August 8, 1857 – November 6, 1935) was an American paleontologist, geologist and eugenics advocate. He was professor of anatomy at Columbia University, president of the American Museum of Natural History for 25 y ...

and elaborated and made popular by Romer

Romer, Römer, Roemer, or similar may refer to:

* Romer (surname), includes a list of people with the name

* Romer (tool), a cartographic device also known as a reference card

* Rømer scale, a disused temperature scale named after Ole Rømer

* ...

's classic ''Vertebrate Paleontology

Vertebrate paleontology is the subfield of paleontology that seeks to discover, through the study of fossilized remains, the behavior, reproduction and appearance of extinct vertebrates (animals with vertebrae and their descendants). It also t ...

''.Anapsid

An anapsid is an amniote whose skull lacks one or more skull openings (fenestra, or fossae) near the temples. Traditionally, the Anapsida are considered the most primitive subclass of amniotes, the ancestral stock from which Synapsida and Dia ...

a – no fenestrae – cotylosaurs and chelonia (turtle

Turtles are reptiles of the order (biology), order Testudines, characterized by a special turtle shell, shell developed mainly from their ribs. Modern turtles are divided into two major groups, the Pleurodira (side necked turtles) and Crypt ...

s and relatives)

* Synapsida

Synapsida is a diverse group of tetrapod vertebrates that includes all mammals and their extinct relatives. It is one of the two major clades of the group Amniota, the other being the more diverse group Sauropsida (which includes all extant rep ...

– one low fenestra – pelycosaur

Pelycosaur ( ) is an older term for basal or primitive Late Paleozoic synapsids, excluding the therapsids and their descendants. Previously, the term mammal-like reptile was used, and Pelycosauria was considered an order, but this is now thoug ...

s and therapsids (the 'mammal-like reptiles

Synapsida is a diverse group of tetrapod vertebrates that includes all mammals and their extinct relatives. It is one of the two major clades of the group Amniota, the other being the more diverse group Sauropsida (which includes all extant rept ...

')

* Euryapsida __NOTOC__

Euryapsida is a polyphyletic (unnatural, as the various members are not closely related) group of sauropsids that are distinguished by a single temporal fenestra, an opening behind the orbit, under which the post-orbital and squamosal bo ...

– one high fenestra (above the postorbital and squamosal) – protorosaurs (small, early lizard-like reptiles) and the marine sauropterygia

Sauropterygia ("lizard flippers") is an extinct taxon of diverse, aquatic diapsid reptiles that developed from terrestrial ancestors soon after the end-Permian extinction and flourished during the Triassic before all except for the Plesiosau ...

ns and ichthyosaurs, the latter called Parapsida in Osborn's work.

* Diapsida – two fenestrae – most reptiles, including lizards, snakes, crocodilian

Crocodilia () is an Order (biology), order of semiaquatic, predatory reptiles that are known as crocodilians. They first appeared during the Late Cretaceous and are the closest living relatives of birds. Crocodilians are a type of crocodylomorp ...

s, dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic Geological period, period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the #Evolutio ...

s and pterosaur

Pterosaurs are an extinct clade of flying reptiles in the order Pterosauria. They existed during most of the Mesozoic: from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous (228 million to 66 million years ago). Pterosaurs are the earli ...

s.

The composition of Euryapsida was uncertain. Ichthyosaurs were, at times, considered to have arisen independently of the other euryapsids, and given the older name Parapsida. Parapsida was later discarded as a group for the most part (ichthyosaurs being classified as ''incertae sedis'' or with Euryapsida). However, four (or three if Euryapsida is merged into Diapsida) subclasses remained more or less universal for non-specialist work throughout the 20th century. It has largely been abandoned by recent researchers: In particular, the anapsid condition has been found to occur so variably among unrelated groups that it is not now considered a useful distinction.

The composition of Euryapsida was uncertain. Ichthyosaurs were, at times, considered to have arisen independently of the other euryapsids, and given the older name Parapsida. Parapsida was later discarded as a group for the most part (ichthyosaurs being classified as ''incertae sedis'' or with Euryapsida). However, four (or three if Euryapsida is merged into Diapsida) subclasses remained more or less universal for non-specialist work throughout the 20th century. It has largely been abandoned by recent researchers: In particular, the anapsid condition has been found to occur so variably among unrelated groups that it is not now considered a useful distinction.

Phylogenetics and modern definition

By the early 21st century, vertebrate paleontologists were beginning to adopt phylogenetic taxonomy, in which all groups are defined in such a way as to be clade, monophyletic; that is, groups which include all descendants of a particular ancestor. The reptiles as historically defined are paraphyletic

Paraphyly is a taxonomic term describing a grouping that consists of the grouping's last common ancestor and some but not all of its descendant lineages. The grouping is said to be paraphyletic ''with respect to'' the excluded subgroups. In co ...

, since they exclude both birds and mammals. These respectively evolved from dinosaurs and from early therapsids, both of which were traditionally called "reptiles".crocodilian

Crocodilia () is an Order (biology), order of semiaquatic, predatory reptiles that are known as crocodilians. They first appeared during the Late Cretaceous and are the closest living relatives of birds. Crocodilians are a type of crocodylomorp ...

s than the latter are to the rest of extant reptiles. Colin Tudge wrote:

Mammals are a clade

In biology, a clade (), also known as a Monophyly, monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that is composed of a common ancestor and all of its descendants. Clades are the fundamental unit of cladistics, a modern approach t ...

, and therefore the Phylogenetic nomenclature, cladists are happy to acknowledge the traditional taxon Mammalia; and birds, too, are a clade, universally ascribed to the formal taxon bird, Aves. Mammalia and Aves are, in fact, subclades within the grand clade of the Amniota. But the traditional class Reptilia is not a clade. It is just a section of the clade Amniota: The section that is left after the Mammalia and Aves have been hived off. It cannot be defined by synapomorphy, synapomorphies, as is the proper way. Instead, it is defined by a combination of the features it has and the features it lacks: reptiles are the amniotes that lack fur or feathers. At best, the cladists suggest, we could say that the traditional Reptilia are 'non-avian, non-mammalian amniotes'.

Despite the early proposals for replacing the paraphyletic Reptilia with a monophyletic Sauropsida

Sauropsida (Greek language, Greek for "lizard faces") is a clade of amniotes, broadly equivalent to the Class (biology), class Reptile, Reptilia, though typically used in a broader sense to also include extinct stem-group relatives of modern repti ...

, which includes birds, that term was never adopted widely or, when it was, was not applied consistently. When Sauropsida was used, it often had the same content or even the same definition as Reptilia. In 1988, Jacques Gauthier proposed a cladistics, cladistic definition of Reptilia as a monophyletic node-based crown group containing turtles, lizards and snakes, crocodilians, and birds, their common ancestor and all its descendants. While Gauthier's definition was close to the modern consensus, nonetheless, it became considered inadequate because the actual relationship of turtles to other reptiles was not yet well understood at this time.

When Sauropsida was used, it often had the same content or even the same definition as Reptilia. In 1988, Jacques Gauthier proposed a cladistics, cladistic definition of Reptilia as a monophyletic node-based crown group containing turtles, lizards and snakes, crocodilians, and birds, their common ancestor and all its descendants. While Gauthier's definition was close to the modern consensus, nonetheless, it became considered inadequate because the actual relationship of turtles to other reptiles was not yet well understood at this time.[ Major revisions since have included the reassignment of synapsids as non-reptiles, and classification of turtles as diapsids.][ Gauthier 1994 and Laurin and Reisz 1995's definition of Sauropsida defined the scope of the group as distinct and broader than that of Reptilia, encompassing Mesosauridae as well as Reptilia ''sensu stricto''.][ Modesto and Anderson reviewed the many previous definitions and proposed a modified definition, which they intended to retain most traditional content of the group while keeping it stable and monophyletic. They defined Reptilia as all amniotes closer to ''Lacerta agilis'' and ''Crocodylus niloticus'' than to ''Homo sapiens''. This stem-based definition is equivalent to the more common definition of Sauropsida, which Modesto and Anderson synonymized with Reptilia, since the latter is better known and more frequently used. Unlike most previous definitions of Reptilia, however, Modesto and Anderson's definition includes birds, as they are within the clade that includes both lizards and crocodiles.][

]

Taxonomy

General classification of extinct and living reptiles, focusing on major groups.Sauropsida

Sauropsida (Greek language, Greek for "lizard faces") is a clade of amniotes, broadly equivalent to the Class (biology), class Reptile, Reptilia, though typically used in a broader sense to also include extinct stem-group relatives of modern repti ...

**Parareptilia

** Eureptilia

***Captorhinidae

***Diapsida

****Araeoscelidia

****Neodiapsida

*****Drepanosauromorpha (placement uncertain)

*****Younginiformes (paraphyletic)

*****Ichthyosauromorpha (placement uncertain)

*****Thalattosauria (placement uncertain)

*****Sauria

******Lepidosauromorpha

Lepidosauromorpha (in PhyloCode known as Pan-Lepidosauria) is a group of reptiles comprising all diapsids closer to lizards than to archosaurs (which include crocodiles and birds). The only living sub-group is the Lepidosauria, which contains tw ...

*******Lepidosauriformes

********Rhynchocephalia

Rhynchocephalia (; ) is an order of lizard-like reptiles that includes only one living species, the tuatara (''Sphenodon punctatus'') of New Zealand. Despite its current lack of diversity, during the Mesozoic rhynchocephalians were a speciose g ...

(tuatara)

********Squamata

Squamata (, Latin ''squamatus'', 'scaly, having scales') is the largest Order (biology), order of reptiles; most members of which are commonly known as Lizard, lizards, with the group also including Snake, snakes. With over 11,991 species, it i ...

(lizards and snakes)

******Choristodera (placement uncertain)

******Sauropterygia (placement uncertain)

******Pantestudines (turtles and kin, placement uncertain)

******Archosauromorpha

Archosauromorpha ( Greek for "ruling lizard forms") is a clade of diapsid reptiles containing all reptiles more closely related to archosaurs (such as crocodilians and dinosaurs, including birds) than to lepidosaurs (such as tuataras, lizards, ...

*******Protorosauria (paraphyletic)

*******Rhynchosauria

*******Allokotosauria

*******Archosauriformes

********Phytosauria

********Archosauria

*********Pseudosuchia

**********Crocodilia

Crocodilia () is an order of semiaquatic, predatory reptiles that are known as crocodilians. They first appeared during the Late Cretaceous and are the closest living relatives of birds. Crocodilians are a type of crocodylomorph pseudosuchia ...

(crocodilians)

*********Avemetatarsalia/Ornithodira

**********Pterosauria

**********Dinosauria

***********Ornithischia

***********Saurischia (including birds (Bird, Aves))

Phylogeny

The cladistics#Cladograms, cladogram presented here illustrates the "family tree" of reptiles, and follows a simplified version of the relationships found by M.S. Lee, in 2013.[ though a few have recovered turtles as Lepidosauromorpha instead. The cladogram below used a combination of genetic (molecular) and fossil (morphological) data to obtain its results.][

]

The position of turtles

The placement of turtles has historically been highly variable. Classically, turtles were considered to be related to the primitive anapsid reptiles.Sauropsida

Sauropsida (Greek language, Greek for "lizard faces") is a clade of amniotes, broadly equivalent to the Class (biology), class Reptile, Reptilia, though typically used in a broader sense to also include extinct stem-group relatives of modern repti ...

, outside the saurian clade altogether.

Evolutionary history

Origin of the reptiles

The origin of the reptiles lies about 310–320 million years ago, in the steaming swamps of the late

The origin of the reptiles lies about 310–320 million years ago, in the steaming swamps of the late Carboniferous

The Carboniferous ( ) is a Geologic time scale, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), system of the Paleozoic era (geology), era that spans 60 million years, from the end of the Devonian Period Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the ...

period, when the first reptiles evolved from advanced Reptiliomorpha, reptiliomorphs.[

]

The oldest known animal that may have been an amniote

Amniotes are tetrapod vertebrate animals belonging to the clade Amniota, a large group that comprises the vast majority of living terrestrial animal, terrestrial and semiaquatic vertebrates. Amniotes evolution, evolved from amphibious Stem tet ...

is ''Casineria'' (though it may have been a Temnospondyli, temnospondyl). A series of footprints from the fossil strata of Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada, located on its east coast. It is one of the three Maritime Canada, Maritime provinces and Population of Canada by province and territory, most populous province in Atlan ...

dated to show typical reptilian toes and imprints of scales. These tracks are attributed to ''Hylonomus

''Hylonomus'' (; ''hylo-'' "forest" + ''nomos'' "dweller") is an extinct genus of reptile that lived during the Bashkirian stage of the Late Carboniferous. It is the earliest known crown group amniote and the oldest known unquestionable reptile, ...

'', the oldest unquestionable reptile known.

It was a small, lizard-like animal, about long, with numerous sharp teeth indicating an insectivorous diet.reptiliomorph

Reptiliomorpha (meaning reptile-shaped; in PhyloCode known as ''Pan-Amniota'') is a clade containing the amniotes and those tetrapods that share a more recent common ancestor with amniotes than with living amphibians (lissamphibians). It was defi ...

rather than a true amniote

Amniotes are tetrapod vertebrate animals belonging to the clade Amniota, a large group that comprises the vast majority of living terrestrial animal, terrestrial and semiaquatic vertebrates. Amniotes evolution, evolved from amphibious Stem tet ...

) and ''Paleothyris'', both of similar build and presumably similar habit.

However, microsaurs have been at times considered true reptiles, so an earlier origin is possible.

Rise of the reptiles

The earliest amniotes, including stem-reptiles (those amniotes closer to modern reptiles than to mammals), were largely overshadowed by larger stem-tetrapods, such as ''Cochleosaurus'', and remained a small, inconspicuous part of the fauna until the Carboniferous Rainforest Collapse.

Anapsids, synapsids, diapsids, and sauropsids

It was traditionally assumed that the first reptiles retained an anapsid skull inherited from their ancestors.

It was traditionally assumed that the first reptiles retained an anapsid skull inherited from their ancestors.synapsid

Synapsida is a diverse group of tetrapod vertebrates that includes all mammals and their extinct relatives. It is one of the two major clades of the group Amniota, the other being the more diverse group Sauropsida (which includes all extant rept ...

-like openings (see below) in the skull roof of the skulls of several members of Parareptilia (the clade containing most of the amniotes traditionally referred to as "anapsids"), including Lanthanosuchoidea, lanthanosuchoids, Millerettidae, millerettids, Bolosauridae, bolosaurids, some Nycteroleteridae, nycteroleterids, some Procolophonoidea, procolophonoids and at least some mesosaurs[ These animals are traditionally referred to as "anapsids", and form a ]paraphyletic

Paraphyly is a taxonomic term describing a grouping that consists of the grouping's last common ancestor and some but not all of its descendant lineages. The grouping is said to be paraphyletic ''with respect to'' the excluded subgroups. In co ...

basic stock from which other groups evolved.[ Very shortly after the first amniotes appeared, a lineage called ]Synapsida

Synapsida is a diverse group of tetrapod vertebrates that includes all mammals and their extinct relatives. It is one of the two major clades of the group Amniota, the other being the more diverse group Sauropsida (which includes all extant rep ...

split off; this group was characterized by a temporal opening in the skull behind each eye giving room for the jaw muscle to move. These are the "mammal-like amniotes", or stem-mammals, that later gave rise to the true mammals. Soon after, another group evolved a similar trait, this time with a double opening behind each eye, earning them the name Diapsida ("two arches").[ The function of the holes in these groups was to lighten the skull and give room for the jaw muscles to move, allowing for a more powerful bite.]

Permian reptiles

With the close of the Carboniferous

The Carboniferous ( ) is a Geologic time scale, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), system of the Paleozoic era (geology), era that spans 60 million years, from the end of the Devonian Period Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the ...

, the amniotes became the dominant tetrapod fauna. While primitive, terrestrial reptiliomorpha, reptiliomorphs still existed, the synapsid amniotes evolved the first truly terrestrial megafauna (giant animals) in the form of pelycosaurs, such as ''Edaphosaurus'' and the carnivorous ''Dimetrodon''. In the mid-Permian period, the climate became drier, resulting in a change of fauna: The pelycosaurs were replaced by the therapsids.[Edwin Harris Colbert, Colbert, E.H. & Morales, M. (2001): ''Evolution of the Vertebrates, Colbert's Evolution of the Vertebrates: A History of the Backboned Animals Through Time''. 4th edition. John Wiley & Sons, Inc, New York. .]

The parareptiles, whose massive skull roofs had no postorbital holes, continued and flourished throughout the Permian. The pareiasaurian parareptiles reached giant proportions in the late Permian, eventually disappearing at the close of the period (the turtles being possible survivors).Archosauromorpha

Archosauromorpha ( Greek for "ruling lizard forms") is a clade of diapsid reptiles containing all reptiles more closely related to archosaurs (such as crocodilians and dinosaurs, including birds) than to lepidosaurs (such as tuataras, lizards, ...

(forebears of turtle

Turtles are reptiles of the order (biology), order Testudines, characterized by a special turtle shell, shell developed mainly from their ribs. Modern turtles are divided into two major groups, the Pleurodira (side necked turtles) and Crypt ...

s, crocodilian

Crocodilia () is an Order (biology), order of semiaquatic, predatory reptiles that are known as crocodilians. They first appeared during the Late Cretaceous and are the closest living relatives of birds. Crocodilians are a type of crocodylomorp ...

s, and dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic Geological period, period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the #Evolutio ...

s) and the Lepidosauromorpha

Lepidosauromorpha (in PhyloCode known as Pan-Lepidosauria) is a group of reptiles comprising all diapsids closer to lizards than to archosaurs (which include crocodiles and birds). The only living sub-group is the Lepidosauria, which contains tw ...

(predecessors of modern lizards, snakes, and tuataras). Both groups remained lizard-like and relatively small and inconspicuous during the Permian.

Mesozoic reptiles

The close of the Permian saw the greatest mass extinction known (see the Permian–Triassic extinction event), an event prolonged by the combination of two or more distinct extinction pulses.dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic Geological period, period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the #Evolutio ...

s and pterosaur

Pterosaurs are an extinct clade of flying reptiles in the order Pterosauria. They existed during most of the Mesozoic: from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous (228 million to 66 million years ago). Pterosaurs are the earli ...

s, as well as the ancestors of crocodilian

Crocodilia () is an Order (biology), order of semiaquatic, predatory reptiles that are known as crocodilians. They first appeared during the Late Cretaceous and are the closest living relatives of birds. Crocodilians are a type of crocodylomorp ...

s. Since reptiles, first rauisuchians and then dinosaurs, dominated the Mesozoic era, the interval is popularly known as the "Age of Reptiles". The dinosaurs also developed smaller forms, including the feather-bearing smaller theropoda, theropods. In the Cretaceous period, these gave rise to the first true birds.Lepidosauromorpha

Lepidosauromorpha (in PhyloCode known as Pan-Lepidosauria) is a group of reptiles comprising all diapsids closer to lizards than to archosaurs (which include crocodiles and birds). The only living sub-group is the Lepidosauria, which contains tw ...

, containing lizards and tuataras, as well as their fossil relatives. Lepidosauromorpha contained at least one major group of the Mesozoic sea reptiles: the mosasaurs, which lived during the Cretaceous period. The phylogenetic placement of other main groups of fossil sea reptiles – the ichthyopterygians (including ichthyosaur

Ichthyosauria is an order of large extinct marine reptiles sometimes referred to as "ichthyosaurs", although the term is also used for wider clades in which the order resides.

Ichthyosaurians thrived during much of the Mesozoic era; based on fo ...

s) and the sauropterygia

Sauropterygia ("lizard flippers") is an extinct taxon of diverse, aquatic diapsid reptiles that developed from terrestrial ancestors soon after the end-Permian extinction and flourished during the Triassic before all except for the Plesiosau ...

ns, which evolved in the early Triassic – is more controversial. Different authors linked these groups either to lepidosauromorphs

Cenozoic reptiles

The close of the Cretaceous period saw the demise of the Mesozoic era reptilian megafauna (see the

The close of the Cretaceous period saw the demise of the Mesozoic era reptilian megafauna (see the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event

The Cretaceous–Paleogene (K–Pg) extinction event, also known as the K–T extinction, was the extinction event, mass extinction of three-quarters of the plant and animal species on Earth approximately 66 million years ago. The event cau ...

, also known as K-T extinction event). Of the large marine reptiles, only sea turtles were left; and of the non-marine large reptiles, only the semi-aquatic crocodilian

Crocodilia () is an Order (biology), order of semiaquatic, predatory reptiles that are known as crocodilians. They first appeared during the Late Cretaceous and are the closest living relatives of birds. Crocodilians are a type of crocodylomorp ...

s and broadly similar Choristodera, choristoderes survived the extinction, with last members of the latter, the lizard-like ''Lazarussuchus'', becoming extinct in the Miocene. Of the great host of dinosaurs dominating the Mesozoic, only the small beaked birds survived. This dramatic extinction pattern at the end of the Mesozoic led into the Cenozoic. Mammals and birds filled the empty niches left behind by the reptilian megafauna and, while reptile diversification slowed, bird and mammal diversification took an exponential turn.[ However, reptiles were still important components of the megafauna, particularly in the form of large and giant tortoises.]

Morphology and physiology

Circulation

All Lepidosauria, lepidosaurs and turtle

Turtles are reptiles of the order (biology), order Testudines, characterized by a special turtle shell, shell developed mainly from their ribs. Modern turtles are divided into two major groups, the Pleurodira (side necked turtles) and Crypt ...

s have a three-chambered heart consisting of two atrium (heart), atria, one variably partitioned ventricle (heart), ventricle, and two aortas that lead to the systemic circulation. The degree of mixing of oxygenated and deoxygenated blood in the three-chambered heart varies depending on the species and physiological state. Under different conditions, deoxygenated blood can be shunted back to the body or oxygenated blood can be shunted back to the lungs. This variation in blood flow has been hypothesized to allow more effective thermoregulation and longer diving times for aquatic species, but has not been shown to be a fitness (biology), fitness advantage.

For example, iguana hearts, like the majority of the Squamata, squamate hearts, are composed of three chambers with two aorta and one ventricle, cardiac involuntary muscles. The main structures of the heart are the sinus venosus, the pacemaker, the Atrium (heart), left atrium, the Atrium (heart), right atrium, the Heart valve, atrioventricular valve, the cavum venosum, cavum arteriosum, the cavum pulmonale, the muscular ridge, the ventricular ridge, pulmonary veins, and paired aortic arches.

Some squamate species (e.g., pythons and monitor lizards) have three-chambered hearts that become functionally four-chambered hearts during contraction. This is made possible by a muscular ridge that subdivides the ventricle during cardiac cycle, ventricular diastole and completely divides it during systole (medicine), ventricular systole. Because of this ridge, some of these squamata, squamates are capable of producing ventricular pressure differentials that are equivalent to those seen in mammalian and avian hearts.

For example, iguana hearts, like the majority of the Squamata, squamate hearts, are composed of three chambers with two aorta and one ventricle, cardiac involuntary muscles. The main structures of the heart are the sinus venosus, the pacemaker, the Atrium (heart), left atrium, the Atrium (heart), right atrium, the Heart valve, atrioventricular valve, the cavum venosum, cavum arteriosum, the cavum pulmonale, the muscular ridge, the ventricular ridge, pulmonary veins, and paired aortic arches.

Some squamate species (e.g., pythons and monitor lizards) have three-chambered hearts that become functionally four-chambered hearts during contraction. This is made possible by a muscular ridge that subdivides the ventricle during cardiac cycle, ventricular diastole and completely divides it during systole (medicine), ventricular systole. Because of this ridge, some of these squamata, squamates are capable of producing ventricular pressure differentials that are equivalent to those seen in mammalian and avian hearts.

Crocodilia

Crocodilia () is an order of semiaquatic, predatory reptiles that are known as crocodilians. They first appeared during the Late Cretaceous and are the closest living relatives of birds. Crocodilians are a type of crocodylomorph pseudosuchia ...

ns have an anatomically four-chambered heart, similar to bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class (biology), class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the Oviparity, laying of Eggshell, hard-shelled eggs, a high Metabolism, metabolic rate, a fou ...

s, but also have two systemic aortas and are therefore capable of bypassing their pulmonary circulation. In turtles, the ventricle is not perfectly divided, so a mix of aerated and nonaerated blood can occur.

Metabolism

Modern non-avian reptiles exhibit some form of Ectotherm, cold-bloodedness (i.e. some mix of poikilothermy,

Modern non-avian reptiles exhibit some form of Ectotherm, cold-bloodedness (i.e. some mix of poikilothermy, ectotherm

An ectotherm (), more commonly referred to as a "cold-blooded animal", is an animal in which internal physiological sources of heat, such as blood, are of relatively small or of quite negligible importance in controlling body temperature.Dav ...

y, and bradymetabolism) so that they have limited physiological means of keeping the body temperature constant and often rely on external sources of heat. Due to a less stable core temperature than bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class (biology), class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the Oviparity, laying of Eggshell, hard-shelled eggs, a high Metabolism, metabolic rate, a fou ...

s and mammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

s, reptilian biochemistry requires enzymes capable of maintaining efficiency over a greater range of temperatures than in the case for warm-blooded animals. The optimum body temperature range varies with species, but is typically below that of warm-blooded animals; for many lizards, it falls in the range, while extreme heat-adapted species, like the American desert iguana ''Dipsosaurus dorsalis'', can have optimal physiological temperatures in the mammalian range, between . While the optimum temperature is often encountered when the animal is active, the low basal metabolism makes body temperature drop rapidly when the animal is inactive.

As in all animals, reptilian muscle action produces heat. In large reptiles, like leatherback turtles, the low surface-to-volume ratio allows this metabolically produced heat to keep the animals warmer than their environment even though they do not have a warm-blooded metabolism. This form of homeothermy is called gigantothermy; it has been suggested as having been common in large dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic Geological period, period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the #Evolutio ...

s and other extinct large-bodied reptiles.

The benefit of a low resting metabolism is that it requires far less fuel to sustain bodily functions. By using temperature variations in their surroundings, or by remaining cold when they do not need to move, reptiles can save considerable amounts of energy compared to endothermic animals of the same size. A crocodile needs from a tenth to a fifth of the food necessary for a lion of the same weight and can live half a year without eating.

Respiratory system

All reptiles breathe using lungs. Aquatic turtle

Turtles are reptiles of the order (biology), order Testudines, characterized by a special turtle shell, shell developed mainly from their ribs. Modern turtles are divided into two major groups, the Pleurodira (side necked turtles) and Crypt ...

s have developed more permeable skin, and some species have modified their cloaca to increase the area for gas exchange. Even with these adaptations, breathing is never fully accomplished without lungs. Lung ventilation is accomplished differently in each main reptile group. In squamata, squamates, the lungs are ventilated almost exclusively by the axial musculature. This is also the same musculature that is used during locomotion. Because of this Carrier's constraint, constraint, most squamates are forced to hold their breath during intense runs. Some, however, have found a way around it. Varanids, and a few other lizard species, employ buccal pumping as a complement to their normal "axial breathing". This allows the animals to completely fill their lungs during intense locomotion, and thus remain aerobically active for a long time. Tupinambis, Tegu lizards are known to possess a proto-thoracic diaphragm, diaphragm, which separates the pulmonary cavity from the visceral cavity. While not actually capable of movement, it does allow for greater lung inflation, by taking the weight of the viscera off the lungs.

Crocodilia

Crocodilia () is an order of semiaquatic, predatory reptiles that are known as crocodilians. They first appeared during the Late Cretaceous and are the closest living relatives of birds. Crocodilians are a type of crocodylomorph pseudosuchia ...

ns actually have a muscular diaphragm that is analogous to the mammalian diaphragm. The difference is that the muscles for the crocodilian diaphragm pull the pubis (part of the pelvis, which is movable in crocodilians) back, which brings the liver down, thus freeing space for the lungs to expand. This type of diaphragmatic setup has been referred to as the "Liver, hepatic piston". The Bronchus, airways form a number of double tubular chambers within each lung. On inhalation and exhalation air moves through the airways in the same direction, thus creating a unidirectional airflow through the lungs. A similar system is found in birds, monitor lizards and iguanas.

Most reptiles lack a secondary palate, meaning that they must hold their breath while swallowing. Crocodilians have evolved a bony secondary palate that allows them to continue breathing while remaining submerged (and protect their brains against damage by struggling prey). Skinks (family Skink, Scincidae) also have evolved a bony secondary palate, to varying degrees. Snakes took a different approach and extended their trachea instead. Their tracheal extension sticks out like a fleshy straw, and allows these animals to swallow large prey without suffering from asphyxiation.

Turtles and tortoises

How

How turtle

Turtles are reptiles of the order (biology), order Testudines, characterized by a special turtle shell, shell developed mainly from their ribs. Modern turtles are divided into two major groups, the Pleurodira (side necked turtles) and Crypt ...

s breathe has been the subject of much study. To date, only a few species have been studied thoroughly enough to get an idea of how those turtles Breathing, breathe. The varied results indicate that turtles have found a variety of solutions to this problem.

The difficulty is that most turtle shells are rigid and do not allow for the type of expansion and contraction that other amniotes use to ventilate their lungs. Some turtles, such as the Indian flapshell (''Indian flapshell turtle, Lissemys punctata''), have a sheet of muscle that envelops the lungs. When it contracts, the turtle can exhale. When at rest, the turtle can retract the limbs into the body cavity and force air out of the lungs. When the turtle protracts its limbs, the pressure inside the lungs is reduced, and the turtle can suck air in. Turtle lungs are attached to the inside of the top of the shell (carapace), with the bottom of the lungs attached (via connective tissue) to the rest of the viscera. By using a series of special muscles (roughly equivalent to a thoracic diaphragm, diaphragm), turtles are capable of pushing their viscera up and down, resulting in effective respiration, since many of these muscles have attachment points in conjunction with their forelimbs (indeed, many of the muscles expand into the limb pockets during contraction).

Breathing during locomotion has been studied in three species, and they show different patterns. Adult female green sea turtles do not breathe as they crutch along their nesting beaches. They hold their breath during terrestrial locomotion and breathe in bouts as they rest. North American box turtles breathe continuously during locomotion, and the ventilation cycle is not coordinated with the limb movements.[

]

Sound production

Compared with frogs, birds, and mammals, reptiles are less vocal. Sound production is usually limited to wikt:hiss, hissing, which is produced merely by forcing air though a partly closed glottis and is not considered to be a true vocalization. The ability to vocalize exists in crocodilians, some lizards and turtles; and typically involves vibrating fold-like structures in the larynx or glottis. Some geckos and turtles possess true vocal cords, which have elastin-rich connective tissue.

Hearing in snakes

Hearing in humans relies on 3 parts of the ear; the outer ear that directs sound waves into the ear canal, the middle ear that transmits incoming sound waves to the inner ear, and the inner ear that helps in hearing and keeping their balance. Unlike humans and other mammals, snakes do not possess an outer ear, a middle ear, and a Tympanum (anatomy), tympanum but have an inner ear structure with cochleas directly connected to their jawbone. They are able to feel the vibrations generated from the sound waves in their jaw as they move on the ground. This is done by the use of mechanoreceptors, sensory nerves that run along the body of snakes directing the vibrations along the spinal nerves to the brain. Snakes have a sensitive auditory perception and can tell which direction sound being made is coming from so that they can sense the presence of prey or predator but it is still unclear how sensitive snakes are to sound waves traveling through the air.

Skin

Reptilian skin is covered in a horny Epidermis (zoology), epidermis, making it watertight and enabling reptiles to live on dry land, in contrast to amphibians. Compared to mammalian skin, that of reptiles is rather thin and lacks the thick dermis, dermal layer that produces leather in mammals.

Exposed parts of reptiles are protected by reptile scales, scales or scutes, sometimes with a bony base (osteoderms), forming armour (zoology), armor. In lepidosaurs, such as lizards and snakes, the whole skin is covered in overlapping epidermis (zoology), epidermal scales. Such scales were once thought to be typical of the class Reptilia as a whole, but are now known to occur only in lepidosaurs. The scales found in turtles and crocodiles are of dermis, dermal, rather than epidermal, origin and are properly termed scutes. In turtles, the body is hidden inside a hard shell composed of fused scutes.

Lacking a thick dermis, reptilian leather is not as strong as mammalian leather. It is used in leather-wares for decorative purposes for shoes, belts and handbags, particularly crocodile skin.

Reptilian skin is covered in a horny Epidermis (zoology), epidermis, making it watertight and enabling reptiles to live on dry land, in contrast to amphibians. Compared to mammalian skin, that of reptiles is rather thin and lacks the thick dermis, dermal layer that produces leather in mammals.

Exposed parts of reptiles are protected by reptile scales, scales or scutes, sometimes with a bony base (osteoderms), forming armour (zoology), armor. In lepidosaurs, such as lizards and snakes, the whole skin is covered in overlapping epidermis (zoology), epidermal scales. Such scales were once thought to be typical of the class Reptilia as a whole, but are now known to occur only in lepidosaurs. The scales found in turtles and crocodiles are of dermis, dermal, rather than epidermal, origin and are properly termed scutes. In turtles, the body is hidden inside a hard shell composed of fused scutes.

Lacking a thick dermis, reptilian leather is not as strong as mammalian leather. It is used in leather-wares for decorative purposes for shoes, belts and handbags, particularly crocodile skin.

Shedding

Reptiles shed their skin through a process called ecdysis which occurs continuously throughout their lifetime. In particular, younger reptiles tend to shed once every five to six weeks while adults shed three to four times a year. Younger reptiles shed more because of their rapid growth rate. Once full size, the frequency of shedding drastically decreases. The process of ecdysis involves forming a new layer of skin under the old one. Proteolysis, Proteolytic enzymes and Lymph, lymphatic fluid is secreted between the old and new layers of skin. Consequently, this lifts the old skin from the new one allowing shedding to occur.

Excretion

Excretion is performed mainly by two small kidneys. In diapsids, uric acid is the main nitrogenous waste product; turtles, like mammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

s, excrete mainly urea. Unlike the mammalian kidney, kidneys of mammals and birds, Kidney (vertebrates)#Reptile kidney, reptile kidneys are unable to produce liquid urine more concentrated than their body fluid. This is because they lack a specialized structure called a loop of Henle, which is present in the nephrons of birds and mammals. Because of this, many reptiles use the colon (anatomy), colon to aid in the reabsorption of water. Some are also able to take up water stored in the Urinary bladder, bladder. Excess salts are also excreted by nasal and lingual salt glands in some reptiles.

In all reptiles, the urinogenital ducts and the rectum both empty into an organ called a cloaca. In some reptiles, a midventral wall in the cloaca may open into a urinary bladder, but not all. It is present in all turtles and tortoises as well as most lizards, but is lacking in the monitor lizard, the legless lizards. It is absent in the snakes, alligators, and crocodiles.

Many turtles and lizards have proportionally very large bladders. Charles Darwin noted that the Galapagos tortoise had a bladder which could store up to 20% of its body weight. Such adaptations are the result of environments such as remote islands and deserts where water is very scarce. Other desert-dwelling reptiles have large bladders that can store a long-term reservoir of water for up to several months and aid in osmoregulation.

Turtles have two or more accessory urinary bladders, located lateral to the neck of the urinary bladder and dorsal to the pubis, occupying a significant portion of their body cavity. Their bladder is also usually bilobed with a left and right section. The right section is located under the liver, which prevents large stones from remaining in that side while the left section is more likely to have Bladder stone (animal), calculi.

Digestion

Most reptiles are insectivorous or carnivorous and have simple and comparatively short digestive tracts due to meat being fairly simple to break down and digest. Digestion is slower than in mammals, reflecting their lower resting metabolism and their inability to divide and masticate their food. Their poikilotherm metabolism has very low energy requirements, allowing large reptiles like crocodiles and large constrictors to live from a single large meal for months, digesting it slowly.

Most reptiles are insectivorous or carnivorous and have simple and comparatively short digestive tracts due to meat being fairly simple to break down and digest. Digestion is slower than in mammals, reflecting their lower resting metabolism and their inability to divide and masticate their food. Their poikilotherm metabolism has very low energy requirements, allowing large reptiles like crocodiles and large constrictors to live from a single large meal for months, digesting it slowly.[

While modern reptiles are predominantly carnivorous, during the early history of reptiles several groups produced some herbivorous megafauna: in the Paleozoic, the pareiasaurs; and in the Mesozoic several lines of ]dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic Geological period, period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the #Evolutio ...

s.[ Today, ]turtle

Turtles are reptiles of the order (biology), order Testudines, characterized by a special turtle shell, shell developed mainly from their ribs. Modern turtles are divided into two major groups, the Pleurodira (side necked turtles) and Crypt ...

s are the only predominantly herbivorous reptile group, but several lines of Agamidae, agamas and Iguanidae, iguanas have evolved to live wholly or partly on plants.[ Fossil gastroliths have been found associated with both ornithopods and sauropods, though whether they actually functioned as a gastric mill in the latter is disputed. Salt water crocodiles also use gastroliths as Sailing ballast, ballast, stabilizing them in the water or helping them to dive. A dual function as both stabilizing ballast and digestion aid has been suggested for gastroliths found in plesiosaurs.

]

Nerves

The reptilian nervous system contains the same basic part of the amphibian

Amphibians are ectothermic, anamniote, anamniotic, tetrapod, four-limbed vertebrate animals that constitute the class (biology), class Amphibia. In its broadest sense, it is a paraphyletic group encompassing all Tetrapod, tetrapods, but excl ...

brain, but the reptile cerebrum and cerebellum are slightly larger. Most typical sense organs are well developed with certain exceptions, most notably the snake's lack of external ears (middle and inner ears are present). There are twelve pairs of cranial nerves. Due to their short cochlea, reptiles use electrical tuning to expand their range of audible frequencies.

Vision

Most reptiles are Diurnality, diurnal animals. The vision is typically adapted to daylight conditions, with color vision and more advanced visual depth perception than in amphibians and most mammals.

Reptiles usually have excellent vision, allowing them to detect shapes and motions at long distances. They often have poor vision in low-light conditions. Birds, crocodiles and turtles have three types of Photoreceptor cell, photoreceptor: rod cell, rods, single Cone cell, cones and double cones, which gives them sharp color vision and enables them to see ultraviolet wavelengths.[

Some snakes have extra sets of visual organs (in the loosest sense of the word) in the form of Loreal pit, pits sensitive to infrared radiation (heat). Such heat-sensitive pits are particularly well developed in the pit vipers, but are also found in boidae, boas and pythonidae, pythons. These pits allow the snakes to sense the body heat of birds and mammals, enabling pit vipers to hunt rodents in the dark.

Most reptiles, as well as birds, possess a nictitating membrane, a translucent third eyelid which is drawn over the eye from the inner corner. In crocodilians, it protects its eyeball surface while allowing a degree of vision underwater. However, many squamates, geckos and snakes in particular, lack eyelids, which are replaced by a transparent scale. This is called the brille, spectacle, or eyecap. The brille is usually not visible, except for when the snake molts, and it protects the eyes from dust and dirt.

]

Reproduction

Reptiles generally sexual reproduction, reproduce sexually, though some are capable of asexual reproduction. All reproductive activity occurs through the cloaca, the single exit/entrance at the base of the tail where waste is also eliminated. Most reptiles have copulatory organs, which are usually retracted or inverted and stored inside the body. In turtles and crocodilians, the male has a single median penis, while squamates, including snakes and lizards, possess a pair of hemipenis, hemipenes, only one of which is typically used in each session. Tuatara, however, lack copulatory organs, and so the male and female simply press their cloacas together as the male discharges sperm.