Patriot's Park on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Patriot's Park (originally referred to as Brookside Park) is located on

Opposite the entrance curving stone steps, along with a sloped walkway from the south, lead down from battered stone piers at either end of a

Opposite the entrance curving stone steps, along with a sloped walkway from the south, lead down from battered stone piers at either end of a

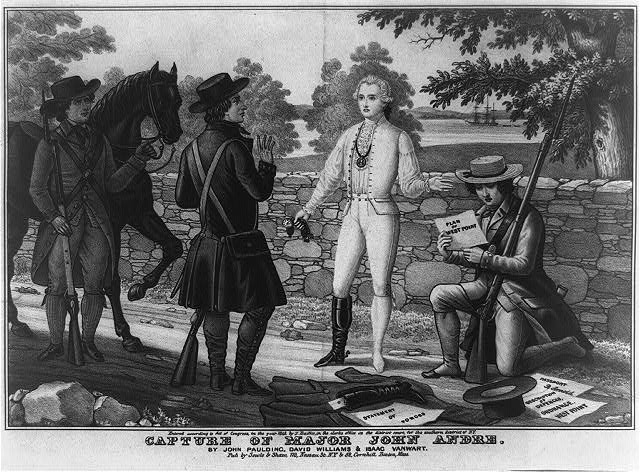

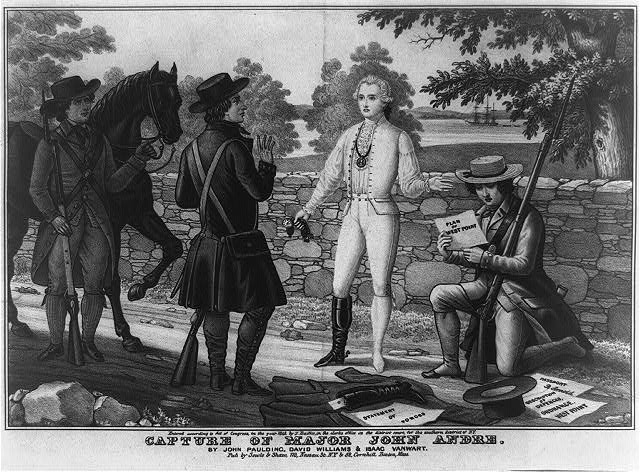

Paulding, who had recently escaped from British custody, wore a Hessian coat he had taken in the process, which led André to assume, in the ensuing conversation, that the three were Cow-boys who could thus aid him in continuing on to New York. When informed of his mistake, he produced a pass signed by Arnold. The three searched him and found papers in his boots, not only his correspondence with Arnold but diagrams of the defenses at West Point. Paulding, the only literate member of the trio, read them and realized quickly that André was a spy. Williams asked André what money he could pay them, but Paulding quickly ended any talk of a payoff, swearing that not even 10,000

Paulding, who had recently escaped from British custody, wore a Hessian coat he had taken in the process, which led André to assume, in the ensuing conversation, that the three were Cow-boys who could thus aid him in continuing on to New York. When informed of his mistake, he produced a pass signed by Arnold. The three searched him and found papers in his boots, not only his correspondence with Arnold but diagrams of the defenses at West Point. Paulding, the only literate member of the trio, read them and realized quickly that André was a spy. Williams asked André what money he could pay them, but Paulding quickly ended any talk of a payoff, swearing that not even 10,000

On the centennial of the capture in 1880, the monument was expanded and rededicated. A crowd of 70,000 attended the ceremony, presided over by Samuel J. Tilden (one of his last public appearances) and

On the centennial of the capture in 1880, the monument was expanded and rededicated. A crowd of 70,000 attended the ceremony, presided over by Samuel J. Tilden (one of his last public appearances) and

U.S. Route 9

U.S. Route 9 (US 9) is a north–south United States Numbered Highway in the states of Delaware, New Jersey, and New York in the Northeastern United States. It is one of only two U.S. Highways with a ferry connection (the Cape May–Le ...

along the boundary between Tarrytown

Tarrytown is a village in the town of Greenburgh in Westchester County, New York, United States. It is located on the eastern bank of the Hudson River, approximately north of Midtown Manhattan in New York City, and is served by a stop on th ...

and Sleepy Hollow in Westchester County

Westchester County is a county located in the southeastern portion of the U.S. state of New York, bordering the Long Island Sound and the Byram River to its east and the Hudson River on its west. The county is the seventh most populous cou ...

, New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

, United States. It is a four-acre (1.6-ha) parcel with a walkway and several monuments. In 1982 it was added to the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government's official United States National Register of Historic Places listings, list of sites, buildings, structures, Hist ...

.

Overview

During theAmerican Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

Major John André

Major John André (May 2, 1750 – October 2, 1780) was a British Army officer who served as the head of Britain's intelligence operations during the American War for Independence. In September 1780, he negotiated with Continental Army offic ...

of the British Army was captured, disguised in civilian clothing, at the site by three Patriot

A patriot is a person with the quality of patriotism.

Patriot(s) or The Patriot(s) may also refer to:

Political and military groups United States

* Patriot (American Revolution), those who supported the cause of independence in the American R ...

militiamen. They found papers on him that implicated him in espionage with Benedict Arnold

Benedict Arnold (#Brandt, Brandt (1994), p. 4June 14, 1801) was an American-born British military officer who served during the American Revolutionary War. He fought with distinction for the American Continental Army and rose to the rank of ...

, a high-ranking officer of the Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies representing the Thirteen Colonies and later the United States during the American Revolutionary War. It was formed on June 14, 1775, by a resolution passed by the Second Continental Co ...

. After a military trial André was executed; Arnold defected

In politics, a defector is a person who gives up allegiance to one state in exchange for allegiance to another, changing sides in a way which is considered illegitimate by the first state. More broadly, defection involves abandoning a person, ca ...

to the British and lived his remaining years after the war in England.

A memorial was erected on the site in 1853, on land donated by some members of the local African American

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from an ...

community. It was one of the earliest monuments to honor any event of the Revolutionary War. Later it was expanded and incorporated into Brookside Park, a late 19th-century Beaux-Arts residential development by the firm of Carrère and Hastings

Carrère and Hastings, the firm of John Merven Carrère ( ; November 9, 1858 – March 1, 1911) and Thomas Hastings (architect), Thomas Hastings (March 11, 1860 – October 22, 1929), was an American list of architecture firms, architecture firm ...

. Later it became the campus of two different girls' boarding schools, one of which was attended by Lauren Bacall

Betty Joan Perske (September 16, 1924 – August 12, 2014), professionally known as Lauren Bacall ( ), was an American actress. She was named the AFI's 100 Years...100 Stars, 20th-greatest female star of classic Hollywood cinema by the America ...

. It became a park and took its current name in the middle of the 20th century, and all buildings but the gatehouse

A gatehouse is a type of fortified gateway, an entry control point building, enclosing or accompanying a gateway for a town, religious house, castle, manor house, or other fortification building of importance. Gatehouses are typically the most ...

were demolished.

Grounds

The park is a four-acre (1.6 ha) parcel located between North Broadway (Route 9) on its east, North Washington Street to the west and College Avenue on the north. The southwest corner has some houses continuing down to Wildey Street; Tarrytown's public library is to the southeast. Across North Washington are more houses, which continue to the College intersection at the northwest. Church of the Immaculate Conception is across from the park at College and North Broadway. To the east is the large open lawn of John Paulding School, the publicelementary

Elementary may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Music

* ''Elementary'' (Cindy Morgan album), 2001

* ''Elementary'' (The End album), 2007

* ''Elementary'', a Melvin "Wah-Wah Watson" Ragin album, 1977

Other uses in arts, entertainment, an ...

school of the Union Free School District of the Tarrytowns, which has its headquarters north of the school in the former Edward Harden Mansion

The Edward Harden Mansion, also known as Broad Oaks, is a historic home located on North Broadway ( U.S. Route 9) in Sleepy Hollow, New York, United States, on the boundary between it and neighboring Tarrytown. It is a brick building in the G ...

, also listed on the National Register. Behind them runs the Old Croton Aqueduct

The Croton Aqueduct or Old Croton Aqueduct was a large and complex water distribution system constructed for New York City between 1837 and 1842. The great aqueducts, which were among the first in the United States, carried water by gravity fr ...

, a National Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark (NHL) is a National Register of Historic Places property types, building, district, object, site, or structure that is officially recognized by the Federal government of the United States, United States government f ...

. The commercial areas of downtown Sleepy Hollow are two blocks to the north along North Broadway.

Topographically the park consists of two slight rises, more pronounced toward the west, reflecting the land's general descent toward the nearby Hudson River

The Hudson River, historically the North River, is a river that flows from north to south largely through eastern New York (state), New York state. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains at Henderson Lake (New York), Henderson Lake in the ...

. They are divided by the narrow channel followed by Andre Brook, which also forms the boundary between the two villages, Tarrytown to the south and Sleepy Hollow to the north. The land is mostly open, with tall mature trees providing shade opportunities, more in the north of the park than the south.

The park's organizing feature is an oval walkway with entrances at the north, east and west, and short paths to a basketball court at the south and North Broadway to the southeast. The main entrance is at the west. It is flanked by two gateposts of rusticated granite blocks. Stone walls in random ashlar

Ashlar () is a cut and dressed rock (geology), stone, worked using a chisel to achieve a specific form, typically rectangular in shape. The term can also refer to a structure built from such stones.

Ashlar is the finest stone masonry unit, a ...

with granite copings begin at the posts and follow the sidewalks to create terraces, broken by granite steps to the walkway, on either side of the entrance. They end in granite consoles.

In the north terraces is a stone gatehouse

A gatehouse is a type of fortified gateway, an entry control point building, enclosing or accompanying a gateway for a town, religious house, castle, manor house, or other fortification building of importance. Gatehouses are typically the most ...

, one bay

A bay is a recessed, coastal body of water that directly connects to a larger main body of water, such as an ocean, a lake, or another bay. A large bay is usually called a ''gulf'', ''sea'', ''sound'', or ''bight''. A ''cove'' is a small, ci ...

on each side with walls laid in a random ashlar

Ashlar () is a cut and dressed rock (geology), stone, worked using a chisel to achieve a specific form, typically rectangular in shape. The term can also refer to a structure built from such stones.

Ashlar is the finest stone masonry unit, a ...

pattern and topped by a cornice

In architecture, a cornice (from the Italian ''cornice'' meaning "ledge") is generally any horizontal decorative Moulding (decorative), moulding that crowns a building or furniture element—for example, the cornice over a door or window, ar ...

line. Atop is a hipped roof

A hip roof, hip-roof or hipped roof, is a type of roof where all sides slope downward to the walls, usually with a fairly gentle slope, with variants including tented roofs and others. Thus, a hipped roof has no gables or other vertical sides ...

shingled in asphalt, with exposed rafter

A rafter is one of a series of sloped structural members such as Beam (structure), steel beams that extend from the ridge or hip to the wall plate, downslope perimeter or eave, and that are designed to support the roof Roof shingle, shingles, ...

ends. Its entrance is on the west facade; the only window is on the north.

South of the west entrance is the Captors' Monument, enclosed by a square iron fence. It consists of two pedestal

A pedestal or plinth is a support at the bottom of a statue, vase, column, or certain altars. Smaller pedestals, especially if round in shape, may be called socles. In civil engineering, it is also called ''basement''. The minimum height o ...

s topped by a bronze statue of John Paulding

John Paulding (October 16, 1758 – February 18, 1818) was an American militiaman from the New York State, state of New York during the American Revolution. In 1780, he was one of three men who captured Major John André, a British spy associate ...

, one of the local men who apprehended André. The older lower pedestal is a square block of white Sing Sing

Sing Sing Correctional Facility is a maximum-security prison for men operated by the New York State Department of Corrections and Community Supervision in the village of Ossining (village), New York, Ossining, New York, United States. It is abou ...

marble

Marble is a metamorphic rock consisting of carbonate minerals (most commonly calcite (CaCO3) or Dolomite (mineral), dolomite (CaMg(CO3)2) that have recrystallized under the influence of heat and pressure. It has a crystalline texture, and is ty ...

with a recessed panel on the west side. Inside the panel is a bronze commemorative plaque

A commemorative plaque, or simply plaque, or in other places referred to as a historical marker, historic marker, or historic plaque, is a plate of metal, ceramic, stone, wood, or other material, bearing text or an image in relief, or both, ...

with a bas-relief

Relief is a sculptural method in which the sculpted pieces remain attached to a solid background of the same material. The term ''relief'' is from the Latin verb , to raise (). To create a sculpture in relief is to give the impression that th ...

depicting André's capture. It supports the upper pedestal, a narrowing concrete block, and the statue of Paulding atop that. South of the Captors' Monument is a more modern statue of Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus (; between 25 August and 31 October 1451 – 20 May 1506) was an Italians, Italian explorer and navigator from the Republic of Genoa who completed Voyages of Christopher Columbus, four Spanish-based voyages across the At ...

.

Opposite the entrance curving stone steps, along with a sloped walkway from the south, lead down from battered stone piers at either end of a

Opposite the entrance curving stone steps, along with a sloped walkway from the south, lead down from battered stone piers at either end of a retaining wall

Retaining walls are relatively rigid walls used for supporting soil laterally so that it can be retained at different levels on the two sides. Retaining walls are structures designed to restrain soil to a slope that it would not naturally keep to ...

to a basin where Andre Brook flows out from a culvert

A culvert is a structure that channels water past an obstacle or to a subterranean waterway. Typically embedded so as to be surrounded by soil, a culvert may be made from a pipe (fluid conveyance), pipe, reinforced concrete or other materia ...

that has carried it under North Broadway and the schools to the east. It emerges from an arch with alternating scaled voussoir

A voussoir ( UK: ; US: ) is a wedge-shaped element, typically a stone, which is used in building an arch or vault.“Voussoir, N., Pronunciation.” Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford UP, June 2024, https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/7553486115. Acces ...

s and a scaled keystone in the monochrome ashlar retaining wall on the west side of the walkway. Above it is a balcony supported by two consoles.

The brook flows over a dam and west down a concrete-lined channel, paralleled by a stone path on the south bank. Midway along it is a small stone foot bridge, with battered stone piers and an arch, with the same voussoirs as the retaining wall arch but a shouldered keystone. From there it flows over another waterfall and under the drive bridge, similar to the foot bridge but heavier, then into another culvert under North Washington Avenue.

There are two playgrounds within the park. A smaller, older one is in the northwest corner, and a newer and larger one in the southwest, near the library. Decorative lamps line the drive, and benches are located around the park.

History

The park derives its primary importance from the capture of Major André during the war. The monument was erected in the mid-19th century. After being developed for residential use in the late 19th century, it became home to two girls' schools and finally, today's park, undergoing several renovations in the process.1780: Capture of Major André

In 1780, five years from the start of the Revolutionary War, the settlements that would later become the Tarrytowns were in the middle of Neutral Ground, the –wide no man's land between British forces occupying New York City (at the time, what is todayLower Manhattan

Lower Manhattan, also known as Downtown Manhattan or Downtown New York City, is the southernmost part of the Boroughs of New York City, New York City borough of Manhattan. The neighborhood is History of New York City, the historical birthplace o ...

) and the Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies representing the Thirteen Colonies and later the United States during the American Revolutionary War. It was formed on June 14, 1775, by a resolution passed by the Second Continental Co ...

north of the Croton River

The Croton River ( ) is a river in southern New York with a watershed area of , and three principal tributaries: the West Branch, Middle Branch, and East Branch. Their waters, all part of the New York City water supply system, join downstr ...

. Gangs of armed bandits roamed the lightly populated area, raiding farms in a search for livestock and other goods they could sell to the warring armies. Those with Loyalist

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cr ...

sympathies were called Cow-boys; their counterparts who sold to the Patriots

A patriot is a person with the quality of patriotism.

Patriot(s) or The Patriot(s) may also refer to:

Political and military groups United States

* Patriot (American Revolution), those who supported the cause of independence in the American R ...

were known as Skinners.

On the morning of September 24 that year, three young men—John Paulding

John Paulding (October 16, 1758 – February 18, 1818) was an American militiaman from the New York State, state of New York during the American Revolution. In 1780, he was one of three men who captured Major John André, a British spy associate ...

, Isaac Van Wart

Isaac Van Wart (October 25, 1762May 23, 1828) was a militiaman from the state of New York during the American Revolution. In 1780, he was one of three men who captured British Major John André, who was convicted and executed as a spy for conspir ...

and David Williams—set themselves up along the road through Tarrytown, approximately east of where the Captors' Monument is now. They were part of a group of eight Skinners, hoping to ambush a party of Cow-boys. A rider approached them, and they raised their guns to stop him. It was Major John André

Major John André (May 2, 1750 – October 2, 1780) was a British Army officer who served as the head of Britain's intelligence operations during the American War for Independence. In September 1780, he negotiated with Continental Army offic ...

of the British Army, returning from a clandestine visit to West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), commonly known as West Point, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York that educates cadets for service as Officer_(armed_forces)#United_States, comm ...

, where he had been negotiating the terms of a surrender with General Benedict Arnold

Benedict Arnold (#Brandt, Brandt (1994), p. 4June 14, 1801) was an American-born British military officer who served during the American Revolutionary War. He fought with distinction for the American Continental Army and rose to the rank of ...

of the Continental Army.

Paulding, who had recently escaped from British custody, wore a Hessian coat he had taken in the process, which led André to assume, in the ensuing conversation, that the three were Cow-boys who could thus aid him in continuing on to New York. When informed of his mistake, he produced a pass signed by Arnold. The three searched him and found papers in his boots, not only his correspondence with Arnold but diagrams of the defenses at West Point. Paulding, the only literate member of the trio, read them and realized quickly that André was a spy. Williams asked André what money he could pay them, but Paulding quickly ended any talk of a payoff, swearing that not even 10,000

Paulding, who had recently escaped from British custody, wore a Hessian coat he had taken in the process, which led André to assume, in the ensuing conversation, that the three were Cow-boys who could thus aid him in continuing on to New York. When informed of his mistake, he produced a pass signed by Arnold. The three searched him and found papers in his boots, not only his correspondence with Arnold but diagrams of the defenses at West Point. Paulding, the only literate member of the trio, read them and realized quickly that André was a spy. Williams asked André what money he could pay them, but Paulding quickly ended any talk of a payoff, swearing that not even 10,000 guineas

The guinea (; commonly abbreviated gn., or gns. in plural) was a coin, minted in Great Britain between 1663 and 1814, that contained approximately one-quarter of an ounce of gold. The name came from the Guinea region in West Africa, from where m ...

would be enough.

After André was turned over to the Continental command at North Castle, he was taken across the Hudson to Tappan where he was held prisoner in The '76 House

The '76 House, also known as the ''Old '76 House'', is a Colonial-era structure built as a home and tavern in Tappan, New York, in 1754 by Casparus Mabie, a merchant and tavern-keeper.

History Origin

In spite of local claims of much earlier co ...

tavern. After being convicted of espionage at a military trial in the Reformed Church Of Tappan (today a National Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark (NHL) is a National Register of Historic Places property types, building, district, object, site, or structure that is officially recognized by the Federal government of the United States, United States government f ...

), he was hanged by order of George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

, who had attended the trial. Had André successfully conveyed the information Arnold had given him to New York, the British could have managed to secure the Hudson and cut New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

off from the other rebellious colonies, resolving the stalemate of the time in their favor and drastically changing the outcome of the war.

Arnold, tipped off about André's arrest by a member of his staff unaware of his commander's involvement, was able to escape to the British with his family. After holding some commands in the British Army, he emigrated to England at war's end, where he was buried two decades later. Paulding, Van Wart and Williams were recognized and compensated for their roles in the capture. The Continental Congress

The Continental Congress was a series of legislature, legislative bodies, with some executive function, for the Thirteen Colonies of British America, Great Britain in North America, and the newly declared United States before, during, and after ...

awarded them lifetime pensions and the Fidelity Medallion

The Fidelity Medallion is the oldest decoration of the United States military and was created by act of the Continental Congress in 1780.

Also known as the "André Capture Medal", the Fidelity Medallion was awarded to those soldiers who partic ...

, generally considered the first U.S. military decoration; the state gave them farms confiscated from Loyalists. Two decades later, three counties in the new state of Ohio were named after them. Later the elementary school near the memorial would take Paulding's name as well.

1853–1942: homes and schools

David Williams, the sole survivor of the trio that captured Major John Andre, died in 1831. After his death, a movement began to build a monument at the capture site. It never gained enough support, but never completely disappeared either. In 1852 the Monument Association to the Captors of Major André was formally established at last, and it was able to bring those plans to fruition. A local freedAfrican American

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from an ...

couple, William and Mary Taylor, donated the property they owned at the intersection of the brook and the highway. The cornerstone

A cornerstone (or foundation stone or setting stone) is the first stone set in the construction of a masonry Foundation (engineering), foundation. All other stones will be set in reference to this stone, thus determining the position of the entir ...

was laid on Independence Day

An independence day is an annual event memorialization, commemorating the anniversary of a nation's independence or Sovereign state, statehood, usually after ceasing to be a group or part of another nation or state, or after the end of a milit ...

, July 4, 1853. Among those at the ceremony were Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the first U.S. secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795 dur ...

's son James

James may refer to:

People

* James (given name)

* James (surname)

* James (musician), aka Faruq Mahfuz Anam James, (born 1964), Bollywood musician

* James, brother of Jesus

* King James (disambiguation), various kings named James

* Prince Ja ...

, and Horatio Seymour

Horatio Seymour (May 31, 1810February 12, 1886) was an American politician. He served as the eighteenth Governor of New York from 1853 to 1854 and again from 1863 to 1864. He was the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Pa ...

and Henry J. Raymond, governor and lieutenant governor of New York, respectively. The lower pedestal was raised shortly thereafter, of marble quarried in nearby Sing Sing, today Ossining. It was topped with an obelisk

An obelisk (; , diminutive of (') ' spit, nail, pointed pillar') is a tall, slender, tapered monument with four sides and a pyramidal or pyramidion top. Originally constructed by Ancient Egyptians and called ''tekhenu'', the Greeks used th ...

.

On the centennial of the capture in 1880, the monument was expanded and rededicated. A crowd of 70,000 attended the ceremony, presided over by Samuel J. Tilden (one of his last public appearances) and

On the centennial of the capture in 1880, the monument was expanded and rededicated. A crowd of 70,000 attended the ceremony, presided over by Samuel J. Tilden (one of his last public appearances) and Chauncey Depew

Chauncey Mitchell Depew (April 23, 1834April 5, 1928) was an American attorney, businessman, and Republican politician. He is best remembered for his two terms as United States Senator from New York and for his work for Cornelius Vanderbilt, a ...

. The obelisk was replaced with the current concrete block and topped with a statue of Paulding by William R. O'Donovan, donated by a Tarrytown resident.

At that time there were three houses across North Broadway, dating to at least 1865. They were demolished to clear the way for an 1892 plan to incorporate the monument into Brookside Park, a new residential development. Carrère and Hastings

Carrère and Hastings, the firm of John Merven Carrère ( ; November 9, 1858 – March 1, 1911) and Thomas Hastings (architect), Thomas Hastings (March 11, 1860 – October 22, 1929), was an American list of architecture firms, architecture firm ...

designed eight wood and stone Beaux-Arts cottages and a stone gatehouse, meant to blend in with the site, and laid out the park's extant landscaping, its symmetry and grandiose treatment of the basin characteristic of their chosen style. By the end of the year all were completed, at a cost of $10,000 ($ in modern dollars) apiece. Developer Eugene Jones intended to lease the units individually rather than sell them.

In 1896 he sold them to Amos Clark, who continued to lease out the cottages until renting the property to the recently established Knox School for Girls in 1911. It named the buildings, which housed its 42 students, after roses. By the end of the decade Knox had outgrown Brookside, and moved to a new campus in Cooperstown

Cooperstown is a village in and the county seat of Otsego County, New York, United States. Most of the village lies within the town of Otsego, but some of the eastern part is in the town of Middlefield. Located at the foot of Otsego Lake in ...

. In 1920 another girls' school, Highland Manor, moved in.

Among the students to attend Highland Manor was Lauren Bacall

Betty Joan Perske (September 16, 1924 – August 12, 2014), professionally known as Lauren Bacall ( ), was an American actress. She was named the AFI's 100 Years...100 Stars, 20th-greatest female star of classic Hollywood cinema by the America ...

, later a successful actress. In 1942, as its predecessor had, the school moved to a larger campus elsewhere. Two local women bought the park, had all but one of the neglected cottages demolished, and then donated the property to the two villages. At that time it was renamed to Patriot's Park.

1943–present: park

AfterWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

ended, three local garden clubs formed a committee to guide the restoration of the park. Following a plan by a still-unidentified architect, the foundations

Foundation(s) or The Foundation(s) may refer to: Common uses

* Foundation (cosmetics), a skin-coloured makeup cream applied to the face

* Foundation (engineering), the element of a structure which connects it to the ground, and transfers loads f ...

of the demolished houses were filled in and planted in 1949. Over the next six years further improvements were made. New paved paths were created, dead trees replaced with younger dogwood

''Cornus'' is a genus of about 30–60 species of woody plants in the family Cornaceae, commonly known as dogwoods or cornels, which can generally be distinguished by their blossoms, berries, and distinctive bark. Most are deciduous ...

s and the brook channel lined with concrete. All the masonry was reset and repointed.

The remaining house from Brookside Park was used as a gymnasium and storage area until it was demolished around 1970. The gatehouse is the only building left from that development. As of 1982 the villages of Tarrytown and North Tarrytown (as Sleepy Hollow was known until changing its name in the early 1990s) both allocated a thousand dollars a year to the park's maintenance.

See also

*National Register of Historic Places listings in northern Westchester County, New York

__NOTOC__

This is a list of the National Register of Historic Places listings in northern Westchester County, New York, excluding the city of Peekskill, which has its own list.

This is intended to be a complete list of the properties and distric ...

References

External links

* {{New York in the American Revolutionary War Parks in Westchester County, New York American Revolutionary War sites Parks on the National Register of Historic Places in New York (state) Beaux-Arts architecture in New York (state) New York (state) in the American Revolution U.S. Route 9 1853 establishments in New York (state) Sleepy Hollow, New York Tarrytown, New York National Register of Historic Places in Westchester County, New York American Revolution on the National Register of Historic Places