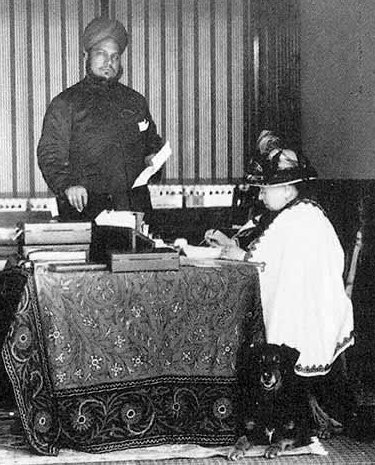

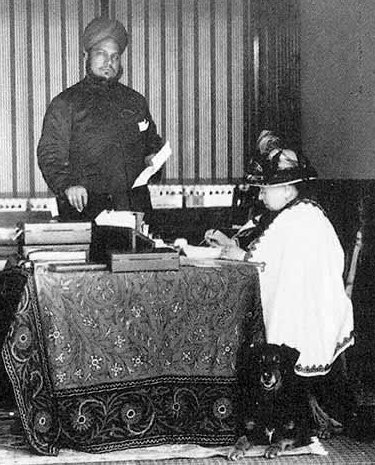

Queen Victoria (Elliott on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was

Victoria later described her childhood as "rather melancholy". Her mother was extremely protective, and Victoria was raised largely isolated from other children under the so-called " Kensington System", an elaborate set of rules and protocols devised by the Duchess and her ambitious and domineering

Victoria later described her childhood as "rather melancholy". Her mother was extremely protective, and Victoria was raised largely isolated from other children under the so-called " Kensington System", an elaborate set of rules and protocols devised by the Duchess and her ambitious and domineering  By 1836, Victoria's maternal uncle Leopold, who had been King of the Belgians since 1831, hoped to marry her to

By 1836, Victoria's maternal uncle Leopold, who had been King of the Belgians since 1831, hoped to marry her to

Victoria turned 18 on 24 May 1837, and a

Victoria turned 18 on 24 May 1837, and a

Although Victoria was now queen, as an unmarried young woman she was required by

Although Victoria was now queen, as an unmarried young woman she was required by  On 29 May 1842, Victoria was riding in a carriage along

On 29 May 1842, Victoria was riding in a carriage along  In 1845, Ireland was hit by a

In 1845, Ireland was hit by a  In 1853, Victoria gave birth to her eighth child, Leopold, with the aid of the new anaesthetic,

In 1853, Victoria gave birth to her eighth child, Leopold, with the aid of the new anaesthetic,  On 14 January 1858, an Italian refugee from Britain called

On 14 January 1858, an Italian refugee from Britain called

On 2 March 1882,

On 2 March 1882,  Victoria was pleased when Gladstone resigned in 1885 after his budget was defeated. She thought his government was "the worst I have ever had", and blamed him for the death of Charles George Gordon, General Gordon during the Siege of Khartoum. Gladstone was replaced by Lord Salisbury. Salisbury's government only lasted a few months, however, and Victoria was forced to recall Gladstone, whom she referred to as a "half crazy & really in many ways ridiculous old man". Gladstone attempted to pass Government of Ireland Bill 1886, a bill granting Ireland home rule, but to Victoria's glee it was defeated. In 1886 United Kingdom general election, the ensuing election, Gladstone's party lost to Salisbury's and the government switched hands again.

Victoria was pleased when Gladstone resigned in 1885 after his budget was defeated. She thought his government was "the worst I have ever had", and blamed him for the death of Charles George Gordon, General Gordon during the Siege of Khartoum. Gladstone was replaced by Lord Salisbury. Salisbury's government only lasted a few months, however, and Victoria was forced to recall Gladstone, whom she referred to as a "half crazy & really in many ways ridiculous old man". Gladstone attempted to pass Government of Ireland Bill 1886, a bill granting Ireland home rule, but to Victoria's glee it was defeated. In 1886 United Kingdom general election, the ensuing election, Gladstone's party lost to Salisbury's and the government switched hands again.

In 1887, the

In 1887, the  On 23 September 1896, Victoria surpassed her grandfather George III as the List of monarchs in Britain by length of reign, longest-reigning monarch in British history. The Queen requested that any special celebrations be delayed until 1897, to coincide with Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria, her Diamond Jubilee, which was made a festival of the British Empire at the suggestion of the Secretary of State for the Colonies, Colonial Secretary, Joseph Chamberlain. The prime ministers of all the self-governing Dominions were invited to London for the festivities. One reason for including the prime ministers of the Dominions and excluding foreign heads of state was to avoid having to invite Victoria's grandson Wilhelm II, who, it was feared, might cause trouble at the event.

The Queen's Diamond Jubilee procession on 22 June 1897 followed a route six miles long through London and included troops from all over the empire. The procession paused for an open-air service of thanksgiving held outside St Paul's Cathedral, throughout which Victoria sat in her open carriage, to avoid her having to climb the steps to enter the building. The celebration was marked by vast crowds of spectators and great outpourings of affection for the 78-year-old Queen.

On 23 September 1896, Victoria surpassed her grandfather George III as the List of monarchs in Britain by length of reign, longest-reigning monarch in British history. The Queen requested that any special celebrations be delayed until 1897, to coincide with Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria, her Diamond Jubilee, which was made a festival of the British Empire at the suggestion of the Secretary of State for the Colonies, Colonial Secretary, Joseph Chamberlain. The prime ministers of all the self-governing Dominions were invited to London for the festivities. One reason for including the prime ministers of the Dominions and excluding foreign heads of state was to avoid having to invite Victoria's grandson Wilhelm II, who, it was feared, might cause trouble at the event.

The Queen's Diamond Jubilee procession on 22 June 1897 followed a route six miles long through London and included troops from all over the empire. The procession paused for an open-air service of thanksgiving held outside St Paul's Cathedral, throughout which Victoria sat in her open carriage, to avoid her having to climb the steps to enter the building. The celebration was marked by vast crowds of spectators and great outpourings of affection for the 78-year-old Queen.

Through Victoria's reign, the gradual establishment of a modern constitutional monarchy in Britain continued. Reforms of the voting system increased the power of the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons at the expense of the House of Lords and the monarch. In 1867, Walter Bagehot wrote that the monarch only retained "the right to be consulted, the right to encourage, and the right to warn". As Victoria's monarchy became more symbolic than political, it placed a strong emphasis on morality and family values, in contrast to the sexual, financial and personal scandals that had been associated with previous members of the House of Hanover and which had discredited the monarchy. The concept of the "family monarchy", with which the burgeoning middle classes could identify, was solidified.

Through Victoria's reign, the gradual establishment of a modern constitutional monarchy in Britain continued. Reforms of the voting system increased the power of the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons at the expense of the House of Lords and the monarch. In 1867, Walter Bagehot wrote that the monarch only retained "the right to be consulted, the right to encourage, and the right to warn". As Victoria's monarchy became more symbolic than political, it placed a strong emphasis on morality and family values, in contrast to the sexual, financial and personal scandals that had been associated with previous members of the House of Hanover and which had discredited the monarchy. The concept of the "family monarchy", with which the burgeoning middle classes could identify, was solidified.

Victoria's youngest son, Leopold, was affected by the blood-clotting disease haemophilia B and at least two of her five daughters, Alice and Beatrice, were carriers. Haemophilia in European royalty, Royal haemophiliacs descended from Victoria included her great-grandsons, Alexei Nikolaevich, Tsarevich of Russia; Alfonso, Prince of Asturias (1907–1938), Alfonso, Prince of Asturias; and Infante Gonzalo of Spain. The presence of the disease in Victoria's descendants, but not in her ancestors, led to Legitimacy of Queen Victoria, modern speculation that her true father was not the Duke of Kent, but a haemophiliac. There is no documentary evidence of a haemophiliac in connection with Victoria's mother, and as male carriers always had the disease, even if such a man had existed he would have been seriously ill. It is more likely that the mutation arose spontaneously because Victoria's father was over 50 at the time of her conception and haemophilia arises more frequently in the children of older fathers. Spontaneous mutations account for about a third of cases.

Victoria's youngest son, Leopold, was affected by the blood-clotting disease haemophilia B and at least two of her five daughters, Alice and Beatrice, were carriers. Haemophilia in European royalty, Royal haemophiliacs descended from Victoria included her great-grandsons, Alexei Nikolaevich, Tsarevich of Russia; Alfonso, Prince of Asturias (1907–1938), Alfonso, Prince of Asturias; and Infante Gonzalo of Spain. The presence of the disease in Victoria's descendants, but not in her ancestors, led to Legitimacy of Queen Victoria, modern speculation that her true father was not the Duke of Kent, but a haemophiliac. There is no documentary evidence of a haemophiliac in connection with Victoria's mother, and as male carriers always had the disease, even if such a man had existed he would have been seriously ill. It is more likely that the mutation arose spontaneously because Victoria's father was over 50 at the time of her conception and haemophilia arises more frequently in the children of older fathers. Spontaneous mutations account for about a third of cases.

Queen Victoria

at the official website of the British monarchy

Queen Victoria

at the official website of the Royal Collection Trust

Queen Victoria

at BBC Teach *

Queen Victoria's Journals

online from the Royal Archive and Bodleian Library * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Victoria, Queen Queen Victoria, 1819 births 1901 deaths 19th-century British monarchs 20th-century British monarchs 19th-century queens regnant 20th-century queens regnant 19th-century British letter writers 20th-century British letter writers 19th-century British diarists 19th-century British women writers 20th-century British diarists 20th-century British women writers British people of German descent British women diarists Monarchs of the United Kingdom Monarchs of the Isle of Man Monarchs of Australia Heads of state of Canada Queens regnant in the British Isles House of Hanover Hanoverian princesses House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (United Kingdom) Empresses regnant in Asia Indian empresses British royal memoirists Founders of English schools and colleges People associated with the Royal National College for the Blind People from Kensington Writers from the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea Female critics of feminism Heirs presumptive to the British throne Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Immaculate Conception of Vila Viçosa Dames of the Order of Saint Isabel Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour Grand Crosses of the Order of St. Sava Recipients of the Order of the Cross of Takovo Articles containing video clips

Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

There have been 13 British monarchs since the political union of the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of Scotland on 1 May 1707. England and Scotland had been in personal union since 24 March 1603; while the style, "King of Great Britain" fi ...

from 20 June 1837 until her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days, which was longer than those of any of her predecessors, constituted the Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the reign of Queen Victoria, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. Slightly different definitions are sometimes used. The era followed the ...

. It was a period of industrial, political, scientific, and military change within the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

, and was marked by a great expansion of the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

. In 1876, the British parliament

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, and may also legislate for the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of ...

voted to grant her the additional title of Empress of India

Emperor (or Empress) of India was a title used by British monarchs from 1 May 1876 (with the Royal Titles Act 1876) to 22 June 1948 Royal Proclamation of 22 June 1948, made in accordance with thIndian Independence Act 1947, 10 & 11 GEO. 6. C ...

.

Victoria was the daughter of Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn

Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn (Edward Augustus; 2 November 1767 – 23 January 1820) was the fourth son and fifth child of King George III and Queen Charlotte. His only child, Queen Victoria, Victoria, became Queen of the United Ki ...

(the fourth son of King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland, Ireland from 25 October 1760 until his death in 1820. The Acts of Union 1800 unified Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and ...

), and Princess Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld

Princess Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld (Marie Louise Victoire; 17 August 1786 – 16 March 1861), later Princess of Leiningen and subsequently Duchess of Kent and Strathearn, was a German princess and the mother of Queen Victoria of the ...

. After the deaths of her father and grandfather in 1820, she was raised under close supervision by her mother and her comptroller

A comptroller (pronounced either the same as ''controller'' or as ) is a management-level position responsible for supervising the quality of accountancy, accounting and financial reporting of an organization. A financial comptroller is a senior- ...

, John Conroy

Sir John Ponsonby Conroy, 1st Baronet, KCH (21 October 1786 – 2 March 1854) was a British military officer best known for serving as comptroller to the Duchess of Kent and her young daughter, the future Queen Victoria. Born in Wales to Iri ...

. She inherited the throne aged 18 after her father's three elder brothers died without surviving legitimate issue. Victoria, a constitutional monarch

Constitutional monarchy, also known as limited monarchy, parliamentary monarchy or democratic monarchy, is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in making decisions. ...

, attempted privately to influence government policy and ministerial appointments; publicly, she became a national icon who was identified with strict standards of personal morality.

Victoria married her first cousin, Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (Franz August Karl Albert Emanuel; 26 August 1819 – 14 December 1861) was the husband of Queen Victoria. As such, he was consort of the British monarch from Wedding of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, th ...

, in 1840. Their nine children married into royal and noble families across the continent, earning Victoria the sobriquet

A sobriquet ( ) is a descriptive nickname, sometimes assumed, but often given by another. A sobriquet is distinct from a pseudonym in that it is typically a familiar name used in place of a real name without the need for explanation; it may beco ...

"grandmother of Europe

The sobriquet grandmother of Europe has been given to various women, primarily female sovereigns who are the ascendant of many members of European nobility and royalty, as well as women who made important contributions to Europe.

Royalty

* Elean ...

". After Albert's death in 1861, Victoria plunged into deep mourning and avoided public appearances. As a result of her seclusion, British republicanism

Republicanism in the United Kingdom is the political movement that seeks to replace the United Kingdom's monarchy with a republic. Supporters of the movement, called republicans, support alternative forms of governance to a monarchy, such as an ...

temporarily gained strength, but in the latter half of her reign, her popularity recovered. Her Golden and Diamond

Diamond is a Allotropes of carbon, solid form of the element carbon with its atoms arranged in a crystal structure called diamond cubic. Diamond is tasteless, odourless, strong, brittle solid, colourless in pure form, a poor conductor of e ...

jubilee

A jubilee is often used to refer to the celebration of a particular anniversary of an event, usually denoting the 25th, 40th, 50th, 60th, and the 70th anniversary. The term comes from the Hebrew Bible (see, "Old Testament"), initially concerning ...

s were times of public celebration. Victoria died at Osborne House

Osborne House is a former royal residence in East Cowes, Isle of Wight, United Kingdom. The house was built between 1845 and 1851 for Queen Victoria and Prince Albert as a summer home and rural retreat. Albert designed the house in the style ...

on the Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight (Help:IPA/English, /waɪt/ Help:Pronunciation respelling key, ''WYTE'') is an island off the south coast of England which, together with its surrounding uninhabited islets and Skerry, skerries, is also a ceremonial county. T ...

, at the age of 81. The last British monarch

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the form of government used by the United Kingdom by which a hereditary monarch reigns as the head of state, with their powers regulated by the British con ...

of the House of Hanover

The House of Hanover ( ) is a European royal house with roots tracing back to the 17th century. Its members, known as Hanoverians, ruled Hanover, Great Britain, Ireland, and the British Empire at various times during the 17th to 20th centurie ...

, she was succeeded by her son Edward VII

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until Death and state funeral of Edward VII, his death in 1910.

The second child ...

of the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

The House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha ( ; ) is a European royal house of German origin. It takes its name from its oldest domain, the Ernestine duchy of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, and its members later sat on the thrones of Belgium, Bulgaria, Portugal ...

.

Early life

Birth and ancestry

Victoria's father wasPrince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn

Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn (Edward Augustus; 2 November 1767 – 23 January 1820) was the fourth son and fifth child of King George III and Queen Charlotte. His only child, Queen Victoria, Victoria, became Queen of the United Ki ...

, the fourth son of King George III and Queen Charlotte

Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (Sophia Charlotte; 19 May 1744 – 17 November 1818) was Queen of Great Britain and Ireland as the wife of King George III from their marriage on 8 September 1761 until her death in 1818. The Acts of Un ...

. Until 1817, King George's only legitimate grandchild was Edward's niece Princess Charlotte of Wales Princess Charlotte of Wales may refer to:

* Princess Charlotte of Wales (1796–1817) (Charlotte Augusta), the only child of George, Prince of Wales, later King George IV of the United Kingdom

** ''Princess Charlotte of Wales'' (ship), an East In ...

, the daughter of George, Prince Regent (who would become George IV). Princess Charlotte's death in 1817 precipitated a succession crisis A succession crisis is a crisis that arises when an order of succession fails, for example when a monarch dies without an indisputable heir. It may result in a war of succession.

Examples include (see List of wars of succession):

* The Wars of Th ...

that brought pressure on Prince Edward and his unmarried brothers to marry and have children. In 1818, the Duke of Kent married Princess Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld

Princess Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld (Marie Louise Victoire; 17 August 1786 – 16 March 1861), later Princess of Leiningen and subsequently Duchess of Kent and Strathearn, was a German princess and the mother of Queen Victoria of the ...

, a widowed German princess with two children—Carl Carl may refer to:

*Carl, Georgia, city in USA

*Carl, West Virginia, an unincorporated community

*Carl (name), includes info about the name, variations of the name, and a list of people with the name

*Carl², a TV series

* "Carl", an episode of tel ...

(1804–1856) and Feodora (1807–1872)—by her first marriage to Emich Carl, 2nd Prince of Leiningen. Her brother Leopold

Leopold may refer to:

People

* Leopold (given name), including a list of people named Leopold or Léopold

* Leopold (surname)

Fictional characters

* Leopold (''The Simpsons''), Superintendent Chalmers' assistant on ''The Simpsons''

* Leopold B ...

was Princess Charlotte's widower and later the first king of Belgium

The monarchy of Belgium is the constitutional and hereditary institution of the monarchical head of state of the Kingdom of Belgium. As a popular monarchy, the Belgian monarch uses the title king/queen of the Belgians and serves as the ...

. The Duke and Duchess of Kent's only child, Victoria was born at 4:15 a.m. on Monday, 24 May 1819 at Kensington Palace

Kensington Palace is a royal residence situated within Kensington Gardens in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea in London, England. It has served as a residence for the British royal family since the 17th century and is currently the ...

in London.

Victoria was christened privately by the Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the Primus inter pares, ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the bishop of the diocese of Canterbury. The first archbishop ...

, Charles Manners-Sutton

Charles Manners-Sutton (né Manners; 17 February 1755 – 21 July 1828) was a British clergyman in the Church of England who served as Archbishop of Canterbury from 1805 to 1828.

Life

Manners-Sutton was the fourth son of Lord George Manners ...

, on 24 June 1819 in the Cupola Room at Kensington Palace. She was baptised ''Alexandrina'' after one of her godparents, Tsar Alexander I of Russia

Alexander I (, ; – ), nicknamed "the Blessed", was Emperor of Russia from 1801, the first king of Congress Poland from 1815, and the grand duke of Finland from 1809 to his death in 1825. He ruled Russian Empire, Russia during the chaotic perio ...

, and ''Victoria'', after her mother. Additional names proposed by her parents—Georgina (or Georgiana), Charlotte, and Augusta—were dropped on the instructions of the Prince Regent.

At birth, Victoria was fifth in the line of succession after the four eldest sons of George III: George, Prince Regent (later George IV); Frederick, Duke of York

Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany (Frederick Augustus; 16 August 1763 – 5 January 1827) was the second son of George III, King of the United Kingdom and Hanover, and his consort Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. A soldier by professi ...

; William, Duke of Clarence (later William IV); and Victoria's father, Edward, Duke of Kent. Prince George had no surviving children, and Prince Frederick had no children; further, both were estranged from their wives, who were both past child-bearing age, so the two eldest brothers were unlikely to have any further legitimate children. William married in 1818, in a joint ceremony with his brother Edward, but both of William's legitimate daughters died as infants. The first of these was Princess Charlotte, who was born and died on 27 March 1819, two months before Victoria was born. Victoria's father died in January 1820, when Victoria was less than a year old. A week later her grandfather died and was succeeded by his eldest son as George IV. Victoria was then third in line to the throne after Frederick and William. She was fourth in line while William's second daughter, Princess Elizabeth, lived, from 10 December 1820 to 4 March 1821.

Heir presumptive

Prince Frederick died in 1827, followed by George IV in 1830; their next surviving brother succeeded to the throne as William IV, and Victoria becameheir presumptive

An heir presumptive is the person entitled to inherit a throne, peerage, or other hereditary honour, but whose position can be displaced by the birth of a person with a better claim to the position in question. This is in contrast to an heir app ...

. The Regency Act 1830 made special provision for Victoria's mother to act as regent in case William died while Victoria was still a minor. King William distrusted the Duchess's capacity to be regent, and in 1836 he declared in her presence that he wanted to live until Victoria's 18th birthday, so that a regency

In a monarchy, a regent () is a person appointed to govern a state because the actual monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge their powers and duties, or the throne is vacant and a new monarch has not yet been dete ...

could be avoided.

Victoria later described her childhood as "rather melancholy". Her mother was extremely protective, and Victoria was raised largely isolated from other children under the so-called " Kensington System", an elaborate set of rules and protocols devised by the Duchess and her ambitious and domineering

Victoria later described her childhood as "rather melancholy". Her mother was extremely protective, and Victoria was raised largely isolated from other children under the so-called " Kensington System", an elaborate set of rules and protocols devised by the Duchess and her ambitious and domineering comptroller

A comptroller (pronounced either the same as ''controller'' or as ) is a management-level position responsible for supervising the quality of accountancy, accounting and financial reporting of an organization. A financial comptroller is a senior- ...

, Sir John Conroy, who was rumoured to be the Duchess's lover. The system prevented the princess from meeting people whom her mother and Conroy deemed undesirable (including most of her father's family), and was designed to render her weak and dependent upon them. The Duchess avoided the court because she was scandalised by the presence of King William's illegitimate children. Victoria shared a bedroom with her mother every night, studied with private tutors to a regular timetable, and spent her play-hours with her dolls and her King Charles Spaniel

The King Charles Spaniel (also known as the English Toy Spaniel) is a small dog breed of the spaniel type. In 1903, The Kennel Club combined four separate toy spaniel breeds under this single title. The other varieties merged into this breed wer ...

, Dash

The dash is a punctuation mark consisting of a long horizontal line. It is similar in appearance to the hyphen but is longer and sometimes higher from the baseline. The most common versions are the endash , generally longer than the hyphen ...

. Her lessons included French, German, Italian, and Latin, but she spoke only English at home. At age ten, she wrote and illustrated a children's story, ''The Adventures of Alice Laselles'', which was eventually published in 2015.

In 1830, the Duchess and Conroy took Victoria across the centre of England to visit the Malvern Hills

The Malvern Hills are in the English counties of Worcestershire, Herefordshire and a small area of northern Gloucestershire, dominating the surrounding countryside and the towns and villages of the district of Malvern. The highest summit af ...

, stopping at towns and great country houses

300px, Oxfordshire.html" ;"title="Blenheim Palace - Oxfordshire">Blenheim Palace - Oxfordshire

An English country house is a large house or mansion in the English countryside. Such houses were often owned by individuals who also owned a To ...

along the way. Similar journeys to other parts of England and Wales were taken in 1832, 1833, 1834 and 1835. To the King's annoyance, Victoria was enthusiastically welcomed in each of the stops. William compared the journeys to royal progress

The ceremonies and festivities accompanying a formal entry by a ruler or their representative into a city in the Middle Ages and early modern period in Europe were known as the royal entry, triumphal entry, or Joyous Entry. The entry centred on ...

es and was concerned that they portrayed Victoria as his rival rather than his heir presumptive. Victoria disliked the trips; the constant round of public appearances made her tired and ill, and there was little time for her to rest. She objected on the grounds of the King's disapproval, but her mother dismissed his complaints as motivated by jealousy and forced Victoria to continue the tours. At Ramsgate

Ramsgate is a seaside resort, seaside town and civil parish in the district of Thanet District, Thanet in eastern Kent, England. It was one of the great English seaside towns of the 19th century. In 2021 it had a population of 42,027. Ramsgate' ...

in October 1835, Victoria contracted a severe fever, which Conroy initially dismissed as a childish pretence. While Victoria was ill, Conroy and the Duchess unsuccessfully badgered her to make Conroy her private secretary. As a teenager, Victoria resisted persistent attempts by her mother and Conroy to appoint him to her staff. Once queen, she banned him from her presence, but he remained in her mother's household. By 1836, Victoria's maternal uncle Leopold, who had been King of the Belgians since 1831, hoped to marry her to

By 1836, Victoria's maternal uncle Leopold, who had been King of the Belgians since 1831, hoped to marry her to Prince Albert

Prince Albert most commonly refers to:

*Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (1819–1861), consort of Queen Victoria

*Albert II, Prince of Monaco (born 1958), present head of state of Monaco

Prince Albert may also refer to:

Royalty

* Alb ...

, the son of his brother Ernest I, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

Ernest I (; 2 January 178429 January 1844) served as the last sovereign duke of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld (as Ernest III) from 1806 to 1826 and the first sovereign duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha from 1826 to 1844. He was the father of Prince Albert, ...

. Leopold arranged for Victoria's mother to invite her Coburg relatives to visit her in May 1836, with the purpose of introducing Victoria to Albert. William IV, however, disapproved of any match with the Coburgs, and instead favoured the suit of Prince Alexander of the Netherlands

Prince Alexander of the Netherlands, Prince of Orange-Nassau (William ''Alexander'' Frederick Constantine Nicholas Michael, ; 2 August 1818 – 20 February 1848) was born at Soestdijk Palace, the second son to William II of the Netherlands, ...

, second son of the Prince of Orange. Victoria was aware of the various matrimonial plans and critically appraised a parade of eligible princes. According to her diary, she enjoyed Albert's company from the beginning. After the visit she wrote, " lbertis extremely handsome; his hair is about the same colour as mine; his eyes are large and blue, and he has a beautiful nose and a very sweet mouth with fine teeth; but the charm of his countenance is his expression, which is most delightful." Alexander, on the other hand, she described as "very plain".

Victoria wrote to King Leopold, whom she considered her "best and kindest adviser", to thank him "for the prospect of ''great'' happiness you have contributed to give me, in the person of dear Albert ... He possesses every quality that could be desired to render me perfectly happy. He is so sensible, so kind, and so good, and so amiable too. He has besides the most pleasing and delightful exterior and appearance you can possibly see." However at 17, Victoria, though interested in Albert, was not yet ready to marry. The parties did not undertake a formal engagement, but assumed that the match would take place in due time.

Accession and early reign

Victoria turned 18 on 24 May 1837, and a

Victoria turned 18 on 24 May 1837, and a regency

In a monarchy, a regent () is a person appointed to govern a state because the actual monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge their powers and duties, or the throne is vacant and a new monarch has not yet been dete ...

was avoided. Less than a month later, on 20 June 1837, William IV died at the age of 71, and Victoria became Queen of the United Kingdom. In her diary she wrote, "I was awoke at 6 o'clock by Mamma, who told me the Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the Primus inter pares, ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the bishop of the diocese of Canterbury. The first archbishop ...

and Lord Conyngham were here and wished to see me. I got out of bed and went into my sitting-room (only in my dressing gown) and ''alone'', and saw them. Lord Conyngham then acquainted me that my poor Uncle, the King, was no more, and had expired at 12 minutes past 2 this morning, and consequently that ''I'' am ''Queen''." Official documents prepared on the first day of her reign described her as Alexandrina Victoria, but the first name was withdrawn at her own wish and not used again.

Since 1714, Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* Great Britain, a large island comprising the countries of England, Scotland and Wales

* The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, a sovereign state in Europe comprising Great Britain and the north-eas ...

had shared a monarch with Hanover

Hanover ( ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the States of Germany, German state of Lower Saxony. Its population of 535,932 (2021) makes it the List of cities in Germany by population, 13th-largest city in Germany as well as the fourth-l ...

in Germany, but under Salic law

The Salic law ( or ; ), also called the was the ancient Frankish Civil law (legal system), civil law code compiled around AD 500 by Clovis I, Clovis, the first Frankish King. The name may refer to the Salii, or "Salian Franks", but this is deba ...

, women were excluded from the Hanoverian succession. While Victoria inherited the British throne, her father's unpopular younger brother, Ernest Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, became King of Hanover

The King of Hanover () was the official title of the head of state and Hereditary monarchy, hereditary ruler of the Kingdom of Hanover, beginning with the proclamation of List of British monarchs, King George III of the United Kingdom, as "King o ...

. He was Victoria's heir presumptive until she had a child.

At the time of Victoria's accession, the government was led by the Whig prime minister Lord Melbourne

Henry William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne (15 March 177924 November 1848) was a British Whig politician who served as the Home Secretary and twice as the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom.

His first premiership ended when he was dismissed ...

. He at once became a powerful influence on the politically inexperienced monarch, who relied on him for advice. Charles Greville supposed that the widowed and childless Melbourne was "passionately fond of her as he might be of his daughter if he had one", and Victoria probably saw him as a father figure. Her coronation took place on 28 June 1838 at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British m ...

. Over 400,000 visitors came to London for the celebrations. She became the first sovereign to take up residence at Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace () is a royal official residence, residence in London, and the administrative headquarters of the monarch of the United Kingdom. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is often at the centre of state occasions and r ...

and inherited the revenues of the duchies of Lancaster

Lancaster may refer to:

Lands and titles

*The County Palatine of Lancaster, a synonym for Lancashire

*Duchy of Lancaster, one of only two British royal duchies

*Duke of Lancaster

*Earl of Lancaster

*House of Lancaster, a British royal dynasty

...

and Cornwall

Cornwall (; or ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is also one of the Celtic nations and the homeland of the Cornish people. The county is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, ...

as well as being granted a civil list

A civil list is a list of individuals to whom money is paid by the government, typically for service to the state or as honorary pensions. It is a term especially associated with the United Kingdom, and its former colonies and dominions. It was ori ...

allowance of £385,000 per year. Financially prudent, she paid off her father's debts.

At the start of her reign Victoria was popular, but her reputation suffered in an 1839 court intrigue when one of her mother's ladies-in-waiting, Lady Flora Hastings, developed an abdominal growth that was widely rumoured to be an out-of-wedlock pregnancy by Sir John Conroy. Victoria believed the rumours. She hated Conroy, and despised "that odious Lady Flora", because she had conspired with Conroy and the Duchess in the Kensington System. At first, Lady Flora refused to submit to an intimate medical examination, until in mid-February she eventually acquiesced, and was found to be a virgin. Conroy, the Hastings family, and the opposition Tories

A Tory () is an individual who supports a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalist conservatism which upholds the established social order as it has evolved through the history of Great Britain. The T ...

organised a press campaign implicating the Queen in the spreading of false rumours about Lady Flora. When Lady Flora died in July, the post-mortem revealed a large tumour on her liver that had distended her abdomen. At public appearances, Victoria was hissed and jeered at as "Mrs. Melbourne".

In 1839, Melbourne resigned after Radicals

Radical (from Latin: ', root) may refer to:

Politics and ideology Politics

*Classical radicalism, the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe and Latin America in the 19th century

*Radical politics ...

and Tories (both of whom Victoria detested) voted against a bill to suspend the constitution of Jamaica

Jamaica is an island country in the Caribbean Sea and the West Indies. At , it is the third-largest island—after Cuba and Hispaniola—of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean. Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, west of Hispaniola (the is ...

. The bill removed political power from plantation owners who were resisting measures associated with the abolition of slavery

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was France in 1315, but it was later used in its colonies. T ...

. The Queen commissioned a Tory, Robert Peel

Sir Robert Peel, 2nd Baronet (5 February 1788 – 2 July 1850), was a British Conservative statesman who twice was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (1834–1835, 1841–1846), and simultaneously was Chancellor of the Exchequer (1834–183 ...

, to form a new ministry. At the time, it was customary for the prime minister to appoint members of the Royal Household, who were usually his political allies and their spouses. Many of the Queen's ladies of the bedchamber

Lady of the Bedchamber is the title of a lady-in-waiting holding the official position of personal attendant on a British queen regnant or queen consort. The position is traditionally held by the wife of a peer. A lady of the bedchamber would gi ...

were wives of Whigs, and Peel expected to replace them with wives of Tories. In what became known as the "bedchamber crisis

The Bedchamber crisis was a constitutional crisis that occurred in the United Kingdom between 1839 and 1841. It began after Whig politician William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne declared his intention to resign as Prime Minister of the United Ki ...

", Victoria, advised by Melbourne, objected to their removal. Peel refused to govern under the restrictions imposed by the Queen, and consequently resigned his commission, allowing Melbourne to return to office.

Marriage and public life

Although Victoria was now queen, as an unmarried young woman she was required by

Although Victoria was now queen, as an unmarried young woman she was required by social convention

A convention influences a set of agreed, stipulated, or generally accepted standards, social norms, or other criteria, often taking the form of a custom.

In physical sciences, numerical values (such as constants, quantities, or scales of measure ...

to live with her mother, despite their differences over the Kensington System and her mother's continued reliance on Conroy. The duchess was consigned to a remote apartment in Buckingham Palace, and Victoria often refused to see her. When Victoria complained to Melbourne that her mother's proximity promised "torment for many years", Melbourne sympathised but said it could be avoided by marriage, which Victoria called a "schocking alternative". Victoria showed interest in Albert's education for the future role he would have to play as her husband, but she resisted attempts to rush her into wedlock.

Victoria continued to praise Albert following his second visit in October 1839. They felt mutual affection and the queen proposed to him on 15 October 1839, just five days after he had arrived at Windsor. They were married on 10 February 1840, in the Chapel Royal

A chapel royal is an establishment in the British and Canadian royal households serving the spiritual needs of the sovereign and the royal family.

Historically, the chapel royal was a body of priests and singers that travelled with the monarc ...

of St James's Palace

St James's Palace is the most senior royal palace in London, England. The palace gives its name to the Court of St James's, which is the monarch's royal court, and is located in the City of Westminster. Although no longer the principal residence ...

, London. Victoria was love-struck. She spent the evening after their wedding lying down with a headache, but wrote ecstatically in her diary:

Albert became an important political adviser as well as the queen's companion, replacing Melbourne as the dominant influential figure in the first half of her life. Victoria's mother was evicted from the palace, to Ingestre House in Belgrave Square

Belgrave Square is a large 19th-century garden square in London. It is the centrepiece of Belgravia, and its architecture resembles the original scheme of property contractor Thomas Cubitt who engaged George Basevi for all of the terraces for ...

. After the death of Victoria's aunt Princess Augusta in 1840, the duchess was given both Clarence House

Clarence House is a royal residence on The Mall in the City of Westminster, London. It was built in 1825–1827, adjacent to St James's Palace, for the royal Duke of Clarence, the future King William IV.

The four-storey house is faced in ...

and Frogmore House

Frogmore House is a 17th-century English country house owned by the Crown Estate. It is a historic Grade I listed building. The house is located on the Frogmore estate, which is situated within the grounds of the Home Park in Windsor, Berksh ...

. Through Albert's mediation, relations between mother and daughter slowly improved.

During Victoria's first pregnancy in 1840, in the first few months of the marriage, 18-year-old Edward Oxford

Edward Oxford (19 April 1822 – 23 April 1900) was an English man who attempted to assassinate Queen Victoria in 1840. He was the first of seven unconnected people who tried to kill her between 1840 and 1882. Born and raised in Birmingham ...

attempted to assassinate her while she was riding in a carriage with Prince Albert on her way to visit her mother. Oxford fired twice, but either both bullets missed or, as he later claimed, the guns had no shot. He was tried for high treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its d ...

, found not guilty by reason of insanity

Not or NOT may also refer to:

Language

* Not, the general declarative form of "no", indicating a negation of a related statement that usually precedes

* ... Not!, a grammatical construction used as a contradiction, popularized in the early 1990 ...

, committed to an insane asylum indefinitely, and later sent to live in Australia. In the immediate aftermath of the attack, Victoria's popularity soared, mitigating residual discontent over the Hastings affair and the bedchamber crisis

The Bedchamber crisis was a constitutional crisis that occurred in the United Kingdom between 1839 and 1841. It began after Whig politician William Lamb, 2nd Viscount Melbourne declared his intention to resign as Prime Minister of the United Ki ...

. Her daughter, also named Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Queen Victoria (1819–1901), Queen of the United Kingdom and Empress of India

* Victoria (state), a state of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, Canada, a provincial capital

* Victoria, Seychelles, the capi ...

, was born on 21 November 1840. The queen hated being pregnant, viewed breast-feeding with disgust, and thought newborn babies were ugly. Nevertheless, over the following seventeen years, she and Albert had a further eight children: Albert Edward, Alice

Alice may refer to:

* Alice (name), most often a feminine given name, but also used as a surname

Literature

* Alice (''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland''), a character in books by Lewis Carroll

* ''Alice'' series, children's and teen books by ...

, Alfred

Alfred may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

*''Alfred J. Kwak'', Dutch-German-Japanese anime television series

* ''Alfred'' (Arne opera), a 1740 masque by Thomas Arne

* ''Alfred'' (Dvořák), an 1870 opera by Antonín Dvořák

*"Alfred (Interlu ...

, Helena

Helena may refer to:

People

*Helena (given name), a given name (including a list of people and characters with the name)

*Katri Helena (born 1945), Finnish singer

* Saint Helena (disambiguation), this includes places

Places

Greece

* Helena ...

, Louise, Arthur

Arthur is a masculine given name of uncertain etymology. Its popularity derives from it being the name of the legendary hero King Arthur.

A common spelling variant used in many Slavic, Romance, and Germanic languages is Artur. In Spanish and Ital ...

, Leopold

Leopold may refer to:

People

* Leopold (given name), including a list of people named Leopold or Léopold

* Leopold (surname)

Fictional characters

* Leopold (''The Simpsons''), Superintendent Chalmers' assistant on ''The Simpsons''

* Leopold B ...

and Beatrice.

The household was largely run by Victoria's childhood governess, Baroness Louise Lehzen

Johanna Clara Louise, Baroness von Lehzen (3 October 17849 September 1870) was the governess and later companion to Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom.

Lehzen was born to a Lutheran pastor Joachim Friedrich Lehzen (1735-1800) and his wife, Ma ...

from Hanover

Hanover ( ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the States of Germany, German state of Lower Saxony. Its population of 535,932 (2021) makes it the List of cities in Germany by population, 13th-largest city in Germany as well as the fourth-l ...

. Lehzen had been a formative influence on Victoria and had supported her against the Kensington System. Albert, however, thought that Lehzen was incompetent and that her mismanagement threatened his daughter Victoria's health. After a furious row between Victoria and Albert over the issue, Lehzen was pensioned off in 1842, and Victoria's close relationship with her ended.

On 29 May 1842, Victoria was riding in a carriage along

On 29 May 1842, Victoria was riding in a carriage along The Mall, London

The Mall () is a ceremonial route and roadway in the City of Westminster, central London, that travels between Buckingham Palace at its western end and Trafalgar Square via Admiralty Arch to the east. Along the north side of The Mall is gre ...

, when John Francis aimed a pistol at her, but the gun did not fire. The assailant escaped; the following day, Victoria drove the same route, though faster and with a greater escort, in a deliberate attempt to bait Francis into taking a second aim and catch him in the act. As expected, Francis shot at her, but he was seized by plainclothes policemen, and convicted of high treason. On 3 July, two days after Francis's death sentence was commuted to transportation for life

Penal transportation (or simply transportation) was the relocation of convicted criminals, or other persons regarded as undesirable, to a distant place, often a colony, for a specified term; later, specifically established penal colonies becam ...

, John William Bean also tried to fire a pistol at the queen, but it was loaded only with paper and tobacco and had too little charge. Edward Oxford felt that the attempts were encouraged by his acquittal in 1840.Hibbert, p. 423; St Aubyn, p. 163 Bean was sentenced to 18 months in jail. In a similar attack in 1849, unemployed Irishman William Hamilton fired a powder-filled pistol at Victoria's carriage as it passed along Constitution Hill, London

Constitution Hill is a road in the City of Westminster in London. It connects the western end of The Mall (just in front of Buckingham Palace) with Hyde Park Corner, and is bordered by Buckingham Palace Gardens to the south, and Green Park to ...

. In 1850, the queen did sustain injury when she was assaulted by a possibly insane ex-army officer, Robert Pate. As Victoria was riding in a carriage, Pate struck her with his cane, crushing her bonnet and bruising her forehead. Both Hamilton and Pate were sentenced to seven years' transportation.

Melbourne's support in the House of Commons weakened through the early years of Victoria's reign, and in the 1841 general election the Whigs were defeated. Peel became prime minister, and the ladies of the bedchamber most associated with the Whigs were replaced.

In 1845, Ireland was hit by a

In 1845, Ireland was hit by a potato blight

''Phytophthora infestans'' is an oomycete or water mold, a fungus-like microorganism that causes the serious potato and tomato disease known as late blight or potato blight. Early blight, caused by '' Alternaria solani'', is also often called " ...

. In the next four years, over a million Irish people died and another million emigrated in what became known as the Great Famine. In Ireland, Victoria was labelled "The Famine Queen". In January 1847 she personally donated £2,000 (equivalent to between £230,000 and £8.5million in 2022) to the British Relief Association

The British Association for the Relief of Distress in Ireland and the Highlands of Scotland, known as the British Relief Association (BRA), was a private charity of the mid-19th century in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Establis ...

, more than any other individual famine relief donor, and supported the Maynooth Grant

The Maynooth Grant was a cash grant from the British government to a Catholic seminary in Ireland. In 1845, the Conservative Prime Minister, Sir Robert Peel, sought to improve the relationship between Catholic Ireland and Protestant Britain by i ...

to a Roman Catholic seminary in Ireland, despite Protestant opposition. The story that she donated only £5 in aid to the Irish, and on the same day gave the same amount to Battersea Dogs Home

Battersea Dogs & Cats Home (now known as Battersea) is an animal rescue centre for dogs and cats. Battersea rescues dogs and cats until their owner or a new one can be found. It is one of the UK's oldest and best known animal rescue centres. I ...

, was a myth generated towards the end of the 19th century.

By 1846, Peel's ministry faced a crisis involving the repeal of the Corn Laws

The Corn Laws were tariffs and other trade restrictions on imported food and corn enforced in the United Kingdom between 1815 and 1846. The word ''corn'' in British English denotes all cereal grains, including wheat, oats and barley. The la ...

. Many Tories—by then known also as Conservatives

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilizati ...

—were opposed to the repeal, but Peel, some Tories (the free-trade oriented liberal conservative

Liberal conservatism is a political ideology combining conservative policies with liberal stances, especially on economic issues but also on social and ethical matters, representing a brand of political conservatism strongly influenced by libe ...

"Peelite

The Peelites were a breakaway political faction of the British Conservative Party from 1846 to 1859. Initially led by Robert Peel, the former Prime Minister and Conservative Party leader in 1846, the Peelites supported free trade whilst the bulk ...

s"), most Whigs and Victoria supported it. Peel resigned in 1846, after the repeal narrowly passed, and was replaced by Lord John Russell

John Russell, 1st Earl Russell (18 August 1792 – 28 May 1878), known as Lord John Russell before 1861, was a British Whig and Liberal statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1846 to 1852 and again from 1865 to 186 ...

.

Internationally, Victoria took a keen interest in the improvement of relations between France and Britain. She made and hosted several visits between the British royal family and the House of Orleans, who were related by marriage through the Coburgs. In 1843 and 1845, she and Albert stayed with King Louis Philippe I

Louis Philippe I (6 October 1773 – 26 August 1850), nicknamed the Citizen King, was King of the French from 1830 to 1848, the penultimate monarch of France, and the last French monarch to bear the title "King". He abdicated from his throne ...

at Château d'Eu

The Château d'Eu () is a former royal residence in the town of Eu, in the Seine-Maritime department of France, in Normandy.

The Château d'Eu stands at the centre of the town and was built in the 16th century to replace an earlier one purpose ...

in Normandy; she was the first British or English monarch to visit a French monarch since the meeting of Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his Wives of Henry VIII, six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. ...

of England and Francis I of France

Francis I (; ; 12 September 1494 – 31 March 1547) was King of France from 1515 until his death in 1547. He was the son of Charles, Count of Angoulême, and Louise of Savoy. He succeeded his first cousin once removed and father-in-law Louis&nbs ...

on the Field of the Cloth of Gold

The Field of the Cloth of Gold (, ) was a summit meeting between King Henry VIII of England and King Francis I of France from 7 to 24 June 1520. Held at Balinghem, between Ardres in France and Guînes in the English Pale of Calais, it was a ...

in 1520. When Louis Philippe made a reciprocal trip in 1844, he became the first French king to visit a British sovereign. Louis Philippe was deposed in the revolutions of 1848

The revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the springtime of the peoples or the springtime of nations, were a series of revolutions throughout Europe over the course of more than one year, from 1848 to 1849. It remains the most widespre ...

, and fled to exile in England. At the height of a revolutionary scare in the United Kingdom in April 1848, Victoria and her family left London for the greater safety of Osborne House

Osborne House is a former royal residence in East Cowes, Isle of Wight, United Kingdom. The house was built between 1845 and 1851 for Queen Victoria and Prince Albert as a summer home and rural retreat. Albert designed the house in the style ...

, a private estate on the Isle of Wight that they had purchased in 1845 and redeveloped. Demonstrations by Chartists

Chartism was a working-class movement for political reform in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom that erupted from 1838 to 1857 and was strongest in 1839, 1842 and 1848. It took its name from the People's Charter of ...

and Irish nationalists

Irish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which, in its broadest sense, asserts that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. Since the mid-19th century, Irish nationalism has largely taken the form of cu ...

failed to attract widespread support, and the scare died down without any major disturbances. Victoria's first visit to Ireland in 1849 was a public relations success, but it had no lasting impact or effect on the growth of Irish nationalism.

Russell's ministry, though Whig, was not favoured by the queen. She found particularly offensive the Foreign Secretary, Lord Palmerston

Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston (20 October 1784 – 18 October 1865), known as Lord Palmerston, was a British statesman and politician who served as prime minister of the United Kingdom from 1855 to 1858 and from 1859 to 1865. A m ...

, who often acted without consulting the cabinet, the prime minister, or the queen. Victoria complained to Russell that Palmerston sent official dispatches to foreign leaders without her knowledge, but Palmerston was retained in office and continued to act on his own initiative, despite her repeated remonstrances. It was only in 1851 that Palmerston was removed after he announced the British government's approval of President Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon III (Charles-Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was President of France from 1848 to 1852 and then Emperor of the French from 1852 until his deposition in 1870. He was the first president, second emperor, and last ...

's coup in France without consulting the prime minister. The following year, President Bonaparte was declared Emperor Napoleon III, by which time Russell's administration had been replaced by a short-lived minority government led by Lord Derby

Edward George Geoffrey Smith-Stanley, 14th Earl of Derby (29 March 1799 – 23 October 1869), known as Lord Stanley from 1834 to 1851, was a British statesman and Conservative politician who served three times as Prime Minister of the United K ...

.

chloroform

Chloroform, or trichloromethane (often abbreviated as TCM), is an organochloride with the formula and a common solvent. It is a volatile, colorless, sweet-smelling, dense liquid produced on a large scale as a precursor to refrigerants and po ...

. She was so impressed by the relief it gave from the pain of childbirth that she used it again in 1857 at the birth of her ninth and final child, Beatrice, despite opposition from members of the clergy, who considered it against biblical teaching, and members of the medical profession, who thought it dangerous. Victoria may have had postnatal depression

Postpartum depression (PPD), also called perinatal depression, is a mood disorder which may be experienced by pregnant or postpartum women. Symptoms include extreme sadness, low energy, anxiety, crying episodes, irritability, and extreme cha ...

after many of her pregnancies. Letters from Albert to Victoria intermittently complain of her loss of self-control. For example, about a month after Leopold's birth Albert complained in a letter to Victoria about her "continuance of hysterics" over a "miserable trifle".

In early 1855, the government of Lord Aberdeen

George Hamilton-Gordon, 4th Earl of Aberdeen (28 January 178414 December 1860), styled Lord Haddo from 1791 to 1801, was a British statesman, diplomat and landowner, successively a Tory, Conservative and Peelite politician and specialist in fo ...

, who had replaced Derby, fell amidst recriminations over the poor management of British troops in the Crimean War

The Crimean War was fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the Second French Empire, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Kingdom of Sardinia (1720–1861), Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont fro ...

. Victoria approached both Derby and Russell to form a ministry, but neither had sufficient support, and Victoria was forced to appoint Palmerston as prime minister.

Napoleon III, Britain's closest ally as a result of the Crimean War, visited London in April 1855, and from 17 to 28 August the same year Victoria and Albert returned the visit. Napoleon III met the couple at Boulogne

Boulogne-sur-Mer (; ; ; or ''Bononia''), often called just Boulogne (, ), is a coastal city in Hauts-de-France, Northern France. It is a Subprefectures in France, sub-prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Pas-de-Calais. Boul ...

and accompanied them to Paris. They visited the (a successor to Albert's 1851 brainchild the Great Exhibition

The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, also known as the Great Exhibition or the Crystal Palace Exhibition (in reference to the temporary structure in which it was held), was an international exhibition that took ...

) and Napoleon I

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

's tomb at Les Invalides

The Hôtel des Invalides (; ), commonly called (; ), is a complex of buildings in the 7th arrondissement of Paris, France, containing museums and monuments, all relating to the military history of France, as well as a hospital and an old soldi ...

(to which his remains had only been returned in 1840), and were guests of honour at a 1,200-guest ball at the Palace of Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; ) is a former royal residence commissioned by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, Yvelines, Versailles, about west of Paris, in the Yvelines, Yvelines Department of Île-de-France, Île-de-France region in Franc ...

. This marked the first time that a reigning British monarch had been to Paris in over 400 years.

On 14 January 1858, an Italian refugee from Britain called

On 14 January 1858, an Italian refugee from Britain called Felice Orsini

Felice Orsini (; ; 10 December 1819 – 13 March 1858) was an Italian revolutionary and leader of the '' Carbonari'' who tried to assassinate Napoleon III, Emperor of the French.

Early life

Felice Orsini was born at Meldola in Romagna, th ...

attempted to assassinate Napoleon III with a bomb made in England. The ensuing diplomatic crisis destabilised the government, and Palmerston resigned. Derby was reinstated as prime minister. Victoria and Albert attended the opening of a new basin at the French military port of Cherbourg

Cherbourg is a former Communes of France, commune and Subprefectures in France, subprefecture located at the northern end of the Cotentin peninsula in the northwestern French departments of France, department of Manche. It was merged into the com ...

on 5 August 1858, in an attempt by Napoleon III to reassure Britain that his military preparations were directed elsewhere. On her return Victoria wrote to Derby reprimanding him for the poor state of the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

in comparison to the French Navy

The French Navy (, , ), informally (, ), is the Navy, maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the four military service branches of History of France, France. It is among the largest and most powerful List of navies, naval forces i ...

. Derby's ministry did not last long, and in June 1859 Victoria recalled Palmerston to office.

Eleven days after Orsini's assassination attempt in France, Victoria's eldest daughter married Prince Frederick William of Prussia in London. They had been betrothed since September 1855, when Princess Victoria was 14 years old; the marriage was delayed by the queen and her husband Albert until the bride was 17. The queen and Albert hoped that their daughter and son-in-law would be a liberalising influence in the enlarging Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

n state. The queen felt "sick at heart" to see her daughter leave England for Germany; "It really makes me shudder", she wrote to Princess Victoria in one of her frequent letters, "when I look round to all your sweet, happy, unconscious sisters, and think I must give them up too – one by one." Almost exactly a year later, the Princess gave birth to the queen's first grandchild, Wilhelm

Wilhelm may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* William Charles John Pitcher, costume designer known professionally as "Wilhelm"

* Wilhelm (name), a list of people and fictional characters with the given name or surname

Other uses

* Wilhe ...

, who would become the last German emperor.

Widowhood and isolation

In March 1861, Victoria's mother died, with Victoria at her side. Through reading her mother's papers, Victoria discovered that her mother had loved her deeply; she was heart-broken, and blamed Conroy and Lehzen for "wickedly" estranging her from her mother. To relieve his wife during her intense and deep grief, Albert took on most of her duties, despite being ill himself with chronic stomach trouble. In August, Victoria and Albert visited their son,Albert Edward, Prince of Wales

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until Death and state funeral of Edward VII, his death in 1910.

The second child ...

, who was attending army manoeuvres near Dublin, and spent a few days holidaying in Killarney

Killarney ( ; , meaning 'church of sloes') is a town in County Kerry, southwestern Republic of Ireland, Ireland. The town is on the northeastern shore of Lough Leane, part of Killarney National Park, and is home to St Mary's Cathedral, Killar ...

. In November, Albert was made aware of gossip that his son had slept with an actress in Ireland. Appalled, he travelled to Cambridge, where his son was studying, to confront him.

By the beginning of December, Albert was very unwell. He was diagnosed with typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known simply as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella enterica'' serotype Typhi bacteria, also called ''Salmonella'' Typhi. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often th ...

by William Jenner, and died on 14 December 1861. Victoria was devastated. She blamed her husband's death on worry over the Prince of Wales's philandering. He had been "killed by that dreadful business", she said. She entered a state of mourning

Mourning is the emotional expression in response to a major life event causing grief, especially loss. It typically occurs as a result of someone's death, especially a loved one.

The word is used to describe a complex of behaviors in which t ...

and wore black for the remainder of her life. She avoided public appearances and rarely set foot in London in the following years. Her seclusion earned her the nickname "widow of Windsor". Her weight increased through comfort eating, which reinforced her aversion to public appearances.

Victoria's self-imposed isolation from the public diminished the popularity of the monarchy, and encouraged the growth of the republican movement. She did undertake her official government duties, yet chose to remain secluded in her royal residences—Windsor Castle

Windsor Castle is a List of British royal residences, royal residence at Windsor, Berkshire, Windsor in the English county of Berkshire, about west of central London. It is strongly associated with the Kingdom of England, English and succee ...

, Osborne House, and the private estate in Scotland that she and Albert had acquired in 1847, Balmoral Castle

Balmoral Castle () is a large estate house in Aberdeenshire, Scotland, and a residence of the British royal family. It is near the village of Crathie, west of Ballater and west of Aberdeen.

The estate and its original castle were bought ...

. In March 1864, a protester stuck a notice on the railings of Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace () is a royal official residence, residence in London, and the administrative headquarters of the monarch of the United Kingdom. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is often at the centre of state occasions and r ...

that announced "these commanding premises to be let or sold in consequence of the late occupant's declining business". Her uncle Leopold wrote to her advising her to appear in public. She agreed to visit the gardens of the Royal Horticultural Society

The Royal Horticultural Society (RHS), founded in 1804 as the Horticultural Society of London, is the UK's leading gardening charity.

The RHS promotes horticulture through its five gardens at Wisley (Surrey), Hyde Hall (Essex), Harlow Carr ...

at Kensington

Kensington is an area of London in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, around west of Central London.

The district's commercial heart is Kensington High Street, running on an east–west axis. The north-east is taken up by Kensingt ...

and take a drive through London in an open carriage.

Through the 1860s, Victoria relied increasingly on a manservant from Scotland, John Brown John Brown most often refers to:

*John Brown (abolitionist) (1800–1859), American who led an anti-slavery raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in 1859

John Brown or Johnny Brown may also refer to:

Academia

* John Brown (educator) (1763–1842), Ir ...

. Rumours of a romantic connection and even a secret marriage appeared in print, and some referred to the Queen as "Mrs. Brown". The story of their relationship was the subject of the 1997 movie ''Mrs. Brown

''Mrs Brown'' (also released in cinemas as ''Her Majesty, Mrs Brown'') is a 1997 British drama film starring Judi Dench, Billy Connolly, Geoffrey Palmer, Antony Sher, and Gerard Butler in his film debut. It was written by Jeremy Brock and ...

''. A painting by Sir Edwin Henry Landseer

Sir Edwin Henry Landseer (7 March 1802 – 1 October 1873) was an English painter and sculptor, well known for his paintings of animals – particularly horses, dogs, and stags. His best-known work is the lion sculptures at the base of Nelso ...

depicting the Queen with Brown was exhibited at the Royal Academy

The Royal Academy of Arts (RA) is an art institution based in Burlington House in Piccadilly London, England. Founded in 1768, it has a unique position as an independent, privately funded institution led by eminent artists and architects. Its ...

, and Victoria published a book, ''Leaves from the Journal of Our Life in the Highlands'', which featured Brown prominently and in which the Queen praised him highly.

Palmerston died in 1865, and after a brief ministry led by Russell, Derby returned to power. In 1866, Victoria attended the State Opening of Parliament

The State Opening of Parliament is a ceremonial event which formally marks the beginning of each Legislative session, session of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. At its core is His or Her Majesty's "Speech from the throne, gracious speech ...

for the first time since Albert's death. The following year she supported the passing of the Reform Act 1867

The Representation of the People Act 1867 ( 30 & 31 Vict. c. 102), known as the Reform Act 1867 or the Second Reform Act, is an act of the British Parliament that enfranchised part of the urban male working class in England and Wales for the ...

which doubled the electorate by extending the franchise to many urban working men, though she was not in favour of votes for women. Derby resigned in 1868, to be replaced by Benjamin Disraeli

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield (21 December 1804 – 19 April 1881) was a British statesman, Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician and writer who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. He played a ...

, who charmed Victoria. "Everyone likes flattery," he said, "and when you come to royalty you should lay it on with a trowel." With the phrase "we authors, Ma'am", he complimented her. Disraeli's ministry only lasted a matter of months, and at the end of the year his Liberal rival, William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British politican, starting as Conservative MP for Newark and later becoming the leader of the Liberal Party (UK), Liberal Party.

In a career lasting over 60 years, he ...

, was appointed prime minister. Victoria found Gladstone's demeanour far less appealing; he spoke to her, she is thought to have complained, as though she were "a public meeting rather than a woman".

In 1870 republican sentiment in Britain, fed by the Queen's seclusion, was boosted after the establishment of the Third French Republic

The French Third Republic (, sometimes written as ) was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940, after the Fall of France duri ...

. A republican rally in Trafalgar Square

Trafalgar Square ( ) is a public square in the City of Westminster in Central London. It was established in the early-19th century around the area formerly known as Charing Cross. Its name commemorates the Battle of Trafalgar, the Royal Navy, ...

demanded Victoria's removal, and Radical MPs spoke against her. In August and September 1871, she was seriously ill with an abscess

An abscess is a collection of pus that has built up within the tissue of the body, usually caused by bacterial infection. Signs and symptoms of abscesses include redness, pain, warmth, and swelling. The swelling may feel fluid-filled when pre ...

in her arm, which Joseph Lister

Joseph Lister, 1st Baron Lister, (5 April 1827 – 10 February 1912) was a British surgeon, medical scientist, experimental pathologist and pioneer of aseptic, antiseptic surgery and preventive healthcare. Joseph Lister revolutionised the Sur ...

successfully lanced and treated with his new antiseptic carbolic acid

Phenol (also known as carbolic acid, phenolic acid, or benzenol) is an aromatic organic compound with the molecular formula . It is a white crystalline solid that is volatile and can catch fire.

The molecule consists of a phenyl group () bon ...

spray. In late November 1871, at the height of the republican movement, the Prince of Wales contracted typhoid fever, the disease that was believed to have killed his father, and Victoria was fearful her son would die. As the tenth anniversary of her husband's death approached, her son's condition grew no better, and Victoria's distress continued. To general rejoicing, he recovered. Mother and son attended a public parade through London and a grand service of thanksgiving in St Paul's Cathedral

St Paul's Cathedral, formally the Cathedral Church of St Paul the Apostle, is an Anglican cathedral in London, England, the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London in the Church of Engl ...

on 27 February 1872, and republican feeling subsided.

On the last day of February 1872, two days after the thanksgiving service, 17-year-old Arthur O'Connor, a great-nephew of Irish MP Feargus O'Connor

Feargus Edward O'Connor (18 July 1796 – 30 August 1855) was an Irish Chartism, Chartist leader and advocate of the Land Plan, which sought to provide smallholdings for the labouring classes. A highly charismatic figure, O'Connor was admired ...

, waved an unloaded pistol at Victoria's open carriage just after she had arrived at Buckingham Palace. Brown, who was attending the Queen, grabbed him and O'Connor was later sentenced to 12 months' imprisonment, and a birching

Birching is a form of corporal punishment with a birch rod, typically used to strike the recipient's bare buttocks, although occasionally the back and/or shoulders.

Implement

A birch rod (often shortened to "birch") is a bundle of leafless t ...