Pliny's Natural History on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The ''Natural History'' () is a Latin work by

Pliny's ''Natural History'' was written alongside other substantial works (which have since been lost). Pliny (AD 23–79) combined his scholarly activities with a busy career as an imperial administrator for the emperor

Pliny's ''Natural History'' was written alongside other substantial works (which have since been lost). Pliny (AD 23–79) combined his scholarly activities with a busy career as an imperial administrator for the emperor

To Baebius Macer

.'' in "Letters of Pliny the Younger" with introduction by John B. Firth.

About the middle of the 3rd century, an abstract of the geographical portions of Pliny's work was produced by

About the middle of the 3rd century, an abstract of the geographical portions of Pliny's work was produced by

The oldest surviving manuscripts of the Naturalis are known as '' vetustiores'' ("older ones"), all dating from the early 8th to 9th centuries. Even when combined, they do not come close to representing Pliny's full work of 37 books: the received text is depended on the more recent '' recentiores'' and the relationship between the vetustiores and recentiores within the stemma codicum is not fully understood.

The manuscripts correspond with the Northumbrian Golden Age and

The oldest surviving manuscripts of the Naturalis are known as '' vetustiores'' ("older ones"), all dating from the early 8th to 9th centuries. Even when combined, they do not come close to representing Pliny's full work of 37 books: the received text is depended on the more recent '' recentiores'' and the relationship between the vetustiores and recentiores within the stemma codicum is not fully understood.

The manuscripts correspond with the Northumbrian Golden Age and

Even when combined, the vetustiores do not come close to representing Pliny's full work of 37 books: instead the Textual criticism, prototype manuscripts ('' recentiores)'' all descend from a parallel branch of the stemma. Manuscripts DGV are the now separated sections of what was once a complete edition of books 1-37. The recentiores were used for the critical editions by Les Belles Lettres.

Even when combined, the vetustiores do not come close to representing Pliny's full work of 37 books: instead the Textual criticism, prototype manuscripts ('' recentiores)'' all descend from a parallel branch of the stemma. Manuscripts DGV are the now separated sections of what was once a complete edition of books 1-37. The recentiores were used for the critical editions by Les Belles Lettres.

The first topic covered is Astronomy, in Book II. Pliny starts with the known universe, roundly criticising attempts at cosmology as madness, including the view that there are countless other worlds than the Earth. He concurs with the four (Aristotelian) elements, fire, earth, air and water, and records the seven Classical planet, "planets" including the Sun and Moon. The Earth is a sphere, suspended in the middle of space. He considers it a weakness to try to find the shape and form of God, or to suppose that such a being would care about human affairs. He mentions eclipses, but considers Hipparchus's almanac grandiose for seeming to know how Nature works. He cites Posidonius's estimate that the Moon is 230,000 miles away. He describes comets, noting that only Aristotle has recorded seeing more than one at once.

Book II continues with natural meteorological events lower in the sky, including the winds, weather, whirlwinds, lightning, and rainbows. He returns to astronomical facts such as the effect of longitude on time of sunrise and sunset, the variation of the Sun's elevation with latitude (affecting time-telling by sundials), and the variation of day length with latitude.

The first topic covered is Astronomy, in Book II. Pliny starts with the known universe, roundly criticising attempts at cosmology as madness, including the view that there are countless other worlds than the Earth. He concurs with the four (Aristotelian) elements, fire, earth, air and water, and records the seven Classical planet, "planets" including the Sun and Moon. The Earth is a sphere, suspended in the middle of space. He considers it a weakness to try to find the shape and form of God, or to suppose that such a being would care about human affairs. He mentions eclipses, but considers Hipparchus's almanac grandiose for seeming to know how Nature works. He cites Posidonius's estimate that the Moon is 230,000 miles away. He describes comets, noting that only Aristotle has recorded seeing more than one at once.

Book II continues with natural meteorological events lower in the sky, including the winds, weather, whirlwinds, lightning, and rainbows. He returns to astronomical facts such as the effect of longitude on time of sunrise and sunset, the variation of the Sun's elevation with latitude (affecting time-telling by sundials), and the variation of day length with latitude.

Zoology is discussed in Books VIII to XI. The entries begin with a discussion of terrestrial animals, taken to include mammals, reptiles, amphibians, and an assortment of mythological creatures recognized as real animals (e.g. dragons). The elephant, and the lion are described in detail, with accounts of behaviors, taming, and battles with bestiarii referenced. Other species are listed in relation to their geographic ranges, for example India and the far north. Domestic dogs, horses, and livestock feature prominently, with elaboration on their uses to humans, for example the types of wool produced by sheep and the cloth created from them.

From there, "the natural history of fishes" is outlined. Pliny identified all aquatic animals as "fishes", making distinctions between those "with red blood" (cetaceans and traditional fishes) and those "without blood", the latter classified between "soft fishes" (cephalopods), those with "thin crusts" (e.g. crustaceans & sea urchins), and those enclosed with hard shells (e.g. bivalves & gastropods). As well, jellies are described with "bodies of a third nature" as a mix of animal and plant. The encyclopedia mentions different sources of purple dye, particularly the murex snail, the highly prized source of Tyrian purple, as well as the value and origin of the pearl and the invention of fish farming and oyster farming. The keeping of aquariums was a popular pastime of the rich, and Pliny provides anecdotes of the problems of owners becoming too closely attached to their fish.

Birds are described next, starting with the ostrich and the mythical phoenix. Much detail is spent with eagles, which are "looked upon as the most noble", followed by the other birds of prey. Pliny classifies birds based on the structure of their feet, noting the connection between their shape and the diet/habitat associated with their owners. He praises the song of the nightingale, and considers the connection between birdsong and omens. Bats are listed among the other "winged animals" but are recognized as viviparous and nurse their young with milk. This is followed by an extensive overview of animal reproduction, senses, and feeding & resting behaviour.

Finally, insects and other arthropods are listed. Pliny devotes considerable space to bees, which he admires for their industry, organisation, and honey, discussing the significance of the queen bee and the use of smoke by beekeepers at the hive to collect honeycomb. As well, the silkworm and silk production are described, the discovery of which is attributed to a woman named Pamphile (no reference is made to China). The coverage of zoology ends with an account of animal anatomy.

Pliny correctly identifies the origin of amber as the fossilised resin of pine trees. Evidence cited includes the fact that some samples exhibit encapsulated insects, a feature readily explained by the presence of a viscous resin. He mentions how it exerts a charge when rubbed.

Zoology is discussed in Books VIII to XI. The entries begin with a discussion of terrestrial animals, taken to include mammals, reptiles, amphibians, and an assortment of mythological creatures recognized as real animals (e.g. dragons). The elephant, and the lion are described in detail, with accounts of behaviors, taming, and battles with bestiarii referenced. Other species are listed in relation to their geographic ranges, for example India and the far north. Domestic dogs, horses, and livestock feature prominently, with elaboration on their uses to humans, for example the types of wool produced by sheep and the cloth created from them.

From there, "the natural history of fishes" is outlined. Pliny identified all aquatic animals as "fishes", making distinctions between those "with red blood" (cetaceans and traditional fishes) and those "without blood", the latter classified between "soft fishes" (cephalopods), those with "thin crusts" (e.g. crustaceans & sea urchins), and those enclosed with hard shells (e.g. bivalves & gastropods). As well, jellies are described with "bodies of a third nature" as a mix of animal and plant. The encyclopedia mentions different sources of purple dye, particularly the murex snail, the highly prized source of Tyrian purple, as well as the value and origin of the pearl and the invention of fish farming and oyster farming. The keeping of aquariums was a popular pastime of the rich, and Pliny provides anecdotes of the problems of owners becoming too closely attached to their fish.

Birds are described next, starting with the ostrich and the mythical phoenix. Much detail is spent with eagles, which are "looked upon as the most noble", followed by the other birds of prey. Pliny classifies birds based on the structure of their feet, noting the connection between their shape and the diet/habitat associated with their owners. He praises the song of the nightingale, and considers the connection between birdsong and omens. Bats are listed among the other "winged animals" but are recognized as viviparous and nurse their young with milk. This is followed by an extensive overview of animal reproduction, senses, and feeding & resting behaviour.

Finally, insects and other arthropods are listed. Pliny devotes considerable space to bees, which he admires for their industry, organisation, and honey, discussing the significance of the queen bee and the use of smoke by beekeepers at the hive to collect honeycomb. As well, the silkworm and silk production are described, the discovery of which is attributed to a woman named Pamphile (no reference is made to China). The coverage of zoology ends with an account of animal anatomy.

Pliny correctly identifies the origin of amber as the fossilised resin of pine trees. Evidence cited includes the fact that some samples exhibit encapsulated insects, a feature readily explained by the presence of a viscous resin. He mentions how it exerts a charge when rubbed.

Fraud and forgery are described in detail; in particular coin counterfeiting by mixing copper with silver, or even admixture with iron. Tests had been developed for counterfeit coins and proved very popular with the victims, mostly ordinary people. He deals with the liquid metal mercury, also found in silver mines. He records that it is toxic, and Amalgam (chemistry), amalgamates with gold, so is used for refining and extracting that metal. He says mercury is used for gilding copper, while antimony is found in silver mines and is used as an eyebrow Cosmetics, cosmetic.

The main ore of mercury is cinnabar, long used as a pigment by painters. He says that the colour is similar to ''scolecium'', probably the Kermes (dye), kermes insect. The dust is very toxic, so workers handling the material wear face masks of bladder skin. Copper and bronze are, says Pliny, most famous for their use in statues including colossi, gigantic statues as tall as towers, the most famous being the Colossus of Rhodes. He personally saw the massive statue of Nero in Rome, which was removed after the emperor's death. The face of the statue was modified shortly after Nero's death during Vespasian's reign, to make it a statue of Sol (Roman mythology), Sol. Hadrian moved it, with the help of the architect Decrianus and 24 elephants, to a position next to the Flavian Amphitheatre (now called the Colosseum).

Pliny gives a special place to iron, distinguishing the hardness of steel from what is now called wrought iron, a softer grade. He is scathing about the use of iron in warfare.

Fraud and forgery are described in detail; in particular coin counterfeiting by mixing copper with silver, or even admixture with iron. Tests had been developed for counterfeit coins and proved very popular with the victims, mostly ordinary people. He deals with the liquid metal mercury, also found in silver mines. He records that it is toxic, and Amalgam (chemistry), amalgamates with gold, so is used for refining and extracting that metal. He says mercury is used for gilding copper, while antimony is found in silver mines and is used as an eyebrow Cosmetics, cosmetic.

The main ore of mercury is cinnabar, long used as a pigment by painters. He says that the colour is similar to ''scolecium'', probably the Kermes (dye), kermes insect. The dust is very toxic, so workers handling the material wear face masks of bladder skin. Copper and bronze are, says Pliny, most famous for their use in statues including colossi, gigantic statues as tall as towers, the most famous being the Colossus of Rhodes. He personally saw the massive statue of Nero in Rome, which was removed after the emperor's death. The face of the statue was modified shortly after Nero's death during Vespasian's reign, to make it a statue of Sol (Roman mythology), Sol. Hadrian moved it, with the help of the architect Decrianus and 24 elephants, to a position next to the Flavian Amphitheatre (now called the Colosseum).

Pliny gives a special place to iron, distinguishing the hardness of steel from what is now called wrought iron, a softer grade. He is scathing about the use of iron in warfare.

In the last two books of the work (Books XXXVI and XXXVII), Pliny describes many different

In the last two books of the work (Books XXXVI and XXXVII), Pliny describes many different

Volume I

Books 1–2 # L352

Volume II

Books 3–7 # L353) iarchive:L353PlinyNaturalHistoryIII811/page/n7/mode/2up, Volume III. Books 8–11 # L370

Volume IV

Books 12–16 # L371) iarchive:L371PlinyNaturalHistoryV1719, Volume V. Books 17–19 # L392) iarchive:L392PlinyNaturalHistoryVI2023, Volume VI. Books 20–23 # L393) iarchive:L393PlinyNaturalHistoryVII2427OndexOfPlants, Volume VII. Books 24–27. Index of Plants # L418

Volume VIII.

Books 28–32. Index of Fishes # L394) iarchive:natural-history-in-ten-volumes.-vol.-9-libri-xxxiii-xxxv-loeb-394, Volume IX. Books 33–35 # L419) iarchive:natural-history-in-ten-volumes.-vol.-10-libri-xxxvi-xxxvii-loeb-419, Volume X. Books 36–37 Collection Budé (Latin & French): * Livre I: Vue d'ensemble des 36 livres * Livre II: Cosmologie, astronomie et géologie * Livre III: Géographie des mondes connus: Italie, Espagne, Narbonnaise * (This was the most recently published edition, finally completing the Editorial collection, collection) * Livre V, 1re partie: Géographie: L'Afrique du Nord * Livre VI, 2e partie: L'Asie centrale et orientale. L'Inde * Livre VI, 4e partie: L'Asie africaine sauf l'Egypte. Les dimensions et les climats du monde habité * Livre VII: De l'homme * Livre VIII: Des animaux terrestres * Livre IX: Des Animaux marins * Livre X: Des Animaux ailés * Livre XI: Des Insectes. Des Parties du corps * (This was the first published volume, beginning the series.) * Livre XII: Des Arbres * Livre XIII: Des arbres exotiques * Livre XIV: Des Arbres fruitiers : la vigne * Livre XV: De la Nature des arbres fruitiers * Livre XVI: Caractères des arbres sauvages * Livre XVII: Caractères des arbres cultivés * Livre XVIII: De l'Agriculture * Livre XIX: Nature du lin et horticulture * Livre XX: Remèdes tirés des plantes de jardins * Livre XXI: Nature des fleurs et des guirlandes * Livre XXII: Importance des plantes * Livre XXIII: Remèdes tirés des arbres cultivés * Livre XXIV: Remèdes tirés des arbres sauvages * Livre XXV: Nature des plantes naissant spontanément et des plantes découvertes par les hommes * Livre XXVI: Remèdes par espèces * Livre XXVII: Remèdes par espèces * Livre XXVIII: Remèdes tirés des animaux * Livre XXIX: Remèdes tirés des animaux *Livre XXX: Remèdes tirés des animaux - Magie *Livre XXXI: Remèdes tirés des eaux *Livre XXXII: Remèdes tirés des animaux aquatiques *Livre XXXIII: Nature des métaux *Livre XXXIV: Des Métaux et de la sculpture *Livre XXXV: De la Peinture *Livre XXXVI: Nature des pierres *Livre XXXVII: Des pierres précieuses English Translations: *

Complete Latin text at LacusCurtius

Complete Latin text with translation tools at Perseus Digital Library

. Pliny the Elder. Johannes de Spira. Venice. before 18 September 1469.

a

Corning Museum of Glass

(Once owned by the Earls of Pembroke)

. Pliny the Elder.

Karl Friedrich Theodor Mayhoff. Lipsiae. Teubner. 1906. # English

by Philemon Holland, 1601

Second English translation

by John Bostock (physician), John Bostock and Henry Thomas Riley, 1855; complete, with index * * Translated by Harris Rackham, H. Rackham (vols. 1–5, 9) and W.H.S. Jones (vols. 6–8) and D.E. Eichholz (vol. 10) Harvard University Press, Massachusetts and William Heinemann, London; 1949–1954.

All Six Volumes free at Project Gutenberg

Italian *

Article on Pliny by Jona Lendering, with detailed table of contents of the ''Natural History''

Pliny the Elder's World Database

{{Authority control 1st-century books in Latin Ancient Roman medicine Geoponici Incunabula Encyclopedias in Latin Prose texts in Latin Natural history books Encyclopedias in classical antiquity Phoenicia in ancient sources History of magic

Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/24 79), known in English as Pliny the Elder ( ), was a Roman Empire, Roman author, Natural history, naturalist, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the Roman emperor, emperor Vesp ...

. The largest single work to have survived from the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

to the modern day, the ''Natural History'' compiles information gleaned from other ancient authors. Despite the work's title, its subject area is not limited to what is today understood by natural history

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

; Pliny himself defines his scope as "the natural world, or life". It is encyclopedic in scope, but its structure is not like that of a modern encyclopedia

An encyclopedia is a reference work or compendium providing summaries of knowledge, either general or special, in a particular field or discipline. Encyclopedias are divided into article (publishing), articles or entries that are arranged Alp ...

. It is the only work by Pliny to have survived, and the last that he published. He published the first 10 books in AD 77, but had not made a final revision of the remainder at the time of his death during the AD 79 eruption of Vesuvius. The rest was published posthumously by Pliny's nephew, Pliny the Younger

Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus (born Gaius Caecilius or Gaius Caecilius Cilo; 61 – ), better known in English as Pliny the Younger ( ), was a lawyer, author, and magistrate of Ancient Rome. Pliny's uncle, Pliny the Elder, helped raise and e ...

.

The work is divided into 37 books, organised into 10 volumes. These cover topics including astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest includ ...

, mathematics

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

, geography

Geography (from Ancient Greek ; combining 'Earth' and 'write', literally 'Earth writing') is the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena of Earth. Geography is an all-encompassing discipline that seeks an understanding o ...

, ethnography

Ethnography is a branch of anthropology and the systematic study of individual cultures. It explores cultural phenomena from the point of view of the subject of the study. Ethnography is also a type of social research that involves examining ...

, anthropology

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, society, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including archaic humans. Social anthropology studies patterns of behav ...

, human physiology

Physiology (; ) is the science, scientific study of function (biology), functions and mechanism (biology), mechanisms in a life, living system. As a branches of science, subdiscipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ syst ...

, zoology

Zoology ( , ) is the scientific study of animals. Its studies include the anatomy, structure, embryology, Biological classification, classification, Ethology, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinction, extinct, and ...

, botany

Botany, also called plant science, is the branch of natural science and biology studying plants, especially Plant anatomy, their anatomy, Plant taxonomy, taxonomy, and Plant ecology, ecology. A botanist or plant scientist is a scientist who s ...

, agriculture

Agriculture encompasses crop and livestock production, aquaculture, and forestry for food and non-food products. Agriculture was a key factor in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created ...

, horticulture

Horticulture (from ) is the art and science of growing fruits, vegetables, flowers, trees, shrubs and ornamental plants. Horticulture is commonly associated with the more professional and technical aspects of plant cultivation on a smaller and mo ...

, pharmacology

Pharmacology is the science of drugs and medications, including a substance's origin, composition, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, therapeutic use, and toxicology. More specifically, it is the study of the interactions that occur betwee ...

, mining

Mining is the Resource extraction, extraction of valuable geological materials and minerals from the surface of the Earth. Mining is required to obtain most materials that cannot be grown through agriculture, agricultural processes, or feasib ...

, mineralogy

Mineralogy is a subject of geology specializing in the scientific study of the chemistry, crystal structure, and physical (including optical mineralogy, optical) properties of minerals and mineralized artifact (archaeology), artifacts. Specific s ...

, sculpture

Sculpture is the branch of the visual arts that operates in three dimensions. Sculpture is the three-dimensional art work which is physically presented in the dimensions of height, width and depth. It is one of the plastic arts. Durable sc ...

, art

Art is a diverse range of cultural activity centered around ''works'' utilizing creative or imaginative talents, which are expected to evoke a worthwhile experience, generally through an expression of emotional power, conceptual ideas, tec ...

, and precious stones

A gemstone (also called a fine gem, jewel, precious stone, semiprecious stone, or simply gem) is a piece of mineral crystal which, when cut or polished, is used to make jewellery, jewelry or other adornments. Certain Rock (geology), rocks (such ...

.

Pliny's ''Natural History'' became a model for later encyclopedias and scholarly works as a result of its breadth of subject matter, its referencing of original authors, and its index

Index (: indexes or indices) may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Fictional entities

* Index (''A Certain Magical Index''), a character in the light novel series ''A Certain Magical Index''

* The Index, an item on the Halo Array in the ...

.

Overview

Vespasian

Vespasian (; ; 17 November AD 9 – 23 June 79) was Roman emperor from 69 to 79. The last emperor to reign in the Year of the Four Emperors, he founded the Flavian dynasty, which ruled the Empire for 27 years. His fiscal reforms and consolida ...

. Much of his writing was done at night; daytime hours were spent working for the emperor, as he explains in the dedicatory preface addressed to Vespasian's elder son, the future emperor Titus

Titus Caesar Vespasianus ( ; 30 December 39 – 13 September AD 81) was Roman emperor from 79 to 81. A member of the Flavian dynasty, Titus succeeded his father Vespasian upon his death, becoming the first Roman emperor ever to succeed h ...

, with whom he had served in the army (and to whom the work is dedicated). As for the nocturnal hours spent writing, these were seen not as a loss of sleep but as an addition to life, for as he states in the preface, ''Vita vigilia est'', "to be alive is to be watchful", in a military metaphor of a sentry keeping watch in the night.''Natural History''. Dedication to Titus: C. Plinius Secundus to his Friend Titus Vespasian Pliny claims to be the only Roman ever to have undertaken such a work, in his prayer for the blessing of the universal mother:

Hail to thee, Nature, thou parent of all things! and do thou deign to show thy favour unto me, who, alone of all the citizens of Rome, have, in thy every department, thus made known thy praise.The ''Natural History'' is encyclopaedic in scope, but its format is unlike a modern

encyclopaedia

An encyclopedia is a reference work or compendium providing summaries of knowledge, either general or special, in a particular field or discipline. Encyclopedias are divided into articles or entries that are arranged alphabetically by artic ...

. However, it does have structure: Pliny uses Aristotle's division of nature (animal, vegetable, mineral) to recreate the natural world in literary form. Rather than presenting compartmentalised, stand-alone entries arranged alphabetically, Pliny's ordered natural landscape is a coherent whole, offering the reader a guided tour: "a brief excursion under our direction among the whole of the works of nature ..." The work is unified but varied: "My subject is the world of nature ... or in other words, life," he tells Titus.

Nature for Pliny was divine, a pantheistic

Pantheism can refer to a number of Philosophy, philosophical and Religion, religious beliefs, such as the belief that the universe is God, or panentheism, the belief in a non-corporeal divine intelligence or God out of which the universe arise ...

concept inspired by the Stoic philosophy

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

, which underlies much of his thought, but the deity in question was a goddess whose main purpose was to serve the human race: "nature, that is life" is human life in a natural landscape. After an initial survey of cosmology

Cosmology () is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe, the cosmos. The term ''cosmology'' was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount's ''Glossographia'', with the meaning of "a speaking of the wo ...

and geography

Geography (from Ancient Greek ; combining 'Earth' and 'write', literally 'Earth writing') is the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena of Earth. Geography is an all-encompassing discipline that seeks an understanding o ...

, Pliny starts his treatment of animals with the human race, "for whose sake great Nature appears to have created all other things". This teleological

Teleology (from , and )Partridge, Eric. 1977''Origins: A Short Etymological Dictionary of Modern English'' London: Routledge, p. 4187. or finalityDubray, Charles. 2020 912Teleology. In ''The Catholic Encyclopedia'' 14. New York: Robert Applet ...

view of nature was common in antiquity and is crucial to the understanding of the ''Natural History''. The components of nature are not just described in and for themselves, but also with a view to their role in human life. Pliny devotes a number of the books to plants, with a focus on their medicinal value; the books on minerals include descriptions of their uses in architecture

Architecture is the art and technique of designing and building, as distinguished from the skills associated with construction. It is both the process and the product of sketching, conceiving, planning, designing, and construction, constructi ...

, sculpture

Sculpture is the branch of the visual arts that operates in three dimensions. Sculpture is the three-dimensional art work which is physically presented in the dimensions of height, width and depth. It is one of the plastic arts. Durable sc ...

, art

Art is a diverse range of cultural activity centered around ''works'' utilizing creative or imaginative talents, which are expected to evoke a worthwhile experience, generally through an expression of emotional power, conceptual ideas, tec ...

, and jewellery

Jewellery (or jewelry in American English) consists of decorative items worn for personal adornment such as brooches, ring (jewellery), rings, necklaces, earrings, pendants, bracelets, and cufflinks. Jewellery may be attached to the body or the ...

. Pliny's premise is distinct from modern ecological

Ecology () is the natural science of the relationships among living organisms and their environment. Ecology considers organisms at the individual, population, community, ecosystem, and biosphere levels. Ecology overlaps with the closely re ...

theories, reflecting the prevailing sentiment of his time.

Pliny's work frequently reflects Rome's imperial expansion, which brought new and exciting things to the capital: exotic eastern spices, strange animals to be put on display or herded into the arena, even the alleged phoenix sent to the emperor Claudius

Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; ; 1 August 10 BC – 13 October AD 54), or Claudius, was a Roman emperor, ruling from AD 41 to 54. A member of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, Claudius was born to Nero Claudius Drusus, Drusus and Ant ...

in AD 47 – although, as Pliny admits, this was generally acknowledged to be a fake. Pliny repeated Aristotle's maxim that Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

was always producing something new. Nature's variety and versatility were claimed to be infinite: "When I have observed nature she has always induced me to deem no statement about her incredible." This led Pliny to recount rumours of strange peoples on the edges of the world. These monstrous races – the Cynocephali or Dog-Heads, the Sciapodae, whose single foot could act as a sunshade, the mouthless Astomi, who lived on scents – were not strictly new. They had been mentioned in the fifth century BC by Greek historian Herodotus

Herodotus (; BC) was a Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus (now Bodrum, Turkey), under Persian control in the 5th century BC, and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria, Italy. He wrote the '' Histori ...

(whose history was a broad mixture of myths

Myth is a genre of folklore consisting primarily of narratives that play a fundamental role in a society. For scholars, this is very different from the vernacular usage of the term "myth" that refers to a belief that is not true. Instead, the ...

, legend

A legend is a genre of folklore that consists of a narrative featuring human actions, believed or perceived to have taken place in human history. Narratives in this genre may demonstrate human values, and possess certain qualities that give the ...

s, and facts), but Pliny made them better known.

"As full of variety as nature itself", stated Pliny's nephew, Pliny the Younger

Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus (born Gaius Caecilius or Gaius Caecilius Cilo; 61 – ), better known in English as Pliny the Younger ( ), was a lawyer, author, and magistrate of Ancient Rome. Pliny's uncle, Pliny the Elder, helped raise and e ...

, and this verdict largely explains the appeal of the ''Natural History'' since Pliny's death in the Eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79

In 79 AD, Mount Vesuvius, a stratovolcano located in the modern-day region of Campania, erupted, causing one of the deadliest eruptions in history. Vesuvius violently ejected a cloud of super-heated tephra and gases to a height of , ejecting ...

. Pliny had gone to investigate the strange cloud – "shaped like an umbrella pine", according to his nephew – rising from the mountain.

The ''Natural History'' was one of the first ancient European texts to be printed, in Venice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

in 1469.Healy, 2004. Introduction:xxxix Philemon Holland's English translation of 1601 has influenced literature ever since.

Structure

The ''Natural History'' consists of 37 books. Pliny devised a ''summarium,'' or list of contents, at the beginning of the work that was later interpreted by modern printers as a table of contents. The table below is a summary based on modern names for topics.Production

Purpose

Pliny's purpose in writing the ''Natural History'' was to cover all learning and art so far as they are connected with nature or draw their materials from nature. He says:My subject is a barren one – the world of nature, or in other words life; and that subject in its least elevated department, and employing either rustic terms or foreign, nay barbarian words that actually have to be introduced with an apology. Moreover, the path is not a beaten highway of authorship, nor one in which the mind is eager to range: there is not one of us who has made the same venture, nor yet one among the Greeks who has tackled single-handed all departments of the subject.

Sources

Pliny studied the original authorities on each subject and took care to make excerpts from their pages. His ''indices auctorum'' sometimes list the authorities he actually consulted, though not exhaustively; in other cases, they cover the principal writers on the subject, whose names are borrowed second-hand from his immediate authorities. He acknowledges his obligations to his predecessors: "To own up to those who were the means of one's own achievements." In the preface, the author claims to have stated 20,000 facts gathered from some 2,000 books and from 100 select authors. The extant lists of his authorities cover more than 400, including 146 Roman and 327 Greek and other sources of information. The lists generally follow the order of the subject matter of each book. This has been shown in Heinrich Brunn's ''Disputatio'' (Bonn

Bonn () is a federal city in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia, located on the banks of the Rhine. With a population exceeding 300,000, it lies about south-southeast of Cologne, in the southernmost part of the Rhine-Ruhr region. This ...

, 1856).

One of Pliny's authorities is Marcus Terentius Varro

Marcus Terentius Varro (116–27 BCE) was a Roman polymath and a prolific author. He is regarded as ancient Rome's greatest scholar, and was described by Petrarch as "the third great light of Rome" (after Virgil and Cicero). He is sometimes call ...

. In the geographical books, Varro is supplemented by the topographical commentaries of Agrippa, which were completed by the emperor Augustus

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian (), was the founder of the Roman Empire, who reigned as the first Roman emperor from 27 BC until his death in A ...

; for his zoology

Zoology ( , ) is the scientific study of animals. Its studies include the anatomy, structure, embryology, Biological classification, classification, Ethology, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinction, extinct, and ...

, he relies largely on Aristotle and on Juba

Juba is the capital and largest city of South Sudan. The city is situated on the White Nile and also serves as the capital of the Central Equatoria, Central Equatoria State. It is the most recently declared national capital and had a populatio ...

, the scholarly Mauretania

Mauretania (; ) is the Latin name for a region in the ancient Maghreb. It extended from central present-day Algeria to the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, encompassing northern present-day Morocco, and from the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean in the ...

n king, ''studiorum claritate memorabilior quam regno'' (v. 16). Juba is one of his principal guides in botany; Theophrastus

Theophrastus (; ; c. 371 – c. 287 BC) was an ancient Greek Philosophy, philosopher and Natural history, naturalist. A native of Eresos in Lesbos, he was Aristotle's close colleague and successor as head of the Lyceum (classical), Lyceum, the ...

is also named in his Indices, and Pliny had translated Theophrastus's Greek into Latin. Another work by Theophrastus, '' On Stones'' was cited as a source on ores

Ore is natural Rock (geology), rock or sediment that contains one or more valuable minerals, typically including metals, concentrated above background levels, and that is economically viable to mine and process. The grade of ore refers to the ...

and mineral

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid substance with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.John P. Rafferty, ed. (2011): Mi ...

s. Pliny strove to use all the Greek histories available to him, such as Herodotus and Thucydides

Thucydides ( ; ; BC) was an Classical Athens, Athenian historian and general. His ''History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts Peloponnesian War, the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been d ...

, as well as the ''Bibliotheca Historica

''Bibliotheca historica'' (, ) is a work of Universal history (genre), universal history by Diodorus Siculus. It consisted of forty books, which were divided into three sections. The first six books are geographical in theme, and describe the h ...

'' of Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus or Diodorus of Sicily (; 1st century BC) was an ancient Greece, ancient Greek historian from Sicily. He is known for writing the monumental Universal history (genre), universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty ...

.

Working method

His nephew, Pliny the Younger, described the method that Pliny used to write the ''Natural History'':Pliny the Younger. Book 3, Letter V.To Baebius Macer

.'' in "Letters of Pliny the Younger" with introduction by John B. Firth.

Does it surprise you that a busy man found time to finish so many volumes, many of which deal with such minute details?... He used to begin to study at night on the Festival of Vulcan, not for luck but from his love of study, long before dawn; in winter he would commence at the seventh hour... He could sleep at call, and it would come upon him and leave him in the middle of his work. Before daybreak he would go to Vespasian – for he too was a night-worker – and then set about his official duties. On his return home he would again give to study any time that he had free. Often in summer after taking a meal, which with him, as in the old days, was always a simple and light one, he would lie in the sun if he had any time to spare, and a book would be read aloud, from which he would take notes and extracts.Pliny the Younger told the following anecdote illustrating his uncle's enthusiasm for study:

After dinner a book would be read aloud, and he would take notes in a cursory way. I remember that one of his friends, when the reader pronounced a word wrongly, checked him and made him read it again, and my uncle said to him, "Did you not catch the meaning?" When his friend said "yes," he remarked, "Why then did you make him turn back? We have lost more than ten lines through your interruption." So jealous was he of every moment lost.

Style

Pliny's writing style emulates that of Seneca. It aims less at clarity and vividness than at epigrammatic point. It contains manyantitheses

Antithesis (: antitheses; Greek for "setting opposite", from "against" and "placing") is used in writing or speech either as a proposition that contrasts with or reverses some previously mentioned proposition, or when two opposites are introdu ...

, questions, exclamations, tropes, metaphor

A metaphor is a figure of speech that, for rhetorical effect, directly refers to one thing by mentioning another. It may provide, or obscure, clarity or identify hidden similarities between two different ideas. Metaphors are usually meant to cr ...

s, and other mannerism

Mannerism is a style in European art that emerged in the later years of the Italian High Renaissance around 1520, spreading by about 1530 and lasting until about the end of the 16th century in Italy, when the Baroque style largely replaced it ...

s of the Silver Age

The Ages of Man are the historical stages of human existence according to Greek mythology and its subsequent interpretatio romana, Roman interpretation.

Both Hesiod and Ovid offered accounts of the successive ages of humanity, which tend to pr ...

. His sentence structure is often loose and straggling. There is heavy use of the ablative absolute, and ablative phrases are often appended in a kind of vague "apposition" to express the author's own opinion of an immediately previous statement, e.g.,''Natural History'' XXXV:80

Publication history

First publication

Pliny wrote the first ten books in AD 77, and was engaged on revising the rest during the two remaining years of his life. The work was probably published with little revision by the author's nephew Pliny the Younger, who, when telling the story of a tame dolphin and describing the floating islands of the Vadimonian Lake thirty years later, has apparently forgotten that both are to be found in his uncle's work. He describes the as a ''Naturae historia'' and characterises it as a "work that is learned and full of matter, and as varied as nature herself." The absence of the author's final revision may explain many errors, including why the text is as John Healy writes "disjointed, discontinuous and not in a logical order"; and as early as 1350,Petrarch

Francis Petrarch (; 20 July 1304 – 19 July 1374; ; modern ), born Francesco di Petracco, was a scholar from Arezzo and poet of the early Italian Renaissance, as well as one of the earliest Renaissance humanism, humanists.

Petrarch's redis ...

complained about the corrupt state of the text, referring to copying errors made between the ninth and eleventh centuries.

Manuscripts

About the middle of the 3rd century, an abstract of the geographical portions of Pliny's work was produced by

About the middle of the 3rd century, an abstract of the geographical portions of Pliny's work was produced by Solinus

__NOTOC__

Gaius Julius Solinus, better known simply as Solinus, was a Latin grammarian, geographer, and compiler who probably flourished in the early 3rd century AD. Historical scholar Theodor Mommsen dates him to the middle of the 3rd century.

...

. Early in the 8th century, Bede

Bede (; ; 672/326 May 735), also known as Saint Bede, Bede of Jarrow, the Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable (), was an English monk, author and scholar. He was one of the most known writers during the Early Middle Ages, and his most f ...

, who admired Pliny's work, had access to a partial manuscript which he used in his " De natura rerum", especially the sections on meteorology

Meteorology is the scientific study of the Earth's atmosphere and short-term atmospheric phenomena (i.e. weather), with a focus on weather forecasting. It has applications in the military, aviation, energy production, transport, agricultur ...

and gems. However, Bede updated and corrected Pliny on the tides

Tides are the rise and fall of sea levels caused by the combined effects of the gravitational forces exerted by the Moon (and to a much lesser extent, the Sun) and are also caused by the Earth and Moon orbiting one another.

Tide tables ...

.

In total there are some 307 extant medieval manuscripts of the work, however this was narrowed down to just 17 for work on the critical edition by Detlefsen (1858-1904). Olsen (1985) published details of all of Pliny's manuscripts pre-1200, however did not attempt to reconstruct the stemma.

In 1141 Robert of Cricklade

Robert of Cricklade (–1174 × 1179) was a medieval English writer and prior of St Frideswide's Priory in Oxford. He was a native of Cricklade and taught before becoming a cleric. He wrote several theological works as well as a lost biography ...

wrote the ''Defloratio Historiae Naturalis Plinii Secundi'' consisting of nine books of selections taken from an ancient manuscript.

There are three independent classes of the stemma of the surviving Historia Naturalis manuscripts. These are divided into:

# Late Antique

An antique () is an item perceived as having value because of its aesthetic or historical significance, and often defined as at least 100 years old (or some other limit), although the term is often used loosely to describe any object that i ...

Codicies: 5th-6th centuries. None survive intact; all as palimpsest

In textual studies, a palimpsest () is a manuscript page, either from a scroll or a book, from which the text has been scraped or washed off in preparation for reuse in the form of another document. Parchment was made of lamb, calf, or kid ski ...

s or as recycled book bindings.

# Vetustiores (older): 8th-9th centuries

# Recentiores (younger): 9th century. From these descend all known later medieval recensions from the 11th-12th centuries up to 1469 printed edition.

The textual tradition/stemma was established by the German scholars J. Sillig, D. Detlefsen, L. von Jan, and K. Rück in the 19th century. Two Teubner Editions were published of 5 volumes; the first by L. von Jan (1856–78; see external links

An internal link is a type of hyperlink on a web page to another page or resource, such as an image or document, on the same website or domain. It is the opposite of an external link, a link that directs a user to content that is outside its d ...

) and the second by C. Mayhoff (1892-1906). The most recent critical editions were published by Les Belle Letters (1950-) however Reeve (2007) identifies multiple imperfections with these editions. There is currently no fully critical edition of the text and the stemma codicum is only partially understood.

Ancient Codices

5th century: all laterpalimpsest

In textual studies, a palimpsest () is a manuscript page, either from a scroll or a book, from which the text has been scraped or washed off in preparation for reuse in the form of another document. Parchment was made of lamb, calf, or kid ski ...

ed in France. None of the later recensions seem to descend from these manuscripts. All bare withness to only very small portions of the Naturalis, with the Codex Moneus (M) containing the largest surviving fragments from books 11-15. Manuscripts M, P and Pal. Chat. were originally written in Italy but palimpsested in France within a century without being copied and forming a tradition of their own.

Medieval Vetustiores

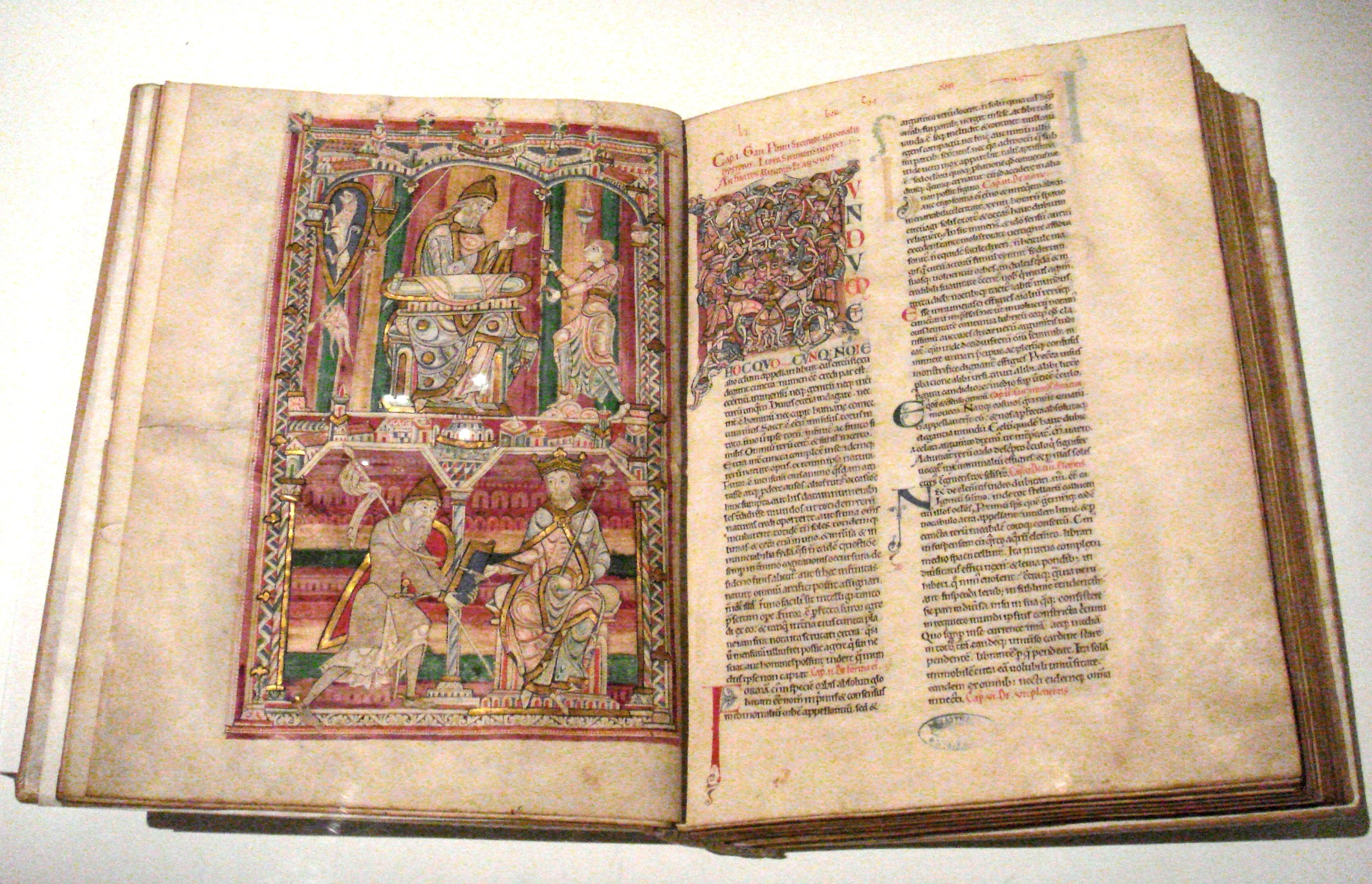

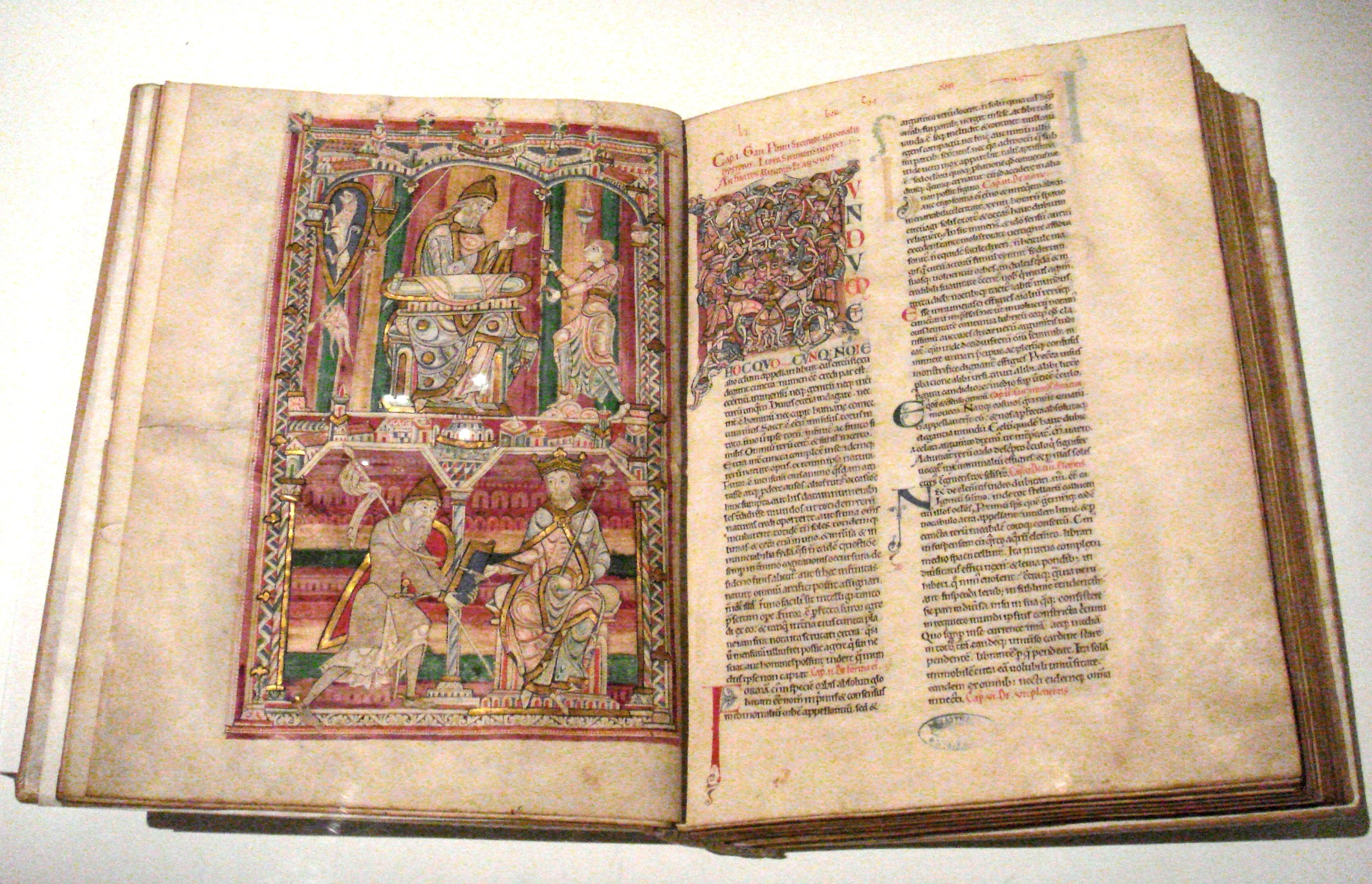

The oldest surviving manuscripts of the Naturalis are known as '' vetustiores'' ("older ones"), all dating from the early 8th to 9th centuries. Even when combined, they do not come close to representing Pliny's full work of 37 books: the received text is depended on the more recent '' recentiores'' and the relationship between the vetustiores and recentiores within the stemma codicum is not fully understood.

The manuscripts correspond with the Northumbrian Golden Age and

The oldest surviving manuscripts of the Naturalis are known as '' vetustiores'' ("older ones"), all dating from the early 8th to 9th centuries. Even when combined, they do not come close to representing Pliny's full work of 37 books: the received text is depended on the more recent '' recentiores'' and the relationship between the vetustiores and recentiores within the stemma codicum is not fully understood.

The manuscripts correspond with the Northumbrian Golden Age and Carolingian Renaissance

The Carolingian Renaissance was the first of three medieval renaissances, a period of cultural activity in the Carolingian Empire. Charlemagne's reign led to an intellectual revival beginning in the 8th century and continuing throughout the 9th ...

. VLF 4 (known as "the Leiden Pliny") was produced during Bede

Bede (; ; 672/326 May 735), also known as Saint Bede, Bede of Jarrow, the Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable (), was an English monk, author and scholar. He was one of the most known writers during the Early Middle Ages, and his most f ...

's lifetime at the School of York, the earliest surviving manuscript written north of the Alps

The Alps () are some of the highest and most extensive mountain ranges in Europe, stretching approximately across eight Alpine countries (from west to east): Monaco, France, Switzerland, Italy, Liechtenstein, Germany, Austria and Slovenia.

...

. At 41cm by 29cm it is amongst the largest medieval manuscripts written on parchment

Parchment is a writing material made from specially prepared Tanning (leather), untanned skins of animals—primarily sheep, calves and goats. It has been used as a writing medium in West Asia and Europe for more than two millennia. By AD 400 ...

, each leaf requiring a whole Hide (skin), hide (a total of at least 30 animals would have been required). However despite this there are no holes (insect bites), demonstrating its exceptional quality. Besides Zoomorphism, zoomorphic Capital letter, capitals, it is however plain and uniluminated for its size.

It was probably copied directly from an exemplar witten in Old Italic scripts, italic uncil script, requiring the Northumbria, Northumbrian scribe to devise new spacing and punctiontion. The Naturalis Historia was possibly known to Aldhelm and certainly to Bede

Bede (; ; 672/326 May 735), also known as Saint Bede, Bede of Jarrow, the Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable (), was an English monk, author and scholar. He was one of the most known writers during the Early Middle Ages, and his most f ...

, in constrast palimsested fates of the earlier continental manuscripts. Through Alcuin's role in the Carolingian Renaissance

The Carolingian Renaissance was the first of three medieval renaissances, a period of cultural activity in the Carolingian Empire. Charlemagne's reign led to an intellectual revival beginning in the 8th century and continuing throughout the 9th ...

, VLF 4 is throught to have been brought to the Frankish court at Palace of Aachen, Aachen around 796 AD, perhaps as a learning aid. However it ultimately did not spawn any surviving copies

Medieval Recentiores (Prototypes)

Even when combined, the vetustiores do not come close to representing Pliny's full work of 37 books: instead the Textual criticism, prototype manuscripts ('' recentiores)'' all descend from a parallel branch of the stemma. Manuscripts DGV are the now separated sections of what was once a complete edition of books 1-37. The recentiores were used for the critical editions by Les Belles Lettres.

Even when combined, the vetustiores do not come close to representing Pliny's full work of 37 books: instead the Textual criticism, prototype manuscripts ('' recentiores)'' all descend from a parallel branch of the stemma. Manuscripts DGV are the now separated sections of what was once a complete edition of books 1-37. The recentiores were used for the critical editions by Les Belles Lettres.

Later medieval recensions

Manuscript E appears to have been widely copied in the 11th and 12th centuries. Bibliothèque nationale de France, BnF Lat. 6797 (late 12th) is considered to preserve elements of a parallel tradition by Reynolds (1983) but Reeve (2007) places it as a descendant of F.Printed copies

The work was one of the first classical manuscripts to be printed, at Venice in 1469 by Johann and Wendelin of Speyer, but John F. Healy described the translation as "distinctly imperfect". A copy printed in 1472 by Nicolas Jenson of Venice is held in the library at Wells Cathedral.Translations

Philemon Holland made an influential translation of much of the work into English in 1601. John Bostock (physician), John Bostock and H. T. Riley made a complete translation in 1855. The Penguin Books, Penguin edition was published in 1991 (reprinted by Penguin Classics in 2004), an abridged translation with an Introduction and notes by Healy.Topics

The ''Natural History'' is generally divided into the organic plants and animals and the inorganic matter, although there are frequent digressions in each section. The encyclopedia also notes the uses made of all of these by the Romans. Its description of metals and minerals is valued for its detail in the history of science, being the most extensive compilation still available from the ancient world. Book I serves as Pliny's preface, explaining his approach and providing a table of contents.Astronomy

Geography

In Books III to VI, Pliny moves to the Earth itself. In Book III he covers the geography of the Iberian peninsula and Italy; Book IV covers Europe; Book V looks at Africa and Asia, while Book VI looks eastwards to the Black Sea, India and the Far East.Anthropology

Book VII discusses the human race, coveringanthropology

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, society, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including archaic humans. Social anthropology studies patterns of behav ...

and ethnography

Ethnography is a branch of anthropology and the systematic study of individual cultures. It explores cultural phenomena from the point of view of the subject of the study. Ethnography is also a type of social research that involves examining ...

, aspects of human physiology

Physiology (; ) is the science, scientific study of function (biology), functions and mechanism (biology), mechanisms in a life, living system. As a branches of science, subdiscipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ syst ...

and assorted matters such as the greatness of Julius Caesar, outstanding people such as Hippocrates and Asclepiades of Bithynia, Asclepiades, happiness and fortune.

Zoology

Zoology is discussed in Books VIII to XI. The entries begin with a discussion of terrestrial animals, taken to include mammals, reptiles, amphibians, and an assortment of mythological creatures recognized as real animals (e.g. dragons). The elephant, and the lion are described in detail, with accounts of behaviors, taming, and battles with bestiarii referenced. Other species are listed in relation to their geographic ranges, for example India and the far north. Domestic dogs, horses, and livestock feature prominently, with elaboration on their uses to humans, for example the types of wool produced by sheep and the cloth created from them.

From there, "the natural history of fishes" is outlined. Pliny identified all aquatic animals as "fishes", making distinctions between those "with red blood" (cetaceans and traditional fishes) and those "without blood", the latter classified between "soft fishes" (cephalopods), those with "thin crusts" (e.g. crustaceans & sea urchins), and those enclosed with hard shells (e.g. bivalves & gastropods). As well, jellies are described with "bodies of a third nature" as a mix of animal and plant. The encyclopedia mentions different sources of purple dye, particularly the murex snail, the highly prized source of Tyrian purple, as well as the value and origin of the pearl and the invention of fish farming and oyster farming. The keeping of aquariums was a popular pastime of the rich, and Pliny provides anecdotes of the problems of owners becoming too closely attached to their fish.

Birds are described next, starting with the ostrich and the mythical phoenix. Much detail is spent with eagles, which are "looked upon as the most noble", followed by the other birds of prey. Pliny classifies birds based on the structure of their feet, noting the connection between their shape and the diet/habitat associated with their owners. He praises the song of the nightingale, and considers the connection between birdsong and omens. Bats are listed among the other "winged animals" but are recognized as viviparous and nurse their young with milk. This is followed by an extensive overview of animal reproduction, senses, and feeding & resting behaviour.

Finally, insects and other arthropods are listed. Pliny devotes considerable space to bees, which he admires for their industry, organisation, and honey, discussing the significance of the queen bee and the use of smoke by beekeepers at the hive to collect honeycomb. As well, the silkworm and silk production are described, the discovery of which is attributed to a woman named Pamphile (no reference is made to China). The coverage of zoology ends with an account of animal anatomy.

Pliny correctly identifies the origin of amber as the fossilised resin of pine trees. Evidence cited includes the fact that some samples exhibit encapsulated insects, a feature readily explained by the presence of a viscous resin. He mentions how it exerts a charge when rubbed.

Zoology is discussed in Books VIII to XI. The entries begin with a discussion of terrestrial animals, taken to include mammals, reptiles, amphibians, and an assortment of mythological creatures recognized as real animals (e.g. dragons). The elephant, and the lion are described in detail, with accounts of behaviors, taming, and battles with bestiarii referenced. Other species are listed in relation to their geographic ranges, for example India and the far north. Domestic dogs, horses, and livestock feature prominently, with elaboration on their uses to humans, for example the types of wool produced by sheep and the cloth created from them.

From there, "the natural history of fishes" is outlined. Pliny identified all aquatic animals as "fishes", making distinctions between those "with red blood" (cetaceans and traditional fishes) and those "without blood", the latter classified between "soft fishes" (cephalopods), those with "thin crusts" (e.g. crustaceans & sea urchins), and those enclosed with hard shells (e.g. bivalves & gastropods). As well, jellies are described with "bodies of a third nature" as a mix of animal and plant. The encyclopedia mentions different sources of purple dye, particularly the murex snail, the highly prized source of Tyrian purple, as well as the value and origin of the pearl and the invention of fish farming and oyster farming. The keeping of aquariums was a popular pastime of the rich, and Pliny provides anecdotes of the problems of owners becoming too closely attached to their fish.

Birds are described next, starting with the ostrich and the mythical phoenix. Much detail is spent with eagles, which are "looked upon as the most noble", followed by the other birds of prey. Pliny classifies birds based on the structure of their feet, noting the connection between their shape and the diet/habitat associated with their owners. He praises the song of the nightingale, and considers the connection between birdsong and omens. Bats are listed among the other "winged animals" but are recognized as viviparous and nurse their young with milk. This is followed by an extensive overview of animal reproduction, senses, and feeding & resting behaviour.

Finally, insects and other arthropods are listed. Pliny devotes considerable space to bees, which he admires for their industry, organisation, and honey, discussing the significance of the queen bee and the use of smoke by beekeepers at the hive to collect honeycomb. As well, the silkworm and silk production are described, the discovery of which is attributed to a woman named Pamphile (no reference is made to China). The coverage of zoology ends with an account of animal anatomy.

Pliny correctly identifies the origin of amber as the fossilised resin of pine trees. Evidence cited includes the fact that some samples exhibit encapsulated insects, a feature readily explained by the presence of a viscous resin. He mentions how it exerts a charge when rubbed.

Botany

Botany is handled in Books XII to XVIII, with Theophrastus as one of Pliny's sources. The manufacture of papyrus and the various grades of papyrus available to Romans are described. Different types of trees and the properties of their wood are explained in Books XII to XIII. The vine, viticulture and varieties of grape are discussed in Book XIV, while Book XV covers the olive tree in detail, followed by other trees including the apple and pear, fig, cherry, Myrtus, myrtle and laurus nobilis, laurel, among others. Pliny gives special attention to spices, such as Black pepper, pepper, ginger, and cane sugar. He mentions different varieties of pepper, whose values are comparable with that of gold and silver, while sugar is noted only for its medicinal value. He is critical of perfumes: "Perfumes are the most pointless of luxuries, for pearls and jewels are at least passed on to one's heirs, and clothes last for a time, but perfumes lose their fragrance and perish as soon as they are used." He gives a summary of their ingredients, such as attar of roses, which he says is the most widely used base. Other substances added include myrrh, cinnamon, and amyris, balsam gum.Drugs, medicine and magic

A major section of the ''Natural History'', Books XX to XXIX, discusses matters related to medicine, especially plants that yield useful drugs. Pliny lists over 900 drugs, compared to 600 in Dioscorides's , 550 in Theophrastus, and 650 in Galen. The poppy and opium are mentioned; Pliny notes that opium induces sleep and can be fatal. Diseases and their treatment are covered in book XXVI. Pliny addresses magic (paranormal), magic in Book XXX. He is critical of the Magi, attacking astrology, and suggesting that magic originated in medicine, creeping in by pretending to offer health. He names Zoroaster of Ancient Persia as the source of magical ideas. He states that Pythagoras, Empedocles, Democritus and Plato all travelled abroad to learn magic, remarking that it was surprising anyone accepted the doctrines they brought back, and that medicine (of Hippocrates) and magic (of Democritus) should have flourished simultaneously at the time of the Peloponnesian War.Agriculture

The methods used to cultivate crops are described in Book XVIII. He praises Cato the Elder and his work ''De Agri Cultura'', which he uses as a primary source. Pliny's work includes discussion of all known cultivated crops and vegetables, as well as herbs and remedies derived from them. He describes machines used in cultivation and processing the crops. For example, he describes a simple mechanical reaper that cut the ears of wheat and barley without the straw and was pushed by oxen (Book XVIII, chapter 72). It is depicted on a bas-relief found at Trier from the later Roman period. He also describes how grain is ground using a pestle, a hand-mill, or a mill driven by water wheels, as found in List of Roman watermills, Roman water mills across the Empire.Metallurgy

Pliny extensively discusses metals starting with gold and silver (Book XXXIII), and then the base metals copper, mercury (element), mercury, lead, tin and iron, as well as their many alloys such as electrum, bronze, pewter, and steel (Book XXXIV). He is critical of greed for gold, such as the absurdity of using the metal for coins in the early Republic. He gives examples of the way rulers proclaimed their prowess by exhibiting gold looted from their campaigns, such as that by Claudius after conquering Britain, and tells the stories of Midas and Croesus. He discusses why gold is unique in its malleability and ductility, far greater than any other metal. The examples given are its ability to be beaten into fine foil (metal), foil with just one ounce producing 750 leaves four inches square. Fine gold wire can be woven into cloth, although imperial clothes usually combined it with natural fibres like wool. He once saw Agrippina the Younger, wife of Claudius, at a public show on the Fucine Lake involving a naval battle, wearing a military cloak made of gold. He rejects Herodotus's claims of Gold-digging ant, Indian gold obtained by ants or dug up by griffins in Scythia. Silver, he writes, does not occur in native form and has to be mined, usually occurring with lead ores. Spain produced the most silver in his time, many of the mines having been started by Hannibal. One of the largest had galleries running up to two miles into the mountain, while men worked day and night draining the mine in shifts. Pliny is probably referring to the reverse overshot water-wheels operated by treadmill and found in Roman mines. Britain, he says, is very rich in lead, which is found on the surface at many places, and thus very easy to extract; production was so high that a law was passed attempting to restrict mining. Fraud and forgery are described in detail; in particular coin counterfeiting by mixing copper with silver, or even admixture with iron. Tests had been developed for counterfeit coins and proved very popular with the victims, mostly ordinary people. He deals with the liquid metal mercury, also found in silver mines. He records that it is toxic, and Amalgam (chemistry), amalgamates with gold, so is used for refining and extracting that metal. He says mercury is used for gilding copper, while antimony is found in silver mines and is used as an eyebrow Cosmetics, cosmetic.

The main ore of mercury is cinnabar, long used as a pigment by painters. He says that the colour is similar to ''scolecium'', probably the Kermes (dye), kermes insect. The dust is very toxic, so workers handling the material wear face masks of bladder skin. Copper and bronze are, says Pliny, most famous for their use in statues including colossi, gigantic statues as tall as towers, the most famous being the Colossus of Rhodes. He personally saw the massive statue of Nero in Rome, which was removed after the emperor's death. The face of the statue was modified shortly after Nero's death during Vespasian's reign, to make it a statue of Sol (Roman mythology), Sol. Hadrian moved it, with the help of the architect Decrianus and 24 elephants, to a position next to the Flavian Amphitheatre (now called the Colosseum).

Pliny gives a special place to iron, distinguishing the hardness of steel from what is now called wrought iron, a softer grade. He is scathing about the use of iron in warfare.

Fraud and forgery are described in detail; in particular coin counterfeiting by mixing copper with silver, or even admixture with iron. Tests had been developed for counterfeit coins and proved very popular with the victims, mostly ordinary people. He deals with the liquid metal mercury, also found in silver mines. He records that it is toxic, and Amalgam (chemistry), amalgamates with gold, so is used for refining and extracting that metal. He says mercury is used for gilding copper, while antimony is found in silver mines and is used as an eyebrow Cosmetics, cosmetic.

The main ore of mercury is cinnabar, long used as a pigment by painters. He says that the colour is similar to ''scolecium'', probably the Kermes (dye), kermes insect. The dust is very toxic, so workers handling the material wear face masks of bladder skin. Copper and bronze are, says Pliny, most famous for their use in statues including colossi, gigantic statues as tall as towers, the most famous being the Colossus of Rhodes. He personally saw the massive statue of Nero in Rome, which was removed after the emperor's death. The face of the statue was modified shortly after Nero's death during Vespasian's reign, to make it a statue of Sol (Roman mythology), Sol. Hadrian moved it, with the help of the architect Decrianus and 24 elephants, to a position next to the Flavian Amphitheatre (now called the Colosseum).

Pliny gives a special place to iron, distinguishing the hardness of steel from what is now called wrought iron, a softer grade. He is scathing about the use of iron in warfare.

Mineralogy

In the last two books of the work (Books XXXVI and XXXVII), Pliny describes many different

In the last two books of the work (Books XXXVI and XXXVII), Pliny describes many different mineral

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid substance with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.John P. Rafferty, ed. (2011): Mi ...

s and gemstones, building on works by Theophrastus and other authors. The topic concentrates on the most valuable gemstones, and he criticises the obsession with luxury products such as engraved gems and hardstone carvings. He provides a thorough discussion of the properties of fluorspar, noting that it is carved into vases and other decorative objects. The account of magnetism includes the myth of Magnes the shepherd.

Pliny moves into crystallography and mineralogy

Mineralogy is a subject of geology specializing in the scientific study of the chemistry, crystal structure, and physical (including optical mineralogy, optical) properties of minerals and mineralized artifact (archaeology), artifacts. Specific s ...

, describing the octahedral shape of the diamond and recording that diamond dust is used by gem engravers to cut and polish other gems, owing to its great hardness. He states that rock crystal is valuable for its transparency and hardness, and can be carved into vessels and implements. He relates the story of a woman who owned a ladle made of the mineral, paying the sum of 150,000 sesterces for the item. Nero deliberately broke two crystal cups when he realised that he was about to be deposed, so denying their use to anyone else.

Pliny returns to the problem of fraud and the detection of false gems using several tests, including the scratch test, where counterfeit gems can be marked by a steel file, and genuine ones not. He refers to using one hard mineral to scratch another, presaging the Mohs hardness scale. Diamond sits at the top of the series because, Pliny says, it will scratch all other minerals.

Art history

Pliny's chapters on Roman art, Roman and Greek art are especially valuable because his work is virtually the only available classical source of information on the subject. In the history of art, the original Greek authorities are Duris of Samos, Xenocrates of Sicyon, and Antigonus of Carystus. The anecdotic element has been ascribed to Duris (XXXIV:61); the notices of the successive developments of art and the list of workers in bronze and painters to Xenocrates; and a large amount of miscellaneous information to Antigonus. Both Xenocrates and Antigonus are named in connection with Zeuxis and Parrhasius, Parrhasius (XXXV:68), while Antigonus is named in the indexes of XXXIII–XXXIV as a writer on the art of embossing metal, or working it in ornamental relief or Intaglio (sculpture), intaglio. Greek epigrams contribute their share in Pliny's descriptions of pictures and statues. One of the minor authorities for books XXXIV–XXXV is Heliodorus of Athens, the author of a work on the monuments of Athens. In the indices to XXXIII–XXXVI, an important place is assigned to Pasiteles of Naples, the author of a work in five volumes on famous works of art (XXXVI:40), probably incorporating the substance of the earlier Greek treatises; but Pliny's indebtedness to Pasiteles is denied by August Kalkmann, Kalkmann, who holds that Pliny used the chronological work of Apollodorus of Athens, as well as a current catalogue of artists. Pliny's knowledge of the Greek authorities was probably mainly due to Varro, whom he often quotes (e.g. XXXIV:56, XXXV:113, 156, XXXVI:17, 39, 41). For a number of items relating to works of art near the coast of Asia Minor and in the adjacent islands, Pliny was indebted to the general, statesman, orator and historian Mucianus, Gaius Licinius Mucianus, who died before 77. Pliny mentions the works of art collected by Vespasian in the Temple of Peace, Rome, Temple of Peace and in his other galleries (XXXIV:84), but much of his information about the position of such works in Rome is from books, not personal observation. The main merit of his account of ancient art, the only classical work of its kind, is that it is a compilation ultimately founded on the lost textbooks of Xenocrates and on the biographies of Duris of Samos, Duris and Antigonus. In several passages, he gives proof of independent observation (XXXIV:38, 46, 63, XXXV:17, 20, 116 seq.). He prefers the marble ''Laocoön and his Sons'' in the palace of Titus (widely believed to be the statue that is now in the Vatican City, Vatican) to all the pictures and bronzes in the world (XXXVI:37). The statue is attributed by Pliny to three sculptors from the island of Rhodes: Agesander of Rhodes, Agesander, Athenodoros (possibly son of Agesander) and Polydorus. In the temple near the Flaminian Circus, Pliny admires the Ares and the Aphrodite of Scopas, "which would suffice to give renown to any other spot". He adds:At Rome indeed the works of art are legion; besides, one effaces another from the memory and, however beautiful they may be, we are distracted by the overpowering claims of duty and business; for to admire art we need leisure and profound stillness (XXXVI:27).

Mining

Pliny provides lucid descriptions of Roman mining. He describes gold mining in detail, with large-scale use of water to scour alluvial gold deposits. The description probably refers to mining in Northern Spain, especially at the large Las Médulas site. Pliny describes methods of underground mining, including the use of fire-setting to attack the gold-bearing rock and so extract the ore. In another part of his work, Pliny describes the use of Underground mining#Mining techniques, undermining to gain access to the veins. Pliny was scathing about the search for precious metals and gemstones: "Gangadia or quartzite is considered the hardest of all things – except for the greed for gold, which is even more stubborn." Book XXXIV covers the base metals, their uses and their extraction. Copper mining is mentioned, using a variety of ores including copper pyrites and marcasite, some of the mining being underground, some on the surface. Iron mining is covered, followed by lead and tin.Reception

Medieval and early modern

The anonymous fourth-century compilation ''Medicina Plinii'' contains more than 1,100 pharmacology, pharmacological recipes, the vast majority of them from the ''Historia naturalis''; perhaps because Pliny's name was attached to it, it enjoyed huge popularity in the Middle Ages.D.R. Langlow, ''Medical Latin in the Roman Empire'' (Oxford University Press, 2000), p. 64. Isidore of Seville's ''Etymologiae'' (''The Etymologies'', –625) quotes from Pliny 45 times in Book XII alone; Books XII, XIII and XIV are all based largely on the ''Natural History''. Through Isidore, Vincent of Beauvais's ''Speculum Maius'' (''The Great Mirror'', c. 1235–1264) also used Pliny as a source for his own work. In this regard, Pliny's influence over the medieval period has been argued to be quite extensive. For example, one twentieth-century historian has argued that Pliny's reliance on book-based knowledge, and not direct observation, shaped intellectual life to the degree that it "stymie[d] the progress of western science". This sentiment can be observed in the early modern period when Niccolò Leoniceno's 1509 ''De Erroribus Plinii'' ("On Pliny's Errors") attacked Pliny for lacking a proper scientific method, unlike Theophrastus or Dioscorides, and for lacking knowledge of philosophy or medicine. Sir Thomas Browne expressed scepticism about Pliny's dependability in his 1646 ''Pseudodoxia Epidemica'':Modern