As an

archaeological culture

An archaeological culture is a recurring assemblage of types of artifacts, buildings and monuments from a specific period and region that may constitute the material culture remains of a particular past human society. The connection between thes ...

, the

Mapuche people

The Mapuche ( (Mapuche & Spanish: )) are a group of indigenous inhabitants of south-central Chile and southwestern Argentina, including parts of Patagonia. The collective term refers to a wide-ranging ethnicity composed of various groups who sha ...

of southern Chile and Argentina have a long history which dates back to 600–500 BC. The Mapuche society underwent great transformations after

Spanish contact in the mid–16th century. These changes included the adoption of Old World crops and animals and the onset of a rich Spanish–Mapuche trade in

La Frontera and

Valdivia

Valdivia (; Mapuche: Ainil) is a city and commune in southern Chile, administered by the Municipality of Valdivia. The city is named after its founder Pedro de Valdivia and is located at the confluence of the Calle-Calle, Valdivia, and Cau-Cau R ...

. Despite these contacts Mapuche were never completely subjugated by the Spanish Empire. Between the 18th and 19th century Mapuche culture and people spread eastwards into the

Pampas

The Pampas (from the qu, pampa, meaning "plain") are fertile South American low grasslands that cover more than and include the Argentine provinces of Buenos Aires, La Pampa, Santa Fe, Entre Ríos, and Córdoba; all of Uruguay; and Brazil ...

and the

Patagonian plains. This vast new territory allowed Mapuche groups to control a substantial part of the salt and cattle trade in the Southern Cone.

Between 1861 and 1883 the Republic of Chile

conducted a series of campaigns that ended Mapuche independence causing the death of thousands of Mapuche through combat, pillaging, starvation and

smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

epidemics. Argentina conducted

similar campaigns on the eastern side of the Andes in the 1870s. In large parts of the Mapuche lands the traditional economy collapsed forcing thousands to seek themselves to the large cities and live in impoverished conditions as

housemaid

A maid, or housemaid or maidservant, is a female domestic worker. In the Victorian era domestic service was the second largest category of employment in England and Wales, after agricultural work. In developed Western nations, full-time maid ...

s,

hawkers or

labourer

A laborer (or labourer) is a person who works in manual labor types in the construction industry workforce. Laborers are in a working class of wage-earners in which their only possession of significant material value is their labor. Industries e ...

s.

From the late 20th century onwards Mapuche people have been increasingly active in conflicts over

land rights

Land law is the form of law that deals with the rights to use, alienate, or exclude others from land. In many jurisdictions, these kinds of property are referred to as real estate or real property, as distinct from personal property. Land use ...

and

indigenous rights

Indigenous rights are those rights that exist in recognition of the specific condition of the Indigenous peoples. This includes not only the most basic human rights of physical survival and integrity, but also the rights over their land (includ ...

.

Pre-Columbian period

Origins

Archaeological finds have shown the existence of a Mapuche culture in Chile as early as 600 to 500 BC.

[ Bengoa 2000, pp. 16–19.] Genetically Mapuches differ from the adjacent indigenous peoples of Patagonia.

This is interpreted as suggesting either a "different origin or long lasting separation of Mapuche and Patagonian populations".

[ A 1996 study comparing genetics of indigenous groups in Argentina found no significant link between Mapuches and other groups. A 2019 study on the ]human leukocyte antigen

The human leukocyte antigen (HLA) system or complex is a complex of genes on chromosome 6 in humans which encode cell-surface proteins responsible for the regulation of the immune system. The HLA system is also known as the human version of th ...

genetics of Mapuche from Cañete found affinities with a variety of North and South American indigenous groups. Notably the study found also affinities also with Aleuts

The Aleuts ( ; russian: Алеуты, Aleuty) are the indigenous people of the Aleutian Islands, which are located between the North Pacific Ocean and the Bering Sea. Both the Aleut people and the islands are politically divided between the U ...

, Eskimo

Eskimo () is an exonym used to refer to two closely related Indigenous peoples: the Inuit (including the Alaska Native Iñupiat, the Greenlandic Inuit, and the Canadian Inuit) and the Yupik peoples, Yupik (or Siberian Yupik, Yuit) of eastern Si ...

s, Pacific Islander

Pacific Islanders, Pasifika, Pasefika, or rarely Pacificers are the peoples of the list of islands in the Pacific Ocean, Pacific Islands. As an ethnic group, ethnic/race (human categorization), racial term, it is used to describe the original p ...

s, Ainu from Japan, Negidals

Negidals (; Negidal language, Negidal: ''элькан бэйэнин'', ''elkan bayenin'', "local people") are a people in the Khabarovsk Krai in Russia, who live along the Amgun River and Amur River.

The ethnonym "Negidal" is a Russification ...

from Eastern Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive region, geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a ...

and Rapa Nui

Easter Island ( rap, Rapa Nui; es, Isla de Pascua) is an island and special territory of Chile in the southeastern Pacific Ocean, at the southeasternmost point of the Polynesian Triangle in Oceania. The island is most famous for its nearly ...

from Easter Island

Easter Island ( rap, Rapa Nui; es, Isla de Pascua) is an island and special territory of Chile in the southeastern Pacific Ocean, at the southeasternmost point of the Polynesian Triangle in Oceania. The island is most famous for its nearl ...

.

There is no consensus on the linguistic affiliation of the Mapuche language

Mapuche (, Mapuche & Spanish: , or Mapudungun; from ' 'land' and ' 'speak, speech') is an Araucanian language related to Huilliche spoken in south-central Chile and west-central Argentina by the Mapuche people (from ''mapu'' 'land' and ''che ...

, . In the early 1970s, significant linguistic affinities between Mapuche and Mayan languages

The Mayan languagesIn linguistics, it is conventional to use ''Mayan'' when referring to the languages, or an aspect of a language. In other academic fields, ''Maya'' is the preferred usage, serving as both a singular and plural noun, and as ...

were suggested.[ Linguist Mary Ritchie Key claimed in 1978 that Araucanian languages, including Mapuche, were genetically linked to the ]Pano-Tacanan languages

Pano-Tacanan (also Pano-Takana, Pano-Takánan, Pano-Tacana, Páno-Takána) is a proposed family of languages spoken in Peru, western Brazil, Bolivia and northern Paraguay. There are two close-knit branches, Panoan and Tacanan (Adelaar & Muysken 2 ...

, to the Chonan languages

The Chonan languages are a family of indigenous American languages which were spoken in Tierra del Fuego and Patagonia. Two Chon languages are well attested: Selk'nam (or Ona), spoken by the people of the same name who occupied territory in the ...

and the Kawéskar languages.Arawakan languages

Arawakan (''Arahuacan, Maipuran Arawakan, "mainstream" Arawakan, Arawakan proper''), also known as Maipurean (also ''Maipuran, Maipureano, Maipúre''), is a language family that developed among ancient indigenous peoples in South America. Branc ...

.

In 1954 Grete Mostny postulated the idea of a link between Mapuches and the archaeological culture of El Molle in the Transverse Valleys

The Transverse Valleys (Spanish: ''Valles transversales'') are a group of transverse valleys in the semi-arid northern Chile. They run from east to west (traversing Chile), being among the most prominent geographical features in the regions they cr ...

of Norte Chico.[ This idea was followed up by Patricio Bustamante in 2007. Mapuche communities in the southern ]Diaguita

The Diaguita people are a group of South American indigenous people native to the Chilean Norte Chico and the Argentine Northwest. Western or Chilean Diaguitas lived mainly in the Transverse Valleys which incised in a semi-arid environment. Ea ...

lands –that is Petorca

Petorca is a Chilean town and commune located in the Petorca Province, Valparaíso Region. The commune spans an area of . Since 2010 Petorca has been affected by a long-term drought aggravated by poor water administration that have allowed limi ...

, La Ligua

La Ligua () is a Chilean city and commune, capital of the Petorca Province in Valparaíso Region.

The city is known for its textile manufacturing and traditional Chilean pastry production.

Demographics

According to data from the 2002 Census o ...

, Combarbalá

Combarbalá is the capital city of the commune of Combarbala. It is located in the Limarí Province, Region of Coquimbo, at an elevation of 900 m (2,952 ft). It is known for the tourist astronomic observatory Cruz del Sur; the petro ...

and Choapa – may be rooted in Pre-Hispanic times at least several centuries before the Spanish arrival.[Téllez 2008, p. 43.] Mapuche toponymy is also found throughout the area.[ While there was an immigration of Mapuches to the southern Diaguita lands in colonial times Mapuche culture there is judged to be older than this.][

Based on mDNA analysis of various indigenous groups of South America it is thought that Mapuche are at least in part descendant of peoples from the Amazon Basin that migrated to Chile through two routes; one through the Central Andean highlands and another through the eastern Bolivian lowlands and the ]Argentine Northwest

The Argentine Northwest (''Noroeste Argentino'') is a geographic and historical region of Argentina composed of the provinces of Catamarca, Jujuy, La Rioja, Salta, Santiago del Estero and Tucumán.

Geography

The Argentine Northwest comprises v ...

.[

A hypothesis put forward by ]Ricardo E. Latcham

Ricardo Eduardo Latcham Cartwright (Thornbury, England, 5 March 1869 - Santiago, Chile, 16 October 1943) was an English-Chilean archaeologist, ethnologist, folklore scholar and teacher.

Born and raised near Bristol, England, as Richard Edward La ...

, and later expanded by Francisco Antonio Encina

Francisco Antonio Encina Armanet (September 10, 1874, San Javier – August 23, 1965, Santiago) was a Chilean politician, agricultural businessman, political essayist, historian and prominent white nationalist. He authored the ''History of Chile ...

, theorizes that the Mapuche migrated to present-day Chile from the Pampas

The Pampas (from the qu, pampa, meaning "plain") are fertile South American low grasslands that cover more than and include the Argentine provinces of Buenos Aires, La Pampa, Santa Fe, Entre Ríos, and Córdoba; all of Uruguay; and Brazil ...

east of the Andes.[ The hypothesis further claims that previous to the Mapuche, there was a " Chincha-Diaguita" culture, which was geographically cut in half by the Mapuche penetrating from mountain passes around the head of the ]Cautín River

The Cautín (Rio Cautín) is a river in Chile. It rises on the western slopes of the Cordillera de Las Raíces and flows in La Araucanía Region. The river's main tributary is the Quepe River. The city of Temuco is located on the Cautín River. ...

.[ it is rejected by modern scholars due to the lack of conclusive evidence, and the possibility of alternative hypotheses.][

]Tomás Guevara

Tomás Guevara Silva (1865–1935) was a Chilean historian, teacher, War of the Pacific veteran and a prominent scholar of the Mapuche people. He was born in Curicó

Curicó (), meaning "Black Waters" in Mapudungun (originally meaning "Land ...

has postulated another unproven hypothesis

A hypothesis (plural hypotheses) is a proposed explanation for a phenomenon. For a hypothesis to be a scientific hypothesis, the scientific method requires that one can test it. Scientists generally base scientific hypotheses on previous obse ...

claiming that early Mapuches dwelled at the coast due to abundant marine resources and did only later moved inland following large rivers.[Bengoa 2003, pp. 33–34.] Guevara adds that Mapuches would be descendants of northern Changos

The Changos, also known as Camanchacos or Camanchangos, are an indigenous people or group of peoples who inhabited a long stretch of the Pacific coast from southern Peru to north-central Chile, including the coast of the Atacama desert.

Although ...

, a poorly known coastal people, who moved southwards.[Bengoa 2003, p. 52.] This hypothesis is supported by tenuous linguistic evidence linking a language of 19th century Changos (called Chilueno or Arauco) with Mapudungun.Antisuyu

Antisuyu ( , ) was the eastern part of the Inca Empire which bordered on the modern-day Upper Amazon region which the Anti inhabited. Along with Chinchaysuyu, it was part of the '' Hanan Suyukuna'' or "upper quarters" of the empire, constituti ...

and Contisuyu

Kuntisuyu or Kunti Suyu (Quechua language, Quechua ''kunti'' west, ''suyu'' region, part of a territory, each of the four regions which formed the Inca Empire, "western region") was the Ordinal directions, southwestern provincial region of the Inca ...

.

Tiwanaku and Puquina influence

It has been conjectured that the collapse of the Tiwanaku empire about 1000 CE caused a southward migratory wave leading to a series of changes in Mapuche

The Mapuche ( (Mapuche & Spanish: )) are a group of indigenous inhabitants of south-central Chile and southwestern Argentina, including parts of Patagonia. The collective term refers to a wide-ranging ethnicity composed of various groups who sha ...

society in Chile.Mapuche language

Mapuche (, Mapuche & Spanish: , or Mapudungun; from ' 'land' and ' 'speak, speech') is an Araucanian language related to Huilliche spoken in south-central Chile and west-central Argentina by the Mapuche people (from ''mapu'' 'land' and ''che ...

obtained many loanwords from Puquina language

Puquina (or Pukina) is a small, putative language family, often portrayed as a language isolate, which consists of the extinct Puquina language and Kallawaya, although it is assumed that the latter is just a remnant of the former mixed with Que ...

including (sun), (warlock), (moon), (salt) and (mother).[ ]Tom Dillehay

Tom Dillehay is an American anthropologist who is the Rebecca Webb Wilson University Distinguished Professor of Anthropology, Religion, and Culture and Professor of Anthropology at Vanderbilt University. In addition to Vanderbilt, Dillehay has tau ...

and co-workers suggest that the decline of Tiwanaku would have led to the spread of agricultural techniques into Mapuche lands in south-central Chile. These techniques include the raised field

In agriculture, a raised field is a large, cultivated elevation, typically bounded by water-filled ditches, that is used to allow cultivators to control environmental factors such as moisture levels, frost damage, and flooding. Examples of raised f ...

s of Budi Lake and the canalized fields found in Lumaco Valley.[

A cultural linkage of this sort may help explain parallels in mythological cosmologies among Mapuches and peoples of the Central Andes.][

]

Possible Polynesian contact

In 2007, evidence appeared to have been found that suggested pre-Columbian contact between

In 2007, evidence appeared to have been found that suggested pre-Columbian contact between Polynesians

Polynesians form an ethnolinguistic group of closely related people who are native to Polynesia (islands in the Polynesian Triangle), an expansive region of Oceania in the Pacific Ocean. They trace their early prehistoric origins to Island Sou ...

from the western Pacific and the Mapuche people. Chicken bones found at the El Arenal site in the Arauco Peninsula The Arauco Peninsula (Spanish: península de Arauco), is a peninsula in Southern Chile located in the homonymous Arauco Province. It projects northwest into the Pacific Ocean. The peninsula is located west of Cordillera de Nahuelbuta. Geologicall ...

, an area inhabited by Mapuche, support a pre-Columbian introduction of chicken

The chicken (''Gallus gallus domesticus'') is a domesticated junglefowl species, with attributes of wild species such as the grey and the Ceylon junglefowl that are originally from Southeastern Asia. Rooster or cock is a term for an adult m ...

to South America.[ The bones found in Chile were carbon-dated to between 1304 and 1424, before the arrival of the Spanish. Chicken DNA sequences taken were matched to those of chickens in present-day ]American Samoa

American Samoa ( sm, Amerika Sāmoa, ; also ' or ') is an unincorporated territory of the United States located in the South Pacific Ocean, southeast of the island country of Samoa. Its location is centered on . It is east of the International ...

and Tonga

Tonga (, ; ), officially the Kingdom of Tonga ( to, Puleʻanga Fakatuʻi ʻo Tonga), is a Polynesian country and archipelago. The country has 171 islands – of which 45 are inhabited. Its total surface area is about , scattered over in ...

; they did not match the DNA of European chickens.Mocha Island

Mocha Island ( es, link=no, Isla Mocha ) is a small Chilean island located west of the coast of Arauco Province in the Pacific Ocean. The island is approximately in area, with a small chain of mountains running roughly in north-south direction. ...

, an island just off the coast of Chile in the Pacific Ocean, today inhabited by Mapuche. Professor Lisa Matisoo-Smith of the University of Otago

, image_name = University of Otago Registry Building2.jpg

, image_size =

, caption = University clock tower

, motto = la, Sapere aude

, mottoeng = Dare to be wise

, established = 1869; 152 years ago

, type = Public research collegiate u ...

and José Miguel Ramírez Aliaga of the University of Valparaíso hope to win agreement soon with the locals of Mocha Island to begin an excavation to search for Polynesian remains on the island. Rocker jaws have also been found at an excavation led Ramírez in pre-Hispanic tombs and shell middens

A midden (also kitchen midden or shell heap) is an old dump for domestic waste which may consist of animal bone, human excrement, botanical material, mollusc shells, potsherds, lithics (especially debitage), and other artifacts and ecofac ...

( es, conchal) of the coastal locality of Tunquén, Central Chile.Rapa Nui

Easter Island ( rap, Rapa Nui; es, Isla de Pascua) is an island and special territory of Chile in the southeastern Pacific Ocean, at the southeasternmost point of the Polynesian Triangle in Oceania. The island is most famous for its nearly ...

cognate

In historical linguistics, cognates or lexical cognates are sets of words in different languages that have been inherited in direct descent from an etymology, etymological ancestor in a proto-language, common parent language. Because language c ...

s have been described".[

The Mapuche clava hand club have striking similarities with the Maori ]wahaika

A Wahaika is a type of traditional Māori hand weapon. Wahaika are short club-like weapons usually made of wood or whalebone and are used for thrusting and striking in close-quarter, hand-to-hand fighting. Whalebone wahaika are called ''wahaika ...

.[

]

Mapuche expansion into Chiloé Archipelago

A theory postulated by chronicler

A theory postulated by chronicler José Pérez García

José is a predominantly Spanish and Portuguese form of the given name Joseph. While spelled alike, this name is pronounced differently in each language: Spanish ; Portuguese (or ).

In French, the name ''José'', pronounced , is an old vernacul ...

holds the Cunco settled in Chiloé Island

Chiloé Island ( es, Isla de Chiloé, , ) also known as Greater Island of Chiloé (''Isla Grande de Chiloé''), is the largest island of the Chiloé Archipelago off the west coast of Chile, in the Pacific Ocean. The island is located in southern ...

in Pre-Hispanic

In the history of the Americas, the pre-Columbian era spans from the original settlement of North and South America in the Upper Paleolithic period through European colonization, which began with Christopher Columbus's voyage of 1492. Usually, th ...

times as consequence of a push from more northern Huilliche

The Huilliche , Huiliche or Huilliche-Mapuche are the southern partiality of the Mapuche macroethnic group of Chile. Located in the Zona Sur, they inhabit both Futahuillimapu ("great land of the south") and, as the Cunco subgroup, the north hal ...

who in turn were being displaced by Mapuche

The Mapuche ( (Mapuche & Spanish: )) are a group of indigenous inhabitants of south-central Chile and southwestern Argentina, including parts of Patagonia. The collective term refers to a wide-ranging ethnicity composed of various groups who sha ...

.[Alcamán 1997, p. 32.][Alcamán 1997, p. 33.]

Evidence for a Chono past of the southernmost Mapuche lands in Chiloé and the nearby mainland are various placenames with Chono etymologies despite the main indigenous language of the archipelago at the arrival of the Spanish being veliche (Mapuche).Ricardo E. Latcham

Ricardo Eduardo Latcham Cartwright (Thornbury, England, 5 March 1869 - Santiago, Chile, 16 October 1943) was an English-Chilean archaeologist, ethnologist, folklore scholar and teacher.

Born and raised near Bristol, England, as Richard Edward La ...

who consider the Chono along other sea-faring nomads may be remnants from more widespread indigenous groups that were pushed south by "successive invasions" from more northern tribes.[Trivero Rivera 2005, p. 41.]

The Payos, an indigenous group in southern Chiloé encountered by the Spanish, may have been Chonos en route to acculturate into the Mapuche.

Inca expansion and influence

Troops of the Inca Empire

The Inca Empire (also known as the Incan Empire and the Inka Empire), called ''Tawantinsuyu'' by its subjects, (Quechua for the "Realm of the Four Parts", "four parts together" ) was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The admin ...

are reported to have reached Maule River

The Maule river or Río Maule ( Mapudungun: ''rainy'') is one of the most important rivers of Chile. It is inextricably linked to the country's pre-Hispanic (Inca) times, the country's conquest, colonial period, wars of Independence, modern hist ...

and had a battle with Mapuches from Maule River and Itata River

The Itata River flows in the Ñuble Region, southern Chile.

Until the Conquest of Chile, the Itata was the natural limit between the Mapuche, located to the south, and Picunche, to the north.

See also

*Itata

*List of rivers in Chile

This list o ...

there.[Bengoa 2003, pp. 37–38.] The southern border of the Inca Empire is believed by most modern scholars to be situated between Santiago

Santiago (, ; ), also known as Santiago de Chile, is the capital and largest city of Chile as well as one of the largest cities in the Americas. It is the center of Chile's most densely populated region, the Santiago Metropolitan Region, whose ...

and the Maipo River or somewhere between Santiago and the Maule River.Miguel de Olavarría

-->

Miguel is a given name and surname, the Portuguese and Spanish form of the Hebrew name Michael (given name), Michael. It may refer to:

Places

*Pedro Miguel, a parish in the municipality of Horta and the island of Faial in the Azores Islands ...

and Diego de Rosales

Diego de Rosales (Madrid, 1601 - Santiago, 1677) was a Spanish chronicler and author of ''Historia General del Reino de Chile''.

He studied in his hometown, where he also joined the Society of Jesus. He came to Chile in the year 1629, without ha ...

claimed the Inca frontier laid much further south at the Bío Bío River.[ While historian ]José Bengoa

José Bengoa Cabello (19 January 1945) is a Chilean historian and anthropologist. He is known in Chile for his study of Mapuche history and society. After the 1973 Chilean coup d'état, José Bengoa was dismissed from his work at the University of ...

concludes that Inca troops apparently never crossed Bío Bío River,[Bengoa 2003, p. 39.] chronicler Diego de Rosales gives an account of the Incas crossing the river going south all the way to La Imperial and returning north through Tucapel

Tucapel is a town and commune in the Bío Bío Province, Bío Bío Region, Chile. It was once a region of Araucanía named for the Tucapel River. The name of the region derived from the rehue and aillarehue of the Moluche people of the area b ...

along the coast.Aconcagua River

The Aconcagua River is a river in Chile that rises from the conflux of two minor tributary rivers at above sea level in the Andes, Juncal River from the east (which rise in the Nevado Juncal) and Blanco River from the south east. The Aconcag ...

, Mapocho River

The River Mapocho ( es, Río Mapocho) ( Mapudungun: ''Mapu chuco'', "water that penetrates the land") is a river in Chile. It flows from its source in the Andes mountains onto the west and divides Chile's capital Santiago in two.

Course

The Mapo ...

and the Maipo River.[ ]Quillota

Quillota is a city located in the Aconcagua River valley in central Chile's Valparaíso Region. It is the capital and largest city of Quillota Province, where many inhabitants live in the outlying farming areas of San Isidro, La Palma, Pocochay ...

in Aconcagua Valley was likely their foremost settlement.[ As result of Inca rule there was some Mapudungun– Imperial Quechua bilingualism among Mapuches of Aconcagua Valley.][ Salas argue Mapuche, Quechua and Spanish coexisted with significant bilingualism in Central Chile (between Mapocho and Bío Bío) rivers during the 17th century.

As it appear to be the case in the other borders of the Inca Empire, the southern border was composed of several zones: first, an inner, fully incorporated zone with ]mitimaes

Mitimaes is a folk music group from Peru. The group dates from 1983, having its first public performance in March in the Festival of the Zampoñas of Gold, organized by Department of Education in Arequipa winning first place in Peruvian folk music ...

protected by a line of pukara

Pukara (Aymara and Quechuan "fortress", Hispanicized spellings ''pucara, pucará'') is a defensive hilltop site or fortification built by the prehispanic and historic inhabitants of the central Andean area (from Ecuador to central Chile and no ...

s (fortresses) and then an outer zone with Inca pukaras scattered among allied tribes.[ This outer zone would according to historian ]José Bengoa

José Bengoa Cabello (19 January 1945) is a Chilean historian and anthropologist. He is known in Chile for his study of Mapuche history and society. After the 1973 Chilean coup d'état, José Bengoa was dismissed from his work at the University of ...

have been located between Maipo and Maule Rivers.[

Incan '']yanakuna

Yanakuna were originally individuals in the Inca Empire who left the ayllu system and worked full-time at a variety of tasks for the Inca, the ''quya'' (Inca queen), or the religious establishment. A few members of this serving class enjoyed high s ...

'' are believed by archaeologists Tom Dillehay

Tom Dillehay is an American anthropologist who is the Rebecca Webb Wilson University Distinguished Professor of Anthropology, Religion, and Culture and Professor of Anthropology at Vanderbilt University. In addition to Vanderbilt, Dillehay has tau ...

and Américo Gordon to have extracted gold south of the Incan frontier in free Mapuche territory. Following this thought the main motif for Incan expansion into Mapuche territory would have been to access gold mines. Same archaeologists do also claim all early Mapuche pottery at Valdivia

Valdivia (; Mapuche: Ainil) is a city and commune in southern Chile, administered by the Municipality of Valdivia. The city is named after its founder Pedro de Valdivia and is located at the confluence of the Calle-Calle, Valdivia, and Cau-Cau R ...

is of Inca design.[ Inca influence can also be evidenced far south as ]Osorno Province

Osorno Province ( es, Provincia de Osorno) is one of the four provinces in the southern Chilean region of Los Lagos (X). The province has an area of and a population of 221,496 distributed across seven communes ( Spanish: ''comunas''). The provi ...

(latitude 40–41° S) in the form of Quechua

Quechua may refer to:

*Quechua people, several indigenous ethnic groups in South America, especially in Peru

*Quechuan languages, a Native South American language family spoken primarily in the Andes, derived from a common ancestral language

**So ...

and Quechua–Aymara

Aymara may refer to:

Languages and people

* Aymaran languages, the second most widespread Andean language

** Aymara language, the main language within that family

** Central Aymara, the other surviving branch of the Aymara(n) family, which today ...

toponym

Toponymy, toponymics, or toponomastics is the study of '' toponyms'' (proper names of places, also known as place names and geographic names), including their origins, meanings, usage and types. Toponym is the general term for a proper name of ...

s. Alternatively these toponyms originated in colonial times

The ''Colonial Times'' was a newspaper in what is now the Australian state of Tasmania. It was established as the ''Colonial Times, and Tasmanian Advertiser'' in 1825 in Hobart, Van Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land was the colon ...

from the population of the Valdivian Fort System

The Fort System of Valdivia ( es, Sistema de fuertes de Valdivia) is a series of Spanish colonial fortifications at Corral Bay, Valdivia and Cruces River established to protect the city of Valdivia, in southern Chile. During the period of Spani ...

that served as a penal colony

A penal colony or exile colony is a settlement used to exile prisoners and separate them from the general population by placing them in a remote location, often an island or distant colonial territory. Although the term can be used to refer to ...

linked to the Peruvian port of El Callao

Callao () is a Peruvian seaside city and region on the Pacific Ocean in the Lima metropolitan area. Callao is Peru's chief seaport and home to its main airport, Jorge Chávez International Airport. Callao municipality consists of the whole Call ...

.

Gold and silver bracelets and "sort of crowns" were used by Mapuches in the Concepción area at the time of the Spanish arrival as noted by Jerónimo de Vivar Jerónimo de Vivar was a Spanish historian of the early conquest and settlement of the Kingdom of Chile, and author of ''Crónica y relación copiosa y verdadera de los reinos de Chile''.

Little is known about his life except that according to his ...

. This is interpreted either as Incan gifts, war spoils from defeated Incas, or adoption of Incan metallurgy.[

Through their contact with Incan invaders Mapuches would have for the first time met people with state-level organization. Their contact with the Inca gave them a collective awareness distinguishing between them and the invaders and uniting them into loose geopolitical units despite their lack of state organization.][Bengoa 2003, p. 40.]

Mapuche society at the arrival of the Spanish

Demography and settlement types

At the time of the arrival of the first Spaniards to Chile the largest indigenous population concentration was in the area spanning from Itata River

The Itata River flows in the Ñuble Region, southern Chile.

Until the Conquest of Chile, the Itata was the natural limit between the Mapuche, located to the south, and Picunche, to the north.

See also

*Itata

*List of rivers in Chile

This list o ...

to Chiloé Archipelago

The Chiloé Archipelago ( es, Archipiélago de Chiloé, , ) is a group of islands lying off the coast of Chile, in the Los Lagos Region. It is separated from mainland Chile by the Chacao Channel in the north, the Sea of Chiloé in the east and t ...

—that is the Mapuche heartland.[Otero 2006, p. 36.] The Mapuche population between Itata River and Reloncaví Sound

Reloncaví Sound or ''Seno de Reloncaví'' is a body of water immediately south of Puerto Montt, a port city in the Los Lagos Region of Chile. It is the place where the Chilean Central Valley meets the Pacific Ocean.

The Calbuco Archipelago com ...

has been estimated at 705,000–900,000 in the mid-16th century by historian José Bengoa

José Bengoa Cabello (19 January 1945) is a Chilean historian and anthropologist. He is known in Chile for his study of Mapuche history and society. After the 1973 Chilean coup d'état, José Bengoa was dismissed from his work at the University of ...

.[Bengoa 2003, p. 157.]

Mapuches lived in scattered hamlet

''The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark'', often shortened to ''Hamlet'' (), is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play, with 29,551 words. Set in Denmark, the play depicts ...

s, mainly along the great rivers of Southern Chile

Southern Chile is an informal geographic term for any place south of the capital city, Santiago, or south of Biobío River, the mouth of which is Concepción, about {{convert, 200, mi, km, sigfig=1, order=flip south of Santiago. Generally cities ...

.[Bengoa 2003, p. 29.][ All major population centres lay at the confluences of rivers.][Bengoa 2003, p. 56–57.] Mapuches preferred to build their houses on hilly terrain or isolated hills rather than on plains and terrace

Terrace may refer to:

Landforms and construction

* Fluvial terrace, a natural, flat surface that borders and lies above the floodplain of a stream or river

* Terrace, a street suffix

* Terrace, the portion of a lot between the public sidewalk a ...

s.[

]

Mythology and religion

The ''machi'' (shaman), a role usually played by older women, is an extremely important part of the Mapuche culture. The performs ceremonies for the warding off of evil, for rain, for the cure of diseases, and has an extensive knowledge of

The ''machi'' (shaman), a role usually played by older women, is an extremely important part of the Mapuche culture. The performs ceremonies for the warding off of evil, for rain, for the cure of diseases, and has an extensive knowledge of Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

an medicinal herbs, gained during an arduous apprenticeship. Chileans of all origins and classes make use of the many traditional herbs known to the Mapuche. The main healing ceremony performed by the machi is called the .

s were used in funerals and they are present in narratives about death in Mapuche religion

The mythology and religion of the indigenous Mapuche people of south-central Chile and southwestern Argentina is an extensive and ancient belief system. A series of unique legends and myths are common to the various groups that make up the Mapuc ...

.[Bengoa 2003, p. 86–87.]

Social organization

The politics, economy and religion of the pre- and early-contact Mapuches were based on the lineages of local communities called . This kind of organization was replicated at the larger ''rehue

A rehue (Mapudungun spelling rewe) or kemukemu is a type of pillar-like sacred altar used by the Mapuche of Chile in many of their ceremonies.

Altar/Axis mundi

The ''rehue'' is a carved tree trunk set in the ground, surrounded by a hedge o ...

'' level that encompassed several .[Dillehay 2007, p. 336.] The politics of each lineage were not equally aggressive or submissive, but different from case to case.[ Lineages were ]patrilineal

Patrilineality, also known as the male line, the spear side or agnatic kinship, is a common kinship system in which an individual's family membership derives from and is recorded through their father's lineage. It generally involves the inheritanc ...

and patrilocal

In social anthropology, patrilocal residence or patrilocality, also known as virilocal residence or virilocality, are terms referring to the social system in which a married couple resides with or near the husband's parents. The concept of locat ...

.[ ]Polygamy

Crimes

Polygamy (from Late Greek (') "state of marriage to many spouses") is the practice of marrying multiple spouses. When a man is married to more than one wife at the same time, sociologists call this polygyny. When a woman is married ...

was common among Mapuches and together with the custom of feminine exogamy

Exogamy is the social norm of marrying outside one's social group. The group defines the scope and extent of exogamy, and the rules and enforcement mechanisms that ensure its continuity. One form of exogamy is dual exogamy, in which two groups c ...

it has been credited by José Bengoa

José Bengoa Cabello (19 January 1945) is a Chilean historian and anthropologist. He is known in Chile for his study of Mapuche history and society. After the 1973 Chilean coup d'état, José Bengoa was dismissed from his work at the University of ...

with welding the Mapuche into one people.[Bengoa 2003, p. 83–85.]

Early Mapuches had two types of leaders, secular and religious. The religious were '' machi'', and the . The secular were the , '' ülmen'' and . Later the secular leaders were known as ''lonko

A lonko or lonco (from Mapudungun ''longko'', literally "head"), is a chief of several Mapuche communities. These were often ulmen, the wealthier men in the lof. In wartime, lonkos of the various local rehue or the larger aillarehue would gather in ...

'', '' toki'', and .[

]

Economy

In South-Central Chile most Mapuche groups practised glade

Glade may refer to:

Computing

* Glade Interface Designer, a GUI designer for GTK+ and GNOME

Geography

*Glade (geography), open area in woodland, synonym for "clearing"

**Glade skiing, skiing amongst trees

;Places in the United States

* Glade, Kan ...

agriculture among the forests.[Otero 2006, pp. 21-22.] Other agriculture types existed; while some Mapuches and Huilliches practised a slash-and-burn

Slash-and-burn agriculture is a farming method that involves the cutting and burning of plants in a forest or woodland to create a field called a swidden. The method begins by cutting down the trees and woody plants in an area. The downed vegeta ...

type of agriculture, some more labour-intensive agriculture is known to have been developed by Mapuches around Budi Lake (raised field

In agriculture, a raised field is a large, cultivated elevation, typically bounded by water-filled ditches, that is used to allow cultivators to control environmental factors such as moisture levels, frost damage, and flooding. Examples of raised f ...

s) and the Lumaco

Lumaco is a town and commune in Malleco Province in the Araucanía Region of Chile. Its name in Mapudungun means "water of '' luma''". Lumaco is located to northeast of Temuco and from Angol. It shares a boundary to the north with the comm ...

and Purén

Purén is a city (2002 pop. 12,868) and commune in Malleco Province of La Araucanía Region, Chile. It is located in the west base of the Nahuelbuta mountain range (650 km. south of Santiago). The economical activity of Purén is based in fo ...

valleys (canalized fields).[ Potato was the ]staple food

A staple food, food staple, or simply a staple, is a food that is eaten often and in such quantities that it constitutes a dominant portion of a standard diet for a given person or group of people, supplying a large fraction of energy needs and ...

of most Mapuches, "specially in the southern and coastal apucheterritories where maize

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 10,000 years ago. Th ...

did not reach maturity".[Bengoa 2003, pp. 199–200.] The bulk of the Mapuche population worked in agriculture.[ Mapuches did also cultivate ]quinoa

Quinoa (''Chenopodium quinoa''; , from Quechua ' or ') is a flowering plant in the amaranth family. It is a herbaceous annual plant grown as a crop primarily for its edible seeds; the seeds are rich in protein, dietary fiber, B vitamins, and ...

, but it is not known if the variety originated in Central Chile

Central Chile (''Zona central'') is one of the five natural regions into which CORFO divided continental Chile in 1950. It is home to a majority of the Chilean population and includes the three largest metropolitan areas—Santiago, Valparaís ...

or in the Central Andes.[

In addition the Mapuche and Huilliche economy was complemented with ]Araucana chicken

The Araucana ( es, Gallina Mapuche, italic=no) is a breed of domestic chicken from Chile. Its name derives from the Araucanía region of Chile where it is believed to have originated. It lays blue-shelled eggs, one of very few breeds that do so. ...

and chilihueque

The chilihueque or hueque was a South American camelid variety or species that existed in central and south-central Chile in Pre-Hispanic and colonial times. There are two main hypotheses on their status among South American camelids: the firs ...

raising[Villalobos ''et al''. 1974, p. 50.][ and collection of '']Araucaria araucana

''Araucaria araucana'' (commonly called the monkey puzzle tree, monkey tail tree, piñonero, pewen or Chilean pine) is an evergreen tree growing to a trunk diameter of 1–1.5 m (3–5 ft) and a height of 30–40 m (100–130 ft). ...

'' and ''Gevuina avellana

''Gevuina avellana'' (Chilean hazelnut ( in Spanish language, Spanish), or ''Gevuina hazelnut''), is an evergreen tree, up to 20 meters (65 feet) tall. It is the only species currently classified in the genus ''Gevuina''. It is native to souther ...

'' seeds.[ The southern coast was particularly rich in ]mollusc

Mollusca is the second-largest phylum of invertebrate animals after the Arthropoda, the members of which are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 85,000 extant species of molluscs are recognized. The number of fossil species is esti ...

s, algaes, crustaceans and fish and Mapuches were known to be good fishers.[Bengoa 2003, pp. 208–209.] Hunting was also a common activity among Mapuches.[ The forests provided ]firewood

Firewood is any wooden material that is gathered and used for fuel. Generally, firewood is not highly processed and is in some sort of recognizable log or branch form, compared to other forms of wood fuel like pellets or chips. Firewood can ...

, fibre and allowed the production of planks.[

Mapuche territory had an effective system of roads before the Spanish arrival as evidenced by the fast advances of the Spanish conquerors.][

]

Technology

Tools are known to have been relatively simple, most of them were made of wood, stone or — more rarely — of copper or bronze.

Tools are known to have been relatively simple, most of them were made of wood, stone or — more rarely — of copper or bronze.[Bengoa 2003, pp. 190–191.] Mapuche used a great variety of tools made of pierced stones.[ Volcanic scoria, a common rock in Southern Chile, was preferentially used to make tools, possibly because it is ease to shape.][Bengoa 2003, pp. 192–193.] Mapuches used both individual digging stick

A digging stick, sometimes called a yam stick, is a wooden implement used primarily by subsistence-based cultures to dig out underground food such as roots and tubers, tilling the soil, or burrowing animals and anthills. It is a term used in ar ...

s and large and heavy trident-like plows that required many men to use in agriculture.[ Another tool used in agriculture were maces used to destroy clods and flatten the soil.][Bengoa 2003, p. 194.]

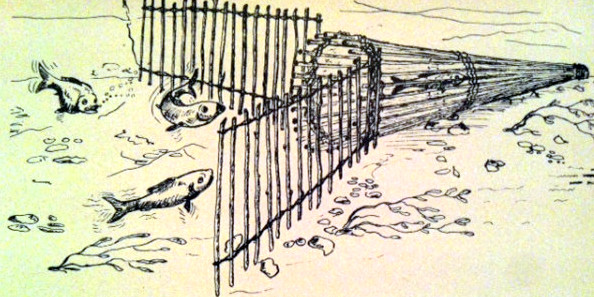

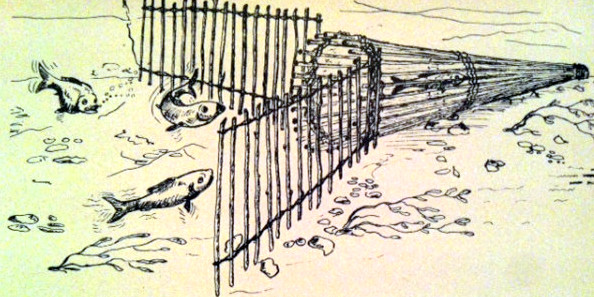

The Mapuche canoes or '' wampus'' were made of hollow trunks.[Bengoa 2003, pp. 72–73.] In the Chiloé Archipelago

The Chiloé Archipelago ( es, Archipiélago de Chiloé, , ) is a group of islands lying off the coast of Chile, in the Los Lagos Region. It is separated from mainland Chile by the Chacao Channel in the north, the Sea of Chiloé in the east and t ...

another type of watercraft was common: the ''dalca

The dalca or piragua is a type of canoe employed by the Chonos, a nomadic indigenous people of southern Chile, and Huilliche people living in Chiloé archipelago. It was a light boat and ideal for navigating local waterways, including between is ...

''. were made of planks and were mainly used for seafaring while wampus were used for navigating rivers and lakes. It is not known what kind of oars early Mapuches presumably used.[Bengoa 2003, p. 74.]

There are various reports in the 16th century of Mapuches using gold adornments.[ Gold was the most important metal in Pre-Hispanic Mapuche culture.][

]

Early Hispanic period (1536–1598)

First contacts (1536–1550)

The Spanish expansion into Chile was an offshoot of the conquest of Peru.

The Spanish expansion into Chile was an offshoot of the conquest of Peru.[Villalobos ''et al''. 1974, pp. 91−93.] Diego de Almagro

Diego de Almagro (; – July 8, 1538), also known as El Adelantado and El Viejo, was a Spanish conquistador known for his exploits in western South America. He participated with Francisco Pizarro in the Spanish conquest of Peru. While sub ...

amassed a large expedition of about 500 Spaniards and thousands of yanaconas

Yanakuna were originally individuals in the Inca Empire who left the ayllu system and worked full-time at a variety of tasks for the Inca, the ''quya'' (Inca queen), or the religious establishment. A few members of this serving class enjoyed high s ...

and arrived at the Aconcagua Valley in 1536. From there he sent Gómez de Alvarado

Gómez de Alvarado y Contreras (; 1482 – September 1542) was a Spanish ''conquistador'' and explorer. He was a member of the Alvarado family and the older brother of the famous ''conquistador'' Pedro de Alvarado.

Alvarado participated in ...

south in charge of a scouting troop. Alvarado reached the Itata River

The Itata River flows in the Ñuble Region, southern Chile.

Until the Conquest of Chile, the Itata was the natural limit between the Mapuche, located to the south, and Picunche, to the north.

See also

*Itata

*List of rivers in Chile

This list o ...

where he engaged in the Battle of Reynogüelén with local Mapuches. Alvarado then returned north and Diego de Almagro's expedition returned to Peru since they had not found the riches they expected.[

Another conquistador, ]Pedro de Valdivia

Pedro Gutiérrez de Valdivia or Valdiva (; April 17, 1497 – December 25, 1553) was a Spanish conquistador and the first royal governor of Chile. After serving with the Spanish army in Italy and Flanders, he was sent to South America in 1534, whe ...

, arrived in Chile from Cuzco

Cusco, often spelled Cuzco (; qu, Qusqu ()), is a city in Southeastern Peru near the Urubamba Valley of the Andes mountain range. It is the capital of the Cusco Region and of the Cusco Province. The city is the seventh most populous in Peru; ...

in 1541 and founded Santiago

Santiago (, ; ), also known as Santiago de Chile, is the capital and largest city of Chile as well as one of the largest cities in the Americas. It is the center of Chile's most densely populated region, the Santiago Metropolitan Region, whose ...

that year.[Villalobos ''et al''. 1974, pp. 96−97.] In 1544 captain Juan Bautista Pastene

200px, Map showing the September 1544 expedition led by Pastene.

Giovanni Battista Pastene (1507–1580) was a Genoese maritime explorer who, while in the service of the Spanish crown, explored the coasts of Panama, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru ...

explored the coast of Chile to latitude 41° S.[Villalobos ''et al''. 1974, pp. 98−99.] The northern Mapuche, better known as Promaucaes Promaucae, also spelled as ''Promaucas'' or ''Purumaucas'' (from Quechua ''purum awqa'': wild enemy), were an indigenous pre-Columbian Mapuche tribal group that lived in the present territory of Chile, south of the Maipo River basin of Santiago, Ch ...

or Picunche

The Picunche (a Mapudungun word meaning "North People"), also referred to as ''picones'' by the Spanish, were a Mapudungun-speaking people living to the north of the Mapuches or Araucanians (a name given to those Mapuche living between the Itata an ...

s, unsuccessfully tried to resist the Spanish conquest.[Bengoa 2003, pp. 250–251.] Northern Mapuche groups appear to have responded to the Spanish conquest abandoning their best agricultural lands and moving to remote localities away from the Spanish.[León 1991, p. 14.] In this context one of the reasons the Spanish had to establish the city of La Serena in 1544 was to control Mapuche groups that had begun to migrate north following the Spanish founding of Santiago.[León 1991, p. 15.] According to chronicler Francisco de Riberos northern Mapuche put cultivation on hold for more than five years.[ 17th century Jesuit Diego de Rosales wrote that this was a coordinated strategy that was decided by a large assembly of many tribes.][ The Spanish found themselves in great distress as a result of a lack of supplies, but ultimately this strategy was unsuccessful in forcing Spanish conquerors out of Central Chile.][León 1991, p. 16.]

War with Spaniards (1550–1598)

In 1550 Pedro de Valdivia, who aimed to control all of Chile to the Straits of Magellan

The Strait of Magellan (), also called the Straits of Magellan, is a navigable sea route in southern Chile separating mainland South America to the north and Tierra del Fuego to the south. The strait is considered the most important natural pass ...

, traveled southward to conquer Mapuche territory.[ Between 1550 and 1553 the Spanish founded several cities in Mapuche lands including Concepción, ]Valdivia

Valdivia (; Mapuche: Ainil) is a city and commune in southern Chile, administered by the Municipality of Valdivia. The city is named after its founder Pedro de Valdivia and is located at the confluence of the Calle-Calle, Valdivia, and Cau-Cau R ...

, Imperial

Imperial is that which relates to an empire, emperor, or imperialism.

Imperial or The Imperial may also refer to:

Places

United States

* Imperial, California

* Imperial, Missouri

* Imperial, Nebraska

* Imperial, Pennsylvania

* Imperial, Texa ...

, Villarrica and Angol

Angol is a commune and capital city of the Malleco Province in the Araucanía Region of southern Chile. It is located at the foot of the Nahuelbuta Range and next to the Vergara River, that permitted communications by small boats to the Bío-Bío ...

.[ The Spanish also established the forts of Arauco, ]Purén

Purén is a city (2002 pop. 12,868) and commune in Malleco Province of La Araucanía Region, Chile. It is located in the west base of the Nahuelbuta mountain range (650 km. south of Santiago). The economical activity of Purén is based in fo ...

and Tucapel

Tucapel is a town and commune in the Bío Bío Province, Bío Bío Region, Chile. It was once a region of Araucanía named for the Tucapel River. The name of the region derived from the rehue and aillarehue of the Moluche people of the area b ...

.[ The key areas of conflict that the Spanish attempted to secure south of Bío Bío River were the valleys around ]Cordillera de Nahuelbuta

The Nahuelbuta Range or Cordillera de Nahuelbuta () is a mountain range in Bio-Bio and Araucania Region, southern Chile. It is located along the Pacific coast and forms part of the larger Chilean Coast Range. The name of the range derives from th ...

. The Spanish designs for this region were to exploit the placer deposit

In geology, a placer deposit or placer is an accumulation of valuable minerals formed by gravity separation from a specific source rock during sedimentary processes. The name is from the Spanish word ''placer'', meaning "alluvial sand". Placer min ...

s of gold using unpaid Mapuche labour from the densely populated valleys.Arauco War

The Arauco War was a long-running conflict between colonial Spaniards and the Mapuche people, mostly fought in the Araucanía. The conflict began at first as a reaction to the Spanish conquerors attempting to establish cities and force Mapuche ...

, a long period of intermittent war between Mapuches and Spaniards, broke out. A contributing factor was the lack of a tradition of forced labour

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, violence including death, or other forms of ex ...

like the Andean mit'a

Mit'a () was mandatory service in the society of the Inca Empire. Its close relative, the regionally mandatory Minka is still in use in Quechua communities today and known as ''faena'' in Spanish.

Historians use the Hispanicized term ''mita'' to ...

among the Mapuches who largely refused to serve the Spanish.[ On the other hand, the Spanish, in particular those from Castile and ]Extremadura

Extremadura (; ext, Estremaúra; pt, Estremadura; Fala: ''Extremaúra'') is an autonomous community of Spain. Its capital city is Mérida, and its largest city is Badajoz. Located in the central-western part of the Iberian Peninsula, it ...

, came from an extremely violent society.[Bengoa 2003, p. 261.] Since the Spanish arrival in Araucanía in 1550, the Mapuches frequently laid siege to the Spanish cities in the 1550–1598 period.low intensity conflict

A low-intensity conflict (LIC) is a military conflict, usually localised, between two or more state or non-state groups which is below the intensity of conventional war. It involves the state's use of military forces applied selectively and with ...

.[Dillehay 2007, p. 335.]

The Mapuches, led by Caupolicán and Lautaro

Lautaro (Anglicized as 'Levtaru') ( arn, Lef-Traru " swift hawk") (; 1534? – April 29, 1557) was a young Mapuche toqui known for leading the indigenous resistance against Spanish conquest in Chile and developing the tactics that would conti ...

, succeeded in killing Pedro de Valdivia at the Battle of Tucapel

The Battle of Tucapel (also known as the Disaster of Tucapel) is the name given to a battle fought between Spanish conquistador forces led by Pedro de Valdivia and Mapuche (Araucanian) Indians under Lautaro that took place at Tucapel, Chile on D ...

in 1553.[ The outbreak of a ]typhus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposure.

...

plague, a drought

A drought is defined as drier than normal conditions.Douville, H., K. Raghavan, J. Renwick, R.P. Allan, P.A. Arias, M. Barlow, R. Cerezo-Mota, A. Cherchi, T.Y. Gan, J. Gergis, D. Jiang, A. Khan, W. Pokam Mba, D. Rosenfeld, J. Tierney, an ...

and a famine

A famine is a widespread scarcity of food, caused by several factors including war, natural disasters, crop failure, Demographic trap, population imbalance, widespread poverty, an Financial crisis, economic catastrophe or government policies. Th ...

prevented the Mapuches from taking further actions to expel the Spanish in 1554 and 1555.[Bengoa 2003, pp. 258–259.] Between 1556 and 1557 a small party of Mapuches commanded by Lautaro attempted to reach Santiago to liberate the whole of Central Chile

Central Chile (''Zona central'') is one of the five natural regions into which CORFO divided continental Chile in 1950. It is home to a majority of the Chilean population and includes the three largest metropolitan areas—Santiago, Valparaís ...

from Spanish rule.[ Lautaro's attempts ended in 1557 when he was killed in an ambush by the Spanish.][

The Spanish regrouped under the governorship of ]García Hurtado de Mendoza

García or Garcia may refer to:

People

* García (surname)

* Kings of Pamplona/Navarre

** García Íñiguez of Pamplona, king of Pamplona 851/2–882

** García Sánchez I of Pamplona, king of Pamplona 931–970

** García Sánchez II of Pam ...

(1558–1561) and managed to kill Caupolicán and Galvarino

Galvarino (died c. November 30, 1557) was a famous Mapuche warrior during the majority of the early part of the Arauco War. He fought and was taken prisoner along with one hundred and fifty other Mapuche, in the Battle of Lagunillas against gov ...

, two key Mapuche leaders. In addition during the rule of García Hurtado de Mendoza the Spanish reestablished Concepción and Angol that had been destroyed by Mapuches and founded two new cities in Mapuche territory: Osorno and Cañete.[Villalobos ''et al''. 1974, p. 102.] In 1567 Spaniards conquered Chiloé Archipelago

The Chiloé Archipelago ( es, Archipiélago de Chiloé, , ) is a group of islands lying off the coast of Chile, in the Los Lagos Region. It is separated from mainland Chile by the Chacao Channel in the north, the Sea of Chiloé in the east and t ...

which was inhabited by Huilliche

The Huilliche , Huiliche or Huilliche-Mapuche are the southern partiality of the Mapuche macroethnic group of Chile. Located in the Zona Sur, they inhabit both Futahuillimapu ("great land of the south") and, as the Cunco subgroup, the north hal ...

s.[Hanisch 1982, pp. 11–12][Villalobos ''et al''. 1974, p. 49.]

In the 1570s Pedro de Villagra

Pedro de Villagra y Martínez (1513 in Mombeltrán, Ávila Province – September 11, 1577 in Lima) was a Spanish soldier who participated in the conquest of Chile, being appointed its Royal Governor between 1563 and 1565.

His father was Juan d ...

massacred and subdued revolting Mapuches around the city of La Imperial. Warfare in Araucanía intensified in the 1590s.[Bengoa 2003, pp. 312–213.] Over time the Mapuche's of Purén

Purén is a city (2002 pop. 12,868) and commune in Malleco Province of La Araucanía Region, Chile. It is located in the west base of the Nahuelbuta mountain range (650 km. south of Santiago). The economical activity of Purén is based in fo ...

and to a lesser extent also Tucapel

Tucapel is a town and commune in the Bío Bío Province, Bío Bío Region, Chile. It was once a region of Araucanía named for the Tucapel River. The name of the region derived from the rehue and aillarehue of the Moluche people of the area b ...

gained a reputation of fierceness among Mapuches and Spaniards alike. This allowed the Purén Mapuches to rally other Mapuches in the war with the Spanish.[

]

Adaptations to the war

In the early battles with the Spaniards Mapuches had little success but with time the Mapuches of Arauco and Tucapel adapted by using horses and amassing the large quantities of troops necessary to defeat the Spanish.[ Mapuches learned from the Spanish to build forts in hills; they also began digging traps for Spanish horses, using helmets and wooden shields against ]arquebus

An arquebus ( ) is a form of long gun that appeared in Europe and the Ottoman Empire during the 15th century. An infantryman armed with an arquebus is called an arquebusier.

Although the term ''arquebus'', derived from the Dutch word ''Haakbus ...

es.[ Mapuche warfare evolved toward ]guerrilla tactics

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare in which small groups of combatants, such as paramilitary personnel, armed civilians, or irregulars, use military tactics including ambushes, sabotage, raids, petty warfare, hit-and-run ta ...

including the use of ambushes.[ The killing of Pedro de Valdivia in 1553 marked a rupture with the earlier ritual warfare tradition of the Mapuches.]aillarehue

Aillarehue or Ayllarehue (from the Mapudungun: ayllarewe/ayjarewe: "nine rehues"); a confederation of rehues or family-based units (lof) that dominated a region or province. It was the old administrative and territorial division of the Mapuche, H ...

'', a new macro-scale political unit consisting of several ''rehue

A rehue (Mapudungun spelling rewe) or kemukemu is a type of pillar-like sacred altar used by the Mapuche of Chile in many of their ceremonies.

Altar/Axis mundi

The ''rehue'' is a carved tree trunk set in the ground, surrounded by a hedge o ...

'', appeared in the late 16th century.[ This scaling-up of political organization continued until the early 17th century when the '']butalmapu Butalmapu or Fütalmapu is the name in Mapudungun for "great land", which were one of the great confederations wherein the Mapuche people organized themselves in case of war. These confederations corresponded to the great geographic areas inhabited ...

'' emerged, each of these units made up of several aillarehues.[ At a practical level this meant that the Mapuches achieved a "supra-local level of military solidarity" without having state organization.][Dillehay 2007, p. 337–338.] By the late 16th century a handful of powerful Mapuche warlord

A warlord is a person who exercises military, economic, and political control over a region in a country without a strong national government; largely because of coercive control over the armed forces. Warlords have existed throughout much of h ...

s had emerged near La Frontera.[Bengoa 2003, pp. 310–311.]

Changes in population patterns

The Mapuche population decreased following contact with the Spanish invaders. Epidemic

An epidemic (from Ancient Greek, Greek ἐπί ''epi'' "upon or above" and δῆμος ''demos'' "people") is the rapid spread of disease to a large number of patients among a given population within an area in a short period of time.

Epidemics ...

s decimated much of the population as did the war with the Spanish.[Otero 2006, p. 25.] Others died in the Spanish gold mines.[Bengoa 2003, pp. 252–253.] From archaeological evidence it has been suggested that the Mapuche of Purén

Purén is a city (2002 pop. 12,868) and commune in Malleco Province of La Araucanía Region, Chile. It is located in the west base of the Nahuelbuta mountain range (650 km. south of Santiago). The economical activity of Purén is based in fo ...

and Lumaco

Lumaco is a town and commune in Malleco Province in the Araucanía Region of Chile. Its name in Mapudungun means "water of '' luma''". Lumaco is located to northeast of Temuco and from Angol. It shares a boundary to the north with the comm ...

valley abandoned the very scattered population pattern to form denser villages as a response to the war with the Spanish.forest

A forest is an area of land dominated by trees. Hundreds of definitions of forest are used throughout the world, incorporating factors such as tree density, tree height, land use, legal standing, and ecological function. The United Nations' ...

.[

By the 1630s it was noted by the Spanish of La Serena that Mapuches (Picunches) from the Corregimiento of Santiago, likely from Aconcagua Valley, had migrated north settling in the ]Combarbalá

Combarbalá is the capital city of the commune of Combarbala. It is located in the Limarí Province, Region of Coquimbo, at an elevation of 900 m (2,952 ft). It is known for the tourist astronomic observatory Cruz del Sur; the petro ...

and Cogotí. This migration appears to have been done freely without Spanish interference.[Téllez 2008, p. 46.]

In the late 16th century the indigenous Picunche began a slow process of assimilation by losing their indigenous identity. This happened by a process of mestization by gradually abandoning their villages (''pueblo de indios

In the Southwestern United States, Pueblo (capitalized) refers to the Native tribes of Puebloans having fixed-location communities with permanent buildings which also are called pueblos (lowercased). The Spanish explorers of northern New Spain ...

'') to settle in nearby Spanish haciendas. There Picunches mingled with disparate indigenous peoples brought in from Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = Seal (emblem), National seal

, national_motto = "Fi ...

, Tucumán, Araucanía (Mapuche

The Mapuche ( (Mapuche & Spanish: )) are a group of indigenous inhabitants of south-central Chile and southwestern Argentina, including parts of Patagonia. The collective term refers to a wide-ranging ethnicity composed of various groups who sha ...

), Chiloé (Huilliche

The Huilliche , Huiliche or Huilliche-Mapuche are the southern partiality of the Mapuche macroethnic group of Chile. Located in the Zona Sur, they inhabit both Futahuillimapu ("great land of the south") and, as the Cunco subgroup, the north hal ...

, Cunco, Chono, Poyas) and Cuyo (Huarpe

The Huarpes or Warpes are an indigenous people of Argentina, living in the Cuyo region. Some scholars assume that in the Huarpe language, this word means "sandy ground," but according to ''Arte y Vocabulario de la lengua general del Reino de Chi ...

[Villalobos ''et al''. 1974, pp. 166–170.]).[

]

Independence and war (1598–1641)

Fall of the Spanish cities

A watershed event happened in 1598. That year a party of warriors from Purén

Purén is a city (2002 pop. 12,868) and commune in Malleco Province of La Araucanía Region, Chile. It is located in the west base of the Nahuelbuta mountain range (650 km. south of Santiago). The economical activity of Purén is based in fo ...

were returning south from a raid against the surroundings of Chillán

Chillán () is the capital city of the Ñuble Region in the Diguillín Province of Chile located about south of the country's capital, Santiago, near the geographical center of the country. It is the capital of the new Ñuble Region since 6 Sept ...

. On their way back home they ambushed Martín García Óñez de Loyola

Don Martín García Óñez de Loyola (1549 in Azpeitia, Gipuzkoa – December 24, 1598 at Curalaba) was a Spanish Basque soldier and Royal Governor of the Captaincy General of Chile. Very likely Ignatius of Loyola, the founder of the Society of ...

and his troops who were sleeping without any night watch. It is not clear if they found the Spanish by accident or if they had followed them. The warriors, led by Pelantaro

Pelantaro or Pelantarú (; from arn, pelontraru, lit=Shining Caracara) was one of the vice toquis of Paillamachu, the ''toqui'' or military leader of the Mapuche people during the Mapuche uprising in 1598. Pelantaro and his lieutenants Angana ...

, killed both the governor and all his troops.[Bengoa 2003, pp. 320–321.]

In the years following the Battle of Curalaba a general uprising developed among the Mapuches and Huilliches. The Spanish cities of Angol

Angol is a commune and capital city of the Malleco Province in the Araucanía Region of southern Chile. It is located at the foot of the Nahuelbuta Range and next to the Vergara River, that permitted communications by small boats to the Bío-Bío ...

, La Imperial, Osorno, Santa Cruz de Oñez

Santa Claus, also known as Father Christmas, Saint Nicholas, Saint Nick, Kris Kringle, or simply Santa, is a legendary figure originating in Western Christian culture who is said to bring children gifts during the late evening and overnight ...

, Valdivia

Valdivia (; Mapuche: Ainil) is a city and commune in southern Chile, administered by the Municipality of Valdivia. The city is named after its founder Pedro de Valdivia and is located at the confluence of the Calle-Calle, Valdivia, and Cau-Cau R ...

and Villarrica were either destroyed or abandoned.[Villalobos ''et al.'' 1974, p. 109.] Only Chillán

Chillán () is the capital city of the Ñuble Region in the Diguillín Province of Chile located about south of the country's capital, Santiago, near the geographical center of the country. It is the capital of the new Ñuble Region since 6 Sept ...

and Concepción resisted the Mapuche sieges and attacks.[Bengoa 2003, pp. 324–325.] With the exception of Chiloé Archipelago

The Chiloé Archipelago ( es, Archipiélago de Chiloé, , ) is a group of islands lying off the coast of Chile, in the Los Lagos Region. It is separated from mainland Chile by the Chacao Channel in the north, the Sea of Chiloé in the east and t ...

all the Chilean territory south of Bío Bío River became free of Spanish rule.[

Chiloé did however also suffer Mapuche (Huilliche) attacks when in 1600 local Huilliche joined the Dutch ]corsair

A corsair is a privateer or pirate, especially:

* Barbary corsair, Ottoman and Berber pirates and privateers operating from North Africa

* French corsairs, privateers operating on behalf of the French crown

Corsair may also refer to:

Arts and ...

Baltazar de Cordes

Baltazar de Cordes (16th century–17th century), the brother of Simon de Cordes, was a Dutch corsair who fought against the Spanish during the early 17th century.

Born in the Netherlands in the mid-16th century, Cordes began sailing for the ...

to attack the Spanish settlement of Castro

Castro is a Romance language word that originally derived from Latin ''castrum'', a pre-Roman military camp or fortification (cf: Greek: ''kastron''; Proto-Celtic:''*Kassrik;'' br, kaer, *kastro). The English-language equivalent is '' chester''.

...

.[Clark 2006, p. 13.] As the Spanish confirmed their suspicions of Dutch plans to establish themselves at the ruins of Valdivia they attempted to re-establish Spanish rule there before the Dutch arrived again.[Bengoa 2003, pp. 450–451.] The Spanish attempts were thwarted in the 1630s when Mapuches did not allow the Spanish to pass by their territory.[

]

Captured Spanish women

With the fall of the Spanish cities thousands of Spanish were either killed or turned into captives. Contemporary chronicler Alonso González de Nájera writes that Mapuches killed more than three thousand Spanish and took over 500 women as captives. Many children and Spanish clergy were also captured.[ In the case of the women it was, in the words of González de Nájera, "to take advantage of them" (Spanish: ''aprovecharse de ellas''). While some Spanish women were recovered in Spanish raids, others were only set free in agreements following the Parliament of Quillín in 1641.][ Some Spanish women became accustomed to Mapuche life and stayed voluntarily.][ Women in captivity gave birth to a large number of ]mestizo

(; ; fem. ) is a term used for racial classification to refer to a person of mixed Ethnic groups in Europe, European and Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Indigenous American ancestry. In certain regions such as Latin America, it may also r ...

s who were rejected by the Spanish but accepted among the Mapuches.[ These women's children may have had a significant demographic impact on Mapuche society, long ravaged by war and epidemics.][ The capture of women during the ]Destruction of the Seven Cities

The Destruction of the Seven Cities ( es, Destrucción de las siete ciudades) is a term used in Chilean historiography to refer to the destruction or abandonment of seven major Spanish outposts in southern Chile around 1600, caused by the Mapuc ...

initiated a tradition of abductions of Spanish women in the 17th century by Mapuches.[

]

Adoption of Old World crops, animals and technologies

Overall the Mapuche of Araucanía appear to have been very selective in adopting Spanish technologies and species. This meant that the Mapuche way of living remained largely the same after Spanish contact. The scant adoption of Spanish technology has been characterized as a means of cultural resistance.[

Mapuches of Araucanía were quick to adopt the horse and wheat cultivation from the Spanish.]Chiloé Archipelago

The Chiloé Archipelago ( es, Archipiélago de Chiloé, , ) is a group of islands lying off the coast of Chile, in the Los Lagos Region. It is separated from mainland Chile by the Chacao Channel in the north, the Sea of Chiloé in the east and t ...

wheat came to be grown in lesser quantities compared to the native potatoes, given the adverse climate.[ Instead, on these islands the introduction of ]pig

The pig (''Sus domesticus''), often called swine, hog, or domestic pig when distinguishing from other members of the genus '' Sus'', is an omnivorous, domesticated, even-toed, hoofed mammal. It is variously considered a subspecies of ''Sus ...

s and apple tree

An apple is an edible fruit produced by an apple tree (''Malus domestica''). Apple trees are cultivated worldwide and are the most widely grown species in the genus ''Malus''. The tree originated in Central Asia, where its wild ancestor, ' ...

s by the Spanish proved a success. Pigs benefited from abundant shellfish

Shellfish is a colloquial and fisheries term for exoskeleton-bearing aquatic invertebrates used as food, including various species of molluscs, crustaceans, and echinoderms. Although most kinds of shellfish are harvested from saltwater envir ...

and algae

Algae (; singular alga ) is an informal term for a large and diverse group of photosynthetic eukaryotic organisms. It is a polyphyletic grouping that includes species from multiple distinct clades. Included organisms range from unicellular mic ...

exposed by the large tide

Tides are the rise and fall of sea levels caused by the combined effects of the gravity, gravitational forces exerted by the Moon (and to a much lesser extent, the Sun) and are also caused by the Earth and Moon orbiting one another.

Tide t ...

s.[

Until the arrival of the Spanish the Mapuches had had ]chilihueque

The chilihueque or hueque was a South American camelid variety or species that existed in central and south-central Chile in Pre-Hispanic and colonial times. There are two main hypotheses on their status among South American camelids: the firs ...

(llama

The llama (; ) (''Lama glama'') is a domesticated South American camelid, widely used as a List of meat animals, meat and pack animal by Inca empire, Andean cultures since the Pre-Columbian era.

Llamas are social animals and live with othe ...

) livestock. The introduction of sheep caused some competition among both domestic species. Anecdotal evidence of the mid-17th century show that both species coexisted but that there were many more sheep than chilihueques. The decline of chilihueques reached a point in the late 18th century when only the Mapuche from Mariquina and Huequén next to Angol

Angol is a commune and capital city of the Malleco Province in the Araucanía Region of southern Chile. It is located at the foot of the Nahuelbuta Range and next to the Vergara River, that permitted communications by small boats to the Bío-Bío ...

raised the animal.

Jesuit activity

The first Jesuits arrived in Chile in 1593 and based themselves in Concepción to Christianize the Araucanía Mapuches.Luis de Valdivia

Luis de Valdivia (; 1560 – November 5, 1642) was a Spanish Jesuit missionary who defended the rights of the natives of Chile and pleaded for the reduction of the hostilities with the Mapuches in the Arauco War.

Following the 1598 revolt of the M ...

believed Mapuches could be voluntarily converted to Christianity only if there was peace.Defensive War

A defensive war (german: Verteidigungskrieg) is one of the causes that justify war by the criteria of the Just War tradition. It means a war where at least one nation is mainly trying to defend itself from another, as opposed to a war where both s ...

with Spanish authorities. Luis de Valdivia took away warlord Anganamón's wives as the Catholic church opposed polygamy. Anganamón retaliated, killing three Jesuit missionaries on December 14, 1612.[ This incident did not stop the Jesuits' Christianization attempts and Jesuits continued their activity until their expulsion from Chile in 1767. Activity was centered around Spanish cities from which missionary excursions departed.][ No permanent mission was established in free Mapuche lands during the 17th or 18th century.][Clark 2006, p. 15.] To convert the Mapuches Jesuits studied and learned their language and customs. Contrasting with their high political impact in the 1610s and 1620s, the Jesuits had little success in their conversion attempts.[

]

Slavery of Mapuches

Formal slavery of indigenous people was prohibited by the Spanish Crown. The 1598–1604 Mapuche

The Mapuche ( (Mapuche & Spanish: )) are a group of indigenous inhabitants of south-central Chile and southwestern Argentina, including parts of Patagonia. The collective term refers to a wide-ranging ethnicity composed of various groups who sha ...

uprising that ended with the Destruction of the Seven Cities