Monarchy Of Rhodesia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Queen of Rhodesia was the title asserted for

File:Rhodesia ten shillings 1968.jpg, Ten shillings

File:Rhodesia one pound 1968.jpg, One pound

File:Rhodesia five pounds 1966.jpg, Five pounds

Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until her death in 2022. She was queen regnant of 32 sovereign states during ...

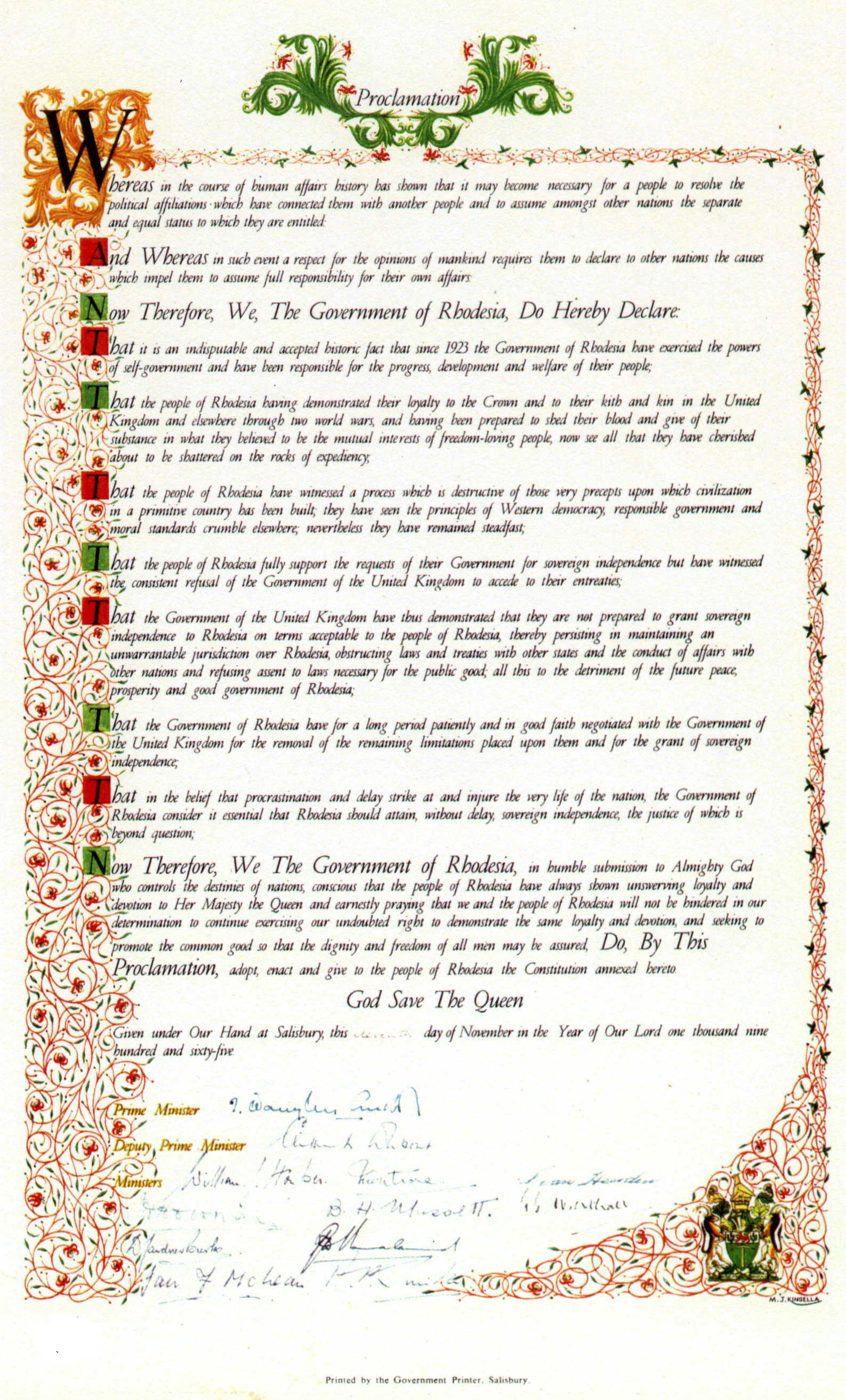

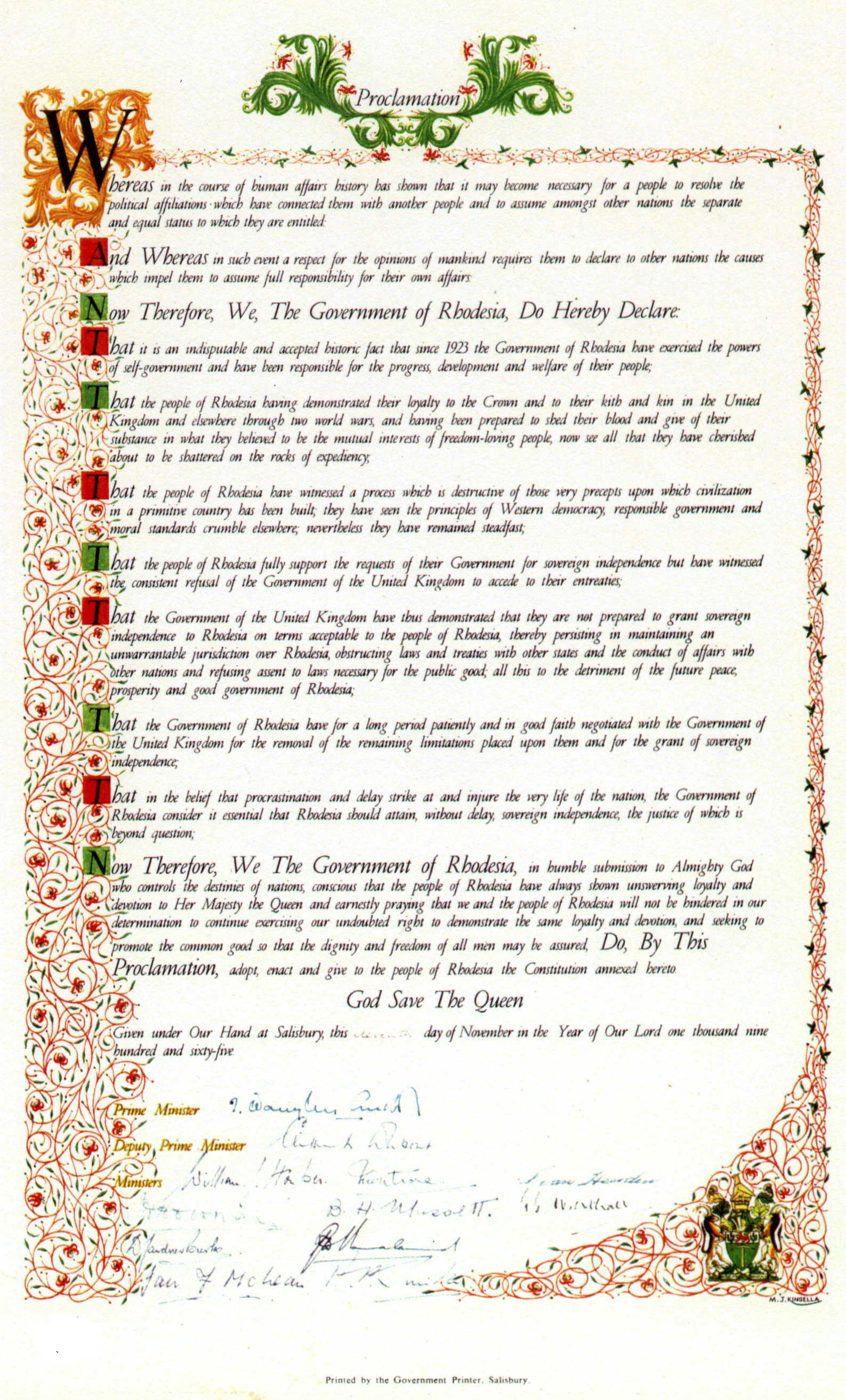

as Rhodesia's constitutional head of state following the country's Unilateral Declaration of Independence

A unilateral declaration of independence (UDI) is a formal process leading to the establishment of a new state by a subnational entity which declares itself independent and sovereign without a formal agreement with the state which it is secedi ...

from the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

. However, the position only existed under the Rhodesian constitution of 1965 and remained unrecognised elsewhere in the world. The British government, along with the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmonizi ...

and almost all governments, regarded the declaration of independence as an illegal act and nowhere else was the existence of the British monarch having separate status in Rhodesia accepted. With Rhodesia becoming a republic in 1970, the status or existence of the office ceased to be contestable.

History

Southern Rhodesia

Southern Rhodesia was a landlocked self-governing British Crown colony in southern Africa, established in 1923 and consisting of British South Africa Company (BSAC) territories lying south of the Zambezi River. The region was informally k ...

had been a crown colony with responsible government

Responsible government is a conception of a system of government that embodies the principle of parliamentary accountability, the foundation of the Westminster system of parliamentary democracy. Governments (the equivalent of the executive bra ...

since 1923 and the transfer from rule under the British South Africa Company

The British South Africa Company (BSAC or BSACo) was chartered in 1889 following the amalgamation of Cecil Rhodes' Central Search Association and the London-based Exploring Company Ltd, which had originally competed to capitalize on the expect ...

. The monarch of the United Kingdom was automatically recognised as monarch in the colonies. Following the UK refusing to grant Southern Rhodesia independence under minority rule, on 11 November 1965, they unilaterally declared independence and declared Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until her death in 2022. She was queen regnant of 32 sovereign states during ...

as the queen of Rhodesia. The independence declaration clarified that they were only breaking from the British government and affirmed loyalty to Elizabeth, viewing her as the separate Rhodesian monarch as part of a "loyal rebellion". All Rhodesian oaths continued to be taken to her and the declaration of independence ended with "God Save The Queen".

In response, the British Parliament

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the Parliamentary sovereignty in the United Kingdom, supreme Legislature, legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of We ...

passed the Southern Rhodesia Act 1965 which ''de jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' ( ; , "by law") describes practices that are legally recognized, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. In contrast, ("in fact") describes situations that exist in reality, even if not legall ...

'' affirmed British control of the colony and granted Queen Elizabeth II the power to act in the colony. She then issued an order in council to suspend the constitution and sacked the Rhodesian Front

The Rhodesian Front was a right-wing conservative political party in Southern Rhodesia, subsequently known as Rhodesia. It was the last ruling party of Southern Rhodesia prior to that country's unilateral declaration of independence, and the ru ...

government. These were ignored in Rhodesia and Prime Minister Ian Smith

Ian Douglas Smith (8 April 1919 – 20 November 2007) was a Rhodesian politician, farmer, and fighter pilot who served as Prime Minister of Rhodesia (known as Southern Rhodesia until October 1964 and now known as Zimbabwe) from 1964 to ...

claimed it was the act of the British government and not of the Queen. The Rhodesian theory believed in the divisibility of the Crown

The Crown is the state in all its aspects within the jurisprudence of the Commonwealth realms and their subdivisions (such as the Crown Dependencies, overseas territories, provinces, or states). Legally ill-defined, the term has differen ...

to show their political autonomy. The Rhodesians also ceased to recognise the governor of Southern Rhodesia

The Governor of Southern Rhodesia was the representative of the British monarch in the self-governing colony of Southern Rhodesia from 1923 to 1980. The Governor was appointed by The Crown and acted as the local head of state, receiving instruct ...

, Sir Humphrey Gibbs, as the representative of the Queen and asked him to move out of Government House, Salisbury (which Gibbs refused to do). Smith then asked Queen Elizabeth II to appoint a governor-general of Rhodesia to act on her behalf, but she refused as she did not recognise the title and treated the request as if it had come from an ordinary citizen as Smith was no longer recognised as prime minister. Elizabeth issued a response via Gibbs that said: "Her Majesty is not able to entertain purported advice of this kind and has therefore been pleased to direct that no action should be taken upon it".

Accordingly Smith appointed Clifford Dupont

Clifford Walter Dupont, GCLM, ID (6 December 1905 – 28 June 1978) was a British-born Rhodesian politician who served in the internationally unrecognised positions of officer administrating the government (from 1965 until 1970) and president ( ...

as Officer Administering the Government in place of any royal appointment. It was initially suggested by Rhodesian officials that, due to his Stuart

Stuart may refer to:

Names

* Stuart (name), a given name and surname (and list of people with the name) Automobile

*Stuart (automobile)

Places

Australia Generally

*Stuart Highway, connecting South Australia and the Northern Territory

Northe ...

ancestry, they would appoint the Duke of Montrose

Duke of Montrose (named for Montrose, Angus) is a title that has been created twice in the Peerage of Scotland. The title was created anew in 1707, for James Graham, 4th Marquess of Montrose, great-grandson of famed James Graham, 1st Marques ...

as regent

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state ''pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy, ...

until Queen Elizabeth II recognised the title. The suggestion was rejected as a violation of the Regency Act 1953. On the British side, the diplomat Michael Palliser suggested that Queen Elizabeth II appoint her husband Prince Philip

Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh (born Prince Philip of Greece and Denmark, later Philip Mountbatten; 10 June 1921 – 9 April 2021) was the husband of Queen Elizabeth II. As such, he served as the consort of the British monarch from El ...

as governor-general and have him arrive with a detachment of Coldstream Guards

The Coldstream Guards is the oldest continuously serving regular regiment in the British Army. As part of the Household Division, one of its principal roles is the protection of the monarchy; due to this, it often participates in state ceremoni ...

to legally sack Smith and the Rhodesian Front. However the plan was not feasible due to bringing the royal family into politics and the risk that Philip would have been in.

Power

The monarch's powers were the same as prior to theUnilateral Declaration of Independence

A unilateral declaration of independence (UDI) is a formal process leading to the establishment of a new state by a subnational entity which declares itself independent and sovereign without a formal agreement with the state which it is secedi ...

. However they were ''de facto'' exercised by the Officer Administering the Government (Clifford Dupont

Clifford Walter Dupont, GCLM, ID (6 December 1905 – 28 June 1978) was a British-born Rhodesian politician who served in the internationally unrecognised positions of officer administrating the government (from 1965 until 1970) and president ( ...

) rather than by the governor of Southern Rhodesia (Sir Humphrey Gibbs

Sir Humphrey Vicary Gibbs, (22 November 19025 November 1990), was the penultimate Governor of the colony of Southern Rhodesia, from 24 October 1964 simply Rhodesia, who served until, and opposed, the Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI ...

) as Queen Elizabeth II's ''de jure'' representative. Every Rhodesian Bill presented to the Officer Administering the Government, had the following words of enactment

An enacting clause is a short phrase that introduces the main provisions of a law enacted by a legislature. It is also called enacting formula or enacting words. It usually declares the source from which the law claims to derive its authority. In ...

:

In 1968, she commuted the sentence of three African men sentenced to death. Her pardon was ignored as the High Court of Rhodesia

High may refer to:

Science and technology

* Height

* High (atmospheric), a high-pressure area

* High (computability), a quality of a Turing degree, in computability theory

* High (tectonics), in geology an area where relative tectonic uplift to ...

ruled that, as Rhodesian officials had not been consulted, the pardon came from the orders of the British government rather than from the Queen of Rhodesia, and the men were executed.

Symbols

The Queen's portrait featured on Rhodesian banknotes and coins, as well as on postage stamps.Abolition

There had been calls for Rhodesia to become a republic as early as 1966. The Whaley Commission had been set up by the Rhodesian government in 1967 to review the constitution and recommendations for alterations. After Queen Elizabeth II's pardon was ignored, the Rhodesian government announced that theQueen's Official Birthday

The King's Official Birthday (alternatively the Queen's Official Birthday when the monarch is female) is the selected day in the United Kingdom and most Commonwealth realms on which the birthday of the monarch is officially celebrated in those ...

would no longer be a public holiday and they would only fire a 21-gun salute on her actual birthday.

The Rhodesian Front published the Whaley Report's proposals for a referendum to abolish the monarchy and establish a republic with a new constitution a month after the executions. Smith argued for it on the grounds that the British government "had denied us the Queen of Rhodesia". In the 1969 Rhodesian constitutional referendum

A double referendum was held in Rhodesia on 20 June 1969, in which voters were asked whether they were in favour of or against a) the adoption of a republican form of government, and b) the proposals for a new Constitution, as set out in a white ...

, the Rhodesian electorate voted in favour of the establishment of a republic. The move was opposed by the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

over fears it would lead to further marginalisation of blacks in Rhodesia. Gibbs also resigned as Governor at this time. The internationally unrecognised republic was declared on 2 March 1970. Queen Elizabeth II formally revoked the royal titles of the Royal Rhodesian Air Force

The Rhodesian Air Force (RhAF) was an air force based in Salisbury (now Harare) which represented several entities under various names between 1935 and 1980: originally serving the British self-governing colony of Southern Rhodesia, it was the ...

and Royal Rhodesia Regiment. Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother

Elizabeth Angela Marguerite Bowes-Lyon (4 August 1900 – 30 March 2002) was Queen of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 to 6 February 1952 as the wife of King George VI. She was th ...

's honorary commissionership of the British South Africa Police

The British South Africa Police (BSAP) was, for most of its existence, the police force of Rhodesia (renamed Zimbabwe in 1980). It was formed as a paramilitary force of mounted infantrymen in 1889 by Cecil Rhodes' British South Africa Company, from ...

was also suspended. Dupont replaced Elizabeth II as head of state in Rhodesia as the new president

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese f ...

.

Contrary to Smith's hope that such a move would bring international legitimacy, it had the opposite effect. All countries that had relations with Rhodesia, except Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, In recognized minority languages of Portugal:

:* mwl, República Pertuesa is a country located on the Iberian Peninsula, in Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Macaronesian ...

and South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring count ...

, withdrew their diplomatic missions from the country. This was because originally they maintained relations because of the pre-existing royal accreditation but because a republic had been declared, that rationale was no longer valid.

Rhodesia remained an unrecognised republic until Zimbabwe Rhodesia

Zimbabwe Rhodesia (), alternatively known as Zimbabwe-Rhodesia, also informally known as Zimbabwe or Rhodesia, and sometimes as Rhobabwe, was a short-lived sovereign state that existed from 1 June to 12 December 1979. Zimbabwe Rhodesia was p ...

agreed to return to colonial status. Queen Elizabeth II resumed monarchical duties over the colony through her role as Queen of the United Kingdom and appointed Lord Soames as her representative as Governor of Southern Rhodesia until its independence as Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe (), officially the Republic of Zimbabwe, is a landlocked country located in Southeast Africa, between the Zambezi and Limpopo Rivers, bordered by South Africa to the south, Botswana to the south-west, Zambia to the north, and Mozam ...

on 18 April 1980.

References

{{Elizabeth II Rhodesia Elizabeth II National symbols of Rhodesia Politics of Rhodesia 1965 establishments in Rhodesia 1970 disestablishments in Rhodesia History of RhodesiaRhodesia

Rhodesia (, ), officially from 1970 the Republic of Rhodesia, was an unrecognised state in Southern Africa from 1965 to 1979, equivalent in territory to modern Zimbabwe. Rhodesia was the ''de facto'' Succession of states, successor state to th ...

Former monarchies of Africa

History of the British Empire

History of the Commonwealth of Nations

Titles held only by one person

Zimbabwe and the Commonwealth of Nations