Prince Philip, The Duke Of Edinburgh on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh (born Prince Philip of Greece and Denmark, later Philip Mountbatten; 10 June 19219 April 2021), was the husband of

Prince Philip () of Greece and Denmark was born on 10 June 1921 on the dining room table in Mon Repos, a villa on the Greek island of

Prince Philip () of Greece and Denmark was born on 10 June 1921 on the dining room table in Mon Repos, a villa on the Greek island of

After leaving Gordonstoun in early 1939, Philip completed a term as a

After leaving Gordonstoun in early 1939, Philip completed a term as a  Promotion to

Promotion to

Upon his wife's accession to the throne in 1952, Philip was appointed Admiral of the Sea Cadet Corps, Colonel-in-Chief of the British

Upon his wife's accession to the throne in 1952, Philip was appointed Admiral of the Sea Cadet Corps, Colonel-in-Chief of the British

Both Philip and Elizabeth were great-great-grandchildren of Queen Victoria, Elizabeth by descent from Victoria's eldest son, King Edward VII, and Philip by descent from Victoria's second daughter, Princess Alice of the United Kingdom, Princess Alice. Both were also Descendants of Christian IX of Denmark, descended from King Christian IX of Denmark.

Philip was also related to the House of Romanov through all four of his grandparents. His paternal grandmother was the granddaughter of Emperor Nicholas I of Russia. His paternal grandfather was a brother of Maria Feodorovna (Dagmar of Denmark), wife of Emperor Alexander III. His maternal grandmother was a sister of Alexandra Feodorovna (Alix of Hesse), wife of Emperor Nicholas II, and Elizabeth Feodorovna (Elisabeth of Hesse), wife of Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich of Russia. His maternal grandfather was the nephew of Maria Alexandrovna (Marie of Hesse), who was the wife of Emperor Alexander II.

In 1993 scientists were able to confirm the identity of the remains of several members of the Romanov family, more than seventy years after Murder of the Romanov family, their murder in 1918, by comparing their mitochondrial DNA to living matrilineal relatives, including Philip. Philip, Alexandra Feodorovna, and her children were all descended from Princess Alice through a purely female line.

Both Philip and Elizabeth were great-great-grandchildren of Queen Victoria, Elizabeth by descent from Victoria's eldest son, King Edward VII, and Philip by descent from Victoria's second daughter, Princess Alice of the United Kingdom, Princess Alice. Both were also Descendants of Christian IX of Denmark, descended from King Christian IX of Denmark.

Philip was also related to the House of Romanov through all four of his grandparents. His paternal grandmother was the granddaughter of Emperor Nicholas I of Russia. His paternal grandfather was a brother of Maria Feodorovna (Dagmar of Denmark), wife of Emperor Alexander III. His maternal grandmother was a sister of Alexandra Feodorovna (Alix of Hesse), wife of Emperor Nicholas II, and Elizabeth Feodorovna (Elisabeth of Hesse), wife of Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich of Russia. His maternal grandfather was the nephew of Maria Alexandrovna (Marie of Hesse), who was the wife of Emperor Alexander II.

In 1993 scientists were able to confirm the identity of the remains of several members of the Romanov family, more than seventy years after Murder of the Romanov family, their murder in 1918, by comparing their mitochondrial DNA to living matrilineal relatives, including Philip. Philip, Alexandra Feodorovna, and her children were all descended from Princess Alice through a purely female line.

The Duke of Edinburgh

at the Royal Family website

Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh

at the website of the

The Duke of Edinburgh's Award

Obituary

at BBC News Online * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Philip Of Edinburgh, Duke, Prince Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, 1921 births 2021 deaths 20th-century British male writers 20th-century British writers 21st-century British male writers 21st-century British writers Alumni of Schule Schloss Salem Barons Greenwich Battenberg family British Anglicans British environmentalists British field marshals British people of Danish descent British people of German descent British people of Russian descent British princes British royal consorts Burials at St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle Chancellors of the University of Cambridge Chancellors of the University of Edinburgh Chancellors of the University of Salford Chartered designers Deified men Dragon class sailors Dukes created by George VI Dukes of Edinburgh Earls of Merioneth, 1 English polo players Exiled royalty Fellows of the Royal Society (Statute 12) Field marshals of Australia Freemasons of the United Grand Lodge of England Graduates of Britannia Royal Naval College Greek emigrants to the United Kingdom Hereditary peers removed under the House of Lords Act 1999, Edinburgh Honorary Fellows of the Royal Microscopical Society House of Glücksburg (Greece) House of Windsor Lord high admirals of the United Kingdom Lords of the Admiralty Marshals of the Royal Air Force Members of Trinity House Members of the King's Privy Council for Canada Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Monarchy of Australia Monarchy of Canada Monarchy of New Zealand National Council of Social Service presidents Naturalised citizens of the United Kingdom Nobility from Corfu People educated at Cheam School People educated at Gordonstoun Presidents of the Football Association Presidents of the Marylebone Cricket Club Presidents of the Smeatonian Society of Civil Engineers Presidents of the Zoological Society of London Princes of Denmark Princes of Greece Recipients of the Croix de Guerre 1939–1945 (France) Royal Australian Air Force air marshals Royal Canadian Regiment Royal Marines generals Royal Navy admirals of the fleet Royal Navy officers of World War II Royal reburials Vanuatu deities

Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 19268 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until Death and state funeral of Elizabeth II, her death in 2022. ...

. As such, he was the consort of the British monarch

A royal consort is the spouse of a reigning monarch. Consorts of British monarchs have no constitutional status or power but many have had significant influence, and support the sovereign in their duties. There have been 11 royal consorts sinc ...

from his wife's accession on 6 February 1952 until his death in 2021, making him the longest-serving royal consort in history.

Philip was born in Greece into the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

and Danish royal families; his family was exiled from the country when he was eighteen months old. After being educated in France, Germany, and the United Kingdom, he joined the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

in 1939, when he was 18 years old. In July 1939, Philip began corresponding with the 13-year-old Princess Elizabeth, the elder daughter and heir presumptive

An heir presumptive is the person entitled to inherit a throne, peerage, or other hereditary honour, but whose position can be displaced by the birth of a person with a better claim to the position in question. This is in contrast to an heir app ...

of King George VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until his death in 1952. He was also the last Emperor of In ...

. During the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, he served with distinction in the British Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

and Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is bounded by the cont ...

fleets.

In the summer of 1946, the King granted Philip permission to marry Elizabeth, then aged 20. Before the official announcement of their engagement in July 1947, Philip stopped using his Greek and Danish royal titles and styles, became a naturalised

Naturalization (or naturalisation) is the legal act or process by which a non-national of a country acquires the nationality of that country after birth. The definition of naturalization by the International Organization for Migration of the ...

British subject

The term "British subject" has several different meanings depending on the time period. Before 1949, it referred to almost all subjects of the British Empire (including the United Kingdom, Dominions, and colonies, but excluding protectorates ...

, and adopted his maternal grandparents' surname Mountbatten

The Mountbatten family is a British family that originated as a branch of the German princely Battenberg family. The name was adopted by members of the Battenberg family residing in the United Kingdom on 14 July 1917, three days before the Br ...

. In November 1947, he married Elizabeth, was granted the style ''His Royal Highness

Royal Highness is a style (manner of address), style used to address or refer to some members of royal families, usually princes or princesses. Kings and their female Queen consort, consorts, as well as queens regnant, are usually styled ''Maje ...

'' and was created Duke of Edinburgh

Duke of Edinburgh, named after the capital city of Scotland, Edinburgh, is a substantive title that has been created four times since 1726 for members of the British royal family. It does not include any territorial landholdings and does not pr ...

, Earl of Merioneth

Earl of Merioneth was a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom created in 1947 along with the Duke of Edinburgh and the Baron Greenwich for Philip Mountbatten, later Prince Philip, upon his marriage to Princess Elizabeth, later Queen Eliza ...

, and Baron Greenwich

Baron Greenwich was a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom that has been created twice in British history.

History

Prior to the title's first creation in the Peerage of Great Britain in 1667, Charles II of England, King Charles II of E ...

. Philip left active military service when Elizabeth ascended the throne in 1952, having reached the rank of commander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank as well as a job title in many army, armies. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countri ...

. In 1957, he was created a British prince

Prince of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is a royal title normally granted to sons and grandsons of reigning and past British monarchs, plus consorts of female monarchs (by letters patent). The title is granted by the ...

. Philip had four children with Elizabeth: Charles

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English language, English and French language, French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic, Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''* ...

, Anne

Anne, alternatively spelled Ann, is a form of the Latin female name Anna (name), Anna. This in turn is a representation of the Hebrew Hannah (given name), Hannah, which means 'favour' or 'grace'. Related names include Annie (given name), Annie a ...

, Andrew

Andrew is the English form of the given name, common in many countries. The word is derived from the , ''Andreas'', itself related to ''aner/andros'', "man" (as opposed to "woman"), thus meaning "manly" and, as consequence, "brave", "strong", "c ...

, and Edward

Edward is an English male name. It is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements '' ēad'' "wealth, fortunate; prosperous" and '' weard'' "guardian, protector”.

History

The name Edward was very popular in Anglo-S ...

.

A sports enthusiast, Philip helped develop the equestrian

The word equestrian is a reference to equestrianism, or horseback riding, derived from Latin ' and ', "horse".

Horseback riding (or riding in British English)

Examples of this are:

*Equestrian sports

*Equestrian order, one of the upper classes in ...

event of carriage driving

Carriage driving is a form of competitive horse driving in harness in which larger two- or four-wheeled carriages (sometimes restored antiques) are pulled by a single horse, a pair, tandem or a four-in-hand team. Prince Philip, Duke of Edinb ...

. He was patron

Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows on another. In the history of art, art patronage refers to the support that princes, popes, and other wealthy and influential people ...

, president, or member of over 780 organisations, including the World Wide Fund for Nature

The World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) is a Swiss-based international non-governmental organization founded in 1961 that works in the field of wilderness preservation and the reduction of human impact on the environment. It was formerly named th ...

, and served as chairman of The Duke of Edinburgh's Award

The Duke of Edinburgh's Award (commonly abbreviated DofE) is a youth awards programme founded in the United Kingdom in 1956 by the Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, which has since expanded to 144 nations. The awards recognise adolescents and ...

, a youth awards programme for people aged 14 to 24. Philip is the longest-lived male member of the British royal family. He retired from royal duties in 2017, aged 96, having completed 22,219 solo engagements and 5,493 speeches since 1952, and died at the age of 99 at Windsor Castle

Windsor Castle is a List of British royal residences, royal residence at Windsor, Berkshire, Windsor in the English county of Berkshire, about west of central London. It is strongly associated with the Kingdom of England, English and succee ...

.

Early life and education

Family, infancy and exile from Greece

Prince Philip () of Greece and Denmark was born on 10 June 1921 on the dining room table in Mon Repos, a villa on the Greek island of

Prince Philip () of Greece and Denmark was born on 10 June 1921 on the dining room table in Mon Repos, a villa on the Greek island of Corfu

Corfu ( , ) or Kerkyra (, ) is a Greece, Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands; including its Greek islands, small satellite islands, it forms the margin of Greece's northwestern frontier. The island is part of the Corfu (regio ...

. He was the only son and fifth and final child of Prince Andrew of Greece and Denmark

Prince Andrew of Greece and Denmark (; – 3 December 1944) was the seventh child and fourth son of King George I and Queen Olga of Greece. He was a grandson of King Christian IX of Denmark and the father of Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh. ...

and his wife, Princess Alice of Battenberg

Princess Alice of Battenberg (Victoria Alice Elizabeth Julia Marie; 25 February 1885 – 5 December 1969) was the mother of Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, mother-in-law of Queen Elizabeth II, and paternal grandmother of King Charles III. Af ...

. Philip's father was the fourth son of King George I and Queen Olga of Greece

Olga Constantinovna of Russia (; 18 June 1926) was Queen of Greece as the wife of King George I. She was briefly the regent of Greece in 1920.

A member of the Romanov dynasty, Olga was the oldest daughter of Grand Duke Constantine Nikolaie ...

, and his mother was the eldest child of Louis Mountbatten, 1st Marquess of Milford Haven

Louis Alexander Mountbatten, 1st Marquess of Milford Haven (24 May 185411 September 1921), formerly Prince Louis Alexander of Battenberg, was a British naval officer and German prince related by marriage to the British royal family.

Although ...

, and Victoria Mountbatten, Marchioness of Milford Haven (formerly Prince Louis of Battenberg and Princess Victoria of Hesse and by Rhine). A member of the House of Glücksburg

The House of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg, also known by its short name as the House of Glücksburg, is the senior surviving branch of the German House of Oldenburg, one of Europe's oldest royal houses. Oldenburg house members hav ...

, Philip was a prince of both Greece and Denmark by virtue of his patrilineal descent from George I of Greece and George's father, Christian IX of Denmark; he was from birth in the line of succession

An order, line or right of succession is the line of individuals necessitated to hold a high office when it becomes vacated, such as head of state or an honour such as a title of nobility.Margarita

A margarita is a cocktail consisting of tequila, triple sec, and lime juice. Some margarita recipes include simple syrup as well and are often served with salt on the rim of the glass. Margaritas can be served either shaken with ice (on the rock ...

, Theodora, Cecilie

Cecilie is a given name. Notable people with the name include:

*Cecilie Broch Knudsen (born 1950), artist and rector of the Oslo National Academy of the Arts

*Cecilie Henriksen (born 1986), football forward from Næstved, Denmark

*Cecilie Løvei ...

, and Sophie

Sophie is a feminine given name, another version of Sophia, from the Greek word for "wisdom".

People with the name Born in the Middle Ages

* Sophie, Countess of Bar (c. 1004 or 1018–1093), sovereign Countess of Bar and lady of Mousson

* Soph ...

. He was baptised

Baptism (from ) is a Christians, Christian sacrament of initiation almost invariably with the use of water. It may be performed by aspersion, sprinkling or affusion, pouring water on the head, or by immersion baptism, immersing in water eit ...

in the Greek Orthodox

Greek Orthodox Church (, , ) is a term that can refer to any one of three classes of Christian Churches, each associated in some way with Greek Christianity, Levantine Arabic-speaking Christians or more broadly the rite used in the Eastern Rom ...

rite at St. George's Church in the Old Fortress in Corfu. His godparents were his paternal grandmother, Queen Olga of Greece; his cousin George, Crown Prince of Greece; his uncle Lord Louis Mountbatten

Admiral of the Fleet Louis Francis Albert Victor Nicholas Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma (born Prince Louis of Battenberg; 25 June 1900 – 27 August 1979), commonly known as Lord Mountbatten, was a British statesman, Royal Navy off ...

; and the municipality of Corfu, represented by its mayor, Alexandros Kokotos, and by the president of the council, Stylianos Maniarizis.

Shortly after Philip's birth, his maternal grandfather died in London. The Marquess of Milford Haven was a naturalised British subject

The term "British subject" has several different meanings depending on the time period. Before 1949, it referred to almost all subjects of the British Empire (including the United Kingdom, Dominions, and colonies, but excluding protectorates ...

who, after a career in the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

, had renounced his German titles and adopted the surname Mountbatten

The Mountbatten family is a British family that originated as a branch of the German princely Battenberg family. The name was adopted by members of the Battenberg family residing in the United Kingdom on 14 July 1917, three days before the Br ...

—an Anglicised

Anglicisation or anglicization is a form of cultural assimilation whereby something non-English becomes assimilated into or influenced by the culture of England. It can be sociocultural, in which a non-English place adopts the English language ...

version of Battenberg—during the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, owing to anti-German sentiment

Anti-German sentiment (also known as anti-Germanism, Germanophobia or Teutophobia) is fear or dislike of Germany, its Germans, people, and its Culture of Germany, culture. Its opposite is Germanophile, Germanophilia.

Anti-German sentiment main ...

in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

. After visiting London for his grandfather's memorial service

A memorial is an object or place which serves as a focus for the memory or the commemoration of something, usually an influential, deceased person or a historical, tragic event. Popular forms of memorials include landmark objects such as home ...

, Philip and his mother returned to Greece, where Prince Andrew had remained to command a Greek Army

The Hellenic Army (, sometimes abbreviated as ΕΣ), formed in 1828, is the land force of Greece. The term '' Hellenic'' is the endogenous synonym for ''Greek''. The Hellenic Army is the largest of the three branches of the Hellenic Armed F ...

division embroiled in the Greco-Turkish War.

Greece suffered significant losses in the war and the Turks made substantial gains. Philip's uncle and high commander of the Greek expeditionary force, King Constantine I

Constantine I (, romanized: ''Konstantínos I''; – 11 January 1923) was King of Greece from 18 March 1913 to 11 June 1917 and again from 19 December 1920 to 27 September 1922. He was commander-in-chief of the Hellenic Army during the unsu ...

, was blamed for the defeat and was forced to abdicate in September 1922. The new military government arrested Andrew, along with others. General Georgios Hatzianestis

Georgios Hatzianestis (, 3 December 1863 – 15 November 1922) was a Greek artillery and general staff officer who rose to the rank of lieutenant general. He is best known as the commander-in-chief of the Army of Asia Minor at the time of th ...

, who was commanding officer

The commanding officer (CO) or commander, or sometimes, if the incumbent is a general officer, commanding general (CG), is the officer in command of a military unit. The commanding officer has ultimate authority over the unit, and is usually give ...

of the army, and five senior politicians were arrested, tried, and executed in the Trial of the Six

The Trial of the Six (, ''Díki ton Éx(i)'') or the Execution of the Six was the trial for treason, in late 1922, of the Anti-Venizelist officials held responsible for the Greek military defeat in Asia Minor. The trial culminated in the death ...

. Andrew's life was also believed to be in danger and Alice was under surveillance. Finally, in December, a revolutionary court banished Andrew from Greece for life. The British naval vessel evacuated Andrew's family, with Philip carried to safety in a fruit box.

Upbringing in France, Britain and Germany

Philip's family settled in a house in the Paris suburb ofSaint-Cloud

Saint-Cloud () is a French commune in the western suburbs of Paris, France, from the centre of Paris. Like other communes of Hauts-de-Seine such as Marnes-la-Coquette, Neuilly-sur-Seine and Vaucresson, Saint-Cloud is one of France's wealthie ...

lent to them by his wealthy aunt, Princess George of Greece and Denmark. During his time there, Philip was first educated at The Elms, an American school in Paris run by Donald MacJannet, who described Philip as a "know it all smarty person, but always remarkably polite". In 1930 Philip was sent to Britain to live with his maternal grandmother at Kensington Palace

Kensington Palace is a royal residence situated within Kensington Gardens in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea in London, England. It has served as a residence for the British royal family since the 17th century and is currently the ...

and his uncle George Mountbatten, 2nd Marquess of Milford Haven, at Lynden Manor in Bray, Berkshire

Bray, occasionally Bray on Thames, is a suburban village and civil parish in the Windsor and Maidenhead district, in the ceremonial county of Berkshire. It sits on the banks of the River Thames, to the southeast of Maidenhead with which it is ...

. He was then enrolled at Cheam School

Cheam School is a mixed preparatory school located in Headley, in the civil parish of Ashford Hill with Headley in Hampshire. Originally a boys school, Cheam was founded in 1645 by George Aldrich.

History

The school started in Cheam, Surre ...

. Over the next three years, his four sisters married German prince

The German nobility () and royalty were status groups of the medieval society in Central Europe, which enjoyed certain privileges relative to other people under the laws and customs in the German-speaking area, until the beginning of the 20th ...

s and moved to Germany, his mother was diagnosed with schizophrenia

Schizophrenia () is a mental disorder characterized variously by hallucinations (typically, Auditory hallucination#Schizophrenia, hearing voices), delusions, thought disorder, disorganized thinking and behavior, and Reduced affect display, f ...

and placed in an asylum, and his father took up residence in Monte Carlo

Monte Carlo ( ; ; or colloquially ; , ; ) is an official administrative area of Monaco, specifically the Ward (country subdivision), ward of Monte Carlo/Spélugues, where the Monte Carlo Casino is located. Informally, the name also refers to ...

. Philip had little contact with his mother for the remainder of his childhood.

In 1933 Philip was sent to Schule Schloss Salem

Schule Schloss Salem (Anglicisation: ''School of Salem Castle'') is a boarding school with campuses in Salem and Überlingen in Baden-Württemberg, Southern Germany.

It offers the German Abitur and the International Baccalaureate (IB). With se ...

in Germany, which had the "advantage of saving school fees", because it was owned by the family of his brother-in-law Berthold, Margrave of Baden

Berthold Prinz und Markgraf von Baden (24 February 1906 – 27 October 1963), styled Margrave of Baden and Duke of Zähringen, was the head of the House of Baden, which had reigned over the Grand Duchy of Baden until 1918, from 1929 until his deat ...

. With the rise of Nazism

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party ( or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported the ideology of Nazism. Its precursor ...

in Germany, Salem's Jewish founder, Kurt Hahn

Kurt Matthias Robert Martin Hahn (5 June 1886 – 14 December 1974) was a German educator. He was decisive in founding Stiftung Louisenlund, Schule Schloss Salem, Gordonstoun, Outward Bound, the Duke of Edinburgh's Award, and the first of the U ...

, fled persecution and founded Gordonstoun School

Gordonstoun School ( ) is an elite co-educational private school for boarding and day pupils in Moray, Scotland. Two generations of British royalty were educated at Gordonstoun, including Prince Philip and his son King Charles III. Musician Davi ...

in Scotland, to which Philip moved after two terms at Salem. In 1937, his sister Cecilie; her husband, Georg Donatus, Hereditary Grand Duke of Hesse

Georg Donatus, Hereditary Grand Duke of Hesse (''Georg Donatus Wilhelm Nikolaus Eduard Heinrich Karl'', 8 November 1906 – 16 November 1937) was the first child of Ernest Louis, Grand Duke of Hesse, and his second wife, Princess Eleono ...

; their two sons; and Georg Donatus's mother were killed in an air crash at Ostend; Philip, then 16 years old, attended the funeral in Darmstadt

Darmstadt () is a city in the States of Germany, state of Hesse in Germany, located in the southern part of the Frankfurt Rhine Main Area, Rhine-Main-Area (Frankfurt Metropolitan Region). Darmstadt has around 160,000 inhabitants, making it the ...

. Cecilie and Georg Donatus were members of the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party ( or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported the ideology of Nazism. Its precursor ...

. The following year, Philip's uncle and guardian Lord Milford Haven died of bone marrow cancer. Milford Haven's younger brother Lord Louis took parental responsibility for Philip for the remainder of his youth.

Philip did not speak Greek because he had left Greece as an infant. In 1992 he said that he "could understand a certain amount". He stated that he thought of himself as Danish and spoke mostly English, while his family was multilingual. Known for his charm in his youth, Philip was linked to several women, including Osla Benning.

Naval and wartime service

After leaving Gordonstoun in early 1939, Philip completed a term as a

After leaving Gordonstoun in early 1939, Philip completed a term as a cadet

A cadet is a student or trainee within various organisations, primarily in military contexts where individuals undergo training to become commissioned officers. However, several civilian organisations, including civil aviation groups, maritime ...

at the Royal Naval College, Dartmouth, then repatriated

Repatriation is the return of a thing or person to its or their country of origin, respectively. The term may refer to non-human entities, such as converting a foreign currency into the currency of one's own country, as well as the return of mi ...

to Greece, living with his mother in Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

for a month in mid-1939. At the behest of King George II of Greece, his first cousin, he returned to Britain in September to resume training for the Royal Navy. He graduated from Dartmouth the next year as the best cadet in his course. During the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, he continued to serve in the British forces

The British Armed Forces are the unified military forces responsible for the defence of the United Kingdom, its Overseas Territories and the Crown Dependencies. They also promote the UK's wider interests, support international peacekeeping ef ...

, while two of his brothers-in-law, Prince Christoph of Hesse

Prince Christoph of Hesse (Christoph Ernst August; 14 May 1901 – 7 October 1943) was a nephew of Kaiser Wilhelm II. He was an SS-Oberführer in the Allgemeine SS and an officer in the Luftwaffe Reserve, killed on active duty in a plane crash ...

and Berthold, Margrave of Baden, fought on the opposing German side. Philip was appointed as a midshipman

A midshipman is an officer of the lowest Military rank#Subordinate/student officer, rank in the Royal Navy, United States Navy, and many Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth navies. Commonwealth countries which use the rank include Royal Cana ...

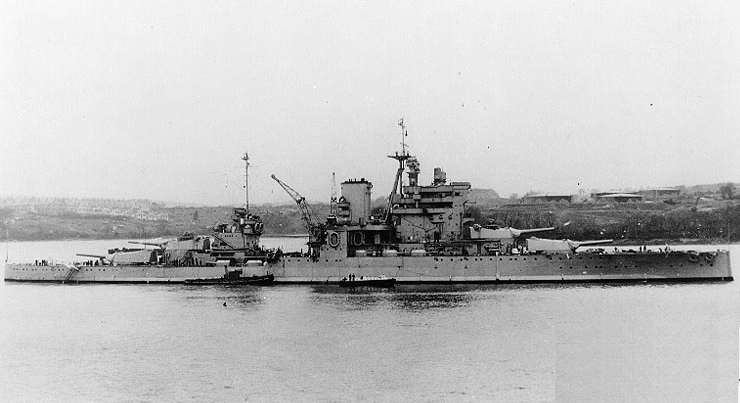

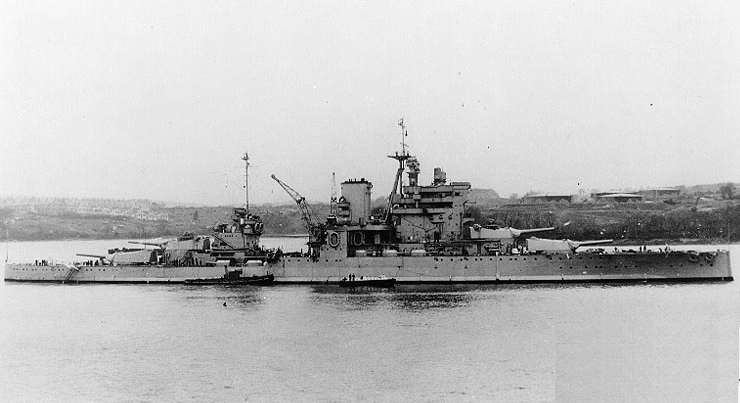

in January 1940. He spent four months on the battleship , protecting convoy

A convoy is a group of vehicles, typically motor vehicles or ships, traveling together for mutual support and protection. Often, a convoy is organized with armed defensive support and can help maintain cohesion within a unit. It may also be used ...

s of the Australian Expeditionary Force in the Indian Ocean, followed by shorter postings on , on , and in British Ceylon

British Ceylon (; ), officially British Settlements and Territories in the Island of Ceylon with its Dependencies from 1802 to 1833, then the Island of Ceylon and its Territories and Dependencies from 1833 to 1931 and finally the Island of Cey ...

. After the invasion of Greece by Italy in October 1940, he was transferred from the Indian Ocean to the battleship in the Mediterranean Fleet

The British Mediterranean Fleet, also known as the Mediterranean Station, was a formation of the Royal Navy. The Fleet was one of the most prestigious commands in the navy for the majority of its history, defending the vital sea link between ...

.

Philip was commissioned as a sub-lieutenant on 1 February 1941 after a series of courses at Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Hampshire, England. Most of Portsmouth is located on Portsea Island, off the south coast of England in the Solent, making Portsmouth the only city in En ...

, in which he gained the top grade in four out of five sections of the qualifying examination. Among other engagements, he was involved in the Battle of Crete

The Battle of Crete (, ), codenamed Operation Mercury (), was a major Axis Powers, Axis Airborne forces, airborne and amphibious assault, amphibious operation during World War II to capture the island of Crete. It began on the morning of 20 May ...

and was mentioned in dispatches

To be mentioned in dispatches (or despatches) describes a member of the armed forces whose name appears in an official report written by a superior officer and sent to the high command, in which their gallant or meritorious action in the face of t ...

for his service during the Battle of Cape Matapan

The Battle of Cape Matapan () was a naval battle during the Second World War between the Allies, represented by the navies of the United Kingdom and Australia, and the Royal Italian Navy, from 27 to 29 March 1941. Cape Matapan is on the so ...

, in which he controlled the battleship's searchlight

A searchlight (or spotlight) is an apparatus that combines an extremely luminosity, bright source (traditionally a carbon arc lamp) with a mirrored parabolic reflector to project a powerful beam of light of approximately parallel rays in a part ...

s. He was also awarded the Greek War Cross

The War Cross () is a military decoration of Greece, awarded for heroism in wartime to both Greeks and foreign allies. There have been three versions of the cross, the 1917 version covering World War I, the 1940 version covering the Second World W ...

. In June 1942, he was appointed to the destroyer , which was involved in convoy escort tasks on the east coast of Britain, as well as the Allied invasion of Sicily

The Allied invasion of Sicily, also known as the Battle of Sicily and Operation Husky, was a major campaign of World War II in which the Allies of World War II, Allied forces invaded the island of Sicily in July 1943 and took it from the Axis p ...

.

Promotion to

Promotion to lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a Junior officer, junior commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations, as well as fire services, emergency medical services, Security agency, security services ...

followed on 16 July 1942. In October of the same year, aged 21, Philip became first lieutenant

First lieutenant is a commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces; in some forces, it is an appointment.

The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations, but in most forces it is sub-divided into a se ...

of HMS ''Wallace''. He was one of the youngest first lieutenants in the Royal Navy. During the invasion of Sicily, in July 1943, as second-in-command

Second-in-command (2i/c or 2IC) is a title denoting that the holder of the title is the second-highest authority within a certain organisation.

Usage

In the British Army or Royal Marines, the second-in-command is the deputy commander of a unit, f ...

of ''Wallace'', he saved his ship from a night bomber

A night bomber is a bomber aircraft intended specifically for carrying out bombing missions at night. The term is now mostly of historical significance. Night bombing began in World War I and was widespread during World War II. A number of moder ...

attack. He devised a plan to launch a raft

A raft is any flat structure for support or transportation over water. It is usually of basic design, characterized by the absence of a hull. Rafts are usually kept afloat by using any combination of buoyant materials such as wood, sealed barre ...

with smoke floats that successfully distracted the bombers, allowing the ship to slip away unnoticed. In 1944, he moved on to the new destroyer, , where he saw service with the British Pacific Fleet

The British Pacific Fleet (BPF) was a Royal Navy formation that saw action against Japan during the Second World War. It was formed from aircraft carriers, other surface warships, submarines and supply vessels of the RN and British Commonwealth ...

in the 27th Destroyer Flotilla. He was present in Tokyo Bay

is a bay located in the southern Kantō region of Japan spanning the coasts of Tokyo, Kanagawa Prefecture, and Chiba Prefecture, on the southern coast of the island of Honshu. Tokyo Bay is connected to the Pacific Ocean by the Uraga Channel. Th ...

when the Japanese Instrument of Surrender

The Japanese Instrument of Surrender was the written agreement that formalized the surrender of the Empire of Japan, marking the end of hostilities in World War II. It was signed by representatives from the Empire of Japan and from the Allied n ...

was signed. Philip returned to the United Kingdom on the ''Whelp'' in January 1946 and was posted as an instructor at , the Petty Officers' School in Corsham

Corsham is a historic market town and civil parishes in England, civil parish in west Wiltshire, England. It is at the southwestern edge of the Cotswolds, just off the A4 road (England), A4 national route. It is southwest of Swindon, east of ...

, Wiltshire.

Marriage

In 1939King George VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until his death in 1952. He was also the last Emperor of In ...

and Queen Elizabeth Queen Elizabeth, Queen Elisabeth or Elizabeth the Queen may refer to:

Queens regnant

* Elizabeth I (1533–1603; ), Queen of England and Ireland

* Elizabeth II (1926–2022; ), Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms

* Queen B ...

toured the Royal Naval College, Dartmouth. During the visit, the Queen and Lord Louis Mountbatten asked his nephew Philip to escort the royal couple's daughters, 13-year-old Elizabeth

Elizabeth or Elisabeth may refer to:

People

* Elizabeth (given name), a female given name (including people with that name)

* Empress Elisabeth (disambiguation), lists various empresses named ''Elisabeth'' or ''Elizabeth''

* Princess Elizabeth ...

and 9-year-old Margaret

Margaret is a feminine given name, which means "pearl". It is of Latin origin, via Ancient Greek and ultimately from Iranian languages, Old Iranian. It has been an English language, English name since the 11th century, and remained popular thro ...

, who were Philip's third cousins through Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days, which was longer than th ...

and second cousins once removed through King Christian IX of Denmark.Alexandra of Yugoslavia

Alexandra (, romanized: ''Alexándra'', sh-Cyrl-Latn, separator=/, Александра, Aleksandra, in 1922 retroactively recognised as Princess Alexandra of Greece and Denmark; 25 March 1921– 30 January 1993) was the last Queen of Yugosla ...

quoted in Philip and Elizabeth had first met as children in 1934 at the wedding of Elizabeth's uncle Prince George, Duke of Kent

Prince George, Duke of Kent (George Edward Alexander Edmund; 20 December 1902 – 25 August 1942) was a member of the British royal family, the fourth son of King George V and Queen Mary. He was a younger brother of kings Edward VIII and George ...

, to Philip's first cousin, Princess Marina of Greece and Denmark

Princess Marina, Duchess of Kent (born Princess Marina of Greece and Denmark, ; 27 August 1968) was a Greek royal family, Greek and Danish princess by birth and a British princess by marriage. She was a daughter of Prince Nicholas of Greece and ...

. After their 1939 meeting, Elizabeth fell in love with Philip, and they began to exchange letters.

Eventually, in the summer of 1946, Philip asked George VI for his daughter's hand in marriage. The King granted his request, provided that any formal engagement be delayed until Elizabeth's 21st birthday the following April. By March 1947, Philip had adopted the surname Mountbatten from his mother's family and had stopped using his Greek and Danish royal titles upon becoming a naturalised British subject.." The British press reported on the remark as indicative of racial intolerance, but the Chinese authorities were reportedly unconcerned. Chinese students studying in the UK, an official explained, were often told in jest not to stay away too long, lest they go "round-eyed". His comment did not affect Sino-British relations, but it shaped his reputation. Philip also made comments on the eating habits of Cantonese people

The Cantonese people ( zh, s=广府人, t=廣府人, j=gwong2 fu2 jan4, cy=Gwóngfú Yàhn, first=t, labels=no) or Yue people ( zh, s=粤人, t=粵人, j=jyut6 jan4, cy=Yuht Yàhn, first=t, labels=no), are a Han Chinese subgroup originating fro ...

, stating: "If it has four legs and is not a chair, has wings and is not an airplane, or swims and is not a submarine, the Cantonese will eat it." In Australia he asked an Indigenous Australian

Indigenous Australians are people with familial heritage from, or recognised membership of, the various ethnic groups living within the territory of contemporary Australia prior to History of Australia (1788–1850), British colonisation. The ...

entrepreneur: "Do you still throw spears at each other?"

In 2011 historian David Starkey

Dr. David Robert Starkey (born 3 January 1945) is a British historian, radio and television presenter, with views that he describes as conservative. The only child of Quaker parents, he attended Kirkbie Kendal School, Kendal Grammar School b ...

described Philip as a kind of "HRH Victor Meldrew". For example, in May 1999, British newspapers accused Philip of insulting deaf children at a pop concert in Wales by saying: "No wonder you are deaf listening to this row." Later, Philip wrote: "The story is largely invention. It so happens that my mother was quite seriously deaf and I have been Patron of the Royal National Institute for the Deaf for ages, so it's hardly likely that I would do any such thing." When he and Elizabeth met Stephen Menary, an army cadet blinded by a Real IRA bomb, and Elizabeth enquired how much sight he retained, Philip quipped: "Not a lot, judging by the tie he's wearing." Menary later said: "I think he just tries to put people at ease by trying to make a joke. I certainly didn't take any offence." Philip's comparison of prostitutes and wives was also perceived as offensive after he reportedly stated: "I don't think a prostitute is more moral than a wife, but they are doing the same thing."

Centenary

To mark the centenary of Philip's birth in June 2021, theRoyal Collection Trust

The Royal Collection of the British royal family is the largest private art collection in the world.

Spread among 13 occupied and historic royal residences in the United Kingdom, the collection is owned by King Charles III and overseen by the ...

held an exhibition at Windsor Castle and the Palace of Holyroodhouse

The Palace of Holyroodhouse ( or ), commonly known as Holyrood Palace, is the official residence of the British monarch in Scotland. Located at the bottom of the Royal Mile in Edinburgh, at the opposite end to Edinburgh Castle, Holyrood has ...

. Titled ''Prince Philip: A Celebration'', it showcased around 150 personal items related to him, including his wedding card, wedding menu, midshipman's logbook

A logbook (or log book) is a record used to record states, events, or conditions applicable to complex machines or the personnel who operate them. Logbooks are commonly associated with the operation of aircraft, nuclear plants, particle accelera ...

from 1940 to 1941, Chair of Estate, and the coronation robes and coronet

In British heraldry, a coronet is a type of crown that is a mark of rank of non-reigning members of the royal family and peers. In other languages, this distinction is not made, and usually the same word for ''crown'' is used irrespective of ra ...

that he wore for his wife's coronation in 1953. George Alexis Weymouth's portrait of Philip in the ruins of Windsor Castle after the fire of 1992 formed part of a focus on Philip's involvement with the subsequent restoration.

The Royal Horticultural Society

The Royal Horticultural Society (RHS), founded in 1804 as the Horticultural Society of London, is the UK's leading gardening charity.

The RHS promotes horticulture through its five gardens at Wisley (Surrey), Hyde Hall (Essex), Harlow Carr ...

also marked Philip's centenary by breeding a new rose in his honour, christened " The Duke of Edinburgh Rose", created by British rose breeder Harkness Roses

Harkness Roses (a trading name of R. Harkness & Co. Ltd) are rose breeders based at Hitchin, Hertfordshire in England. The nursery was founded in 1879 in Yorkshire by brothers, John and Robert Harkness. Early varieties include 'Mrs. Harkness', ' ...

. Elizabeth, as patron of the society, was given the deep pink commemorative rose in honour of her husband, and she remarked that "It looks lovely". A Duke of Edinburgh Rose has since been planted in the mixed rose border of Windsor Castle's East Terrace Garden. Philip played a major role in the garden's design.

In September 2021, the Royal National Lifeboat Institution

The Royal National Lifeboat Institution (RNLI) is the largest of the lifeboat (rescue), lifeboat services operating around the coasts of the United Kingdom, Republic of Ireland, Ireland, the Channel Islands, and the Isle of Man, as well as on s ...

honoured Philip by naming their new state-of-the-art

The state of the art (SOTA or SotA, sometimes cutting edge, leading edge, or bleeding edge) refers to the highest level of general development, as of a device, technique, or scientific field achieved at a particular time. However, in some contex ...

lifeboat ''Duke of Edinburgh''. The tribute was initially planned to mark his 100th birthday. In the same month, a documentary initially planned for his centenary was broadcast on BBC One

BBC One is a British free-to-air public broadcast television channel owned and operated by the BBC. It is the corporation's oldest and flagship channel, and is known for broadcasting mainstream programming, which includes BBC News television b ...

under the title ''Prince Philip: The Royal Family Remembers'', with contributions from his children, their spouses, and seven of his grandchildren.

Portrayals

Philip has been portrayed by several actors, includingStewart Granger

Stewart Granger (born James Lablache Stewart; 6 May 1913 – 16 August 1993) was a British film actor, mainly associated with heroic and romantic leading roles. He was a popular leading man from the 1940s to the early 1960s, rising to fame thr ...

(''The Royal Romance of Charles and Diana

''The Royal Romance of Charles and Diana'' is a 1982 American made-for-television biographical drama film that depicts the events leading to the wedding of Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer. The film was directed by Peter Levin and starred Ca ...

'', 1982), Christopher Lee

Sir Christopher Frank Carandini Lee (27 May 1922 – 7 June 2015) was an English actor and singer. In a career spanning more than sixty years, Lee became known as an actor with a deep and commanding voice who often portrayed villains in horr ...

(''Charles & Diana: A Royal Love Story'', 1982), David Threlfall

David John Threlfall (born 12 October 1953) is an English stage, film and television actor and director. He is best known for playing Frank Gallagher in Channel 4's series '' Shameless''. He has also directed several episodes of the show. In Ap ...

('' The Queen's Sister'', 2005), James Cromwell

James Oliver Cromwell (born January 27, 1940) is an American actor. Known for his extensive work as a character actor, he has received a Primetime Emmy Award as well as a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for '' Babe'' ( ...

('' The Queen'', 2006), and Finn Elliot, Matt Smith

Matthew Robert Smith (born 28 October 1982) is an English actor. He is known for playing the Eleventh Doctor in the BBC science fiction television series ''Doctor Who'' (2010–2013), Prince Philip in Netflix's historical series ''The Crown ( ...

, Tobias Menzies

Tobias Simpson Menzies (born 7 March 1974) is an English actor. He is known for playing Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, in the third and fourth seasons of the series ''The Crown'', for which he won the Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding S ...

, and Jonathan Pryce

Sir Jonathan Pryce (born John Price; 1 June 1947) is a Welsh actor. He is known for his performances on stage and in film and television. He has received numerous awards, including two Tony Awards and two Laurence Olivier Awards as well as nom ...

(''The Crown

The Crown is a political concept used in Commonwealth realms. Depending on the context used, it generally refers to the entirety of the State (polity), state (or in federal realms, the relevant level of government in that state), the executive ...

'', 2016 onwards). He also appears as a fictional character in Nevil Shute

Nevil Shute Norway (17 January 189912 January 1960) was an English novelist and aeronautical engineer who spent his later years in Australia. He used his full name in his engineering career and Nevil Shute as his pen name to protect his enginee ...

's novel '' In the Wet'' (1952), Paul Gallico

Paul William Gallico (July 26, 1897 – July 15, 1976) was an American novelist and short story and sports writer.Ivins, Molly,, ''The New York Times'', July 17, 1976. Retrieved Oct. 25, 2020. Many of his works were adapted for motion pictures. ...

's novel ''Mrs. 'Arris Goes to Moscow'' (1974), Tom Clancy

Thomas Leo Clancy Jr. (April 12, 1947 – October 1, 2013) was an American novelist. He is best known for his technically detailed espionage and military science, military-science storylines set during and after the Cold War. Seventeen of ...

's novel ''Patriot Games

''Patriot Games'' is a thriller novel, written by Tom Clancy and published in July 1987. '' Without Remorse'', released six years later, is an indirect prequel, and it is chronologically the first book featuring Jack Ryan, the main character ...

'' (1987), and Sue Townsend

Susan Lillian Townsend (; 2 April 194610 April 2014) was an English writer and humorist whose work encompasses novels, plays and works of journalism. She was best known for creating the character Adrian Mole.

After writing in secret from the a ...

's novel '' The Queen and I'' (1992).

Books

Philip authored: * ''Selected Speeches – 1948–55'' (1957; revised paperback edition published byNabu Press

BiblioBazaar is, with Nabu Press, an imprint of the historical reprints publisher BiblioLife, which is based in Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the List of municipalities in South Carolina, most populous city in the U.S. state of ...

, 2011),

* ''Selected Speeches – 1956–59'' (1960)

* ''Birds from Britannia'' (1962; published in the United States as ''Seabirds from Southern Waters''),

* ''Wildlife Crisis'' with James Fisher (1970),

* ''The Environmental Revolution: Speeches on Conservation, 1962–1977'' (1978),

* ''Competition Carriage Driving'' (1982; published in France, 1984; second edition, 1984; revised edition, 1994),

* ''A Question of Balance'' (1982),

* '' Men, Machines and Sacred Cows'' (1984),

* ''A Windsor Correspondence'' with Michael Mann

Michael Kenneth Mann (born February 5, 1943) is an American film director, screenwriter, author and producer, best known for his stylized crime dramas. He has received a BAFTA Award and two Primetime Emmy Awards as well as nominations for four ...

(1984),

* ''Down to Earth: Collected Writings and Speeches on Man and the Natural World 1961–87'' (1988; paperback edition, 1989; Japanese edition, 1992),

* ''Survival or Extinction: A Christian Attitude to the Environment'' with Michael Mann (1989),

* ''Driving and Judging Dressage'' (1996),

* ''30 Years On, and Off, the Box Seat'' (2004),

Forewords to:

* ''Royal Australian Navy 1911–1961 Jubilee Souvenir'' issued by authority of the Department of the Navy, Canberra (1961)

* ''The Concise British Flora in Colour'' by William Keble Martin, Ebury Press

Ebury Publishing is a division of Penguin Random House, and is a publisher of general non-fiction books in the UK. Ebury was founded in 1961 as a division of Nat Mags and was originally located on Ebury Street in London. It was sold to Centu ...

/ Michael Joseph (1965)

* ''Birds of Town and Village'' by William Donald Campbell and Basil Ede

Basil Ede (12 February 1931—29 September 2016) was an English wildlife artist specialising in avian portraiture, noted for the ornithological precision of his paintings.

Early life

Basil Ede was born 12 February 1931 in Surrey. Ede's inter ...

(1965)

* ''Kurt Hahn'' by Hermann Röhrs and Hilary Tunstall-Behrens (1970)

* ''The Doomsday Book of Animals'' by David Day (1981)

* ''Saving the Animals: The World Wildlife Fund Book of Conservation'' by Bernard Stonehouse (1981)

* ''The Art of Driving'' by Max Pape (1982),

* ''Yachting and the Royal Prince Alfred Yacht Club'' by Graeme Norman (1988),

* ''National Maritime Museum

The National Maritime Museum (NMM) is a maritime museum in Greenwich, London. It is part of Royal Museums Greenwich, a network of museums in the Maritime Greenwich World Heritage Site. Like other publicly funded national museums in the Unit ...

Guide to Maritime Britain'' by Keith Wheatley (2000)

* ''The Royal Yacht Britannia: The Official History'' by Richard Johnstone-Bryden, Conway Maritime Press

Conway Publishing, formerly Conway Maritime Press, is an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing. It is best known for its publications dealing with nautical subjects.

History

Conway Maritime Press was founded in 1972 as an independent publisher. Its or ...

(2003),

* ''1953: The Crowning Year of Sport'' by Jonathan Rice (2003)

* ''British Flags and Emblems'' by Graham Bartram

The Flag Institute is a membership organisation and UK-registered educational charity devoted to the study and promotion of flags and flag flying. It documents flags in the UK and around the world, maintains a UK Flag Registry, and offers advic ...

, Tuckwell Press (2004),

* ''Chariots of War'' by Robert Hobson, Ulric Publication (2004),

* ''RMS Queen Mary 2 Manual: An Insight into the Design, Construction and Operation of the World's Largest Ocean Liner'' by Stephen Payne, Haynes Publishing (2014)

* ''The Triumph of a Great Tradition: The Story of Cunard's 175 Years'' by Eric Flounders and Michael Gallagher, Lily Publications (2014),

Titles, styles, honours, and arms

Philip held many titles throughout his life. Originally holding the title and style of aprince of Greece and Denmark

This is a list of Greek princes from the accession of George I of the House of Glücksburg to the throne of the Kingdom of Greece in 1863. Individuals holding the title of prince will usually also be styled "His Royal Highness" (HRH). The wife o ...

, Philip abandoned these royal titles before he married and was thereafter created a British duke, among other noble titles. Elizabeth formally issued letters patent in 1957 making him a British prince

Prince of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is a royal title normally granted to sons and grandsons of reigning and past British monarchs, plus consorts of female monarchs (by letters patent). The title is granted by the ...

.

Honours and honorary military appointments

Philip was awarded medals from Britain, France, and Greece for his service during the Second World War, as well as ones commemorating the coronations of George VI and Elizabeth II and the silver, gold and diamond jubilees of Elizabeth. George VI appointed him to theOrder of the Garter

The Most Noble Order of the Garter is an order of chivalry founded by Edward III of England in 1348. The most senior order of knighthood in the Orders, decorations, and medals of the United Kingdom, British honours system, it is outranked in ...

on the eve of his wedding on 19 November 1947. Since then, Philip received 17 appointments and decorations in the Commonwealth and 48 from foreign states. The inhabitants of some villages on the island of Tanna, Vanuatu, worship Philip as a god-like spiritual figure; the islanders possess portraits of him and hold feasts on his birthday.

Upon his wife's accession to the throne in 1952, Philip was appointed Admiral of the Sea Cadet Corps, Colonel-in-Chief of the British

Upon his wife's accession to the throne in 1952, Philip was appointed Admiral of the Sea Cadet Corps, Colonel-in-Chief of the British Army Cadet Force

The Army Cadet Force (ACF), generally shortened to Army Cadets, is a national Youth organisations in the United Kingdom, youth organisation sponsored by the United Kingdom's Ministry of Defence (United Kingdom), Ministry of Defence and the Bri ...

, and Air Commodore-in-Chief of the Air Training Corps

The Air Training Corps (ATC) is a British Youth organisations in the United Kingdom, volunteer youth organisation; aligned to, and fostering the knowledge and learning of military values, primarily focusing on military aviation. Part of the ...

. The following year, he was appointed to the equivalent positions in Canada and made Admiral of the Fleet

An admiral of the fleet or shortened to fleet admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, usually equivalent to field marshal and marshal of the air force. An admiral of the fleet is typically senior to an admiral.

It is also a generic ter ...

, Captain General Royal Marines

Captain General Royal Marines is the ceremonial head of the Royal Marines. The current Captain General is King Charles III. The uniform and insignia currently worn by the Captain General are those of a Field Marshal.

This position is distinct ...

, Field marshal (United Kingdom), Field Marshal, and Marshal of the Royal Air Force in the United Kingdom. Subsequent military appointments were made in New Zealand and Australia. In 1975 he was appointed Colonel (United Kingdom), colonel of the Grenadier Guards, a position he handed over to his son Andrew in 2017. On 16 December 2015, he relinquished his role as Honorary Air Commodore-in-Chief and was succeeded by his granddaughter-in-law Catherine, then Duchess of Cambridge, as Honorary Air Commandant.

To celebrate Philip's 90th birthday, Elizabeth appointed him Lord High Admiral, as well as to the highest ranks available in all three branches of the Canadian Armed Forces. On their 70th wedding anniversary, 20 November 2017, she appointed him Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order, making him the first British national since his uncle Lord Mountbatten of Burma to be entitled to wear the breast stars of four orders of chivalry in the United Kingdom.

Arms

Issue

Ancestry

Notes

References

Citations

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

The Duke of Edinburgh

at the Royal Family website

Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh

at the website of the

Royal Collection Trust

The Royal Collection of the British royal family is the largest private art collection in the world.

Spread among 13 occupied and historic royal residences in the United Kingdom, the collection is owned by King Charles III and overseen by the ...

The Duke of Edinburgh's Award

Obituary

at BBC News Online * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Philip Of Edinburgh, Duke, Prince Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, 1921 births 2021 deaths 20th-century British male writers 20th-century British writers 21st-century British male writers 21st-century British writers Alumni of Schule Schloss Salem Barons Greenwich Battenberg family British Anglicans British environmentalists British field marshals British people of Danish descent British people of German descent British people of Russian descent British princes British royal consorts Burials at St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle Chancellors of the University of Cambridge Chancellors of the University of Edinburgh Chancellors of the University of Salford Chartered designers Deified men Dragon class sailors Dukes created by George VI Dukes of Edinburgh Earls of Merioneth, 1 English polo players Exiled royalty Fellows of the Royal Society (Statute 12) Field marshals of Australia Freemasons of the United Grand Lodge of England Graduates of Britannia Royal Naval College Greek emigrants to the United Kingdom Hereditary peers removed under the House of Lords Act 1999, Edinburgh Honorary Fellows of the Royal Microscopical Society House of Glücksburg (Greece) House of Windsor Lord high admirals of the United Kingdom Lords of the Admiralty Marshals of the Royal Air Force Members of Trinity House Members of the King's Privy Council for Canada Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Monarchy of Australia Monarchy of Canada Monarchy of New Zealand National Council of Social Service presidents Naturalised citizens of the United Kingdom Nobility from Corfu People educated at Cheam School People educated at Gordonstoun Presidents of the Football Association Presidents of the Marylebone Cricket Club Presidents of the Smeatonian Society of Civil Engineers Presidents of the Zoological Society of London Princes of Denmark Princes of Greece Recipients of the Croix de Guerre 1939–1945 (France) Royal Australian Air Force air marshals Royal Canadian Regiment Royal Marines generals Royal Navy admirals of the fleet Royal Navy officers of World War II Royal reburials Vanuatu deities