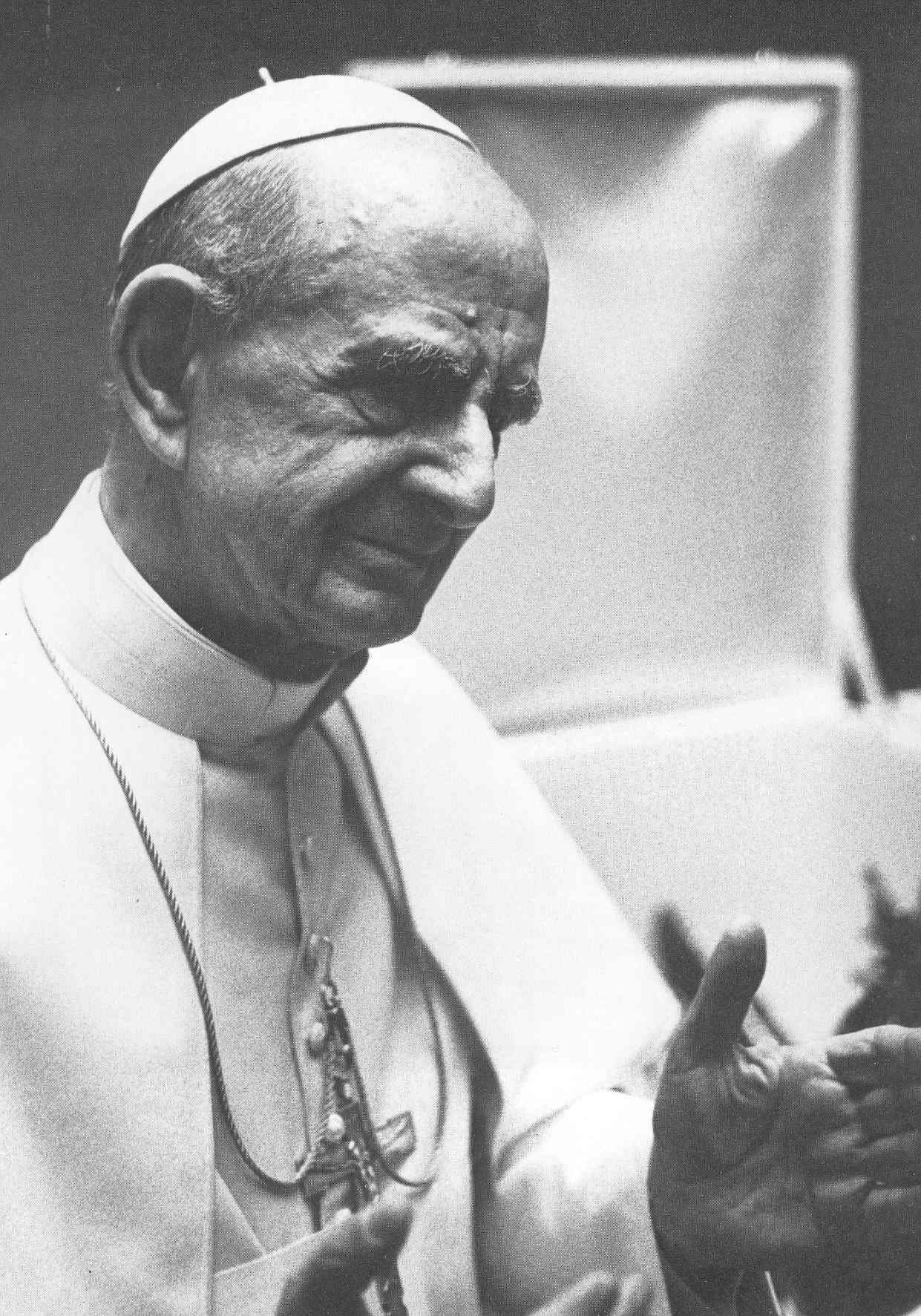

Pope Paul VI (born Giovanni Battista Enrico Antonio Maria Montini; 26 September 18976 August 1978) was head of the

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

and sovereign of the

Vatican City State

Vatican City, officially the Vatican City State (; ), is a Landlocked country, landlocked sovereign state and city-state; it is enclaved within Rome, the capital city of Italy and Bishop of Rome, seat of the Catholic Church. It became inde ...

from 21 June 1963 until his death on 6 August 1978. Succeeding

John XXIII

Pope John XXIII (born Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli; 25 November 18813 June 1963) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 28 October 1958 until his death on 3 June 1963. He is the most recent pope to take ...

, he continued the

Second Vatican Council

The Second Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, commonly known as the or , was the 21st and most recent ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. The council met each autumn from 1962 to 1965 in St. Peter's Basilica in Vatican City for session ...

, which he closed in 1965, implementing its numerous reforms. He fostered improved ecumenical relations with

Eastern Orthodox

Eastern Orthodoxy, otherwise known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity or Byzantine Christianity, is one of the three main Branches of Christianity, branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholic Church, Catholicism and Protestantism ...

and

Protestant churches, which resulted in many historic meetings and agreements. In January 1964,

he flew to Jordan, the first time a reigning pontiff had left Italy in more than a century.

Montini served in the

Holy See's Secretariat of State from 1922 to 1954, and along with

Domenico Tardini was considered the closest and most influential advisor of

Pope Pius XII

Pope Pius XII (; born Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli; 2 March 18769 October 1958) was the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 2 March 1939 until his death on 9 October 1958. He is the most recent p ...

. In 1954, Pius named Montini

Archbishop of Milan, the largest Italian diocese. Montini later became the Secretary of the

Italian Bishops' Conference. John XXIII elevated Montini to the

College of Cardinals

The College of Cardinals (), also called the Sacred College of Cardinals, is the body of all cardinals of the Catholic Church. there are cardinals, of whom are eligible to vote in a conclave to elect a new pope. Appointed by the pope, ...

in 1958, and after his death, Montini was, with little to no opposition, elected his successor, taking the name Paul VI.

He reconvened the Second Vatican Council, which had been suspended during the interregnum. After its conclusion, Paul VI took charge of the interpretation and implementation of its mandates, finely balancing the conflicting expectations of various Catholic groups. The resulting reforms were among the widest and deepest in the Church's history.

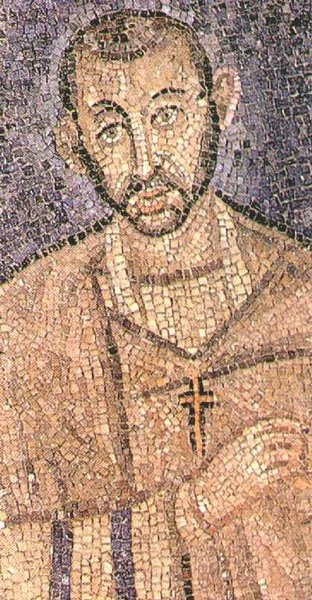

Paul VI spoke repeatedly to Marian conventions and

Mariological meetings, visited Marian shrines and issued three

Marian encyclicals. Following

Ambrose of Milan, he named Mary as the

Mother of the Church

Mother of the Church () is a Titles of Mary, title given to Mary, mother of Jesus, Mary in the Catholic Church, as officially declared by Pope Paul VI in 1964. The title first appeared in the 4th century writings of Saint Ambrose of Milan, as redi ...

during the Second Vatican Council.

He described himself as a humble servant of a suffering humanity and demanded significant changes from the rich in North America and Europe in favour of the poor in the

Third World

The term Third World arose during the Cold War to define countries that remained non-aligned with either NATO or the Warsaw Pact. The United States, Canada, Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, the Southern Cone, NATO, Western European countries and oth ...

. His opposition to

birth control

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth control only be ...

was published in the 1968 encyclical .

Pope Benedict XVI

Pope BenedictXVI (born Joseph Alois Ratzinger; 16 April 1927 – 31 December 2022) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 19 April 2005 until his resignation on 28 February 2013. Benedict's election as p ...

, citing his

heroic virtue

Heroic virtue is the translation of a phrase coined by Augustine of Hippo to describe the virtue of early Christian martyrs. The phrase is used by the Roman Catholic Church.

The Greek pagan term hero described a person with possibly superhuman a ...

, proclaimed him

venerable

''The Venerable'' often shortened to Venerable is a style, title, or epithet used in some Christianity, Christian churches. The title is often accorded to holy persons for their spiritual perfection and wisdom.

Catholic

In the Catholic Churc ...

on 20 December 2012.

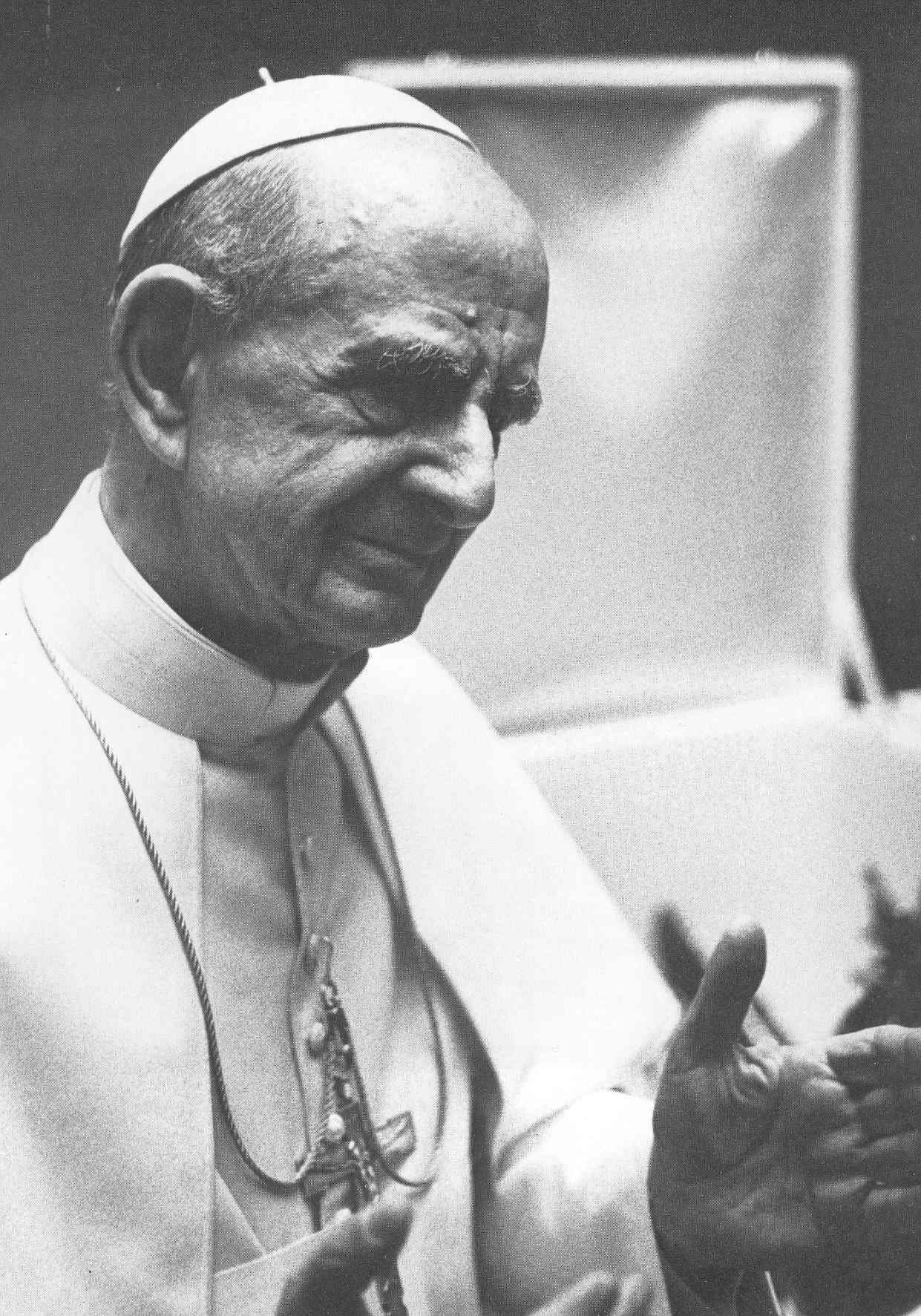

Pope Francis

Pope Francis (born Jorge Mario Bergoglio; 17 December 1936 – 21 April 2025) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 13 March 2013 until Death and funeral of Pope Francis, his death in 2025. He was the fi ...

beatified

Beatification (from Latin , "blessed" and , "to make") is a recognition accorded by the Catholic Church of a deceased person's entrance into Heaven and capacity to intercede on behalf of individuals who pray in their name. ''Beati'' is the ...

Paul VI on 19 October 2014, after the recognition of a miracle attributed to his intercession. His liturgical feast was celebrated on the date of his birth, 26 September, until 2019 when it was changed to the date of his priestly ordination, 29 May.

Pope Francis

canonised

Canonization is the declaration of a deceased person as an officially recognized saint, specifically, the official act of a Christian communion declaring a person worthy of public veneration and entering their name in the canon catalogue of sai ...

him on 14 October 2018. Paul VI is the most recent pope to take the

pontifical name "Paul".

Early life

Giovanni Battista Enrico Antonio Maria Montini was born in the village of

Concesio, in the

Province of Brescia

The province of Brescia (; Brescian: ) is a Provinces of Italy, province in the Lombardy region of Italy. It has a population of some 1,265,964 (as of January 2019) and its capital is the city of Brescia.With an area of 4,785 km2, it is the ...

,

Lombardy

The Lombardy Region (; ) is an administrative regions of Italy, region of Italy that covers ; it is located in northern Italy and has a population of about 10 million people, constituting more than one-sixth of Italy's population. Lombardy is ...

, Italy, in 1897. His father,

Giorgio Montini (1860–1943), was a lawyer, journalist, director of the

Catholic Action

Catholic Action is a movement of Catholic laity, lay people within the Catholic Church which advocates for increased Catholic influence on society. Catholic Action groups were especially active in the nineteenth century in historically Catholic cou ...

, and member of the Italian Parliament. His mother, Giudetta Alghisi (1874–1943), was from a family of rural nobility. He had two brothers, Francesco Montini (1900–1971), who became a physician, and

Lodovico Montini (1896–1990), who became a lawyer and politician. On 30 September 1897, he was baptised with the name Giovanni Battista Enrico Antonio Maria Montini. He attended the Cesare Arici school, run by the

Jesuits

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

, and in 1916 received a diploma from the

Arnaldo da Brescia public school in

Brescia

Brescia (, ; ; or ; ) is a city and (municipality) in the region of Lombardy, in Italy. It is situated at the foot of the Alps, a few kilometers from the lakes Lake Garda, Garda and Lake Iseo, Iseo. With a population of 199,949, it is the se ...

. His education was often interrupted by bouts of illness.

In 1916, he entered the

seminary

A seminary, school of theology, theological college, or divinity school is an educational institution for educating students (sometimes called seminarians) in scripture and theology, generally to prepare them for ordination to serve as cle ...

to become a Catholic priest. He was

ordained

Ordination is the process by which individuals are Consecration in Christianity, consecrated, that is, set apart and elevated from the laity class to the clergy, who are thus then authorized (usually by the religious denomination, denominationa ...

on 29 May 1920 in Brescia and celebrated his first

Mass

Mass is an Intrinsic and extrinsic properties, intrinsic property of a physical body, body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the physical quantity, quantity of matter in a body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physi ...

at the

Santa Maria delle Grazie, Brescia. Montini concluded his studies in

Milan

Milan ( , , ; ) is a city in northern Italy, regional capital of Lombardy, the largest city in Italy by urban area and the List of cities in Italy, second-most-populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of nea ...

with a doctorate in

canon law

Canon law (from , , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical jurisdiction, ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its membe ...

in the same year. He later studied at the

Gregorian University, the

University of Rome La Sapienza

The Sapienza University of Rome (), formally the Università degli Studi di Roma "La Sapienza", abbreviated simply as Sapienza ('Wisdom'), is a Public university, public research university located in Rome, Italy. It was founded in 1303 and is ...

and, at the request of

Giuseppe Pizzardo

Giuseppe Pizzardo (13 July 1877 – 1 August 1970) was an Italian cardinal of the Catholic Church who served as prefect of the Congregation for Seminaries and Universities from 1939 to 1968, and secretary of the Holy Office from 1951 to 195 ...

, the

Pontifical Academy of Ecclesiastical Nobles. In 1922, at the age of twenty-five, again at the request of Giuseppe Pizzardo, Montini entered the

Secretariat of State, where he worked under Pizzardo together with

Francesco Borgongini-Duca,

Alfredo Ottaviani,

Carlo Grano,

Domenico Tardini and

Francis Spellman

Francis Joseph Spellman (May 4, 1889 – December 2, 1967) was an Catholic Church in the United States, American Catholic prelate who served as Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New York, Archbishop of New York from 1939 until his death in 1967. F ...

. Consequently, he never had an appointment as a parish priest. In 1925 he helped found the publishing house Morcelliana in Brescia, focused on promoting a 'Christian-inspired culture'.

Vatican career

Diplomatic service

Montini had just one foreign posting in the diplomatic service of the Holy See as Secretary in the office of the papal

nuncio

An apostolic nuncio (; also known as a papal nuncio or simply as a nuncio) is an ecclesiastical diplomat, serving as an envoy or a permanent diplomatic representative of the Holy See to a state or to an international organization. A nuncio is ...

to

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

in 1923. Of the

nationalism

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation, Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Theory, I ...

he experienced there he wrote: "This form of nationalism treats foreigners as enemies, especially foreigners with whom one has common frontiers. Then one seeks the expansion of one's own country at the expense of the immediate neighbours. People grow up with a feeling of being hemmed in. Peace becomes a transient compromise between wars." He described his experience in Warsaw as "useful, though not always joyful". When he became pope, the

Communist government of Poland refused him permission to visit Poland on a Marian pilgrimage.

Roman Curia

His organisational skills led him to a career in the

Roman Curia

The Roman Curia () comprises the administrative institutions of the Holy See and the central body through which the affairs of the Catholic Church are conducted. The Roman Curia is the institution of which the Roman Pontiff ordinarily makes use ...

, the papal civil service. On 19 October 1925, he was appointed a

papal chamberlain in the rank of Supernumerary Privy Chamberlain of His Holiness. In 1931, Cardinal

Eugenio Pacelli appointed him to teach history at the Pontifical Academy for Diplomats; he was promoted to Domestic Prelate of His Holiness on 8 July of the same year. On 24 September 1936, he was appointed a Referendary Prelate of the Supreme Tribunal of the

Apostolic Signatura.

On 16 December 1937, after his mentor Giuseppe Pizzardo was named a cardinal and was succeeded by

Domenico Tardini, Montini was named Substitute for Ordinary Affairs under Cardinal Pacelli, the Secretary of State. His immediate supervisor was

Domenico Tardini, with whom he got along well. He was further appointed Consultor of the

Supreme Sacred Congregation of the Holy Office and of the

Sacred Consistorial Congregation on 24 December, and was promoted to

Protonotary apostolic (''ad instar participantium''), the most senior class of papal prelate, on 10 May 1938.

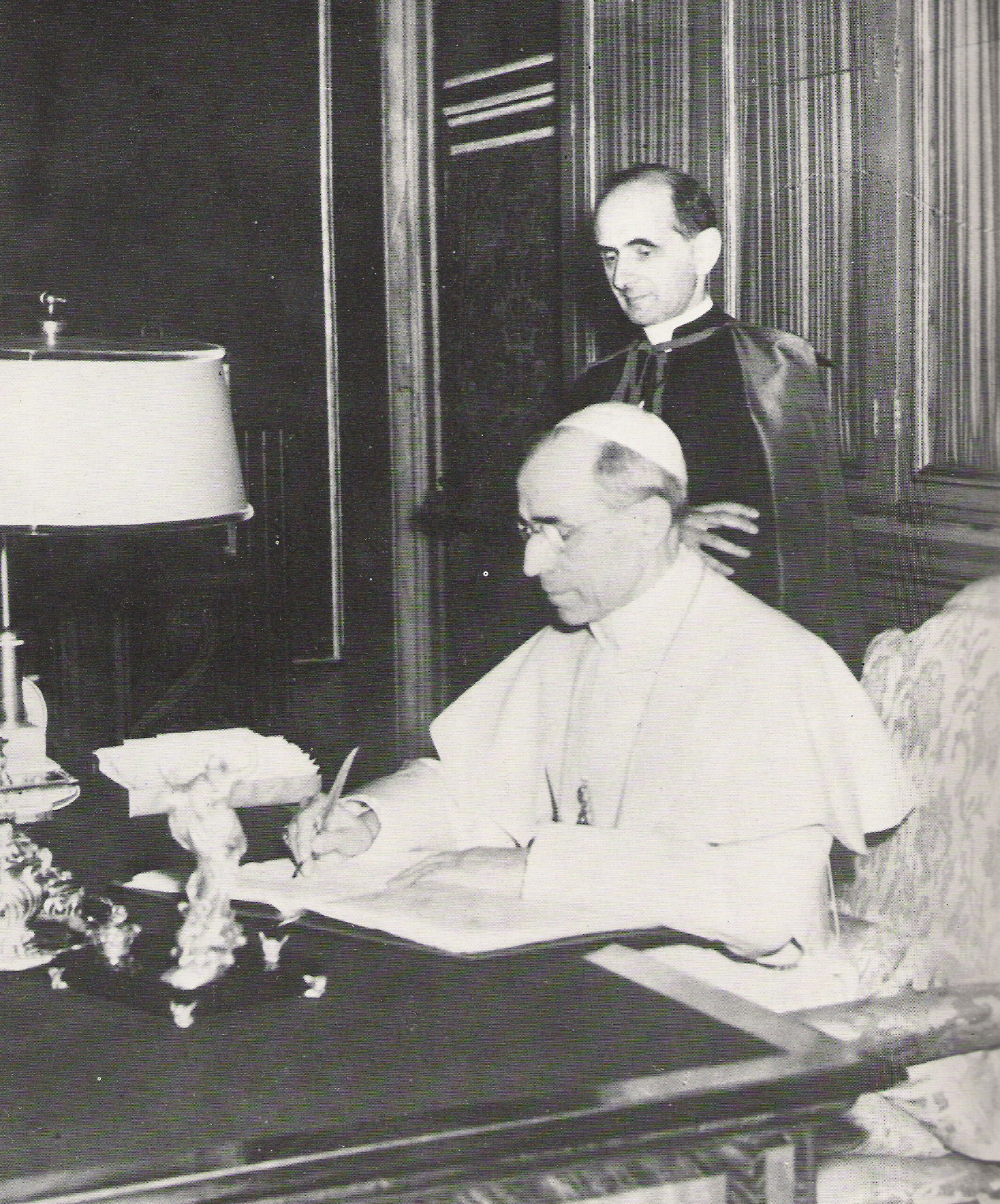

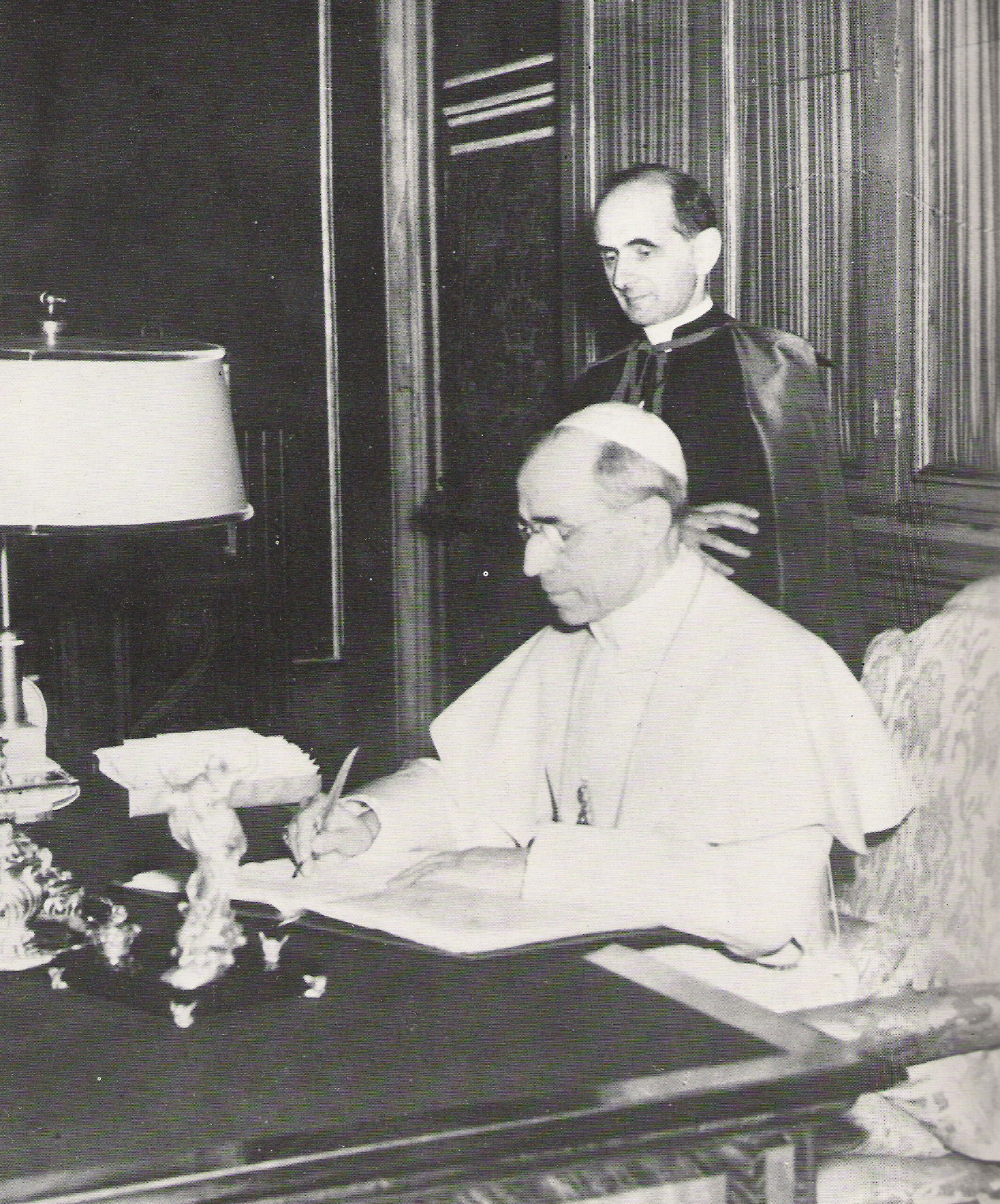

Pacelli became

Pope Pius XII

Pope Pius XII (; born Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli; 2 March 18769 October 1958) was the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 2 March 1939 until his death on 9 October 1958. He is the most recent p ...

in 1939 and confirmed Montini's appointment as Substitute under the new

Cardinal Secretary of State

The Secretary of State of His Holiness (; ), also known as the Cardinal Secretary of State or the Vatican Secretary of State, presides over the Secretariat of State of the Holy See, the oldest and most important dicastery of the Roman Curia. Th ...

Luigi Maglione. In that role, roughly that of a chief of staff, he met the Pope every morning until 1954 and developed a rather close relationship with him. Of his service to two popes he wrote:

When war broke out, Maglione, Tardini, and Montini were the principal figures in the

Secretariat of State of the Holy See. Montini dispatched "ordinary affairs" in the morning, while in the afternoon he moved informally to the third floor Office of the Private Secretary of the Pontiff, serving in place of a personal secretary. During the war years, he replied to thousands of letters from all parts of the world with understanding and prayer, and arranging for help when possible.

At the request of the Pope, Montini created an information office regarding prisoners of war and refugees, which from 1939 to 1947 received almost ten million requests for information about missing persons and produced over eleven million replies. Montini was several times attacked by

Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

's government for meddling in politics, but the Holy See consistently defended him. When Maglione died in 1944, Pius XII appointed Tardini and Montini as joint heads of the Secretariat, each a Pro-Secretary of State. Montini described Pius XII with a filial admiration:

As Pro-Secretary of State, Montini coordinated the activities of assistance to persecuted fugitives hidden in Catholic convents, parishes, seminaries, and schools.

At the Pope's instruction, Montini,

Ferdinando Baldelli, and

Otto Faller established the

Pontificia Commissione di Assistenza (''Pontifical Commission for Assistance''), which supplied a large number of Romans and refugees from everywhere with shelter, food and other necessities. In Rome alone it distributed almost two million portions of free food in 1944. The Papal Residence of

Castel Gandolfo was opened to refugees, as was Vatican City in so far as space allowed. Some 15,000 lived in Castel Gandolfo, supported by the Pontificia Commissione di Assistenza. Montini was also involved in the re-establishment of Church Asylum, extending protection to hundreds of Allied soldiers escaped from prison camps, to Jews, anti-Fascists, Socialists, Communists, and after the liberation of Rome, to German soldiers, partisans, displaced persons and others. As pope in 1971, Montini turned the Pontificia Commissione di Assistenza into ''

Caritas Italiana''.

Archbishop of Milan

After the death of

Cardinal

Cardinal or The Cardinal most commonly refers to

* Cardinalidae, a family of North and South American birds

**''Cardinalis'', genus of three species in the family Cardinalidae

***Northern cardinal, ''Cardinalis cardinalis'', the common cardinal of ...

Alfredo Ildefonso Schuster in 1954, Montini was appointed to succeed him as

Archbishop of Milan, which made him the secretary of the

Italian Bishops Conference.

[.] Pius XII presented the new archbishop "as his personal gift to Milan". He was consecrated bishop in

Saint Peter's Basilica

The Papal Basilica of Saint Peter in the Vatican (), or simply St. Peter's Basilica (; ), is a church of the Italian Renaissance architecture, Italian High Renaissance located in Vatican City, an independent microstate enclaved within the cit ...

by Cardinal

Eugène Tisserant

Eugène-Gabriel-Gervais-Laurent Tisserant (; 24 March 1884 – 21 February 1972) was a French prelate and cardinal of the Catholic Church. Elevated to the cardinalate in 1936, Tisserant was a prominent and long-time member of the Roman Curia.

...

, the Dean of the

College of Cardinals

The College of Cardinals (), also called the Sacred College of Cardinals, is the body of all cardinals of the Catholic Church. there are cardinals, of whom are eligible to vote in a conclave to elect a new pope. Appointed by the pope, ...

, since Pius XII was severely ill.

On 12 December 1954, Pius XII delivered a radio address from his sick bed about Montini's appointment to the crowd in St. Peter's Basilica. Both Montini and the Pope had tears in their eyes when Montini departed for his diocese with its 1,000 churches, 2,500 priests and 3,500,000 souls. On 5 January 1955, Montini formally took possession of his

Cathedral of Milan

Milan Cathedral ( ; ), or Metropolitan Cathedral-Basilica of the Nativity of Saint Mary (), is the cathedral church of Milan, Lombardy, Italy. Dedicated to the Nativity of St. Mary (), it is the seat of the Archbishop of Milan, currently Archbi ...

. Montini settled well into his new tasks among all groups of the faithful in the city, meeting cordially with intellectuals, artists, and writers.

Montini's philosophy

In his first months, Montini showed his interest in working conditions and labour issues by speaking to many unions and associations. He initiated the building of over 100 new churches, believing them the only non-utilitarian buildings in modern society, places for spiritual rest.

His public speeches were noticed in

Milan

Milan ( , , ; ) is a city in northern Italy, regional capital of Lombardy, the largest city in Italy by urban area and the List of cities in Italy, second-most-populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of nea ...

, Rome, and elsewhere. Some considered him a liberal when he asked lay people to love not only Catholics but also schismatics, Protestants, Anglicans, the indifferent, Muslims, pagans, and atheists. He gave a friendly welcome to a group of Anglican clergy visiting Milan in 1957 and subsequently exchanged letters with the

Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the Primus inter pares, ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the bishop of the diocese of Canterbury. The first archbishop ...

,

Geoffrey Fisher.

Pope Pius XII revealed at the 1952 secret consistory that both Montini and Tardini had declined appointments to the cardinalate,

and, in fact, Montini was never to be made a cardinal by Pius XII, who held no consistory and created no cardinals between the time he appointed Montini to Milan and his own death four years later. After Montini's friend Angelo Roncalli became

Pope John XXIII

Pope John XXIII (born Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli; 25 November 18813 June 1963) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 28 October 1958 until his death on 3 June 1963. He is the most recent pope to take ...

, he made Montini a cardinal in December 1958.

When the new pope announced

an ecumenical council, Cardinal Montini reacted with disbelief and said to

Giulio Bevilacqua: "This old boy does not know what a hornets nest he is stirring up." Montini was appointed to the Central Preparatory Commission in 1961. During the council, Pope John XXIII asked him to live in the Vatican, where he was a Commission for Extraordinary Affairs member, though he did not engage much in the floor debates. His main advisor was

Giovanni Colombo, whom he later appointed as his successor in Milan The commission was significantly overshadowed by the insistence of John XXIII that the Council complete all its work before Christmas 1962, to coincide with the 400th anniversary of the

Council of Trent

The Council of Trent (), held between 1545 and 1563 in Trent (or Trento), now in northern Italy, was the 19th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. Prompted by the Protestant Reformation at the time, it has been described as the "most ...

, an insistence which may have also been influenced by the Pope's having recently been told that he had cancer.

John had a vision but "did not have a clear agenda. His rhetoric seems to have had a note of over-optimism, a confidence in progress, which was characteristic of the 1960s."

Pastoral progressivism

During his period in Milan, Montini was widely seen as a progressive member of the Catholic hierarchy. He adopted new approaches to reach the faithful with pastoral care and carried through the liturgical reforms of Pius XII at the local level. For example, huge posters announced throughout the city that 1,000 voices would speak to them from 10 to 24 November 1957: more than 500 priests and many bishops, cardinals, and lay people delivered 7,000 sermons, not only in churches but in factories, meeting halls, houses, courtyards, schools, offices, military barracks, hospitals, hotels and wherever people congregated. His goal was re-introducing faith to a city without much religion. "If only we can say

Our Father and know what this means, then we would understand the Christian faith."

Pius XII

Pope Pius XII (; born Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli; 2 March 18769 October 1958) was the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 2 March 1939 until his death on 9 October 1958. He is the most recent p ...

asked Archbishop Montini to Rome in October 1957, where he gave the main presentation to the Second World Congress of

Lay Apostolate

The lay apostolate is made up of Laity, laypersons, who are neither Consecrated life (Catholic Church), consecrated religious nor in Holy Orders, who exercise a ministry within the Catholic Church. Lay apostolate organizations operate under the gen ...

. As Pro-Secretary of State, he had worked hard to form this worldwide organisation of lay people in 58 nations, representing 42 national organisations. He presented them to Pius XII in Rome in 1951. The second meeting in 1957 gave Montini an opportunity to express the lay apostolate in modern terms: "Apostolate means love. We will love all, but especially those, who need help... We will love our time, our technology, our art, our sports, our world."

Cardinal

On 20 June 1958,

Saul Alinsky

Saul David Alinsky (January 30, 1909 – June 12, 1972) was an American community activist and political theorist. His work through the Chicago-based Industrial Areas Foundation helping poor communities organize to press demands upon landlord ...

recalled meeting with Montini: "I had three wonderful meetings with Montini and I am sure that you have heard from him since." Alinsky also wrote to

George Nauman Shuster, two days before the papal conclave that elected John XXIII: "No, I don't know who the next Pope will be, but if it's to be Montini, the drinks will be on me for years to come."

Although some cardinals seem to have viewed Montini as a likely

papabile

( , , ; plural: ; ) is an unofficial Italian term coined by Vaticanologists and used internationally in many languages to describe a Catholic man—in practice, always a cardinal—who is thought of as a likely or possible candidate to be ...

candidate, possibly receiving some votes in the

1958 conclave, he had the handicap of not yet being a cardinal. Angelo Roncalli was elected pope on 28 October 1958 and took the name John XXIII. On 17 November 1958, ''

L'Osservatore Romano

''L'Osservatore Romano'' is the daily newspaper of Vatican City which reports on the activities of the Holy See and events taking place in the Catholic Church and the world. It is owned by the Holy See but is not an official publication, a role ...

'' announced a consistory for the creation of new cardinals, with Montini at the top of the list. When the Pope raised Montini to the cardinalate on 15 December 1958, he became

Cardinal-Priest

A cardinal is a senior member of the clergy of the Catholic Church. As titular members of the clergy of the Diocese of Rome, they serve as advisors to the pope, who is the bishop of Rome and the visible head of the worldwide Catholic Church. ...

of

Ss. Silvestro e Martino ai Monti. The Pope appointed him simultaneously to several Vatican congregations, drawing him frequently to Rome in the coming years.

Cardinal Montini journeyed to Africa in 1962, visiting

Ghana

Ghana, officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It is situated along the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, and shares borders with Côte d’Ivoire to the west, Burkina Faso to the north, and Togo to t ...

,

Sudan

Sudan, officially the Republic of the Sudan, is a country in Northeast Africa. It borders the Central African Republic to the southwest, Chad to the west, Libya to the northwest, Egypt to the north, the Red Sea to the east, Eritrea and Ethiopi ...

,

Kenya

Kenya, officially the Republic of Kenya, is a country located in East Africa. With an estimated population of more than 52.4 million as of mid-2024, Kenya is the 27th-most-populous country in the world and the 7th most populous in Africa. ...

,

Congo,

Rhodesia

Rhodesia ( , ; ), officially the Republic of Rhodesia from 1970, was an unrecognised state, unrecognised state in Southern Africa that existed from 1965 to 1979. Rhodesia served as the ''de facto'' Succession of states, successor state to the ...

, South Africa, and Nigeria. After this journey, John XXIII called Montini to a private audience to report on his trip, speaking for several hours. In fifteen other trips, he visited

Brazil

Brazil, officially the Federative Republic of Brazil, is the largest country in South America. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by area, fifth-largest country by area and the List of countries and dependencies by population ...

(1960) and the USA (1960), including New York City, Washington DC, Chicago, the

University of Notre Dame

The University of Notre Dame du Lac (known simply as Notre Dame; ; ND) is a Private university, private Catholic research university in Notre Dame, Indiana, United States. Founded in 1842 by members of the Congregation of Holy Cross, a Cathol ...

in Indiana, Boston,

Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

, and

Baltimore

Baltimore is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland. With a population of 585,708 at the 2020 census and estimated at 568,271 in 2024, it is the 30th-most populous U.S. city. The Baltimore metropolitan area is the 20th-large ...

. He usually vacationed in

Engelberg Abbey, a secluded Benedictine monastery in Switzerland.

Papacy

Papal conclave

Montini was generally seen as the

most likely papal successor, being close to both Popes Pius XII and John XXIII, as well as his pastoral and administrative background, his insight, and his determination. John XXIII had previously known the Vatican as an official until his appointment to Venice as a papal diplomat, but returning to Rome at age 66, he may at times have felt uncertain in dealing with the professional

Roman Curia

The Roman Curia () comprises the administrative institutions of the Holy See and the central body through which the affairs of the Catholic Church are conducted. The Roman Curia is the institution of which the Roman Pontiff ordinarily makes use ...

. Montini, on the other hand, had learned its innermost workings while working in it for a generation.

Unlike the

papabile

( , , ; plural: ; ) is an unofficial Italian term coined by Vaticanologists and used internationally in many languages to describe a Catholic man—in practice, always a cardinal—who is thought of as a likely or possible candidate to be ...

cardinals

Giacomo Lercaro of

Bologna

Bologna ( , , ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in northern Italy. It is the List of cities in Italy, seventh most populous city in Italy, with about 400,000 inhabitants and 150 different nationalities. Its M ...

and

Giuseppe Siri of

Genoa

Genoa ( ; ; ) is a city in and the capital of the Italian region of Liguria, and the sixth-largest city in Italy. As of 2025, 563,947 people live within the city's administrative limits. While its metropolitan city has 818,651 inhabitan ...

, Montini was identified neither left nor right nor as a radical reformer. He was viewed as most likely to continue the

Second Vatican Council

The Second Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, commonly known as the or , was the 21st and most recent ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. The council met each autumn from 1962 to 1965 in St. Peter's Basilica in Vatican City for session ...

, which had adjourned without tangible results.

In the conclave after John XXIII's death, Montini was elected pope on the sixth ballot on 21 June. When the

Dean of the College of Cardinals Eugène Tisserant

Eugène-Gabriel-Gervais-Laurent Tisserant (; 24 March 1884 – 21 February 1972) was a French prelate and cardinal of the Catholic Church. Elevated to the cardinalate in 1936, Tisserant was a prominent and long-time member of the Roman Curia.

...

asked if he accepted the election, Montini said ''"Accepto, in nomine Domini"'' ("I accept, in the name of the Lord"). He took the name "Paul VI" in honor of

Paul the Apostle

Paul, also named Saul of Tarsus, commonly known as Paul the Apostle and Saint Paul, was a Apostles in the New Testament, Christian apostle ( AD) who spread the Ministry of Jesus, teachings of Jesus in the Christianity in the 1st century, first ...

.

At one point during the conclave on 20 June, it was said that Cardinal

Gustavo Testa lost his temper and demanded that opponents of Montini halt their efforts to thwart his election. Montini, fearful of causing strife, started to rise to dissuade the cardinals from voting for him, but Cardinal

Giovanni Urbani dragged him back, muttering, "Eminence, shut up!"

The white smoke first rose from the chimney of the

Sistine Chapel

The Sistine Chapel ( ; ; ) is a chapel in the Apostolic Palace, the pope's official residence in Vatican City. Originally known as the ''Cappella Magna'' ('Great Chapel'), it takes its name from Pope Sixtus IV, who had it built between 1473 and ...

at 11:22 am, when

Protodeacon

Protodeacon derives from the Greek ''proto-'' meaning 'first' and ''diakonos'', which is a standard ancient Greek word meaning "assistant", "servant", or "waiting-man". The word in English may refer to any of various clergy, depending upon the usa ...

Cardinal

Alfredo Ottaviani announced to the public the successful election of Montini. When the new pope appeared on the central loggia, he gave the shorter

episcopal blessing as his first

apostolic blessing

The apostolic blessing or papal blessing is a blessing imparted by the pope, either directly or by delegation through others. Bishops are empowered to grant it three times a year and any priest can do so for the dying.

The apostolic blessing is n ...

rather than the longer, traditional ''

Urbi et Orbi''.

Of the papacy, Paul VI wrote in his journal: "The position is unique. It brings great solitude. 'I was solitary before, but now my solitude becomes complete and awesome.'"

Less than two years later, on 2 May 1965, Paul informed the

dean of the College of Cardinals that his health might make it impossible to function as pope. He wrote, "In case of infirmity, which is believed to be incurable or is of long duration and which impedes

us from sufficiently exercising the functions of our apostolic ministry; or in the case of another serious and prolonged impediment", he would renounce his office "both as bishop of Rome as well as head of the same holy Catholic Church".

Reforms of papal ceremony

Paul VI did away with much of the papacy's regal splendor.

His coronation on 30 June 1963 was the last

such ceremony; his successor

Pope John Paul I

Pope John Paul I (born Albino Luciani; 17 October 1912 – 28 September 1978) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 26 August 1978 until his death 33 days later. His reign is among the shortest in papal h ...

substituted an

inauguration

In government and politics, inauguration is the process of swearing a person into office and thus making that person the incumbent. Such an inauguration commonly occurs through a formal ceremony or special event, which may also include an inau ...

(which Paul had substantially modified, but which he left mandatory in his 1975

apostolic constitution

An apostolic constitution () is the most solemn form of legislation issued by the Pope.New Commentary on the Code of Canon Law, pg. 57, footnote 36.

By their nature, apostolic constitutions are addressed to the public. Generic constitutions use ...

''

Romano Pontifici Eligendo''). At his coronation, Paul wore a

tiara

A tiara (, ) is a head ornament adorned with jewels. Its origins date back to ancient Greco-Roman world. In the late 18th century, the tiara came into fashion in Europe as a prestigious piece of jewelry to be worn by women at formal occasions ...

presented by the Archdiocese of Milan. Near the end of the third session of the

Second Vatican Council

The Second Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, commonly known as the or , was the 21st and most recent ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. The council met each autumn from 1962 to 1965 in St. Peter's Basilica in Vatican City for session ...

in 1964, Paul VI descended the steps of the papal throne in

St. Peter's Basilica and ascended the altar, on which he laid the tiara as a sign of the renunciation of human glory and power in keeping with the innovative spirit of the council. It was announced that the tiara would be sold for charity. The purchasers arranged for it to be displayed as a gift to American Catholics in the crypt of the

Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, D.C.

In 1968, with the

motu proprio

In law, (Latin for 'on his own impulse') describes an official act taken without a formal request from another party. Some jurisdictions use the term for the same concept.

In Catholic canon law, it refers to a document issued by the pope on h ...

''

Pontificalis Domus

''Pontificalis Domus'' () was a ''motu proprio'' document issued by Pope Paul VI on 28 March 1968, in the fifth year of his pontificate. It reorganized the Papal household, Papal Household, which had been known until then as the Papal Court.

Co ...

'', he discontinued most of the ceremonial functions of the old

Papal nobility

The papal nobility are the aristocracy of the Holy See, composed of persons holding titles bestowed by the Pope. From the Middle Ages into the nineteenth century, the papacy held direct temporal power in the Papal States, and many titles of papal ...

at the court (reorganized as the

household

A household consists of one or more persons who live in the same dwelling. It may be of a single family or another type of person group. The household is the basic unit of analysis in many social, microeconomic and government models, and is im ...

), save for the

Prince Assistants to the Papal Throne. He also abolished the

Palatine Guard

The Palatine Guard () was a military unit of Holy See, the Vatican. It was formed in 1850 by Pope Pius IX, who ordered that the two militia units of the Papal States be amalgamated. The corps was formed as an infantry unit, and took part in watch ...

and the

Noble Guard, leaving the Pontifical

Swiss Guard

The Pontifical Swiss Guard,; ; ; ; , %5BCorps of the Pontifical Swiss Guard%5D. ''vatican.va'' (in Italian). Retrieved 19 July 2022. also known as the Papal Swiss Guard or simply Swiss Guard,Swiss Guards , History, Vatican, Uniform, Require ...

as the sole military order of the Vatican.

Completion of the Vatican Council

Paul VI decided to reconvene

Vatican II

The Second Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, commonly known as the or , was the 21st and most recent Catholic ecumenical councils, ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. The council met each autumn from 1962 to 1965 in St. Peter's Basilic ...

and completed it in 1965. Faced with conflicting interpretations and controversies, he directed the implementation of its reform goals.

Ecumenical orientation

During Vatican II, the council fathers avoided statements that might anger non-Catholic Christians. Cardinal

Augustin Bea, the President of the

Christian Unity Secretariat, always had the full support of Paul VI in his attempts to ensure that the Council language was friendly and open to the sensitivities of Protestant and Orthodox churches, whom he had invited to all sessions at the request of

Pope John XXIII

Pope John XXIII (born Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli; 25 November 18813 June 1963) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 28 October 1958 until his death on 3 June 1963. He is the most recent pope to take ...

. Bea also was strongly involved in the passage of ''

Nostra aetate

(from Latin: "In our time"), or the Declaration on the Relation of the Church with Non-Christian Religions, is an official declaration of the Second Vatican Council, an Catholic ecumenical councils, ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. I ...

'', which regulates the Church's relations with

Judaism

Judaism () is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic, Monotheism, monotheistic, ethnic religion that comprises the collective spiritual, cultural, and legal traditions of the Jews, Jewish people. Religious Jews regard Judaism as their means of o ...

and members of other religions.

Dialogue with the world

After being elected Bishop of Rome, Paul VI first met with the priests in his new diocese. He told them that he started a dialogue with the modern world in Milan and asked them to seek contact with people from all walks of life. Six days after his election, he announced that he would continue Vatican II and convened the opening on 29 September 1963.

In a radio address to the world, Paul VI praised his predecessors, the strength of

Pius XI

Pope Pius XI (; born Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti, ; 31 May 1857 – 10 February 1939) was head of the Catholic Church from 6 February 1922 until his death in February 1939. He was also the first sovereign of the Vatican City State u ...

, the wisdom and intelligence of

Pius XII

Pope Pius XII (; born Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli; 2 March 18769 October 1958) was the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 2 March 1939 until his death on 9 October 1958. He is the most recent p ...

, and the love of

John XXIII

Pope John XXIII (born Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli; 25 November 18813 June 1963) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 28 October 1958 until his death on 3 June 1963. He is the most recent pope to take ...

. As his pontifical goals, he mentioned the continuation and completion of Vatican II, the

Canon Law

Canon law (from , , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical jurisdiction, ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its membe ...

reform, and improved social peace and justice worldwide. The unity of Christianity would be central to his activities.

Council priorities

The Pope re-opened the Ecumenical Council on 29 September 1963, giving it four key priorities:

* A better understanding of the Catholic Church

* Church reforms

* Advancing the unity of Christianity

* Dialogue with the world

He reminded the Council Fathers that only a few years earlier, Pope Pius XII had issued the encyclical ''

Mystici corporis'' about the

mystical body of Christ. He asked them not to repeat or create new dogmatic definitions but to simply explain how the Church sees itself. He thanked the representatives of other Christian communities for their attendance and asked for their forgiveness if the Catholic Church was at fault for their separation. He also reminded the Council Fathers that many bishops from the East had been forbidden to attend by their national governments.

Third and fourth sessions

Paul VI opened the third period on 14 September 1964, telling the Council Fathers that he viewed the text about the Church as the most important document to come out from the council. As the Council discussed the role of bishops in the papacy, Paul VI issued an

explanatory note confirming the primacy of the papacy, a step that was viewed by some as meddling in the council's affairs. American bishops pushed for a speedy resolution on religious freedom, but Paul VI insisted this be approved together with related texts on topics such as

ecumenism

Ecumenism ( ; alternatively spelled oecumenism)also called interdenominationalism, or ecumenicalismis the concept and principle that Christians who belong to different Christian denominations should work together to develop closer relationships ...

.

The Pope concluded the session on 21 November 1964 with the formal pronouncement of Mary as

Mother of the Church

Mother of the Church () is a Titles of Mary, title given to Mary, mother of Jesus, Mary in the Catholic Church, as officially declared by Pope Paul VI in 1964. The title first appeared in the 4th century writings of Saint Ambrose of Milan, as redi ...

.

Between the third and fourth sessions, the Pope announced reforms in the areas of

Roman Curia

The Roman Curia () comprises the administrative institutions of the Holy See and the central body through which the affairs of the Catholic Church are conducted. The Roman Curia is the institution of which the Roman Pontiff ordinarily makes use ...

, revision of

Canon law

Canon law (from , , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical jurisdiction, ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its membe ...

, regulations for

interfaith marriage

Interfaith marriage, sometimes called interreligious marriage or mixed marriage, is marriage between spouses professing and being legally part of different religions. Although interfaith marriages are often established as civil marriages, in so ...

s, and

birth control

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth control only be ...

issues. He opened the council's final session, concelebrating with bishops from countries where the Church was persecuted. Several texts proposed for his approval had to be changed, but all were finally agreed upon. The council was concluded on 8 December 1965: the

Feast of the Immaculate Conception

The Solemnity of the Immaculate Conception celebrates the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary on 8 December, nine months before the feast of the Nativity of Mary on 8 September. It is one of the most important Marian feasts in the l ...

.

In the council's final session, Paul VI announced that he would open the canonisation processes of his immediate predecessors: Pope Pius XII and Pope John XXIII.

Universal call to holiness

According to Paul VI, "the most characteristic and ultimate purpose of the teachings of the Council" is the

universal call to holiness

The universal call to holiness is a teaching of the Roman Catholic Church that all people are called to be holy, and is based on Matthew 5:48: "Be you therefore perfect, as also your heavenly Father is perfect" (). In the first book of the Bible, ...

: "all the faithful of Christ of whatever rank or status, are called to the fullness of the Christian life and to the perfection of charity; by this holiness as such a more human manner of living is promoted in this earthly society." This teaching is found in ''

Lumen Gentium

, the Dogmatic Constitution on the Church, is one of the principal documents of the Second Vatican Council. This dogmatic constitution was promulgated by Pope Paul VI on 21 November 1964, following approval by the assembled bishops by a vote of 2 ...

'', the Dogmatic Constitution on the Church, promulgated by Paul VI on 21 November 1964.

Church reforms

Synod of Bishops

On 14 September 1965, he established the

Synod of Bishops as a permanent institution of the Catholic Church and an advisory body to the papacy. Several meetings were held on specific issues during his pontificate, such as the Synod of Bishops on evangelization in the modern world, which started on 9 September 1974.

Curia reform

Pope Paul VI knew the

Roman Curia

The Roman Curia () comprises the administrative institutions of the Holy See and the central body through which the affairs of the Catholic Church are conducted. The Roman Curia is the institution of which the Roman Pontiff ordinarily makes use ...

well, having worked there for a generation from 1922 to 1954. He implemented his reforms in stages. On 1 March 1968, he issued a regulation, a process initiated by Pius XII and continued by John XXIII. On 28 March, with ''Pontificalis Domus'', and in several additional Apostolic Constitutions in the following years, he revamped the entire Curia, which included reduction of bureaucracy, streamlining of existing congregations, and a broader representation of non-Italians in the Curial positions.

Age limits and restrictions

On 6 August 1966, Paul VI asked all bishops to submit their resignations to the pontiff by their 75th birthday. They were not required to do so but "earnestly requested of their own free will to tender their resignation from office". He extended this request to all cardinals in ''

Ingravescentem aetatem

''Ingravescentem aetatem'' () is a document issued by Pope Paul VI, dated 21 November 1970. It is divided into eight chapters. The Latin title is taken from the incipit, and translates to 'advancing age'. It established a rule that only cardinal ...

'' on 21 November 1970, with the further provision that cardinals would relinquish their offices in the

Roman Curia

The Roman Curia () comprises the administrative institutions of the Holy See and the central body through which the affairs of the Catholic Church are conducted. The Roman Curia is the institution of which the Roman Pontiff ordinarily makes use ...

upon reaching their 80th birthday.

These retirement rules enabled the Pope to fill several positions with younger prelates and reduce the Italian domination of the Roman Curia. His 1970 measures also revolutionised papal elections by restricting the right to vote in

papal conclave

A conclave is a gathering of the College of Cardinals convened to appoint the pope of the Catholic Church. Catholics consider the pope to be the apostolic successor of Saint Peter and the earthly head of the Catholic Church.

Concerns around ...

s to cardinals who had not yet reached their 80th birthday, a class known since then as "cardinal electors". This reduced the power of the Italians and the Curia in the next conclave. Some senior cardinals objected to losing their voting privilege without effect.

Paul VI's measures also limited the number of cardinal electors to a maximum of 120, a rule disregarded on several occasions by each of his successors. Previously, Paul VI himself had been the first pope to increase the number above 120 (from

82 in 1963 to 134

in April 1969; but he reduced the number of cardinal electors below 120 in 1971 by simultaneously introducing the voting age limit).

Some prelates questioned whether he should not apply these retirement rules to himself. When Pope Paul was asked towards the end of his papacy whether he would retire at age 80, he replied "Kings can abdicate, Popes cannot."

Liturgy

Reform of the

liturgy

Liturgy is the customary public ritual of worship performed by a religious group. As a religious phenomenon, liturgy represents a communal response to and participation in the sacred through activities reflecting praise, thanksgiving, remembra ...

, an aim of the 20th-century

liturgical movement, mainly in France and Germany, was officially recognised as legitimate by Pius XII in his encyclical ''

Mediator Dei''. During his pontificate, he eased regulations on the obligatory use of Latin in Catholic liturgies, permitting some use of vernacular languages during baptisms, funerals, and other events. In 1951 and 1955, he revised the Easter liturgies, most notably that of the

Easter Triduum. The

Second Vatican Council

The Second Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, commonly known as the or , was the 21st and most recent ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. The council met each autumn from 1962 to 1965 in St. Peter's Basilica in Vatican City for session ...

(1962–1965) gave some directives in its document ''

Sacrosanctum Concilium

''Sacrosanctum Concilium'', the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy, is one of the constitutions of the Second Vatican Council. It was approved by the assembled bishops by a vote of 2,147 to 4 and promulgated by Pope Paul VI on 4 December 1963. T ...

'' for a general revision of the

Roman Missal

The Roman Missal () is the book which contains the texts and rubrics for the celebration of the Roman Rite, the most common liturgy and Mass of the Catholic Church. There have been several editions.

History

Before the Council of Trent (1570)

...

. Within four years of the close of the council, Paul VI promulgated in 1969 the first postconciliar edition, which included three new

Eucharistic Prayers in addition to the

Roman Canon, until then the only

anaphora in the

Roman Rite

The Roman Rite () is the most common ritual family for performing the ecclesiastical services of the Latin Church, the largest of the ''sui iuris'' particular churches that comprise the Catholic Church. The Roman Rite governs Rite (Christianity) ...

. Use of

vernacular

Vernacular is the ordinary, informal, spoken language, spoken form of language, particularly when perceptual dialectology, perceived as having lower social status or less Prestige (sociolinguistics), prestige than standard language, which is mor ...

languages was expanded by decision of

episcopal conference

An episcopal conference, often also called a bishops’ conference or conference of bishops, is an official assembly of the bishops of the Catholic Church in a given territory. Episcopal conferences have long existed as informal entities. The fir ...

s, not by papal command. In addition to his revision of the

Roman Missal

The Roman Missal () is the book which contains the texts and rubrics for the celebration of the Roman Rite, the most common liturgy and Mass of the Catholic Church. There have been several editions.

History

Before the Council of Trent (1570)

...

, Pope Paul VI issued instructions in 1964, 1967, 1968, 1969, and 1970, reforming other elements of the liturgy of the Roman Church.

These reforms were not universally welcomed. Questions were raised about the need to replace the

1962 Roman Missal

The Tridentine Mass, also known as the Extraordinary Form of the Roman Rite or ''usus antiquior'' (), Vetus Ordo or the Traditional Latin Mass (TLM) or the Traditional Rite, is the liturgy in the Roman Missal of the Catholic Church codified in 1 ...

, which, though decreed on 23 June 1962, became available only in 1963, a few months before the Second Vatican Council's ''Sacrosanctum Concilium'' decree ordered that it be altered. Attachment to it led to open ruptures, of which the most widely known is that of

Marcel Lefebvre

Marcel François Marie Joseph Lefebvre (29 November 1905 – 25 March 1991) was a Catholic Church in France, French Catholic prelate who served as Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Dakar, Archbishop of Dakar from 1955 to 1962. He was a major inf ...

.

Pope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II (born Karol Józef Wojtyła; 18 May 19202 April 2005) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 16 October 1978 until Death and funeral of Pope John Paul II, his death in 2005.

In his you ...

granted bishops the right to authorise the use of the 1962 Missal (''

Quattuor abhinc annos'' and ''

Ecclesia Dei'') and in 2007

Pope Benedict XVI

Pope BenedictXVI (born Joseph Alois Ratzinger; 16 April 1927 – 31 December 2022) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 19 April 2005 until his resignation on 28 February 2013. Benedict's election as p ...

, while stating that the Mass of Paul VI and John Paul II "obviously is and continues to be the normal Form – the ''Forma ordinaria'' – of the Eucharistic Liturgy", gave general permission to priests of the

Latin Church

The Latin Church () is the largest autonomous () particular church within the Catholic Church, whose members constitute the vast majority of the 1.3 billion Catholics. The Latin Church is one of 24 Catholic particular churches and liturgical ...

to use either the 1962 Missal or the post-

Vatican II

The Second Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, commonly known as the or , was the 21st and most recent Catholic ecumenical councils, ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. The council met each autumn from 1962 to 1965 in St. Peter's Basilic ...

Missal both privately and, under certain conditions, publicly. In 2021, Pope Francis removed many of faculties granted by Pope Benedict XVI with the publishing of his ''motu proprio'', ''

Traditionis Custodes'', thus limiting the use of 1962 Roman Missal.

Relations and dialogues

To Paul VI, a dialogue with all of humanity was essential not as an aim but as a means to find the truth. According to Paul, dialogue is based on the full equality of all participants. This equality is rooted in the common search for the truth. He said: "Those who have the truth, are in a position as not having it, because they are forced to search for it every day in a deeper and more perfect way. Those who do not have it, but search for it with their whole heart, have already found it."

Dialogues

In 1964, Paul VI created a Secretariat for non-Christians, later renamed the

Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue, and a year later, a new Secretariat (later Pontifical Council) for Dialogue with Non-Believers. This latter one was in 1993 incorporated by Pope John Paul II in the

Pontifical Council for Culture, which he had established in 1982. In 1971, Paul VI created a papal office for economic development and catastrophic assistance. To foster common bonds with all persons of goodwill, he decreed an annual peace day to be celebrated on 1 January every year. Trying to improve the condition of Christians behind the

Iron Curtain

The Iron Curtain was the political and physical boundary dividing Europe into two separate areas from the end of World War II in 1945 until the end of the Cold War in 1991. On the east side of the Iron Curtain were countries connected to the So ...

, Paul VI engaged in dialogue with Communist authorities at several levels, receiving Foreign Minister

Andrei Gromyko and

Chairman

The chair, also chairman, chairwoman, or chairperson, is the presiding officer of an organized group such as a board, committee, or deliberative assembly. The person holding the office, who is typically elected or appointed by members of the gro ...

of the

Presidium of the Supreme Soviet

The Presidium of the Supreme Soviet () was the standing body of the highest organ of state power, highest body of state authority in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR).The Presidium of the Soviet Union is, in short, the legislativ ...

Nikolai Podgorny

Nikolai Viktorovich Podgorny ( – 12 January 1983) was a Soviet statesman who served as the Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, the head of state of the Soviet Union, from 1965 to 1977.

Podgorny was born to a Ukrainian working-c ...

in 1966 and 1967 in the Vatican. The situation of the Church in

Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

,

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

, and

Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

improved during his pontificate.

Foreign travels

Pope Paul VI became the first pope to visit six continents. He was also the first pontiff to travel on an airplane, visit the Holy Land on pilgrimage, and travel outside Italy in a century. He travelled more widely than any of his predecessors, earning the nickname "the Pilgrim Pope". He visited the

Holy Land

The term "Holy Land" is used to collectively denote areas of the Southern Levant that hold great significance in the Abrahamic religions, primarily because of their association with people and events featured in the Bible. It is traditionall ...

in 1964 and participated in

Eucharistic congresses in

Bombay

Mumbai ( ; ), also known as Bombay ( ; its official name until 1995), is the capital city of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of Maharashtra. Mumbai is the financial centre, financial capital and the list of cities i ...

, India, and

Bogotá

Bogotá (, also , , ), officially Bogotá, Distrito Capital, abbreviated Bogotá, D.C., and formerly known as Santa Fe de Bogotá (; ) during the Spanish Imperial period and between 1991 and 2000, is the capital city, capital and largest city ...

, Colombia. In 1966, he was twice denied permission to visit

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

for the thousandth anniversary of the

introduction of Christianity in Poland. In 1967, he visited the shrine of

Our Lady of Fátima

Our Lady of Fátima (, ; formally known as Our Lady of the Holy Rosary of Fátima) is a Catholic title of Mary, mother of Jesus, based on the Marian apparitions reported in 1917 by three shepherd children at the Cova da Iria in Fátima, Portu ...

in

Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, is a country on the Iberian Peninsula in Southwestern Europe. Featuring Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point in continental Europe, Portugal borders Spain to its north and east, with which it share ...

on the fiftieth anniversary of the

apparitions there. He undertook a pastoral visit to Uganda in 1969, the first by a reigning pope to Africa. Pope Paul VI became the first reigning pontiff to visit the Western hemisphere when he addressed the United Nations in New York City in October 1965. As the U.S. involvement in the

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

was escalating, Paul VI pleaded for peace before the U.N.:

Attempted assassination

Shortly after arriving at

Manila International Airport, the Philippines on 27 November 1970, the Pope, closely followed by President

Ferdinand Marcos

Ferdinand Emmanuel Edralin Marcos Sr. (September 11, 1917 – September 28, 1989) was a Filipino lawyer, politician, dictator, and Kleptocracy, kleptocrat who served as the tenth president of the Philippines from 1965 to 1986. He ruled the c ...

and personal aide

Pasquale Macchi, who was private secretary to Pope Paul VI, were encountered suddenly by a crew-cut, cassock-clad man who tried to attack the Pope with a knife. Macchi pushed the man away; police identified the would-be assassin as

Benjamín Mendoza y Amor Flores of

La Paz, Bolivia

La Paz, officially Nuestra Señora de La Paz ( Aymara: Chuqi Yapu ), is the seat of government of the Plurinational State of Bolivia. With 755,732 residents as of 2024, La Paz is the third-most populous city in Bolivia. Its metropolitan area ...

. Mendoza was an artist living in the Philippines. The Pope continued his trip and thanked Marcos and Macchi, who had moved to protect him during the attack.

New diplomacy

Like his predecessor

Pius XII

Pope Pius XII (; born Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli; 2 March 18769 October 1958) was the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 2 March 1939 until his death on 9 October 1958. He is the most recent p ...

, Paul VI put much emphasis on the dialogue with all nations of the world through establishing diplomatic relations. The number of foreign embassies accredited to the Vatican doubled during his pontificate.

This was a reflection of a new understanding between church and state, which had been formulated first by

Pius XI

Pope Pius XI (; born Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti, ; 31 May 1857 – 10 February 1939) was head of the Catholic Church from 6 February 1922 until his death in February 1939. He was also the first sovereign of the Vatican City State u ...

and Pius XII but decreed by Vatican II. The pastoral constitution ''

Gaudium et spes

(, "Joys and Hopes"), the Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World, is one of the four constitutions promulgated during the Second Vatican Council between 1963 and 1965. Issued on 7 December 1965, it was the last and longest publ ...

'' stated that the Catholic Church is not bound to any form of government and is willing to cooperate with all forms. The Church maintained its right to select bishops on its own without any interference by the State.

Pope Paul VI sent one of 73

Apollo 11 Goodwill Messages to

NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the federal government of the United States, US federal government responsible for the United States ...

for the historic first lunar landing. The message still rests on the lunar surface today. It has the words of the

8th Psalm, and the Pope wrote, "To the Glory of the name of God who gives such power to men, we ardently pray for this wonderful beginning."

Theology

Mariology

Pope Paul VI made extensive contributions to

Mariology

Mariology is the Christian theological study of Mary, mother of Jesus. Mariology seeks to relate doctrine or dogma about Mary to other doctrines of the faith, such as those concerning Jesus and notions about redemption, intercession and g ...

(theological teaching and devotions) during his pontificate. Given its new ecumenical orientation, he attempted to present the Marian teachings of the church. In his inaugural encyclical ''Ecclesiam suam'' (section below), the Pope called Mary the ideal of Christian perfection. He regards "devotion to the Mother of God as of paramount importance in living the life of the Gospel."

Encyclicals

Paul VI authored seven

encyclical

An encyclical was originally a circular letter sent to all the churches of a particular area in the ancient Roman Church. At that time, the word could be used for a letter sent out by any bishop. The word comes from the Late Latin (originally fr ...

s.

=''Ecclesiam suam''

=

''Ecclesiam suam'' was given at St. Peter's Basilica, Rome, on the

Feast of the Transfiguration

The Feast of the Transfiguration is celebrated by various Christian communities in honor of the transfiguration of Jesus. The origins of the feast are less than certain and may have derived from the dedication of three basilicas on Mount Tabor.' ...

, 6 August 1964, the second year of his pontificate. Paul VI appealed to "all people of good will" and discussed necessary dialogues within the Church, between the churches, and with atheism.

=''Mense maio''

=

The encyclical ''

Mense maio'' (from 29 April 1965) focused on the Virgin Mary, to whom traditionally the month of May is dedicated as the Mother of God. Paul VI writes that Mary is rightly regarded as how people are led to Christ. Therefore, the person who encounters Mary cannot help but encounter Christ.

=''Mysterium fidei''

=

On 3 September 1965, Paul VI issued ''Mysterium fidei'', on the

Eucharist

The Eucharist ( ; from , ), also called Holy Communion, the Blessed Sacrament or the Lord's Supper, is a Christianity, Christian Rite (Christianity), rite, considered a sacrament in most churches and an Ordinance (Christianity), ordinance in ...

. The encyclical critiques certain contemporary Eucharistic theologies and liturgical practices perceived to undermine traditional Catholic doctrine. The Church, according to Paul VI, has no reason to give up the deposit of faith in such a vital matter.

=''Christi Matri''

=

On 15 September 1966, Paul VI issued ''Christi Matri'', a request for the faithful to pray for peace during October 1966. As reasons for this call to prayer, Paul VI alludes to the

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

and lists concern about "the growing

nuclear armaments race, the senseless nationalism, the racism, the obsession for revolution, the separations imposed upon citizens, the nefarious plots, the slaughter of innocent people."

=''Populorum progressio''

=

''Populorum progressio'', released on 26 March 1967, dealt with "the development of peoples" and that the world's economy should serve humanity and not just a few. It develops traditional principles of Catholic social teaching, including the right to a just wage, the right to security of employment, the right to fair and reasonable working conditions, the right to join a union, and the

universal destination of goods.

In addition, ''Populorum progressio'' opines that real peace in the world is conditional on justice. He repeated his demands expressed in Bombay in 1964 for a large-scale World Development Organization as a matter of international justice and peace. He rejected notions of instigating revolution and force in changing economic conditions.

=''Sacerdotalis caelibatus''

=

''Sacerdotalis caelibatus'' (Latin for "Of the celibate priesthood"), promulgated on 24 June 1967, defends the Catholic Church's tradition of

priestly celibacy in the West. Written in response to postconciliar questioning of the discipline of clerical celibacy, the encyclical reaffirms the historical ecclesiastical discipline that because celibacy is an ideal state, it continues to be mandatory for priests. To Catholic conceptions of the priesthood, celibacy symbolizes the reality of the kingdom of God amid modern society. The priestly celibacy is closely linked to the sacramental priesthood.

However, during his pontificate, Paul VI was permissive in allowing bishops to grant

laicisation of priests who wanted to leave the

sacerdotal state.

John Paul II

Pope John Paul II (born Karol Józef Wojtyła; 18 May 19202 April 2005) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 16 October 1978 until Death and funeral of Pope John Paul II, his death in 2005.

In his you ...

changed this policy in 1980, and the 1983 Code of

Canon Law

Canon law (from , , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical jurisdiction, ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its membe ...

made it explicit that only the Pope can, in exceptional circumstances, grant laicization.

=''Humanae vitae''

=

Of his seven encyclicals, Pope Paul VI is best known for his encyclical ''Humanae vitae'' (''Of Human Life'', subtitled ''On the Regulation of Birth''), published on 25 July 1968, responding to the findings of the

Pontifical Commission on Birth Control, affirming the minority report. The encyclical reaffirmed the Catholic Church's prior condemnation of

artificial birth control. The expressed views of Paul VI reflected the teachings of his predecessors, especially

Pius XI

Pope Pius XI (; born Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti, ; 31 May 1857 – 10 February 1939) was head of the Catholic Church from 6 February 1922 until his death in February 1939. He was also the first sovereign of the Vatican City State u ...

,

Pius XII

Pope Pius XII (; born Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli; 2 March 18769 October 1958) was the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 2 March 1939 until his death on 9 October 1958. He is the most recent p ...

and

John XXIII

Pope John XXIII (born Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli; 25 November 18813 June 1963) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 28 October 1958 until his death on 3 June 1963. He is the most recent pope to take ...

.

The encyclical teaches that marriage constitutes a union of the loving couple with a loving God, in which the two persons cooperate with God in the creation of a new person. For this reason, the encyclicals that the transmission of human life is a most serious role in which married people collaborate freely and responsibly with God.

This divine partnership, according to Paul VI, does not allow for arbitrary human decisions, which may limit divine providence. The Pope does not paint an overly romantic picture of marriage: marital relations are a source of great joy, but also of difficulties and hardships.

The question of human procreation exceeds in the view of Paul VI specific disciplines such as

biology

Biology is the scientific study of life and living organisms. It is a broad natural science that encompasses a wide range of fields and unifying principles that explain the structure, function, growth, History of life, origin, evolution, and ...

,

psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. Its subject matter includes the behavior of humans and nonhumans, both consciousness, conscious and Unconscious mind, unconscious phenomena, and mental processes such as thoughts, feel ...

,

demography

Demography () is the statistical study of human populations: their size, composition (e.g., ethnic group, age), and how they change through the interplay of fertility (births), mortality (deaths), and migration.

Demographic analysis examine ...

or

sociology

Sociology is the scientific study of human society that focuses on society, human social behavior, patterns of Interpersonal ties, social relationships, social interaction, and aspects of culture associated with everyday life. The term sociol ...

. The reason for this, according to Paul VI, is that married love takes its origin from God, who "is love". From this basic dignity, he defines his position:

The reaction to the continued prohibitions of artificial birth control was mixed. The encyclical was welcomed in Italy, Spain, Portugal, and Poland. In Latin America, much support developed for the Pope and his encyclical. As

World Bank

The World Bank is an international financial institution that provides loans and Grant (money), grants to the governments of Least developed countries, low- and Developing country, middle-income countries for the purposes of economic development ...

president

Robert McNamara

Robert Strange McNamara (; June 9, 1916 – July 6, 2009) was an American businessman and government official who served as the eighth United States secretary of defense from 1961 to 1968 under presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson ...

declared at the 1968

Annual Meeting of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank Group that countries permitting birth control practices would get preferential access to resources, doctors in

La Paz

La Paz, officially Nuestra Señora de La Paz (Aymara language, Aymara: Chuqi Yapu ), is the seat of government of the Bolivia, Plurinational State of Bolivia. With 755,732 residents as of 2024, La Paz is the List of Bolivian cities by populati ...

, Bolivia, called it insulting that money should be exchanged for the conscience of a Catholic nation. In Colombia, Cardinal Archbishop

Aníbal Muñoz Duque

Aníbal Muñoz Duque (3 October 1908 – 15 January 1987) was a Roman Catholic Cardinal and Archbishop of Bogotá.

Biography

He was born in Santa Rosa de Osos, Colombia as the son of José María Muñoz and Ana Rosa Duque. He was educated ...

declared, "If American conditionality undermines Papal teachings, we prefer not to receive one cent."

The

Senate of Bolivia passed a resolution stating that ''Humanae vitae'' could be discussed in its implications for individual consciences but was of greatest significance because the papal document defended the rights of developing nations to determine their own population policies.

The

Jesuit

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

journal ''Sic'' dedicated one edition to the encyclical with supportive contributions.