Ottoman–Venetian War (1570–1573) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Fourth Ottoman–Venetian War, also known as the War of Cyprus () was fought between 1570 and 1573. It was waged between the

After concluding a prolonged war in Hungary with the

After concluding a prolonged war in Hungary with the

On 27 June, the invasion force, some 350–400 ships and 100,000 men, set sail for Cyprus. It landed unopposed at Salines, near

On 27 June, the invasion force, some 350–400 ships and 100,000 men, set sail for Cyprus. It landed unopposed at Salines, near

Both sides sought the decisive engagement, for which they had amassed, according to some estimates, between 70 and 90 percent of all galleys in existence in the Mediterranean at the time. The fleets were roughly balanced: the Ottoman fleet was larger with 278 ships to the 212 Christian ones, but the Christian ships were sturdier; both fleets carried some 30,000 soldiers whereas the Ottoman fleet had 50,000 sailors and oarsmen and Christian fleet had 20,000 sailors and oarsmen, and while the Christians had twice as many cannons, the Ottomans compensated by a large and skilled corps of archers. On 7 October, the two fleets engaged in the

Both sides sought the decisive engagement, for which they had amassed, according to some estimates, between 70 and 90 percent of all galleys in existence in the Mediterranean at the time. The fleets were roughly balanced: the Ottoman fleet was larger with 278 ships to the 212 Christian ones, but the Christian ships were sturdier; both fleets carried some 30,000 soldiers whereas the Ottoman fleet had 50,000 sailors and oarsmen and Christian fleet had 20,000 sailors and oarsmen, and while the Christians had twice as many cannons, the Ottomans compensated by a large and skilled corps of archers. On 7 October, the two fleets engaged in the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

and the Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice, officially the Most Serene Republic of Venice and traditionally known as La Serenissima, was a sovereign state and Maritime republics, maritime republic with its capital in Venice. Founded, according to tradition, in 697 ...

, the latter joined by the Holy League, a coalition of Christian states formed by the pope which included Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

(with Naples

Naples ( ; ; ) is the Regions of Italy, regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 908,082 within the city's administrative limits as of 2025, while its Metropolitan City of N ...

and Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

), the Republic of Genoa

The Republic of Genoa ( ; ; ) was a medieval and early modern Maritime republics, maritime republic from the years 1099 to 1797 in Liguria on the northwestern Italy, Italian coast. During the Late Middle Ages, it was a major commercial power in ...

, the Duchy of Savoy

The Duchy of Savoy (; ) was a territorial entity of the Savoyard state that existed from 1416 until 1847 and was a possession of the House of Savoy.

It was created when Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor, raised the County of Savoy into a duchy f ...

, the Knights Hospitaller

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem, commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller (), is a Catholic military order. It was founded in the crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem in the 12th century and had headquarters there ...

, and the Grand Duchy of Tuscany

The Grand Duchy of Tuscany (; ) was an Italian monarchy located in Central Italy that existed, with interruptions, from 1569 to 1860, replacing the Republic of Florence. The grand duchy's capital was Florence. In the 19th century the population ...

.

The war, the pre-eminent episode of Sultan Selim II's reign, began with the Ottoman invasion of the Venetian-held island of Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

. The capital Nicosia

Nicosia, also known as Lefkosia and Lefkoşa, is the capital and largest city of Cyprus. It is the southeasternmost of all EU member states' capital cities.

Nicosia has been continuously inhabited for over 5,500 years and has been the capi ...

and several other towns fell quickly to the considerably superior Ottoman army, leaving only Famagusta

Famagusta, also known by several other names, is a city located on the eastern coast of Cyprus. It is located east of the capital, Nicosia, and possesses the deepest harbour of the island. During the Middle Ages (especially under the maritime ...

in Venetian hands. Christian reinforcements were delayed, and Famagusta eventually fell in August 1571 after an 11-month-long siege. Two months later, at the Battle of Lepanto

The Battle of Lepanto was a naval warfare, naval engagement that took place on 7 October 1571 when a fleet of the Holy League (1571), Holy League, a coalition of Catholic states arranged by Pope Pius V, inflicted a major defeat on the fleet of t ...

, the united Christian fleet destroyed the Ottoman fleet, but was unable to take advantage of this victory. The Ottomans quickly rebuilt their naval forces and Venice was forced to negotiate a separate peace, ceding Cyprus to the Ottomans and paying a tribute of 300,000 ducat

The ducat ( ) coin was used as a trade coin in Europe from the later Middle Ages to the 19th century. Its most familiar version, the gold ducat or sequin containing around of 98.6% fine gold, originated in Venice in 1284 and gained wide inter ...

s.

Background

The large and wealthy island ofCyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

had been under Venetian rule since 1489. Together with Crete

Crete ( ; , Modern Greek, Modern: , Ancient Greek, Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the List of islands by area, 88th largest island in the world and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fifth la ...

, it was one of the major overseas possessions of the republic, with the indigenous Greek population reaching an estimated 160,000 in the mid-16th century. Aside from its location, which allowed the control of the Levant

The Levant ( ) is the subregion that borders the Eastern Mediterranean, Eastern Mediterranean sea to the west, and forms the core of West Asia and the political term, Middle East, ''Middle East''. In its narrowest sense, which is in use toda ...

ine trade, the island possessed a profitable production of cotton and sugar. To safeguard their most distant colony, the Venetians paid an annual tribute of 8,000 ducats to the Mamluk sultans of Egypt

The Mamluk Sultanate (), also known as Mamluk Egypt or the Mamluk Empire, was a state that ruled medieval Egypt, Egypt, the Levant and the Hejaz from the mid-13th to early 16th centuries, with Cairo as its capital. It was ruled by a military c ...

, and after their conquest

Conquest involves the annexation or control of another entity's territory through war or Coercion (international relations), coercion. Historically, conquests occurred frequently in the international system, and there were limited normative or ...

by the Ottomans

Ottoman may refer to:

* Osman I, historically known in English as "Ottoman I", founder of the Ottoman Empire

* Osman II, historically known in English as "Ottoman II"

* Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empir ...

in 1517, the agreement was renewed with the Ottoman Porte

The Sublime Porte, also known as the Ottoman Porte or High Porte ( or ''Babıali''; ), was a synecdoche or metaphor used to refer collectively to the central government of the Ottoman Empire in Istanbul. It is particularly referred to the buildin ...

. Nevertheless, the island's strategic location in the Eastern Mediterranean, between the Ottoman heartland of Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

and the newly acquired provinces of the Levant and Egypt, made it a tempting target for future Ottoman expansion.Goffman (2002), p. 155 In addition, the protection offered by the local Venetian authorities to corsairs who harassed Ottoman shipping, including Muslim pilgrims to Mecca

Mecca, officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, is the capital of Mecca Province in the Hejaz region of western Saudi Arabia; it is the Holiest sites in Islam, holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow valley above ...

, rankled the Ottoman leadership.Finkel (2006), p. 158

After concluding a prolonged war in Hungary with the

After concluding a prolonged war in Hungary with the Habsburgs

The House of Habsburg (; ), also known as the House of Austria, was one of the most powerful dynasties in the history of Europe and Western civilization. They were best known for their inbreeding and for ruling vast realms throughout Europe d ...

in 1568, the Ottomans were free to turn their attention to Cyprus.Finkel (2006), p. 160 Sultan Selim II had made the conquest of the island his first priority already before his accession in 1566, relegating Ottoman aid to the Morisco Revolt against Spain and attacks against Portuguese activities in the Indian Ocean to a secondary priority. Not surprisingly for a ruler nicknamed "the Sot", popular legend ascribed this determination to his love of Cypriot wines, but the major political instigator of the conflict, according to contemporary reports, was Joseph Nasi, a Portuguese Jew who had become the Sultan's close friend, and who had already been named to the post of Duke of Naxos

The Duchy of the Archipelago (, , ), also known as Duchy of Naxos or Duchy of the Aegean, was a maritime state created by Venetian interests in the Cyclades archipelago in the Aegean Sea, in the aftermath of the Fourth Crusade, centered on the i ...

upon Selim's accession. Nasi harboured resentment towards Venice and hoped for his own nomination as King of Cyprus after its conquest—he already had a crown and a royal banner made to that effect.

Despite the existing peace treaty with Venice, renewed as recently as 1567, and the opposition of a peace party around Grand Vizier

Grand vizier (; ; ) was the title of the effective head of government of many sovereign states in the Islamic world. It was first held by officials in the later Abbasid Caliphate. It was then held in the Ottoman Empire, the Mughal Empire, the Soko ...

Sokollu Mehmed Pasha

Sokollu Mehmed Pasha (; ; ; 1505 – 11 October 1579) was an Ottoman statesman of Serb origin most notable for being the Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire. Born in Ottoman Herzegovina into an Orthodox Christian family, Mehmed was recruited a ...

, the war party at the Ottoman court prevailed. A favourable juridical opinion by the '' Sheikh ul-Islam'' was secured, which declared that the breach of the treaty was justified since Cyprus was a "former land of Islam" (briefly in the 7th century) and had to be retaken. Money for the campaign was raised by the confiscation and resale of monasteries and churches of the Greek Orthodox Church

Greek Orthodox Church (, , ) is a term that can refer to any one of three classes of Christian Churches, each associated in some way with Christianity in Greece, Greek Christianity, Antiochian Greek Christians, Levantine Arabic-speaking Christian ...

. The Sultan's old tutor, Lala Mustafa Pasha, was appointed as commander of the expedition's land forces.Goffman (2002), p. 156 Müezzinzade Ali Pasha

Müezzinzade Ali Pasha (; also known as Sofu Ali Pasha or Sufi Ali Pasha or Meyzinoğlu Ali Pasha; died 7 October 1571) was an Ottoman statesman and naval officer. He was the Grand Admiral (Kapudan Pasha) in command of the Ottoman fleet at the ...

was appointed as ''Kapudan Pasha

The Kapudan Pasha (, modern Turkish: ), also known as the (, modern: , "Captain of the Sea") was the grand admiral of the Ottoman Navy. Typically, he was based at Galata and Gallipoli during the winter and charged with annual sailings durin ...

''; being totally inexperienced in naval matters, he assigned the able and experienced Piyale Pasha as his principal aide.

On the Venetian side, Ottoman intentions had been clear and an attack against Cyprus had been anticipated for some time. A war scare had broken out in 1564–1565, when the Ottomans eventually sailed for Malta, and unease mounted again in late 1567 and early 1568, as the scale of the Ottoman naval build-up became apparent. The Venetian authorities were further alarmed when the Ottoman fleet visited Cyprus in September 1568 with Nasi in tow, ostensibly for a goodwill visit, but in reality a poorly concealed attempt to spy on the island's defences. The defences of Cyprus, Crete, Corfu

Corfu ( , ) or Kerkyra (, ) is a Greece, Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands; including its Greek islands, small satellite islands, it forms the margin of Greece's northwestern frontier. The island is part of the Corfu (regio ...

, and other Venetian possessions were upgraded in the 1560s, employing the services of the noted military engineer Sforza Pallavicini. Their garrisons were increased, and attempts were made to make the isolated holdings of Crete and Cyprus more self-sufficient by the construction of foundries and gunpowder mills. However, it was widely recognized that Cyprus could not hold for long unaided. Its exposed and isolated location so far from Venice, surrounded by Ottoman territory, put it "in the wolf's mouth" as one contemporary historian wrote.Setton (1984), p. 908 In the event, lack of supplies and even gunpowder would play a critical role in the fall of the Venetian forts to the Ottomans. Venice could also not rely on help from the major Christian power of the Mediterranean, Habsburg Spain

Habsburg Spain refers to Spain and the Hispanic Monarchy (political entity), Hispanic Monarchy, also known as the Rex Catholicissimus, Catholic Monarchy, in the period from 1516 to 1700 when it was ruled by kings from the House of Habsburg. In t ...

, which was embroiled in the suppression of the Dutch Revolt

The Eighty Years' War or Dutch Revolt (; 1566/1568–1648) was an armed conflict in the Habsburg Netherlands between disparate groups of rebels and the Spanish government. The causes of the war included the Reformation, centralisation, exc ...

and domestically against the Moriscos.Abulafia (2012), p. 447 Another problem for Venice was the attitude of the island's population. The harsh treatment and oppressive taxation of the local Orthodox Greek population by the Catholic Venetians had caused great resentment, so that their sympathies generally lay with the Ottomans.

By early 1570, the Ottoman preparations and the warnings sent by the Venetian ''bailo'' at Constantinople, Marco Antonio Barbaro, had convinced the ''Signoria'' that war was imminent. Reinforcements and money were sent post-haste to Crete and Cyprus. In March 1570, an Ottoman envoy was sent to Venice, bearing an ultimatum that demanded the immediate cession of Cyprus. Although some voices were raised in the Venetian ''Signoria'' advocating the cession of the island in exchange for land in Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; ; ) is a historical region located in modern-day Croatia and Montenegro, on the eastern shore of the Adriatic Sea. Through time it formed part of several historical states, most notably the Roman Empire, the Kingdom of Croatia (925 ...

and further trading privileges, the hope of assistance from the other Christian states stiffened the republic's resolve, and the ultimatum was categorically rejected.

Ottoman conquest of Cyprus

On 27 June, the invasion force, some 350–400 ships and 100,000 men, set sail for Cyprus. It landed unopposed at Salines, near

On 27 June, the invasion force, some 350–400 ships and 100,000 men, set sail for Cyprus. It landed unopposed at Salines, near Larnaca

Larnaca, also spelled Larnaka, is a city on the southeast coast of Cyprus and the capital of the Larnaca District, district of the same name. With a district population of 155.000 in 2021, it is the third largest city in the country after Nicosi ...

on the island's southern shore on 3 July, and marched towards the capital, Nicosia

Nicosia, also known as Lefkosia and Lefkoşa, is the capital and largest city of Cyprus. It is the southeasternmost of all EU member states' capital cities.

Nicosia has been continuously inhabited for over 5,500 years and has been the capi ...

.Turnbull (2003), p. 57 The Venetians had debated opposing the landing, but in the face of the superior Ottoman artillery, and the fact that a defeat would mean the annihilation of the island's defensive force, it was decided to withdraw to the forts and hold out until reinforcements arrived.

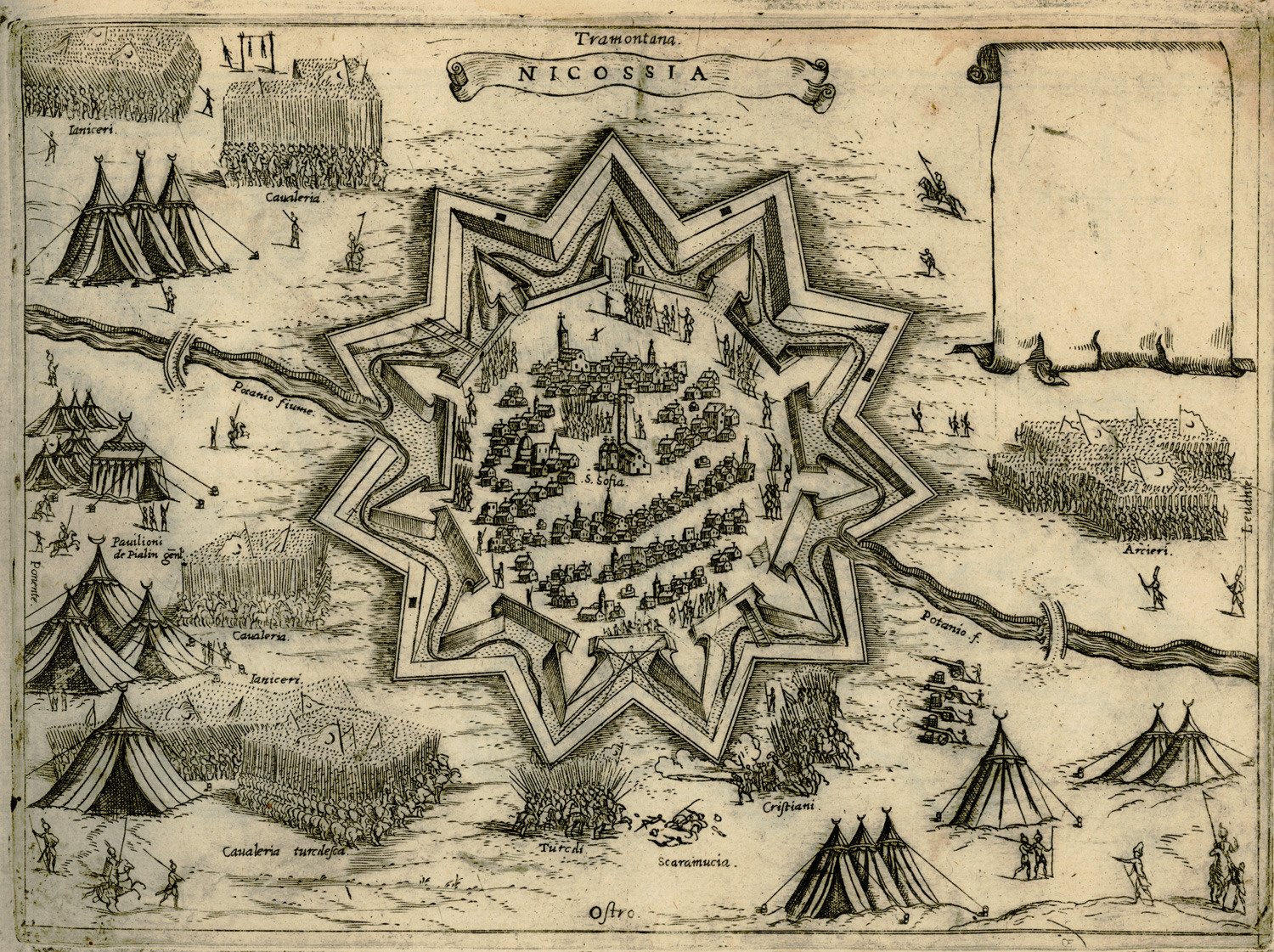

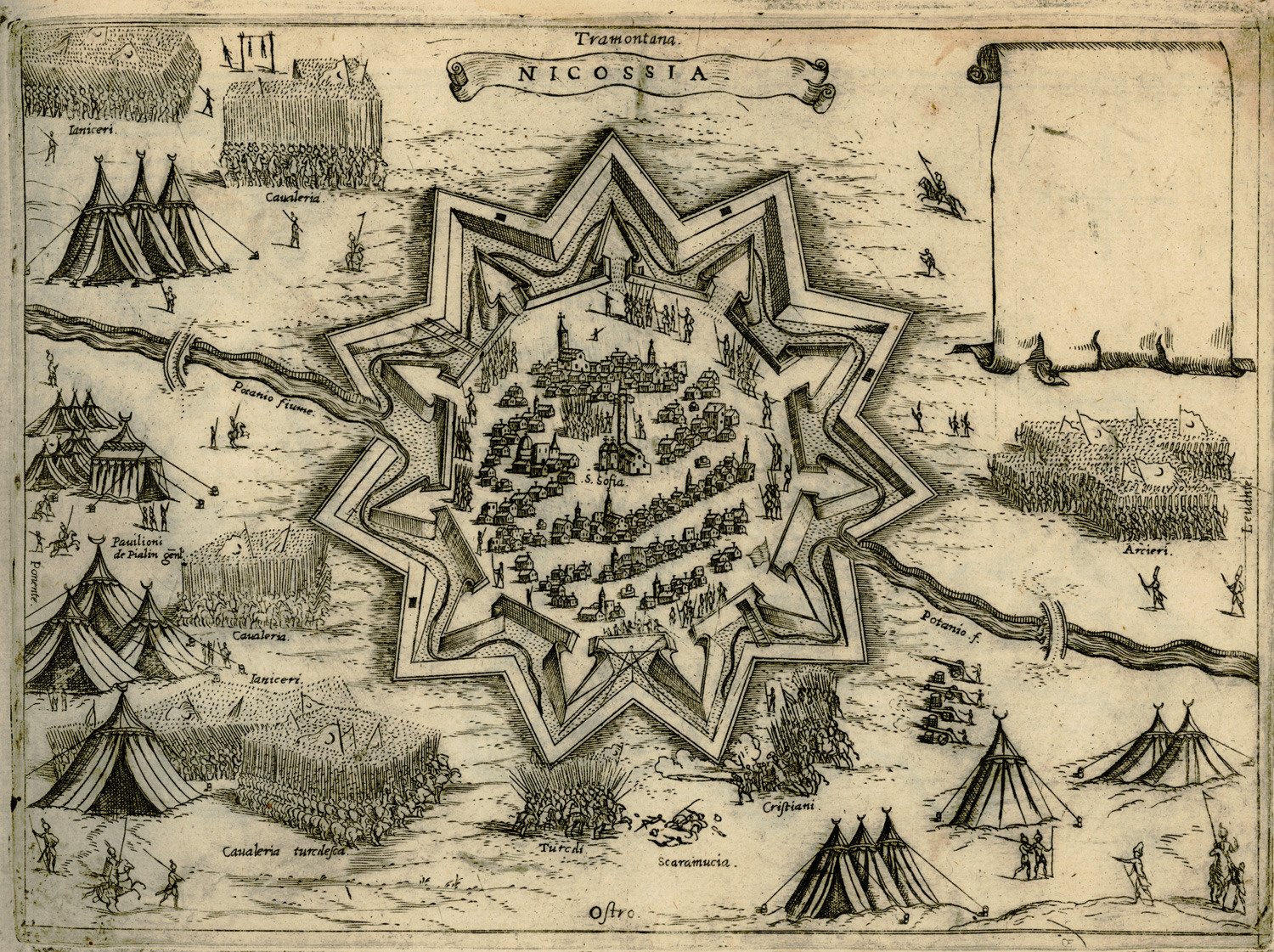

The siege of Nicosia began on 22 July and lasted for seven weeks, until 9 September. The city's newly constructed ''trace italienne

A bastion fort or ''trace italienne'' (a phrase derived from non-standard French, meaning 'Italian outline') is a fortification in a style developed during the early modern period in response to the ascendancy of gunpowder weapons such as c ...

'' walls of packed earth withstood the Ottoman bombardment well. The Ottomans, under Lala Mustafa Pasha, dug trenches towards the walls, and gradually filled the surrounding ditch, while constant volleys of arquebus

An arquebus ( ) is a form of long gun that appeared in Europe and the Ottoman Empire during the 15th century. An infantryman armed with an arquebus is called an arquebusier.

The term ''arquebus'' was applied to many different forms of firearms ...

fire covered the sappers' work.Turnbull (2003), p. 58 Finally, after 45 days of siege, on 9 September, the 15th assault succeeded in breaching the wallsSetton (1976), p. 995 after the defenders had exhausted their ammunition. A massacre of the city's 20,000 inhabitants ensued. Even the city's pigs, regarded as unclean by Muslims, were killed, and only women and boys who were captured to be sold as slaves were spared. A combined Christian fleet of 200 vessels, composed of Venetian (under Girolamo Zane), Papal (under Marcantonio Colonna

Marcantonio II Colonna (sometimes spelled Marc'Antonio; 1535 – August 1, 1584), Duke of Tagliacozzo and Duke and Prince of Paliano, was an Italian aristocrat who served as Viceroy of Sicily in the service of the Spanish Crown, general of ...

), and Neapolitan/Genoese/Spanish (under Giovanni Andrea Doria

Giovanni Andrea Doria (1539 – 1606), also known as Gianandrea Doria, was an Italian admiral from Genoa, the Marquis of Tursi and Prince of Melfi.

Biography

Doria was born to a noble family of the Republic of Genoa. He was the son of Giann ...

) squadrons that had belatedly been assembled at Crete by late August and was sailing towards Cyprus, turned back when it received news of Nicosia's fall.

Following the fall of Nicosia, the fortress of Kyrenia in the north surrendered without resistance, and on 15 September, the Turkish cavalry appeared before the last Venetian stronghold, Famagusta

Famagusta, also known by several other names, is a city located on the eastern coast of Cyprus. It is located east of the capital, Nicosia, and possesses the deepest harbour of the island. During the Middle Ages (especially under the maritime ...

. At this point already, overall Venetian losses (including the local population) were estimated by contemporaries at 56,000 killed or taken prisoner.Setton (1984), p. 990 The Venetian defenders of Famagusta numbered about 8,500 men with 90 artillery pieces and were commanded by Marco Antonio Bragadin. They would hold out for 11 months against a force that would come to number 200,000 men, with 145 guns, providing the time needed by the Pope to cobble together an anti-Ottoman league from the reluctant Christian European states. The Turks set up their guns on 1 September.Hopkins (2007), p. 82 Over the following months, they proceeded to dig a huge network of criss-crossing trenches for a depth of three miles around the fortress, which provided shelter for the Ottoman troops. As the siege trenches neared the fortress and came within artillery range of the walls, ten forts of timber and packed earth and bales of cotton were erected. The Ottomans however lacked the naval strength to completely blockade the city from sea as well, and the Venetians were able to resupply it and bring in reinforcements. After news of such a resupply in January reached the Sultan, he recalled Piyale Pasha and left Lala Mustafa alone in charge of the siege. At the same time, an initiative by Sokollu Mehmed Pasha to achieve a separate peace with Venice foundered. The Grand Vizier offered to concede a trading station at Famagusta if the Republic would cede the island, but the Venetians, encouraged by their recent capture of Durazzo in Albania

Albania ( ; or ), officially the Republic of Albania (), is a country in Southeast Europe. It is located in the Balkans, on the Adriatic Sea, Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea, and shares land borders with Montenegro to ...

and the ongoing negotiations for the formation of a Christian league (see below), refused. Thus on 12 May 1571, the intensive bombardment of Famagusta's fortifications began, and on 1 August, with ammunition and supplies exhausted, the garrison surrendered the city.Turnbull (2003), pp. 59–60 The siege of Famagusta cost the Ottomans some 50,000 casualties.

The Ottomans allowed the Christian residents and surviving Venetian soldiers to leave Famagusta peacefully, but when Lala Mustafa Pasha learned that some Muslim prisoners had been killed during the siege, he had Bragadin mutilated and flayed alive, while his companions were executed. Bragadin's skin was then paraded around the island, before being sent to Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

.

Holy League

As the Ottoman army campaigned in Cyprus, Venice tried to find allies. TheHoly Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans (disambiguation), Emperor of the Romans (; ) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period (; ), was the ruler and h ...

, having just concluded peace with the Ottomans, was not keen to break it. France was traditionally on friendly terms with the Ottomans and hostile to the Spanish, and the Poles were troubled by Muscovy Muscovy or Moscovia () is an alternative name for the Principality of Moscow (1263–1547) and the Tsardom of Russia (1547–1721).

It may also refer to:

*Muscovy Company, an English trading company chartered in 1555

*Muscovy duck (''Cairina mosch ...

. The Spanish Habsburgs, the greatest Christian power in the Mediterranean, were not initially interested in helping the Republic and resentful of Venice's refusal to send aid during the siege of Malta in 1565. In addition, Philip II of Spain

Philip II (21 May 152713 September 1598), sometimes known in Spain as Philip the Prudent (), was King of Spain from 1556, King of Portugal from 1580, and King of Naples and List of Sicilian monarchs, Sicily from 1554 until his death in 1598. He ...

wanted to focus his strength against the Barbary states

The Barbary Coast (also Barbary, Berbery, or Berber Coast) were the coastal regions of central and western North Africa, more specifically, the Maghreb and the Ottoman borderlands consisting of the regencies in Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli, a ...

of North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

. The Spanish reluctance to engage on the side of the Republic, together with Doria's reluctance to endanger his fleet, had already disastrously delayed the joint naval effort in 1570. However, with the energetic mediation of Pope Pius V

Pope Pius V, OP (; 17 January 1504 – 1 May 1572), born Antonio Ghislieri (and from 1518 called Michele Ghislieri), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 7 January 1566 to his death, in May 1572. He was an ...

, an alliance against the Ottomans, the " Holy League", was concluded on 15 May 1571, which stipulated the assembly of a fleet of 200 galleys, 100 supply vessels, and a force of 50,000 men. To secure Spanish assent, the treaty also included a Venetian promise to aid Spain in North Africa.

According to the terms of the new alliance, during the late summer, the Christian fleet assembled at Messina

Messina ( , ; ; ; ) is a harbour city and the capital city, capital of the Italian Metropolitan City of Messina. It is the third largest city on the island of Sicily, and the 13th largest city in Italy, with a population of 216,918 inhabitants ...

, under the command of Don John of Austria

John of Austria (, ; 24 February 1547 – 1 October 1578) was the illegitimate son of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor. Charles V recognized him in a codicil to his will. John became a military leader in the service of his half-brother, King Phil ...

, who arrived on 23 August. By that time, however, Famagusta had fallen, and any effort to save Cyprus was meaningless. Before setting sail for the east, Don John had to deal with the mutual distrust and hostility among the various contingents, especially between the Venetians and the Genoese. The Spanish admiral tackled the problem by breaking the various contingents up and mingle ships from various states. Doria assumed command of the right wing, Don Juan kept the centre, the Venetian Agostino Barbarigo received the left, and the Spaniard Alvaro de Bazan the reserve. Unaware of Famagusta's fate, the allied fleet left Messina on 16 September, and ten days later arrived at Corfu, where it learned of the Ottoman victory. The Ottoman fleet, commanded by Müezzinzade Ali Pasha

Müezzinzade Ali Pasha (; also known as Sofu Ali Pasha or Sufi Ali Pasha or Meyzinoğlu Ali Pasha; died 7 October 1571) was an Ottoman statesman and naval officer. He was the Grand Admiral (Kapudan Pasha) in command of the Ottoman fleet at the ...

, had anchored at Lepanto ( Nafpaktos), near the entrance of the Corinthian Gulf

The Gulf of Corinth or the Corinthian Gulf (, ) is a deep inlet of the Ionian Sea, separating the Peloponnese from western mainland Greece. It is bounded in the east by the Isthmus of Corinth which includes the shipping-designed Corinth Canal and ...

.

Battle of Lepanto

Both sides sought the decisive engagement, for which they had amassed, according to some estimates, between 70 and 90 percent of all galleys in existence in the Mediterranean at the time. The fleets were roughly balanced: the Ottoman fleet was larger with 278 ships to the 212 Christian ones, but the Christian ships were sturdier; both fleets carried some 30,000 soldiers whereas the Ottoman fleet had 50,000 sailors and oarsmen and Christian fleet had 20,000 sailors and oarsmen, and while the Christians had twice as many cannons, the Ottomans compensated by a large and skilled corps of archers. On 7 October, the two fleets engaged in the

Both sides sought the decisive engagement, for which they had amassed, according to some estimates, between 70 and 90 percent of all galleys in existence in the Mediterranean at the time. The fleets were roughly balanced: the Ottoman fleet was larger with 278 ships to the 212 Christian ones, but the Christian ships were sturdier; both fleets carried some 30,000 soldiers whereas the Ottoman fleet had 50,000 sailors and oarsmen and Christian fleet had 20,000 sailors and oarsmen, and while the Christians had twice as many cannons, the Ottomans compensated by a large and skilled corps of archers. On 7 October, the two fleets engaged in the Battle of Lepanto

The Battle of Lepanto was a naval warfare, naval engagement that took place on 7 October 1571 when a fleet of the Holy League (1571), Holy League, a coalition of Catholic states arranged by Pope Pius V, inflicted a major defeat on the fleet of t ...

, which resulted in a crushing victory for the Christian fleet, while the Ottoman fleet was effectively destroyed, losing some 25,000–35,000 men in addition to some 12,000 Christian galley slave

A galley slave was a slave rowing in a galley, either a Convict, convicted criminal sentenced to work at the oar (''French language, French'': galérien), or a kind of human chattel, sometimes a prisoner of war, assigned to the duty of rowing.

...

s who were freed. In popular perception, the battle itself became known as one of the decisive turning points in the long Ottoman-Christian struggle, as it ended the Ottoman naval hegemony established after the Battle of Preveza in 1538. Its immediate results however were minimal: the harsh winter that followed precluded any offensive actions on behalf of the Holy League, while the Ottomans used the respite to hurriedly rebuild their naval strength. At the same time, Venice suffered losses in Dalmatia, where the Ottomans attacked Venetian possessions: the island of Hvar was raided by the Ottoman fleet, with the Turkish forces burning down the towns of Hvar

Hvar (; Chakavian: ''Hvor'' or ''For''; ; ; ) is a Croatian island in the Adriatic Sea, located off the Dalmatian coast, lying between the islands of Brač, Vis (island), Vis and Korčula. Approximately long,

with a high east–west ridge of M ...

, Stari Grad and Vrboska.

The strategic situation after Lepanto was graphically summed up later by the Ottoman Grand Vizier to the Venetian ''bailo'': "The Christians have singed my beard eaning the fleet but I have lopped off an arm. My beard will grow back. The arm eaning Cyprus will not". Despite the Grand Vizier's bold statement, however, the damage suffered by the Ottoman fleet was crippling—not so much in the number of ships lost, but in the almost total loss of the fleet's experienced officers, sailors, technicians and marines. Well aware of how hard it would be to replace such men, in the next year the Venetians and the Spanish executed those experts they had taken captive. In addition, despite the limited strategic impact of the allied victory, an Ottoman victory at Lepanto would have had far more important repercussions: it would have meant the effective disappearance of the Christian naval cadres and allowed the Ottoman fleet to roam the Mediterranean at will, with dire consequences for Malta, Crete and possibly even the Balearics or Venice itself. In the event Lepanto, along with the Ottoman failure at Malta six years earlier, confirmed the ''de facto'' division of the Mediterranean, with the eastern half under firm Ottoman control and the western under the Habsburgs and their Italian allies.

The following year, as the allied Christian fleet resumed operations, it faced a renewed Ottoman navy of 200 vessels under Kılıç Ali Pasha. The Spanish contingent under Don John did not reach the Ionian Sea until September, meaning that the Ottomans enjoyed numerical superiority for a time, but the Ottoman commander was well aware of the inferiority of his fleet, constructed in haste of green wood and manned by inexperienced crews. He therefore actively avoided to engage the allied fleet in August, and eventually headed for the safety of the fortress of Modon. The arrival of the Spanish squadron of 55 ships evened the numbers on both sides and opened the opportunity for a decisive blow, but friction among the Christian leaders and the reluctance of Don John squandered the opportunity.Finkel (2006), p. 161

The diverging interests of the League members began to show, and the alliance began to unravel. In 1573, the Holy League fleet failed to sail altogether; instead, Don John attacked and took Tunis

Tunis (, ') is the capital city, capital and largest city of Tunisia. The greater metropolitan area of Tunis, often referred to as "Grand Tunis", has about 2,700,000 inhabitants. , it is the third-largest city in the Maghreb region (after Casabl ...

, only for it to be retaken by the Ottomans in 1574. Venice, fearing the loss of her Dalmatian possessions and a possible invasion of Friuli

Friuli (; ; or ; ; ) is a historical region of northeast Italy. The region is marked by its separate regional and ethnic identity predominantly tied to the Friulians, who speak the Friulian language. It comprises the major part of the autono ...

, and eager to cut her losses and resume the trade with the Ottoman Empire, initiated unilateral negotiations with the Porte.

Peace settlement and aftermath

Andrea Biagio Badoer, an extraordinary ambassador, conducted the negotiations for Venice. In view of the Republic's inability to regain Cyprus, the resulting treaty, signed on 7 March 1573, confirmed the new state of affairs: Cyprus became an Ottoman province, and Venice paid an indemnity of 300,000ducat

The ducat ( ) coin was used as a trade coin in Europe from the later Middle Ages to the 19th century. Its most familiar version, the gold ducat or sequin containing around of 98.6% fine gold, originated in Venice in 1284 and gained wide inter ...

s. In addition, the border between the two powers in Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; ; ) is a historical region located in modern-day Croatia and Montenegro, on the eastern shore of the Adriatic Sea. Through time it formed part of several historical states, most notably the Roman Empire, the Kingdom of Croatia (925 ...

was modified by the Turkish occupation of small but important parts of the hinterland that included the most fertile agricultural areas near the cities, with adverse effects on the economy of the Venetian cities in Dalmatia.

Peace would continue between the two states until 1645, when a long war over Crete would break out. Cyprus itself remained under Ottoman rule until 1878, when it was ceded to Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* Great Britain, a large island comprising the countries of England, Scotland and Wales

* The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, a sovereign state in Europe comprising Great Britain and the north-eas ...

as a protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a State (polity), state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over ...

. Ottoman sovereignty

Sovereignty can generally be defined as supreme authority. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within a state as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the person, body or institution that has the ultimate au ...

continued until the outbreak of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, when the island was annexed

Annexation, in international law, is the forcible acquisition and assertion of legal title over one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. In current international law, it is generally held to ...

by Britain, becoming a crown colony

A Crown colony or royal colony was a colony governed by Kingdom of England, England, and then Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain or the United Kingdom within the English overseas possessions, English and later British Empire. There was usua ...

in 1925.Borowiec (2000), pp. 19–21

Portrayal in film

The war is referenced in the 1998 movie '' Dangerous Beauty'', released as ''A Destiny of Her Own'' in some countries—about the life ofVeronica Franco

Veronica Franco (c. 1546–1591) was an Italian poet and courtesan in 16th-century Venice. She is known for her notable clientele, feminist advocacy, literary contributions, and philanthropy. Her humanist education and cultural contributions inf ...

, portrayed by Catherine McCormack. The film was based on the 1992 book '' The Honest Courtesan'', by US author Margaret F. Rosenthal.

Notes

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Ottoman-Venetian War (1570-73) 1570s conflicts 1570s in Europe 1570s in the Ottoman Empire 1570s in the Papal States Invasions of Cyprus Military history of Corfu (city) Naval warfare of the Early Modern period Ottoman Cyprus Ottoman–Spanish conflicts Venetian Cyprus War scare Wars involving Spain Wars involving the Knights Hospitaller Wars involving the Papal States