Palaeotherium on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Palaeotherium'' is an extinct genus of equoid that lived in Europe and possibly the Middle East from the Middle

Three sculptures representing ''Palaeotherium magnum'', ''Palaeotherium medium'' and "''Plagiolophus minus''" (= '' Plagiolophus'') are part of the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs exhibition in the

Three sculptures representing ''Palaeotherium magnum'', ''Palaeotherium medium'' and "''Plagiolophus minus''" (= '' Plagiolophus'') are part of the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs exhibition in the

In 1968, upcoming German palaeontologist Jens Lorenz Franzen, then a graduate student, made major revisions of ''Palaeotherium'' in his dissertation. He invalidated several species as dubious names (''P. giganteum'' (considered to have been a

In 1968, upcoming German palaeontologist Jens Lorenz Franzen, then a graduate student, made major revisions of ''Palaeotherium'' in his dissertation. He invalidated several species as dubious names (''P. giganteum'' (considered to have been a

''Palaeotherium'' is the type genus of the Palaeotheriidae, largely considered to be one of two major hippomorph families in the superfamily

''Palaeotherium'' is the type genus of the Palaeotheriidae, largely considered to be one of two major hippomorph families in the superfamily

Derived palaeotheres are generally diagnosed as having selenolophodont ( selenodont-

Derived palaeotheres are generally diagnosed as having selenolophodont ( selenodont-

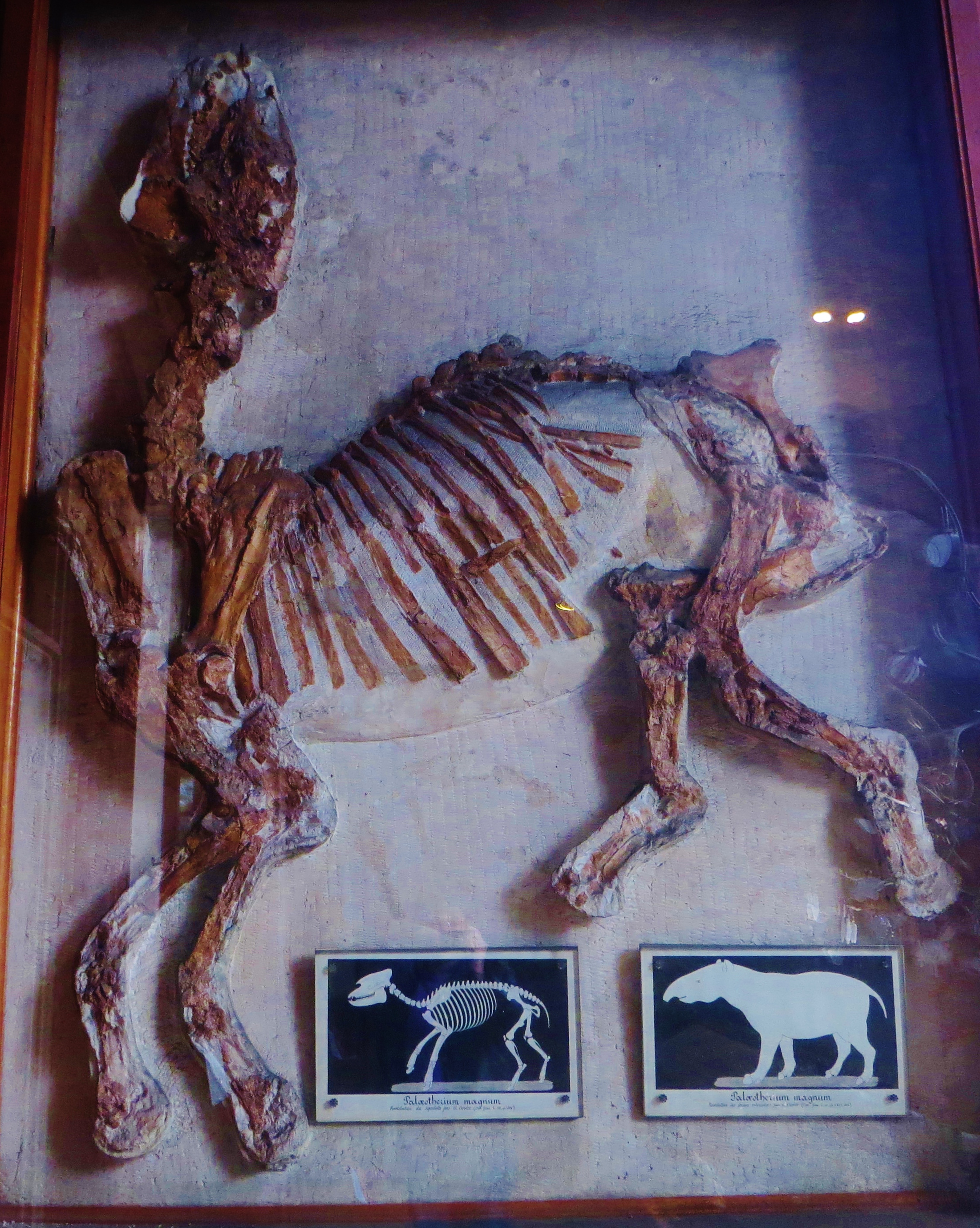

The overall postcranial anatomy of ''Palaeotherium'' is best known from a skeleton of ''P. magnum'' uncovered from Mormoiron. The

The overall postcranial anatomy of ''Palaeotherium'' is best known from a skeleton of ''P. magnum'' uncovered from Mormoiron. The

Several types of tracks have been suggested to belong to ''Palaeotherium'', among them the

Several types of tracks have been suggested to belong to ''Palaeotherium'', among them the

Eocene

The Eocene ( ) is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (Ma). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), Era. The name ''Eocene'' comes ...

to the Early Oligocene

The Oligocene ( ) is a geologic epoch (geology), epoch of the Paleogene Geologic time scale, Period that extends from about 33.9 million to 23 million years before the present ( to ). As with other older geologic periods, the rock beds that defin ...

. It is the type genus

In biological taxonomy, the type genus (''genus typica'') is the genus which defines a biological family and the root of the family name.

Zoological nomenclature

According to the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, "The name-bearin ...

of the Palaeotheriidae

Palaeotheriidae is an extinct family of herbivorous perissodactyl mammals that inhabited Europe, with less abundant remains also known from Asia, from the mid-Eocene to the early Oligocene. They are classified in Equoidea, along with the livin ...

, a group exclusive to the Palaeogene that was closest in relation to the Equidae

Equidae (commonly known as the horse family) is the Taxonomy (biology), taxonomic Family (biology), family of Wild horse, horses and related animals, including Asinus, asses, zebra, zebras, and many extinct species known only from fossils. The fa ...

, which contains horse

The horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') is a domesticated, one-toed, hoofed mammal. It belongs to the taxonomic family Equidae and is one of two extant subspecies of ''Equus ferus''. The horse has evolved over the past 45 to 55 mi ...

s plus their closest relatives and ancestors. Fossils of ''Palaeotherium'' were first described in 1782 by the French naturalist Robert de Lamanon and then closely studied by another French naturalist, Georges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, baron Cuvier (23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier (; ), was a French natural history, naturalist and zoology, zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuv ...

, after 1798. Cuvier erected the genus in 1804 and recognized multiple species based on overall fossil sizes and forms. As one of the first fossil genera to be recognized with official taxonomic authority, it is recognized as an important milestone within the field of palaeontology. The research by early naturalists on ''Palaeotherium'' contributed to the developing ideas of evolution, extinction, and succession and demonstrating the morphological diversity of different species within one genus.

Since Cuvier's descriptions, many other naturalists from Europe and the Americas recognized many species of ''Palaeotherium'', some valid, some reclassified to different genera afterward, and others being eventually rendered invalid. The German palaeontologist Jens Lorenz Franzen modernized its taxonomy due to his recognition of many subspecies as part of his dissertation in 1968, which were subsequently accepted by other palaeontologists. Today, there are fourteen known species recognized, many of which have multiple subspecies. In 1992, the French palaeontologist Jean-Albert Remy recognized two subgenera that most species are classified to based on cranial anatomies: the specialized ''Palaeotherium'' and the more generalized ''Franzenitherium''.

''Palaeotherium'' is an evolutionarily derived member of its family with tridactyl (or three-toed) forelimbs and hindlimbs, small post- canine diastema

A diastema (: diastemata, from Greek , 'space') is a space or gap between two teeth. Many species of mammals have diastemata as a normal feature, most commonly between the incisors and molars. More colloquially, the condition may be referred to ...

ta (gaps between teeth), and premolars

The premolars, also called premolar teeth, or bicuspids, are transitional teeth located between the canine and molar teeth. In humans, there are two premolars per quadrant in the permanent set of teeth, making eight premolars total in the mout ...

that are usually developed into molar-like forms. It shares many similar anatomical traits with other perissodactyls and has a large diversity in anatomical traits by species, with some species like ''P. magnum'', ''P. curtum'', and ''P. crassum'' being stockier in build and ''P. medium'' being more cursorial (or adapted for running). The genus ranges in size from the small species ''P. lautricense'', with an estimated weight of , to the massive ''P. giganteum'', thought to have been capable of weighing over . ''P. magnum'', known by two mostly complete skeletons from France, could have reached approximately in shoulder height and in length. The large-sized species were therefore amongst the largest mammals in the Eocene of Europe. ''Palaeotherium'' may have lived in herds and, as demonstrated by its dentition, was able to actively niche partition with another palaeothere '' Plagiolophus'' by specializing on softer leaves and fruit, although both were mostly leaf-eating.

''Palaeotherium'' and other genera of the subfamily Palaeotheriinae likely descended from the earlier subfamily Pachynolophinae, which lived in both Europe and Asia as opposed to North America unlike undisputed members of the Equidae. By the time that the first species ''P. eocaenum'' appeared in the middle Eocene, western Europe was an archipelago

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands. An archipelago may be in an ocean, a sea, or a smaller body of water. Example archipelagos include the Aegean Islands (the o ...

that was isolated from the rest of Eurasia, meaning that it and subsequent species lived in an environment with various other faunas that also evolved with strong levels of endemism. The Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula ( ), also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in south-western Europe. Mostly separated from the rest of the European landmass by the Pyrenees, it includes the territories of peninsular Spain and Continental Portugal, comprisin ...

had its own level of endemism with several species that are only known within the region, although they were replaced by more widespread species from central Europe by the late Eocene. Within both the middle and late Eocene, ''Palaeotherium'' consistently maintained a high species diversity and endured major environmental changes leading to a faunal turnover that occurred by the beginning of the late Eocene.

By the early Oligocene, most of its species went extinct along with many genera of western European mammals as part of the Grande Coupure

Grande means "large" or "great" in many of the Romance languages. It may also refer to:

Places

* Grande, Germany, a municipality in Germany

* Grande Communications, a telecommunications firm based in Texas

* Grande-Rivière (disambiguation)

* Ar ...

extinction and faunal turnover event, the causes of the extinctions being attributed mainly to environmental changes from increased glaciation and seasonality, negative interactions with immigrant faunas from Asia (competition and/or predation), or some combination of the two. ''P. medium'' survived past the Grande Coupure probably due to its cursorial nature that allowed it to travel across open lands more efficiently and escape immigrant carnivores; it was the last species of its genus and went extinct not long after the faunal turnover event.

Taxonomy

Research history

First descriptions

In 1782, the French naturalist Robert de Lamanon described a fossil skull including the upper and lower jaws that was collected from the quarries ofMontmartre

Montmartre ( , , ) is a large hill in Paris's northern 18th arrondissement of Paris, 18th arrondissement. It is high and gives its name to the surrounding district, part of the Rive Droite, Right Bank. Montmartre is primarily known for its a ...

, a hill near Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

that belonged to the nobleman Philippe-Laurent de Joubert. He recognized that the molars

The molars or molar teeth are large, flat tooth, teeth at the back of the mouth. They are more developed in mammal, mammals. They are used primarily to comminution, grind food during mastication, chewing. The name ''molar'' derives from Latin, '' ...

and incisor

Incisors (from Latin ''incidere'', "to cut") are the front teeth present in most mammals. They are located in the premaxilla above and on the mandible below. Humans have a total of eight (two on each side, top and bottom). Opossums have 18, wher ...

s were roughly similar to those of ruminant

Ruminants are herbivorous grazing or browsing artiodactyls belonging to the suborder Ruminantia that are able to acquire nutrients from plant-based food by fermenting it in a specialized stomach prior to digestion, principally through microb ...

s but noted that the dentition lacked modern analogues. Consequently, he hypothesized that the animal was extinct, had an amphibious lifestyle, and fed on both plants and fish.

Since 1796, the French naturalist Georges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, baron Cuvier (23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier (; ), was a French natural history, naturalist and zoology, zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuv ...

innovated the idea of vanished worlds of extinct animals, but as his observations of fossils were mostly limited to drawings and fragmentary fossils stored at the National Museum of Natural History, France

The French National Museum of Natural History ( ; abbr. MNHN) is the national natural history museum of France and a of higher education part of Sorbonne University. The main museum, with four galleries, is located in Paris, France, within the ...

, his palaeontological insight was limited early on. In 1798, he documented fossils from Montmartre, suggesting initially that they could have belonged to the canid

Canidae (; from Latin, ''canis'', "dog") is a family (biology), biological family of caniform carnivorans, constituting a clade. A member of this family is also called a canid (). The family includes three subfamily, subfamilies: the Caninae, a ...

genus ''Canis

''Canis'' is a genus of the Caninae which includes multiple extant taxon, extant species, such as Wolf, wolves, dogs, coyotes, and golden jackals. Species of this genus are distinguished by their moderate to large size, their massive, well-develo ...

'' based on dental morphology. Later in the same year, he instead suggested that the fossils belonged to a pachyderm that was most closely related to tapirs and had trunks like them. He also figured out that the animals of Montmartre were of multiple species with different sizes and numbers of toes. The fossils of Montmartre were credited with great importance to the field of palaeontology, as they were embedded in deeper and harder sediments than other fossil mammals such as ''Megatherium

''Megatherium'' ( ; from Greek () 'great' + () 'beast') is an extinct genus of ground sloths endemic to South America that lived from the Early Pliocene through the end of the Late Pleistocene. It is best known for the elephant-sized type spe ...

''. The science historian Bruno Belhoste argued that Cuvier's study of ''Palaeotherium'' in 1798 "marks the true birth of paleontology".

Early taxonomy and depictions

In 1804, Cuvier confirmed that the skull previously reported by de Lamanon belonged to a mammal. The skull preserves a complete set of 44 teeth that are similar to those ofrhinoceros

A rhinoceros ( ; ; ; : rhinoceros or rhinoceroses), commonly abbreviated to rhino, is a member of any of the five extant taxon, extant species (or numerous extinct species) of odd-toed ungulates (perissodactyls) in the family (biology), famil ...

es and hyrax

Hyraxes (), also called dassies, are small, stout, thickset, herbivorous mammals in the family Procaviidae within the order Hyracoidea. Hyraxes are well-furred, rotund animals with short tails. Modern hyraxes are typically between in length a ...

es. Cuvier recognized that the skull differs from other mammals and therefore established a new genus and species, ''Palaeotherium medium''. The genus name ''Palaeotherium'' means "ancient beast", which is a compound of the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

prefix () meaning 'old' or 'ancient' and the suffix () meaning 'beast' or 'wild animal'. He debunked Lamanon's hypothesis that ''Palaeotherium'' was an omnivorous amphibian and suspected that it had trunks akin to those of tapirs.

From 1804 up to 1824, Cuvier erected a total of 13 species of ''Palaeotherium'' based on skull, dental, and postcranial material. He erected the second of these species, ''P. magnum'', in 1804, explaining that it had similar but larger-sized dentition than ''P. medium''. In describing the third and small-sized species, ''P. minus'', he began to focus on the study of postcranial material rather than just cranial and dental material. In 1805, Cuvier erected ''P. crassum'' based on the three-toed forefeet, which were similar to tapirs and rhinoceroses in the shape of the metacarpal bones

In human anatomy, the metacarpal bones or metacarpus, also known as the "palm bones", are the appendicular bones that form the intermediate part of the hand between the phalanges (fingers) and the carpal bones ( wrist bones), which articulate ...

. In 1812, he named another species, ''P. curtum'', based on metacarpal bones that were slightly smaller than those of ''P. crassum''. As of 1968, four of the ''Palaeotherium'' species named by Cuvier were considered valid and remained classified in ''Palaeotherium'' (''P. medium'', ''P. magnum'', ''P. crassum'', ''P. curtum''), six were valid but were eventually reclassified to different genera by different palaeontologists (''P. minus'', ''P. tapiroïdes'', ''P. buxovillanum'', ''P. aurelianense'', ''P. occitanicum'', and ''P. isselanum''), and three were considered invalid (''P. giganteum'', ''P. latum'', and ''P. indeterminatum'').

In 1812, Cuvier defined ''Palaeotherium'' as containing only tridactyl (or three-toed) species. He also speculated on life appearance and behaviour of several ''Palaeotherium'' species, but cautioned that such interpretations are limited by the fragmentary fossil material. He suggested that ''P. magnum'' would have resembled a horse-sized tapir with sparse hair. ''P. crassum'' and ''P. medium'' would also have had a tapir-like appearance, with proportionally longer legs and feet in the latter. Cuvier also published a speculative skeletal reconstruction of ''P. minus'' and hypothesized that it was smaller than a sheep and potentially cursorial given its slender legs and face. Finally, he theorized that ''P. curtum'' would have been the bulkiest species. In 1822, Cuvier published a reconstruction of the skeleton of ''P. magnum'', outlining that it was the size of a Javan rhinoceros

The Javan rhinoceros (''Rhinoceros sondaicus''), Javan rhino, Sunda rhinoceros or lesser one-horned rhinoceros is a critically endangered member of the genus ''Rhinoceros'', of the rhinoceros family Rhinocerotidae, and one of the five remainin ...

, was stocky in build, and had a massive head. The same year, ''Palaeotherium'' was also depicted in drawings by the French palaeontologist Charles Léopold Laurillard under the direction of Cuvier.

Three sculptures representing ''Palaeotherium magnum'', ''Palaeotherium medium'' and "''Plagiolophus minus''" (= '' Plagiolophus'') are part of the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs exhibition in the

Three sculptures representing ''Palaeotherium magnum'', ''Palaeotherium medium'' and "''Plagiolophus minus''" (= '' Plagiolophus'') are part of the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs exhibition in the Crystal Palace Park

Crystal Palace Park is a park in south-east London, Grade II* listed on the Register of Historic Parks and Gardens. It was laid out in the 1850s as a pleasure ground, centred around the re-location of The Crystal Palace – the largest glass ...

in London, which has been open to the public since 1854 and was created by the English sculptor Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins. Both the ''P. magnum'' sculpture, the largest of the three, and the medium-sized ''P. medium'' sculpture were posed in a standing position, whereas the smaller "''P. minus''" sculpture depicts a sitting animal. The resemblance of the models to tapirs reflects early perceptions of the life appearance of ''Palaeotherium''. However, the sculptures differ from living tapirs in several ways, such as shorter and taller faces, higher eye positions, slimmer legs, longer tails, and the presence of three toes on the forelimbs unlike the four toes of tapirs.

Of the three sculptures, ''P. medium'' most closely resembles a tapir, and it has remained mostly intact. ''P. medium'' was depicted as having thick skin and a slender face and trunk, representing outdated perceptions that it was a slow animal. The original ''P. magnum'' sculpture was last known from a 1958 photograph before it was lost at some point afterward (it was replaced by a new republicated model in 2023); the photograph reveals that it was the largest of the three sculptures and had a robust and muscular build with large and deep eyes, a proportionally large head, and bulky legs. The model's trunk was wide and descended below the lower lip. The overall anatomy appears to be based on elephants.

''Palaeotherium'' proved to be a significant find to the field of palaeontology in multiple other aspects. For one, both the skeletal reconstruction drawing and the life restoration in Cuvier's works were incorporated into textbooks and handbooks around the world up to the 20th century. The genus was also incorporated into old orthogenesis

Orthogenesis, also known as orthogenetic evolution, progressive evolution, evolutionary progress, or progressionism, is an Superseded theories in science, obsolete biological hypothesis that organisms have an innate tendency to evolution, evolve ...

models of the evolution of the horse

The evolution of the horse, a mammal of the family Equidae, occurred over a geologic time scale of 50 million years, transforming the small, dog-sized, forest-dwelling '' Eohippus'' into the modern horse. Paleozoologists have been able to piece ...

theory as early as 1851 by British biologist Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist and paleontology, palaeontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkabl ...

and followed by other 19th century European naturalists such as Jean Albert Gaudry and Vladimir Kovalevsky.

Later 19th century taxonomy

In the 19th century, several of Cuvier's ''Palaeotherium'' species have been reclassified under different genera. "''P.''" ''aurelianense'' was reclassified as its own genus '' Anchitherium'' by the German palaeontologist Hermann von Meyer in 1844. In an 1839–1864 osteography, the French naturalistHenri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville

Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville (; 12 September 1777 – 1 May 1850) was a French zoologist and anatomist.

Life

Blainville was born at Arques-la-Bataille, Arques, near Dieppe, Seine-Maritime, Dieppe. As a young man, he went to Paris to study a ...

relisted "''P.''" ''tapiroides'', "''P.''" ''buxovillanum'' and "''P.''" ''occitanicum'' as species belonging to '' Lophiodon'', but the latter two were eventually moved to '' Paralophiodon'' and '' Lophiaspis'', respectively, in the 20th century. In 1862, Swiss zoologist Ludwig Ruetimeyer considered the previously recognised genera ''Plagiolophus'' and '' Propalaeotherium'' as distinct from ''Palaeotherium''; these contain the species ''P. minor'' and ''P. isselanum'', respectively.

The 19th century also saw the erection of several new ''Palaeotherium'' species. In 1853, French palaeontologist Auguste Pomel erected the species ''P. duvali'' based on limb bones that he thought were less stocky than those of ''P. curtum''. In his 1839–1864 osteography, Blainville erected ''P. girondicum'', pointing out that its fossils were from the Gironde

Gironde ( , US usually , ; , ) is the largest department in the southwestern French region of Nouvelle-Aquitaine. Named after the Gironde estuary, a major waterway, its prefecture is Bordeaux. In 2019, it had a population of 1,623,749.

Basin and that Cuvier only briefly referenced it in an 1825 publication. In 1863, the French naturalist Jean-Baptiste Noulet created the species ''P. castrense'' based on an incomplete mandible

In jawed vertebrates, the mandible (from the Latin ''mandibula'', 'for chewing'), lower jaw, or jawbone is a bone that makes up the lowerand typically more mobilecomponent of the mouth (the upper jaw being known as the maxilla).

The jawbone i ...

that was uncovered from the commune of Viviers-lès-Montagnes that was placed in a fossil collection from Castres

Castres (; ''Castras'' in the Languedocian dialect, Languedocian dialect of Occitan language, Occitan) is the sole Subprefectures in France, subprefecture of the Tarn (department), Tarn Departments of France, department in the Occitania (adminis ...

. In 1869, Swiss palaeontologists Pictet and Humbert

Humbert, Umbert or Humberto (Latinized ''Humbertus'') is a Germanic given name, from ''hun'' "warrior" and ''beraht'' "bright". It also came into use as a surname.

Given name

;Royalty and Middle Ages

* Emebert (died 710)

* Humbert of Maroilles ...

erected the species ''Plagiolophus siderolithicus'' based on molars that are similar to those of ''P. minor'' but were smaller in size. The same year, German palaeontologist Oscar Fraas erected ''P. suevicum'' based on teeth that he thought had distinct enamel. The French naturalist Paul Gervais

Paul Gervais (full name: François Louis Paul Gervais) (26 September 1816 – 10 February 1879) was a French palaeontologist and entomologist.

Biography

Gervais was born in Paris, where he obtained the diplomas of doctor of science and of medic ...

, in 1875, described fossil bones and teeth from the French commune of Dampleux, noting that they belonged to a species smaller than other ''Palaeotherium'' species and with dental dimensions similar to those of ''Plagiolophus minor''. He assigned the fossils to the newly erected species ''P. eocaenum''.

''Palaeotherium'' skeletons

In 1873, the French geologist Gaston Casimir Vasseur uncovered the first complete skeleton of ''Palaotherium'', attributed to ''P. magnum'', from a gypsum quarry in the commune ofVitry-sur-Seine

Vitry-sur-Seine () is a commune in the southeastern suburbs of Paris, France, from the centre of Paris.

Name

Vitry-sur-Seine was originally called simply Vitry. The name Vitry comes from Medieval Latin ''Vitriacum'', and before that ''Victori ...

. The quarry was owned by the civil engineer Fuchs, who donated the skeleton to the National Museum of Natural History, France. The skeleton was described by Gervais in the same year, who noted that the neck was longer than expected and that the build was less stocky than that of tapirs and rhinoceroses. The skull of the specimen measures long. The naturalist said that the excavation of the specimen was difficult but completed by multiple skillful workers. Since its description, it has been displayed at the Gallery of Paleontology and Comparative Anatomy of the museum as an important and famous component.

During the 20th century, a second complete skeleton of ''P. magnum'' was excavated from the plasters in the French commune of Mormoiron. It was sent to the geological department of the University of Lyon

The University of Lyon ( , or UdL) is a university system ( ''ComUE'') based in Lyon, France. It comprises 12 members and 9 associated institutions. The 3 main constituent universities in this center are: Claude Bernard University Lyon 1, which f ...

and described after preparation by the Austrian geologist Frédéric Roman in 1922. Roman published a reconstruction of the skeleton in his 1922 monography. According to Austrian palaeontologist Othenio Abel

Othenio Lothar Franz Anton Louis Abel (20 June 1875 – 4 July 1946) was an Austrian paleontologist and evolutionary biologist. Together with Louis Dollo, he was the founder of " paleobiology" and studied the life and environment of fossilized ...

in 1924, it was the most complete skeleton of ''Palaeotherium'' and amongst the most complete of any early Cenozoic mammal known at the time, missing only a few ribs and the left femur

The femur (; : femurs or femora ), or thigh bone is the only long bone, bone in the thigh — the region of the lower limb between the hip and the knee. In many quadrupeds, four-legged animals the femur is the upper bone of the hindleg.

The Femo ...

.

20th century revisions

In 1904, Swiss palaeontologist Hans Georg Stehlin created the species ''P. lautricense'' based on an upper jaw stored in the Muséum de Toulouse that originated from sandstone deposits at Castres. He also assigned two somewhat crushed skulls to this species. In his monography on palaeotheres, published the same year, Stehlin considered most species of ''Palaeotherium'' as potentially valid, but noted that most taxonomists were reluctant to invalidate species erected by Cuvier. Stehlin considered ''P. girondicum'' to be a form of ''P. magnum'', and described two forms of ''P. curtum'' from jaw fragments from La Débruge. He also named three new species – ''P. Mühlbergi'', based on dental material from the Swiss municipality of Obergösgen; ''P. Renevieri'', based on new finds from Mormont and a mandible identified by Pictet in 1869; and ''P. Rütimeyeri'', from the municipality ofEgerkingen

Egerkingen is a Municipalities of Switzerland, municipality in the district of Gäu (district), Gäu in the Cantons of Switzerland, canton of Solothurn (canton), Solothurn in Switzerland.

History

Egerkingen is first mentioned in 1201 as ''in Egri ...

, which he described as having primitive premolars. In 1917, French palaeontologist Charles Depéret

Charles Jean Julien Depéret (25 June 1854 – 18 May 1929) was a French geologist and paleontologist. He was a member of the French Academy of Sciences, the Société géologique de France

recognized two additional species of ''Palaeotherium'' – ''P. Euzetense'' and ''P. Stehlini''.

In 1968, upcoming German palaeontologist Jens Lorenz Franzen, then a graduate student, made major revisions of ''Palaeotherium'' in his dissertation. He invalidated several species as dubious names (''P. giganteum'' (considered to have been a

In 1968, upcoming German palaeontologist Jens Lorenz Franzen, then a graduate student, made major revisions of ''Palaeotherium'' in his dissertation. He invalidated several species as dubious names (''P. giganteum'' (considered to have been a rhinocerotid

A rhinoceros ( ; ; ; : rhinoceros or rhinoceroses), commonly abbreviated to rhino, is a member of any of the five extant taxon, extant species (or numerous extinct species) of odd-toed ungulates (perissodactyls) in the family (biology), famil ...

instead), ''P. gracile'', ''P. parvulum'', ''P. commune'', ''P. primaevum'', and ''P. gervaisii'') and synonymized many others with ''P. magnum'' (''P. aniciense'', ''P. subgracile''), ''P. medium'' (''P. brivatense'', ''P. moeschi''), ''P. crassum'' (''P. indeterminatum''), ''P. curtum'' (''P. latum'' and ''P. buseri''), ''P. duvali'' (''P. kleini''), and ''P. muehlbergi'' (''P. velaunum''). He additionally invalidated many species that had been erected throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries. He also erected ''P. pomeli'' based on fossils from a locality in Castres and reclassified "''Plagiolophus''" ''siderolithicum'' as a species of ''Palaeotherium''. Furthermore, Franzen converted some species into subspecies (''P. magnum girondicum'', ''P. magnum stehlini'', ''P. medium suevicum'', and ''P. medium euzetense'') and named six additional subspecies.

In 1975, Spanish palaeontologist María Lourdes Casanovas-Cladellas erected the species ''P. crusafonti'' from a left maxilla

In vertebrates, the maxilla (: maxillae ) is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. The two maxil ...

with dentition from the Spanish site of Roc de Santa. In 1980, both she and José-Vicente Santafé Llopis established a second Iberian species, ''P. franzeni'', from the Spanish municipality of Sossís based on differences in dentition. In 1985, the French palaeontologist Jean-Albert Remy named a new subspecies, ''P. muehlbergi thaleri'', in honor of fellow palaeontologist Louis Thaler; these fossils, consisting of two skulls with mandibles, were from the commune of Saint-Étienne-de-l'Olm.

In 1991, Casanovas-Cladellas and Santafé Llopis erected ''P. llamaquiquense'' from partial jaw material from the Spanish locality of Llamaquique in the city of Oviedo

Oviedo () or Uviéu (Asturian language, Asturian: ) is the capital city of the Principality of Asturias in northern Spain and the administrative and commercial centre of the region. It is also the name of the municipality that contains th ...

, where the name derived from. The next year in 1992, Remy proposed the creation of two subgenera of ''Palaeotherium'' based on cranial characteristics: ''Palaeotherium'' and ''Franzenitherium''. In 1993, the Spanish palaeontologist Miguel Ángel Cuesta Ruiz-Colmenares established the species ''P. giganteum'' based on teeth from the Mazaterón site in the Duero Basin, considering it to be the largest species of ''Palaeotherium'' known. In 1998, Casanovas-Cladellas et al. erected the subspecies ''P. crassum sossissense'' from a fragmented right maxilla with dentition from Sossís in Spain. They also invalidated the previously named ''P. franzeni'' and reassigned the material to ''P. magnum stehlini''.

Classification

''Palaeotherium'' is the type genus of the Palaeotheriidae, largely considered to be one of two major hippomorph families in the superfamily

''Palaeotherium'' is the type genus of the Palaeotheriidae, largely considered to be one of two major hippomorph families in the superfamily Equoidea

Equoidea is a superfamily of hippomorph perissodactyls containing the Equidae, Palaeotheriidae, and other basal equoids of unclear affinities, of which members of the genus '' Equus'' are the only extant species. The earliest fossil record of ...

, the other being the Equidae

Equidae (commonly known as the horse family) is the Taxonomy (biology), taxonomic Family (biology), family of Wild horse, horses and related animals, including Asinus, asses, zebra, zebras, and many extinct species known only from fossils. The fa ...

. Alternatively, some authors have proposed that equids are more closely related to the Tapiromorpha than to the Palaeotheriidae. It is also usually thought to consist of two families, the Palaeotheriinae and Pachynolophinae; a few authors alternatively have argued that pachynolophines are more closely related to other perissodactyl groups than to palaeotheriines. Some authors have also considered the Plagiolophinae to be a separate subfamily, while others group its genera into the Palaeotheriinae. ''Palaeotherium'' has also been suggested to belong to the tribe Palaeotheriini, one of three proposed tribes within the Palaeotheriinae along with the Leptolophini and Plagiolophini. The Eurasian distribution of the palaeotheriids (or palaeotheres) were in contrast to equids, which are generally thought to have been an endemic radiation in North America. Some of the most basal equoids of the European landmass are of uncertain affinities, with some genera being thought to potentially belong to the Equidae. Palaeotheres are well-known for having lived in western Europe during much of the Palaeogene but were also present in eastern Europe, possibly the Middle East, and, in the case of pachynolophines (or pachynolophs), Asia.

The Perissodactyla makes its earliest known appearance in the European landmass in the MP7 faunal unit of the Mammal Palaeogene zones. During the temporal unit, many genera of basal equoids such as ''Hyracotherium

''Hyracotherium'' ( ; "hyrax-like beast") is an extinction, extinct genus of small (about 60 cm in length) perissodactyl ungulates that was found in the London Clay formation. This small, fox-sized animal is (for some scientists) considered t ...

'', '' Pliolophus'', '' Cymbalophus'', and '' Hallensia'' made their first appearances there. A majority of the genera persisted to the MP8-MP10 units, and pachynolophines such as ''Propalaeotherium'' and '' Orolophus'' arose by MP10. The MP13 unit saw the appearances of later pachynolophines such as '' Pachynolophus'' and '' Anchilophus'' along with definite records of the first palaeotheriines such as ''Palaeotherium'' and '' Paraplagiolophus''. The palaeotheriine ''Plagiolophus'' has been suggested to have potentially made an appearance by MP12. It was by MP14 that the subfamily proceeded to diversify, and the pachynolophines were generally replaced but still reached the late Eocene. In addition to more widespread palaeothere genera such as ''Plagiolophus'', ''Palaeotherium'', and '' Leptolophus'', some of their species reaching medium to large sizes, various other palaeothere genera that were endemic to the Iberian Peninsula, such as '' Cantabrotherium'', '' Franzenium'', and '' Iberolophus'', appeared by the middle Eocene.

The phylogenetic tree for several members of the family Palaeotheriidae, as well as three outgroups, as created by Remy in 2017 and followed by Remy et al. in 2019 is defined below:

As shown in the above phylogeny, the Palaeotheriidae is recovered as a monophyletic

In biological cladistics for the classification of organisms, monophyly is the condition of a taxonomic grouping being a clade – that is, a grouping of organisms which meets these criteria:

# the grouping contains its own most recent co ...

clade, meaning that it did not leave any derived descendant groups in its evolutionary history. ''Hyracotherium'' ''sensu stricto'' (in a strict sense) is defined as amongst the first offshoots of the family and a member of the Pachynolophinae. "''H.''" ''remyi'', formerly part of the now-invalid genus ''Propachynolophus'', is defined as a sister taxon to more derived palaeotheres. Both ''Pachynolophus'' and '' Lophiotherium'', defined as pachynolophines, are defined as monophyletic genera. The other pachynolophines '' Eurohippus'' and ''Propalaeotherium'' consistute a paraphyletic clade in relation to members of the derived and monophyletic subfamily Palaeotheriinae (''Leptolophus'', ''Plagiolophus'', and ''Palaeotherium''), thus making Pachynolophinae a paraphyletic subfamily clade.

Inner systematics

Since 1968, many species of ''Palaeotherium'' have multiple defined subspecies that are justified by various intraspecific variations. Later since 1992, two subgenera are officially recognized for ''Palaeotherium''. The first of these subgenera is ''Palaeotherium'', which includes the type species ''P. magnum'' along with ''P. medium'', ''P. crassum'', ''P. curtum'', ''P. castrense'', ''P. siderolithicum'', and ''P. muehlbergi''. The second subgenus is ''Franzenitherium'', which includes the type species ''P. lautricense'' as well as ''P. duvali'' and was named in honor of Franzen's review of ''Palaeotherium''. The subgenus ''Palaeotherium'' is distinct from another subgenus ''Franzenitherium'' based on specialized traits. For example, the orbit of ''Palaeotherium'' being aligned in front of the skull's midlength is a specialized trait compared to that of ''Franzenitherium'' being aligned more with the skull's midlength. Several ''Palaeotherium'' species are too fragmentary to be placed in any of the subgenera. The following table lists all valid species and subspecies of ''Palaeotherium'', the subgenus that each is classified to, the Mammal Palaeogene faunal units that they are recorded from based on fossil deposit appearances, the authors who named the taxa, and the year that they were formally named:Description

Skull

The Palaeotheriidae are distinguished from other perissodactyls mostly based on features of the skull. For example, theorbits

In celestial mechanics, an orbit (also known as orbital revolution) is the curved trajectory of an physical body, object such as the trajectory of a planet around a star, or of a natural satellite around a planet, or of an satellite, artificia ...

are generally wide open at the back and are located in the middle of the skull or slightly more frontwards. The nasal bone

The nasal bones are two small oblong bones, varying in size and form in different individuals; they are placed side by side at the middle and upper part of the face and by their junction, form the bridge of the upper one third of the nose.

Eac ...

s of palaeotheres are thick to very thick. ''Palaeotherium'' itself is characterized by several cranial traits that distinguish it from other palaeothere genera such as an elongated zygomatic process

The zygomatic processes (aka. malar) are three processes (protrusions) from other bones of the skull which each articulate with the zygomatic bone. The three processes are:

* Zygomatic process of frontal bone from the frontal bone

* Zygomatic ...

of the squamosal bone

The squamosal is a skull bone found in most reptiles, amphibians, and birds. In fishes, it is also called the pterotic bone.

In most tetrapods, the squamosal and quadratojugal bones form the cheek series of the skull. The bone forms an ancestral ...

extending to the maxilla

In vertebrates, the maxilla (: maxillae ) is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. The two maxil ...

and the presence of an anastomosis

An anastomosis (, : anastomoses) is a connection or opening between two things (especially cavities or passages) that are normally diverging or branching, such as between blood vessels, leaf veins, or streams. Such a connection may be normal (su ...

(anatomical connection between two passageways) roughly at the sphenoid bone

The sphenoid bone is an unpaired bone of the neurocranium. It is situated in the middle of the skull towards the front, in front of the basilar part of occipital bone, basilar part of the occipital bone. The sphenoid bone is one of the seven bon ...

and prominent temporalis muscle

In anatomy, the temporalis muscle, also known as the temporal muscle, is one of the muscles of mastication (chewing). It is a broad, fan-shaped convergent muscle on each side of the head that fills the temporal fossa, superior to the zygomatic a ...

developments. The calvaria ranges in base length from to depending on the species.

The height and weight proportions of the skull of ''Palaeotherium'' are roughly equivalent with those of other taxa within the Equoidea; members of the superfamily have relatively shortened front facial areas. The skull's top peaks at the far back area, although this is not observed in ''P. lautricense''. The sagittal crest

A sagittal crest is a ridge of bone running lengthwise along the midline of the top of the skull (at the sagittal suture) of many mammalian and reptilian skulls, among others. The presence of this ridge of bone indicates that there are excepti ...

can be prominent and depends on the age and sex of the individual for development. In comparison to other equoids where the skull's maximum width extends above the front root of the parallel zygomatic arch

In anatomy, the zygomatic arch (colloquially known as the cheek bone), is a part of the skull formed by the zygomatic process of temporal bone, zygomatic process of the temporal bone (a bone extending forward from the side of the skull, over the ...

es, those of ''Palaeotherium'' and most other palaeotheres (except ''Leptolophus'') extend back to the joint of the squamosal bone and mandible. The orbit on the skull of ''Palaeotherium'', unlike that of other equoids, is proportionally smaller and located somewhat in front of the skull's midlength, the latter trait of which may be further extended in the case of ''P. medium''. Similar to other Palaeogene equoids, the front edge of the orbit is aligned with M1 or M2 while the back area is wide. Unlike most other palaeotheres, its nasal opening stretches up to the P3 tooth at minimum or up to the front edge of the orbit above M3 in the case of ''P. magnum''. While the shapes and proportions of the nasal bones vary by species, they extend beyond P1 in adults and sometimes even the canine like in equine

Equinae is a subfamily of the family Equidae, known from the Hemingfordian stage of the Early Miocene (16 million years ago) onwards. They originated in North America, before dispersing to every continent except Australia and Antarctica. They are ...

s. The temporal fossa

The temporal fossa is a fossa (shallow depression) on the side of the skull bounded by the temporal lines above, and the zygomatic arch below. Its floor is formed by the outer surfaces of four bones of the skull. The fossa is filled by the te ...

e are large but vary in proportion. The cranial vault

The cranial vault is the space in the skull within the neurocranium, occupied by the brain.

Development

In humans, the cranial vault is imperfectly composed in newborns, to allow the large human head to pass through the birth canal. During bir ...

is broad, domed, and wider than the overall skull.

The horizontal ramus of the mandible is overall thick plus tall and has an elongated mandibular symphysis

In human anatomy, the facial skeleton of the skull the external surface of the mandible is marked in the median line by a faint ridge, indicating the mandibular symphysis (Latin: ''symphysis menti'') or line of junction where the two lateral ha ...

, but the width and lower area morphology vary by species. It is wide in both the front and back areas and low compared to equines. The joint for the squamosal and mandible of ''Palaeotherium'' is low compared to those of ''Plagiolophus'' and ''Leptolophus''. The angular process, located above the angle of the mandible

__NOTOC__

The angle of the mandible (a.k.a. gonial angle, Masseteric Tuberosity, and Masseteric Insertion) is located at the posterior border at the junction of the lower border of the ramus of the mandible.

The angle of the mandible, which may ...

, is blocked from further expansion by the mandibular notch and is well-developed in its rear like in Palaeogene equids.

Dentition

lophodont

The molars or molar teeth are large, flat teeth at the back of the mouth. They are more developed in mammals. They are used primarily to grind food during chewing. The name ''molar'' derives from Latin, ''molaris dens'', meaning "millstone tooth ...

ridge form) upper molars (M/m) and selenodont (crescent-shaped ridge form) lower molars that are mesodont, or medium-crowned, in height. The canines (C/c) strongly protrude and are separated from the premolars (P/p) by medium to long diastema

A diastema (: diastemata, from Greek , 'space') is a space or gap between two teeth. Many species of mammals have diastemata as a normal feature, most commonly between the incisors and molars. More colloquially, the condition may be referred to ...

ta (gaps between two close teeth) and from the incisors (I/i) by short ones in both the upper and lower dentition. The other teeth are paired closely with each other in both the upper and lower rows. The dental formula

Dentition pertains to the development of teeth and their arrangement in the mouth. In particular, it is the characteristic arrangement, kind, and number of teeth in a given species at a given age. That is, the number, type, and morpho-physiology ...

of ''Palaeotherium'' is for a total of 44 teeth, consistent with the primitive dental formula for early-middle Palaeogene placental

Placental mammals (infraclass Placentalia ) are one of the three extant subdivisions of the class Mammalia, the other two being Monotremata and Marsupialia. Placentalia contains the vast majority of extant mammals, which are partly distinguished ...

mammals.

The incisors are shovel-shaped and, like in modern horses, are used for chewing at right angles in relation to their longitudinal axes. They have no cutting functions but instead are used for grasping food akin to how tweezers grasp items. The canines are proportionally large and dagger-shaped. They were probably not used for cutting or chewing given how they are oriented, but may have been used in self-defence and conspecific fights. The decreased length of the postcanine diastema in ''Palaeotherium'' and the equid subfamily Anchitheriinae

The Anchitheriinae are an extinct subfamily of the Perissodactyla family Equidae, the same family which includes modern horses, zebras and donkeys. This subfamily is more primitive than the living members of the family. The group first appeared ...

may be correlated with increases in body size. This trend may be due to the necessity to improve chewing performances through molarization and proportional size increases of the premolars. Postcanine diastemata are strongly reduced in early species such as ''P. castrense''; in later species, they vary from small (''P. crassum'', ''P. curtum'') to large (''P. medium'', ''P. magnum''). The separation of cheek teeth from the incisors and canines attests to their independent and specific chewing functions.

The premolars and preceding deciduous teeth

Deciduous teeth or primary teeth, also informally known as baby teeth, milk teeth, or temporary teeth,Fehrenbach, MJ and Popowics, T. (2026). ''Illustrated Dental Embryology, Histology, and Anatomy'', 6th edition, Elsevier, page 287–296. are ...

both tend to have molarized forms (meaning molar-like shapes) and have newly developing hypocone cusps on them. The forms of the deciduous premolars (dP) of juvenile ''Palaeotherium'' and other palaeotheriines distinguish them from the earlier pachynolophines, where the dP2-dP4 of juvenile ''P. renevieri'' and ''P. magnum'' are both molarized and four-cusped (although dP1 is triangular). Late Eocene species of ''Palaeotherium'' tend to have more molariform premolars. The non-molarized premolars are composed of four to five cusps (one to two external, two intermediate, and one internal) while the molarized premolars and molars have six cusps (two external, two intermediate, and two internal). The upper molars are medium-crowned (shorter than those of modern equids) and have ectolophs (crests or ridges of upper molar teeth) that are about twice the height of the inner cusps and curve into a W shape. The W-shaped ectolophs themselves are made up of two articulated crescents. The lower molarized premolars and molars are about half as wide as their upper counterparts. The mesostyle cusp (a small cusp type) present in the molars thicken from M1 to M3. The lingual lobes (or divisions) in the upper molars are closely aligned with the ectolophs.

Postcranial skeleton

vertebral column

The spinal column, also known as the vertebral column, spine or backbone, is the core part of the axial skeleton in vertebrates. The vertebral column is the defining and eponymous characteristic of the vertebrate. The spinal column is a segmente ...

is made up of seven large cervical vertebrae

In tetrapods, cervical vertebrae (: vertebra) are the vertebrae of the neck, immediately below the skull. Truncal vertebrae (divided into thoracic and lumbar vertebrae in mammals) lie caudal (toward the tail) of cervical vertebrae. In saurop ...

, seventeen thoracic vertebrae

In vertebrates, thoracic vertebrae compose the middle segment of the vertebral column, between the cervical vertebrae and the lumbar vertebrae. In humans, there are twelve thoracic vertebra (anatomy), vertebrae of intermediate size between the ce ...

, six lumbar vertebrae

The lumbar vertebrae are located between the thoracic vertebrae and pelvis. They form the lower part of the back in humans, and the tail end of the back in quadrupeds. In humans, there are five lumbar vertebrae. The term is used to describe t ...

, six sacral vertebrae

The sacrum (: sacra or sacrums), in human anatomy, is a triangular bone at the base of the spine that forms by the fusing of the sacral vertebrae (S1S5) between ages 18 and 30.

The sacrum situates at the upper, back part of the pelvic cavity, ...

, and fifteen caudal vertebrae

Caudal vertebrae are the vertebrae of the tail in many vertebrates. In birds, the last few caudal vertebrae fuse into the pygostyle, and in apes, including humans, the caudal vertebrae are fused into the coccyx.

In many reptiles, some of the caud ...

. The cervical vertebrae, comprising the neck, measure long while the caudal vertebrae, comprising the tail, measure long. The sacrum

The sacrum (: sacra or sacrums), in human anatomy, is a triangular bone at the base of the spine that forms by the fusing of the sacral vertebrae (S1S5) between ages 18 and 30.

The sacrum situates at the upper, back part of the pelvic cavity, ...

is triangular and similar to that of the Equidae, but is slightly wider in its front area. ''P. magnum'' would have had a total of thirty-four ribs based on the total number of thoracic vertebrae. Like in equids, the front ribs are strong and flattened. The back portion of the thorax

The thorax (: thoraces or thoraxes) or chest is a part of the anatomy of mammals and other tetrapod animals located between the neck and the abdomen.

In insects, crustaceans, and the extinct trilobites, the thorax is one of the three main di ...

would have been wider than in horses and roughly comparable to those of tapirs and rhinoceroses but was not as long as that of the latter. The ribs are separated from the sternum

The sternum (: sternums or sterna) or breastbone is a long flat bone located in the central part of the chest. It connects to the ribs via cartilage and forms the front of the rib cage, thus helping to protect the heart, lungs, and major bl ...

, which is approximately the same size as the thorax.

''P. magnum'' has generally strong and stocky limb bones. The femora (upper thigh bones) of ''P. crassum'' and ''P. medium'', in comparison, are less robust. ''Palaeotherium'' has a straighter and less concave trochlea of the astragalus than ''Plagiolophus''. The calcaneum

In humans and many other primates, the calcaneus (; from the Latin ''calcaneus'' or ''calcaneum'', meaning heel; : calcanei or calcanea) or heel bone is a bone of the tarsus of the foot which constitutes the heel. In some other animals, it is t ...

is semirectangular in shape but slightly wider on its rear end. The cuboid bone

In the human body, the cuboid bone is one of the seven tarsal bones of the foot.

Structure

The cuboid bone is the most lateral of the bones in the distal row of the tarsus. It is roughly cubical in shape, and presents a prominence in its infer ...

is high and narrow, similar to that of ''Anchitherium''.

Most species of ''Palaeotherium'' have tridactyl (three-toed) hindlimbs and forelimbs, in contrast to earlier palaeotheres that have tetradactyl (four-toed) forelimbs and tridactyl hindlimbs. ''P. eocaenum'' might have had a tetradactyl forelimb, as indicated by a manus that has been tentatively assigned to it. ''Palaeotherium'' differs from ''Plagiolophus'' in its long and narrow carpals and in its metacarpal bones, which are close in length to each other and develop into wide ungual

An ungual (from Latin ''unguis'', i.e. ''nail'') is a highly modified distal toe bone which ends in a hoof, claw, or nail. Elephants and ungulates have ungual phalanges, as did the sauropod

Sauropoda (), whose members are known as sauropods (; ...

phalanges

The phalanges (: phalanx ) are digit (anatomy), digital bones in the hands and foot, feet of most vertebrates. In primates, the Thumb, thumbs and Hallux, big toes have two phalanges while the other Digit (anatomy), digits have three phalanges. ...

. The tridactyl foot morphology with all three digits being functional suggests digitigrade locomotion.

''Palaeotherium'' shows an exceptional amount of variation in the shape of its third metacarpal and its manus dimensions. ''P. curtum'' has very robust forelimb bones including a short and stocky manus, which suggests that it was stocky in build. ''P. magnum'' and ''P. crassum'' resemble tapirs, especially the mountain tapir

The mountain tapir, also known as the Andean tapir or woolly tapir (''Tapirus pinchaque''), is the smallest of the four widely recognized species of tapir. It is found only in certain portions of the Andean Mountain Range in northwestern South A ...

(''Tapirus pinchaque''), in the build of their forelimbs. ''P. magnum'' has less slender radii and metacarpals compared to those of ''P. crassum'' and is therefore comparable to those of modern tapirs. ''P. medium'', along with ''Plagiolophus'', appear to be the most cursorial palaeotheres due to their elongated and gracile metacarpals. ''P. medium'' has a more unique foot morphology compared to other ''Palaeotherium'' species due to narrower and higher feet and longer metapodial bones. The cursorial adaptations of ''P. medium'' is further supported by the morphology of the humerus

The humerus (; : humeri) is a long bone in the arm that runs from the shoulder to the elbow. It connects the scapula and the two bones of the lower arm, the radius (bone), radius and ulna, and consists of three sections. The humeral upper extrem ...

. The middle metatarsal bone

The metatarsal bones or metatarsus (: metatarsi) are a group of five long bones in the midfoot, located between the tarsal bones (which form the heel and the ankle) and the phalanges ( toes). Lacking individual names, the metatarsal bones are ...

is larger and more robust than the others. The fourth toe of ''P. magnum'' appears slightly arched and is slightly longer than the second toe.

Footprints

Several types of tracks have been suggested to belong to ''Palaeotherium'', among them the

Several types of tracks have been suggested to belong to ''Palaeotherium'', among them the ichnogenus

An ichnotaxon (plural ichnotaxa) is "a taxon based on the fossilized work of an organism", i.e. the non-human equivalent of an artifact. ''Ichnotaxon'' comes from the Ancient Greek (''íchnos'') meaning "track" and English , itself derived from ...

'' Palaeotheriipus'' that was named by the palaeontologist Paul Ellenberger in 1980 based on tracks from lacustrine limestone

Limestone is a type of carbonate rock, carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material Lime (material), lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different Polymorphism (materials science) ...

s in the department of Gard

Gard () is a department in Southern France, located in the region of Occitanie. It had a population of 748,437 as of 2019; The ichnogenus is diagnosed as a very short and tridactyl footprint in which the outer digits (II and IV) are shallow the middle digit (digit III) is more deeply impressed. It differs from another palaeothere ichnogenus, '' Plagiolophustipus'', which was suggested to have been made by ''Plagiolophus'', by the presence of smaller and broader digit impressions. '' Lophiopus'', possibly produced by ''Lophiodon'', differs by smaller digit impressions that are more widely splaced, while '' Rhinoceripeda'', attributed to the Rhinocerotidae, is an oval-shaped footprint with three or five digits. ''Palaeotheriipus'' is known from both France and Iran, whereas ''Plagiolophustipus'' is currently known from Spain.

Two ichnospecies of ''Palaeotheriipus'' have been named. The type ichnospecies is ''Palaeotheriipus similimedius'' and based on the French material. These footprints are wider () than long (), with fingers that diverge widely from each other at angles of at least 50°. The hoof of finger III appears to be wider than those of the outer toes. Ellenberger suggested that the ichnospecies most closely corresponds with either ''P. medium euzetense'' or ''P. medium perrealense''. A second ichnospecies, ''P. sarjeanti'', was described from eastern Iran and opens the possibility that palaeotheres could have extended in geographical range to the region by the middle to late Eocene. It was named in honor of the ichnologist William A. S. Sarjeant and is diagnosed as showing a relatively round middle digit that is broader and longer than the outer digits. The manus is less elongated than the pes. Additional footprints from the d'Apt-Forcalquier basin in France, dated to the middle Eocene and described by G. Bessonat et al. in 1969, are recorded to be larger than the footprints of ''P. similimedius''. They have been suggested to be produced by the species ''P. magnum''.

''Palaeotherium'' includes species of various sizes that range in skull base length from . The length of the tooth row from P2 to M3 ranges from in the smallest species, ''P. lautricense'', to in the largest species, ''P. giganteum''. ''P. magnum'', which was previously considered the largest species, is close to ''P. giganteum'' in size with one tooth row measuring . ''P. medium'' is estimated to be the size of a subadult

''Palaeotherium'' includes species of various sizes that range in skull base length from . The length of the tooth row from P2 to M3 ranges from in the smallest species, ''P. lautricense'', to in the largest species, ''P. giganteum''. ''P. magnum'', which was previously considered the largest species, is close to ''P. giganteum'' in size with one tooth row measuring . ''P. medium'' is estimated to be the size of a subadult

For much of the Eocene, a hothouse climate with humid, tropical environments with consistently high precipitations prevailed. Modern mammalian orders including the Perissodactyla, Artiodactyla, and

For much of the Eocene, a hothouse climate with humid, tropical environments with consistently high precipitations prevailed. Modern mammalian orders including the Perissodactyla, Artiodactyla, and  ''Palaeotherium'' made its first appearance with the species ''P. eocaenum'' in the MP13 unit. By then, it would have coexisted with perissodactyls (Palaeotheriidae, Lophiodontidae, and Hyrachyidae), non-endemic artiodactyls ( Dichobunidae and Tapirulidae), endemic European artiodactyls ( Choeropotamidae (possibly polyphyletic, however), Cebochoeridae, and Anoplotheriidae), and primates (

''Palaeotherium'' made its first appearance with the species ''P. eocaenum'' in the MP13 unit. By then, it would have coexisted with perissodactyls (Palaeotheriidae, Lophiodontidae, and Hyrachyidae), non-endemic artiodactyls ( Dichobunidae and Tapirulidae), endemic European artiodactyls ( Choeropotamidae (possibly polyphyletic, however), Cebochoeridae, and Anoplotheriidae), and primates (

The late Eocene MP17 unit marks the first appearances of several species of ''Palaeotherium'', namely ''P. magnum'', ''P. medium'', ''P. curtum'', ''P. crassum'', ''P. duvali'', and ''P. muehlbergi''. The temporal range of ''P. siderolithicum'', first known in MP16, continued up to MP19, and ''P. renevieri'' made its first and only appearance in MP19. Some other species extended in temporal range up to MP19 (''P. duvali'', ''P. crassum'') while some others lasted up to MP20 (''P. magnum'', ''P. curtum'', ''P. muehlbergi''). By the late Eocene, the latest species of ''Palaeotherium'' were widespread throughout western Europe, including what is now Portugal, Spain, France, Switzerland, Germany, and the United Kingdom. Additionally, the genus is known from as far east as the Thrace Basin of Greece in the eastern European region in the middle to late Eocene. The faunas of eastern Europe vastly differed from those of western Europe despite the presence of ''Palaeotherium'' in both regions. It is possible that ''Palaeotherium'' was distributed as far east as eastern Iran, depending on whether the footprints are attributable to it. The presence of ''Palaeotherium'' in eastern Europe suggests periodic connectivity between Balkanatolia and other Eurasian regions.

Within the late Eocene, the Cainotheriidae and derived members of the Anoplotheriinae both made their first appearances by MP18. Also, several migrant mammal groups had reached western Europe by MP17a-MP18, namely the Anthracotheriidae, Hyaenodontinae, and Amphicyonidae. In addition to snakes, frogs, and salamandrids, rich assemblage of lizards are known in western Europe as well from MP16–MP20, representing the

The late Eocene MP17 unit marks the first appearances of several species of ''Palaeotherium'', namely ''P. magnum'', ''P. medium'', ''P. curtum'', ''P. crassum'', ''P. duvali'', and ''P. muehlbergi''. The temporal range of ''P. siderolithicum'', first known in MP16, continued up to MP19, and ''P. renevieri'' made its first and only appearance in MP19. Some other species extended in temporal range up to MP19 (''P. duvali'', ''P. crassum'') while some others lasted up to MP20 (''P. magnum'', ''P. curtum'', ''P. muehlbergi''). By the late Eocene, the latest species of ''Palaeotherium'' were widespread throughout western Europe, including what is now Portugal, Spain, France, Switzerland, Germany, and the United Kingdom. Additionally, the genus is known from as far east as the Thrace Basin of Greece in the eastern European region in the middle to late Eocene. The faunas of eastern Europe vastly differed from those of western Europe despite the presence of ''Palaeotherium'' in both regions. It is possible that ''Palaeotherium'' was distributed as far east as eastern Iran, depending on whether the footprints are attributable to it. The presence of ''Palaeotherium'' in eastern Europe suggests periodic connectivity between Balkanatolia and other Eurasian regions.

Within the late Eocene, the Cainotheriidae and derived members of the Anoplotheriinae both made their first appearances by MP18. Also, several migrant mammal groups had reached western Europe by MP17a-MP18, namely the Anthracotheriidae, Hyaenodontinae, and Amphicyonidae. In addition to snakes, frogs, and salamandrids, rich assemblage of lizards are known in western Europe as well from MP16–MP20, representing the

The Grande Coupure event during the latest Eocene to earliest Oligocene (MP20-MP21) is one of the largest and most abrupt faunal turnovers in the Cenozoic of Western Europe and coincident with

The Grande Coupure event during the latest Eocene to earliest Oligocene (MP20-MP21) is one of the largest and most abrupt faunal turnovers in the Cenozoic of Western Europe and coincident with

Size

''Palaeotherium'' includes species of various sizes that range in skull base length from . The length of the tooth row from P2 to M3 ranges from in the smallest species, ''P. lautricense'', to in the largest species, ''P. giganteum''. ''P. magnum'', which was previously considered the largest species, is close to ''P. giganteum'' in size with one tooth row measuring . ''P. medium'' is estimated to be the size of a subadult

''Palaeotherium'' includes species of various sizes that range in skull base length from . The length of the tooth row from P2 to M3 ranges from in the smallest species, ''P. lautricense'', to in the largest species, ''P. giganteum''. ''P. magnum'', which was previously considered the largest species, is close to ''P. giganteum'' in size with one tooth row measuring . ''P. medium'' is estimated to be the size of a subadult South American tapir

The South American tapir (''Tapirus terrestris''), also commonly called the Brazilian tapir (from the Tupi ), the Amazonian tapir, the maned tapir, the lowland tapir, (Brazilian Portuguese), and ''la sachavaca'' (literally "bushcow", in mixed ...

(''Tapirus terrestris''), larger than the roe deer-sized ''Plagiolophus minor''. The ''P. magnum'' Mormoiron skeleton demonstrates that individuals could have reached approximately in shoulder height and in length. Additionally, its head and neck together measure , and its forelimb (humerus to hoof) also measures in length.

In 2015, Remy calculated the body mass of several Eocene European perissodactyl species based on a formula originally proposed by Christine M. Janis in 1990. He estimated that the small species ''P. lautricense'' could have weighed just . ''P. siderolithicum'' could have had an average weight of around . ''P.'' aff. ''ruetimeyeri'' could have had a larger body mass of while ''P. pomeli'' was estimated at . ''P. castrense robiacense'' was estimated to be much heavier, at . According to Piere Perales-Gogenola et al. in 2022, the largest species ''P. giganteum'' could have had a body weight over . MacLaren and Naewelaerts proposed a somewhat lower weight estimate of for the large species ''P. magnum''.

Palaeobiology

''Palaeotherium'' species vary substantially in size, morphology, and build. The skeletons of ''P. magnum'', ''P. curtum'', and ''P. crassum'' were relatively robust, while that of ''P. medium'' was more gracile, suggesting increasedcursoriality

A cursorial organism is one that is adapted specifically to run. An animal can be considered cursorial if it has the ability to run fast (e.g. cheetah) or if it can keep a constant speed for a long distance (high endurance). "Cursorial" is often ...

. The evolutionary history of palaeotheres might have emphasized the sense of smell rather than sight or hearing, evident by the smaller orbits and the apparent lack of a derived auditory system. A well-developed sense of smell could have allowed palaeotheres to keep track of their herds, implying gregarious

Sociality is the degree to which individuals in an animal population tend to associate in social groups (gregariousness) and form cooperative societies.

Sociality is a survival response to evolutionary pressures. For example, when a mother was ...

behaviours. The wide diversity of palaeothere forelimb morphologies attests to different degrees of cursoriality in separate species. They generally had smaller hindlimbs compared to forelimbs, suggesting less tendencies towards cursoriality due to being adapted to closed and stable environments. In 2000, Giuseppe Santi proposed that ''Palaeotherium'' could have been able to stand on its hind legs to reach high plants. ''P. magnum'' may have been able to browse on plants at over when quadrupedal; when on its hind legs, it could have reached up to or even in height. However, Jerry J. Hooker argued that there is no evidence for such facultative bipedalism in ''P. magnum'' unlike in the contemporary artiodactyl

Artiodactyls are placental mammals belonging to the order Artiodactyla ( , ). Typically, they are ungulates which bear weight equally on two (an even number) of their five toes (the third and fourth, often in the form of a hoof). The other t ...

'' Anoplotherium''. The long neck of ''P. magnum'' suggests that it might have browsed on higher plants and/or drank water from below. ''Palaeotherium'' was amongst the largest mammals to inhabit Europe during the middle to late Eocene, with only a few contemporary mammalian groups such as lophiodonts, anoplotheriids, and other palaeotheres reaching similar or larger body sizes.

According to Sandra Engels in a conference paper, both ''Palaeotherium'' and ''Plagiolophus'' have dentitions capable of processing harder items such as hard fruits, while their predecessors, such as ''Hyracotherium'' and ''Propalaeotherium'', were adapted to softer food. Unlike in equids and basal equoids, the molars of later palaeotheres serve dual purposes of shearing food on the buccal side followed by crushing it on the lingual side, an adaptation for broader herbivorous diets. The two derived genera have brachyodont (low-crowned) dentition, suggesting that both genera were mostly folivorous (leaf-eating) and did not have frugivorous (fruit-eating) tendencies, evident by the lower amounts of rounded cusps on their molars. While both genera may have incorporated some fruit into their diets, the higher lingual tooth wear

Tooth wear refers to loss of tooth substance by means other than dental caries. Tooth wear is a very common condition that occurs in approximately 97% of the population. This is a normal physiological process occurring throughout life; but with i ...

in ''Plagiolophus'' indicates it ate more fruit than ''Palaeotherium''. Because of their likely tendencies to browse on higher plants, evident by their long necks and the woodland environments they inhabited, it is unlikely that minerals, usually consumed from grazing on ground plants, significantly affected the tooth wear of either of these genera. The tooth wear in both genera could have been the result of chewing on fruit seeds. It is likely that ''Palaeotherium'' ate softer food such as younger leaves and fleshy fruit that may have had hard seeds while ''Plagiolophus'' leaned towards consuming tough food such as older leaves and harder fruit. The interpretation that ''Palaeotherium'' consumed more leaf and woody material and less fruit compared to ''Plagiolophus'' is supported by the two having somewhat different chewing functions and ''Palaeotherium'' being more efficient in shearing food.

Palaeoecology

Middle Eocene

For much of the Eocene, a hothouse climate with humid, tropical environments with consistently high precipitations prevailed. Modern mammalian orders including the Perissodactyla, Artiodactyla, and

For much of the Eocene, a hothouse climate with humid, tropical environments with consistently high precipitations prevailed. Modern mammalian orders including the Perissodactyla, Artiodactyla, and Primates

Primates is an order of mammals, which is further divided into the strepsirrhines, which include lemurs, galagos, and lorisids; and the haplorhines, which include tarsiers and simians ( monkeys and apes). Primates arose 74–63 ...

(or the suborder Euprimates) appeared already by the early Eocene, diversifying rapidly and developing dentitions specialized for folivory. The omnivorous

An omnivore () is an animal that regularly consumes significant quantities of both plant and animal matter. Obtaining energy and nutrients from plant and animal matter, omnivores digest carbohydrates, protein, fat, and fiber, and metabolize ...

forms mostly either switched to folivorous diets or went extinct by the middle Eocene (47–37 million years ago) along with the archaic " condylarths". By the late Eocene (approx. 37–33 mya), most of the ungulate form dentitions shifted from bunodont

The molars or molar teeth are large, flat teeth at the back of the mouth. They are more developed in mammals. They are used primarily to grind food during chewing. The name ''molar'' derives from Latin, ''molaris dens'', meaning "millstone tooth ...

(or rounded) cusps to cutting ridges (i.e. lophs) for folivorous diets.

Land connections between western Europe and North America were interrupted around 53 Ma. From the early Eocene up until the Grande Coupure

Grande means "large" or "great" in many of the Romance languages. It may also refer to:

Places

* Grande, Germany, a municipality in Germany

* Grande Communications, a telecommunications firm based in Texas

* Grande-Rivière (disambiguation)

* Ar ...

extinction event (56–33.9 mya), western Eurasia was separated into three landmasses: western Europe (an archipelago), Balkanatolia (in-between the Paratethys Sea of the north and the Neotethys Ocean of the south), and eastern Eurasia. The Holarctic

The Holarctic realm is a biogeographic realm that comprises the majority of habitats found throughout the continents in the Northern Hemisphere. It corresponds to the floristic Boreal Kingdom. It includes both the Nearctic zoogeographical reg ...

mammalian faunas of western Europe were therefore mostly isolated from other landmasses including Greenland, Africa, and eastern Eurasia, allowing for endemism to develop. Therefore, the European mammals of the late Eocene (MP17–MP20 of the Mammal Palaeogene zones) were mostly descendants of endemic middle Eocene groups.

''Palaeotherium'' made its first appearance with the species ''P. eocaenum'' in the MP13 unit. By then, it would have coexisted with perissodactyls (Palaeotheriidae, Lophiodontidae, and Hyrachyidae), non-endemic artiodactyls ( Dichobunidae and Tapirulidae), endemic European artiodactyls ( Choeropotamidae (possibly polyphyletic, however), Cebochoeridae, and Anoplotheriidae), and primates (

''Palaeotherium'' made its first appearance with the species ''P. eocaenum'' in the MP13 unit. By then, it would have coexisted with perissodactyls (Palaeotheriidae, Lophiodontidae, and Hyrachyidae), non-endemic artiodactyls ( Dichobunidae and Tapirulidae), endemic European artiodactyls ( Choeropotamidae (possibly polyphyletic, however), Cebochoeridae, and Anoplotheriidae), and primates (Adapidae

Adapidae is a family of extinct primates that primarily radiated during the Eocene epoch between about 55 and 34 million years ago.

Adapid systematics and evolutionary relationships are controversial, but there is fairly good evidence from the ...

). Both the Amphimerycidae and Xiphodontidae made their first appearances by the level MP14. The stratigraphic ranges of the early species of ''Palaeotherium'' also overlapped with metatheria

Metatheria is a mammalian clade that includes all mammals more closely related to marsupials than to placentals. First proposed by Thomas Henry Huxley in 1880, it is a more inclusive group than the marsupials; it contains all marsupials as wel ...

ns (Herpetotheriidae

Herpetotheriidae is an extinct family of metatherians, closely related to marsupials. Species of this family are generally reconstructed as terrestrial, and are considered morphologically similar to modern opossums. They are suggested to have b ...

), cimolesta

Cimolesta is an extinct order of non-placental eutherian mammals. Cimolestans had a wide variety of body shapes, dentition and lifestyles, though the majority of them were small to medium-sized general mammals that bore superficial resemblances t ...

ns ( Pantolestidae, Paroxyclaenidae), rodents ( Ischyromyidae, Theridomyoidea, Gliridae), eulipotyphla

Eulipotyphla (, from '' eu-'' + '' Lipotyphla'', meaning truly lacking blind gut; sometimes called true insectivores) is an order of mammals comprising the Erinaceidae ( hedgehogs and gymnures); Solenodontidae (solenodons); Talpidae ( mole ...

ns, bats, apatotherians, carnivoraformes ( Miacidae), and hyaenodonts (Hyainailourinae

Hyainailourinae ("hyena-like Felidae, cats") is a Paraphyly, paraphyletic subfamily of Hyaenodonta, hyaenodonts from extinct paraphyletic family Hyainailouridae. They arose during the Bartonian, Middle Eocene in Africa, and persisted well into th ...

, Proviverrinae). Other MP13-MP14 sites have also yielded fossils of turtles and crocodylomorphs, and MP13 sites are stratigraphically the latest to have yielded remains of the bird clades Gastornithidae and Palaeognathae

Palaeognathae (; ) is an infraclass of birds, called paleognaths or palaeognaths, within the class Aves of the clade Archosauria. It is one of the two extant taxon, extant infraclasses of birds, the other being Neognathae, both of which form Neo ...

.