Mycobacterium tuberculosis on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (M. tb), also known as Koch's bacillus, is a species of

''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (M. tb), also known as Koch's bacillus, is a species of

Other bacteria are commonly identified with a microscope by staining them with

Other bacteria are commonly identified with a microscope by staining them with

TB database: an integrated platform for Tuberculosis research

*

Database on Mycobacterium tuberculosis genetics

{{Authority control Acid-fast bacilli

''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (M. tb), also known as Koch's bacillus, is a species of

''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (M. tb), also known as Koch's bacillus, is a species of pathogenic bacteria

Pathogenic bacteria are bacteria that can cause disease. This article focuses on the bacteria that are pathogenic to humans. Most species of bacteria are harmless and many are Probiotic, beneficial but others can cause infectious diseases. The nu ...

in the family Mycobacteriaceae and the causative agent of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

.

First discovered in 1882 by Robert Koch

Heinrich Hermann Robert Koch ( ; ; 11 December 1843 – 27 May 1910) was a German physician and microbiologist. As the discoverer of the specific causative agents of deadly infectious diseases including tuberculosis, cholera and anthrax, he i ...

, ''M. tuberculosis'' has an unusual, waxy coating on its cell surface primarily due to the presence of mycolic acid

Mycolic acids are long fatty acids found in the cell walls of Mycobacteriales taxon, a group of bacteria that includes ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'', the causative agent of the disease tuberculosis. They form the major component of the cell wall ...

. This coating makes the cells impervious to Gram staining, and as a result, ''M. tuberculosis'' can appear weakly Gram-positive. Acid-fast

Acid-fastness is a physical property of certain bacterial and eukaryotic cells, as well as some sub-cellular structures, specifically their resistance to decolorization by acids during laboratory staining procedures. Once stained as part of a sa ...

stains such as Ziehl–Neelsen, or fluorescent

Fluorescence is one of two kinds of photoluminescence, the emission of light by a substance that has absorbed light or other electromagnetic radiation. When exposed to ultraviolet radiation, many substances will glow (fluoresce) with color ...

stains such as auramine are used instead to identify ''M. tuberculosis'' with a microscope. The physiology of ''M. tuberculosis'' is highly aerobic and requires high levels of oxygen. Primarily a pathogen of the mammalian respiratory system

The respiratory system (also respiratory apparatus, ventilatory system) is a biological system consisting of specific organs and structures used for gas exchange in animals and plants. The anatomy and physiology that make this happen varies grea ...

, it infects the lungs. The most frequently used diagnostic methods for tuberculosis are the tuberculin skin test

The Mantoux test or Mendel–Mantoux test (also known as the Mantoux screening test, tuberculin sensitivity test, Pirquet test, or PPD test for purified protein derivative) is a tool for screening for tuberculosis (TB) and for tuberculosis dia ...

, acid-fast stain, culture

Culture ( ) is a concept that encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and Social norm, norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, Social norm, customs, capabilities, Attitude (psychology), attitudes ...

, and polymerase chain reaction

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a method widely used to make millions to billions of copies of a specific DNA sample rapidly, allowing scientists to amplify a very small sample of DNA (or a part of it) sufficiently to enable detailed st ...

.

The ''M. tuberculosis'' genome

A genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding genes, other functional regions of the genome such as ...

was sequenced in 1998.

Microbiology

''M. tuberculosis'' requires oxygen to grow, and is nonmotile. It divides every 18–24 hours. This is extremely slow compared with other bacteria, which tend to have division times measured in minutes (''Escherichia coli

''Escherichia coli'' ( )Wells, J. C. (2000) Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. Harlow ngland Pearson Education Ltd. is a gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, rod-shaped, coliform bacterium of the genus '' Escherichia'' that is commonly fo ...

'' can divide roughly every 20 minutes). It is a small bacillus

''Bacillus'', from Latin "bacillus", meaning "little staff, wand", is a genus of Gram-positive, rod-shaped bacteria, a member of the phylum ''Bacillota'', with 266 named species. The term is also used to describe the shape (rod) of other so-sh ...

that can withstand weak disinfectant

A disinfectant is a chemical substance or compound used to inactivate or destroy microorganisms on inert surfaces. Disinfection does not necessarily kill all microorganisms, especially resistant bacterial spores; it is less effective than ...

s and can survive in a dry state for weeks. Its unusual cell wall

A cell wall is a structural layer that surrounds some Cell type, cell types, found immediately outside the cell membrane. It can be tough, flexible, and sometimes rigid. Primarily, it provides the cell with structural support, shape, protection, ...

, rich in lipids

Lipids are a broad group of organic compounds which include fats, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins (such as vitamins Vitamin A, A, Vitamin D, D, Vitamin E, E and Vitamin K, K), monoglycerides, diglycerides, phospholipids, and others. The fu ...

such as mycolic acid

Mycolic acids are long fatty acids found in the cell walls of Mycobacteriales taxon, a group of bacteria that includes ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'', the causative agent of the disease tuberculosis. They form the major component of the cell wall ...

and cord factor

Cord factor, or trehalose dimycolate (TDM), is a glycolipid molecule found in the cell wall of ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' and similar species. It is the primary lipid found on the exterior of ''M. tuberculosis'' cells. Cord factor influences ...

glycolipid

Glycolipids () are lipids with a carbohydrate attached by a glycosidic (covalent) bond. Their role is to maintain the stability of the cell membrane and to facilitate cellular recognition, which is crucial to the immune response and in the c ...

, is likely responsible for its resistance to desiccation

Desiccation is the state of extreme dryness, or the process of extreme drying. A desiccant is a hygroscopic (attracts and holds water) substance that induces or sustains such a state in its local vicinity in a moderately sealed container. The ...

and is a key virulence factor

Virulence factors (preferably known as pathogenicity factors or effectors in botany) are cellular structures, molecules and regulatory systems that enable microbial pathogens (bacteria, viruses, fungi, and protozoa) to achieve the following:

* c ...

.

Microscopy

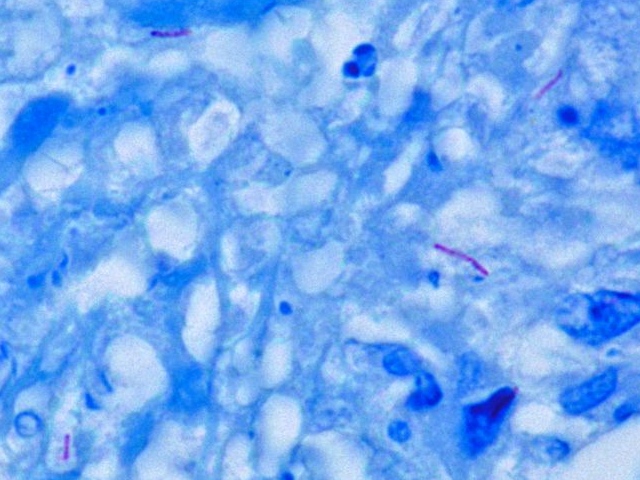

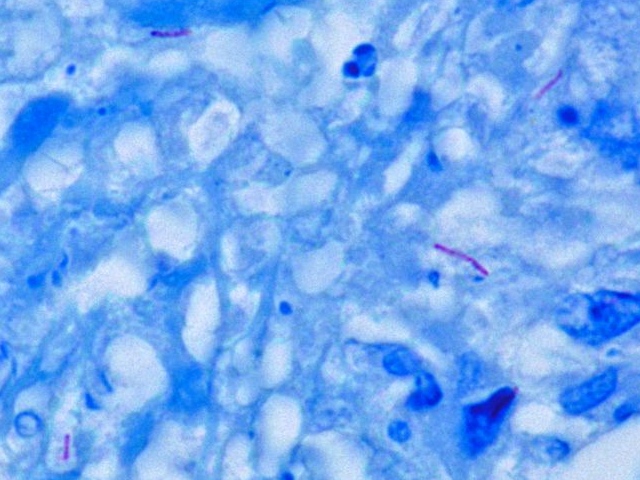

Other bacteria are commonly identified with a microscope by staining them with

Other bacteria are commonly identified with a microscope by staining them with Gram stain

Gram stain (Gram staining or Gram's method), is a method of staining used to classify bacterial species into two large groups: gram-positive bacteria and gram-negative bacteria. It may also be used to diagnose a fungal infection. The name comes ...

. However, the mycolic acid in the cell wall of ''M. tuberculosis'' does not absorb the stain. Instead, acid-fast stains such as Ziehl–Neelsen stain, or fluorescent stains such as auramine are used. Cells are curved rod-shaped and are often seen wrapped together, due to the presence of fatty acids in the cell wall that stick together. This appearance is referred to as cording, like strands of cord that make up a rope. ''M. tuberculosis'' is characterized in tissue by caseating granulomas containing Langhans giant cell

Langhans giant cells (LGC) are giant cells found in granulomatous conditions.

They are formed by the fusion of epithelioid cells (macrophages), and contain nuclei arranged in a horseshoe-shaped pattern in the cell periphery.

Although tradit ...

s, which have a "horseshoe" pattern of nuclei.

Culture

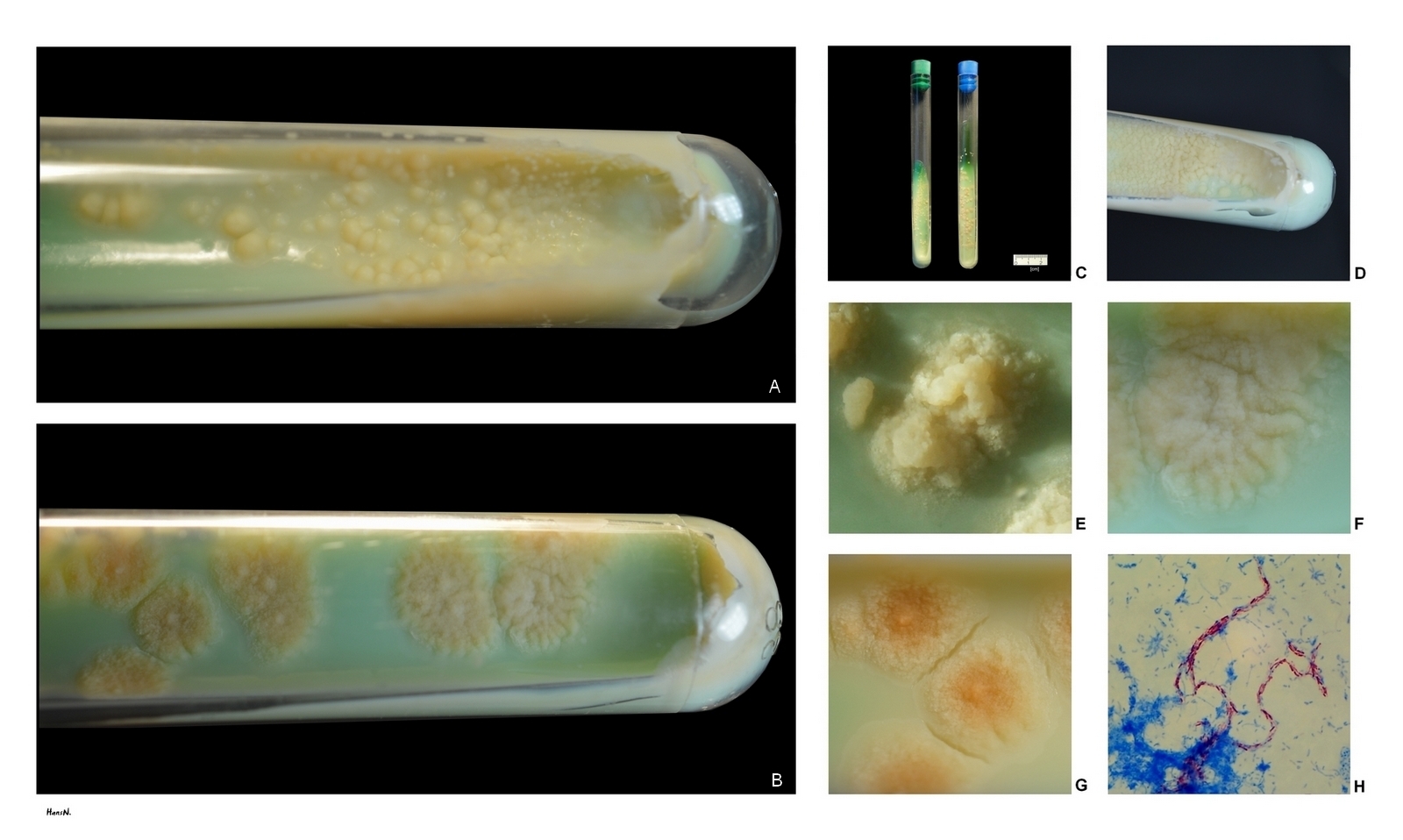

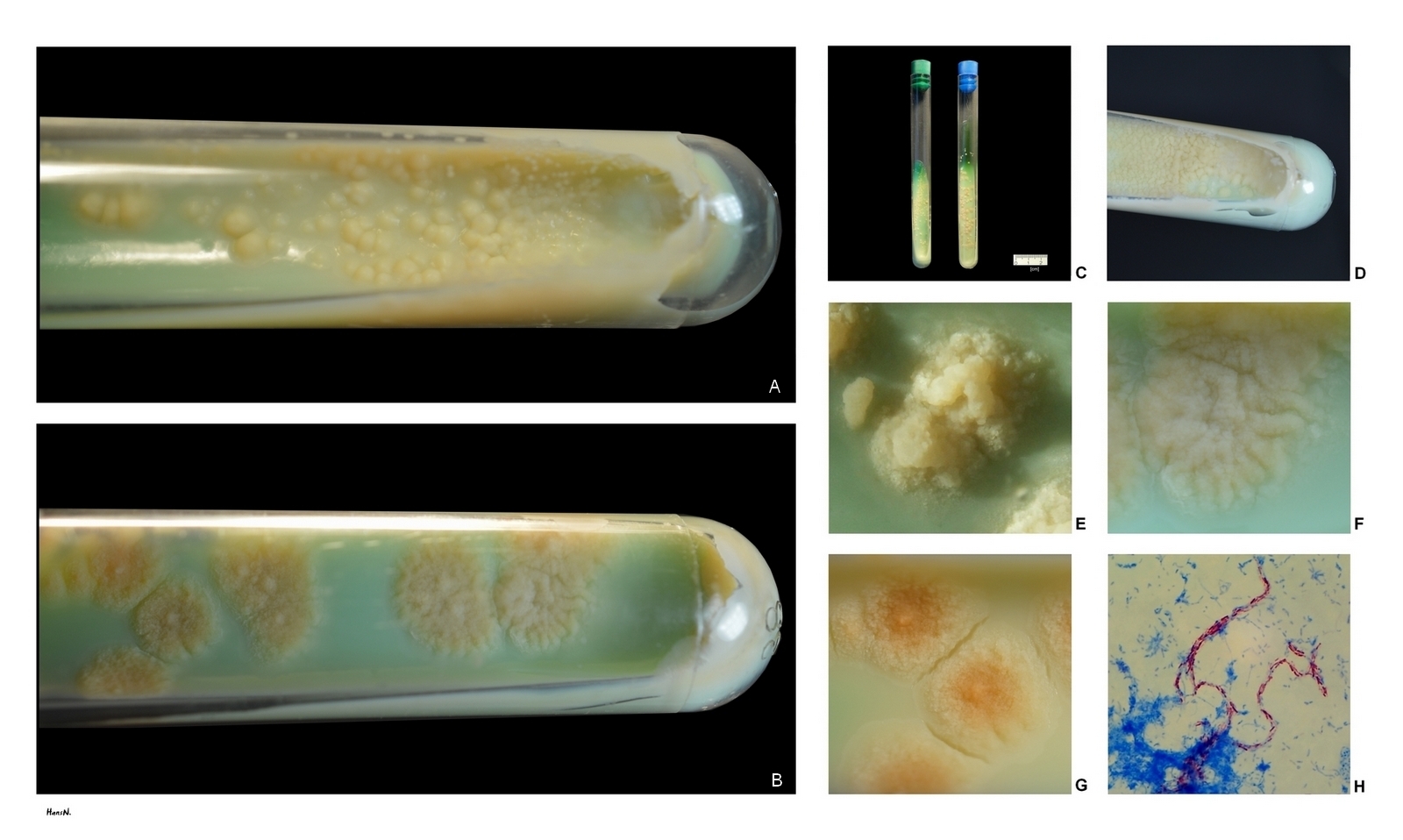

''M. tuberculosis'' can be grown in the laboratory. Compared to other commonly studied bacteria, ''M. tuberculosis'' has a remarkably slow growth rate, doubling roughly once per day. Commonly usedmedia

Media may refer to:

Communication

* Means of communication, tools and channels used to deliver information or data

** Advertising media, various media, content, buying and placement for advertising

** Interactive media, media that is inter ...

include liquids such as Middlebrook 7H9 or 7H12, egg-based solid media such as Lowenstein-Jensen, and solid agar-based such as Middlebrook 7H11 or 7H10. Visible colonies require several weeks to grow on agar plates. Mycobacteria growth indicator tubes can contain a gel that emits fluorescent light if mycobacteria are grown. It is distinguished from other mycobacteria by its production of catalase

Catalase is a common enzyme found in nearly all living organisms exposed to oxygen (such as bacteria, plants, and animals) which catalyzes the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide to water and oxygen. It is a very important enzyme in protecting ...

and niacin. Other tests to confirm its identity include gene probes and MALDI-TOF.

Morphology

Analysis of ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' viascanning electron microscope

A scanning electron microscope (SEM) is a type of electron microscope that produces images of a sample by scanning the surface with a focused beam of electrons. The electrons interact with atoms in the sample, producing various signals that ...

shows the bacteria are in length with an average diameter of . The outer membrane and plasma membrane surface areas were measured to be and , respectively. The cell, outer membrane, periplasm, plasma membrane, and cytoplasm volumes were (= μm3), , , , and , respectively. The average total ribosome

Ribosomes () are molecular machine, macromolecular machines, found within all cell (biology), cells, that perform Translation (biology), biological protein synthesis (messenger RNA translation). Ribosomes link amino acids together in the order s ...

number was with ribosome density about .

Related Mycobacterium species

''M. tuberculosis'' is part of a genetically related group of Mycobacterium species that has at least nine members: * ''M. tuberculosis'' ''sensu stricto'' * '' M. africanum'' * '' M. canettii'' * '' M. bovis'' * '' M. caprae'' * '' M. microti'' * '' M. pinnipedii'' * '' M. mungi'' * '' M. orygis''Pathophysiology

Humans are the only known reservoirs of ''M. tuberculosis''. A misconception is that ''M. tuberculosis'' can be spread by shaking hands, making contact with toilet seats, sharing food or drink, or sharing toothbrushes. However, major spread is through air droplets originating from a person who has the disease either coughing, sneezing, speaking, or singing. When in the lungs, ''M. tuberculosis'' is phagocytosed byalveolar macrophage

An alveolar macrophage, pulmonary macrophage, (or dust cell, or dust eater) is a type of macrophage, a phagocytosis#Professional phagocytic cells, professional phagocyte, found in the airways and at the level of the pulmonary alveolus, alveoli in ...

s, but they are unable to kill and digest the bacterium. Its cell wall is made of cord factor

Cord factor, or trehalose dimycolate (TDM), is a glycolipid molecule found in the cell wall of ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' and similar species. It is the primary lipid found on the exterior of ''M. tuberculosis'' cells. Cord factor influences ...

glycolipids that inhibit the fusion of the phagosome

In cell biology, a phagosome is a vesicle formed around a particle engulfed by a phagocyte via phagocytosis. Professional phagocytes include macrophages, neutrophils, and dendritic cells (DCs).

A phagosome is formed by the fusion of the cel ...

with the lysosome

A lysosome () is a membrane-bound organelle that is found in all mammalian cells, with the exception of red blood cells (erythrocytes). There are normally hundreds of lysosomes in the cytosol, where they function as the cell’s degradation cent ...

, which contains a host of antibacterial factors.

Specifically, ''M. tuberculosis'' blocks the bridging molecule, early endosomal autoantigen 1 ( EEA1); however, this blockade does not prevent fusion of vesicles filled with nutrients. In addition, production of the diterpene isotuberculosinol prevents maturation of the phagosome. The bacteria also evades macrophage-killing by neutralizing reactive nitrogen intermediates. More recently, ''M. tuberculosis'' has been shown to secrete and cover itself in 1-tuberculosinyladenosine (1-TbAd), a special nucleoside

Nucleosides are glycosylamines that can be thought of as nucleotides without a phosphate group. A nucleoside consists simply of a nucleobase (also termed a nitrogenous base) and a five-carbon sugar (ribose or 2'-deoxyribose) whereas a nucleotid ...

that acts as an antacid

An antacid is a substance which neutralization (chemistry), neutralizes gastric acid, stomach acidity and is used to relieve heartburn, indigestion, or an upset stomach. Some antacids have been used in the treatment of constipation and diarrhe ...

, allowing it to neutralize pH and induce swelling in lysosomes.

In ''M. tuberculosis'' infections, PPM1A levels were found to be upregulated, and this, in turn, would impact the normal apoptotic response of macrophages to clear pathogens, as PPM1A is involved in the intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways. Hence, when PPM1A levels were increased, the expression of it inhibits the two apoptotic pathways. With kinome analysis, the JNK/AP-1 signalling pathway was found to be a downstream effector that PPM1A has a part to play in, and the apoptotic pathway in macrophages are controlled in this manner. As a result of having apoptosis being suppressed, it provides ''M. tuberculosis'' with a safe replicative niche, and so the bacteria are able to maintain a latent state for a prolonged time.

Granuloma

A granuloma is an aggregation of macrophages (along with other cells) that forms in response to chronic inflammation. This occurs when the immune system attempts to isolate foreign substances that it is otherwise unable to eliminate. Such sub ...

s, organized aggregates of immune cells, are a hallmark feature of tuberculosis infection. Granulomas play dual roles during infection: they regulate the immune response and minimize tissue damage, but also can aid in the expansion of infection.

The ability to construct ''M. tuberculosis'' mutants and test individual gene products for specific functions has significantly advanced the understanding of its pathogenesis

In pathology, pathogenesis is the process by which a disease or disorder develops. It can include factors which contribute not only to the onset of the disease or disorder, but also to its progression and maintenance. The word comes .

Descript ...

and virulence factors. Many secreted and exported proteins are known to be important in pathogenesis. For example, one such virulence factor is cord factor

Cord factor, or trehalose dimycolate (TDM), is a glycolipid molecule found in the cell wall of ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' and similar species. It is the primary lipid found on the exterior of ''M. tuberculosis'' cells. Cord factor influences ...

(trehalose dimycolate), which serves to increase survival within its host. Resistant strains of ''M. tuberculosis'' have developed resistance to more than one TB drug, due to mutations in their genes. In addition, pre-existing first-line TB drugs such as rifampicin and streptomycin have decreased efficiency in clearing intracellular

This glossary of biology terms is a list of definitions of fundamental terms and concepts used in biology, the study of life and of living organisms. It is intended as introductory material for novices; for more specific and technical definitions ...

''M. tuberculosis'' due to their inability to effectively penetrate the macrophage niche.

JNK plays a key role in the control of apoptotic pathways—intrinsic and extrinsic. In addition, it is also found to be a substrate of PPM1A activity, hence the phosphorylation of JNK would cause apoptosis to occur. Since PPM1A levels are elevated during ''M. tuberculosis'' infections, by inhibiting the PPM1A signalling pathways, it could potentially be a therapeutic method to kill ''M. tuberculosis''-infected macrophages by restoring its normal apoptotic function in defence of pathogens. By targeting the PPM1A-JNK signalling axis pathway, then, it could eliminate ''M. tuberculosis''-infected macrophages.

The ability to restore macrophage apoptosis to ''M. tuberculosis''-infected ones could improve the current tuberculosis chemotherapy treatment, as TB drugs can gain better access to the bacteria in the niche. thus decreasing the treatment times for ''M. tuberculosis'' infections.

Symptoms of ''M. tuberculosis'' include coughing that lasts for more than three weeks, hemoptysis

Hemoptysis or haemoptysis is the discharge of blood or blood-stained sputum, mucus through the mouth coming from the bronchi, larynx, vertebrate trachea, trachea, or lungs. It does not necessarily involve coughing. In other words, it is the airw ...

, chest pain when breathing or coughing, weight loss, fatigue, fever, night sweats, chills, and loss of appetite. ''M. tuberculosis'' also has the potential of spreading to other parts of the body. This can cause blood in urine if the kidneys are affected, and back pain if the spine is affected.

Strain variation

Typing of strains is useful in the investigation of tuberculosis outbreaks, because it gives the investigator evidence for or against transmission from person to person. Consider the situation where person A has tuberculosis and believes he acquired it from person B. If the bacteria isolated from each person belong to different types, then transmission from B to A is definitively disproven; however, if the bacteria are the same strain, then this supports (but does not definitively prove) the hypothesis that B infected A. Until the early 2000s, ''M. tuberculosis'' strains were typed by pulsed field gel electrophoresis. This has now been superseded by variable numbers of tandem repeats (VNTR), which is technically easier to perform and allows better discrimination between strains. This method makes use of the presence of repeatedDNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of al ...

sequences within the ''M. tuberculosis'' genome.

Three generations of VNTR typing for ''M. tuberculosis'' are noted. The first scheme, called exact tandem repeat, used only five loci, but the resolution afforded by these five loci was not as good as PFGE. The second scheme, called mycobacterial interspersed repetitive unit, had discrimination as good as PFGE. The third generation (mycobacterial interspersed repetitive unit – 2) added a further nine loci to bring the total to 24. This provides a degree of resolution greater than PFGE and is currently the standard for typing ''M. tuberculosis''. However, with regard to archaeological remains, additional evidence may be required because of possible contamination from related soil bacteria.

Antibiotic resistance in ''M. tuberculosis'' typically occurs due to either the accumulation of mutations in the genes targeted by the antibiotic or a change in titration of the drug. ''M. tuberculosis'' is considered to be multidrug-resistant (MDR TB) if it has developed drug resistance to both rifampicin and isoniazid, which are the most important antibiotics used in treatment. Additionally, extensively drug-resistant ''M. tuberculosis'' (XDR TB) is characterized by resistance to both isoniazid and rifampin, plus any fluoroquinolone and at least one of three injectable second-line drugs (i.e., amikacin

Amikacin is an antibiotic medication used for a number of bacterial infections. This includes joint infections, intra-abdominal infections, meningitis, pneumonia, sepsis, and urinary tract infections. It is also used for the treatment of ...

, kanamycin

Kanamycin A, often referred to simply as kanamycin, is an antibiotic used to treat severe bacterial infections and tuberculosis. It is not a first line treatment. It is used by mouth, injection into a vein, or injection into a muscle. Kanamy ...

, or capreomycin

Capreomycin is an antibiotic which is given in combination with other antibiotics for the treatment of tuberculosis. Specifically it is a second line treatment used for active drug resistant tuberculosis. It is given by injection into a vein or ...

).

Genome

The genome of the H37Rv strain was published in 1998. Its size is 4 million base pairs, with 3,959 genes; 40% of these genes have had their function characterized, with possible function postulated for another 44%. Within the genome are also sixpseudogene

Pseudogenes are nonfunctional segments of DNA that resemble functional genes. Pseudogenes can be formed from both protein-coding genes and non-coding genes. In the case of protein-coding genes, most pseudogenes arise as superfluous copies of fun ...

s.

Fatty acid metabolism. The genome contains 250 genes involved in fatty acid

In chemistry, in particular in biochemistry, a fatty acid is a carboxylic acid with an aliphatic chain, which is either saturated and unsaturated compounds#Organic chemistry, saturated or unsaturated. Most naturally occurring fatty acids have an ...

metabolism, with 39 of these involved in the polyketide

In organic chemistry, polyketides are a class of natural products derived from a Precursor (chemistry), precursor molecule consisting of a Polymer backbone, chain of alternating ketone (, or Carbonyl reduction, its reduced forms) and Methylene gro ...

metabolism generating the waxy coat. Such large numbers of conserved genes show the evolutionary importance of the waxy coat to pathogen survival. Furthermore, experimental studies have since validated the importance of a lipid metabolism for'' M. tuberculosis'', consisting entirely of host-derived lipids such as fats and cholesterol. Bacteria isolated from the lungs of infected mice were shown to preferentially use fatty acids over carbohydrate substrates. ''M. tuberculosis'' can also grow on the lipid cholesterol

Cholesterol is the principal sterol of all higher animals, distributed in body Tissue (biology), tissues, especially the brain and spinal cord, and in Animal fat, animal fats and oils.

Cholesterol is biosynthesis, biosynthesized by all anima ...

as a sole source of carbon, and genes involved in the cholesterol use pathway(s) have been validated as important during various stages of the infection lifecycle of ''M. tuberculosis'', especially during the chronic phase of infection when other nutrients are likely not available.

PE/PPE gene families. About 10% of the coding capacity is taken up by the ''PE''/''PPE'' gene families that encode acidic, glycine-rich proteins. These proteins have a conserved N-terminal motif, deletion of which impairs growth in macrophages and granulomas.

Noncoding RNAs. Nine noncoding sRNAs have been characterised in ''M. tuberculosis'', with a further 56 predicted in a bioinformatics

Bioinformatics () is an interdisciplinary field of science that develops methods and Bioinformatics software, software tools for understanding biological data, especially when the data sets are large and complex. Bioinformatics uses biology, ...

screen.

Antibiotic resistance genes. In 2013, a study on the genome of several sensitive, ultraresistant, and multiresistant ''M. tuberculosis'' strains was made to study antibiotic resistance mechanisms. Results reveal new relationships and drug resistance genes not previously associated and suggest some genes and intergenic regions associated with drug resistance may be involved in the resistance to more than one drug. Noteworthy is the role of the intergenic regions in the development of this resistance, and most of the genes proposed in this study to be responsible for drug resistance have an essential role in the development of ''M. tuberculosis''.

Epigenome. Single-molecule real-time sequencing and subsequent bioinformatic analysis has identified three DNA methyltransferase

In biochemistry, the DNA methyltransferase (DNA MTase, DNMT) family of enzymes catalyze the transfer of a methyl group to DNA. DNA methylation serves a wide variety of biological functions. All the known DNA methyltransferases use S-adenosyl ...

s in ''M. tuberculosis,'' Mycobacterial Adenine Methyltransferases A (MamA), B (MamB), and C (MamC''). ''All three are adenine methyltransferases, and each are functional in some clinical strains of ''M. tuberculosis''and not in others.'' ''Unlike DNA methyltransferases in most bacteria, which invariably methylate the adenine

Adenine (, ) (nucleoside#List of nucleosides and corresponding nucleobases, symbol A or Ade) is a purine nucleotide base that is found in DNA, RNA, and Adenosine triphosphate, ATP. Usually a white crystalline subtance. The shape of adenine is ...

s at their targeted sequence, some strains of ''M. tuberculosis'' carry mutations in MamA that cause partial methylation of targeted adenine bases. This occurs as intracellular stochastic methylation, where a some targeted adenine bases on a given DNA molecule are methylated while others remain unmethylated. MamA mutations causing intercellular mosaic methylation are most common in the globally successful Beijing sublineage of ''M. tuberculosis.'' Due to the influence of methylation on gene expression at some locations in the genome, it has been hypothesized that IMM may give rise to phenotypic diversity, and partially responsible for the global success of Beijing sublineage.

Evolution

The ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' complex (MTBC) evolved in Africa and most probably in theHorn of Africa

The Horn of Africa (HoA), also known as the Somali Peninsula, is a large peninsula and geopolitical region in East Africa.Robert Stock, ''Africa South of the Sahara, Second Edition: A Geographical Interpretation'', (The Guilford Press; 2004), ...

. In addition to ''M. tuberculosis'', the MTBC has a number of members infecting various animal species, including ''M. africanum'', ''M. bovis'' (Dassie's bacillus), ''M. caprae'', ''M. microti'', ''M. mungi, M. orygis'', and ''M. pinnipedii''. This group may also include the '' M. canettii'' clade. These animal strains of MTBC do not strictly deserve species status, as they are all closely related and embedded in the ''M. tuberculosis'' phylogeny, but for historic reasons, they currently hold species status.

The ''M. canettii'' clade – which includes ''M. prototuberculosis'' – is a group of smooth-colony ''Mycobacterium'' species. Unlike the established members of the ''M. tuberculosis'' group, they undergo recombination with other species. The majority of the known strains of this group have been isolated from the Horn of Africa. The ancestor of ''M. tuberculosis'' appears to be ''M. canettii'', first described in 1969.

The established members of the ''M. tuberculosis'' complex are all clonal in their spread. The main human-infecting species have been classified into seven lineages. Translating these lineages into the terminology used for spoligotyping, a very crude genotyping methodology, lineage 1 contains the East Africa

East Africa, also known as Eastern Africa or the East of Africa, is a region at the eastern edge of the Africa, African continent, distinguished by its unique geographical, historical, and cultural landscape. Defined in varying scopes, the regi ...

n-India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

n (EAI), the Manila family of strains and some Manu (Indian) strains; lineage 2 is the Beijing

Beijing, Chinese postal romanization, previously romanized as Peking, is the capital city of China. With more than 22 million residents, it is the world's List of national capitals by population, most populous national capital city as well as ...

group; lineage 3 includes the Central Asia

Central Asia is a region of Asia consisting of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. The countries as a group are also colloquially referred to as the "-stans" as all have names ending with the Persian language, Pers ...

n (CAS) strains; lineage 4 includes the Ghana

Ghana, officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It is situated along the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, and shares borders with Côte d’Ivoire to the west, Burkina Faso to the north, and Togo to t ...

and Haarlem

Haarlem (; predecessor of ''Harlem'' in English language, English) is a List of cities in the Netherlands by province, city and Municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality in the Netherlands. It is the capital of the Provinces of the Nether ...

(H/T), Latin America

Latin America is the cultural region of the Americas where Romance languages are predominantly spoken, primarily Spanish language, Spanish and Portuguese language, Portuguese. Latin America is defined according to cultural identity, not geogr ...

-Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

(LAM) and X strains; types 5 and 6 correspond to ''M. africanum'' and are observed predominantly and at high frequencies in West Africa

West Africa, also known as Western Africa, is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations geoscheme for Africa#Western Africa, United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Gha ...

. A seventh type has been isolated from the Horn of Africa. The other species of this complex belong to a number of spoligotypes and do not normally infect humans.

Lineages 2, 3 and 4 all share a unique deletion event (tbD1) and thus form a monophyletic group. Types 5 and 6 are closely related to the animal strains of MTBC, which do not normally infect humans. Lineage 3 has been divided into two clades: CAS-Kili (found in Tanzania

Tanzania, officially the United Republic of Tanzania, is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It is bordered by Uganda to the northwest; Kenya to the northeast; the Indian Ocean to the east; Mozambique and Malawi to t ...

) and CAS-Delhi (found in India and Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in West Asia. Located in the centre of the Middle East, it covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula and has a land area of about , making it the List of Asian countries ...

).

Lineage 4 is also known as the Euro-American lineage. Subtypes within this type include Latin American Mediterranean, Uganda I, Uganda II, Haarlem, X, and Congo.

A much cited study reported that ''M. tuberculosis'' has co-evolved with human populations, and that the most recent common ancestor

A most recent common ancestor (MRCA), also known as a last common ancestor (LCA), is the most recent individual from which all organisms of a set are inferred to have descended. The most recent common ancestor of a higher taxon is generally assu ...

of the ''M. tuberculosis'' complex evolved between 40,000 and 70,000 years ago. However, a later study that included genome sequences from ''M. tuberculosis'' complex members extracted from three 1,000-year-old Peruvian mummies, came to quite different conclusions. If the most recent common ancestor

A most recent common ancestor (MRCA), also known as a last common ancestor (LCA), is the most recent individual from which all organisms of a set are inferred to have descended. The most recent common ancestor of a higher taxon is generally assu ...

of the ''M. tuberculosis'' complex were 40,000 to 70,000 years old, this would necessitate an evolutionary rate much lower than any estimates produced by genomic analyses of heterochronous samples, suggesting a far more recent common ancestor of the ''M. tuberculosis'' complex as little as 6000 years ago.

An analysis of over 3000 strains of ''M. bovis'' from 35 countries suggested an Africa origin for this species.Loiseau C, Menardo F, Aseffa A, Hailu E, Gumi B, Ameni G, Berg S, Rigouts L, Robbe-Austerman S, Zinsstag J, Gagneux S, Brites D (2020) An African origin for ''Mycobacterium bovis''. Evol Med Public Health. 2020 Jan 31;2020(1):49–59

Co-evolution with modern humans

There are currently two narratives existing in parallel regarding the age of MTBC and how it has spread and co-evolved with humans through time. One study compared the ''M. tuberculosis'' phylogeny to a human mitochondrial genome phylogeny and interpreted these as being highly similar. Based on this, the study suggested that ''M. tuberculosis'', like humans, evolved in Africa and subsequently spread with anatomically modern humans out of Africa across the world. By calibrating the mutation rate of M. tuberculosis to match this narrative, the study suggested that MTBC evolved 40,000–70,000 years ago. Applying this time scale, the study found that the ''M. tuberculosis''effective population size

The effective population size (''N'e'') is the size of an idealised population that would experience the same rate of genetic drift as the real population. Idealised populations are those following simple one- locus models that comply with ass ...

expanded during the Neolithic Demographic Transition

The Neolithic demographic transition was a period of rapid population growth following the adoption of agriculture by prehistoric societies (the Neolithic Revolution). It was a demographic transition caused by an abrupt increase in birth rates due ...

(around 10,000 years ago) and suggested that ''M. tuberculosis'' was able to adapt to changing human populations and that the historical success of this pathogen was driven at least in part by dramatic increases in human host population density. It has also been demonstrated that after emigrating from one continent to another, a human host's region of origin is predictive of which TB lineage they carry, which could reflect either a stable association between host populations and specific ''M. tuberculosis'' lineages and/or social interactions that are shaped by shared cultural and geographic histories.

Regarding the congruence between human and ''M. tuberculosis'' phylogenies, a study relying on ''M. tuberculosis'' and human Y chromosome

The Y chromosome is one of two sex chromosomes in therian mammals and other organisms. Along with the X chromosome, it is part of the XY sex-determination system, in which the Y is the sex-determining chromosome because the presence of the ...

DNA sequences to formally assess the correlation between them, concluded that they are not congruent. Also, a more recent study which included genome sequences from ''M. tuberculosis'' complex members extracted from three 1,000-year-old Peruvian mummies, estimated that the most recent common ancestor

A most recent common ancestor (MRCA), also known as a last common ancestor (LCA), is the most recent individual from which all organisms of a set are inferred to have descended. The most recent common ancestor of a higher taxon is generally assu ...

of the ''M. tuberculosis'' complex lived only 4,000 – 6,000 years ago. The ''M. tuberculosis'' evolutionary rate estimated by the Bos et al. study is also supported by a study on Lineage 4 relying on genomic aDNA sequences from Hungarian mummies more than 200 years old. In total, the evidence thus favors this more recent estimate of the age of the MTBC most recent common ancestor, and thus that the global evolution and dispersal of ''M. tuberculosis'' has occurred over the last 4,000–6,000 years.

Among the seven recognized lineages of ''M. tuberculosis'', only two are truly global in their distribution: Lineages 2 and 4. Among these, Lineage 4 is the most well dispersed, and almost totally dominates in the Americas. Lineage 4 was shown to have evolved in or in the vicinity of Europe, and to have spread globally with Europeans starting around the 13th century. This study also found that Lineage 4 tuberculosis spread to the Americas shortly after the European discovery of the continent in 1492, and suggests that this represented the first introduction of human TB on the continent (although animal strains have been found in human remains predating Columbus. Similarly, Lineage 4 was found to have spread from Europe to Africa during the Age of Discovery

The Age of Discovery (), also known as the Age of Exploration, was part of the early modern period and overlapped with the Age of Sail. It was a period from approximately the 15th to the 17th century, during which Seamanship, seafarers fro ...

, starting in the early 15th century.

It has been suggested that ancestral mycobacteria may have infected early hominids in East Africa as early as three million years ago.

DNA fragments from ''M. tuberculosis'' and tuberculosis disease indications were present in human bodies dating from 7000 BC found at Atlit-Yam in the Levant

The Levant ( ) is the subregion that borders the Eastern Mediterranean, Eastern Mediterranean sea to the west, and forms the core of West Asia and the political term, Middle East, ''Middle East''. In its narrowest sense, which is in use toda ...

.

Antibiotic resistance (ABR)

''M. tuberculosis'' is a clonal organism and does not exchange DNA viahorizontal gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or lateral gene transfer (LGT) is the movement of genetic material between organisms other than by the ("vertical") transmission of DNA from parent to offspring (reproduction). HGT is an important factor in the e ...

. Despite an additionally slow evolution rate, the emergence and spread of antibiotic resistance in ''M. tuberculosis'' poses an increasing threat to global public health. In 2019, the WHO reported the estimated incidence of antibiotic resistant TB to be 3.4% in new cases, and 18% in previously treated cases. Geographical discrepancies exist in the incidence rates of drug-resistant TB. Countries facing the highest rates of antibiotic resistant TB include China, India, Russia, and South Africa. Recent trends reveal an increase in drug-resistant cases in a number of regions, with Papua New Guinea, Singapore, and Australia undergoing significant increases.

Multidrug-resistant Tuberculosis (MDR-TB) is characterised by resistance to at least the two front-line drugs isoniazid

Isoniazid, also known as isonicotinic acid hydrazide (INH), is an antibiotic used for the treatment of tuberculosis. For active tuberculosis, it is often used together with rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and either streptomycin or ethambutol. F ...

and rifampin

Rifampicin, also known as rifampin, is an ansamycin antibiotic used to treat several types of bacterial infections, including tuberculosis (TB), ''Mycobacterium avium'' complex, leprosy, and Legionnaires' disease. It is almost always used tog ...

. MDR is associated with a relatively poor treatment success rate of 52%. Isoniazid and rifampin resistance are tightly linked, with 78% of the reported rifampin-resistant TB cases in 2019 being resistant to isoniazid as well. Rifampin-resistance is primarily due to resistance-conferring mutations in the rifampin-resistance determining region (RRDR) within the rpoB gene. The most frequently observed mutations of the codons in RRDR are 531, 526 and 516. However, alternative more elusive resistance-conferring mutations have been detected. Isoniazid function occurs through the inhibition of mycolic acid synthesis through the NADH-dependent enoyl-acyl carrier protein (ACP)-reductase. This is encoded by the ''inhA'' gene. As a result, isoniazid resistance is primarily due to mutations within inhA and the katG gene or its promoter region - a catalase-peroxidase which is required to activate isoniazid. As MDR in ''M. tuberculosis'' becomes increasingly common, the emergence of pre-extensively drug resistant (pre-XDR) and extensively drug resistant (XDR-) TB threatens to exacerbate the public health crisis. XDR-TB is characterised by resistance to both rifampin and Isoniazid, as well second-line fluoroquinolones and at least one additional front-line drug. Thus, the development of alternative therapeutic measures is of utmost priority.

An intrinsic contributor to the antibiotic resistant nature of ''M. tuberculosis'' is its unique cell wall. Saturated with long-chain fatty acid

In chemistry, in particular in biochemistry, a fatty acid is a carboxylic acid with an aliphatic chain, which is either saturated and unsaturated compounds#Organic chemistry, saturated or unsaturated. Most naturally occurring fatty acids have an ...

s or mycolic acids, the mycobacterial cell presents a robust, relatively insoluble barrier. This has led to its synthesis being the target of many antibiotics - such as Isoniazid. However, resistance has emerged to the majority of them. A novel, promising therapeutic target is mycobacterial membrane protein large 3 (MmpL3). The mycobacterial membrane protein large (MmpL) proteins are transmembrane proteins which play a key role in the synthesis of the cell wall and the transport of the associated lipids. Of these, MmpL3 is essential; knock-out of which has been shown to be bactericidal. Due to its essential nature, MmpL3 inhibitors show promise as alternative therapeutic measures in the age of antibiotic resistance. Inhibition of MmpL3 function showed an inability to transport trehalose monomycolate - an essential cell wall lipid - across the plasma membrane. The recently reported structure of MmpL3 revealed resistance-conferring mutations to associate primarily with the transmembrane domain. Although resistance to pre-clinical MmpL3 inhibitors has been detected, analysis of the widespread mutational landscape revealed a low level of environmental resistance. This suggests that MmpL3 inhibitors currently undergoing clinical trials would face little resistance if made available. Additionally, the ability of many MmpL3 inhibitors to work synergistically with other antitubercular drugs presents a ray of hope in combatting the TB crisis. Genome modeling of ''M. tuberculosis'' has also highlighted potential synthetic lethal interactions that could inform new therapeutic strategies. Specifically, knock-out of the gene Rv0489 has been shown to render gene Rv2156c essential. Given that Rv2156c is involved in peptidoglycan

Peptidoglycan or murein is a unique large macromolecule, a polysaccharide, consisting of sugars and amino acids that forms a mesh-like layer (sacculus) that surrounds the bacterial cytoplasmic membrane. The sugar component consists of alternating ...

synthesis, this synthetic lethality could be exploited to sensitize ''M. tuberculosis'' to β-lactam antibiotics, which typically target cell wall synthesis. This opens up the possibility of repurposing existing β-lactam drugs as part of combination therapies to more effectively treat resistant tuberculosis strains.

Another cause for ''M. tuberculosis'' drug resistance are efflux pumps that can be found in many bacteria. Efflux pumps are used by the bacteria for some endogenous functions, for example lipid transport from the inner- to the outer membrane, but also as a way of reducing the drug concentration inside the cell. The EfpA efflux pump that can be found in ''M. tuberculosis'' is a part of the major facilitator superfamily

The major facilitator superfamily (MFS) is a Protein superfamily, superfamily of membrane transport proteins that facilitate movement of small solutes across cell membranes in response to chemiosmosis, chemiosmotic gradients.

Function

The major ...

(MFS). In ''M. tuberculosis'' the EfpA transports endogenous lipids and possibly drugs via a staircase-flips model from the inner to the outer membrane. This mechanism is a possible drug target, as inhibition of it leads to the death of the bacteria, seemingly mostly by blocking its endogenous functions.

Host genetics

The nature of the host-pathogen interaction between humans and ''M. tuberculosis'' is considered to have a genetic component. A group of rare disorders called Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial diseases was observed in a subset of individuals with a genetic defect that results in increased susceptibility to mycobacterial infection. Early case and twin studies have indicated that genetic components are important in host susceptibility to ''M. tuberculosis''. Recent genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified three genetic risk loci, including at positions 11p13 and 18q11. As is common in GWAS, the variants discovered have moderate effect sizes.DNA repair

As an intracellular pathogen, ''M. tuberculosis'' is exposed to a variety of DNA-damaging assaults, primarily from host-generated antimicrobial toxic radicals. Exposure to reactive oxygen species and/or reactive nitrogen species causes different types of DNA damage including oxidation, depurination, methylation, and deamination that can give rise to single- and double-strand breaks (DSBs). DnaE2 polymerase is upregulated in ''M. tuberculosis'' by several DNA-damaging agents, as well as during infection of mice. Loss of this DNA polymerase reduces the virulence of ''M. tuberculosis'' in mice. DnaE2 is an error-prone DNA repair polymerase that appears to contribute to ''M. tuberculosis'' survival during infection. The two major pathways employed in repair of DSBs arehomologous recombination

Homologous recombination is a type of genetic recombination in which genetic information is exchanged between two similar or identical molecules of double-stranded or single-stranded nucleic acids (usually DNA as in Cell (biology), cellular organi ...

al repair (HR) and nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ). Macrophage-internalized ''M. tuberculosis'' is able to persist if either of these pathways is defective, but is attenuated when both pathways are defective. This indicates that intracellular exposure of ''M. tuberculosis'' to reactive oxygen and/or reactive nitrogen species results in the formation of DSBs that are repaired by HR or NHEJ. However deficiency of DSB repair does not appear to impair ''M. tuberculosis'' virulence in animal models.

History

''M. tuberculosis'', then known as the "tubercle

In anatomy, a tubercle (literally 'small tuber', Latin for 'lump') is any round nodule, small eminence, or warty outgrowth found on external or internal organs of a plant or an animal.

In plants

A tubercle is generally a wart-like projectio ...

bacillus

''Bacillus'', from Latin "bacillus", meaning "little staff, wand", is a genus of Gram-positive, rod-shaped bacteria, a member of the phylum ''Bacillota'', with 266 named species. The term is also used to describe the shape (rod) of other so-sh ...

", was first described on 24 March 1882 by Robert Koch

Heinrich Hermann Robert Koch ( ; ; 11 December 1843 – 27 May 1910) was a German physician and microbiologist. As the discoverer of the specific causative agents of deadly infectious diseases including tuberculosis, cholera and anthrax, he i ...

, who subsequently received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine () is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or medicine. The Nobel Prize is not a single prize, but five separate prizes that, acco ...

for this discovery in 1905; the bacterium is also known as "Koch's bacillus".

''M. tuberculosis'' has existed throughout history, but the name has changed frequently over time. In 1720, though, the history of tuberculosis started to take shape into what is known of it today; as the physician Benjamin Marten described in his ''A Theory of Consumption'', tuberculosis may be caused by small living creatures transmitted through the air to other patients.

More than 100 million people around the world have died from being infected with mycobacterium tuberculosis due to unavailability of the vaccine in some parts of the world.

Vaccine

TheBCG vaccine

The Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccine is a vaccine primarily used against tuberculosis (TB). It is named after its inventors Albert Calmette and Camille Guérin. In countries where tuberculosis or leprosy is common, one dose is recom ...

(bacille Calmette-Guerin), which was derived from ''M. bovis,'' while effective against childhood and severe forms of tuberculosis, has limited success in preventing the most common form of the disease today, adult pulmonary tuberculosis. Because of this, it is primarily used in high tuberculosis incidence regions, and is not a recommended vaccine in the United States due to the low risk of infection. To receive this vaccine in the United States, an individual is required to go through a consultation process with an expert in ''M. tuberculosis'' and is only given to those who meet the specific criteria.

Administration of the BCG vaccine has been shown to induced so called " trained immunity", which refers to the enhanced response of the innate immune system. Unlike adaptive immunity

The adaptive immune system (AIS), also known as the acquired immune system, or specific immune system is a subsystem of the immune system that is composed of specialized cells, organs, and processes that eliminate pathogens specifically. The ac ...

, trained immunity involves long-lasting changes in innate immune cells like monocyte

Monocytes are a type of leukocyte or white blood cell. They are the largest type of leukocyte in blood and can differentiate into macrophages and monocyte-derived dendritic cells. As a part of the vertebrate innate immune system monocytes also ...

s and macrophages, which become more responsive to infections. These changes occur through epigenetic reprogramming

In biology, reprogramming refers to erasure and remodeling of Epigenetics, epigenetic marks, such as DNA methylation, during mammalian development or in cell culture. Such control is also often associated with alternative covalent modifications o ...

, such as histone modification

In biology, histones are highly basic proteins abundant in lysine and arginine residues that are found in eukaryotic cell nuclei and in most Archaeal phyla. They act as spools around which DNA winds to create structural units called nucleosomes. ...

s, leading to increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines.

Research indicates there may be a correlation between BCG vaccination and better immune response to COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a contagious disease caused by the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. In January 2020, the disease spread worldwide, resulting in the COVID-19 pandemic.

The symptoms of COVID‑19 can vary but often include fever ...

.

The DNA vaccine can be used alone or in combination with BCG. DNA vaccines have enough potential to be used with TB treatment and reduce the treatment time in future.

See also

* Philip D'Arcy HartReferences

External links

TB database: an integrated platform for Tuberculosis research

*

Database on Mycobacterium tuberculosis genetics

{{Authority control Acid-fast bacilli

tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

Tuberculosis

Pathogenic bacteria

Bacteria described in 1882