Paweł Strzelecki on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Paweł Edmund Strzelecki (;By Australian English speakers: pɔːl strʌzlɛki (paul struhzLECKi). 20 July 17976 October 1873), also known as Paul Edmund de Strzelecki and Sir Paul Strzelecki, was a Polish explorer, geologist, humanitarian, environmentalist, nobleman, scientist, businessman and philanthropist who in 1845 also became a British subject.

He is noted for his contributions to the exploration of

He arrived at Sydney on 25 April 1839. He visited the estate of his friend James Macarthur at Camden. He wrote about meeting the German

He arrived at Sydney on 25 April 1839. He visited the estate of his friend James Macarthur at Camden. He wrote about meeting the German

In Australia

* Strzelecki Ranges, Victoria, in which is located the township of Strzelecki. The Strzelecki railway line ran through the ranges to the township.

*Mount Strzelecki,

In Australia

* Strzelecki Ranges, Victoria, in which is located the township of Strzelecki. The Strzelecki railway line ran through the ranges to the township.

*Mount Strzelecki,

Mt Kosciuszko Inc.

an organisation of Polish emigrants, was established in

Paweł Edmund Strzelecki

Prominent Poles

{{DEFAULTSORT:Strzelecki, Paul Edmund Polish explorers 19th-century Polish geologists Polish geographers Explorers of Australia Australian geologists Fellows of the Royal Society Fellows of the Royal Geographical Society 19th-century Polish nobility Companions of the Order of the Bath Knights Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George 1797 births 1873 deaths People from the Province of Posen Burials at Kensal Green Cemetery Polish emigrants to Australia People from Poznań

Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

, particularly the Snowy Mountains

The Snowy Mountains, known informally as "The Snowies", is an IBRA subregion in southern New South Wales, Australia, and is the tallest mountain range in mainland Australia, being part of the continent's Great Dividing Range, a cordillera syste ...

and Tasmania

Tasmania (; palawa kani: ''Lutruwita'') is an island States and territories of Australia, state of Australia. It is located to the south of the Mainland Australia, Australian mainland, and is separated from it by the Bass Strait. The sta ...

, and for climbing and naming the highest – – mountain on the continent, Mount Kosciuszko

Mount Kosciuszko ( ; ; Ngarigo: ) is the highest mountain of the mainland Australia, at above sea level. It is located on the Main Range of the Snowy Mountains in Kosciuszko National Park, a part of the Australian Alps National Parks and ...

.

Early years

Strzelecki was born in 1797, in Głuszyna nearPoznań

Poznań ( ) is a city on the Warta, River Warta in west Poland, within the Greater Poland region. The city is an important cultural and business center and one of Poland's most populous regions with many regional customs such as Saint John's ...

(Posen), in the Polish territory occupied by the Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (, ) was a German state that existed from 1701 to 1918.Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. Rev. ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1946. It played a signif ...

. He was the third child of Franciszek Strzelecki and Anna née Raczyńska, both from Polish nobility (szlachta

The ''szlachta'' (; ; ) were the nobility, noble estate of the realm in the Kingdom of Poland, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Depending on the definition, they were either a warrior "caste" or a social ...

), who leased the Głuszyna estate at the time. In Australia, Strzelecki was referred to as Count though there is no proof that he actually approved or used such a title himself.

As Poznań was then under Prussian control, Strzelecki was a Prussian citizen. He left school without matriculating, then served briefly in the Prussian Army in the 6th Regiment of Thuringia

Thuringia (; officially the Free State of Thuringia, ) is one of Germany, Germany's 16 States of Germany, states. With 2.1 million people, it is 12th-largest by population, and with 16,171 square kilometers, it is 11th-largest in area.

Er ...

n Uhlan

Uhlan (; ; ; ; ) is a type of light cavalry, primarily armed with a lance. The uhlans started as Grand Ducal Lithuanian Army, Lithuanian irregular cavalry, that were later also adopted by other countries during the 18th century, including Polis ...

s, at the time known as the Polish Regiment because the majority of the staff were Poles

Pole or poles may refer to:

People

*Poles (people), another term for Polish people, from the country of Poland

* Pole (surname), including a list of people with the name

* Pole (musician) (Stefan Betke, born 1967), German electronic music artist

...

. Strzelecki submitted his resignation due to the strict Prussian discipline that he did not approve of. There are some suggestions that he deserted the Regiment but in the official history of the Regiment the name Strzelecki does not appear. Not long after, he became a tutor at a manor of local nobility. He fell in love with his young student, a girl of 15, Aleksandryn (Adyna) Turno, but was rejected as a suitor by her father, Adam Turno. There are stories that Strzelecki attempted unsuccessfully to elope with Adyna, but biographers find this unlikely. Adyna and Strzelecki exchanged letters over 40 years but they never married. Provided with funds by his family, Strzelecki travelled in Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

and Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

. He eventually came under the notice of the Polish Prince Franciszek Sapieha who placed him in charge of his large estate in the Russian-occupied part of Poland. Strzelecki was then about 26 years of age and carried out his duties very successfully. Some years later the prince died, and a dispute arose between his son and heir, Eustace, and Strzelecki. Eustace refused to pay Strzelecki the prince's bequest – a huge sum of money and a considerable estate – accusing him of bad faith and prevarication. After four years the dispute was settled. Strzelecki left Poland about 1829 and stayed some time in France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, from where he travelled to Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

.

He had no formal training in geology, a science then in its infancy in England, but was probably, like his English contemporaries, self taught.

On 8 June 1834, he sailed from Liverpool

Liverpool is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. It is situated on the eastern side of the River Mersey, Mersey Estuary, near the Irish Sea, north-west of London. With a population ...

to New York. He travelled widely in North America, analysing soil, examining minerals (tradition claims he discovered copper in Canada), and visiting farms to study soil conservation and to analyse the gluten content of wheat. In South America in 1836 he visited the most important mineral areas and he went up the west coast from Chile to California. During this time he became a strong opponent of the slave trade. He went to Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

, Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian language, Tahitian , ; ) is the largest island of the Windward Islands (Society Islands), Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia, an overseas collectivity of France. It is located in the central part of t ...

and the South Sea Islands, and came to New Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

probably about the beginning of 1839.

Australia

He arrived at Sydney on 25 April 1839. He visited the estate of his friend James Macarthur at Camden. He wrote about meeting the German

He arrived at Sydney on 25 April 1839. He visited the estate of his friend James Macarthur at Camden. He wrote about meeting the German vintners

A winemaker or vintner is a person engaged in winemaking. They are generally employed by wineries or wine companies, where their work includes:

*Cooperating with viticulturists

*Monitoring the maturity of grapes to ensure their quality and to de ...

that the Macarthurs had brought to Australia from the Rheingau

The Rheingau (; ) is a region on the northern side of the Rhine between the German towns of Wiesbaden and Lorch, Hesse, Lorch near Frankfurt, reaching from the Western Taunus to the Rhine. It is situated in the German state of Hesse and is part ...

region. He wrote: "I had gone with my host to look at the farm, the fields, and the vineyard,—contiguous to which last stood in a row six neat cottages, surrounded with kitchen gardens, and inhabited by six families of German vine-dressers, who emigrated two years ago to New South Wales, either driven there by necessity, or seduced by the hope of finding, beyond the sea, fortune, peace, and happiness,—perhaps justice and liberty. The German salutation which I gave to the group that stood nearest, was like some signal-bell, which instantly set the whole colony in motion. Fathers, mothers, and children came running from all sides to see, to salute, and to talk to the gentleman who came from Germany. They took me for their fellow-countryman, and were happy, questioning me about Germany, the Rhine, and their native town. I was far from undeceiving them."

His main interest was the mineralogy of Australia. In September he discovered gold and silver near Wellington (NSW) and in the Vale of Clwyd, in the vicinity of Hartley

Hartley may refer to:

Places Australia

*Hartley, New South Wales

* Hartley, South Australia

** Electoral district of Hartley, a state electoral district

Canada

* Hartley Bay, British Columbia

United Kingdom

* Hartley, Cumbria

* Hartley, P ...

. He collected there numerous samples of Australian gold, which were sent to the eminent geologist Sir Roderick Murchison of London, and also to Berlin, but the Governor of New South Wales, Sir George Gipps

Sir George Gipps (23 December 1790 – 28 February 1847) was the Governor of New South Wales, Governor of the British Colony of New South Wales for eight years, between 1838 and 1846. His governorship oversaw a tumultuous period where the rights ...

, fearing unrest among 45,000 convicts, stifled the news about the discovery.

Later in 1839 Strzelecki set out on an expedition into the Australian Alps

The Australian Alps are a mountain range in southeast Australia. The range comprises an Interim Biogeographic Regionalisation for Australia, interim Australian bioregion,

and explored the Snowy Mountains

The Snowy Mountains, known informally as "The Snowies", is an IBRA subregion in southern New South Wales, Australia, and is the tallest mountain range in mainland Australia, being part of the continent's Great Dividing Range, a cordillera syste ...

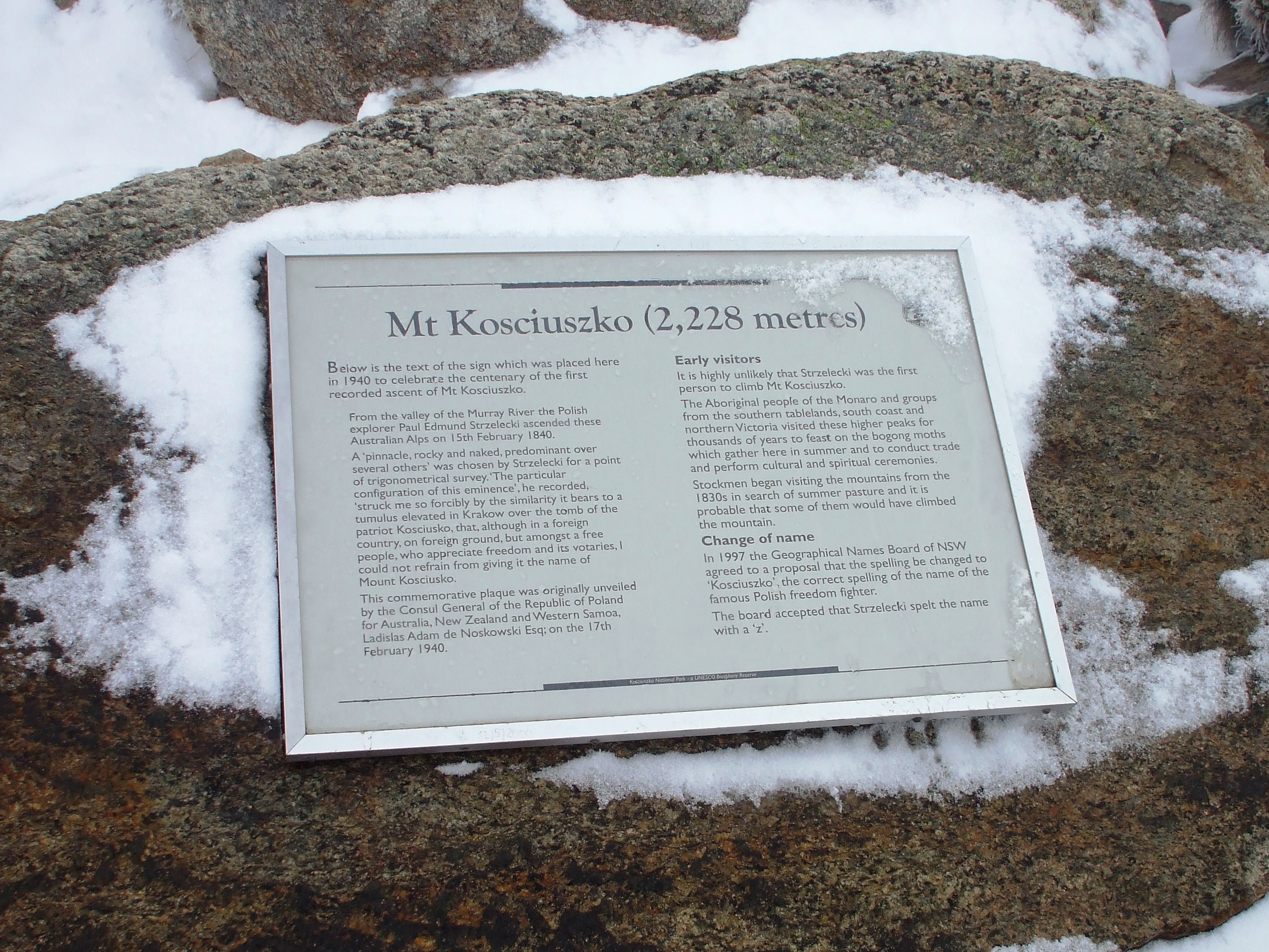

with James Macarthur, James Riley and two Aboriginal guides: Charlie Tarra and Jackey. In 1840 he climbed the highest peak on mainland Australia and named it Mount Kosciuszko

Mount Kosciuszko ( ; ; Ngarigo: ) is the highest mountain of the mainland Australia, at above sea level. It is located on the Main Range of the Snowy Mountains in Kosciuszko National Park, a part of the Australian Alps National Parks and ...

, to honour Tadeusz Kościuszko

Andrzej Tadeusz Bonawentura Kościuszko (; 4 or 12 February 174615 October 1817) was a Polish Military engineering, military engineer, statesman, and military leader who then became a national hero in Poland, the United States, Lithuania, and ...

, one of the national heroes of Poland and a hero of the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

. On Victorian maps (but never on New South Wales maps) the name Mount Kosciusko was erroneously connected to the neighbouring peak, at present known as Mount Townsend and causing later many confusions, including the recent incorrect information on swapping the names of the mountains. From there Strzelecki explored Gippsland

Gippsland () is a rural region in the southeastern part of Victoria, Australia, mostly comprising the coastal plains south of the Victorian Alps (the southernmost section of the Great Dividing Range). It covers an elongated area of east of th ...

which he named after the governor. After passing the La Trobe River it was found necessary to abandon the horses and all the specimens that had been collected and try to reach Western Port

Western Port, ( Boonwurrung: ''Warn Marin'') commonly but unofficially known as Western Port Bay, is a large tidal bay in southern Victoria, Australia, opening into Bass Strait. It is the second largest bay in the state. Geographically, it ...

. For 22 days they were on the edge of starvation and were ultimately saved by the knowledge and hunting ability of their guide Charlie, who caught native animals for them to eat. The party, practically exhausted, arrived at Western Port on 12 May 1840 and reached Melbourne

Melbourne ( , ; Boonwurrung language, Boonwurrung/ or ) is the List of Australian capital cities, capital and List of cities in Australia by population, most populous city of the States and territories of Australia, Australian state of Victori ...

on 28 May. The Strzelecki Ranges are named in his honour.

From 1840 to 1842, based in Launceston, Tasmania (then known as Van Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land was the colonial name of the island of Tasmania during the European exploration of Australia, European exploration and colonisation of Australia in the 19th century. The Aboriginal Tasmanians, Aboriginal-inhabited island wa ...

), Strzelecki explored nearly every part of the island, usually on foot with three men and two pack horses. His friends, the Lieutenant-Governor

A lieutenant governor, lieutenant-governor, or vice governor is a high officer of state, whose precise role and rank vary by jurisdiction. Often a lieutenant governor is the deputy, or lieutenant, to or ranked under a governor — a " second-in-com ...

, Sir John Franklin

Sir John Franklin (16 April 1786 – 11 June 1847) was a British Royal Navy officer, explorer and colonial administrator. After serving in the Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812, he led two expeditions into the Northern Canada, Canadia ...

, and his wife, Lady Jane, afforded him every help in his scientific endeavours.

Strzelecki left Tasmania on 29 September 1842 by steamer and arrived in Sydney on 2 October. He was collecting specimens in northern New South Wales towards the end of that year, and on 22 April 1843, he left Sydney after having travelled through New South Wales, Victoria and Tasmania, examining the geology along the way. He went to England after visiting China, the East Indies

The East Indies (or simply the Indies) is a term used in historical narratives of the Age of Discovery. The ''Indies'' broadly referred to various lands in Eastern world, the East or the Eastern Hemisphere, particularly the islands and mainl ...

and Egypt.

In 1845 he published his ''Physical Description of New South Wales and Van Diemen's Land''. The book gained the praise of Charles Darwin and other scientists and was awarded the Founder's Medal

The Founder's Medal is a medal awarded annually by the Royal Geographical Society, upon approval of the Sovereign of the United Kingdom, to individuals for "the encouragement and promotion of geographical science and discovery".

Foundation

From ...

of the Royal Geographical Society

The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), often shortened to RGS, is a learned society and professional body for geography based in the United Kingdom. Founded in 1830 for the advancement of geographical scien ...

. It was an unsurpassed source of knowledge on Australia for at least forty-five years. In it, he describes terra nullius

''Terra nullius'' (, plural ''terrae nullius'') is a Latin expression meaning " nobody's land".

Since the nineteenth century it has occasionally been used in international law as a principle to justify claims that territory may be acquired ...

as a "sophistry of law" and writes that Aboriginal Australians

Aboriginal Australians are the various indigenous peoples of the Mainland Australia, Australian mainland and many of its islands, excluding the ethnically distinct people of the Torres Strait Islands.

Humans first migrated to Australia (co ...

are "as strongly attached to... property, and the rights which it involves, as any European political body." He also published the first map of Gippsland and its description which helped to open up this fertile part of Victoria. He produced the first large geological map of Eastern Australia and Tasmania.

In 1845 he became a naturalised British subject.

Philanthropy

During the autumn and winter of 1846–47 the disaster of the great famine came to Ireland. In January 1847, a group of English banking leaders combined to raise funds for famine relief via a private charity named the “British Relief Association

The British Association for the Relief of Distress in Ireland and the Highlands of Scotland, known as the British Relief Association (BRA), was a private charity of the mid-19th century in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Establis ...

” and entrusted Strzelecki to dispense them (£500,000). Strzelecki was appointed the main agent of the Association to superintend the distribution of supplies in County Sligo

County Sligo ( , ) is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is in the Northern and Western Region and is part of the Provinces of Ireland, province of Connacht. Sligo is the administrative capital and largest town in ...

, County Mayo

County Mayo (; ) is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. In the West Region, Ireland, West of Ireland, in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Connacht, it is named after the village of Mayo, County Mayo, Mayo, now ge ...

and County Donegal

County Donegal ( ; ) is a Counties of Ireland, county of the Republic of Ireland. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Ulster and is the northernmost county of Ireland. The county mostly borders Northern Ireland, sharing only a small b ...

. In order to alleviate the critical situation of famished Irish families and especially children, Strzelecki developed a visionary and exceptionally effective mode of assistance: feeding starving children directly through the schools. He extended daily food rations to schoolchildren across the most famine-stricken western part of Ireland, while also distributing clothing and promoting basic hygiene. At its peak in 1848, around 200,000 children from all denominations were being fed through the efforts of the B.R.A., many of whom would have otherwise perished from hunger and disease. Despite suffering from the effects of typhoid fever he contracted in Ireland, Strzelecki dedicated himself tirelessly to hunger relief. His commitment was widely recognized and praised by his contemporaries. In recognition of his services, he was made a Companion of the Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by King George I of Great Britain, George I on 18 May 1725. Recipients of the Order are usually senior British Armed Forces, military officers or senior Civil Service ...

(CB) in November 1848.

Strzelecki helped impoverished Irish families to seek new lives in Australia. He was, for many years, an active member of Family Colonisation Loan Society, originated by Caroline Chisholm

Caroline Chisholm ( ; born Caroline Jones; 30 May 1808 – 25 March 1877) was an English humanitarian known mostly for her support of immigrant female and family welfare in Australia. She is commemorated on 16 May in the Calendar of saints (Ch ...

and in 1854 was its chairman, fulfilling his duties with great zeal.

He was also an esteemed member of Lord Herbert's Emigration Committee and of the Duke of Wellington's Emigration Committee. He was, additionally, a member of the Crimean Army Fund Committee. At the end of the Crimean campaign he accompanied Lord Lyons on a visit to Sevastopol. Strzelecki was also associated with Florence Nightingale

Florence Nightingale (; 12 May 1820 – 13 August 1910) was an English Reform movement, social reformer, statistician and the founder of modern nursing. Nightingale came to prominence while serving as a manager and trainer of nurses during th ...

and helped her in facilitating the publication of a series of her articles.

He died of liver cancer in London in 1873 and was buried in Kensal Green Cemetery

Kensal Green Cemetery is a cemetery in the Kensal Green area of North Kensington in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea and the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham in London, England. Inspired by Père Lachaise Cemetery in P ...

. In 1997 his remains were transferred to the crypt of merit at the Church of St. Adalbert in his hometown of Poznań

Poznań ( ) is a city on the Warta, River Warta in west Poland, within the Greater Poland region. The city is an important cultural and business center and one of Poland's most populous regions with many regional customs such as Saint John's ...

, Poland.

Awards and honours

Strzelecki was made afellow

A fellow is a title and form of address for distinguished, learned, or skilled individuals in academia, medicine, research, and industry. The exact meaning of the term differs in each field. In learned society, learned or professional society, p ...

of the Royal Geographical Society

The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), often shortened to RGS, is a learned society and professional body for geography based in the United Kingdom. Founded in 1830 for the advancement of geographical scien ...

and was awarded its Founder's Medal

The Founder's Medal is a medal awarded annually by the Royal Geographical Society, upon approval of the Sovereign of the United Kingdom, to individuals for "the encouragement and promotion of geographical science and discovery".

Foundation

From ...

for "exploration in the south eastern portion of Australia". The Society still displays his huge geological map of New South Wales and Tasmania for public viewing.

He was also appointed a Fellow of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

, having gained widespread recognition as an explorer and philanthropist.

He was awarded an honorary degree of Doctor of Civil Law from the University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a collegiate university, collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the List of oldest un ...

, appointed Companion of the Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by King George I of Great Britain, George I on 18 May 1725. Recipients of the Order are usually senior British Armed Forces, military officers or senior Civil Service ...

(CB) in 1849, and appointed Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George

The Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George is a British order of chivalry founded on 28 April 1818 by George, Prince of Wales (the future King George IV), while he was acting as prince regent for his father, King George III ...

(KCMG) in 1869.

In 1983 he was honoured on a postage stamp depicting his portrait issued by Australia Post

Australia Post, formally the Australian Postal Corporation and also known as AusPost, is an Australian Government-State-owned enterprise, owned corporation that provides postal services throughout Australia. Australia Post's head office is loca ...

.

In 2023, the city of Poznań

Poznań ( ) is a city on the Warta, River Warta in west Poland, within the Greater Poland region. The city is an important cultural and business center and one of Poland's most populous regions with many regional customs such as Saint John's ...

declared 2023 as "The Year of Strzelecki" in order to honour and celebrate the life of the explorer and his accomplishments.

Named after him

Northern Territory

The Northern Territory (abbreviated as NT; known formally as the Northern Territory of Australia and informally as the Territory) is an states and territories of Australia, Australian internal territory in the central and central-northern regi ...

*Strzelecki Peak, Flinders Island

Flinders Island, the largest island in the Furneaux Group, is a island in the Bass Strait, northeast of the island of Tasmania. Today Flinders Island is part of the state of Tasmania, Australia. It is from Cape Portland, Tasmania, Cape Portl ...

* Strzelecki Creek, South Australia

*Strzelecki Highway, Victoria

*Strzelecki Track

Strzelecki Track is a mostly unsealed outback track in South Australia, linking Innamincka, South Australia, Innamincka to Lyndhurst, South Australia, Lyndhurst.

History

In 1870, the track was pioneered by Stockman (Australia), stockman, D ...

, South Australia

* Strzelecki Desert, east of Lake Eyre

Lake Eyre ( ), officially known as Kati Thanda–Lake Eyre, is an endorheic lake in the east-central part of the Far North (South Australia), Far North region of South Australia, some 700 km (435 mi) north of Adelaide. It is the larg ...

in South Australia

*Strzelecki Scenic Lookout, Newcastle, New South Wales

Newcastle, also commonly referred to as Greater Newcastle ( ; ), is a large Metropolitan area, metropolitan area and the second-most-populous such area of New South Wales, Australia. It includes the cities of City of Newcastle, Newcastle and Ci ...

In Canada

*Strzelecki Harbour

Writing

* ''Physical Description of New South Wales. Accompanied by a Geological Map, Sections and Diagrams, and Figures of the Organic Remains'' (London, 1845).See also

*List of Poles

This is a partial list of notable Polish people, Polish or Polish language, Polish-speaking or -writing people. People of partial Polish heritage have their respective ancestries credited.

Physics

*Miedziak Antal

* Czesław Białobrzesk ...

* Poles in the United Kingdom

British Poles, alternatively known as Polish British people or Polish Britons, are ethnic Poles who are citizens of the United Kingdom. The term includes people born in the UK who are of Polish descent and Polish-born people who reside in the ...

* Timeline of Polish science and technology

Notes

References

Sources *''Sir Paul Edmund de Strzelecki. Reflections of his life ''by Lech Paszkowski, Australian Scholarly Publishing, 1997, *''Kosciusko The Mountain in History'' by Alan E.J. Andrews Tabletop Press, Canberra 1991, *''Paul Edmund Strzelecki and His Team. Achieving Together'' by Ernestyna Skurjat-Kozek & Lukasz Swiatek, FKPP, Sydney 2009, *''Sir Paul E. Strzelecki: A Polish Count's Explorations in 19th Century Australia'' by Marian Kałuski, A E Press, Melbourne, 1985,External links

*Mt Kosciuszko Inc.

an organisation of Polish emigrants, was established in

Perth

Perth () is the list of Australian capital cities, capital city of Western Australia. It is the list of cities in Australia by population, fourth-most-populous city in Australia, with a population of over 2.3 million within Greater Perth . The ...

, Western Australia, in 2002 to raise public interest in the early history of Mount Kosciuszko and Strzelecki's cultural contributions.

Paweł Edmund Strzelecki

Prominent Poles

{{DEFAULTSORT:Strzelecki, Paul Edmund Polish explorers 19th-century Polish geologists Polish geographers Explorers of Australia Australian geologists Fellows of the Royal Society Fellows of the Royal Geographical Society 19th-century Polish nobility Companions of the Order of the Bath Knights Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George 1797 births 1873 deaths People from the Province of Posen Burials at Kensal Green Cemetery Polish emigrants to Australia People from Poznań