Quackery on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Quackery, often synonymous with health fraud, is the promotion of

Quackery, often synonymous with health fraud, is the promotion of

With little understanding of the causes and mechanisms of illnesses, widely marketed "cures" (as opposed to locally produced and locally used remedies), often referred to as

With little understanding of the causes and mechanisms of illnesses, widely marketed "cures" (as opposed to locally produced and locally used remedies), often referred to as  In 1909, in an attempt to stop the sale of quack medicines, the

In 1909, in an attempt to stop the sale of quack medicines, the  Advertising claims similar to those of Radam can be found throughout the 18th, 19th, 20th and 21st centuries. "Dr." Sibley, an English patent medicine seller of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, even went so far as to claim that his Reanimating Solar Tincture would, as the name implies, "restore life in the event of sudden death". Another English quack, "Dr. Solomon" claimed that his Cordial Balm of Gilead cured almost anything, but was particularly effective against all venereal complaints, from

Advertising claims similar to those of Radam can be found throughout the 18th, 19th, 20th and 21st centuries. "Dr." Sibley, an English patent medicine seller of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, even went so far as to claim that his Reanimating Solar Tincture would, as the name implies, "restore life in the event of sudden death". Another English quack, "Dr. Solomon" claimed that his Cordial Balm of Gilead cured almost anything, but was particularly effective against all venereal complaints, from

"Quackery is the promotion of false and unproven health schemes for a profit. It is rooted in the traditions of the marketplace", with "commercialism overwhelming professionalism in the marketing of alternative medicine". ''Quackery'' is most often used to denote the peddling of the "cure-alls" described above. Quackery is an ongoing problem that can be found in any culture and in every medical tradition. Unlike other advertising mediums, rapid advancements in communication through the Internet have opened doors for an unregulated market of quack cures and marketing campaigns rivaling the early 20th century. Most people with an

"Quackery is the promotion of false and unproven health schemes for a profit. It is rooted in the traditions of the marketplace", with "commercialism overwhelming professionalism in the marketing of alternative medicine". ''Quackery'' is most often used to denote the peddling of the "cure-alls" described above. Quackery is an ongoing problem that can be found in any culture and in every medical tradition. Unlike other advertising mediums, rapid advancements in communication through the Internet have opened doors for an unregulated market of quack cures and marketing campaigns rivaling the early 20th century. Most people with an

"Evidence Check 2: Homeopathy"

/ref> Ayurveda is deemed to be pseudoscientific. Much of the research on postural yoga has taken the form of preliminary studies or clinical trials of low methodological quality; there is no conclusive therapeutic effect except in back pain. Naturopathy is considered to be a form of pseudo-scientific quackery,Sources documenting the same: * * * * * * ineffective and possibly harmful, with a plethora of ethical concerns about the very practice. Unani lacks biological plausibility and is considered to be pseudo-scientific quackery, as well.

While quackery is often aimed at the aged or chronically ill, it can be aimed at all age groups, including teens, and the FDA has mentioned some areas where potential quackery may be a problem: breast developers, weight loss, steroids and growth hormones, tanning and tanning pills, hair removal and growth, and look-alike drugs.

In 1992, the president of The National Council Against Health Fraud, William T. Jarvis, wrote in '' Clinical Chemistry'' that:

While quackery is often aimed at the aged or chronically ill, it can be aimed at all age groups, including teens, and the FDA has mentioned some areas where potential quackery may be a problem: breast developers, weight loss, steroids and growth hormones, tanning and tanning pills, hair removal and growth, and look-alike drugs.

In 1992, the president of The National Council Against Health Fraud, William T. Jarvis, wrote in '' Clinical Chemistry'' that:

For those in the practice of any medicine, to allege quackery is to level a serious objection to a particular form of practice. Most developed countries have a governmental agency, such as the

For those in the practice of any medicine, to allege quackery is to level a serious objection to a particular form of practice. Most developed countries have a governmental agency, such as the  Individuals and non-governmental agencies are active in attempts to expose quackery. According to John C. Norcross et al. less is consensus about ineffective "compared to effective procedures" but identifying both "pseudoscientific, unvalidated, or 'quack' psychotherapies" and "assessment measures of questionable validity on psycho-metric grounds" was pursued by various authors. The

Individuals and non-governmental agencies are active in attempts to expose quackery. According to John C. Norcross et al. less is consensus about ineffective "compared to effective procedures" but identifying both "pseudoscientific, unvalidated, or 'quack' psychotherapies" and "assessment measures of questionable validity on psycho-metric grounds" was pursued by various authors. The

There have been several suggested reasons why quackery is accepted by patients in spite of its lack of effectiveness:

;Ignorance: Those who perpetuate quackery may do so to take advantage of ignorance about conventional medical treatments versus alternative treatments, or may themselves be ignorant regarding their own claims. Mainstream medicine has produced many remarkable advances, so people may tend to also believe groundless claims.

;

There have been several suggested reasons why quackery is accepted by patients in spite of its lack of effectiveness:

;Ignorance: Those who perpetuate quackery may do so to take advantage of ignorance about conventional medical treatments versus alternative treatments, or may themselves be ignorant regarding their own claims. Mainstream medicine has produced many remarkable advances, so people may tend to also believe groundless claims.

;

*

*

Linus Pauling: Nobel Laureate for Peace and Chemistry 1901–1994

* Doctor John Henry Pinkard (1866–1934) was a

"The Skeptics Dictionary"

New York: Wiley. * Della Sala, 1999. ''Mind Myths: Exploring Popular Assumptions about the Mind and Brain''. New York: Wiley. * Eisner, 2000. ''The Death of Psychotherapy; From Freud to Alien Abductions''. Westport, CT: Praegner. * Lilienfeld, SO., Lynn, SJ., Lohr, JM. 2003. ''Science and Pseudoscience in Clinical Psychology''. New York: Guildford *

Quackwatch

'Miracle' Health Claims: Add a Dose of Skepticism

Article at the

Quackery, often synonymous with health fraud, is the promotion of

Quackery, often synonymous with health fraud, is the promotion of fraud

In law, fraud is intent (law), intentional deception to deprive a victim of a legal right or to gain from a victim unlawfully or unfairly. Fraud can violate Civil law (common law), civil law (e.g., a fraud victim may sue the fraud perpetrato ...

ulent or ignorant medical practices. A quack is a "fraudulent or ignorant pretender to medical skill" or "a person who pretends, professionally or publicly, to have skill, knowledge, qualification or credentials they do not possess; a charlatan

A charlatan (also called a swindler or mountebank) is a person practicing quackery or a similar confidence trick in order to obtain money, power, fame, or other advantages through pretense or deception. One example of a charlatan appears in t ...

or snake oil

Snake oil is a term used to describe False advertising, deceptive marketing, health care fraud, or a scam. Similarly, snake oil salesman is a common label used to describe someone who sells, promotes, or is a general proponent of some valueless ...

salesman". The term ''quack'' is a clipped form of the archaic term ', derived from a "hawker of salve" or rather somebody who boasted about their salves, more commonly known as ointments. In the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

the term ''quack'' meant "shouting". The quacksalvers sold their wares at markets by shouting to gain attention.

Common elements of general quackery include questionable diagnoses using questionable diagnostic tests, as well as untested or refuted treatments, especially for serious diseases such as cancer

Cancer is a group of diseases involving Cell growth#Disorders, abnormal cell growth with the potential to Invasion (cancer), invade or Metastasis, spread to other parts of the body. These contrast with benign tumors, which do not spread. Po ...

. Quackery is often described as "health fraud" with the salient characteristic of aggressive promotion.

Definition

Psychiatrist and authorStephen Barrett

Stephen Joel Barrett (; born 1933) is an American retired psychiatrist, author, and consumer advocate best known for his work combatting health fraud and promoting evidence-based medicine. He founded Quackwatch, a network of websites that cri ...

of Quackwatch defines quackery as "the promotion of unsubstantiated methods that lack a scientifically plausible rationale" and more broadly as:

In addition to the ethical problems of promising benefits that are not likely to occur, quackery might cause people to forego treatments that are more likely to help them, in favor of ineffective treatments given by the "quack".

American pediatrician Paul Offit has proposed four ways in which alternative medicine

Alternative medicine refers to practices that aim to achieve the healing effects of conventional medicine, but that typically lack biological plausibility, testability, repeatability, or supporting evidence of effectiveness. Such practices are ...

"becomes quackery": Also titled

# "by recommending against conventional therapies that are helpful."

# "by promoting potentially harmful therapies without adequate warning."

# "by draining patients' bank accounts ..."

# "by promoting magical thinking

Magical thinking, or superstitious thinking, is the belief that unrelated events are causally connected despite the absence of any plausible causal link between them, particularly as a result of supernatural effects. Examples include the idea tha ...

..."

Since it is difficult to distinguish between those who knowingly promote unproven medical therapies and those who are mistaken as to their effectiveness, United States courts have ruled in defamation

Defamation is a communication that injures a third party's reputation and causes a legally redressable injury. The precise legal definition of defamation varies from country to country. It is not necessarily restricted to making assertions ...

cases that accusing someone of quackery or calling a practitioner a ''quack'' is not equivalent to accusing that person of committing medical fraud. However, the FDA makes little distinction between the two. To be considered a fraud, it is not strictly necessary for one to know they are misrepresenting the benefits or risks of the services offered.

Quacksalver

Unproven, usually ineffective, and sometimes dangerous medicines and treatments have been peddled throughout human history. Theatrical performances were sometimes given to enhance the credibility of purported medicines. Grandiose claims were made for what could be humble materials indeed: for example, in the mid-19th century '' revalenta arabica'' was advertised as having extraordinary restorative virtues as an empirical diet for invalids; despite its impressive name and many glowing testimonials it was in truth only ordinarylentil

The lentil (''Vicia lens'' or ''Lens culinaris'') is an annual plant, annual legume grown for its Lens (geometry), lens-shaped edible seeds or ''pulses'', also called ''lentils''. It is about tall, and the seeds grow in Legume, pods, usually w ...

flour, sold to the gullible at many times the true cost.

Even where no fraud was intended, quack remedies often contained no effective ingredients whatsoever. Some remedies contained substances such as opium

Opium (also known as poppy tears, or Lachryma papaveris) is the dried latex obtained from the seed Capsule (fruit), capsules of the opium poppy ''Papaver somniferum''. Approximately 12 percent of opium is made up of the analgesic alkaloid mor ...

, alcohol and honey, which would have given symptomatic relief but had no curative properties. Some would have addictive qualities to entice the buyer to return. The few effective remedies sold by quacks included emetics, laxatives and diuretics. Some ingredients did have medicinal effects: mercury, silver

Silver is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Ag () and atomic number 47. A soft, whitish-gray, lustrous transition metal, it exhibits the highest electrical conductivity, thermal conductivity, and reflectivity of any metal. ...

and arsenic

Arsenic is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol As and atomic number 33. It is a metalloid and one of the pnictogens, and therefore shares many properties with its group 15 neighbors phosphorus and antimony. Arsenic is not ...

compounds may have helped some infections and infestations; willow

Willows, also called sallows and osiers, of the genus ''Salix'', comprise around 350 species (plus numerous hybrids) of typically deciduous trees and shrubs, found primarily on moist soils in cold and temperate regions.

Most species are known ...

bark

Bark may refer to:

Common meanings

* Bark (botany), an outer layer of a woody plant such as a tree or stick

* Bark (sound), a vocalization of some animals (which is commonly the dog)

Arts and entertainment

* ''Bark'' (Jefferson Airplane album), ...

contains salicylic acid

Salicylic acid is an organic compound with the formula HOC6H4COOH. A colorless (or white), bitter-tasting solid, it is a precursor to and a active metabolite, metabolite of acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin). It is a plant hormone, and has been lis ...

, chemically closely related to aspirin

Aspirin () is the genericized trademark for acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) used to reduce pain, fever, and inflammation, and as an antithrombotic. Specific inflammatory conditions that aspirin is ...

; and the quinine

Quinine is a medication used to treat malaria and babesiosis. This includes the treatment of malaria due to ''Plasmodium falciparum'' that is resistant to chloroquine when artesunate is not available. While sometimes used for nocturnal leg ...

contained in Jesuit's bark was an effective treatment for malaria

Malaria is a Mosquito-borne disease, mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects vertebrates and ''Anopheles'' mosquitoes. Human malaria causes Signs and symptoms, symptoms that typically include fever, Fatigue (medical), fatigue, vomitin ...

and other fevers. However, knowledge of appropriate uses and dosages was limited.

Criticism of quackery in academia

Theevidence-based medicine

Evidence-based medicine (EBM) is "the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients. It means integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available exte ...

community has criticized the infiltration of alternative medicine

Alternative medicine refers to practices that aim to achieve the healing effects of conventional medicine, but that typically lack biological plausibility, testability, repeatability, or supporting evidence of effectiveness. Such practices are ...

into mainstream academic medicine, education, and publications, accusing institutions of "diverting research time, money, and other resources from more fruitful lines of investigation in order to pursue a theory that has no basis in biology."

For example, David Gorski criticized Brian M. Berman, founder of the University of Maryland Center for Integrative Medicine, for writing that "There sevidence that both real acupuncture and sham acupuncture remore effective than no treatment and that acupuncture can be a useful supplement to other forms of conventional therapy for low back pain." He also castigated editors and peer reviewers at the ''New England Journal of Medicine

''The New England Journal of Medicine'' (''NEJM'') is a weekly medical journal published by the Massachusetts Medical Society. Founded in 1812, the journal is among the most prestigious peer-reviewed medical journals. Its 2023 impact factor was ...

'' for allowing it to be published, since it effectively recommended deliberately misleading patients in order to achieve a known placebo effect

A placebo ( ) can be roughly defined as a sham medical treatment. Common placebos include inert tablets (like sugar pills), inert injections (like saline), sham surgery, and other procedures.

Placebos are used in randomized clinical trials ...

.

History in Europe and the United States

With little understanding of the causes and mechanisms of illnesses, widely marketed "cures" (as opposed to locally produced and locally used remedies), often referred to as

With little understanding of the causes and mechanisms of illnesses, widely marketed "cures" (as opposed to locally produced and locally used remedies), often referred to as patent medicine

A patent medicine (sometimes called a proprietary medicine) is a non-prescription medicine or medicinal preparation that is typically protected and advertised by a trademark and trade name, and claimed to be effective against minor disorders a ...

s, first came to prominence during the 17th and 18th centuries in Britain and the British colonies, including those in North America. Daffy's Elixir and Turlington's Balsam were among the first products that used branding (e.g. using highly distinctive containers) and mass marketing to create and maintain markets. A similar process occurred in other countries of Europe around the same time, for example with the marketing of Eau de Cologne

Eau de Cologne (; German: ''Kölnisch Wasser'' ; meaning "Water from Cologne") or simply cologne is a perfume originating in Cologne, Germany. Originally mixed by Johann Maria Farina (Giovanni Maria Farina) in 1709, it has since come to be a gene ...

as a cure-all medicine by Johann Maria Farina and his imitators. Patent medicines often contained alcohol

Alcohol may refer to:

Common uses

* Alcohol (chemistry), a class of compounds

* Ethanol, one of several alcohols, commonly known as alcohol in everyday life

** Alcohol (drug), intoxicant found in alcoholic beverages

** Alcoholic beverage, an alco ...

or opium

Opium (also known as poppy tears, or Lachryma papaveris) is the dried latex obtained from the seed Capsule (fruit), capsules of the opium poppy ''Papaver somniferum''. Approximately 12 percent of opium is made up of the analgesic alkaloid mor ...

, which, while presumably not curing the diseases for which they were sold as a remedy, did make the imbibers feel better and confusedly appreciative of the product.

The number of internationally marketed quack medicines increased in the later 18th century; the majority of them originated in Britain and were exported throughout the British Empire. By 1830, British parliamentary records list over 1,300 different "proprietary medicines", the majority of which were "quack" cures by modern standards.

A Dutch organisation that opposes quackery, ' (VtdK), was founded in 1881, making it the oldest organisation of this kind in the world. It has published its magazine ' (''Dutch Magazine against Quackery'') ever since. In these early years the played a part in the professionalisation of medicine. Its efforts in the public debate helped to make the Netherlands one of the first countries with governmental drug regulation.

In 1909, in an attempt to stop the sale of quack medicines, the

In 1909, in an attempt to stop the sale of quack medicines, the British Medical Association

The British Medical Association (BMA) is a registered trade union and professional body for physician, doctors in the United Kingdom. It does not regulate or certify doctors, a responsibility which lies with the General Medical Council. The BMA ...

published ''Secret Remedies, What They Cost And What They Contain''. This publication was originally a series of articles published in the ''British Medical Journal'' between 1904 and 1909. The publication was composed of 20 chapters, organising the work by sections according to the ailments the medicines claimed to treat. Each remedy was tested thoroughly, the preface stated: "Of the accuracy of the analytical data there can be no question; the investigation has been carried out with great care by a skilled analytical chemist." The book did lead to the end of some of the quack cures, but some survived the book by several decades. For example, Beecham's Pills, which according to the British Medical Association contained in 1909 only aloes, ginger and soap, but claimed to cure 31 medical conditions, were sold until 1998. The failure of the medical establishment to stop quackery was rooted in the difficulty of defining what precisely distinguished real medicine, and in the appeals that quackery held out to consumers.

British patent medicines lost their dominance in the United States when they were denied access to the Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies were the British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America which broke away from the British Crown in the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), and joined to form the United States of America.

The Thirteen C ...

markets during the American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

, and lost further ground for the same reason during the War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

. From the early 19th century "home-grown" American brands started to fill the gap, reaching their peak in the years after the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

. British medicines never regained their previous dominance in North America, and the subsequent era of mass marketing of American patent medicine

A patent medicine (sometimes called a proprietary medicine) is a non-prescription medicine or medicinal preparation that is typically protected and advertised by a trademark and trade name, and claimed to be effective against minor disorders a ...

s is usually considered to have been a "golden age" of quackery in the United States. This was mirrored by similar growth in marketing of quack medicines elsewhere in the world.

In the United States, false medicines in this era were often denoted by the slang term snake oil

Snake oil is a term used to describe False advertising, deceptive marketing, health care fraud, or a scam. Similarly, snake oil salesman is a common label used to describe someone who sells, promotes, or is a general proponent of some valueless ...

, a reference to sales pitches for the false medicines that claimed exotic ingredients provided the supposed benefits. Those who sold them were called "snake oil salesmen", and usually sold their medicines with a fervent pitch similar to a fire and brimstone religious sermon. They often accompanied other theatrical and entertainment productions that traveled as a road show from town to town, leaving quickly before the falseness of their medicine was discovered. Not all quacks were restricted to such small-time businesses however, and a number, especially in the United States, became enormously wealthy through national and international sales of their products.

In 1875, the ''Pacific Medical and Surgical Journal'' complained:

One among many examples is William Radam, a German immigrant to the US, who, in the 1880s, started to sell his "Microbe Killer" throughout the United States and, soon afterwards, in Britain and throughout the British colonies. His concoction was widely advertised as being able to "cure all diseases", and this phrase was even embossed on the glass bottles the medicine was sold in. In fact, Radam's medicine was a therapeutically useless (and in large quantities actively poisonous) dilute solution of sulfuric acid

Sulfuric acid (American spelling and the preferred IUPAC name) or sulphuric acid (English in the Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth spelling), known in antiquity as oil of vitriol, is a mineral acid composed of the elements sulfur, oxygen, ...

, coloured with a little red wine. Radam's publicity material, particularly his books, provide an insight into the role that pseudoscience

Pseudoscience consists of statements, beliefs, or practices that claim to be both scientific and factual but are incompatible with the scientific method. Pseudoscience is often characterized by contradictory, exaggerated or unfalsifiable cl ...

played in the development and marketing of "quack" medicines towards the end of the 19th century.

gonorrhea

Gonorrhoea or gonorrhea, colloquially known as the clap, is a sexually transmitted infection (STI) caused by the bacterium ''Neisseria gonorrhoeae''. Infection may involve the genitals, mouth, or rectum.

Gonorrhea is spread through sexual c ...

to onanism. Although it was basically just brandy flavoured with herbs, the price of a bottle was a half guinea (£sd

file:Guildhall Museum Collection- Drusilla Dunford Money Table Sampler 3304.JPG, A Sampler (needlework), sampler in the Rochester Guildhall, Guildhall Museum of Rochester, Medway, Rochester illustrates the conversion between pence and shillings ...

system) in 1800, equivalent to over £ ($) in 2014.

Not all patent medicines were without merit. Turlingtons Balsam of Life, first marketed in the mid-18th century, did have genuinely beneficial properties. This medicine continued to be sold under the original name into the early 20th century, and can still be found in the British and American pharmacopoeia

A pharmacopoeia, pharmacopeia, or pharmacopoea (or the typographically obsolete rendering, ''pharmacopœia''), meaning "drug-making", in its modern technical sense, is a reference work containing directions for the identification of compound med ...

s as "Compound tincture of benzoin". In these cases, the treatments likely lacked empirical support when they were introduced to the market, and their benefits were simply a convenient coincidence discovered after the fact.

The end of the road for the quack medicines now considered grossly fraudulent in the nations of North America and Europe came in the early 20th century. 21 February 1906 saw the passage into law of the Pure Food and Drug Act

The s:Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, also known as the Wiley Act and Harvey Washington Wiley, Dr. Wiley's Law, was the first of a series of significant consumer protection laws enacted by the United States Con ...

in the United States. This was the result of decades of campaigning by both government departments and the medical establishment, supported by a number of publishers and journalists (one of the most effective was Samuel Hopkins Adams

Samuel Hopkins Adams (January 26, 1871 – November 16, 1958) was an American writer who was an investigative journalist and muckraker.

Background

Adams was born in Dunkirk, New York. Adams was a muckraker, known for exposing public-health in ...

, who wrote "The Great American Fraud" series in ''Collier's

}

''Collier's'' was an American general interest magazine founded in 1888 by Peter F. Collier, Peter Fenelon Collier. It was launched as ''Collier's Once a Week'', then renamed in 1895 as ''Collier's Weekly: An Illustrated Journal'', shortened i ...

'' in 1905). This American Act was followed three years later by similar legislation in Britain and in other European nations. Between them, these laws began to remove the more outrageously dangerous contents from patent and proprietary medicines, and to force quack medicine proprietors to stop making some of their more blatantly dishonest claims. The Act, however, left advertising and claims of effectiveness unregulated as the Supreme Court interpreted it to mean only that ingredients on labels had to be accurate. Language in the 1912 Sherley Amendment, meant to close this loophole, was limited to regulating claims that were false and fraudulent, creating the need to show intent. Throughout the early 20th century, the American Medical Association

The American Medical Association (AMA) is an American professional association and lobbying group of physicians and medical students. This medical association was founded in 1847 and is headquartered in Chicago, Illinois. Membership was 271,660 ...

collected material on medical quackery, and one of their members and medical editors in particular, Arthur J. Cramp, devoted his career to criticizing such products. The AMA's Department of Investigation closed in 1975, but their only archive open to non-members remains, the American Medical Association Health Fraud and Alternative Medicine Collection.

"Medical quackery and promotion of nostrums and worthless drugs were among the most prominent abuses that led to formal self-regulation in business and, in turn, to the creation of the Better Business Bureau

The Better Business Bureau (BBB) is an American private, 501(c)(6) nonprofit organization founded in 1912. BBB's self-described mission is to focus on advancing marketplace trust, consisting of 92 independently incorporated local BBB organizati ...

."

Contemporary culture

"Quackery is the promotion of false and unproven health schemes for a profit. It is rooted in the traditions of the marketplace", with "commercialism overwhelming professionalism in the marketing of alternative medicine". ''Quackery'' is most often used to denote the peddling of the "cure-alls" described above. Quackery is an ongoing problem that can be found in any culture and in every medical tradition. Unlike other advertising mediums, rapid advancements in communication through the Internet have opened doors for an unregulated market of quack cures and marketing campaigns rivaling the early 20th century. Most people with an

"Quackery is the promotion of false and unproven health schemes for a profit. It is rooted in the traditions of the marketplace", with "commercialism overwhelming professionalism in the marketing of alternative medicine". ''Quackery'' is most often used to denote the peddling of the "cure-alls" described above. Quackery is an ongoing problem that can be found in any culture and in every medical tradition. Unlike other advertising mediums, rapid advancements in communication through the Internet have opened doors for an unregulated market of quack cures and marketing campaigns rivaling the early 20th century. Most people with an e-mail

Electronic mail (usually shortened to email; alternatively hyphenated e-mail) is a method of transmitting and receiving Digital media, digital messages using electronics, electronic devices over a computer network. It was conceived in the ...

account have experienced the marketing tactics of spamming

Spamming is the use of messaging systems to send multiple unsolicited messages (spam) to large numbers of recipients for the purpose of commercial advertising, non-commercial proselytizing, or any prohibited purpose (especially phishing), or si ...

– in which modern forms of quackery are touted as miraculous remedies for "weight loss" and "sexual enhancement", as well as outlets for medicines of unknown quality.

India

In 2008, the ''Hindustan Times

''Hindustan Times'' is an Indian English language, English-language daily newspaper based in Delhi. It is the flagship publication of HT Media Limited, an entity controlled by the Birla family, and is owned by Shobhana Bhartia, the daughter o ...

'' reported that some officials and doctors estimated that there were more than 40,000 quacks practicing in Delhi

Delhi, officially the National Capital Territory (NCT) of Delhi, is a city and a union territory of India containing New Delhi, the capital of India. Straddling the Yamuna river, but spread chiefly to the west, or beyond its Bank (geography ...

, following outrage over a "multi-state racket where unqualified doctors conducted hundreds of illegal kidney transplants for huge profits." The president of the Indian Medical Association (IMA) in 2008 criticized the central government for failing to address the problem of quackery and for not framing any laws against it.

In 2017, IMA again asked for an antiquackery law with stringent action against those practicing without a license. As of 2024, the government of India is yet to pass an anti-quackery law.

Ministry of Ayush

In 2014, theGovernment of India

The Government of India (ISO 15919, ISO: Bhārata Sarakāra, legally the Union Government or Union of India or the Central Government) is the national authority of the Republic of India, located in South Asia, consisting of States and union t ...

formed a Ministry of AYUSH that includes the seven traditional systems of healthcare.

The Ministry of Ayush (expanded from Ayurveda

Ayurveda (; ) is an alternative medicine system with historical roots in the Indian subcontinent. It is heavily practised throughout India and Nepal, where as much as 80% of the population report using ayurveda. The theory and practice of ayur ...

, Yoga

Yoga (UK: , US: ; 'yoga' ; ) is a group of physical, mental, and spiritual practices or disciplines that originated with its own philosophy in ancient India, aimed at controlling body and mind to attain various salvation goals, as pra ...

, Naturopathy

Naturopathy, or naturopathic medicine, is a form of alternative medicine. A wide array of practices branded as "natural", "non-invasive", or promoting "self-healing" are employed by its practitioners, who are known as naturopaths. Difficult ...

, Unani

Unani or Yunani medicine (Urdu: ''tibb yūnānī'') is Perso-Arabic traditional medicine as practiced in Muslim culture in South Asia and modern day Central Asia. Unani medicine is pseudoscientific.

The term '' Yūnānī'' means 'Greek', ref ...

, Siddha

''Siddha'' (Sanskrit: '; "perfected one") is a term that is used widely in Indian religions and culture. It means "one who is accomplished." It refers to perfected masters who have achieved a high degree of perfection of the intellect as we ...

, Sowa-Rigpa and Homoeopathy

Homeopathy or homoeopathy is a pseudoscientific system of alternative medicine. It was conceived in 1796 by the German physician Samuel Hahnemann. Its practitioners, called homeopaths or homeopathic physicians, believe that a substance that ...

), is purposed with developing education, research and propagation of indigenous alternative medicine systems in India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

. The ministry has faced significant criticism for funding systems that lack biological plausibility and are either untested or conclusively proven as ineffective. Quality of research has been poor, and drugs have been launched without any rigorous pharmacological studies and meaningful clinical trials on Ayurveda or other alternative healthcare systems.

There is no credible efficacy or scientific basis of any of these forms of treatment.Sources that criticize the entirety of AYUSH as a pseudo-scientific venture:

*

*

*

*

*

* A strong consensus prevails among the scientific community that homeopathy

Homeopathy or homoeopathy is a pseudoscientific system of alternative medicine. It was conceived in 1796 by the German physician Samuel Hahnemann. Its practitioners, called homeopaths or homeopathic physicians, believe that a substance that ...

is a pseudo-scientific, unethical and implausible line of treatment.UK Parliamentary Committee Science and Technology Committee �"Evidence Check 2: Homeopathy"

/ref> Ayurveda is deemed to be pseudoscientific. Much of the research on postural yoga has taken the form of preliminary studies or clinical trials of low methodological quality; there is no conclusive therapeutic effect except in back pain. Naturopathy is considered to be a form of pseudo-scientific quackery,Sources documenting the same: * * * * * * ineffective and possibly harmful, with a plethora of ethical concerns about the very practice. Unani lacks biological plausibility and is considered to be pseudo-scientific quackery, as well.

United States

For those in the practice of any medicine, to allege quackery is to level a serious objection to a particular form of practice. Most developed countries have a governmental agency, such as the

For those in the practice of any medicine, to allege quackery is to level a serious objection to a particular form of practice. Most developed countries have a governmental agency, such as the Food and Drug Administration

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA or US FDA) is a List of United States federal agencies, federal agency of the United States Department of Health and Human Services, Department of Health and Human Services. The FDA is respo ...

(FDA) in the US, whose purpose is to monitor and regulate the safety of medications as well as the claims made by the manufacturers of new and existing products, including drugs and nutritional supplements or vitamins. The Federal Trade Commission

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is an independent agency of the United States government whose principal mission is the enforcement of civil (non-criminal) United States antitrust law, antitrust law and the promotion of consumer protection. It ...

(FTC) participates in some of these efforts. To better address less regulated products, in 2000, US President Clinton signed Executive Order 13147 that created the White House Commission on Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Alternative medicine refers to practices that aim to achieve the healing effects of conventional medicine, but that typically lack biological plausibility, testability, repeatability, or supporting evidence of effectiveness. Such practices ar ...

. In 2002, the commission's final report made several suggestions regarding education, research, implementation, and reimbursement as ways to evaluate the risks and benefits of each. As a direct result, more public dollars have been allocated for research into some of these methods.

Individuals and non-governmental agencies are active in attempts to expose quackery. According to John C. Norcross et al. less is consensus about ineffective "compared to effective procedures" but identifying both "pseudoscientific, unvalidated, or 'quack' psychotherapies" and "assessment measures of questionable validity on psycho-metric grounds" was pursued by various authors. The

Individuals and non-governmental agencies are active in attempts to expose quackery. According to John C. Norcross et al. less is consensus about ineffective "compared to effective procedures" but identifying both "pseudoscientific, unvalidated, or 'quack' psychotherapies" and "assessment measures of questionable validity on psycho-metric grounds" was pursued by various authors. The evidence-based practice

Evidence-based practice is the idea that occupational practices ought to be based on scientific evidence. The movement towards evidence-based practices attempts to encourage and, in some instances, require professionals and other decision-makers ...

(EBP) movement in mental health emphasizes the consensus in psychology that psychological practice should rely on empirical research. There are also "anti-quackery" websites, such as Quackwatch, that help consumers evaluate claims. Quackwatch's information is relevant to both consumers and medical professionals.

Presence and acceptance

There have been several suggested reasons why quackery is accepted by patients in spite of its lack of effectiveness:

;Ignorance: Those who perpetuate quackery may do so to take advantage of ignorance about conventional medical treatments versus alternative treatments, or may themselves be ignorant regarding their own claims. Mainstream medicine has produced many remarkable advances, so people may tend to also believe groundless claims.

;

There have been several suggested reasons why quackery is accepted by patients in spite of its lack of effectiveness:

;Ignorance: Those who perpetuate quackery may do so to take advantage of ignorance about conventional medical treatments versus alternative treatments, or may themselves be ignorant regarding their own claims. Mainstream medicine has produced many remarkable advances, so people may tend to also believe groundless claims.

;Placebo effect

A placebo ( ) can be roughly defined as a sham medical treatment. Common placebos include inert tablets (like sugar pills), inert injections (like saline), sham surgery, and other procedures.

Placebos are used in randomized clinical trials ...

: Medicines or treatments known to have no pharmacological effect on a disease can still affect a person's perception of their illness, and this belief in its turn does indeed sometimes have a therapeutic effect, causing the patient's condition to improve. This is ''not'' to say that no real cure of biological illness is effected – "though we might describe a placebo effect as being 'all in the mind', we now know that there is a genuine neurobiological basis to this phenomenon." People report reduced pain, increased well-being, improvement, or even total alleviation of symptoms. For some, the presence of a caring practitioner and the dispensation of medicine is curative in itself.

; Regression fallacy: Lack of understanding that health conditions change with no treatment and attributing changes in ailments to a given therapy.

;Confirmation bias

Confirmation bias (also confirmatory bias, myside bias, or congeniality bias) is the tendency to search for, interpret, favor and recall information in a way that confirms or supports one's prior beliefs or Value (ethics and social sciences), val ...

: The tendency to search for, interpret, or prioritize information in a way that confirms one's beliefs or hypotheses. It is a type of cognitive bias

A cognitive bias is a systematic pattern of deviation from norm (philosophy), norm or rationality in judgment. Individuals create their own "subjective reality" from their perception of the input. An individual's construction of reality, not the ...

and a systematic error of inductive reasoning

Inductive reasoning refers to a variety of method of reasoning, methods of reasoning in which the conclusion of an argument is supported not with deductive certainty, but with some degree of probability. Unlike Deductive reasoning, ''deductive'' ...

.

;Distrust of conventional medicine: Many people, for various reasons, have a distrust of conventional medicine, or of the regulating organizations such as the FDA, or the major drug corporations. For example, "CAM

Cam or CAM may refer to:

Science and technology

* Cam (mechanism), a mechanical linkage which translates motion

* Camshaft, a shaft with a cam

* Camera or webcam, a device that records images or video

In computing

* Computer-aided manufacturin ...

may represent a response to disenfranchisement iscriminationin conventional medical settings and resulting distrust".

;Conspiracy theories

A conspiracy theory is an explanation for an event or situation that asserts the existence of a conspiracy (generally by powerful sinister groups, often political in motivation), when other explanations are more probable.Additional sources:

*

...

: Anti-quackery activists ("quackbusters") are often falsely accused of being part of a huge "conspiracy" to suppress "unconventional" and/or "natural" therapies, as well as those who promote them. It is alleged that this conspiracy is backed and funded by the pharmaceutical industry and the established medical care system – represented by the AMA, FDA, ADA, CDC

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is the national public health agency of the United States. It is a United States federal agency under the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), and is headquartered in Atlanta, ...

, WHO, etc. – for the purpose of preserving their power and increasing their profits. This idea is often held by people with antiscience views.

;Fear of side effects

In medicine, a side effect is an effect of the use of a medicinal drug or other treatment, usually adverse but sometimes beneficial, that is unintended. Herbal and traditional medicines also have side effects.

A drug or procedure usually used ...

: A great variety of pharmaceutical medications can have very distressing side effects, and many people fear surgery

Surgery is a medical specialty that uses manual and instrumental techniques to diagnose or treat pathological conditions (e.g., trauma, disease, injury, malignancy), to alter bodily functions (e.g., malabsorption created by bariatric surgery s ...

and its consequences, so they may opt to shy away from these mainstream treatments.

;Cost: There are some people who simply cannot afford conventional treatment, and seek out a cheaper alternative. Nonconventional practitioners can often dispense treatment at a much lower cost. This is compounded by reduced access to healthcare.

;Desperation: People with a serious or terminal disease, or who have been told by their practitioner that their condition is "untreatable", may react by seeking out treatment, disregarding the lack of scientific proof for its effectiveness, or even the existence of evidence that the method is ineffective or even dangerous. Despair may be exacerbated by the lack of palliative non-curative end-of-life care

End-of-life care is health care provided in the time leading up to a person's death. End-of-life care can be provided in the hours, days, or months before a person dies and encompasses care and support for a person's mental and emotional needs, phy ...

. Between 2012 and 2018 appeals on UK crowdfunding sites for cancer treatment with an alternative health element have raised £8 million. This is described as "a new and lucrative revenue stream for cranks, charlatans, and conmen who prey on the vulnerable."

;Pride: Once people have endorsed or defended a cure, or invested time and money in it, they may be reluctant or embarrassed to admit its ineffectiveness and therefore recommend a treatment that does not work. This is a manifestation of the sunk cost fallacy.

;Fraud: Some practitioners, fully aware of the ineffectiveness of their medicine, may intentionally produce fraudulent scientific studies, for example, thereby confusing any potential consumers as to the effectiveness of the medical treatment.

Deceased persons accused of quackery

*Thomas Allinson

Thomas Richard Allinson (29 March 1858 – 29 November 1918) was an English physician, dietetic reformer, businessman, journalist and vegetarianism activist. He was a proponent of wholemeal (whole grain) bread consumption. His name is still use ...

(1858–1918), founder of naturopathy

Naturopathy, or naturopathic medicine, is a form of alternative medicine. A wide array of practices branded as "natural", "non-invasive", or promoting "self-healing" are employed by its practitioners, who are known as naturopaths. Difficult ...

. His views often brought him into conflict with the Royal College of Physicians

The Royal College of Physicians of London, commonly referred to simply as the Royal College of Physicians (RCP), is a British professional membership body dedicated to improving the practice of medicine, chiefly through the accreditation of ph ...

of Edinburgh and the General Medical Council

The General Medical Council (GMC) is a public body that maintains the official register of physician, medical practitioners within the United Kingdom. Its chief responsibility is to "protect, promote and maintain the health and safety of the pu ...

, particularly his opposition to doctors' frequent use of drugs, his opposition to vaccination and his self-promotion in the press. His views and publication of them led to him being labeled a quack and being struck off by the General Medical Council

The General Medical Council (GMC) is a public body that maintains the official register of physician, medical practitioners within the United Kingdom. Its chief responsibility is to "protect, promote and maintain the health and safety of the pu ...

for ''infamous conduct in a professional respect''.

* Lovisa Åhrberg (1801–1881), the first Swedish female doctor. Åhrberg was met with strong resistance from male doctors and was accused of quackery. During the formal examination, she was acquitted of all charges and allowed to practice medicine in Stockholm even though it was forbidden for women in the 1820s. She later received a medal for her work.

* Johanna Brandt (1876–1964), a South African naturopath who advocated the " Grape Cure" as a cure for cancer.

* John R. Brinkley (1885–1942), a nonphysician and xenotransplant specialist in Kansas, US, who claimed to have discovered a method of effectively transplanting the testicles of goats

The goat or domestic goat (''Capra hircus'') is a species of goat-antelope that is mostly kept as livestock. It was domesticated from the wild goat (''C. aegagrus'') of Southwest Asia and Eastern Europe. The goat is a member of the famil ...

into aging men. After state authorities took steps to shut down his practice, he retaliated by entering politics in 1930 and unsuccessfully running for the office of Governor of Kansas.

* Hulda Regehr Clark (1928–2009), was a controversial naturopath, author, and practitioner of alternative medicine

Alternative medicine refers to practices that aim to achieve the healing effects of conventional medicine, but that typically lack biological plausibility, testability, repeatability, or supporting evidence of effectiveness. Such practices are ...

who claimed to be able to cure all diseases and advocated methods that have no scientific validity.

* Max Gerson

Max Gerson (October 18, 1881 – March 8, 1959) was a German-born American physician who developed the Gerson therapy, a pseudoscientific dietary-based alternative cancer treatment that he falsely claimed could cure cancer and most chronic, ...

(1881–1959), was a German-born American physician who developed a dietary-based alternative cancer treatment that he claimed could cure cancer and most chronic, degenerative diseases. His treatment was called The Gerson Therapy. Most notably, Gerson Therapy was used, unsuccessfully, to treat Jessica Ainscough and Garry Winogrand. According to Quackwatch, Gerson Institute claims of cure are based not on actual documentation of survival, but on "a combination of the doctor's estimate that the departing patient has a 'reasonable chance of surviving', plus feelings that the Institute staff have about the status of people who call in". The American Cancer Society

The American Cancer Society (ACS) is a nationwide non-profit organization dedicated to eliminating cancer. The ACS publishes the journals ''Cancer'', '' CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians'' and '' Cancer Cytopathology''.

History

The society w ...

reports that " ere is no reliable scientific evidence that Gerson therapy is effective ..."

*

* Samuel Hahnemann

Christian Friedrich Samuel Hahnemann ( , ; 10 April 1755 – 2 July 1843) was a German physician, best known for creating the pseudoscientific system of alternative medicine called homeopathy.

Early life

Christian Friedrich Samuel Hahnemann w ...

(1755–1843), founder of homeopathy

Homeopathy or homoeopathy is a pseudoscientific system of alternative medicine. It was conceived in 1796 by the German physician Samuel Hahnemann. Its practitioners, called homeopaths or homeopathic physicians, believe that a substance that ...

. Hahnemann believed that all diseases were caused by " miasms", which he defined as irregularities in the patient's vital force. He also said that illnesses could be treated by substances that in a healthy person produced similar symptoms to the illness, in extremely low concentrations, with the therapeutic effect increasing with dilution and repeated shaking. reprinted in

* Lawrence B. Hamlin (in 1916), was fined under the 1906 US Pure Food and Drug Act

The s:Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, also known as the Wiley Act and Harvey Washington Wiley, Dr. Wiley's Law, was the first of a series of significant consumer protection laws enacted by the United States Con ...

for advertising that his Wizard Oil could kill cancer.

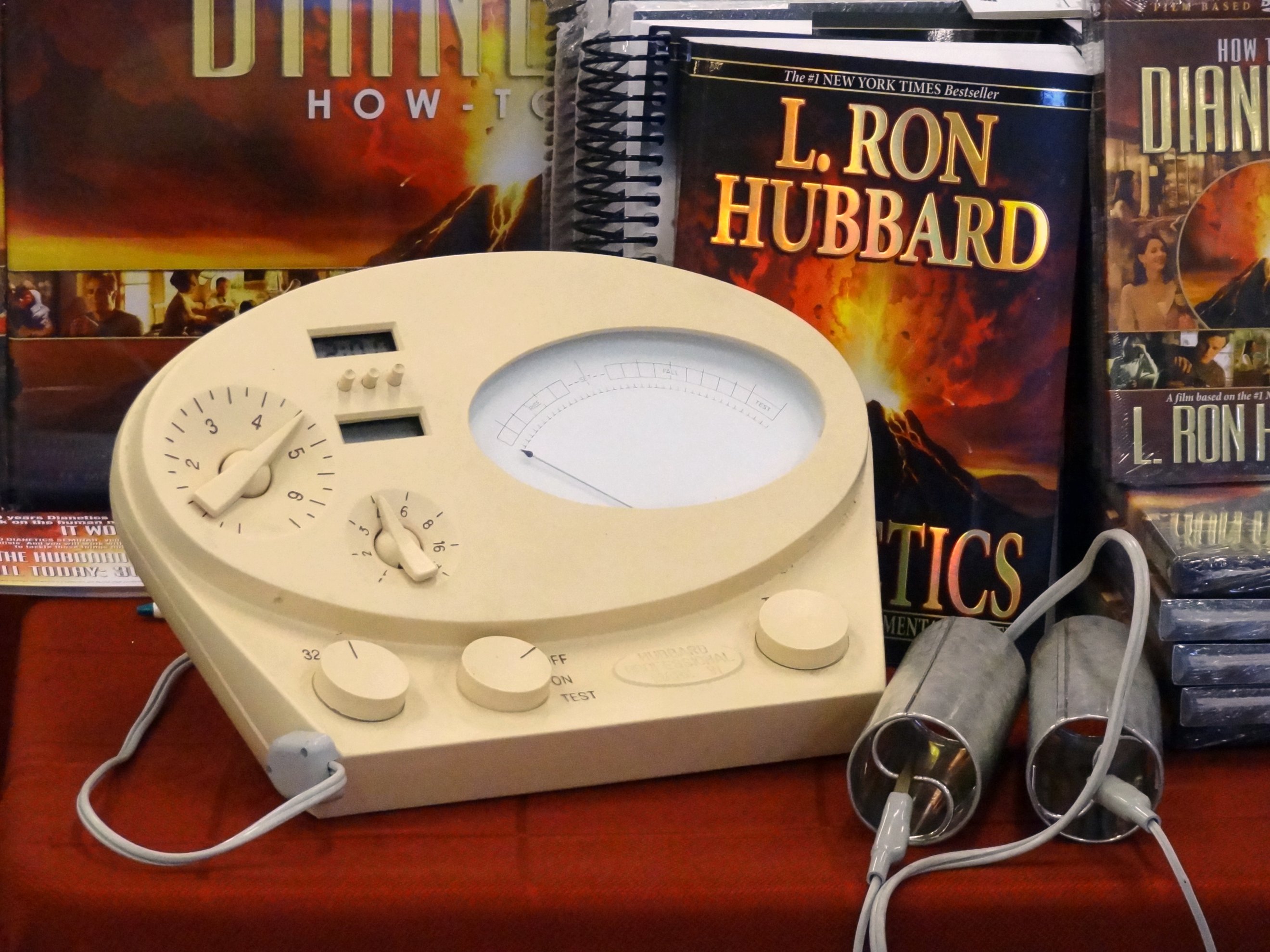

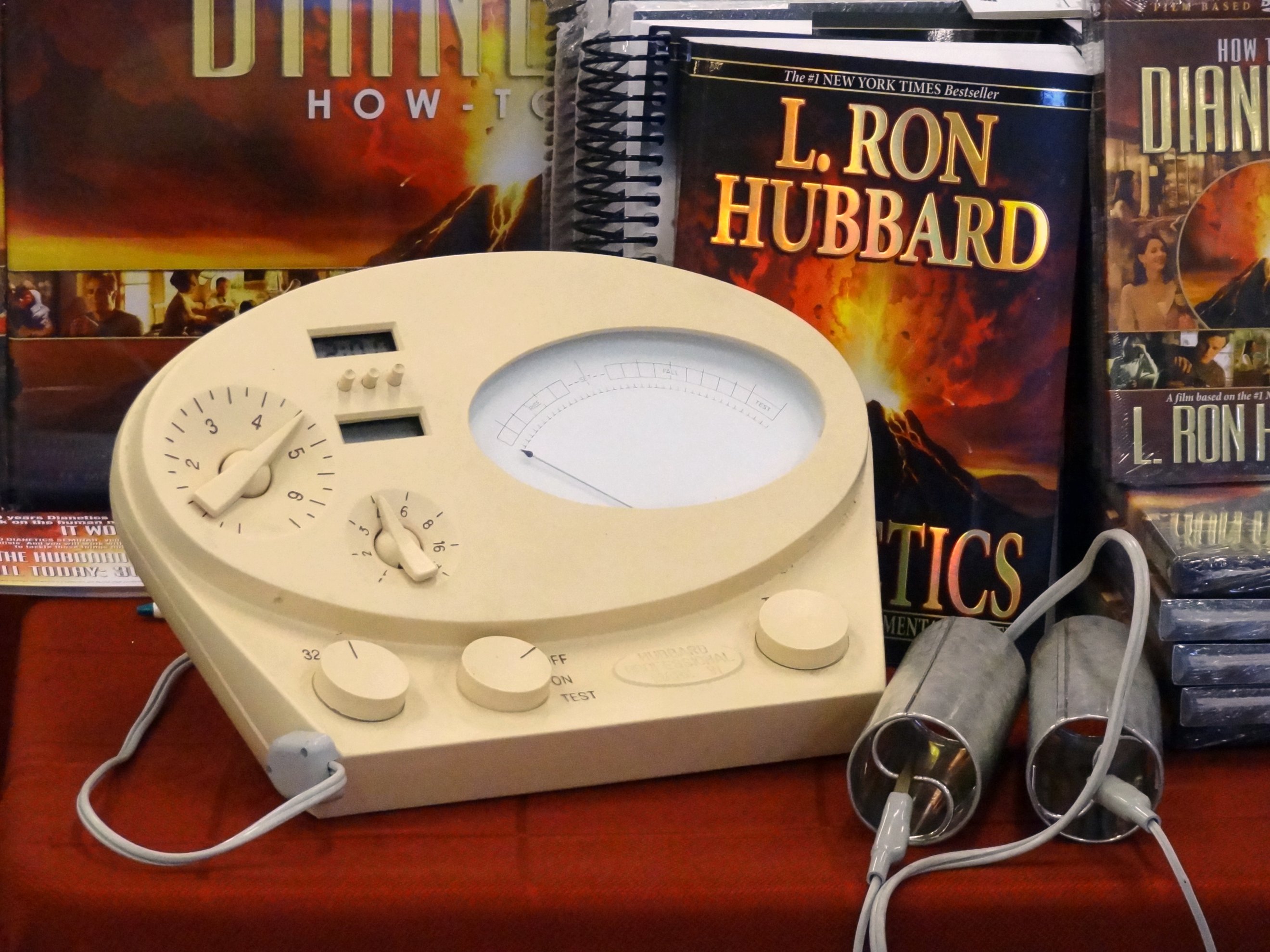

* L. Ron Hubbard (1911–1986), was the founder of the Church of Scientology

The Church of Scientology is a group of interconnected corporate entities and other organizations devoted to the practice, administration and dissemination of Scientology, which is variously defined as a cult, a business, or a new religiou ...

. He was an American science fiction

Science fiction (often shortened to sci-fi or abbreviated SF) is a genre of speculative fiction that deals with imaginative and futuristic concepts. These concepts may include information technology and robotics, biological manipulations, space ...

writer, former US Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

officer, and creator of Dianetics. He has been commonly called a quack and a con man by both critics of Scientology and by many psychiatric organizations in part for his often extreme anti-psychiatric beliefs and false claims about technologies such as the E-meter.

* Linda Hazzard (1867–1938), was a self-declared doctor and fasting specialist, which she advertised as a panacea for every medical ailment. Up to 40 patients may have died of starvation in her "sanitarium" in Olalla, Washington, US. Imprisoned for one death in 1912, Hazzard was paroled in 1915 and continued to practice medicine without a license in New Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

(1915–1920) and Washington, US (1920–1935). Died in 1938 while attempting a fasting to cure herself.

* William Donald Kelley (1925–2005), was an orthodontist and a follower of Max Gerson who developed his own alternative cancer treatment called Nonspecific Metabolic Therapy. This treatment is based on the unsubstantiated belief that "wrong foods ausemalignancy to grow, while proper foods llownatural body defenses to work". It involves, specifically, treatment with pancreatic enzymes, 50 daily vitamins and minerals (including laetrile), frequent body shampoos, coffee enemas, and a specific diet. According to Quackwatch, "not only is his therapy ineffective, but people with cancer who take it die more quickly and have a worse quality of life than those having standard treatment, and can develop serious or fatal side-effects. Kelley's most famous patient was actor Steve McQueen

Terrence Stephen McQueen (March 24, 1930November 7, 1980) was an American actor. His antihero persona, emphasized during the height of counterculture of the 1960s, 1960s counterculture, made him a top box office draw for his films of the late ...

.

* John Harvey Kellogg

John Harvey Kellogg (February 26, 1852 – December 14, 1943) was an American businessman, Invention, inventor, physician, and advocate of the Progressive Era, Progressive Movement. He was the director of the Battle Creek Sanitarium in Battle Cr ...

(1852–1943), was a medical doctor

A physician, medical practitioner (British English), medical doctor, or simply doctor is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through the study, diagnosis, prognosis ...

in Battle Creek, Michigan

Battle Creek is a city in northwestern Calhoun County, Michigan, United States, at the confluence of the Kalamazoo River, Kalamazoo and Battle Creek River, Battle Creek rivers. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the city had a tota ...

, US, who ran a sanitarium using holistic methods, with a particular focus on nutrition

Nutrition is the biochemistry, biochemical and physiology, physiological process by which an organism uses food and water to support its life. The intake of these substances provides organisms with nutrients (divided into Macronutrient, macro- ...

, enema

An enema, also known as a clyster, is the rectal administration of a fluid by injection into the Large intestine, lower bowel via the anus.Cullingworth, ''A Manual of Nursing, Medical and Surgical'':155 The word ''enema'' can also refer to the ...

s and exercise

Exercise or workout is physical activity that enhances or maintains fitness and overall health. It is performed for various reasons, including weight loss or maintenance, to aid growth and improve strength, develop muscles and the cardio ...

. Kellogg was an advocate of vegetarianism

Vegetarianism is the practice of abstaining from the Eating, consumption of meat (red meat, poultry, seafood, insects as food, insects, and the flesh of any other animal). It may also include abstaining from eating all by-products of animal slau ...

and invented the corn flake breakfast cereal

Breakfast cereal is a category of food, including food products, made from food processing, processed cereal, cereal grains, that are eaten as part of breakfast or as a snack food, primarily in Western societies.

Although warm, cooked cereals li ...

with his brother, Will Keith Kellogg

Will Keith Kellogg (born William Keith Kellogg; April 7, 1860 – October 6, 1951) was an American industrialist in food manufacturing, who founded the Kellogg Company, which produces a wide variety of popular breakfast cereals. He was a membe ...

.

* John St. John Long (1798–1834) was an Irish artist who claimed to be able to cure tuberculosis by causing a sore or wound on the back of the patient, out of which the disease would exit. He was tried twice for manslaughter of his patients who died under this treatment.

* Franz Anton Mesmer (1734–1815), was a German physician and astrologist, who invented what he called '' magnétisme animal''.

* Theodor Morell

Theodor "Theo" Karl Ludwig Gilbert Morell (22 July 1886 – 26 May 1948) was a German medical doctor known for acting as Adolf Hitler's personal physician. Morell was well known in Germany for his unconventional treatments. He assisted Hitler da ...

(1886–1948), a German physician best known as Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

's personal doctor. Morell administered approximately 74 substances, in 28 different mixtures to Hitler, including heroin

Heroin, also known as diacetylmorphine and diamorphine among other names, is a morphinan opioid substance synthesized from the Opium, dried latex of the Papaver somniferum, opium poppy; it is mainly used as a recreational drug for its eupho ...

, cocaine

Cocaine is a tropane alkaloid and central nervous system stimulant, derived primarily from the leaves of two South American coca plants, ''Erythroxylum coca'' and ''Erythroxylum novogranatense, E. novogranatense'', which are cultivated a ...

, Doktor Koster's Antigaspills, potassium bromide

Potassium bromide ( K Br) is a salt, widely used as an anticonvulsant and a sedative in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with over-the-counter use extending to 1975 in the US. Its action is due to the bromide ion ( sodium bromide is equa ...

, papaverine

Papaverine (Latin '' papaver'', "poppy") is an opium alkaloid antispasmodic drug, used primarily in the treatment of visceral spasms and vasospasms (especially those involving the intestines, heart, or brain), occasionally in the treatment of ...

, testosterone

Testosterone is the primary male sex hormone and androgen in Male, males. In humans, testosterone plays a key role in the development of Male reproductive system, male reproductive tissues such as testicles and prostate, as well as promoting se ...

, vitamins and animal enzymes. directed and produced by Chris Durlacher. A Waddell Media Production for Channel 4 in association with National Geographic Channels, MMXIV. Executive Producer Jon-Barrie Waddell. Despite Hitler's dependence on Morell, and his recommendations of him to other Nazi leaders, Hermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring (or Goering; ; 12 January 1893 – 15 October 1946) was a German Nazism, Nazi politician, aviator, military leader, and convicted war criminal. He was one of the most powerful figures in the Nazi Party, which gov ...

, Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler (; 7 October 1900 – 23 May 1945) was a German Nazism, Nazi politician and military leader who was the 4th of the (Protection Squadron; SS), a leading member of the Nazi Party, and one of the most powerful p ...

, Albert Speer

Berthold Konrad Hermann Albert Speer (; ; 19 March 1905 – 1 September 1981) was a German architect who served as Reich Ministry of Armaments and War Production, Minister of Armaments and War Production in Nazi Germany during most of W ...

and others quietly dismissed Morell as a quack.

* Daniel David Palmer (1845–1913), was a grocery store

A grocery store ( AE), grocery shop or grocer's shop ( BE) or simply grocery is a retail store that primarily retails a general range of food products, which may be fresh or packaged. In everyday US usage, however, "grocery store" is a synon ...

owner that claimed to have healed a janitor of deafness after adjusting the alignment of his back. He founded the field of chiropractic

Chiropractic () is a form of alternative medicine concerned with the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of mechanical disorders of the musculoskeletal system, especially of the spine. It is based on several pseudoscientific ideas.

Many c ...

based on the principle that all disease

A disease is a particular abnormal condition that adversely affects the structure or function (biology), function of all or part of an organism and is not immediately due to any external injury. Diseases are often known to be medical condi ...

and ailments could be fixed by adjusting the alignment of someone's back. His hypothesis was disregarded by medical professionals at the time and despite a considerable following has yet to be scientifically proven. Palmer established a magnetic healing facility in Davenport, Iowa, styling himself 'doctor'. Not everyone was convinced, as a local paper in 1894 wrote about him: "A crank on magnetism has a crazy notion that he can cure the sick and crippled with his magnetic hands. His victims are the weak-minded, ignorant and superstitious, those foolish people who have been sick for years and have become tired of the regular physician and want health by the short-cut method … he has certainly profited by the ignorance of his victims … His increase in business shows what can be done in Davenport, even by a quack."

* Louis Pasteur

Louis Pasteur (, ; 27 December 1822 – 28 September 1895) was a French chemist, pharmacist, and microbiologist renowned for his discoveries of the principles of vaccination, Fermentation, microbial fermentation, and pasteurization, the la ...

(1822–1895), was a French chemist

A chemist (from Greek ''chēm(ía)'' alchemy; replacing ''chymist'' from Medieval Latin ''alchemist'') is a graduated scientist trained in the study of chemistry, or an officially enrolled student in the field. Chemists study the composition of ...

best known for his remarkable breakthroughs in microbiology

Microbiology () is the branches of science, scientific study of microorganisms, those being of unicellular organism, unicellular (single-celled), multicellular organism, multicellular (consisting of complex cells), or non-cellular life, acellula ...

. His experiments confirmed the germ theory of disease

The germ theory of disease is the currently accepted scientific theory for many diseases. It states that microorganisms known as pathogens or "germs" can cause disease. These small organisms, which are too small to be seen without magnification, ...

, also reducing mortality from puerperal fever

The postpartum (or postnatal) period begins after childbirth and is typically considered to last for six to eight weeks. There are three distinct phases of the postnatal period; the acute phase, lasting for six to twelve hours after birth; the ...

(childbed), and he created the first vaccine

A vaccine is a biological Dosage form, preparation that provides active acquired immunity to a particular infectious disease, infectious or cancer, malignant disease. The safety and effectiveness of vaccines has been widely studied and verifi ...

for rabies

Rabies is a viral disease that causes encephalitis in humans and other mammals. It was historically referred to as hydrophobia ("fear of water") because its victims panic when offered liquids to drink. Early symptoms can include fever and abn ...

. He is best known to the general public for showing how to stop milk and wine from going sourthis process came to be called ''pasteurization

In food processing, pasteurization (American and British English spelling differences#-ise, -ize (-isation, -ization), also pasteurisation) is a process of food preservation in which packaged foods (e.g., milk and fruit juices) are treated wi ...

''. His hypotheses initially met with much hostility, and he was accused of quackery on multiple occasions. However, he is now regarded as one of the three main founders of microbiology

Microbiology () is the branches of science, scientific study of microorganisms, those being of unicellular organism, unicellular (single-celled), multicellular organism, multicellular (consisting of complex cells), or non-cellular life, acellula ...

, together with Ferdinand Cohn

Ferdinand Julius Cohn (24 January 1828 – 25 June 1898) was a German biologist. He is one of the founders of modern bacteriology and microbiology.

Biography

Ferdinand Julius Cohn was born in the Jewish quarter of Breslau in the Prussian Pro ...

and Robert Koch

Heinrich Hermann Robert Koch ( ; ; 11 December 1843 – 27 May 1910) was a German physician and microbiologist. As the discoverer of the specific causative agents of deadly infectious diseases including tuberculosis, cholera and anthrax, he i ...

.

* Linus Pauling

Linus Carl Pauling ( ; February 28, 1901August 19, 1994) was an American chemist and peace activist. He published more than 1,200 papers and books, of which about 850 dealt with scientific topics. ''New Scientist'' called him one of the 20 gre ...

(1901–1994), a Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; ; ) are awards administered by the Nobel Foundation and granted in accordance with the principle of "for the greatest benefit to humankind". The prizes were first awarded in 1901, marking the fifth anniversary of Alfred N ...

winner in chemistry

Chemistry is the scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a physical science within the natural sciences that studies the chemical elements that make up matter and chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules a ...

, Pauling spent much of his later career arguing for the treatment of somatic and psychological diseases with orthomolecular medicine

Orthomolecular medicine is a form of alternative medicine that claims to maintain human health through nutritional Dietary supplement, supplementation. It is rejected by evidence-based medicine. The concept builds on the idea of an optimal nutrit ...

. Among his claims were that the common cold

The common cold, or the cold, is a virus, viral infectious disease of the upper respiratory tract that primarily affects the Respiratory epithelium, respiratory mucosa of the human nose, nose, throat, Paranasal sinuses, sinuses, and larynx. ...

could be cured with massive doses of vitamin C

Vitamin C (also known as ascorbic acid and ascorbate) is a water-soluble vitamin found in citrus and other fruits, berries and vegetables. It is also a generic prescription medication and in some countries is sold as a non-prescription di ...

. Together with Ewan Cameron he wrote the 1979 book ''Cancer and Vitamin C'', which was again more popular with the public than the medical profession, which continued to regard claims about the effectiveness of vitamin C in treating or preventing cancer as quackery. A biographer has discussed how controversial his views on megadoses of Vitamin C have been and that he was "still being called a 'fraud' and a 'quack' by opponents of his 'orthomolecular medicine.Thomas BlairLinus Pauling: Nobel Laureate for Peace and Chemistry 1901–1994

* Doctor John Henry Pinkard (1866–1934) was a

Roanoke, Virginia

Roanoke ( ) is an Independent city (United States), independent city in Virginia, United States. It lies in Southwest Virginia, along the Roanoke River, in the Blue Ridge Mountains, Blue Ridge range of the greater Appalachian Mountains. Roanok ...

businessman and "Yarb Doctor" or "Herb Doctor" who concocted quack medicines that he sold and distributed in violation of the Food and Drugs Act

The ''Food and Drugs Act'' () is an act of the Parliament of Canada regarding the production, import, export, transport across provinces and sale of food, drugs, contraceptive devices and cosmetics (including personal cleaning products such as ...

and the earlier Pure Food and Drug Act

The s:Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, also known as the Wiley Act and Harvey Washington Wiley, Dr. Wiley's Law, was the first of a series of significant consumer protection laws enacted by the United States Con ...

. He was also known as a "clairvoyant, herb doctor and spiritualist." Some of Pinkard's Sanguinaria Compound, made from bloodroot or bloodwort, was seized by federal officials in 1931. "Analysis by this department of a sample of the article showed that it consisted essentially of extracts of plant drugs including sanguinaria, sugar, alcohol, and water. It was alleged in the information that the article was misbranded in that certain statements, designs, and devices regarding the therapeutic and curative effects of the article, appearing on the bottle label, falsely and fraudulently represented that it would be effective as a treatment, remedy, and cure for pneumonia, coughs, weak lungs, asthma, kidney, liver, bladder, or any stomach troubles, and effective as a great blood and nerve tonic." He pleaded guilty and was fined.

* Wilhelm Reich

Wilhelm Reich ( ; ; 24 March 1897 – 3 November 1957) was an Austrian Doctor of Medicine, doctor of medicine and a psychoanalysis, psychoanalyst, a member of the second generation of analysts after Sigmund Freud. The author of several in ...

(1897–1957), Austrian-American Psychoanalyst. Claimed that he had discovered a primordial cosmic energy called Orgone

Orgone ( ) is a pseudoscientific concept variously described as an esoteric energy or hypothetical universal life force. Originally proposed in the 1930s by Wilhelm Reich, and developed by Reich's student Charles Kelley after Reich's death ...

. He developed several devices, including the Cloudbuster and the Orgone Accumulator, that he believed could use orgone to manipulate the weather, battle space aliens and cure diseases, including cancer. After an investigation, the US Food and Drug Administration

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA or US FDA) is a federal agency of the Department of Health and Human Services. The FDA is responsible for protecting and promoting public health through the control and supervision of food ...

concluded that they were dealing with a "fraud of the first magnitude". On 10 February 1954, the US Attorney for Maine filed a complaint seeking a permanent injunction under Sections 301 and 302 of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act

The United States Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (abbreviated as FFDCA, FDCA, or FD&C) is a set of laws passed by the United States Congress in 1938 giving authority to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to oversee the food safety ...

, to prevent interstate shipment of orgone accumulators and to ban some of Reich's writing promoting and advertising the devices. Reich refused to appear in court, arguing that no court was in a position to evaluate his work. Reich was arrested for contempt of court

Contempt of court, often referred to simply as "contempt", is the crime of being disobedient to or disrespectful toward a court of law and its officers in the form of behavior that opposes or defies the authority, justice, and dignity of the co ...

, and convicted to two years in jail, a US$

The United States dollar (Currency symbol, symbol: Dollar sign, $; ISO 4217, currency code: USD) is the official currency of the United States and International use of the U.S. dollar, several other countries. The Coinage Act of 1792 introdu ...

10,000 fine, and his Orgone Accumulators and work on Orgone were ordered to be destroyed. On 23 August 1956, six tons of his books, journals, and papers were burned in the 25th Street public incinerator in New York. On 12 March 1957, he was sent to Danbury Federal Prison, where Richard C. Hubbard, a psychiatrist who admired Reich, examined him, recording paranoia

Paranoia is an instinct or thought process that is believed to be heavily influenced by anxiety, suspicion, or fear, often to the point of delusion and irrationality. Paranoid thinking typically includes persecutory beliefs, or beliefs of co ...

manifested by delusions of grandiosity, persecution, and ideas of reference. Nine months later, on 18 November 1957, Reich died of a heart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when Ischemia, blood flow decreases or stops in one of the coronary arteries of the heart, causing infarction (tissue death) to the heart muscle. The most common symptom ...

while he was in the federal penitentiary in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania

Lewisburg is a borough in Union County, Pennsylvania, United States, south by southeast of Williamsport, Pennsylvania, Williamsport and north of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, Harrisburg. The population was 5,158 as of the United States Census 202 ...

.

* William Herbert Sheldon

William Herbert Sheldon, Jr. (November 19, 1898 – September 17, 1977) was an American psychologist, numismatist, and eugenicist. He created the field of somatotype and constitutional psychology that correlate body types with temperament, illus ...

(1898–1977), who created the theory of somatotypes corresponding to intelligence.

Information Age quackery

As technology has evolved, particularly with the advent and wide adoption of the internet, it has increasingly become a source of quackery. For example, writing in ''The New York Times Magazine

''The New York Times Magazine'' is an American Sunday magazine included with the Sunday edition of ''The New York Times''. It features articles longer than those typically in the newspaper and has attracted many notable contributors. The magazi ...

'', Virginia Heffernan criticized WebMD for biasing readers toward drugs that are sold by the site's pharmaceutical sponsors, even when they are unnecessary. She wrote that WebMD "has become permeated with pseudomedicine and subtle misinformation."

See also

* Association for Science in Autism Treatment *Confidence trick

A scam, or a confidence trick, is an attempt to defraud a person or group after first gaining their trust. Confidence tricks exploit victims using a combination of the victim's credulity, naivety, compassion, vanity, confidence, irrespons ...

* Crystal healing

Crystal healing is a pseudoscientific alternative-medicine practice that uses semiprecious stones and crystals such as quartz, agate, amethyst or opal. Despite the common use of the term "crystal", many popular stones used in crystal healin ...

* Detoxification foot baths

* Health care fraud