Queen's Hall on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Queen's Hall was a concert hall in Langham Place, London, opened in 1893. Designed by the architect

The site on which the hall was built was bounded by the present-day Langham Place,

The site on which the hall was built was bounded by the present-day Langham Place,

The Queen's Hall first opened its doors on 25 November 1893. Newman gave a children's party in the afternoon, and in the evening 2,000 invited guests attended what Elkin describes as "a sort of private view", with popular selections played by the

The Queen's Hall first opened its doors on 25 November 1893. Newman gave a children's party in the afternoon, and in the evening 2,000 invited guests attended what Elkin describes as "a sort of private view", with popular selections played by the

To fill the hall during the heat of the late-summer period, when London audiences tended to stay away from theatres and concert halls, Newman planned to run a ten-week season of

To fill the hall during the heat of the late-summer period, when London audiences tended to stay away from theatres and concert halls, Newman planned to run a ten-week season of

Many events at the Queen's Hall were not presented by Newman. The hall was frequently let to organisations such as the

Many events at the Queen's Hall were not presented by Newman. The hall was frequently let to organisations such as the

The standard of orchestral playing in London was adversely affected by the deputy system, in which orchestral players, if offered a better-paid engagement, could send a substitute to a rehearsal or a concert. The treasurer of the Royal Philharmonic Society described it thus: "A, whom you want, signs to play at your concert. He sends B (whom you don't mind) to the first rehearsal. B, without your knowledge or consent, sends C to the second rehearsal. Not being able to play at the concert, C sends D, whom you would have paid five shillings to stay away". The members of the Queen's Hall Orchestra were not highly paid; Wood recalled in his memoirs, "the rank and file of the orchestra received only 45s a week for six Promenade concerts and three rehearsals, a guinea for one Symphony concert and rehearsal, and half-a-guinea for Sunday afternoon or evening concerts ''without'' rehearsal". Offered ''ad hoc'' engagements at better pay by other managements, many of the players took full advantage of the deputy system. Newman determined to put an end to it. After a rehearsal in which Wood was faced with a sea of entirely unfamiliar faces in his own orchestra, Newman came on the platform to announce: "Gentlemen, in future there will be no deputies; good morning". Forty players resigned ''en bloc'' and formed their own orchestra, the

The standard of orchestral playing in London was adversely affected by the deputy system, in which orchestral players, if offered a better-paid engagement, could send a substitute to a rehearsal or a concert. The treasurer of the Royal Philharmonic Society described it thus: "A, whom you want, signs to play at your concert. He sends B (whom you don't mind) to the first rehearsal. B, without your knowledge or consent, sends C to the second rehearsal. Not being able to play at the concert, C sends D, whom you would have paid five shillings to stay away". The members of the Queen's Hall Orchestra were not highly paid; Wood recalled in his memoirs, "the rank and file of the orchestra received only 45s a week for six Promenade concerts and three rehearsals, a guinea for one Symphony concert and rehearsal, and half-a-guinea for Sunday afternoon or evening concerts ''without'' rehearsal". Offered ''ad hoc'' engagements at better pay by other managements, many of the players took full advantage of the deputy system. Newman determined to put an end to it. After a rehearsal in which Wood was faced with a sea of entirely unfamiliar faces in his own orchestra, Newman came on the platform to announce: "Gentlemen, in future there will be no deputies; good morning". Forty players resigned ''en bloc'' and formed their own orchestra, the

On the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, Newman, Wood and Speyer were obliged to consider the immediate future of concert-giving at the Queen's Hall. They discussed whether the Proms should continue as planned, and agreed to go ahead. However, within months anti-German feeling forced Speyer to leave the country and seek refuge in the U.S., and there was a campaign to ban all German music from concerts. Newman put out a statement declaring that German music would be played as planned: "The greatest examples of Music and Art are world possessions and unassailable even by the prejudices and passions of the hour".

When Speyer left Britain in 1915, Chappell's took on financial responsibility for the Queen's Hall concerts. The resident orchestra was renamed the New Queen's Hall Orchestra. Concerts continued throughout the war years, with fewer major new works than before, although there were nevertheless British premieres of pieces by Bartók, Stravinsky and Debussy. An historian of the Proms, Ateş Orga, wrote: "Concerts often had to be re-timed to coincide with the 'All Clear' between air raids. Falling bombs, shrapnel, anti-aircraft fire and the droning of

On the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, Newman, Wood and Speyer were obliged to consider the immediate future of concert-giving at the Queen's Hall. They discussed whether the Proms should continue as planned, and agreed to go ahead. However, within months anti-German feeling forced Speyer to leave the country and seek refuge in the U.S., and there was a campaign to ban all German music from concerts. Newman put out a statement declaring that German music would be played as planned: "The greatest examples of Music and Art are world possessions and unassailable even by the prejudices and passions of the hour".

When Speyer left Britain in 1915, Chappell's took on financial responsibility for the Queen's Hall concerts. The resident orchestra was renamed the New Queen's Hall Orchestra. Concerts continued throughout the war years, with fewer major new works than before, although there were nevertheless British premieres of pieces by Bartók, Stravinsky and Debussy. An historian of the Proms, Ateş Orga, wrote: "Concerts often had to be re-timed to coincide with the 'All Clear' between air raids. Falling bombs, shrapnel, anti-aircraft fire and the droning of  In the middle of the impasse Newman's health failed, and he died in November 1926 after a brief illness. Wood wrote, "I feared everything would come to a standstill, for I had never so much as engaged an extra player without having discussed it with him first". Newman's assistant, W. W. Thompson, took over as manager of the orchestra and the concerts, but at this crucial point Chappells withdrew financial support for the Proms. After lengthy negotiations, the BBC took over from Chappells in 1927 as sponsor. The Proms were saved, and the hall continued to play host to celebrity concerts throughout the rest of the 1920s and the '30s, some promoted by the BBC, and others as hitherto by a range of choral societies, impresarios and orchestras. As Chappells owned the title "New Queen's Hall Orchestra", the resident orchestra had to change its name once again and was now known as Sir Henry J. Wood's Symphony Orchestra.Elkin (1944), p. 33

In the middle of the impasse Newman's health failed, and he died in November 1926 after a brief illness. Wood wrote, "I feared everything would come to a standstill, for I had never so much as engaged an extra player without having discussed it with him first". Newman's assistant, W. W. Thompson, took over as manager of the orchestra and the concerts, but at this crucial point Chappells withdrew financial support for the Proms. After lengthy negotiations, the BBC took over from Chappells in 1927 as sponsor. The Proms were saved, and the hall continued to play host to celebrity concerts throughout the rest of the 1920s and the '30s, some promoted by the BBC, and others as hitherto by a range of choral societies, impresarios and orchestras. As Chappells owned the title "New Queen's Hall Orchestra", the resident orchestra had to change its name once again and was now known as Sir Henry J. Wood's Symphony Orchestra.Elkin (1944), p. 33

On the outbreak of the

On the outbreak of the  On the afternoon of 10 May 1941, there was an Elgar concert at the hall. Sargent conducted the ''

On the afternoon of 10 May 1941, there was an Elgar concert at the hall. Sargent conducted the ''

NQHO history

at the

NQHO and Queen's Hall history

at New Queen's Hall Orchestra official website (archived) {{Coord, 51, 31, 5, N, 0, 8, 33, W, type:landmark, display=title Former concert halls in London Former buildings and structures in the City of Westminster Charles J. Phipps buildings 1893 establishments in England 1941 disestablishments in England Music venues completed in 1893 Demolished buildings and structures in England

Thomas Knightley

Thomas Edward Knightley (1824–1905) was a British architect responsible for designing the Queen's Hall and St Paul's Church, Isle of Dogs in London.

Knightley was sometimes considered eccentric

Eccentricity or eccentric may refer to:

* Ecc ...

, it had room for an audience of about 2,500 people. It became London's principal concert venue. From 1895 until 1941, it was the home of the promenade concerts

The BBC Proms or Proms, formally named the Henry Wood Promenade Concerts Presented by the BBC, is an eight-week summer season of daily orchestral classical music concerts and other events held annually, predominantly in the Royal Albert Hal ...

("The Proms") founded by Robert Newman together with Henry Wood

Sir Henry Joseph Wood (3 March 186919 August 1944) was an English conductor best known for his association with London's annual series of promenade concerts, known as the The Proms, Proms. He conducted them for nearly half a century, introd ...

. The hall had drab decor and cramped seating but superb acoustics. It became known as the "musical centre of the ritishEmpire

An empire is a "political unit" made up of several territories and peoples, "usually created by conquest, and divided between a dominant center and subordinate peripheries". The center of the empire (sometimes referred to as the metropole) ex ...

", and several of the leading musicians and composers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries performed there, including Claude Debussy

(Achille) Claude Debussy (; 22 August 1862 – 25 March 1918) was a French composer. He is sometimes seen as the first Impressionist composer, although he vigorously rejected the term. He was among the most influential composers of the ...

, Edward Elgar, Maurice Ravel and Richard Strauss.

In the 1930s, the hall became the main London base of two new orchestras, the BBC Symphony Orchestra

The BBC Symphony Orchestra (BBC SO) is a British orchestra based in London. Founded in 1930, it was the first permanent salaried orchestra in London, and is the only one of the city's five major symphony orchestras not to be self-governing. T ...

and the London Philharmonic Orchestra

The London Philharmonic Orchestra (LPO) is one of five permanent symphony orchestras based in London. It was founded by the conductors Sir Thomas Beecham and Malcolm Sargent in 1932 as a rival to the existing London Symphony and BBC Symphony ...

. These two ensembles raised the standards of orchestral playing in London to new heights, and the hall's resident orchestra, founded in 1893, was eclipsed and it disbanded in 1930. The new orchestras attracted another generation of musicians from Europe and the United States, including Serge Koussevitzky, Willem Mengelberg

Joseph Wilhelm Mengelberg (28 March 1871 – 21 March 1951) was a Dutch conductor, famous for his performances of Beethoven, Brahms, Mahler and Strauss with the Concertgebouw Orchestra in Amsterdam. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest s ...

, Arturo Toscanini

Arturo Toscanini (; ; March 25, 1867January 16, 1957) was an Italian conductor. He was one of the most acclaimed and influential musicians of the late 19th and early 20th century, renowned for his intensity, his perfectionism, his ear for orch ...

, Bruno Walter

Bruno Walter (born Bruno Schlesinger, September 15, 1876February 17, 1962) was a German-born conductor, pianist and composer. Born in Berlin, he escaped Nazi Germany in 1933, was naturalised as a French citizen in 1938, and settled in the U ...

and Felix Weingartner

Paul Felix Weingartner, Edler von Münzberg (2 June 1863 – 7 May 1942) was an Austrian conductor, composer and pianist.

Life and career

Weingartner was born in Zara, Dalmatia, Austria-Hungary (now Zadar, Croatia), to Austrian parents. ...

.

In 1941, during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, the building was destroyed by incendiary bombs in the London Blitz

The Blitz was a German bombing campaign against the United Kingdom in 1940 and 1941, during the Second World War. The term was first used by the British press and originated from the term , the German word meaning 'lightning war'.

The Germa ...

. Despite much lobbying for the hall to be rebuilt, the government decided against doing so. The main musical functions of the Queen's Hall were taken over by the Royal Albert Hall

The Royal Albert Hall is a concert hall on the northern edge of South Kensington, London. One of the UK's most treasured and distinctive buildings, it is held in trust for the nation and managed by a registered charity which receives no govern ...

for the Proms, and the new Royal Festival Hall for the general concert season.

Background

The site on which the hall was built was bounded by the present-day Langham Place,

The site on which the hall was built was bounded by the present-day Langham Place, Riding House Street

Riding House Street is a street in central London in the City of Westminster.

History

Riding House Street (originally Lane) started off as a straight and narrow connection between Edward Street in the west and Great Titchfield Street in the east ...

and Great Portland Street

Great Portland Street in the West End of London links Oxford Street with Albany Street and the A501 Marylebone Road and Euston Road. A commercial street including some embassies, it divides Fitzrovia, to the east, from Marylebone to the west. ...

. In 1820 the land was bought by the Crown

A crown is a traditional form of head adornment, or hat, worn by monarchs as a symbol of their power and dignity. A crown is often, by extension, a symbol of the monarch's government or items endorsed by it. The word itself is used, partic ...

during the development of John Nash's Regent Street

Regent Street is a major shopping street in the West End of London. It is named after George, the Prince Regent (later George IV) and was laid out under the direction of the architect John Nash and James Burton. It runs from Waterloo Place ...

. Between then and the building of the hall, the site was first sublet to a coachmaker and stablekeeper, and in 1851 a bazaar occupied the site. In 1887, the leaseholder, Francis Ravenscroft, negotiated a building agreement with the Crown, providing for the clearing of the site and the erection of a new concert hall. The name of the new building was intended to be either the "Victoria Concert Hall" or the "Queen's Concert Hall". The name finally chosen, the "Queen's Hall", was decided very shortly before the hall opened. The historian Robert Elkin speculates that the alternative "Victoria Concert Hall" was abandoned as liable to confusion with the "Royal Victoria Music Hall", the formal name of the Old Vic

Old or OLD may refer to:

Places

*Old, Baranya, Hungary

* Old, Northamptonshire, England

*Old Street station, a railway and tube station in London (station code OLD)

*OLD, IATA code for Old Town Municipal Airport and Seaplane Base, Old Town, Ma ...

.

The new hall was to provide a much-needed music venue in the centre of London. St James's Hall

St. James's Hall was a concert hall in London that opened on 25 March 1858, designed by architect and artist Owen Jones, who had decorated the interior of the Crystal Palace. It was situated between the Quadrant in Regent Street and Piccadilly, ...

, just south of Oxford Circus, was too small, had serious safety problems, and was so poorly ventilated as to be unpleasant. Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence simply as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from ...

in his capacity as a music critic commented on "the old unvaried round of Steinway Hall

Steinway Hall (German: ) is the name of buildings housing concert halls, showrooms and sales departments for Steinway & Sons pianos. The first Steinway Hall was opened in 1866 in New York City. Today, Steinway Halls and are located in cities such ...

, Prince's Hall

Prince's Hall was a concert venue in Piccadilly, London.

It was part of the premises of the Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours, at 190–195 Piccadilly, situated behind the galleries where annual exhibitions of the Institute took plac ...

and St James's Hall

St. James's Hall was a concert hall in London that opened on 25 March 1858, designed by architect and artist Owen Jones, who had decorated the interior of the Crystal Palace. It was situated between the Quadrant in Regent Street and Piccadilly, ...

", and warmly welcomed the new building.

Construction

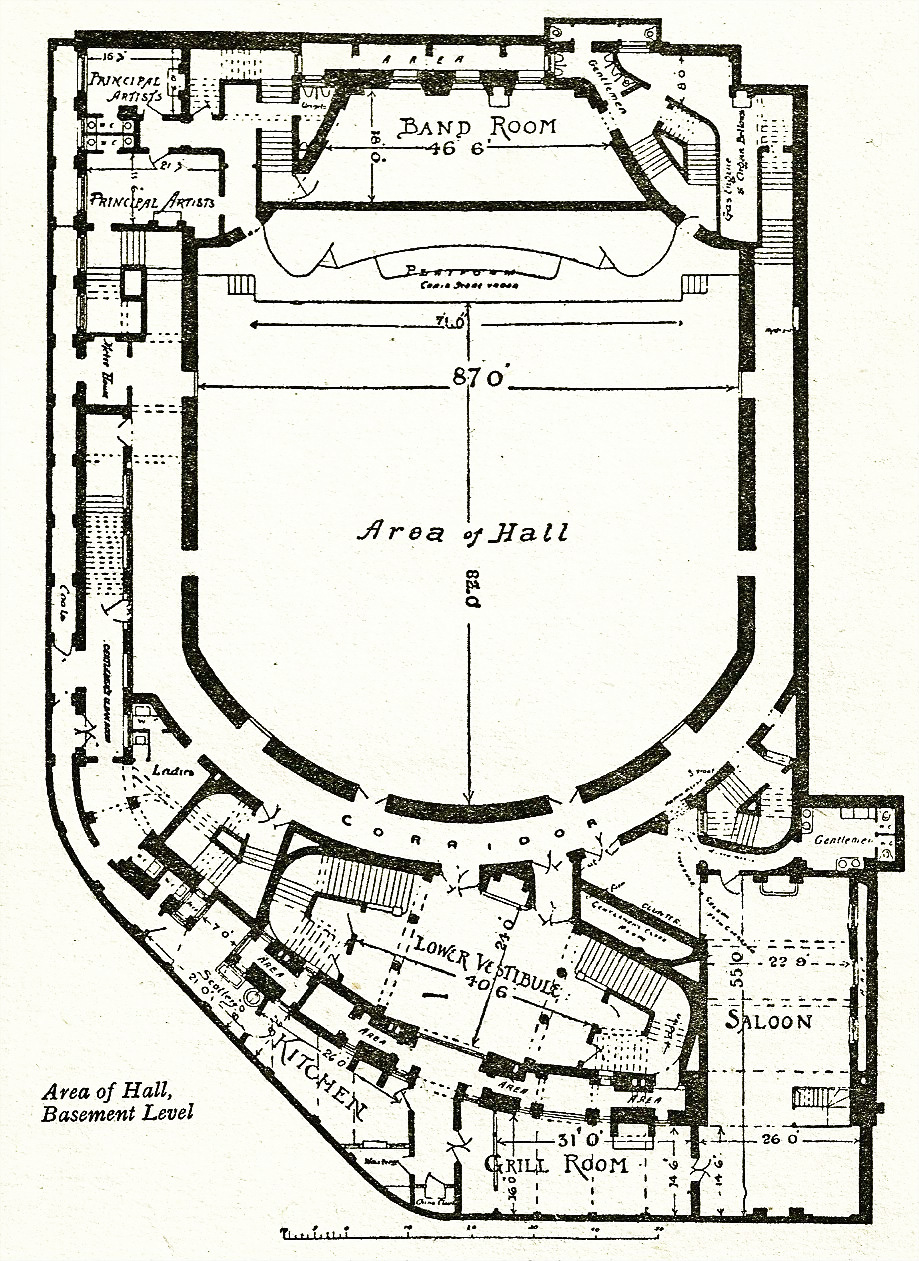

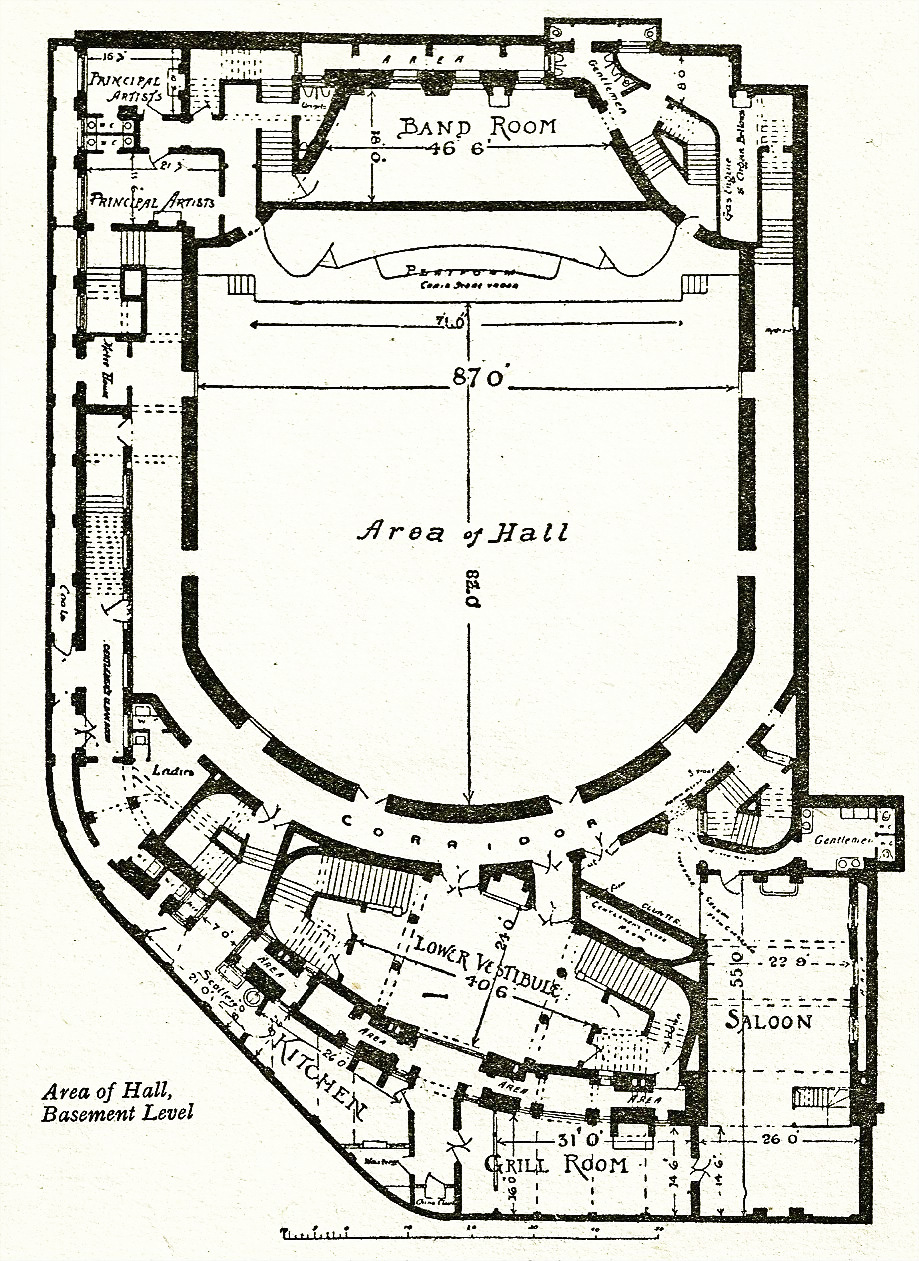

Ravenscroft commissioned the architect Thomas Edward Knightley to design the new hall. Using a floor plan previously prepared by C. J. Phipps, Knightley designed a hall with a floor area of 21,000 square feet (2,000 m²) and an audience capacity of 2,500."The Queen's Hall", ''The Observer

''The Observer'' is a British newspaper published on Sundays. It is a sister paper to ''The Guardian'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', whose parent company Guardian Media Group Limited acquired it in 1993. First published in 1791, it is the w ...

'', 23 November 1913, p. 6 Contemporary newspapers commented on the unusual elevation of the building, with the grand tier at street level, and the stalls and arena downstairs. The exterior carving was by Sidney W. Elmes and Son, and the furnishing was by Lapworth Brothers and Harrison. The lighting was a combination of gas and electricity.Elkin (1944), p. 18.

The original decor consisted of grey and terracotta walls, Venetian red

Venetian red is a light and warm (somewhat unsaturated) pigment that is a darker shade of red, derived from nearly pure ferric oxide (Fe2O3) of the hematite type. Modern versions are frequently made with synthetic red iron oxide.

Historically, ...

seating, large red lampshades suspended just above the orchestra's heads, mirrors surrounding the arena, and portraits of the leading composers to the sides of the platform.Elkin (1946), p. 89 and (1944), p. 18. The paintwork was intended to be the colour of "the belly of a London mouse", and Knightley is said to have kept a string of dead mice in the paint shop in order to ensure the correct tone. The arena had moveable seating on a "brownish carpet that blended with the dull fawnish colour of the walls". The arched ceiling had an elaborate painting of the Paris Opéra

The Paris Opera (, ) is the primary opera and ballet company of France. It was founded in 1669 by Louis XIV as the , and shortly thereafter was placed under the leadership of Jean-Baptiste Lully and officially renamed the , but continued to be k ...

, by Carpegat, described by E. M. Forster

Edward Morgan Forster (1 January 1879 – 7 June 1970) was an English author, best known for his novels, particularly ''A Room with a View'' (1908), ''Howards End'' (1910), and ''A Passage to India'' (1924). He also wrote numerous short stori ...

, as "the attenuated Cupids who encircle the ceiling of the Queen's Hall, inclining each to each with vapid gesture, and clad in sallow pantaloons".

In the centre of the arena there was a fountain containing pebbles, goldfish and waterlilies. According to the conductor Sir Thomas Beecham

Sir Thomas Beecham, 2nd Baronet, CH (29 April 18798 March 1961) was an English conductor and impresario best known for his association with the London Philharmonic and the Royal Philharmonic orchestras. He was also closely associated with th ...

, "Every three or four minutes some fascinating young female fell into the fountain and had to be rescued by a chivalrous swain. It must have happened thirty-five times every night. Foreigners came from all parts of Europe to see it". At the top of the building, adjoining the conservatory, was the Queen's Small Hall, seating 500, for recitals, chamber-music concerts and other small-scale presentations. In July 1894, Bernard Shaw described it as "cigar-shaped with windows in the ceiling, and reminiscent of a ship's saloon … now much the most comfortable of our small concert rooms". The hall provided modern facilities, open frontage for carriages and parking room, a press room, public spaces and bars.

At the time, and subsequently, the hall was celebrated for its superb acoustics, unmatched by any other large hall in London. Soon after its opening, Shaw praised it as "a happy success acoustically".Laurence, p. 295 Knightley followed the example of earlier buildings noted for fine acoustics; the walls of the auditorium were lined with wood, fixed clear of the walls on thick battens, and coarse canvas was stretched over the wood and then sealed and decorated. He calculated that the unbroken surface and the wooden lining would be "like the body of the violin – resonant". ''The Observer

''The Observer'' is a British newspaper published on Sundays. It is a sister paper to ''The Guardian'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', whose parent company Guardian Media Group Limited acquired it in 1993. First published in 1791, it is the w ...

'' commented that the building resembled a violin in construction and shape, and also that "the ground plan of the orchestra was founded on the bell of a horn".

Shortly before the opening, Ravenscroft appointed Robert Newman as manager. Newman had already had three different careers, as a stockjobber

Stockjobbers were institutions that acted as market makers in the London Stock Exchange. The business of stockjobbing emerged in the 1690s during England's Financial Revolution. During the 18th century the jobbers attracted numerous critiques from ...

, a bass soloist, and a concert agent. The rest of his career was associated with the Queen's Hall, and the names of the hall and the manager became synonymous.Wood, p. 319

Early years

The Queen's Hall first opened its doors on 25 November 1893. Newman gave a children's party in the afternoon, and in the evening 2,000 invited guests attended what Elkin describes as "a sort of private view", with popular selections played by the

The Queen's Hall first opened its doors on 25 November 1893. Newman gave a children's party in the afternoon, and in the evening 2,000 invited guests attended what Elkin describes as "a sort of private view", with popular selections played by the Band of the Coldstream Guards

The Band of the Coldstream Guards is one of the oldest and best known bands in the British Army, having been officially formed on 16 May 1785 under the command of Major C F Eley.

History

The band of the Coldstream Guards was officially formed un ...

, and songs, piano and organ solos performed by well-known musicians. After the performances, the seats in the arena were removed, lavish refreshments were served, and the guests danced.Elkin (1944), p. 21

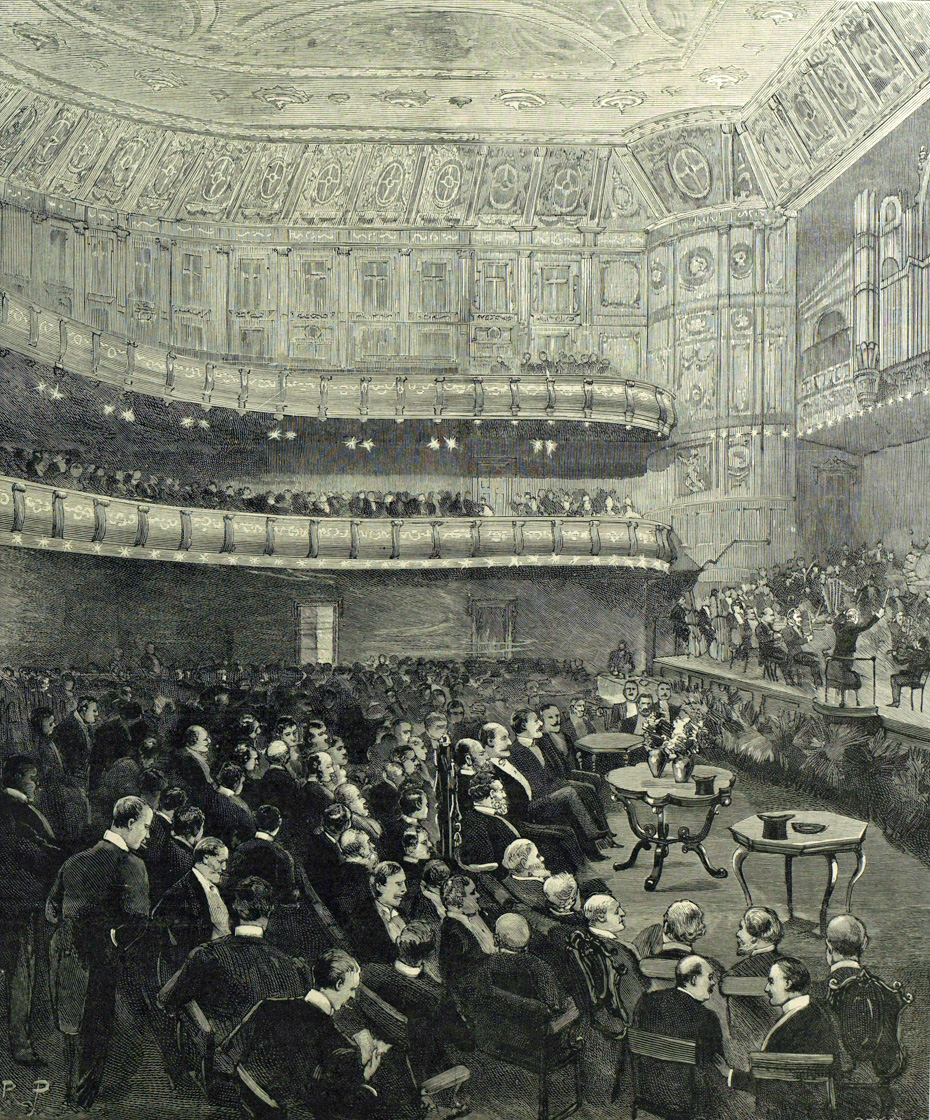

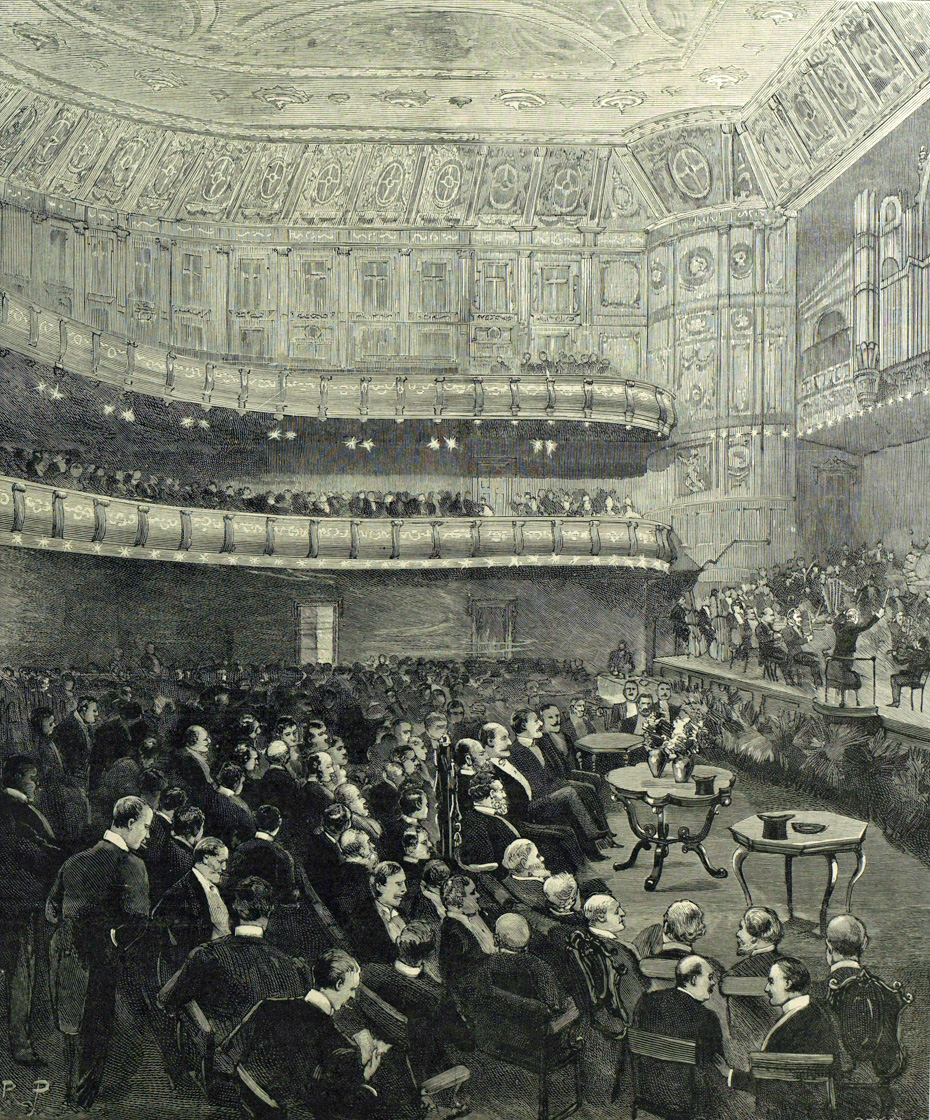

On 27 November there was a smoking concert

Smoking concerts were live performances, usually of music, before an audience of men only, popular during the Victorian era. These social occasions were instrumental in introducing new musical forms to the public. At these functions men would s ...

given by the Royal Amateur Orchestral Society, of which Prince Alfred (the second son of Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 21 ...

) was both patron and leader. The performance was attended by the Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the rulers ...

and the Duke of Connaught

Duke of Connaught and Strathearn was a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom that was granted on 24 May 1874 by Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland to her third son, Prince Arthur. At the same time, he was also ...

. Knightley had built a royal box in the grand circle, but Prince Alfred told Newman, "my brother would never sit in that", and Newman had it demolished. The royal party was seated in armchairs in the front of the stalls (pictured right). The programme consisted of orchestral works by Sullivan, Gounod

Charles-François Gounod (; ; 17 June 181818 October 1893), usually known as Charles Gounod, was a French composer. He wrote twelve operas, of which the most popular has always been ''Faust (opera), Faust'' (1859); his ''Roméo et Juliette'' (18 ...

, Auber, Mendelssohn

Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (3 February 18094 November 1847), born and widely known as Felix Mendelssohn, was a German composer, pianist, organist and conductor of the early Romantic period. Mendelssohn's compositions include sym ...

and Tchaikovsky

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky , group=n ( ; 7 May 1840 – 6 November 1893) was a Russian composer of the Romantic period. He was the first Russian composer whose music would make a lasting impression internationally. He wrote some of the most popu ...

, and solos from the violinist Tivadar Nachéz and the baritone David Ffrangcon-Davies.

The official opening of the hall took place on 2 December. Frederic Hymen Cowen

Sir Frederic Hymen Cowen (29 January 1852 – 6 October 1935), was an English composer, conductor and pianist.

Early years and musical education

Cowen was born Hymen Frederick Cohen at 90 Duke Street, Kingston, Jamaica, the fifth and last c ...

conducted; the National Anthem

A national anthem is a patriotic musical composition symbolizing and evoking eulogies of the history and traditions of a country or nation. The majority of national anthems are marches or hymns in style. American, Central Asian, and European n ...

was sung by Emma Albani

Dame Emma Albani, DBE (born Marie-Louise-Emma-Cécile Lajeunesse; 1 November 18473 April 1930) was a Canadian-British operatic soprano of the 19th century and early 20th century, and the first Canadian singer to become an international star. He ...

and a choir of 300 voices assembled at short notice by Newman; Mendelssohn

Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (3 February 18094 November 1847), born and widely known as Felix Mendelssohn, was a German composer, pianist, organist and conductor of the early Romantic period. Mendelssohn's compositions include sym ...

's '' Hymn of Praise'' followed, with Albani, Margaret Hoare and Edward Lloyd Edward Lloyd may refer to:

Politicians

*Edward Lloyd (MP for Montgomery), Welsh lawyer and politician

* Edward Lloyd (16th-century MP) (died 1547) for Buckingham

*Edward Lloyd, 1st Baron Mostyn (1768–1854), British politician

*Edward Lloyd (Colon ...

as soloists. In the second part of the programme there was a performance of Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. Beethoven remains one of the most admired composers in the history of Western music; his works rank amongst the most performed of the classical ...

's ''Emperor Concerto

The Piano Concerto No. 5 in E-flat major, Op. 73, known as the Emperor Concerto in English-speaking countries, is a concerto composed by Ludwig van Beethoven for piano and orchestra. Beethoven composed the concerto in 1809 under salary in Vienna ...

'', with Frederick Dawson as soloist.

From the autumn of 1894, the hall was adopted as the venue for the annual winter season of concerts of the Philharmonic Society of London

The Royal Philharmonic Society (RPS) is a British music society, formed in 1813. Its original purpose was to promote performances of instrumental music in London. Many composers and performers have taken part in its concerts. It is now a memb ...

, which had formerly been held at St James's Hall. At the first Philharmonic concert at the Queen's Hall, Alexander Mackenzie conducted the first performance in England of Tchaikovsky's '' Pathétique Symphony'', which was so well received that it was repeated, by popular acclaim, at the next concert. During the 1894–95 season, Edvard Grieg

Edvard Hagerup Grieg ( , ; 15 June 18434 September 1907) was a Norwegian composer and pianist. He is widely considered one of the foremost Romantic era composers, and his music is part of the standard classical repertoire worldwide. His use of ...

and Camille Saint-Saëns

Charles-Camille Saint-Saëns (; 9 October 183516 December 1921) was a French composer, organist, conductor and pianist of the Romantic music, Romantic era. His best-known works include Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso (1863), the Piano C ...

conducted performances of their works. The Society remained at the Queen's Hall until 1941.

Promenade concerts

To fill the hall during the heat of the late-summer period, when London audiences tended to stay away from theatres and concert halls, Newman planned to run a ten-week season of

To fill the hall during the heat of the late-summer period, when London audiences tended to stay away from theatres and concert halls, Newman planned to run a ten-week season of promenade concerts

The BBC Proms or Proms, formally named the Henry Wood Promenade Concerts Presented by the BBC, is an eight-week summer season of daily orchestral classical music concerts and other events held annually, predominantly in the Royal Albert Hal ...

, with low-priced tickets to attract a wider audience than that of the main season. Costs needed to be kept down, and Newman decided not to engage a star conductor, but invited the young and little known Henry Wood

Sir Henry Joseph Wood (3 March 186919 August 1944) was an English conductor best known for his association with London's annual series of promenade concerts, known as the The Proms, Proms. He conducted them for nearly half a century, introd ...

to conduct the whole season. There had been various seasons of promenade concerts in London since 1838, under conductors from Louis Antoine Jullien

Louis George Maurice Adolphe Roche Albert Abel Antonio Alexandre Noë Jean Lucien Daniel Eugène Joseph-le-brun Joseph-Barême Thomas Thomas Thomas-Thomas Pierre Arbon Pierre-Maurel Barthélemi Artus Alphonse Bertrand Dieudonné Emanuel Josué V ...

to Arthur Sullivan. Sullivan's concerts in the 1870s had been particularly successful because he offered his audiences something more than the usual light music. He introduced major classical works, such as Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. Beethoven remains one of the most admired composers in the history of Western music; his works rank amongst the most performed of the classical ...

symphonies, normally restricted to the more expensive concerts presented by the Philharmonic Society and others. Newman aimed to do the same: "I am going to run nightly concerts and train the public by easy stages. Popular at first, gradually raising the standard until I have created a public for classical and modern music".

Newman's determination to make the promenade concerts attractive to everyone led him to permit smoking during concerts, which was not formally prohibited at the Proms until 1971. Refreshments were available in all parts of the hall throughout the concerts, not only during intervals. Prices were about one fifth of those customarily charged for classical concerts: the promenade (the standing area) was one shilling, the balcony two shillings, and the grand circle (reserved seats) three and five shillings.

Newman needed to find financial backing for his first season. Dr George Cathcart, a wealthy ear, nose and throat

Otorhinolaryngology ( , abbreviated ORL and also known as otolaryngology, otolaryngology–head and neck surgery (ORL–H&N or OHNS), or ear, nose, and throat (ENT)) is a surgical subspeciality within medicine that deals with the surgical a ...

specialist, offered to sponsor it on two conditions: that Wood should conduct every concert, and that the pitch of the orchestral instruments should be lowered to the European standard ''diapason normal''. Concert pitch in England was nearly a semitone

A semitone, also called a half step or a half tone, is the smallest musical interval commonly used in Western tonal music, and it is considered the most dissonant when sounded harmonically.

It is defined as the interval between two adjacent no ...

higher than that used on the continent, and Cathcart regarded it as damaging for singers' voices.Elkin (1944), p. 25 Wood, who was a singing teacher as well as a conductor, agreed. The brass and woodwind players of the Queen's Hall Orchestra were unwilling to buy new low-pitched instruments; Cathcart imported a set from Belgium and lent them to the players. After a season, the players recognised that the low pitch would be permanently adopted, and they bought the instruments from him.

On 10 August 1895, the first of the Queen's Hall Promenade Concerts took place. It opened with Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, polemicist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most op ...

's overture to ''Rienzi

' (''Rienzi, the last of the tribunes''; WWV 49) is an early opera by Richard Wagner in five acts, with the libretto written by the composer after Edward Bulwer-Lytton's novel of the same name (1835). The title is commonly shortened to ''Rie ...

'', but the rest of the programme comprised, in the words of an historian of the Proms, David Cox, "for the most part ... blatant trivialities". Newman and Wood gradually tilted the balance from light music to mainstream classical works; within days of the opening concert, Schubert

Franz Peter Schubert (; 31 January 179719 November 1828) was an Austrian composer of the late Classical and early Romantic eras. Despite his short lifetime, Schubert left behind a vast ''oeuvre'', including more than 600 secular vocal wor ...

's Unfinished Symphony

An unfinished symphony is a fragment of a symphony, by a particular composer, that musicians and academics consider incomplete or unfinished for various reasons. The archetypal unfinished symphony is Franz Schubert's Symphony No. 8 (sometimes ...

and further excerpts from Wagner operas were performed. Among the other symphonies presented during the first season were Schubert

Franz Peter Schubert (; 31 January 179719 November 1828) was an Austrian composer of the late Classical and early Romantic eras. Despite his short lifetime, Schubert left behind a vast ''oeuvre'', including more than 600 secular vocal wor ...

's '' Great C Major'', Mendelssohn's ''Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

'' and Schumann

Robert Schumann (; 8 June 181029 July 1856) was a German composer, pianist, and influential music critic. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest composers of the Romantic era. Schumann left the study of law, intending to pursue a career a ...

's Fourth. The concertos included Mendelssohn's Violin Concerto

A violin concerto is a concerto for solo violin (occasionally, two or more violins) and instrumental ensemble (customarily orchestra). Such works have been written since the Baroque period, when the solo concerto form was first developed, up thro ...

and Schumann's Piano Concerto

A piano concerto is a type of concerto, a solo composition in the classical music genre which is composed for a piano player, which is typically accompanied by an orchestra or other large ensemble. Piano concertos are typically virtuoso showpiec ...

. During the season there were 23 novelties, including the London premieres of pieces by Richard Strauss, Tchaikovsky, Glazunov Glazunov (; feminine: Glazunova) is a Russian surname that may refer to:

*Alexander Glazunov (1865–1936), Russian composer

** Glazunov Glacier in Antarctica named after Alexander

* Andrei Glazunov, 19th-century Russian trade expedition leader

* An ...

, Massenet

Jules Émile Frédéric Massenet (; 12 May 1842 – 13 August 1912) was a French composer of the Romantic music, Romantic era best known for his operas, of which he wrote more than thirty. The two most frequently staged are ''Manon'' (1884) ...

and Rimsky-Korsakov

Nikolai Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov . At the time, his name was spelled Николай Андреевичъ Римскій-Корсаковъ. la, Nicolaus Andreae filius Rimskij-Korsakov. The composer romanized his name as ''Nicolas Rimsk ...

. Newman and Wood soon felt able to devote every Monday night of the season principally to Wagner and every Friday night to Beethoven, a pattern that endured for decades.

Other presentations

Many events at the Queen's Hall were not presented by Newman. The hall was frequently let to organisations such as the

Many events at the Queen's Hall were not presented by Newman. The hall was frequently let to organisations such as the Bach Choir

The Bach Choir is a large independent musical organisation founded in London, England in 1876 to give the first performance of J. S. Bach's '' Mass in B minor'' in Britain.

The choir has around 240 active members. Directed by David Hill MBE ( Y ...

and the Philharmonic Society

The Royal Philharmonic Society (RPS) is a British music society, formed in 1813. Its original purpose was to promote performances of instrumental music in London. Many composers and performers have taken part in its concerts. It is now a membe ...

(from 1903 the Royal Philharmonic Society), and later the London Choral Society and Royal Choral Society

The Royal Choral Society (RCS) is an amateur choir, based in London.

History

Formed soon after the opening of the Royal Albert Hall in 1871, the choir gave its first performance as the Royal Albert Hall Choral Society on 8 May 1872 – the choir' ...

. The hall was used for a wide range of other activities, including balls, military band concerts under Sousa, lectures, public meetings, Morris dancing

Morris dancing is a form of English folk dance. It is based on rhythmic stepping and the execution of choreographed figures by a group of dancers, usually wearing bell pads on their shins. Implements such as sticks, swords and handkerchiefs may ...

, Eurythmics

Eurythmics were a British pop duo consisting of Annie Lennox and Dave Stewart. They were both previously in The Tourists, a band which broke up in 1980. The duo released their first studio album, '' In the Garden'', in 1981 to little succ ...

and religious services. On 14 January 1896, the UK's first public film show was presented at the Queen's Hall to members and wives of the Royal Photographic Society by the maker of the ''Kineopticon'' and Fellow of the society, Birt Acres

Birt Acres (23 July 1854 – 27 December 1918) was an American and British photographer and film pioneer. Among his contributions to the early film industry are the first working 35 mm camera in Britain (Wales), and ''Birtac'', the firs ...

, and his colleague, Arthur Melbourne-Cooper

Arthur Melbourne Cooper (15 April 1874 – 28 November 1961) was a British photographer and early filmmaker best known for his pioneering work in stop-motion animation. He produced over three hundred films between 1896 and 1915, of which an estima ...

. This was an improved version of the early Kinetoscope

The Kinetoscope is an early motion picture exhibition device, designed for films to be viewed by one person at a time through a peephole viewer window. The Kinetoscope was not a movie projector, but it introduced the basic approach that woul ...

.

Newman continued to be interested in new entertainments. The music hall

Music hall is a type of British theatrical entertainment that was popular from the early Victorian era, beginning around 1850. It faded away after 1918 as the halls rebranded their entertainment as variety. Perceptions of a distinction in Bri ...

entertainer Albert Chevalier

Albert Chevalier (often listed as Albert Onésime Britannicus Gwathveoyd Louis Chevalier); (21 March 186110 July 1923), was an English music hall comedian, singer and musical theatre actor. He specialised in cockney related humour based on life ...

persuaded him to instigate variety performances in the Queen's Small Hall from 16 January 1899. These shows were well received; ''The Times'' commented that Chevalier's "vogue with the cultured classes is as great and as permanent as with his former patrons".

Despite all these various activities, in the public mind the Queen's Hall quickly became chiefly associated with the promenade concerts. Newman was careful to balance "the Proms", as they became known, with more prestigious and expensive concerts throughout the rest of the year. He would foster the careers of promising artists, and if they were successful at the Proms they would, after two seasons, be given contracts for the main concert series, billed as the Symphony Concerts.Wood, p. 75 The Proms had to be run on the tightest of budgets, but for the Symphony Concert series Newman was willing to pay large fees to attract the most famous musicians. Soloists included Joseph Joachim

Joseph Joachim (28 June 1831 – 15 August 1907) was a Hungarian violinist, conductor, composer and teacher who made an international career, based in Hanover and Berlin. A close collaborator of Johannes Brahms, he is widely regarded as one of t ...

, Fritz Kreisler

Friedrich "Fritz" Kreisler (February 2, 1875 – January 29, 1962) was an Austrian-born American violinist and composer. One of the most noted violin masters of his day, and regarded as one of the greatest violinists of all time, he was known ...

, Nellie Melba

Dame Nellie Melba (born Helen Porter Mitchell; 19 May 186123 February 1931) was an Australian operatic dramatic coloratura soprano (three octaves). She became one of the most famous singers of the late Victorian era and the early 20th centur ...

, Pablo de Sarasate

Pablo Martín Melitón de Sarasate y Navascués (; 10 March 1844 – 20 September 1908), commonly known as Pablo de Sarasate, was a Spanish (Navarrese) violin virtuoso, composer and conductor of the Romantic period. His best known works include ...

, Eugène Ysaÿe

Eugène-Auguste Ysaÿe (; 16 July 185812 May 1931) was a Belgian virtuoso violinist, composer, and conductor. He was regarded as "The King of the Violin", or, as Nathan Milstein put it, the "tsar".

Legend of the Ysaÿe violin

Eugène Ysa� ...

and, most expensive of all, Ignacy Jan Paderewski

Ignacy Jan Paderewski (; – 29 June 1941) was a Polish pianist and composer who became a spokesman for Polish independence. In 1919, he was the new nation's Prime Minister and foreign minister during which he signed the Treaty of Versaill ...

. Conductors included Arthur Nikisch

Arthur Nikisch (12 October 185523 January 1922) was a Hungarian conductor who performed internationally, holding posts in Boston, London, Leipzig and—most importantly—Berlin. He was considered an outstanding interpreter of the music of B ...

and Hans Richter. Among the composers who performed their own works at the hall in its first 20 years were Debussy

(Achille) Claude Debussy (; 22 August 1862 – 25 March 1918) was a French composer. He is sometimes seen as the first Impressionist composer, although he vigorously rejected the term. He was among the most influential composers of the ...

, Elgar

Sir Edward William Elgar, 1st Baronet, (; 2 June 1857 – 23 February 1934) was an English composer, many of whose works have entered the British and international classical concert repertoire. Among his best-known compositions are orchestr ...

, Grieg, Ravel

Joseph Maurice Ravel (7 March 1875 – 28 December 1937) was a French composer, pianist and conductor. He is often associated with Impressionism along with his elder contemporary Claude Debussy, although both composers rejected the term. In ...

, Saint-Saëns, Schoenberg, Richard Strauss and Sullivan.

Early 20th century

In 1901 Newman became the lessee of the hall as well as its manager, but the following year, after unwise investment in theatrical presentations, he was declared bankrupt. The music publisher Chappell and Co took over the lease of the building, retaining Newman as manager. The Queen's Hall orchestra and concerts were rescued by the musical benefactorSir Edgar Speyer

Sir Edgar Speyer, 1st Baronet (7 September 1862 – 16 February 1932) was an American-born financier and philanthropist. Barker 2004. He became a British subject in 1892 and was chairman of Speyer Brothers, the British branch of the Speyer fami ...

, a banker of German origin. Speyer put up the necessary funds, encouraged Newman and Wood to continue with their project of musical education, and underwrote the Proms and the main Symphony Concert seasons. Newman remained manager of the hall until 1906 and manager of the concerts until he died in 1926.

The standard of orchestral playing in London was adversely affected by the deputy system, in which orchestral players, if offered a better-paid engagement, could send a substitute to a rehearsal or a concert. The treasurer of the Royal Philharmonic Society described it thus: "A, whom you want, signs to play at your concert. He sends B (whom you don't mind) to the first rehearsal. B, without your knowledge or consent, sends C to the second rehearsal. Not being able to play at the concert, C sends D, whom you would have paid five shillings to stay away". The members of the Queen's Hall Orchestra were not highly paid; Wood recalled in his memoirs, "the rank and file of the orchestra received only 45s a week for six Promenade concerts and three rehearsals, a guinea for one Symphony concert and rehearsal, and half-a-guinea for Sunday afternoon or evening concerts ''without'' rehearsal". Offered ''ad hoc'' engagements at better pay by other managements, many of the players took full advantage of the deputy system. Newman determined to put an end to it. After a rehearsal in which Wood was faced with a sea of entirely unfamiliar faces in his own orchestra, Newman came on the platform to announce: "Gentlemen, in future there will be no deputies; good morning". Forty players resigned ''en bloc'' and formed their own orchestra, the

The standard of orchestral playing in London was adversely affected by the deputy system, in which orchestral players, if offered a better-paid engagement, could send a substitute to a rehearsal or a concert. The treasurer of the Royal Philharmonic Society described it thus: "A, whom you want, signs to play at your concert. He sends B (whom you don't mind) to the first rehearsal. B, without your knowledge or consent, sends C to the second rehearsal. Not being able to play at the concert, C sends D, whom you would have paid five shillings to stay away". The members of the Queen's Hall Orchestra were not highly paid; Wood recalled in his memoirs, "the rank and file of the orchestra received only 45s a week for six Promenade concerts and three rehearsals, a guinea for one Symphony concert and rehearsal, and half-a-guinea for Sunday afternoon or evening concerts ''without'' rehearsal". Offered ''ad hoc'' engagements at better pay by other managements, many of the players took full advantage of the deputy system. Newman determined to put an end to it. After a rehearsal in which Wood was faced with a sea of entirely unfamiliar faces in his own orchestra, Newman came on the platform to announce: "Gentlemen, in future there will be no deputies; good morning". Forty players resigned ''en bloc'' and formed their own orchestra, the London Symphony Orchestra

The London Symphony Orchestra (LSO) is a British symphony orchestra based in London. Founded in 1904, the LSO is the oldest of London's orchestras, symphony orchestras. The LSO was created by a group of players who left Henry Wood's Queen's ...

.Morrison, p. 24 Newman did not attempt to bar the new orchestra from the Queen's Hall, and its first concert was given there on 9 June 1904, conducted by Richter.

By the 20th century the Queen's Hall was regarded not only as "London's premier concert-hall" but as "the acknowledged musical centre of the Empire

An empire is a "political unit" made up of several territories and peoples, "usually created by conquest, and divided between a dominant center and subordinate peripheries". The center of the empire (sometimes referred to as the metropole) ex ...

". The drabness of its interior decor and the lack of leg-room in the seating attracted criticism. In 1913, ''The Musical Times

''The Musical Times'' is an academic journal of classical music edited and produced in the United Kingdom and currently the oldest such journal still being published in the country.

It was originally created by Joseph Mainzer in 1842 as ''Mainze ...

'' said, "In the placing of the seats apparently no account whatever is taken even of the average length of lower limbs, and it appeared to be the understanding … that legs were to be left in the cloak room. At twopence apiece this would be expensive, and there might be difficulties afterwards if the cloak room sorting arrangements were not perfect". Chappells promised to rearrange the seats to give more room and did so within the year; the seating capacity of the hall was reduced to 2,400.Elkin (1944), p.19 War intervened before the question of refurbishing the decor could be addressed.

First World War and post-war

On the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, Newman, Wood and Speyer were obliged to consider the immediate future of concert-giving at the Queen's Hall. They discussed whether the Proms should continue as planned, and agreed to go ahead. However, within months anti-German feeling forced Speyer to leave the country and seek refuge in the U.S., and there was a campaign to ban all German music from concerts. Newman put out a statement declaring that German music would be played as planned: "The greatest examples of Music and Art are world possessions and unassailable even by the prejudices and passions of the hour".

When Speyer left Britain in 1915, Chappell's took on financial responsibility for the Queen's Hall concerts. The resident orchestra was renamed the New Queen's Hall Orchestra. Concerts continued throughout the war years, with fewer major new works than before, although there were nevertheless British premieres of pieces by Bartók, Stravinsky and Debussy. An historian of the Proms, Ateş Orga, wrote: "Concerts often had to be re-timed to coincide with the 'All Clear' between air raids. Falling bombs, shrapnel, anti-aircraft fire and the droning of

On the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, Newman, Wood and Speyer were obliged to consider the immediate future of concert-giving at the Queen's Hall. They discussed whether the Proms should continue as planned, and agreed to go ahead. However, within months anti-German feeling forced Speyer to leave the country and seek refuge in the U.S., and there was a campaign to ban all German music from concerts. Newman put out a statement declaring that German music would be played as planned: "The greatest examples of Music and Art are world possessions and unassailable even by the prejudices and passions of the hour".

When Speyer left Britain in 1915, Chappell's took on financial responsibility for the Queen's Hall concerts. The resident orchestra was renamed the New Queen's Hall Orchestra. Concerts continued throughout the war years, with fewer major new works than before, although there were nevertheless British premieres of pieces by Bartók, Stravinsky and Debussy. An historian of the Proms, Ateş Orga, wrote: "Concerts often had to be re-timed to coincide with the 'All Clear' between air raids. Falling bombs, shrapnel, anti-aircraft fire and the droning of Zeppelin

A Zeppelin is a type of rigid airship named after the German inventor Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin () who pioneered rigid airship development at the beginning of the 20th century. Zeppelin's notions were first formulated in 1874Eckener 1938, pp ...

s were ever threatening. But ood

The Ood are an alien species with telepathic abilities from the long-running science fiction series '' Doctor Who''. In the series' narrative, they live in the distant future (circa 42nd century).

The Ood are portrayed as a slave race, natura ...

kept things on the go and in the end had a very real part to play in boosting morale". The hall was hit by German air raids, but escaped with only minor damage. A member of Wood's choir later recalled a hit in the middle of a concert:

After the war, the Queen's Hall operated for a few years much as it had done before 1914, except for what Wood called "a somewhat disagreeable blue-green" new decor. New performers appeared, including Solomon

Solomon (; , ),, ; ar, سُلَيْمَان, ', , ; el, Σολομών, ; la, Salomon also called Jedidiah (Hebrew language, Hebrew: , Modern Hebrew, Modern: , Tiberian Hebrew, Tiberian: ''Yăḏīḏăyāh'', "beloved of Yahweh, Yah"), ...

, Lauritz Melchior

Lauritz Melchior (20 March 1890 – 18 March 1973) was a Danish-American opera singer. He was the preeminent Richard Wagner, Wagnerian tenor of the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s and has come to be considered the quintessence of his voice type. Late i ...

and Paul Hindemith

Paul Hindemith (; 16 November 189528 December 1963) was a German composer, music theorist, teacher, violist and conductor. He founded the Amar Quartet in 1921, touring extensively in Europe. As a composer, he became a major advocate of the ''Ne ...

. During the 1920s, however, the hall became the battleground between proponents and opponents of broadcasting. William Boosey, the head of Chappells, and effective proprietor of the Queen's Hall, was adamantly against the broadcasting of music by the recently established British Broadcasting Company

The British Broadcasting Company Ltd. (BBC) was a short-lived British commercial broadcasting company formed on 18 October 1922 by British and American electrical companies doing business in the United Kingdom. Licensed by the British Genera ...

(BBC). He decreed that no artist who had worked for the BBC would be allowed to perform at the Queen's Hall. This put performers in a dilemma; they wished to appear on the air without forfeiting the right to appear at Britain's most important musical venue. The hall became temporarily unable to attract many of the finest performers of the day.

In the middle of the impasse Newman's health failed, and he died in November 1926 after a brief illness. Wood wrote, "I feared everything would come to a standstill, for I had never so much as engaged an extra player without having discussed it with him first". Newman's assistant, W. W. Thompson, took over as manager of the orchestra and the concerts, but at this crucial point Chappells withdrew financial support for the Proms. After lengthy negotiations, the BBC took over from Chappells in 1927 as sponsor. The Proms were saved, and the hall continued to play host to celebrity concerts throughout the rest of the 1920s and the '30s, some promoted by the BBC, and others as hitherto by a range of choral societies, impresarios and orchestras. As Chappells owned the title "New Queen's Hall Orchestra", the resident orchestra had to change its name once again and was now known as Sir Henry J. Wood's Symphony Orchestra.Elkin (1944), p. 33

In the middle of the impasse Newman's health failed, and he died in November 1926 after a brief illness. Wood wrote, "I feared everything would come to a standstill, for I had never so much as engaged an extra player without having discussed it with him first". Newman's assistant, W. W. Thompson, took over as manager of the orchestra and the concerts, but at this crucial point Chappells withdrew financial support for the Proms. After lengthy negotiations, the BBC took over from Chappells in 1927 as sponsor. The Proms were saved, and the hall continued to play host to celebrity concerts throughout the rest of the 1920s and the '30s, some promoted by the BBC, and others as hitherto by a range of choral societies, impresarios and orchestras. As Chappells owned the title "New Queen's Hall Orchestra", the resident orchestra had to change its name once again and was now known as Sir Henry J. Wood's Symphony Orchestra.Elkin (1944), p. 33

Last years

In 1927, theBerlin Philharmonic Orchestra

The Berlin Philharmonic (german: Berliner Philharmoniker, links=no, italic=no) is a German orchestra based in Berlin. It is one of the most popular, acclaimed and well-respected orchestras in the world.

History

The Berlin Philharmonic was f ...

, under its conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler

Gustav Heinrich Ernst Martin Wilhelm Furtwängler ( , , ; 25 January 188630 November 1954) was a German conductor and composer. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest symphonic and operatic conductors of the 20th century. He was a major ...

, gave two concerts at the Queen's Hall. These, and later concerts by the same orchestra in 1928 and 1929, made obvious the comparatively poor standards of London orchestras. Both the BBC and Sir Thomas Beecham had ambitions to bring London's orchestral standards up to those of Berlin. After an early attempt at co-operation between the BBC and Beecham, they went their separate ways; the BBC established the BBC Symphony Orchestra

The BBC Symphony Orchestra (BBC SO) is a British orchestra based in London. Founded in 1930, it was the first permanent salaried orchestra in London, and is the only one of the city's five major symphony orchestras not to be self-governing. T ...

under Adrian Boult, and Beecham, together with Malcolm Sargent

Sir Harold Malcolm Watts Sargent (29 April 1895 – 3 October 1967) was an English conductor, organist and composer widely regarded as Britain's leading conductor of choral works. The musical ensembles with which he was associated include ...

, founded the London Philharmonic Orchestra

The London Philharmonic Orchestra (LPO) is one of five permanent symphony orchestras based in London. It was founded by the conductors Sir Thomas Beecham and Malcolm Sargent in 1932 as a rival to the existing London Symphony and BBC Symphony ...

.

Both orchestras made their debuts with concerts at the Queen's Hall. The BBC orchestra gave its first concert on 22 October 1930, conducted by Boult in a programme of music by Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, polemicist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most op ...

, Brahms

Johannes Brahms (; 7 May 1833 – 3 April 1897) was a German composer, pianist, and conductor of the mid-Romantic period. Born in Hamburg into a Lutheran family, he spent much of his professional life in Vienna. He is sometimes grouped with ...

, Saint-Saëns and Ravel

Joseph Maurice Ravel (7 March 1875 – 28 December 1937) was a French composer, pianist and conductor. He is often associated with Impressionism along with his elder contemporary Claude Debussy, although both composers rejected the term. In ...

. The reviews of the new orchestra were enthusiastic. ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'' commented on its "virtuosity" and of Boult's "superb" conducting. ''The Musical Times

''The Musical Times'' is an academic journal of classical music edited and produced in the United Kingdom and currently the oldest such journal still being published in the country.

It was originally created by Joseph Mainzer in 1842 as ''Mainze ...

'' commented, "The boast of the B.B.C. that it intended to get together a first-class orchestra was not an idle one", and spoke of "exhilaration" at the playing. The London Philharmonic made its debut on 7 October 1932, conducted by Beecham. After the first item, Berlioz's '' Roman Carnival Overture'', the audience went wild, some of them standing on their seats to clap and shout. During the next eight years, the orchestra appeared nearly a hundred times at the Queen's Hall.Jefferson, p. 89 There was no role for the old resident orchestra, many of whose members had been engaged by the BBC, and in 1930 it disbanded.

With orchestral standards now of unprecedented excellence, eminent musicians from Europe and the U.S. were eager to perform at the Queen's Hall. Among the guest conductors at the hall in the 1930s were Serge Koussevitzky, Willem Mengelberg

Joseph Wilhelm Mengelberg (28 March 1871 – 21 March 1951) was a Dutch conductor, famous for his performances of Beethoven, Brahms, Mahler and Strauss with the Concertgebouw Orchestra in Amsterdam. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest s ...

, Arturo Toscanini

Arturo Toscanini (; ; March 25, 1867January 16, 1957) was an Italian conductor. He was one of the most acclaimed and influential musicians of the late 19th and early 20th century, renowned for his intensity, his perfectionism, his ear for orch ...

, Bruno Walter

Bruno Walter (born Bruno Schlesinger, September 15, 1876February 17, 1962) was a German-born conductor, pianist and composer. Born in Berlin, he escaped Nazi Germany in 1933, was naturalised as a French citizen in 1938, and settled in the U ...

and Felix Weingartner

Paul Felix Weingartner, Edler von Münzberg (2 June 1863 – 7 May 1942) was an Austrian conductor, composer and pianist.

Life and career

Weingartner was born in Zara, Dalmatia, Austria-Hungary (now Zadar, Croatia), to Austrian parents. ...

. Composer-conductors included Richard Strauss and Anton Webern

Anton Friedrich Wilhelm von Webern (3 December 188315 September 1945), better known as Anton Webern (), was an Austrian composer and conductor whose music was among the most radical of its milieu in its sheer concision, even aphorism, and stead ...

. Some recordings made in the hall during this period have been reissued on CD.

Second World War

On the outbreak of the

On the outbreak of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

in September 1939, the BBC immediately put into effect its contingency plans to move much of its broadcasting away from London to places thought less at risk of bombing. Its musical department, including the BBC Symphony Orchestra, moved to Bristol. The BBC withdrew not only the players, but financial support from the Proms.Morrison, pp. 89–90 Wood determined that the 1940 season would nevertheless go ahead. The Royal Philharmonic Society and a private entrepreneur, Keith Douglas, agreed to back an eight-week season, and the London Symphony Orchestra was engaged. The concerts continued through air raids, and audiences often stayed in the hall until early morning, with musical entertainments continuing after the concerts had finished. The season was curtailed after four weeks, when intense bombing forced the Queen's Hall to close. The last Prom given at the Queen's Hall was on 7 September 1940. On 8 December doors and windows of the hall were blown out by blast. After temporary repairs, concerts were continued; after further damage on 6 April 1941 repairs were again quickly made, and the hall re-opened within days.

Enigma Variations

Edward Elgar composed his ''Variations on an Original Theme'', Op. 36, popularly known as the ''Enigma Variations'', between October 1898 and February 1899. It is an orchestral work comprising fourteen variations on an original theme.

Elgar ...

'' and ''The Dream of Gerontius

''The Dream of Gerontius'', Op. 38, is a work for voices and orchestra in two parts composed by Edward Elgar in 1900, to text from the poem by John Henry Newman. It relates the journey of a pious man's soul from his deathbed to his judgment b ...

''. The soloists were Muriel Brunskill

Muriel Lucy Brunskill (18 December 1899 – 18 February 1980) was an English contralto of the mid-twentieth century. Her career included concert, operatic and recital performance from the early 1920s until the 1950s. She worked with many of the ...

, Webster Booth

Webster Booth (21 January 1902 – 21 June 1984) was an English tenor, best remembered as the duettist partner of Anne Ziegler. He was also one of the finest tenors of his generation and was a distinguished oratorio soloist.

He was a chorister ...

and Ronald Stear, with the London Philharmonic and the Royal Choral Society. This concert, the last given at the hall, comprised in the view of ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'' "performances of real distinction". That night there was an intensive air raid in which the chamber of the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

and many other buildings were destroyed, and the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

and Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

were seriously damaged. A single incendiary bomb

Incendiary weapons, incendiary devices, incendiary munitions, or incendiary bombs are weapons designed to start fires or destroy sensitive equipment using fire (and sometimes used as anti-personnel weaponry), that use materials such as napalm, t ...

hit the Queen's Hall, and the auditorium was completely gutted by fire beyond any hope of replacement. The building was a smouldering ruin in heaps of rubble; the London Philharmonic lost thousands of pounds' worth of instruments. All that remained intact on the site was a bronze bust of Wood retrieved from the debris. Concerts continued in London at the Royal Albert Hall

The Royal Albert Hall is a concert hall on the northern edge of South Kensington, London. One of the UK's most treasured and distinctive buildings, it is held in trust for the nation and managed by a registered charity which receives no govern ...

and other venues. The Proms were relocated to the Albert Hall, which remains their principal venue. In 1951, the Royal Festival Hall was opened and succeeded the Queen's Hall as the main London venue for symphony concerts other than the Proms.

It was reported in late 1946 that the Commissioners of Crown Lands had increased the site's ground rent from £850 to £8,000, setting back the possibility of re-building the hall, or of building a new Henry Wood Concert Hall. In 1954 the government set up a committee, chaired by Lord Robbins

Lionel Charles Robbins, Baron Robbins, (22 November 1898 – 15 May 1984) was a British economist, and prominent member of the economics department at the London School of Economics (LSE). He is known for his leadership at LSE, his proposed def ...

with Sir Adrian Boult among its members, to examine the practicability of rebuilding the hall. The committee reported that "on musical grounds and in the interest of the general cultural life of the community" it was desirable to replace the hall, but it was doubtful whether there was a potential demand that would enable it to run without "seriously subtracting from the audiences of subsidised halls already in existence". From 1982, London had a second hall large enough for symphony concerts, in the Barbican Centre

The Barbican Centre is a performing arts centre in the Barbican Estate of the City of London and the largest of its kind in Europe. The centre hosts classical and contemporary music concerts, theatre performances, film screenings and art exhi ...

.

The former site of the Queen's Hall was redeveloped by the freeholder, the Crown Estate

The Crown Estate is a collection of lands and holdings in the United Kingdom belonging to the British monarch as a corporation sole, making it "the sovereign's public estate", which is neither government property nor part of the monarch's priva ...

. It is now occupied by the Saint Georges Hotel. In 2004, Richard Morrison wrote of the Queen's Hall:

The site is now marked by a commemorative plaque, which was unveiled in November 2000, by Sir Andrew Davis

Sir Andrew Frank Davis (born 2 February 1944) is an English conductor. He is conductor laureate of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, and the BBC Symphony Orchestra.

Early life and education

Born in Ashridge ...

, chief conductor of the BBC Symphony Orchestra

The BBC Symphony Orchestra (BBC SO) is a British orchestra based in London. Founded in 1930, it was the first permanent salaried orchestra in London, and is the only one of the city's five major symphony orchestras not to be self-governing. T ...

.City of Westminster green plaques

Notes, references and sources

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

NQHO history

at the

Robert Farnon

Robert Joseph Farnon CM (24 July 191723 April 2005) was a Canadian-born composer, conductor, musical arranger and trumpet player. As well as being a composer of original works (often in the light music genre), he was commissioned by film and ...

SocietyNQHO and Queen's Hall history

at New Queen's Hall Orchestra official website (archived) {{Coord, 51, 31, 5, N, 0, 8, 33, W, type:landmark, display=title Former concert halls in London Former buildings and structures in the City of Westminster Charles J. Phipps buildings 1893 establishments in England 1941 disestablishments in England Music venues completed in 1893 Demolished buildings and structures in England