In

philosophy of mind

Philosophy of mind is a branch of philosophy that deals with the nature of the mind and its relation to the Body (biology), body and the Reality, external world.

The mind–body problem is a paradigmatic issue in philosophy of mind, although a ...

, panpsychism () is the view that the

mind

The mind is that which thinks, feels, perceives, imagines, remembers, and wills. It covers the totality of mental phenomena, including both conscious processes, through which an individual is aware of external and internal circumstances ...

or a mind-like aspect is a fundamental and ubiquitous feature of reality.

It is also described as a theory that "the mind is a fundamental feature of the world which exists throughout the universe".

It is one of the oldest philosophical theories, and has been ascribed in some form to philosophers including

Thales

Thales of Miletus ( ; ; ) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek Pre-Socratic philosophy, pre-Socratic Philosophy, philosopher from Miletus in Ionia, Asia Minor. Thales was one of the Seven Sages of Greece, Seven Sages, founding figure ...

,

Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

,

Spinoza

Baruch (de) Spinoza (24 November 163221 February 1677), also known under his Latinized pen name Benedictus de Spinoza, was a philosopher of Portuguese-Jewish origin, who was born in the Dutch Republic. A forerunner of the Age of Enlightenmen ...

,

Leibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (or Leibnitz; – 14 November 1716) was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat who is credited, alongside Sir Isaac Newton, with the creation of calculus in addition to many ...

,

Schopenhauer,

William James

William James (January 11, 1842 – August 26, 1910) was an American philosopher and psychologist. The first educator to offer a psychology course in the United States, he is considered to be one of the leading thinkers of the late 19th c ...

,

Alfred North Whitehead

Alfred North Whitehead (15 February 1861 – 30 December 1947) was an English mathematician and philosopher. He created the philosophical school known as process philosophy, which has been applied in a wide variety of disciplines, inclu ...

, and

Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, and public intellectual. He had influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, and various areas of analytic ...

.

In the 19th century, panpsychism was the default philosophy of mind in Western thought, but it saw a decline in the mid-20th century with the rise of

logical positivism

Logical positivism, also known as logical empiricism or neo-positivism, was a philosophical movement, in the empiricist tradition, that sought to formulate a scientific philosophy in which philosophical discourse would be, in the perception of ...

.

Recent interest in the

hard problem of consciousness

In the philosophy of mind, the hard problem of consciousness is to explain why and how humans and other organisms have qualia, phenomenal consciousness, or subjective experience. It is contrasted with the "easy problems" of explaining why and how ...

and developments in the fields of

neuroscience

Neuroscience is the scientific study of the nervous system (the brain, spinal cord, and peripheral nervous system), its functions, and its disorders. It is a multidisciplinary science that combines physiology, anatomy, molecular biology, ...

,

psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. Its subject matter includes the behavior of humans and nonhumans, both consciousness, conscious and Unconscious mind, unconscious phenomena, and mental processes such as thoughts, feel ...

, and

quantum mechanics

Quantum mechanics is the fundamental physical Scientific theory, theory that describes the behavior of matter and of light; its unusual characteristics typically occur at and below the scale of atoms. Reprinted, Addison-Wesley, 1989, It is ...

have revived interest in panpsychism in the 21st century because it addresses the hard problem directly.

Overview

Etymology

The term ''panpsychism'' comes from the

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

''pan'' (

πᾶν: "all, everything, whole") and ''psyche'' (

ψυχή: "

soul

The soul is the purported Mind–body dualism, immaterial aspect or essence of a Outline of life forms, living being. It is typically believed to be Immortality, immortal and to exist apart from the material world. The three main theories that ...

,

mind

The mind is that which thinks, feels, perceives, imagines, remembers, and wills. It covers the totality of mental phenomena, including both conscious processes, through which an individual is aware of external and internal circumstances ...

").

The use of "psyche" is controversial because it is synonymous with "soul", a term usually taken to refer to something supernatural; more common terms now found in the literature include

mind

The mind is that which thinks, feels, perceives, imagines, remembers, and wills. It covers the totality of mental phenomena, including both conscious processes, through which an individual is aware of external and internal circumstances ...

,

mental properties, mental aspect, and

experience

Experience refers to Consciousness, conscious events in general, more specifically to perceptions, or to the practical knowledge and familiarity that is produced by these processes. Understood as a conscious event in the widest sense, experience i ...

.

Concept

Panpsychism holds that mind or a mind-like aspect is a fundamental and ubiquitous feature of reality.

It is sometimes defined as a theory in which "the mind is a fundamental feature of the world which exists throughout the universe".

Panpsychists posit that the type of mentality we know through our own experience is present, in some form, in a wide range of natural bodies.

This notion has taken on a wide variety of forms. Some historical and non-Western panpsychists ascribe attributes such as life or spirits to all entities (

animism

Animism (from meaning 'breath, spirit, life') is the belief that objects, places, and creatures all possess a distinct spiritual essence. Animism perceives all things—animals, plants, rocks, rivers, weather systems, human handiwork, and in ...

).

Contemporary academic proponents, however, hold that

sentience

Sentience is the ability to experience feelings and sensations. It may not necessarily imply higher cognitive functions such as awareness, reasoning, or complex thought processes. Some writers define sentience exclusively as the capacity for ''v ...

or

subjective experience

In philosophy of mind, qualia (; singular: quale ) are defined as instances of Subjectivity, subjective, consciousness, conscious experience. The term ''qualia'' derives from the Latin neuter plural form (''qualia'') of the Latin adjective '':wi ...

is ubiquitous, while distinguishing these qualities from more complex human mental attributes.

They therefore ascribe a primitive form of mentality to entities at the fundamental level of physics but may not ascribe mentality to most aggregate things, such as rocks or buildings.

Terminology

The philosopher

David Chalmers

David John Chalmers (; born 20 April 1966) is an Australian philosopher and cognitive scientist, specializing in philosophy of mind and philosophy of language. He is a professor of philosophy and neural science at New York University, as well ...

, who has explored panpsychism as a viable theory, distinguishes between microphenomenal experiences (the experiences of

microphysical entities) and macrophenomenal experiences (the experiences of larger entities, such as humans).

draws a distinction between ''panexperientialism'' and ''pancognitivism''. In the form of panpsychism under discussion in the contemporary literature, conscious experience is present everywhere at a fundamental level, hence the term ''panexperientialism''. Pancognitivism, by contrast, is the view that thought is present everywhere at a fundamental level—a view that had some historical advocates, but no present-day academic adherents. Contemporary panpsychists do not believe microphysical entities have complex mental states such as beliefs, desires, and fears.

Originally, the term ''panexperientialism'' had a narrower meaning, having been coined by

David Ray Griffin

David Ray Griffin (August 8, 1939 – November 2022) was an American professor of philosophy of religion and theology and a 9/11 conspiracy theorist.Sources describing David Ray Griffin as a "conspiracy theorist", "conspiracist", "conspiracy nut ...

to refer specifically to the form of panpsychism used in

process philosophy

Process philosophy (also ontology of becoming or processism) is an approach in philosophy that identifies processes, changes, or shifting relationships as the only real experience of everyday living. In opposition to the classical view of change ...

(see below).

History

Antiquity

Panpsychist views are a staple in

pre-Socratic

Pre-Socratic philosophy, also known as early Greek philosophy, is ancient Greek philosophy before Socrates. Pre-Socratic philosophers were mostly interested in cosmology, the beginning and the substance of the universe, but the inquiries of the ...

Greek philosophy

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BC. Philosophy was used to make sense of the world using reason. It dealt with a wide variety of subjects, including astronomy, epistemology, mathematics, political philosophy, ethics, metaphysic ...

.

According to

Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

,

Thales

Thales of Miletus ( ; ; ) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek Pre-Socratic philosophy, pre-Socratic Philosophy, philosopher from Miletus in Ionia, Asia Minor. Thales was one of the Seven Sages of Greece, Seven Sages, founding figure ...

(c. 624 – 545 BCE), the first Greek philosopher, posited a theory which held "that everything is full of gods". Thales believed that magnets demonstrated this. This has been interpreted as a panpsychist doctrine.

Other Greek thinkers associated with panpsychism include

Anaxagoras

Anaxagoras (; , ''Anaxagóras'', 'lord of the assembly'; ) was a Pre-Socratic Greek philosopher. Born in Clazomenae at a time when Asia Minor was under the control of the Persian Empire, Anaxagoras came to Athens. In later life he was charged ...

(who saw the unifying principle or ''

arche

In philosophy and science, a first principle is a basic proposition or assumption that cannot be deduced from any other proposition or assumption. First principles in philosophy are from first cause attitudes and taught by Aristotelians, and nuan ...

'' as ''

nous

''Nous'' (, ), from , is a concept from classical philosophy, sometimes equated to intellect or intelligence, for the cognitive skill, faculty of the human mind necessary for understanding what is truth, true or reality, real.

Alternative Eng ...

'' or mind),

Anaximenes (who saw the ''arche'' as ''

pneuma

''Pneuma'' () is an ancient Greek word for "breathing, breath", and in a religious context for "spirit (animating force), spirit". It has various technical meanings for medical writers and philosophers of classical antiquity, particularly in rega ...

'' or spirit) and

Heraclitus

Heraclitus (; ; ) was an Ancient Greece, ancient Greek Pre-Socratic philosophy, pre-Socratic philosopher from the city of Ephesus, which was then part of the Achaemenid Empire, Persian Empire. He exerts a wide influence on Western philosophy, ...

(who said "The thinking faculty is common to all").

Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

argues for panpsychism in his ''

Sophist

A sophist () was a teacher in ancient Greece in the fifth and fourth centuries BCE. Sophists specialized in one or more subject areas, such as philosophy, rhetoric, music, athletics and mathematics. They taught ''arete'', "virtue" or "excellen ...

'', in which he writes that all things participate in the

form of Being and that it must have a psychic aspect of mind and soul (''

psyche'').

In the ''

Philebus'' and ''

Timaeus'', Plato argues for the idea of a world soul or ''anima mundi''. According to Plato:

This world is indeed a living being endowed with a soul and intelligence ... a single visible living entity containing all other living entities, which by their nature are all related.

Stoicism

Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy that flourished in ancient Greece and Rome. The Stoics believed that the universe operated according to reason, ''i.e.'' by a God which is immersed in nature itself. Of all the schools of ancient ...

developed a cosmology that held that the natural world is infused with the divine fiery essence ''

pneuma

''Pneuma'' () is an ancient Greek word for "breathing, breath", and in a religious context for "spirit (animating force), spirit". It has various technical meanings for medical writers and philosophers of classical antiquity, particularly in rega ...

'', directed by the universal intelligence ''

logos

''Logos'' (, ; ) is a term used in Western philosophy, psychology and rhetoric, as well as religion (notably Logos (Christianity), Christianity); among its connotations is that of a rationality, rational form of discourse that relies on inducti ...

''. The relationship between beings' individual ''logos'' and the universal ''logos'' was a central concern of the Roman Stoic

Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus ( ; ; 26 April 121 – 17 March 180) was Roman emperor from 161 to 180 and a Stoicism, Stoic philosopher. He was a member of the Nerva–Antonine dynasty, the last of the rulers later known as the Five Good Emperors ...

. The

metaphysics of Stoicism finds connections with

Hellenistic philosophies such as

Neoplatonism

Neoplatonism is a version of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a series of thinkers. Among the common id ...

.

Gnosticism

Gnosticism (from Ancient Greek language, Ancient Greek: , Romanization of Ancient Greek, romanized: ''gnōstikós'', Koine Greek: Help:IPA/Greek, �nostiˈkos 'having knowledge') is a collection of religious ideas and systems that coalesced ...

also made use of the Platonic idea of ''anima mundi''.

Renaissance

After Emperor Justinian closed

Plato's Academy

The Academy (), variously known as Plato's Academy, or the Platonic Academy, was founded in Athens by Plato ''circa'' 387 BC. The academy is regarded as the first institution of higher education in the west, where subjects as diverse as biolog ...

in 529 CE,

neoplatonism

Neoplatonism is a version of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a series of thinkers. Among the common id ...

declined. Though there were mediaeval theologians, such as

John Scotus Eriugena, who ventured into what might be called panpsychism, it was not a dominant strain in philosophical theology. But in the

Italian Renaissance

The Italian Renaissance ( ) was a period in History of Italy, Italian history between the 14th and 16th centuries. The period is known for the initial development of the broader Renaissance culture that spread across Western Europe and marked t ...

, it enjoyed something of a revival in the thought of figures such as

Gerolamo Cardano

Gerolamo Cardano (; also Girolamo or Geronimo; ; ; 24 September 1501– 21 September 1576) was an Italian polymath whose interests and proficiencies ranged through those of mathematician, physician, biologist, physicist, chemist, astrologer, as ...

,

Bernardino Telesio,

Francesco Patrizi,

Giordano Bruno

Giordano Bruno ( , ; ; born Filippo Bruno; January or February 1548 – 17 February 1600) was an Italian philosopher, poet, alchemist, astrologer, cosmological theorist, and esotericist. He is known for his cosmological theories, which concep ...

, and

Tommaso Campanella

Tommaso Campanella (; 5 September 1568 – 21 May 1639), baptized Giovanni Domenico Campanella, was an Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, theologian, astrologer, and poet.

Campanella was prosecuted by the Roman Inquisition for he ...

. Cardano argued for the view that soul or ''anima'' was a fundamental part of the world, and Patrizi introduced the term ''panpsychism'' into philosophical vocabulary. According to Bruno, "There is nothing that does not possess a soul and that has no vital principle".

Platonist ideas resembling the ''anima mundi'' (world soul) also resurfaced in the work of

esoteric

Western esotericism, also known as the Western mystery tradition, is a wide range of loosely related ideas and movements that developed within Western society. These ideas and currents are united since they are largely distinct both from orthod ...

thinkers such as

Paracelsus

Paracelsus (; ; 1493 – 24 September 1541), born Theophrastus von Hohenheim (full name Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim), was a Swiss physician, alchemist, lay theologian, and philosopher of the German Renaissance.

H ...

,

Robert Fludd

Robert Fludd, also known as Robertus de Fluctibus (17 January 1574 – 8 September 1637), was a prominent English Paracelsian physician with both scientific and occult interests. He is remembered as an astrologer, mathematician, cosmol ...

, and

Cornelius Agrippa.

Early modern

In the 17th century, two

rationalists

In philosophy, rationalism is the epistemological view that "regards reason as the chief source and test of knowledge" or "the position that reason has precedence over other ways of acquiring knowledge", often in contrast to other possible s ...

,

Baruch Spinoza

Baruch (de) Spinoza (24 November 163221 February 1677), also known under his Latinized pen name Benedictus de Spinoza, was a philosopher of Portuguese-Jewish origin, who was born in the Dutch Republic. A forerunner of the Age of Enlightenmen ...

and

Gottfried Leibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (or Leibnitz; – 14 November 1716) was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat who is credited, alongside Isaac Newton, Sir Isaac Newton, with the creation of calculus in ad ...

, can be said to be panpsychists.

In Spinoza's monism, the one single infinite and eternal substance is "God, or Nature" (''

Deus sive Natura''), which has the aspects of mind (thought) and matter (extension). Leibniz's view is that there are infinitely many absolutely simple mental substances called

monads that make up the universe's fundamental structure. While it has been said that

George Berkeley

George Berkeley ( ; 12 March 168514 January 1753), known as Bishop Berkeley (Bishop of Cloyne of the Anglican Church of Ireland), was an Anglo-Irish philosopher, writer, and clergyman who is regarded as the founder of "immaterialism", a philos ...

's

idealist

Idealism in philosophy, also known as philosophical realism or metaphysical idealism, is the set of metaphysical perspectives asserting that, most fundamentally, reality is equivalent to mind, spirit, or consciousness; that reality is entir ...

philosophy is also a form of panpsychism,

Berkeley rejected panpsychism and posited that the physical world exists only in the experiences minds have of it, while restricting minds to humans and certain other specific agents.

[Berkeley, George (1948–57, Nelson) Robinson, H. (ed.) (1996). "Principles of Human Knowledge and Three Dialogues", pp. ix–x & passim. Oxford University Press, Oxford. .]

19th century

In the 19th century, panpsychism was at its zenith. Philosophers such as

Arthur Schopenhauer

Arthur Schopenhauer ( ; ; 22 February 1788 – 21 September 1860) was a German philosopher. He is known for his 1818 work ''The World as Will and Representation'' (expanded in 1844), which characterizes the Phenomenon, phenomenal world as ...

,

C.S. Peirce,

Josiah Royce

Josiah Royce (; November 20, 1855 – September 14, 1916) was an American Pragmatism, pragmatist and objective idealism, objective idealist philosopher and the founder of American idealism. His philosophical ideas included his joining of pragmatis ...

,

William James

William James (January 11, 1842 – August 26, 1910) was an American philosopher and psychologist. The first educator to offer a psychology course in the United States, he is considered to be one of the leading thinkers of the late 19th c ...

,

Eduard von Hartmann,

F.C.S. Schiller

Ferdinand Canning Scott Schiller, Fellow of the British Academy, FBA (; 16 August 1864 – 6 August 1937), usually cited as F. C. S. Schiller, was a German-British philosopher. Born in Altona, Hamburg, Altona, Duchy of Holstein, Holstein (at tha ...

,

Ernst Haeckel

Ernst Heinrich Philipp August Haeckel (; ; 16 February 1834 – 9 August 1919) was a German zoologist, natural history, naturalist, eugenics, eugenicist, Philosophy, philosopher, physician, professor, marine biology, marine biologist and artist ...

,

William Kingdon Clifford

William Kingdon Clifford (4 May 18453 March 1879) was a British mathematician and philosopher. Building on the work of Hermann Grassmann, he introduced what is now termed geometric algebra, a special case of the Clifford algebra named in his ...

and

Thomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian, and philosopher. Known as the "Sage writing, sage of Chelsea, London, Chelsea", his writings strongly influenced the intellectual and artistic culture of the V ...

as well as psychologists such as

Gustav Fechner

Gustav Theodor Fechner (; ; 19 April 1801 – 18 November 1887) was a German physicist, philosopher, and experimental psychologist. A pioneer in experimental psychology and founder of psychophysics (techniques for measuring the mind), he inspi ...

,

Wilhelm Wundt

Wilhelm Maximilian Wundt (; ; 16 August 1832 – 31 August 1920) was a German physiologist, philosopher, and professor, one of the fathers of modern psychology. Wundt, who distinguished psychology as a science from philosophy and biology, was t ...

,

Rudolf Hermann Lotze all promoted panpsychist ideas.

Arthur Schopenhauer argued for a two-sided view of reality as both

Will

Will may refer to:

Common meanings

* Will and testament, instructions for the disposition of one's property after death

* Will (philosophy), or willpower

* Will (sociology)

* Will, volition (psychology)

* Will, a modal verb - see Shall and will

...

and Representation (''Vorstellung''). According to Schopenhauer, "All ostensible mind can be attributed to matter, but all matter can likewise be attributed to mind".

Josiah Royce

Josiah Royce (; November 20, 1855 – September 14, 1916) was an American Pragmatism, pragmatist and objective idealism, objective idealist philosopher and the founder of American idealism. His philosophical ideas included his joining of pragmatis ...

, the leading American absolute idealist, held that reality is a "world self", a conscious being that comprises everything, though he did not necessarily attribute mental properties to the smallest constituents of mentalistic "systems". The American

pragmatist philosopher

Charles Sanders Peirce

Charles Sanders Peirce ( ; September 10, 1839 – April 19, 1914) was an American scientist, mathematician, logician, and philosopher who is sometimes known as "the father of pragmatism". According to philosopher Paul Weiss (philosopher), Paul ...

espoused a sort of psycho-physical

monism

Monism attributes oneness or singleness () to a concept, such as to existence. Various kinds of monism can be distinguished:

* Priority monism states that all existing things go back to a source that is distinct from them; e.g., in Neoplatonis ...

in which the universe is suffused with mind, which he associated with spontaneity and freedom. Following Pierce,

William James

William James (January 11, 1842 – August 26, 1910) was an American philosopher and psychologist. The first educator to offer a psychology course in the United States, he is considered to be one of the leading thinkers of the late 19th c ...

also espoused a form of panpsychism. In his lecture notes, James wrote:

Our only intelligible notion of an object ''in itself'' is that it should be an object ''for itself'', and this lands us in panpsychism and a belief that our physical perceptions are effects on us of 'psychical' realities

English philosopher

Alfred Barratt, the author of ''Physical Metempiric'' (1883), has been described as advocating panpsychism.

In 1893,

Paul Carus

Paul Carus (; 18 July 1852 – 11 February 1919) was a German-American author, editor, a student of comparative religion proposed a philosophy similar to panpsychism, "panbiotism", according to which "everything is fraught with life; it contains life; it has the ability to live".

[Skrbina, David. (2005). ''Panpsychism in the West''. MIT Press. .]

20th century

Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, and public intellectual. He had influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, and various areas of analytic ...

's

neutral monist views tended toward panpsychism.

The physicist

Arthur Eddington also defended a form of panpsychism.

The psychologists

Gerard Heymans,

James Ward and

Charles Augustus Strong also endorsed variants of panpsychism.

In 1990, the physicist

David Bohm

David Joseph Bohm (; 20 December 1917 – 27 October 1992) was an American scientist who has been described as one of the most significant Theoretical physics, theoretical physicists of the 20th centuryDavid Peat Who's Afraid of Schrödinger' ...

published "A new theory of the relationship of mind and matter," a paper based on his

interpretation of quantum mechanics.

The philosopher

Paavo Pylkkänen has described Bohm's view as a version of panprotopsychism.

One widespread misconception is that the arguably greatest systematic metaphysician of the 20th century,

Alfred North Whitehead

Alfred North Whitehead (15 February 1861 – 30 December 1947) was an English mathematician and philosopher. He created the philosophical school known as process philosophy, which has been applied in a wide variety of disciplines, inclu ...

, was also panpsychism's most significant 20th century proponent.

This misreading attributes to Whitehead an

ontology

Ontology is the philosophical study of existence, being. It is traditionally understood as the subdiscipline of metaphysics focused on the most general features of reality. As one of the most fundamental concepts, being encompasses all of realit ...

according to which the basic nature of the world is made up of

atom

Atoms are the basic particles of the chemical elements. An atom consists of a atomic nucleus, nucleus of protons and generally neutrons, surrounded by an electromagnetically bound swarm of electrons. The chemical elements are distinguished fr ...

ic mental events, termed "actual occasions".

But rather than signifying such exotic metaphysical objects—which would in fact exemplify the

fallacy of misplaced concreteness Whitehead criticizes—Whitehead's concept of "actual occasion" refers to the "immediate experienced occasion" of any possible perceiver, having in mind only himself as perceiver at the outset, in accordance with his strong commitment to

radical empiricism

Radical empiricism is a philosophical doctrine put forth by William James. It asserts that experience includes both particulars and relations between those particulars, and that therefore both deserve a place in our explanations. In concrete term ...

.

Contemporary

Panpsychism has recently seen a resurgence in the

philosophy of mind

Philosophy of mind is a branch of philosophy that deals with the nature of the mind and its relation to the Body (biology), body and the Reality, external world.

The mind–body problem is a paradigmatic issue in philosophy of mind, although a ...

, set into motion by

Thomas Nagel's 1979 article "Panpsychism" and further spurred by

Galen Strawson's 2006

realistic monist article "Realistic Monism: Why Physicalism Entails Panpsychism".

[ Strawson, Galen (2006). "Realistic Monism: Why Physicalism Entails Panpsychism". '' Journal of Consciousness Studies''. Volume 13, No 10–11, Exeter, Imprint Academic pp. 3–31.] Other recent proponents include American philosophers

David Ray Griffin

David Ray Griffin (August 8, 1939 – November 2022) was an American professor of philosophy of religion and theology and a 9/11 conspiracy theorist.Sources describing David Ray Griffin as a "conspiracy theorist", "conspiracist", "conspiracy nut ...

and David Skrbina,

British philosophers Gregg Rosenberg,

,

and

Philip Goff,

and Canadian philosopher

William Seager.

The British philosopher

David Papineau, while distancing himself from orthodox panpsychists, has written that his view is "not unlike panpsychism" in that he rejects a line in nature between "events lit up by phenomenology

ndthose that are mere darkness".

The

integrated information theory of consciousness (IIT), proposed by the neuroscientist and psychiatrist

Giulio Tononi in 2004 and since adopted by other neuroscientists such as

Christof Koch, postulates that consciousness is widespread and can be found even in some simple systems.

In 2019,

cognitive scientist

Cognitive science is the interdisciplinary, scientific study of the mind and its processes. It examines the nature, the tasks, and the functions of cognition (in a broad sense). Mental faculties of concern to cognitive scientists include percep ...

Donald Hoffman published ''The Case Against Reality: How evolution hid the truth from our eyes.'' Hoffman argues that

consensus reality

Consensus reality refers to the generally agreed-upon version of reality within a community or society, shaped by shared experiences and understandings. This understanding arises from the inherent differences in individual perspectives or subjec ...

lacks concrete existence, and is nothing more than an evolved

user-interface

In the industrial design field of human–computer interaction, a user interface (UI) is the space where interactions between humans and machines occur. The goal of this interaction is to allow effective operation and control of the machine fro ...

. He argues that the true nature of reality is abstract "conscious agents".

Science editor

Annaka Harris argues that panpsychism is a viable theory in her 2019 book ''Conscious'', though she stops short of fully endorsing it.

Panpsychism has been postulated by psychoanalyst

Robin S. Brown as a means to theorizing relations between "inner" and "outer" tropes in the context of psychotherapy. Panpsychism has also been applied in environmental philosophy by Australian philosopher

Freya Mathews, who has put forward the notion of

ontopoetics as a version of panpsychism.

The geneticist

Sewall Wright

Sewall Green Wright ForMemRS

HonFRSE (December 21, 1889March 3, 1988) was an American geneticist known for his influential work on evolutionary theory and also for his work on path analysis. He was a founder of population genetics alongside ...

endorsed a version of panpsychism. He believed that consciousness is not a mysterious property emerging at a certain level of the hierarchy of increasing material complexity, but rather an inherent property, implying the most elementary particles have these properties.

Varieties

Panpsychism encompasses many theories, united only by the notion that mind in some form is ubiquitous.

Philosophical frameworks

Cosmopsychism

Cosmopsychism hypothesizes that the cosmos is a

unified object that is ontologically prior to its parts. It has been described as an alternative to panpsychism,

[.] or as a form of panpsychism.

Proponents of cosmopsychism claim that the cosmos as a whole is the fundamental level of reality and that it instantiates consciousness. They differ on that point from panpsychists, who usually claim that the smallest level of reality is fundamental and instantiates consciousness. Accordingly, human consciousness, for example, merely derives from a larger cosmic consciousness.

Panexperientialism

Panexperientialism is associated with the philosophies of, among others,

Charles Hartshorne and

Alfred North Whitehead

Alfred North Whitehead (15 February 1861 – 30 December 1947) was an English mathematician and philosopher. He created the philosophical school known as process philosophy, which has been applied in a wide variety of disciplines, inclu ...

, although the term itself was invented by

David Ray Griffin

David Ray Griffin (August 8, 1939 – November 2022) was an American professor of philosophy of religion and theology and a 9/11 conspiracy theorist.Sources describing David Ray Griffin as a "conspiracy theorist", "conspiracist", "conspiracy nut ...

to distinguish the

process philosophical view from other varieties of panpsychism.

Whitehead's

process philosophy

Process philosophy (also ontology of becoming or processism) is an approach in philosophy that identifies processes, changes, or shifting relationships as the only real experience of everyday living. In opposition to the classical view of change ...

argues that the fundamental elements of the universe are "occasions of experience", which can together create something as complex as a human being.

Building on Whitehead's work, process philosopher

Michel Weber argues for a pancreativism. Goff has used the term ''panexperientialism'' more generally to refer to forms of panpsychism in which experience rather than thought is ubiquitous.

Panprotopsychism

Panprotopsychists believe that higher-order phenomenal properties (such as

qualia

In philosophy of mind, qualia (; singular: quale ) are defined as instances of subjective, conscious experience. The term ''qualia'' derives from the Latin neuter plural form (''qualia'') of the Latin adjective '' quālis'' () meaning "of what ...

) are

logically entailed by protophenomenal properties, at least in principle. This is similar to how facts about H

2O molecules logically entail facts about water: the lower-level facts are sufficient to explain the higher-order facts, since the former logically entail the latter. It also makes sense of questions about the unity of consciousness relating to the diversity of phenomenal experiences and the deflation of the self. Adherents of panprotopsychism believe that "protophenomenal" facts logically entail consciousness. Protophenomenal properties are usually picked out through a combination of functional and negative definitions: panphenomenal properties are those that logically entail phenomenal properties (a functional definition), which are themselves neither physical nor phenomenal (a negative definition).

Panprotopsychism is advertised as a solution to the

combination problem: the problem of explaining how the consciousness of microscopic physical things might combine to give rise to the macroscopic consciousness of the whole brain. Because protophenomenal properties are by definition the constituent parts of consciousness, it is speculated that their existence would make the emergence of macroscopic minds less mysterious.

The philosopher

David Chalmers

David John Chalmers (; born 20 April 1966) is an Australian philosopher and cognitive scientist, specializing in philosophy of mind and philosophy of language. He is a professor of philosophy and neural science at New York University, as well ...

argues that the view faces difficulty with the combination problem. He considers it "ad hoc", and believes it diminishes the parsimony that made the theory initially interesting.

David Chalmers

David John Chalmers (; born 20 April 1966) is an Australian philosopher and cognitive scientist, specializing in philosophy of mind and philosophy of language. He is a professor of philosophy and neural science at New York University, as well ...

(1996) '' The Conscious Mind: In Search of a Fundamental Theory'', pp. 153–156. Oxford University Press, New York, .

Russellian monism

Russellian monism is a type of

neutral monism

Neutral monism is an umbrella term for a class of metaphysical theories in the philosophy of mind, concerning the relation of mind to matter. These theories take the fundamental nature of reality to be neither mental nor physical; in other words i ...

.

The theory is attributed to

Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, and public intellectual. He had influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, and various areas of analytic ...

, and may also be called ''Russell's panpsychism,'' or ''Russell's neutral monism''.

Russell believed that all

causal

Causality is an influence by which one Event (philosophy), event, process, state, or Object (philosophy), object (''a'' ''cause'') contributes to the production of another event, process, state, or object (an ''effect'') where the cause is at l ...

properties are

extrinsic manifestations of identical

intrinsic

In science and engineering, an intrinsic property is a property of a specified subject that exists itself or within the subject. An extrinsic property is not essential or inherent to the subject that is being characterized. For example, mass i ...

properties. Russell called these identical internal properties ''quiddities''. Just as the extrinsic properties of matter can form higher-order structure, so can their corresponding and identical quiddities. Russell believed the conscious mind was one such structure.

[.]

Religious or mystical ontologies

Advaita Vedānta

Advaita Vedānta is a form of

idealism

Idealism in philosophy, also known as philosophical realism or metaphysical idealism, is the set of metaphysics, metaphysical perspectives asserting that, most fundamentally, reality is equivalent to mind, Spirit (vital essence), spirit, or ...

in

Indian philosophy

Indian philosophy consists of philosophical traditions of the Indian subcontinent. The philosophies are often called darśana meaning, "to see" or "looking at." Ānvīkṣikī means “critical inquiry” or “investigation." Unlike darśan ...

which views

consensus reality

Consensus reality refers to the generally agreed-upon version of reality within a community or society, shaped by shared experiences and understandings. This understanding arises from the inherent differences in individual perspectives or subjec ...

as illusory. Anand Vaidya and

Purushottama Bilimoria have argued that it can be considered a form of panpsychism or

cosmopsychism.

Animism and hylozoism

Animism maintains that all things have a soul, and hylozoism maintains that all things are alive.

Both could reasonably be interpreted as panpsychist, but both have fallen out of favour in contemporary academia.

Modern panpsychists have tried to distance themselves from theories of this sort, careful to carve out the distinction between the ubiquity of experience and the ubiquity of mind and cognition.

Panpsychism and metempsychosis

Between 1840 and 1864, the Austrian mystic

Jakob Lorber claimed to have received a 26-volume revelation. Various books of the Lorber Revelations say that specifica, closely resembling Leibniz's

monads, form the most basic, irreducible substance of all physical and metaphysical creation. According to the Lorber Revelations, specifica grow in complexity and intelligence to form ever higher level clusters of intelligence until a fully intelligent human soul is reached. In this scenario panpsychism and

metempsychosis

In philosophy and theology, metempsychosis () is the transmigration of the soul, especially its reincarnation after death. The term is derived from ancient Greek philosophy, and has been recontextualized by modern philosophers such as Arthur Sc ...

are used to overcome the

combination problem.

Buddha-nature

Buddha-nature

In Buddhist philosophy and soteriology, Buddha-nature ( Chinese: , Japanese: , , Sanskrit: ) is the innate potential for all sentient beings to become a Buddha or the fact that all sentient beings already have a pure Buddha-essence within ...

is an important and multifaceted doctrine in

Mahayana Buddhism

Mahāyāna ( ; , , ; ) is a term for a broad group of Buddhist traditions, texts, philosophies, and practices developed in ancient India ( onwards). It is considered one of the three main existing branches of Buddhism, the others being Thera ...

that is related to the capacity to attain

Buddhahood

In Buddhism, Buddha (, which in classic Indo-Aryan languages, Indic languages means "awakened one") is a title for those who are Enlightenment in Buddhism, spiritually awake or enlightened, and have thus attained the Buddhist paths to liberat ...

. In numerous Indian sources, the idea is connected to the mind, especially the Buddhist concept of the

luminous mind. In some Buddhist traditions, the Buddha-nature doctrine may be interpreted as implying a form of panpsychism. Graham Parks argues that most "traditional Chinese, Japanese and Korean philosophy would qualify as panpsychist in nature".

The

Huayan,

Tiantai

Tiantai or T'ien-t'ai () is an East Asian Buddhist school of Mahāyāna Buddhism that developed in 6th-century China. Drawing from earlier Mahāyāna sources such as Madhyamaka, founded by Nāgārjuna, who is traditionally regarded as the f ...

, and

Tendai

, also known as the Tendai Dharma Flower School (天台法華宗, ''Tendai hokke shū,'' sometimes just ''Hokkeshū''), is a Mahāyāna Buddhist tradition with significant esoteric elements that was officially established in Japan in 806 by t ...

schools of Buddhism explicitly attribute Buddha-nature to inanimate objects such as lotus flowers and mountains.

This idea was defended by figures such as the Tiantai patriarch

Zhanran, who spoke of the Buddha-nature of grasses and trees.

Similarly,

Soto Zen master

Dogen argued that "insentient beings expound" the teachings of the Buddha, and wrote about the "mind" (心, ''shin'') of "fences, walls, tiles, and pebbles". The 9th-century

Shingon

is one of the major schools of Buddhism in Japan and one of the few surviving Vajrayana lineages in East Asian Buddhism. It is a form of Japanese Esoteric Buddhism and is sometimes called "Tōmitsu" (東密 lit. "Esoteric uddhismof Tō- ...

figure

Kukai went so far as to argue that natural objects such as rocks and stones are part of the supreme embodiment of the Buddha. According to Parks, Buddha-nature is best described "in western terms" as something "''psychophysical".''

[Parks, Graham. "The awareness of rocks". Skrbina David, ed. ''Mind that Abides''. Chapter 17.]

Scientific theories

Conscious realism

Conscious realism is a theory proposed by

Donald Hoffman, a cognitive scientist specialising in perception. He has written numerous papers on the topic which he summarised in his 2019 book ''The Case Against Reality: How evolution hid the truth from our eyes.''

Conscious realism builds upon Hoffman's former ''User-Interface Theory''. In combination they argue that (1)

consensus reality

Consensus reality refers to the generally agreed-upon version of reality within a community or society, shaped by shared experiences and understandings. This understanding arises from the inherent differences in individual perspectives or subjec ...

and spacetime are illusory, and are merely a "species specific evolved user interface"; (2) Reality is made of a complex, dimensionless, and timeless network of "conscious agents".

The consensus view is that perception is a reconstruction of one's environment. Hoffman views perception as a construction rather than a reconstruction. He argues that perceptual systems are analogous to information channels, and thus subject to

data compression

In information theory, data compression, source coding, or bit-rate reduction is the process of encoding information using fewer bits than the original representation. Any particular compression is either lossy or lossless. Lossless compressi ...

and reconstruction. The set of possible reconstructions for any given data set is quite large. Of that set, the subset that is

homomorphic in relation to the original is minuscule, and does not necessarily—or, seemingly, even often—overlap with the subset that is efficient or easiest to use.

For example, consider a graph, such as a pie chart. A pie chart is easy to understand and use not because it is perfectly homomorphic with the data it represents, but because it is not. If a graph of, for example, the chemical composition of the human body were to look exactly like a human body, then we could not understand it. It is only because the graph abstracts away from the structure of its subject matter that it can be visualized. Alternatively, consider a graphical user interface on a computer. The reason graphical user interfaces are useful is that they abstract away from lower-level computational processes, such as machine code, or the physical state of a circuit-board. In general, it seems that data is most useful to us when it is abstracted from its original structure and repackaged in a way that is easier to understand, even if this comes at the cost of accuracy. Hoffman offers the "fitness beats truth theorem" as mathematical proof that perceptions of reality bear little resemblance to reality's true nature. From this he concludes that our senses do not faithfully represent the external world.

Even if reality is an illusion, Hoffman takes consciousness as an indisputable fact. He represents rudimentary units of consciousness (which he calls "conscious agents") as

Markovian kernels. Though the theory was not initially panpsychist, he reports that he and his colleague Chetan Prakash found the math to be more

parsimonious

In philosophy, Occam's razor (also spelled Ockham's razor or Ocham's razor; ) is the problem-solving principle that recommends searching for explanations constructed with the smallest possible set of elements. It is also known as the principle o ...

if it were. They hypothesize that reality is composed of these conscious agents, who interact to form "larger, more complex" networks.

Integrated information theory

Giulio Tononi first articulated Integrated information theory (IIT) in 2004,

and it has undergone two major revisions since then. Tononi approaches consciousness from a scientific perspective, and has expressed frustration with philosophical theories of consciousness for lacking

predictive power.

Though integral to his theory, he refrains from philosophical terminology such as ''

qualia

In philosophy of mind, qualia (; singular: quale ) are defined as instances of subjective, conscious experience. The term ''qualia'' derives from the Latin neuter plural form (''qualia'') of the Latin adjective '' quālis'' () meaning "of what ...

'' or the ''

unity of consciousness,'' instead opting for mathematically precise alternatives like ''entropy function'' and ''information integration''.

This has allowed Tononi to create a measurement for integrated information, which he calls ''phi'' (Φ). He believes consciousness is nothing but integrated information, so Φ measures consciousness. As it turns out, even basic objects or substances have a nonzero degree of Φ. This would mean that consciousness is ubiquitous, albeit to a minimal degree.

The philosopher Hedda Hassel Mørch's views IIT as similar to

Russellian monism,

while other philosophers, such as Chalmers and

John Searle

John Rogers Searle (; born July 31, 1932) is an American philosopher widely noted for contributions to the philosophy of language, philosophy of mind, and social philosophy. He began teaching at UC Berkeley in 1959 and was Willis S. and Mario ...

, consider it a form of panpsychism.

IIT does not hold that all systems are conscious, leading Tononi and Koch to state that IIT incorporates some elements of panpsychism but not others.

Koch has called IIT a "scientifically refined version" of panpsychism.

In relation to other theories

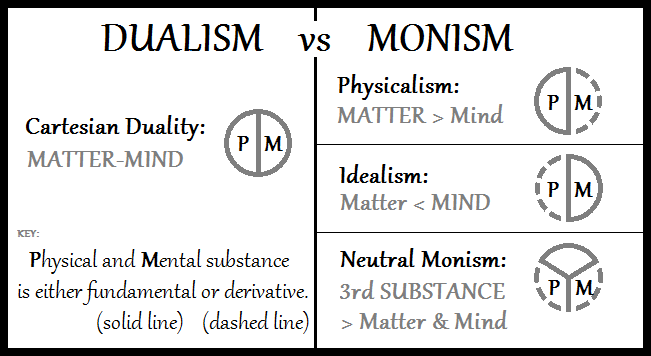

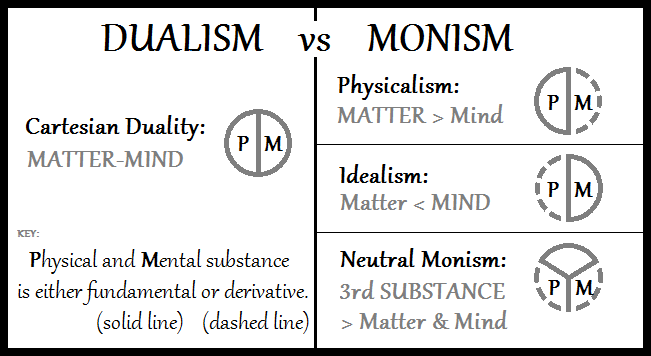

Because panpsychism encompasses a wide range of theories, it can in principle be compatible with

reductive materialism,

dualism,

functionalism, or other perspectives depending on the details of a given formulation.

Dualism

David Chalmers and Philip Goff have each described panpsychism as an alternative to both

materialism

Materialism is a form of monism, philosophical monism according to which matter is the fundamental Substance theory, substance in nature, and all things, including mind, mental states and consciousness, are results of material interactions. Acco ...

and dualism.

Chalmers says panpsychism respects the conclusions of both the causal argument against dualism and the

conceivability argument for dualism.

Goff has argued that panpsychism avoids the disunity of dualism, under which mind and matter are

ontologically separate, as well as dualism's problems explaining how mind and matter interact.

By contrast, Uwe Meixner argues that panpsychism has dualist forms, which he contrasts to

idealist

Idealism in philosophy, also known as philosophical realism or metaphysical idealism, is the set of metaphysical perspectives asserting that, most fundamentally, reality is equivalent to mind, spirit, or consciousness; that reality is entir ...

forms.

Emergentism

Panpsychism is incompatible with emergentism.

In general, theories of consciousness fall under one or the other umbrella; they hold either that consciousness is present at a fundamental level of reality (panpsychism) or that it emerges higher up (emergentism).

Idealism

There is disagreement over whether idealism is a form of panpsychism or a separate view. Both views hold that everything that exists has some form of experience. According to the philosophers William Seager and Sean Allen-Hermanson, "idealists are panpsychists by default".

contrasted panpsychism and idealism, saying that while idealists rejected the existence of the world observed with the senses or understood it as ideas within the mind of God, panpsychists accepted the reality of the world but saw it as composed of minds.

Chalmers also contrasts panpsychism with idealism (as well as

materialism

Materialism is a form of monism, philosophical monism according to which matter is the fundamental Substance theory, substance in nature, and all things, including mind, mental states and consciousness, are results of material interactions. Acco ...

and

dualism).

Meixner writes that formulations of panpsychism can be divided into dualist and idealist versions.

He further divides the latter into "atomistic idealistic panpsychism", which he ascribes to

David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; – 25 August 1776) was a Scottish philosopher, historian, economist, and essayist who was best known for his highly influential system of empiricism, philosophical scepticism and metaphysical naturalism. Beg ...

, and "holistic idealistic panpsychism", which he favors.

Neutral monism

Neutral monism rejects the dichotomy of mind and matter, instead taking a third substance as fundamental that is neither mental nor physical. Proposals for the nature of the third substance have varied, with some theorists choosing to leave it undefined. This has led to a variety of formulations of neutral monism, which may overlap with other philosophies. In versions of neutral monism in which the world's fundamental constituents are neither mental nor physical, it is quite distinct from panpsychism. In versions where the fundamental constituents are both mental and physical, neutral monism may lead to panpsychism, panprotopsychism, or

dual aspect theory.

In ''

The Conscious Mind,'' David Chalmers writes that, in some instances, the differences between "Russell's neutral monism" and his

property dualism

Property dualism describes a category of positions in the philosophy of mind which hold that, although the world is composed of just one kind of Substance theory, substance—Materialism, the physical kind—there exist two distinct kinds of pro ...

are merely semantic.

Philip Goff believes that neutral monism can reasonably be regarded as a form of panpsychism "in so far as it is a dual aspect view".

Neutral monism, panpsychism, and dual aspect theory are grouped together or used interchangeably in some contexts.

Physicalism and materialism

Chalmers calls panpsychism an alternative to both materialism and dualism.

Similarly, Goff calls panpsychism an alternative to both physicalism and

substance dualism.

Strawson, on the other hand, describes panpsychism as a form of physicalism, in his view the only viable form.

Panpsychism can be combined with

reductive materialism but cannot be combined with

eliminative materialism

Eliminative materialism (also called eliminativism) is a materialist position in the philosophy of mind that expresses the idea that the majority of mental states in folk psychology do not exist. Some supporters of eliminativism argue that ...

because the latter denies the existence of the relevant mental attributes.

Arguments for

Hard problem of consciousness

It evidently feels like something to be a human brain. This means that when things in the world are organised in a particular way, they begin to have an experience. The questions of ''why'' and ''how'' this material structure has experience, and why it has ''that'' particular experience rather than another experience, are known as the ''

hard problem of consciousness

In the philosophy of mind, the hard problem of consciousness is to explain why and how humans and other organisms have qualia, phenomenal consciousness, or subjective experience. It is contrasted with the "easy problems" of explaining why and how ...

''.

The term is attributed to Chalmers. He argues that even after "all the perceptual and cognitive functions within the vicinity of consciousness" are accounted for, "there may still remain a further unanswered question: ''Why is the performance of these functions accompanied by experience?"''

Though Chalmers gave the hard problem of consciousness its present name, similar views were expressed before.

Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton () was an English polymath active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author. Newton was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment that followed ...

,

John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.) – 28 October 1704 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.)) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of the Enlightenment thi ...

,

Gottfried Leibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (or Leibnitz; – 14 November 1716) was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat who is credited, alongside Isaac Newton, Sir Isaac Newton, with the creation of calculus in ad ...

,

John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (20 May 1806 – 7 May 1873) was an English philosopher, political economist, politician and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of liberalism and social liberalism, he contributed widely to s ...

,

Thomas Henry Huxley,

Wilhelm Wundt

Wilhelm Maximilian Wundt (; ; 16 August 1832 – 31 August 1920) was a German physiologist, philosopher, and professor, one of the fathers of modern psychology. Wundt, who distinguished psychology as a science from philosophy and biology, was t ...

,

all wrote about the seeming incompatibility of third-person functional descriptions of mind and matter and first-person conscious experience. Likewise, Asian philosophers like

Dharmakirti

Dharmakīrti (fl. ;), was an influential Indian Buddhist philosopher who worked at Nālandā.Tom Tillemans (2011)Dharmakirti Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy He was one of the key scholars of epistemology ( pramāṇa) in Buddhist philo ...

and

Guifeng Zongmi discussed the problem of how consciousness arises from unconscious matter. Similar sentiments have been articulated through philosophical inquiries such as

the problem of other minds,

solipsism

Solipsism ( ; ) is the philosophical idea that only one's mind is sure to exist. As an epistemological position, solipsism holds that knowledge of anything outside one's own mind is unsure; the external world and other minds cannot be known ...

, the

explanatory gap

In the philosophy of mind, the explanatory gap is the difficulty that physicalist philosophies have in explaining how physical properties give rise to the way things feel subjectively when they are experienced. It is a term introduced by philoso ...

,

philosophical zombie

A philosophical zombie (or "p-zombie") is a being in a thought experiment in the philosophy of mind that is physically identical to a normal human being but does not have conscious experience.

For example, if a philosophical zombie were poked ...

s, and

Mary's room. These problems have caused Chalmers to consider panpsychism a viable solution to the hard problem,

David Chalmers

David John Chalmers (; born 20 April 1966) is an Australian philosopher and cognitive scientist, specializing in philosophy of mind and philosophy of language. He is a professor of philosophy and neural science at New York University, as well ...

. '' The Conscious Mind: In Search of a Fundamental Theory''. New York: Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the publishing house of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world. Its first book was printed in Oxford in 1478, with the Press officially granted the legal right to print books ...

, 1996. though he is not committed to any single view.

Brian Jonathan Garrett has compared the hard problem to

vitalism

Vitalism is a belief that starts from the premise that "living organisms are fundamentally different from non-living entities because they contain some non-physical element or are governed by different principles than are inanimate things." Wher ...

, the now discredited hypothesis that life is inexplicable and can only be understood if some vital life force exists. He maintains that given time, consciousness and its evolutionary origins will be understood just as life is now understood. Daniel Dennett called the hard problem a "hunch", and maintained that conscious experience, as it is usually understood, is merely a complex cognitive

illusion

An illusion is a distortion of the senses, which can reveal how the mind normally organizes and interprets sensory stimulation. Although illusions distort the human perception of reality, they are generally shared by most people.

Illusions may ...

.

Patricia Churchland, also an

eliminative materialist, maintains that philosophers ought to be more patient: neuroscience is still in its early stages, so Chalmers's hard problem is premature. Clarity will come from learning more about the brain, not from metaphysical speculation.

Solutions

In ''

The Conscious Mind'' (1996), Chalmers attempts to pinpoint why the hard problem is so hard. He concludes that consciousness is ''

irreducible'' to lower-level physical facts, just as the fundamental laws of physics are irreducible to lower-level physical facts. Therefore, consciousness should be taken as fundamental in its own right and studied as such. Just as fundamental properties of reality are ubiquitous (even small objects have mass), consciousness may also be, though he considers that an open question.

In ''Mortal Questions'' (1979),

Thomas Nagel argues that panpsychism follows from four premises:

* P1: There is no spiritual plane or disembodied soul; everything that exists is

material

A material is a matter, substance or mixture of substances that constitutes an Physical object, object. Materials can be pure or impure, living or non-living matter. Materials can be classified on the basis of their physical property, physical ...

.

* P2: Consciousness is irreducible to lower-level physical properties.

* P3: Consciousness exists.

* P4: Higher-order properties of matter (i.e., emergent properties) can, at least in principle, be reduced to their lower-level properties.

Before the first premise is accepted, the range of possible explanations for consciousness is fully open. Each premise, if accepted, narrows down that range of possibilities. If the argument is

sound

In physics, sound is a vibration that propagates as an acoustic wave through a transmission medium such as a gas, liquid or solid.

In human physiology and psychology, sound is the ''reception'' of such waves and their ''perception'' by the br ...

, then by the last premise panpsychism is the only possibility left.

* If (P1) is true, then either consciousness does not exist, or it exists within the physical world.

* If (P2) is true, then either consciousness does not exist, or it (a) exists as distinct property of matter or (b) is fundamentally entailed by matter.

* If (P3) is true, then consciousness exists, and is either (a) its own property of matter or (b) composed by the matter of the brain but not logically entailed by it.

* If (P4) is true, then (b) is false, and consciousness must be its own unique property of matter.

Therefore, if all four premises are true, consciousness is its own unique property of matter and panpsychism is true.

Mind-body problem

In 2015, Chalmers proposed a possible solution to the mind-body problem through the argumentative format of

thesis, antithesis, and synthesis.

The goal of such arguments is to argue for sides of a debate (the thesis and antithesis), weigh their vices and merits, and then reconcile them (the synthesis). Chalmers's thesis, antithesis, and synthesis are as follows:

# ''Thesis:''

materialism

Materialism is a form of monism, philosophical monism according to which matter is the fundamental Substance theory, substance in nature, and all things, including mind, mental states and consciousness, are results of material interactions. Acco ...

is true; everything is fundamentally physical.

# ''Antithesis:''

dualism is true; not everything is fundamentally physical.

# ''Synthesis:'' panpsychism is true.

(1) A centerpiece of Chalmers's argument is the physical world's

causal closure

Physical causal closure is a metaphysical theory about the nature of causation in the physical realm with significant ramifications in the study of metaphysics and the mind. In a strongly stated version, physical causal closure says that "all phy ...

.

Newton's law of motion explains this phenomenon succinctly: ''for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction''. Cause and effect is a symmetrical process. There is no room for consciousness to exert any causal power on the physical world unless it is itself physical.

(2) On one hand, if consciousness is separate from the physical world then there is no room for it to exert any causal power on the world (a state of affairs philosophers call

epiphenomenalism). If consciousness plays no causal role, then it is unclear how Chalmers could even write this paper. On the other hand, consciousness is irreducible to the physical processes of the brain.

(3) Panpsychism has all the benefits of materialism because it could mean that consciousness is physical while also escaping the grasp of epiphenomenalism. After some argumentation Chalmers narrows it down further to Russellian monism, concluding that thoughts, actions, intentions and emotions may just be the quiddities of neurotransmitters, neurons, and glial cells.

Problem of substance

Rather than solely trying to solve the problem of consciousness, Russell also attempted to solve the ''problem of substance'', which is arguably a form of the ''

problem of infinite regress''.

(1) Like many sciences, physics describes the world through mathematics. Unlike other sciences, physics cannot describe what Schopenhauer called the "object that grounds" mathematics. Economics is grounded in resources being allocated, and population dynamics is grounded in individual people within that population. The objects that ground physics, however, can be described only through more mathematics.

In Russell's words, physics describes "certain equations giving abstract properties of their changes". When it comes to describing "what it is that changes, and what it changes from and to—as to this, physics is silent".

In other words, physics describes matter's ''extrinsic'' properties, but not the ''intrinsic'' properties that ground them.

(2) Russell argued that physics is mathematical because "it is only mathematical properties we can discover". This is true almost by definition: if ''only'' extrinsic properties are outwardly observable, then they will be the only ones discovered.

This led

Alfred North Whitehead

Alfred North Whitehead (15 February 1861 – 30 December 1947) was an English mathematician and philosopher. He created the philosophical school known as process philosophy, which has been applied in a wide variety of disciplines, inclu ...

to conclude that intrinsic properties are "intrinsically unknowable".

(3) Consciousness has many similarities to these intrinsic properties of physics. It, too, cannot be directly observed from an outside perspective. And it, too, seems to ground many observable extrinsic properties: presumably, music is enjoyable because of the experience of listening to it, and chronic pain is avoided because of the experience of pain, etc. Russell concluded that consciousness must be related to these extrinsic properties of matter. He called these intrinsic properties ''quiddities''. Just as extrinsic physical properties can create structures, so can their corresponding and identical quiddites. The conscious mind, Russell argued, is one such structure.

Proponents of panpsychism who use this line of reasoning include Chalmers,

Annaka Harris,

and

Galen Strawson. Chalmers has argued that the extrinsic properties of physics must have corresponding intrinsic properties; otherwise the universe would be "a giant causal flux" with nothing for "causation to relate", which he deems a logical impossibility. He sees consciousness as a promising candidate for that role.

calls Russell's panpsychism "realistic physicalism". He argues that "the experiential considered specifically as such" is what it means for something to be physical. Just as

mass is energy, Strawson believes that consciousness "just is" matter.

Max Tegmark

Max Erik Tegmark (born 5 May 1967) is a Swedish-American physicist, machine learning researcher and author. He is best known for his book ''Life 3.0'' about what the world might look like as artificial intelligence continues to improve. Tegmark i ...

, theoretical physicist and creator of the

mathematical universe hypothesis

In physics and cosmology, the mathematical universe hypothesis (MUH), also known as the ultimate ensemble theory, is a speculative "theory of everything" (TOE) proposed by cosmologist Max Tegmark. According to the hypothesis, the universe ''is'' a ...

, disagrees with these conclusions. By his account, the universe is not just describable by math but ''is'' math; comparing physics to economics or population dynamics is a disanalogy. While population dynamics may be grounded in individual people, those people are grounded in "purely mathematical objects" such as energy and charge. The universe is, in a fundamental sense, made of nothing.

Quantum mechanics

In a 2018 interview, Chalmers called

quantum mechanics

Quantum mechanics is the fundamental physical Scientific theory, theory that describes the behavior of matter and of light; its unusual characteristics typically occur at and below the scale of atoms. Reprinted, Addison-Wesley, 1989, It is ...

"a magnet for anyone who wants to find room for crazy properties of the mind", but not entirely without warrant.

The relationship between observation (and, by extension, consciousness) and the ''

wave-function collapse'' is known as the

measurement problem

In quantum mechanics, the measurement problem is the ''problem of definite outcomes:'' quantum systems have superpositions but quantum measurements only give one definite result.

The wave function in quantum mechanics evolves deterministically ...

. It seems that

atom

Atoms are the basic particles of the chemical elements. An atom consists of a atomic nucleus, nucleus of protons and generally neutrons, surrounded by an electromagnetically bound swarm of electrons. The chemical elements are distinguished fr ...

s,

photon

A photon () is an elementary particle that is a quantum of the electromagnetic field, including electromagnetic radiation such as light and radio waves, and the force carrier for the electromagnetic force. Photons are massless particles that can ...

s, etc. are in

quantum superposition

Quantum superposition is a fundamental principle of quantum mechanics that states that linear combinations of solutions to the Schrödinger equation are also solutions of the Schrödinger equation. This follows from the fact that the Schrödi ...

(which is to say, in many seemingly contradictory states or locations simultaneously) until measured in some way. This process is known as ''a wave-function collapse.'' According to the

Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics, one of the oldest interpretations and the most widely taught, it is the act of observation that collapses the wave-function''.''

Erwin Schrödinger

Erwin Rudolf Josef Alexander Schrödinger ( ; ; 12 August 1887 – 4 January 1961), sometimes written as or , was an Austrian-Irish theoretical physicist who developed fundamental results in quantum field theory, quantum theory. In particul ...

famously articulated the Copenhagen interpretation's unusual implications in the thought experiment now known as

Schrödinger's cat

In quantum mechanics, Schrödinger's cat is a thought experiment concerning quantum superposition. In the thought experiment, a hypothetical cat in a closed box may be considered to be simultaneously both alive and dead while it is unobserved, ...

. He imagines a box that contains a cat, a flask of poison, radioactive material, and a

Geiger counter

A Geiger counter (, ; also known as a Geiger–Müller counter or G-M counter) is an electronic instrument for detecting and measuring ionizing radiation with the use of a Geiger–Müller tube. It is widely used in applications such as radiat ...

. The apparatus is configured so that when the Geiger counter detects radioactive decay, the flask will shatter, poisoning the cat. Unless and until the Geiger counter detects the radioactive decay of a single atom, the cat survives. The radioactive decay the Geiger counter detects is a quantum event; each decay corresponds to a quantum state transition of a single atom of the radioactive material. According to Schrödinger's wave equation, until they are observed, quantum particles, including the atoms of the radioactive material, are in quantum state superposition; each unmeasured atom in the radioactive material is in a quantum superposition of ''decayed'' and ''not decayed''. This means that while the box remains sealed and its contents unobserved, the Geiger counter is also in a superposition of states of ''decay detected'' and ''no decay detected''; the vial is in a superposition of both ''shattered'' and ''not shattered'' and the cat in a superposition of ''dead'' and ''alive''. But when the box is unsealed, the observer finds a cat that is either dead or alive; there is no superposition of states. Since the cat is no longer in a superposition of states, then neither is the radioactive atom (nor the vial or the Geiger counter). Hence Schrödinger's wave function no longer holds and the wave function that described the atom—and its superposition of states—is said to have "collapsed": the atom now has only a single state, corresponding to the cat's observed state. But until an observer opens the box and thereby causes the wave function to collapse, the cat is both dead and alive. This has raised questions about, in John S. Bell's words, "where the observer begins and ends".

The measurement problem has largely been characterised as the clash of classical physics and quantum mechanics. Bohm argued that it is rather a clash of classical physics, quantum mechanics, and

phenomenology

Phenomenology may refer to:

Art

* Phenomenology (architecture), based on the experience of building materials and their sensory properties

Philosophy

* Phenomenology (Peirce), a branch of philosophy according to Charles Sanders Peirce (1839� ...

; all three levels of description seem to be difficult to reconcile, or even contradictory.

Though not referring specifically to quantum mechanics, Chalmers has written that if a

theory of everything

A theory of everything (TOE), final theory, ultimate theory, unified field theory, or master theory is a hypothetical singular, all-encompassing, coherent theoretical physics, theoretical framework of physics that fully explains and links togeth ...

is ever discovered, it will be a set of "psychophysical laws", rather than simply a set of physical laws.

With Chalmers as their inspiration, Bohm and Pylkkänen set out to do just that in their panprotopsychism. Chalmers, who is critical of the Copenhagen interpretation and most quantum theories of consciousness, has coined this "the Law of the Minimisation of Mystery".

The

many-worlds interpretation

The many-worlds interpretation (MWI) is an interpretation of quantum mechanics that asserts that the universal wavefunction is Philosophical realism, objectively real, and that there is no wave function collapse. This implies that all Possible ...

of quantum mechanics does not take observation as central to the wave-function collapse, because it denies that the collapse happens. On the many-worlds interpretation, just as the cat is both dead and alive, the observer both sees a dead cat and sees a living cat. Even though observation does not play a central role in this case, questions about observation are still relevant to the discussion. In

Roger Penrose

Sir Roger Penrose (born 8 August 1931) is an English mathematician, mathematical physicist, Philosophy of science, philosopher of science and Nobel Prize in Physics, Nobel Laureate in Physics. He is Emeritus Rouse Ball Professor of Mathematics i ...

's words:

I do not see why a conscious being need be aware of only "one" of the alternatives in a linear superposition. What is it about consciousnesses that says that consciousness must not be "aware" of that tantalising linear combination of both a dead and a live cat? It seems to me that a theory of consciousness would be needed for one to square the many world view with what one actually observes.

Chalmers believes that the tentative variant of panpsychism outlined in ''

The Conscious Mind'' (1996) does just that. Leaning toward the many-worlds interpretation due to its mathematical

parsimony, he believes his variety of panpsychist