Oklahoma City Bomber on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Timothy James McVeigh (April 23, 1968 – June 11, 2001) was an American

Working at a lakeside campground near McVeigh's old Army post, he and Nichols constructed an

Working at a lakeside campground near McVeigh's old Army post, he and Nichols constructed an

McVeigh's biographers, Lou Michel and Dan Herbeck, spoke with McVeigh in interviews totaling 75 hours. He said about the victims: During an interview in 2000 with

By tracing the

By tracing the  On August 10, 1995, McVeigh was indicted on 11 federal counts, including conspiracy to use a weapon of mass destruction, use of a weapon of mass destruction, destruction with the use of explosives, and eight counts of first degree murder for the deaths of law enforcement officers. On February 20, 1996, the Court granted a

On August 10, 1995, McVeigh was indicted on 11 federal counts, including conspiracy to use a weapon of mass destruction, use of a weapon of mass destruction, destruction with the use of explosives, and eight counts of first degree murder for the deaths of law enforcement officers. On February 20, 1996, the Court granted a

McVeigh's death sentence was delayed pending an appeal. One of his appeals for , taken to the

McVeigh's death sentence was delayed pending an appeal. One of his appeals for , taken to the  McVeigh chose

McVeigh chose

Timothy McVeigh

"A Look Back in TIME: Interview with Timothy McVeigh"

March 30, 1996. Retrieved October 19, 2010. During his childhood, he and his father attended

"McVeigh faces day of reckoning: Special report: Timothy McVeigh,"

, ''

"Bad Day Dawning"

in "Criminals and Methods: Timothy McVeigh" at

Timothy McVeigh's April 27, 2001 letter to reporter Rita Cosby

xplains why he bombed the Murrah Federal Building (posted on independence.net)

at

The Timothy McVeigh Story: The Oklahoma Bomber

at

Voices of Oklahoma interview with Stephen Jones.

First person interview conducted on January 27, 2010, with Stephen Jones, lawyer for Timothy McVeigh.

ritique of Timothy McVeigh by fellow inmate Unabomber

– ''

domestic terrorist

Domestic terrorism or homegrown terrorism is a form of terrorism in which victims "within a country are targeted by a perpetrator with the same citizenship" as the victims.Gary M. Jackson, ''Predicting Malicious Behavior: Tools and Techniques ...

responsible for the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing

The Oklahoma City bombing was a domestic terrorist truck bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, United States, on April 19, 1995. Perpetrated by two anti-government extremists, Timothy McVeigh and Terry N ...

that killed 168 people, 19 of whom were children, injured more than 680 others, and destroyed one-third of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building

The Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building was a United States federal government complex located at 200 N.W. 5th Street in downtown Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. On April 19, 1995, at 9:02 a.m. the building was the target of the Oklahoma City bombing ...

. The bombing was the deadliest act of terrorism in the United States

In the United States, a common definition of terrorism is the systematic or threatened use of violence in order to create a general climate of fear to intimidate a population or government and thereby effect political, religious, or ideolog ...

prior to the September 11 attacks

The September 11 attacks, commonly known as 9/11, were four coordinated suicide terrorist attacks carried out by al-Qaeda against the United States on Tuesday, September 11, 2001. That morning, nineteen terrorists hijacked four commercia ...

. It remains the deadliest act of domestic terrorism

Domestic terrorism or homegrown terrorism is a form of terrorism in which victims "within a country are targeted by a perpetrator with the same citizenship" as the victims.Gary M. Jackson, ''Predicting Malicious Behavior: Tools and Techniques ...

in U.S. history.

A Gulf War

The Gulf War was a 1990–1991 armed campaign waged by a 35-country military coalition in response to the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. Spearheaded by the United States, the coalition's efforts against Iraq were carried out in two key phases: ...

veteran, McVeigh sought revenge against the federal government for the 1993 Waco siege

The Waco siege, also known as the Waco massacre, was the law enforcement siege of the compound that belonged to the religious sect Branch Davidians. It was carried out by the U.S. federal government, Texas state law enforcement, and the U.S. mi ...

as well as the 1992 Ruby Ridge

Ruby Ridge was the site of an eleven-day siege in 1992 in Boundary County, Idaho, near Naples. It began on August 21, when deputies of the United States Marshals Service (USMS) initiated action to apprehend and arrest Randy Weaver under a bench ...

incident and American foreign policy. He hoped to inspire a revolution against the federal government, and defended the bombing as a legitimate tactic against what he saw as a tyrannical government. He was arrested shortly after the bombing and indicted on 160 state offenses and 11 federal offenses, including the use of a weapon of mass destruction

A weapon of mass destruction (WMD) is a chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, or any other weapon that can kill and bring significant harm to numerous individuals or cause great damage to artificial structures (e.g., buildings), natura ...

. He was found guilty on all counts in 1997 and sentenced to death.

McVeigh was executed by lethal injection on June 11, 2001, at the Federal Correctional Complex in Terre Haute, Indiana. His execution

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the State (polity), state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to ...

, which took place just over six years after the offense, was carried out in a considerably shorter time than for most inmates awaiting execution.

Early life

McVeigh was born on April 23, 1968, in Lockport,New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, the only son and the second of three children of his Irish American

, image = Irish ancestry in the USA 2018; Where Irish eyes are Smiling.png

, image_caption = Irish Americans, % of population by state

, caption = Notable Irish Americans

, population =

36,115,472 (10.9%) alone ...

parents, Mildred "Mickey" Noreen (''née'' Hill) and William McVeigh. In 1866, McVeigh's great-great-grandfather Edward McVeigh emigrated from Ireland and settled in Niagara County

Niagara County is in the U.S. state of New York. As of the 2020 census, the population was 212,666. The county seat is Lockport. The county name is from the Iroquois word ''Onguiaahra''; meaning ''the strait'' or ''thunder of waters''.

Niag ...

. After their parents divorced when McVeigh was ten years old, he was raised by his father in Pendleton, New York

Pendleton is a town on the southern edge of Niagara County, New York, United States. It is east of the city of Niagara Falls and southwest of the city of Lockport. The population was 6,397 at the 2010 census.

History

The town of Pendleton wa ...

.

McVeigh claimed to have been a target of bullying

Bullying is the use of force, coercion, hurtful teasing or threat, to abuse, aggressively dominate or intimidate. The behavior is often repeated and habitual. One essential prerequisite is the perception (by the bully or by others) of an imba ...

at school, and he took refuge in a fantasy world where he imagined retaliating against the bullies. At the end of his life, he stated his belief that the United States government

The federal government of the United States (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the national government of the United States, a federal republic located primarily in North America, composed of 50 states, a city within a fede ...

is the ultimate bully.

Most who knew McVeigh remember him as being very shy and withdrawn, while a few described him as an outgoing and playful child who withdrew as an adolescent. He is said to have had only one girlfriend as an adolescent; he later told journalists that he did not have any idea how to impress girls.

While in high school McVeigh became interested in computers, and hacked into government computer systems on his Commodore 64

The Commodore 64, also known as the C64, is an 8-bit home computer introduced in January 1982 by Commodore International (first shown at the Consumer Electronics Show, January 7–10, 1982, in Las Vegas). It has been listed in the Guinness ...

under the handle The Wanderer, taken from the song by Dion (DiMucci). In his senior year he was named "most promising computer programmer" of Starpoint Central High School, as well as "Most Talkative" by his classmates as a joke as he did not speak much but had relatively poor grades until his 1986 graduation.

He was introduced to firearms by his grandfather. McVeigh told people of his wish to become a gun shop owner, and sometimes took firearms to school to impress his classmates. He became intensely interested in gun rights

The right to keep and bear arms (often referred to as the right to bear arms) is a right for people to possess weapons (arms) for the preservation of life, liberty, and property. The purpose of gun rights is for self-defense, including securi ...

as well as the Second Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Second Amendment (Amendment II) to the United States Constitution protects the Right to keep and bear arms in the United States, right to keep and bear arms. It was ratified on December 15, 1791, along with nine other articles of the Un ...

after he graduated from high school, and read magazines such as '' Soldier of Fortune''. He briefly attended Bryant & Stratton College before dropping out. After dropping out of college, McVeigh worked as an armored car guard and was noted by co-workers as being obsessed with guns. One co-worker recalled an instance when McVeigh came to work "looking like Pancho Villa

Francisco "Pancho" Villa (,"Villa"

''Collins English Dictionary''. ; ;

" as he was wearing ''Collins English Dictionary''. ; ;

bandolier

A bandolier or a bandoleer is a pocketed belt for holding either individual bullets, or belts of ammunition. It is usually slung sash-style over the shoulder and chest, with the ammunition pockets across the midriff and chest. Though functio ...

s.

Military career

In May 1988, at the age of 20, McVeigh enlisted in the United States Army and attended Basic Training and Advanced Individual Training at theU.S. Army Infantry School

The United States Army Infantry School is a school located at Fort Benning, Georgia that is dedicated to training infantrymen for service in the United States Army.

Organization

The school is made up of the following components:

* 197th Infantr ...

at Fort Benning

Fort Benning is a United States Army post near Columbus, Georgia, adjacent to the Alabama–Georgia border. Fort Benning supports more than 120,000 active-duty military, family members, reserve component soldiers, retirees and civilian employees ...

, Georgia. While in the military, McVeigh used much of his spare time to read about firearms, sniper tactics, and explosives. McVeigh was reprimanded by the military for purchasing a "White Power

White pride and white power are expressions primarily used by white separatist, white nationalist, fascist, neo-Nazi and white supremacist organizations in order to signal racist or racialist viewpoints. It is also a slogan used by the prominen ...

" T-shirt at a Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and ...

rally where they were objecting to black servicemen who wore " Black Power" T-shirts around a military installation (primarily Army). His future co-conspirator Terry Nichols

Terry Lynn Nichols (born April 1, 1955) is an American domestic terrorist who was convicted of being an accomplice in the Oklahoma City bombing. Prior to his incarceration, he held a variety of short-term jobs, working as a farmer, grain elevato ...

was his platoon guide. He and Nichols quickly got along with their similar backgrounds as well as their views in gun collecting and survivalism. The two were later stationed together at Fort Riley in Junction City, Kansas, where they met and became friends with their future accomplice, Michael Fortier.

McVeigh was a top-scoring gunner with the 25mm cannon of the Bradley Fighting Vehicle

The Bradley Fighting Vehicle (BFV) is a tracked armoured fighting vehicle platform of the United States developed by FMC Corporation and manufactured by BAE Systems Land & Armaments, formerly United Defense. It is named after U.S. General Om ...

s used by the 1st Infantry Division and was promoted to sergeant. After being promoted, McVeigh earned a reputation for assigning undesirable work to black servicemen and using racial slurs. He was stationed at Fort Riley

Fort Riley is a United States Army installation located in North Central Kansas, on the Kansas River, also known as the Kaw, between Junction City and Manhattan. The Fort Riley Military Reservation covers 101,733 acres (41,170 ha) in Gear ...

, Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the ...

, before being deployed on Operation Desert Storm

Operation or Operations may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* ''Operation'' (game), a battery-operated board game that challenges dexterity

* Operation (music), a term used in musical set theory

* ''Operations'' (magazine), Multi-Man ...

.

In an interview before his execution, McVeigh said that he hit an Iraqi tank more than 500 yards away on his first day in the war and then the Iraqis surrendered. He also decapitated an Iraqi soldier with cannon fire from 1,100 yards away. He said he was later shocked to see carnage on the road while leaving Kuwait City

Kuwait City ( ar, مدينة الكويت) is the capital and largest city of Kuwait. Located at the heart of the country on the south shore of Kuwait Bay on the Persian Gulf, it is the political, cultural and economical centre of the emirate, ...

after U.S. troops routed the Iraqi Army. McVeigh received several service awards, including the Bronze Star Medal

The Bronze Star Medal (BSM) is a United States Armed Forces decoration awarded to members of the United States Armed Forces for either heroic achievement, heroic service, meritorious achievement, or meritorious service in a combat zone.

Wh ...

National Defense Service Medal

The National Defense Service Medal (NDSM) is a service award of the United States Armed Forces established by President Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1953. It is awarded to every member of the US Armed Forces who has served during any one of four sp ...

, Southwest Asia Service Medal

The Southwest Asia Service Medal (SASM or SWASM) is a military award of the United States Armed Forces which was created by order of President George H.W. Bush on March 12, 1991. The award is intended to recognize those military service members ...

, Army Service Ribbon

The Army Service Ribbon (ASR) is a military award of the United States Army that was established by the Secretary of the Army on 10 April 1981 as announced in Department of the Army General Order 15, dated 10 October 1990.

History

Effective 1 Au ...

, and the Kuwaiti Liberation Medal.

McVeigh aspired to join the United States Army Special Forces

The United States Army Special Forces (SF), colloquially known as the "Green Berets" due to their distinctive service Berets of the United States Army, headgear, are a special operations special operations force, force of the United States Ar ...

(SF). After returning from the Gulf War

The Gulf War was a 1990–1991 armed campaign waged by a 35-country military coalition in response to the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. Spearheaded by the United States, the coalition's efforts against Iraq were carried out in two key phases: ...

, he entered the selection program, but withdrew on the second day of the 21-day assessment and selection course for the Special Forces, telling other recruits that he had injured an ankle. However, in a letter to his superiors, McVeigh wrote that he was not "physically ready". McVeigh decided to leave the Army and was honorably discharged

A military discharge is given when a member of the armed forces is released from their obligation to serve. Each country's military has different types of discharge. They are generally based on whether the persons completed their training and the ...

in 1991.

Post-military life

McVeigh wrote letters to local newspapers complaining about taxes. In 1992, he wrote: McVeigh also wrote to RepresentativeJohn J. LaFalce

John Joseph LaFalce (born October 6, 1939) is an American politician who served as a Congressman from the state of New York from 1975 to 2003. He retired in 2002 after his district was merged with that of a fellow Democrat.

LaFalce was first e ...

( D–New York), complaining about the arrest of a woman for carrying mace:

McVeigh later moved in with Nichols to Nichols’ brother James’ farm around Decker, Michigan. While visiting friends, McVeigh reportedly complained that the Army had implanted a microchip

An integrated circuit or monolithic integrated circuit (also referred to as an IC, a chip, or a microchip) is a set of electronic circuits on one small flat piece (or "chip") of semiconductor material, usually silicon. Large numbers of tiny ...

into his buttocks so that the government could keep track of him. McVeigh worked long hours in a dead-end job

A dead-end job is a job where there is little or no chance of career development and advancement into a better position. If an individual requires further education to progress within their firm that is difficult to obtain for any reason, this can ...

and felt that he did not have a home. He sought romance, but his advances were rejected by a co-worker and he felt nervous around women. He believed that he brought too much pain to his loved ones. He grew angry and frustrated at his difficulties in finding a girlfriend. He took up obsessive gambling. Unable to pay gambling debts, he took a cash advance and then defaulted on his repayments. He began looking for a state with low taxes so that he could live without heavy government regulation or high taxes. He became enraged when the government told him that he had been overpaid $1,058 while in the Army and he had to pay back the money. He wrote an angry letter to the government, saying:

McVeigh introduced his sister to anti-government literature, but his father had little interest in these views. He moved out of his father's house and into an apartment that had no telephone. This made it impossible for his employer to contact him for overtime assignments. He quit the National Rifle Association

The National Rifle Association of America (NRA) is a gun rights advocacy group based in the United States. Founded in 1871 to advance rifle marksmanship, the modern NRA has become a prominent Gun politics in the United States, gun rights ...

(NRA), believing that it was too weak on gun rights.

1993 Waco siege and gun shows

In 1993, McVeigh drove toWaco, Texas

Waco ( ) is the county seat of McLennan County, Texas, United States. It is situated along the Brazos River and I-35, halfway between Dallas and Austin. The city had a 2020 population of 138,486, making it the 22nd-most populous city in the ...

, during the Waco siege

The Waco siege, also known as the Waco massacre, was the law enforcement siege of the compound that belonged to the religious sect Branch Davidians. It was carried out by the U.S. federal government, Texas state law enforcement, and the U.S. mi ...

to show his support. At the scene, he distributed pro-gun rights

The right to keep and bear arms (often referred to as the right to bear arms) is a right for people to possess weapons (arms) for the preservation of life, liberty, and property. The purpose of gun rights is for self-defense, including securi ...

literature and bumper stickers bearing slogans such as, "When guns are outlawed, I will become an outlaw." He told a student reporter:

For the five months following the Waco siege, McVeigh worked at gun show

In the United States, a gun show is an event where promoters generally rent large public venues and then rent tables for display areas for dealers of guns and related items, and charge admission for buyers. The majority of guns for sale at gun s ...

s and handed out free cards printed with Lon Horiuchi

Lon Tomohisa Horiuchi (born June 9, 1954) is an American former Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) Hostage Rescue Team (HRT) sniper and former United States Army officer who was involved in the 1992 Ruby Ridge standoff and 1993 Waco siege. I ...

's name and address, "in the hope that somebody in the Patriot movement

In the United States, the patriot movement is a term which is used to describe a conglomeration of non-unified right-wing populist, nationalist political movements, most notably far-right armed militias, sovereign citizens, and tax protester ...

would assassinate the sharpshooter." Horiuchi is an FBI sniper and some of his official actions have drawn controversy, specifically his shooting and killing of Randy Weaver

Randall Claude Weaver (January 3, 1948 – May 11, 2022) was an American survivalist, former Iowa factory worker, and self-proclaimed white separatist. He was a central actor in the 1992 Ruby Ridge standoff at his cabin near Naples, Idaho, th ...

's wife while she held an infant child. McVeigh wrote hate mail

Hate mail (as electronic, posted, or otherwise) is a form of harassment, usually consisting of invective and potentially intimidating or threatening comments towards the recipient. Hate mail often contains exceptionally abusive, foul or otherwise ...

to Horiuchi, suggesting that "what goes around, comes around". McVeigh later considered putting aside his plan to target the Murrah Building to target Horiuchi or a member of his family instead.

McVeigh became a fixture on the gun show circuit, traveling to forty states and visiting about eighty gun shows. He found that the further west he went, the more anti-government sentiment he encountered, at least until he got to what he called "The People's Socialist Republic of California." McVeigh sold survival items and copies of ''The Turner Diaries

''The Turner Diaries'' is a 1978 novel by William Luther Pierce, published under the pseudonym Andrew Macdonald. It depicts a violent revolution in the United States which leads to the overthrow of the federal government, a nuclear war, and, ...

''. One author said:

Arizona with Fortier

McVeigh had a road atlas with hand-drawn designations of the most likely places for nuclear attacks and considered buying property inSeligman, Arizona

Seligman ( yuf-x-hav, Thavgyalyal) is a census-designated place (CDP) on the northern border of Yavapai County, in northwestern Arizona, United States. The population was 456 at the 2000 census.

Geography

Seligman is located at (35.328199, − ...

, which he determined to be in a "nuclear-free zone." He lived with Michael Fortier

Michael M. Fortier, (born January 10, 1962) is a Canadian financier, lawyer and former politician. A member of the Conservative Party, he served as Minister of Public Works and Government Services from 2006 to 2008, and Minister of Internati ...

in Kingman, Arizona

Kingman is a city in, and the county seat of, Mohave County, Arizona, United States. It is named after Lewis Kingman, an engineer for the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad. It is located southeast of Las Vegas, Nevada, and northwest of Arizona's ...

, and the two became so close that he served as best man

A groomsman or usher is one of the male attendants to the groom in a wedding ceremony and performs the first speech at the wedding. Usually, the groom selects close friends and relatives to serve as groomsmen, and it is considered an honor to be ...

at Fortier's wedding. McVeigh experimented with cannabis

''Cannabis'' () is a genus of flowering plants in the family Cannabaceae. The number of species within the genus is disputed. Three species may be recognized: ''Cannabis sativa'', '' C. indica'', and '' C. ruderalis''. Alternatively ...

and methamphetamine

Methamphetamine (contracted from ) is a potent central nervous system (CNS) stimulant that is mainly used as a recreational drug and less commonly as a second-line treatment for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and obesity. Methamph ...

after first researching their effects in an encyclopedia. He was never as interested in drugs as Fortier was, and one of the reasons they parted ways was that McVeigh grew tired of Fortier's drug habits.

With Nichols, Waco siege, and radicalization

In April 1993, McVeigh headed for a farm in Michigan where former roommateTerry Nichols

Terry Lynn Nichols (born April 1, 1955) is an American domestic terrorist who was convicted of being an accomplice in the Oklahoma City bombing. Prior to his incarceration, he held a variety of short-term jobs, working as a farmer, grain elevato ...

lived. In between watching coverage of the Waco siege on TV, Nichols and his brother began teaching McVeigh how to make explosives by combining household chemicals in plastic jugs. The destruction of the Waco compound enraged McVeigh and convinced him that it was time to take action. He was particularly angered by the government's use of CS gas

The compound 2-chlorobenzalmalononitrile (also called ''o''-chlorobenzylidene malononitrile; chemical formula: C10H5ClN2), a cyanocarbon, is the defining component of tear gas commonly referred to as CS gas, which is used as a riot control agent ...

on women and children; he had been exposed to the gas as part of his military training and was familiar with its effects. The disappearance of certain evidence, such as the bullet-riddled steel-reinforced front door to the complex, led him to suspect a cover-up.

McVeigh's anti-government rhetoric became more radical. He began to sell Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives

The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (BATFE), commonly referred to as the ATF, is a domestic law enforcement agency within the United States Department of Justice. Its responsibilities include the investigation and prevent ...

(ATF) hats riddled with bullet holes, and a flare gun that he said could shoot down an "ATF helicopter". He produced videos detailing the government's actions at Waco and handed out pamphlets with titles such as "U.S. Government Initiates Open Warfare Against American People" and "Waco Shootout Evokes Memory of Warsaw '43." He began changing his answering machine greeting every couple of weeks to various quotes by Patrick Henry

Patrick Henry (May 29, 1736June 6, 1799) was an American attorney, planter, politician and orator known for declaring to the Second Virginia Convention (1775): " Give me liberty, or give me death!" A Founding Father, he served as the first an ...

, such as "Give me liberty or give me death." He began experimenting with making pipe bomb

A pipe bomb is an improvised explosive device which uses a tightly sealed section of pipe (material), pipe filled with an explosive material. The containment provided by the pipe means that simple Explosive material#Low explosives, low explosi ...

s and other small explosive devices. The government imposed new firearms restrictions in 1994 which McVeigh believed threatened his livelihood.

McVeigh dissociated himself from his boyhood friend Steve Hodge by sending him a 23-page farewell letter. He proclaimed his devotion to the United States Declaration of Independence

The United States Declaration of Independence, formally The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen States of America, is the pronouncement and founding document adopted by the Second Continental Congress meeting at Pennsylvania State House ...

, explaining in detail what each sentence meant to him. McVeigh declared that:

McVeigh felt the need to personally reconnoiter sites of rumored conspiracies. He visited Area 51

Area 51 is the common name of a highly classified United States Air Force (USAF) facility within the Nevada Test and Training Range. A remote detachment administered by Edwards Air Force Base, the facility is officially called Homey Airport ...

in order to defy government restrictions on photography and went to Gulfport, Mississippi

Gulfport is the second-largest city in Mississippi after the state capital, Jackson. Along with Biloxi, Gulfport is the co-county seat of Harrison County and the larger of the two principal cities of the Gulfport-Biloxi, Mississippi Metropolitan ...

, to determine the veracity of rumors about United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and international security, security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be ...

operations. These turned out to be false; the Russian vehicles on the site were being configured for use in U.N.-sponsored humanitarian aid efforts. Around this time, McVeigh and Nichols began making bulk purchases of ammonium nitrate

Ammonium nitrate is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is a white crystalline salt consisting of ions of ammonium and nitrate. It is highly soluble in water and hygroscopic as a solid, although it does not form hydrates. It is ...

, an agricultural fertilizer

A fertilizer (American English) or fertiliser (British English; see spelling differences) is any material of natural or synthetic origin that is applied to soil or to plant tissues to supply plant nutrients. Fertilizers may be distinct from ...

, for resale to survivalists, since rumors were circulating that the government was preparing to ban it.

Plan against federal building or individuals

McVeigh told Fortier of his plans to blow up a federal building, but Fortier declined to participate. Fortier also told his wife about the plans. McVeigh composed two letters to theBureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms

The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (BATFE), commonly referred to as the ATF, is a domestic law enforcement agency within the United States Department of Justice. Its responsibilities include the investigation and preven ...

, the first titled "Constitutional Defenders" and the second "ATF Read." He denounced government officials as "fascist tyrants" and "storm troopers," and warned:

McVeigh also wrote a letter to recruit a customer named Steve Colbern:

McVeigh began announcing that he had progressed from the "propaganda" phase to the "action" phase. He wrote to his Michigan friend Gwenda Strider, "I have certain other 'militant' talents that are in short supply and greatly demanded."

McVeigh later said he considered "a campaign of individual assassination," with "eligible" targets including Attorney General Janet Reno

Janet Wood Reno (July 21, 1938 – November 7, 2016) was an American lawyer who served as the 78th United States attorney general. She held the position from 1993 to 2001, making her the second-longest serving attorney general, behind only Wi ...

, Judge Walter S. Smith Jr. of Federal District Court

The United States district courts are the trial courts of the U.S. federal judiciary. There is one district court for each federal judicial district, which each cover one U.S. state or, in some cases, a portion of a state. Each district cou ...

, who handled the Branch Davidian

The Branch Davidians (or the General Association of Branch Davidian Seventh-day Adventists) were an apocalyptic new religious movement founded in 1955 by Benjamin Roden. They regard themselves as a continuation of the General Association of ...

trial; and Lon Horiuchi

Lon Tomohisa Horiuchi (born June 9, 1954) is an American former Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) Hostage Rescue Team (HRT) sniper and former United States Army officer who was involved in the 1992 Ruby Ridge standoff and 1993 Waco siege. I ...

, a member of the FBI hostage-rescue team, who shot and killed Vicki Weaver in a standoff at a remote cabin at Ruby Ridge, Idaho

Ruby Ridge was the site of an eleven-day siege in 1992 in Boundary County, Idaho, near Naples. It began on August 21, when deputies of the United States Marshals Service (USMS) initiated action to apprehend and arrest Randy Weaver under a bench ...

, in 1992. He said he wanted Reno to accept "full responsibility in deed, not just words." Such an assassination seemed too difficult, and he decided that since federal agents had become soldiers, he should strike at them at their command centers. According to McVeigh's authorized biography, he decided that he could make the loudest statement by bombing a federal building. After the bombing, he was ambivalent about his act and the deaths he caused; as he said in letters to his hometown newspaper, he sometimes wished that he had carried out a series of assassinations against police and government officials instead.

Oklahoma City bombing

Working at a lakeside campground near McVeigh's old Army post, he and Nichols constructed an

Working at a lakeside campground near McVeigh's old Army post, he and Nichols constructed an ANFO

ANFO ( ) (or AN/FO, for ammonium nitrate/fuel oil) is a widely used bulk industrial explosive. It consists of 94% porous prilled ammonium nitrate (NH4NO3) (AN), which acts as the oxidizing agent and absorbent for the fuel, and 6% number 2 fue ...

explosive device

An explosive device is a device that relies on the exothermic reaction of an explosive material to provide a violent release of energy.

Applications of explosive devices include:

*Building implosion (demolition)

* Excavation

*Explosive forming

...

mounted in the back of a rented Ryder truck. The bomb consisted of about of ammonium nitrate and nitromethane

Nitromethane, sometimes shortened to simply "nitro", is an organic compound with the chemical formula . It is the simplest organic nitro compound. It is a polar liquid commonly used as a solvent in a variety of industrial applications such as in ...

.

On April 19, 1995, McVeigh drove the truck to the front of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building

The Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building was a United States federal government complex located at 200 N.W. 5th Street in downtown Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. On April 19, 1995, at 9:02 a.m. the building was the target of the Oklahoma City bombing ...

just as its offices opened for the day. Before arriving, he stopped to light a two-minute fuse. At 09:02, a large explosion destroyed the north half of the building. It killed 168 people, including 19 children in the day care center on the second floor, and injured 684 others.

McVeigh said that he had not known that there was a daycare center on the second floor, and that he might have chosen a different target if he had known about it. Nichols said that he and McVeigh did know about the daycare center in the building, and that they did not care.Global Terrorism DatabaseMcVeigh's biographers, Lou Michel and Dan Herbeck, spoke with McVeigh in interviews totaling 75 hours. He said about the victims: During an interview in 2000 with

Ed Bradley

Edward Rudolph Bradley Jr. (June 22, 1941 – November 9, 2006) was an American broadcast journalist and news anchor. He was best known for his reporting on ''60 Minutes'' and CBS News.

Bradley began his journalism career as a radio news repo ...

for television news magazine ''60 Minutes

''60 Minutes'' is an American television news magazine broadcast on the CBS television network. Debuting in 1968, the program was created by Don Hewitt and Bill Leonard, who chose to set it apart from other news programs by using a unique styl ...

'', Bradley asked McVeigh for his reaction to the deaths of the nineteen children. McVeigh said:

According to the Oklahoma City Memorial Institute for the Prevention of Terrorism (MIPT), more than 300 buildings in the city were damaged. More than 12,000 volunteers and rescue workers took part in the rescue, recovery and support operations following the bombing. In reference to theories that McVeigh had assistance from others, he responded with a well-known line from the film ''A Few Good Men

''A Few Good Men'' is a 1992 American legal drama film based on Aaron Sorkin's 1989 play. It was written by Sorkin, directed by Rob Reiner, and produced by Reiner, David Brown and Andrew Scheinman. It stars an ensemble cast including Tom C ...

'', "You can't handle the truth!" He added, "Because the truth is, I blew up the Murrah Building and isn't it kind of scary that one man could wreak this kind of hell?"

Arrest and trial

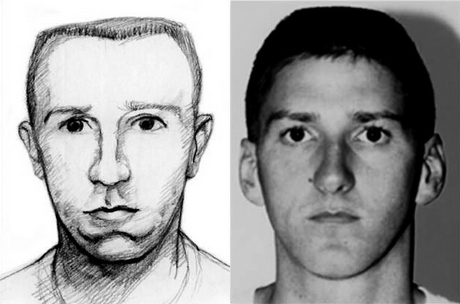

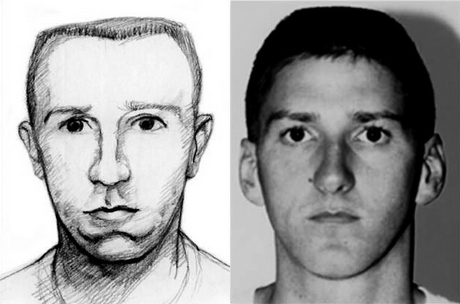

By tracing the

By tracing the vehicle identification number

A vehicle identification number (VIN) (also called a chassis number or frame number) is a unique code, including a serial number, used by the automotive industry to identify individual motor vehicles, towed vehicles, motorcycles, scooters ...

of a rear axle found in the wreckage, the FBI

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic Intelligence agency, intelligence and Security agency, security service of the United States and its principal Federal law enforcement in the United States, federal law enforcement age ...

identified the vehicle as a Ryder

Ryder System, Inc., commonly known as Ryder, is an American transportation and logistics company. It is especially known for its fleet of commercial rental trucks.

Ryder specializes in fleet management, supply chain management, and transp ...

rental box truck rented from Junction City, Kansas

Junction City is a city in and the county seat of Geary County, Kansas, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population of the city was 22,932. Fort Riley, a major U.S. Army post, is nearby.

History

Junction City is so named from its ...

. Workers at the agency assisted an FBI artist in creating a sketch of the renter, who had used the alias "Robert Kling". The sketch was shown in the area. Lea McGown, manager of the local Dreamland Motel, identified the sketch as Timothy McVeigh.

Shortly after the bombing, while driving on Interstate 35 in Noble County, near Perry, Oklahoma

Perry is a city in, and county seat of, Noble County, Oklahoma, United States. As of the 2010 census, the city population was 5,126, a 2.0 percent decrease from the figure of 5,230 in 2000. The city is home of Ditch Witch construction equipment. ...

, McVeigh was stopped by State Trooper Charles J. Hanger. Hanger had passed McVeigh's yellow 1977 Mercury Marquis

The Mercury Marquis is a model line of automobiles that was marketed by the Mercury division of Ford Motor Company from the 1967 to 1986 model years. Deriving its name from a French nobility title, the Marquis was introduced as a rebadged coun ...

and noticed that it had no license plate. McVeigh admitted to the state trooperwho noticed a bulge under his jacketthat he had a gun; the trooper arrested him for driving without plates and possessing an illegal firearm. McVeigh's concealed weapon

Concealed carry, or carrying a concealed weapon (CCW), is the practice of carrying a weapon (usually a sidearm such as a handgun), either in proximity to or on one's person or in public places in a manner that hides or conceals the weapon's pre ...

permit was not legal in Oklahoma. McVeigh was wearing a shirt at that time with a picture of Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

and the motto ('Thus always to tyrants'), the supposed words shouted by John Wilkes Booth

John Wilkes Booth (May 10, 1838 – April 26, 1865) was an American stage actor who assassinated United States President Abraham Lincoln at Ford's Theatre in Washington, D.C., on April 14, 1865. A member of the prominent 19th-century Booth th ...

after he shot Lincoln. On the back, it had a tree with a picture of three blood droplets and the Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

quote, "The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants." Three days later, McVeigh was identified as the subject of the nationwide manhunt.

On August 10, 1995, McVeigh was indicted on 11 federal counts, including conspiracy to use a weapon of mass destruction, use of a weapon of mass destruction, destruction with the use of explosives, and eight counts of first degree murder for the deaths of law enforcement officers. On February 20, 1996, the Court granted a

On August 10, 1995, McVeigh was indicted on 11 federal counts, including conspiracy to use a weapon of mass destruction, use of a weapon of mass destruction, destruction with the use of explosives, and eight counts of first degree murder for the deaths of law enforcement officers. On February 20, 1996, the Court granted a change of venue

A change of venue is the legal term for moving a trial to a new location. In high-profile matters, a change of venue may occur to move a jury trial away from a location where a fair and impartial jury may not be possible due to widespread public ...

and ordered that the case be transferred from Oklahoma City

Oklahoma City (), officially the City of Oklahoma City, and often shortened to OKC, is the capital and largest city of the U.S. state of Oklahoma. The county seat of Oklahoma County, it ranks 20th among United States cities in population, a ...

to the District Court in Denver

Denver () is a consolidated city and county, the capital, and most populous city of the U.S. state of Colorado. Its population was 715,522 at the 2020 census, a 19.22% increase since 2010. It is the 19th-most populous city in the Unit ...

, to be presided over by District Judge Richard Paul Matsch

Richard Paul Matsch (June 8, 1930 – May 26, 2019) was an American judge who served as Senior Status, Senior United States federal judge, United States district judge of the United States District Court for the District of Colorado.

Education an ...

.

McVeigh instructed his lawyers to use a necessity defense

In the criminal law of many nations, necessity may be either a possible justification or an exculpation for breaking the law. Defendants seeking to rely on this defense argue that they should not be held liable for their actions as a crime ...

, but they ended up not doing so. They would have had to prove that McVeigh was in "imminent danger" from the government. McVeigh argued that "imminent" did not necessarily mean "immediate." They would have argued that his bombing of the Murrah building was a justifiable response to what McVeigh believed were the crimes of the U.S. government at Waco, Texas

Waco ( ) is the county seat of McLennan County, Texas, United States. It is situated along the Brazos River and I-35, halfway between Dallas and Austin. The city had a 2020 population of 138,486, making it the 22nd-most populous city in the ...

, where the 51-day siege of the Branch Davidian

The Branch Davidians (or the General Association of Branch Davidian Seventh-day Adventists) were an apocalyptic new religious movement founded in 1955 by Benjamin Roden. They regard themselves as a continuation of the General Association of ...

complex resulted in the deaths of 76 Branch Davidians. As part of the defense, McVeigh's lawyers showed the jury the controversial video '' Waco, the Big Lie''.

On June 2, 1997, McVeigh was found guilty on all 11 counts of the federal indictment. Although 168 people, including 19 children, were killed in the April 19, 1995, bombing, murder charges were brought against McVeigh for only the eight federal agents who were on duty when the bomb destroyed much of the Murrah Building. Along with the eight counts of murder, McVeigh was charged with conspiracy to use a weapon of mass destruction, and destroying a federal building. Oklahoma City District Attorney Bob Macy said he would file state charges in the other 160 murders after McVeigh's co-defendant, Terry Nichols, was tried. After the verdict, McVeigh tried to calm his mother by saying, "Think of it this way. When I was in the Army, you didn't see me for years. Think of me that way now, like I'm away in the Army again, on an assignment for the military."

On June 13, the jury recommended that McVeigh receive the death penalty. The U.S. Department of Justice brought federal charges against McVeigh for causing the deaths of eight federal officers leading to a possible death penalty for McVeigh; they could not bring charges against McVeigh for the remaining 160 deaths in federal court because those deaths fell under the jurisdiction of the State of Oklahoma. Because McVeigh was convicted and sentenced to death, the State of Oklahoma did not file murder charges against McVeigh for the other 160 deaths. Before the sentence was formally pronounced by Judge Matsch, McVeigh addressed the court for the first time and said: "If the Court please, I wish to use the words of Justice [Louis] Brandeis dissenting in '' Olmstead [v. United States]'' to speak for me. He wrote, 'Our Government is the potent, the omnipresent teacher. For good or for ill, it teaches the whole people by its example.' That's all I have."

Incarceration and execution

McVeigh's death sentence was delayed pending an appeal. One of his appeals for , taken to the

McVeigh's death sentence was delayed pending an appeal. One of his appeals for , taken to the Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

, was denied on March 8, 1999. McVeigh's request for a nationally televised execution was also denied. An Internet company unsuccessfully sued for the right to broadcast the execution. At USP Florence ADMAX, McVeigh and Nichols were housed in what was known as "bomber's row". Ted Kaczynski

Theodore John Kaczynski ( ; born May 22, 1942), also known as the Unabomber (), is an American domestic terrorist and former mathematics professor. Between 1978 and 1995, Kaczynski killed three people and injured 23 others in a nationwide ...

, Luis Felipe, and Ramzi Yousef

Ramzi Ahmed Yousef ( ur, , translit=''Ramzī Ahmad Yūsuf''; born 20 May 1967 or 27 April 1968) is a Pakistani convicted terrorist who was one of the main perpetrators of the 1993 World Trade Center bombing and the bombing of Philippine Airlines ...

were also housed in this cell block. Yousef made frequent, unsuccessful attempts to convert McVeigh to Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic Monotheism#Islam, monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God in Islam, God (or ...

.

McVeigh said: "I am sorry these people had to lose their lives, but that's the nature of the beast. It's understood going in what the human toll will be." He said that if there turned out to be an afterlife, he would " improvise, adapt and overcome", noting: "If there is a hell, then I'll be in good company with a lot of fighter pilots who also had to bomb innocents to win the war." He also said: "I knew I wanted this before it happened. I knew my objective was state-assisted suicide and when it happens, it's in your face. You just did something you're trying to say should be illegal for medical personnel."

The Federal Bureau of Prisons

The Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) is a United States federal law enforcement agency under the Department of Justice that is responsible for the care, custody, and control of incarcerated individuals who have committed federal crimes; that i ...

(BOP) transferred McVeigh from USP Florence ADMAX to the federal death row at USP Terre Haute

The United States Penitentiary, Terre Haute (USP Terre Haute) is a maximum-security United States federal prison for male inmates in Terre Haute, Indiana. It is part of the Federal Correctional Complex, Terre Haute (FCC Terre Haute) and is oper ...

in Terre Haute, Indiana

Terre Haute ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Vigo County, Indiana, United States, about 5 miles east of the state's western border with Illinois. As of the 2010 census, the city had a population of 60,785 and its metropolitan area had a ...

, in 1999. McVeigh dropped his remaining appeals, saying that he would rather die than spend the rest of his life in prison. On January 16, 2001, the BOP set May 16 as McVeigh's execution date. McVeigh said that his only regret was not completely destroying the federal building. Six days prior to his scheduled execution, the FBI turned over thousands of documents of evidence it had previously withheld to McVeigh's attorneys. As a result, U.S. Attorney General John Ashcroft announced McVeigh's execution would be stayed for one month. The execution date was reset for June 11. McVeigh invited conductor David Woodard

David Woodard (, ; born April 6, 1964) is an American conductor and writer. During the 1990s he coined the term ''prequiem'', a portmanteau of preemptive and requiem, to describe his Buddhist practice of composing dedicated music to be rendered d ...

to perform Requiem Mass music on the eve of his execution. While acknowledging McVeigh's "horrible deed", Woodard consented, intending to "provide comfort". McVeigh also requested a Catholic chaplain. His last meal

A condemned prisoner's last meal is a customary ritual preceding execution. In many countries, the prisoner may, within reason, select what the last meal will be.

Contemporary restrictions in the United States

In the United States, most states gi ...

consisted of two pint

The pint (, ; symbol pt, sometimes abbreviated as ''p'') is a unit of volume or capacity in both the imperial unit, imperial and United States customary units, United States customary measurement systems. In both of those systems it is tradition ...

s of mint chocolate chip ice cream.

McVeigh chose

McVeigh chose William Ernest Henley

William Ernest Henley (23 August 184911 July 1903) was an English poet, writer, critic and editor. Though he wrote several books of poetry, Henley is remembered most often for his 1875 poem "Invictus". A fixture in London literary circles, the o ...

's poem "Invictus

"Invictus" is a short poem by the Victorian era British poet William Ernest Henley (1849–1903). It was written in 1875 and published in 1888 in his first volume of poems, ''Book of Verses'', in the section ''Life and Death (Echoes)''.

Backgr ...

" as his final statement. Just before the execution, when he was asked if he had a final statement, he declined. Jay Sawyer, a relative of one of the victims, wrote, "Without saying a word, he got the final word." Larry Whicher, whose brother died in the attack, described McVeigh as having "a totally expressionless, blank stare. He had a look of defiance and that if he could, he'd do it all over again." McVeigh was executed by lethal injection

Lethal injection is the practice of injecting one or more drugs into a person (typically a barbiturate, paralytic, and potassium solution) for the express purpose of causing rapid death. The main application for this procedure is capital puni ...

at 7:14 a.m. on June 11, 2001, the first federal prisoner to be executed since Victor Feguer

Victor Harry Feguer (1935 – March 15, 1963) was a convicted murderer and the last federal inmate executed in the United States before the moratorium on the death penalty following '' Furman v. Georgia'', and the last person put to death in ...

was executed in Iowa on March 15, 1963.

On November 21, 1997, President Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton ( né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. He previously served as governor of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and agai ...

had signed S. 923, special legislation introduced by Senator Arlen Specter

Arlen Specter (February 12, 1930 – October 14, 2012) was an American lawyer, author and politician who served as a United States Senator from Pennsylvania from 1981 to 2011. Specter was a Democrat from 1951 to 1965, then a Republican from ...

to bar McVeigh and other veterans convicted of capital crimes from being buried in any military cemetery. His body was cremated at Mattox Ryan Funeral Home in Terre Haute. His ashes were given to his lawyer, who said "the final destination of McVeigh's remains would remain privileged forever." McVeigh had written that he considered having them dropped at the site of the memorial where the building once stood, but decided that would be "too vengeful, too raw, too cold." He had expressed willingness to donate organs, but was prohibited from doing so by prison regulations. Psychiatrist John Smith concluded that McVeigh was "a decent person who had allowed rage to build up inside him to the point that he had lashed out in one terrible, violent act." McVeigh's IQ was assessed at 126.

Associations

According to CNN, his only known associations were as a registeredRepublican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

while in Buffalo, New York

Buffalo is the second-largest city in the U.S. state of New York (behind only New York City) and the seat of Erie County. It is at the eastern end of Lake Erie, at the head of the Niagara River, and is across the Canadian border from South ...

, in the 1980s, and a membership in the National Rifle Association

The National Rifle Association of America (NRA) is a gun rights advocacy group based in the United States. Founded in 1871 to advance rifle marksmanship, the modern NRA has become a prominent Gun politics in the United States, gun rights ...

while in the Army.

There is no evidence that he ever belonged to any extremist groups.Profile oTimothy McVeigh

CNN

CNN (Cable News Network) is a multinational cable news channel headquartered in Atlanta, Georgia, U.S. Founded in 1980 by American media proprietor Ted Turner and Reese Schonfeld as a 24-hour cable news channel, and presently owned by ...

, March 29, 2001. Retrieved February 22, 2015.

Religious beliefs

McVeigh was raisedRoman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

.Patrick Cole"A Look Back in TIME: Interview with Timothy McVeigh"

March 30, 1996. Retrieved October 19, 2010. During his childhood, he and his father attended

Mass

Mass is an intrinsic property of a body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the quantity of matter in a physical body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physics. It was found that different atoms and different elementar ...

regularly. McVeigh was confirmed

In Christian denominations that practice infant baptism, confirmation is seen as the sealing of the covenant created in baptism. Those being confirmed are known as confirmands. For adults, it is an affirmation of belief. It involves laying on ...

at the Good Shepherd Church in Pendleton, New York, in 1985. In a 1996 interview, McVeigh professed belief in "a God", although he said he had "sort of lost touch with" Catholicism and "I never really picked it up, however I do maintain core beliefs." In McVeigh's biography ''American Terrorist'', released in 2002, he stated that he did not believe in a hell

In religion and folklore, hell is a location in the afterlife in which evil souls are subjected to punitive suffering, most often through torture, as eternal punishment after death. Religions with a linear divine history often depict hell ...

and that science is his religion. In June 2001, a day before the execution, McVeigh wrote a letter to the ''Buffalo News'' identifying himself as agnostic

Agnosticism is the view or belief that the existence of God, of the divine or the supernatural is unknown or unknowable. (page 56 in 1967 edition) Another definition provided is the view that "human reason is incapable of providing sufficient ...

.Julian Borge"McVeigh faces day of reckoning: Special report: Timothy McVeigh,"

, ''

The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

'', June 11, 2001. Retrieved October 19, 2010. However, he took the last rites

The last rites, also known as the Commendation of the Dying, are the last prayers and ministrations given to an individual of Christian faith, when possible, shortly before death. They may be administered to those awaiting execution, mortall ...

, administered by a priest, just before his execution. Father Charles Smith ministered to McVeigh in his last moments on death row.

Motivations for the bombing

McVeigh claimed that the bombing was revenge against the government for the sieges at Waco and Ruby Ridge. McVeigh visited Waco during the standoff. While there, he was interviewed by student reporter Michelle Rauch, a senior journalism major atSouthern Methodist University

, mottoeng = "The truth will make you free"

, established =

, type = Private research university

, accreditation = SACS

, academic_affiliations =

, religious_affiliation = United Methodist Church

, president = R. Gerald Turner

, prov ...

who was writing for the school paper. McVeigh expressed his objections over what was happening there.

McVeigh frequently quoted and alluded to the white supremacist novel ''The Turner Diaries

''The Turner Diaries'' is a 1978 novel by William Luther Pierce, published under the pseudonym Andrew Macdonald. It depicts a violent revolution in the United States which leads to the overthrow of the federal government, a nuclear war, and, ...

''; he claimed to appreciate its interest in firearms. Photocopies of pages sixty-one and sixty-two of ''The Turner Diaries'' were found in an envelope inside McVeigh's car. These pages depicted a fictitious mortar attack upon the U.S. Capitol

The United States Capitol, often called The Capitol or the Capitol Building, is the Seat of government, seat of the Legislature, legislative branch of the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government, which is form ...

in Washington.

In a 1,200-word essay dated March 1998, from the federal maximum-security prison at Florence, Colorado, McVeigh claimed that the terrorist bombing was "morally equivalent" to U.S. military actions against Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

and other foreign countries. The handwritten essay, submitted to and published by the alternative national news magazine ''Media Bypass'', was distributed worldwide by the Associated Press

The Associated Press (AP) is an American non-profit news agency headquartered in New York City. Founded in 1846, it operates as a cooperative, unincorporated association. It produces news reports that are distributed to its members, U.S. newspa ...

on May 29, 1998. This was written in the midst of the 1998 Iraq disarmament crisis

The Iraq disarmament crisis was claimed as one of primary issues that led to the multinational invasion of Iraq on 20 March 2003. Since the 1980s, Iraq was widely assumed to have been producing and extensively running the programs of biolog ...

and a few months before Operation Desert Fox

The 1998 bombing of Iraq (code-named Operation Desert Fox) was a major four-day bombing campaign on Iraqi targets from 16 to 19 December 1998, by the United States and the United Kingdom. On 16 December 1998, President of the United States Bill ...

.

On April 26, 2001, McVeigh wrote a letter to Fox News

The Fox News Channel, abbreviated FNC, commonly known as Fox News, and stylized in all caps, is an American multinational conservative cable news television channel based in New York City. It is owned by Fox News Media, which itself is owne ...

, "I Explain Herein Why I Bombed the Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City", which explicitly laid out his reasons for the attack. McVeigh read the novel ''Unintended Consequences

In the social sciences, unintended consequences (sometimes unanticipated consequences or unforeseen consequences) are outcomes of a purposeful action that are not intended or foreseen. The term was popularised in the twentieth century by Ameri ...

'' (1996), and said that if it had come out a few years earlier, he would have given serious consideration to using sniper attacks in a war of attrition

The War of Attrition ( ar, حرب الاستنزاف, Ḥarb al-Istinzāf; he, מלחמת ההתשה, Milhemet haHatashah) involved fighting between Israel and Egypt, Jordan, the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) and their allies from ...

against the government instead of bombing a federal building.

Accomplices

McVeigh's accompliceTerry Nichols

Terry Lynn Nichols (born April 1, 1955) is an American domestic terrorist who was convicted of being an accomplice in the Oklahoma City bombing. Prior to his incarceration, he held a variety of short-term jobs, working as a farmer, grain elevato ...

was convicted and sentenced in federal court to life in prison for his role in the crime. At Nichols' trial, evidence was presented indicating that others may have been involved. Several residents of central Kansas, including real estate agent Georgia Rucker and a retired Army NCO, testified at Terry Nichols' federal trial that they had seen two trucks at Geary Lake State Park, where prosecutors alleged the bomb was assembled. The retired NCO said he visited the lake on April 18, 1995, but left after a group of surly men looked at him aggressively. The operator of the Dreamland Motel testified that two Ryder trucks had been parked outside her Grandview Plaza motel where McVeigh stayed in Room 26 the weekend before the bombing. Terry Nichols is incarcerated at ADX Florence

The United States Penitentiary, Florence Administrative Maximum Facility (USP Florence ADMAX), commonly known as ADX Florence, is an American federal prison in Fremont County near Florence, Colorado. It is operated by the Federal Bureau of Pris ...

in Florence, Colorado.

Michael and Lori Fortier

The Oklahoma City bombing was a domestic terrorist truck bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, United States, on April 19, 1995. Perpetrated by two anti-government extremists, Timothy McVeigh and Terry N ...

were also considered accomplices, due to their foreknowledge of the bombing. In addition to Michael assisting McVeigh in scouting the federal building, Lori had helped McVeigh laminate a fake driver's license which was used to rent the Ryder truck. Fortier agreed to testify against McVeigh and Nichols in exchange for a reduced sentence and immunity for his wife. He was sentenced on May 27, 1998, to twelve years in prison and fined $75,000 for failing to warn authorities about the bombing. On January 20, 2006, Fortier was released for good behavior into the Witness Protection Program

Witness protection is security provided to a threatened person providing testimonial evidence to the justice system, including defendants and other clients, before, during, and after a trial, usually by police. While a witness may only require p ...

and given a new identity.

An ATF informant, Carol Howe, told reporters that shortly before the bombing she had warned her handlers that guests of the private community of Elohim City, Oklahoma

Elohim City'' Elohim'' is a Hebrew word usually translated as "God", sometimes "Gods" because in Hebrew most plural masculine nouns end in ''–im''. (also known as Elohim City Inc. and Elohim Village) is a private community in Adair County, Ok ...

were planning a major bombing attack. McVeigh was issued a speeding ticket there at the same time. Other than this speeding ticket, there is no evidence of a connection between McVeigh and members of the Midwest Bank Robbers

The Aryan Republican Army (ARA), also dubbed "The Midwest Bank bandits" by the FBI and law-enforcement, was a white nationalist terrorist gang which robbed 22 banks in the Midwestern United States, Midwest from 1994 to 1996. The bank robberies ...

at Elohim City.

Some witnesses claimed to have seen a second suspect, and there was a search for a "John Doe #2", but none was ever found.

In popular culture

As part of the expanded timeline for the official website of the 2003 alternate universe movie '' C.S.A.: The Confederate States of America'', McVeigh is a terrorist who bombed theJefferson Memorial

The Jefferson Memorial is a presidential memorial built in Washington, D.C. between 1939 and 1943 in honor of Thomas Jefferson, the principal author of the United States Declaration of Independence, a central intellectual force behind the Am ...

in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

in 1995. His execution is aired live on national television and is shown on pay-per-view

Pay-per-view (PPV) is a type of pay television or webcast service that enables a viewer to pay to watch individual events via private telecast.

Events can be purchased through a multichannel television platform using their electronic program guid ...

where it gets many viewers.

In the 2012 alternate universe novel ''The Mirage

The Mirage is a casino resort on the Las Vegas Strip in Paradise, Nevada, Paradise, Nevada, United States. It is owned by Vici Properties and operated by Hard Rock International. The 65-acre property includes a casino and 3,044 rooms.

Mirage R ...

'', McVeigh is a CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian intelligence agency, foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gat ...

officer of the Evangelical Republic of Texas. Terry Nichols is mentioned as an associate.

See also

*Capital punishment by the United States federal government

Capital punishment is a legal penalty under the criminal justice system of the United States federal government. It can be imposed for treason, espionage, murder, large-scale drug trafficking, or attempted murder of a witness, juror, or court ...

* Capital punishment in the United States

In the United States, capital punishment is a legal penalty throughout the country at the federal level, in 27 states, and in American Samoa. It is also a legal penalty for some military offenses. Capital punishment has been abolished in 23 s ...

* List of people executed by the United States federal government

The following is a list of people executed by the United States federal government.

Post-''Gregg'' executions

Sixteen executions (none of them military) have occurred in the modern post-''Gregg'' era. Since 1963, sixteen people have been execut ...

References

Notes

Further reading

* Jones, Stephen, and Peter Israel (2001). ''Others Unknown: Timothy McVeigh and the Oklahoma City Bombing Conspiracy''. 2nd ed. New York: PublicAffairs. . * Madeira, Jody Lyneé (2012). ''Killing McVeigh: The Death Penalty and the Myth of Closure''. New York:NYU Press

New York University Press (or NYU Press) is a university press that is part of New York University.

History

NYU Press was founded in 1916 by the then chancellor of NYU, Elmer Ellsworth Brown.

Directors

* Arthur Huntington Nason, 1916–1932 ...

. .

* Michel, Lou, and Dan Herbeck

Dan Herbeck (born October 31, 1954) is an American journalist and author who is an investigative reporter at ''The Buffalo News''.

Biography

Herbeck was born in Mineral Wells, Texas, and raised in Amherst, New York. Herbeck graduated high schoo ...

(2001). '' American Terrorist: Timothy McVeigh and the Oklahoma City Bombing''. New York: ReganBooks/HarperCollins

HarperCollins Publishers LLC is one of the Big Five English-language publishing companies, alongside Penguin Random House, Simon & Schuster, Hachette, and Macmillan. The company is headquartered in New York City and is a subsidiary of News Cor ...

. .

* Stickney, Brandon M. (1996). "All-American Monster: The Unauthorized Biography of Timothy McVeigh". Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books. .

* Vidal, Gore (2002). ''Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace: How We Got to Be So Hated''. Thunder's Mouth Press

Perseus Books Group was an American publishing company founded in 1996 by investor Frank Pearl. Perseus acquired the trade publishing division of Addison-Wesley (including the Merloyd Lawrence imprint) in 1997. It was named Publisher of the Ye ...

/Nation Books. .

* Wright, Stuart A. (2007). ''Patriots, Politics, and the Oklahoma City Bombing''. New York: Cambridge University Press

Cambridge University Press is the university press of the University of Cambridge. Granted letters patent by Henry VIII of England, King Henry VIII in 1534, it is the oldest university press

A university press is an academic publishing hou ...

. .

External links

"Bad Day Dawning"

in "Criminals and Methods: Timothy McVeigh" at

Court TV

Court TV is an American digital broadcast network and former cable television channel. It was originally launched in 1991 with a focus on crime-themed programs such as true crime documentary series, legal analysis talk shows, and live news cove ...

: Crime Library

Crime Library was a website documenting major crimes, criminals, trials, forensics, and criminal profiling from books. It was founded in 1998 and was most recently owned by truTV, a cable TV network that is part of Time Warner's Turner Broadcas ...

Timothy McVeigh's April 27, 2001 letter to reporter Rita Cosby

xplains why he bombed the Murrah Federal Building (posted on independence.net)

at

The Smoking Gun

The Smoking Gun is a website that posts legal documents, arrest records, and police mugshots on a daily basis. The intent is to bring to the public light information that is somewhat obscure or unreported by more mainstream media sources. Most o ...

The Timothy McVeigh Story: The Oklahoma Bomber

at

Court TV

Court TV is an American digital broadcast network and former cable television channel. It was originally launched in 1991 with a focus on crime-themed programs such as true crime documentary series, legal analysis talk shows, and live news cove ...

: Crime Library

Crime Library was a website documenting major crimes, criminals, trials, forensics, and criminal profiling from books. It was founded in 1998 and was most recently owned by truTV, a cable TV network that is part of Time Warner's Turner Broadcas ...

Voices of Oklahoma interview with Stephen Jones.

First person interview conducted on January 27, 2010, with Stephen Jones, lawyer for Timothy McVeigh.

ritique of Timothy McVeigh by fellow inmate Unabomber

– ''

USA Today

''USA Today'' (stylized in all uppercase) is an American daily middle-market newspaper and news broadcasting company. Founded by Al Neuharth on September 15, 1982, the newspaper operates from Gannett's corporate headquarters in Tysons, Virgini ...

''

{{DEFAULTSORT:McVeigh, Timothy

1968 births

2001 deaths

1995 murders in the United States

20th-century American criminals

21st-century executions by the United States federal government

21st-century executions of American people

American conspiracy theorists

American male criminals

American mass murderers

American murderers of children

American people convicted of murder

American people of Irish descent

Bombers (people)

Bryant and Stratton College alumni

Crime in Oklahoma

Criminals from New York (state)

Executed mass murderers

Executed people from New York (state)

Far-right terrorism

Inmates of ADX Florence

Military personnel from New York (state)

Oklahoma City bombing

Patriot movement

People convicted of murder by the United States federal government

People convicted on terrorism charges

People executed by the United States federal government by lethal injection

People from Lockport, New York

United States Army non-commissioned officers

United States Army personnel of the Gulf War