Re-education In Communist Romania on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Re-education in Romanian communist prisons was a series of processes initiated after the establishment of the

Țurcanu and the group he was part of were moved to Pitești from Suceava on 21 April 1949. Țurcanu became in time an informant of the Operational Bureau, being supported by Iosif Nemes, head of the Operational Service. Aware that non-violent reeducation methods were not efficient, as the legionnaire students were refusing to affiliate to the communist agenda and the intelligence data was scarce, a violent reeducation program is initiated, at the direct proposal of Țurcanu and Marina.

The Pitești detention regime was optimal for such an initiative. In the second part of 1949, the conditions worsened considerably: the prison sections were isolated and the communication channels between the inmates cut off. The cells were over-crowded and the food had a low caloric content. (maximum 1,000 calories per day). There was little to no medical assistance, the sanitary program was done on a group basis, many did not get to the toilet in the allocated time and had to do it in their own food tins, which had to be later washed. Beatings from the guardians were common and the most severe penalties included the

Țurcanu and the group he was part of were moved to Pitești from Suceava on 21 April 1949. Țurcanu became in time an informant of the Operational Bureau, being supported by Iosif Nemes, head of the Operational Service. Aware that non-violent reeducation methods were not efficient, as the legionnaire students were refusing to affiliate to the communist agenda and the intelligence data was scarce, a violent reeducation program is initiated, at the direct proposal of Țurcanu and Marina.

The Pitești detention regime was optimal for such an initiative. In the second part of 1949, the conditions worsened considerably: the prison sections were isolated and the communication channels between the inmates cut off. The cells were over-crowded and the food had a low caloric content. (maximum 1,000 calories per day). There was little to no medical assistance, the sanitary program was done on a group basis, many did not get to the toilet in the allocated time and had to do it in their own food tins, which had to be later washed. Beatings from the guardians were common and the most severe penalties included the  Beating were ferocious, inmates were clubbed or trampled unconscious, many times unrecognizable after the violent treatment.

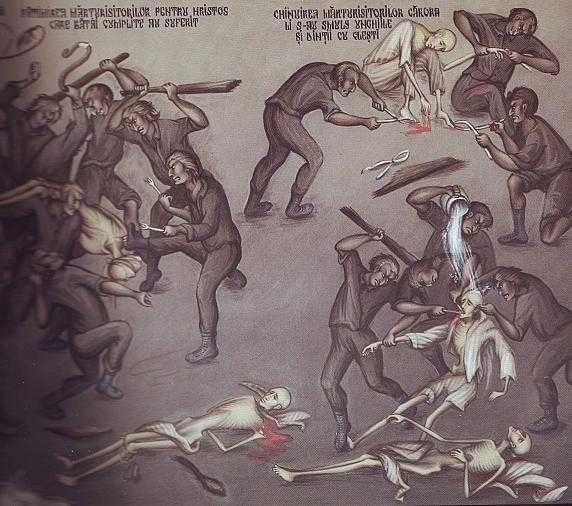

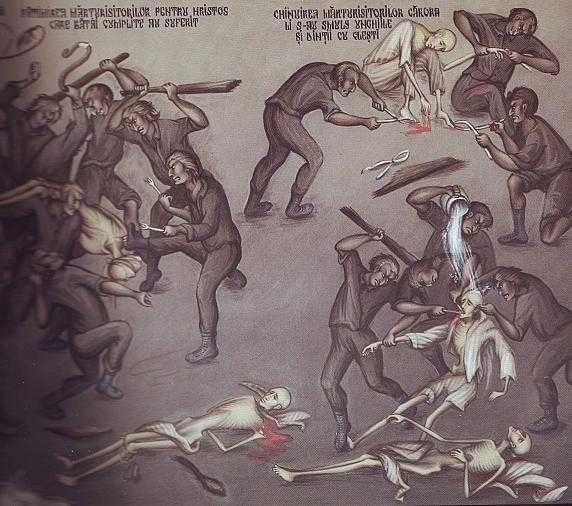

Tortures were varied; if initially the sole purpose was to ''humiliate the prisoners'', who were forced to wear the toilet bucket on their head, crawl on the floor or eat without using their hands, later it followed to reach an ''extensive physical wear'', which made them more susceptible to crack: they went for days without water, were forced to stay in uneasy positions such as lying down with the head raised and a needle pointing back of the neck or to remove and put back their shoe laces for hours on end; for the resistant ones, a ''total mental breakdown'' was attempted, as they were made to eat

Beating were ferocious, inmates were clubbed or trampled unconscious, many times unrecognizable after the violent treatment.

Tortures were varied; if initially the sole purpose was to ''humiliate the prisoners'', who were forced to wear the toilet bucket on their head, crawl on the floor or eat without using their hands, later it followed to reach an ''extensive physical wear'', which made them more susceptible to crack: they went for days without water, were forced to stay in uneasy positions such as lying down with the head raised and a needle pointing back of the neck or to remove and put back their shoe laces for hours on end; for the resistant ones, a ''total mental breakdown'' was attempted, as they were made to eat  The prison was T-shaped, and the prisoners were detained based on the conviction type: ''light offences'' (''correction'') was set up on the head of the T on the first floor. Those who served long-term convictions or hard labor punishment were assigned on the two sides of the T tail – first floor; those targeted for ''prison camps'' were assigned to the ground floor, ''

The prison was T-shaped, and the prisoners were detained based on the conviction type: ''light offences'' (''correction'') was set up on the head of the T on the first floor. Those who served long-term convictions or hard labor punishment were assigned on the two sides of the T tail – first floor; those targeted for ''prison camps'' were assigned to the ground floor, ''

communist regime

A communist state, also known as a Marxist–Leninist state, is a one-party state in which the totality of the power belongs to a party adhering to some form of Marxism–Leninism, a branch of the communist ideology. Marxism–Leninism was ...

at the end of World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

that targeted people who were considered hostile to the Romanian Communist Party

The Romanian Communist Party ( ; PCR) was a communist party in Romania. The successor to the pro-Bolshevik wing of the Socialist Party of Romania, it gave an ideological endorsement to a communist revolution that would replace the social system ...

, primarily members of the fascist

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural soci ...

Iron Guard

The Iron Guard () was a Romanian militant revolutionary nationalism, revolutionary Clerical fascism, religious fascist Political movement, movement and political party founded in 1927 by Corneliu Zelea Codreanu as the Legion of the Archangel M ...

, as well as other political prisoner

A political prisoner is someone imprisoned for their political activity. The political offense is not always the official reason for the prisoner's detention.

There is no internationally recognized legal definition of the concept, although ...

s, both from established prisons and from labor camp

A labor camp (or labour camp, see British and American spelling differences, spelling differences) or work camp is a detention facility where inmates are unfree labour, forced to engage in penal labor as a form of punishment. Labor camps have ...

s. The purpose of the process was the indoctrination

Indoctrination is the process of inculcating (teaching by repeated instruction) a person or people into an ideology, often avoiding critical analysis. It can refer to a general process of socialization. The term often implies forms of brainwas ...

of the hostile elements with the Marxist–Leninist ideology, that would lead to the crushing of any active or passive resistance movement

A resistance movement is an organized group of people that tries to resist or try to overthrow a government or an occupying power, causing disruption and unrest in civil order and stability. Such a movement may seek to achieve its goals through ei ...

. Reeducation was either non-violent – e.g., via communist propaganda

Communist propaganda is the artistic and social promotion of the ideology of communism, communist worldview, communist society, and interests of the communist movement. While it tends to carry a negative connotation in the Western world, the te ...

– or violent, as it was done at the Pitești

Pitești () is a city in Romania, located on the river Argeș (river), Argeș. The capital and largest city of Argeș County, it is an important commercial and industrial center, as well as the home of two universities. Pitești is situated in th ...

and Gherla

Gherla (; ; ) is a municipality in Cluj County, Romania (in the historical region of Transylvania). It is located from Cluj-Napoca on the river Someșul Mic, and has a population of 19,873 as of 2021. Three villages are administered by the city: ...

prisons.

Theoretical background

Philosopher Mircea Stănescu claimed that the theoretical foundation for the communist version of the reeducation process was provided by the principles defined by Anton Semioniovici Makarenko, aRussia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

n educator born in Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

in 1888. This claim was disputed by historian Mihai Demetriade, who indicated that there is "no link or resemblance, neither structural nor causal with the works of the psychologist and educator Makarenko". Demetriade further indicated that the claim is mainly associated with the groups around the fascist Iron Guard

The Iron Guard () was a Romanian militant revolutionary nationalism, revolutionary Clerical fascism, religious fascist Political movement, movement and political party founded in 1927 by Corneliu Zelea Codreanu as the Legion of the Archangel M ...

, and had been publicly promoted by anti-communist activist Virgil Ierunca

Virgil Ierunca (; born Virgil Untaru ; August 16, 1920, Lădești, Vâlcea County – September 28, 2006, Paris) was a Romanian literary critic, journalist, and poet. He was married to Monica Lovinescu.

Both Ierunca and Lovinescu worked for sev ...

.

Mircea Stănescu also asserted that another important factor was the definition of morality

Morality () is the categorization of intentions, Decision-making, decisions and Social actions, actions into those that are ''proper'', or ''right'', and those that are ''improper'', or ''wrong''. Morality can be a body of standards or principle ...

itself and that Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

had reportedly stated any action that seeks the welfare of the party is considered moral, while any action that harms it is immoral. As such, moral itself is a relative concept, it follows the needs of the group. A certain attitude shall be regarded as moral at a given time, while immoral at another moment; in order to decide, the person must respect the program as defined by the collective (the party).

Mihai Demetriade observed that violence within Iron Guard groups was rather common, both in public (such as the ritual murder of Mihai Stelescu), as well as in camps where many were imprisoned after the 1941 Legionnaires' rebellion and Bucharest pogrom. A notable case was the group of Iron Guard members interned in Rostock

Rostock (; Polabian language, Polabian: ''Roztoc''), officially the Hanseatic and University City of Rostock (), is the largest city in the German States of Germany, state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern and lies in the Mecklenburgian part of the sta ...

after the failed rebellion: a suspected traitor was severely tortured by its colleagues, the process being very similar to the one applied later in Pitești and Suceava. Demetriade concludes that torture and violence was part of the "Guardist anatomy" and "the prison administration created a favourable context for it to develop".

Context

In March 1949, the Operational Service (OS) was constituted, this being the first designation of prison security (''securitate''), on the initiative ofGheorghe Pintilie

Gheorghe Pintilie (born Panteley Timofiy Bodnarenko, ; also rendered as Pintilie Bodnarenco, nicknamed Pantiușa; November 9, 1902 – August 21, 1985) was a Soviet and Romanian intelligence agent and political assassin, who served as first head o ...

, head of the Securitate

The Department of State Security (), commonly known as the Securitate (, ), was the secret police agency of the Socialist Republic of Romania. It was founded on 30 August 1948 from the '' Siguranța'' with help and direction from the Soviet MG ...

. Its first commander was Iosif Nemeș. The Operational Service was subordinated to the Securitate, and not to the General Penitentiary Directorate (GPD). The GPD was handling the administrative responsibilities, under direct watch of the Securitate, while the OS was responsible with gathering intelligence from the political prisoners. After the entire intelligence structure was completed, the information flow was as follows: once retrieved from the informant

An informant (also called an informer or, as a slang term, a "snitch", "rat", "canary", "stool pigeon", "stoolie", "tout" or "grass", among other terms) is a person who provides privileged information, or (usually damaging) information inten ...

s, it reached the political officer of the incarceration unit, who personally handed them to the head of the OS. The data were analyzed and the summary, together with the original files, were handed over to the Securitate.

After the installment of the communist regime, the prison system went through a transition period. Up to 1947, the detention regime was rather light, as the political prisoners were entitled to receive home packages, books, were granted access to discuss with family and even organize cultural events. Gradually, the Securitate harshened the conditions, as the entire mechanism grew more solid. The old guards were replaced with new ones, adapted to the new society, the detention regime got rougher, beatings and torture

Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a person for reasons including corporal punishment, punishment, forced confession, extracting a confession, interrogational torture, interrogation for information, or intimid ...

during inquiry became common practice, together with mock trial

A mock trial is an act or imitation trial. It is similar to a moot court, but mock trials simulate lower-court trials, while moot court simulates appellate court hearings. Attorneys preparing for a real trial might use a mock trial consisti ...

s.

At first, the main target during the investigation were members of the Iron Guard

The Iron Guard () was a Romanian militant revolutionary nationalism, revolutionary Clerical fascism, religious fascist Political movement, movement and political party founded in 1927 by Corneliu Zelea Codreanu as the Legion of the Archangel M ...

and of former historical parties. Later, they were joined by those who opposed collectivization, who tried to illegally cross the border, members of resistance and, generally, opposers of the regime, even in nonviolent ways. Mircea Stănescu asserts that the communist regime did not consider imprisonment as a form of penitence, but a method of elimination from the social and political life, and, eventually, as a political reeducation environment.

Detention centers

The main detention centers dedicated to the re-education of political prisoners in Communist Romania were atSuceava

Suceava () is a Municipiu, city in northeastern Romania. The seat of Suceava County, it is situated in the Historical regions of Romania, historical regions of Bukovina and Western Moldavia, Moldavia, northeastern Romania. It is the largest urban ...

, Pitești

Pitești () is a city in Romania, located on the river Argeș (river), Argeș. The capital and largest city of Argeș County, it is an important commercial and industrial center, as well as the home of two universities. Pitești is situated in th ...

, Gherla

Gherla (; ; ) is a municipality in Cluj County, Romania (in the historical region of Transylvania). It is located from Cluj-Napoca on the river Someșul Mic, and has a population of 19,873 as of 2021. Three villages are administered by the city: ...

, Târgu Ocna

Târgu Ocna (; ) is a town in Bacău County, Romania.

It administers two villages, Poieni and Vâlcele.

The town is situated on the left bank of the Trotuș River, an affluent of the Siret, and on a branch railway which crosses the Ghimeș Pa ...

, Târgșor

Târgșor is a former medieval market town in what is now Prahova County, Romania. The town peaked around 1600, after which it declined to become the village of Târgșoru Vechi, located about southwest of Ploiești.

History

Built in a heavily ...

, Brașov

Brașov (, , ; , also ''Brasau''; ; ; Transylvanian Saxon dialect, Transylvanian Saxon: ''Kruhnen'') is a city in Transylvania, Romania and the county seat (i.e. administrative centre) of Brașov County.

According to the 2021 Romanian census, ...

, Ocnele Mari

Ocnele Mari is a town located in Vâlcea County, Oltenia, Romania. The town administers eight villages: Buda, Cosota, Făcăi, Gura Suhașului, Lunca, Ocnița, Slătioarele, and Țeica.

The town is situated in the central part of the county, at ...

, and Peninsula

A peninsula is a landform that extends from a mainland and is only connected to land on one side. Peninsulas exist on each continent. The largest peninsula in the world is the Arabian Peninsula.

Etymology

The word ''peninsula'' derives , . T ...

. These re-education penitentiaries were characterized by the application of torture methods in order to convert the detainees to the communist ideology.

Suceava

Suceava

Suceava () is a Municipiu, city in northeastern Romania. The seat of Suceava County, it is situated in the Historical regions of Romania, historical regions of Bukovina and Western Moldavia, Moldavia, northeastern Romania. It is the largest urban ...

prison was a detention place for Iron Guard members located in northern and central Moldavia

Moldavia (, or ; in Romanian Cyrillic alphabet, Romanian Cyrillic: or ) is a historical region and former principality in Eastern Europe, corresponding to the territory between the Eastern Carpathians and the Dniester River. An initially in ...

, many of whom arrived here following the massive arrests from the night of 14–15 May 1948. From within the prisoners group, the first to approach the reeducation concept were Alexandru Bogdanovici and Eugen Țurcanu. Bogdanovici had a long history of legionnaire activity: first arrested in 1943; he was sentenced to 6 years correctional detention; the second sentence – three years – was received in 1945, for taking part in the Ciucaș Mountains

The Ciucaș Mountains (, ) is a mountain range in Romania. It is located in the northern part of Prahova County and straddles the border with Brașov County

Brașov County () is a county (județ) of Transylvania, Romania. Its capital city is ...

resistance. On his last arrest, in 1948, he was practically leader of the Iron Guard Student Community in Iași

Iași ( , , ; also known by other #Etymology and names, alternative names), also referred to mostly historically as Jassy ( , ), is the Cities in Romania, third largest city in Romania and the seat of Iași County. Located in the historical ...

. Eugen Țurcanu was arrested on 3 July 1948, after he was reported taking part to Iron Guard meetings and as a member of the Câmpulung Moldovenesc

Câmpulung Moldovenesc (; formerly spelled ''Cîmpulung Moldovenesc'') is a municipiu, city in Suceava County, northeastern Romania. It is situated in the historical region of Bukovina.

Câmpulung Moldovenesc is the fourth largest urban settleme ...

Iron Guard Brotherhood (FDC 36 Câmpulung).

Although at this time the inquiries of the ''Siguranța

''Siguranța'' was the generic name for the successive secret police services in the Kingdom of Romania. The official title of the organization changed throughout its history, with names including Directorate of the Police and General Safety () ...

'' (acting as political police

300px, East_German.html" ;"title="Vladimir Putin's secret police identity card, issued by the East German">Vladimir Putin's secret police identity card, issued by the East German Stasi while he was working as a Soviet KGB liaison officer from 19 ...

and soon to be reorganized into the Department of State Security after the NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (, ), abbreviated as NKVD (; ), was the interior ministry and secret police of the Soviet Union from 1934 to 1946. The agency was formed to succeed the Joint State Political Directorate (OGPU) se ...

model) were already violent in nature, the Suceava reeducation process itself began as non-violent. Initiated by Bogdanovici in October 1948, it consisted of: communist propaganda among Iron Guard prisoners, anti-Iron Guard propaganda, papers based on the historical materialism theses, lectures from works by Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

and the history of the Soviet Union, creation of poetry and songs with communist undertone. Țurcanu even created an Organization for Detainees with Communist Beliefs (ODCB), whose structure was modeled based on the Communist Party, and all the supporters of the reeducation were registered. Finally, the process extended through the prison, every cell containing its own ''reeducation committee'', responsible for the action coordination.

Aside from Bogdanovici and Țurcanu, of those that initiated the action at Suceava and became more involved in other prisons, several stood out: Constantin Bogoș, Virgil Bordeianu, Alexandru Popa, Mihai Livinschi, Maximilian Sobolevski, Vasile Pușcașu, Dan Dumitrescu, and Nicolae Cobâlaș. The motivations behind these ex-legionnaires switching sides were varied, but generally included the hope of getting a lesser punishment after the initial "generous" retribution and obtaining several amenities while incarcerated (packages from home, mail, etc.) Up to 100 prisoners joined the reeducation plan by April 1949.

Pitești

Starting with September–October 1948,Pitești Prison

Pitești Prison () was a penal facility in Pitești, Romania, best remembered for the reeducation experiment (also known as ''Experimentul Pitești'' – the "Pitești Experiment" or ''Fenomenul Pitești'' – the "Pitești Phenomenon") which wa ...

was designated as a detention facility for students who were members of the Iron Guard (legionnaires). The prison warden was Alexandru Dumitrescu. Following the reorganization of the Securitate and the creation of the Operational Service, to each prison an Operational Bureau was designated. The first political officer assigned to Pitești was Ion Marina.

solitary

Solitary is the state of being alone or in solitude. The term may refer to:

* ''Solitary'' (album), 2008 album by Don Dokken

* ''Solitary'' (2020 film), a British sci-fi thriller film

* ''Solitary'' (upcoming film), an American drama film

* "S ...

("casimca"), a small isolation cell, without light of ventilation, extremely cold in winter, while the floor was flooded with water and urine

Urine is a liquid by-product of metabolism in humans and many other animals. In placental mammals, urine flows from the Kidney (vertebrates), kidneys through the ureters to the urinary bladder and exits the urethra through the penile meatus (mal ...

. As the program progressed, exterior walls were built around the prison, and within the penitentiary perimeter, the inside and outside yards, so far separated by barbed wire

Roll of modern agricultural barbed wire

Barbed wire, also known as barb wire or bob wire (in the Southern and Southwestern United States), is a type of steel fencing wire constructed with sharp edges or points arranged at intervals along the ...

fences, were now completely isolated by concrete walls.

Violent reeducation began on 25 November 1949, in ''cell 1 correction'', on the initiative of a group led by Țurcanu. The reeducation ensemble and torture methods were perfected in time, but the process itself did not change. At first, two groups were moved into the same room: the reeducation device (shock group) and the target group. Apportionment of detainees inside the prison cells was done based on the political officer's indications.

Prior to this assembly, through the prisons informant network (of which the reeducation ensemble was part of), compromising data was gathered on the victims, such as Legionnaire membership, information they hid during the inquiry, anti-communist activity not declared etc. After a relative calm exploratory period, during which the target group members were questioned concerning their attitude towards the iron-guard movement and communist party, they were asked to unmask themselves and adhere to the reeducation movement, violence and torture followed. The violent stage was Makarenko's explosion, and was done collectively.

Beating were ferocious, inmates were clubbed or trampled unconscious, many times unrecognizable after the violent treatment.

Tortures were varied; if initially the sole purpose was to ''humiliate the prisoners'', who were forced to wear the toilet bucket on their head, crawl on the floor or eat without using their hands, later it followed to reach an ''extensive physical wear'', which made them more susceptible to crack: they went for days without water, were forced to stay in uneasy positions such as lying down with the head raised and a needle pointing back of the neck or to remove and put back their shoe laces for hours on end; for the resistant ones, a ''total mental breakdown'' was attempted, as they were made to eat

Beating were ferocious, inmates were clubbed or trampled unconscious, many times unrecognizable after the violent treatment.

Tortures were varied; if initially the sole purpose was to ''humiliate the prisoners'', who were forced to wear the toilet bucket on their head, crawl on the floor or eat without using their hands, later it followed to reach an ''extensive physical wear'', which made them more susceptible to crack: they went for days without water, were forced to stay in uneasy positions such as lying down with the head raised and a needle pointing back of the neck or to remove and put back their shoe laces for hours on end; for the resistant ones, a ''total mental breakdown'' was attempted, as they were made to eat feces

Feces (also known as faeces American and British English spelling differences#ae and oe, or fæces; : faex) are the solid or semi-solid remains of food that was not digested in the small intestine, and has been broken down by bacteria in the ...

, behave as pigs when food was provided (eat without cutlery and grunt), walk on all fours in circle, each licking the anus of the one in front or behave in obscene and perverted ways during mock religious services.

According to Virgil Ierunca

Virgil Ierunca (; born Virgil Untaru ; August 16, 1920, Lădești, Vâlcea County – September 28, 2006, Paris) was a Romanian literary critic, journalist, and poet. He was married to Monica Lovinescu.

Both Ierunca and Lovinescu worked for sev ...

, Christian baptism was gruesomely mocked. Guards chanted baptismal rites as buckets of urine and fecal matter were brought to inmates. The inmate's head was pushed into the raw sewage. His head would remain submerged almost to the point of death. The head was then raised, the inmate allowed to breathe, only to have his head pushed back into the sewage.

Ierunca further states that "prisoners' whole bodies were burned with cigarettes; their buttocks would begin to rot, and their skin fell off as though they suffered from leprosy. Others were forced to swallow spoons of excrement, and when they threw it back up, they were forced to eat their own vomit.

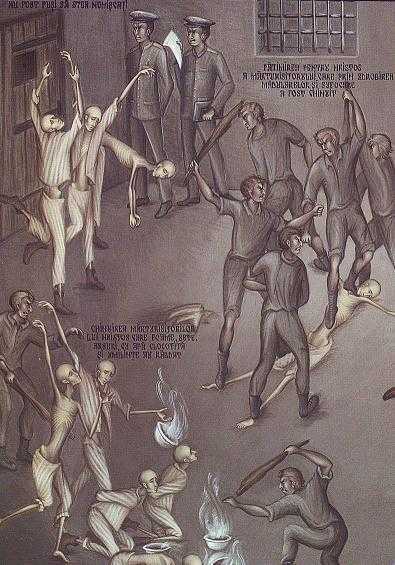

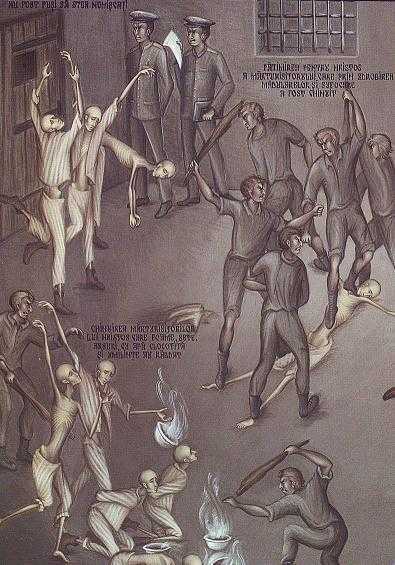

During the ''shock'', after beatings and humiliation

Humiliation is the abasement of pride, which creates mortification or leads to a state of being Humility, humbled or reduced to lowliness or submission. It is an emotion felt by a person whose social status, either by force or willingly, has ...

, often exercised from those initially considered as friends, detainees were subjected to another disillusion: the administration showed no support whatsoever. Guards frequently took part on the beatings, the wounded received only limited medical care, in the cell, not at the infirmary

Infirmary may refer to:

*Historically, a hospital, especially a small hospital

*A first aid room in a school, prison, or other institution

*A dispensary (an office that dispenses medications)

*A clinic

A clinic (or outpatient clinic or ambul ...

, and only if they accepted to unmask ( denounce) themselves. Frequent inspections found the prisoners severely beaten up, but treated the subject with sarcasm, serving as proof that the events were known to authorities and accepted as such. This way, inmates were notified that they should not expect any help whatsoever, from within or outside the prison walls. Systematic torture continued until the subjects unmasked themselves.

The unmasking process consisted of several phases.

First came the external unmasking: the detainee had to confess all his actions that were hostile towards the regime. This phase itself was split into two stages.

* The inside exposure: the person was forced to reveal all the activities aimed against the penitentiary regime and administration, since incarceration. The purpose was to expose all subversive activities and also verify the "correctness" of the prisoner. The process was done in public, under the surveillance of the reeducator, and prisoners had to be actively involved and ask questions in turn.

* The outside exposure: detainees had to reveal their hostile behavior prior to the arrest, especially the actions that may have harmed the interest of the communist party: subversive organizations (the resistance), the activity of the historical parties after their dissolution, acts aimed against the party members during the war, espionage, etc.

The second phase represented the internal unmasking, where an autobiography

An autobiography, sometimes informally called an autobio, is a self-written account of one's own life, providing a personal narrative that reflects on the author's experiences, memories, and insights. This genre allows individuals to share thei ...

was requested from the inmates; the degree of defamation

Defamation is a communication that injures a third party's reputation and causes a legally redressable injury. The precise legal definition of defamation varies from country to country. It is not necessarily restricted to making assertions ...

it contained was considered directly proportional to the mental shift of the prisoner towards the reeducation program. They had to present their family members as immoral, criminals and incest

Incest ( ) is sexual intercourse, sex between kinship, close relatives, for example a brother, sister, or parent. This typically includes sexual activity between people in consanguinity (blood relations), and sometimes those related by lineag ...

uous, in public. The anti-regime actions that had them imprisoned were as such presented as being caused by the depraved environment they were educated in.

The third and last phase was the post-unmasking, and it consisted in discussions concerning communist doctrine and practice. While during the first and second phase, the person had to prove the past was left behind and his loyalty stands with the party, the purpose of the third phase was to strengthen the theoretical foundation of this process.

The prisoners who unmasked themselves were enlisted in the reeducation mechanism and forced to beat up/torture on others. Occasionally, they were forced to go through the procedure again: either it was revealed that they did not confess everything or it was considered that they did not "hit strong enough". Țurcanu was the leader of the reeducation group, he decided on site if the prisoners were honest, he delegated the reeducation committees and assigned them to prison cells, was actively engaged in the ongoing violence and the detainees had to confess everything in his presence.

quarantine

A quarantine is a restriction on the movement of people, animals, and goods which is intended to prevent the spread of disease or pests. It is often used in connection to disease and illness, preventing the movement of those who may have bee ...

'' was set up in the basement while those in ''administrative detention

Administrative detention is arrest and detention of individuals by the state without trial. A number of jurisdictions claim that it is done for security reasons. Many countries claim to use administrative detention as a means to combat terrorism ...

'' – people on whom crime evidence was not strong enough to stand trial. The reeducation process, started in cell ''1 correction'', was later moved to room ''4 hospital'' – the largest room, it could accommodate over 60 people – this being the main reeducation facility. In time, it will expand to both long term conviction or hard labor punishment sections.

Not able to resist the mental and physical violence, some prisoners tried to commit suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death.

Risk factors for suicide include mental disorders, physical disorders, and substance abuse. Some suicides are impulsive acts driven by stress (such as from financial or ac ...

, by severing their veins. Gheorghe Șerban and Gheorghe Vătășoiu committed suicide by throwing themselves through the opening between the stairways, before safety nets were installed. Many died following the wounds

A wound is any disruption of or damage to living tissue, such as skin, mucous membranes, or organs. Wounds can either be the sudden result of direct trauma (mechanical, thermal, chemical), or can develop slowly over time due to underlying diseas ...

from beatings and tortures. Alexandru Bogdanovici, one of the initiators of the reeducation process at Suceava, was continuously tortured until his death on 15 April 1950, mainly because he was considered to be an opportunist, only seeking a way to get out of detention.

Beginning with 1950, the Operational Service was reorganized, with Tudor Sepeanu replacing Iosif Nemeș. One consequence of this move was that the Pitești political officer, Ion Marina, was replaced by Mihai Mircea. In February 1951, Sepeanu will be in turn replaced by Alexandru Roșianu. These changes will have no consequences on the detention regime, as the reeducation continued halfway in 1951. Within this period, many prisoners that underwent the reeducation process were transferred to other detention centers. The negative publicity surrounding this activity, the official inquiry of July 1951, led by colonel Ludovic Czeller, head of the Administrative Control Body of the DGP, following which most of the Pitești prison staff was dismissed or transferred (warden Alexandru Dumitrescu was replaced by Anton Kovacs) and the relocation of all the Pitești political prisoners to Gherla on 29 August 1951, led to the termination of violent reeducation in this location.

The death toll of the Pitești reeducation: 22 dead and over one thousand physically and mentally mutilated

Mutilation or maiming (from the ) is severe damage to the body that has a subsequent harmful effect on an individual's quality of life.

In the modern era, the term has an overwhelmingly negative connotation, referring to alterations that rend ...

prisoners.

Târgșor

Târgșor Prison was converted to a ''pupils'' detention center in 1948. Prior to this, it had been amilitary prison

A military prison is a prison operated by a military. Military prisons are used variously to house prisoners of war, unlawful combatants, those whose freedom is deemed a national security risk by the military or national authorities, and members o ...

since 1882. It was divided in two sections, one for the pupils, the other for former policemen

A police officer (also called policeman or policewoman, cop, officer or constable) is a warranted law employee of a police force. In most countries, ''police officer'' is a generic term not specifying a particular rank. In some, the use of t ...

and Siguranța members. The first section was reserved for those aged 16–20 years. Initially, the detention conditions were rather light, as they were allowed to receive packages (including books) and money, while once per month a guard was responsible for setting up a shopping list based on the prisoners demands. Food was decent while the prison administration – headed by warden Spirea Dumitrescu – was supportive towards them.

After the prison reorganization, a weaving

Weaving is a method of textile production in which two distinct sets of yarns or threads are interlaced at right angles to form a fabric or cloth. Other methods are knitting, crocheting, felting, and braiding or plaiting. The longitudinal ...

workshop is built, with the purpose of serving as a work reeducation center. Additionally, the administration started lectures based on the works of Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

and Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ;"Engels"

''

''

In time, the incarceration conditions deteriorated, reaching the same level as the other

The most important informants used by the administration – prisoners who would play a key role in the reeducation process at Gherla, but who did not undergo the full Pitești ordeal – were Alexandru Matei, Octavian Grama, Constantin P. Ionescu, and Cristian Paul Șerbănescu. The first Pitești group – counting 70–80 reeducated detainees – arrived on 7 June 1950. This group contained some of the prisoners that were active at Pitești and were as such recommended for the Gherla proceedings: Alexandru Popa, Vasile Pușcașu, Constantin Bogoș, Vasile Andronache, and Mihai Livinschi. They would form the core of the Gherla reeducation activity.

Before triggering the events, several changes were made following Securitate directives: Iacob was replaced by Gheorghe Sucigan as head of the prison Operational Bureau (OB), and Constantin Pruteanu was appointed as his deputy. Later, Pruteanu was replaced by Constantin Avădani, and warden Lazăr was replaced by captain Constantin Gheorghiu. Although brutal in his relations with the prisoners, Lazăr was a straightforward opponent of violent reeducation, and asked Tudor Sepeanu a written directive regarding this initiative, which led to his dismissal. Meanwhile, with the help of the prisoners transferred from Pitești and the local informant group, the OB build up a strong informant network, controlling all the prison key positions, from workshop leaders to the penitentiary

The most important informants used by the administration – prisoners who would play a key role in the reeducation process at Gherla, but who did not undergo the full Pitești ordeal – were Alexandru Matei, Octavian Grama, Constantin P. Ionescu, and Cristian Paul Șerbănescu. The first Pitești group – counting 70–80 reeducated detainees – arrived on 7 June 1950. This group contained some of the prisoners that were active at Pitești and were as such recommended for the Gherla proceedings: Alexandru Popa, Vasile Pușcașu, Constantin Bogoș, Vasile Andronache, and Mihai Livinschi. They would form the core of the Gherla reeducation activity.

Before triggering the events, several changes were made following Securitate directives: Iacob was replaced by Gheorghe Sucigan as head of the prison Operational Bureau (OB), and Constantin Pruteanu was appointed as his deputy. Later, Pruteanu was replaced by Constantin Avădani, and warden Lazăr was replaced by captain Constantin Gheorghiu. Although brutal in his relations with the prisoners, Lazăr was a straightforward opponent of violent reeducation, and asked Tudor Sepeanu a written directive regarding this initiative, which led to his dismissal. Meanwhile, with the help of the prisoners transferred from Pitești and the local informant group, the OB build up a strong informant network, controlling all the prison key positions, from workshop leaders to the penitentiary  Tortures varied: detainees were forced to stay in uncomfortable positions ("meditation position") for long periods of time, sometimes for days on end, sitting up with hands extended, forced to eat hot food without a spoon; they had to drink salty water or made to eat feces or vomit and drink urine. During summer, some were kept with

Tortures varied: detainees were forced to stay in uncomfortable positions ("meditation position") for long periods of time, sometimes for days on end, sitting up with hands extended, forced to eat hot food without a spoon; they had to drink salty water or made to eat feces or vomit and drink urine. During summer, some were kept with

Work on the

Work on the  Peninsula labor camp was set up in June 1950, away from Poarta Albă, on the shore of

Peninsula labor camp was set up in June 1950, away from Poarta Albă, on the shore of

Memorial of Sorrow – Episode 11 – The Pitești Experiment

The Pitești phenomenon

* *

Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

n political prisons.

A group of approximately 100 detainees was transferred there from Suceava in August 1949. Of those, more than half already joined the reeducation process. They set up a ''Reeducation Committee'' and approached the administration, seeking both support in their actions and retaliation against those who opposed it. By March 1950, they gained control over all the prison key positions, from the storehouse and workshop to the kitchen and post office. A political officer is assigned here, Iancu Burada at first, Dumitru Antonescu later. Joining the reeducation was optional, but came with a series of advantages, while those hostile were either isolated or eliminated from privileged jobs. An organization – named ''23 August'' – is created in a similar structure to the Suceava ODCB, soon counting between 70 – 120 members. Reeducation activities were non-violent, such as reading articles from Scânteia or public readings from communist works.

In July–August 1950, following an inspection from officers of the Securitate and Minister of Internal Affairs

An interior minister (sometimes called a minister of internal affairs or minister of home affairs) is a cabinet official position that is responsible for internal affairs, such as public security, civil registration and identification, emergency ...

, warden Dumitrescu is replaced by captain Valeriu Negulescu, characterized as a "savage beast". The prison section reserved for former police officers is moved to Făgăraș

Făgăraș (; , ) is a municipiu, city in central Romania, located in Brașov County. It lies on the Olt (river), Olt River and has a population of 26,284 as of 2021. It is situated in the historical region of Transylvania, and is the main city of ...

while the incarceration conditions get worse. Books and personal possessions are confiscated, overcoats and gloves were turned in to prevent escapes, daily strolls are seized and food quality diminishes. The new regime – educated at Jilava

Jilava is a commune in Ilfov County, Muntenia, Romania, near Bucharest. It is composed of a single village, Jilava.

The name derives from a Romanian word of Slavic origin ( Bulgarian жилав ''žilav'' (tough), which passed into Romanian as ...

prison – made no distinction between reeducation followers and opponents, and beatings started.

Such a behavior is displayed after the escape of Ion Lupeș – November 1950 – when the warden aggressed the inmates:

The prison is gradually emptied between October and 20 December 1950. The prisoners were assigned either to the Danube-Black Sea Canal or to Gherla, and some were even set free. Unlike Pitești, the Târgșor reeducation process itself was not violent, for several reasons: being young, the prisoners were not considered as having important information regarding the communist resistance, the reeducation action was not supported by the administration from the start and the prison structure (three interconnected detention dormitories) did not allow for the prisoners to be isolated in small groups.

Gherla

At the time when the first reeducated prisoners from Pitești were transferred in 1950 toGherla Prison

Gherla Prison is a penitentiary located in the Romanian city of Gherla (), in Cluj County. The prison dates from 1785; it is infamous for the treatment of its political inmates, especially during the Communist regime. In Romanian slang, the generi ...

, the penitentiary held approximately 1,500 people. Following the detention allocation regulations, ''workers'' and ''peasant

A peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer with limited land-ownership, especially one living in the Middle Ages under feudalism and paying rent, tax, fees, or services to a landlord. In Europe, three classes of peasan ...

s'' were imprisoned here, and two work sections were created: a metallurgical

Metallurgy is a domain of materials science and engineering that studies the physical and chemical behavior of metallic elements, their inter-metallic compounds, and their mixtures, which are known as alloys.

Metallurgy encompasses both the ...

one and a woodwork

Woodworking is the skill of making items from wood, and includes cabinetry, furniture making, wood carving, joinery, carpentry, and woodturning.

History

Along with stone, clay and animal parts, wood was one of the first materials worked by ...

factory, each with several workshops. After the reeducation initial success at Pitești, the regime intended to spread the practice to other prisons as well, and due to ideological reasons – as workers and peasant were the forefront of the communist propaganda – Gherla was amongst the first detention places to implement it. The warden wasstarting with 1949Tiberiu Lazăr, born in Budapest of Jewish origins, whose parents, first wife, and one child had been murdered at Auschwitz

Auschwitz, or Oświęcim, was a complex of over 40 concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland (in a portion annexed into Germany in 1939) during World War II and the Holocaust. It consisted of Auschw ...

. Appointed since spring 1949, Dezideriu Iacob was the political officer. While Lazăr was in charge, beatings were common practice. For example, on the second day of Easter

Easter, also called Pascha ( Aramaic: פַּסְחָא , ''paskha''; Greek: πάσχα, ''páskha'') or Resurrection Sunday, is a Christian festival and cultural holiday commemorating the resurrection of Jesus from the dead, described in t ...

1950, he set up a general beating of over 100 detainees, in the prison yard.

The most important informants used by the administration – prisoners who would play a key role in the reeducation process at Gherla, but who did not undergo the full Pitești ordeal – were Alexandru Matei, Octavian Grama, Constantin P. Ionescu, and Cristian Paul Șerbănescu. The first Pitești group – counting 70–80 reeducated detainees – arrived on 7 June 1950. This group contained some of the prisoners that were active at Pitești and were as such recommended for the Gherla proceedings: Alexandru Popa, Vasile Pușcașu, Constantin Bogoș, Vasile Andronache, and Mihai Livinschi. They would form the core of the Gherla reeducation activity.

Before triggering the events, several changes were made following Securitate directives: Iacob was replaced by Gheorghe Sucigan as head of the prison Operational Bureau (OB), and Constantin Pruteanu was appointed as his deputy. Later, Pruteanu was replaced by Constantin Avădani, and warden Lazăr was replaced by captain Constantin Gheorghiu. Although brutal in his relations with the prisoners, Lazăr was a straightforward opponent of violent reeducation, and asked Tudor Sepeanu a written directive regarding this initiative, which led to his dismissal. Meanwhile, with the help of the prisoners transferred from Pitești and the local informant group, the OB build up a strong informant network, controlling all the prison key positions, from workshop leaders to the penitentiary

The most important informants used by the administration – prisoners who would play a key role in the reeducation process at Gherla, but who did not undergo the full Pitești ordeal – were Alexandru Matei, Octavian Grama, Constantin P. Ionescu, and Cristian Paul Șerbănescu. The first Pitești group – counting 70–80 reeducated detainees – arrived on 7 June 1950. This group contained some of the prisoners that were active at Pitești and were as such recommended for the Gherla proceedings: Alexandru Popa, Vasile Pușcașu, Constantin Bogoș, Vasile Andronache, and Mihai Livinschi. They would form the core of the Gherla reeducation activity.

Before triggering the events, several changes were made following Securitate directives: Iacob was replaced by Gheorghe Sucigan as head of the prison Operational Bureau (OB), and Constantin Pruteanu was appointed as his deputy. Later, Pruteanu was replaced by Constantin Avădani, and warden Lazăr was replaced by captain Constantin Gheorghiu. Although brutal in his relations with the prisoners, Lazăr was a straightforward opponent of violent reeducation, and asked Tudor Sepeanu a written directive regarding this initiative, which led to his dismissal. Meanwhile, with the help of the prisoners transferred from Pitești and the local informant group, the OB build up a strong informant network, controlling all the prison key positions, from workshop leaders to the penitentiary hospital

A hospital is a healthcare institution providing patient treatment with specialized Medical Science, health science and auxiliary healthcare staff and medical equipment. The best-known type of hospital is the general hospital, which typically ...

. End of September 1950, Sucigan came back from Bucharest carrying the order to start the unmasking process. This was already tested in solitary room 96, its victims being Ion Bolocan and Virgil Finghiș. The proceedings were identical to the Pitești ones: the leader of the informant network selected and grouped the targeted prisoners, and at the same time defined the informants that would infiltrate these groups. The guards made the repartitions based on direct indications from the OB. Following this, a pro-legionnaire environment was maintained in order to strengthen the relations between prisoners. Then came the ''shock'': members of the Iron Guard were asked to unmask themselves. Those who opposed were beaten and tortured until they gave in. Doctor Viorel Bărbos and assistant Vasile Mocodeanu – helped by other inmates from the medical team – were the only ones with access to the victims, for treating the wounds. Moving them to the prison hospital was done only if approved by the OB. The denouncements were written down in front of leaders of the reeducation committee, on pieces of soap or paper bags, then adjusted by the BO officers and only afterwards sent to Bucharest. Denouncements that were not confirmed on the field were sent back to prison for verification.

Tortures varied: detainees were forced to stay in uncomfortable positions ("meditation position") for long periods of time, sometimes for days on end, sitting up with hands extended, forced to eat hot food without a spoon; they had to drink salty water or made to eat feces or vomit and drink urine. During summer, some were kept with

Tortures varied: detainees were forced to stay in uncomfortable positions ("meditation position") for long periods of time, sometimes for days on end, sitting up with hands extended, forced to eat hot food without a spoon; they had to drink salty water or made to eat feces or vomit and drink urine. During summer, some were kept with goggles

Goggles, or safety glasses, are forms of protective eyewear that usually enclose or protect the area surrounding the eye in order to prevent particulates, water or chemicals from striking the eyes. They are used in chemistry laboratories and ...

over their eyes, wearing thick clothes and carrying heavy luggage, without water. Some tortures were only meant to humiliate, like having to blow into the light bulb to put it out; some were painted over their faces and made to dance for mockery.

Chirică Gabor described his ordeal:

Before beatings, the prisoners were checked by the medical team, to avoid deaths for those that suffered from heart related diseases. Where deaths occurred, the doctor forged the diagnostics

Diagnosis (: diagnoses) is the identification of the nature and cause of a certain phenomenon. Diagnosis is used in a lot of different disciplines, with variations in the use of logic, analytics, and experience, to determine " cause and effect". ...

on the death certificate

A death certificate is either a legal document issued by a medical practitioner which states when a person died, or a document issued by a government civil registration office, that declares the date, location and cause of a person's death, a ...

, usually indicating diseases of which the detainee previously suffered. Suicide attempts occurred as well: some cut their veins with sharpened spoons, Ion Pangrate tried to slice his throat with glass from the cell window, even desperate attempts such as jumping head down on the cell floor or into the hot soup cauldron. In the Gherla penitentiary, violent reeducation was held at the third floor, ''room 99'' being the main denouncement center (the equivalent of room ''4 hospital'' from Pitești) while reeducation comities existed in several other prison cells.

A group of approximately 180 prisoners – led by Eugen Țurcanu – arrived at Gherla on 30 August 1950 and were incarcerated in cells 103–106. They will soon join the prison's informant network and reeducation apparatus. However, since meanwhile the Pitești reeducation secret had been revealed and several other problems occurred – such as deaths during the process itself – led to Avădani ordering a cessation of the action. In reality, they were not stopped, but only tempered. In response to this, Țurcanu conceived a ''Diversion and reeducation plan for Gherla prison'', whose purpose was to continue the unmasking process, by non-violent means. The plan had three phases:

* As for the usual process, the first stage was to facilitate the creation of a pro-Iron Guard group and boosting its morale.

* The second stage was to provoke the unmasking of the group in a public gathering, isolate the leaders and process them. Processing meant a confrontation of the leaders with the reeducated group, with the purpose of changing their political orientation.

* The third stage consisted in the indoctrination of the prisoners with Marxist doctrine via lecturing and conferences.

The plan was stopped in December 1951, at the beginning of the third stage.

Gherla reeducation continued until February 1952, when the last isolation rooms were dissolved. Between 500 and 1000 persons went through the process, approximately 20 died as a result of torture.

Danube–Black Sea Canal

Work on the

Work on the Danube–Black Sea Canal

The Danube–Black Sea Canal () is a navigable canal in Romania, which runs from Cernavodă on the Danube river, via two branches, to Constanța and Năvodari on the Black Sea. Administered from Agigea, it is an important part of the waterway li ...

started in summer 1949, following the route marked by the Black Valley, stretching across Northern Dobruja

Northern Dobruja ( or simply ; , ''Severna Dobrudzha'') is the part of Dobruja within the borders of Romania. It lies between the lower Danube, Danube River and the Black Sea, bordered in the south by Southern Dobruja, which is a part of Bulgaria.

...

from east toward west. The idea originated from a letter addressed by Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

to Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej

Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej (; 8 November 1901 – 19 March 1965) was a Romanian politician. He was the first Socialist Republic of Romania, Communist leader of Romania from 1947 to 1965, serving as first secretary of the Romanian Communist Party ...

in 1948, and its purpose was far more than just for economic reasons. First of all, it was meant to be a social engineering project, with the declared aim of creating new technical and political staff. The communist regime in Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ) is the capital and largest city of Romania. The metropolis stands on the River Dâmbovița (river), Dâmbovița in south-eastern Romania. Its population is officially estimated at 1.76 million residents within a greater Buc ...

could not finance such a massive undertaking; it was a politically driven project, meant to build up the " New Man", defined by the Marxist–Leninist doctrine.

On the other hand, this was meant to be the final destination for the old political and social elite. The political prisoners were forced to work under extremely harsh conditions, subjected to an extermination regime and targeted for the next stages of the reeducation process. While the emphasis was set more on work-driven reeducation rather than violence, the two functioned in parallel, and a great number of prisoners ended up in mass grave

A mass grave is a grave containing multiple human corpses, which may or may Unidentified decedent, not be identified prior to burial. The United Nations has defined a criminal mass grave as a burial site containing three or more victims of exec ...

s.

Twelve labor camps were set up alongside the canal route: Cernavodă

Cernavodă () is a town in Constanța County, Northern Dobruja, Romania with a population of 15,088 as of 2021.

The town's name is derived from the Bulgarian ''černa voda'' ( in Cyrillic), meaning 'black water'. This name is regarded by some s ...

(Columbia), Kilometer 4 (in Saligny), Kilometer 23, Kilometer 31 – Castelu (Castle), Poarta Albă (White Gate), Galeș (near Poarta Albă), 9 Culme (9 Ridge), Peninsula (near Valea Neagră), Năvodari

Năvodari (, historical names: ''Carachioi''; ''Caracoium'', ) is a town in Constanța County, region of Northern Dobruja, Romania, with a population of 34,398 as of 2021. The town formally includes a territorially distinct community, Social Grou ...

, Midia, Constanța

Constanța (, , ) is a city in the Dobruja Historical regions of Romania, historical region of Romania. A port city, it is the capital of Constanța County and the country's Cities in Romania, fourth largest city and principal port on the Black ...

Stadion, and Eforie Nord. Poarta Albă labor camp was the prisoner distribution center, as it was located halfway between the Danube

The Danube ( ; see also #Names and etymology, other names) is the List of rivers of Europe#Longest rivers, second-longest river in Europe, after the Volga in Russia. It flows through Central and Southeastern Europe, from the Black Forest sou ...

and the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

. As a general rule, those with sentences shorter than five years were kept there, while those with sentences above this threshold were sent to the Peninsula labor camp. According to the remaining documentation from the Constanța Regional Prosecutor's Fund, between 1949 and 1955 (the period when the vast majority of labor force was constituted of political prisoners), their number oscillated as following:

* 1949: 6,400 (1 September), 7,721 (1 October), and 6,422 (30 October).

* 1950: 5,382 (30 June), 5,772 (30 July), 6,400 (30 August), and 7,721 (30 September).

* 1951: 15,000 (6 June) and 15,609 (1 September).

* 1952: 11,552 (February), 14,809 (March), 14,919 (April), 17,150 (May), 17,837 (July), 22,442 (August), and 20,768 (September).

* 1953: 20,193 (April), 17,014 (June) and 14,244 (July).

Lake Siutghiol

Siutghiol () is a lagoon on the shores of the Black Sea, in Constanța County, Northern Dobruja, Romania. It has a length of and a width of ; it extends over and has a maximum depth of .

Ovidiu Island is a small island on the west side of the ...

, opposite to Mamaia

Mamaia () is a resort on the Romanian Black Sea shore and a district of Constanța.

Considered to be Romania's most popular resort, Mamaia is situated immediately north-east of Constanța's city center. It has almost no full-time residents, being ...

town. It consisted of several H-shaped, template shacks, made up of wooden frame and battens plastered with clay, then covered with tar paper

Tar paper, roofing paper, felt paper, underlayment, or roofing tar paper is a heavy-duty paper used in construction. Tar paper is made by impregnating paper with tar, producing a waterproof material useful for roof construction. Tar paper is ...

; the shack extremities were reserved as brigade bedrooms, while the transverse, close to the entrance, was used as lavatory. People slept on fir bunk beds, covered with mattresses filled with straws. The camp could accommodate a maximum number of 5,000 detainees. During its existence, several wardens succeeded in command: lieutenant Ion Ghinea, the first warden, followed by Dobrescu – November 1950, Ilie Zamfirescu – March 1951, Ștefan Georgescu – May 1951, Mihăilescu – November 1951, Tiberiu Lazăr, the former warden of Gherla prison – February/March 1952, Petre Burghișan – November 1952 and Eugen Cornățeanu – July 1953. The detention regime was very harsh. Generally, wake-up was at 5:00, while the program started around 6:00 or 7:00, depending on the distance from the labor camp to the work site. Lunch break lasted half an hour and work continued earliest till 15:30. The quantity and quality of the food varied. In the morning, a soup of roast barley ("the coffee") was served, alongside 250 grams of stiff, old, black bread. In the afternoon and evening, a tin of mashed barley or pickles soup accompanied the quarter bread. The food had such a low caloric content, that the prisoners had to supplement it in any possible way, even by eating captured snakes.

Peninsula consisted of six labor sites:

* The regular work site – ''Peninsula'' – in the proximity of the camp.

* ''Mamaia'', where the main task was loading/unloading mine carts with excavated gravel.

* ''Mustață'' ("mustache") work site, where gravel and rocks from other work sites were brought for filling up a valley, targeted for agriculture.

* ''Canara'' work site, where rock was excavated, broken down, crushed and loaded.

* ''Ring-Creastă'', where soil was excavated.

* ''Năvodari'' work site, where the sea shore sand was loaded into trucks.

In parallel, work was undergone to level the terrain where the rail road and roadway would flank the Canal. The work quota for one prisoner was usually per day. This had to be excavated, loaded into the wagons, transported, rolled over and leveled. The detainees transferred from Pitești in May 1950 had to load able wagons and transport the dirt for over . Their quota was per day – 40 wagons were necessary to fulfill it – this being 3–4 times greater that the quota meant for free workers at the canal.

Those who were not able to fulfill the quota were persecuted, starting with the reduction of food quantity, assignment to additional labor after program, denial of family contact of any kind, and even solitary.

At the end of July 1950 disciplinary brigades were established (brigades 13 and 14), initially composed of former Pitești prisoners, headed by Iosif Steier and Coloman Fuchs. Violent reeducation was initiated there. Prisoners transferred form Pitești and Gherla, who were not considered fully reeducated, or canal workers who were actively opposing the camp regime, were transferred to these brigades, where they were tortured until they unmasked themselves. One of the most violent manifestation occurred on the night of 21 June 1951 (later referred to – by prisoners – as St. Bartholomew's Night) when 14–15 inmates were brutally beaten up in brigade 14's shed by reeducated brigadiers such as Maximilian Sobolevschi, Constantin Sofronie, Pompiliu Lie, Ion Lupașcu, Simion Enăchescu, Ion Bogdănescu, and others.

Medication smuggling was practiced in the labor camp. Drugs were confiscated from the inmates packages and then sold back to the desperate ones on the black market. The pillory

The pillory is a device made of a wooden or metal framework erected on a post, with holes for securing the head and hands, used during the medieval and renaissance periods for punishment by public humiliation and often further physical abuse. ...

was also addressed to people who tried to escape and sometimes to those who refused to work. There were recorded cases where guards framed escape scenarios and fatally shot prisoners. Such an achievement was rewarded by a 15-day leave.

One of the events that had a major influence on both the Canal detention conditions and reeducation process itself was the death of doctor Ion Simionescu on 12 July 1951. The 67-year-old prisoner was repeatedly tortured by the reeducation team, beaten up, starved as assigneded to the most exhausting tasks until – under the claim that he had to go to the toilet – he headed towards the camp fence, where he was shot by the security guards. Following this, prisoners and Constantin Ionașcu wrote and managed to sneak out of the camp and the country a series of papers that originally reached Radio Ankara, via Constanța

Constanța (, , ) is a city in the Dobruja Historical regions of Romania, historical region of Romania. A port city, it is the capital of Constanța County and the country's Cities in Romania, fourth largest city and principal port on the Black ...

.

Forced labor on the canal site was ceased on 18 July 1953. Most of the Peninsula labor force were transferred to Aiud

Aiud (; , , Hungarian pronunciation: ; ) is a city located in Alba County, Transylvania, Romania. The city's population is 21,307 (2021). It has the status of municipiu. The city derives its name ultimately from Saint Giles (Aegidius), to whom t ...

and Gherla

Gherla (; ; ) is a municipality in Cluj County, Romania (in the historical region of Transylvania). It is located from Cluj-Napoca on the river Someșul Mic, and has a population of 19,873 as of 2021. Three villages are administered by the city: ...

prisons. The remaining prisoners had to dismantle the railroad lines and shacks and also hand over to civilian teams the unfinished buildings.

Due to the inhumane work and detention regime, the death toll was high. In the summer of 1951, behind the camp medical facility, 4–5 bodies were lined up on a daily basis, while the same death rate was registered in the 1952–1953 winter. Investigations conducted by the Association of Former Political Prisoners of Romania (AFDPR) Constanța, based on death records from the villages found along the Canal route, indicate 6,355 "Canal workers" (a euphemism

A euphemism ( ) is when an expression that could offend or imply something unpleasant is replaced with one that is agreeable or inoffensive. Some euphemisms are intended to amuse, while others use bland, inoffensive terms for concepts that the u ...

for detainees) died during the 1949–1953 period.

Trials

Eugen Țurcanu trial

In order to cover up the responsibility for the events, the Securitate wanted to frame the prisoners themselves. As a result, the number of people aware of the ongoing situation was limited. Except its founders: Gheorghe Pintilie and Alexandru Nicolschi, leaders of the OS: Iosif Nemeș and Tudor Sepeanu and the prison political officers, very few people from the administration – even those who were aware of the fact that beatings are used during inquiry – were aware of the methods used for extracting information. Prisoner Vintilă Vais was incarcerated at Gherla in May 1951. Arrested for presumed frontier crossing felony, he was in fact victim of a personal scuffle with Marin Jianu, the Interior Minister deputy, about whom he had compromising information. Under torture, Vais made a series of compromising reports on high-ranking people from the Party, such asTeohari Georgescu

Teohari Georgescu (January 31, 1908 – December 31, 1976) was a Romanian statesman and a high-ranking member of the Romanian Communist Party.

Early life

Born in Chitila, near Bucharest, he was the third of seven children of Constantin and ...

, Petru Groza

Petru Groza (7 December 1884 – 7 January 1958) was a Romanian politician, best known as the first Prime Minister of Romania, Prime Minister of the Romanian Communist Party, Communist Party-dominated government under Soviet Union, Soviet Sovie ...

, Alexandru Nicolschi, Tudor Sepeanu, Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, and others. This caused unrest in the Securitate and would eventually lead to the secrecy disavowal surrounding the proceedings. Together with other events such as the fact that, after two years of reeducation, there was not much relevant data to report, the considerable number of deaths and the increasing number of fabrications (made under torture) that consumed the Securitate resources, it led to the termination of the program.

Within this trial, a number of 22 detainees are indicted: Eugen Țurcanu, Vasile Pușcașu, Alexandru Popa, Maximilian Sobolevski, Mihai Livinschi, Ion Stoian, Cristian Șerbănescu, Constantin P. Ionescu, Octavian Voinea, Aristotel Popescu, Pafnutie Pătrășcanu, Dan Dumitrescu, Vasile Păvlăvoaie, Octavian Zbranca, Constantin Juberian, Cornel Popovici, Ion Voin, Ioan Cerbu, Gheorghe Popescu, Grigore Romanescu, Cornel Pop, and Constantin Juberian. The inquiry was done in parallel at both Ploiești

Ploiești ( , , ), formerly spelled Ploești, is a Municipiu, city and county seat in Prahova County, Romania. Part of the historical region of Muntenia, it is located north of Bucharest.

The area of Ploiești is around , and it borders the Ble ...

and Râmnicu Sărat

Râmnicu Sărat (also spelled ''Rîmnicu Sărat'', , or ''Rebnick''; ) is a municipiu, city in Buzău County, Romania, in the historical region of Muntenia. It was first attested in a document of 1439, and raised to the rank of ''municipiu'' in ...

, and the investigators sought to present the Pitești and Gherla actions as planned by the Iron Guard leader, Horia Sima

Horia Sima (3 July 1906 – 25 May 1993) was a Romanian fascist politician, best known as the second and last leader of the fascist paramilitary movement known as the Iron Guard (also known as the Legion of the Archangel Michael). Sima was a ...

(at the time in exile in Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

), in order to compromise the Communist Party. The investigator wrote down the Interrogation Protocol, while the prisoner was subjected to physical and mental pressure until he signed them. On 10 November 1954 all the defendants were sentenced to death

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence ordering that an offender be punished in s ...

by the Military Court

A court-martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of members of the arme ...

for Internal Affair Units. With the exception of A. Popa, O. Voinea, A. Popescu, D. Dumitrescu, and P. Pătrășcanu (whose punishments were later commuted), all others were shot at Jilava on 17 December 1954.

Notes

References

* * * *External links

*Memorial of Sorrow – Episode 11 – The Pitești Experiment

The Pitești phenomenon

* *

Additional sources

* * * * * Dimitrie Bejan – ''Vifornița cea mare'' (The great storm), București, Editura Tehnică, 1996. * Vasile Blănaru-Flamură – ''Mercenarii infernului. Blestemul dosarelor. Incredibile întâmplări din Gulagurile românești'' (Mercenaries of hell. Papers of damnation. Incredible stories from the Romanian Gulag), București, Elisavaros, 1999. * ** ** * * Vasile Gurău – ''După gratii'' (Behind bars), București, Albatros, 1999. * Pintilie, Iacob – ''Vremuri de bejenie si surghiun'' (Days of exodus and banishment) * * * Constantin Ionașcu – ''Ororile și farmecul detenției'' (The ordeal and charm of detention), București, Fundația Academia Civică, 2010. * – ''Memorii I. Din țara sârmelor ghimpate'' (Memoirs I. From the land of barbed wire), Iași,Polirom

Polirom or Editura Polirom ("Polirom" Publishing House) is a Romanian publishing house with a tradition of publishing classics of international literature and also various titles in the fields of social sciences, such as psychology, sociology, and ...

, 2009.

* Sabin Ivan – ''Pe urmele adevărului'' (Chasing truth), Constanța, Ex Ponto, 1996.

*

* Dan Lucinescu – ''Jertfa'' (Sacrifice), Siaj.

* George Mârzanca – ''Patru ani am fost... "bandit". Confesiuni'' (Four years I was a... "bandit". Confessions), București, Vasile Cârlova, 1997.

* Teohar Mihaidaș – ''Pe muntele Ebal'' (On mount Ebal), Cluj, Clusium, 1990.

*

*

{{DEFAULTSORT:Reeducation in Communist Romania

Mind control

Propaganda in Romania

Socialist Republic of Romania

Communism in Romania

Political repression in Romania