Zulfikar Ali Bhutto (5 January 1928 – 4 April 1979) was a Pakistani barrister and politician who served as the fourth

president of Pakistan

The president of Pakistan () is the head of state of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. The president is the nominal head of the executive and the supreme commander of the Pakistan Armed Forces. from 1971 to 1973 and later as the ninth

prime minister of Pakistan

The prime minister of Pakistan (, Roman Urdu, romanized: Wazīr ē Aʿẓam , ) is the head of government of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. Executive authority is vested in the prime minister and his chosen Cabinet of Pakistan, cabinet, desp ...

from 1973 until his

overthrow in 1977. He was also the founder and first chairman of the

Pakistan People's Party

The Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) is a political party in Pakistan and one of the three major Pakistani political parties alongside the Pakistan Muslim League (N) and Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf. With a centre-left political position, it is cu ...

(PPP) from 1967 until his execution in 1979.

Born in

Sindh

Sindh ( ; ; , ; abbr. SD, historically romanized as Sind (caliphal province), Sind or Scinde) is a Administrative units of Pakistan, province of Pakistan. Located in the Geography of Pakistan, southeastern region of the country, Sindh is t ...

and educated at the

University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California), is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Berkeley, California, United States. Founded in 1868 and named after t ...

and the

University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a collegiate university, collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the List of oldest un ...

, Bhutto trained as a barrister at

Lincoln's Inn

The Honourable Society of Lincoln's Inn, commonly known as Lincoln's Inn, is one of the four Inns of Court (professional associations for Barrister, barristers and judges) in London. To be called to the bar in order to practise as a barrister ...

before entering

politics

Politics () is the set of activities that are associated with decision-making, making decisions in social group, groups, or other forms of power (social and political), power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of Social sta ...

. He was a cabinet member during President

Iskandar Ali Mirza

Iskander Ali Mirza (13 November 189913 November 1969) was a Bengali politician, statesman and military general who served as the Dominion of Pakistan's fourth and last Governor-General of Pakistan, governor-general of Pakistan from 1955 to 1956, ...

's tenure, holding various ministries during president

Ayub Khan

Mohammad Ayub Khan (14 May 1907 – 19 April 1974) was a Pakistani military dictator who served as the second president of Pakistan from 1958 until his resignation on 1969. He was the first native commander-in-chief of the Pakistan Army, se ...

's military rule from 1958. Bhutto became the

Foreign Minister

In many countries, the ministry of foreign affairs (abbreviated as MFA or MOFA) is the highest government department exclusively or primarily responsible for the state's foreign policy and relations, diplomacy, bilateral, and multilateral r ...

in 1963, advocating for

Operation Gibraltar

Operation Gibraltar was the codename of a military operation planned and executed by the Pakistan Army in the territory of Jammu and Kashmir, India in August 1965. The operation's strategy was to covertly cross the Line of Control (LoC) an ...

in

Kashmir

Kashmir ( or ) is the Northwestern Indian subcontinent, northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term ''Kashmir'' denoted only the Kashmir Valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir P ...

, leading to the

1965 war with India. Following the

Tashkent Declaration

The Tashkent Declaration was signed between India and Pakistan on 10 January 1966 to resolve the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965. Peace was achieved on 23 September through interventions by the Soviet Union and the United States, both of which pus ...

, he was dismissed from the government. Bhutto established the PPP in 1967, focusing on an

Islamic socialist agenda, and contested the

1970 general election. The Awami League and PPP were unable to agree on power transfer, leading to civil unrest and the creation of Bangladesh. After Pakistan's loss in the

1971 war against Bangladesh, Bhutto assumed the presidency in December 1971, imposing

emergency rule

An emergency is an urgent, unexpected, and usually dangerous situation that poses an immediate risk to health, life, property, or environment and requires immediate action. Most emergencies require urgent intervention to prevent a worsening ...

.

Bhutto secured the release of 93,000

prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of war for a ...

through the Delhi Agreement, a trilateral accord signed between India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh on 28 August 1973, and ratified only by India and Pakistan. He also reclaimed of Indian-held territory through the

Simla Agreement

The Simla Agreement, also spelled Shimla Agreement, was a peace treaty signed between India and Pakistan on 2 July 1972 in Shimla, the capital of Himachal Pradesh. It followed the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971, which began after India interv ...

, signed between India and Pakistan in the Indian town of Simla in July 1972. He strengthened diplomatic ties with

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

and

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in West Asia. Located in the centre of the Middle East, it covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula and has a land area of about , making it the List of Asian countries ...

, recognized Bangladesh, and hosted the second

Organisation of the Islamic Conference

The Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC; ; ), formerly the Organisation of the Islamic Conference, is an intergovernmental organisation founded in 1969. It consists of 57 member states, 48 of which are Muslim-majority. The Pew Forum on ...

in

Lahore

Lahore ( ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the Administrative units of Pakistan, Pakistani province of Punjab, Pakistan, Punjab. It is the List of cities in Pakistan by population, second-largest city in Pakistan, after Karachi, and ...

in 1974. Bhutto's government drafted the current

constitution of Pakistan

The Constitution of Pakistan ( ; ISO 15919, ISO: '' Āīn-ē-Pākistān''), also known as the 1973 Constitution, is the supreme law of Pakistan. The document guides Pakistan's law, political culture, and system. It sets out the state's outlin ...

in 1973, after which he transitioned to the prime minister's office. He played a crucial role in initiating the

country's nuclear program. However, his policies, including extensive

nationalisation

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English)

is the process of transforming privately owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization contrasts with priv ...

which has remained controversial throughout.

Despite winning the

1977 parliamentary elections, Bhutto faced allegations of widespread

vote rigging

Electoral fraud, sometimes referred to as election manipulation, voter fraud, or vote rigging, involves illegal interference with the process of an election, either by increasing the vote share of a favored candidate, depressing the vote share o ...

, sparking violence across the country. On 5 July 1977, Bhutto was deposed in a

military coup

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. Militaries are typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with their members identifiable by a d ...

by army chief

Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq

Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq (12 August 192417 August 1988) was a Pakistani military officer and statesman who served as the sixth president of Pakistan from 1978 until Death of Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, his death in an airplane crash in 1988. He also se ...

. Controversially tried and executed in 1979, Bhutto's legacy remains contentious, praised for nationalism and a secular internationalist agenda, yet criticized for political repression, economic challenges, and human rights abuses. He is often considered one of

Pakistan's greatest leaders. His party, the PPP, continues to be a significant political force in Pakistan, with his daughter

Benazir Bhutto

Benazir Bhutto (21 June 1953 – 27 December 2007) was a Pakistani politician who served as the 11th prime minister of Pakistan from 1988 to 1990, and again from 1993 to 1996. She was also the first woman elected to head a democratic governmen ...

serving twice as Prime Minister, and his son-in-law,

Asif Ali Zardari

Asif Ali Zardari (born 26 July 1955) is a Pakistani politician serving as the 14th president of Pakistan since 2024, having held the same office from 2008 to 2013. He is the president of Pakistan People's Party Parliamentarians and was the ...

, becoming president.

Early life and education

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto belonged to a

Sindhi Rajput

Rājpūt (, from Sanskrit ''rājaputra'' meaning "son of a king"), also called Thākur (), is a large multi-component cluster of castes, kin bodies, and local groups, sharing social status and ideology of genealogical descent originating fro ...

family;

Owen Bennett-Jones

Owen Bennett-Jones is a freelance British journalist and a relief presenter of '' Newshour'' on the BBC World Service. As a former BBC correspondent having been based in several countries, he also regularly reports from around the world. He h ...

writes that the family traces its ancestry back to a 9th-century Rajput prince of the

Bhati

Bhati (also romanised as Bhattī) is a Rajput clan. The Bhati clan historically ruled over several cities in present-day India and Pakistan with their final capital and kingdom being Jaisalmer, India.

History

The Bhatis of Jaisalmer bel ...

clan who ruled the town of Tanot (in current-day

Rajasthan, India

Rajasthan (; lit. 'Land of Kings') is a state in northwestern India. It covers or 10.4 per cent of India's total geographical area. It is the largest Indian state by area and the seventh largest by population. It is on India's northweste ...

), Bhutto's ancestors later appearing in different Rajasthani chronicles in prominent roles, the family converting to Islam mostly around the 17th century before moving to Sindh.

He was born to

Shah Nawaz Bhutto

Shah Nawaz Bhutto (, , ), 8 March 1888 – 19 November 1957, was a politician and a member of the Bhutto family hailing from Larkana in the Sind region of the Bombay Presidency of British India, which is now Sindh, Pakistan.

Early life and ...

and Khursheed Begum near

Larkana

Larkana (; ) is a city located in the Sindh province of Pakistan. It is the 15th largest city of Pakistan by population. It is home to the Indus Valley civilization site Mohenjo-daro. The historic Indus River flows in east and south of the ci ...

. His father was the ''

dewan

''Dewan'' (also known as ''diwan'', sometimes spelled ''devan'' or ''divan'') designated a powerful government official, minister, or ruler. A ''dewan'' was the head of a state institution of the same name (see Divan). Diwans belonged to the el ...

'' of the

princely state of

Junagadh

Junagadh () is the city and headquarters of Junagadh district in the Indian state of Gujarat. Located at the foot of the Girnar hills, southwest of Ahmedabad and Gandhinagar (the state capital), it is the seventh largest city in the state. It i ...

and enjoyed an influential relationship with the officials of the

British Raj

The British Raj ( ; from Hindustani language, Hindustani , 'reign', 'rule' or 'government') was the colonial rule of the British The Crown, Crown on the Indian subcontinent,

*

* lasting from 1858 to 1947.

*

* It is also called Crown rule ...

. His mother, Khursheed Begum, was born Lakhi Bai, and had been a professional dance girl from a

Hindu

Hindus (; ; also known as Sanātanīs) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism, also known by its endonym Sanātana Dharma. Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pp. 35–37 Historically, the term has also be ...

family but

converted to Islam

Reversion to Islam, also known within Islam as reversion, is adopting Islam as a religion or faith. Conversion requires a formal statement of the '' shahādah'', the credo of Islam, whereby the prospective convert must state that "there is none w ...

when she married Shah Nawaz. Reportedly, Shah Nawaz Bhutto had seen her dancing and had proposed, eventually marrying her. Zulfikar was their third child — the first, Sikandar Ali, had died from pneumonia at age seven in 1914, and the second, Imdad Ali, died of

cirrhosis

Cirrhosis, also known as liver cirrhosis or hepatic cirrhosis, chronic liver failure or chronic hepatic failure and end-stage liver disease, is a chronic condition of the liver in which the normal functioning tissue, or parenchyma, is replaced ...

at age 39 in 1953.

As a young boy, Bhutto moved to

Worli Seaface in

Bombay

Mumbai ( ; ), also known as Bombay ( ; its official name until 1995), is the capital city of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of Maharashtra. Mumbai is the financial centre, financial capital and the list of cities i ...

to study at the

Cathedral and John Connon School

The Cathedral and John Connon School is a co-educational private school founded in 1860 and located in Fort, Mumbai, Maharashtra.[St. Xavier's College, Mumbai

St. Xavier's College is a private, Catholic Church, Catholic, institution of higher education run by the

Bombay Province of the Society of Jesus in Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. It was founded by the Jesuits on 2 January 1869. The college is ...](_blank)

. He then also became an activist in the

Pakistan Movement

The Pakistan Movement was a religiopolitical and social movement that emerged in the early 20th century as part of a campaign that advocated the creation of an Islamic state in parts of what was then British Raj. It was rooted in the two-nation the ...

. In 1943, his marriage was arranged with Shireen Amir Begum.

In 1947, Bhutto was admitted to the

University of Southern California

The University of Southern California (USC, SC, or Southern Cal) is a Private university, private research university in Los Angeles, California, United States. Founded in 1880 by Robert M. Widney, it is the oldest private research university in ...

to study political science.

In 1949, as a sophomore, Bhutto transferred to the

University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California), is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Berkeley, California, United States. Founded in 1868 and named after t ...

, where he earned a B.A. (honours) degree in political science in 1950.

A year later on 8 September 1951, he married a woman of Iranian Kurdish origin—Nusrat Ispahani, popularly known as

Begum Nusrat Bhutto. During his studies at the

University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California), is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Berkeley, California, United States. Founded in 1868 and named after t ...

, Bhutto became interested in the theories of socialism, delivering a series of lectures on their feasibility in Islamic countries. During this time, Bhutto's father played a controversial role in the affairs of Junagadh. Coming to power in a palace coup, he secured the accession of his state to Pakistan, which was ultimately negated by Indian intervention in December 1947.

In June 1950, Bhutto travelled to the United Kingdom to study law at

Christ Church, Oxford

Christ Church (, the temple or house, ''wikt:aedes, ædes'', of Christ, and thus sometimes known as "The House") is a Colleges of the University of Oxford, constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. Founded in 1546 by Henry V ...

and received a

BA in

jurisprudence

Jurisprudence, also known as theory of law or philosophy of law, is the examination in a general perspective of what law is and what it ought to be. It investigates issues such as the definition of law; legal validity; legal norms and values ...

, followed by an LLM degree in law and an M.Sc. (honours) degree in political science.

Upon finishing his studies, he served as a lecturer in international law at the

University of Southampton

The University of Southampton (abbreviated as ''Soton'' in post-nominal letters) is a public university, public research university in Southampton, England. Southampton is a founding member of the Russell Group of research-intensive universit ...

in 1952, and he was called to the bar at

Lincoln's Inn

The Honourable Society of Lincoln's Inn, commonly known as Lincoln's Inn, is one of the four Inns of Court (professional associations for Barrister, barristers and judges) in London. To be called to the bar in order to practise as a barrister ...

in 1953.

Political career

In 1957, Bhutto became the youngest member of Pakistan's delegation to the United Nations. He addressed the

UN Sixth Committee on Aggression that October and led Pakistan's delegation to the first

UN Conference on the Law of the Sea

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), also called the Law of the Sea Convention or the Law of the Sea Treaty, is an Treaty, international treaty that establishes a legal framework for all marine and maritime activities. , ...

in 1958. That year, Bhutto became Pakistan's youngest cabinet minister, taking up the reins of the

Ministry of Commerce A ministry of trade and industry, ministry of commerce, ministry of commerce and industry or variations is a ministry that is concerned with a nation's trade, industry and commerce.

Notable examples are:

List

*Algeria: Ministry of Industry and ...

by President

Iskander Mirza

Iskander Ali Mirza (13 November 189913 November 1969) was a Bengali politician, statesman and military general who served as the Dominion of Pakistan's fourth and last governor-general of Pakistan from 1955 to 1956, and then as the Islamic Repub ...

, pre-''

coup d'état

A coup d'état (; ; ), or simply a coup

, is typically an illegal and overt attempt by a military organization or other government elites to unseat an incumbent leadership. A self-coup is said to take place when a leader, having come to powe ...

'' government.

Bhutto became a trusted ally and advisor of Ayub Khan, rising in influence and power despite his youth and relative inexperience. Bhutto was a junior minister in Ayub Khan administration at the time of signing the

Indus Waters Treaty

The Indus Water Treaty (IWT) is a water-distribution treaty between India and Pakistan, arranged and negotiated by the World Bank, to use the water available in the Indus River and its tributaries. It was signed in Karachi on 19 September 196 ...

with India in 1960 and was not part of the negotiating team. Bhutto was against this treaty due to yielding too much of water resources to India. Later he vehemently talked publicly against the IWT during his campaign against Ayub Khan regime. Bhutto negotiated an

oil-exploration agreement with the Soviet Union in 1961, which agreed to provide economic and technical aid to Pakistan.

Foreign minister

Bhutto, a

Pakistani nationalist

Pakistani nationalism refers to the political, cultural, linguistic, historical, religious and geographical expression of patriotism by the people of Pakistan, of pride in the history, heritage and identity of Pakistan, and visions for its fu ...

and

socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

,

held distinctive views on the democracy required in Pakistan. Upon becoming foreign minister in 1963, his socialist stance led to a

close relationship

An intimate relationship is an interpersonal relationship that involves emotional or physical closeness between people and may include sexual intimacy and feelings of Romance (love), romance or love. Intimate relationships are Interdependence ...

with neighboring China, challenging the prevailing acceptance of

Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The main geography of Taiwan, island of Taiwan, also known as ''Formosa'', lies between the East China Sea, East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocea ...

as the legitimate government of China when

two governments each claimed to be "China".

In 1964, the Soviet Union and its

satellite states

A satellite state or dependent state is a country that is formally independent but under heavy political, economic, and military influence or control from another country. The term was coined by analogy to planetary objects orbiting a larger ob ...

broke off relations with Beijing over ideological differences, with only

Albania

Albania ( ; or ), officially the Republic of Albania (), is a country in Southeast Europe. It is located in the Balkans, on the Adriatic Sea, Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea, and shares land borders with Montenegro to ...

and Pakistan supporting the People's Republic of China. Bhutto staunchly supported Beijing in the UN and the

UNSC

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, an ...

, while also maintaining connections with the United States.

Bhutto's strong advocacy for closer ties with China drew criticism from the United States, with President

Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), also known as LBJ, was the 36th president of the United States, serving from 1963 to 1969. He became president after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, under whom he had served a ...

cautioning him about potential repercussions on congressional support for aid to Pakistan. Bhutto, known for his demagogic speeches, led the

foreign ministry

In many countries, the ministry of foreign affairs (abbreviated as MFA or MOFA) is the highest government department exclusively or primarily responsible for the state's foreign policy and relations, diplomacy, bilateral, and multilateral re ...

assertively, rapidly gaining national prominence. During a visit to

Beijing

Beijing, Chinese postal romanization, previously romanized as Peking, is the capital city of China. With more than 22 million residents, it is the world's List of national capitals by population, most populous national capital city as well as ...

, Bhutto and his staff received a warm welcome from the Chinese leadership, including

Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; traditionally Romanization of Chinese, romanised as Mao Tse-tung. (26December 18939September 1976) was a Chinese politician, revolutionary, and political theorist who founded the People's Republic of China (PRC) in ...

.

Bhutto contributed to negotiating trade and military agreements between Pakistan and China, fostering collaboration on various military and industrial projects.

Bhutto signed the

Sino-Pakistan Boundary Agreement on 2 March 1963, transferring 750 square kilometers of territory from

Gilgit Baltistan

Gilgit (; Shina: ; ) is a city in Pakistani-administered Gilgit–Baltistan in the disputed Kashmir region.The application of the term "administered" to the various regions of Kashmir and a mention of the Kashmir dispute is supported by the ...

to Chinese control. Bhutto embraced

non-alignment, making Pakistan an influential member in non-aligned organizations. Advocating

pan-Islamic unity, Bhutto developed closer relations with Indonesia and Saudi Arabia. Bhutto significantly transformed Pakistan's pro-West foreign policy. While maintaining a role in the

Southeast Asia Treaty Organization

The Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) was an international organization for collective defense in Southeast Asia created by the Southeast Asia Collective Defense Treaty signed in September 1954 in Manila, Philippines. The formal insti ...

and the

Central Treaty Organization

The Central Treaty Organization (CENTO), formerly known as the Middle East Treaty Organization (METO) and also known as the Baghdad Pact, was a military alliance of the Cold War. It was formed on 24 February 1955 by Iran, Iraq, Pakistan, Turkey, ...

, Bhutto asserted an independent foreign policy for Pakistan, free from

U.S. influence. Bhutto also visited

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

in 1962, establishing diplomatic relations and fostering mutual cooperation, reaching out to the

Polish community in Pakistan. Using

Pakistan Air Force

The Pakistan Air Force (PAF) (; ) is the aerial warfare branch of the Pakistan Armed Forces, tasked primarily with the aerial defence of Pakistan, with a secondary role of providing air support to the Pakistan Army and Pakistan Navy when re ...

's Brigadier-General

Władysław Turowicz

Władysław Józef Marian Turowicz (; 23 April 1908 – 8 January 1980), usually referred to as W. J. M. Turowicz, was a Polish-Pakistani aviator, military scientist and aeronautical engineer.

He was one of forty five Polish officers and airm ...

, Bhutto initiated military and economic links between Pakistan and Poland.

In 1962, as territorial differences escalated between India and China, Beijing considered staging

an invasion in northern Indian territories. Premier

Zhou Enlai

Zhou Enlai ( zh, s=周恩来, p=Zhōu Ēnlái, w=Chou1 Ên1-lai2; 5 March 1898 – 8 January 1976) was a Chinese statesman, diplomat, and revolutionary who served as the first Premier of the People's Republic of China from September 1954 unti ...

and Mao invited Pakistan to join the raid to reclaim the

State of Jammu and Kashmir

Jammu and Kashmir was a region formerly administered by India as a state from 1952 to 2019, constituting the southern and southeastern portion of the larger Kashmir region, which has been the subject of a dispute between India, Pakistan an ...

from India. Bhutto supported the plan, but Ayub opposed it due to fears of Indian retaliation.

Instead, Ayub proposed a "joint defense union" with India, shocking Bhutto, who felt Ayub Khan lacked understanding of international affairs. Bhutto, aware of China's restraint from criticizing Pakistan despite its membership in anti-communist western alliances, criticized the U.S. for providing military aid to India during and after the 1962 Sino-Indian War, seen as a breach of Pakistan's alliance with the United States.

On Bhutto's counsel, Ayub Khan launched

Operation Gibraltar

Operation Gibraltar was the codename of a military operation planned and executed by the Pakistan Army in the territory of Jammu and Kashmir, India in August 1965. The operation's strategy was to covertly cross the Line of Control (LoC) an ...

in an attempt to

"liberate" Kashmir. The operation failed, leading to the

Indo-Pakistani War of 1965.

This war followed brief skirmishes between March and August 1965 in the

Rann of Kutch

The Rann of Kutch is a large area of salt marshes that span the border between India and Pakistan. It is located mostly in the Kutch district of the Indian state of Gujarat, with a minor portion extending into the Sindh province of Pakistan. ...

, Jammu and Kashmir, and Punjab. Bhutto joined Ayub in Uzbekistan to negotiate a

peace treaty

A peace treaty is an treaty, agreement between two or more hostile parties, usually country, countries or governments, which formally ends a declaration of war, state of war between the parties. It is different from an armistice, which is an ag ...

with Indian Prime Minister

Lal Bahadur Shastri

Lal Bahadur Shastri (; born Lal Bahadur Srivastava; 2 October 190411 January 1966) was an Indian politician and statesman who served as the Prime Minister of India, prime minister of India from 1964 to 1966. He previously served as Minister ...

. Ayub and Shastri agreed to exchange prisoners of war and withdraw respective forces to pre-war boundaries. The agreement, deeply unpopular in Pakistan, caused significant political unrest against Ayub's regime. Bhutto's criticism of the final agreement created a major rift with Ayub. Initially denying rumors, Bhutto resigned in June 1966, expressing strong opposition to Ayub's regime.

During his term, Bhutto formulated aggressive geostrategic and foreign policies against India.

In 1965, Bhutto received information from his friend

Munir Ahmad Khan

Munir Ahmad Khan (; 20 May 1926 – 22 April 1999), , was a Pakistani nuclear engineer who is credited, among others, with being the "father of the atomic bomb program" of Pakistan for their leading role in developing their nation's nuclear we ...

about the status of

India's nuclear program. Bhutto stated, "Pakistan will fight, fight for a thousand years. If India builds the (atom) bomb, Pakistan will eat grass or leaves, even go hungry, but we (Pakistan) will get one of our own (atom bomb).... We (Pakistan) have no other choice!" In his 1969 book ''The Myth of Independence,'' Bhutto argued for the necessity of Pakistan acquiring a fission weapon and starting a deterrence program to stand up to industrialized states and a nuclear-armed India. He developed a manifesto outlining the program's development and selected Munir Ahmad Khan to lead it.

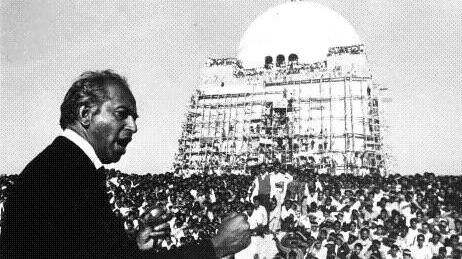

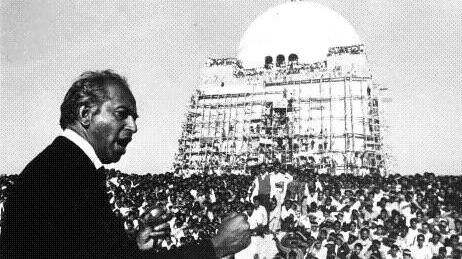

Pakistan People's Party

After resigning as foreign minister, large crowds gathered to hear Bhutto's speech upon his arrival in Lahore on 21 June 1967. Riding a wave of anger against Ayub, Bhutto traveled across Pakistan, delivering political speeches. In October 1966, Bhutto explicitly outlined the beliefs of his new party: "Islam is our faith, democracy is our policy, socialism is our economy. All power to the people."

On 30 November 1967, at the Lahore residence of

Mubashir Hassan

Mubashir Hassan (; 22 January 1922 – 14 March 2020) was a Pakistani politician, Humanism, humanist, political adviser, and an engineer who served in the capacity of Finance Minister of Pakistan, Finance Minister in Zulfikar Ali Bhutto#Prime M ...

, a gathering including Bhutto, political activist Sufi Nazar Muhammad Khan, Bengali communist

J. A. Rahim, and

Basit Jehangir Sheikh founded the

Pakistan Peoples Party

The Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) is a political party in Pakistan and one of the three major List of political parties in Pakistan, Pakistani political parties alongside the Pakistan Muslim League (N) and Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf. With a Cent ...

(PPP), establishing a strong base in Punjab, Sindh, and among the

Muhajirs.

[Hassan, Mubashir (2000). ''The Mirage of Power: An Inquiry into the Bhutto Years, 1971–1977''. ]Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the publishing house of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world. Its first book was printed in Oxford in 1478, with the Press officially granted the legal right to print books ...

. .

Mubashir Hassan, an engineering professor at

UET Lahore, played a pivotal role in the success and rise of Bhutto. Under Hassan's guidance and Bhutto's leadership, the PPP became part of the pro-democracy movement involving diverse political parties from all across Pakistan. PPP activists staged large protests and strikes in different parts of the country, increasing pressure on Ayub to resign.

Asghar Khan

Mohammad Asghar Khan (17 January 1921 – 5 January 2018) known as ''Night Flyer,'' held the distinction of being the first native and second C-in-C of the PAF, Commander-in-Chief of the Pakistan Air Force (PAF) from 1957 to 1965. He has been d ...

recalls Bhutto asking him to join his party, the

Pakistan Peoples Party

The Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) is a political party in Pakistan and one of the three major List of political parties in Pakistan, Pakistani political parties alongside the Pakistan Muslim League (N) and Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf. With a Cent ...

(PPP). Asghar Khan declined, stating he had no interest in politics. After Dr. Hassan and Bhutto's arrest on 12 November 1968, Asghar Khan held a press conference in Lahore on 17 November 1968. Asghar Khan led protests calling for Bhutto's release, which ultimately led to his freedom and grew so close to Bhutto that many saw him as a potential successor. After his release, Bhutto, joined by key leaders of PPP, attended the Round Table Conference called by Ayub Khan in

Rawalpindi

Rawalpindi is the List of cities in Punjab, Pakistan by population, third-largest city in the Administrative units of Pakistan, Pakistani province of Punjab, Pakistan, Punjab. It is a commercial and industrial hub, being the list of cities in P ...

but refused to accept Ayub's continuation in office and

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman (17 March 1920 – 15 August 1975), also known by the honorific Bangabandhu, was a Bangladeshi politician, revolutionary, statesman and activist who was the founding president of Bangladesh. As the leader of Bangl ...

's

Six point movement for regional autonomy.

1970 elections

Following Ayub's resignation, his successor, General

Yahya Khan

Agha Muhammad Yahya Khan (4 February 191710 August 1980) was a Pakistani army officer who served as the third president of Pakistan from 1969 to 1971. He also served as the fifth Commander-in-Chief, Pakistan, commander-in-chief of the Pakistan ...

promised to hold

parliamentary elections

A general election is an electoral process to choose most or all members of a governing body at the same time. They are distinct from by-elections, which fill individual seats that have become vacant between general elections. General elections ...

on 7 December 1970. Under Bhutto's leadership, the democratic

socialists

Socialism is an economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes the economic, political, and socia ...

, leftists, and

Marxist

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflic ...

-

communists

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, d ...

gathered and united into one

party platform

A political party platform (American English), party program, or party manifesto (preferential term in British and often Commonwealth English) is a formal set of principal goals which are supported by a political party or individual candidate, t ...

for the first time in Pakistan's history. The Socialist-Communist bloc, under Bhutto's leadership, intensified its support in Muhajir and poor farming communities in West Pakistan, working through educating people to cast their vote for their better future.

Gathering and uniting the scattered socialist-communist groups in one single center was considered Bhutto's greatest political achievement and as a result, Bhutto's party and other leftists won a large number of seats from constituencies in West-Pakistan.

However, Sheikh Mujib's

Awami League

The Awami League, officially known as Bangladesh Awami League, is a major List of political parties in Bangladesh, political party in Bangladesh. The oldest existing political party in the country, the party played the leading role in achievin ...

won an absolute majority in the legislature, receiving more than twice as many votes as Bhutto's PPP. Bhutto strongly refused to accept an Awami League government and infamously threatened to "''break the legs''" of any elected PPP member who dared to attend the inaugural session of the

National Assembly

In politics, a national assembly is either a unicameral legislature, the lower house of a bicameral legislature, or both houses of a bicameral legislature together. In the English language it generally means "an assembly composed of the repr ...

. On 17 January 1971, President Yahya visited Bhutto at his baronial family estate, Al-Murtaza, in Larkana, Sindh, accompanied by Lt. General S. G. M. Pirzada, Principal Staff Officer to President Yahya, and General Abdul Hamid Khan, Commander-in-Chief of the Pakistan Army and Deputy Chief

Martial Law

Martial law is the replacement of civilian government by military rule and the suspension of civilian legal processes for military powers. Martial law can continue for a specified amount of time, or indefinitely, and standard civil liberties ...

Administrator.

On 22 February 1971, the generals in West Pakistan took a decision allegedly to crush the Awami League and its supporters. Capitalizing on West Pakistani fears of

East Pakistan

East Pakistan was the eastern province of Pakistan between 1955 and 1971, restructured and renamed from the province of East Bengal and covering the territory of the modern country of Bangladesh. Its land borders were with India and Burma, wit ...

i separatism, Bhutto demanded that Sheikh Mujibur Rahman form a coalition with the PPP. And at some stage proposed "''idhar hum, udhar tum''", meaning he should govern the West and Mujib should Govern the East. President Yahya postponed the meeting of the national assembly which fueled a popular movement in East Pakistan. Amidst popular outrage in East Pakistan, on 7 March 1971, Sheikh Mujib called the Bengalis to join the struggle for "

Bangladesh

Bangladesh, officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by population, eighth-most populous country in the world and among the List of countries and dependencies by ...

". According to historical references and a report published by the leading Pakistani newspaper

''The Nation'', "Mujib no longer believed in Pakistan and is determined to make Bangladesh". Many also believed that Bhutto wanted power in the West even at the expense of the separation of the East.

However, Mujib still kept doors open for some sort of settlement in his speech of 7 March.

Fall of East Pakistan

Yahya started a negotiating conference in Dhaka, presumably to reach a settlement between Bhutto and Mujib. The discussion was expected to be "fruitful" until the president left for

West Pakistan

West Pakistan was the western province of Pakistan between One Unit, 1955 and Legal Framework Order, 1970, 1970, covering the territory of present-day Pakistan. Its land borders were with Afghanistan, India and Iran, with a maritime border wit ...

on the evening of 25 March. On that night of 25 March 1971, the army initiated

Operation Searchlight

Operation Searchlight was a military operation carried out by the Pakistan Army in an effort to curb the Bengali nationalist movement in former East Pakistan in March 1971. Pakistan retrospectively justified the operation on the basis of ant ...

, which had been planned by the military junta of Yahya Khan, presumably to suppress political activities and movements by the Bengalis. Mujib was arrested and imprisoned in West Pakistan. Genocide and atrocities by the military against the Bengali population were alleged during the operation.

[Blood, Archer]

Transcript of Selective Genocide Telex

Department of State, United States

Bhutto stayed in

Dhaka

Dhaka ( or ; , ), List of renamed places in Bangladesh, formerly known as Dacca, is the capital city, capital and list of cities and towns in Bangladesh, largest city of Bangladesh. It is one of the list of largest cities, largest and list o ...

on the night of 25 March and commented that Pakistan had been saved by the army before leaving on the 26th. While supportive of the army's actions and working to rally international support, Bhutto distanced himself from the Yahya Khan regime and began to criticize Yahya Khan for mishandling the situation.

He refused to accept Yahya Khan's scheme to appoint Bengali politician

Nurul Amin

Nurul Amin (15 July 1893 – 2 October 1974) was a Pakistani politician and jurist who served as the eighth prime minister of Pakistan from 7 December to 20 December 1971. His premiership term of only 13 days was the shortest served in Pakista ...

as Prime Minister, with Bhutto as deputy prime minister.

Soon after Bhutto's refusal and continuous resentment toward General Yahya Khan's mishandling of the situation, Khan ordered Military Police to arrest Bhutto on charges of

treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state (polity), state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to Coup d'état, overthrow its government, spy ...

, quite similar to Mujib.

Bhutto was imprisoned in the

Adiala Jail

Central Jail Rawalpindi (also known as Adiala Jail) is a prison located in Rawalpindi, Pakistan.

History

The Central Jail Rawalpindi was built from the late 1970s and early 1980s during the military regime of General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, after ...

along with Mujib, where he was set to face the charges.

The army crackdown on the

Bengalis

Bengalis ( ), also rendered as endonym and exonym, endonym Bangalee, are an Indo-Aryan peoples, Indo-Aryan ethnolinguistic group originating from and culturally affiliated with the Bengal region of South Asia. The current population is divi ...

of East Pakistan fueled an armed resistance by the

Mukti-Bahini (a guerrilla force formed for the campaign of an independent Bangladesh and trained by the Indian army). Pakistan launched an air attack on India in the western border that resulted in the Indian intervention in East Pakistan, which led to the very bitter defeat of Pakistani forces, who surrendered on 16 December 1971. Consequently,

the state of People's Republic of Bangladesh was born, and Bhutto and others condemned Yahya Khan for failing to protect Pakistan's unity.

Isolated, Yahya Khan resigned on 20 December and transferred power to Bhutto, who became president, commander-in-chief, and the first civilian chief martial law administrator.

Bhutto was the country's first civilian chief martial law administrator since 1958, as well as the country's first civilian president.

With Bhutto assuming control, the leftists and democratic socialists entered the country's politics and later emerged as power players in the country's politics. And, for the first time in the country's history, the leftists and democratic socialists had a chance to administer the country with the popular vote and widely approved exclusive mandate, given to them by the West's population in the 1970s elections.

In a reference written by

Kuldip Nayar

Kuldip Nayar (14 August 1923 – 23 August 2018) was an Indian journalist, syndicated columnist, human rights activist, author and former High Commissioner of India to the United Kingdom noted for his long career as a left-wing political com ...

in his book "''Scoop! Inside Stories from the Partition to the Present''", Nayar noted that "Bhutto's releasing of Mujib did not mean anything to Pakistan's policy as in

icif there was

icno liberation war.

Bhutto's policy, and even as of today, the policy of Pakistan continues to state that "she will continue to fight for the honor and integrity of Pakistan. East Pakistan is an inseparable and unseverable part of Pakistan".

Presidency (1971–1973)

A

Pakistan International Airlines

Pakistan International Airlines, commonly known as PIA, is the flag carrier of Pakistan. With its primary hub at Jinnah International Airport in Karachi, the airline also operates from its secondary hubs at Allama Iqbal International Airport ...

flight was sent to fetch Bhutto from New York City, where he was presenting Pakistan's case before the

United Nations Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, an ...

on the East Pakistan Crisis. Bhutto returned home on 18 December 1971. On 20 December, he was taken to the President House in Rawalpindi, where he took over two positions from Yahya Khan, one as president and the other as the first civilian Chief Martial Law Administrator. Thus, he was the first civilian Chief Martial Law Administrator of the dismembered Pakistan. By the time Bhutto had assumed control of what remained of Pakistan, the nation was completely isolated, angered, and demoralized. Bhutto addressing the nation through radio and television said:

My dear countrymen, my dear friends, my dear students, labourers, peasants... those who fought for Pakistan... We are facing the worst crisis in our country's life, a deadly crisis. We have to pick up the pieces, very small pieces, but we will make a new Pakistan, a prosperous and progressive Pakistan, a Pakistan free of exploitation, a Pakistan envisaged by the Quaid-e-Azam

Muhammad Ali Jinnah (born Mahomedali Jinnahbhai; 25 December 187611 September 1948) was a barrister, politician, and the founder of Pakistan. Jinnah served as the leader of the All-India Muslim League from 1913 until the inception of Pa ...

.

As president, Bhutto faced mounting challenges on both internal and foreign fronts. The trauma was severe in Pakistan, a psychological setback and emotional breakdown for Pakistan. The

two-nation theory—the theoretical basis for the creation of Pakistan—lay discredited, and Pakistan's foreign policy collapsed when no moral support was found anywhere, including long-standing allies such as the U.S. and China. However, this is disputed even by Bangladeshi academics who insist that the two-nation theory was not discredited. Since her creation, the physical and moral existence of Pakistan was in great danger. On the internal front,

Baloch,

Sindhi,

Punjabi

Punjabi, or Panjabi, most often refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to Punjab, a region in India and Pakistan

* Punjabi language

* Punjabis, Punjabi people

* Punjabi dialects and languages

Punjabi may also refer to:

* Punjabi (horse), a ...

, and

Pashtun nationalism

Pashtun nationalism () is an ideology that claims that the Pashtuns form a distinct nation and that they should always be united to preserve their culture and homeland. In Afghanistan, those who advocate Pashtun nationalism favour the idea of a " G ...

s were at their peak, calling for their independence from Pakistan. Finding it difficult to keep Pakistan united, Bhutto launched full-fledged intelligence and military operations to stamp out any separatist movements. By the end of 1978, these nationalist organizations were brutally quelled by Pakistan Armed Forces.

Bhutto immediately placed Yahya Khan under house arrest, brokered a ceasefire, and ordered the release of Mujib, who was being held prisoner by the Pakistan Army. To implement this, Bhutto overturned the verdict of Mujib's earlier court-martial trial, in which Brigadier

Rahimuddin Khan

Rahimuddin Khan (21 July 1926 – 22 August 2022) was a four-star rank Pakistani general who briefly served as the 16th Governor of Sindh in 1988. Previously, he had served as the fourth Chairman Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee from 1984 to 19 ...

had sentenced him to death. Bhutto aimed to prevent East Pakistan's secession through dialogue and sought to create a loose confederation within the framework of one Pakistan.

Stanley Wolpert

Stanley Albert Wolpert (December 23, 1927 – February 19, 2019) was an American historian, Indologist, and author on the political and intellectual history of modern India and PakistanDr. Stanley Wolpert's UCLA Faculty homepage and wrote fict ...

writes that he sent Mujib to a bungalow in

Rawalpindi

Rawalpindi is the List of cities in Punjab, Pakistan by population, third-largest city in the Administrative units of Pakistan, Pakistani province of Punjab, Pakistan, Punjab. It is a commercial and industrial hub, being the list of cities in P ...

, where Mujib swore upon the

Quran

The Quran, also Romanization, romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a Waḥy, revelation directly from God in Islam, God (''Allah, Allāh''). It is organized in 114 chapters (, ) which ...

to retire and hand over the nation to him. Bhutto also offered him 50,000, which Mujib declined. Mujib informed Bhutto that he would make this decision once he arrived in Bangladesh. On 8th January, he was flown to London, from where he was taken to

Delhi

Delhi, officially the National Capital Territory (NCT) of Delhi, is a city and a union territory of India containing New Delhi, the capital of India. Straddling the Yamuna river, but spread chiefly to the west, or beyond its Bank (geography ...

, where

Indira Gandhi

Indira Priyadarshini Gandhi (Given name, ''née'' Nehru; 19 November 1917 – 31 October 1984) was an Indian politician and stateswoman who served as the Prime Minister of India, prime minister of India from 1966 to 1977 and again from 1980 un ...

and her cabinet greeted him. From there, he was taken to

Dhaka

Dhaka ( or ; , ), List of renamed places in Bangladesh, formerly known as Dacca, is the capital city, capital and list of cities and towns in Bangladesh, largest city of Bangladesh. It is one of the list of largest cities, largest and list o ...

, as a direct flight to Bangladesh was not possible. There, he delivered a speech at the

Ramna Racecourse, completely rejecting Bhutto's offer and severing ties with West Pakistan, saying, "You live in peace and let us live in peace."

Appointing a new cabinet, Bhutto appointed Lieutenant-General

Gul Hasan

Gul Hassan Khan (9 June 1921 – 10 October 1999) known secretly as ''George'', was a Pakistani former three-star rank general and diplomat who served as the sixth and last Commander in Chief (Pakistan), Commander-in-Chief of the Pakistan Army ...

as

Commander-in-Chief of the Pakistan Army

The Commander-in-Chief of the Pakistan Army (abbreviation: C-in-C of the Pakistan Army) was the professional head of the Pakistan Army from 1947 to 1972. As an administrative position, the appointment holder had main operational command autho ...

in 20 December 1971. On 2 January 1972 Bhutto announced the nationalization of all major industries, including iron and steel, automobiles, heavy engineering, heavy electricals, petrochemicals, cement, and public utilities.

Bhutto had named his economic policies

Islamic Socialism

Islamic socialism is a political philosophy that incorporates elements of Islam into a system of socialism. As a term, it was coined by various left-wing Muslim leaders to describe a more spiritual form of socialism. Islamic socialists believe ...

or as he called "Mussawat-e Muhammadi". 31 industries across 10 sectors were nationalized including 13 banks, 10 shipping companies, 26 Vegetable Oil Companies, Two petroleum companies and 43 insurance companies which were tied together into

State Life Insurance Corporation of Pakistan. Ayub Khan's

Ghandhara Industries

Ghandhara Industries Limited (GIL) (), formerly known as National Motors Limited, doing business as Isuzu Pakistan, is a Pakistani truck and buses assembler based in Karachi. It is the authorized assembler of Isuzu vehicles in Pakistan. , Sharif owned

Ittefaq Foundry, National Bank of Pakistan and

Habib Bank Limited

Habib Bank Limited (often abbreviated as HBL) is a Pakistani bank headquartered at Habib Bank Plaza, Karachi with regional offices in Lahore and Islamabad. It is a subsidiary of Swiss-based organisation Aga Khan Fund for Economic Development ( ...

were also nationalized. This wave of nationalization didn't effect textile production light and food industries. In addition to foreign owned companies, Such as the British Attock Petroleum Company and American owned Esso Fertilizers.

In June 1972, Bhutto visited India to meet Prime Minister

Indira Gandhi

Indira Priyadarshini Gandhi (Given name, ''née'' Nehru; 19 November 1917 – 31 October 1984) was an Indian politician and stateswoman who served as the Prime Minister of India, prime minister of India from 1966 to 1977 and again from 1980 un ...

and negotiated a formal peace agreement and the release of 93,000 Pakistani

prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of war for a ...

. The two leaders signed the

Simla Agreement

The Simla Agreement, also spelled Shimla Agreement, was a peace treaty signed between India and Pakistan on 2 July 1972 in Shimla, the capital of Himachal Pradesh. It followed the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971, which began after India interv ...

, which committed both nations to establish a new-yet-temporary

Line of Control

The Line of Control (LoC) is a military control line between the Indian and Pakistanicontrolled parts of the former princely state of Jammu and Kashmir—a line which does not constitute a legally recognized international boundary, but ser ...

in Kashmir and obligated them to resolve disputes peacefully through bilateral talks.

Bhutto also promised to hold a future summit for the peaceful resolution of the Kashmir dispute and pledged to recognize Bangladesh. Although he secured the release of Pakistani soldiers held by India, Bhutto was criticized by many in Pakistan for allegedly making too many concessions to India. It is theorized that Bhutto feared his downfall if he could not secure the release of Pakistani soldiers and the return of territory occupied by Indian forces. Bhutto established an atomic power development program and inaugurated the first Pakistani

atomic reactor

A nuclear reactor is a device used to initiate and control a fission nuclear chain reaction. They are used for commercial electricity, marine propulsion, weapons production and research. Fissile nuclei (primarily uranium-235 or plutonium-239 ...

, built in collaboration with Canada in

Karachi

Karachi is the capital city of the Administrative units of Pakistan, province of Sindh, Pakistan. It is the List of cities in Pakistan by population, largest city in Pakistan and 12th List of largest cities, largest in the world, with a popul ...

on 28 November. On 30 March, 59 military officers were arrested by army troops for allegedly plotting a coup against Bhutto, who appointed then-Brigadier

Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq

Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq (12 August 192417 August 1988) was a Pakistani military officer and statesman who served as the sixth president of Pakistan from 1978 until Death of Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, his death in an airplane crash in 1988. He also se ...

to head a military tribunal to investigate and try the suspects. The National Assembly approved the

new 1973 Constitution, which Bhutto signed into effect on 12 April. The constitution proclaimed an "

Islamic Republic

The term Islamic republic has been used in different ways. Some Muslim religious leaders have used it as the name for a form of Islamic theocratic government enforcing sharia, or laws compatible with sharia. The term has also been used for a s ...

" in Pakistan with a parliamentary form of government. On 10 August, Bhutto turned over the post of president to

Fazal Ilahi Chaudhry

Fazal Elahi Chaudhry (; 1 January 19042 June 1982) was a Pakistani politician who served as the fifth president of Pakistan from 1973 to 1978 prior to the imposition of martial law led by Chief of Army Staff General Zia-ul-Haq. He also serve ...

, assuming the office of prime minister instead.

Nuclear weapons program

Bhutto, the founder of Pakistan's atomic bomb program, earned the title "Father of Nuclear Deterrence" due to his administration and aggressive leadership of this program.

Bhutto's interest in nuclear technology began during his college years in the United States, attending a political science course discussing the political impact of the U.S.'s first nuclear test,

''Trinity'', on global politics.

While at Berkeley, Bhutto witnessed the public panic when the Soviet Union first exploded their bomb, codenamed

''First Lightning'' in 1949, prompting the U.S. government to launch their research on

'hydrogen' bombs.

However, in 1958, as Minister for Fuel,

Power

Power may refer to:

Common meanings

* Power (physics), meaning "rate of doing work"

** Engine power, the power put out by an engine

** Electric power, a type of energy

* Power (social and political), the ability to influence people or events

Math ...

, and

National Resources, Bhutto played a key role in setting up the

Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission

Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission (PAEC) () is a federally funded independent governmental agency, concerned with research and development of nuclear power, promotion of nuclear science, energy conservation and the peaceful use of nuclear techn ...

(PAEC) administrative research bodies and institutes.

Soon, Bhutto offered a technical post to Munir Ahmad Khan in PAEC in 1958 and lobbied for Abdus Salam to be appointed as Science Adviser in 1960.

Before being elevated to

Foreign Minister

In many countries, the ministry of foreign affairs (abbreviated as MFA or MOFA) is the highest government department exclusively or primarily responsible for the state's foreign policy and relations, diplomacy, bilateral, and multilateral r ...

, Bhutto directed funds for key research in nuclear weapons and related science.

In October 1965, as the Foreign Minister, Bhutto visited Vienna, where nuclear engineer

Munir Ahmad Khan

Munir Ahmad Khan (; 20 May 1926 – 22 April 1999), , was a Pakistani nuclear engineer who is credited, among others, with being the "father of the atomic bomb program" of Pakistan for their leading role in developing their nation's nuclear we ...

held a senior technical post at the

IAEA

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) is an intergovernmental organization that seeks to promote the peaceful use of nuclear energy and to inhibit its use for any military purpose, including nuclear weapons. It was established in 1957 ...

. Munir Khan briefed him on the status of the

Indian nuclear programme

India possesses nuclear weapons and previously developed chemical weapons. Although India has not released any official statements about the size of its nuclear arsenal, recent estimates suggest that India has 180 nuclear weapons. India has co ...

and the options for Pakistan to develop its own nuclear capability. Both agreed on the necessity for Pakistan to establish a nuclear deterrent against India. Although Munir Khan had failed to convince Ayub Khan, Bhutto assured him, "''Don't worry, our turn will come''." Shortly after the 1965 war, Bhutto declared at a press conference, "''Even if we have to eat grass, we will make a nuclear bomb. We have no other choice''," observing India's progress toward developing the bomb.

In 1965, Bhutto advocated for Salam, successfully appointing him as the head of Pakistan's delegation at the IAEA, and assisted Salam in lobbying for nuclear power plants.

In November 1972, Bhutto advised Salam to travel to the United States to avoid the war and encouraged him to return with key literature on

nuclear weapons history. By the end of December 1972, Salam returned to Pakistan with suitcases loaded with literature on the ''

Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program undertaken during World War II to produce the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada.

From 1942 to 1946, the ...

''. In 1974, Bhutto initiated a more aggressive diplomatic offensive on the United States and the Western world over nuclear issues. Writing to world and Western leaders, Bhutto conveyed:

Roughly two weeks after the

1971 winter war, on 20 January 1972, Bhutto convened a conference of nuclear scientists and engineers at

Multan

Multan is the List of cities in Punjab, Pakistan by population, fifth-most populous city in the Punjab, Pakistan, Punjab province of Pakistan. Located along the eastern bank of the Chenab River, it is the List of cities in Pakistan by populatio ...

. While at the Multan meeting, scientists wondered why the President, who had much on his hands in those trying days, was paying so much attention to scientists and engineers in the nuclear field. At the meeting, Bhutto slowly discussed the recent war and the country's future, emphasizing the great mortal danger the country faced. As the academicians listened carefully, Bhutto stated, "Look, we're going to have the

bomb

A bomb is an explosive weapon that uses the exothermic reaction of an explosive material to provide an extremely sudden and violent release of energy. Detonations inflict damage principally through ground- and atmosphere-transmitted mechan ...

". He asked them, "Can you give it to me? And how long will it take to make a bomb?"

Before the 1970s, nuclear deterrence was well-established under the government of

Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy

Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy (8 September 18925 December 1963) was an East Pakistani barrister, politician and statesman who served as the Prime Minister of Pakistan from 1956 to 1957 and before that as the Prime Minister of Bengal from 1946 to ...

, but it was entirely peaceful and dedicated to

civilian power needs. Bhutto, in his book ''The Myth of Independence'' in 1969, wrote:

After India's nuclear test—codenamed

''Smiling Buddha''—in May 1974, Bhutto sensed and saw this test as the final anticipation for Pakistan's death.

In a press conference held shortly after India's nuclear test, Bhutto said, "India's nuclear program is designed to intimidate Pakistan and establish "''hegemony in the subcontinent''". Despite Pakistan's limited financial resources, Bhutto was so enthusiastic about the nuclear energy project that he is reported to have said "''Pakistanis will eat grass but make a nuclear bomb''".

The militarization of the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission was initiated on 20 January 1972 and, in its initial years, was implemented by Pakistan Army's

Chief of Army Staff

Chief may refer to:

Title or rank

Military and law enforcement

* Chief master sergeant, the ninth, and highest, enlisted rank in the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Space Force

* Chief of police, the head of a police department

* Chief of the boat ...

General

Tikka Khan

Tikka Khan, also known as the Butcher of Bengal.Tikka Khan title:

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

* (; 10 February 1915 – 28 March 2002) was a Pakistani military officer and war criminal who served as the first Chief of the Army Staff (Pakistan), chief of the a ...

. The

Karachi Nuclear Power Plant

The Karachi Nuclear Power Plant (or KANUPP) is a large commercial nuclear power plant located at the Paradise Point in Karachi, Sindh, Pakistan.

Officially known as Karachi Nuclear Power Complex, the power generation site is composed of three ...

(KANUPP-I) was inaugurated by Bhutto during his role as the President of Pakistan at the end of 1972.

The nuclear weapons program was set up loosely based on the Manhattan Project of the 1940s under the administrative control of Bhutto.

Senior academic scientists had direct access to Bhutto, who kept him informed about every inch of the development. Bhutto's Science Advisor,

Abdus Salam

Mohammad Abdus Salam Salam adopted the forename "Mohammad" in 1974 in response to the anti-Ahmadiyya decrees in Pakistan, similarly he grew his beard. (; ; 29 January 192621 November 1996) was a Pakistani theoretical physicist. He shared the 1 ...

's office was also set up in Bhutto's Prime Minister Secretariat.

On Bhutto's request, Salam had established and led the Theoretical Physics Group (TPG) that marked the beginning of the nuclear deterrent program. The TPG designed and developed the nuclear weapons as well as the entire program.

Later, Munir Ahmad Khan had him personally approved the budget for the development of the programme.

Wanting a capable administrator, Bhutto sought Lieutenant-General

Rahimuddin Khan

Rahimuddin Khan (21 July 1926 – 22 August 2022) was a four-star rank Pakistani general who briefly served as the 16th Governor of Sindh in 1988. Previously, he had served as the fourth Chairman Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee from 1984 to 19 ...

to chair the commission, which Rahimuddin declined, in 1971. Instead, in January 1972, Bhutto chose a U.S.-trained

nuclear engineer

Nuclear engineering is the engineering discipline concerned with designing and applying systems that utilize the energy released by nuclear processes.

The most prominent application of nuclear engineering is the generation of electricity. Worldwide ...

, Munir Khan, as chairman of the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission (PAEC). Bhutto realized he wanted an administrator who understood the scientific and economic needs of this technologically ambitious program. Since 1965, Munir Khan had developed an extremely close and trusted relationship with Bhutto, and even after his death, Benazir and Murtaza Bhutto were instructed by their father to keep in touch with Munir Khan. In the spring of 1976,

Kahuta Research Facility, then known as

Engineering Research Laboratories

The Dr. A. Q. Khan Research Laboratories (shortened as KRL), is a federally funded research and development laboratory located in Kahuta at a short distance from Rawalpindi in Punjab, Pakistan. Established in 1976, the laboratory is best known ...

(ERL), as part of codename ''

Project-706

Project-706, also known as Project-786 was the codename of a research and development program to develop Pakistan's first nuclear weapons. The program was initiated by Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto in 1974 in response to the Indian nuclear ...

'', was also established by Bhutto and brought under nuclear scientist

Abdul Qadeer Khan

Abdul Qadeer Khan (1 April 1936 – 10 October 2021) was a Pakistani Nuclear physics, nuclear physicist and metallurgist, metallurgical engineer. He is colloquially known as the "father of Pakistan and weapons of mass destruction, Pakistan's ...

and the

Pakistan Army Corps of Engineers

The Pakistan Army Corps of Engineers is a military administrative and the engineering staff branch of the Pakistan Army. The Corps of Engineers is generally associated with the civil engineering works, dams, canals, and flood protection, ...

'

Lieutenant-General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the battlefield, who was normall ...

Zahid Ali Akbar

Zahid Ali Akbar (; b. 1933) , is a former engineering officer in the Pakistan Army Corps of Engineers, known for his role in Pakistan's acquisition of nuclear weapons, and directing the Engineering Research Laboratories (ERL), a top secret rese ...

.

Because Pakistan, under Bhutto, was not a signatory or party to the

Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty

The Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, commonly known as the Non-Proliferation Treaty or NPT, is an international treaty whose objective is to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons and weapons technology, to promote cooperatio ...

(NPT), the

Nuclear Suppliers Group

The Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) is a multilateral export control regime and a group of nuclear supplier countries that seek to contribute to the non-proliferation of nuclear weapons through the implementation of two sets of Guidelines for nuc ...

(NSG),

Commissariat à l'énergie atomique

The French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission, or CEA ( French: Commissariat à l'énergie atomique et aux énergies alternatives), is a French public government-funded research organisation in the areas of energy, defense and sec ...

(CEA), and

British Nuclear Fuels

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and cultur ...

(BNFL) had immediately cancelled fuel reprocessing plant projects with PAEC. According to

Causar Nyäzie, the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission officials had misled Bhutto, and he embarked on a long journey to try to obtain a nuclear fuel reprocessing plant from France.

[ Niazi, Maulana Kausar (1991]

''Last Days of Premier Bhutto''

. Chapter 9: The Reprocessing Plant—The Inside Story It was on the advice of A. Q. Khan that no fuel existed to reprocess and urged Bhutto to follow his pursuit of uranium enrichment.

Bhutto tried to show he was still interested in that expensive route and was relieved when Kissinger persuaded the French to cancel the deal.

Bhutto had trusted Munir Ahmad Khan's plans to develop the programme ingeniously, and the mainstream goal of showing such interest in the French reprocessing plant was to give time to PAEC scientists to gain expertise in building its own reprocessing plants. By the time France's CEA cancelled the project, the PAEC had acquired 95% of the detailed plans of the plant and materials.

Munir Ahmad Khan and

Ishfaq Ahmad

Ishfaq Ahmad (3 November 1930 – 18 January 2018) , was a Pakistani nuclear physicist, emeritus professor of high-energy physics at the National Centre for Physics, and former science advisor to the Government of Pakistan.

A versatile theor ...

believed that, since PAEC had acquired most of the detailed plans, work, and materials, the PAEC, based on that 95% work, could build the plutonium reprocessing reactors on its own. Pakistan should stick to its original plan, the plutonium route.

Bhutto did not disagree but saw an advantage in establishing another parallel programme, the uranium enrichment programme under Abdul Qadeer Khan.

Both Munir Khan and Ahmed had shown their concern over Abdul Qadeer Khan's suspected activities, but Bhutto backed Khan when Bhutto maintained that: "No less than any other nation did what Abdul Qadeer Khan (is) doing; the Soviets and Chinese; the British and the French; the Indians and the Israelis; stole the nuclear weapons designs previously in the past and no one questioned them but rather tend to be quiet. We are not stealing what they (illegally) stole in the past (as referring the nuclear weapon designs) but we're taking a small machine which is not useful for making the atomic bomb but for a fuel".

International pressure was difficult to counter at that time, and Bhutto, with the help of Munir Ahmad Khan and Aziz Ahmed, tackled the intense heated criticism and diplomatic war with the United States at numerous fronts—while the progress on nuclear weapons remained highly classified.

During this pressure, Aziz Ahmed played a significant role by convincing the consortium industries to sell and export sensitive electronic components before the United States could approach them and try to prevent the consortium industries from exporting such equipment and components.

Bhutto slowly reversed and thwarted the United States' any attempt to infiltrate the programme as he had expelled many of the

American diplomatic officials in the country, under ''Operation Sun Rise'', authorised by Bhutto under

''ISI''.

On the other hand, Bhutto intensified his staunch support and blindly backed Abdul Qadeer Khan to quietly bring the

Urenco

The Urenco Group is a British-German-Dutch nuclear fuel consortium operating several uranium enrichment plants in Germany, the Netherlands, United States, and United Kingdom. It supplies nuclear power stations in about 15 countries, and stat ...

's weapon-grade technology to Pakistan, keeping the Kahuta Laboratories hidden from the outside world.

Regional rivals such as India and the Soviet Union had no basic intelligence on Pakistan's

nuclear energy project during the 1970s, and Bhutto's intensified clandestine efforts seemed to pay off in 1978 when the programme was fully matured.

In a thesis presented in ''The Myth of Independence'', Bhutto argued that nuclear weapons would enable India to deploy its

Air Force

An air force in the broadest sense is the national military branch that primarily conducts aerial warfare. More specifically, it is the branch of a nation's armed services that is responsible for aerial warfare as distinct from an army aviati ...

warplanes with small

battlefield nuclear devices against the Pakistan Army cantonments, armoured and infantry columns, PAF bases, and nuclear and military industrial facilities.

[ Bhutto, pp. 159–359] The Indian Air Force would not face adverse reactions from the world community as long as civilian casualties could be minimized. This strategy aimed to lead India to defeat Pakistan, compel its armed forces into a humiliating surrender, and annex the

Northern Areas

Gilgit-Baltistan (; ), formerly known as the Northern Areas, is a region administered by Pakistan as an administrative territory and consists of the northern portion of the larger Kashmir region, which has been the subject of a dispute bet ...

of Pakistan and

Azad Kashmir

Azad Jammu and Kashmir (), abbreviated as AJK and colloquially referred to as simply Azad Kashmir ( ), is a region administered by Pakistan as a nominally self-governing entitySee:

*

*

* and constituting the western portion of the larger ...

. Subsequently, India would partition Pakistan into smaller states based on ethnic divisions, marking the resolution of the "Pakistan problem" once and for all.

By the time Bhutto was ousted, this crash programme had fully matured in terms of technical development and scientific efforts.

By 1977, PAEC and KRL had constructed their uranium enrichment and plutonium reprocessing plants, and the selection for test sites at

Chagai Hills

The Chagai Hills is a granite mountain range located in the Chagai District in Balochistan, Pakistan. The Chagai Hills face the border wall at the Durand Line– the official name of Afghanistan–Pakistan border.

The highest peak, Malik Naru, ...

was completed by the PAEC. In 1977, the PAEC's Theoretical Physics Group had completed the design of the first fission weapon, and KRL scientists succeeded in

electromagnetic isotope separation of Uranium fissile isotopes. Despite this, little progress had been made in the development of weapons, and Pakistan's nuclear arsenal was actually created during General Zia-ul-Haq's military regime, overseen by several Naval admirals, Army and Air Force generals, including

Ghulam Ishaq Khan

Ghulam Ishaq Khan (20 January 1915 – 27 October 2006), commonly known by his initials GIK, was a Pakistani bureaucrat, politician and statesman who served as the seventh President of Pakistan from 1988 to 1993. He previously served as Chairm ...

.