The

military history of the United States during

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

covers the victorious

Allied war against the

Axis Powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

, starting with the 7 December 1941

attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii ...

and ending with the 2 September 1945

surrender of Japan

The surrender of the Empire of Japan in World War II was announced by Emperor Hirohito on 15 August and formally signed on 2 September 1945, bringing the war's hostilities to a close. By the end of July 1945, the Imperial Japanese Na ...

. During the first two years of

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, the

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

had maintained formal

neutrality which was made official in the

Quarantine Speech which was delivered by

US President

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States ...

Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1937, while it was supplying

Britain, the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

, and

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

with war

materiel

Materiel (; ) refers to supplies, equipment, and weapons in military supply-chain management, and typically supplies and equipment in a commercial supply chain context.

In a military context, the term ''materiel'' refers either to the spec ...

through the

Lend-Lease Act which was signed into law on 11 March 1941, as well as

deploying the US military to replace the

British forces stationed in Iceland. Following the "

Greer incident" Roosevelt publicly confirmed the "shoot on sight" order on 11 September 1941, effectively declaring naval war on Germany and Italy in the

Battle of the Atlantic

The Battle of the Atlantic, the longest continuous military campaign in World War II, ran from 1939 to the defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945, covering a major part of the naval history of World War II. At its core was the Allies of World War II, ...

. In the

Pacific Theater, there was unofficial early US combat activity such as the

Flying Tigers

The First American Volunteer Group (AVG) of the Republic of China Air Force, nicknamed the Flying Tigers, was formed to help oppose the Japanese invasion of China. Operating in 1941–1942, it was composed of pilots from the United States ...

.

During the war, some 16,112,566 Americans served in the

United States Armed Forces

The United States Armed Forces are the military forces of the United States. The armed forces consists of six service branches: the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, Space Force, and Coast Guard. The president of the United States is ...

, with 405,399 killed and 671,278

wounded. There were also 130,201 American

prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of w ...

, of whom 116,129 returned home after the war. Key civilian advisors to President Roosevelt included

Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson

Henry Lewis Stimson (September 21, 1867 – October 20, 1950) was an American statesman, lawyer, and Republican Party politician. Over his long career, he emerged as a leading figure in U.S. foreign policy by serving in both Republican and ...

, who mobilized the nation's industries and induction centers to supply the

Army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

, commanded by

General

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". O ...

George Marshall and the

Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

under General

Hap Arnold

Henry Harley Arnold (June 25, 1886 – January 15, 1950) was an American general officer holding the ranks of General of the Army and later, General of the Air Force. Arnold was an aviation pioneer, Chief of the Air Corps (1938–1941), ...

. The

Navy

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and related functions. It in ...

, led by

Secretary of the Navy

The secretary of the Navy (or SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department (component organization) within the United States Department of Defense.

By law, the se ...

Frank Knox

William Franklin Knox (January 1, 1874 – April 28, 1944) was an American politician, newspaper editor and publisher. He was also the Republican vice presidential candidate in 1936, and Secretary of the Navy under Franklin D. Roosevelt during ...

and

Admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet ...

Ernest King, proved more autonomous. Overall priorities were set by Roosevelt and the

Joint Chiefs of Staff

The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) is the body of the most senior uniformed leaders within the United States Department of Defense, that advises the president of the United States, the secretary of defense, the Homeland Security Council and the ...

, chaired by

William Leahy. The highest priority was the defeat of Germany in Europe, but first the war against Japan in the Pacific was more urgent after the sinking of the main battleship fleet at

Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the Naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the ...

.

Admiral King put Admiral

Chester W. Nimitz

Chester William Nimitz (; February 24, 1885 – February 20, 1966) was a fleet admiral in the United States Navy. He played a major role in the naval history of World War II as Commander in Chief, US Pacific Fleet, and Commander in C ...

, based in Hawaii, in charge of the Pacific War against Japan. The

Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, when it was dissolved following Japan's surrender ...

had the advantage, taking the

Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

as well as British and Dutch possessions, and threatening Australia but in June 1942, its main carriers were sunk during the

Battle of Midway

The Battle of Midway was a major naval battle in the Pacific Theater of World War II that took place on 4–7 June 1942, six months after Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor and one month after the Battle of the Coral Sea. The U.S. Navy under ...

, and the Americans seized the initiative. The Pacific War became one of

island hopping, so as to move

air bases closer and closer to Japan. The Army, based in Australia under General

Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American military leader who served as General of the Army for the United States, as well as a field marshal to the Philippine Army. He had served with distinction in World War I, was ...

, steadily advanced across

New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; id, Papua, or , historically ) is the world's second-largest island with an area of . Located in Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is separated from Australia by the wide Torres ...

to the

Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, with plans to invade the Japanese home islands in late 1945. With its merchant fleet sunk by American submarines, Japan ran short of aviation gasoline and fuel oil, as the US Navy in June 1944 captured islands within

bombing range of the Japanese home islands.

Strategic bombing

Strategic bombing is a military strategy used in total war with the goal of defeating the enemy by destroying its morale, its economic ability to produce and transport materiel to the theatres of military operations, or both. It is a systematica ...

directed by General

Curtis Lemay destroyed all the major Japanese cities, as the US

captured Okinawa after heavy losses in spring 1945. With the

atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

The United States detonated two atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945, respectively. The two bombings killed between 129,000 and 226,000 people, most of whom were civilians, and remain the onl ...

, the

Soviet invasion of Manchuria, and

an invasion of the home islands imminent,

Japan surrendered.

The war in Europe involved aid to Britain, her allies, and the Soviet Union, with the US supplying munitions until it could ready an invasion force. US forces were first tested to a limited degree in the

North African Campaign and then employed more significantly with

British Forces in

Italy in 1943–45, where US forces, representing about a third of the

Allied forces deployed, bogged down after

Italy surrendered and the Germans took over. Finally the main

invasion of France took place in June 1944, under General

Dwight D. Eisenhower. Meanwhile, the

US Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

and the

British Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

engaged in the area bombardment of German cities and systematically targeted German transportation links and synthetic oil plants, as it knocked out what was left of the

Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German '' Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the '' Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabt ...

post

Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain, also known as the Air Battle for England (german: die Luftschlacht um England), was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defende ...

in 1945. Being invaded from all sides, it became clear that Germany would lose the war. Berlin

fell to the Soviets in May 1945, and with

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

dead, the

Germans surrendered.

The American victorious military effort was strongly supported by

civilians on the home front, who provided the military personnel, the munitions, the money, and the morale to fight the war to victory. World War II cost the United States an estimated $341 billion in 1945 dollars – equivalent to 74% of America's

GDP and expenditures during the war. In 2020 dollars, the war cost over $4.9 trillion.

Origins

American public opinion was hostile to the Axis, but how much aid to give the Allies was controversial. The United States returned to its typical

isolationist

Isolationism is a political philosophy advocating a national foreign policy that opposes involvement in the political affairs, and especially the wars, of other countries. Thus, isolationism fundamentally advocates neutrality and opposes entan ...

foreign policy after the

First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

and President

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

's failure to have the

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1 ...

ratified. Although President

Franklin D. Roosevelt personally favored a more assertive foreign policy, his administration remained committed to isolationism during the 1930s to ensure

congressional support for the

New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Con ...

, and allowed Congress to pass the

Neutrality Acts. As a result, the United States played no role in the

Second Italo-Ethiopian War

The Second Italo-Ethiopian War, also referred to as the Second Italo-Abyssinian War, was a war of aggression which was fought between Fascist Italy (1922–1943), Italy and Ethiopian Empire, Ethiopia from October 1935 to February 1937. In Ethio ...

and the

Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlism, Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebeli ...

. After the

German invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week afte ...

and the beginning of the war in September 1939, Congress allowed foreign countries to purchase war

materiel

Materiel (; ) refers to supplies, equipment, and weapons in military supply-chain management, and typically supplies and equipment in a commercial supply chain context.

In a military context, the term ''materiel'' refers either to the spec ...

from the United States on a "

cash-and-carry" basis, but assistance to the United Kingdom was still limited by British hard currency shortages and the

Johnson Act, and President Roosevelt's military advisers believed that the Allied Powers would be defeated and that US military assets should be focused on defending the

Western Hemisphere

The Western Hemisphere is the half of the planet Earth that lies west of the prime meridian (which crosses Greenwich, London, United Kingdom) and east of the antimeridian. The other half is called the Eastern Hemisphere. Politically, the te ...

.

By 1940 the US, while still neutral, was becoming the "

Arsenal of Democracy" for the Allies, supplying money and war materials. Prime Minister

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

and President Roosevelt agreed to exchange 50 US

destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed ...

s for 99-year-leases to British military bases in

Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

and the

Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean ...

. The

sudden defeat of France in spring 1940 caused the nation to begin to expand its armed forces, including the first

peacetime draft. In preparation for expected German aggression against the Soviet Union, negotiations for better diplomatic relations began between

Undersecretary of State Sumner Welles

Benjamin Sumner Welles (October 14, 1892September 24, 1961) was an American government official and diplomat in the Foreign Service. He was a major foreign policy adviser to President Franklin D. Roosevelt and served as Under Secretary of Sta ...

and

Soviet Ambassador to the United States Konstantin Umansky

Konstantin Aleksandrovich Umansky (russian: Kонстантин Aлександрович Уманский; 14 May 1902 – 25 January 1945) was a Soviet diplomat, editor, journalist and artist.

Biography and career

Umansky, who was Jewish, ...

.

After the

German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, America began sending

Lend Lease

Lend-Lease, formally the Lend-Lease Act and introduced as An Act to Promote the Defense of the United States (), was a policy under which the United States supplied the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union and other Allied nations with food, oil, ...

aid to the Soviet Union as well as Britain and China. Although President Franklin D. Roosevelt's advisers warned that the Soviet Union would collapse from the Nazi advance within weeks, he barred Congress from blocking aid to the Soviet Union on the advice of

Harry Hopkins

Harry Lloyd Hopkins (August 17, 1890 – January 29, 1946) was an American statesman, public administrator, and presidential advisor. A trusted deputy to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Hopkins directed New Deal relief programs before servi ...

.

In August 1941, President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill met aboard the

''USS Augusta'' at

Naval Station Argentia in

Placentia Bay

Placentia Bay (french: Baie de Plaisance) is a body of water on the southeast coast of Newfoundland, Canada. It is formed by Burin Peninsula on the west and Avalon Peninsula on the east. Fishing grounds in the bay were used by native people long ...

,

Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

, and produced the

Atlantic Charter

The Atlantic Charter was a statement issued on 14 August 1941 that set out American and British goals for the world after the end of World War II. The joint statement, later dubbed the Atlantic Charter, outlined the aims of the United States and ...

outlining mutual aims for a postwar liberalized international system.

Public opinion was even more hostile to Japan, and there was little opposition to increased support for China. After the 1931

Japanese invasion of Manchuria, the United States articulated the

Stimson Doctrine, named for

Secretary of State Henry L. Stimson

Henry Lewis Stimson (September 21, 1867 – October 20, 1950) was an American statesman, lawyer, and Republican Party politician. Over his long career, he emerged as a leading figure in U.S. foreign policy by serving in both Republican and ...

, stating that no territory conquered by military force would be recognized. The United States also withdrew from the

Washington Naval Treaty limiting naval tonnage in response to Japan's violations of the

Nine-Power Treaty and the

Kellogg–Briand Pact

The Kellogg–Briand Pact or Pact of Paris – officially the General Treaty for Renunciation of War as an Instrument of National Policy – is a 1928 international agreement on peace in which signatory states promised not to use war to ...

. Public opposition to

Japanese expansionism in Asia had mounted during the

Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific T ...

when the

Imperial Japanese Army Air Service attacked and sank the US

Yangtze Patrol gunboat in the

Yangtze

The Yangtze or Yangzi ( or ; ) is the longest river in Asia, the third-longest in the world, and the longest in the world to flow entirely within one country. It rises at Jari Hill in the Tanggula Mountains (Tibetan Plateau) and flows ...

River while the ship was evacuating civilians from the

Nanjing Massacre

The Nanjing Massacre (, ja, 南京大虐殺, Nankin Daigyakusatsu) or the Rape of Nanjing (formerly romanized as ''Nanking'') was the mass murder of Chinese civilians in Nanjing, the capital of the Republic of China, immediately after the ...

''.'' Although the US government accepted Japanese official apologies and indemnities for the incident, it resulted in increasing trade restrictions against Japan and corresponding increases US credit and aid to China. After the United States abrogated the 1911 Treaty of Commerce and Navigation with Japan, Japan ratified the

Tripartite Pact

The Tripartite Pact, also known as the Berlin Pact, was an agreement between Germany, Italy, and Japan signed in Berlin on 27 September 1940 by, respectively, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Galeazzo Ciano and Saburō Kurusu. It was a defensive milit ...

and embarked on an

invasion of French Indochina. The United States responded by placing a complete

embargo on Japan through the

Export Control Act of 1940,

freezing

Freezing is a phase transition where a liquid turns into a solid when its temperature is lowered below its freezing point. In accordance with the internationally established definition, freezing means the solidification phase change of a liquid ...

Japanese bank accounts, halting negotiations with Japanese diplomats, and supplying China through the

Burma Road

The Burma Road () was a road linking Burma (now known as Myanmar) with southwest China. Its terminals were Kunming, Yunnan, and Lashio, Burma. It was built while Burma was a British colony to convey supplies to China during the Second S ...

.

American volunteers

Before America entered World War II in December 1941, individual Americans volunteered to fight against the Axis powers in other nations' armed forces. Although under American law, it was illegal for United States citizens to join the armed forces of foreign nations, and in doing so, they lost their

citizenship

Citizenship is a "relationship between an individual and a state to which the individual owes allegiance and in turn is entitled to its protection".

Each state determines the conditions under which it will recognize persons as its citizens, and ...

, many American volunteers changed their nationality to

Canadian

Canadians (french: Canadiens) are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of ...

. However, Congress passed a blanket pardon in 1944.

American mercenary Colonel

Charles Sweeny

Charles Michael Sweeny (January 26, 1882 – February 27, 1963) was an American soldier of fortune, United States Army lieutenant colonel, French Foreign Legion officer, Polish army brigadier general, Royal Air Force (RAF) group captain, ...

began recruiting American citizens to fight as a US volunteer detachment in the

French Air Force

The French Air and Space Force (AAE) (french: Armée de l'air et de l'espace, ) is the air and space force of the French Armed Forces. It was the first military aviation force in history, formed in 1909 as the , a service arm of the French Ar ...

, however France fell before this was implemented.

During the

Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain, also known as the Air Battle for England (german: die Luftschlacht um England), was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defende ...

, 11 American pilots flew in the

Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) an ...

. Charles Sweeney's nephew, also named Charles, formed a

Home Guard unit from American volunteers living in London.

One notable example was the

Eagle Squadrons, which were

RAF squadrons made up of American volunteers and British personnel. The first to be formed was

No. 71 Squadron on 19 September 1940, followed by

No. 121 Squadron on 14 May 1941 and

No. 133 Squadron on 1 August 1941. 6,700 Americans applied to join but only 244 got to serve with the three Eagle squadrons; 16 Britons also served as squadron and flight commanders. The first became operational in February 1941 and the squadrons scored their first kill in July 1941. On 29 September 1942, the three squadrons were officially turned over by the RAF to the

Eighth Air Force

The Eighth Air Force (Air Forces Strategic) is a numbered air force (NAF) of the United States Air Force's Air Force Global Strike Command (AFGSC). It is headquartered at Barksdale Air Force Base, Louisiana. The command serves as Air Forc ...

of the

US Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

and became the

4th Fighter Group

The 4th Fighter Group was an American element of the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) Eighth Air Force during World War II. The group was known as the Debden Eagles because it was created from the three Eagle Squadrons of the Royal Air Force: ...

. In their time with the RAF the squadrons claim to have shot 73½ German planes; 77 Americans and 5 Britons were killed.

Another notable example was the

Flying Tigers

The First American Volunteer Group (AVG) of the Republic of China Air Force, nicknamed the Flying Tigers, was formed to help oppose the Japanese invasion of China. Operating in 1941–1942, it was composed of pilots from the United States ...

, created by

Claire L. Chennault, a retired

US Army Air Corps

The United States Army Air Corps (USAAC) was the aerial warfare service component of the United States Army between 1926 and 1941. After World War I, as early aviation became an increasingly important part of modern warfare, a philosophical r ...

officer working in the

Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northeas ...

since August 1937, first as

military aviation

Military aviation comprises military aircraft and other flying machines for the purposes of conducting or enabling aerial warfare, including national airlift ( air cargo) capacity to provide logistical supply to forces stationed in a war thea ...

advisor to

Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

in the early months of the

Sino-Japanese War. Officially known as the 1st American Volunteer Group (AVG) but nicknamed the "Flying Tigers", this was a group of American pilots already serving in the

US Armed forces and recruited under presidential authority. As a unit they served in the Chinese Air Force against the

Japanese. The group comprised three fighter squadrons of around 30 aircraft each. The AVG's first combat mission was on 20 December 1941, twelve days after the Pearl Harbor attack. On 4 July 1942 the AVG was disbanded, and was replaced by the

23rd Fighter Group of the

United States Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

, which was later absorbed into the US

Fourteenth Air Force

The Fourteenth Air Force (14 AF; Air Forces Strategic) was a numbered air force of the United States Air Force Space Command (AFSPC). It was headquartered at Vandenberg Air Force Base, California.

The command was responsible for the organiza ...

. During their time in the Chinese Air Force, they succeeded in destroying 296 enemy aircraft,

[Ford 1991, pp. 30–34.] while losing only 14 pilots in combat.

Command system

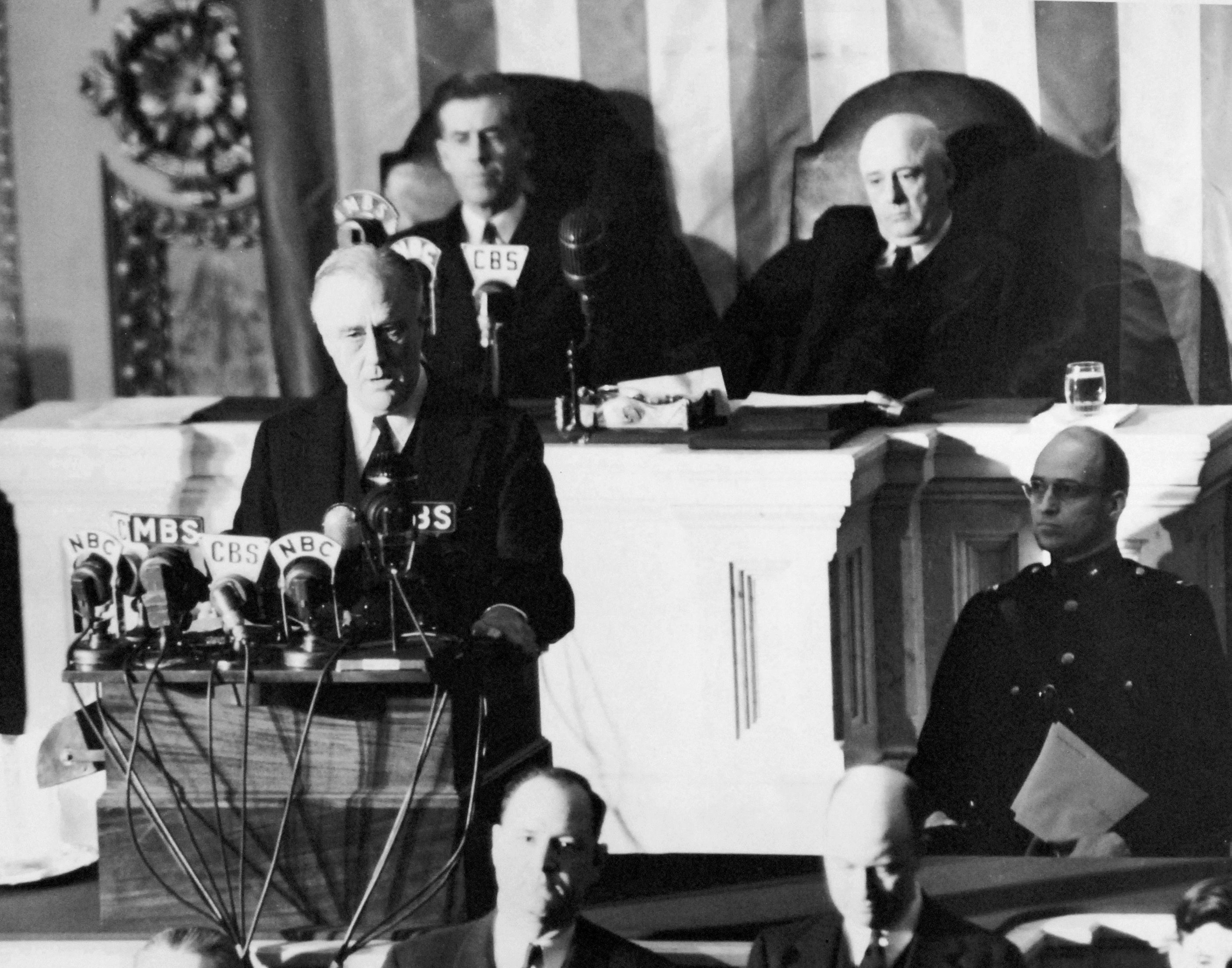

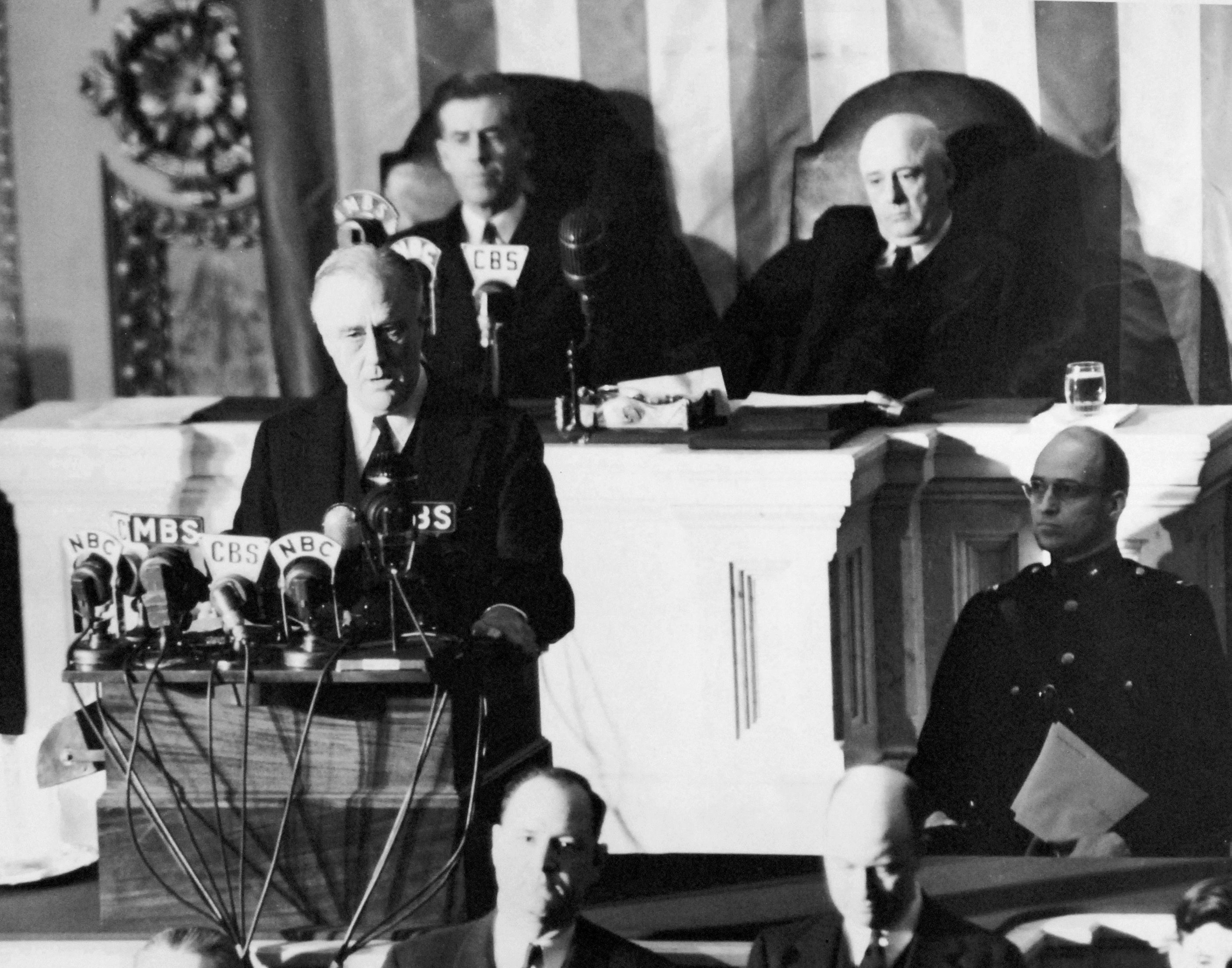

In 1942 President

Franklin D. Roosevelt set up a new command structure to provide leadership in the US Armed Forces while retaining authority as Commander-in-Chief as assisted by

Secretary of War Henry Stimson with Admiral

Ernest J. King as

Chief of Naval Operations

The chief of naval operations (CNO) is the professional head of the United States Navy. The position is a statutory office () held by an admiral who is a military adviser and deputy to the secretary of the Navy. In a separate capacity as a memb ...

in complete control of the

Navy

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and related functions. It in ...

and of the

Marine Corps through its Commandant, then Lt. General

Thomas Holcomb

General Thomas Holcomb (August 5, 1879 – May 24, 1965) was a United States Marine Corps officer who served as the seventeenth Commandant of the Marine Corps from 1936 to 1943. He was the first Marine to achieve the rank of general, and was a ...

and his successor as

Commandant of the Marine Corps

The commandant of the Marine Corps (CMC) is normally the highest-ranking officer in the United States Marine Corps and is a member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Joint Chiefs of Staff: composition; functions. The CMC reports directly to the secr ...

, Lt. General

Alexander Vandegrift, General

George C. Marshall in charge of the

Army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

, and in nominal control of the Air Force, which in practice was commanded by General

Hap Arnold

Henry Harley Arnold (June 25, 1886 – January 15, 1950) was an American general officer holding the ranks of General of the Army and later, General of the Air Force. Arnold was an aviation pioneer, Chief of the Air Corps (1938–1941), ...

on Marshall's behalf. King was also in control for wartime being of the

US Coast Guard

The United States Coast Guard (USCG) is the maritime security, search and rescue, and law enforcement service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the country's eight uniformed services. The service is a maritime, military, multi ...

under its Commandant, Admiral

Russell R. Waesche

Russell may refer to:

People

* Russell (given name)

* Russell (surname)

* Lady Russell (disambiguation)

* Lord Russell (disambiguation)

Places Australia

*Russell, Australian Capital Territory

* Russell Island, Queensland (disambiguation)

**R ...

. Roosevelt formed a new body, the

Joint Chiefs of Staff

The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) is the body of the most senior uniformed leaders within the United States Department of Defense, that advises the president of the United States, the secretary of defense, the Homeland Security Council and the ...

, which made the final decisions on American military strategy and as the chief policy-making body for the armed forces. The Joint Chiefs was a White House agency chaired by Admiral

William D. Leahy, who became FDR's chief military advisor and the highest military officer of the US at that time.

As the war progressed Marshall became the dominant voice in the JCS in the shaping of strategy. When dealing with Europe, the Joint Chiefs met with their British counterparts and formed the

Combined Chiefs of Staff

The Combined Chiefs of Staff (CCS) was the supreme military staff for the United States and Britain during World War II. It set all the major policy decisions for the two nations, subject to the approvals of British Prime Minister Winston Church ...

. Unlike the political leaders of the other major powers, Roosevelt rarely overrode his military advisors. The civilians handled the draft and procurement of men and equipment, but no civilians—not even the secretaries of War or Navy, had a voice in strategy. Roosevelt avoided the

State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs of other na ...

and conducted high-level diplomacy through his aides, especially

Harry Hopkins

Harry Lloyd Hopkins (August 17, 1890 – January 29, 1946) was an American statesman, public administrator, and presidential advisor. A trusted deputy to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Hopkins directed New Deal relief programs before servi ...

. Since Hopkins also controlled $50 billion in

Lend Lease

Lend-Lease, formally the Lend-Lease Act and introduced as An Act to Promote the Defense of the United States (), was a policy under which the United States supplied the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union and other Allied nations with food, oil, ...

funds given to the Allies, they paid attention to him.

Lend-Lease and Iceland Occupation

The year 1940 marked a change in attitude in the United States. The

German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

victories in

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

,

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

and elsewhere, combined with the

Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain, also known as the Air Battle for England (german: die Luftschlacht um England), was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defende ...

, led many Americans to believe that some intervention would be needed. In March 1941, the

Lend-Lease

Lend-Lease, formally the Lend-Lease Act and introduced as An Act to Promote the Defense of the United States (), was a policy under which the United States supplied the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union and other Allied nations with food, oil, ...

program began shipping money, munitions, and food to Britain, China, and (by that fall) the Soviet Union.

By 1941 the United States was taking an active part in the war, despite its nominal neutrality. In spring

U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare ro ...

s began their "wolf-pack" tactics which threatened to sever the trans- Atlantic supply line; Roosevelt extended the

Pan-American Security Zone east almost as far as

Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its ...

. The US Navy's "neutrality patrols" were not actually neutral as, in practice, their function was to report Axis ship and submarine sightings to the British and Canadian navies, and from April the US Navy began escorting Allied convoys from Canada as far as the "Mid-Atlantic Meeting Point" (MOMP) south of Iceland, where they handed off to the RN.

On 16 June 1941, after negotiation with

Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from 1 ...

, Roosevelt ordered the United States occupation of Iceland to replace the

British invasion forces. On 22 June 1941, the US Navy sent Task Force 19 (TF 19) from

Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina, the county seat of Charleston County, and the principal city in the Charleston–North Charleston metropolitan area. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint o ...

to assemble at

Argentia, Newfoundland

Argentia ( ) is a Canadian commercial seaport and industrial park located in the Town of Placentia, Newfoundland and Labrador. It is situated on the southwest coast of the Avalon Peninsula and defined by a triangular shaped headland which re ...

. TF 19 included

25 warships and the

1st Provisional Marine Brigade of 194 officers and 3714 men from

San Diego, California

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the eighth most populous city in the United Stat ...

under the command of Brigadier General John Marston.

Task Force 19 (TF 19) sailed from Argentia on 1 July. On 7 July, Britain persuaded the

Althing

The Alþingi (''general meeting'' in Icelandic, , anglicised as ' or ') is the supreme national parliament of Iceland. It is one of the oldest surviving parliaments in the world. The Althing was founded in 930 at (" thing fields" or "assemb ...

to approve an American occupation force under a US-Icelandic defense agreement, and TF 19 anchored off Reykjavík that evening.

US Marines

The United States Marine Corps (USMC), also referred to as the United States Marines, is the maritime land force service branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for conducting expeditionary and amphibious operations through comb ...

commenced landing on 8 July, and disembarkation was completed on 12 July. On 6 August, the

US Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

established an air base at Reykjavík with the arrival of Patrol Squadron VP-73

PBY Catalina

The Consolidated PBY Catalina is a flying boat and amphibious aircraft that was produced in the 1930s and 1940s. In Canadian service it was known as the Canso. It was one of the most widely used seaplanes of World War II. Catalinas served w ...

s and VP-74

PBM Mariners.

US Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

personnel began arriving in Iceland in August, and the Marines had been transferred to the Pacific by March 1942.

Up to 40,000 US military personnel were stationed on the island, outnumbering adult Icelandic men (at the time, Iceland had a population of about 120,000.) The agreement was for the US military to remain until the end of the war (although the US military presence in Iceland

remained through 2006, as postwar Iceland became a member of

NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two N ...

).

American warships escorting Allied convoys in the western Atlantic had several hostile encounters with U-boats. On 4 September, a German U-Boat attacked the destroyer off Iceland. A week later Roosevelt ordered American warships to attack U-boats on sight. A U-boat shot up the as it escorted a British merchant convoy. The was sunk by on 31 October 1941.

European and North African Theaters

On 11 December 1941, three days after the United States

declared war on Japan,

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

and Nazi Germany

declared war against the United States. That same day, the United States

declared war on Germany and

Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

.

Europe first

The established grand strategy of the Allies was to defeat Germany and its allies in Europe first, and then focus could shift towards Japan in the Pacific. This was because two of the Allied capitals, London and

Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

, could be directly threatened by Germany, but none of the major Allied capitals were threatened by Japan.

Germany was the United Kingdom's primary threat, especially after the Fall of France in 1940, which saw Germany overrun most of the countries of

Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

, leaving the United Kingdom alone to combat Germany. Germany's planned invasion of the UK, Operation Sea Lion, was averted by its failure to establish air superiority in the Battle of Britain. At the same time, war with Japan in East Asia seemed increasingly likely. Although the US was not yet at war with either Germany or Japan, it met with the UK on several occasions to formulate joint strategies.

In the 29 March 1941 report of the

ABC-1 conference, the Americans and British agreed that their strategic objectives were: (1) "The early defeat of Germany as the predominant member of the Axis with the principal military effort of the United States being exerted in the Atlantic and European area; and (2) A strategic defensive in the

Far East

The ''Far East'' was a European term to refer to the geographical regions that includes East and Southeast Asia as well as the Russian Far East to a lesser extent. South Asia is sometimes also included for economic and cultural reasons.

The t ...

."

Thus, the Americans concurred with the British in the grand strategy of "Europe first" (or "Germany first") in carrying out military operations in World War II. The UK feared that, if the United States was diverted from its main focus in Europe to the Pacific (Japan), Hitler might crush both the Soviet Union and Britain, and would then become an unconquerable fortress in Europe. The wound inflicted on the United States by Japan at Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, did not result in a change in US policy. Prime Minister Winston Churchill hastened to Washington shortly after Pearl Harbor for the Arcadia Conference to ensure that the Americans didn't have second thoughts about Europe First. The two countries reaffirmed that, "notwithstanding the entry of Japan into the War, our view remains that Germany is still the prime enemy. And her defeat is the key to victory. Once Germany is defeated the collapse of Italy and the defeat of Japan must follow."

Battle of the Atlantic

The Battle of the Atlantic was the longest continuous military campaign in World War II, running from 1939 to the defeat of Germany in 1945. At its core was the

Allied naval blockade of Germany, announced the day after the declaration of war, and Germany's subsequent counter-blockade. It was at its height from mid-1940 through to the end of 1943. The Battle of the Atlantic pitted U-boats and other warships of the

Kriegsmarine

The (, ) was the navy of Germany from 1935 to 1945. It superseded the Imperial German Navy of the German Empire (1871–1918) and the inter-war (1919–1935) of the Weimar Republic. The was one of three official branches, along with the a ...

(German navy) and aircraft of the

Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German '' Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the '' Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabt ...

(German Air Force) against the Royal Canadian Navy, Royal Navy, the United States Navy, and Allied merchant shipping. The convoys, coming mainly from

North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and th ...

and predominantly going to the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union, were protected for the most part by the British and Canadian navies and air forces. These forces were aided by ships and aircraft of the United States from 13 September 1941. The Germans were joined by submarines of the

Italian Royal Navy (Regia Marina) after their Axis ally Italy entered the war on 10 June 1940.

Operation Torch

The United States entered the war in the west with

Operation Torch

Operation Torch (8 November 1942 – 16 November 1942) was an Allied invasion of French North Africa during the Second World War. Torch was a compromise operation that met the British objective of securing victory in North Africa while al ...

on 8 November 1942, after their Soviet allies had pushed for a second

front against the Germans. General

Dwight Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War I ...

commanded the assault on

North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

, and Major General

George Patton

George Smith Patton Jr. (November 11, 1885 – December 21, 1945) was a general in the United States Army who commanded the Seventh United States Army in the Mediterranean Theater of World War II, and the Third United States Army in France ...

struck at

Casablanca

Casablanca, also known in Arabic as Dar al-Bayda ( ar, الدَّار الْبَيْضَاء, al-Dār al-Bayḍāʾ, ; ber, ⴹⴹⴰⵕⵍⴱⵉⴹⴰ, ḍḍaṛlbiḍa, : "White House") is the largest city in Morocco and the country's econom ...

.

Allied victory in North Africa

The United States did not have a smooth entry into the war against

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

. Early in 1943, the

United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, ...

suffered a near-disastrous defeat at the

Battle of the Kasserine Pass

The Battle of Kasserine Pass was a series of battles of the Tunisian campaign of World War II that took place in February 1943 at Kasserine Pass, a gap in the Grand Dorsal chain of the Atlas Mountains in west central Tunisia.

The Axis forces, ...

in February. The senior Allied leadership was primarily to blame for the loss as internal bickering between American General

Lloyd Fredendall and the British led to mistrust and little communication, causing inadequate troop placements. The defeat could be considered a major turning point, however, because General Eisenhower replaced Fredendall with General Patton.

Slowly the Allies stopped the German advance in

Tunisia

)

, image_map = Tunisia location (orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption = Location of Tunisia in northern Africa

, image_map2 =

, capital = Tunis

, largest_city = capital

, ...

and by March were pushing back. In mid-April, under British General

Bernard Montgomery, the Allies smashed through the

Mareth Line

The Mareth Line was a system of fortifications built by France in southern Tunisia in the late 1930s. The line was intended to protect Tunisia against an Italian invasion from its colony in Libya. The line occupied a point where the routes into T ...

and broke the Axis defense in North Africa. On 13 May 1943, Axis troops in North Africa surrendered, leaving behind 275,000 men. Allied efforts turned towards Sicily and Italy.

Invasion of Sicily and Italy

The first stepping stone for the Allied liberation of Europe was invading Europe through Italy. Launched on 9 July 1943, Operation Husky was, at the time, the largest

amphibious operation ever undertaken. The American seaborne assault by the

US 7th Army

The Seventh Army was a United States army created during World War II that evolved into the United States Army Europe (USAREUR) during the 1950s and 1960s. It served in North Africa and Italy in the Mediterranean Theater of Operations and Fran ...

landed on the southern coast of Sicily between the town of Licata in the west, and Scoglitti in the east and units of the 82nd airborne division parachuted ahead of landings. Despite the elements, the operation was a success and the Allies immediately began exploiting their gains. On 11 August, seeing that the battle was lost, the German and Italian commanders began evacuating their forces from Sicily to Italy. On 17 August, the Allies were in control of the island, US 7th Army lost 8,781 men (2,237 killed or missing, 5,946 wounded, and 598 captured).

Following the Allied victory in Sicily, Italian public sentiment swung against the war and Italian dictator

Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

. He was dismissed from office by the

Fascist Grand Council

The Grand Council of Fascism (, also translated "Fascist Grand Council") was the main body of Mussolini's Fascist government in Italy, that held and applied great power to control the institutions of government. It was created as a body of the ...

and

King Victor Emmanuel III

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the tit ...

, and the Allies struck quickly, hoping resistance would be slight. The first Allied troops landed on the Italian peninsula on 3 September 1943 and Italy surrendered on 8 September, however the

Italian Social Republic was established soon afterwards. The first American troops landed at Salerno on 9 September 1943, by

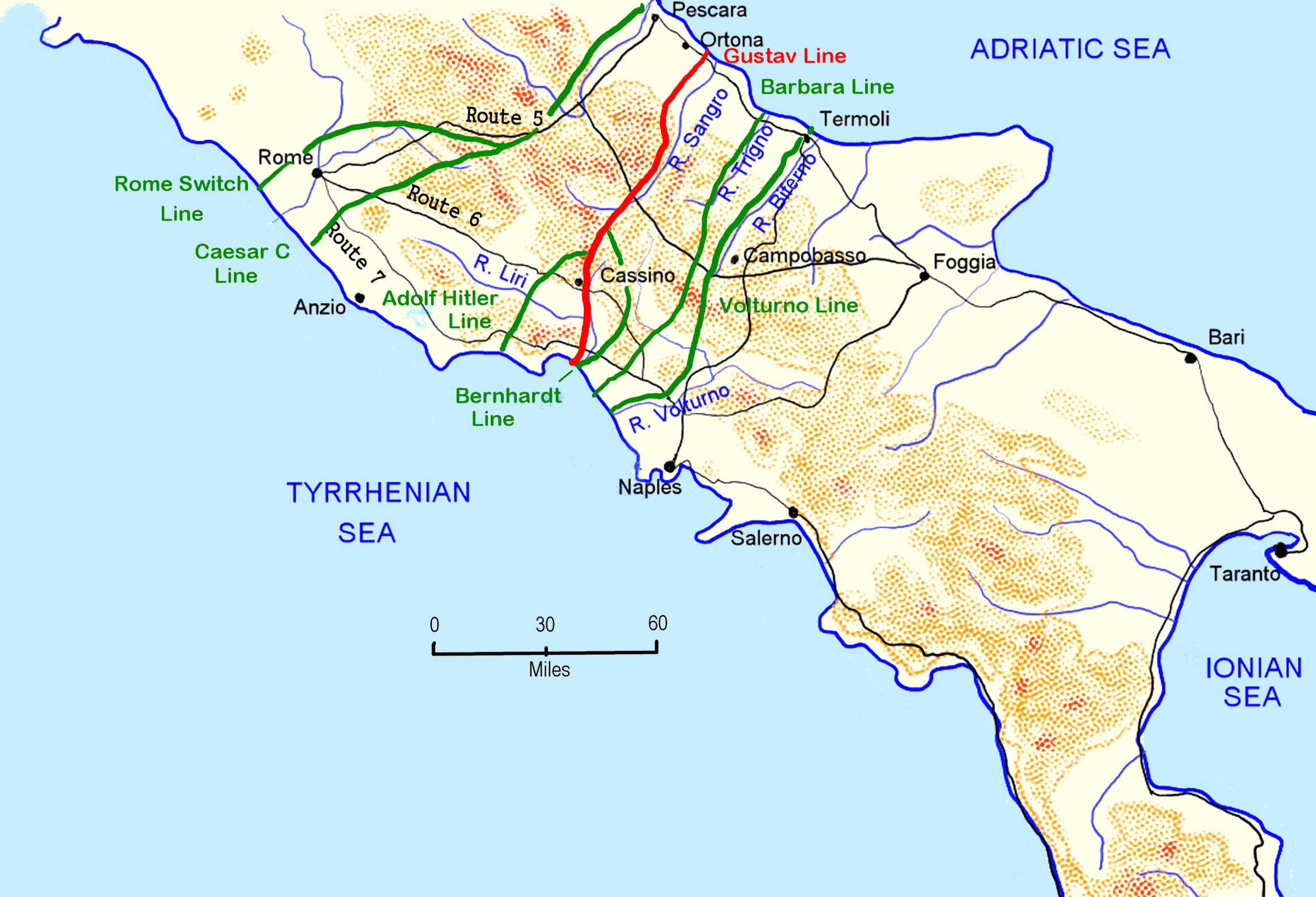

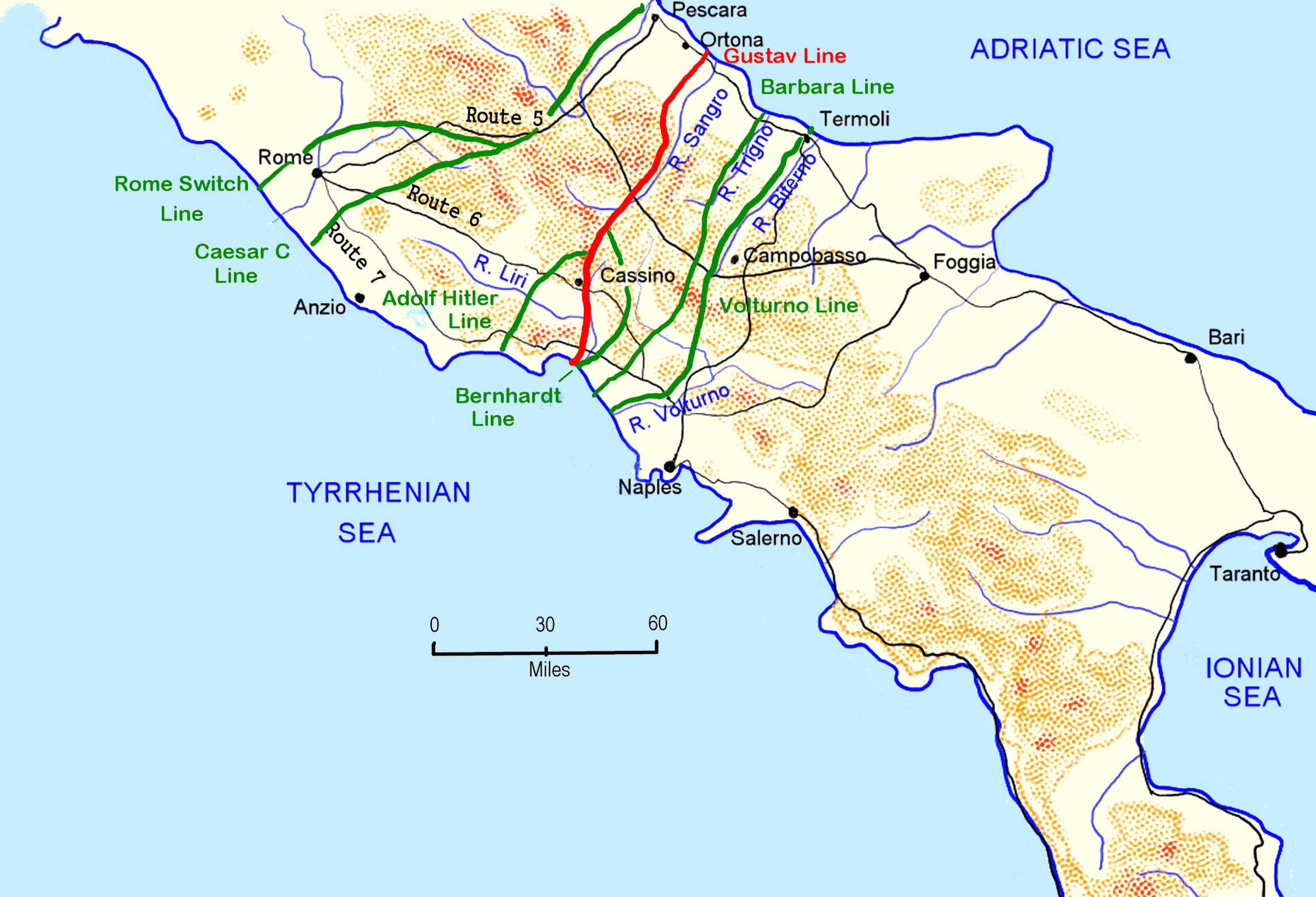

U.S. Fifth Army. However, German troops in Italy were prepared, and after the Allied troops at Salerno had consolidated their beachhead, the Germans launched fierce counterattacks. However, they failed to destroy the beachhead and retreated on 16 September and in October 1943 began preparing a series of defensive lines across central Italy. The US 5th Army and other Allied armies broke through the first two lines (

Volturno

The Volturno (ancient Latin name Volturnus, from ''volvere'', to roll) is a river in south-central Italy.

Geography

It rises in the Abruzzese central Apennines of Samnium near Castel San Vincenzo (province of Isernia, Molise) and flows southe ...

and the

Barbara Line) in October and November 1943. As winter approached, the Allies made slow progress due to the weather and the difficult terrain against the heavily defended German Winter Line; they did however manage to break through the

Bernhardt Line

The Bernhardt Line (or Reinhard Line) was a German defensive line in Italy during the Italian Campaign of World War II. Having reached the Bernhardt Line at the start of December 1943, it took until mid-January 1944 for the U.S. Fifth Army to fig ...

in January 1944. By early 1944 the Allied attention had turned to the western front and the Allies were taking heavy losses trying to break through the Winter Line at

Monte Cassino

Monte Cassino (today usually spelled Montecassino) is a rocky hill about southeast of Rome, in the Latin Valley, Italy, west of Cassino and at an elevation of . Site of the Roman town of Casinum, it is widely known for its abbey, the first h ...

. The Allies landed at

Anzio

Anzio (, also , ) is a town and ''comune'' on the coast of the Lazio region of Italy, about south of Rome.

Well known for its seaside harbour setting, it is a Port, fishing port and a departure point for ferries and hydroplanes to the Pontine I ...

on 22 January 1944 to outflank the Gustav line and pull Axis forces out of it so other allied armies could breakthrough. After slow progress, the Germans counterattacked in February but failed to stamp out the Allies; after months of stalemate, the Allies broke out in May 1944 and Rome fell to the Allies on 4 June 1944.

Following the Normandy invasion on 6 June 1944, the equivalent of seven US and French divisions were pulled out of Italy to participate in Operation Dragoon: the allied landings in southern France; despite this, the remaining US forces in Italy with other Allied forces pushed up to the

Gothic line in northern Italy, the last major defensive line. From August 1944 to March 1945 the Allies managed to breach the formidable defenses but they narrowly failed to break out into the Lombardy Plains before the winter weather closed in and made further progress impossible. In April 1945 the Allies broke through the remaining Axis positions in

Operation Grapeshot

The spring 1945 offensive in Italy, codenamed Operation Grapeshot, was the final Allied attack during the Italian Campaign in the final stages of the Second World War. The attack into the Lombard Plain by the 15th Allied Army Group started on ...

ending the Italian Campaign on 2 May 1945; US forces in mainland Italy suffered between 114,000 and over 119,000 casualties.

Strategic bombing

Numerous bombing runs were launched by the United States aimed at the industrial heart of Germany. Using the high altitude

B-17

The Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress is a four-engined heavy bomber developed in the 1930s for the United States Army Air Corps (USAAC). Relatively fast and high-flying for a bomber of its era, the B-17 was used primarily in the European Theater ...

and

B-24

The Consolidated B-24 Liberator is an American heavy bomber, designed by Consolidated Aircraft of San Diego, California. It was known within the company as the Model 32, and some initial production aircraft were laid down as export models des ...

, the raids had to be conducted in daylight for the drops to be accurate. As adequate fighter escort was rarely available, the bombers would fly

in tight, box formations, allowing each bomber to provide overlapping

machine-gun

A machine gun is a automatic firearm, fully automatic, rifling, rifled action (firearms)#Autoloading operation, autoloading firearm designed for sustained direct fire with rifle cartridges. Other automatic firearms such as Automatic shotgun, a ...

fire for defense. The tight formations made it impossible to evade fire from ''

Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German '' Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the '' Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabt ...

'' fighters, however, and American bomber crew losses were high. One such example was the

Schweinfurt-Regensburg mission, which resulted in staggering losses of men and equipment. The introduction of the revered

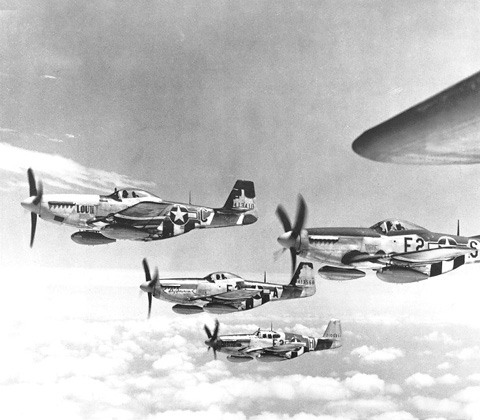

P-51 Mustang, which had enough fuel to make a round trip to Germany's heartland, helped to reduce losses later in the war.

In mid-1942, the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) arrived in the UK and carried out a few raids across the

English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

. The USAAF

Eighth Air Force

The Eighth Air Force (Air Forces Strategic) is a numbered air force (NAF) of the United States Air Force's Air Force Global Strike Command (AFGSC). It is headquartered at Barksdale Air Force Base, Louisiana. The command serves as Air Forc ...

's B-17 bombers were called the "Flying Fortresses" because of their heavy defensive armament of ten to twelve machine guns, and armor plating in vital locations. In part because of their heavier armament and armor, they carried smaller bomb loads than British bombers. With all of this, the USAAF's commanders in Washington, DC, and in Great Britain adopted the strategy of taking on the Luftwaffe head-on, in larger and larger air raids by mutually defending bombers, flying over Germany, Austria, and France at high altitudes during the daytime. Also, both the US Government and its Army Air Forces commanders were reluctant to bomb enemy cities and towns indiscriminately. They claimed that by using the B-17 and the

Norden bombsight

The Norden Mk. XV, known as the Norden M series in U.S. Army service, is a bombsight that was used by the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) and the United States Navy during World War II, and the United States Air Force in the Korean and t ...

, the USAAF should be able to carry out "precision bombing" on locations vital to the German war machine: factories,

naval bases,

shipyard

A shipyard, also called a dockyard or boatyard, is a place where ships are built and repaired. These can be yachts, military vessels, cruise liners or other cargo or passenger ships. Dockyards are sometimes more associated with maintenance a ...

s, railroad yards, railroad junctions, power plants, steel mills, airfields, etc.

In January 1943, at the

Casablanca Conference

The Casablanca Conference (codenamed SYMBOL) or Anfa Conference was held at the Anfa Hotel in Casablanca, French Morocco, from January 14 to 24, 1943, to plan the Allied European strategy for the next phase of World War II. In attendance were ...

, it was agreed

RAF Bomber Command

RAF Bomber Command controlled the Royal Air Force's bomber forces from 1936 to 1968. Along with the United States Army Air Forces, it played the central role in the strategic bombing of Germany in World War II. From 1942 onward, the British bo ...

operations against Germany would be reinforced by the USAAF in a Combined Operations Offensive plan called Operation Pointblank. Chief of the British Air Staff MRAF Sir

Charles Portal

Marshal of the Royal Air Force Charles Frederick Algernon Portal, 1st Viscount Portal of Hungerford, (21 May 1893 – 22 April 1971) was a senior Royal Air Force officer. He served as a bomber pilot in the First World War, and rose to become fi ...

was put in charge of the "strategic direction" of both British and American bomber operations. The text of the Casablanca directive read: "Your primary object will be the progressive destruction and dislocation of the German military, industrial and economic system and the undermining of the morale of the German people to a point where their capacity for armed resistance is fatally weakened.", At the beginning of the combined strategic bombing offensive on 4 March 1943 669 RAF and 303 USAAF heavy bombers were available.

In late 1943, 'Pointblank' attacks manifested themselves in the infamous Schweinfurt raids (first and second). Formations of unescorted bombers were no match for German fighters, which inflicted a deadly toll. In despair, the Eighth halted air operations over Germany until a long-range fighter could be found in 1944; it proved to be the P-51 Mustang, which had the range to fly to Berlin and back.

USAAF leaders firmly held to the claim of "precision bombing" of military targets for much of the war, and dismissed claims they were simply bombing cities. However, the American Eighth Air Force received the first

H2X radar

H2X, officially known as the AN/APS-15, was an American ground scanning radar system used for blind bombing during World War II. It was a development of the British H2S radar, the first ground mapping radar to be used in combat. It was also know ...

sets in December 1943. Within two weeks of the arrival of these first six sets, the Eighth command permitted them to area bomb a city using H2X and would continue to authorize, on average, about one such attack a week until the end of the war in Europe.

In reality, the day bombing was "precision bombing" only in the sense that most bombs fell somewhere near a specific designated target such as a railway yard. Conventionally, the air forces designated as "the target area" a circle having a radius of 1000 feet around the aiming point of attack. While accuracy improved during the war, Survey studies show that, overall, only about 20% of the bombs aimed at precision targets fell within this target area. In the fall of 1944, only seven percent of all bombs dropped by the Eighth Air Force hit within 1,000 feet of their aim point. The only offensive ordnance possessed by the USAAF that was guidable, the VB-1

Azon, saw very limited service in Europe and in the

CBI Theater

China Burma India Theater (CBI) was the United States military designation during World War II for the China and Southeast Asian or India–Burma (IBT) theaters. Operational command of Allied forces (including U.S. forces) in the CBI was offi ...

late in the war.

Nevertheless, the sheer tonnage of explosives delivered by day and by night was eventually enough to cause widespread damage, and, more importantly from a military point of view, forced Germany to divert resources to counter it. This was to be the real significance of the Allied strategic bombing campaign—resource allocation.

To improve USAAF fire bombing capabilities a mock-up German village was built and repeatedly burned down. It contained full-scale replicas of German homes. Fire bombing attacks proved successful, in a single 1943 attack on Hamburg about 50,000 civilians were killed and almost the entire city destroyed.

With the arrival of the brand-new

Fifteenth Air Force, based in Italy, command of the US Air Forces in Europe was consolidated into the

United States Strategic Air Forces

The United States Strategic Air Forces (USSTAF) was a formation of the United States Army Air Forces. It became the overall command and control authority of the United States Army Air Forces in Europe during World War II.

USSTAF had started as ...

(USSAF). With the addition of the Mustang to its strength, the Combined Bomber Offensive was resumed. Planners targeted the Luftwaffe in an operation known as '

Big Week' (20–25 February 1944) and succeeded brilliantly – losses were so heavy German planners were forced into a hasty dispersal of industry and the day fighter arm never fully recovered.

The dismissal of General

Ira Eaker

General (Honorary) Ira Clarence Eaker (April 13, 1896 – August 6, 1987) was a general of the United States Army Air Forces during World War II. Eaker, as second-in-command of the prospective Eighth Air Force, was sent to England to form and ...

at the end of 1943 as commander of the

Eighth Air Force

The Eighth Air Force (Air Forces Strategic) is a numbered air force (NAF) of the United States Air Force's Air Force Global Strike Command (AFGSC). It is headquartered at Barksdale Air Force Base, Louisiana. The command serves as Air Forc ...

and his replacement by an American aviation legend, Maj. Gen

Jimmy Doolittle

James Harold Doolittle (December 14, 1896 – September 27, 1993) was an American military general and aviation pioneer who received the Medal of Honor for his daring raid on Japan during World War II. He also made early coast-to-coast flights ...

signaled a change in how the American bombing effort went forward over Europe. Doolittle's major influence on the European air war occurred early in the year when he changed the policy requiring escorting fighters to remain with the bombers at all times. With his permission, initially performed with

P-38

The Lockheed P-38 Lightning is an American single-seat, twin piston-engined fighter aircraft that was used during World War II. Developed for the United States Army Air Corps by the Lockheed Corporation, the P-38 incorporated a distinctive twi ...

s and

P-47

The Republic P-47 Thunderbolt is a World War II-era fighter aircraft produced by the American company Republic Aviation from 1941 through 1945. It was a successful high-altitude fighter and it also served as the foremost American fighter-bomber ...

s with both previous types being steadily replaced with the long-ranged

P-51

The North American Aviation P-51 Mustang is an American long-range, single-seat fighter and fighter-bomber used during World War II and the Korean War, among other conflicts. The Mustang was designed in April 1940 by a team headed by James ...

s as the spring of 1944 wore on, American fighter pilots on bomber defense missions would primarily be flying far ahead of the bombers'

combat box

The combat box was a tactical formation used by heavy (strategic) bombers of the U.S. Army Air Forces during World War II. The combat box was also referred to as a "staggered formation". Its defensive purpose was in massing the firepower of the b ...

formations in

air supremacy

Aerial supremacy (also air superiority) is the degree to which a side in a conflict holds control of air power over opposing forces. There are levels of control of the air in aerial warfare. Control of the air is the aerial equivalent of comm ...

mode, literally "clearing the skies" of any

Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German '' Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the '' Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabt ...

fighter opposition heading towards the target. This strategy fatally disabled the twin-engined ''Zerstörergeschwader''

heavy fighter

A heavy fighter is a historic category of fighter aircraft produced in the 1930s and 1940s, designed to carry heavier weapons, and/or operate at longer ranges than light fighter aircraft. To achieve performance, most heavy fighters were twin-eng ...

wings and their replacement, single-engined ''Sturmgruppen'' of

heavily armed Fw 190As, clearing each force of

bomber destroyer

Bomber destroyers were World War II interceptor aircraft intended to destroy enemy bomber aircraft. Bomber destroyers were typically larger and heavier than general interceptors, designed to mount more powerful armament, and often having twin en ...

s in their turn from Germany's skies throughout most of 1944. As part of this game-changing strategy, especially after the bombers had hit their targets, the USAAF's fighters were then free to strafe German airfields and transport while returning to base, contributing significantly to the achievement of air superiority by Allied air forces over Europe.

On 27 March 1944, the Combined Chiefs of Staff issued orders granting control of all the Allied air forces in Europe, including strategic bombers, to General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the

Supreme Allied Commander, who delegated command to his deputy in

SHAEF

Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF; ) was the headquarters of the Commander of Allied forces in north west Europe, from late 1943 until the end of World War II. U.S. General Dwight D. Eisenhower was the commander in SHAEF ...

Air Chief Marshal

Arthur Tedder. There was resistance to this order from some senior figures, including Winston Churchill, Harris, and

Carl Spaatz, but after some debate, control passed to SHAEF on 1 April 1944. When the Combined Bomber Offensive officially ended on 1 April, Allied airmen were well on the way to achieving air superiority over all of Europe. While they continued some strategic bombing, the USAAF along with the RAF turned their attention to the tactical air battle in support of the Normandy Invasion. It was not until the middle of September that the strategic bombing campaign of Germany again became the priority for the USAAF.

The twin campaigns—the USAAF by day, the RAF by night—built up into massive bombing of German industrial areas, notably the

Ruhr, followed by attacks directly on cities such as

Hamburg

(male), (female) en, Hamburger(s),

Hamburgian(s)

, timezone1 = Central (CET)

, utc_offset1 = +1

, timezone1_DST = Central (CEST)

, utc_offset1_DST = +2

, postal ...

,

Kassel

Kassel (; in Germany, spelled Cassel until 1926) is a city on the Fulda River in northern Hesse, Germany. It is the administrative seat of the Regierungsbezirk Kassel and the district of the same name and had 201,048 inhabitants in December 2020 ...

,

Pforzheim

Pforzheim () is a city of over 125,000 inhabitants in the federal state of Baden-Württemberg, in the southwest of Germany.

It is known for its jewelry and watch-making industry, and as such has gained the nickname "Goldstadt" ("Golden City") ...

,

Mainz

Mainz () is the capital and largest city of Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany.

Mainz is on the left bank of the Rhine, opposite to the place that the Main (river), Main joins the Rhine. Downstream of the confluence, the Rhine flows to the north-we ...

and the often-criticized

bombing of Dresden

The bombing of Dresden was a joint British and American aerial bombing attack on the city of Dresden, the capital of the German state of Saxony, during World War II. In four raids between 13 and 15 February 1945, 772 heavy bombers of the Roya ...

.

Operation Overlord

The second European front that the Soviets had pressed for was finally opened on 6 June 1944, when the Allies launched an

invasion of Normandy

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the Allied operation that launched the successful invasion of German-occupied Western Europe during World War II. The operation was launched on 6 June 1944 (D-Day) with the Norm ...

.

Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower had delayed the attack because of bad weather, but finally, the largest amphibious assault in history began.

After prolonged bombing runs on the French coast by the Army Air Forces, 225

US Army Rangers

United States Army Rangers, according to the US Army's definition, are personnel, past or present, in any unit that has the official designation "Ranger". The term is commonly used to include graduates of the US Army Ranger School, even if t ...

scaled the cliffs at

Pointe du Hoc under intense enemy fire and destroyed the German gun emplacements that could have threatened the amphibious landings. Also before the main amphibious assault, the American

82nd and

101st

The 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault) ("Screaming Eagles") is a light infantry division (military), division of the United States Army that specializes in air assault military operation, operations. It can plan, coordinate, and execute mul ...

Airborne divisions dropped behind the beaches into

Nazi-occupied France

The Military Administration in France (german: Militärverwaltung in Frankreich; french: Occupation de la France par l'Allemagne) was an interim occupation authority established by Nazi Germany during World War II to administer the occupied zo ...

, to protect the coming landings. Many of the

paratrooper

A paratrooper is a military parachutist—someone trained to parachute into a military operation, and usually functioning as part of an airborne force. Military parachutists (troops) and parachutes were first used on a large scale during World ...