Mongolian Language on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Mongolian is the principal language of the Mongolic

The earliest surviving Mongolian text may be the , a report on sports composed in Mongolian script on stone, which is most often dated at 1224 or 1225. The Mongolian-

The earliest surviving Mongolian text may be the , a report on sports composed in Mongolian script on stone, which is most often dated at 1224 or 1225. The Mongolian-

Mongolian belongs to the

Mongolian belongs to the

Mongolian divides vowels into three groups in a system of

Mongolian divides vowels into three groups in a system of

Mongolian has been written in a variety of alphabets, making it a language with one of the largest number of scripts used historically. The earliest stages of Mongolian (

Mongolian has been written in a variety of alphabets, making it a language with one of the largest number of scripts used historically. The earliest stages of Mongolian (

language family

A language family is a group of languages related through descent from a common ancestor, called the proto-language of that family. The term ''family'' is a metaphor borrowed from biology, with the tree model used in historical linguistics ...

that originated in the Mongolian Plateau. It is spoken by ethnic Mongols

Mongols are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, China ( Inner Mongolia and other 11 autonomous territories), as well as the republics of Buryatia and Kalmykia in Russia. The Mongols are the principal member of the large family o ...

and other closely related Mongolic peoples

The Mongolic peoples are a collection of East Asian people, East Asian-originated ethnic groups in East Asia, North Asia and Eastern Europe, who speak Mongolic languages. Their ancestors are referred to as Proto-Mongols. The largest contempora ...

who are native to modern Mongolia

Mongolia is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south and southeast. It covers an area of , with a population of 3.5 million, making it the world's List of countries and dependencies by po ...

and surrounding parts of East

East is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the fact that ea ...

, Central and North Asia

North Asia or Northern Asia () is the northern region of Asia, which is defined in geography, geographical terms and consists of three federal districts of Russia: Ural Federal District, Ural, Siberian Federal District, Siberian, and the Far E ...

. Mongolian is the official language of Mongolia and Inner Mongolia

Inner Mongolia, officially the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, is an Autonomous regions of China, autonomous region of China. Its border includes two-thirds of the length of China's China–Mongolia border, border with the country of Mongolia. ...

and a recognized language of Xinjiang

Xinjiang,; , SASM/GNC romanization, SASM/GNC: Chinese postal romanization, previously romanized as Sinkiang, officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an Autonomous regions of China, autonomous region of the China, People' ...

and Qinghai

Qinghai is an inland Provinces of China, province in Northwestern China. It is the largest provinces of China, province of China (excluding autonomous regions) by area and has the third smallest population. Its capital and largest city is Xin ...

.

The number of speakers across all its dialects may be 5–6 million, including the vast majority of the residents of Mongolia and many of the ethnic Mongol residents of the Inner Mongolia of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

. In Mongolia, Khalkha Mongolian is predominant, and is currently written in both Cyrillic

The Cyrillic script ( ) is a writing system used for various languages across Eurasia. It is the designated national script in various Slavic, Turkic, Mongolic, Uralic, Caucasian and Iranic-speaking countries in Southeastern Europe, Ea ...

and the traditional Mongolian script

The traditional Mongolian script, also known as the Hudum Mongol bichig, was the first Mongolian alphabet, writing system created specifically for the Mongolian language, and was the most widespread until the introduction of Cyrillic script, Cy ...

. In Inner Mongolia, it is dialect

A dialect is a Variety (linguistics), variety of language spoken by a particular group of people. This may include dominant and standard language, standardized varieties as well as Vernacular language, vernacular, unwritten, or non-standardize ...

ally more diverse and written in the traditional Mongolian script. However, Mongols in both countries often use the Latin script

The Latin script, also known as the Roman script, is a writing system based on the letters of the classical Latin alphabet, derived from a form of the Greek alphabet which was in use in the ancient Greek city of Cumae in Magna Graecia. The Gree ...

for convenience on the Internet.

In the discussion of grammar to follow, the variety of Mongolian treated is the standard written Khalkha formalized in the writing conventions and in grammar as taught in schools, but much of it is also valid for vernacular (spoken) Khalkha and other Mongolian dialects, especially Chakhar Mongolian.

Some classify several other Mongolic languages like Buryat and Oirat as varieties of Mongolian, but this classification is not in line with the current international standard.

Mongolian is a language with vowel harmony

In phonology, vowel harmony is a phonological rule in which the vowels of a given domain – typically a phonological word – must share certain distinctive features (thus "in harmony"). Vowel harmony is typically long distance, meaning tha ...

and a complex syllabic structure compared to other Mongolic languages, allowing clusters of up to three consonants syllable-finally. It is a typical agglutinative language

An agglutinative language is a type of language that primarily forms words by stringing together morphemes (word parts)—each typically representing a single grammatical meaning—without significant modification to their forms ( agglutinations) ...

that relies on suffix chains in the verbal and nominal domains. While there is a basic word order, subject–object–verb, ordering among noun phrase

A noun phrase – or NP or nominal (phrase) – is a phrase that usually has a noun or pronoun as its head, and has the same grammatical functions as a noun. Noun phrases are very common cross-linguistically, and they may be the most frequently ...

s is relatively free, as grammatical roles are indicated by a system of about eight grammatical case

A grammatical case is a category of nouns and noun modifiers (determiners, adjectives, participles, and Numeral (linguistics), numerals) that corresponds to one or more potential grammatical functions for a Nominal group (functional grammar), n ...

s. There are five voices. Verbs are marked for voice, aspect, tense and epistemic modality

Epistemic modality is a sub-type of linguistic modality that encompasses knowledge, belief, or credence in a proposition. Epistemic modality is exemplified by the English modal verb, modals ''may'', ''might'', ''must''. However, it occurs cross-li ...

/evidentiality

In linguistics, evidentiality is, broadly, the indication of the nature of evidence for a given statement; that is, whether evidence exists for the statement and if so, what kind. An evidential (also verificational or validational) is the particul ...

. In sentence linking, a special role is played by converb

In theoretical linguistics, a converb ( abbreviated ) is a nonfinite verb form that serves to express adverbial subordination: notions like 'when', 'because', 'after' and 'while'. Other terms that have been used to refer to converbs include ''adv ...

s.

Modern Mongolian evolved from Middle Mongol, the language spoken in the Mongol Empire

The Mongol Empire was the List of largest empires, largest contiguous empire in human history, history. Originating in present-day Mongolia in East Asia, the Mongol Empire at its height stretched from the Sea of Japan to parts of Eastern Euro ...

of the 13th and 14th centuries. In the transition, a major shift in the vowel-harmony paradigm occurred, long vowels developed, the case system changed slightly, and the verbal system was restructured. Mongolian is related to the extinct Khitan language

Khitan or Kitan ( in large Khitan script, large script or in small Khitan script, small, ''Khitai''; , ''Qìdānyǔ''), also known as Liao, is an extinct language once spoken in Northeast Asia by the Khitan people (4th to 13th century CE). It wa ...

. It was believed that Mongolian was related to Turkic, Tungusic, Korean and Japonic languages

Japonic or Japanese–Ryukyuan () is a language family comprising Japanese language, Japanese, spoken in the main islands of Japan, and the Ryukyuan languages, spoken in the Ryukyu Islands. The family is universally accepted by linguists, and sig ...

but this view is now seen as obsolete by a majority of (but not all) comparative linguists. These languages have been grouped under the Altaic language family and contrasted with the Mainland Southeast Asia linguistic area

The Mainland Southeast Asia linguistic area is a sprachbund including languages of the Sino-Tibetan, Hmong–Mien (or Miao–Yao), Kra–Dai, Austronesian and Austroasiatic families spoken in an area stretching from Thailand to China. Neighb ...

. However, instead of a common genetic origin, Clauson, Doerfer, and Shcherbak proposed that Turkic, Mongolic and Tungusic languages form a language ''Sprachbund

A sprachbund (, from , 'language federation'), also known as a linguistic area, area of linguistic convergence, or diffusion area, is a group of languages that share areal features resulting from geographical proximity and language contact. Th ...

'', rather than common origin. Mongolian literature is well attested in written form from the 13th century but has earlier Mongolic precursors in the literature of the Khitan and other Xianbei

The Xianbei (; ) were an ancient nomadic people that once resided in the eastern Eurasian steppes in what is today Mongolia, Inner Mongolia, and Northeastern China. The Xianbei were likely not of a single ethnicity, but rather a multiling ...

peoples. The Bugut inscription dated to 584 CE and the Inscription of Hüis Tolgoi dated to 604–620 CE appear to be the oldest substantial Mongolic or Para-Mongolic

Para-Mongolic is a proposed group of languages that is considered to be an extinct sister branch of the Mongolic languages. Para-Mongolic contains certain historically attested extinct languages, among them Khitan language, Khitan and Tuyuhun lang ...

texts discovered.

Name

Writers such as Owen Lattimore referred to Mongolian as "the Mongol language".History

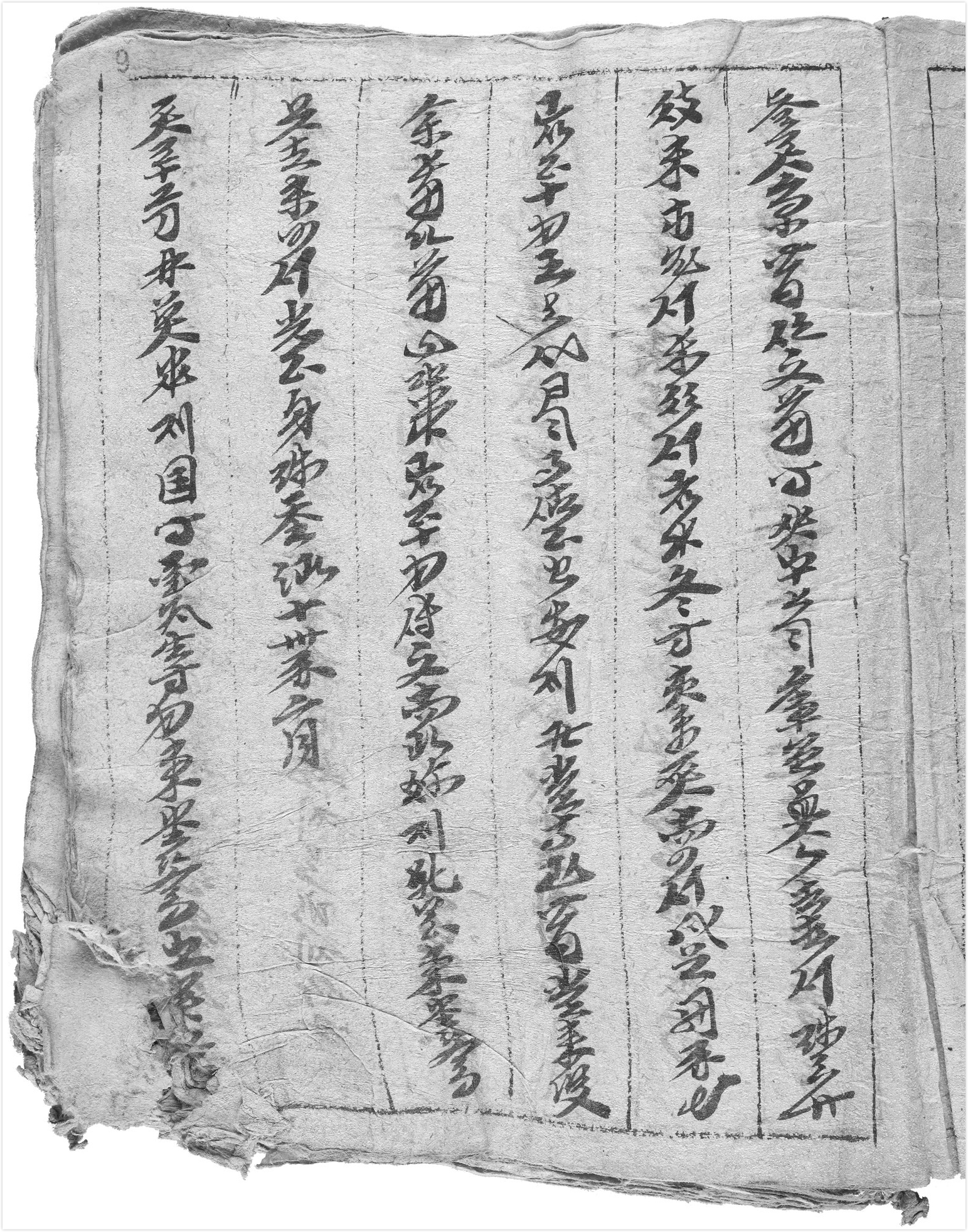

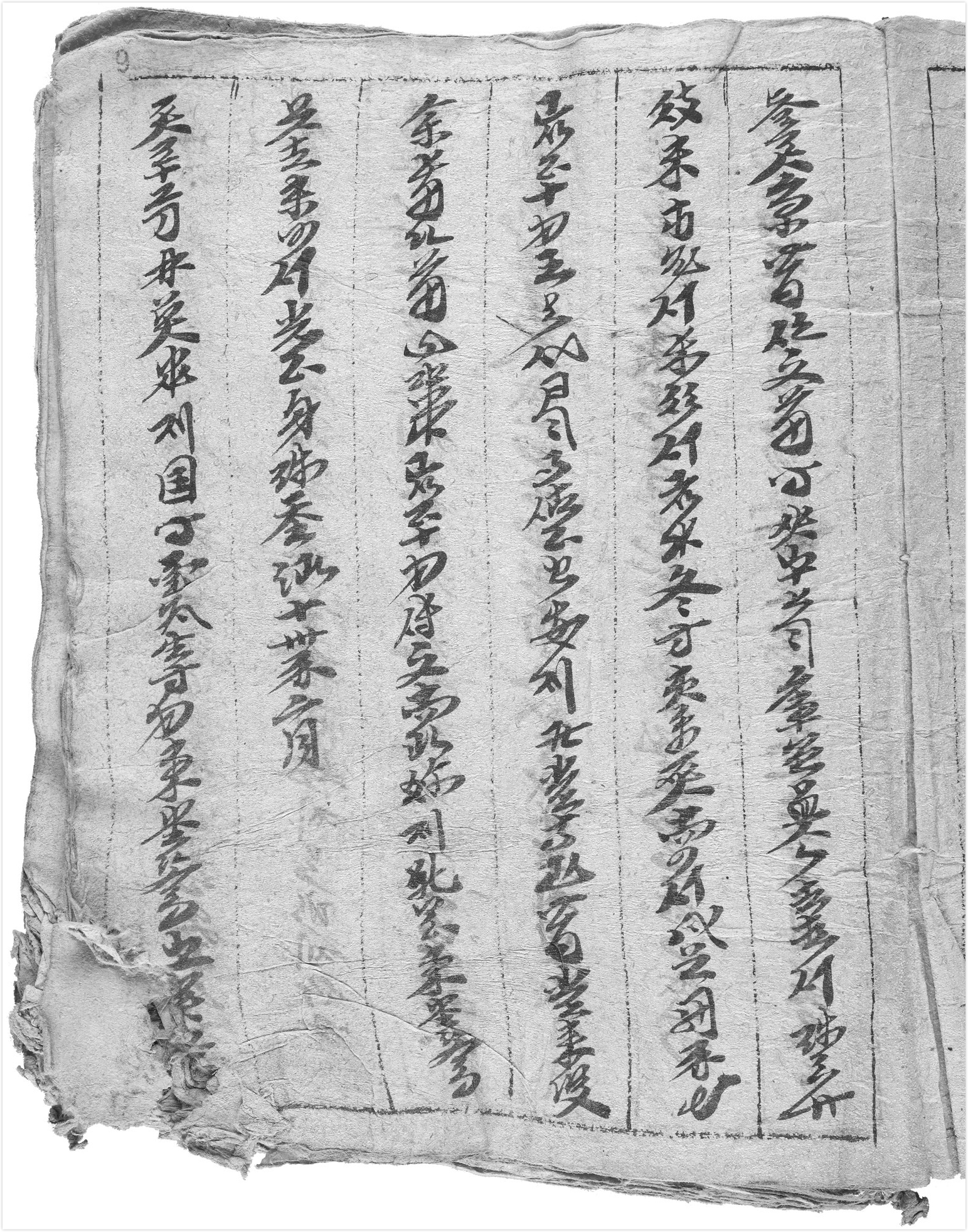

The earliest surviving Mongolian text may be the , a report on sports composed in Mongolian script on stone, which is most often dated at 1224 or 1225. The Mongolian-

The earliest surviving Mongolian text may be the , a report on sports composed in Mongolian script on stone, which is most often dated at 1224 or 1225. The Mongolian-Armenian

Armenian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Armenia, a country in the South Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Armenians, the national people of Armenia, or people of Armenian descent

** Armenian diaspora, Armenian communities around the ...

wordlist of 55 words compiled by Kirakos of Gandzak (13th century) is the first written record of Mongolian words. From the 13th to the 15th centuries, Mongolian language texts were written in four scripts (not counting some vocabulary written in Western scripts): Uyghur Mongolian (UM) script (an adaptation of the Uyghur alphabet ), 'Phags-pa script (Ph) (used in decrees), Chinese (SM) (''The Secret History of the Mongols

The ''Secret History of the Mongols'' is the oldest surviving literary work in the Mongolic languages. Written for the Borjigin, Mongol royal family some time after the death of Genghis Khan in 1227, it recounts his life and conquests, and parti ...

''), and Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

(AM) (used in dictionaries). While they are the earliest texts available, these texts have come to be called " Middle Mongol" in scholarly practice. The documents in UM script show some distinct linguistic characteristics and are therefore often distinguished by terming their language "Preclassical Mongolian".

The Yuan dynasty

The Yuan dynasty ( ; zh, c=元朝, p=Yuáncháo), officially the Great Yuan (; Mongolian language, Mongolian: , , literally 'Great Yuan State'), was a Mongol-led imperial dynasty of China and a successor state to the Mongol Empire after Div ...

referred to the Mongolian language in Chinese as "Guoyu" ( zh, t=國語), which means "National language", a term also used by other non-Han dynasties to refer to their languages such as the Manchu language

Manchu ( ) is a critically endangered language, endangered Tungusic language native to the historical region of Manchuria in Northeast China.

As the traditional native language of the Manchu people, Manchus, it was one of the official language ...

during the Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing, was a Manchu-led Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China and an early modern empire in East Asia. The last imperial dynasty in Chinese history, the Qing dynasty was preceded by the ...

, the Jurchen language during the Jin dynasty (1115–1234)

The Jin dynasty (, ), officially known as the Great Jin (), was a Jurchen people, Jurchen-led Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China and empire ruled by the Wanyan clan that existed between 1115 and 1234. It is also often called the ...

, the Khitan language

Khitan or Kitan ( in large Khitan script, large script or in small Khitan script, small, ''Khitai''; , ''Qìdānyǔ''), also known as Liao, is an extinct language once spoken in Northeast Asia by the Khitan people (4th to 13th century CE). It wa ...

during the Liao dynasty, and the Xianbei language

The Xianbei (; ) were an ancient nomadic people that once resided in the eastern Eurasian steppes in what is today Mongolia, Inner Mongolia, and Northeast China, Northeastern China. The Xianbei were likely not of a single ethnicity, but rath ...

during the Northern Wei

Wei (), known in historiography as the Northern Wei ( zh, c=北魏, p=Běi Wèi), Tuoba Wei ( zh, c=拓跋魏, p=Tuòbá Wèi), Yuan Wei ( zh, c=元魏, p=Yuán Wèi) and Later Wei ( zh, t=後魏, p=Hòu Wèi), was an Dynasties of China, impe ...

period.

The next distinct period is Classical Mongolian, which is dated from the 17th to the 19th century. This is a written language with a high degree of standardization in orthography and syntax that sets it quite apart from the subsequent Modern Mongolian. The most notable documents in this language are the Mongolian Kangyur and Tengyur as well as several chronicles. In 1686, the Soyombo alphabet (Buddhist texts

Buddhist texts are religious texts that belong to, or are associated with, Buddhism and Schools of Buddhism, its traditions. There is no single textual collection for all of Buddhism. Instead, there are three main Buddhist Canons: the Pāli C ...

) was created, giving distinctive evidence on early classical Mongolian phonological peculiarities.

Geographic distribution

Mongolian is the official national language of Mongolia, where it is spoken (but not always written) by nearly 3.6 million people (2014 estimate), and the official provincial language (both spoken and written forms) of Inner Mongolia, where there are at least 4.1 million ethnic Mongols. Across the whole of China, the language is spoken by roughly half of the country's 5.8 million ethnic Mongols (2005 estimate) However, the exact number of Mongolian speakers in China is unknown, as there is no data available on the language proficiency of that country's citizens. The use of Mongolian in Inner Mongolia has witnessed periods of decline and revival over the last few hundred years. The language experienced a decline during the late Qing period, a revival between 1947 and 1965, a second decline between 1966 and 1976, a second revival between 1977 and 1992, and a third decline between 1995 and 2012. However, in spite of the decline of the Mongolian language in some of Inner Mongolia's urban areas and educational spheres, the ethnic identity of the urbanized Chinese-speaking Mongols is most likely going to survive due to the presence of urban ethnic communities. The multilingual situation in Inner Mongolia does not appear to obstruct efforts by ethnic Mongols to preserve their language. Although an unknown number of Mongols in China, such as the Tumets, may have completely or partially lost the ability to speak their language, they are still registered as ethnic Mongols and continue to identify themselves as ethnic Mongols. The children of inter-ethnic Mongol-Chinese marriages also claim to be and are registered as ethnic Mongols so they can benefit from the preferential policies for minorities in education, healthcare, family planning, school admissions, the hiring and promotion, the financing and taxation of businesses, and regional infrastructural support given to ethnic minorities in China. In 2020, the Chinese government required three subjects—language and literature, politics, and history—to be taught in Mandarin in Mongolian-language primary and secondary schools in the Inner Mongolia since September, which caused widespread protests among ethnic Mongol communities. These protests were quickly suppressed by the Chinese government. Mandarin has been deemed the only language of instruction for all subjects as of September 2023.Classification and varieties

Mongolic languages

The Mongolic languages are a language family spoken by the Mongolic peoples in North Asia, East Asia, Central Asia, and Eastern Europe mostly in Mongolia and surrounding areas and in Kalmykia and Buryatia. The best-known member of this languag ...

. The delimitation of the Mongolian language within Mongolic is a much disputed theoretical problem, one whose resolution is impeded by the fact that existing data for the major varieties is not easily arrangeable according to a common set of linguistic criteria. Such data might account for the historical

History is the systematic study of the past, focusing primarily on the human past. As an academic discipline, it analyses and interprets evidence to construct narratives about what happened and explain why it happened. Some theorists categ ...

development of the Mongolian dialect continuum

A dialect continuum or dialect chain is a series of Variety (linguistics), language varieties spoken across some geographical area such that neighboring varieties are Mutual intelligibility, mutually intelligible, but the differences accumulat ...

, as well as for its sociolinguistic qualities. Though phonological and lexical studies are comparatively well developed, the basis has yet to be laid for a comparative morphosyntactic

In linguistics, morphology is the study of words, including the principles by which they are formed, and how they relate to one another within a language. Most approaches to morphology investigate the structure of words in terms of morphemes, wh ...

study, for example between such highly diverse varieties as Khalkha and Khorchin.

In Juha Janhunen's book titled ''Mongolian'', he groups the Mongolic language family into four distinct linguistic branches:

* the Dagur branch, made up of just the Dagur language

The Dagur, Daghur, Dahur, or Daur language, is a Mongolic language, as well as a distinct branch of the Mongolic language family, and is primarily spoken by members of the Daur ethnic group.

There is no written standard in use, although a Piny ...

, which is spoken in the northeast area of Manchuria

Manchuria is a historical region in northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day northeast China and parts of the modern-day Russian Far East south of the Uda (Khabarovsk Krai), Uda River and the Tukuringra-Dzhagdy Ranges. The exact ...

in China, specifically in Morin Dawa Daur Autonomous Banner of Hulunbuir, and in Meilisi Daur District of Qiqihar, Heilongjiang

Heilongjiang is a province in northeast China. It is the northernmost and easternmost province of the country and contains China's northernmost point (in Mohe City along the Amur) and easternmost point (at the confluence of the Amur and Us ...

;

* the Moghol branch, made up of just the Moghol language, spoken in Afghanistan, and is possibly extinct;

* the Shirongolic (or Southern Mongolic) branch, made up of roughly seven languages, which are spoken in the Amdo region of Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ), or Greater Tibet, is a region in the western part of East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are other ethnic groups s ...

;

* the Common Mongolic (or Central Mongolic) branch, made up of roughly six language varieties, to which Mongolian proper belongs.

The Common Mongolic branch is grouped in the following way:

* Khalkha () is spoken in Mongolia, but some dialects (e.g. Cahar) are also spoken in the Inner Mongolia

Inner Mongolia, officially the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, is an Autonomous regions of China, autonomous region of China. Its border includes two-thirds of the length of China's China–Mongolia border, border with the country of Mongolia. ...

region of China.

* Khorchin () is spoken to the east in eastern Inner Mongolia and Manchuria

Manchuria is a historical region in northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day northeast China and parts of the modern-day Russian Far East south of the Uda (Khabarovsk Krai), Uda River and the Tukuringra-Dzhagdy Ranges. The exact ...

.

* Ordos is spoken to the south, in Ordos City

Ordos, also known as Ih Ju, is one of the twelve List of administrative divisions of Inner Mongolia, major subdivisions of Inner Mongolia, China. It lies within the Ordos Plateau of the Yellow River. Although mainly rural, Ordos is administered ...

in Inner Mongolia.

* Oirat, is spoken to the west, in Dzungaria.

* Khamnigan () is spoken in northeast Mongolia and in northwest of Manchuria.

* Buryat () is spoken to the north, in the Republic of Buryatia

Buryatia, officially the Republic of Buryatia, is a republic of Russia located in the Russian Far East. Formerly part of the Siberian Federal District, it has been administered as part of the Far Eastern Federal District since 2018. To its nort ...

of Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

, as well as in the Barga region of Hulun Buir League in Inner Mongolia.

There is no disagreement that the Khalkha dialect of the Mongolian state is Mongolian. However, the status of certain varieties in the Common Mongolic group—whether they are languages distinct from Mongolian or just dialects of it—is disputed. There are at least three such varieties: Oirat (including the Kalmyk variety) and Buryat, both of which are spoken in Russia, Mongolia, and China; and Ordos, spoken around Inner Mongolia's Ordos City

Ordos, also known as Ih Ju, is one of the twelve List of administrative divisions of Inner Mongolia, major subdivisions of Inner Mongolia, China. It lies within the Ordos Plateau of the Yellow River. Although mainly rural, Ordos is administered ...

. The influential classification of Sanžeev (1953) proposed a "Mongolian language" consisting of just the three dialects Khalkha, Chakhar, and Ordos, with Buryat and Oirat judged to be independent languages. On the other hand, Luvsanvandan (1959) proposed a much broader "Mongolian language" consisting of a Central dialect (Khalkha, Chakhar, Ordos), an Eastern dialect (Kharchin, Khorchin), a Western dialect (Oirat, Kalmyk), and a Northern dialect (consisting of two Buryat varieties). Additionally, the ''Language Policy in the People's Republic of China: Theory and Practice Since 1949'', states that Mongolian can be classified into four dialects: the Khalkha dialect in the middle, the Horcin-Haracin dialect in the East, Oriat-Hilimag in the west, and Bargu–Buriyad in the north.

Some Western scholars propose that the relatively well researched Ordos variety is an independent language due to its conservative syllable structure and phoneme

A phoneme () is any set of similar Phone (phonetics), speech sounds that are perceptually regarded by the speakers of a language as a single basic sound—a smallest possible Phonetics, phonetic unit—that helps distinguish one word fr ...

inventory. While the placement of a variety like Alasha, which is under the cultural influence of Inner Mongolia but historically tied to Oirat, and of other border varieties like Darkhad would very likely remain problematic in any classification, the central problem remains the question of how to classify Chakhar, Khalkha, and Khorchin in relation to each other and in relation to Buryat and Oirat. The split of into before *i and before all other reconstructed vowels, which is found in Mongolia but not in Inner Mongolia, is often cited as a fundamental distinction, for example Proto-Mongolic , Khalkha , Chakhar 'year' versus Proto-Mongolic , Khalkha , Chakhar 'few'. On the other hand, the split between the past tense verbal suffixes - in the Central varieties v. - in the Eastern varieties is usually seen as a merely stochastic Stochastic (; ) is the property of being well-described by a random probability distribution. ''Stochasticity'' and ''randomness'' are technically distinct concepts: the former refers to a modeling approach, while the latter describes phenomena; i ...

difference.

In Inner Mongolia, official language policy divides the Mongolian language into three dialects: Standard Mongolian of Inner Mongolia, Oirat, and Barghu-Buryat. The Standard Mongolian of Inner Mongolia is said to consist of Chakhar, Ordos, Baarin, Khorchin, Kharchin, and Alasha. The authorities have synthesized a literary standard for Mongolian in whose grammar is said to be based on the Standard Mongolian of Inner Mongolia and whose pronunciation is based on the Chakhar dialect as spoken in the Plain Blue Banner. Dialectologically, however, western Mongolian dialects in Inner Mongolia are closer to Khalkha than they are to eastern Mongolian dialects in Inner Mongolia: e.g. Chakhar is closer to Khalkha than to Khorchin.

List of dialects

Juha Janhunen (2003: 179) lists the following Mongol dialects, most of which are spoken inInner Mongolia

Inner Mongolia, officially the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, is an Autonomous regions of China, autonomous region of China. Its border includes two-thirds of the length of China's China–Mongolia border, border with the country of Mongolia. ...

.

* Tongliao group

**Horchin

**Jasagtu

**Jarut

**Jalait

**Dörbet

**Gorlos

* Juu Uda group

**Aru Horchin

**Baarin

**Ongniut

**Naiman

**Aohan

* Josotu group

**Harachin

**Tümet

* Ulan cab group

** Cahar

**Urat

**Darhan

**Muumingan

**Dörben Küüket

**Keshigten

* Shilingol group

**Üdzümüchin

**Huuchit

**Abaga

**Abaganar

**Sönit

*Outer Mongolian group

** Halh

**Hotogoit

** Darhad

**Congol

**Sartul

**Dariganga

Standard varieties

There are two standard varieties of Mongolian.Mongolia

Standard Mongolian in the state of Mongolia is based on the northern Khalkha Mongolian dialects, which include the dialect of Ulaanbaatar, and is written in the Mongolian Cyrillic script.Svantesson ''et al.'' (2005): 9-10China

Standard Mongolian in Inner Mongolia is based on the Chakhar Mongolian of the Khalkha dialect group, spoken in the Shuluun Huh/Zhènglán Banner, and is written in the traditional Mongolian script. The number of Mongolian speakers in China is still larger than in the state of Mongolia, where the majority of Mongolians in China speak one of the Khorchin dialects, or rather more than two million of them speak the Khorchin dialect itself as their mother tongue, so that the Khorchin dialect group has about as many speakers as the Khalkha dialect group in the State of Mongolia. Nevertheless, the Chakhar dialect, which today has only about 100,000 native speakers and belongs to the Khalkha dialect group, is the basis of standard Mongolian in China.Differences

The characteristic differences in the pronunciation of the two standard varieties include the umlauts in Inner Mongolia and the palatalized consonants in Mongolia (see below) as well as the splitting of the Middle Mongol affricates * ( ') and * ( ') into ( ) and ( ) versus ( ) and ( ) in Mongolia: Aside from these differences in pronunciation, there are also differences in vocabulary and language use: in the state of Mongolia moreloanword

A loanword (also a loan word, loan-word) is a word at least partly assimilated from one language (the donor language) into another language (the recipient or target language), through the process of borrowing. Borrowing is a metaphorical term t ...

s from Russian are being used, while in Inner Mongolia more loanwords from Chinese have been adopted.

Phonology

The following description is based primarily on the Khalkha dialect as spoken in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia's capital. The phonologies of other varieties such as Ordos, Khorchin, and even Chakhar, differ considerably. This section discusses thephonology

Phonology (formerly also phonemics or phonematics: "phonemics ''n.'' 'obsolescent''1. Any procedure for identifying the phonemes of a language from a corpus of data. 2. (formerly also phonematics) A former synonym for phonology, often pre ...

of Khalkha Mongolian with subsections on Vowels, Consonants, Phonotactics and Stress.

Vowels

The standard language has seven monophthong vowel phonemes. They are aligned into threevowel harmony

In phonology, vowel harmony is a phonological rule in which the vowels of a given domain – typically a phonological word – must share certain distinctive features (thus "in harmony"). Vowel harmony is typically long distance, meaning tha ...

groups by a parameter called ATR ( advanced tongue root); the groups are −ATR, +ATR, and neutral. This alignment seems to have superseded an alignment according to oral backness. However, some scholars still describe Mongolian as being characterized by a distinction between front vowels and back vowels, and the front vowel spellings 'ö' and 'ü' are still often used in the West to indicate two vowels which were historically front. The Mongolian vowel system also has rounding harmony.

Length is phonemic for vowels, and except short which has merged into short at least in Ulaanbaatar dialect, each of the other six phonemes occurs both short and long. Phonetically, short has become centralised to the central vowel

A central vowel, formerly also known as a mixed vowel, is any in a class of vowel sound used in some spoken languages. The defining characteristic of a central vowel is that the tongue is positioned approximately halfway between a front vowel ...

.

In the following table, the seven vowel phonemes, with their length variants, are arranged and described phonetically. The vowels in the Mongolian Cyrillic alphabet are:

:

:

Khalkha also has four diphthong

A diphthong ( ), also known as a gliding vowel or a vowel glide, is a combination of two adjacent vowel sounds within the same syllable. Technically, a diphthong is a vowel with two different targets: that is, the tongue (and/or other parts of ...

s: historically but are pronounced more like ; e.g. in () 'dog', in () 'sea', in () 'to cry', and in () 'factory'. There are three additional rising diphthongs (), () (); e.g., in () 'individually', in () 'barracks', and in () 'necessary'.

Allophones

This table below lists vowel allophones (short vowels allophones in non-initial positions are used interchangeably with schwa):ATR harmony

vowel harmony

In phonology, vowel harmony is a phonological rule in which the vowels of a given domain – typically a phonological word – must share certain distinctive features (thus "in harmony"). Vowel harmony is typically long distance, meaning tha ...

:

:

For historical reasons, these have been traditionally labeled as "front" vowels and "back" vowels, as /o/ and /u/ developed from /ø/ and /y/, while /ɔ/ and /ʊ/ developed from /o/ and /u/ in Middle Mongolian. Indeed, in Mongolian romanization

In linguistics, romanization is the conversion of text from a different writing system to the Latin script, Roman (Latin) script, or a system for doing so. Methods of romanization include transliteration, for representing written text, and tra ...

s, the vowels and are often conventionally rendered as and , while the vowels and are expressed as and . However, for modern Mongolian phonology, it is more appropriate to instead characterize the two vowel-harmony groups by the dimension of tongue root position. There is also one neutral vowel, , not belonging to either group.

All the vowels in a non compound word, including all its suffixes, must belong to the same group. If the first vowel is −ATR, then every vowel of the word must be either or a −ATR vowel. Likewise, if the first vowel is a +ATR vowel, then every vowel of the word must be either or a +ATR vowel. In the case of suffixes, which must change their vowels to conform to different words, two patterns predominate. Some suffixes contain an archiphoneme that can be realized as ; e.g.

* 'household' + (instrumental) → 'by a household'

* 'sentry' + (instrumental) → 'by a sentry'

Other suffixes can occur in being realized as , in which case all −ATR vowels lead to and all +ATR vowels lead to ; e.g.

* 'to take' + (causative) →

If the only vowel in the word stem is , the suffixes will use the +ATR suffix forms.

Rounding harmony

Mongolian also has rounding harmony, which does not apply to close vowels. If a stem contains (or ), a suffix that is specified for an open vowel will have (or , respectively) as well. However, this process is blocked by the presence of (or ) and ; e.g. 'came in', but 'inserted'.Vowel length

The pronunciation of long and shortvowel

A vowel is a speech sound pronounced without any stricture in the vocal tract, forming the nucleus of a syllable. Vowels are one of the two principal classes of speech sounds, the other being the consonant. Vowels vary in quality, in loudness a ...

s depends on the syllable

A syllable is a basic unit of organization within a sequence of speech sounds, such as within a word, typically defined by linguists as a ''nucleus'' (most often a vowel) with optional sounds before or after that nucleus (''margins'', which are ...

's position in the word. In word-initial syllables, there is a phonemic

A phoneme () is any set of similar speech sounds that are perceptually regarded by the speakers of a language as a single basic sound—a smallest possible phonetic unit—that helps distinguish one word from another. All languages con ...

contrast in vowel length

In linguistics, vowel length is the perceived or actual length (phonetics), duration of a vowel sound when pronounced. Vowels perceived as shorter are often called short vowels and those perceived as longer called long vowels.

On one hand, many ...

. A long vowel has about 208% the length of a short vowel. In word-medial and word-final syllables, formerly long vowels are now only 127% as long as short vowels in initial syllables, but they are still distinct from initial-syllable short vowels. Short vowels in noninitial syllables differ from short vowels in initial syllables by being only 71% as long and by being centralized in articulation. As they are nonphonemic, their position is determined according to phonotactic requirements.

Consonants

The following table lists the consonants of Khalkha Mongolian. The consonants enclosed in parentheses occur only in loanwords. The occurrence of palatalized consonant phonemes, except , is restricted to words with ��ATRvowels. A rare feature among the world's languages, Mongolian has neither a voiced lateral approximant, such as , nor the voiceless velar plosive ; instead, it has avoiced alveolar lateral fricative

The voiced alveolar lateral fricative is a type of consonantal sound, used in some spoken languages. The symbol in the International Phonetic Alphabet that represents voiced dental, alveolar, and postalveolar lateral fricatives is (sometime ...

, , which is often realized as voiceless . In word-final position, (if not followed by a vowel in historical forms) is realized as . Aspirated consonants are preaspirated in medial and word-final contexts, devoicing preceding consonants and vowels. Devoiced short vowels are often deleted.

Syllable structure and phonotactics

The maximalsyllable

A syllable is a basic unit of organization within a sequence of speech sounds, such as within a word, typically defined by linguists as a ''nucleus'' (most often a vowel) with optional sounds before or after that nucleus (''margins'', which are ...

is CVVCCC, where the last C is a word-final suffix. A single short vowel rarely appears in syllable-final position. If a word was monosyllabic historically, *CV has become CVV. In native words, the following consonants do not occur word-initially: , , , , , , , and . is restricted to codas (else it becomes ), and and do not occur in codas for historical reasons. For two-consonant clusters, the following restrictions obtain:

* a palatalized consonant can be preceded only by another palatalized consonant or sometimes by and

* may precede only and

* does not seem to appear in second position

* and do not occur as first consonant and as second consonant only if preceded by or or their palatalized counterparts.

Clusters that do not conform to these restrictions will be broken up by an epenthetic nonphonemic vowel in a syllabification that takes place from right to left. For instance, 'two', 'work', and 'neutral' are, phonemically, , , and respectively. In such cases, an epenthetic vowel is inserted to prevent disallowed consonant clusters. Thus, in the examples given above, the words are phonetically , , and . The phonetic form of the epenthetic vowel follows from vowel harmony triggered by the vowel in the preceding syllable. Usually it is a centralized version of the same sound, with the following exceptions: preceding produces ; will be ignored if there is a nonneutral vowel earlier in the word; and a postalveolar or palatalized consonant will be followed by an epenthetic , as in .

Stress

Stress in Mongolian is non-phonemic (does not distinguish different meanings) and is thus considered to depend entirely on syllable structure. But scholarly opinions on stress placement diverge sharply. Most native linguists, regardless of which dialect they speak, claim that stress falls on the first syllable. Between 1941 and 1975, several Western scholars proposed that the leftmost heavy syllable gets the stress. Yet other positions were taken in works published between 1835 and 1915. Walker (1997) proposes that stress falls on the rightmost heavy syllable unless this syllable is word-final: : A "heavy syllable" is defined as one that is at least the length of a full vowel; short word-initial syllables are thereby excluded. If a word is bisyllabic and the only heavy syllable is word-final, it gets stressed anyway. In cases where there is only one phonemic short word-initial syllable, even this syllable can get the stress: : More recently, the most extensive collection of phonetic data so far in Mongolian studies has been applied to a partial account of stress placement in the closely related Chakhar dialect. The conclusion is drawn that di- and trisyllabic words with a short first syllable are stressed on the second syllable. But if their first syllable is long, then the data for different acoustic parameters seems to support conflicting conclusions: intensity data often seems to indicate that the first syllable is stressed, while F0 seems to indicate that it is the second syllable that is stressed.Grammar

The grammar in this article is also based primarily on Khalkha Mongolian. Unlike the phonology, most of what is said about morphology and syntax also holds true for Chakhar, while Khorchin is somewhat more diverse.Morphology

Modern Mongolian is anagglutinative

In linguistics, agglutination is a morphological process in which words are formed by stringing together morphemes (word parts), each of which corresponds to a single syntactic feature. Languages that use agglutination widely are called agglu ...

—almost exclusively suffixing—language, with the only exception being reduplication. Mongolian also does not have gendered nouns, or definite articles like "the". Most of the suffixes consist of a single morpheme

A morpheme is any of the smallest meaningful constituents within a linguistic expression and particularly within a word. Many words are themselves standalone morphemes, while other words contain multiple morphemes; in linguistic terminology, this ...

. There are many derivational morphemes. For example, the word consists of the root 'to be', an epenthetic ‑‑, the causative ‑‑ (hence 'to cause to be', to found), the derivative

In mathematics, the derivative is a fundamental tool that quantifies the sensitivity to change of a function's output with respect to its input. The derivative of a function of a single variable at a chosen input value, when it exists, is t ...

suffix ‑ that forms nouns created by the action (like -''ation'' in ''organisation'') and the complex suffix ‑ denoting something that belongs to the modified word (‑ would be genitive

In grammar, the genitive case ( abbreviated ) is the grammatical case that marks a word, usually a noun, as modifying another word, also usually a noun—thus indicating an attributive relationship of one noun to the other noun. A genitive can ...

).

Nominal compounds are quite frequent. Some derivational verbal suffixes are rather productive, e.g. 'to speak', 'to speak with each other'. Formally, the independent words derived using verbal suffixes can roughly be divided into three classes: final verb

A verb is a word that generally conveys an action (''bring'', ''read'', ''walk'', ''run'', ''learn''), an occurrence (''happen'', ''become''), or a state of being (''be'', ''exist'', ''stand''). In the usual description of English, the basic f ...

s, which can only be used sentence-finally, i.e. ‑ (mainly future or generic statements) or ‑ (second person imperative); participle

In linguistics, a participle (; abbr. ) is a nonfinite verb form that has some of the characteristics and functions of both verbs and adjectives. More narrowly, ''participle'' has been defined as "a word derived from a verb and used as an adject ...

s (often called "verbal nouns"), which can be used clause-finally or attributively, i.e. ‑ ( perfect-past

The past is the set of all Spacetime#Definitions, events that occurred before a given point in time. The past is contrasted with and defined by the present and the future. The concept of the past is derived from the linear fashion in which human ...

) or ‑ 'want to'; and converb

In theoretical linguistics, a converb ( abbreviated ) is a nonfinite verb form that serves to express adverbial subordination: notions like 'when', 'because', 'after' and 'while'. Other terms that have been used to refer to converbs include ''adv ...

s, which can link clauses or function adverbial

In English grammar, an adverbial ( abbreviated ) is a word (an adverb) or a group of words (an adverbial clause or adverbial phrase) that modifies or more closely defines the sentence or the verb. (The word ''adverbial'' itself is also used as a ...

ly, i.e. ‑ (qualifies for any adverbial function or neutrally connects two sentences

The ''Sentences'' (. ) is a compendium of Christian theology written by Peter Lombard around 1150. It was the most important religious textbook of the Middle Ages.

Background

The sentence genre emerged from works like Prosper of Aquitaine's ...

) or ‑ (the action of the main clause

In language, a clause is a Constituent (linguistics), constituent or Phrase (grammar), phrase that comprises a semantic predicand (expressed or not) and a semantic Predicate (grammar), predicate. A typical clause consists of a subject (grammar), ...

takes place until the action expressed by the suffixed verb begins).

Nouns

Roughly speaking, Mongolian has between seven and nine cases:nominative

In grammar, the nominative case ( abbreviated ), subjective case, straight case, or upright case is one of the grammatical cases of a noun or other part of speech, which generally marks the subject of a verb, or (in Latin and formal variants of E ...

(unmarked

In linguistics and social sciences, markedness is the state of standing out as nontypical or divergent as opposed to regular or common. In a marked–unmarked relation, one term of an opposition is the broader, dominant one. The dominant defau ...

), genitive

In grammar, the genitive case ( abbreviated ) is the grammatical case that marks a word, usually a noun, as modifying another word, also usually a noun—thus indicating an attributive relationship of one noun to the other noun. A genitive can ...

, dative- locative, accusative, ablative, instrumental

An instrumental or instrumental song is music without any vocals, although it might include some inarticulate vocals, such as shouted backup vocals in a big band setting. Through Semantic change, semantic widening, a broader sense of the word s ...

, comitative

In grammar, the comitative case (abbreviated ) is a grammatical case that denotes accompaniment. In English, the preposition "with", in the sense of "in company with" or "together with", plays a substantially similar role. Other uses of "with", l ...

, privative

A privative, named from Latin language, Latin , is a particle (grammar), particle that negates or inverts the semantics, value of the root word, stem of the word. In Indo-European languages, many privatives are prefix (linguistics), prefixes, bu ...

and directive, though the final two are not always considered part of the case paradigm. If a direct object is definite, it must take the accusative, while it must take the nominative if it is indefinite. In addition to case, a number of postpositions exist that usually govern the genitive, dative-locative, comitative and privative cases, including a marked form of the nominative (which can itself then take further case forms). There is also a possible attributive case (when a noun is used attributively), which is unmarked in most nouns but takes the suffix ‑ (‑) when the stem has an unstable nasal. Noun

In grammar, a noun is a word that represents a concrete or abstract thing, like living creatures, places, actions, qualities, states of existence, and ideas. A noun may serve as an Object (grammar), object or Subject (grammar), subject within a p ...

s can also take a reflexive-possessive suffix

In linguistics, a suffix is an affix which is placed after the stem of a word. Common examples are case endings, which indicate the grammatical case of nouns and adjectives, and verb endings, which form the conjugation of verbs. Suffixes can ca ...

, indicating that the marked noun is possessed by the subject of the sentence: I friend- save- 'I saved my friend'. However, there are also somewhat noun-like adjective

An adjective (abbreviations, abbreviated ) is a word that describes or defines a noun or noun phrase. Its semantic role is to change information given by the noun.

Traditionally, adjectives are considered one of the main part of speech, parts of ...

s to which case suffixes seemingly cannot be attached directly unless there is ellipsis

The ellipsis (, plural ellipses; from , , ), rendered , alternatively described as suspension points/dots, points/periods of ellipsis, or ellipsis points, or colloquially, dot-dot-dot,. According to Toner it is difficult to establish when t ...

.

:

''The rules governing the morphology of Mongolian case endings are intricate, and so the rules given below are only indicative. In many situations, further (more general) rules must also be taken into account in order to produce the correct form: these include the presence of an unstable nasal or unstable velar, as well as the rules governing when a penultimate vowel should be deleted from the stem with certain case endings (e.g. ' () → ' ()). The additional morphological rules specific to loanwords are not covered.''

Nominative case

The nominative case is used when a noun (or other part of speech acting as one) is the subject of the sentence, and the agent of whatever action (not just physically) takes place in the sentence. In Mongolian, the nominative case does not have an ending.Accusative case

The accusative case is used when a noun acts as a direct object (or just "object"), and receives action from a transitive verb. It is formed by: # ‑ (‑) after stems ending in long vowels or diphthongs, or when a stem ending in () has an unstable velar (unstable g). # ‑ (‑) after back vowel stems ending in unpalatalized consonants (except and ), short vowels (except ) or iotated vowels. # ‑ (‑) after front vowel stems ending in consonants, short vowels or iotated vowels; and after all stems ending in the palatalized consonants (), () and (), as well as (), (), () or (). :''Note: If the stem ends in a short vowel or ' (), it is replaced by the suffix.''Genitive case

The genitive case is used to show possession of something. *For regular stems, it is formed by: *# ‑ (‑) after stems ending in the diphthongs (), (), (), (), () or (), or the long vowel (). *# ‑ (‑) after back vowel stems ending in (). *# ‑ (‑) after front vowel stems ending in (). *# ‑ (‑) after back vowel stems ending in unpalatalized consonants (except , and ), short vowels (except ) or iotated vowels. *# ‑ (‑) after front vowel stems ending in consonants (other than ), short vowels or iotated vowels; and after all stems ending in the palatalized consonants (), () and (), as well as (), (), () or (). *# ‑ (‑) after stems ending in a long vowel (other than ), or after the diphthongs (), () or (). *:''Note: If the stem ends in a short vowel or ' (), it is replaced by the suffix.'' *For stems with an unstable nasal (unstable n), it is formed by: *# ‑ (‑) after back vowel stems (other than those ending in or ). *# ‑ (‑) after front vowel stems (other than those ending in or ). *# ‑ (‑) after back vowel stems ending in () or (). *# ‑ (‑) after front vowel stems ending in () or (). *:''Note: If the stem ends in ' () or ' (), it is replaced by the suffix.'' *For stems with an unstable velar (unstable g), it is formed by ‑ (‑).Dative-locative case

The dative-locative case is used to show the location of something, or to specify that something is in something else. *For regular stems or those with an unstable velar (unstable g), it is formed by: *# ‑ (‑) after stems ending in vowels or the vocalized consonants (), () and (), and a small number of stems ending in () and (). *# ‑ (‑) after stems ending in () and (), most stems ending in () and (), and stems ending in () when it is preceded by a vowel. *# ‑ (‑) after stems ending in the palatalized consonants (), () and (). *# ‑ (‑), ‑ (‑), ‑ (‑) or ‑ (‑) after all other stems (depending on the vowel harmony of the stem). *For stems with an unstable nasal (unstable n), it is formed by: *# ‑ (‑) after stems ending in vowels. *# ‑ (‑) after stems ending in the palatalized consonants (), () and (). *# ‑ (‑), ‑ (‑), ‑ (‑) or ‑ (‑) after all other stems (depending on the vowel harmony of the stem).Plurals

Source:Plural

In many languages, a plural (sometimes list of glossing abbreviations, abbreviated as pl., pl, , or ), is one of the values of the grammatical number, grammatical category of number. The plural of a noun typically denotes a quantity greater than ...

ity may be left unmarked, but there are overt plurality markers, some of which are restricted to humans. A noun that is modified by a numeral usually does not take any plural affix. There are four ways of forming plurals in Mongolian:

# Some plurals are formed by adding - ''-nuud'' or - ''-nüüd''. If the last vowel of the previous word is a (a), o (y), or ɔ (o), then - is used; e.g. ''kharkh'' 'rat' becomes ''kharkhnuud'' 'rats'. If the last vowel of the previous word is e (э), ʊ (ө), ü (ү), or i (и) then is used; e.g. ''nüd'' 'eye' becomes ''nüdnüüd'' 'eyes'.

# In other plurals, just - ''-uud'' or - ''-üüd'' is added without the "n"; e.g. ''khot'' 'city' becomes ''khotuud'' 'cities', and ''eej'' 'mother' becomes ''eejüüd'' 'mothers'.

# Another way of forming plurals is by adding - ''-nar''; e.g. ''bagsh'' 'teacher' becomes ''bagsh nar'' 'teachers'.

# The final way is an irregular form used: ''khün'' 'person' becomes ''khümüüs'' 'people'.

Pronouns

Personal pronoun

Personal pronouns are pronouns that are associated primarily with a particular grammatical person – first person (as ''I''), second person (as ''you''), or third person (as ''he'', ''she'', ''it''). Personal pronouns may also take different f ...

s exist for the first and second person, while the old demonstrative pronouns have come to form third person (proximal and distal) pronouns. Other word (sub-)classes include interrogative pronoun

An interrogative word or question word is a function word used to ask a question, such as ''what, which'', ''when'', ''where'', '' who, whom, whose'', ''why'', ''whether'' and ''how''. They are sometimes called wh-words, because in English most ...

s, conjunctions (which take participles), spatials, and particles

In the physical sciences, a particle (or corpuscle in older texts) is a small localized object which can be described by several physical or chemical properties, such as volume, density, or mass.

They vary greatly in size or quantity, from s ...

, the last being rather numerous.

Negation

Negation

In logic, negation, also called the logical not or logical complement, is an operation (mathematics), operation that takes a Proposition (mathematics), proposition P to another proposition "not P", written \neg P, \mathord P, P^\prime or \over ...

is mostly expressed by ''-güi'' (-) after participles and by the negation particle ''bish'' () after nouns and adjectives; negation particles preceding the verb (for example in converbal constructions) exist, but tend to be replaced by analytical constructions.

Numbers

Forming questions

When asking questions in Mongolian, a question marker is used to show a question is being asked. There are different question markers for yes/no questions and for information questions. For yes/no questions, and are used when the last word ends in a short vowel or a consonant, and their use depends on the vowel harmony of the previous word. When the last word ends in a long vowel or a diphthong, then and are used (again depending on vowel harmony). For information questions (questions asking for information with an interrogative word like who, what, when, where, why, etc.), the question particles are and , depending on the last sound in the previous word. # Yes/No Question Particles - () # Open Ended Question Particles - () Basic interrogative pronouns - ( 'what'), - ( 'where'), ( 'who'), ( 'why'), ( 'how'), ( 'when'), ( 'what kind')Verbs

In Mongolian, verbs have a stem and an ending. For example, the stems , , and are suffixed with , , and respectively: , , and . These are the infinitive or dictionary forms. The present/future tense is formed by adding , , , or to the stem, for example 'I/you/he/she/we/they (will) study'. is the present/future tense verb for 'to be'; likewise, is 'to read', and is 'to see'. The final vowel is barely pronounced and is not pronounced at all if the word after begins with a vowel, so is pronounced 'hello, how are you?'. # Past Tense () # Informed Past Tense (any point in past) () # Informed Past Tense (not long ago) () # Non-Informed Past Tense (generally a slightly to relatively more distant past) () # Present Perfect Tense () # Present Progressive Tense () # (Reflective) Present Progressive Tense () # Simple Present Tense () # Simple Future () # Infinitive ()Negation

There are several ways to form negatives in Mongolian. For example: # () – the negative form of the verb 'to be' ( ) – means 'is/are not'. # - (). This suffix is added to verbs, so ( 'go/will go') becomes ( 'do not go/will not go'). # () is the word for 'no'. # () is used for negative imperatives; e.g. ( 'don't go') # () is the formal version of .Syntax

Differential case marking

Mongolian uses differential case marking, being a regular differential object marking (DOM) language. DOM emerges from a complicated interaction of factors such as referentiality, animacy and topicality. Mongolian also exhibits a specific type of differential subject marking (DSM), in which the subjects of embedded clauses (including adverbial clauses) occur with accusative case.Phrase structure

Thenoun phrase

A noun phrase – or NP or nominal (phrase) – is a phrase that usually has a noun or pronoun as its head, and has the same grammatical functions as a noun. Noun phrases are very common cross-linguistically, and they may be the most frequently ...

has the order: demonstrative pronoun/ numeral, adjective, noun. Attributive sentences precede the whole NP. Titles or occupations of people, low numerals indicating groups, and focus clitics are put behind the head noun. Possessive pronoun

A possessive or ktetic form ( abbreviated or ; from ; ) is a word or grammatical construction indicating a relationship of possession in a broad sense. This can include strict ownership, or a number of other types of relation to a greater or le ...

s (in different forms) may either precede or follow the NP. Examples:

The verbal phrase consists of the predicate in the center, preceded by its complements and by the adverbials modifying it and followed (mainly if the predicate is sentence-final) by modal particles, as in the following example with predicate ''bichsen'':

In this clause the adverbial, ''khelekhgüigeer'' 'without saying o must precede the predicate's complement, ''üüniig'' 'it-' in order to avoid syntactic ambiguity, since ''khelekhgüigeer'' is itself derived from a verb and hence an ''üüniig'' preceding it could be construed as its complement. If the adverbial was an adjective such as ''khurdan'' 'fast', it could optionally immediately precede the predicate. There are also cases in which the adverb must immediately precede the predicate.

For Khalkha, the most complete treatment of the verbal forms is by Luvsanvandan (ed.) (1987). However, the analysis of predication presented here, while valid for Khalkha, is adapted from the description of Khorchin.

Most often, of course, the predicate consists of a verb. However, there are several types of nominal predicative constructions, with or without a copula. Auxiliaries that express direction and aktionsart (among other meanings) can with the assistance of a linking converb occupy the immediate postverbal position; e.g.

The next position is filled by converb suffixes in connection with the auxiliary, ''baj-'' 'to be', e.g.

Suffixes occupying this position express grammatical aspect

In linguistics, aspect is a grammatical category that expresses how a verbal action, event, or state, extends over time. For instance, perfective aspect is used in referring to an event conceived as bounded and unitary, without reference t ...

; e.g. progressive and resultative

In linguistics, a resultative (list of glossing abbreviations, abbreviated ) is a form that expresses that something or someone has undergone a change in state as the result of the completion of an event. Resultatives appear as Predicate (grammar) ...

. In the next position, participles followed by ''baj-'' may follow, e.g.,

Here, an explicit perfect and habituality can be marked, which is aspectual in meaning as well. This position may be occupied by multiple suffixes in a single predication, and it can still be followed by a converbal Progressive. The last position is occupied by suffixes that express tense, evidentiality, modality, and aspect.

Clauses

Unmarked phrase order is subject– object–predicate. While the predicate generally has to remain in clause-final position, the other phrases are free to change order or to wholly disappear. The topic tends to be placed clause-initially, new information rather at the end of the clause. Topic can be overtly marked with ''bol'', which can also mark contrastive focus, overt additive focus ('even, also') can be marked with the clitic ''ch'', and overt restrictive focus with the clitic ''l'' ('only'). The inventory of voices in Mongolian consists of passive, causative, reciprocal, plurative, and cooperative. In a passive sentence, the verb takes the suffix -''gd''- and the agent takes either dative or instrumental case, the first of which is more common. In the causative, the verb takes the suffix -''uul''-, the causee (the person caused to do something) in a transitive action (e.g. 'raise') takes dative or instrumental case, and the causee in an intransitive action (e.g. 'rise') takes accusative case. Causative morphology is also used in some passive contexts: The semantic attribute of animacy is syntactically important: thus the sentence, 'the bread was eaten by me', which is acceptable in English, would not be acceptable in Mongolian. The reciprocal voice is marked by -''ld''-, the plurative by -''cgaa''-, and the cooperative by -''lc''-. Mongolian allows for adjectival depictives that relate to either the subject or the direct object, e.g. ''Liena nücgen untdag'' 'Lena sleeps naked', while adjectival resultatives are marginal.Complex sentences

One way to conjoin clauses is to have the first clause end in a converb, as in the following example using the converb ''-bol'': Some verbal nouns in the dative (or less often in the instrumental) function very similar to converbs: e.g. replacing ''olbol'' in the preceding sentence with ''olohod'' find- yields 'when we find it we'll give it to you'. Quite often, postpositions govern complete clauses. In contrast, conjunctions take verbal nouns without case: Finally, there is a class of particles, usually clause-initial, that are distinct from conjunctions but that also relate clauses: Mongolian has acomplementizer

In linguistics (especially generative grammar), a complementizer or complementiser (list of glossing abbreviations, glossing abbreviation: ) is a functional category (part of speech) that includes those words that can be used to turn a clause in ...

auxiliary verb

An auxiliary verb ( abbreviated ) is a verb that adds functional or grammatical meaning to the clause in which it occurs, so as to express tense, aspect, modality, voice, emphasis, etc. Auxiliary verbs usually accompany an infinitive verb or ...

''ge''- very similar to Japanese ''to iu''. ''ge''- literally means 'to say' and in converbal form ''gej'' precedes either a psych verb or a verb of saying. As a verbal noun like ''gedeg'' (with ''ni'') it can form a subset of complement clauses. As ''gene'' it may function as an evidentialis marker.

Mongolian clauses tend to be combined paratactically, which sometimes gives rise to sentence structures which are subordinative despite resembling coordinative structures in European languages:

In the subordinate clause the subject, if different from the subject of main clause, sometimes has to take accusative or genitive case. There is marginal occurrence of subjects taking ablative case as well. Subjects of attributive clauses in which the head has a function (as is the case for all English relative clause

A relative clause is a clause that modifies a noun or noun phrase and uses some grammatical device to indicate that one of the arguments in the relative clause refers to the noun or noun phrase. For example, in the sentence ''I met a man who wasn ...

s) usually require that if the subject is not the head

A head is the part of an organism which usually includes the ears, brain, forehead, cheeks, chin, eyes, nose, and mouth, each of which aid in various sensory functions such as sight, hearing, smell, and taste. Some very simple ani ...

, then it take the genitive, e.g. ''tüünii idsen hool'' that.one- eat- meal 'the meal that s/he had eaten'.

Loanwords and coined words

Mongolian first adoptedloanword

A loanword (also a loan word, loan-word) is a word at least partly assimilated from one language (the donor language) into another language (the recipient or target language), through the process of borrowing. Borrowing is a metaphorical term t ...

s from many languages including Old Turkic

Old Siberian Turkic, generally known as East Old Turkic and often shortened to Old Turkic, was a Siberian Turkic language spoken around East Turkistan and Mongolia. It was first discovered in inscriptions originating from the Second Turkic Kh ...

, Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; stem form ; nominal singular , ,) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in northwest South Asia after its predecessor languages had Trans-cultural ...

(these often via Uyghur), Persian, Tibetan, Tungusic, and Chinese. However, more recent loanwords come from Russian, English, and Mandarin Chinese

Mandarin ( ; zh, s=, t=, p=Guānhuà, l=Mandarin (bureaucrat), officials' speech) is the largest branch of the Sinitic languages. Mandarin varieties are spoken by 70 percent of all Chinese speakers over a large geographical area that stretch ...

(mainly in Inner Mongolia). Language commissions of the Mongolian state continuously translate new terminology

Terminology is a group of specialized words and respective meanings in a particular field, and also the study of such terms and their use; the latter meaning is also known as terminology science. A ''term'' is a word, Compound (linguistics), com ...

into Mongolian, so as the Mongolian vocabulary now has 'president' ('generalizer') and 'beer' ('yellow kumys'). There are several loan translations, e.g. 'train' ('fire cart') from Chinese ( 'fire cart') 'train'. Other loan translations include 'essence' from Chinese ( 'true quality'), 'population' from Chinese ( 'person mouth'), 'corn, maize' from Chinese ( 'jade rice') and 'republic' from Chinese ( 'public collaboration nation').

* Sanskrit loanwords include ( 'religion'), ( 'space'), ( 'talent'), ( 'good deeds'), ( 'instant'), ( 'continent'), ( 'planet'), ( 'tales, stories'), ( 'poems, verses'), ( 'strophe'), ( 'mineral water, nectar'), ( 'chronicle'), ( ' Mercury'), ( 'Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is often called Earth's "twin" or "sister" planet for having almost the same size and mass, and the closest orbit to Earth's. While both are rocky planets, Venus has an atmosphere much thicker ...

'), ( 'Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the List of Solar System objects by size, largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a Jupiter mass, mass more than 2.5 times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined a ...

'), and ( 'Saturn

Saturn is the sixth planet from the Sun and the second largest in the Solar System, after Jupiter. It is a gas giant, with an average radius of about 9 times that of Earth. It has an eighth the average density of Earth, but is over 95 tim ...

').

* Persian loanwords include ( 'amethyst'), ( 'brandy'), ( 'building'), ( 'tiger'), ( 'chess queen; female tiger'), ( 'steel'), ( 'crystal'), ( 'sesame'), ( 'prison'), ( 'powder/gunpowder; medicine'), ( 'telescope'), ( 'telescope/microscope'), ( 'notebook'), ( 'high God'), ( 'soap'), ( 'stool'), and ( 'cup').

* Chinese loanwords include ( ''bǎnzi'' 'board'), ( ''là'' 'candle'), ( ''luóbo'' 'radish'), ( ''húlu'' 'gourd'), ( ''dēnglù'' 'lamp'), ( ''qìdēng'' 'electric lamp'), ( ''bǐr'' 'paintbrush'), ( ''zhǎnbǎnzi'' 'cutting board'), ( ''qīngjiāo'' 'pepper'), ( ''jiǔcài'' 'leek'), ( ''mógu'' 'mushroom'), ( ''cù'' 'vinegar, soy sauce'), ( ''báicài'' 'cabbage'), ( ''mántóu'' 'steamed bun'), ( ''mǎimài'' 'trade'), ( ''gùamiàn'' 'noodles'), ( ''dān'' 'single'), ( ''gāng'' 'steel'), ( ''lángtóu'' 'sledgehammer'), ( ''chūanghu'' 'window'), ( ''bāozi'' 'dumplings'), ( ''hǔoshāor'' 'fried dumpling'), ( ''rǔzhītāng'' 'cream soup'), ( ''fěntāng'' 'flour soup'), ( ''jiàng'' 'soy'), ( ''wáng'' 'king'), ( ''gōngzhǔ'' 'princess'), ( ''gōng'' 'duke'), ( ''jiāngjūn'' 'general'), ( ''tàijiàn'' 'eunuch'), ( ''piànzi'' 'recorded disc'), ( ''guǎnzi'' 'restaurant'), ( ''liánhuā'' 'lotus'), ( ''huār'' 'flower'), ( ''táor'' 'peach'), ( ''yīngtáor'' 'cherry'), ( ''jiè'' 'to borrow, to lend'), ( ''wāndòu'' 'pea'), ( ''yàngzi'' 'manner, appearance'), ( ''xìngzhì'' 'characteristic'), ( ''lír'' 'pear'), ( ''páizi'' 'target'), ( ''jīn'' 'weight'), ( ''bǐng'' 'pancake'), ( ''huángli'' 'calendar'), ( ''shāocí'' 'porcelain'), ( ''kǎndōudu'' 'sleeveless vest'), ( ''fěntiáozi'' 'potato noodles'), and ( ''chá'' 'tea').

In the 20th century, many Russian loanwords entered the Mongolian language, including 'doctor', 'chocolate', 'train wagon', 'calendar', 'system', (from 'T-shirt'), and 'car'.

In more recent times, due to socio-political reforms, Mongolian has loaned various words from English; some of which have gradually evolved as official terms: 'management', 'computer', 'file', 'marketing', 'credit', 'online', and 'message'. Most of these are confined to the Mongolian state.

In turn, other languages have borrowed words from Mongolian. Examples (Mongolian in brackets) include Persian کشيكچى (from 'royal guard'), (from 'pheasant'), (from 'iron armour'), (from 'chief of commandant'), (from 'scissors'); Uzbek (from 'island'); Chinese 衚衕 ''hutong'' (from 'passageway'), 站赤 ''zhanchi'' (from 'courier/post station'); Middle Chinese

Middle Chinese (formerly known as Ancient Chinese) or the Qieyun system (QYS) is the historical variety of Chinese language, Chinese recorded in the ''Qieyun'', a rime dictionary first published in 601 and followed by several revised and expande ...

犢 ''duk'' (from 'calf'); Korean (from 'royal meal'), (from 'castrated animal'), (from 'chest of an animal'); Old English

Old English ( or , or ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. It developed from the languages brought to Great Britain by Anglo-S ...

''cocer'' (from 'container'); Old French

Old French (, , ; ) was the language spoken in most of the northern half of France approximately between the late 8th -4; we might wonder whether there's a point at which it's appropriate to talk of the beginnings of French, that is, when it wa ...

''quivre'' (from 'container'); Old High German ''Baldrian'' (from 'valerian plant'). ''Köküür'' and ''balchirgan-a'' are thought to have been brought to Europe by the Huns or Pannonian Avars.

Despite having a diverse range of loanwords, Mongolian dialects such as Khalkha and Khorchin, within a comparative vocabulary of 452 words of Common Mongolic vocabulary, retain as many as 95% of these native words, contrasting e.g. with Southern Mongolic languages at 39–77% retentions.

Writing systems

Mongolian has been written in a variety of alphabets, making it a language with one of the largest number of scripts used historically. The earliest stages of Mongolian (

Mongolian has been written in a variety of alphabets, making it a language with one of the largest number of scripts used historically. The earliest stages of Mongolian (Xianbei

The Xianbei (; ) were an ancient nomadic people that once resided in the eastern Eurasian steppes in what is today Mongolia, Inner Mongolia, and Northeastern China. The Xianbei were likely not of a single ethnicity, but rather a multiling ...

, Wuhuan

The Wuhuan (, < Eastern Han Chinese: *''ʔɑ-ɣuɑn'', <

Khitan large script adopted in 920 CE is an early Mongol (or according to some, para-Mongolic) script.

The traditional

Literacy country study: Mongolia

. Background paper prepared for the Education for All Global Monitoring Report 2006. Literacy for Life. P.7-8 Earlier government campaigns to eradicate illiteracy, employing the traditional script, had only managed to raise literacy from 3.0% to 17.3% between 1921 and 1940. From 1991 to 1994, an attempt at reintroducing the traditional alphabet failed in the face of popular resistance. In informal contexts of electronic text production, the use of the Latin alphabet is common. In the

''Some library catalogs write Chinese language titles with each syllable separate, even syllables belonging to a single word.'' ; List of abbreviations used ''TULIP'' is in official use by some librarians; the remainder have been contrived for this listing. :; Journals :* ''KULIP'' = ''Kyūshū daigaku gengogaku ronshū'' yushu University linguistics papers:* ''MKDKH'' = ''Muroran kōgyō daigaku kenkyū hōkoku'' emoirs of the Muroran Institute of Technology:* ''TULIP'' = ''Tōkyō daigaku gengogaku ronshū'' okyo University linguistics papers:; Publishers :* ÖMAKQ = Öbür mongγul-un arad-un keblel-ün qoriy-a :* ÖMSKKQ = Öbür mongγul-un surγan kümüǰil-ün keblel-ün qoriy-a :* ÖMYSKQ = Öbür mongγul-un yeke surγaγuli-yin keblel-ün qoriy-a :* ŠUA = ongol UlsynŠinžleh Uhaany Akademi * Amaržargal, B. 1988. ''BNMAU dah' Mongol helnij nutgijn ajalguuny tol' bichig: halh ajalguu''. Ulaanbaatar: ŠUA. * Apatóczky, Ákos Bertalan. 2005. On the problem of the subject markers of the Mongolian language. In Wú Xīnyīng, Chén Gānglóng (eds.), ''Miànxiàng xīn shìjìde ménggǔxué'' he Mongolian studies in the new century : review and prospect Běijīng: Mínzú Chūbǎnshè. 334–343. . * Ashimura, Takashi. 2002. Mongorugo jarōto gengo no no yōhō ni tsuite. ''TULIP'', 21: 147–200. * Bajansan, Ž. and Š. Odontör. 1995. ''Hel šinžlelijn ner tom"joony züjlčilsen tajlbar toli''. Ulaanbaatar. * Bayančoγtu. 2002. ''Qorčin aman ayalγun-u sudulul''. Kökeqota: ÖMYSKQ. . * Bjambasan, P. 2001. Mongol helnij ügüjsgeh har'caa ilerhijleh hereglüürüüd. ''Mongol hel, sojolijn surguul: Erdem šinžilgeenij bičig'', 18: 9–20. * Bosson, James E. 1964. ''Modern Mongolian; a primer and reader''. Uralic and Altaic series; 38. Bloomington: Indiana University. * Brosig, Benjamin. 2009. Depictives and resultatives in Modern Khalkh Mongolian. ''Hokkaidō gengo bunka kenkyū'', 7: 71–101. * Chuluu, Ujiyediin. 1998

''Studies on Mongolian verb morphology''

. Dissertation, University of Toronto. * Činggeltei. 1999. ''Odu üj-e-jin mongγul kelen-ü ǰüi''. Kökeqota: ÖMAKQ. . * Coloo, Ž. 1988. ''BNMAU dah' mongol helnij nutgijn ajalguuny tol' bichig: ojrd ajalguu''. Ulaanbaatar: ŠUA. * Djahukyan, Gevork. (1991). Armenian Lexicography. In Franz Josef Hausmann (Ed.), ''An International Encyclopedia of Lexicography'' (pp. 2367–2371). Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. * obuDàobù. 1983. ''Ménggǔyǔ jiǎnzhì. Běijīng: Mínzú.'' * Garudi. 2002. ''Dumdadu üy-e-yin mongγul kelen-ü bütüče-yin kelberi-yin sudulul''. Kökeqota: ÖMAKQ. * Georg, Stefan, Peter A. Michalove, Alexis Manaster Ramer, Paul J. Sidwell. 1999. Telling general linguists about Altaic. ''Journal of Linguistics'', 35: 65–98. * Guntsetseg, D. 2008

Differential Object Marking in Mongolian

''Working Papers of the SFB 732 Incremental Specification in Context'', 1: 53–69. * Hammar, Lucia B. 1983. ''Syntactic and pragmatic options in Mongolian – a study of'' bol ''and'' n' . Ph.D. Thesis. Bloomington: Indiana University.

* ökeHarnud, Huhe. 2003. ''A Basic Study of Mongolian Prosody''. Helsinki: Publications of the Department of Phonetics, University of Helsinki. Series A; 45. Dissertation. .

* Hashimoto, Kunihiko. 1993. <-san> no imiron. ''MKDKH'', 43: 49–94. Sapporo: Dō daigaku.

* Hashimoto, Kunihiko. 2004

Mongorugo no kopyura kōbun no imi no ruikei