Office Of Censorship on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Office of Censorship was an emergency wartime agency set up by the United States federal government on December 19, 1941 to aid in the censorship of all communications coming into and going out of the

The Office of Censorship was an emergency wartime agency set up by the United States federal government on December 19, 1941 to aid in the censorship of all communications coming into and going out of the

Avoiding Bloodshed? US Journalists and Censorship in Wartime

''War & Society'', Volume 32, Issue 1, 2013.

{{Authority control Government agencies established in 1941 1945 disestablishments in the United States Defunct agencies of the United States government United States government secrecy Agencies of the United States government during World War II Censorship in the United States

The Office of Censorship was an emergency wartime agency set up by the United States federal government on December 19, 1941 to aid in the censorship of all communications coming into and going out of the

The Office of Censorship was an emergency wartime agency set up by the United States federal government on December 19, 1941 to aid in the censorship of all communications coming into and going out of the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

, including its territories and the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

. The efforts of the Office of Censorship to balance the protection of sensitive war related information with the constitutional freedoms of the press is considered largely successful.

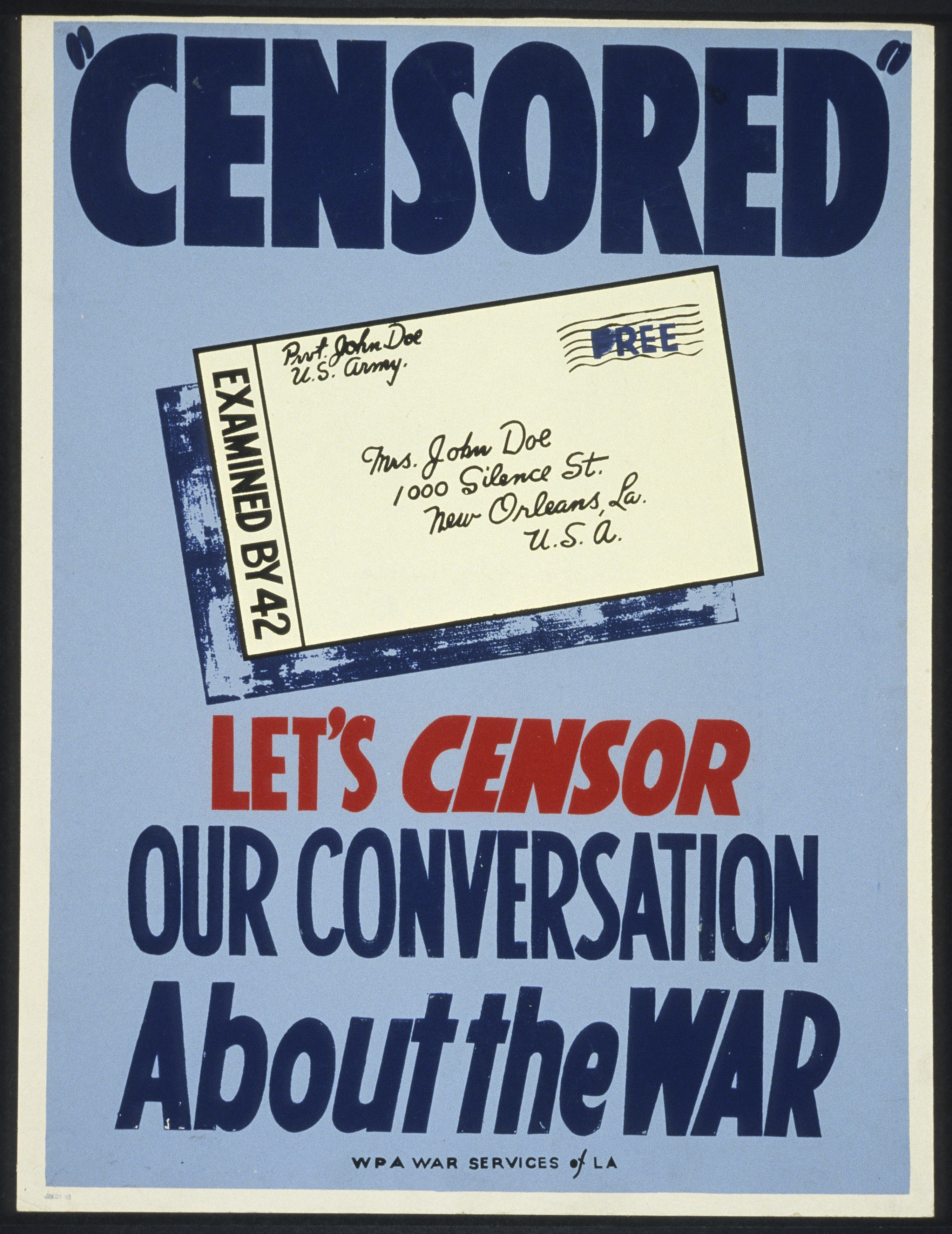

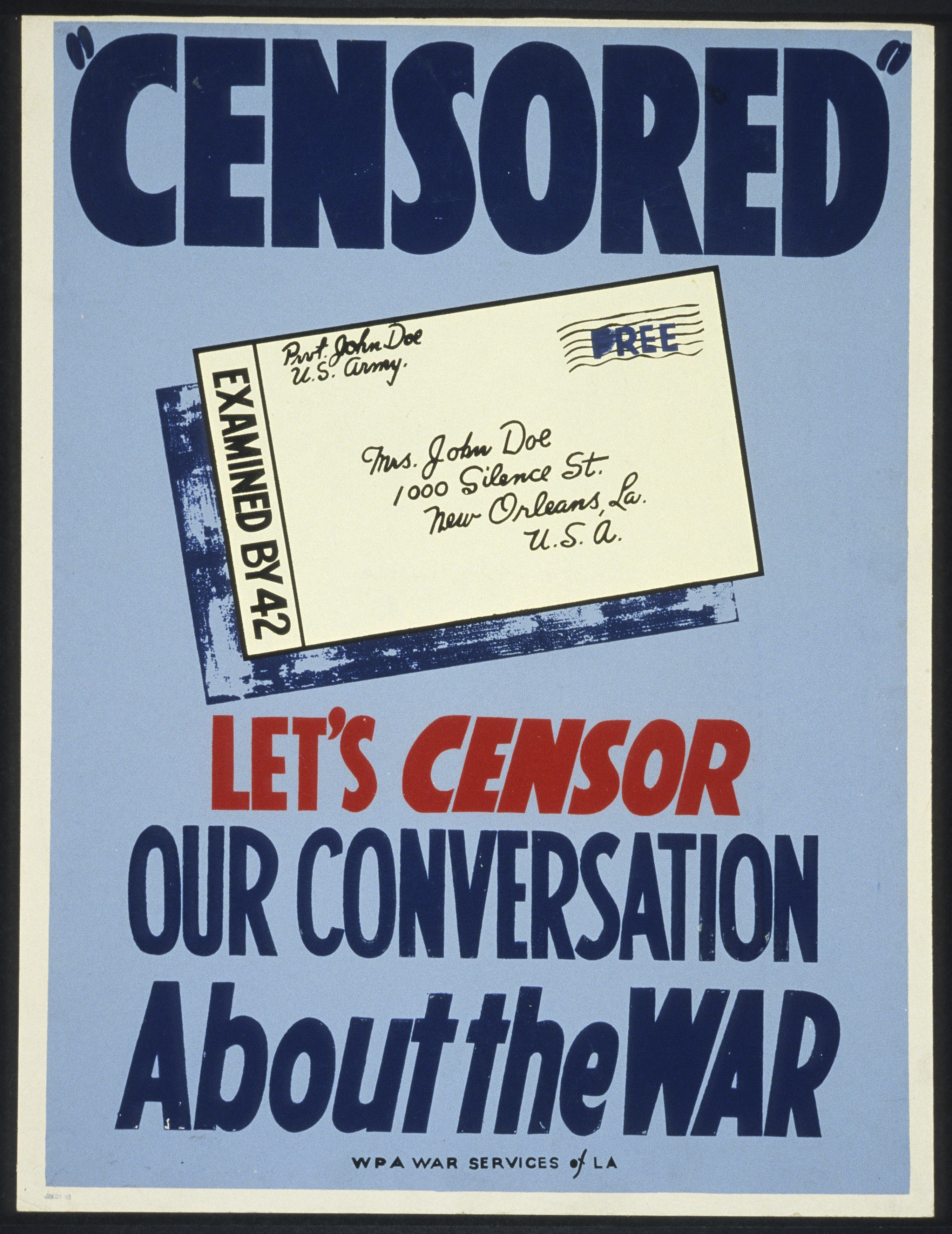

The agency's implementation of censorship was done primarily through a voluntary regulatory code that was willingly adopted by the press. The phrase "loose lips sink ships

Loose lips sink ships is an American English idiom meaning "beware of unguarded talk". The phrase originated on propaganda posters during World War II. The phrase was created by the War Advertising Council and used on posters by the United State ...

" was popularized during World War II, which is a testament to the urgency Americans felt to protect information relating to the war effort. Radio broadcasts, newspapers, and newsreels were the primary ways Americans received their information about World War II and therefore were the medium most affected by the Office of Censorship code. The closure of the Office of Censorship in November 1945 corresponded with the ending of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

.

History

Immediate predecessors

Censorship

Censorship is the suppression of speech, public communication, or other information. This may be done on the basis that such material is considered objectionable, harmful, sensitive, or "inconvenient". Censorship can be conducted by governments ...

by the American press began on a voluntary basis before America's official entry into World War II. In 1939, after the war had already begun in Europe, journalists in America started withholding information about Canadian troop movements.Sweeney, Michael S. (2001). ''Secrets of Victory: The Office of Censorship and the American Press and Radio in World War II''. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. In September 1939, President Roosevelt declared a state of national emergency. In response to the threat of war, branches in the United States government that explicitly regulated censorship popped up within the Military and Navy. These branches were the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, which began in September 1939, and the Censorship Branch in the Military Intelligence Division which formed in June 1941. A Joint Board was also established in September 1939 to facilitate censorship planning between the Military and Navy departments of the US government.

The bombing of Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Haw ...

on December 7, 1941 caused the official entry of America into World War II and the reorganizing of government activities responsible for censoring communication in and out of the United States. The First War Powers Act

The War Powers Act of 1941, also known as the First War Powers Act, was an American emergency law that increased Federal power during World War II. The act was signed by U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt and put into law on December 18, 1941 ...

, passed on December 18, 1941, contained broad grants of Executive authority, including a provision on censorship.

Executive Order 8985

On December 19, 1941, PresidentFranklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

signed Executive Order 8985, which established the Office of Censorship and conferred on its director the power to censor international communications in "his absolute discretion." The order set up a Censorship Policy Board to advise the director on policy coordination and integration of censorship activities. It also authorized the director to establish a Censorship Operating Board that would bring together other government agencies to deal with issues of communication interception. By March 15, 1942, all military personnel who had been working on the Joint Board or on operations at the direction of the Joint Board were moved into the Office of Censorship.

The Director of Censorship

Byron Price

Byron Price (March 25, 1891August 6, 1981) was director of the U.S. Office of Censorship during World War II.

Life

Price was born near Topeka, Indiana on 25 March 1891. He was a magazine editor at Topeka High School, and worked as a journalist an ...

, who was the executive news editor at the Associated Press

The Associated Press (AP) is an American non-profit news agency headquartered in New York City. Founded in 1846, it operates as a cooperative, unincorporated association. It produces news reports that are distributed to its members, U.S. newspa ...

, accepted the position of Director of Censorship on 19 December 1941 under the conditions that he would report directly to Roosevelt and that the president agreed with his desire to continue voluntary censorship. Throughout Price's tenure, the responsibility for censorship in the media was entirely on journalists. His motto for convincing the media to comply was, "Least said, soonest mended." Although over 30 agencies in the US government at the time of World War II had some censorship role, the foundation of government policies relied heavily on the patriotism and voluntary cooperation of news establishments. The American Civil Liberties Union

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) is a nonprofit organization founded in 1920 "to defend and preserve the individual rights and liberties guaranteed to every person in this country by the Constitution and laws of the United States". T ...

said that Price had "censored the press and made them like it."

Price advocated against decentralizing the Office of Censorship and prevented it from merging with the Office of War Information

The United States Office of War Information (OWI) was a United States government agency created during World War II. The OWI operated from June 1942 until September 1945. Through radio broadcasts, newspapers, posters, photographs, films and other ...

. Price believed that a merger with the Office of War Information (OWI) would prevent the public from receiving truthful information with regards to war time efforts. While OWI and the Office of Censorship, both primarily dealt with censoring information related to the war, the OWI was also involved in political propaganda campaigns.

Though the official closure of the Office of Censorship did not come until November 1945, one day following the August 14th, 1945 Japanese surrender, Price hung a sign outside of his office door that read "out of business." In January 1946, then President Harry Truman praised Price's work at the agency and awarded Price the Medal for Merit

The Medal for Merit was, during the period it was awarded, the highest civilian decoration of the United States. It was awarded by the President of the United States to civilians who "distinguished themselves by exceptionally meritorious conduct i ...

, which was at the time the highest decoration that could be awarded to an American civilian.

Activities

To effect closer coordination of censorship activities during the war effort, representatives of Great Britain, Canada, and the United States signed an agreement providing for the complete exchange of information among all concerned parties. They also created a central clearinghouse of information within the headquarters of the Office of Censorship. Price utilized existing facilities of theWar Department War Department may refer to:

* War Department (United Kingdom)

* United States Department of War (1789–1947)

See also

* War Office, a former department of the British Government

* Ministry of defence

* Ministry of War

* Ministry of Defence

* Dep ...

and Navy Department wherever possible. On March 15, 1942, Army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

and Navy

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval warfare, naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral zone, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and ...

personnel engaged in censorship activities moved from the War Department and Navy Department to the Office of Censorship. There they monitored the 350,000 overseas cables and telegrams and 25,000 international telephone calls each week. Offices in Los Angeles, New York City, and Rochester, New York

Rochester () is a City (New York), city in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York, the county seat, seat of Monroe County, New York, Monroe County, and the fourth-most populous in the state after New York City, Buffalo, New York, Buffalo, ...

reviewed films.Kennett, Lee (1985). ''For the duration... : the United States goes to war, Pearl Harbor-1942''. New York: Scribner. .

Radio was especially vulnerable to government control under the Communications Act of 1934

The Communications Act of 1934 is a United States federal law signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on June 19, 1934 and codified as Chapter 5 of Title 47 of the United States Code, et seq. The Act replaced the Federal Radio Commission with ...

. The voluntary nature of censorship relieved many broadcasters, which had expected that war would cause the government to seize all stations and draft their employees into the army. Such authority existed; Attorney General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

Francis Biddle

Francis Beverley Biddle (May 9, 1886 – October 4, 1968) was an American lawyer and judge who was the United States Attorney General during World War II. He also served as the primary American judge during the postwar Nuremberg Trials as well a ...

issued an opinion to Price in early 1942 that gave him almost unlimited authority over broadcasting. As an experienced journalist who disliked having to act as censor, he feared that a nationwide takeover of radio would result in a permanent government monopoly. Price believed that voluntary cooperation must be tried first with mandatory censorship only if necessary, and persuaded other government officials and the military to agree.

End of the agency

As the military situation improved, plans for adjustment and eventual cessation of censorship were devised. Executive Order 9631 issued the formal cessation of the Office of Censorship on September 28, 1945. The order became effective on November 15, 1945. Price thanked journalists nationwide for their cooperation: "You deserve, and you have, the thanks and appreciation of your Government. And my own gratitude and that of my colleagues in the unpleasant task of administering censorship is beyond words or limit." In a postwar memo to PresidentHarry Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

on future wartime censorship procedures, Price wrote that "no one who does not dislike censorship should ever be permitted to exercise censorship" and urged that voluntary cooperation be again used.

The Code of Wartime Practices for the American Press

The Code of Wartime Practices for the American Press was first issued on January 15, 1942 by the Office of Censorship. It had subsequent versions released on June 15, 1942 and on May 15, 1945 post-victory in Europe. The code set forth in simple terms—only seven pages for broadcasters, and five for the printed press—subjects that contained information of value to the enemy and which, therefore, should not be published or broadcast in the United States without authorization by a qualified government source. Price promised that "what does not concern the war does not concern censorship." Rather than having government officials review all articles and columns, the newspapers and radio stations voluntarily adopted to seek approval from a relevant government agency before discussing information on sensitive subjects. These sensitive subjects included factory production figures, troop movements, damages to American forces, and weather reports. All major news organizations in addition to 1,600 accredited wartime correspondents pledged to adhere to the code. A 24-hour hotline quickly answered media questions on appropriate topics.

"Man in the street"

There was no government mandate to publish or broadcast positive news, unlike theCommittee on Public Information

The Committee on Public Information (1917–1919), also known as the CPI or the Creel Committee, was an independent agency of the government of the United States under the Wilson administration created to influence public opinion to support the ...

during World War I. Complying with the code ended popular media features, however. Radio stations had to discontinue programs with audience participation and interviews because of the risk that an enemy agent might use the microphone. Similarly, lost-and-found advertisements ended and All Request programs were asked to avoid complying with specific times for music requests, in both cases to prevent encoded transmission of secret data. Stations cooperated despite losing the advertising revenue from sponsors; Price later estimated that losing man on the street programs alone cost stations "tens of millions of dollars" during the war, although the increase in war-related advertisements more than compensated.

Weather

The Office of Censorship and theWeather Bureau

The National Weather Service (NWS) is an agency of the United States federal government that is tasked with providing weather forecasts, warnings of hazardous weather, and other weather-related products to organizations and the public for the p ...

saw weather as especially sensitive. Military authorities asked the Office of Censorship to severely limit information about the weather because they feared too much information would help the enemy attack. Weather-related news comprised about half of all code violations. While newspapers could print temperature tables and regular bureau forecasts, the code asked radio stations to use only specially approved bureau forecasts to prevent enemy submarines from learning of current conditions. From January 15, 1942 to October 12, 1943 broadcasters said nothing about rain, snow, fog, wind, air pressure, temperature, or sunshine unless it was approved by the Weather Bureau. After Memphis, Tennessee

Memphis is a city in the U.S. state of Tennessee. It is the seat of Shelby County in the southwest part of the state; it is situated along the Mississippi River. With a population of 633,104 at the 2020 U.S. census, Memphis is the second-mos ...

stations could not discuss tornadoes that killed hundreds in March 1942, the code was changed to permit emergency bulletins but only if approved by the office. The office saw current weather conditions as so sensitive that it considered banning broadcasting any outdoor sports event, but decided that sport's benefit to morale was too important. When fog so covered a Chicago football game in August 1942 that the radio play-by-play announcer

In sports broadcasting, a sports commentator (also known as sports announcer or sportscaster) provides a real-time commentary of a game or event, usually during a live broadcast, traditionally delivered in the historical present tense. Radio wa ...

could not see the field, the Weather Bureau thanked him for never using the word "fog" or mentioning the weather. In 1942, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt

Anna Eleanor Roosevelt () (October 11, 1884November 7, 1962) was an American political figure, diplomat, and activist. She was the first lady of the United States from 1933 to 1945, during her husband President Franklin D. Roosevelt's four ...

wrote a newspaper column about her travel across the country, in which she described the weather. She received "a very stern letter" from the Office of Censorship reprimanding her.

Presidential travel

The code specifically restricted information on "movements of the President of the United States". As Price reported only to the President, Roosevelt effectively became censor of all news about himself. When he toured war factories around the country for two weeks in September 1942, for example, only threewire service

A news agency is an organization that gathers news reports and sells them to subscribing news organizations, such as newspapers, magazines and radio and television broadcasters. A news agency may also be referred to as a wire service, newswire, ...

reporters accompanied him on the private railroad car

A private railroad car, private railway coach, private car, or private varnish is a railroad passenger car either originally built or later converted for service as a business car for private individuals. A private car could be added to the make- ...

''Ferdinand Magellan

Ferdinand Magellan ( or ; pt, Fernão de Magalhães, ; es, link=no, Fernando de Magallanes, ; 4 February 1480 – 27 April 1521) was a Portuguese explorer. He is best known for having planned and led the 1519 Spanish expedition to the East ...

''. They filed articles for later publication, and despite being seen by tens of thousands of Americans, almost no mention appeared in the press of the president's trip until after it ended. Similar procedures were used on later domestic and international trips, such as to Casablanca

Casablanca, also known in Arabic as Dar al-Bayda ( ar, الدَّار الْبَيْضَاء, al-Dār al-Bayḍāʾ, ; ber, ⴹⴹⴰⵕⵍⴱⵉⴹⴰ, ḍḍaṛlbiḍa, : "White House") is the largest city in Morocco and the country's econom ...

in 1943 and Yalta

Yalta (: Я́лта) is a resort city on the south coast of the Crimean Peninsula surrounded by the Black Sea. It serves as the administrative center of Yalta Municipality, one of the regions within Crimea. Yalta, along with the rest of Crimea ...

in 1945. While the majority of reporters supported voluntarily censoring themselves over such travel, Roosevelt also used the code to hide frequent weekend trips to Springwood Estate

The Home of Franklin D. Roosevelt National Historic Site preserves the Springwood estate in Hyde Park, New York. Springwood was the birthplace, lifelong home, and burial place of the 32nd president of the United States, Franklin D. Roosevelt. Th ...

and, some believed, the meetings with former lover Lucy Rutherford that began again in 1944. During the 1944 presidential election, he may have used his ability to avoid press reports to hide evidence of worsening health. Such arbitrary use of the code was controversial among Washington reporters, and Price privately wrote that Roosevelt "greatly abused" the press's cooperation.

Restrictions

Price stated throughout the war that he wanted censorship to end as soon as possible. The code of conduct was relaxed in October 1943 to permit weather information except barometric pressure and wind direction, and weather programs returned to radio. Most restrictions ended afterV-E Day

Victory in Europe Day is the day celebrating the formal acceptance by the Allies of World War II of Germany's unconditional surrender of its armed forces on Tuesday, 8 May 1945, marking the official end of World War II in Europe in the Easte ...

in May 1945, with the code only four pages in length after its final revision.

Censorship failures

Two censorship failures of World War II: * On June 7, 1942 the ''Chicago Tribune

The ''Chicago Tribune'' is a daily newspaper based in Chicago, Illinois, United States, owned by Tribune Publishing. Founded in 1847, and formerly self-styled as the "World's Greatest Newspaper" (a slogan for which WGN radio and television ar ...

'' announcement of breaking of Japanese Purple (cipher machine)

In the history of cryptography, the "System 97 Typewriter for European Characters" (九七式欧文印字機) or "Type B Cipher Machine", codenamed Purple by the United States, was an encryption machine used by the Japanese Foreign Office f ...

.

* In June, 1943 Congressman Andrew Jackson May

Andrew Jackson May (June 24, 1875 – September 6, 1959) was a Kentucky attorney, an influential New Deal-era politician, and chairman of the United States House Committee on Military Affairs, House Military Affairs Committee during World War II, ...

disclosed that Japanese depth charges were set too shallow-and resulted in the estimated losses of 10 US Submarines and 800 servicemen.

**List of US Submarines lost by depth charges: 19 out of 53 lost; 1522 crew lost

**USS Barbel (SS-316)

USS ''Barbel'' (SS-316), a ''Balao''-class submarine, was the first ship of the United States Navy to be named for the barbel, a fish commonly called a minnow or carp.

Construction and commissioning

''Barbel'' keel was laid down by the Elec ...

4 February 1945

** USS Bonefish (SS-223) 18 June 1945

** USS Bullhead (SS-332) 6 August 1945

** USS Cisco (SS-290) 28 September 1943

**USS Golet (SS-361)

USS ''Golet'' (SS-361), a Gato class submarine, ''Gato''-class submarine, was the only ship of the United States Navy to be named for the Dolly Varden trout, golet, a California trout.

Construction and commissioning

''Golet'' initially was or ...

14 June 1944

**USS Grayback (SS-208)

USS ''Grayback'' (SS-208), a Tambor-class submarine, ''Tambor''-class submarine, was the first ship of the United States Navy to be named for the lake herring, ''Coregonus artedi''. She ranked 20th among all U.S. submarines in total tonnage sun ...

27 February 1944

**USS Grayling (SS-209)

USS ''Grayling'' (SS-209) was the tenth Tambor class submarine, ''Tambor''-class submarine to be commissioned in the United States Navy in the years leading up to the country's December 1941 entry into World War II. She was the fourth ship of ...

9 September 1943

** USS Growler (SS-215) 8 November 1944

** USS Gudgeon (SS-211) 18 April 1944

**USS Harder (SS-257)

, a Gato class submarine, ''Gato''-class submarine, was the first ship of the United States Navy to be named for the Harder (fish), Harder, a fish of the mullet (fish), mullet family found off South Africa. One of the most famous submarines of ...

24 August 1944

**USS Lagarto (SS-371)

USS ''Lagarto'' (SS-371), a , was the only ship of the United States Navy to be named for the lagarto, a lizard fish.

Construction and commissioning

''Lagarto''′s keel was laid down on 12 January 1944 by the Manitowoc Shipbuilding Company o ...

4 May 1945

**USS S-44 (SS-155)

USS ''S-44'' (SS-155) was a third-group (''S-42'') S-class submarine of the United States Navy.

Construction and commissioning

''S-44''′s keel was laid down on 19 February 1921 by the Bethlehem Shipbuilding Corporation's Fore River Shipyard ...

7 October 1943

**USS Scamp (SS-277)

USS ''Scamp'' (SS-277), a Gato class submarine, ''Gato''-class submarine, was the first ship of the United States Navy to be named for the scamp grouper, a member of the family Serranidae.

Construction and commissioning

''Scamp''′s keel was ...

11 November 1944

**USS Sculpin (SS-191)

USS ''Sculpin'' (SS-191), a ''Sargo''-class submarine, was the first ship of the United States Navy to be named for the sculpin.

Construction and commissioning

''Sculpin''′s keel was laid down on 7 September 1937 at the Portsmouth Navy Yard ...

19 November 1943

**USS Shark (SS-314)

USS ''Shark'' (SS-314), a , was the sixth ship of the United States Navy to be named for the shark, a large marine predator.

Construction began in 1943 and commissioning occurred in 1944. Following shakedown, ''Shark'' was deployed to the Pa ...

24 October 1944

**USS Swordfish (SS-193)

USS ''Swordfish'' (SS-193), a ''Sargo''-class submarine, was the first submarine of the United States Navy named for the swordfish, a large fish with a long, swordlike beak and a high dorsal fin. She was the first American submarine to sink a ...

12 January 1945

**USS Trigger (SS-237)

USS ''Trigger'' (SS-237) was a submarine, the first ship of the United States Navy to be named for the triggerfish.

Construction

''Trigger''s keel was laid down on 1 February 1941 at Mare Island, California, by the Mare Island Navy Yard. She ...

28 March 1945

** USS Trout (SS-202) 29 February 1944

**USS Wahoo (SS-238)

was a , the first United States Navy ship to be named for the wahoo. Construction started before the U.S. entered World War II, and she was commissioned after entry. ''Wahoo'' was assigned to the Pacific theatre. She gained fame as an aggres ...

11 October 1943

Censorship of the atomic bomb

Price called theManhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

, the United States' development of the atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

, the best-kept secret of the war. It and radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance (''ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor vehicles, w ...

were the two military topics that, if a code violation occurred, the office did not allow this to be used as a precedent for permitting other media outlets to report the same information. The government made a general announcement on radar in April 1943, and government and military officials frequently leaked information on the subject, but restrictions did not end until the day after Japan's surrender in August 1945.

From mid-1943 until the bombing of Hiroshima

The United States detonated two atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945, respectively. The two bombings killed between 129,000 and 226,000 people, most of whom were civilians, and remain the on ...

in August 1945, the Office of Censorship helped keep the Manhattan Project secret by asking the press and broadcasters to voluntarily censor information they learned about atomic energy or the project. Perhaps the worst press violation occurred in August 1944, when due to procedural errors a nationwide Mutual Network

The Mutual Broadcasting System (commonly referred to simply as Mutual; sometimes referred to as MBS, Mutual Radio or the Mutual Radio Network) was an American commercial radio network in operation from 1934 to 1999. In the golden age of U.S. rad ...

broadcast mentioned the military creating a weapon in Pasco, Washington involving atom splitting. The Office of Censorship asked all recordings of the broadcast to be destroyed. As with radar, officials sometimes disclosed information to the press without authorization. That was not the first request for voluntary censorship of atomic-related information. Price noted in comments to reporters after the end of censorship that some 20,000 news outlets had been delivered similar requests. For the most part censors were able to keep sensitive information about the Manhattan Project from being published or broadcast. Slips of the tongue occurred with individuals knowledgeable about the project.

Another serious breach of secrecy occurred in March 1944, when John Raper of the ''Cleveland Press

The ''Cleveland Press'' was a daily American newspaper published in Cleveland, Ohio from November 2, 1878, through June 17, 1982. From 1928 to 1966, the paper's editor was Louis B. Seltzer.

Known for many years as one of the country's most in ...

'' published "Forbidden City". The reporter, who had heard rumors while vacationing in New Mexico, described a secret project in Los Alamos, calling it "Uncle Sam's mystery town directed by '2nd Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theory ...

'", J. Robert Oppenheimer

J. Robert Oppenheimer (; April 22, 1904 – February 18, 1967) was an American theoretical physicist. A professor of physics at the University of California, Berkeley, Oppenheimer was the wartime head of the Los Alamos Laboratory and is oft ...

. It speculated that the project was working on chemical warfare

Chemical warfare (CW) involves using the toxic properties of chemical substances as weapons. This type of warfare is distinct from nuclear warfare, biological warfare and radiological warfare, which together make up CBRN, the military acronym ...

, powerful new explosives, or a beam that would cause German aircraft engines to fail. Manhattan Project leaders called the article "a complete lack of responsibility, compliance with national censorship code and cooperation with the Government in keeping an important project secret", and considered drafting Raper into the military, but the article apparently did not cause Axis

An axis (plural ''axes'') is an imaginary line around which an object rotates or is symmetrical. Axis may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Axis of rotation: see rotation around a fixed axis

* Axis (mathematics), a designator for a Cartesian-coordinat ...

spies to investigate the project. After Hiroshima ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' was first to report on the specifics of the Manhattan Project on August 7, 1945, saying the bomb was built in "three 'hidden cities' with a total population of 100,000 inhabitants"; Los Alamos, Oak Ridge, Tennessee

Oak Ridge is a city in Anderson and Roane counties in the eastern part of the U.S. state of Tennessee, about west of downtown Knoxville. Oak Ridge's population was 31,402 at the 2020 census. It is part of the Knoxville Metropolitan Area. Oak ...

, and Hanford, Washington

Hanford was a small agricultural community in Benton County, Washington, United States. It and White Bluffs, Washington, White Bluffs were depopulated in 1943 in order to make room for the nuclear production facility known as the Hanford Site. The ...

. "None of the people, who came to these developments from homes all the way from Maine to California, had the slightest idea of what they were making in the gigantic Government plants they saw around them," the ''New York Times'' said.

See also

*Postal censorship

Postal censorship is the inspection or examination of mail, most often by governments. It can include opening, reading and total or selective obliteration of letters and their contents, as well as covers, postcards, parcels and other postal pa ...

*Censorship in the United States

Censorship in the United States involves the suppression of speech or public communication and raises issues of freedom of speech, which is protected by the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. Interpretation of this fundamental ...

*Military history of the United States during World War II

The military history of the United States during World War II covers the victorious Allied war against the Axis Powers, starting with the 7 December 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor and ending with the 2 September 1945 surrender of Japan. During ...

*United States home front during World War II

The United States home front during World War II supported the war effort in many ways, including a wide range of volunteer efforts and submitting to government-managed Rationing in the United States, rationing and price controls. There was a gen ...

References

*Henry T. Ulasek. The National Archives of the United States Preliminary Inventories: Number 54: Records of the Office of Censorship. The National Archives and Records Service: 1953. p. 1-4. *History of the Office of Censorship. Volume II: Press and Broadcasting Divisions. TheNational Archives and Records Administration

The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) is an " independent federal agency of the United States government within the executive branch", charged with the preservation and documentation of government and historical records. It i ...

. Record group 216, box 1204.

*

Further reading

*Michael S. Sweeney. ''Secrets of Victory: The Office of Censorship and the American Press and Radio in World War II'', (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2001). *Smyth, DanielAvoiding Bloodshed? US Journalists and Censorship in Wartime

''War & Society'', Volume 32, Issue 1, 2013.

External links

{{Authority control Government agencies established in 1941 1945 disestablishments in the United States Defunct agencies of the United States government United States government secrecy Agencies of the United States government during World War II Censorship in the United States