Radio Acoustic Ranging on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Radio acoustic ranging, occasionally written as "radio-acoustic ranging" and sometimes abbreviated RAR, was a method for determining a ship's precise location at sea by detonating an explosive charge underwater near the ship, detecting the arrival of the underwater sound waves at remote locations, and radioing the time of arrival of the sound waves at the remote stations to the ship, allowing the ship's crew to use

Radio acoustic ranging, occasionally written as "radio-acoustic ranging" and sometimes abbreviated RAR, was a method for determining a ship's precise location at sea by detonating an explosive charge underwater near the ship, detecting the arrival of the underwater sound waves at remote locations, and radioing the time of arrival of the sound waves at the remote stations to the ship, allowing the ship's crew to use

To fix their position using radio acoustic ranging, a ship's crew first ascertained the temperature and

To fix their position using radio acoustic ranging, a ship's crew first ascertained the temperature and

/ref>Rude, Gilbert T., "The Modern Chart," ''Motor Boating'', May 1935, pp. 35, 68.

/ref> In deep waters, such as those that prevailed in the

/ref>

Realizing the potential of these applications of acoustics to

Realizing the potential of these applications of acoustics to

/ref> He envisioned improving on the Submarine Signal Company's system of underwater noise generators and attached radio transmitters, as well as other previous concepts, by creating what would become known as the radio acoustic ranging method. Like echosounding, this method required an accurate calculation of the speed of sound through water.Anonymous, "Ocean's Depth Measured By Radio Robot," ''Popular Mechanics'', December 1938, pp. 828-830.

/ref> Heck oversaw tests at Coast and Geodetic Survey headquarters in

Operating in the

Operating in the

/ref> Use of the buoys spread to the U.S. West Coast as well because they were cheaper to set up and operate than a shore station. Radio acoustic ranging had limitations and drawbacks. Local peculiarities in the propagation of acoustic waves in the water column could degrade its accuracy, there were problems with maintaining hydrophone stations, and handling explosive charges posed a considerable danger to personnel and ships.hydro-international.com Theberge, Albert E., "First Developments of Electronic Navigation Systems," 27 March 2009.

/ref> On one occasion a Coast and Geodetic Survey Corps

/ref> Radio acoustic ranging was an early step along the path to modern electronic navigation systems, oceanographic telemetering systems, and the development of marine seismic surveying. The technique also laid the groundwork for the development ofcelebrating200years.noaa.gov Top Tens: Breakthroughs: Hydrographic Survey Techniques: Acoustic Survey Methods: Radio Acoustic Ranging

/ref> The Coast and Geodetic Survey's radio-sonobuoys, developed to support radio acoustic ranging, were the ancestors of the

NOAA History: The Start of the Acoustic Work of the Coast and Geodetic Survey

* ttps://noaacoastsurvey.wordpress.com/2016/09/27/a-monumental-history/ NOAA Coast Survey: A Monumental History

Hydro International "System Without Fixed Points"

EVOLUTION OF THE SONOBUOY.pdf Holler, Roger A., "The Evolution of the Sonobuoy From World War II to The Cold War," ''U.S. Navy Journal of Underwater Acoustics'', January 2014

{Dead link, date=February 2023 , bot=InternetArchiveBot , fix-attempted=yes Navigational aids Acoustics Hydrography Radio navigation Surveying United States Coast and Geodetic Survey

Radio acoustic ranging, occasionally written as "radio-acoustic ranging" and sometimes abbreviated RAR, was a method for determining a ship's precise location at sea by detonating an explosive charge underwater near the ship, detecting the arrival of the underwater sound waves at remote locations, and radioing the time of arrival of the sound waves at the remote stations to the ship, allowing the ship's crew to use

Radio acoustic ranging, occasionally written as "radio-acoustic ranging" and sometimes abbreviated RAR, was a method for determining a ship's precise location at sea by detonating an explosive charge underwater near the ship, detecting the arrival of the underwater sound waves at remote locations, and radioing the time of arrival of the sound waves at the remote stations to the ship, allowing the ship's crew to use true range multilateration

True-range multilateration (also termed range-range multilateration and spherical multilateration) is a method to determine the location of a movable vehicle or stationary point in space using multiple ranges (distances) between the vehicle/poi ...

to determine the ship's position. Developed by the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey

The United States Coast and Geodetic Survey ( USC&GS; known as the Survey of the Coast from 1807 to 1836, and as the United States Coast Survey from 1836 until 1878) was the first scientific agency of the Federal government of the United State ...

in 1923 and 1924 for use in accurately fixing the position of survey ship

A survey vessel is any type of ship or boat that is used for underwater surveys, usually to collect data for mapping or planning underwater construction or mineral extraction. It is a type of research vessel, and may be designed for the pu ...

s during hydrographic survey

Hydrographic survey is the science of measurement and description of features which affect maritime navigation, marine construction, dredging, offshore wind farms, offshore oil exploration and drilling and related activities. Surveys may als ...

operations, it was the first navigation

Navigation is a field of study that focuses on the process of monitoring and controlling the motion, movement of a craft or vehicle from one place to another.Bowditch, 2003:799. The field of navigation includes four general categories: land navig ...

technique in human history other than dead reckoning

In navigation, dead reckoning is the process of calculating the current position of a moving object by using a previously determined position, or fix, and incorporating estimates of speed, heading (or direction or course), and elapsed time. T ...

that did not require visual observation of a landmark, marker, light, or celestial body

An astronomical object, celestial object, stellar object or heavenly body is a naturally occurring physical entity, association, or structure that exists within the observable universe. In astronomy, the terms ''object'' and ''body'' are of ...

, and the first non-visual means to provide precise positions. First employed operationally in 1924, radio acoustic ranging remained in use until 1944, when new radio navigation

Radio navigation or radionavigation is the application of radio waves to geolocalization, determine a position of an object on the Earth, either the vessel or an obstruction. Like radiolocation, it is a type of Radiodetermination-satellite servi ...

techniques developed during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

rendered it obsolete.

Technique

salinity

Salinity () is the saltiness or amount of salt (chemistry), salt dissolved in a body of water, called saline water (see also soil salinity). It is usually measured in g/L or g/kg (grams of salt per liter/kilogram of water; the latter is dimensio ...

of sea water in the vicinity of the ship to determine an accurate velocity of sound through the water. The crew then threw a small TNT

Troponin T (shortened TnT or TropT) is a part of the troponin complex, which are proteins integral to the contraction of skeletal and heart muscles. They are expressed in skeletal and cardiac myocytes. Troponin T binds to tropomyosin and helps ...

bomb off the ship's stern. It exploded at a depth of about , and a chronograph

A chronograph is a specific type of watch that is used as a stopwatch combined with a display watch. A basic chronograph has hour and minute hands on the main dial to tell the time, a small seconds hand to tell that the watch is running, and ...

aboard the ship automatically recorded the time the explosion was heard at the ship. The sound traveled outward from the explosion, eventually reaching hydrophone

A hydrophone () is a microphone designed for underwater use, for recording or listening to underwater sound. Most hydrophones contains a piezoelectric transducer that generates an electric potential when subjected to a pressure change, such as a ...

s at known locations – shore stations, anchored station ships, or moored buoy

A buoy (; ) is a buoyancy, floating device that can have many purposes. It can be anchored (stationary) or allowed to drift with ocean currents.

History

The ultimate origin of buoys is unknown, but by 1295 a seaman's manual referred to navig ...

s – at a distance from the ship. Each hydrophone was connected to a radio transmitter that automatically sent a signal indicating the time its hydrophone detected the sound. At the distances involved – generally less than – each of these radio signals arrived at the ship at essentially the same instant that each of the remote hydrophones detected the sound of the explosion. The ship's chronograph automatically recorded the time each radio signal arrived at the ship. By subtracting the time of the explosion from the time of radio signal reception, the ship's crew could determine the length of time the sound wave required to travel from the point of the explosion to each remote hydrophone and, knowing the speed of sound in the surrounding sea water, could multiply the sound's travel time by the velocity of sound in sea water to determine the distance between the explosion and the hydrophone. By determining the distance to at least two remote hydrophones in known locations, the ship's crew could use true range multilateration

True-range multilateration (also termed range-range multilateration and spherical multilateration) is a method to determine the location of a movable vehicle or stationary point in space using multiple ranges (distances) between the vehicle/poi ...

to fix the ship's position.Theberge, Alfred E., "System Without Fixed Points: Development of the Radio-Acoustic Ranging Navigation Technique (Part 1)," hydro-international.com, December 2, 2009./ref>Rude, Gilbert T., "The Modern Chart," ''Motor Boating'', May 1935, pp. 35, 68.

/ref> In deep waters, such as those that prevailed in the

Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five Borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is ...

along the United States West Coast

The West Coast of the United States, also known as the Pacific Coast and the Western Seaboard, is the coastline along which the Western United States meets the North Pacific Ocean. The term typically refers to the contiguous U.S. states of Calif ...

, the Coast and Geodetic Survey could rely upon shore stations to support radio acoustic ranging because the deep water allowed sound to travel to the coast. Along the United States East Coast

The East Coast of the United States, also known as the Eastern Seaboard, the Atlantic Coast, and the Atlantic Seaboard, is the region encompassing the coast, coastline where the Eastern United States meets the Atlantic Ocean; it has always pla ...

, where shallower waters prevailed, sound had greater difficulty in reaching the coast, and the Coast and Geodetic Survey relied more heavily on anchored station ships, and later moored buoys, to support radio acoustic ranging.

Chronographs recorded times to the hundredth of a second, and the crew of a ship using radio acoustic ranging could determine their ship's distance from the remote hydrophone stations to within , allowing them to plot their ship's position with great accuracy for the time. With sound waves traveling from the point of the explosion to the distant hydrophones at about , ships occasionally used radio acoustic ranging at distances of over between ship and hydrophone station, and distances of were common.

Development history

Precursors

Radio acoustic ranging had its origins in a growing understanding of underwater acoustics and their practical application during the early decades of the 20th century, and developed in parallel withecho sounding

Echo sounding or depth sounding is the use of sonar for ranging, normally to determine the depth (coordinate), depth of water (bathymetry). It involves transmitting acoustic waves into water and recording the time interval between emission and ...

. The first step took place in the early 1900s, when the Submarine Signal Company

RTX Corporation, formerly Raytheon Technologies Corporation, is an American multinational aerospace and defense conglomerate headquartered in Arlington, Virginia. It is one of the largest aerospace and defense manufacturers in the world by reve ...

invented a submarine bell signalling device and a hydrophone that could serve as a receiver of the underwater sounds the bells generated. The crew of a ship equipped with the receiving hydrophone could plot their ship's distance from the submarine bell mechanism and plot intersecting lines from two or more bells to determine the ship's position. The bells were installed at lighthouse

A lighthouse is a tower, building, or other type of physical structure designed to emit light from a system of lamps and lens (optics), lenses and to serve as a beacon for navigational aid for maritime pilots at sea or on inland waterways.

Ligh ...

s, aboard lightvessel

A lightvessel, or lightship, is a ship that acts as a lighthouse. It is used in waters that are too deep or otherwise unsuitable for lighthouse construction. Although some records exist of fire beacons being placed on ships in Roman times, the ...

s, and on buoys along the coasts of North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres. North America is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South Ameri ...

and Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

, and receiving hydrophones were mounted aboard hundreds of ships. It was history's first practical use of acoustics in an ocean environment.

The sinking

Shipwrecking is any event causing a ship to wreck, such as a collision causing the ship to sink; the stranding of a ship on rocks, land or shoal; poor maintenance, resulting in a lack of seaworthiness; or the destruction of a ship either intent ...

of in 1912 due to a collision with an iceberg

An iceberg is a piece of fresh water ice more than long that has broken off a glacier or an ice shelf and is floating freely in open water. Smaller chunks of floating glacially derived ice are called "growlers" or "bergy bits". Much of an i ...

spurred the Canadian

Canadians () are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of their being ''C ...

inventor Reginald Fessenden

Reginald Aubrey Fessenden (October 6, 1866 – July 22, 1932) was a Canadian-American electrical engineer and inventor who received hundreds of List of Reginald Fessenden patents, patents in fields related to radio and sonar between 1891 and 1936 ...

(1866–1932) to begin work on a long-distance underwater sound transmission and reception system that could detect hazards in the path of a ship. This led to the invention of the Fessenden oscillator

A Fessenden oscillator is an electro-acoustic transducer invented by Reginald Fessenden, with development starting in 1912 at the Submarine Signal Company of Boston. It was the first successful acoustical echo ranging device. Similar in operat ...

, an electro-acoustic transducer

A transducer is a device that Energy transformation, converts energy from one form to another. Usually a transducer converts a signal in one form of energy to a signal in another.

Transducers are often employed at the boundaries of automation, M ...

which by 1914 had a proven ability to transmit and receive sound at a distance of across Massachusetts Bay

Massachusetts Bay is a bay on the Gulf of Maine that forms part of the central coastline of Massachusetts.

Description

The bay extends from Cape Ann on the north to Plymouth Harbor on the south, a distance of about . Its northern and sout ...

and to detect an iceberg ahead of a ship at a range of by bouncing sound off it and detecting the echo, as well as an occasional ability to detect the reflection of sound off the ocean bottom. Further impetus to developing practical applications of underwater acoustics came from World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, which prompted the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

, United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

, and United States Army Coast Artillery Corps

The U.S. Army Coast Artillery Corps (CAC) was an administrative corps responsible for coastal, harbor, and anti-aircraft defense of the United States and its possessions between 1901 and 1950. The CAC also operated heavy and railway artiller ...

to experiment with sound as a means of detecting submerged submarine

A submarine (often shortened to sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. (It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability.) The term "submarine" is also sometimes used historically or infor ...

s. In postwar experiments, the Coast Artillery Corps's Subaqueous Sound Ranging Section conducted experiments in shallow water in Vineyard Sound

Vineyard Sound is the stretch of the Atlantic Ocean which separates the Elizabeth Islands and the southwestern part of Cape Cod from the island of Martha's Vineyard, located offshore from the state of Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), ...

off Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

in which it detonated explosive charges underwater at the ends of established baselines and measured the amount of time it took for the sound to arrive at hydrophones at the other ends of the baselines in order to establish very accurate measurements of the speed of sound through water. And in 1923, the Submarine Signal Company improved upon its underwater signaling devices by equipping them with radio transmitters that sent signals both to identify the particular device and to indicate to approaching ships that it would generate an acoustic signal at a specific time interval after it sent the radio signal, allowing ships to identify the specific navigational aid

A navigational aid (NAVAID), also known as aid to navigation (ATON), is any sort of signal, markers or guidance equipment which aids the traveler in navigation, usually nautical or aviation travel. Common types of such aids include lighthouses, ...

they were approaching and to take advantage of a one-way ranging capability that let their crews determine their direction and distance from the navigational aid.hydro-international.com The Discovery of Long-Distance Sound Transmission in the Ocean/ref>

Nicholas Heck

Realizing the potential of these applications of acoustics to

Realizing the potential of these applications of acoustics to hydrographic survey

Hydrographic survey is the science of measurement and description of features which affect maritime navigation, marine construction, dredging, offshore wind farms, offshore oil exploration and drilling and related activities. Surveys may als ...

ing and navigation

Navigation is a field of study that focuses on the process of monitoring and controlling the motion, movement of a craft or vehicle from one place to another.Bowditch, 2003:799. The field of navigation includes four general categories: land navig ...

, particularly along the United States West Coast, where fog

Fog is a visible aerosol consisting of tiny water droplets or ice crystals suspended in the air at or near the Earth's surface. Reprint from Fog can be considered a type of low-lying cloud usually resembling stratus and is heavily influenc ...

frequently interfered with attempts to fix ship positions accurately, Ernest Lester Jones

Colonel Ernest Lester Jones (April 14, 1876 – April 9, 1929) was born in East Orange, New Jersey and was commissioned a hydrographic and geodetic engineer. In addition to extended study abroad, he held an A. B. degree and an honorary A. M. degre ...

(1876–1929), then Director of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey

The United States Coast and Geodetic Survey ( USC&GS; known as the Survey of the Coast from 1807 to 1836, and as the United States Coast Survey from 1836 until 1878) was the first scientific agency of the Federal government of the United State ...

, in consultation with United States Coast and Geodetic Survey Corps

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Commissioned Officer Corps (informally the NOAA Corps) is one of eight federal uniformed services of the United States, and operates under the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (N ...

officers

An officer is a person who has a position of authority in a hierarchical organization. The term derives from Old French ''oficier'' "officer, official" (early 14c., Modern French ''officier''), from Medieval Latin ''officiarius'' "an officer," fro ...

, decided to investigate the use of acoustics in both depth finding and navigation. Nicholas H. Heck (1882–1953), a Coast and Geodetic Survey Corps officer, had been assigned from 1917 to 1919 to World War I service with the United States Naval Reserve Force, during which he had researched the use of underwater acoustics

Underwater acoustics (also known as hydroacoustics) is the study of the propagation of sound in water and the interaction of the mechanical waves that constitute sound with the water, its contents and its boundaries. The water may be in the oce ...

in antisubmarine warfare

Anti-submarine warfare (ASW, or in the older form A/S) is a branch of underwater warfare that uses surface warships, aircraft, submarines, or other platforms, to find, track, and deter, damage, or destroy enemy submarines. Such operations a ...

. He was the obvious choice to lead the new effort.

By January 1923, the Coast and Geodetic Survey had decided to install a Hayes sonic rangefinder – an early echo sounder

Echo sounding or depth sounding is the use of sonar for ranging, normally to determine the depth of water (bathymetry). It involves transmitting acoustic waves into water and recording the time interval between emission and return of a pulse; ...

– aboard the survey ship USC&GS ''Guide'', which the Coast and Geodetic Survey planned to commission into its fleet later that year; successful operation of the sonic rangefinder would require a precise understanding of the speed of sound through water. When Heck contacted E. A. Stephenson of the U.S. Army Coast Artillery Corps to inform him of this plan and to inquire further about the Vineyard Sound experiments, Stephenson suggested that a system of hydrophones detecting the sound of underwater explosions could allow Coast and Geodetic Survey ships to fix their position while conducting surveys. Heck agreed, but believed that existing navigation aids would not meet the needs of the Coast and Geodetic Survey in terms of the immediacy and accuracy of position fixes.NOAA History: The Start of the Acoustic Work of the Coast and Geodetic Survey/ref> He envisioned improving on the Submarine Signal Company's system of underwater noise generators and attached radio transmitters, as well as other previous concepts, by creating what would become known as the radio acoustic ranging method. Like echosounding, this method required an accurate calculation of the speed of sound through water.Anonymous, "Ocean's Depth Measured By Radio Robot," ''Popular Mechanics'', December 1938, pp. 828-830.

/ref> Heck oversaw tests at Coast and Geodetic Survey headquarters in

Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, that demonstrated that shipboard recording of the time of an explosion could be performed accurately enough for his concept to work. He worked with Dr. E. A. Eckhardt, a physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe. Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate cau ...

, and M. Keiser, an electrical engineer

Electrical engineering is an engineering discipline concerned with the study, design, and application of equipment, devices, and systems that use electricity, electronics, and electromagnetism. It emerged as an identifiable occupation in the l ...

, of the National Bureau of Standards

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) is an agency of the United States Department of Commerce whose mission is to promote American innovation and industrial competitiveness. NIST's activities are organized into physical sc ...

to develop a hydrophone system that could automatically send a radio signal when it detected the sound of an underwater explosion. When the Coast and Geodetic Survey commissioned ''Guide'' in 1923, Heck had her based at New London, Connecticut

Connecticut ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York (state), New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. ...

. Under his direction, ''Guide'' both tested her new echo sounder's ability to make accurate depth soundings and conducted radio acoustic ranging experiments in cooperation with the U.S. Army Coast Artillery Corps. Despite many difficulties, testing of both echo sounding and radio acoustic ranging wrapped up successfully in November 1923.

The cruise of the ''Guide''

In late November 1923, with Heck aboard, ''Guide'' began a voyage from New London viaPuerto Rico

; abbreviated PR), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, is a Government of Puerto Rico, self-governing Caribbean Geography of Puerto Rico, archipelago and island organized as an Territories of the United States, unincorporated territo ...

and the Panama Canal

The Panama Canal () is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Caribbean Sea with the Pacific Ocean. It cuts across the narrowest point of the Isthmus of Panama, and is a Channel (geography), conduit for maritime trade between th ...

to San Diego

San Diego ( , ) is a city on the Pacific coast of Southern California, adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a population of over 1.4 million, it is the List of United States cities by population, eighth-most populous city in t ...

, California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

, where she would be based in the future, with her route planned to take her over a wide variety of ocean depths so that she could continue to test her echo sounder. ''Guide'' made history during the voyage, becoming the first Coast and Geodetic Survey ship to use echo sounding to measure and record the depth of the sea at points along her course; she also measured water temperatures and took water samples so that the Scripps Institution for Biological Research (now the Scripps Institution of Oceanography

Scripps Institution of Oceanography (SIO) is the center for oceanography and Earth science at the University of California, San Diego. Its main campus is located in La Jolla, with additional facilities in Point Loma.

Founded in 1903 and incorpo ...

) at La Jolla

La Jolla ( , ) is a hilly, seaside neighborhood in San Diego, California, occupying of curving coastline along the Pacific Ocean. The population reported in the 2010 census was 46,781. The climate is mild, with an average daily temperature o ...

, California, could measure salinity

Salinity () is the saltiness or amount of salt (chemistry), salt dissolved in a body of water, called saline water (see also soil salinity). It is usually measured in g/L or g/kg (grams of salt per liter/kilogram of water; the latter is dimensio ...

levels. She also compared echo sounder soundings with those made by lead lines, discovering that using a single speed of sound through water, as had been the previous practice by those conducting echo sounding experiments, yielded acoustic depth-finding results that did not match the depths found by lead lines. Before she reached San Diego in December 1923, she had accumulated much data beneficial to the study of the movement of sound waves through water and measuring their velocity under varying conditions of salinity, density

Density (volumetric mass density or specific mass) is the ratio of a substance's mass to its volume. The symbol most often used for density is ''ρ'' (the lower case Greek letter rho), although the Latin letter ''D'' (or ''d'') can also be u ...

, and temperature, information essential both to depth-finding and radio acoustic ranging.

Upon arriving in California, Heck and ''Guide'' personnel in consultation with the Scripps Institution developed formulas that allowed accurate echo sounding of depths in all but the shallowest waters and installed hydrophones at La Jolla and Oceanside

Oceanside may refer to:

Places United States

*Oceanside, California

** Oceanside Transit Center

*Oceanside, New York

Oceanside is a Hamlet (New York), hamlet and census-designated place (CDP) located in the southern part of the town of Hempst ...

, California, to allow experimentation with radio acoustic ranging. Under Heck's direction, ''Guide'' then conducted experiments off the coast of California during the early months of 1924 that demonstrated that accurate echo sounding was possible using the new formulas. Experiments with radio acoustic ranging, despite initial difficulties, demonstrated that the method also was practical, although difficulty with getting some of the explosive charges to detonate hampered some of the experimental program. In April 1924, the Coast and Geodetic Survey concluded that both echo sounding and radio acoustic ranging were fundamentally sound, with no foundational problems left to solve, and that all that remained necessary was continued development and refinement of both techniques during their operational use. Heck turned over continued development of echo sounding and radio acoustic ranging to ''Guides commanding officer, Commander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank as well as a job title in many army, armies. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countri ...

Robert Luce, and returned to his duties in Washington, D.C.

Later development

Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five Borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is ...

off Oregon

Oregon ( , ) is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is a part of the Western U.S., with the Columbia River delineating much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while t ...

in 1924, ''Guide'' became the first ship to employ radio acoustic ranging operationally. Off Oregon that year, she successfully employed the technique at a distance of between the ranging explosion and the remote hydrophones detecting its sound and in the process achieved the first observed indication of the ocean sound layer that was later called the sound fixing and ranging (SOFAR) channel or deep sound channel (DSC). In 1928, French investigators extended this range, detonating a 30-kg (66-pound) explosive in the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

between Algiers

Algiers is the capital city of Algeria as well as the capital of the Algiers Province; it extends over many Communes of Algeria, communes without having its own separate governing body. With 2,988,145 residents in 2008Census 14 April 2008: Offi ...

in French Algeria

French Algeria ( until 1839, then afterwards; unofficially ; ), also known as Colonial Algeria, was the period of History of Algeria, Algerian history when the country was a colony and later an integral part of France. French rule lasted until ...

and Toulon

Toulon (, , ; , , ) is a city in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of southeastern France. Located on the French Riviera and the historical Provence, it is the prefecture of the Var (department), Var department.

The Commune of Toulon h ...

, France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, and detecting the sound at a range of .

Initially, Heck and others involved in the development of radio acoustic ranging thought the technique would prove least effective along the coast of the Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest (PNW; ) is a geographic region in Western North America bounded by its coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains to the east. Though no official boundary exists, the most common ...

, where they assumed that the sound of wave action along the coast and the difficulty of setting up shore stations and cables would reduce the success of radio acoustic ranging; in contrast, they thought that conditions along the United States East Coast

The East Coast of the United States, also known as the Eastern Seaboard, the Atlantic Coast, and the Atlantic Seaboard, is the region encompassing the coast, coastline where the Eastern United States meets the Atlantic Ocean; it has always pla ...

would pose no challenges. In fact, the opposite proved true: Among other problems, the relatively shallow water along the U.S. East Coast attenuated the sound of ranging explosions and shoal

In oceanography, geomorphology, and Earth science, geoscience, a shoal is a natural submerged ridge, bank (geography), bank, or bar that consists of, or is covered by, sand or other unconsolidated material, and rises from the bed of a body ...

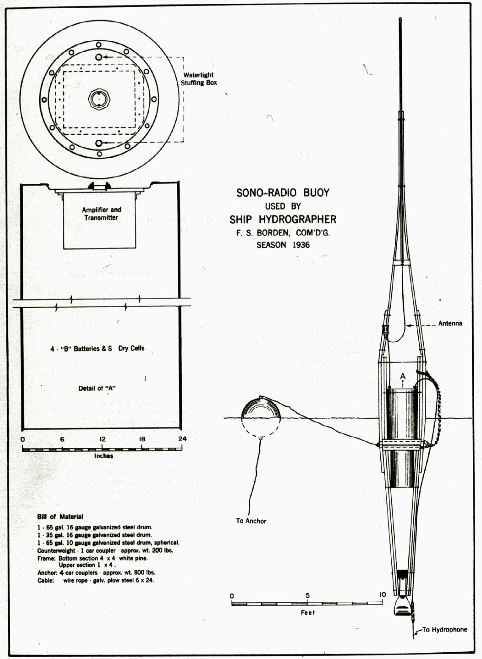

s often blocked the sound from reaching shore at all. To overcome these difficulties, the Coast and Geodetic Survey anchored vessels well offshore along the U.S. East Coast to serve as hydrophone stations. In 1931, the Coast and Geodetic Survey proposed replacing the manned station ships with "radio-sonobuoys", and in July 1936 it began to place radio-sonobuoys in service. The 700-pound (317.5-kg) buoys – equipped with subsurface hydrophones, batteries, and radio transmitters that automatically sent a radio signal when their hydrophones detected the sound of a ranging explosion – could be deployed or recovered by Coast and Geodetic Survey ships in five minutes.EVOLUTION OF THE SONOBUOY.pdf Holler, Roger A., "The Evolution of the Sonobuoy From World War II to The Cold War," ''U.S. Navy Journal of Underwater Acoustics'', January 2014, p. 323./ref> Use of the buoys spread to the U.S. West Coast as well because they were cheaper to set up and operate than a shore station. Radio acoustic ranging had limitations and drawbacks. Local peculiarities in the propagation of acoustic waves in the water column could degrade its accuracy, there were problems with maintaining hydrophone stations, and handling explosive charges posed a considerable danger to personnel and ships.hydro-international.com Theberge, Albert E., "First Developments of Electronic Navigation Systems," 27 March 2009.

/ref> On one occasion a Coast and Geodetic Survey Corps

ensign

Ensign most often refers to:

* Ensign (flag), a flag flown on a vessel to indicate nationality

* Ensign (rank), a navy (and former army) officer rank

Ensign or The Ensign may also refer to:

Places

* Ensign, Alberta, Alberta, Canada

* Ensign, Ka ...

on board the survey ship USC&GS ''Hydrographer'' inserted a radio acoustic ranging bomb in the mouth of a shark

Sharks are a group of elasmobranch cartilaginous fish characterized by a ribless endoskeleton, dermal denticles, five to seven gill slits on each side, and pectoral fins that are not fused to the head. Modern sharks are classified within the ...

and released the shark, only to watch in horror as it swam back to the ship and exploded next to ''Hydrographer''′s hull

Hull may refer to:

Structures

* The hull of an armored fighting vehicle, housing the chassis

* Fuselage, of an aircraft

* Hull (botany), the outer covering of seeds

* Hull (watercraft), the body or frame of a sea-going craft

* Submarine hull

Ma ...

; the explosion rocked the ship. Aboard ''Guide'' in 1927, tragedy almost struck when a petty officer

A petty officer (PO) is a non-commissioned officer in many navies. Often they may be superior to a seaman, and subordinate to more senior non-commissioned officers, such as chief petty officers.

Petty officers are usually sailors that have ...

handling a bomb lit its fuse and then fell when the ship lurched; he dropped the bomb, which rolled into a gutter. The petty officer fell again before finally reaching the bomb and heaving it overboard just in time; it exploded alongside the ship just as it hit the water. The concussion prompted half the crew to rush up from below decks to find out what had happened.

As late as 1942, radio acoustic ranging remained important enough to the Coast and Geodetic Survey for it to devote just over 100 pages of its ''Hydrographic Manual'' to it. However, World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, which by then had been raging for three years, gave impetus to the rapid development of purely radio-based navigation systems to assist bomber

A bomber is a military combat aircraft that utilizes

air-to-ground weaponry to drop bombs, launch aerial torpedo, torpedoes, or deploy air-launched cruise missiles.

There are two major classifications of bomber: strategic and tactical. Strateg ...

s in finding their targets in darkness and bad weather. Such radio navigation

Radio navigation or radionavigation is the application of radio waves to geolocalization, determine a position of an object on the Earth, either the vessel or an obstruction. Like radiolocation, it is a type of Radiodetermination-satellite servi ...

systems were easier to maintain than hydrophone stations and did not require the handling of explosives and, as the new systems matured, the Coast and Geodetic Survey began to apply them to maritime navigation. Radio acoustic ranging appears not to have been used after 1944, and by 1946, Coast and Geodetic Survey ships had switched over to the new SHORAN

SHORAN is an acronym for SHOrt RAnge Navigation, a type of electronic navigation and bombing system using a precision radar beacon. It was developed during World War II and the first stations were set up in Europe as the war was ending, and was op ...

electronic navigation technology to fix their positions.

Legacy

The first non-visual method of precise navigation in human history, and the first that could be used at any time of day or night and in any weather conditions, radio acoustic ranging was a major step forward in the development of modern navigation systems. Nicholas Heck revolutionized oceanic surveying through the use of radio electronic ranging to establish ship locations, one of his major contributions tooceanography

Oceanography (), also known as oceanology, sea science, ocean science, and marine science, is the scientific study of the ocean, including its physics, chemistry, biology, and geology.

It is an Earth science, which covers a wide range of to ...

. His work related to the technique also helped to develop underwater sound velocity tables allowing the establishment of "true depths" of up to using echo sounding.NOAA History: Profiles in Time – C&GS Biographies: Nicholas Hunter Heck/ref> Radio acoustic ranging was an early step along the path to modern electronic navigation systems, oceanographic telemetering systems, and the development of marine seismic surveying. The technique also laid the groundwork for the development of

sonar

Sonar (sound navigation and ranging or sonic navigation and ranging) is a technique that uses sound propagation (usually underwater, as in submarine navigation) to navigate, measure distances ( ranging), communicate with or detect objects o ...

s capable of looking ahead of and to the sides of vessels./ref> The Coast and Geodetic Survey's radio-sonobuoys, developed to support radio acoustic ranging, were the ancestors of the

sonobuoy

A sonobuoy (a portmanteau of sonar and buoy) is a small expendable sonar buoy dropped from aircraft or ships for anti-submarine warfare or underwater acoustic research. Sonobuoys are typically around in diameter and long. When floating on t ...

s used by ships and aircraft in antisubmarine warfare and underwater acoustic research today.

See also

* * * *References

External links

NOAA History: The Start of the Acoustic Work of the Coast and Geodetic Survey

* ttps://noaacoastsurvey.wordpress.com/2016/09/27/a-monumental-history/ NOAA Coast Survey: A Monumental History

Hydro International "System Without Fixed Points"

EVOLUTION OF THE SONOBUOY.pdf Holler, Roger A., "The Evolution of the Sonobuoy From World War II to The Cold War," ''U.S. Navy Journal of Underwater Acoustics'', January 2014

{Dead link, date=February 2023 , bot=InternetArchiveBot , fix-attempted=yes Navigational aids Acoustics Hydrography Radio navigation Surveying United States Coast and Geodetic Survey