Pedro De Aycinena Y PiĂąol on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Belize region in the Yucatan Peninsula was never occupied by either Spain or Guatemala, even though Spain made some exploratory expeditions in the 16th century that served as its basis to claim the area; Guatemala simply inherited that argument to claim the territory, even though it never sent any expedition to the area after the Independence from Spain in 1821, due to the Central American civil war that ensued and lasted until 1860. On the other hand, the British had established a small settlement there since the middle of the 17th century, mainly as buccaneers quarters and then for fine wood production; the settlements were never recognized as British colonies even though they were somewhat under the jurisdiction of the Jamaican British government. In the 18th century, Belize became the main smuggling center for Central America, even though the British accepted Spanish sovereignty over the region by means of the 1783 and 1786 treaties, in exchange for a cease fire and the authorization for the Englishmen to continue logging in Belize.

After the Central America independence from Spain in 1821, Belize became the leading edge of the commercial entrance of Britain in the isthmus; British commercial brokers established themselves there and created prosperous commercial routes with the Caribbean harbors of Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua.

The liberals came to power in Guatemala in 1829 after defeating and expelling the Aycinena family and the

The Belize region in the Yucatan Peninsula was never occupied by either Spain or Guatemala, even though Spain made some exploratory expeditions in the 16th century that served as its basis to claim the area; Guatemala simply inherited that argument to claim the territory, even though it never sent any expedition to the area after the Independence from Spain in 1821, due to the Central American civil war that ensued and lasted until 1860. On the other hand, the British had established a small settlement there since the middle of the 17th century, mainly as buccaneers quarters and then for fine wood production; the settlements were never recognized as British colonies even though they were somewhat under the jurisdiction of the Jamaican British government. In the 18th century, Belize became the main smuggling center for Central America, even though the British accepted Spanish sovereignty over the region by means of the 1783 and 1786 treaties, in exchange for a cease fire and the authorization for the Englishmen to continue logging in Belize.

After the Central America independence from Spain in 1821, Belize became the leading edge of the commercial entrance of Britain in the isthmus; British commercial brokers established themselves there and created prosperous commercial routes with the Caribbean harbors of Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua.

The liberals came to power in Guatemala in 1829 after defeating and expelling the Aycinena family and the

On 30 April 1859, the Wyke-Aycinena treaty was signed

between the English and Guatemalan representatives. The controversial Wyke-Aycinena from 1859 had two parts: * The first six articles clearly defined the Guatemala-Belize border: Guatemala acknowledged England sovereignty over the Belize territory. * The seventh article was about the construction of a road between Belize City and Guatemala City, which would be of mutual benefit, as Belize needed a way to communicate with the Pacific coast of Guatemala, having lost its commercial relevance after the construction of the transoceanic railroad in Panama in 1855; on the other hand, Guatemala needed a road to improve communication with its Atlantic coast. However, the road was never built; first because Guatemalan and Belizeans could not reach an agreement of the exact location for the road, and later because the conservatives lost power in Guatemala in 1871, and the liberal government declared the treaty void. Among those who signed the treaty was

Pedro de Aycinena y PiĂąol (19 October 1802 â 14 May 1897

/ref>) was a Guatemalan conservative politician and member of the Aycinena clan that worked closely with the conservative regime of

and Fernando Lorenzana plenipotentiary -Guatemala Ambassador before the Holy See. Through this treaty -which was designed by Aycinena clan leader, Dr. and clergyman Juan JosĂŠ de Aycinena y PiĂąol - Guatemala placed its people education under the control of Catholic Church regular orders, committed itself to respect Church property and monasteries, authorized mandatory tithing and allowed the bishops to censor whatever was published in the country; in return, Guatemala received blessings for members of the army, allowed those who had acquired the properties that the Liberals had expropriated the Church in 1829 to keep them, perceived taxes generated by the properties of the Church, and had the right, under Guatemalan law, to judge ecclesiastics who perpetrated certain crimes. The concordat was ratified by Pedro de Aycinena and /ref>) was a Guatemalan conservative politician and member of the Aycinena clan that worked closely with the conservative regime of

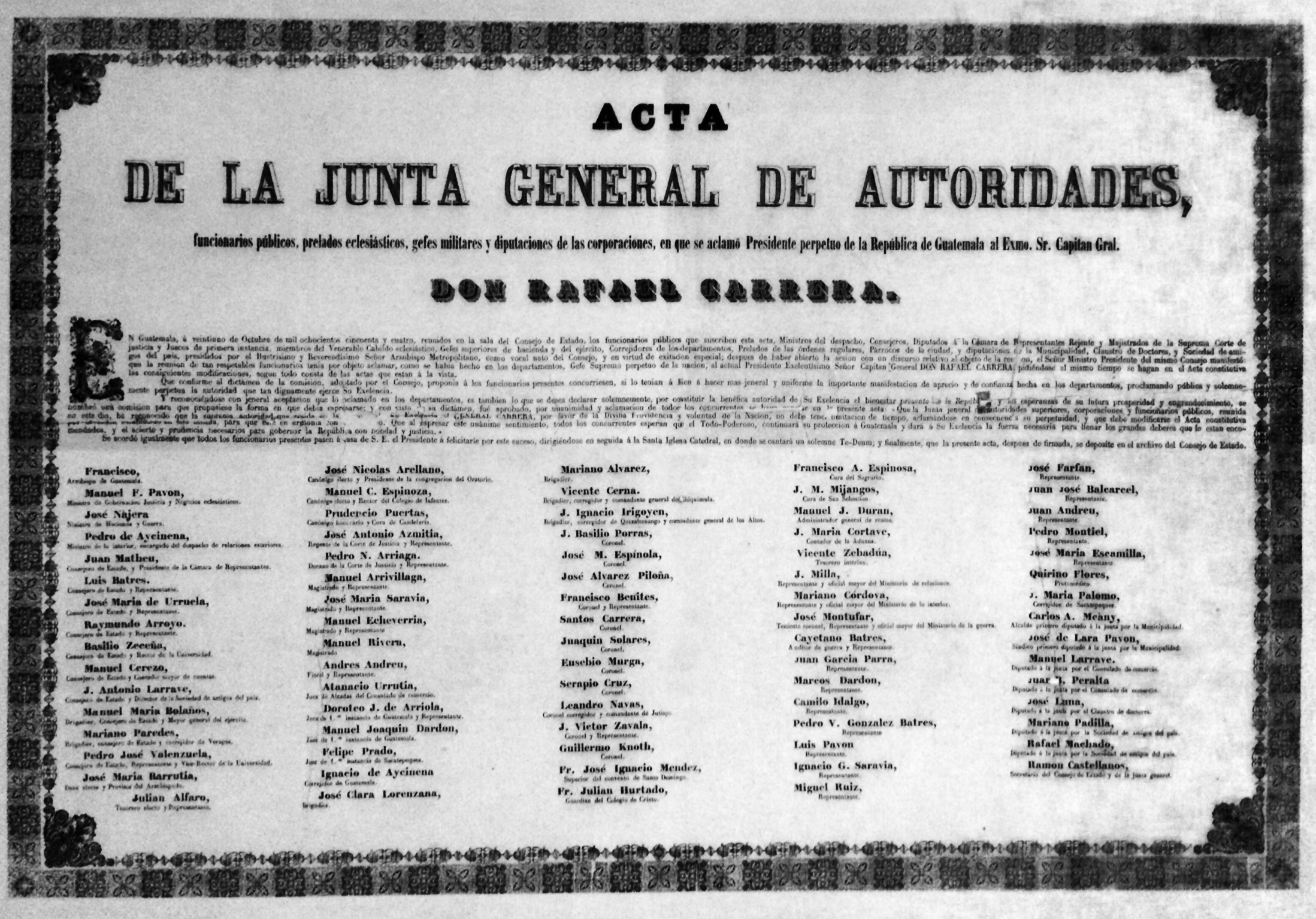

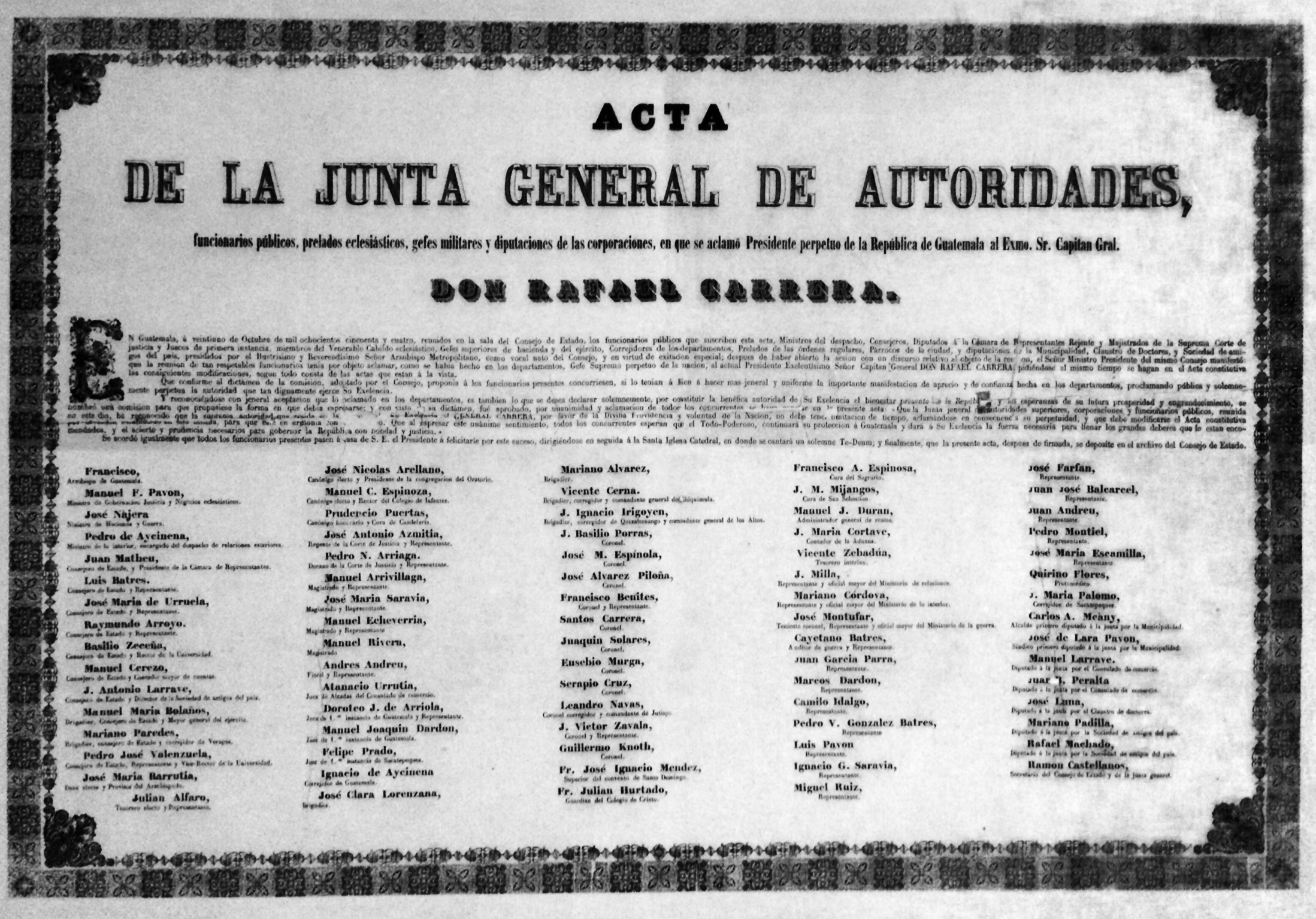

Rafael Carrera

JosĂŠ Rafael Carrera y Turcios (24 October 1814 â 14 April 1865) was the president of Guatemala from 1844 to 1848 and from 1851 until his death in 1865, after being appointed President for life in 1854. He ruled during the establishment of ne ...

. He was interim president of Guatemala

The president of Guatemala (), officially titled President of the Republic of Guatemala (), is the head of state and head of government of Guatemala, elected to a single four-year term. The position of President was created in 1839.

Selectio ...

in 1865 after Carrera's death.

Biography

Aycinena y PiĂąol was the son of Vicente Aycinena, the second marquis of Aycinena, and was the younger brother of cleric Juan JosĂŠ de Aycinena y PiĂąol, who inherited the title. Pedro's uncle wasMariano de Aycinena y PiĂąol

Mariano is a masculine name from the Romance languages, corresponding to the feminine Mariana.

It is an Italian, Spanish and Portuguese variant of the Roman Marianus which derived from Marius, and Marius derived from the Roman god Mars (see als ...

, also prominent member of the powerful family. Pedro married his first cousin, Dolores de Aycinena y Micheo, the daughter of a prominent member of the government of Ferdinand VII

Ferdinand VII (; 14 October 1784 â 29 September 1833) was King of Spain during the early 19th century. He reigned briefly in 1808 and then again from 1813 to his death in 1833. Before 1813 he was known as ''el Deseado'' (the Desired), and af ...

. Pedro served as Guatemalan minister of foreign relations (1854-71) and therefore played a major role in its foreign policy.Richmond F. Brown, "Pedro de Aycinena" in ''Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture'', vol. 1, pp. 247-48. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons 1996.

Concordat of 1854

In 1854 aconcordat

A concordat () is a convention between the Holy See and a sovereign state that defines the relationship between the Catholic Church and the state in matters that concern both,RenĂŠ Metz, ''What is Canon Law?'' (New York: Hawthorn Books, 1960 ...

was established with the Holy See, which was signed in 1852 by Cardinal Antonelli, Secretary of State of the Holy See">Vatican

Vatican may refer to:

Geography

* Vatican City, an independent city-state surrounded by Rome, Italy

* Vatican Hill, in Rome, namesake of Vatican City

* Ager Vaticanus, an alluvial plain in Rome

* Vatican, an unincorporated community in the ...Rafael Carrera

JosĂŠ Rafael Carrera y Turcios (24 October 1814 â 14 April 1865) was the president of Guatemala from 1844 to 1848 and from 1851 until his death in 1865, after being appointed President for life in 1854. He ruled during the establishment of ne ...

in 1854 and kept a close relationship between Church and State in the country; it was in force until the fall of the conservative government of Marshal Vicente Cerna y Cerna

Vicente Cerna y Cerna (22 January 1815 â 27 June 1885) was president of Guatemala from 24 May 1865 to 29 June 1871. Loyal friend and comrade of Rafael Carrera, was appointed army's Field Marshal after Carraera's victory against Salvadorian lea ...

.

Wyke-Aycinena treaty: Limits convention about Belize

The Belize region in the Yucatan Peninsula was never occupied by either Spain or Guatemala, even though Spain made some exploratory expeditions in the 16th century that served as its basis to claim the area; Guatemala simply inherited that argument to claim the territory, even though it never sent any expedition to the area after the Independence from Spain in 1821, due to the Central American civil war that ensued and lasted until 1860. On the other hand, the British had established a small settlement there since the middle of the 17th century, mainly as buccaneers quarters and then for fine wood production; the settlements were never recognized as British colonies even though they were somewhat under the jurisdiction of the Jamaican British government. In the 18th century, Belize became the main smuggling center for Central America, even though the British accepted Spanish sovereignty over the region by means of the 1783 and 1786 treaties, in exchange for a cease fire and the authorization for the Englishmen to continue logging in Belize.

After the Central America independence from Spain in 1821, Belize became the leading edge of the commercial entrance of Britain in the isthmus; British commercial brokers established themselves there and created prosperous commercial routes with the Caribbean harbors of Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua.

The liberals came to power in Guatemala in 1829 after defeating and expelling the Aycinena family and the

The Belize region in the Yucatan Peninsula was never occupied by either Spain or Guatemala, even though Spain made some exploratory expeditions in the 16th century that served as its basis to claim the area; Guatemala simply inherited that argument to claim the territory, even though it never sent any expedition to the area after the Independence from Spain in 1821, due to the Central American civil war that ensued and lasted until 1860. On the other hand, the British had established a small settlement there since the middle of the 17th century, mainly as buccaneers quarters and then for fine wood production; the settlements were never recognized as British colonies even though they were somewhat under the jurisdiction of the Jamaican British government. In the 18th century, Belize became the main smuggling center for Central America, even though the British accepted Spanish sovereignty over the region by means of the 1783 and 1786 treaties, in exchange for a cease fire and the authorization for the Englishmen to continue logging in Belize.

After the Central America independence from Spain in 1821, Belize became the leading edge of the commercial entrance of Britain in the isthmus; British commercial brokers established themselves there and created prosperous commercial routes with the Caribbean harbors of Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua.

The liberals came to power in Guatemala in 1829 after defeating and expelling the Aycinena family and the regular clergy

Regular clergy, or just regulars, are clerics in the Catholic Church who follow a rule () of life, and are therefore also members of religious institutes. Secular clergy are clerics who are not bound by a rule of life.

Terminology and history ...

from the Catholic church, and began a formal complaint before the English crown about the Belize area; at the same time, the liberal caudillo

A ''caudillo'' ( , ; , from Latin language, Latin , diminutive of ''caput'' "head") is a type of Personalist dictatorship, personalist leader wielding military and political power. There is no precise English translation for the term, though it ...

Francisco MorazĂĄn

JosĂŠ Francisco MorazĂĄn Quesada (; born October 3, 1792 â September 15, 1842) was a liberal Central American politician and general who served as president of the Federal Republic of Central America from 1830 to 1839. Before he was president ...

, then president of the Central American Federation

The Federal Republic of Central America (), initially known as the United Provinces of Central America (), was a sovereign state in Central America that existed between 1823 and 1839/1841. The republic was composed of five states (Costa Rica ...

, had personal dealings with British interests, especially on the fine wood market. In Guatemala, liberal governor Mariano GĂĄlvez

JosĂŠ Felipe Mariano GĂĄlvez ( â March 29, 1862 in Mexico) was a jurist and Liberal politician in Guatemala. For two consecutive terms from August 28, 1831, to March 3, 1838, he was chief of state of the State of Guatemala, within the Federal ...

made several land concessions to British citizens, among them the best farmland in the country, Hacienda de San JerĂłnimo in Verapaz; these dealings with Englishmen were used by the secular clergy

In Christianity, the term secular clergy refers to deacons and priests who are not monastics or otherwise members of religious life. Secular priests (sometimes known as diocesan priests) are priests who commit themselves to a certain geograph ...

in Guatemala â who had not been expelled as the monasteries, but had lost the revenue from mandatory tithing which had left it weakened â to accuse the liberal government of heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, particularly the accepted beliefs or religious law of a religious organization. A heretic is a proponent of heresy.

Heresy in Heresy in Christian ...

and to start a peasant revolt against the heretic liberals and in favor of the "true religion". When Rafael Carrera

JosĂŠ Rafael Carrera y Turcios (24 October 1814 â 14 April 1865) was the president of Guatemala from 1844 to 1848 and from 1851 until his death in 1865, after being appointed President for life in 1854. He ruled during the establishment of ne ...

, peasant revolt leader and commander, came to power in 1840, he stopped the complaints over Belize, and established a Guatemalan consulate in the region to oversee the Guatemalan interests in that important commercial location. Belize commerce was booming in the region until 1855, when the Colombians built a transoceanic railway, which allowed commerce to flow more efficiently to the port at the Pacific; from then on, Belize's commercial importance began a steep decline.

When the Caste War of YucatĂĄn

The Caste War of YucatĂĄn or ''ba'atabil kichkelem YĂşum'' (1847â1915) began with the revolt of Indigenous peoples of Mexico, indigenous Maya peoples, Maya people of the YucatĂĄn Peninsula against Hispanic populations, called ''Yucatecos''. Th ...

began in 1847 in the Yucatan Peninsula â a Maya uprising that resulted in thousands of murdered European settlers â the representatives of Belize and Guatemala were on high alert; Yucatan refugees fled into both Guatemala and Belize and even the Belize superintendent came to fear that Carrera â given his strong alliance with Guatemalan natives â could support the native uprisings in Central America. In the 1850s, the British showed their good will to settle the territorial differences with the Central American countries: they withdrew from the Mosquito Coast in Nicaragua

Nicaragua, officially the Republic of Nicaragua, is the geographically largest Sovereign state, country in Central America, comprising . With a population of 7,142,529 as of 2024, it is the third-most populous country in Central America aft ...

and began talks that would end up in the restoration of the territory to Nicaragua in 1894: returned the Bay Islands to Honduras

Honduras, officially the Republic of Honduras, is a country in Central America. It is bordered to the west by Guatemala, to the southwest by El Salvador, to the southeast by Nicaragua, to the south by the Pacific Ocean at the Gulf of Fonseca, ...

and even negotiated with the American filibuster William Walker William Walker may refer to:

Arts

* William Walker (engraver) (1791â1867), mezzotint engraver of portrait of Robert Burns

* William Sidney Walker (1795â1846), English Shakespearean critic

* William Walker (composer) (1809â1875), American Bap ...

in an effort to avoid the invasion of Honduras. They also signed a treaty with Guatemala about its border with Belize, which has been called by Guatemalans the worst mistake made by the conservative regime of Rafael Carrera.

Aycinena y PiĂąol, as Foreign Secretary, had made an extra effort to keep good relations with the British crown. In 1859, William Walker's threat loomed again over Central America; in order to get the weapons needed to face the filibuster, Carrera's regime had to come to terms about Belize with the British EmpireOn 30 April 1859, the Wyke-Aycinena treaty was signed

between the English and Guatemalan representatives. The controversial Wyke-Aycinena from 1859 had two parts: * The first six articles clearly defined the Guatemala-Belize border: Guatemala acknowledged England sovereignty over the Belize territory. * The seventh article was about the construction of a road between Belize City and Guatemala City, which would be of mutual benefit, as Belize needed a way to communicate with the Pacific coast of Guatemala, having lost its commercial relevance after the construction of the transoceanic railroad in Panama in 1855; on the other hand, Guatemala needed a road to improve communication with its Atlantic coast. However, the road was never built; first because Guatemalan and Belizeans could not reach an agreement of the exact location for the road, and later because the conservatives lost power in Guatemala in 1871, and the liberal government declared the treaty void. Among those who signed the treaty was

JosĂŠ Milla y Vidaurre

JosĂŠ Milla y Vidaurre (August 4, 1822 in Guatemala City, First Mexican Empire â Guatemala City, Guatemala September 30, 1882) was a notable Guatemalan writer of the 19th century. He was also known by the name Pepe Milla and the pseudonym SalomĂ ...

, who worked with Aycinena in the Foreign Ministry. Rafael Carrera ratified the treaty on 1 May 1859, while Charles Lennox Wyke, British consul in Guatemala, traveled to Great Britain and received the royal approval on 26 September 1859. There were some protests coming from the U.S. consul, Beverly Clarke, and some liberal representatives, but the issue was settled.

See also

*Concordat of 1854

The Concordat between the Holy See and the President of the Republic of Guatemala (), referred to colloquially as the Concordat of 1854 (), was a concordat between ... between Rafael Carrera, President of Guatemala, and the Holy See">Rafael Carr ...

* Juan JosĂŠ de Aycinena y PiĂąol

* Rafael Carrera

JosĂŠ Rafael Carrera y Turcios (24 October 1814 â 14 April 1865) was the president of Guatemala from 1844 to 1848 and from 1851 until his death in 1865, after being appointed President for life in 1854. He ruled during the establishment of ne ...

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * *External links

*Notes

{{DEFAULTSORT:Aycinena y Pinol, Pedro 1802 births 1897 deaths Presidents of Guatemala Rafael Carrera Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala alumni Conservative Party (Guatemala) politicians 19th-century Guatemalan people Aycinena family Ministers of foreign affairs of Guatemala