Pushmataha County, Oklahoma on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Pushmataha County is a

France's Bernard de la Harpe explored the area of the modern Pushmataha County in 1719, in the era when France was establishing settlements on the Gulf Coast. They had founded

France's Bernard de la Harpe explored the area of the modern Pushmataha County in 1719, in the era when France was establishing settlements on the Gulf Coast. They had founded

Although no battles were recorded as occurring within the present-day confines of Pushmataha County, the Battle of Perryville occurred just outside modern-day McAlester and the Battle of Middle Boggy Depot took place outside present-day Atoka. Numerous Choctaws left their homes in the present-day county to join the battalions and participated in the

Although no battles were recorded as occurring within the present-day confines of Pushmataha County, the Battle of Perryville occurred just outside modern-day McAlester and the Battle of Middle Boggy Depot took place outside present-day Atoka. Numerous Choctaws left their homes in the present-day county to join the battalions and participated in the

The railroad stimulated development of businesses and other ties to mainstream United States society. The

The railroad stimulated development of businesses and other ties to mainstream United States society. The

Pushmataha County at statehood was considered an agricultural paradise. Local residents believed the soil to be fertile and the weather enviable and moderate; it seemed that almost any fruit or vegetable could be grown. Most residents at the time were farmers who lived off their land.

Cotton was king for the county's first few decades. It was grown throughout the Kiamichi River valley. Growers hauled it into Antlers, Clayton,

Pushmataha County at statehood was considered an agricultural paradise. Local residents believed the soil to be fertile and the weather enviable and moderate; it seemed that almost any fruit or vegetable could be grown. Most residents at the time were farmers who lived off their land.

Cotton was king for the county's first few decades. It was grown throughout the Kiamichi River valley. Growers hauled it into Antlers, Clayton,  Federal government programs developed by the administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt during the

Federal government programs developed by the administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt during the

The

The  Interesting geographical features in the county include Rock Town, a small region of distinctive boulders in Johns Valley; Umbrella Rock near Clayton; McKinley Rocks near Tuskahoma; and the Potato Hills—unusually serrated landforms near Tuskahoma.

Interesting geographical features in the county include Rock Town, a small region of distinctive boulders in Johns Valley; Umbrella Rock near Clayton; McKinley Rocks near Tuskahoma; and the Potato Hills—unusually serrated landforms near Tuskahoma.

Oklahoma State Highway 144

*

Oklahoma State Highway 144

*  U.S. Highway 271

U.S. Highway 271

As of the census of 2010, there were 11,572 people, 4,809 households, and 3,247 families residing in the county. The population density was . There were 6,110 housing units at an average density of . The racial makeup of the county was 75%

As of the census of 2010, there were 11,572 people, 4,809 households, and 3,247 families residing in the county. The population density was . There were 6,110 housing units at an average density of . The racial makeup of the county was 75%

Timber is an economic mainstay. Lumber companies own large swaths of the county and operate vast tree plantations. Fast-growing

Timber is an economic mainstay. Lumber companies own large swaths of the county and operate vast tree plantations. Fast-growing

county

A county () is a geographic region of a country used for administrative or other purposesL. Brookes (ed.) '' Chambers Dictionary''. Edinburgh: Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd, 2005. in some nations. The term is derived from the Old French denoti ...

in the southeastern part of the U.S. state of Oklahoma

Oklahoma ( ; Choctaw language, Choctaw: , ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Texas to the south and west, Kansas to the north, Missouri to the northea ...

. As of the 2020 census, the population was 10,812. Its county seat

A county seat is an administrative center, seat of government, or capital city of a county or parish (administrative division), civil parish. The term is in use in five countries: Canada, China, Hungary, Romania, and the United States. An equiva ...

is Antlers.

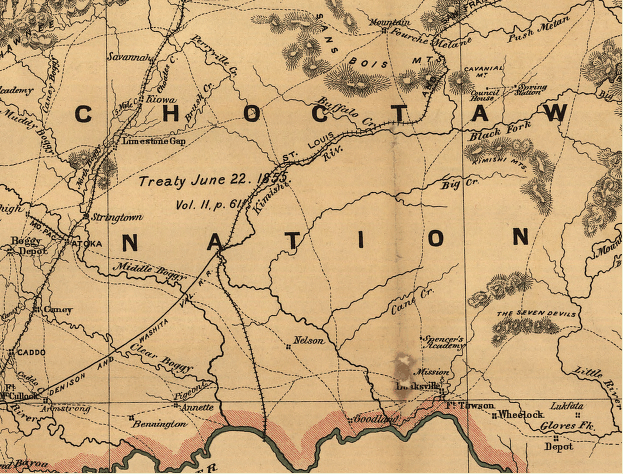

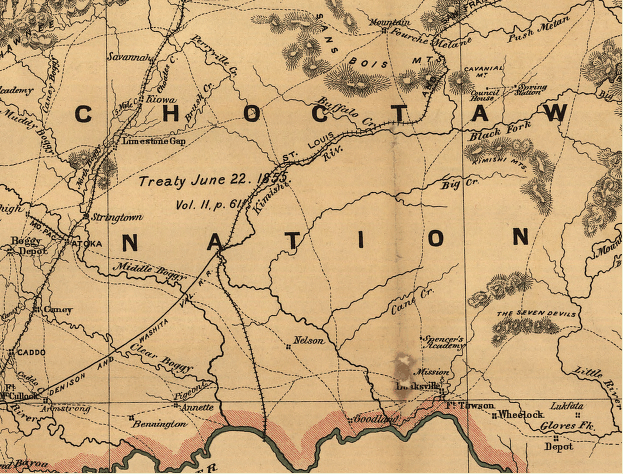

The county was created at statehood from part of the former territory of the Choctaw Nation

The Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma (Choctaw: ''Chahta Okla'') is a Native American reservation occupying portions of southeastern Oklahoma in the United States. At roughly , it is the second-largest reservation in area after the Navajo, exceeding t ...

, which had its capital at the town of Tuskahoma. Planned by the Five Civilized Tribes as part of a state of Sequoyah, the new Oklahoma state also named the county for Pushmataha, an important Choctaw chief in the American Southeast. He had tried to ensure that his people would not have to cede their lands, but died in Washington, DC during a diplomatic trip in 1824. The Choctaw suffered Indian Removal to Indian Territory

Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the Federal government of the United States, United States government for the relocation of Native Americans in the United States, ...

.

History

Administrative history

* Ca. 1000–1500: Caddoan Mississippian culture at Spiro Mounds * 1492–1718: Spain * 1718–1763: France * 1763–1800: Spain * 1800–1803: France * 1803–present: United States (after Louisiana Purchase) :* 1824–1825: Miller County, Arkansas Territory (eastern portion of the county) :* 1825–1907: Choctaw Nation of Indian Territory :* 1907–present: State of OklahomaPrehistory and exploration

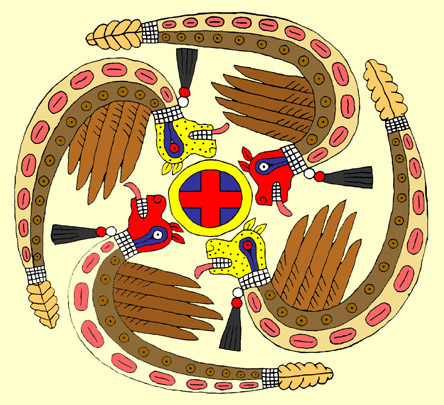

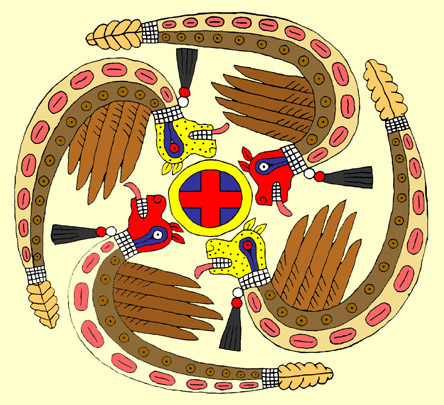

During prehistoric times, Pushmataha County was part of the territory during theMiddle Woodland period

In the classification of :category:Archaeological cultures of North America, archaeological cultures of North America, the Woodland period of North American pre-Columbian cultures spanned a period from roughly 1000 BC to European contact i ...

of the Fourche Maline culture. Over time, and possibly through contact with the Middle Mississippian culture

The Mississippian culture was a collection of Native American societies that flourished in what is now the Midwestern, Eastern, and Southeastern United States from approximately 800 to 1600 CE, varying regionally. It was known for building la ...

to their northeast, the Fourche Maline became the Caddoan Mississippian culture. Their center was at Spiro Mounds

Spiro Mounds (Smithsonian trinomial, 34 LF 40) is an Indigenous archaeological site located in present-day eastern Oklahoma. The site was built by people from the Arkansas Valley Caddoan culture. that remains from an Native Americans in the Uni ...

, near Spiro, Oklahoma

Spiro is a town in Le Flore County, Oklahoma, Le Flore County, Oklahoma, United States. It is part of the Fort Smith, Arkansas-Oklahoma Fort Smith metropolitan area, Metropolitan Statistical Area. The population was 2,164 at the 2010 census, a 2.8 ...

. The elite organized the construction of complex earthwork mounds for burial and ritual ceremonial purposes, arranged around a large plaza that had been carefully graded. This center of political and religious leadership had a trade territory encompassing the full extent of the Kiamichi River and Little River valleys. This 80-acre site is preserved as Oklahoma's only Archeological State Park. The larger Mississippian culture traded from the Great Lakes to the Gulf Coast.

North America's history changed after the arrival of Europeans in 1492 under Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus (; between 25 August and 31 October 1451 – 20 May 1506) was an Italians, Italian explorer and navigator from the Republic of Genoa who completed Voyages of Christopher Columbus, four Spanish-based voyages across the At ...

in the Caribbean. In the 16th century, European explorers began to enter the North American interior, seeking fame, treasures, and conquests on behalf of their empires.

France's Bernard de la Harpe explored the area of the modern Pushmataha County in 1719, in the era when France was establishing settlements on the Gulf Coast. They had founded

France's Bernard de la Harpe explored the area of the modern Pushmataha County in 1719, in the era when France was establishing settlements on the Gulf Coast. They had founded New Orleans

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

the year before. De la Harpe's exploration of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the main stem, primary river of the largest drainage basin in the United States. It is the second-longest river in the United States, behind only the Missouri River, Missouri. From its traditional source of Lake Ita ...

valley was part of an effort to seek trade with the native peoples and also a route to New Mexico

New Mexico is a state in the Southwestern United States, Southwestern region of the United States. It is one of the Mountain States of the southern Rocky Mountains, sharing the Four Corners region with Utah, Colorado, and Arizona. It also ...

. After this time France claimed this region of North America as La Louisiane. It explored Canada to the north from the Atlantic coast along the St. Lawrence River

The St. Lawrence River (, ) is a large international river in the middle latitudes of North America connecting the Great Lakes to the North Atlantic Ocean. Its waters flow in a northeasterly direction from Lake Ontario to the Gulf of St. Lawren ...

valley, where it founded New France.

The area that became Pushmataha County was bought by the United States from France as part of the large Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase () was the acquisition of the Louisiana (New France), territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. This consisted of most of the land in the Mississippi River#Watershed, Mississipp ...

in 1803.

The first American explorer to set foot in the modern county was Major Stephen H. Long in 1817. He was followed in 1819 by Thomas Nuttall

Thomas Nuttall (5 January 1786 – 10 September 1859) was an English botanist and zoologist who lived and worked in America from 1808 until 1841.

Nuttall was born in the village of Long Preston, near Settle in the West Riding of Yorkshire a ...

, a scientist. Both explored the Kiamichi River valley, which Nuttall described in detail.

The Red River became an international boundary in 1819 when the United States concluded the Adams-Onis Treaty with the Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire, sometimes referred to as the Hispanic Monarchy (political entity), Hispanic Monarchy or the Catholic Monarchy, was a colonial empire that existed between 1492 and 1976. In conjunction with the Portuguese Empire, it ushered ...

. Fortifying the frontier

A frontier is a political and geographical term referring to areas near or beyond a boundary.

Australia

The term "frontier" was frequently used in colonial Australia in the meaning of country that borders the unknown or uncivilised, th ...

from Spanish incursion, and securing it against potential uprisings by American Indians, was important to United States policy. The federal government established a chain of forts

A fortification (also called a fort, fortress, fastness, or stronghold) is a military construction designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from ...

along its southern border.

Fort Towson

Fort Towson was a frontier outpost for Frontier Army Quartermasters along the Permanent Indian Frontier located about two miles (3 km) northeast of the present community of Fort Towson, Oklahoma. Located on Gates Creek near the confluen ...

, established at the mouth of Gates Creek on the Kiamichi River, just upstream from its confluence with the Red River, was charged with providing security for the region encompassing modern Pushmataha County. As the fort was built in what was considered frontier wilderness, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

The United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) is the military engineering branch of the United States Army. A direct reporting unit (DRU), it has three primary mission areas: Engineer Regiment, military construction, and civil wor ...

constructed a military road connecting Fort Towson with Fort Smith, Arkansas

Fort Smith is the List of municipalities in Arkansas, third-most populous city in Arkansas, United States, and one of the two county seats of Sebastian County, Arkansas, Sebastian County. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the pop ...

for purposes of supply and provision. Passing through the Little River valley, this military road was Pushmataha County's first modern roadway

A carriageway (British English) or roadway (North American English) is a width of road on which a vehicle is not restricted by any physical barriers or separation to move laterally. A carriageway generally consists of a number of traffic lane ...

. It lapsed into disuse after Fort Towson was abandoned after the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

. Traces of the road may still be seen.

The Indian Territory

Pushmataha County's modern origins lie in theChoctaw Nation

The Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma (Choctaw: ''Chahta Okla'') is a Native American reservation occupying portions of southeastern Oklahoma in the United States. At roughly , it is the second-largest reservation in area after the Navajo, exceeding t ...

, during its time as a sovereign nation in the Indian Territory

Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the Federal government of the United States, United States government for the relocation of Native Americans in the United States, ...

, prior to Oklahoma

Oklahoma ( ; Choctaw language, Choctaw: , ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Texas to the south and west, Kansas to the north, Missouri to the northea ...

statehood.

Political Organization

The Choctaw territory comprising the modern county was, until statehood in 1907, divided among two of the three administrative districts, or regions, comprising the nation – Pushmataha and Apukshunnubbee. Each of these districts was subdivided into counties. The modern county fell withinCedar County

Cedar County may refer to:

* Cedar County, Iowa

* Cedar County, Missouri

* Cedar County, Nebraska

* Cedar County, Choctaw Nation

* Cedar County, Washington, a proposed county made up of part of King County

* Cedar County, Utah Territory, a fo ...

, Nashoba County Nashoba County (Choctaw: ''Kanti Nashoba'') was a political subdivision of the Choctaw Nation of Indian Territory. The county formed part of the Nation’s Apukshunnubbee District, or Second District, one of three administrative super-regions in th ...

and Wade County of the Apukshunnubbee District Apukshunnubbee District was one of three provinces, or districts, comprising the former Choctaw Nation in Indian Territory. Also called the Second District, it encompassed the southeastern one-third of the nation.

The Apukshunnubbee District was ...

—today the county's eastern area – and Jack's Fork County {{More footnotes, date=July 2022

Jack's Fork County, also known as Jack Fork County, was a political subdivision of the Choctaw Nation of Indian Territory. The county formed part of the nation's Pushmataha District, or Third District, one of three ...

and Kiamitia County Kiamitia County, also known as Kiamichi County, was a political subdivision of the Choctaw Nation, Indian Territory. The county formed part of the nation's Pushmataha District, or Third District, one of three administrative super-regions.

Kiamiti ...

(Kiamichi County) of the Pushmataha District Pushmataha District was one of three provinces, or districts, comprising the former Choctaw Nation in the Indian Territory. Also called the Third District, it encompassed the southwestern one-third of the nation.

The Pushmataha District was named ...

– today the county's western area.

The American Civil War

During theAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

federal troops withdrew from the Indian Territory and the Choctaw Nation allied itself with the Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), also known as the Confederate States (C.S.), the Confederacy, or Dixieland, was an List of historical unrecognized states and dependencies, unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United State ...

. The Choctaw government sent a representative to the Confederate Congress

The Confederate States Congress was both the provisional and permanent legislative assembly/legislature of the Confederate States of America that existed from February 1861 to April/June 1865, during the American Civil War. Its actions were, ...

, meeting in the Confederate capital at Richmond, Virginia, and raised battalions of warriors to participate with Confederate troops.

Although no battles were recorded as occurring within the present-day confines of Pushmataha County, the Battle of Perryville occurred just outside modern-day McAlester and the Battle of Middle Boggy Depot took place outside present-day Atoka. Numerous Choctaws left their homes in the present-day county to join the battalions and participated in the

Although no battles were recorded as occurring within the present-day confines of Pushmataha County, the Battle of Perryville occurred just outside modern-day McAlester and the Battle of Middle Boggy Depot took place outside present-day Atoka. Numerous Choctaws left their homes in the present-day county to join the battalions and participated in the Battle of Pea Ridge

The Battle of Pea Ridge (March 7–8, 1862), also known as the Battle of Elkhorn Tavern, took place during the American Civil War near Leetown, Arkansas, Leetown, northeast of Fayetteville, Arkansas, Fayetteville, Arkansas. United States, Feder ...

, in Arkansas, and at the Battle of Honey Springs

The Battle of Honey Springs, also known as the Affair at Elk Creek, on July 17, 1863, was an American Civil War Engagement (military), engagement and an important victory for Union forces in their efforts to gain control of the Indian Territory ...

in the Cherokee Nation, which pitted them against a Unionist faction of Cherokee Indians.

Contemporary accounts make mention of many refugees streaming through the Kiamichi River valley. The war itself finally ended with the surrender of the last Confederate army—Cherokee General Stand Watie

Brigadier-General Stand Watie (; December 12, 1806September 9, 1871), also known as Standhope Uwatie and Isaac S. Watie, was a Cherokee politician who served as the second principal chief of the Cherokee Nation from 1862 to 1866. The Cherokee ...

's forces, who surrendered at Fort Towson

Fort Towson was a frontier outpost for Frontier Army Quartermasters along the Permanent Indian Frontier located about two miles (3 km) northeast of the present community of Fort Towson, Oklahoma. Located on Gates Creek near the confluen ...

in June 1865, over two months after General Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a general officers in the Confederate States Army, Confederate general during the American Civil War, who was appointed the General in Chief of the Armies of the Confederate ...

surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was a field army of the Confederate States Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was also the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most often arrayed agains ...

—and with it any chance of Confederate success.

Sometime before 1862 a Negro slave, Wallace Willis

Wallace Willis was a Choctaw Freedman living in the Indian Territory, in what is now Choctaw County, near the city of Hugo, Oklahoma, US. His dates are unclear: perhaps 1820 to 1880. He is credited with composing (probably before 1860) several ...

, composed the Negro spiritual "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot

"Swing Low, Sweet Chariot" is an African-American spiritual song and one of the best-known Christian hymns. Originating in early African-American musical traditions, the song was probably composed in the late 1860s by Wallace Willis and his d ...

". He was then working at Spencer Academy, a Choctaw Nation boarding school located at Spencervile, Indian Territory. The site of the academy and old Spencerville was located less than 1,000 yards from the current southern border of Pushmataha County. Known as Uncle Wallace, Willis may have resided in Pushmataha County. He died in present-day Atoka County

Atoka County is a county located in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. As of the 2020 census, the population was 14,143. Its county seat is Atoka. The county was formed before statehood from Choctaw Lands, and its name honors a Choctaw Chief named ...

and is buried in an unmarked grave.

Railroads arrive

The Choctaw people were sedentary. Their lives were tied to their farms and small acreages. The Choctaw Nation was not home to industry of any sort. As a result, the territory comprising modern-day Pushmataha County was still virgin wilderness decades after the Choctaws’ arrival. During the 1880s the St. Louis and San Francisco Railroad – popularly known as the Frisco—built a line fromFort Smith, Arkansas

Fort Smith is the List of municipalities in Arkansas, third-most populous city in Arkansas, United States, and one of the two county seats of Sebastian County, Arkansas, Sebastian County. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the pop ...

to Paris, Texas. The federal government granted the railroad rights-of-way in Indian Territory to stimulate development and attract European-American settlers. Station stops were established every few miles, both to aid in developing towns and also to serve the railroad.

The Frisco's route traveled along the Kiamichi River valley, entering the present-day county near Albion

Albion is an alternative name for Great Britain. The oldest attestation of the toponym comes from the Greek language. It is sometimes used poetically and generally to refer to the island, but is less common than "Britain" today. The name for Scot ...

and leaving the river only at Antlers, to skirt the massive bluff where it is located.

The railroad stimulated development of businesses and other ties to mainstream United States society. The

The railroad stimulated development of businesses and other ties to mainstream United States society. The telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas ...

was developed and constructed along with the railroad, providing rapid news of events outside the Choctaw Nation.

Logging companies opened operations immediately. Rough-and-tumble sawmill communities began growing up around the railroad station stops. Kosoma, a veritable boomtown, boasted several hotels, doctors’ offices, and general stores during its heyday.

During the next few decades, loggers harvested the entire region, using the railroad stations as transshipment points. These transshipment points developed into the present-day communities of Albion, Moyers, and Antlers. Other communities along the railroad between these points later vanished or are today only place names, such as Kellond, Stanley

Stanley may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Film and television

* ''Stanley'' (1972 film), an American horror film

* ''Stanley'' (1984 film), an Australian comedy

* ''Stanley'' (1999 film), an animated short

* ''Stanley'' (1956 TV series) ...

and Kiamichi.

For decades the Frisco constituted the greatest feat of engineering and manmade structure in Pushmataha County. Workers moved and shaped huge amounts of earth to form its elevated roadbed, and constructed numerous wooden trestles over creeks and rivers. Once in place the railroad attracted commerce and industry, where white men in the Indian Territory hoped to stake a claim.

Bid for self-determination

Although theFive Civilized Tribes

The term Five Civilized Tribes was applied by the United States government in the early federal period of the history of the United States to the five major Native American nations in the Southeast: the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee (Cr ...

of the Indian Territory opposed being incorporated within a United States state, by the turn of the 20th century, statehood of some sort appeared inevitable. A group of leaders from the Five Civilized Nations – Choctaw, Cherokee, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole – met at Muskogee in an attempt to seize the initiative and fashion a state from the Indian Territory, a jurisdiction to be controlled by Native Americans. Their meeting, which came to be known as the Sequoyah Constitutional Convention

The Sequoyah Constitutional Convention was an American Indian-led attempt to secure statehood for Indian Territory as an Indian-controlled jurisdiction, separate from the Oklahoma Territory. The proposed state was to be called the State of Sequo ...

, established the proposed State of Sequoyah

The State of Sequoyah was a proposed U.S. state, state to be established from the Indian Territory in Eastern Oklahoma, eastern present-day Oklahoma. In 1905, with the end of tribal governments looming, Five Civilized Tribes, Native Americans (th ...

.

The leaders meeting in Muskogee recognized that the counties of the Choctaw Nation, drawn to reflect easily recognizable natural landmarks such as mountain ranges and rivers, were not economically viable. Jack's Fork County, as example – in which Antlers was located – was a vast territory whose tiny county seat was Many Springs (modern-day Daisy, Oklahoma

Daisy is a small unincorporated community in Atoka County, Oklahoma

Oklahoma ( ; Choctaw language, Choctaw: , ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders T ...

). But the only commercially successful town within its boundaries was Antlers, and it was situated in its far southeastern corner.

County boundaries for the new State of Sequoyah were crafted to take into account the existing towns and the range of their commercial interests. County seats were centered geographically within the populations of the areas they would govern.

The area comprising modern-day Pushmataha County proved a particular challenge. Huge areas of its eastern portion had few people. Its population was centered in towns along the railroad in the Kiamichi River valley. A county was eventually drawn with the crescent of the Kiamichi River valley forming its commercial heart, and it was to be called Pushmataha County, Sequoyah

{{distinguish, Pushmataha County, Oklahoma

Pushmataha County was a proposed political subdivision created by the Sequoyah Constitutional Convention. The convention, meeting in Muskogee, Indian Territory in 1905, established the political and admin ...

.

Records of the Sequoyah Constitutional Convention's committee on counties are lost, and no evidence remains to document the committee's deliberations. They wanted an area named after their Chief Pushmataha, and singled out the future Pushmataha County, Sequoyah for this honor.

Hugo's businesses served an area extending as far north as Kent

Kent is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Essex across the Thames Estuary to the north, the Strait of Dover to the south-east, East Sussex to the south-west, Surrey to the west, and Gr ...

, Speer, Hamden Hamden is the name of several places in the United States of America. It also is a surname.

Places

*Hamden, Connecticut

*Hamden Township, Becker County, Minnesota

*Hamden, Missouri

*Hamden, New York

*Hamden, Ohio

*Hamden, Oklahoma

Name

*Erika Ham ...

, and nearly to Rattan

Rattan, also spelled ratan (from Malay language, Malay: ''rotan''), is the name for roughly 600 species of Old World climbing palms belonging to subfamily Calamoideae. The greatest diversity of rattan palm species and genera are in the clos ...

. As a result, the county boundary for the proposed Hitchcock County – with Hugo as county seat – was established along the line of the existing boundary between Choctaw and Pushmataha counties. Similar considerations governed the establishment of the county's northern, eastern and western borders.

The United States Congress failed to admit the proposed State of Sequoyah into the Union, preferring to await a possible federation of the Indian Territory and Territory of Oklahoma. This was soon proposed. In 1907 the Oklahoma Constitutional Convention met in Guthrie, Oklahoma Territory to create the new State of Oklahoma. During these deliberations it became clear that the work of the Sequoyah Constitutional Convention had been groundbreaking: the Guthrie meeting essentially adopted nearly the same boundaries for Pushmataha County, Oklahoma as were proposed earlier for it in the state of Sequoyah, again identifying Antlers as county seat.

Since statehood

Pushmataha County at statehood was considered an agricultural paradise. Local residents believed the soil to be fertile and the weather enviable and moderate; it seemed that almost any fruit or vegetable could be grown. Most residents at the time were farmers who lived off their land.

Cotton was king for the county's first few decades. It was grown throughout the Kiamichi River valley. Growers hauled it into Antlers, Clayton,

Pushmataha County at statehood was considered an agricultural paradise. Local residents believed the soil to be fertile and the weather enviable and moderate; it seemed that almost any fruit or vegetable could be grown. Most residents at the time were farmers who lived off their land.

Cotton was king for the county's first few decades. It was grown throughout the Kiamichi River valley. Growers hauled it into Antlers, Clayton, Albion

Albion is an alternative name for Great Britain. The oldest attestation of the toponym comes from the Greek language. It is sometimes used poetically and generally to refer to the island, but is less common than "Britain" today. The name for Scot ...

, and other railroad towns to be weighed and shipped to distant markets on the Frisco Railroad.

Many of the farmers or hired hands were African Americans, descendants of slaves of the Choctaw. After being emancipated following the American Civil War under an 1866 treaties that the United States made with each of the Five Civilized Tribes, African Americans who stayed with the Choctaw were called Choctaw Freedmen

The Choctaw Freedmen are former enslaved Africans, Afro-Indigenous, and African Americans who were emancipated and granted citizenship in the Choctaw Nation after the Civil War, according to the tribe's new peace treaty of 1866 with the United ...

. They were granted membership in the nation with voting rights. Others came to the area as laborers in the late 19th century. The county had a significant African-American population in the early 20th century, although this has since dwindled to almost nothing, as people left to seek work. Many African Americans worked in cotton cultivation and, after cotton's decline, they moved elsewhere for other work.

The territory comprising Pushmataha County had been part of the Choctaw Nation, Indian Territory. It was almost completely unimproved in the European-American sense. The Choctaw government owned land in "severalty", or common, controlling the communal land. The Choctaw had their own culture and did not need bridges, roads, or public works

Public works are a broad category of infrastructure projects, financed and procured by a government body for recreational, employment, and health and safety uses in the greater community. They include public buildings ( municipal buildings, ...

.

Early business leaders at statehood immediately sought to fund public improvements by asking local voters to pass bonds. The state government did not invest in such infrastructure. Businessmen tried to pass bridge bonds, as example, to build bridges across the Kiamichi River and Jack Fork Creek. These uniformly failed to gain approval, slowing the county's business development. Choctaw County, by contrast, passed bonds almost immediately, causing bridges to be built throughout the county. This proved excellent for business and commerce, and after this point Hugo grew significantly faster than Antlers.

Pushmataha County began to develop as European Americans settled and founded communities throughout the county. Each community built its own school, and raised money with which to hire a teacher or teachers. Residents also founded churches, mostly of various Protestant denominations with which they were affiliated. Residents of some of the more significant towns, such as Jumbo, Moyers, Clayton and Albion, also established cultural leagues or institutions—poetry clubs, music groups, and literary societies

A literary society is a group of people interested in literature. In the modern sense, this refers to a society that wants to promote one genre of writing or a specific author. Modern literary societies typically promote research, publish newslet ...

– in a bid for cultural refinement.

The Choctaw continued playing a role in the region; its members were elected to local government and served as other government and society leaders in Pushmataha County.

During World War I, county resident Tobias W. Frazier (Choctaw) was a soldier in the U.S. Army and a member of the famous Choctaw Code Talkers

The Choctaw code talkers were a group of Choctaw Indians from Oklahoma who pioneered the use of Native American languages as military code during World War I.

The government of the Choctaw Nation maintains that the men were the first American ...

. Other Code Talkers were from just over the border in McCurtain County. The fourteen soldiers were part of a pioneering use of American Indian languages as military code during war, to enable secret communications among the Allies. Their contributions helped gain victory and brought World War I to a quicker close.

Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

of the 1930s brought substantial improvements and infrastructure to the county: the federal Works Progress Administration

The Works Progress Administration (WPA; from 1935 to 1939, then known as the Work Projects Administration from 1939 to 1943) was an American New Deal agency that employed millions of jobseekers (mostly men who were not formally educated) to car ...

(or WPA) directed the construction with local workers of handsome, sturdy schools and school gymnasiums

A gym, short for gymnasium (: gymnasiums or gymnasia), is an indoor venue for exercise and sports. The word is derived from the ancient Greek term " gymnasion". They are commonly found in athletic and fitness centres, and as activity and learn ...

in numerous communities. The new buildings were built of native "red rock" gathered in nearby fields. They aged very well. Several are still in use, notably in Moyers, Rattan and Antlers. But the school at Jumbo was bulldozed by a local farmer in the 1990s to clear the field for cattle.

The Rural Electrification Administration

The United States Rural Utilities Service (RUS) administers programs that provide infrastructure or infrastructure improvements to rural communities. These include water and waste treatment, electric power, and telecommunications services. It i ...

provided guidance and funding to bring electricity to the rural county; electrical lines were strung, connecting homes to the electrical grid. These changes improved indoor conditions, and people began to acquire air conditioning

Air conditioning, often abbreviated as A/C (US) or air con (UK), is the process of removing heat from an enclosed space to achieve a more comfortable interior temperature, and in some cases, also controlling the humidity of internal air. Air c ...

and television from the 1950s on. People more often conducted their social lives inside rather than on town streets. Architectural design changed, as stores, churches and homes no longer had to allow for maximum ventilation via the free flow of air from open windows and doors.

Highways were paved and standardized in the 1950s, making travel easier and linking farms and countryside to the town markets, and the towns to one another. As people bought more automobiles, they stopped using the railroad. The Frisco ceased passenger operations in the late 1950s as unprofitable. Wholesale changes resulted from railroad restructuring in the later 20th century, and the Frisco ended freight operations in the early 1980s. At that time the trestle bridge

A trestle bridge is a bridge composed of a number of short spans supported by closely spaced frames usually carrying a railroad line. A trestle (sometimes tressel) is a rigid frame used as a support, historically a tripod used to support a st ...

s were dismantled, rails removed and the roadbed was abandoned to nature.

The Indian Nation Turnpike

The Indian Nation Turnpike, also designated State Highway 375 (SH-375), is a controlled-access highway, controlled-access toll road in southeastern Oklahoma, United States, running between Hugo, Oklahoma, Hugo and Henryetta, Oklahoma, Henryetta ...

, which opened in 1970, had only one interchange in all of Pushmataha County, at Antlers, connecting residents to freeway travel to Oklahoma City

Oklahoma City (), officially the City of Oklahoma City, and often shortened to OKC, is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Oklahoma, most populous city of the U.S. state of Oklahoma. The county seat ...

and Tulsa

Tulsa ( ) is the second-most-populous city in the state of Oklahoma, after Oklahoma City, and the 48th-most-populous city in the United States. The population was 413,066 as of the 2020 census. It is the principal municipality of the Tul ...

.

Geography

Pushmataha County's location in southeastern Oklahoma places it in a 10-county area designated for tourism purposes by theOklahoma Department of Tourism and Recreation

The Oklahoma Department of Tourism and Recreation is a government agency, department of the government of Oklahoma within the Tourism and Branding Cabinet. The Department is responsible for regulating Oklahoma's tourism industry and for promotin ...

as Choctaw Country

Choctaw Country is the Oklahoma Department of Tourism and Recreation's official tourism designation for Southeast Oklahoma. The name was previously Kiamichi Country until changed in honor of the Choctaw Nation headquartered there. The current ...

, previously Kiamichi Country. According to the U.S. Census Bureau

The United States Census Bureau, officially the Bureau of the Census, is a principal agency of the U.S. federal statistical system, responsible for producing data about the American people and economy. The U.S. Census Bureau is part of the U ...

, the county has a total area of , of which is land and (1.9%) is water.

Most of Pushmataha County is mountainous, with the exception of a relatively flat agricultural belt along the county's southern border. The Kiamichi River valley forms a crescent through the county from northeast to southwest. As was typical in prehistoric times, most human habitation has continued to be along this crescent.

The

The Kiamichi Mountains

The Kiamichi Mountains (Choctaw: ''Nʋnih Chaha Kiamitia'') are a mountain range in southeastern Oklahoma. A subrange within the larger Ouachita Mountains that extend from Oklahoma to western Arkansas, the Kiamichi Mountains sit within Le Flor ...

, a sub-range of the Ouachita Mountains

The Ouachita Mountains (), simply referred to as the Ouachitas, are a mountain range in western Arkansas and southeastern Oklahoma. They are formed by a thick succession of highly deformed Paleozoic strata constituting the Ouachita Fold and Thru ...

, occupy most of the land in the county. This mountain chain has never been formally defined, nor have its neighboring mountain chains, such as the Winding Stair Mountains

The Winding Stair Mountains is a mountain ridge located within the state of Oklahoma in Le Flore County, north of Talihina, Choctaw Nation.

Description

The ridge is part of a larger mountain range, the Ouachita Mountains, which is itself a sub ...

to the county's north or the Bok Tuklo Mountains to its east. The Kiamichi Mountains range to a height of approximately in the county. Many of its summits are in the shape of long furrows. The mountains are difficult to penetrate with road construction and large areas of the county are virtually empty of population.

Two rivers, the Kiamichi and Little River, flow through the county with their numerous tributaries. Sardis Lake, a flood-control facility in the northeastern part of the county, impounds the waters of Jack Fork Creek. Hugo Lake

Hugo Lake is manmade lake located east of Hugo, in Choctaw County, Oklahoma, United States. It is formed by Hugo Lake Dam on the Kiamichi River upstream from the Red River. The dam is visible from U.S. Route 70, which crosses its spillwa ...

, in Choctaw County, provides a similar function on the main stem of the river. It backs up the Kiamichi River northward into the county. Smaller impoundments include Clayton Lake

Clayton Lake is a small recreational lake in Pushmataha County, Oklahoma. It is located south of Clayton, Oklahoma.

The lake, which was built in 1935, impounds the waters of Peal Creek. It is operated as Clayton Lake State Park by the State o ...

, Nanih Waiya Lake

Nanih Waiya Lake is a small recreational lake in Pushmataha County, Oklahoma. It is in the Ouachita Mountains, northeast of Tuskahoma, Oklahoma, and from Talihina, Oklahoma.

The lake, which was built in 1958, impounds the waters of several sm ...

, Ozzie Cobb Lake and Pine Creek Lake.

Major tributaries of the Kiamichi River include Jack Fork Creek, Buck Creek, and Ten Mile Creek. Black Fork Creek and Pine Creek are the most significant tributaries of Little River.

A very small portion of the southwest corner of Pushmataha County features Lamey Slash, an area of wetlands which drains into Muddy Boggy Creek

Muddy Boggy Creek, also known as the Muddy Boggy River, is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed June 3, 2011 river in south central Oklahoma. The stream headwaters arise ju ...

. According to the ''Oxford English Dictionary'', the word "slash" is a noun which refers to a swamp. This is the only portion of the county not falling within the Kiamichi or Little River watersheds.

Interesting geographical features in the county include Rock Town, a small region of distinctive boulders in Johns Valley; Umbrella Rock near Clayton; McKinley Rocks near Tuskahoma; and the Potato Hills—unusually serrated landforms near Tuskahoma.

Interesting geographical features in the county include Rock Town, a small region of distinctive boulders in Johns Valley; Umbrella Rock near Clayton; McKinley Rocks near Tuskahoma; and the Potato Hills—unusually serrated landforms near Tuskahoma.

Adjacent counties

* Latimer County (north) *Le Flore County

LeFlore County is a county along the eastern border of the U.S state of Oklahoma. As of the 2020 census, its population was 48,129. Its county seat is Poteau. The county is part of the Fort Smith metropolitan area and the name honors a Choc ...

(northeast)

* McCurtain County

McCurtain County is a county in the southeastern corner of the U.S. state of Oklahoma. As of the 2020 census, its population was 30,814. Its county seat is Idabel. It was formed at statehood from part of the earlier Choctaw Nation in Indian ...

(east)

* Choctaw County (south)

* Atoka County

Atoka County is a county located in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. As of the 2020 census, the population was 14,143. Its county seat is Atoka. The county was formed before statehood from Choctaw Lands, and its name honors a Choctaw Chief named ...

(west)

* Pittsburg County (northwest)

Major highways

*Indian Nation Turnpike

The Indian Nation Turnpike, also designated State Highway 375 (SH-375), is a controlled-access highway, controlled-access toll road in southeastern Oklahoma, United States, running between Hugo, Oklahoma, Hugo and Henryetta, Oklahoma, Henryetta ...

* Oklahoma State Highway 2

State Highway 2, abbreviated SH-2 or OK-2, is a designation for two distinct highways maintained by the United States, U.S. state of Oklahoma. Though they were once connected, the middle section of highway was Concurrency (road), concurrent wit ...

* Oklahoma State Highway 3

State Highway 3, also abbreviated as SH-3 or OK-3, is a highway maintained by the U.S. state of Oklahoma. Traveling diagonally through Oklahoma, from the Panhandle to the far southeastern corner of the state, SH-3 is the longest state highway ...

* Oklahoma State Highway 43

State Highway 43 (SH-43 or OK-43) is a state highway in Oklahoma, United States. It runs 65.3 miles west-to-east through Coal, Atoka, Pushmataha and Pittsburg counties.

Route description

SH-43 begins at US-75/ SH-3 in Coalgate, the seat o ...

* Oklahoma State Highway 93

State Highway 93 (abbreviated SH-93) is a state highway in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. It runs north–south for in southeastern Oklahoma. SH-93 has no lettered spur routes.

Route description

SH-93 begins at U.S. Highway 70 (Oklahoma), US ...

* Wildlife management areas

Three areas designated forwildlife management

Wildlife management is the management process influencing interactions among and between wildlife, its Habitat, habitats and people to achieve predefined impacts. Wildlife management can include wildlife conservation, population control, gamekeepi ...

by the State of Oklahoma may be found in the county: The Pine Creek Wildlife Management Area, in the southeastern part of the county adjacent to Pine Creek Lake, the Pushmataha Wildlife Management Area, near Clayton, and part of the Honobia Creek Wildlife Management Area managed by the Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Conservation

The Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Conservation is an agency of the state of Oklahoma responsible for managing and protecting Oklahoma's wildlife population and their habitats. The Department is under the control of the Wildlife Conservation Co ...

. A multi-year research project regarding species management is underway in the Pushmataha Wildlife Management Area.

Climate

Pushmataha County, located at the heart of "Tornado Alley

Tornado Alley, also known as Tornado Valley, is a loosely defined location of the central United States and, in the 21st century, Canada where tornadoes are most frequent. The term was first used in 1952 as the title of a research project to st ...

", has a sometimes turbulent and often capricious climate.

High temperatures range during summer as high as 100 °F., often for several or more days in a row. Low temperatures during the winter can range as far as the single digits, but these "cold snaps" are rare and short-lived.

Rainfall varies across the county. Its easternmost area, in the vicinity of Honobia and north of Cloudy, receives approximately 52 inches of rain per year. Its western portions receive approximately 46 inches per year.

Snow is a rare event, and is almost never deeper than one inch. What snow falls generally melts within a day. Ice is a more frequent occurrence, sometimes breaking tree branches and downing power lines.

Tornado

A tornado is a violently rotating column of air that is in contact with the surface of Earth and a cumulonimbus cloud or, in rare cases, the base of a cumulus cloud. It is often referred to as a twister, whirlwind or cyclone, although the ...

season ranges from approximately April to September each year. Pushmataha County experiences powerful storms each year. A tornado striking Antlers in April 1945 devastated the town and killed 69 residents. Meteorologists

A meteorologist is a scientist who studies and works in the field of meteorology aiming to understand or predict Earth's atmosphere of Earth, atmospheric phenomena including the weather. Those who study meteorological phenomena are meteorologists ...

now believe it to have been the most powerful category of tornado possible, and the 32nd most devastating tornado in U.S. history. Modern-day residents are protected by a civil defense system consisting of "storm spotters" stationed throughout the populated areas during threatening weather, observing the skies for signs of rotations or funnels. In Antlers a system of three public-alert sirens sounds the alarm when a funnel is spotted, allowing residents to seek shelter.

During recent decades the county has experienced unstable weather patterns. It is currently in the midst of a multi-year drought, at least as measured by local standards. Rainfall has been much below average during this time.

Demographics

As of the census of 2010, there were 11,572 people, 4,809 households, and 3,247 families residing in the county. The population density was . There were 6,110 housing units at an average density of . The racial makeup of the county was 75%

As of the census of 2010, there were 11,572 people, 4,809 households, and 3,247 families residing in the county. The population density was . There were 6,110 housing units at an average density of . The racial makeup of the county was 75% White

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no chroma). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully (or almost fully) reflect and scatter all the visible wa ...

, 0.7% Black or African American, 17.6% Native American, 0.2% Asian, less than 0.1% Pacific Islander, 0.8% from other races, and 5.7% from two or more races. Nearly 3% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race. 96.2% spoke English, 1.7% Spanish and 1.6% Choctaw

The Choctaw ( ) people are one of the Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States, originally based in what is now Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama. The Choctaw language is a Western Muskogean language. Today, Choct ...

as their first language.

There were 4,809 households, of which half (50.9%) were married couples living together and a third (32.5%) were non-families, while the remainder were either a female or male householder with no spouse present. A third of households (29.2%) included children under the age of 18. Individuals living alone accounted for a third of households (28.4%) and solitary accounted for 14% of households. The average household size was 2.92 and the average family size was 3.52.

In the county, the population was spread out, with 22.4% under the age of 18, 7.5% from 18 to 24, 21% from 25 to 44, 28.9% from 45 to 64, and 20.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 44.3 years. For every 100 females there were 97.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 95.3 males.

The median income for a household in the county was $29,053, and the median income for a family was $36,887. Males had a median income of $25,509 versus $17,473 for females. The per capita income for the county was $16,583. Eighteen percent of families and 27.2% of the population were below the poverty line, including half (45.3%) of those under age 18 and 13.6% of those age 65 or over.

Politics

Economy

Pushmataha County has always been separated economically from the rest of Oklahoma by what the economists call the "Ouachita barrier". The Kiamichi Mountains and the mountains to the north of them, all subranges of the Ouachita Mountains, cause commerce with points to their north to be difficult.McAlester, Oklahoma

McAlester is the county seat of Pittsburg County, Oklahoma. The population was 18,363 at the time of the 2010 census, a 3.4 percent increase from 17,783 at the 2000 census.Shuller, Thurman"McAlester" profile ''Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and ...

, instead of being a regional trading center for Pushmataha County, instead seems very remote from it.

Natural resources have always been the lifeblood of Pushmataha County.

The county is one of the few in Oklahoma in which the petroleum industry

The petroleum industry, also known as the oil industry, includes the global processes of hydrocarbon exploration, exploration, extraction of petroleum, extraction, oil refinery, refining, Petroleum transport, transportation (often by oil tankers ...

does not, and has never had, a major presence drilling for oil. During recent years extraction companies have drilled successfully for natural gas, and this is increasingly common.

During the later days of the Indian Territory and early statehood asphalt

Asphalt most often refers to:

* Bitumen, also known as "liquid asphalt cement" or simply "asphalt", a viscous form of petroleum mainly used as a binder in asphalt concrete

* Asphalt concrete, a mixture of bitumen with coarse and fine aggregates, u ...

was mined at two locations: Jumbo

Jumbo (December 25, 1860 – September 15, 1885), also known as Jumbo the Elephant and Jumbo the Circus Elephant, was a 19th-century male African bush elephant born in Sudan. Jumbo was exported to Jardin des Plantes, a zoo in Paris, and then tr ...

and Sardis

Sardis ( ) or Sardes ( ; Lydian language, Lydian: , romanized: ; ; ) was an ancient city best known as the capital of the Lydian Empire. After the fall of the Lydian Empire, it became the capital of the Achaemenid Empire, Persian Lydia (satrapy) ...

. For a time these were economically successful, even at Jumbo, which experienced a catastrophic mine explosion in 1910 which killed numerous miners.

Timber is an economic mainstay. Lumber companies own large swaths of the county and operate vast tree plantations. Fast-growing

Timber is an economic mainstay. Lumber companies own large swaths of the county and operate vast tree plantations. Fast-growing pine trees

A pine is any conifer tree or shrub in the genus ''Pinus'' () of the family Pinaceae. ''Pinus'' is the sole genus in the subfamily Pinoideae.

''World Flora Online'' accepts 134 species-rank taxa (119 species and 15 nothospecies) of pines as cu ...

are the timber of choice, and in many areas of the county a virtual monoculture

In agriculture, monoculture is the practice of growing one crop species in a field at a time. Monocultures increase ease and efficiency in planting, managing, and harvesting crops short-term, often with the help of machinery. However, monocultur ...

of pine trees—at the expense of any other—has been established.

During the Twentieth Century a rapidly improving transportation network enabled Pushmataha County to advance economically. At this writing one federal highway and several state highways are in operation. In addition, the Indian Nation Turnpike, a four-lane turnpike constructed to national interstate highway standards, is in operation with interchanges at Antlers and Daisy.

Communities

City

* Antlers (county seat)Towns

*Albion

Albion is an alternative name for Great Britain. The oldest attestation of the toponym comes from the Greek language. It is sometimes used poetically and generally to refer to the island, but is less common than "Britain" today. The name for Scot ...

* Clayton

* Rattan

Rattan, also spelled ratan (from Malay language, Malay: ''rotan''), is the name for roughly 600 species of Old World climbing palms belonging to subfamily Calamoideae. The greatest diversity of rattan palm species and genera are in the clos ...

Census-designated place

* Finley * Moyers * Nashoba * TuskahomaUnincorporated communities

* Adel * Belzoni * Cloudy * Corinne * Darwin * Dela *Ethel

Ethel (also '' æthel'') is an Old English word meaning "noble", today often used as a feminine given name.

Etymology and historic usage

The word means ''æthel'' "noble".

It is frequently attested as the first element in Anglo-Saxon names, ...

* Fewell

* Honobia

* Jumbo

Jumbo (December 25, 1860 – September 15, 1885), also known as Jumbo the Elephant and Jumbo the Circus Elephant, was a 19th-century male African bush elephant born in Sudan. Jumbo was exported to Jardin des Plantes, a zoo in Paris, and then tr ...

* Kellond

* Kosoma

* Miller

A miller is a person who operates a mill, a machine to grind a grain (for example corn or wheat) to make flour. Milling is among the oldest of human occupations. "Miller", "Milne" and other variants are common surnames, as are their equivalents ...

* Ringold

* Oleta

* Sardis

Sardis ( ) or Sardes ( ; Lydian language, Lydian: , romanized: ; ; ) was an ancient city best known as the capital of the Lydian Empire. After the fall of the Lydian Empire, it became the capital of the Achaemenid Empire, Persian Lydia (satrapy) ...

* Snow

Snow consists of individual ice crystals that grow while suspended in the atmosphere—usually within clouds—and then fall, accumulating on the ground where they undergo further changes.

It consists of frozen crystalline water througho ...

* Sobol

* Stanley

Stanley may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Film and television

* ''Stanley'' (1972 film), an American horror film

* ''Stanley'' (1984 film), an Australian comedy

* ''Stanley'' (1999 film), an animated short

* ''Stanley'' (1956 TV series) ...

Ghost towns

* Abbott *Cohn Cohn is a Jewish surname (related to the last name Cohen). Notable people and characters with the surname include:

* Al Cohn (1925–1988), American jazz saxophonist, arranger and composer

* Alan D. Cohn, American government official

* Alfred A. ...

* Crum Creek

Crum Creek (from the Dutch, meaning "crooked creek") is a creek in Delaware County and Chester County, Pennsylvania, flowing approximately , generally in a southward direction and draining into the Delaware River in Eddystone, Pennsylvania. ...

* Dunbar

Dunbar () is a town on the North Sea coast in East Lothian in the south-east of Scotland, approximately east of Edinburgh and from the Anglo–Scottish border, English border north of Berwick-upon-Tweed.

Dunbar is a former royal burgh, and ...

* Eubanks

* Gee

* Johns

* Kiamichi

* Lyceum

The lyceum is a category of educational institution defined within the education system of many countries, mainly in Europe. The definition varies among countries; usually it is a type of secondary school. Basic science and some introduction to ...

* Nolia

* Rodney

* Sardis

Sardis ( ) or Sardes ( ; Lydian language, Lydian: , romanized: ; ; ) was an ancient city best known as the capital of the Lydian Empire. After the fall of the Lydian Empire, it became the capital of the Achaemenid Empire, Persian Lydia (satrapy) ...

* Wilson

* Zoraya

NRHP sites

The following sites in Pushmataha County are listed on theNational Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government's official United States National Register of Historic Places listings, list of sites, buildings, structures, Hist ...

:

* Albion State Bank, Albion

* Antlers Frisco Depot and Antlers Spring

The Frisco Depot and adjacent Antlers Spring are historic sites in Antlers, Oklahoma, United States. The sites are a part of the National Register of Historic Places, in which they appear as a single entry.

Establishing the Railroad

Antlers ...

, Antlers

* Choctaw Capitol Building

The Choctaw Capitol Building (; also known as Tuskahoma – Choctaw Council House, or simply as Tuskahoma,) is a historic building built in 1884 that housed the government of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma from 1884 to 1907. The building is loca ...

, Tuskahoma

* Clayton High School Auditorium, Clayton

* Fewell School, Nashoba

* James Martin Baggs Log Barn, Pickens

* Mato Kosyk House, Albion

* Snow School

Snow School is a historic school building in the rural community of Snow, Oklahoma, approximately 18 miles north of Antlers, Oklahoma. The school was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1988.

History

Snow was originally a small ...

, Snow

In 1984 a growing awareness of the county's rich history—encompassed by these and other historic sites—and the fact its legacy was becoming endangered—prompted a group of Antlers residents to found the Pushmataha County Historical Society. The society's first project was a successful initiative to obtain and preserve the Antlers Frisco Depot. It later completed a large-scale inventory of county cemeteries, and has undertaken numerous other projects since.Unpublished history of the Pushmataha County Historical Society, on file in the society.

A significant historical site is also located atop Big Mountain, north of Moyers and east of Kosoma. During World War II two aircraft flown by British pilots from a Royal Air Force base in Texas crashed in poor weather into White Rock Mountain and Big Mountain, killing four crewmen. In 2000 the AT6 Monument

The AT6 Monument is a granite memorial to Royal Air Force cadets who were killed while on a training flight during World War II. It stands on Big Mountain, north of Moyers, Oklahoma, in the United States, and was dedicated on February 20, 2000— ...

was dedicated in their memory at the crash site on Big Mountain, to international acclaim.

Notable residents

* Nicole DeHuff – actress * Tobias W. Frazier – Choctaw Code Talker *Mato Kosyk

Mato may refer to:

People

*Ana Mato (born 1959), Spanish politician

*Jakup Mato (1934–2005), Albanian publicist

*Mato Miloš (born 1993), Croatian footballer

*Mato Neretljak (born 1979), Croatian footballer

* Mato Valtonen (born 1955), Finnish ...

– poet

* Anna Lewis (historian) – historian, writer and professor retired to home she built in Pushmataha County

* Charles C. Stephenson Jr. – energy company CEO

* Kings of Leon

Kings of Leon is an American Rock music, rock band formed in Mount Juliet, Tennessee, in 1999. The band includes brothers Caleb, Nathan, and Jared Followill and their cousin Matthew Followill.

The band's early music was a blend of Southern roc ...

, rock band

References

External links

{{Coord, 34.42, -95.36, display=title, type:adm2nd_region:US-OK_source:UScensus1990 1907 establishments in Oklahoma Populated places established in 1907