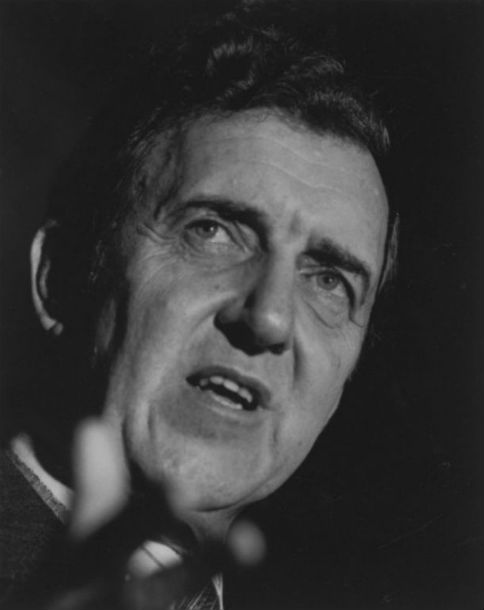

Edmund Sixtus Muskie (March 28, 1914March 26, 1996) was an American statesman and political leader who served as the 58th

United States Secretary of State

The United States secretary of state (SecState) is a member of the executive branch of the federal government of the United States and the head of the U.S. Department of State.

The secretary of state serves as the principal advisor to the ...

under President

Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (October 1, 1924December 29, 2024) was an American politician and humanitarian who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party ...

from 1980 to 1981, a

United States Senator from Maine from 1959 to 1980, the 64th

governor of Maine

The governor of Maine is the head of government of the U.S. state of Maine. Before Maine was admitted to the Union in 1820, Maine was part of Massachusetts and the governor of Massachusetts was chief executive.

The current governor of Maine is J ...

from 1955 to 1959, and a member of the

Maine House of Representatives

The Maine House of Representatives is the lower house of the Maine Legislature. The House consists of 151 voting members and three nonvoting members. The voting members represent an equal number of districts across the state and are elected via ...

from 1946 to 1951. He was the

Democratic Party's nominee for vice president in the

1968 presidential election.

Born in

Rumford Rumford may refer to:

People

* William Byron Rumford (1908–1986), California politician

* Sir Benjamin Thompson, Count Rumford (1753–1814), American-British-German inventor, scientist, soldier, and official

* Kennerley Rumford (1870–1957), E ...

, Maine, he worked as a lawyer for two years before serving in the

United States Naval Reserve

The United States Navy Reserve (USNR), known as the United States Naval Reserve from 1915 to 2004, is the Reserve Component (RC) of the United States Navy. Members of the Navy Reserve, called reservists, are categorized as being in either the S ...

from 1942 to 1945 during

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. Upon his return, Muskie served in the

Maine State Legislature

The Maine State Legislature is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Maine. It is a bicameral body composed of the lower house Maine House of Representatives and the upper house Maine Senate. The legislature convenes at the State House in ...

from 1946 to 1951, and unsuccessfully ran for mayor of

Waterville. Muskie was elected the

64th governor of Maine in 1954 under a reform platform as the first

Democratic governor since

Louis J. Brann

Louis Jefferson Brann (July 6, 1876 – February 3, 1948) was an American lawyer and political figure. He was the 56th governor of Maine.

Early life

Brann was born in Madison, Maine to Charles M. Brann and Nancy Lancaster Brann. He attended sc ...

left office in 1937, and only the fifth since 1857. Muskie pressed for economic expansionism and instated environmental provisions. Muskie's actions severed a nearly

100-year Republican stronghold and led to the political insurgency of the Maine Democrats.

Muskie's legislative work during

his career as a senator coincided with an expansion of

modern liberalism in the United States

Modern liberalism, often referred to simply as liberalism, is the dominant version of liberalism in the United States. It combines ideas of civil liberty and Social equality, equality with support for social justice and a mixed economy. Modern l ...

. He promoted the

1960s environmental movement which led to the passage of the

Clean Air Act of 1970

The Clean Air Act (CAA) is the United States' primary federal air quality law, intended to reduce and control air pollution nationwide. Initially enacted in 1963 and amended many times since, it is one of the United States' first and most in ...

and the

Clean Water Act of 1972

The Clean Water Act (CWA) is the primary federal law in the United States governing water pollution. Its objective is to restore and maintain the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the nation's waters; recognizing the primary respo ...

. Muskie supported the

Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 () is a landmark civil rights and United States labor law, labor law in the United States that outlaws discrimination based on Race (human categorization), race, Person of color, color, religion, sex, and nationa ...

, the creation of

Martin Luther King Jr. Day

Martin Luther King Jr. Day (officially Birthday of Martin Luther King Jr., and often referred to shorthand as MLK Day) is a federal holiday in the United States observed on the third Monday of January each year. King was the chief spokespers ...

, and opposed

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 until Resignation of Richard Nixon, his resignation in 1974. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

's "

Imperial presidency" by advancing

New Federalism

New Federalism is a political philosophy of devolution, or the transfer of certain powers from the United States federal government back to the states. The primary objective of New Federalism, unlike that of the eighteenth-century political philo ...

. Muskie ran with Vice President

Hubert Humphrey

Hubert Horatio Humphrey Jr. (May 27, 1911 – January 13, 1978) was an American politician who served from 1965 to 1969 as the 38th vice president of the United States. He twice served in the United States Senate, representing Minnesota from 19 ...

against Nixon in the 1968 presidential election, losing the popular vote by 0.7 percentage point—one of the

narrowest margins in U.S. history. He would go on to run in the

1972 presidential election, where he secured 1.84 million votes in

the primaries, coming in fourth out of 15 contesters. The release of the forged "

Canuck letter

The Canuck letter was a letter to the editor of the '' Manchester Union Leader'', published February 24, 1972, two weeks before the New Hampshire primary of the 1972 United States presidential election. It implied that Senator Edmund Muskie, a ca ...

" derailed his campaign and sullied his public image with

Americans of French-Canadian descent.

After the election, Muskie returned to the Senate, where he gave the 1976

State of the Union Response. Muskie served as first chairman of the new

Senate Budget Committee

The United States Senate Committee on the Budget was established by the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974. It is responsible for drafting Congress's annual budget plan and monitoring action on the budget for the Federal ...

from 1975 to 1980, where he established the

United States budget process

The United States budget process is the framework used by Congress and the President of the United States to formulate and create the United States federal budget. The process was established by the Budget and Accounting Act of 1921, the Congre ...

. Upon his resignation from the Senate, he became the 58th U.S. Secretary of State under President Carter. Muskie's tenure as Secretary of State was one of the shortest in modern history. His department negotiated the

release of 52 Americans, thus concluding the

Iran hostage crisis

The Iran hostage crisis () began on November 4, 1979, when 66 Americans, including diplomats and other civilian personnel, were taken hostage at the Embassy of the United States in Tehran, with 52 of them being held until January 20, 1981. Th ...

. He was awarded the

Presidential Medal of Freedom

The Presidential Medal of Freedom is the highest civilian award of the United States, alongside the Congressional Gold Medal. It is an award bestowed by decision of the president of the United States to "any person recommended to the President ...

by Carter in 1981 and has been honored with

a public holiday in Maine since 1987.

Early life and education

Edmund Sixtus Muskie was born on March 28, 1914, to Polish parents in

Rumford Rumford may refer to:

People

* William Byron Rumford (1908–1986), California politician

* Sir Benjamin Thompson, Count Rumford (1753–1814), American-British-German inventor, scientist, soldier, and official

* Kennerley Rumford (1870–1957), E ...

, Maine.

He was born after his parents' first child, Irene (born 1912), and before his brother Eugene (born 1918) and three sisters, Lucy (born 1916), Elizabeth (born 1923), and Frances (born 1921).

[Witherell (2014), p. 4] His father, Stephen Marciszewski, was born and raised in

Jasionówka,

Russian Poland

Congress Poland or Congress Kingdom of Poland, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland, was a polity created in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna as a semi-autonomous Polish people, Polish State (polity), state, a successor to Napoleon's Duchy of ...

[ampoleagle.com/ann-mikoll-a-trailblazer-p10493-226.htm "Stephen Marciszewski, came to Buffalo in the early 1900s after leaving his birthplace in Jasionewka, Poland. That part of Poland was occupied by Russia, and Stephen's father sent him away so that he wouldn't be conscripted into the Russian Army."] and worked as an estate manager for minor

Russian nobility

The Russian nobility or ''dvoryanstvo'' () arose in the Middle Ages. In 1914, it consisted of approximately 1,900,000 members, out of a total population of 138,200,000. Up until the February Revolution of 1917, the Russian noble estates staffed ...

. He immigrated to America in 1903 and changed his name to Muskie from "Marciszewski" in 1914.

[David (1970), p. 10] He worked as a

master tailor

A tailor is a person who makes or alters clothing, particularly in men's clothing. The Oxford English Dictionary dates the term to the thirteenth century.

History

Although clothing construction goes back to prehistory, there is evidence of ...

and Muskie's mother, Josephine (

née

The birth name is the name of the person given upon their birth. The term may be applied to the surname, the given name or to the entire name. Where births are required to be officially registered, the entire name entered onto a births registe ...

Czarnecka) worked as a

housewife

A housewife (also known as a homemaker or a stay-at-home mother/mom/mum) is a woman whose role is running or managing her family's home—housekeeping, which may include Parenting, caring for her children; cleaning and maintaining the home; Sew ...

. She was born to a

Polish-American

Polish Americans () are Americans who either have total or partial Polish ancestry, or are citizens of the Republic of Poland. There are an estimated 8.81 million self-identified Polish Americans, representing about 2.67% of the U.S. population, ...

family in

Buffalo

Buffalo most commonly refers to:

* True buffalo or Bubalina, a subtribe of wild cattle, including most "Old World" buffalo, such as water buffalo

* Bison, a genus of wild cattle, including the American buffalo

* Buffalo, New York, a city in the n ...

, New York. Muskie's parents married in 1911, and Josephine moved to Rumford soon after.

Muskie's first language was

Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Polish people, people from Poland or of Polish descent

* Polish chicken

* Polish brothers (Mark Polish and Michael Polish, born 1970), American twin ...

; he spoke it as his only language until age 4. He began learning English soon after and eventually lost fluency in his mother language. In his youth he was an avid fisherman, hunter, and swimmer.

He felt as though his given name was "odd" so he went by Ed throughout his life. Muskie was shy and anxious in his early life but maintained a sizable number of friends.

Muskie attended Stephens High School, where he played baseball, participated in the performing arts, and was elected student body president in his senior year. He would go on to graduate in 1932 at the top of his class as

valedictorian

Valedictorian is an academic title for the class rank, highest-performing student of a graduation, graduating class of an academic institution in the United States.

The valedictorian is generally determined by an academic institution's grade poin ...

.

A 1931 edition of the school's newspaper noted him with the following: "when you see a head and shoulders towering over you in the halls of Stephen's, you should know that your eyes are feasting on the future President of the United States."

Influenced by the political excitement of

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

's election to the

White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. Located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest (Washington, D.C.), NW in Washington, D.C., it has served as the residence of every U.S. president ...

, he attended

Bates College

Bates College () is a Private college, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Lewiston, Maine. Anchored by the Historic Quad, the campus of Bates totals with a small urban campus which includes 33 Victorian ...

in

Lewiston, Maine.

While at college, Muskie was a successful member of the

debating

Debate is a process that involves formal discourse, discussion, and oral addresses on a particular topic or collection of topics, often with a moderator and an audience. In a debate, arguments are put forward for opposing viewpoints. Historica ...

team, participated in several sports, and was elected to

student government

A students' union or student union, is a student organization present in many colleges, universities, and high schools. In higher education, the students' union is often accorded its own building on the campus, dedicated to social, organizatio ...

.

Although he received a small scholarship and

New Deal

The New Deal was a series of wide-reaching economic, social, and political reforms enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1938, in response to the Great Depression in the United States, Great Depressi ...

subsidies, he had to work during the summers as a dishwasher and

bellhop

A bellhop (North America), or hotel porter (international), is a hotel employee who helps patrons with their luggage while checking in or out. Bellhops often wear a uniform, like certain other page boys or doormen. This occupation is also know ...

at a hotel in

Kennebunk

Kennebunk is a town in York County, Maine, United States. The population was 11,536 at the 2020 census. Kennebunk is home to several beaches, the Rachel Carson National Wildlife Refuge, the 1799 Kennebunk Inn, many historic shipbuilders' ho ...

to finance his time at Bates. He would record in his diaries occasional feelings of insecurity among his wealthier Bates peers; Muskie was fearful of being kicked out of the college as a consequence of his

socioeconomic status

Socioeconomic status (SES) is a measurement used by economics, economists and sociology, sociologsts. The measurement combines a person's work experience and their or their family's access to economic resources and social position in relation t ...

. His situation would gradually improve and he went on to graduate in 1936 as class president and a member of

Phi Beta Kappa

The Phi Beta Kappa Society () is the oldest academic honor society in the United States. It was founded in 1776 at the College of William & Mary in Virginia. Phi Beta Kappa aims to promote and advocate excellence in the liberal arts and sciences, ...

.

Initially intending to major in mathematics he switched to a double major in history and government.

Upon his graduation, he was given a partial merit-based scholarship to

Cornell Law School

Cornell Law School is the law school of Cornell University, a private university, private, Ivy League university in Ithaca, New York.

One of the five Ivy League law schools, Cornell Law School offers four degree programs (Juris Doctor, JD, Maste ...

. After his second semester there, his scholarship ran out. As he was preparing to drop out, he heard of an "eccentric millionaire" named William Bingham II who had a habit of randomly and sporadically paying the university costs, mortgages, car loans, and other expenses of those who wrote to him. After Muskie wrote to him about his immigrant origins he secured $900 from the man allowing him to finance his final years at Cornell. While in law school he was elected to

Phi Alpha Delta

Phi Alpha Delta Law Fraternity, International ( or P.A.D.) is a North American professional fraternity composed of pre-law and law students, legal educators, attorneys, judges, and government officials. It is one of the largest professional law ...

and went on to graduate ''

cum laude

Latin honors are a system of Latin phrases used in some colleges and universities to indicate the level of distinction with which an academic degree has been earned. The system is primarily used in the United States. It is also used in some Sout ...

'', in 1939.

Upon graduating from Cornell, Muskie was admitted to the

Massachusetts Bar

The Massachusetts Bar Association (MBA) is a voluntary, non-profit bar association in Massachusetts with a headquarters on West Street in Boston, Boston's Downtown Crossing. The MBA also has a Western Massachusetts office.

The purpose of the MB ...

in 1939.

He then worked as a high school substitute teacher while he was studying for the Maine Bar examination; he passed in 1940. Muskie moved to

Waterville and purchased a small law practice—renamed "Muskie & Glover"—for $2,000 in March 1940. He helped write Waterville's first zoning ordinance and was elected secretary of the Zoning Board of Appeals.

Marriage and children

Jane Frances Gray was born February 12, 1927, in Waterville to Myrtie and Millage Guy Gray. Growing up, she was voted "prettiest in school" in high school and at age 15, started her first job, in a dress shop.

At age 18, Gray was hired to be a bookkeeper and saleswoman in an exclusive

haute couture boutique in Waterville. While there, a mutual friend tried to introduce her to Muskie while he was working in the city as a lawyer. She had Gray model the dresses in the shop window while he was walking to work. Muskie came into the shop one day and invited her to a gala event. At the time, she was 19 and he was 32;

their difference in age stirred controversy in the town. However, after eighteen months of courting Gray and her family, she agreed to marry him in a private ceremony in 1948. Gray and Muskie had five children: Stephen (born 1949), Ellen (born 1950), Melinda (born 1956), Martha (born 1958, d. 2006), and Edmund Jr. (born 1961).

The Muskies lived in a yellow cottage at

Kennebunk Beach while they lived in Maine.

U.S. Navy Reserve, 1942–1945

In June 1940, President Roosevelt created the

V-12 Navy College Training Program

The V-12 Navy College Training Program was designed to supplement the force of commissioned officers in the United States Navy during World War II. Between July 1, 1943, and June 30, 1946, more than 125,000 participants were enrolled in 131 colleg ...

to prepare men under the age of 28 for the eventual outbreak of

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. Muskie formally registered for the

draft

Draft, the draft, or draught may refer to:

Watercraft dimensions

* Draft (hull), the distance from waterline to keel of a vessel

* Draft (sail), degree of curvature in a sail

* Air draft, distance from waterline to the highest point on a v ...

in October 1940 and was formally called to

deck officer

The deck department is an organisational team on board naval and merchant ships. Seafarers in the deck department work a variety of jobs on a ship or vessel, but primarily they will carry out the navigation of a vessel from the bridge. Howeve ...

training on March 26, 1942.

[Witherell (2014), p. 64] At 28, he was assigned to work as a

diesel engineer in the

Naval Reserve Midshipmen's School.

On September 11, 1942, Muskie was called to

Annapolis

Annapolis ( ) is the capital of the U.S. state of Maryland. It is the county seat of Anne Arundel County and its only incorporated city. Situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east o ...

, Maryland, to attend the

United States Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (USNA, Navy, or Annapolis) is a United States Service academies, federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as United States Secre ...

. He left his law practice running so "his name would continue to circulate in Waterville" while he was gone. He trained as an

apprentice seaman

Seaman apprentice is the second lowest enlisted rate in the U.S. Navy, U.S. Coast Guard, and the U.S. Naval Sea Cadet Corps just above seaman recruit and below seaman; this rank was formerly known as seaman second class.

The current rank o ...

for six weeks before being assigned the rank of

midshipman

A midshipman is an officer of the lowest Military rank#Subordinate/student officer, rank in the Royal Navy, United States Navy, and many Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth navies. Commonwealth countries which use the rank include Royal Cana ...

.

In January 1943, Muskie attended diesel engineering school for sixteen weeks before being assigned to

First Naval District,

Boston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

in May. Muskie worked on the for a month. In June, he was assigned to the at

Fort Schuyler

Fort Schuyler is a preserved 19th century fortification in the New York City borough (New York City), borough of the Bronx. It houses a museum, the Stephen B. Luce Library, and the Marine Transportation Department and Administrative offices ...

in New York, where he worked as an

indoctrinator. In November 1943, Muskie was promoted to

Deck Officer

The deck department is an organisational team on board naval and merchant ships. Seafarers in the deck department work a variety of jobs on a ship or vessel, but primarily they will carry out the navigation of a vessel from the bridge. Howeve ...

. He trained for two weeks in Miami, Florida, at the

Submarine Chaser Training Center. After that, Muskie was relocated to

Columbus

Columbus is a Latinized version of the Italian surname "''Colombo''". It most commonly refers to:

* Christopher Columbus (1451–1506), the Italian explorer

* Columbus, Ohio, the capital city of the U.S. state of Ohio

* Columbus, Georgia, a city i ...

, Ohio, to study

reconnaissance

In military operations, military reconnaissance () or scouting is the exploration of an area by military forces to obtain information about enemy forces, the terrain, and civil activities in the area of operations. In military jargon, reconnai ...

in February 1944.

[Witherell (2014), p. 70] In March, he was promoted to

Lieutenant (junior grade)

Lieutenant junior grade is a junior commissioned officer rank used in a number of navies.

United States

Lieutenant (junior grade), commonly abbreviated as LTJG or, historically, Lt. (j.g.) (as well as variants of both abbreviations), i ...

.

Muskie was stationed at California's

Mare Island

Mare Island (Spanish language, Spanish: ''Isla de la Yegua'') is a peninsula in the United States in the city of Vallejo, California, about northeast of San Francisco. The Napa River forms its eastern side as it enters the Carquinez Strait junc ...

in April temporarily before formally engaging in

active duty

Active duty, in contrast to reserve duty, is a full-time occupation as part of a military force.

Indian

The Indian Armed Forces are considered to be one of the largest active service forces in the world, with almost 1.42 million Active Standin ...

warfare.

Muskie began his active duty tour aboard the

destroyer escort

Destroyer escort (DE) was the United States Navy mid-20th-century classification for a warship designed with the endurance necessary to escort mid-ocean convoys of merchant marine ships.

Development of the destroyer escort was promoted by th ...

. His vessel was in charge of protecting

U.S. convoys traveling from the

Marshal

Marshal is a term used in several official titles in various branches of society. As marshals became trusted members of the courts of Middle Ages, Medieval Europe, the title grew in reputation. During the last few centuries, it has been used fo ...

and

Gilbert Islands

The Gilbert Islands (;Reilly Ridgell. ''Pacific Nations and Territories: The Islands of Micronesia, Melanesia, and Polynesia.'' 3rd. Ed. Honolulu: Bess Press, 1995. p. 95. formerly Kingsmill or King's-Mill IslandsVery often, this name applied o ...

from

Japanese submarines. The ''Brackett'' escorted ships to and from the islands for the majority of summer 1944. In January 1945, the ship engaged and eventually sank a Japanese cargo ship headed for

Taroa Island

Taroa is an island in the east of Maloelap Atoll in the Marshall Islands. During World War II, it was the site of a major Japanese airfield (Taroa Airfield). The airfield was destroyed near the close of World War II, and parts of the base and its ...

. After a few more months of escorting ships to and from the two islands, the ship was

decommissioned. He was

discharged

Discharge may refer to:

* The act of firing a gun

* Termination of employment, the end of an employee's duration with an employer

* Military discharge, the release of a member of the armed forces from service

Flow

* Discharge (hydrology), the a ...

from the Navy on December 18, 1945.

Maine House of Representatives

Muskie returned to Maine in January 1946 and began rebuilding his law practice. Convinced by others to run for political office as a way of expanding his law practice, he formally entered politics. Muskie ran against Republican

William A. Jones in an election for the

Maine House of Representatives

The Maine House of Representatives is the lower house of the Maine Legislature. The House consists of 151 voting members and three nonvoting members. The voting members represent an equal number of districts across the state and are elected via ...

for the 110th District. Muskie secured 2,635 votes and won the election to most people's surprise on September 9, 1946. During this time, the Maine Senate was stacked 30-to-3 and the House was stacked 127-to-24 Republicans against Democrats.

[Witherell (2014), p. 79]

Muskie was assigned to the committees on federal and military relations during his first year. He advocated for

bipartisanship

Bipartisanship, sometimes referred to as nonpartisanship, is a political situation, usually in the context of a two-party system (especially those of the United States and some other western countries), in which opposing political parties find c ...

, which won him widespread support across political parties. On October 17, 1946, Muskie's law practice sustained a large fire, costing him an estimated $2,300 in damages. However, a yearly stipend of $800 and help from other business leaders who were affected by the fire quickly restarted his practice.

Muskie's work with city ordinances in

Waterville prompted locals to ask him to run in the 1947 election to become Mayor of Waterville, against banker Russel W. Squire. Perhaps due to

incumbency advantage

The incumbent is the current holder of an office or position. In an election, the incumbent is the person holding or acting in the position that is up for election, regardless of whether they are seeking re-election.

There may or may not be a ...

, Muskie lost the election with 2,853 votes, 434 votes behind Squire. Some historians believe that his loss had to do with his inability to gain traction with

Franco-American voters.

Muskie continued his political involvement locally by securing a position on the Waterville Board of Zoning Adjustment in 1948 and stayed in this part-time position until he became governor. He later returned to the House to start his second term in 1948 as

Minority Leader against heavy Republican opposition. Muskie was appointed the chairman of the platform committee during the 1949 Maine Democratic Convention. During the convention, he brought together a variety of the political elite of Maine—notably

Frank M. Coffin and Victor Hunt Harding—to plan a comeback for the party. On February 8, 1951, Muskie resigned from the Maine House of Representatives to become acting director for the Maine

Office of Price Stabilization

An office is a space where the employees of an organization perform administrative work in order to support and realize the various goals of the organization. The word "office" may also denote a position within an organization with specific dut ...

. He moved to

Portland

Portland most commonly refers to:

*Portland, Oregon, the most populous city in the U.S. state of Oregon

*Portland, Maine, the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maine

*Isle of Portland, a tied island in the English Channel

Portland may also r ...

soon after and was assigned the inflation-control and price-ceiling divisions.

[Witherell (2014), p. 99] His job required him to move across Maine to spread word about economic incentives which he used to increase his name recognition.

He served as the regional director at the Office of Price Stabilization from 1951 to 1952.

Upon leaving the Office he was asked to join the

Democratic National Committee

The Democratic National Committee (DNC) is the principal executive leadership board of the United States's Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party. According to the party charter, it has "general responsibility for the affairs of the ...

as a member; he served on the committee from 1952 to 1956.

In April 1953, while working on renovations for his family home in Waterville, Muskie broke through a balcony railing, falling down two flights of stairs.

[Witherell (2014), p. 109] He landed on his back, knocked

unconscious. He was rushed to the hospital, where he remained unconscious for two days.

Doctors believed that Muskie was in a coma, so they gave him comatose-specific medication which caused him to regain consciousness but start to

hallucinate

A hallucination is a perception in the absence of an external stimulus that has the compelling sense of reality. They are distinguishable from several related phenomena, such as dreaming (REM sleep), which does not involve wakefulness; pseud ...

. Muskie tried to jump out of the hospital window, but was restrained by staff members. After a couple of months, through

physical rehabilitation

Physical therapy (PT), also known as physiotherapy, is a healthcare profession, as well as the care provided by physical therapists who promote, maintain, or restore health through patient education, physical intervention, disease prevention, ...

and corrective braces, he was able to walk once more.

Governor of Maine, 1955–1959

Gubernatorial campaign

After establishing a prominent presence in the Maine State Legislature and with the Office of Price Stabilization, he officially launched his bid in the

1954 Maine gubernatorial race as a Democrat.

Burton M. Cross, the Republican incumbent governor, was seeking reelection. Had he won, he would have been

the fifth consecutive Governor to be reelected. Throughout the election Muskie was viewed as the

underdog

An underdog is a person or group in a competition, usually in sports and creative works, who is largely expected to lose. The party, team, or individual expected to win is called the favorite or wikt:top dog, top dog. In the case where an under ...

because of the

Republican stronghold in Maine. Muskie acknowledged this himself by saying, "

his ismore as a duty than an opportunity because there was no chance of a Democrat winning."

A variety of personal reasons motivated his run. Muskie was deeply in debt owing five thousand dollars in hospital bills and maintained a rising mortgage. At the time of his election, the salary for the Governor of Maine was set at ten thousand dollars annually.

While he was campaigning he was offered a position involving full partnership at a prestigious Rumford law firm that maintained "clients and income that

uskiehad not achieved in fourteen years of practice in Waterville."

His final choice reflected his 'society over self' mentality and decided to pursue the election.

[Robert Mason, ''Richard Nixon and the Quest for a New Majority'' (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina, 2004), p. 153.] He announced his candidacy for the office on April 8, 1954.

[Blomquist 1999, p. 93]

Muskie ran on a

party platform

A political party platform (American English), party program, or party manifesto (preferential term in British and often Commonwealth English) is a formal set of principal goals which are supported by a political party or individual candidate, t ...

of environmentalism and public investment. His environmental platform argued for the establishment of the Maine Department of Conservation to "have jurisdiction of forestry, inland fish and game, sea and shore

fisheries

Fishery can mean either the enterprise of raising or harvesting fish and other aquatic life or, more commonly, the site where such enterprise takes place ( a.k.a., fishing grounds). Commercial fisheries include wild fisheries and fish farm ...

, mineral, water, and other

natural resource

Natural resources are resources that are drawn from nature and used with few modifications. This includes the sources of valued characteristics such as commercial and industrial use, aesthetic value, scientific interest, and cultural value. ...

s" and the creation of

anti-pollution legislation. He stressed the need for "a two-party" approach to Maine politics with resonated with both Democratic and Republican voters wishing to see change. Muskie's central

campaign slogan

Slogans and catchphrases are used by politicians, political parties, militaries, activists, and protestors to express or encourage particular beliefs or actions. List

International usage

* Better dead than Redanti-Communist slogan

* Black is ...

was "Maine Needs A Change" referencing the multi-year Republican stronghold.

He criticized the Republican Party for neglecting the environment, failing to restart the economy, underutilizing skilled labor forces, and ignoring public investment.

[Blomquist 1999, pp. 93–94]

He successively won the Democratic gubernatorial nomination, and then the general election by a majority popular vote on September 13, 1954. The

upset victory made Muskie the first Democrat to be elected chief executive of Maine since

Louis J. Brann

Louis Jefferson Brann (July 6, 1876 – February 3, 1948) was an American lawyer and political figure. He was the 56th governor of Maine.

Early life

Brann was born in Madison, Maine to Charles M. Brann and Nancy Lancaster Brann. He attended sc ...

in 1934. His election has been viewed as a causal link to the end of Republican political dominance in Maine and the rise of

the Democratic Party.

After his win, he was asked by other Democrats running in elections outside of Maine to make a series of campaign stops.

First term

Muskie was inaugurated as the

64th Governor of Maine

The governor of Maine is the head of government of the U.S. state of Maine. Before Maine was admitted to the Union in 1820, Maine was part of Massachusetts and the governor of Massachusetts was chief executive.

The current governor of Maine is J ...

on January 6, 1955. He was the state's first

Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

governor.

Shortly after his assumption of the office, the next election cycle stacked the legislature with a 4-to-1 Republican-Democrat ratio against Muskie. Through

bipartisanship

Bipartisanship, sometimes referred to as nonpartisanship, is a political situation, usually in the context of a two-party system (especially those of the United States and some other western countries), in which opposing political parties find c ...

and his aggressive personality

he managed to pass the majority of his party platform. Constituents pressured him to more aggressively pursue water control and anti-pollution legislation. In August, the

Maine State Legislature

The Maine State Legislature is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Maine. It is a bicameral body composed of the lower house Maine House of Representatives and the upper house Maine Senate. The legislature convenes at the State House in ...

authorized him to take extraordinary action to control the state's pollution standards. He used this authority to sign the New England Interstate Water Pollution Control Compact on August 31, 1955. This compact required member states to pay for anti-pollution measures collectively. Conservative members of the Chamber of Commerce fought back against Muskie in his attempt to allocate money to the compact and greatly reduced the amount paid. One of the chief concerns of Muskie during this time was economic development. Maine's population was aging, putting pressure on

welfare services. He expanded certain programs and cut down on others in order rebalance state spending.

Before leaving office Muskie signed an

executive order

In the United States, an executive order is a directive by the president of the United States that manages operations of the federal government. The legal or constitutional basis for executive orders has multiple sources. Article Two of the ...

extending the gubernatorial term to four years.

He expanded the territory comprising

Baxter State Park

Baxter State Park is a large wilderness area permanently preserved as a state park in Northeast Piscataquis, Piscataquis County in north-central Maine, United States. It is in the North Maine Woods region and borders the Katahdin Woods and Wa ...

by 3,569 acres and purchased 40 acres (1.7 million ft

2) of

Cape Elizabeth

Cape Elizabeth is a town in Cumberland County, Maine, United States. The town is part of the Portland– South Portland–Biddeford, Maine, metropolitan statistical area. As of the 2020 census, Cape Elizabeth had a population of 9,535 ...

from the federal government for $28,000. He also created the Department of Development of Commerce and Industry and Maine Industrial Building Authority.

In February 1955, he was briefed on atomic energy power by the

United States Atomic Energy Commission

The United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) was an agency of the United States government established after World War II by the U.S. Congress to foster and control the peacetime development of atomic science and technology. President Harry ...

leading him to limit the expansion of atomic-powered electrical facilities.

Second term

On September 10, 1956, Muskie was re-elected Governor of Maine by 55,859 votes against Republican

Willis A. Trafton. He won 14 of the 16 counties. He began his second term by aggressively enforcing environmental standards. In 1957, he sanctioned a $29 million highway

bond

Bond or bonds may refer to:

Common meanings

* Bond (finance), a type of debt security

* Bail bond, a commercial third-party guarantor of surety bonds in the United States

* Fidelity bond, a type of insurance policy for employers

* Chemical bond, t ...

.

This bond funded the largest road construction ever undertaken by Maine. The highway included 91 bridges and was extended in 1960 and 1967 by

Interstate 95

Interstate 95 (I-95) is the main north–south Interstate Highway on the East Coast of the United States, running from U.S. Route 1 (US 1) in Miami, Florida, north to the Houlton–Woodstock Border Crossing between Maine and the ...

.

During his tenure as Governor he retained a reputation for increased spending in public education, subsidized hospitals, modernized state facilities, and cumulatively raised state sale taxes by 1%.

He added $4 million to infrastructure development focusing on roads and river maintenance. Muskie pushed aggressive

economic expansion

An economic expansion is an upturn in the level of economic activity and of the goods and services available. It is a finite period of growth, often measured by a rise in real GDP, that marks a reversal from a previous period, for example, whi ...

ism.

In 1957, he founded the Maine Guarantee Authority which combated

economic maturation-related job loss, making capital more accessible for business owners. Muskie also sporadically lowered

sales tax

A sales tax is a tax paid to a governing body for the sales of certain goods and services. Usually laws allow the seller to collect funds for the tax from the consumer at the point of purchase. When a tax on goods or services is paid to a govern ...

, increased the

minimum wage

A minimum wage is the lowest remuneration that employers can legally pay their employees—the price floor below which employees may not sell their labor. List of countries by minimum wage, Most countries had introduced minimum wage legislation b ...

and furthered labor protections leading to a marked increase in

consumer spending

Consumer spending is the total money spent on final goods and services by individuals and households.

There are two components of consumer spending: induced consumption (which is affected by the level of income) and autonomous consumption (which ...

.

He amended the

constitution of Maine in order to divert $20 million in public funds into private investment. He increased subsidies to expensive institutions such as public primary and secondary schools as well as universities. Although initially founded in 1836, the

Maine State Museum

The Maine State Museum is the official Maine government's museum and is located at 230 State Street, adjacent to the Maine State House, in Augusta, Maine, Augusta. Its collections focus on the state's pre-history, history, and natural science.

...

was closed and reopened six times before Muskie permanently

endowed

A financial endowment is a legal structure for managing, and in many cases indefinitely perpetuating, a pool of financial, real estate, or other investments for a specific purpose according to the will of its founders and donors. Endowments are ...

it in 1958.

His governorship exploited multi-factionalism in the Republican Party, leading to a vast expansion of the

Democratic Party in Maine. From 1954 to 1974, the party doubled in size, while the Republican Party steadily decreased from 262,367 to 227,828 registered members.

Numerous state politicians mimicked his political style to push their programs through various local governments and garnered electoral success.

His executive appointments of moderate politicians shifted the entire Republican establishment in the state to the left.

This shift garnered comparisons to

Hubert Humphrey

Hubert Horatio Humphrey Jr. (May 27, 1911 – January 13, 1978) was an American politician who served from 1965 to 1969 as the 38th vice president of the United States. He twice served in the United States Senate, representing Minnesota from 19 ...

's influence in

Minnesota

Minnesota ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Upper Midwestern region of the United States. It is bordered by the Canadian provinces of Manitoba and Ontario to the north and east and by the U.S. states of Wisconsin to the east, Iowa to the so ...

and

George McGovern

George Stanley McGovern (July 19, 1922 – October 21, 2012) was an American politician, diplomat, and historian who was a U.S. representative and three-term U.S. senator from South Dakota, and the Democratic Party (United States), Democ ...

's impact in

South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux language, Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state, state in the West North Central states, North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Dakota people, Dakota Sioux ...

.

During his last months as governor he changed his office's term from two years to four years.

Shortly before leaving office he moved Maine's general election date from September to November conclusively ending the notion that "

as Maine goes, so goes the nation

"As Maine goes, so goes the nation" was once a maxim in United States politics. The phrase described Maine's reputation as a bellwether state for presidential elections. Maine's September election of a governor predicted the party outcome of the ...

". This was attempted thirty-six times before Muskie brought about a constitutional amendment that moved the date.

Muskie resigned on January 2, 1959, to take his seat in the

United States Senate

The United States Senate is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the upper house, with the United States House of Representatives, U.S. House of Representatives being the lower house. Together, the Senate and ...

after the

1958 Senate election. He was succeeded by Republican

Robert Haskell

Robert Nance Haskell (August 24, 1903 – December 3, 1987) was a Maine state senator and the 65th governor of Maine for five days in 1959.

Haskell graduated from the University of Maine with an engineering degree in 1925. He became a design en ...

in an interim capacity until the Governor-elect, Democrat

Clinton Clauson

Clinton Amos Clauson (March 28, 1895 – December 30, 1959) was an American politician who served as the 66th governor of Maine from January 1959 until his death in December of that year. A Democrat, Clauson previously held office in Waterville ...

, was inaugurated. Muskie was officially succeeded by Clauson on January 6, 1959.

United States Senate, 1959–1980

Elections and campaigns

Muskie's first contestation for the

Senate of the United States

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the eld ...

was in

1958

Events

January

* January 1 – The European Economic Community (EEC) comes into being.

* January 3 – The West Indies Federation is formed.

* January 4

** Edmund Hillary's Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition completes the thir ...

. He announced his intent to challenge incumbent Republican Senator

Frederick G. Payne

Frederick George Payne (July 24, 1904 – June 15, 1978) was an American businessman and politician. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he served as a United States Senate, U.S. senator from Maine from 1953 to ...

on March 20, 1958. Muskie won the election with 61% of the vote against Payne's 39%. Muskie's victory made him the first Democrat elected to the Senate in Maine, with the state's previous Democratic Senator having been appointed by the legislature. He was one of the 12 Democrats who overtook Republican incumbents and established the party as the party-of-house during the election cycle.

''

The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' reported that during this election that the

absentee ballot

Absentee or The Absentee may refer to:

* Absentee (band), a British band

* The Absentee, a novel by Maria Edgeworth, published in 1812 in ''Tales of Fashionable Life''

* ''The Absentee'' (1915 film), a 1915 American silent film directed by Christy ...

s requested for Democrats increased considerable signaling voter-discontent with

Republican ideology

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

.

This election was considered the largest single-party gain in the Senate's history.

He ran for a second term in

1964

Events January

* January 1 – The Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland is dissolved.

* January 5 – In the first meeting between leaders of the Roman Catholic and Orthodox churches since the fifteenth century, Pope Paul VI and Patria ...

, running against Republican

Clifford McIntire. Muskie won with 67% of the vote.

Election eve speech

His third campaign and election to the Senate occurred in 1970. During the

1970 elections, Muskie secured 62% of the vote against Republican

Neil S. Bishop

Neil S. Bishop (November 10, 1903 – February 24, 1989) was an American dairy farmer, educator and politician from Maine.

Bishop was born in Presque Isle, Maine, although his family moved when he was young to Bowdoinham, Maine. He served four ...

's 38%. The elections were seen as tumultuous due to the United States' involvement in the

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

and rising unpopularity of incumbent president

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 until Resignation of Richard Nixon, his resignation in 1974. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

. On the night of poll-opening Muskie gave a nationwide, 14-minute speech to addressed American voters following a similar address by Nixon. Dubbed the "election eve speech"

it spoke to

American exceptionalism

American exceptionalism is the belief that the United States is either distinctive, unique, or exemplary compared to other nations. Proponents argue that the Culture of the United States, values, Politics of the United States, political system ...

and against "torrents of falsehood and insinuation".

The speech was considered

bipartisan

Bipartisanship, sometimes referred to as nonpartisanship, is a political situation, usually in the context of a two-party system (especially those of the United States and some other western countries), in which opposing Political party, politica ...

and was well received by both parties. Political analysts believed that the speech influenced voting patterns during the election as there were thirty million listeners.

Commentators received the speech as "essentially evangelical"

and indicative of "a volcanic private temper but a soothing public manner".

The most famous passage from the speech was widely commented on by the public for its biting nature and critique of "

politics of fear":

I am speaking from Cape Elizabeth

Cape Elizabeth is a town in Cumberland County, Maine, United States. The town is part of the Portland– South Portland–Biddeford, Maine, metropolitan statistical area. As of the 2020 census, Cape Elizabeth had a population of 9,535 ...

, Maine, to discuss with you the election campaign which is coming to a close. In the heat of our campaigns, we have all become accustomed to a little anger and exaggeration. That is our system. It has worked for almost two hundred years—longer than any other political system in the world. But in these elections of 1970, something has gone wrong. There has been name-calling and deception of almost unprecedented volume. Honorable men have been slandered. Faithful servants of the country have had their motives questioned and their patriotism doubted. It has been led . . . inspired . . . and guided . . . from the highest offices in the land. ... We cannot make America small. ... Ordinarily that division is not between parties, but between men and ideas. But this year the leaders of the Republican party have intentionally made that line a party line. They have confronted you with exactly that choice. Thus—in voting for the Democratic party tomorrow—you cast your vote for trust—not just in leaders or policies—but for trusting your fellow citizens . . . in the ancient traditions of this home for freedom . . . and most of all, for trust in yourself.

The ''

Portland Press Herald

The ''Portland Press Herald'' (abbreviated as ''PPH''; Sunday edition ''Maine Sunday Telegram'') is a daily newspaper based in South Portland, Maine, with a statewide readership. The ''Press Herald'' mainly serves southern Maine and is focused ...

'' on November 4, 1970, noted it akin to

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

's

fire-side chats "with video".

The speech has been the subject of numerous studies regarding "the dimensions of the televised public address as an emerging rhetorical genre of pervasive influence in contemporary affairs".

In his

fourth and final election, Muskie ran against Republican

Robert A. G. Monks

Robert Augustus Gardner Monks (December 4, 1933 – April 29, 2025) was an American author, shareholder activist, corporate governance advocate, attorney, corporate director, venture capitalist and energy company executive — as well as po ...

in 1976; he won 60% of the vote compared to Monk's 40%. The elections coincided with the election of

Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (October 1, 1924December 29, 2024) was an American politician and humanitarian who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party ...

as president, leading to a large influx of Democratic support, though Carter lost Maine to incumbent President

Gerald Ford

Gerald Rudolph Ford Jr. (born Leslie Lynch King Jr.; July 14, 1913December 26, 2006) was the 38th president of the United States, serving from 1974 to 1977. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, Ford assumed the p ...

in the

1976 presidential election.

First and second term

Edmund Muskie was sworn into office as

U.S. Senator from Maine on January 3, 1959. His first couple of months in the Senate earned a reputation for being combative and often sparred with

Majority Leader,

Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), also known as LBJ, was the 36th president of the United States, serving from 1963 to 1969. He became president after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, under whom he had served a ...

, who subsequently relegated him to outer seats in the Senate. In the next five years, he gained significant power and influence and was considered among the most effective legislators in the Senate.

However, increased power and influence prompted supporters in Maine to label him "an honorary Kennedy", alluding to the indifference

John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), also known as JFK, was the 35th president of the United States, serving from 1961 until his assassination in 1963. He was the first Roman Catholic and youngest person elected p ...

had to Massachusetts when first gaining political traction.

Muskie used the influence gained in his first two terms to push a vast expansion of environmentalism in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

His specific goals were to curb pollution and provide a cleaner environment. Occasional speeches on

environmental preservation

Environmentalism is a broad philosophy, ideology, and social movement about supporting life, habitats, and surroundings. While environmentalism focuses more on the environmental and nature-related aspects of green ideology and politics, ecologi ...

earned him the nickname "Mr. Clean".

He served his entire career in the Senate as a member of the

Committee on Public Works, a committee he used to execute the majority of his environmental legislation.

He served on the

Committee on Banking and Currency from 1959 to 1970; the

Committee on Government Operations until 1978.

As a member of the Public Works Committee, he traveled to the

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

in 1959.

He

sponsored the

Intergovernmental Relations Act, later that year.

In 1962, he co-founded the

United States Capital Historical Society along with other members of Congress. The same year, members of Congress elected him to serve as the first chair of the Subcommittee on Air and Water Pollution.

In 1963, he was the first to sponsor a new Act to regulate air pollution. The

Clean Air Act of 1963

The Clean Air Act (CAA) is the United States' primary federal air quality law, intended to reduce and control Air pollution in the United States, air pollution nationwide. Initially enacted in 1963 and amended many times since, it is one of th ...

was written and developed by Muskie and his aide Leon Billings.

His first major accomplishment was the passage of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 () is a landmark civil rights and United States labor law, labor law in the United States that outlaws discrimination based on Race (human categorization), race, Person of color, color, religion, sex, and nationa ...

. He assembled more than one hundred votes for the proposed legislation eventually passing it.

Also during 1964, he was critical of

J. Edgar Hoover

John Edgar Hoover (January 1, 1895 – May 2, 1972) was an American attorney and law enforcement administrator who served as the fifth and final director of the Bureau of Investigation (BOI) and the first director of the Federal Bureau o ...

's management of the

Federal Bureau of investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic Intelligence agency, intelligence and Security agency, security service of the United States and Federal law enforcement in the United States, its principal federal law enforcement ag ...

. Muskie was upset by its "overzealous surveillance and its director's intemperance".

Muskie also sponsored the construction of the

Roosevelt Campobello International Park

Roosevelt Campobello International Park preserves the house and surrounding landscape of the summer retreat of Franklin D. Roosevelt, Eleanor Roosevelt and their family. It is located on the southern tip of Campobello Island in the Canadian prov ...

near

Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

's New Brunswick estate.

Due to its international nature, Muskie was asked to chair a joint U.S.-Canada commission to maintain the park.

In 1965, he was again sponsored the

Water Quality Act (later to be known as the Clean Water Act). He was the floor manager for the discussion and led to its passage in 1965 and its successful amendments in 1970.

Alongside President Johnson's

Great Society

The Great Society was a series of domestic programs enacted by President Lyndon B. Johnson in the United States between 1964 and 1968, aimed at eliminating poverty, reducing racial injustice, and expanding social welfare in the country. Johnso ...

and

War on Poverty programs, Muskie drafted the

Model Cities Bill which eventually passed both houses of Congress in 1966.

Previously, combative with Johnson, Muskie began developing a more cooperative relationship with him. During Johnson's signing of the

Intergovernmental Cooperation Act he said: I am pleased that Senator Muskie could be with us this afternoon. I believe that no man has done more to encourage cooperation among the National Government, the States, and the cities." Also in 1966, Muskie was elected assistant

Democratic whip and served as the floor manager for the

Clean Water Restoration Act.

During 1967 the popular sentiment in the U.S. was

anti-war

An anti-war movement is a social movement in opposition to one or more nations' decision to start or carry on an armed conflict. The term ''anti-war'' can also refer to pacifism, which is the opposition to all use of military force during conf ...

, which prompted Muskie to visit

Vietnam

Vietnam, officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV), is a country at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of about and a population of over 100 million, making it the world's List of countries and depende ...

to inform his political stance in 1968. Prior to his visiting the country, he debated with a congressman on a pro-war platform. After the trip, he became a leading voice for the anti-war movement and entered into the ongoing debate by speaking at the year's Democratic Convention. His speech was followed by "tens of thousands of protestors surrounded the convention and violent clashes with police carried on for five days."

He wrote to Johnson personally asserting his position on the

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

. He made the case that the U.S. ought to withdraw from Vietnam as quickly as possible.

Months later, he wrote to the president again urging him to end

the bombing of North Vietnam. During the same year, he traveled with other Senators to the

Republic of South Vietnam

The Provisional Revolutionary Government of the Republic of South Vietnam (PRG, ), was formed on 8 June 1969, by the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam) as an armed underground government opposing the government of the Republic of ...

to validate their elections.

Later, at the

1968 Democratic National Convention

The 1968 Democratic National Convention was held August 26–29 at the International Amphitheatre in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Earlier that year incumbent President Lyndon B. Johnson had announced he would not seek reelection, thus making ...

, he led the debate for the administration plank on Vietnam, which sparked public outrage. On October 15, 1969, he was welcomed to the green at

Yale University

Yale University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701, Yale is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Stat ...

to address the issues regarding his vote but chose to decline the offer and speak that night at his alma mater,

Bates College

Bates College () is a Private college, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Lewiston, Maine. Anchored by the Historic Quad, the campus of Bates totals with a small urban campus which includes 33 Victorian ...

, in

Lewiston, Maine.

His decision to do so was widely criticized by the Democratic party and Yale University officials.

From 1967 to 1969, he served as the chair of

Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee

The Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee (DSCC) is the Democratic Hill committee for the United States Senate. Its purpose is to elect Democrats to the United States Senate. The DSCC's current Chair is Senator Kirsten Gillibrand of Ne ...

.

He voted against the appointment of

Clement Haynsworth

Clement Furman Haynsworth Jr. (October 30, 1912 – November 22, 1989) was a United States federal judge, United States circuit judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit. He was also an Unsuccessful nominations to the Supr ...

to the

U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that turn on question ...

.

Third and fourth term

Muskie's third term began in 1970 by co-sponsoring the

McGovern-Hatfield resolution to limit military intervention in the Vietnam War.

During this time

Harold Carswell

George Harrold Carswell (December 22, 1919 – July 13, 1992) was a United States circuit judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit and a United States district judge of the United States District Court for the Northern Dis ...

was seeking appointment to the U.S. Supreme Court. Muskie voted against him and Carswell failed the confirmation process.

Muskie also proposed a six-month ban on domestic and

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

development of nuclear technologies to taper the

nuclear arms race

The nuclear arms race was an arms race competition for supremacy in nuclear warfare between the United States, the Soviet Union, and their respective allies during the Cold War. During this same period, in addition to the American and Soviet nuc ...

.

As chair of the congressional environmental committee, he and fellow committee members including

Howard Baker

Howard Henry Baker Jr. (November 15, 1925 June 26, 2014) was an American politician, diplomat and photographer who served as a United States Senator from Tennessee from 1967 to 1985. During his tenure, he rose to the rank of Senate Minority Le ...

introduced the

Clean Air Act of 1970

The Clean Air Act (CAA) is the United States' primary federal air quality law, intended to reduce and control air pollution nationwide. Initially enacted in 1963 and amended many times since, it is one of the United States' first and most in ...

, which was co-written by the committee's staff director Leon Billings and minority staff director Tom Jorling. As part of the act, he told the automobile industry it would need to reduce its tailpipe air pollution emissions by 90% by 1977. He also co-wrote amendments to the Federal Water Pollution Act, more commonly known as the

Clean Water Act

The Clean Water Act (CWA) is the primary federal law in the United States governing water pollution. Its objective is to restore and maintain the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the nation's waters; recognizing the primary respo ...

, and urged his fellow Congress members to adopt it, saying "The country was once famous for its rivers ... But today, the rivers of this country serve as little more than sewers to the seas. ... The danger to health, the environmental damage, the economic loss can be anywhere." The bill enjoyed

bipartisan support in the U.S. Congress and was passed by the House on November 29, 1971, and the Senate on March 29, 1972. While congressional support was enough to enact it into law, President

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 until Resignation of Richard Nixon, his resignation in 1974. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

exercised his

executive veto on the bill and stopped it from becoming law. However, after further campaigning by Muskie, the

Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

and

House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entities. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often ...

passed the bill 247–23 to override Nixon's veto.

The bill was historic in that it established the regulation of pollutants in the federal and state waters of the U.S., created extended authority for the

Environmental Protection Agency

Environmental Protection Agency may refer to the following government organizations:

* Environmental Protection Agency (Queensland), Australia

* Environmental Protection Agency (Ghana)

* Environmental Protection Agency (Ireland)

* Environmenta ...

, and created water health standards. Also in 1971, Muskie was asked to join the

Senate Foreign Relations Committee

The United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations is a standing committee of the U.S. Senate charged with leading foreign-policy legislation and debate in the Senate. It is generally responsible for authorizing and overseeing foreign a ...

; he traveled to Europe and the Middle East in this capacity.

After concluding his

1968 campaign for the

White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. Located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest (Washington, D.C.), NW in Washington, D.C., it has served as the residence of every U.S. president ...

, he returned to the Senate. While in Chattanooga, the

shooting of two black students at

Jackson State College

Jackson State University (Jackson State or JSU) is a public historically black research university in Jackson, Mississippi. It is a member of the Thurgood Marshall College Fund and classified among "R2: Doctoral Universities – High research ...

in 1970 by the Mississippi State Police, prompted Muskie to hire a

jet airliner

A jet airliner or jetliner is an airliner powered by jet engines (passenger jet aircraft). Airliners usually have twinjet, two or quadjet, four jet engines; trijet, three-engined designs were popular in the 1970s but are less common today. Air ...

to take approximately one hundred people to see the bullet holes and attend a funeral of one of the victims. Critics in Maine described his actions as "rash and self serving" but Muskie publicly expressed no regret for his actions.

At an event in Los Angeles, he publicly stated his support for several

black empowerment movements in California, which garnered the attention of numerous media outlets, and black city councilman Thomas Bradley.

In 1970, Muskie was chosen to articulate the Democratic party's message to congressional voters before the midterm elections. His national stature was raised as a major candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1972. In 1973, he gave the Democratic response to Nixon's

State of the Union address

The State of the Union Address (sometimes abbreviated to SOTU) is an annual message delivered by the president of the United States to a joint session of the United States Congress near the beginning of most calendar years on the current condit ...

.

During this time, he was appointed the chair of the intergovernmental relations subcommittee. Considered "a backwater assignment", Muskie used it to advocate for a widening of governmental responsibilities, limiting the power of

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 until Resignation of Richard Nixon, his resignation in 1974. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

's "

Imperial Presidency" and advancing

New Federalism

New Federalism is a political philosophy of devolution, or the transfer of certain powers from the United States federal government back to the states. The primary objective of New Federalism, unlike that of the eighteenth-century political philo ...

ideals.

Muskie served as the chairman of the

Senate Budget Committee

The United States Senate Committee on the Budget was established by the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974. It is responsible for drafting Congress's annual budget plan and monitoring action on the budget for the Federal ...

through the

Ninety-third to the

Ninety-sixth Congresses from 1973 to 1980. During this time, Congress founded the

Congressional Budget Office

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) is a List of United States federal agencies, federal agency within the United States Congress, legislative branch of the United States government that provides budget and economic information to Congress.

I ...

in order to challenge Nixon's budget request. Prior to 1974, there was no formal process for establishing a

federal budget, so Congress founded the office under the auspices of the Senate Budget Committee. As chairman, Muskie presided over, formulated, and approved of the creation of the

United States budget process

The United States budget process is the framework used by Congress and the President of the United States to formulate and create the United States federal budget. The process was established by the Budget and Accounting Act of 1921, the Congre ...

.

[Archived a]

Ghostarchive

and th

Wayback Machine

In 1977, he amended

Federal Water Pollution Control Act of 1972 along with others, to pass the

Clean Water Act of 1977.

[Blomquist (1999), p. 261] These new additions incorporated "non-degradation" or "clean growth" policies intended to limit

negative externalities

In economics, an externality is an indirect cost (external cost) or indirect benefit (external benefit) to an uninvolved third party that arises as an effect of another party's (or parties') activity. Externalities can be considered as unpriced ...

.

In 1978, he made minor adjustments to the

Resource Conservation and Recovery Act

The Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA), enacted in 1976, is the primary federal law in the United States governing the disposal of solid waste and hazardous waste.United States. Resource Conservation and Recovery Act. , , ''et seq., ...

and the "

Superfund

Superfund is a United States federal environmental remediation program established by the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980 (CERCLA). The program is administered by the United States Environmental Pro ...

".

Campaigns for the White House

1968 presidential election

Campaign

In 1968, Muskie was nominated for vice president on the Democratic ticket with sitting Vice President

Hubert Humphrey

Hubert Horatio Humphrey Jr. (May 27, 1911 – January 13, 1978) was an American politician who served from 1965 to 1969 as the 38th vice president of the United States. He twice served in the United States Senate, representing Minnesota from 19 ...

. Humphrey asked Muskie to be his running mate because Muskie, in addition to being of Polish

Catholic