Monterey County, California Articles Missing Geocoordinate Data on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Monterey ( ; ) is a city situated on the southern edge of

Long before the arrival of Spanish explorers, the Rumsen

Long before the arrival of Spanish explorers, the Rumsen

Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821, but the civil and religious institutions of Alta California remained much the same until the 1830s, when the

Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821, but the civil and religious institutions of Alta California remained much the same until the 1830s, when the

Monterey's noise pollution has been mapped to define the principal sources of noise and to ascertain the areas of the population exposed to significant levels. Principal sources are the

Monterey's noise pollution has been mapped to define the principal sources of noise and to ascertain the areas of the population exposed to significant levels. Principal sources are the

Monterey's climate is regulated by its proximity to the Pacific Ocean, resulting in a

Monterey's climate is regulated by its proximity to the Pacific Ocean, resulting in a

There were 12,184 households, out of which 2,475 (20.3%) had children under the age of 18 living in them, 4,690 (38.5%) were opposite-sex married couples living together, 902 (7.4%) had a female householder with no husband present, 371 (3.0%) had a male householder with no wife present. 4,778 households (39.2%) were made up of individuals, and 1,432 (11.8%) had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.08. There were 5,963 families (48.9% of all households); the average family size was 2.81.

The population was spread out, with 4,266 people (15.3%) under the age of 18, 3,841 people (13.8%) aged 18 to 24, 8,474 people (30.5%) aged 25 to 44, 6,932 people (24.9%) aged 45 to 64, and 4,297 people (15.5%) who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36.9 years. For every 100 females, there were 101.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 100.6 males.

There were 12,184 households, out of which 2,475 (20.3%) had children under the age of 18 living in them, 4,690 (38.5%) were opposite-sex married couples living together, 902 (7.4%) had a female householder with no husband present, 371 (3.0%) had a male householder with no wife present. 4,778 households (39.2%) were made up of individuals, and 1,432 (11.8%) had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.08. There were 5,963 families (48.9% of all households); the average family size was 2.81.

The population was spread out, with 4,266 people (15.3%) under the age of 18, 3,841 people (13.8%) aged 18 to 24, 8,474 people (30.5%) aged 25 to 44, 6,932 people (24.9%) aged 45 to 64, and 4,297 people (15.5%) who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36.9 years. For every 100 females, there were 101.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 100.6 males.

There were 13,584 housing units at an average density of , of which 4,360 (35.8%) were owner-occupied, and 7,824 (64.2%) were occupied by renters. The homeowner vacancy rate was 2.0%; the rental vacancy rate was 6.5%. 9,458 people (34.0% of the population) lived in owner-occupied housing units and 15,849 people (57.0%) lived in rental housing units.

There were 13,584 housing units at an average density of , of which 4,360 (35.8%) were owner-occupied, and 7,824 (64.2%) were occupied by renters. The homeowner vacancy rate was 2.0%; the rental vacancy rate was 6.5%. 9,458 people (34.0% of the population) lived in owner-occupied housing units and 15,849 people (57.0%) lived in rental housing units.

As of the census of 2000, there were 29,674 people, 12,600 households, and 6,476 families residing in the city. The population density was . There were 13,382 housing units at an average density of . The racial makeup of the city was 80.8% White, 10.9% Hispanic, 7.4% Asian, 2.5% African American, 0.6% Native American, 0.3% Pacific Islander, 3.9% from other races, and 4.5% from two or more races.

There were 12,600 households, out of which 21.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 39.5% were married couples living together, 8.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 48.6% were non-families. 37.0% of all households consisted of individuals, and 11.0% had a lone dweller who is over 64. The average household size was 2.13 and the average family size was 2.82.

The age distribution is as follows: 16.6% under the age of 18, 13.1% from 18 to 24, 33.8% from 25 to 44, 21.7% from 45 to 64, and 14.9% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females, there were 96.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 96.1 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $49,109, and the median income for a family was $58,757. Males had a median income of $40,410 versus $31,258 for females. The per capita income for the city was $27,133. About 4.4% of families and 7.8% of the population were below the poverty line, including 6.5% of those under age 18 and 4.8% of those age 65 or over.

As of the census of 2000, there were 29,674 people, 12,600 households, and 6,476 families residing in the city. The population density was . There were 13,382 housing units at an average density of . The racial makeup of the city was 80.8% White, 10.9% Hispanic, 7.4% Asian, 2.5% African American, 0.6% Native American, 0.3% Pacific Islander, 3.9% from other races, and 4.5% from two or more races.

There were 12,600 households, out of which 21.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 39.5% were married couples living together, 8.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 48.6% were non-families. 37.0% of all households consisted of individuals, and 11.0% had a lone dweller who is over 64. The average household size was 2.13 and the average family size was 2.82.

The age distribution is as follows: 16.6% under the age of 18, 13.1% from 18 to 24, 33.8% from 25 to 44, 21.7% from 45 to 64, and 14.9% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females, there were 96.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 96.1 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $49,109, and the median income for a family was $58,757. Males had a median income of $40,410 versus $31,258 for females. The per capita income for the city was $27,133. About 4.4% of families and 7.8% of the population were below the poverty line, including 6.5% of those under age 18 and 4.8% of those age 65 or over.

Once called Ocean View Boulevard, the street was renamed Cannery Row in 1953 in honor of writer John Steinbeck, who had written a well-known novel of the same name. It has now become a

Once called Ocean View Boulevard, the street was renamed Cannery Row in 1953 in honor of writer John Steinbeck, who had written a well-known novel of the same name. It has now become a  The Governor

The Governor

Monterey is the home of the

Monterey is the home of the

Steinbeck's friends included some of the city's more colorful characters, among them

Steinbeck's friends included some of the city's more colorful characters, among them

The Wharf Theater opened on Fisherman's Wharf on May 18, 1950, with a

The Wharf Theater opened on Fisherman's Wharf on May 18, 1950, with a

Monterey is governed by a mayor and four city council members. As of December 2021, the mayor is Tyller Williamson and the city council members are Kim Barber, Gino Garcia, Alan Haffa, and Ed Smith.

The City of Monterey provides base maintenance support services for the Presidio of Monterey and the Naval Postgraduate School, including streets, parks, and building maintenance. Additional support services include traffic engineering, inspections, construction engineering and project management. This innovative partnership has become known as the "Monterey Model" and is now being adopted by communities across the country. This service reduces maintenance costs by millions of dollars and supports a continued military presence in Monterey.

The city government's Recreation and Community Services department runs the Monterey Sports Center.

Monterey is governed by a mayor and four city council members. As of December 2021, the mayor is Tyller Williamson and the city council members are Kim Barber, Gino Garcia, Alan Haffa, and Ed Smith.

The City of Monterey provides base maintenance support services for the Presidio of Monterey and the Naval Postgraduate School, including streets, parks, and building maintenance. Additional support services include traffic engineering, inspections, construction engineering and project management. This innovative partnership has become known as the "Monterey Model" and is now being adopted by communities across the country. This service reduces maintenance costs by millions of dollars and supports a continued military presence in Monterey.

The city government's Recreation and Community Services department runs the Monterey Sports Center.

The city is serviced by California State Route 1, CA 1, also known as the Cabrillo Highway, as it runs along the coastline of the rest of

The city is serviced by California State Route 1, CA 1, also known as the Cabrillo Highway, as it runs along the coastline of the rest of

Several institutions of higher education in the area: the

Several institutions of higher education in the area: the

''California State Waters Map Series—Offshore of Monterey, California,''

U.S. Geological Survey (2015) * ''City of Monterey Parks and Recreation Master Plan'', City of Monterey Parks and Recreation Department (1986) * * * ''Environmental Hazards Element, city of Monterey'', A part of the General Plan, February 1977 * ''Flora and Fauna Resources: City of Monterey General Plan Technical Study'', prepared for City of Monterey by Bainbridge Behrens Moore Inc., November 2, 1977 * ''General Plan, the City of Monterey'', (1980) * Helen Spangenberg, ''Yesterday's Artists of the Monterey Peninsula, Monterey museum of Art'' (1976) * ''Prehistoric Sources Technical Study'', prepared for the city of Monterey by Bainbridge Behrens Moore Inc., May 23, 1977

Monterey Bay

Monterey Bay is a bay of the Pacific Ocean located on the coast of the U.S. state of California, south of the San Francisco Bay Area. San Francisco itself is further north along the coast, by about 75 miles (120 km), accessible via California S ...

, on the Central Coast of California

The Central Coast is an area of California, roughly spanning the coastal region between Point Mugu and Monterey Bay. It lies northwest of Los Angeles and south of the San Francisco Bay Area, and includes the rugged, rural, and sparsely populat ...

. Located in Monterey County

Monterey County ( ), officially the County of Monterey, is a county located on the Pacific coast in the U.S. state of California. As of the 2020 United States census, its population was 439,035. The county's largest city and county seat is ...

, the city occupies a land area of and recorded a population of 30,218 in the 2020 census.

The city was founded by the Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many countries in the Americas

**Spanish cuisine

**Spanish history

**Spanish culture

...

in 1770, when Gaspar de Portolá

Captain Gaspar de Portolá y Rovira (January 1, 1716 – October 10, 1786) was a Spanish Army officer and colonial administrator who served as the first List of governors of California before 1850, governor of the Californias from 1767 to 1770 ...

and Junípero Serra

Saint Junípero Serra Ferrer (; ; November 24, 1713August 28, 1784), popularly known simply as Junipero Serra, was a Spanish Roman Catholic, Catholic priest and missionary of the Franciscan Order. He is credited with establishing the Francis ...

established the Presidio of Monterey

The Presidio of Monterey (POM), located in Monterey, California, is an active US Army installation with historic ties to the Spanish colonial era. Currently, it is the home of the Defense Language Institute Foreign Language Center (DLI-FLC). ...

and the Cathedral of San Carlos Borromeo. Monterey was elevated to capital of the Province of the Californias

The Province of Las Californias () was a Spanish Empire province in the northwestern region of New Spain. Its territory consisted of the entire U.S. states of California, Nevada, and Utah, parts of Arizona, Wyoming, and Colorado, and the Mexican s ...

in 1777, servings as the administrative and military headquarters of both Alta California

Alta California (, ), also known as Nueva California () among other names, was a province of New Spain formally established in 1804. Along with the Baja California peninsula, it had previously comprised the province of , but was made a separat ...

and Baja California

Baja California, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Baja California, is a state in Mexico. It is the northwesternmost of the 32 federal entities of Mexico. Before becoming a state in 1952, the area was known as the North Territory of B ...

, as well as its only official port of entry

In general, a port of entry (POE) is a place where one may lawfully enter a country. It typically has border control, border security staff and facilities to check passports and visas and to inspect luggage to assure that contraband is not impo ...

. Following the Mexican War of Independence

The Mexican War of Independence (, 16 September 1810 – 27 September 1821) was an armed conflict and political process resulting in Mexico's independence from the Spanish Empire. It was not a single, coherent event, but local and regional ...

, Monterey continued as the capital of the Mexican Department of the Californias

The Californias (), occasionally known as the Three Californias or the Two Californias, are a region of North America spanning the United States and Mexico, consisting of the U.S. state of California and the Mexican states of Baja California an ...

.

During the United States conquest of California, part of the Mexican-American War

Mexican Americans are Americans of full or partial Mexican descent. In 2022, Mexican Americans comprised 11.2% of the US population and 58.9% of all Hispanic and Latino Americans. In 2019, 71% of Mexican Americans were born in the United State ...

, Monterey was seized by the American military in the Battle of Monterey

The Battle of Monterey, at Monterey, California, occurred on 7 July 1846, during the Mexican–American War. The United States captured the town unopposed.

Prelude

In February 1845, at the Battle of Providencia, the Californio forces had ouste ...

in 1846. Following its capture, Monterey continued to serve as the capital of the American interim government of California

The interim government of California existed from soon after the outbreak of the Mexican–American War in mid-1846 until U.S. statehood in September, 1850. There were three distinct phases:

*The first phase was from the beginning of the wartime m ...

until 1849, during which it hosted the California's 1st Constitutional Convention. In the late 19th century, Monterey and its surrounding area began to attract communities of artists, writers, and other creatives, leading to the creation of an art colony

Art colonies are organic congregations of artists in towns, villages and rural areas, who are often drawn to areas of natural beauty, the prior existence of other artists, art schools there, or a lower cost of living. They are typically mission ...

.

Today, Monterey is a popular tourist destination on the Central Coast, hosting notable attractions such as the Monterey Bay Aquarium

Monterey Bay Aquarium is a Nonprofit organization, nonprofit public aquarium in Monterey, California. Known for its regional focus on the marine habitats of Monterey Bay, it was the first to exhibit a living kelp forest when it opened in Octob ...

, Cannery Row

Cannery Row is a historic waterfront street in Monterey, California, once home to a thriving sardine canning industry. Originally named Ocean View Avenue, it was nicknamed 'Cannery Row' as early as 1918 and officially renamed in 1958. The area ...

, Fisherman's Wharf, California Roots Music and Arts Festival, and the annual Monterey Jazz Festival

The Monterey Jazz Festival is an annual music festival that takes place in Monterey, California, United States. It debuted on October 3, 1958, championed by Dave Brubeck and co-founded by jazz and popular music critic Ralph J. Gleason and jazz ...

. The city is also an important hub for the military and higher education, home to the Defense Language Institute

The Defense Language Institute (DLI) is a United States Department of Defense (DoD) educational and research institution consisting of two separate entities which provide linguistic and cultural instruction to the Department of Defense, other f ...

, the Naval Postgraduate School

Naval Postgraduate School (NPS) is a Naval command with a graduate university mission, operated by the United States Navy and located in Monterey, California.

The NPS mission is to provide "defense-focused graduate education, including clas ...

, the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey

Established in 1955, the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey (MIIS), formerly the Monterey Institute of International Studies, located in Monterey, California, is a Postgraduate education, graduate institute and satellite ...

and California State University, Monterey Bay

California State University, Monterey Bay (CSUMB or Cal State Monterey Bay) is a public university located in Monterey County, California, United States. The main campus is situated on the site of the former military base Fort Ord, spanning the ...

.

History

Ohlone period

Long before the arrival of Spanish explorers, the Rumsen

Long before the arrival of Spanish explorers, the Rumsen Ohlone

The Ohlone ( ), formerly known as Costanoans (from Spanish meaning 'coast dweller'), are a Native Americans in the United States, Native American people of the Northern California coast. When Spanish explorers and missionaries arrived in the l ...

tribe, one of seven linguistically distinct Ohlone groups in California, inhabited the area now known as Monterey. Ohlone villages

The Ohlone ( ), formerly known as Costanoans (from Spanish meaning 'coast dweller'), are a Native Americans in the United States, Native American people of the Northern California coast. When Spanish explorers and missionaries arrived in the l ...

in the area included Ichxenta (Point Lobos

Point Lobos and the Point Lobos State Natural Reserve is a state park in California. Adjoining Point Lobos is "one of the richest marine habitats in California". The ocean habitat is protected by two marine protected areas, the Point Lobos Sta ...

), Calendaruc, Wacharon (Moss Landing

Moss Landing, formerly Moss, is an unincorporated community and census-designated place (CDP) in Monterey County, California, United States. It is located north-northeast of Monterey, at an elevation of . It is on the shore of Monterey Bay, at t ...

), and Rumsien (Carmel-by-the-Sea

Carmel-by-the-Sea (), commonly known simply as Carmel, is a city in Monterey County, California, located on the Central Coast of California. As of the 2020 census, the city had a population of 3,220, down from 3,722 at the 2010 census. Situa ...

), among others. They subsisted by hunting, fishing and gathering food on and around the biologically rich Monterey Peninsula

The Monterey Peninsula anchors the northern portion on the Central Coast (California), Central Coast of California and comprises the cities of Monterey, California, Monterey, Carmel-by-the-Sea, California, Carmel, and Pacific Grove, California, P ...

.

Researchers have found a number of shell midden

A midden is an old dump for domestic waste. It may consist of animal bones, human excrement, botanical material, mollusc shells, potsherds, lithics (especially debitage), and other artifacts and ecofacts associated with past human oc ...

s in the area and, based on the archaeological evidence, concluded the Ohlone's primary marine food consisted of various types of mussel

Mussel () is the common name used for members of several families of bivalve molluscs, from saltwater and Freshwater bivalve, freshwater habitats. These groups have in common a shell whose outline is elongated and asymmetrical compared with other ...

s and abalone

Abalone ( or ; via Spanish , from Rumsen language, Rumsen ''aulón'') is a common name for any small to very large marine life, marine gastropod mollusc in the family (biology), family Haliotidae, which once contained six genera but now cont ...

. A number of midden sites have been located along about of rocky coast on the Monterey Peninsula from the current site of Fishermans' Wharf in Monterey to Carmel.

Spanish period

The city is named afterMonterey Bay

Monterey Bay is a bay of the Pacific Ocean located on the coast of the U.S. state of California, south of the San Francisco Bay Area. San Francisco itself is further north along the coast, by about 75 miles (120 km), accessible via California S ...

. The bay's name was given by Sebastián Vizcaíno

Sebastián Vizcaíno (c. 1548–1624) was a Spanish soldier, entrepreneur, explorer, and diplomat whose varied roles took him to New Spain, the Baja California peninsula, the California coast and Asia.

Early career

Vizcaíno was born in ...

in 1602. He anchored in what is now Monterey harbor on December 16, and named it ''Puerto de Monterrey'', in honor of the Conde de Monterrey, then the viceroy of New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( ; Nahuatl: ''Yankwik Kaxtillan Birreiyotl''), originally the Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain. It was one of several ...

. Monterrey is an alternate spelling of Monterrei

Monterrei, historically spelled Monterrey in Spanish and English, is a municipality in the province of Ourense, in the autonomous community of Galicia, Spain. It belongs to the comarca of Verín.

Monterrei is well known for its castle, built i ...

, a municipality in the Galicia region of Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

from which the viceroy and his father (the Fourth Count of Monterrei) originated. Some variants of the city's name are recorded as Monte Rey and Monterey. Monterey Bay had been described earlier by Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo

Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo (; 1497 – January 3, 1543) was a Portuguese maritime explorer best known for investigations of the west coast of North America, undertaken on behalf of the Spanish Empire. He was the first European to explore presen ...

as La Bahia de los Pinos (Bay of the Pines). Despite the explorations of Cabrillo and Vizcaino, and despite Spain's frequent trading voyages between Asia and Mexico, the Spanish did not make Monterey Bay into a settled permanent harbor before the 18th century because it was too exposed to rough ocean currents and winds.

Despite Monterey's limited use as a maritime port, the encroachments of other Europeans near California in the 18th century prompted the Spanish monarchy to try to better secure the region. As a result, it commissioned the Portola exploration and Alta California mission system. In 1769, the first European land exploration of Alta California

Alta California (, ), also known as Nueva California () among other names, was a province of New Spain formally established in 1804. Along with the Baja California peninsula, it had previously comprised the province of , but was made a separat ...

, the Spanish Portolá expedition

thumbnail, 250px, Point of San Francisco Bay Discovery

The Portolá expedition was a Spanish voyage of exploration in 1769–1770 that was the first recorded European exploration of the interior of the present-day California. It was led by Gas ...

, traveled north from San Diego

San Diego ( , ) is a city on the Pacific coast of Southern California, adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a population of over 1.4 million, it is the List of United States cities by population, eighth-most populous city in t ...

. They sought Vizcaíno's Port of Monterey, which he had described as "a fine harbor sheltered from all winds" 167 years earlier. The explorers failed to recognize the place when they came to it on October 1, 1769. The party continued north as far as San Francisco Bay

San Francisco Bay (Chochenyo language, Chochenyo: 'ommu) is a large tidal estuary in the United States, U.S. state of California, and gives its name to the San Francisco Bay Area. It is dominated by the cities of San Francisco, California, San ...

before turning back. On the return journey, they camped near one of Monterey's lagoons on November 27, still not convinced they had found the place Vizcaíno had described. Franciscan

The Franciscans are a group of related organizations in the Catholic Church, founded or inspired by the Italian saint Francis of Assisi. They include three independent Religious institute, religious orders for men (the Order of Friars Minor bei ...

missionary Juan Crespí

Juan Crespí, OFM (Catalan language, Catalan: ''Joan Crespí''; 1 March 1721 – 1 January 1782) was a Franciscan missionary and explorer of The Californias, Las Californias.

Biography

A native of Majorca, Crespí entered the Franciscan ord ...

noted in his diary, "We halted in sight of the Point of Pines (recognized, as was said, in the beginning of October) and camped near a small lagoon which has rather muddy water, but abounds in pasture and firewood."

Gaspar de Portolá

Captain Gaspar de Portolá y Rovira (January 1, 1716 – October 10, 1786) was a Spanish Army officer and colonial administrator who served as the first List of governors of California before 1850, governor of the Californias from 1767 to 1770 ...

returned by land to Monterey the next year, having concluded that he must have been at Vizcaíno's Port of Monterey after all. The land party was met at Monterey by Junípero Serra

Saint Junípero Serra Ferrer (; ; November 24, 1713August 28, 1784), popularly known simply as Junipero Serra, was a Spanish Roman Catholic, Catholic priest and missionary of the Franciscan Order. He is credited with establishing the Francis ...

, who traveled by sea. Portolá erected the Presidio of Monterey

The Presidio of Monterey (POM), located in Monterey, California, is an active US Army installation with historic ties to the Spanish colonial era. Currently, it is the home of the Defense Language Institute Foreign Language Center (DLI-FLC). ...

to defend the port and, on June 3, 1770, Serra founded the Cathedral of San Carlos Borromeo inside the presidio enclosure. Portolá returned to Mexico, replaced in Monterey by Captain Pedro Fages

Pedro Fages (1734–1794) was a Spanish soldier, explorer, and first lieutenant governor of the province of the Californias under Gaspar de Portolá. Fages claimed the governorship after Portolá's departure, acting as governor in opposition ...

, who had been third in command on the exploratory expeditions. Fages became the second governor of Alta California, serving from 1770 to 1774.

Serra's missionary aims soon came into conflict with Fages and the soldiers, so he relocated and built a new mission in Carmel

Carmel may refer to:

* Carmel (biblical settlement), an ancient Israelite town in Judea

* Mount Carmel, a coastal mountain range in Israel overlooking the Mediterranean Sea

* Carmelites, a Roman Catholic mendicant religious order

Carmel may also ...

the next year to gain greater independence from Fages. The existing wood and adobe

Adobe (from arabic: الطوب Attub ; ) is a building material made from earth and organic materials. is Spanish for mudbrick. In some English-speaking regions of Spanish heritage, such as the Southwestern United States, the term is use ...

church remained in service to the nearby soldiers and became the Royal Presidio Chapel.

Monterey became the capital of the "Province of Both Californias" in 1777, and the chapel was renamed the Royal Presidio Chapel. The original church was destroyed by fire in 1789 and replaced by the present sandstone

Sandstone is a Clastic rock#Sedimentary clastic rocks, clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of grain size, sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate mineral, silicate grains, Cementation (geology), cemented together by another mineral. Sand ...

structure. It was completed in 1794 by Indian labor. In 1840, the chapel was rededicated to the patronage of Saint Charles Borromeo

Charles Borromeo (; ; 2 October 1538 – 3 November 1584) was an Italian Catholic prelate who served as Archbishop of Milan from 1564 to 1584. He was made a cardinal in 1560.

Borromeo founded the Confraternity of Christian Doctrine and was a ...

. The cathedral is the oldest continuously operating parish and the oldest stone building in California. It is also the oldest (and smallest) serving cathedral along with St. Louis Cathedral in New Orleans, Louisiana

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

. It is the only existing presidio chapel in California and the only surviving building from the original Monterey Presidio.

The city was originally the only port of entry for all taxable goods in California. All shipments into California by sea were required to go through the Custom House

A custom house or customs house was traditionally a building housing the offices for a jurisdictional government whose officials oversaw the functions associated with importing and exporting goods into and out of a country, such as collecting ...

, the oldest governmental building in the state and California's Historic Landmark Number One. Built in three phases, the Spanish began construction of the Custom House in 1814, the Mexican government completed the center section in 1827, and the United States government finished the lower end in 1846.

Argentine raid and occupation

On November 24, 1818,Argentine

Argentines, Argentinians or Argentineans are people from Argentina. This connection may be residential, legal, historical, or cultural. For most Argentines, several (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of their ...

corsair Hippolyte Bouchard

Hippolyte or Hipólito Bouchard (15 January 1780 – 4 January 1837), known in California as Pirata Buchar, was a French-born Argentine sailor and corsair (pirate) who fought for Argentina, Chile, and Peru.

During his first campaign as an Arge ...

landed approximately from the Presidio of Monterey

The Presidio of Monterey (POM), located in Monterey, California, is an active US Army installation with historic ties to the Spanish colonial era. Currently, it is the home of the Defense Language Institute Foreign Language Center (DLI-FLC). ...

, using a hidden tidal creek

A tidal creek or tidal channel is a narrow inlet or estuary that is affected by the ebb and flow of ocean tides. Thus, it has variable salinity and electrical conductivity over the tidal cycle, and flushes salts from inland soils. Tidal creeks a ...

to conceal his approach. Operating under a letter of marque from the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata

The United Provinces of the Río de la Plata (), earlier known as the United Provinces of South America (), was a name adopted in 1816 by the Congress of Tucumán for the region of South America that declared independence in 1816, with the Sove ...

, Bouchard carried out the expedition as part of Argentina’s broader efforts to disrupt Spanish colonial control during the South American wars of independence.

The Spanish garrison offered minimal resistance, and after roughly an hour of combat, Bouchard’s forces succeeded in capturing the fort. The Argentine flag was then raised over Monterey, marking a symbolic assertion of Argentine presence on the Pacific coast of North America. Although the Spanish flag had long flown there as part of colonial rule, this event marked the first time an independent foreign nation had occupied and hoisted its flag in California preceding both the Mexican

Mexican may refer to:

Mexico and its culture

*Being related to, from, or connected to the country of Mexico, in North America

** People

*** Mexicans, inhabitants of the country Mexico and their descendants

*** Mexica, ancient indigenous people ...

and United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

flags.

Bouchard’s forces occupied Monterey for six days. During the occupation, they seized livestock and supplies, and set fire to several strategic buildings, including the fort, the artillery headquarters, the governor’s residence, and various Spanish colonial homes. Despite the destruction of infrastructure, the civilian population was not harmed. After achieving their objectives, the Argentines withdrew and continued their privateering campaign along the Pacific coast.

Mexican period

Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821, but the civil and religious institutions of Alta California remained much the same until the 1830s, when the

Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821, but the civil and religious institutions of Alta California remained much the same until the 1830s, when the secularization

In sociology, secularization () is a multilayered concept that generally denotes "a transition from a religious to a more worldly level." There are many types of secularization and most do not lead to atheism or irreligion, nor are they automatica ...

of the missions converted most of the mission pasture lands into private land grant ranchos. In 1834, the San Carlos Cemetery was officially opened and interred

Burial, also known as interment or inhumation, is a method of final disposition whereby a dead body is placed into the ground, sometimes with objects. This is usually accomplished by excavating a pit or trench, placing the deceased and object ...

many of the early local families. Agustín V. Zamorano established the first print shop in California, when he brought a printing press

A printing press is a mechanical device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a printing, print medium (such as paper or cloth), thereby transferring the ink. It marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in whi ...

to Monterey, in the summer of 1834.

During the Mexican period, the city was determined the site of District Court of the Territory of Alta California (''Juzgado de Distrito del Territorio de la Alta California''), since 1834, when Luis del Castillo Negrete, the appointed district judge (Juez de Distrito), took possession of the court; until 1836, when due to the rebellion led by Juan Bautista Alvarado

Juan Bautista Valentín Alvarado y Vallejo (February 14, 1809 – July 13, 1882) usually known as Juan Bautista Alvarado, was a Californio politician that served as governor of Alta California from 1837 to 1842. Prior to his term as governor, Al ...

, the judge left the city for the territory of Baja California, which ''de facto'' disqualified that instance and would close definitively until 1841, with a decree by Antonio López de Santa Anna

Antonio de Padua María Severino López de Santa Anna y Pérez de Lebrón (21 February 1794 – 21 June 1876),Callcott, Wilfred H., "Santa Anna, Antonio Lopez De,''Handbook of Texas Online'' Retrieved 18 April 2017. often known as Santa Anna, wa ...

. Subsequently, in 1842, the Superior Court (''Superior Tribunal de Justicia del Departamento de las Californias'') was installed, which had a short life, as it stopped functioning in 1845.

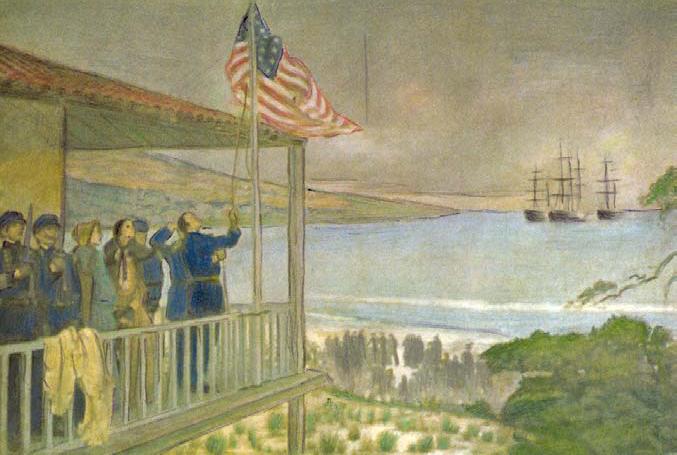

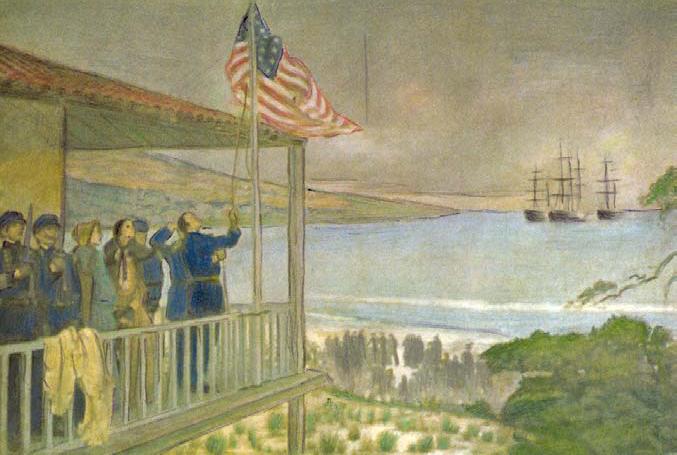

Monterey was the site of the Battle of Monterey

The Battle of Monterey, at Monterey, California, occurred on 7 July 1846, during the Mexican–American War. The United States captured the town unopposed.

Prelude

In February 1845, at the Battle of Providencia, the Californio forces had ouste ...

on July 7, 1846, during the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War (Spanish language, Spanish: ''guerra de Estados Unidos-México, guerra mexicano-estadounidense''), also known in the United States as the Mexican War, and in Mexico as the United States intervention in Mexico, ...

. It was on this date that John D. Sloat, Commodore in the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

, raised the U.S. flag

The national flag of the United States, often referred to as the American flag or the U.S. flag, consists of thirteen horizontal stripes, alternating red and white, with a blue rectangle in the canton bearing fifty small, white, five-point ...

over the Monterey Custom House and claimed California for the United States.

In addition, many historic "firsts" occurred in Monterey. These include First theater in California, brick house, publicly funded school, public building, public library, and printing press (which printed ''The Californian'', California's first newspaper.) Larkin House, one of Monterey State Historic Park

Monterey State Historic Park is a historic state park in Monterey, California. It includes part or all of the Monterey Old Town Historic District, a historic district (United States), historic district that includes 17 contributing buildings and ...

's National Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark (NHL) is a National Register of Historic Places property types, building, district, object, site, or structure that is officially recognized by the Federal government of the United States, United States government f ...

s, built in the Mexican period by Thomas Oliver Larkin, is an early example of Monterey Colonial architecture. The Old Custom House, the historic district and the Royal Presidio Chapel are also National Historic Landmarks. The Cooper-Molera Adobe is a National Trust

The National Trust () is a heritage and nature conservation charity and membership organisation in England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

The Trust was founded in 1895 by Octavia Hill, Sir Robert Hunter and Hardwicke Rawnsley to "promote the ...

Historic Site.

American period

Colton Hall

Colton Hall is a government building and museum in Monterey, California, United States. It was built in 1847–49 by Walter Colton, who arrived in Monterey as the chaplain on Commodore Robert F. Stockton's vessel. He remained and was named as ...

, built in 1849 by Walter Colton

Reverend Walter Colton (May 7, 1797 – January 22, 1851) was an American clergyman and writer from Vermont who served as the first American Alcalde (mayor) of Monterey, California. He worked as an editor for newspapers in Washington, D.C., and P ...

, originally served as both a public school and a government meeting place. It hosted the 1849 Constitutional Convention, where American and Californio

Californios (singular Californio) are Californians of Spaniards, Spanish descent, especially those descended from settlers of the 17th through 19th centuries before California was annexed by the United States. California's Spanish language in C ...

delegates drafted the first Constitution of California

The Constitution of California () is the primary organizing law for the U.S. state of California, describing the duties, powers, structures and functions of the government of California. California's constitution was drafted in both English ...

, in both English and Spanish.

Monterey hosted California's first constitutional convention in 1849, which composed the documents necessary to apply to the United States for statehood

A state is a political entity that regulates society and the population within a definite territory. Government is considered to form the fundamental apparatus of contemporary states.

A country often has a single state, with various administrat ...

. Today Colton Hall houses a small museum, while adjacent buildings serve as the seat of local government, and the Monterey post office (opened in 1849).

Pioneer Francis Doud built Doud House in the 1860s, situated at the present-day 117 Van Buren Street. The house is one of the earliest and most well-preserved examples of an early wood frame residences in Monterey. Monterey was incorporated in 1890.

Thomas Albert Work built several of the buildings in Monterey, including the three-story Del Mar hotel in 1895, at the corner of Sixteenth, and in 1900, bought into the First National Bank in Monterey, acquiring it in 1906. He was president of the bank for more than 20 years.

Monterey had long been famous for the abundant fishery in Monterey Bay. That changed in the 1950s when the local fishery business collapsed due to overfishing

Overfishing is the removal of a species of fish (i.e. fishing) from a body of water at a rate greater than that the species can replenish its population naturally (i.e. the overexploitation of the fishery's existing Fish stocks, fish stock), resu ...

. A few of the old fishermen's cabins from the early 20th century have been preserved as they originally stood along Cannery Row

Cannery Row is a historic waterfront street in Monterey, California, once home to a thriving sardine canning industry. Originally named Ocean View Avenue, it was nicknamed 'Cannery Row' as early as 1918 and officially renamed in 1958. The area ...

.

The city has a noteworthy history as a center for California painters in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Such painters as Arthur Frank Mathews

Arthur F. Mathews (October 1, 1860 – February 19, 1945) was an American tonalism, Tonalist painter who was one of the founders of the American Arts and Crafts Movement. Trained as an architect and artist, he and his wife Lucia Kleinhans Mathews ...

, Armin Hansen, Xavier Martinez

Xavier or Xabier may refer to:

Place

* Xavier, Spain

People

* Xavier (surname)

* Xavier (given name)

* Francis Xavier (1506–1552), Catholic saint

** St. Francis Xavier (disambiguation)

* St. Xavier (disambiguation)

* Xavier (footballer, born ...

, Rowena Meeks Abdy and Percy Gray lived or visited to pursue painting in the style of either En plein air

''En plein air'' (; French language, French for 'outdoors'), or plein-air painting, is the act of painting outdoors.

This method contrasts with studio painting or academic rules that might create a predetermined look. The theory of 'En plein ai ...

or Tonalism

Tonalism was an artistic style that emerged in the 1880s when Visual art of the United States, American artists began to paint landscape forms with an overall tone of colored atmosphere or mist. Between 1880 and 1915, dark, neutral hues such as g ...

.

Many noted authors have also lived in and around Monterey, including Robert Louis Stevenson

Robert Louis Stevenson (born Robert Lewis Balfour Stevenson; 13 November 1850 – 3 December 1894) was a Scottish novelist, essayist, poet and travel writer. He is best known for works such as ''Treasure Island'', ''Strange Case of Dr Jekyll ...

, John Steinbeck

John Ernst Steinbeck ( ; February 27, 1902 – December 20, 1968) was an American writer. He won the 1962 Nobel Prize in Literature "for his realistic and imaginative writings, combining as they do sympathetic humor and keen social percep ...

, Ed Ricketts

Edward Flanders Robb Ricketts (May 14, 1897 – May 11, 1948) was an American marine biologist, ecologist, and philosopher. Renowned as the inspiration for the character Doc in John Steinbeck's 1945 novel '' Cannery Row'', Rickett's professional ...

, Robinson Jeffers

John Robinson Jeffers (January 10, 1887 – January 20, 1962) was an American poet known for his work about the central California coast.

Much of Jeffers' poetry was written in narrative and Epic poetry, epic form. However, he is also known f ...

, Robert A. Heinlein

Robert Anson Heinlein ( ; July 7, 1907 – May 8, 1988) was an American science fiction author, aeronautical engineer, and naval officer. Sometimes called the "dean of science fiction writers", he was among the first to emphasize scientific acc ...

, and Henry Miller

Henry Valentine Miller (December 26, 1891 – June 7, 1980) was an American novelist, short story writer and essayist. He broke with existing literary forms and developed a new type of semi-autobiographical novel that blended character study, so ...

.

More recently, Monterey has been recognized for its significant involvement in post-secondary learning of languages other than English and its major role in delivering translation and interpretation services around the world. In November 1995, California Governor Pete Wilson

Peter Barton Wilson (born August 23, 1933) is an American attorney and politician who served as governor of California from 1991 to 1999. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, Wilson previously served as a United S ...

proclaimed Monterey "the Language Capital of the World".

On June 7, 2021, the macOS Monterey

macOS Monterey (version 12) is the eighteenth major release of macOS, Apple's desktop operating system for Macintosh computers. The successor to macOS Big Sur, it was announced at WWDC 2021 on June 7, 2021, and released on October 25, 2021. ...

operating system was presented at Apple's Worldwide Developers Conference

The Worldwide Developers Conference (WWDC) is an information technology conference held annually by Apple Inc. The conference is currently held at Apple Park in California. The event is used to showcase new software and technologies in the macO ...

(WWDC2021) and named after the Monterey region.

Geography

According to theUnited States Census Bureau

The United States Census Bureau, officially the Bureau of the Census, is a principal agency of the Federal statistical system, U.S. federal statistical system, responsible for producing data about the American people and American economy, econ ...

, the city has an area of , of which is land and (28.05%) is water. Sand deposits in the northern coastal area comprise the sole known mineral resources. The city has several distinct districts, such as New Monterey, Del Monte, and Cannery Row

Cannery Row is a historic waterfront street in Monterey, California, once home to a thriving sardine canning industry. Originally named Ocean View Avenue, it was nicknamed 'Cannery Row' as early as 1918 and officially renamed in 1958. The area ...

.

Local soil is Quaternary

The Quaternary ( ) is the current and most recent of the three periods of the Cenozoic Era in the geologic time scale of the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS), as well as the current and most recent of the twelve periods of the ...

Alluvium

Alluvium (, ) is loose clay, silt, sand, or gravel that has been deposited by running water in a stream bed, on a floodplain, in an alluvial fan or beach, or in similar settings. Alluvium is also sometimes called alluvial deposit. Alluvium is ...

. Common soil series include the Baywood fine sand on the east side, Narlon loamy sand on the west side, Sheridan coarse sandy loam on hilly terrain, and the pale Tangair sand on hills supporting closed-cone pine habitat. The city is in a moderate to high seismic risk zone, the principal threat being the active San Andreas Fault

The San Andreas Fault is a continental Fault (geology)#Strike-slip faults, right-lateral strike-slip transform fault that extends roughly through the U.S. state of California. It forms part of the tectonics, tectonic boundary between the Paci ...

approximately to the east. The Monterey Bay fault, which tracks to the north, is also active, as is the Palo Colorado fault to the south. Also nearby, minor but potentially active, are the Berwick Canyon, Seaside, Tularcitos and Chupines faults.

Monterey Bay's maximum credible tsunami

A tsunami ( ; from , ) is a series of waves in a water body caused by the displacement of a large volume of water, generally in an ocean or a large lake. Earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and underwater explosions (including detonations, ...

for a 100-year interval has been calculated as a wave high. The considerable undeveloped area in the northwest part of the city has a high potential for landslides and erosion.

The city is adjacent to the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary

Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary (MBNMS) is a federally protected marine area offshore of California's Big Sur and central coast in the United States. It is one of the largest US national marine sanctuaries and has a shoreline length ...

, a federally protected ocean area extending along the coast. Sometimes this sanctuary is confused with the local bay which is also termed Monterey Bay.

Soquel Canyon State Marine Conservation Area

Soquel Canyon State Marine Conservation Area (SMCA) is an offshore marine protected area in Monterey Bay. Monterey Bay is on California’s central coast with the city of Monterey at its south end and the city of Santa Cruz at its north end. T ...

, Portuguese Ledge State Marine Conservation Area

Portuguese Ledge State Marine Conservation Area (SMCA) is an offshore marine protected area in Monterey Bay. Monterey Bay is on California's central coast with the city of Monterey at its south end and the city of Santa Cruz at its north end. Th ...

, Pacific Grove Marine Gardens State Marine Conservation Area, Lovers Point State Marine Reserve, Edward F. Ricketts State Marine Conservation Area

Edward F. Ricketts State Marine Conservation Area is one of four small marine protected areas located near the cities of Monterey and Pacific Grove, California, Pacific Grove, at the southern end of Monterey Bay on California’s central coast. ...

and Asilomar State Marine Reserve are marine protected area

A marine protected area (MPA) is a protected area of the world's seas, oceans, estuaries or in the US, the Great Lakes. These marine areas can come in many forms ranging from wildlife refuges to research facilities. MPAs restrict human activity ...

s established by the state of California in Monterey Bay. Like underwater parks, these marine protected areas help conserve ocean wildlife and marine ecosystems.

The California sea otter

The sea otter (''Enhydra lutris'') is a marine mammal native to the coasts of the northern and eastern Pacific Ocean, North Pacific Ocean. Adult sea otters typically weigh between , making them the heaviest members of ...

, a threatened subspecies, inhabits the local Monterey Bay marine environment, and a field station of The Marine Mammal Center

The Marine Mammal Center (TMMC) is a private, non-profit United States, U.S. organization that was established in 1975 for the purpose of rescuing, rehabilitating and releasing marine mammals who are injured, sick or abandoned. It was founded in S ...

is located in Monterey to support sea rescue operations in this section of the California coast. The rare San Joaquin kit fox

The kit fox (''Vulpes macrotis'') is a fox species that inhabits arid and semi-arid regions of the southwestern United States and northern and central Mexico. These foxes are the smallest of the four species of ''Vulpes'' occurring in North Amer ...

is found in Monterey's oak-forest and chaparral

Chaparral ( ) is a shrubland plant plant community, community found primarily in California, southern Oregon, and northern Baja California. It is shaped by a Mediterranean climate (mild wet winters and hot dry summers) and infrequent, high-intens ...

habitats. The chaparral, found mainly on the city's drier eastern slopes, hosts such plants as manzanita

Manzanita is a common name for many species of the genus '' Arctostaphylos''. They are evergreen shrubs or small trees present in the chaparral biome of western North America, where they occur from Southern British Columbia and Washington to O ...

, chamise

''Adenostoma fasciculatum'', commonly known as chamise or greasewood, is a flowering plant native to California and Baja California. This shrub is one of the most widespread plants of the California chaparral ecoregion. Chamise produces a specia ...

and ceanothus

''Ceanothus'' is a genus of about 50–60 species of nitrogen-fixing shrubs and small trees in the buckthorn family (Rhamnaceae). Common names for members of this genus are buckbrush, California lilac, soap bush, or just ceanothus. ''"Ceanothus" ...

. Additional species of interest (that is, potential candidates for endangered species status) are the Salinas kangaroo rat

Kangaroo rats, small mostly nocturnal rodents of genus ''Dipodomys'', are native to arid areas of western North America. The common name derives from their bipedal form. They hop in a manner similar to the much larger kangaroo, but developed thi ...

and the silver-sided legless lizard.

There is a variety of natural habitat in Monterey: littoral zone and sand dunes; closed-cone pine forest; and Monterey Cypress

''Hesperocyparis macrocarpa'' also known as ''Cupressus macrocarpa'', or the Monterey cypress is a coniferous tree, and is one of several species of cypress trees native to California.

The Monterey cypress is found naturally only on the Centr ...

. There are no dairy farms in the city of Monterey; the semi-hard cheese known as Monterey Jack

Monterey Jack, sometimes shortened to Jack, is a Californian white, semi-hard cheese made using cow's milk, with a mild flavor and slight sweetness. Originating in Monterey, on the Central Coast of California, the cheese has been called "a vest ...

originated in nearby Carmel Valley, California

Carmel Valley is an Unincorporated area#United States, unincorporated community in Monterey County, California, United States. The term "Carmel Valley" generally refers to the Carmel River (California), Carmel River watershed east of California ...

, and is named after businessman and land speculator David Jacks.

The closed-cone pine habitat is dominated by Monterey pine

''Pinus radiata'' (synonym (taxonomy), syn. ''Pinus insignis''), the Monterey pine, insignis pine or radiata pine, is a species of pine native to the Central Coast (California), Central Coast of California and Mexico (on Guadalupe Island and Ced ...

, Knobcone pine

The knobcone pine, ''Pinus attenuata'' (also called ''Pinus tuberculata''), is a tree that grows in mild climates on poor soils. It ranges from the mountains of southern Oregon to Baja California with the greatest concentration in northern Calif ...

and Bishop pine

''Pinus muricata'', the bishop pine, is a pine with a very restricted range: mostly in California, including several offshore Channel Islands, and a few locations in Baja California, Mexico. Stands of Bishop Pine are also found in Point Reyes Nat ...

, and contains the rare Monterey manzanita. In the early 20th century the botanist Willis Linn Jepson

Willis Linn Jepson (August 19, 1867 – November 7, 1946) was a late-19th and 20th century California botanist, professor, conservationist, and writer. A co-founder of the Sierra Club in 1892, he was much honored in later life for his rese ...

characterized Monterey Peninsula's forests as the "most important silva ever", and encouraged Samuel F.B. Morse (a century younger than the inventor Samuel F. B. Morse) of the Del Monte Properties Company to explore the possibilities of preserving the unique forest communities. The dune area is no less important, as it hosts endangered species such as the vascular plants Seaside birds beak, Hickman's potentilla and Eastwood's Ericameria

''Ericameria'' is a genus of North American shrubs in the family Asteraceae.

''Ericameria'' is known by the common names goldenbush, rabbitbrush, turpentine bush, and rabbitbush. Most are shrubs, but one species ''(Ericameria parishii, E. paris ...

. Rare plants also inhabit the chaparral: Hickman's onion, Yadon's piperia ('' Piperia yadonii'') and Sandmat manzanita. Other rare plants in Monterey include Hutchinson's delphinium

''Delphinium'' is a genus of about 300 species of annual and perennial flowering plants in the family (biology), family Ranunculaceae, native species, native throughout the Northern Hemisphere and also on the high mountains of tropical Africa. T ...

, Tidestrom lupine, Gardner's yampah and Knotweed Knotweed is a common name for plants in several genera in the family Polygonaceae. Knotweed may refer to:

* ''Fallopia''

* ''Persicaria''

* ''Polygonum''

* ''Reynoutria''

** ''Reynoutria japonica'' or Japanese knotweed, a highly invasive species in ...

, the latter perhaps already extinct.

Monterey's noise pollution has been mapped to define the principal sources of noise and to ascertain the areas of the population exposed to significant levels. Principal sources are the

Monterey's noise pollution has been mapped to define the principal sources of noise and to ascertain the areas of the population exposed to significant levels. Principal sources are the Monterey Regional Airport

Monterey Regional Airport is three miles (5 km) southeast of Monterey, California, Monterey, in Monterey County, California, Monterey County, California, United States. It was created in 1936 and was known as the Monterey Peninsula Airpor ...

, State Route 1 and major arterial streets such as Munras Avenue, Fremont Street, Del Monte Boulevard, and Camino Aguajito. While most of Monterey is a quiet residential city, a moderate number of people in the northern part of the city are exposed to aircraft noise at levels in excess of 60 dB on the Community Noise Equivalent Level (CNEL) scale. The most intense source is State Route 1: all residents exposed to levels greater than 65 CNEL—about 1,600 people—live near State Route 1 or one of the principal arterial streets.

Climate

warm-summer Mediterranean climate

A Mediterranean climate ( ), also called a dry summer climate, described by Köppen and Trewartha as ''Cs'', is a temperate climate type that occurs in the lower mid-latitudes (normally 30 to 44 north and south latitude). Such climates typic ...

(Köppen climate classification

The Köppen climate classification divides Earth climates into five main climate groups, with each group being divided based on patterns of seasonal precipitation and temperature. The five main groups are ''A'' (tropical), ''B'' (arid), ''C'' (te ...

: ''Csb'') although with temperatures resembling an oceanic climate

An oceanic climate, also known as a marine climate or maritime climate, is the temperate climate sub-type in Köppen climate classification, Köppen classification represented as ''Cfb'', typical of west coasts in higher middle latitudes of co ...

. The city's average high temperatures range from in December to in September. Average annual precipitation is , with most occurring between October and April; little to no precipitation falls during the summer. There is an average of 72.1 days with measurable precipitation annually. Average temperatures in Monterey are similar to average temperatures found in other parts of the world with oceanic climates, including Puerto Williams

Puerto Williams (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Port Williams") is a city, port and naval base on Navarino Island in Chile. It faces the Beagle Channel. It is the Capital city, capital of Antártica Chilena Province, the Chilean Antarctic Provin ...

, Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in western South America. It is the southernmost country in the world and the closest to Antarctica, stretching along a narrow strip of land between the Andes, Andes Mountains and the Paci ...

, Ushuaia

Ushuaia ( , ) is the capital city, capital of Tierra del Fuego Province, Argentina, Tierra del Fuego, Antártida e Islas del Atlántico Sur Province, Argentina. With a population of 82,615 and a location below the 54th parallel south latitude, U ...

, Argentina

Argentina, officially the Argentine Republic, is a country in the southern half of South America. It covers an area of , making it the List of South American countries by area, second-largest country in South America after Brazil, the fourt ...

, much of New Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

, the Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the Age of Discovery, it was known for se ...

coast of Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

, southeastern Alaska

Southeast Alaska, often abbreviated to southeast or southeastern, and sometimes called the Alaska(n) panhandle, is the southeastern portion of the U.S. state of Alaska, bordered to the east and north by the northern half of the Canadian provin ...

and the western coast of Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard also form part of the Kingdom of ...

.

Summers in Monterey are often cool and foggy. The cold surface waters cause even summer nights to be unusually cool for the latitude; this is in distinct contrast to the much warmer summer days and nights of the U.S. east coast. The extreme moderation of summer temperatures is further underlined by the fact that Monterey is geographically situated at a similar latitude within California as Death Valley

Death Valley is a desert valley in Eastern California, in the northern Mojave Desert, bordering the Great Basin Desert. It is thought to be the Highest temperature recorded on Earth, hottest place on Earth during summer.

Death Valley's Badwat ...

one of the hottest areas in the world.

During winter, snow occasionally falls in the higher elevations of the Santa Lucia Mountains

The Santa Lucia Range (sæntə luˈsiːə) or Santa Lucia Mountains is a rugged mountain range in coastal Central California, running from Carmel southeast for to the Cuyama River in San Luis Obispo County. The range is never more than fro ...

and Gabilan Mountains that overlook Monterey, but snow in Monterey itself is extremely rare. A few unusual events in January 1962, February 1976, and December 1997 brought a light coating of snow to Monterey. In March 2006, a total of fell in Monterey, including on March 10, 2006. The snowfall on January 21, 1962, of , is remembered for delaying the Bing Crosby

Harry Lillis "Bing" Crosby Jr. (May 3, 1903 – October 14, 1977) was an American singer, comedian, entertainer and actor. The first multimedia star, he was one of the most popular and influential musical artists of the 20th century worldwi ...

golf tournament in nearby Pebble Beach

Pebble Beach is an unincorporated community on the Monterey Peninsula in Monterey County, California, United States. The small coastal residential community of mostly single-family homes is also notable as a resort destination, and the home of ...

.

The record lowest temperature was on December 24, 1998, and January 13, 2007. Annually, there are an average of 1.3 days with highs that reach or exceed and an average of 1.5 days with lows at or below the freezing mark.

Combining the records for Monterey and Monterey WFO, the wettest "rain year" on record has been from July 1997 to June 1998 with of precipitation, and the driest from July 2013 to June 2014 with . The most precipitation in one month was in February 1998. The record maximum 24-hour precipitation was on December 11, 2014.

Demographics

The headquarters of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Monterey in California is in Monterey, and one of the relatively few Oratorian communities in the United States is located in the city. The city is adjacent to the historic Catholic Carmel Mission.2020

The 2020 United States census reported that Monterey had a population of 30,218 people, with 12,912 households. The racial makeup of Monterey was 71.9% White, 3.7% African American, 0.9% Native American, 7.3% Asian, 0.3% Pacific Islander, and 7.9% from two or more races. Hispanics or Latinos of any race made up 19.0% of the population. The most commonly reported ancestries wereEnglish

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Culture, language and peoples

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

* ''English'', an Amish ter ...

(14.8%), German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

(14.1%), Irish (13.6%), Mexican

Mexican may refer to:

Mexico and its culture

*Being related to, from, or connected to the country of Mexico, in North America

** People

*** Mexicans, inhabitants of the country Mexico and their descendants

*** Mexica, ancient indigenous people ...

(11.9%), Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, a Romance ethnic group related to or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance languag ...

(8.8%), and Scottish

Scottish usually refers to something of, from, or related to Scotland, including:

*Scottish Gaelic, a Celtic Goidelic language of the Indo-European language family native to Scotland

*Scottish English

*Scottish national identity, the Scottish ide ...

(4.3%).

2010

The 2010 United States Census reported that Monterey had a population of 27,810. The population density was . The racial makeup of Monterey was 21,788 (78.3%)White

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no chroma). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully (or almost fully) reflect and scatter all the visible wa ...

, 777 (2.8%) African American

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from an ...

, 149 (0.5%) Native American, 2,204 (7.9%) Asian, 91 (0.3%) Pacific Islander

Pacific Islanders, Pasifika, Pasefika, Pacificans, or rarely Pacificers are the peoples of the list of islands in the Pacific Ocean, Pacific Islands. As an ethnic group, ethnic/race (human categorization), racial term, it is used to describe th ...

, 1,382 (5.0%) from other races, and 1,419 (5.1%) from two or more races. There were 3,817 people (13.7%) of Hispanic

The term Hispanic () are people, Spanish culture, cultures, or countries related to Spain, the Spanish language, or broadly. In some contexts, Hispanic and Latino Americans, especially within the United States, "Hispanic" is used as an Ethnici ...

or Latino origin, of any race.

The Census reported that 25,307 people (91.0% of the population) lived in households, 2,210 (7.9%) lived in non-institutionalized group quarters, and 293 (1.1%) were institutionalized.

2000

As of the census of 2000, there were 29,674 people, 12,600 households, and 6,476 families residing in the city. The population density was . There were 13,382 housing units at an average density of . The racial makeup of the city was 80.8% White, 10.9% Hispanic, 7.4% Asian, 2.5% African American, 0.6% Native American, 0.3% Pacific Islander, 3.9% from other races, and 4.5% from two or more races.

There were 12,600 households, out of which 21.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 39.5% were married couples living together, 8.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 48.6% were non-families. 37.0% of all households consisted of individuals, and 11.0% had a lone dweller who is over 64. The average household size was 2.13 and the average family size was 2.82.

The age distribution is as follows: 16.6% under the age of 18, 13.1% from 18 to 24, 33.8% from 25 to 44, 21.7% from 45 to 64, and 14.9% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females, there were 96.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 96.1 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $49,109, and the median income for a family was $58,757. Males had a median income of $40,410 versus $31,258 for females. The per capita income for the city was $27,133. About 4.4% of families and 7.8% of the population were below the poverty line, including 6.5% of those under age 18 and 4.8% of those age 65 or over.

As of the census of 2000, there were 29,674 people, 12,600 households, and 6,476 families residing in the city. The population density was . There were 13,382 housing units at an average density of . The racial makeup of the city was 80.8% White, 10.9% Hispanic, 7.4% Asian, 2.5% African American, 0.6% Native American, 0.3% Pacific Islander, 3.9% from other races, and 4.5% from two or more races.

There were 12,600 households, out of which 21.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 39.5% were married couples living together, 8.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 48.6% were non-families. 37.0% of all households consisted of individuals, and 11.0% had a lone dweller who is over 64. The average household size was 2.13 and the average family size was 2.82.

The age distribution is as follows: 16.6% under the age of 18, 13.1% from 18 to 24, 33.8% from 25 to 44, 21.7% from 45 to 64, and 14.9% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females, there were 96.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 96.1 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $49,109, and the median income for a family was $58,757. Males had a median income of $40,410 versus $31,258 for females. The per capita income for the city was $27,133. About 4.4% of families and 7.8% of the population were below the poverty line, including 6.5% of those under age 18 and 4.8% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

According to the city's 2015 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, the top private-sector employers in the city are (in alphabetical order): The top public-sector employers are (in alphabetical order): Other private-sector employers based in Monterey includeMonterey Peninsula Unified School District

Monterey Peninsula Unified School District is a public school district based in Monterey County, California, United States.

The district serves the communities of Monterey, Del Rey Oaks, Sand City, Seaside, almost all of Marina, and a porti ...

, and Mapleton Communications

Mapleton Communications (MC) was a media company. It was formed in May 2001 to acquire and operate radio stations in mid-sized markets in the western United States. Mapleton owned and operated 41 radio stations (11 AM and 30 FM) in California ...

. Additional military facilities in Monterey include the Fleet Numerical Meteorology and Oceanography Center

The Fleet Numerical Meteorology and Oceanography Center (FNMOC) is an echelon IV component of the Naval Meteorology and Oceanography Command (NMOC), which provides worldwide meteorological and oceanographic data and analysis for the United State ...

, and the United States Naval Research Laboratory

The United States Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) is the corporate research laboratory for the United States Navy and the United States Marine Corps. Located in Washington, DC, it was founded in 1923 and conducts basic scientific research, appl ...

– Monterey.

Arts and culture

Attractions

Monterey is well known for the abundance and diversity of its marine life, which includessea lion

Sea lions are pinnipeds characterized by external ear flaps, long foreflippers, the ability to walk on all fours, short and thick hair, and a big chest and belly. Together with the fur seals, they make up the family Otariidae, eared seals. ...

s, sea otter

The sea otter (''Enhydra lutris'') is a marine mammal native to the coasts of the northern and eastern Pacific Ocean, North Pacific Ocean. Adult sea otters typically weigh between , making them the heaviest members of ...

s, harbor seals

The harbor (or harbour) seal (''Phoca vitulina''), also known as the common seal, is a true seal found along temperate and Arctic marine coastlines of the Northern Hemisphere. The most widely distributed species of pinniped (walruses, eared sea ...

, bat ray

The bat ray (''Myliobatis californica'') is an eagle rayGill, T.N. (1865). "Note on the family of myliobatoids, and on a new species of ''Aetobatis''". ''Ann. Lyc. Nat. Hist. N. Y.'' 8, 135–138."Myliobatis californica". Integrated Taxonomic Info ...

s, kelp forest

Kelp forests are underwater areas with a high density of kelp, which covers a large part of the world's coastlines. Smaller areas of anchored kelp are called kelp beds. They are recognized as one of the most productive and dynamic ecosystems on E ...

s, pelican

Pelicans (genus ''Pelecanus'') are a genus of large water birds that make up the family Pelecanidae. They are characterized by a long beak and a large throat pouch used for catching prey and draining water from the scooped-up contents before ...

s and dolphin

A dolphin is an aquatic mammal in the cetacean clade Odontoceti (toothed whale). Dolphins belong to the families Delphinidae (the oceanic dolphins), Platanistidae (the Indian river dolphins), Iniidae (the New World river dolphins), Pontopori ...

s and several species of whales. Only a few miles offshore is the Monterey Canyon

Monterey Canyon, or Monterey Submarine Canyon, is a submarine canyon in Monterey Bay, California with steep canyon walls measuring a full in height from bottom to top, which height/depth rivals the depth of the Grand Canyon itself. It is the la ...

, the largest and deepest (at ) underwater canyon off the Pacific coast of North America, which grants scientists access to the deep sea within hours. The cornucopia of marine life makes Monterey a popular destination for scuba divers of all abilities ranging from novice to expert. Scuba classes are held at San Carlos State Beach, which has been a favorite with divers since the 1960s. The Monterey Bay Aquarium

Monterey Bay Aquarium is a Nonprofit organization, nonprofit public aquarium in Monterey, California. Known for its regional focus on the marine habitats of Monterey Bay, it was the first to exhibit a living kelp forest when it opened in Octob ...

on Cannery Row is one of the largest aquariums in North America, and several marine science

Oceanography (), also known as oceanology, sea science, ocean science, and marine science, is the scientific study of the ocean, including its physics, chemistry, biology, and geology.

It is an Earth science, which covers a wide range of top ...

laboratories, including Hopkins Marine Station

Hopkins Marine Station is the marine laboratory of Stanford University. It is located south of the university's main campus, in Pacific Grove, California (United States) on the Monterey Peninsula, adjacent to the Monterey Bay Aquarium. It is h ...

are located in the area.

Monterey is home to several museums and more than thirty carefully preserved historic buildings. Most of these buildings are adobes built in the mid-1800s. Some are museums and open to the public, including the Cooper Molera Adobe, Robert Louis Stevenson House, Casa Serrano, The Perry House, The Customs House, Colton Hall, Mayo Hayes O'Donnell Library and The First Brick House. Many others are only open during Monterey's annual adobe tour. The Monterey Museum of Art

The Monterey Museum of Art (MMA) an art museum located in Monterey, California. It was founded in 1959 as a chapter of the American Federation of Arts. The Monterey Museum of Art collects, preserves, and interprets the art of California from th ...

specializes in Early California Impressionist painting, photography, and contemporary art. Other youth-oriented art attractions include MY Museum, a children's museum, and YAC, an arts organization for teens.