Potemkin village on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In politics and economics, a Potemkin village (russian: link=no, потёмкинские деревни, translit=potyómkinskiye derévni}) is any construction (literal or figurative) whose sole purpose is to provide an external façade to a country that is faring poorly, making people believe that the country is faring better. The term comes from stories of a fake portable village built by

Grigory Potemkin

Prince Grigory Aleksandrovich Potemkin-Tauricheski (, also , ;, rus, Князь Григо́рий Алекса́ндрович Потёмкин-Таври́ческий, Knjaz' Grigórij Aleksándrovich Potjómkin-Tavrícheskij, ɡrʲɪˈɡ ...

, former lover of Empress Catherine II

, en, Catherine Alexeievna Romanova, link=yes

, house =

, father = Christian August, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst

, mother = Joanna Elisabeth of Holstein-Gottorp

, birth_date =

, birth_name = Princess Sophie of Anha ...

, solely to impress the Empress during her journey to Crimea in 1787. Modern historians agree that accounts of this portable village are exaggerated. The original story was that Potemkin erected phony portable settlements along the banks of the Dnipro River

}

The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine and ...

in order to impress the Russian Empress and foreign guests. The structures would be disassembled after she passed, and re-assembled farther along her route to be viewed again as if another example.

Origin

Grigory Potemkin

Prince Grigory Aleksandrovich Potemkin-Tauricheski (, also , ;, rus, Князь Григо́рий Алекса́ндрович Потёмкин-Таври́ческий, Knjaz' Grigórij Aleksándrovich Potjómkin-Tavrícheskij, ɡrʲɪˈɡ ...

was a minister and lover of the Russian Empress Catherine II

, en, Catherine Alexeievna Romanova, link=yes

, house =

, father = Christian August, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst

, mother = Joanna Elisabeth of Holstein-Gottorp

, birth_date =

, birth_name = Princess Sophie of Anha ...

. After the 1783 Russian annexation of Crimea from the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

and liquidation of the Cossack Zaporozhian Sich (see New Russia), Potemkin became governor of the region. Crimea had been devastated by the war, and the Muslim Tatar

The Tatars ()Tatar

in the Collins English Dictionary is an umbrella term for different inhabitants of Crimea were viewed as a potential

In the

In the

Potemkin Court

as a description of The

Potemkin Parliament

as a description of the

New York Review of Books, "An Affair to Remember"

review by Simon Sebag Montefiore of Douglas Smith, ''Love and Conquest: Personal Correspondence of Catherine the Great and Prince Grigory Potemkin''

{{Disinformation Hoaxes in Russia Fictitious entries 1787 in the Russian Empire Propaganda techniques Propaganda Deception

in the Collins English Dictionary is an umbrella term for different inhabitants of Crimea were viewed as a potential

fifth column

A fifth column is any group of people who undermine a larger group or nation from within, usually in favor of an enemy group or another nation. According to Harris Mylonas and Scott Radnitz, "fifth columns" are “domestic actors who work to un ...

of the Ottoman Empire. Potemkin's major tasks were to pacify and rebuild by bringing in Russian settlers. In 1787, as a new war was about to break out between Russia and the Ottoman Empire, Catherine II, with her court and several ambassadors, made an unprecedented six-month trip to New Russia. One purpose of this trip was to impress Russia's allies prior to the war. To help accomplish this, Potemkin was said to have set up "mobile villages" on the banks of the Dnipro River

}

The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine and ...

. As soon as the barge carrying the Empress and ambassadors arrived, Potemkin's men, dressed as peasants, would populate the village. Once the barge left, the village was disassembled, then rebuilt downstream overnight.

Historical accuracy

According to Simon Sebag-Montefiore, Potemkin's most comprehensive English-language biographer, the tale of elaborate, fake settlements, with glowing fires designed to comfort the monarch and her entourage as they surveyed the barren territory at night, is largely fictional. Aleksandr Panchenko, an established specialist on 19th-century Russia, used original correspondence and memoirs to conclude that the Potemkin villages are a myth. He writes: "Based on the above said we must conclude that the myth of 'Potemkin villages' is exactly a myth, and not an established fact." He writes that "Potyomkin indeed decorated existing cities and villages, but made no secret that this was a decoration". The close relationship between Potemkin and the empress could have made it difficult for him to deceive her. Thus, if there were deception, it would have been mainly directed towards the foreign ambassadors accompanying the imperial party. Although "Potemkin village" has come to mean, especially in a political context, any hollow or false construct, physical or figurative, meant to hide an undesirable or potentially damaging situation, it is possible that the phrase cannot be applied accurately to its own original historical inspiration. According to some historians, some of the buildings were real, and others were constructed to show what the region would look like in the near future, and at least Catherine and possibly also her foreign visitors knew which were which. According to these historians, the claims of deception were part of a defamation campaign against Potemkin. According to a legend, in 1787, when Catherine passed through Tula on her way back from the trip, the local governor Mikhail Krechetnikov attempted a deception of that kind in order to hide the effects of a bad harvest.Modern usage

Physical examples

*North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korean Peninsula and shares borders with China and Russia to the north, at the Yalu (Amnok) and ...

has a Potemkin village called Kijong-dong

Kijŏng-dong, Kijŏngdong, or Kijŏng tong is a Potemkin village in P'yŏnghwa-ri (), Kaesong, North Korea. It is situated in the North's half of the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). Also known in North Korea as ''Peace Village'' (),Demilitarized Zone

A demilitarized zone (DMZ or DZ) is an area in which treaties or agreements between nations, military powers or contending groups forbid military installations, activities, or personnel. A DZ often lies along an established frontier or bounda ...

, also known as the "Peace Village".

* The Nazi German

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

Theresienstadt concentration camp

Theresienstadt Ghetto was established by the SS during World War II in the fortress town of Terezín, in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia ( German-occupied Czechoslovakia). Theresienstadt served as a waystation to the extermination camp ...

, called "the Paradise Ghetto" in World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, was designed as a concentration camp that could be shown to the Red Cross

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a Humanitarianism, humanitarian movement with approximately 97 million Volunteering, volunteers, members and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ensure re ...

but was really a Potemkin village: attractive at first, but deceptive and ultimately lethal, with high death rates from malnutrition and contagious diseases. It ultimately served as a way-station to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

* Henry A. Wallace

Henry Agard Wallace (October 7, 1888 – November 18, 1965) was an American politician, journalist, farmer, and businessman who served as the 33rd vice president of the United States, the 11th U.S. Secretary of Agriculture, and the 10th U.S. S ...

, then Vice President

A vice president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vice president is o ...

of the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., federal district, five ma ...

, visited a Soviet penal labor camp in Magadan

Magadan ( rus, Магадан, p=məɡɐˈdan) is a port town and the administrative center of Magadan Oblast, Russia, located on the Sea of Okhotsk in Nagayev Bay (within Taui Bay) and serving as a gateway to the Kolyma region.

History

Ma ...

in 1944 and believed that the prisoners were "volunteers".

* In 1998, the energy services company Enron

Enron Corporation was an American energy, commodities, and services company based in Houston, Texas. It was founded by Kenneth Lay in 1985 as a merger between Lay's Houston Natural Gas and InterNorth, both relatively small regional compani ...

built and maintained a fake trading floor on the sixth story of its headquarters in downtown Houston

Houston (; ) is the List of cities in Texas by population, most populous city in Texas, the Southern United States#Major cities, most populous city in the Southern United States, the List of United States cities by population, fourth-most pop ...

. The trading floor was used to impress Wall Street

Wall Street is an eight-block-long street in the Financial District of Lower Manhattan in New York City. It runs between Broadway in the west to South Street and the East River in the east. The term "Wall Street" has become a metonym for ...

analysts attending Enron's annual shareholders meeting and even included rehearsals conducted by Enron executives Kenneth Lay

Kenneth Lee Lay (April 15, 1942 – July 5, 2006) was an American businessman who was the founder, chief executive officer and chairman of Enron. He was heavily involved in the eponymous accounting scandal that unraveled in 2001 into the larg ...

and Jeffrey Skilling

Jeffrey Keith Skilling (born November 25, 1953) is an American businessman who is best known as the CEO of Enron Corporation during the Enron scandal. In 2006, he was convicted of federal felony charges relating to Enron's collapse and eventua ...

.

* Venezuela

Venezuela (; ), officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela ( es, link=no, República Bolivariana de Venezuela), is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many islands and islets in ...

n President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese f ...

Hugo Chávez

Hugo Rafael Chávez Frías (; 28 July 1954 – 5 March 2013) was a Venezuelan politician who was president of Venezuela from 1999 until his death in 2013, except for a brief period in 2002. Chávez was also leader of the Fifth Repub ...

fixed up routes that would be visited by foreign dignitaries in his country's capital, Caracas

Caracas (, ), officially Santiago de León de Caracas, abbreviated as CCS, is the capital and largest city of Venezuela, and the center of the Metropolitan Region of Caracas (or Greater Caracas). Caracas is located along the Guaire River in the ...

. Workers placed new paint on the streets and painted rocks and other fragments that were inside of pothole

A pothole is a depression in a road surface, usually asphalt pavement, where traffic has removed broken pieces of the pavement. It is usually the result of water in the underlying soil structure and traffic passing over the affected area. Wat ...

s.

* In 2010, 22 vacant houses in a blighted part of Cleveland

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along the southern shore of Lake Erie, across the U ...

, Ohio, US, were disguised with fake doors and windows painted on the plywood panels used to close them up, so the houses looked occupied. Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

and Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state lin ...

have initiated similar programs.

* In preparation for hosting the July 2013 G8 summit in Enniskillen

Enniskillen ( , from ga, Inis Ceithleann , ' Ceithlenn's island') is the largest town in County Fermanagh, Northern Ireland. It is in the middle of the county, between the Upper and Lower sections of Lough Erne. It had a population of 13,823 ...

, Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label=Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. North ...

, large photographs were put up in the windows of closed shops in the town so as to give the appearance of thriving businesses for visitors driving past them.

* In 2013, before Vladimir Putin

Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin; (born 7 October 1952) is a Russian politician and former intelligence officer who holds the office of president of Russia. Putin has served continuously as president or prime minister since 1999: as prime m ...

's visit to Suzdal

Suzdal ( rus, Суздаль, p=ˈsuzdəlʲ) is a town that serves as the administrative center of Suzdalsky District in Vladimir Oblast, Russia, which is located on the Kamenka River, north of the city of Vladimir. Vladimir is the ...

, some old and half-ruined houses in the city center were covered with large posters with doors and windows printed on them.

*In 2016, the government of Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan ( or ; tk, Türkmenistan / Түркменистан, ) is a country located in Central Asia, bordered by Kazakhstan to the northwest, Uzbekistan to the north, east and northeast, Afghanistan to the southeast, Iran to the s ...

built and opened a village called Berkarar Zaman, but abandoned it soon after opening.

*In 2016, Russian military contractors at the Kantemirovskaya Tank Division in Naro-Forminsk, Moscow are said to have hastily constructed facades and hung banners concealing the poor condition of the base prior to a visit from government officials.

Metaphorical usage

* In the 2018 lawsuit filed againstExxon

ExxonMobil Corporation (commonly shortened to Exxon) is an American multinational oil and gas corporation headquartered in Irving, Texas. It is the largest direct descendant of John D. Rockefeller's Standard Oil, and was formed on November ...

for the fraud relating to the discrepancy between the published cost of climate regulation and the internally calculated costs, New York Attorney General Underwood's complaint alleged, "Through its fraudulent scheme, Exxon in effect erected a Potemkin village to create the illusion that it had fully considered the risks of future climate change regulation and had factored those risks into its business operations."

* During the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, the UK government set a target of 100,000 daily tests before the end of April 2020. On 30 April 2020, Matt Hancock

Matthew John David Hancock (born 2 October 1978) is a British politician who served as Minister for the Cabinet Office and Paymaster General from 2015 to 2016, Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport from January to July 201 ...

, the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care

The secretary of state for health and social care, also referred to as the health secretary, is a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, responsible for the work of the Department of Health and Social Care. The incumbent ...

, declared the target to have been met. This claim was widely disputed when it emerged that the government "changed the way it counts the number of COVID-19 tests"; some 40,000 of the total were home-test kits which had been sent out by mail, but not yet completed. The government's misleading claims were later challenged by the UK Statistics Authority

The UK Statistics Authority (UKSA, cy, Awdurdod Ystadegau'r DU) is a non-ministerial government department of the Government of the United Kingdom responsible for oversight of the Office for National Statistics, maintaining a national code of p ...

, and described as a "Potemkin testing regime" by Aditya Chakrabortty in an opinion piece for ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper

A newspaper is a periodical publication containing written information about current events and is often typed in black ink with a white or gray background.

Newspapers can cover a wide ...

''.

* On 6 March 2022, two weeks into the Russian invasion of Ukraine

On 24 February 2022, in a major escalation of the Russo-Ukrainian War, which began in 2014. The invasion has resulted in tens of thousands of deaths on both sides. It has caused Europe's largest refugee crisis since World War II. ...

, former Russian foreign minister Andrei Kozyrev described the Russian armed forces as a "Potemkin military" in a Twitter post, in light of its logistics troubles and failure to progress on its objectives. He explained that "The Kremlin spent the last 20 years trying to modernize its military. Much of that budget was stolen and spent on mega-yachts in Cyprus. But as a military advisor you cannot report that to the President. So they reported lies to him instead."

* On 24 March 2022, a statement from a White House official referred to the reopening of the Moscow stock exchange as a "Potemkin market opening" due to the significant limits Russian authorities imposed on trading, including a ban on shorting stocks and a ban on foreigners selling stocks.

In the United States legal system

"Potemkin village" is a phrase that has been used by American judges, especially members of a multiple-judge panel who dissent from the majority's opinion on a particular matter, to refer to an inaccurate or tortured interpretation and/or application of a particularlegal doctrine

A legal doctrine is a framework, set of rules, procedural steps, or test, often established through precedent in the common law, through which judgments can be determined in a given legal case. A doctrine comes about when a judge makes a ruling ...

to the specific facts at issue. Use of the phrase is meant to imply that the reasons espoused by the panel's majority in support of its decision are not based on accurate or sound law, and their restrictive application is merely a masquerade for the court's desire to avoid a difficult decision. For example, in '' Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey'' (1992), chief justice of the United States William Rehnquist

William Hubbs Rehnquist ( ; October 1, 1924 – September 3, 2005) was an American attorney and jurist who served on the U.S. Supreme Court for 33 years, first as an associate justice from 1972 to 1986 and then as the 16th chief justice from ...

wrote that '' Roe v. Wade'' "stands as a sort of judicial Potemkin Village, which may be pointed out to passers-by as a monument to the importance of adhering to precedent". Similarly, Judge William G. Young

William Glover Young (born September 23, 1940) is a Senior United States district judge of the United States District Court for the District of Massachusetts.

Education and career

Born in Huntington, New York, Young received an Artium Baccalau ...

of the District of Massachusetts described the use of affidavits in U.S. litigation as "the Potemkin Village of today’s litigation landscape" because "adjudication by affidavit is like walking down a street between two movie sets, all lawyer-painted façade and no interior architecture."''United States v. Massachusetts'', , 22 n.25 (D.Mass 2011).

Other uses

Sometimes, instead of the full phrase, just "Potemkin" is used, as an adjective. For example, the use of a row of trees to screen a clearcut area from motorists has been called a "Potemkin forest". For example, the glossary entry for "clearcut" in ''We Have The Right To Exist: A Translation of Aboriginal Indigenous Thought'' states that "Much of the extensive clearcut in northern Minnesota is insulated from scrutiny by the urbanized public by a Potemkin forest, or, as the D.N.R. terms it, an aesthetic strip – a thin illusion of forest about six trees deep, along most highways and fronting waters frequented by tourists." Another example is the phrase "Potemkin court", which implies that the court's reason to exist is being called into question (differing from the phrase "kangaroo court

A kangaroo court is a court that ignores recognized standards of law or justice, carries little or no official standing in the territory within which it resides, and is typically convened ad hoc. A kangaroo court may ignore due process and come ...

" with which the court's standard of justice is being impugned).

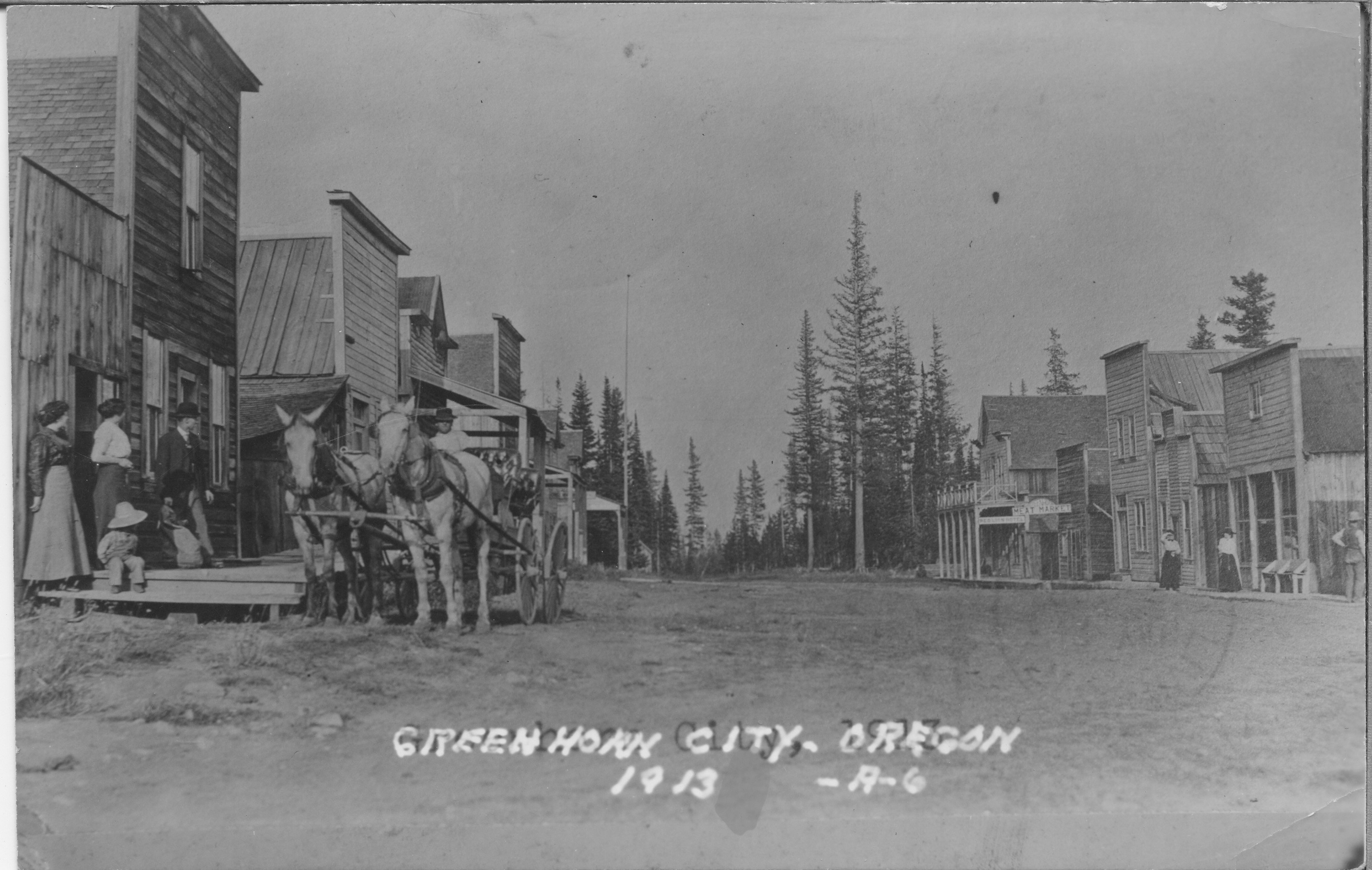

Old West

The American frontier, also known as the Old West or the Wild West, encompasses the geography, history, folklore, and culture associated with the forward wave of American expansion in mainland North America that began with European colonial ...

of the United States, Western false front architecture was often used to create the illusion of affluence and stability in a new frontier town. The style included a tall vertical facade with a square top in front of a wood-framed building, often hiding a gable roof. The goal for the architecture was to project an image of stability and success for the town, while the business owners did not invest much in buildings that might be temporary. These towns often did not last long before becoming ghost town

Ghost Town(s) or Ghosttown may refer to:

* Ghost town, a town that has been abandoned

Film and television

* ''Ghost Town'' (1936 film), an American Western film by Harry L. Fraser

* ''Ghost Town'' (1956 film), an American Western film by All ...

s, so businessmen wanted to get started quickly but did not want to spend a lot on their stores. Many Western movies

The Western is a genre set in the American frontier and commonly associated with folk tales of the Western United States, particularly the Southwestern United States, as well as Northern Mexico and Western Canada. It is commonly referre ...

feature this kind of architecture because, just like the original buildings, it is quick and cheap to create.

Many of the newly constructed base areas at ski resorts are referred to as Potemkin villages. These create the illusion of a quaint mountain town, but are actually carefully planned theme shopping centers, hotels and restaurants designed for maximum revenue. Similarly, in ''The Geography of Nowhere'', American writer James Howard Kunstler refers to contemporary suburban shopping centers as "Potemkin village shopping plazas".

Hardcore punk

Hardcore punk (also known as simply hardcore) is a punk rock music genre and subculture that originated in the late 1970s. It is generally faster, harder, and more aggressive than other forms of punk rock. Its roots can be traced to earlier pu ...

band Propagandhi released an album in 2005 called ''Potemkin City Limits

''Potemkin City Limits'' is the fourth full-length album by the Canadian punk rock band Propagandhi, released on October 18, 2005 through G7 Welcoming Committee Records in Canada, and Fat Wreck Chords elsewhere. It is the second Propagandhi rele ...

''. The cover depicts children playing in a city that is drawn on the ground, a façade city. Their 2009 album '' Supporting Caste'' has a song called "Potemkin City Limits", about the statue of Francis the Pig in Red Deer, Alberta, Canada.

Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who served as the 45th president of the United States from 2017 to 2021.

Trump graduated from the Wharton School of the University of ...

's business councils have been described as Potemkin Villages after several high-profile CEO participants resigned in August 2017. Trump's ''The Art of the Deal

''Trump: The Art of the Deal'' is a 1987 book credited to Donald J. Trump and journalist Tony Schwartz. Part memoir and part business-advice book, it was the first book credited to Trump, and helped to make him a household name. It reached n ...

'' describes a stunt in which he lured Holiday Inn

Holiday Inn is an American chain of hotels based in Atlanta, Georgia. and a brand of IHG Hotels & Resorts. The chain was founded in 1952 by Kemmons Wilson, who opened the first location in Memphis, Tennessee that year. The chain was a divisio ...

executives into investing in an Atlantic City, New Jersey

Atlantic City, often known by its initials A.C., is a coastal resort city in Atlantic County, New Jersey, United States. The city is known for its casinos, Boardwalk (entertainment district), boardwalk, and beaches. In 2020 United States censu ...

, casino by directing his construction manager to rent dozens of pieces of heavy equipment, in advance of a visit by the executives, to move dirt around on the proposed casino site, creating the illusion that construction was under way.

See also

* ''Theresienstadt'' (1944 film) * '' Czech Dream'' * Disneyfication *Potemkin Island

Ostriv Velykyi Potomkin (), also known as Ostrov Bol’shoy Potëmkin () and Potemkin Island, is a river island located within the Dnipro river in the of Kherson Raion of Kherson oblast of Ukraine.

Geography

Ostriv Velykyi Potomkin is loc ...

* '' The Truman Show''

* Legends of Catherine the Great

* Novorossiya

Novorossiya, literally "New Russia", is a historical name, used during the era of the Russian Empire for an administrative area that would later become the southern mainland of Ukraine: the region immediately north of the Black Sea and Crimea. ...

, New Russia, historical region in the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the List of Russian monarchs, Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended th ...

* Folly

In architecture, a folly is a building constructed primarily for decoration, but suggesting through its appearance some other purpose, or of such extravagant appearance that it transcends the range of usual garden buildings.

Eighteenth-cent ...

, architecture vernacular

* Façadism

* Sportswashing

* Kijong-dong

Kijŏng-dong, Kijŏngdong, or Kijŏng tong is a Potemkin village in P'yŏnghwa-ri (), Kaesong, North Korea. It is situated in the North's half of the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). Also known in North Korea as ''Peace Village'' (),Ivan Katchanovski

Ivan Katchanovski, ua, Іван Гнатович Качановський (born 1967) is a Ukrainian and Canadian political scientist based in Ottawa, teaches at the School of Political Studies at the University of Ottawa. He specializes in re ...

and La Porte, Todd. "Cyberdemocracy or Potemkin E-Villages? Electronic Governments in OECD and Post-Communist Countries," ''International Journal of Public Administration'', Volume 28, Number 7–8, July 2005.

* Ledeen, Michael. "Potemkin WMDs? Really?", ''National Review'', 2 February 2004

* Smith, Douglas (ed. and trans). ''Love and Conquest: Personal Correspondence of Catherine the Great and Prince Grigory Potemkin''

Potemkin Court

as a description of The

Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court

The United States Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC), also called the FISA Court, is a U.S. federal court established under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 (FISA) to oversee requests for surveillance warrants ag ...

(from the Washington Post)

Potemkin Parliament

as a description of the

European Parliament

The European Parliament (EP) is one of the legislative bodies of the European Union and one of its seven institutions. Together with the Council of the European Union (known as the Council and informally as the Council of Ministers), it adop ...

(''New Statesman'', 20 September 2004)

* Sullivan, Kevin. "Borderline Absurdity", ''Washington Post, 11 January 1998.

* Buchan, James. "Potemkin democracy" as a description of Russia. "New Statesman", 17 July 2006.

External links

New York Review of Books, "An Affair to Remember"

review by Simon Sebag Montefiore of Douglas Smith, ''Love and Conquest: Personal Correspondence of Catherine the Great and Prince Grigory Potemkin''

{{Disinformation Hoaxes in Russia Fictitious entries 1787 in the Russian Empire Propaganda techniques Propaganda Deception