Philip Augustus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Philip II (21 August 1165 – 14 July 1223), byname Philip Augustus (french: Philippe Auguste), was

Philip was born in

Philip was born in

The royal

The royal

The death of Henry's fourth son,

The death of Henry's fourth son,

Philip travelled to the Holy Land to participate in the

Philip travelled to the Holy Land to participate in the

This agreement did not bring warfare to an end in France, however, since John's mismanagement of Aquitaine led the province to later rebel in 1200, a disturbance that Philip secretly encouraged. To disguise his ambitions, Philip invited John to a conference at Andely and then entertained him at Paris, and both times he committed to complying with the treaty. In 1202, disaffected patrons petitioned the French king to summon John to answer their charges in his capacity as John's feudal lord in France. John refused to appear, so Philip again took up Arthur of Brittany's claims to the English throne as well as betrothing him to his six-year-old daughter Marie. In retaliation John crossed over into Normandy and his forces soon captured Arthur. In 1203, Arthur disappeared, with most people believing that John had had him murdered. The outcry over Arthur's fate saw an increase in local opposition to John, which Philip used to his advantage. He took to the offensive and, apart from a five-month siege of Andely, swept all before him. After Andely surrendered, John fled to England. By the end of 1204, most of Normandy and the Angevin lands, including much of

This agreement did not bring warfare to an end in France, however, since John's mismanagement of Aquitaine led the province to later rebel in 1200, a disturbance that Philip secretly encouraged. To disguise his ambitions, Philip invited John to a conference at Andely and then entertained him at Paris, and both times he committed to complying with the treaty. In 1202, disaffected patrons petitioned the French king to summon John to answer their charges in his capacity as John's feudal lord in France. John refused to appear, so Philip again took up Arthur of Brittany's claims to the English throne as well as betrothing him to his six-year-old daughter Marie. In retaliation John crossed over into Normandy and his forces soon captured Arthur. In 1203, Arthur disappeared, with most people believing that John had had him murdered. The outcry over Arthur's fate saw an increase in local opposition to John, which Philip used to his advantage. He took to the offensive and, apart from a five-month siege of Andely, swept all before him. After Andely surrendered, John fled to England. By the end of 1204, most of Normandy and the Angevin lands, including much of

In 1208,

In 1208,

The French fleet proceeded first to

The French fleet proceeded first to  On 27 July 1214, the opposing armies suddenly discovered that they were in close proximity to one another, on the banks of a little tributary of the River Lys, near the bridge at

On 27 July 1214, the opposing armies suddenly discovered that they were in close proximity to one another, on the banks of a little tributary of the River Lys, near the bridge at

When Pope Innocent III called for a crusade against the "Albigensians," or

When Pope Innocent III called for a crusade against the "Albigensians," or

King of France

France was ruled by Monarch, monarchs from the establishment of the West Francia, Kingdom of West Francia in 843 until the end of the Second French Empire in 1870, with several interruptions.

Classical French historiography usually regards Cl ...

from 1180 to 1223. His predecessors had been known as kings of the Franks

The Franks ( la, Franci or ) were a group of Germanic peoples whose name was first mentioned in 3rd-century Roman sources, and associated with tribes between the Lower Rhine and the Ems River, on the edge of the Roman Empire.H. Schutz: Tools, ...

, but from 1190 onward, Philip became the first French monarch to style himself "King of France" (Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power ...

: ''rex Francie''). The son of King Louis VII

Louis VII (1120 – 18 September 1180), called the Younger, or the Young (french: link=no, le Jeune), was King of the Franks from 1137 to 1180. He was the son and successor of King Louis VI (hence the epithet "the Young") and married Duchess ...

and his third wife, Adela of Champagne, he was originally nicknamed ''Dieudonné'' (God-given) because he was a first son and born late in his father's life. Philip was given the epithet

An epithet (, ), also byname, is a descriptive term (word or phrase) known for accompanying or occurring in place of a name and having entered common usage. It has various shades of meaning when applied to seemingly real or fictitious people, di ...

"Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

" by the chronicler Rigord Rigord (Rigordus) ( 1150 – c. 1209) was a French chronicler. He was probably born near Alais in Languedoc, and became a physician.

After becoming a monk he entered the monastery of Argenteuil, and then that of Saint-Denis, and described hims ...

for having extended the crown lands of France

The crown lands, crown estate, royal domain or (in French) ''domaine royal'' (from demesne) of France were the lands, fiefs and rights directly possessed by the kings of France. While the term eventually came to refer to a territorial unit, th ...

so remarkably.

After decades of conflicts with the House of Plantagenet, Philip succeeded in putting an end to the Angevin Empire

The Angevin Empire (; french: Empire Plantagenêt) describes the possessions of the House of Plantagenet during the 12th and 13th centuries, when they ruled over an area covering roughly half of France, all of England, and parts of Ireland and ...

by defeating a coalition of his rivals at the Battle of Bouvines

The Battle of Bouvines was fought on 27 July 1214 near the town of Bouvines in the County of Flanders. It was the concluding battle of the Anglo-French War of 1213–1214. Although estimates on the number of troops vary considerably among mo ...

in 1214. This victory would have a lasting impact on western European politics: the authority of the French king became unchallenged, while the English King John was forced by his barons to assent to Magna Carta

(Medieval Latin for "Great Charter of Freedoms"), commonly called (also ''Magna Charta''; "Great Charter"), is a royal charter of rights agreed to by King John of England at Runnymede, near Windsor, Berkshire, Windsor, on 15 June 1215. ...

and deal with a rebellion against him aided by Philip's son Louis, the First Barons' War

The First Barons' War (1215–1217) was a civil war in the Kingdom of England in which a group of rebellious major landowners (commonly referred to as barons) led by Robert Fitzwalter waged war against King John of England. The conflict resu ...

. The military actions surrounding the Albigensian Crusade

The Albigensian Crusade or the Cathar Crusade (; 1209–1229) was a military and ideological campaign initiated by Pope Innocent III to eliminate Catharism in Languedoc, southern France. The Crusade was prosecuted primarily by the French crow ...

helped prepare the expansion of France southward. Philip did not participate directly in these actions, but he allowed his vassal

A vassal or liege subject is a person regarded as having a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch, in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe. While the subordinate party is called a vassal, the dominant party is called a suzerain. ...

s and knights to help carry them out.

Philip transformed France into the most prosperous and powerful country in Europe. He checked the power of the nobles and helped the towns free themselves from seigneurial authority, granting privileges and liberties to the emergent bourgeoisie. He built a great wall around Paris ("the Wall of Philip II Augustus"), re-organized the French government, and brought financial stability to his country.

Early years

Philip was born in

Philip was born in Gonesse

Gonesse () is a commune in the Val-d'Oise department, in the north-eastern suburbs of Paris, France. It is located from the centre of Paris.

The commune lies immediately north of Le Bourget Airport, and it is six kilometres (four miles) south- ...

on 21 August 1165, the son of Louis VII

Louis VII (1120 – 18 September 1180), called the Younger, or the Young (french: link=no, le Jeune), was King of the Franks from 1137 to 1180. He was the son and successor of King Louis VI (hence the epithet "the Young") and married Duchess ...

and Adela of Champagne. He was nicknamed Dieudonné (God-given) since he was the first born son, arriving late in his father's life.

Louis intended to make Philip co-ruler with him as soon as possible, in accordance with the traditions of the House of Capet

The House of Capet (french: Maison capétienne) or the Direct Capetians (''Capétiens directs''), also called the House of France (''la maison de France''), or simply the Capets, ruled the Kingdom of France from 987 to 1328. It was the most ...

, but these plans were delayed when Philip became ill after a hunting trip. His father went on pilgrimage to the Shrine of Thomas Becket

Thomas Becket (), also known as Saint Thomas of Canterbury, Thomas of London and later Thomas à Becket (21 December 1119 or 1120 – 29 December 1170), was an English nobleman who served as Lord Chancellor from 1155 to 1162, and then ...

to pray for Philip's recovery and was told that his son had indeed recovered. However, on his way back to Paris, the king suffered a stroke.

In declining health, Louis VII had his 14-year-old son crowned and anointed as king at Reims

Reims ( , , ; also spelled Rheims in English) is the most populous city in the French department of Marne, and the 12th most populous city in France. The city lies northeast of Paris on the Vesle river, a tributary of the Aisne.

Founded ...

on 1 November 1179 by Archbishop William of the White Hands. He was married on 28 April 1180 to Isabella of Hainault, the daughter of Count Baldwin V of Hainaut and Countess Margaret I of Flanders

Margaret I (c. 1145 - died 15 November 1194) was the countess of Flanders ''suo jure'' from 1191 to her death.

Early life

Margaret was the daughter of Count Thierry of Flanders and Sibylla of Anjou. In 1160 she married Count Ralph II of Vermand ...

. Isabella brought the County of Artois

The County of Artois (, ) was a historic province of the Kingdom of France, held by the Dukes of Burgundy from 1384 until 1477/82, and a state of the Holy Roman Empire from 1493 until 1659.

Present Artois lies in northern France, on the border ...

as her dowry. From the time of his coronation, all real power was transferred to Philip, as his father's health slowly declined. The great nobles were discontented with Philip's advantageous marriage. His mother and four uncles, all of whom exercised enormous influence over Louis, were extremely unhappy with his attainment of the throne, since Philip had taken the royal seal from his father. Louis died on 18 September 1180.

Consolidation of the royal demesne

The royal

The royal demesne

A demesne ( ) or domain was all the land retained and managed by a lord of the manor under the feudal system for his own use, occupation, or support. This distinguished it from land sub-enfeoffed by him to others as sub-tenants. The concept or ...

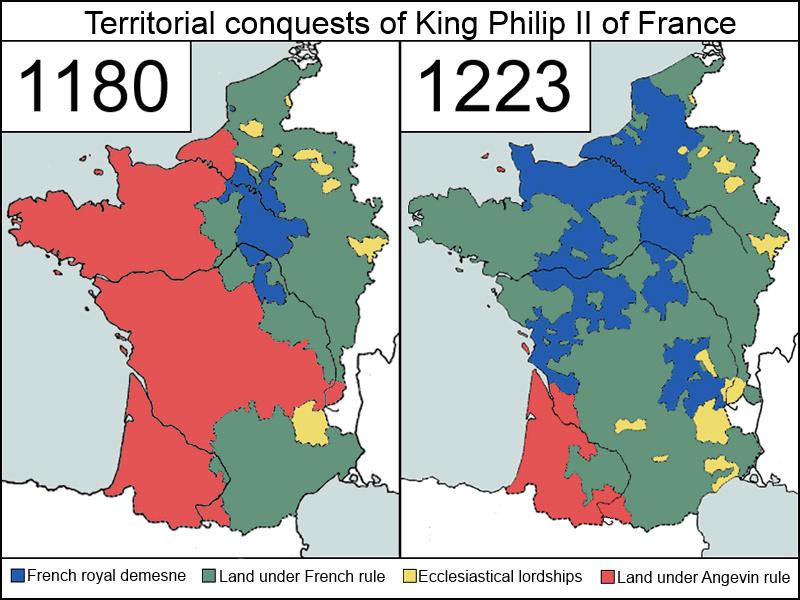

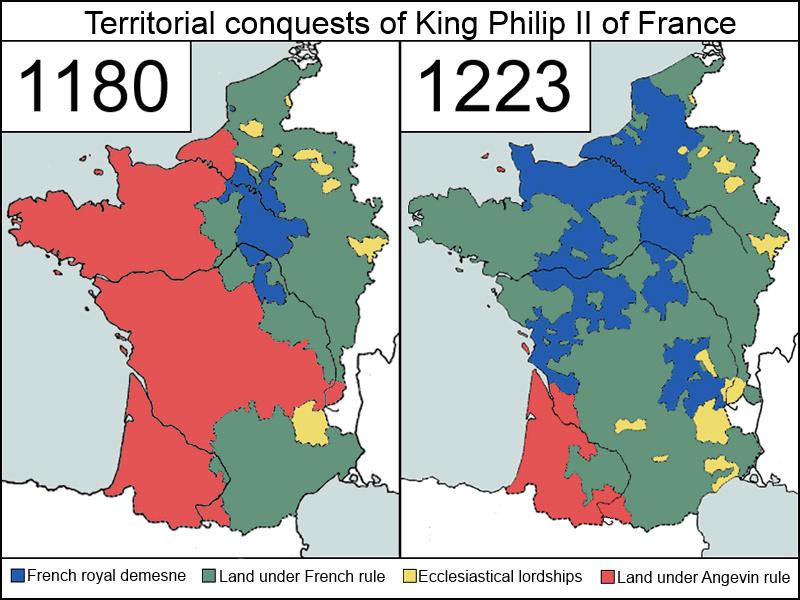

had increased under Philip I and Louis VI, but had slightly diminished under Louis VII. The first major increase to the royal demesne came in 1185, when Philip acquired the County of Amiens. He purchased the County of Clermont-en-Beauvaisis in 1218, and following the death of Robert I, Count of Alençon in 1219, Philip obtained the city and county of Alençon. Philip's eldest son, Louis, inherited the County of Artois in 1190, when Queen Isabella died.

Royal army

The main source of funding for Philip's army was from the royal demesne. In times of conflict, he could immediately call up 250 knights, 250 horse sergeants, 100 mounted crossbowmen, 133 crossbowmen on foot, 2,000-foot sergeants, and 300 mercenaries. Towards the end of his reign, the king could muster some 3,000 knights, 9,000 sergeants, 6,000 urban militiamen, and thousands of foot sergeants. Using his increased revenues, Philip was the first Capetian king to build a French navy actively. By 1215, his fleet could carry a total of 7,000 men. Within two years, his fleet included 10 large ships and many smaller ones.Expulsion of Jews

Reversing his father's toleration and protection of Jews, Philip in 1180 ordered French Jews to be stripped of their valuables, ransomed and converted to Christianity on pain of further taxation. In April 1182, partially to enrich the French crown, he expelled all Jews from the demesne and confiscated their goods. Philip expelled them from the royal demesne in July 1182 and had Jewish houses in Paris demolished to make way for theLes Halles

Les Halles (; 'The Halls') was Paris' central fresh food market. It last operated on January 12, 1973, after which it was "left to the demolition men who will knock down the last three of the eight iron-and-glass pavilions""Les Halles Dead at 20 ...

market. The measures were profitable in the short-term, the ransoms alone bringing in 15,000 marks and enriching Christians at the expense of Jews. Ninety-nine Jews were burned alive in Brie-Comte-Robert

Brie-Comte-Robert () is a commune in the Seine-et-Marne department in the Île-de-France region in north-central France.

Brie-Comte-Robert is on the edge of the plain of Brie and was formerly the capital of the ''Brie française''.

"Brie" ...

. In 1198 Philip allowed Jews to return.

Wars with his vassals

In 1181, a conflict arose between Philip and CountPhilip I of Flanders

Philip I (1143 – 1 August 1191), commonly known as Philip of Alsace, was count of Flanders from 1168 to 1191. During his rule Flanders prospered economically. He took part in two crusades and died of disease in the Holy Land.

Count of Flanders

...

over the Vermandois, which King Philip claimed as his wife's dowry. Finally the Count of Flanders invaded France, ravaging the whole district between the Somme __NOTOC__

Somme or The Somme may refer to: Places

*Somme (department), a department of France

*Somme, Queensland, Australia

*Canal de la Somme, a canal in France

*Somme (river), a river in France

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''Somme'' (book), a ...

and the Oise

Oise ( ; ; pcd, Oése) is a department in the north of France. It is named after the river Oise. Inhabitants of the department are called ''Oisiens'' () or ''Isariens'', after the Latin name for the river, Isara. It had a population of 829,419 ...

before penetrating as far as Dammartin. Notified of Philip's approach with 2,000 knights, he headed back to Flanders. Philip chased him, and the two armies confronted each other near Amiens

Amiens (English: or ; ; pcd, Anmien, or ) is a city and commune in northern France, located north of Paris and south-west of Lille. It is the capital of the Somme department in the region of Hauts-de-France. In 2021, the population of ...

. By this stage, Philip had managed to counter the ambitions of the count by breaking his alliances with Duke Henry I of Brabant and the Archbishop of Cologne

The Archbishop of Cologne is an archbishop governing the Archdiocese of Cologne of the Catholic Church in western North Rhine-Westphalia and is also a historical state in the Rhine holding the birthplace of Beethoven and northern Rhineland-Pala ...

, Philipp von Heinsberg. This, together with an uncertain outcome were he to engage the French in battle, forced the Count to conclude a peace. In July 1185, the Treaty of Boves left the disputed territory partitioned, with Amiénois, Artois, and numerous other places passing to the king, and the remainder, with the county of Vermandois proper, left provisionally to the Count of Flanders. It was during this time that Philip II was nicknamed "Augustus" by the monk Rigord Rigord (Rigordus) ( 1150 – c. 1209) was a French chronicler. He was probably born near Alais in Languedoc, and became a physician.

After becoming a monk he entered the monastery of Argenteuil, and then that of Saint-Denis, and described hims ...

for augmenting French lands.

Meanwhile, in 1184, Stephen I, Count of Sancerre

Stephen I (1133–1190), Count of Sancerre (1151–1190), inherited Sancerre on his father's death. His elder brothers Henry Ι and Theobald V received Champagne and Blois. His holdings were the smallest among the brothers (although William, the ...

and his Brabançon mercenaries ravaged the Orléanais. Philip defeated him with the aid of the Confrères de la Paix.

War with Henry II

A disagreement arose between Philip and KingHenry II of England

Henry II (5 March 1133 – 6 July 1189), also known as Henry Curtmantle (french: link=no, Court-manteau), Henry FitzEmpress, or Henry Plantagenet, was King of England from 1154 until his death in 1189, and as such, was the first Angevin king ...

, who was also Count of Anjou

The Count of Anjou was the ruler of the County of Anjou, first granted by Charles the Bald in the 9th century to Robert the Strong. Ingelger and his son, Fulk the Red, were viscounts until Fulk assumed the title of Count of Anjou. The Robertia ...

and Duke of Normandy

In the Middle Ages, the duke of Normandy was the ruler of the Duchy of Normandy in north-western France. The duchy arose out of a grant of land to the Viking leader Rollo by the French king Charles III in 911. In 924 and again in 933, Normandy ...

and Aquitaine

Aquitaine ( , , ; oc, Aquitània ; eu, Akitania; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''Aguiéne''), archaic Guyenne or Guienne ( oc, Guiana), is a historical region of southwestern France and a former administrative region of the country. Since 1 Januar ...

in France. The death of Henry's eldest son, Henry the Young King

Henry the Young King (28 February 1155 – 11 June 1183) was the eldest son of Henry II of England and Eleanor of Aquitaine to survive childhood. Beginning in 1170, he was titular King of England, Duke of Normandy, Count of Anjou and M ...

, in June 1183, began a dispute over the dowry

A dowry is a payment, such as property or money, paid by the bride's family to the groom or his family at the time of marriage. Dowry contrasts with the related concepts of bride price and dower. While bride price or bride service is a payment ...

of Philip's widowed sister Margaret

Margaret is a female first name, derived via French () and Latin () from grc, μαργαρίτης () meaning "pearl". The Greek is borrowed from Persian.

Margaret has been an English name since the 11th century, and remained popular through ...

. Philip insisted that the dowry should be returned to France as the marriage did not produce any children, per the betrothal agreement. The two kings would hold conferences at the foot of an elm tree near Gisors

Gisors () is a commune of Normandy, France. It is located northwest from the centre of Paris.

Gisors, together with the neighbouring communes of Trie-Château and Trie-la-Ville, form an urban area of 13,915 inhabitants (2018). This urban area i ...

, which was so positioned that it would overshadow each monarch's territory, but to no avail. Philip pushed the case further when King Béla III of Hungary

Béla III ( hu, III. Béla, hr, Bela III, sk, Belo III; 114823 April 1196) was King of Hungary and Croatia between 1172 and 1196. He was the second son of King Géza II and Géza's wife, Euphrosyne of Kiev. Around 1161, Géza granted Béla a ...

asked for the widow's hand in marriage, and thus her dowry had to be returned, to which Henry finally agreed.

The death of Henry's fourth son,

The death of Henry's fourth son, Geoffrey II, Duke of Brittany

Geoffrey II ( br, Jafrez; , xno, Geoffroy; 23 September 1158 – 19 August 1186) was Duke of Brittany and 3rd Earl of Richmond between 1181 and 1186, through his marriage to Constance, Duchess of Brittany. Geoffrey was the fourth of five sons ...

, began a new round of disputes, as Henry insisted that he retain the guardianship of the duchy for his unborn grandson Arthur I, Duke of Brittany. Philip, as Henry's liege lord, objected, stating that he should be the rightful guardian until the birth of the child. Philip then raised the issue of his other sister, Alys, Countess of Vexin, and her delayed betrothal to Henry's son Richard I of England

Richard I (8 September 1157 – 6 April 1199) was King of England from 1189 until his death in 1199. He also ruled as Duke of Normandy, Duke of Aquitaine, Aquitaine and Duchy of Gascony, Gascony, Lord of Cyprus, and Count of Poitiers, Co ...

, nicknamed Richard the Lionheart.

With these grievances, two years of combat followed (1186–1188), but the situation remained unchanged. Philip initially allied with Henry's young sons Richard the Lionheart and John, who were in rebellion against their father. Philip II launched an attack on Berry

A berry is a small, pulpy, and often edible fruit. Typically, berries are juicy, rounded, brightly colored, sweet, sour or tart, and do not have a stone or pit, although many pips or seeds may be present. Common examples are strawberries, rasp ...

in the summer of 1187, but by June made a truce with Henry, which left Issoudun

Issoudun () is a commune in the Indre department, administrative region of Centre-Val de Loire, France. It is also referred to as ''Issoundun'', which is the ancient name.

Geography Location

Issoudun is a sub-prefecture, located in the east o ...

in Philip's hands while also granting him Fréteval in Vendômois. Though the truce was for two years, Philip found grounds for resuming hostilities in the summer of 1188. He skillfully exploited the estrangement between Henry and Richard, and Richard did homage to him voluntarily at Bonsmoulins

Bonsmoulins () is a commune in the Orne department in northwestern France.

Population

Heraldry

See also

*Communes of the Orne department

The following is a list of the 385 communes of the Orne department of France.

The communes cooperat ...

in November 1188.

In 1189, as Henry's health was failing, Richard openly joined forces with Philip to drive him into submission. They chased him from Le Mans

Le Mans (, ) is a city in northwestern France on the Sarthe River where it meets the Huisne. Traditionally the capital of the province of Maine, it is now the capital of the Sarthe department and the seat of the Roman Catholic diocese of Le ...

to Saumur

Saumur () is a commune in the Maine-et-Loire department in western France.

The town is located between the Loire and Thouet rivers, and is surrounded by the vineyards of Saumur itself, Chinon, Bourgueil, Coteaux du Layon, etc.. Saumur ...

, losing Tours

Tours ( , ) is one of the largest cities in the region of Centre-Val de Loire, France. It is the prefecture of the department of Indre-et-Loire. The commune of Tours had 136,463 inhabitants as of 2018 while the population of the whole metr ...

in the process, before forcing him to acknowledge Richard as his heir. Finally, by the Treaty of Azay-le-Rideau (4 July 1189), Henry was forced to renew his own homage, confirm the cession of Issoudun to Philip (along with Graçay), and renounce his claim to suzerainty over Auvergne

Auvergne (; ; oc, label= Occitan, Auvèrnhe or ) is a former administrative region in central France, comprising the four departments of Allier, Puy-de-Dôme, Cantal and Haute-Loire. Since 1 January 2016, it has been part of the new region Auve ...

. Henry died two days later. His death, and the news of the fall of Jerusalem to Saladin

Yusuf ibn Ayyub ibn Shadi () ( – 4 March 1193), commonly known by the epithet Saladin,, ; ku, سهلاحهدین, ; was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from an ethnic Kurdish family, he was the first of both Egypt and ...

, diverted attention from the Franco-English war.

The Angevin kings of England (the line of rulers to which Henry II belonged), were Philip's most powerful and dangerous vassals as Dukes of Normandy and Aquitaine and Counts of Anjou. Philip made it his life's work to destroy Angevin power in France. One of his most effective tools was to befriend all of Henry's sons and use them to foment rebellion against their father. He maintained friendships with Henry the Young King and Geoffrey, Duke of Brittany until their deaths. Indeed, at Geoffrey's funeral, he was so overcome with grief that he had to be forcibly restrained from casting himself into the grave. He broke off his friendships with Henry's other sons Richard and John as each ascended to the English throne.

Third Crusade

Philip travelled to the Holy Land to participate in the

Philip travelled to the Holy Land to participate in the Third Crusade

The Third Crusade (1189–1192) was an attempt by three European monarchs of Western Christianity ( Philip II of France, Richard I of England and Frederick I, Holy Roman Emperor) to reconquer the Holy Land following the capture of Jerusalem by ...

of 1189–1192 with King Richard I of England and Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa, leaving Vézelay

Vézelay () is a commune in the department of Yonne in the north-central French region of Bourgogne-Franche-Comté. It is a defensible hill town famous for Vézelay Abbey. The town and its 11th-century Romanesque Basilica of St Magdalene are ...

with his army on 4 July 1190. At first, the French and English crusaders travelled together, but the armies split at Lyon

Lyon,, ; Occitan: ''Lion'', hist. ''Lionés'' also spelled in English as Lyons, is the third-largest city and second-largest metropolitan area of France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of ...

after Richard decided to go by sea from Marseille

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Fran ...

, whereas Philip took the overland route through the Alps

The Alps () ; german: Alpen ; it, Alpi ; rm, Alps ; sl, Alpe . are the highest and most extensive mountain range system that lies entirely in Europe, stretching approximately across seven Alpine countries (from west to east): France, ...

to Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Regions of Italy, Italian region of Liguria and the List of cities in Italy, sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of t ...

. The French and English armies were reunited in Messina

Messina (, also , ) is a harbour city and the capital city, capital of the Italian Metropolitan City of Messina. It is the third largest city on the island of Sicily, and the 13th largest city in Italy, with a population of more than 219,000 in ...

, where they wintered together. On 30 March 1191, the French set sail for the Holy Land and on 20 April Philip arrived at Acre

The acre is a unit of land area used in the imperial and US customary systems. It is traditionally defined as the area of one chain by one furlong (66 by 660 feet), which is exactly equal to 10 square chains, of a square mile, 4,840 square ...

, which was already under siege by a lesser contingent of crusaders, and he started to construct siege equipment before Richard arrived on 8 June. By the time Acre surrendered on 12 July, Philip was severely ill with dysentery

Dysentery (UK pronunciation: , US: ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complication ...

, which reduced his zeal. Ties with Richard were further strained after the latter acted in a haughty manner after Acre fell to the crusaders.

More importantly, the siege of Acre resulted in the death of Philip, Count of Flanders, who held the county of Vermandois proper. His death threatened to derail the Treaty of Gisors that Philip had orchestrated to isolate the powerful Blois-Champagne faction. Philip decided to return to France to settle the issue of succession in Flanders, a decision that displeased Richard, who said, "It is a shame and a disgrace on my lord if he goes away without having finished the business that brought him hither. But still, if he finds himself in bad health, or is afraid lest he should die here, his will be done." On 31 July 1191, the French army of 10,000 men (along with 5,000 silver marks to pay the soldiers) remained in Outremer

The Crusader States, also known as Outremer, were four Catholic realms in the Middle East that lasted from 1098 to 1291. These feudal polities were created by the Latin Catholic leaders of the First Crusade through conquest and political ...

under the command of Duke Hugh III of Burgundy. Philip and his cousin Peter of Courtenay, Count of Nevers, made their way to Rome, where Philip protested to Pope Celestine III

Pope Celestine III ( la, Caelestinus III; c. 1106 – 8 January 1198), was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 30 March or 10 April 1191 to his death in 1198. He had a tense relationship with several monarchs, ...

(to no avail) of Richard's abusive manner, and from there returned to France. The decision to return was also fuelled by the realisation that with Richard campaigning in the Holy Land, English possessions in northern France would be open to attack. After Richard's delayed return home, war between England and France would ensue over possession of English-controlled territories.

Conflict with England, Flanders and the Holy Roman Empire

Conflict with King Richard the Lionheart, 1191–1199

The immediate cause of Philip's conflict with Richard the Lionheart stemmed from Richard's decision to break his betrothal with Philip's sisterAlys Alys is a feminine given name. Notable people with the name include:

* Alys, Countess of the Vexin (c. 1160–1220), French princess

* Alys Clare (born 1944), English historical novelist

* Alys Faiz (1914–2003), Pakistani poet, writer, journalist ...

at Messina

Messina (, also , ) is a harbour city and the capital city, capital of the Italian Metropolitan City of Messina. It is the third largest city on the island of Sicily, and the 13th largest city in Italy, with a population of more than 219,000 in ...

in 1191. Some of Alys's dowry that had been given over to Richard during their engagement was part of the territory of Vexin. This should have reverted to Philip upon the end of the betrothal, but Philip, to prevent the collapse of the Crusade, agreed that this territory was to remain in Richard's hands and would be inherited by his male descendants. Should Richard die without an heir, the territory would return to Philip, and if Philip died without an heir, those lands would be considered a part of Normandy.

Returning to France in late 1191, Philip began plotting to find a way to have those territories restored to him. He was in a difficult situation, as he had taken an oath not to attack Richard's lands while he was away on crusade. The Third Crusade ordained territory was under the protection of the Church in any event. Philip was unsuccessful in requesting a release from his oath from Pope Celestine III

Pope Celestine III ( la, Caelestinus III; c. 1106 – 8 January 1198), was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 30 March or 10 April 1191 to his death in 1198. He had a tense relationship with several monarchs, ...

, so he was forced to build his own casus belli

A (; ) is an act or an event that either provokes or is used to justify a war. A ''casus belli'' involves direct offenses or threats against the nation declaring the war, whereas a ' involves offenses or threats against its ally—usually one ...

.

On 20 January 1192, Philip met with William FitzRalph, Richard's seneschal

The word ''seneschal'' () can have several different meanings, all of which reflect certain types of supervising or administering in a historic context. Most commonly, a seneschal was a senior position filled by a court appointment within a royal, ...

for Normandy. Presenting some documents purporting to be from Richard, Philip claimed that the English king had agreed at Messina to hand disputed lands over to France. Not having heard anything directly from their sovereign, FitzRalph and the Norman barons rejected Philip's claim to Vexin. Philip at this time also began spreading rumors about Richard's action in the east to discredit the English king in the eyes of his subjects. Among the stories Philip invented included Richard involved in treacherous communication with Saladin

Yusuf ibn Ayyub ibn Shadi () ( – 4 March 1193), commonly known by the epithet Saladin,, ; ku, سهلاحهدین, ; was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from an ethnic Kurdish family, he was the first of both Egypt and ...

, alleging he had conspired to cause the fall of Gaza

Gaza may refer to:

Places Palestine

* Gaza Strip, a Palestinian territory on the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea

** Gaza City, a city in the Gaza Strip

** Gaza Governorate, a governorate in the Gaza Strip Lebanon

* Ghazzeh, a village in ...

, Jaffa, and Ashkelon

Ashkelon or Ashqelon (; Hebrew: , , ; Philistine: ), also known as Ascalon (; Ancient Greek: , ; Arabic: , ), is a coastal city in the Southern District of Israel on the Mediterranean coast, south of Tel Aviv, and north of the border ...

, and that he had participated in the murder of Conrad of Montferrat

Conrad of Montferrat ( Italian: ''Corrado del Monferrato''; Piedmontese: ''Conrà ëd Monfrà'') (died 28 April 1192) was a nobleman, one of the major participants in the Third Crusade. He was the ''de facto'' King of Jerusalem (as Conrad I) by ...

. Finally, Philip made contact with John, Richard's brother, whom he convinced to join the conspiracy to overthrow the legitimate king of England.

At the start of 1193, John visited Philip in Paris, where he paid homage for Richard's continental lands. When word reached Philip that Richard had finished crusading and had been captured on his way back from the Holy Land, he promptly invaded Vexin. His first target was the fortress of Gisors, commanded by Gilbert de Vascoeuil, which surrendered without putting up a struggle. Philip then penetrated deep into Normandy, reaching as far as Dieppe. To keep the duplicitous John on his side, Philip entrusted him with the defence of the town of Évreux

Évreux () is a commune in and the capital of the department of Eure, in the French region of Normandy.

Geography

The city is on the Iton river.

Climate

History

In late Antiquity, the town, attested in the fourth century CE, was named ...

. Meanwhile, Philip was joined by Count Baldwin IX of Flanders, and together they laid siege to Rouen

Rouen (, ; or ) is a city on the River Seine in northern France. It is the prefecture of the region of Normandy and the department of Seine-Maritime. Formerly one of the largest and most prosperous cities of medieval Europe, the population ...

, the ducal capital of Normandy. Here, Philip's advance was halted by a defense led by the Earl of Leicester. Unable to penetrate this defense, Philip moved on.

At Mantes on 9 July 1193, Philip came to terms with Richard's ministers, who agreed that Philip could keep his gains and would be given some extra territories if he ceased all further aggressive actions in Normandy, along with the condition that Philip would hand back the captured territory if Richard would pay homage. To prevent Richard from spoiling their plans, Philip and John attempted to bribe Holy Roman Emperor Henry VI in order to keep the English king captive for a little while longer. Henry refused, and Richard was released from captivity on 4 February 1194. By 13 March Richard had returned to England, and by 12 May he had set sail for Normandy with some 300 ships, eager to engage Philip in war.

Philip had spent this time consolidating his territorial gains and by now controlled much of Normandy east of the Seine

The Seine ( , ) is a river in northern France. Its drainage basin is in the Paris Basin (a geological relative lowland) covering most of northern France. It rises at Source-Seine, northwest of Dijon in northeastern France in the Langres plate ...

, while remaining within striking distance of Rouen. His next objective was the castle of Verneuil, which had withstood an earlier siege. Once Richard arrived at Barfleur

Barfleur () is a commune and fishing village in Manche, Normandy, northwestern France.

History

During the Middle Ages, Barfleur was one of the chief ports of embarkation for England.

* 1066: A large medallion fixed to a rock in the har ...

, he soon marched towards Verneuil. As his forces neared the castle, Philip, who had been unable to break through, decided to strike camp. Leaving a large force behind to prosecute the siege, he moved off towards Évreux, which John had handed over to his brother to prove his loyalty. Philip retook the town and sacked it, but during this time, his forces at Verneuil abandoned the siege, and Richard entered the castle unopposed on 30 May. Throughout June, while Philip's campaign ground to a halt in the north, Richard was taking a number of important fortresses to the south. Philip, eager to relieve the pressure off his allies in the south, marched to confront Richard's forces at Vendôme

Vendôme (, ) is a subprefecture of the department of Loir-et-Cher, France. It is also the department's third-biggest commune with 15,856 inhabitants (2019).

It is one of the main towns along the river Loir. The river divides itself at the ent ...

. Refusing to risk everything in a major battle, Philip retreated, only to have his rear guard caught at Fréteval on 3 July. This Battle of Fréteval turned into a general encounter in which Philip barely managed to avoid capture as his army was put to flight. Fleeing back to Normandy, Philip avenged himself on the English by attacking the forces of John and the Earl of Arundel

Earl of Arundel is a title of nobility in England, and one of the oldest extant in the English peerage. It is currently held by the Duke of Norfolk, and is used (along with the Earl of Surrey) by his heir apparent as a courtesy title. The ...

, seizing their baggage train. By now both sides were tiring, and they agreed to the temporary Truce of Tillières.

The war resumed in 1195 when Philip once again besieged Verneuil. He continued the siege in secret as Richard arrived to negotiate in person; when Richard found out, he swore revenge and left. Philip now pressed his advantage in northeastern Normandy, where he conducted a raid at Dieppe, burning the English ships in the harbor while repulsing an attack by Richard at the same time. Philip now marched southward into the Berry region. His primary objective was the fortress of Issoudun

Issoudun () is a commune in the Indre department, administrative region of Centre-Val de Loire, France. It is also referred to as ''Issoundun'', which is the ancient name.

Geography Location

Issoudun is a sub-prefecture, located in the east o ...

, which had just been captured by Richard's mercenary commander, Mercadier

Mercadier (died 10 April 1200) was a famous Occitan warrior of the 12th century, and the leader of a group of mercenaries in the service of Richard I, King of England.

In 1183 he appears as a leader of Brabançon mercenaries in Southern France. ...

. The French king took the town and was besieging the castle when Richard stormed through French lines and made his way in to reinforce the garrison, while at the same time another army was approaching Philip's supply lines. Philip called off his attack, and another truce was agreed.

The war slowly turned against Philip over the course of the next three years. Political and military conditions seemed promising at the start of 1196 when Richard's nephew Arthur I, Duke of Brittany ended up in Philip's hands, and he won the Siege of Aumale, but Philip's good fortune did not last. Richard won over a key ally, Baldwin of Flanders

Baldwin I ( nl, Boudewijn; french: Baudouin; July 1172 – ) was the first Emperor of the Latin Empire of Constantinople; Count of Flanders (as Baldwin IX) from 1194 to 1205 and Count of Hainaut (as Baldwin VI) from 1195-1205. Baldwin was on ...

, in 1197. The same year, the Holy Roman Emperor Henry VI died and was succeeded by Otto IV, Richard's nephew, who put additional pressure on Philip. Finally, many Norman lords were switching sides and returning to Richard's camp. This was the state of affairs when Philip launched his campaign of 1198 with an attack on Vexin that was pushed back and then compounded by the Flemish invasion of Artois.

On 27 September, Richard entered Vexin, taking Courcelles-sur-Seine and Boury-en-Vexin

Boury-en-Vexin (, literally ''Boury in Vexin'') is a commune in the Oise department in northern France.

Population

See also

* Communes of the Oise department

* Vexin

Vexin () is an historical county of northwestern France. It covers a ve ...

before returning to Dangu. Philip, believing that Courcelles was still holding out, went to its relief. Discovering what was happening, Richard decided to attack the French king's forces, catching Philip by surprise. Philip's forces fled and attempted to reach the fortress of Gisors. Bunched together, the French knights with king Philip attempted to cross the Epte River on a bridge that promptly collapsed under their weight, almost drowning Philip in the process. He was dragged out of the river and shut himself up in Gisors.

Philip soon planned a new offensive, launching raids into Normandy and again targeting Évreux. Richard countered Philip's thrust with a counterattack in Vexin, while Mercadier led a raid on Abbeville

Abbeville (, vls, Abbekerke, pcd, Advile) is a commune in the Somme department and in Hauts-de-France region in northern France.

It is the chef-lieu of one of the arrondissements of Somme. Located on the river Somme, it was the capital o ...

. By autumn 1198, Richard had regained almost all that had been lost in 1193. In desperate circumstances, Philip offered a truce so that discussions could begin towards a more permanent peace, with the offer that he would return all of the territories except for Gisors.

In mid-January 1199, the two kings met for a final meeting, Richard standing on the deck of a boat, Philip standing on the banks of the Seine River. Shouting terms at each other, they could not reach agreement on the terms of a permanent truce, but they did agree to further mediation, which resulted in a five-year truce that held. Later in 1199, Richard was killed during a siege involving one of his vassals.

Conflict with King John, 1200–1206

In May 1200, Philip signed the Treaty of Le Goulet with Richard's successorKing John King John may refer to:

Rulers

* John, King of England (1166–1216)

* John I of Jerusalem (c. 1170–1237)

* John Balliol, King of Scotland (c. 1249–1314)

* John I of France (15–20 November 1316)

* John II of France (1319–1364)

* John I o ...

. The treaty was meant to bring peace to Normandy by settling the issue of its much-reduced boundaries. The terms of John's vassalage were not only for Normandy, but also for Anjou, Maine, and Touraine

Touraine (; ) is one of the traditional provinces of France. Its capital was Tours. During the political reorganization of French territory in 1790, Touraine was divided between the departments of Indre-et-Loire, :Loir-et-Cher, Indre and V ...

. John agreed to heavy terms, including the abandonment of all the English possessions in Berry and 20,000 marks of silver, while Philip in turn recognised John as king of England, formally abandoning Arthur of Brittany's candidacy, whom he had hitherto supported, recognising instead John's suzerainty over the Duchy of Brittany

The Duchy of Brittany ( br, Dugelezh Breizh, ; french: Duché de Bretagne) was a medieval feudal state that existed between approximately 939 and 1547. Its territory covered the northwestern peninsula of Europe, bordered by the Atlantic Ocean t ...

. To seal the treaty, a marriage between Blanche of Castile, John's niece, and Louis the Lion

Louis VIII (5 September 1187 – 8 November 1226), nicknamed The Lion (french: Le Lion), was King of France from 1223 to 1226. As prince, he invaded England on 21 May 1216 and was excommunicated by a papal legate on 29 May 1216. On 2 June 1216 ...

, Philip's son, was contracted.

This agreement did not bring warfare to an end in France, however, since John's mismanagement of Aquitaine led the province to later rebel in 1200, a disturbance that Philip secretly encouraged. To disguise his ambitions, Philip invited John to a conference at Andely and then entertained him at Paris, and both times he committed to complying with the treaty. In 1202, disaffected patrons petitioned the French king to summon John to answer their charges in his capacity as John's feudal lord in France. John refused to appear, so Philip again took up Arthur of Brittany's claims to the English throne as well as betrothing him to his six-year-old daughter Marie. In retaliation John crossed over into Normandy and his forces soon captured Arthur. In 1203, Arthur disappeared, with most people believing that John had had him murdered. The outcry over Arthur's fate saw an increase in local opposition to John, which Philip used to his advantage. He took to the offensive and, apart from a five-month siege of Andely, swept all before him. After Andely surrendered, John fled to England. By the end of 1204, most of Normandy and the Angevin lands, including much of

This agreement did not bring warfare to an end in France, however, since John's mismanagement of Aquitaine led the province to later rebel in 1200, a disturbance that Philip secretly encouraged. To disguise his ambitions, Philip invited John to a conference at Andely and then entertained him at Paris, and both times he committed to complying with the treaty. In 1202, disaffected patrons petitioned the French king to summon John to answer their charges in his capacity as John's feudal lord in France. John refused to appear, so Philip again took up Arthur of Brittany's claims to the English throne as well as betrothing him to his six-year-old daughter Marie. In retaliation John crossed over into Normandy and his forces soon captured Arthur. In 1203, Arthur disappeared, with most people believing that John had had him murdered. The outcry over Arthur's fate saw an increase in local opposition to John, which Philip used to his advantage. He took to the offensive and, apart from a five-month siege of Andely, swept all before him. After Andely surrendered, John fled to England. By the end of 1204, most of Normandy and the Angevin lands, including much of Aquitaine

Aquitaine ( , , ; oc, Aquitània ; eu, Akitania; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''Aguiéne''), archaic Guyenne or Guienne ( oc, Guiana), is a historical region of southwestern France and a former administrative region of the country. Since 1 Januar ...

, had fallen into Philip's hands.

What Philip had gained through victory in war, he sought to confirm by legal means. Philip, again acting as John's liege lord over his French lands, summoned him to appear before the Court of the Twelve Peers of France to answer for Arthur's murder. John requested safe conduct, but Philip only agreed to allow him to come in peace, while providing for his return only if it were allowed after the judgment of his peers. Not willing to risk his life on such a guarantee, John refused to appear, so Philip summarily dispossessed the English of all lands. Pushed by his barons, John eventually launched an invasion of northern France in 1206, disembarking with his army at La Rochelle

La Rochelle (, , ; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''La Rochéle''; oc, La Rochèla ) is a city on the west coast of France and a seaport on the Bay of Biscay, a part of the Atlantic Ocean. It is the capital of the Charente-Maritime department. Wit ...

during one of Philip's absences, but the campaign ended up a disaster. After backing out of a conference that he himself had demanded, John eventually bargained at Thouars

Thouars () is a commune in the Deux-Sèvres department in western France. On 1 January 2019, the former communes Mauzé-Thouarsais, Missé and Sainte-Radegonde were merged into Thouars.

It is on the River Thouet. Its inhabitants are known ...

for a two-year truce, the price of which was his agreement to the chief provisions of the judgment of the Court of Peers, including a loss of his patrimony.

Alliances against Philip, 1208–1213

In 1208,

In 1208, Philip of Swabia

Philip of Swabia (February/March 1177 – 21 June 1208) was a member of the House of Hohenstaufen and King of Germany from 1198 until his assassination.

The death of his older brother Emperor Henry VI in 1197 meant that the Hohenstaufen rule ( ...

, the successful candidate to become Holy Roman Emperor, was assassinated. As a result, the imperial crown was given to his rival Otto IV, the nephew of King John. Otto, prior to his accession, had promised to help John recover his lost possessions in France, but circumstances prevented him from making good on his promise. By 1212, both John and Otto were engaged in power struggles against Pope Innocent III

Pope Innocent III ( la, Innocentius III; 1160 or 1161 – 16 July 1216), born Lotario dei Conti di Segni (anglicized as Lothar of Segni), was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 January 1198 to his death in 16 ...

: John over his refusal to accept the papal nomination for the archbishop of Canterbury, and Otto over his attempt to strip King Frederick II of Germany of the Kingdom of Sicily. Philip decided to take advantage of this situation, first in Germany, where he aided German noble rebellion in support of the young Frederick. John immediately threw England's weight behind Otto, and Philip now saw his chance to launch a successful invasion of England.

In order to secure the cooperation of all his vassals in his plans for the invasion, Philip denounced John as an enemy of the Church, thereby justifying his attack as motivated solely by religious scruples. He summoned an assembly of French barons at Soissons

Soissons () is a commune in the northern French department of Aisne, in the region of Hauts-de-France. Located on the river Aisne, about northeast of Paris, it is one of the most ancient towns of France, and is probably the ancient capital ...

, which was well attended. The only exception was Count Ferdinand of Flanders, who refused out of anger over the loss of the towns of Aire and Saint-Omer

Saint-Omer (; vls, Sint-Omaars) is a commune and sub-prefecture of the Pas-de-Calais department in France.

It is west-northwest of Lille on the railway to Calais, and is located in the Artois province. The town is named after Saint Audomar, ...

that had been captured by Philip's son Louis the Lion. He would not participate in any campaign until he was restored to his ancient lands.

Philip was eager to prove his loyalty to Rome and thus secure papal support for his planned invasion, announced at Soissons a reconciliation with his estranged wife Ingeborg of Denmark, which the popes had been promoting. The barons fully supported his plan, and they all gathered their forces and prepared to join with Philip at the agreed rendezvous. Through all of this, Philip remained in constant communication with Pandulf Verraccio, the papal legate

300px, A woodcut showing Henry II of England greeting the pope's legate.

A papal legate or apostolic legate (from the ancient Roman title ''legatus'') is a personal representative of the pope to foreign nations, or to some part of the Catholic ...

, who was encouraging Philip to pursue his objective. Verraccio however was also holding secret discussions with King John. Advising the English king of his precarious predicament, he persuaded John to abandon his opposition to papal investiture and agreed to accept the papal legate's decision in any ecclesiastical disputes as final. In return, the pope agreed to accept the Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England (, ) was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from 12 July 927, when it emerged from various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain.

On ...

and the Lordship of Ireland

The Lordship of Ireland ( ga, Tiarnas na hÉireann), sometimes referred to retroactively as Norman Ireland, was the part of Ireland ruled by the King of England (styled as "Lord of Ireland") and controlled by loyal Anglo-Norman lords between ...

as papal fiefs, which John would rule as the pope's vassal, and for which John would do homage to the pope.

No sooner had the treaty between John and the pope been ratified in May 1213 than Verraccio announced to Philip that he would have to abandon his expedition against John, since to attack a faithful vassal of the Holy See

The Holy See ( lat, Sancta Sedes, ; it, Santa Sede ), also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the Pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of R ...

would be a mortal sin

A mortal sin ( la, peccatum mortale), in Catholic theology, is a gravely sinful act which can lead to Hell in Christianity#Roman_Catholicism, damnation if a person does not repent of the sin before death. A sin is considered to be "mortal" wh ...

. Philip argued in vain that his plans had been drawn up with the consent of Rome, that his expedition was in support of papal authority that he only undertook on the understanding that he would gain a plenary indulgence; he had spent a fortune preparing for the expedition. The papal legate remained unmoved, but Verraccio did suggest an alternative. The Count of Flanders had denied Philip's right to declare war on England while King John was still excommunicated

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

, and that his disobedience needed to be punished. Philip eagerly accepted the advice, and quickly marched at the head of his troops into the territory of Flanders.

Battle of Bouvines, 1214

The French fleet proceeded first to

The French fleet proceeded first to Gravelines

Gravelines (, ; ; ) is a commune in the Nord department in Northern France. It lies at the mouth of the river Aa southwest of Dunkirk. It was formed in the 12th century around the mouth of a canal built to connect Saint-Omer with the sea. As ...

and then to the port of Damme. Meanwhile, the army marched by Cassel, Ypres

Ypres ( , ; nl, Ieper ; vls, Yper; german: Ypern ) is a Belgian city and municipality in the province of West Flanders. Though

the Dutch name is the official one, the city's French name is most commonly used in English. The municipality ...

, and Bruges

Bruges ( , nl, Brugge ) is the capital and largest city

A city is a human settlement of notable size.Goodall, B. (1987) ''The Penguin Dictionary of Human Geography''. London: Penguin.Kuper, A. and Kuper, J., eds (1996) ''The Social Scienc ...

before laying siege to Ghent

Ghent ( nl, Gent ; french: Gand ; traditional English: Gaunt) is a city and a Municipalities of Belgium, municipality in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is the capital and largest city of the East Flanders province, and the third largest i ...

. Hardly had the siege begun when Philip learned that the English fleet had captured a number of his ships at Damme and that the rest were so closely blockaded in its harbor that it was impossible for them to escape. He ordered the fleet to be burned to prevent it from falling into enemy hands.

The destruction of the French fleet had once again raised John's hopes, so he began preparing for an invasion of France and a reconquest of his lost provinces. The English barons were initially unenthusiastic about the expedition, which delayed his departure, so it was not until February 1214 that he disembarked at La Rochelle. John was to advance from the Loire

The Loire (, also ; ; oc, Léger, ; la, Liger) is the longest river in France and the 171st longest in the world. With a length of , it drains , more than a fifth of France's land, while its average discharge is only half that of the Rhôn ...

, while his ally Otto IV made a simultaneous attack from Flanders, together with the Count of Flanders. The three armies did not coordinate their efforts effectively. It was not until John had been disappointed in his hope for an easy victory after being driven from Roche-au-Moine and had retreated to his transports that the Imperial Army, with Otto at its head, assembled in the Low Countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, déi Niddereg Lännereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

.

On 27 July 1214, the opposing armies suddenly discovered that they were in close proximity to one another, on the banks of a little tributary of the River Lys, near the bridge at

On 27 July 1214, the opposing armies suddenly discovered that they were in close proximity to one another, on the banks of a little tributary of the River Lys, near the bridge at Bouvines

Bouvines (; nl, Bovingen) is a commune and village in the Nord department in northern France. It is on the French-Belgian border between Lille and Tournai.

History

On 27 July 1214, the Battle of Bouvines was fought here between the forces of F ...

. It being a Sunday, Philip did not expect the allied army to attack, as it was considered unholy to fight on the Sabbath. Philip's army numbered some 7,000, while the allied forces possessed around 9,000 troops. The armies clashed at what became known as the Battle of Bouvines

The Battle of Bouvines was fought on 27 July 1214 near the town of Bouvines in the County of Flanders. It was the concluding battle of the Anglo-French War of 1213–1214. Although estimates on the number of troops vary considerably among mo ...

. Philip was unhorsed by the Flemish pikemen in the heat of battle, and were it not for his mail armor he would have probably been killed. When Otto was carried off the field by his wounded and terrified horse, and the Count of Flanders was severely wounded and taken prisoner, the Flemish and Imperial troops saw that the battle was lost, turned, and fled the field. The French did not pursue.

Philip returned to Paris triumphant, marching his captive prisoners behind him in a long procession, as his grateful subjects came out to greet the victorious king. In the aftermath of the battle, Otto retreated to his castle of Harzburg and was soon overthrown as Holy Roman Emperor, to be replaced by Frederick II. Count Ferdinand remained imprisoned following his defeat, while King John's attempt to rebuild the Angevin Empire ended in complete failure.

Philip's decisive victory was crucial in shaping Western European politics in both England and France. In England, the defeated John was so weakened that he was soon required to submit to the demands of his barons and sign Magna Carta, which limited the power of the crown and established the basis for common law. The Battle of Bouvines marked the end of the Angevin Empire.

Marital problems

After the early death of Isabella of Hainaut in childbirth in 1190, Philip decided to marry again. On 15 August 1193, he married Ingeborg, daughter of KingValdemar I of Denmark

Valdemar I (14 January 1131 – 12 May 1182), also known as Valdemar the Great ( da, Valdemar den Store), was King of Denmark from 1154 until his death in 1182. The reign of King Valdemar I saw the rise of Denmark, which reached its medieval zen ...

, receiving 10,000 marks of silver as a dowry

A dowry is a payment, such as property or money, paid by the bride's family to the groom or his family at the time of marriage. Dowry contrasts with the related concepts of bride price and dower. While bride price or bride service is a payment ...

. Philip met her at Amiens on 14 August 1193 and they were married that same day. At the feast of the Assumption of the Virgin, Archbishop Guillaume of Reims crowned both Philip and Ingeborg. During the ceremony, Philip was pale, nervous, and could not wait for the ceremony to end. Following the ceremony, he had Ingeborg sent to the convent of Saint-Maur-des-Fosses and asked Pope Celestine III

Pope Celestine III ( la, Caelestinus III; c. 1106 – 8 January 1198), was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 30 March or 10 April 1191 to his death in 1198. He had a tense relationship with several monarchs, ...

for an annulment on the grounds of non-consummation. Philip had not reckoned with Ingeborg, however; she insisted that the marriage had been consummated, and that she was his wife and the rightful queen of France. The Franco-Danish churchman William of Æbelholt intervened on Ingeborg's side, drawing up a genealogy

Genealogy () is the study of families, family history, and the tracing of their lineages. Genealogists use oral interviews, historical records, genetic analysis, and other records to obtain information about a family and to demonstrate kins ...

of the Danish kings to disprove the alleged impediment of consanguinity

Consanguinity ("blood relation", from Latin '' consanguinitas'') is the characteristic of having a kinship with another person (being descended from a common ancestor).

Many jurisdictions have laws prohibiting people who are related by blood fr ...

.

In the meantime, Philip had sought a new bride. Initial agreement had been reached for him to marry Margaret

Margaret is a female first name, derived via French () and Latin () from grc, μαργαρίτης () meaning "pearl". The Greek is borrowed from Persian.

Margaret has been an English name since the 11th century, and remained popular through ...

, daughter of Count William I of Geneva, but the young bride's journey to Paris was interrupted by Thomas, Count of Savoy, who kidnapped Philip's intended new wife and married her instead, claiming that Philip was already bound in marriage. Philip finally achieved a third marriage in June 1196, when he was married to Agnes of Merania from Dalmatia. Their children were Marie and Philip, Count of Clermont.

Pope Innocent III declared Philip Augustus' marriage to Agnes of Merania null and void, as he was still married to Ingeborg. He ordered the king to part from Agnes, and when he did not, the pope placed France under an interdict in 1199. This continued until 7 September 1200. Due to pressure from the pope, Ingeborg's brother King Valdemar II of Denmark

Valdemar (28 June 1170 – 28 March 1241), later remembered as Valdemar the Victorious (), was the King of Denmark (being Valdemar II) from 1202 until his death in 1241.

Background

He was the second son of King Valdemar I of Denmark and Sophia ...

and ultimately Agnes' death in 1201, Philip finally took Ingeborg back as his wife, but it would not be until 1213 that she would be recognized at court as queen.

Appearance and personality

The only known description of Philip describes him as "a handsome, strapping fellow, bald but with a cheerful face of ruddy complexion, and a temperament much inclined towards good-living, wine, and women. He was generous to his friends, stingy towards those who displeased him, well-versed in the art of stratagem, orthodox in belief, prudent and stubborn in his resolves. He made judgements with great speed and exactitude. Fortune's favorite, fearful for his life, easily excited and easily placated, he was very tough with powerful men who resisted him, and took pleasure in provoking discord among them. Never, however, did he cause an adversary to die in prison. He liked to employ humble men, to be the subduer of the proud, the defender of the Church, and feeder of the poor".Issue

*By Isabella of Hainault: ** Louis VIII (5 September 11878 November 1226),King of France

France was ruled by Monarch, monarchs from the establishment of the West Francia, Kingdom of West Francia in 843 until the end of the Second French Empire in 1870, with several interruptions.

Classical French historiography usually regards Cl ...

(1223–1226); married Blanche of Castile and had issue.

**Robert (born and died 14 March 1190)

**Philip (14 March 119017 March 1190)

*By Agnes of Merania:

** Marie (119815 August 1238); married firstly Philip I of Namur. Married secondly Henry I, Duke of Brabant

Henry I ( nl, Hendrik, french: Henri; c. 1165 – 5 September 1235), named "The Courageous", was a member of the House of Reginar and first duke of Brabant from 1183/84 until his death.

Early life

Henry was possibly born in Leuven (Louvain ...

, had issue.

** Philip (July 120014/18 January 1234), Count of Boulogne by marriage; married Matilda II, Countess of Boulogne and had issue.

*By a woman in Arras:

** Pierre Charlot, bishop of Noyon.

Later years

When Pope Innocent III called for a crusade against the "Albigensians," or

When Pope Innocent III called for a crusade against the "Albigensians," or Cathars

Catharism (; from the grc, καθαροί, katharoi, "the pure ones") was a Christian Dualistic cosmology, dualist or Gnosticism, Gnostic movement between the 12th and 14th centuries which thrived in Southern Europe, particularly in northern ...

, in Languedoc

The Province of Languedoc (; , ; oc, Lengadòc ) is a former province of France.

Most of its territory is now contained in the modern-day region of Occitanie in Southern France. Its capital city was Toulouse. It had an area of approximatel ...

in 1208, Philip did nothing to support it, though he did not stop his nobles from joining in. The war against the Cathars did not end until 1244, when their last strongholds were finally captured. The fruits of the victory, the submission of the south of France to the crown, were to be reaped by Philip's son Louis VIII and grandson Louis IX. From 1216 to 1222, Philip also arbitrated in the War of the Succession of Champagne and finally helped the military efforts of Duke Odo III of Burgundy and Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II to bring it to an end.

Philip II Augustus played a significant role in one of the greatest centuries of innovation in construction and education in France. With Paris as his capital, he had the main thoroughfares paved, built a central market, Les Halles

Les Halles (; 'The Halls') was Paris' central fresh food market. It last operated on January 12, 1973, after which it was "left to the demolition men who will knock down the last three of the eight iron-and-glass pavilions""Les Halles Dead at 20 ...

, continued the construction begun in 1163 of Notre-Dame de Paris

Notre-Dame de Paris (; meaning "Our Lady of Paris"), referred to simply as Notre-Dame, is a medieval Catholic cathedral on the Île de la Cité (an island in the Seine River), in the 4th arrondissement of Paris. The cathedral, dedicated to th ...

, constructed the first incarnation of the Louvre

The Louvre ( ), or the Louvre Museum ( ), is the world's most-visited museum, and an historic landmark in Paris, France. It is the home of some of the best-known works of art, including the ''Mona Lisa'' and the ''Venus de Milo''. A central l ...

as a fortress, and gave a charter to the University of Paris

The University of Paris (french: link=no, Université de Paris), Metonymy, metonymically known as the Sorbonne (), was the leading university in Paris, France, active from 1150 to 1970, with the exception between 1793 and 1806 under the French Revo ...

in 1200. Under his guidance, Paris became the first city of teachers the medieval world knew. In 1224, the French poet Henry d'Andeli wrote of the great wine tasting competition that Philip II Augustus commissioned, the Battle of the Wines.

Philip II fell ill in September 1222 and had a will made, but carried on with his itinerary. Hot weather the next summer worsened his fever, but a brief remission prompted him to travel to Paris on 13 July 1223, against the advice of his physician. He died en route the next day, in Mantes-la-Jolie, at the age of 58. His body was carried to Paris on a bier. He was interred in the Basilica of St Denis in the presence of his son and successor, Louis VIII, as well as his illegitimate son Philip I, Count of Boulogne and John of Brienne

John of Brienne ( 1170 – 19–23 March 1237), also known as John I, was King of Jerusalem from 1210 to 1225 and Latin Emperor of Constantinople from 1229 to 1237. He was the youngest son of Erard II of Brienne, a wealthy nobleman in Champ ...

, the King of Jerusalem.

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

* * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Philip 02 Of France 1165 births 1223 deaths 12th-century kings of France 13th-century kings of France People from Gonesse Regents of Brittany House of Capet Counts of Vermandois Christians of the Third Crusade Christians of the Children's Crusade Christians of the Fifth Crusade Burials at the Basilica of Saint-Denis Male Shakespearean characters