Pantheon, London on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Pantheon was a place of public entertainment on the south side of

The Pantheon was promoted by Philip Elias Turst, of whose life very little else is known. In 1769 he inherited a plot of land which had a frontage of on Oxford Street and contained two houses, behind which there was a large piece of ground enclosed by the gardens of houses in

The Pantheon was promoted by Philip Elias Turst, of whose life very little else is known. In 1769 he inherited a plot of land which had a frontage of on Oxford Street and contained two houses, behind which there was a large piece of ground enclosed by the gardens of houses in  Turst soon found himself in legal conflict, not only with Miss Ellice, but also with some of his new investors, as the budget was exceeded, but in January 1772 the Pantheon was completed. The architect chosen for the job was

Turst soon found himself in legal conflict, not only with Miss Ellice, but also with some of his new investors, as the budget was exceeded, but in January 1772 the Pantheon was completed. The architect chosen for the job was

The main part of the site consisted of two rectangles of land. The smaller of these was towards Oxford Street. There, the main doorway, sheltered by a

The main part of the site consisted of two rectangles of land. The smaller of these was towards Oxford Street. There, the main doorway, sheltered by a

By 1795 the structure had been rebuilt in a similar but not identical form and it was leased as a place of assembly by one Crispus Claggett, who intended to provide masquerades and concerts. The principal room of this reincarnation was not a rotunda but consisted of "an Area or Pit, … and a double tier of elegant and spacious Boxes, in the centre of which is a most splendid one for the Royal Family". The Pantheon reopened with a masquerade on 9 April 1795. The revived assembly rooms were a failure, and in 1796 or 1797 Claggett disappeared and was never heard of again.

By 1795 the structure had been rebuilt in a similar but not identical form and it was leased as a place of assembly by one Crispus Claggett, who intended to provide masquerades and concerts. The principal room of this reincarnation was not a rotunda but consisted of "an Area or Pit, … and a double tier of elegant and spacious Boxes, in the centre of which is a most splendid one for the Royal Family". The Pantheon reopened with a masquerade on 9 April 1795. The revived assembly rooms were a failure, and in 1796 or 1797 Claggett disappeared and was never heard of again.

From 1798 to 1810 the shareholders reverted to the original custom of managing the Pantheon themselves but the popularity of the entertainments continued to decline. In 1811–12

From 1798 to 1810 the shareholders reverted to the original custom of managing the Pantheon themselves but the popularity of the entertainments continued to decline. In 1811–12

Survey of London

— detailed architectural history {{coord, 51.5155, -0.1381, type:landmark_region:GB-WSM, display=title Assembly rooms Dance venues in England Demolished buildings and structures in London Former buildings and structures in the City of Westminster Entertainment in London Rotundas in the United Kingdom Domes in the United Kingdom 1772 establishments in England 1937 disestablishments in England Buildings and structures completed in 1772 Buildings and structures demolished in 1937 James Wyatt buildings Georgian architecture in the City of Westminster Neoclassical architecture in London Oxford Street

Oxford Street

Oxford Street is a major road in the City of Westminster in the West End of London, running between Marble Arch and Tottenham Court Road via Oxford Circus. It marks the notional boundary between the areas of Fitzrovia and Marylebone to t ...

, London, England. It was designed by James Wyatt

James Wyatt (3 August 1746 – 4 September 1813) was an English architect, a rival of Robert Adam in the Neoclassicism, neoclassical and neo-Gothic styles. He was elected to the Royal Academy of Arts in 1785 and was its president from 1805 to ...

and opened in 1772. The main rotunda

A rotunda () is any roofed building with a circular ground plan, and sometimes covered by a dome. It may also refer to a round room within a building (an example being the one below the dome of the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C.). ...

was one of the largest rooms built in England up to that time and had a central dome

A dome () is an architectural element similar to the hollow upper half of a sphere. There is significant overlap with the term cupola, which may also refer to a dome or a structure on top of a dome. The precise definition of a dome has been a m ...

somewhat reminiscent of the celebrated Pantheon in Rome. It was built as a set of winter assembly rooms

In Great Britain and Ireland, especially in the 18th and 19th centuries, assembly rooms were gathering places for members of the higher social classes open to members of both sexes. At that time most entertaining was done at home and there wer ...

and later briefly converted into a theatre. Before being demolished in 1937, it was a bazaar and a wine merchant's show room for over a hundred years. Marks and Spencer

Marks and Spencer plc (commonly abbreviated to M&S and colloquially known as Marks & Sparks or simply Marks) is a major British multinational retailer based in London, England, that specialises in selling clothing, beauty products, home produc ...

's "Oxford Street Pantheon" branch, at 173 Oxford Street now occupies the site.

Construction

The Pantheon was promoted by Philip Elias Turst, of whose life very little else is known. In 1769 he inherited a plot of land which had a frontage of on Oxford Street and contained two houses, behind which there was a large piece of ground enclosed by the gardens of houses in

The Pantheon was promoted by Philip Elias Turst, of whose life very little else is known. In 1769 he inherited a plot of land which had a frontage of on Oxford Street and contained two houses, behind which there was a large piece of ground enclosed by the gardens of houses in Great Marlborough Street

Great Marlborough Street is a thoroughfare in Soho, Central London. It runs east of Regent Street past Carnaby Street towards Noel Street.

Originally part of the Millfield estate south of Tyburn Road (now Oxford Street), the street was named ...

, Poland Street and Oxford Street. He had some connections with fashionable society, including a lady of means named Margaretta Maria Ellice, who was involved in the management of a fashionable set of assembly rooms in Soho Square

Soho Square is a garden square in Soho, London, hosting since 1954 a ''de facto'' public park leasehold estate, let by the Soho Square Garden Committee to Westminster City Council. It was originally called King Square after Charles II of Engla ...

. Miss Ellice was briefly Turst's main financial backer, and took soundings to ensure that a new place of public entertainment on an ambitious scale for the winter season

A season is a division of the year based on changes in weather, ecology, and the number of daylight hours in a given region. On Earth, seasons are the result of the axial parallelism of Earth's axial tilt, tilted orbit around the Sun. In temperat ...

similar to Ranelagh Gardens

Ranelagh Gardens (; alternative spellings include Ranelegh and Ranleigh, the latter reflecting the English pronunciation) were public pleasure gardens located in Chelsea, then just outside London, England, in the 18th century.

History

The R ...

for the summer, would be "likely to meet with the Approbation of the Nobility in General". This assurance being forthcoming the scheme went ahead.

After falling out with Miss Ellice, who had initially agreed to buy thirty of the fifty shares in the business for £10,000, but soon withdrew, Turst issued fifty shares at £500 each and found buyers for all of them except one, which he kept for himself. This provided a budget of £25,000 and work began in mid-1769.

Turst soon found himself in legal conflict, not only with Miss Ellice, but also with some of his new investors, as the budget was exceeded, but in January 1772 the Pantheon was completed. The architect chosen for the job was

Turst soon found himself in legal conflict, not only with Miss Ellice, but also with some of his new investors, as the budget was exceeded, but in January 1772 the Pantheon was completed. The architect chosen for the job was James Wyatt

James Wyatt (3 August 1746 – 4 September 1813) was an English architect, a rival of Robert Adam in the Neoclassicism, neoclassical and neo-Gothic styles. He was elected to the Royal Academy of Arts in 1785 and was its president from 1805 to ...

. He was to become one of the most prominent British architects of his generation, but at that time he was unknown and aged just twenty-two or twenty-three. He appears to have had some sort of indirect connection with Turst, perhaps through his older brother Samuel

Samuel is a figure who, in the narratives of the Hebrew Bible, plays a key role in the transition from the biblical judges to the United Kingdom of Israel under Saul, and again in the monarchy's transition from Saul to David. He is venera ...

, who was to be the main contractor for the project.

The artists and craftsmen involved included the plasterer Joseph Rose, the sculptor Joseph Nollekens

Joseph Nollekens R.A. (11 August 1737 – 23 April 1823) was a sculptor from London generally considered to be the finest British sculptor of the late 18th century.

Life

Nollekens was born on 11 August 1737 at 28 Dean Street, Soho, London, ...

, who was paid £160 for four statues of Britannia, Liberty, the King and the Queen, and John Stretzle, who built the organ for £300.

In August 1769, Turst purchased a leasehold

A leasehold estate is an ownership of a temporary right to hold land or property in which a Lease, lessee or a tenant has rights of real property by some form of title (property), title from a lessor or landlord. Although a tenant does hold right ...

house on the west side of Poland Street which backed on to the site of the Pantheon and built a secondary entrance there. This unbudgeted cost added more fuel to the legal fire. In 1771 one of the shareholders filed a bill of complaint against Turst in the Court of Chancery

The Court of Chancery was a court of equity in England and Wales that followed a set of loose rules to avoid a slow pace of change and possible harshness (or "inequity") of the Common law#History, common law. The Chancery had jurisdiction over ...

, complaining of dishonest treatment. In 1773 and again in 1782 Turst in his turn filed complaints against several other shareholders. The outcome of these suits is not known.

The building

The main part of the site consisted of two rectangles of land. The smaller of these was towards Oxford Street. There, the main doorway, sheltered by a

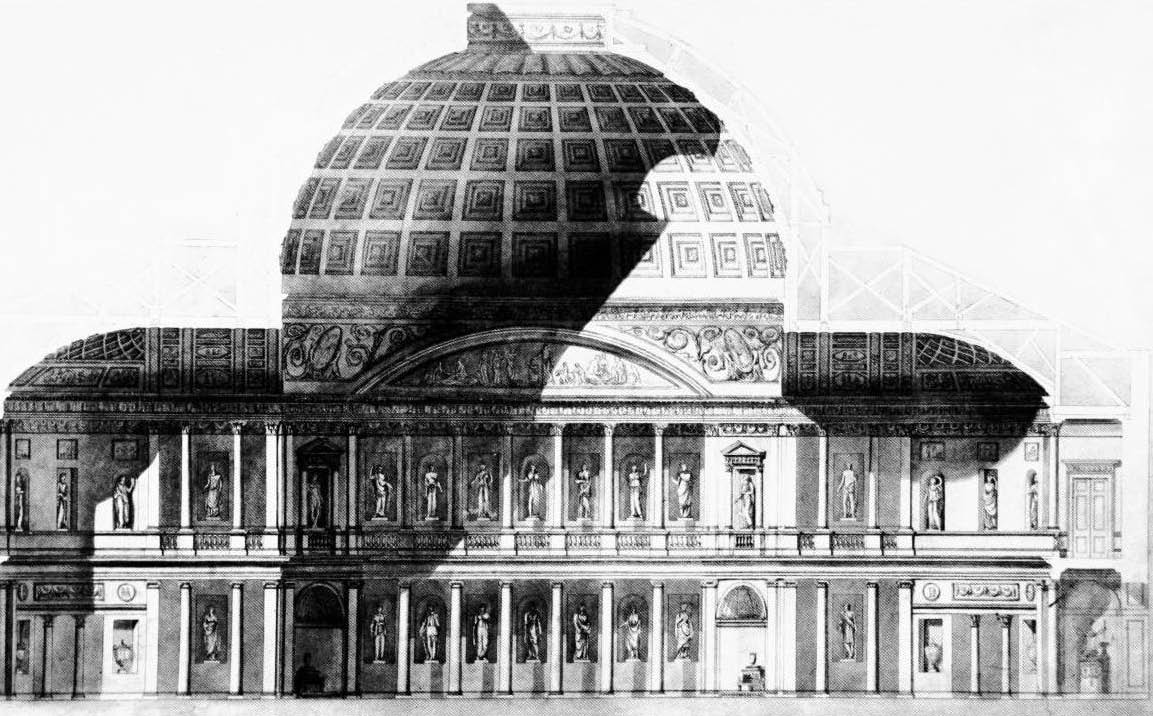

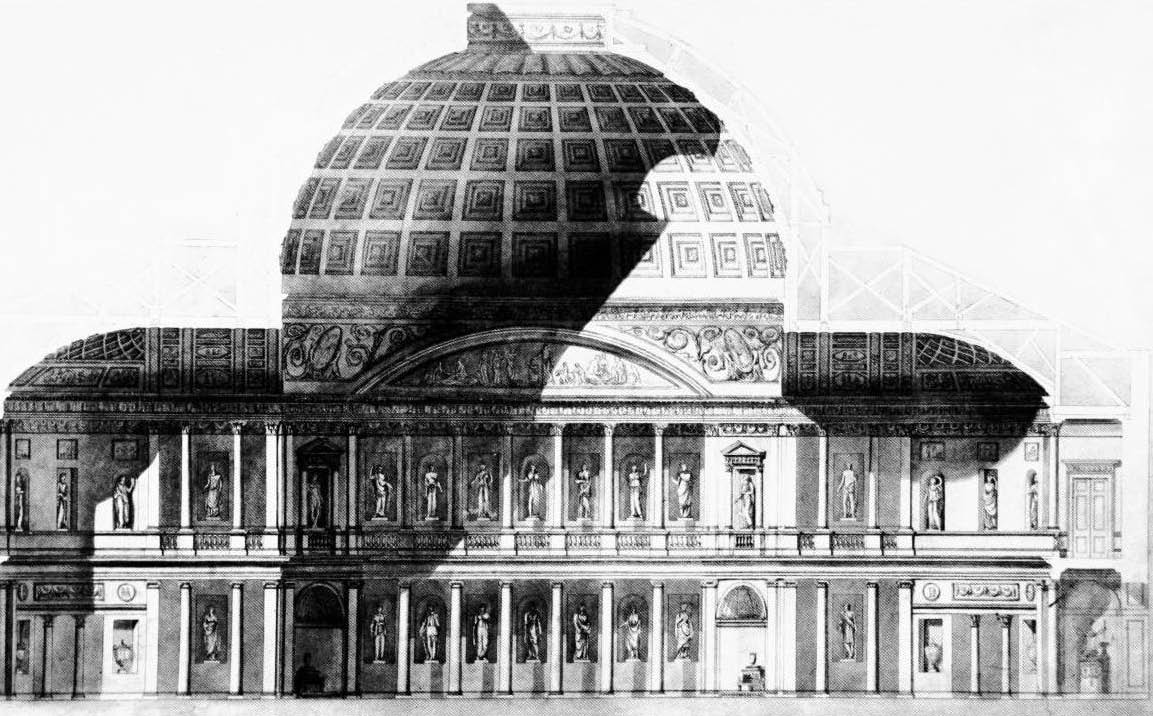

The main part of the site consisted of two rectangles of land. The smaller of these was towards Oxford Street. There, the main doorway, sheltered by a portico

A portico is a porch leading to the entrance of a building, or extended as a colonnade, with a roof structure over a walkway, supported by columns or enclosed by walls. This idea was widely used in ancient Greece and has influenced many cu ...

, and the two side doorways opened to a vestibule, wide and deep, which was divided by screen colonnades into three compartments. A central set of doors opened into the first of two card rooms, and two further pairs of doors opened onto corridors or galleries, giving access to the grand staircase and the great assembly room or rotunda. The total depth of the site was and the maximum width was .

There is general agreement that the scheme of the great room, or rotunda, was derived from Santa Sophia in Istanbul

Istanbul is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, constituting the country's economic, cultural, and historical heart. With Demographics of Istanbul, a population over , it is home to 18% of the Demographics ...

. The central space was contained in a square of topped by a coffer

A coffer (or coffering) in architecture is a series of sunken panels in the shape of a square, rectangle, or octagon in a ceiling, soffit or vault.

A series of these sunken panels was often used as decoration for a ceiling or a vault, al ...

ed dome

A dome () is an architectural element similar to the hollow upper half of a sphere. There is significant overlap with the term cupola, which may also refer to a dome or a structure on top of a dome. The precise definition of a dome has been a m ...

. On the east and west sides were superimposed colonnade

In classical architecture, a colonnade is a long sequence of columns joined by their entablature, often free-standing, or part of a building. Paired or multiple pairs of columns are normally employed in a colonnade which can be straight or curv ...

s of seven bays, screening the aisles and first floor galleries. At the north and south end there were short arms, wide, terminating in shallow segmental apse

In architecture, an apse (: apses; from Latin , 'arch, vault'; from Ancient Greek , , 'arch'; sometimes written apsis; : apsides) is a semicircular recess covered with a hemispherical Vault (architecture), vault or semi-dome, also known as an ' ...

s. The architectural elements and decorations were strictly Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of Roman civilization

*Epistle to the Romans, shortened to Romans, a letter w ...

in inspiration. Below the rotunda there was a tea and supper room, of the same shape but divided into five aisles by the piers supporting the floor above.

The architecture of the Pantheon was lavishly praised by many of those who saw it. Horace Walpole

Horatio Walpole, 4th Earl of Orford (; 24 September 1717 – 2 March 1797), better known as Horace Walpole, was an English Whig politician, writer, historian and antiquarian.

He had Strawberry Hill House built in Twickenham, southwest London ...

compared Wyatt's work favourably with that of better established and very fashionable Robert Adam

Robert Adam (3 July 17283 March 1792) was a British neoclassical architect, interior designer and furniture designer. He was the son of William Adam (architect), William Adam (1689–1748), Scotland's foremost architect of the time, and train ...

, "the Pantheon is still the most beautiful edifice in England" he said. Dr. Burney, writing long after the destruction of the original building by fire (an event which inflicted on him a heavy financial loss), when the first wave of enthusiasm had long been dissipated, stated that the Pantheon "was built by Mr. James Wyatt, and regarded both by natives and foreigners, as the most elegant structure in Europe, if not on the globe… . No person of taste in architecture or music, who remembers the Pantheon, its exhibitions, its numerous, splendid, and elegant assemblies, can hear it mentioned without a sigh!"

Contemporary reports of the cost of the building were greatly exaggerated. Writing to Sir Horace Mann

Horace Mann (May 4, 1796August 2, 1859) was an American educational reformer, slavery abolitionist and Whig Party (United States), Whig politician known for his commitment to promoting public education, he is thus also known as ''The Father of A ...

in May 1770 Horace Walpole asked "What do you think of a winter Ranelagh erecting in Oxford Road, at the expense of sixty thousand pounds?". The courts later determined that the actual cost was £36,965 19s. 5½d: £27,407 2s. 11½d for the main construction work, £2,500 for the entrance from Poland Street and £7,058 16s. 6d for furniture, paintings, statues, the organ, and Wyatt's five per cent commission as architect.

History

The Pantheon opened on Monday, 27 January 1772. Up to fifty pounds was paid for tickets for the first night which attracted over seventeen hundred members of high society including all the foreign ambassadors and eight dukes and duchesses. Initially the social tone was very high (though a policy that patrons should only be admitted on the recommendation of a peeress was soon dropped), and good profits were made. During the first winter there were assemblies only, without dancing or music, three times a week. In subsequent seasons the entertainments included a mixture of assemblies, masquerades (masked balls) and subscription concerts. For a while the shares commanded high prices and James Wyatt claimed to have sold his two shares for £900 each. In the 1780s the popularity of the Pantheon declined; however, one of the commemoration concerts celebrating the music of the German composer, Handel, was held in the Pantheon in 1784. After the destruction of the King's Theatre inThe Haymarket

Haymarket is a street in the St James's area of the City of Westminster, London. It runs from Piccadilly Circus in the north to Pall Mall at the southern end. Located on the street are the Theatre Royal, His Majesty's Theatre, New Zealand H ...

by fire in 1789, it was converted into an opera house on a twelve-year lease at £3,000 per annum. James Wyatt was once again the architect. After only one complete season of opera the Pantheon was burnt to the ground in 1792. Tate Britain

Tate Britain, known from 1897 to 1932 as the National Gallery of British Art and from 1932 to 2000 as the Tate Gallery, is an art museum on Millbank in the City of Westminster in London, England. It is part of the Tate network of galleries in En ...

holds a watercolour entitled ''The Pantheon, the Morning after the Fire'', which is attributed (although not without dispute) to the 16-year-old J. M. W. Turner

Joseph Mallord William Turner (23 April 177519 December 1851), known in his time as William Turner, was an English Romantic painter, printmaker and watercolourist. He is known for his expressive colouring, imaginative landscapes and turbu ...

.

By 1795 the structure had been rebuilt in a similar but not identical form and it was leased as a place of assembly by one Crispus Claggett, who intended to provide masquerades and concerts. The principal room of this reincarnation was not a rotunda but consisted of "an Area or Pit, … and a double tier of elegant and spacious Boxes, in the centre of which is a most splendid one for the Royal Family". The Pantheon reopened with a masquerade on 9 April 1795. The revived assembly rooms were a failure, and in 1796 or 1797 Claggett disappeared and was never heard of again.

By 1795 the structure had been rebuilt in a similar but not identical form and it was leased as a place of assembly by one Crispus Claggett, who intended to provide masquerades and concerts. The principal room of this reincarnation was not a rotunda but consisted of "an Area or Pit, … and a double tier of elegant and spacious Boxes, in the centre of which is a most splendid one for the Royal Family". The Pantheon reopened with a masquerade on 9 April 1795. The revived assembly rooms were a failure, and in 1796 or 1797 Claggett disappeared and was never heard of again.

From 1798 to 1810 the shareholders reverted to the original custom of managing the Pantheon themselves but the popularity of the entertainments continued to decline. In 1811–12

From 1798 to 1810 the shareholders reverted to the original custom of managing the Pantheon themselves but the popularity of the entertainments continued to decline. In 1811–12 Nicholas Wilcox Cundy

Nicholas Wilcox Cundy (1778 – c. 1837) was an English architect and engineer. He was the son of Peter Cundy and Thomasine Wilcox and the brother of Thomas Cundy (senior). His parents' address was Restowick House, St Dennis, Cornwall.

Career

N ...

converted the building into a theatre, but restrictions imposed by the Lord Chamberlain

The Lord Chamberlain of the Household is the most senior officer of the Royal Households of the United Kingdom, Royal Household of the United Kingdom, supervising the departments which support and provide advice to the Monarchy of the United Ki ...

(then the regulator and censor of theatres) ruined this venture and the career of the Pantheon as a place of public entertainment came to a close in 1814.

In 1833–34, the Pantheon was rebuilt as a bazaar

A bazaar or souk is a marketplace consisting of multiple small Market stall, stalls or shops, especially in the Middle East, the Balkans, Central Asia, North Africa and South Asia. They are traditionally located in vaulted or covered streets th ...

by the architect Sydney Smirke

Sydney Smirke (20 December 1797 – 8 December 1877) was a British architect.

Smirke who was born in London, England as the fifth son of painter Robert Smirke and his wife, Elizabeth Russell. He was the younger brother of Sir Robert Smirke ...

. The whole of the roof and part of the walls of the old building were taken down, but the entrance fronts to both Oxford Street and Poland Street were retained, as were also the rooms immediately behind the former. The main space of the new building was a great hall of basilica

In Ancient Roman architecture, a basilica (Greek Basiliké) was a large public building with multiple functions that was typically built alongside the town's forum. The basilica was in the Latin West equivalent to a stoa in the Greek Eas ...

n plan, with a barrel-vault

A barrel vault, also known as a tunnel vault, wagon vault or wagonhead vault, is an architectural element formed by the extrusion of a single curve (or pair of curves, in the case of a pointed barrel vault) along a given distance. The curves are ...

ed nave

The nave () is the central part of a church, stretching from the (normally western) main entrance or rear wall, to the transepts, or in a church without transepts, to the chancel. When a church contains side aisles, as in a basilica-type ...

of five wide bays. In 1867, the building was acquired by W. and A. Gilbey, wine merchant

A winemaker or vintner is a person engaged in winemaking. They are generally employed by winery, wineries or :Wine companies, wine companies, where their work includes:

*Cooperating with viticulture, viticulturists

*Monitoring the maturity of grap ...

s, and was used by them as offices and show rooms until 1937.

It was demolished shortly afterwards to make way for a branch of Marks and Spencer

Marks and Spencer plc (commonly abbreviated to M&S and colloquially known as Marks & Sparks or simply Marks) is a major British multinational retailer based in London, England, that specialises in selling clothing, beauty products, home produc ...

, the Georgian Group unsuccessfully attempting to preserve the façade elsewhere. The Marks and Spencer building opened in 1938, and is still there. This was designed by Robert Lutyens (son of Sir Edwin Lutyens

Sir Edwin Landseer Lutyens ( ; 29 March 1869 – 1 January 1944) was an English architect known for imaginatively adapting traditional architectural styles to the requirements of his era. He designed many English country houses, war memorials ...

). It has a gleaming art deco polished black granite façade and has become a distinctive landmark on Oxford Street. Its special historic and architectural interest was recognised on 21 September 2009 when the Minister of Culture, Barbara Follett, awarded the building Grade II listed

In the United Kingdom, a listed building is a structure of particular architectural or historic interest deserving of special protection. Such buildings are placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, H ...

status.

See also

*List of demolished buildings and structures in London

This list of demolished buildings and structures in London includes buildings, structures and urban scenes of particular architectural and historical interest, scenic buildings which are preserved in old photographs, prints and paintings, but whic ...

References

External links

Survey of London

— detailed architectural history {{coord, 51.5155, -0.1381, type:landmark_region:GB-WSM, display=title Assembly rooms Dance venues in England Demolished buildings and structures in London Former buildings and structures in the City of Westminster Entertainment in London Rotundas in the United Kingdom Domes in the United Kingdom 1772 establishments in England 1937 disestablishments in England Buildings and structures completed in 1772 Buildings and structures demolished in 1937 James Wyatt buildings Georgian architecture in the City of Westminster Neoclassical architecture in London Oxford Street