The doctrine of the

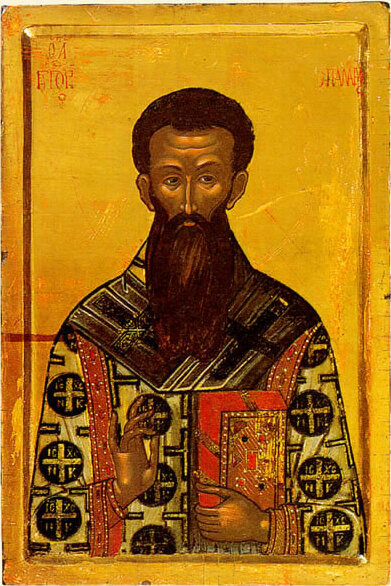

Trinity

The Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the Christian doctrine concerning the nature of God, which defines one God existing in three, , consubstantial divine persons: God the Father, God the Son (Jesus Christ) and God the Holy Spirit, thr ...

, considered the core of

Christian theology

Christian theology is the theology – the systematic study of the divine and religion – of Christianity, Christian belief and practice. It concentrates primarily upon the texts of the Old Testament and of the New Testament, as well as on Ch ...

by ''Trinitarians'', is the result of continuous exploration by the church of the

biblical data, thrashed out in debate and treatises, eventually formulated at the

First Council of Nicaea

The First Council of Nicaea ( ; ) was a council of Christian bishops convened in the Bithynian city of Nicaea (now İznik, Turkey) by the Roman Emperor Constantine I. The Council of Nicaea met from May until the end of July 325.

This ec ...

in AD 325 in a way they believe is consistent with the biblical witness, and further refined in

later councils and writings.

[Oxford Dictionary of the Bible, Trinity Article] The most widely recognized Biblical foundations for the doctrine's formulation are in the

Gospel of John

The Gospel of John () is the fourth of the New Testament's four canonical Gospels. It contains a highly schematic account of the ministry of Jesus, with seven "Book of Signs, signs" culminating in the raising of Lazarus (foreshadowing the ...

,

which possess ideas reflected in

Platonism

Platonism is the philosophy of Plato and philosophical systems closely derived from it, though contemporary Platonists do not necessarily accept all doctrines of Plato. Platonism has had a profound effect on Western thought. At the most fundam ...

and Greek philosophy.

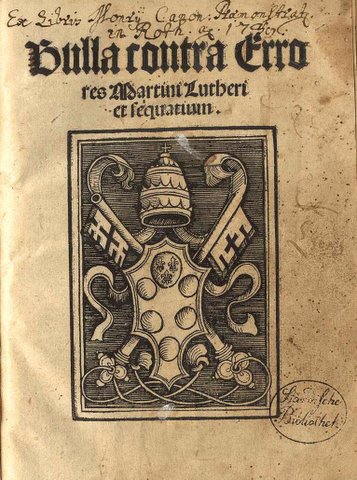

Nontrinitarianism

Nontrinitarianism is a form of Christianity that rejects the orthodox Christian theology of the Trinity—the belief that God is three distinct hypostases or persons who are coeternal, coequal, and indivisibly united in one being, or essence ( ...

is any of several Christian beliefs that reject the Trinitarian

doctrine

Doctrine (from , meaning 'teaching, instruction') is a codification (law), codification of beliefs or a body of teacher, teachings or instructions, taught principles or positions, as the essence of teachings in a given branch of knowledge or in a ...

that God is three distinct persons in one being. Modern nontrinitarian groups views differ widely on the

nature of God,

Jesus

Jesus (AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, and many Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament, other names and titles, was a 1st-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the Jesus in Chris ...

, and the

Holy Spirit

The Holy Spirit, otherwise known as the Holy Ghost, is a concept within the Abrahamic religions. In Judaism, the Holy Spirit is understood as the divine quality or force of God manifesting in the world, particularly in acts of prophecy, creati ...

.

Historical theology

Historical theology is the study of the history of Christian doctrine. Alister McGrath defines historical theology as 'the branch of theological inquiry which aims to explore the historical development of Christian doctrines, and identify the fa ...

is the academic study of the development of Christian theology.

Background

Second Temple Judaism

Christianity originated as a sect within Second Temple Judaism (516BC – AD70). Judaism's sacred scripture is the

Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;["Tanach"](_blank)

. '' Old Testament

The Old Testament (OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible, or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew and occasionally Aramaic writings by the Isr ...

. The Hebrew Bible is divided into three parts: the

Torah

The Torah ( , "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. The Torah is also known as the Pentateuch () ...

("Law"), the

Nevi'im

The (; ) is the second major division of the Hebrew Bible (the ''Tanakh''), lying between the () and (). The Nevi'im are divided into two groups. The Former Prophets ( ) consists of the narrative books of Joshua, Judges, Samuel and Kings ...

("Prophets") and the

Ketuvim

The (; ) is the third and final section of the Hebrew Bible, after the ("instruction") and the "Prophets". In English translations of the Hebrew Bible, this section is usually titled "Writings" or "Hagiographa".

In the Ketuvim, 1–2 Books ...

("Writings"). The central belief of Judaism is

monotheism

Monotheism is the belief that one God is the only, or at least the dominant deity.F. L. Cross, Cross, F.L.; Livingstone, E.A., eds. (1974). "Monotheism". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (2 ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. A ...

: there is one

God

In monotheistic belief systems, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. In polytheistic belief systems, a god is "a spirit or being believed to have created, or for controlling some part of the un ...

named

Yahweh

Yahweh was an Ancient Semitic religion, ancient Semitic deity of Weather god, weather and List of war deities, war in the History of the ancient Levant, ancient Levant, the national god of the kingdoms of Kingdom of Judah, Judah and Kingdom ...

(

Deuteronomy 6:4,

Isaiah 44

Isaiah 44 is the forty-fourth chapter of the Book of Isaiah in the Hebrew Bible or the Old Testament of the Christian Bible. This book contains the prophecies attributed to the prophet Isaiah, and is a part of the Books of the Prophets.

Text ...

:6).

Israel

According to the Bible, God promised

Abraham

Abraham (originally Abram) is the common Hebrews, Hebrew Patriarchs (Bible), patriarch of the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. In Judaism, he is the founding father who began the Covenant (biblical), covenanta ...

, the

Jewish patriarch, that his descendants would become a great nation and a blessing to all the earth (

Genesis 12

Lech-Lecha, Lekh-Lekha, or Lech-L'cha ( ''leḵ-ləḵā''—Hebrew for "go!" or "leave!", literally "go for you"—the fifth and sixth words in the parashah) is the third weekly Torah portion (, ''parashah'') in the annual Jewish cycle of To ...

:3). Therefore, the

Jews were a chosen people (

Deuteronomy 7

Deuteronomy (; ) is the fifth book of the Torah (in Judaism), where it is called () which makes it the fifth book of the Hebrew Bible and Christian Old Testament.

Chapters 1–30 of the book consist of three sermons or speeches delivered to ...

:6–8) bound by a

covenant

Covenant may refer to:

Religion

* Covenant (religion), a formal alliance or agreement made by God with a religious community or with humanity in general

** Covenant (biblical), in the Hebrew Bible

** Covenant in Mormonism, a sacred agreement b ...

with God. God's election placed certain obligations on the Jewish people, and these () were found in the Torah. They were to love Yahweh with all their hearts and worship no other gods (

Deuteronomy 6

Va'etchanan (—Hebrew language, Hebrew for "and I will plead," the Incipit, first word in the parashah) is the 45th weekly Torah portion (, ''parashah'') in the annual Judaism, Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the second in the Book of Deuterono ...

:4–5). Likewise, they were commanded to love one another (

Leviticus 19

Leviticus 19 is the nineteenth chapter of the Book of Leviticus in the Hebrew Bible or the Old Testament of the Christian Bible. It contains laws on a variety of topics, and is attributed by tradition to Moses.See page 239 in Carmichael, Calum M. ...

:18). In addition, they were to observe the

Sabbath

In Abrahamic religions, the Sabbath () or Shabbat (from Hebrew ) is a day set aside for rest and worship. According to the Book of Exodus, the Sabbath is a day of rest on the seventh day, Ten Commandments, commanded by God to be kept as a Holid ...

, follow

kosher

(also or , ) is a set of dietary laws dealing with the foods that Jewish people are permitted to eat and how those foods must be prepared according to Jewish law. Food that may be consumed is deemed kosher ( in English, ), from the Ashke ...

food laws, and

circumcise

Circumcision is a procedure that removes the foreskin from the human penis. In the most common form of the operation, the foreskin is extended with forceps, then a circumcision device may be placed, after which the foreskin is excised. T ...

their sons. By obeying the commandments, Israel would be a holy nation, reflecting God's

holiness

Sacred describes something that is dedicated or set apart for the service or worship of a deity; is considered worthy of spiritual respect or devotion; or inspires awe or reverence among believers. The property is often ascribed to objects ( ...

to the world and manifesting the

kingdom (rule) of God. Possession of the

land of Israel

The Land of Israel () is the traditional Jewish name for an area of the Southern Levant. Related biblical, religious and historical English terms include the Land of Canaan, the Promised Land, the Holy Land, and Palestine. The definition ...

was contingent on fidelity to the Torah, and the

House of David

The Davidic line refers to the descendants of David, who established the House of David ( ) in the Kingdom of Israel and the Kingdom of Judah. In Judaism, the lineage is based on texts from the Hebrew Bible, as well as on later Jewish tradit ...

was considered the rightful rulers over the land (

2 Samuel 7:11–16).

The

Temple in Jerusalem

The Temple in Jerusalem, or alternatively the Holy Temple (; , ), refers to the two religious structures that served as the central places of worship for Israelites and Jews on the modern-day Temple Mount in the Old City of Jerusalem. Accord ...

was the dwelling place and throne of God (

1 Kings 8:12–13). It was there that a hereditary

priesthood offered

sacrifices

Sacrifice is an act or offering made to a deity. A sacrifice can serve as propitiation, or a sacrifice can be an offering of praise and thanksgiving.

Evidence of ritual animal sacrifice has been seen at least since ancient Hebrews and Greeks ...

of

incense

Incense is an aromatic biotic material that releases fragrant smoke when burnt. The term is used for either the material or the aroma. Incense is used for aesthetic reasons, religious worship, aromatherapy, meditation, and ceremonial reasons. It ...

,

food

Food is any substance consumed by an organism for Nutrient, nutritional support. Food is usually of plant, animal, or Fungus, fungal origin and contains essential nutrients such as carbohydrates, fats, protein (nutrient), proteins, vitamins, ...

, and various kinds of

animals

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the biological kingdom Animalia (). With few exceptions, animals consume organic material, breathe oxygen, have myocytes and are able to move, can reproduce sexually, and grow from a ...

to God. The

sin offering

A sin offering (, ''korban ḥatat'', , lit: "purification offering") is a sacrificial offering described and commanded in the Torah (Lev. 4.1-35); it could be fine flour or a proper animal.Leviticus 5:11 A sin offering also occurs in 2 Chronicl ...

(

Leviticus 4–5) and the annual

Day of Atonement

Yom Kippur ( ; , ) is the holiest day of the year in Judaism. It occurs annually on the 10th of Tishrei, corresponding to a date in late September or early October.

For traditional Jewish people, it is primarily centered on atonement and ...

ritual (

Leviticus 16

Acharei Mot (also Aharei Mot, Aharei Moth, or Acharei Mos, ) is the 29th weekly Torah portion in the annual cycle of Torah reading in Judaism. It is the sixth parashah or weekly portion () in the Book of Leviticus, containing Leviticus 16:1– ...

) served to both purify the temple and

atone for individual and national

sins

In religious context, sin is a transgression against divine law or a law of the deities. Each culture has its own interpretation of what it means to commit a sin. While sins are generally considered actions, any thought, word, or act considere ...

. "In both cases the sacrificial blood made possible the continuation or restoration of the relation between God and his people ruptured by sin and/or prevented by human impurity."

Conquest and Hellenization

The

First Temple

Solomon's Temple, also known as the First Temple (), was a biblical Temple in Jerusalem believed to have existed between the 10th and 6th centuries BCE. Its description is largely based on narratives in the Hebrew Bible, in which it was commis ...

was destroyed during the

siege of Jerusalem in 587BC, and the Jewish people were carried away into the

Babylonian exile

The Babylonian captivity or Babylonian exile was the period in Jewish history during which a large number of Judeans from the ancient Kingdom of Judah were forcibly relocated to Babylonia by the Neo-Babylonian Empire. The deportations occurre ...

(586–538BC). With the loss of the land and the temple, studying and following Torah became the central concern of Judaism. Some Jews, particularly the

Pharisees

The Pharisees (; ) were a Jews, Jewish social movement and school of thought in the Levant during the time of Second Temple Judaism. Following the Siege of Jerusalem (AD 70), destruction of the Second Temple in 70 AD, Pharisaic beliefs became ...

, came to believe that Torah devotion could replace temple worship, and this was facilitated by the establishment of

synagogue

A synagogue, also called a shul or a temple, is a place of worship for Jews and Samaritans. It is a place for prayer (the main sanctuary and sometimes smaller chapels) where Jews attend religious services or special ceremonies such as wed ...

s. For those unable to offer sacrifices at the temple, spiritual sacrifices (

almsgiving

Alms (, ) are money, food, or other material goods donated to people living in poverty. Providing alms is often considered an act of charity. The act of providing alms is called almsgiving.

Etymology

The word ''alms'' comes from the Old Engli ...

,

prayer

File:Prayers-collage.png, 300px, alt=Collage of various religionists praying – Clickable Image, Collage of various religionists praying ''(Clickable image – use cursor to identify.)''

rect 0 0 1000 1000 Shinto festivalgoer praying in front ...

,

fasting

Fasting is the act of refraining from eating, and sometimes drinking. However, from a purely physiological context, "fasting" may refer to the metabolic status of a person who has not eaten overnight (before "breakfast"), or to the metabolic sta ...

, or Torah study) could be substituted. After the return from exile, the

Second Temple

The Second Temple () was the Temple in Jerusalem that replaced Solomon's Temple, which was destroyed during the Siege of Jerusalem (587 BC), Babylonian siege of Jerusalem in 587 BCE. It was constructed around 516 BCE and later enhanced by Herod ...

became the center of Jewish national and religious life; nevertheless, the Torah continued to serve as "a portable Land, a movable Temple".

After the conquests of

Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip ...

(356–323BC), the Jewish homeland experienced

Hellenization

Hellenization or Hellenification is the adoption of Greek culture, religion, language, and identity by non-Greeks. In the ancient period, colonisation often led to the Hellenisation of indigenous people in the Hellenistic period, many of the ...

(the spread of

Greek culture

The culture of Greece has evolved over thousands of years, beginning in Minoan and later in Mycenaean Greece, continuing most notably into Classical Greece, while influencing the Roman Empire and its successor the Byzantine Empire. Other cultu ...

).

Hellenistic Judaism

Hellenistic Judaism was a form of Judaism in classical antiquity that combined Jewish religious tradition with elements of Hellenistic culture and religion. Until the early Muslim conquests of the eastern Mediterranean, the main centers of Hellen ...

was a movement that sought to combine Judaism with the best elements of Greek culture. The Greek-speaking

Jews of Alexandria

The history of the Jews in Alexandria dates back to the founding of the city by Alexander the Great in 332 BCE. Jews in Alexandria played a crucial role in the political, economic, cultural and religious life of Hellenistic and Roman Alexandria, ...

produced a Greek translation of the Bible called the

Septuagint

The Septuagint ( ), sometimes referred to as the Greek Old Testament or The Translation of the Seventy (), and abbreviated as LXX, is the earliest extant Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible from the original Biblical Hebrew. The full Greek ...

, which was used by the first Christians.

Antiochus IV Epiphanes

Antiochus IV Epiphanes ( 215 BC–November/December 164 BC) was king of the Seleucid Empire from 175 BC until his death in 164 BC. Notable events during Antiochus' reign include his near-conquest of Ptolemaic Egypt, his persecution of the Jews of ...

(), king of the

Seleucid Empire

The Seleucid Empire ( ) was a Greek state in West Asia during the Hellenistic period. It was founded in 312 BC by the Macedonian general Seleucus I Nicator, following the division of the Macedonian Empire founded by Alexander the Great ...

, adopted anti-Jewish policies in an attempt to Hellenize the Jews. He prohibited Jewish religious practices in 168 BC, introduced the worship of

Zeus

Zeus (, ) is the chief deity of the List of Greek deities, Greek pantheon. He is a sky father, sky and thunder god in ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology, who rules as king of the gods on Mount Olympus.

Zeus is the child ...

in the Temple in 167BC (the "

abomination of desolation

"Abomination of desolation" is a phrase from the Book of Daniel describing the pagan sacrifices with which the 2nd century BC Greek king Antiochus IV Epiphanes replaced the twice-daily offering in the Second Temple, Jewish temple, or alternativel ...

" of

Daniel 9 09 may refer to:

* The year 2009, or any year ending with 09, which may be written as '09

* September, the ninth month

* 9 (number)

* Ariège (department) (postal code), a French department

* Auckland, New Zealand, which has the telephone area code ...

:27 and

Daniel 11

Eleven or 11 may refer to:

*11 (number)

* One of the years 11 BC, AD 11, 1911, 2011

Literature

* ''Eleven'' (novel), a 2006 novel by British author David Llewellyn

*''Eleven'', a 1970 collection of short stories by Patricia Highsmith

*''Eleven'' ...

:31), and set up pagan altars everywhere. Jews who refused to follow the king's religious policies faced death.

Jewish martyrdom contributed to the belief in

resurrection of the dead

General resurrection or universal resurrection is the belief in a resurrection of the dead, or resurrection from the dead ( Koine: , ''anastasis onnekron''; literally: "standing up again of the dead") by which most or all people who have died ...

(

2 Maccabees 7:9).

The

Maccabean Revolt

The Maccabean Revolt () was a Jewish rebellion led by the Maccabees against the Seleucid Empire and against Hellenistic influence on Jewish life. The main phase of the revolt lasted from 167 to 160 BCE and ended with the Seleucids in control of ...

in 167BC restored an independent Jewish kingdom under the

Hasmonean dynasty

The Hasmonean dynasty (; ''Ḥašmōnāʾīm''; ) was a ruling dynasty of Judea and surrounding regions during the Hellenistic times of the Second Temple period (part of classical antiquity), from BC to 37 BC. Between and BC the dynasty rule ...

, which ruled as kings and

high priests. However, some Jews believed the Hasmoneans lacked legitimacy since they were not descended from the royal line of David nor the

priestly line of Zadok. The

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

conquered the Hasmonean kingdom in 63BC and appointed

client king

A client state in the context of international relations is a state that is economically, politically, and militarily subordinated to a more powerful controlling state. Alternative terms for a ''client state'' are satellite state, associated state ...

s. Under the Romans, the formerly lifelong office of high priest was filled by temporary appointments and "became increasingly the plaything for political and financial interests."

Apocalypticism

Jewish writings offered different explanations for Israel's domination by foreigners. According to the prophets

Isaiah

Isaiah ( or ; , ''Yəšaʿyāhū'', "Yahweh is salvation"; also known as Isaias or Esaias from ) was the 8th-century BC Israelite prophet after whom the Book of Isaiah is named.

The text of the Book of Isaiah refers to Isaiah as "the prophet" ...

,

Jeremiah

Jeremiah ( – ), also called Jeremias, was one of the major prophets of the Hebrew Bible. According to Jewish tradition, Jeremiah authored the Book of Jeremiah, book that bears his name, the Books of Kings, and the Book of Lamentations, with t ...

,

Amos

Amos or AMOS may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Amos'' (album), an album by Michael Ray

* Amos (band), an American Christian rock band

* ''Amos'' (film), a 1985 American made-for-television drama film

* Amos (guitar), a 1958 Gibson Fl ...

, and

Hosea

In the Hebrew Bible, Hosea ( or ; ), also known as Osee (), son of Beeri, was an 8th-century BC prophet in Israel and the nominal primary author of the Book of Hosea. He is the first of the Twelve Minor Prophets, whose collective writing ...

, Israel suffered as punishment for its sins. If the people repented, God would restore the kingdom.

An alternative worldview known as apocalypticism developed around the time of the Maccabean Revolt. The term is derived from the Greek word ( or ), and Jewish apocalypticists believed God had revealed the future to them. Major texts of

apocalyptic literature

Apocalyptic literature is a genre of prophetical writing that developed in post- Exilic Jewish culture and was popular among millennialist early Christians. '' Apocalypse'' () is a Greek word meaning "revelation", "an unveiling or unfolding o ...

were

Joel,

1 Enoch

The Book of Enoch (also 1 Enoch;

Hebrew: סֵפֶר חֲנוֹךְ, ''Sēfer Ḥănōḵ''; , ) is an ancient Jewish apocalyptic religious text, ascribed by tradition to the patriarch Enoch who was the father of Methuselah and the great-gran ...

,

Daniel

Daniel commonly refers to:

* Daniel (given name), a masculine given name and a surname

* List of people named Daniel

* List of people with surname Daniel

* Daniel (biblical figure)

* Book of Daniel, a biblical apocalypse, "an account of the acti ...

, the

Isaiah

Isaiah ( or ; , ''Yəšaʿyāhū'', "Yahweh is salvation"; also known as Isaias or Esaias from ) was the 8th-century BC Israelite prophet after whom the Book of Isaiah is named.

The text of the Book of Isaiah refers to Isaiah as "the prophet" ...

apocalypse (

chapters 24–27),

Jubilees

The Book of Jubilees is an ancient Jewish apocryphal text of 50 chapters (1,341 verses), considered Biblical canon, canonical by the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, as well as by Haymanot, Haymanot Judaism, a denomination observed by membe ...

,

Ascension of Moses,

Sibylline Oracles

The ''Sibylline Oracles'' (; sometimes called the pseudo-Sibylline Oracles) are a collection of oracular utterances written in Greek hexameters ascribed to the Sibyls, prophetesses who uttered divine revelations in a frenzied state. Fourteen b ...

,

4 Ezra

2 Esdras, also called 4 Esdras, Latin Esdras, or Latin Ezra, is an apocalyptic book in some English versions of the Bible. Tradition ascribes it to Ezra, a scribe and priest of the fifth century BC, whom the book identifies with the sixth-ce ...

,

2 Enoch

The Second Book of Enoch (abbreviated as 2 Enoch and also known as Slavonic Enoch, Slavic Enoch, or the Secrets of Enoch) is a pseudepigraphic text in the apocalyptic genre. It describes the ascent of the patriarch Enoch, ancestor of Noah, throug ...

,

2 Baruch

2 Baruch is a Jewish apocryphal text thought to have been written in the late 1st century CE or early 2nd century CE, after the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE. It is attributed to the biblical figure Baruch ben Neriah (c. 6th century BC) ...

,

Apocalypse of Abraham

The ''Apocalypse of Abraham'' is an apocalyptic Jewish pseudepigrapha (a text whose claimed authorship is uncertain) based on biblical Abraham narratives. It was probably composed in the first or second century, between 70–150 AD.

It has survi ...

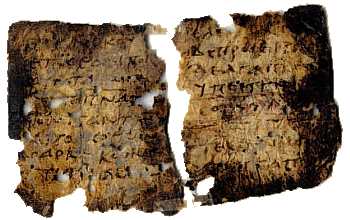

, some of the

Dead Sea Scrolls

The Dead Sea Scrolls, also called the Qumran Caves Scrolls, are a set of List of Hebrew Bible manuscripts, ancient Jewish manuscripts from the Second Temple period (516 BCE – 70 CE). They were discovered over a period of ten years, between ...

, and

3 Baruch

3 Baruch or the Greek Apocalypse of Baruch is a visionary, pseudepigraphic text written some time between the fall of Jerusalem in 70 AD and the third century. Scholars disagree on whether it was written by a Jew or a Christian, or whether a ...

.

Apocalypticism is a

dualistic worldview. In the present age, the world is corrupted by the cosmic forces of evil (

Satan

Satan, also known as the Devil, is a devilish entity in Abrahamic religions who seduces humans into sin (or falsehood). In Judaism, Satan is seen as an agent subservient to God, typically regarded as a metaphor for the '' yetzer hara'', or ' ...

and his

demons

A demon is a malevolent supernatural entity. Historically, belief in demons, or stories about demons, occurs in folklore, mythology, religion, occultism, and literature; these beliefs are reflected in media including

fiction, comics, film, t ...

). But in the future, God and his

angels

An angel is a spiritual (without a physical body), heavenly, or supernatural being, usually humanoid with bird-like wings, often depicted as a messenger or intermediary between God (the transcendent) and humanity (the profane) in variou ...

will destroy the forces of evil. God will

redeem the whole world, not just the Jewish people. In the age to come, "there would be no suffering or pain; there would be no more hatred, despair, war, disease, or death. God would be the ruler of all, in a kingdom that would never end." At this time, there will be a

last judgment

The Last Judgment is a concept found across the Abrahamic religions and the '' Frashokereti'' of Zoroastrianism.

Christianity considers the Second Coming of Jesus Christ to entail the final judgment by God of all people who have ever lived, res ...

and a

universal resurrection

General resurrection or universal resurrection is the belief in a resurrection of the dead, or resurrection from the dead ( Koine: , ''anastasis onnekron''; literally: "standing up again of the dead") by which most or all people who have died ...

so that all people can be rewarded or punished.

Apocalypticists expected God to accomplish these things by sending a savior figure or

messiah

In Abrahamic religions, a messiah or messias (; ,

; ,

; ) is a saviour or liberator of a group of people. The concepts of '' mashiach'', messianism, and of a Messianic Age originated in Judaism, and in the Hebrew Bible, in which a ''mashiach ...

. ''Messiah'' (

Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

) means "anointed" and was used in the Old Testament to designate

Jewish kings

The article deals with the biblical and historical kings of the Land of Israel—Abimelech of Sichem, the three kings of the United Kingdom of Israel and those of its successor states, Israel and Judah, followed in the Second Temple period, ...

and in some cases priests and

prophets

In religion, a prophet or prophetess is an individual who is regarded as being in contact with a divine being and is said to speak on behalf of that being, serving as an intermediary with humanity by delivering messages or teachings from the ...

whose status was symbolized by being anointed with

holy anointing oil

In the ancient Israelite religion, the holy anointing oil () formed an integral part of the ordination of the priesthood and the High Priest as well as in the consecration of the articles of the Tabernacle ( Exodus 30:26) and subsequent temple ...

. The term is most associated with King David, to whom God promised an eternal kingdom (

2 Samuel 7:11–17). After the fall of David's dynasty, this promise was reaffirmed by the prophets Isaiah, Jeremiah, and

Ezekiel

Ezekiel, also spelled Ezechiel (; ; ), was an Israelite priest. The Book of Ezekiel, relating his visions and acts, is named after him.

The Abrahamic religions acknowledge Ezekiel as a prophet. According to the narrative, Ezekiel prophesied ...

, who foresaw a future Davidic king who would establish and reign over an idealized kingdom.

In the Second Temple period, there was no consensus on who the messiah would be or what he would do. Some believed the messiah would be a political figure, a son of David, who would restore an independent

Kingdom of Israel. A detailed description of such a Davidic messiah is found in the 17th psalm of the

Psalms of Solomon

The Psalms of Solomon is a group of eighteen psalms, religious songs or poems, written in the first or second century BC. They are classed as Biblical apocrypha or as Old Testament pseudepigrapha; they appear in various copies of the Septuagint an ...

. Others believed in a priestly messiah.

Psalm 110

Psalm 110 is the 110th psalm of the Book of Psalms, beginning in English in the King James Version: "The said unto my Lord". In the slightly different numbering system used in the Greek Septuagint and Latin Vulgate translations of the Bible, th ...

refers to a figure belonging to the

priesthood of Melchizedek

The priesthood of Melchizedek is a role in Abrahamic religions, modelled on Melchizedek, combining the dual position of king and priest.

Hebrew Bible

Melchizedek is a king and priest appearing in the Book of Genesis. The name means "King of Righ ...

, the priest-king of

Genesis 14:17–24. The

Testament of Levi

The Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs is a constituent of the apocryphal scriptures connected with the Bible. It is believed to be a pseudepigraphical work of the dying commands of the twelve sons of Jacob. It is part of the Oskan Armenian Or ...

refers to God raising up a "new priest". Others anticipated the coming of a celestial figure called the

Son of Man who would lead armies of angels and inaugurate the reign of God on earth (

Daniel 7

Daniel 7 (the seventh chapter of the Book of Daniel) tells of Daniel's vision of four world-kingdoms replaced by the kingdom of the saints or "holy ones" of the Most High, which will endure for ever. Four beasts come out of the sea, the Ancien ...

:13–14).

Jewish sects

After the Maccabean Revolt, several Jewish sects emerged that differed on their interpretations of the Torah, their reaction to foreign domination, and their acceptance of a non-Zadokite high priest. The New Testament explicitly mentions three Jewish sects, and the Jewish historian

Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; , ; ), born Yosef ben Mattityahu (), was a Roman–Jewish historian and military leader. Best known for writing '' The Jewish War'', he was born in Jerusalem—then part of the Roman province of Judea—to a father of pr ...

mentions four.

The

Pharisees

The Pharisees (; ) were a Jews, Jewish social movement and school of thought in the Levant during the time of Second Temple Judaism. Following the Siege of Jerusalem (AD 70), destruction of the Second Temple in 70 AD, Pharisaic beliefs became ...

rejected Greek religion and culture. They were committed to obeying the Torah and developed rules to clarify its ambiguities. For example, the

Ten Commandments

The Ten Commandments (), or the Decalogue (from Latin , from Ancient Greek , ), are religious and ethical directives, structured as a covenant document, that, according to the Hebrew Bible, were given by YHWH to Moses. The text of the Ten ...

required Jews to keep the Sabbath holy, but the Torah does not explain how this is to be done. The rules developed by the Pharisees became known as the

oral Torah

According to Rabbinic Judaism, the Oral Torah or Oral Law () are statutes and legal interpretations that were not recorded in the Five Books of Moses, the Written Torah (), and which are regarded by Orthodox Judaism, Orthodox Jews as prescriptive ...

. Like priests serving in the Temple, Pharisees attempted to maintain a state of Temple holiness throughout their daily lives by adhering to

Jewish purity laws. This required them to separate from ordinary people and could explain the origin of the term ''Pharisee'', which means "separated ones". As a

lay

Lay or LAY may refer to:

Places

*Lay Range, a subrange of mountains in British Columbia, Canada

* Lay, Loire, a French commune

*Lay (river), France

* Lay, Iran, a village

* Lay, Kansas, United States, an unincorporated community

* Lay Dam, Alaba ...

movement, the Pharisees had no official religious role within Judaism, but they were respected by ordinary Jews. Pharisaic ideas, such as belief in angels, demons, and resurrection became widely accepted.

The

Sadducees

The Sadducees (; ) were a sect of Jews active in Judea during the Second Temple period, from the second century BCE to the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE. The Sadducees are described in contemporary literary sources in contrast to ...

were drawn from the families of the chief priests and the Jewish aristocracy. Their religion centered on the Temple and its sacrifices, and they cooperated with the Romans so that those sacrifices could continue. They were less concerned with purity regulations in daily life. The Sadducees only accepted the written Torah as authoritative, and they denied the existence of angels or a future resurrection.

The

Essenes

The Essenes (; Hebrew: , ''ʾĪssīyīm''; Greek: Ἐσσηνοί, Ἐσσαῖοι, or Ὀσσαῖοι, ''Essenoi, Essaioi, Ossaioi'') or Essenians were a mystic Jewish sect during the Second Temple period that flourished from the 2nd cent ...

formed in protest of the Hasmonean usurpation of the high priesthood and refused to worship at the Jerusalem Temple. Separating from other Jews, they were an ascetic movement focused on strict adherence to the Torah and purity regulations. Like the Pharisees, Essenes believed in the existence of angels and in a future resurrection. The Essenes were an apocalyptic sect that believed God would give Israel two messiahs—a Davidic king and an anointed priest—to lead the Sons of Light in a war against the Sons of Darkness . The Sons of Light will be victorious, and a new Temple will be built to replace the corrupt one.

Josephus writes about an unnamed "fourth philosophy" that could include several different groups, particularly the

Zealots

The Zealots were members of a Jewish political movements, Jewish political movement during the Second Temple period who sought to incite the people of Judaea (Roman province), Judaea to rebel against the Roman Empire and expel it from the Land ...

and the

Sicarii

The Sicarii were a group of Jewish assassins who were active throughout Judaea in the years leading up to and during the First Jewish–Roman War, which took place at the end of the Second Temple period. Often associated with the Zealots (altho ...

. These groups endorsed armed resistance against foreign rulers and their Jewish collaborators.

Greek philosophy

Church historian

Diarmaid MacCulloch

Diarmaid Ninian John MacCulloch (; born 31 October 1951) is an English academic and historian, specialising in ecclesiastical history and the history of Christianity. Since 1995, he has been a fellow of St Cross College, Oxford; he was former ...

has observed that "Christianity in its first five centuries was in many respects a dialogue between Judaism and Graeco-Roman philosophy". There are similarities between early Christianity and ancient philosophy. Biblical scholar

Udo Schnelle writes, "philosophy is a salutary means for living well and dying well... The followers of Jesus of Nazareth practiced a comparable lifestyle, treated comparable subjects, and produced comparable literature."

The related philosophies of

Cynicism and

Stoicism

Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy that flourished in ancient Greece and Rome. The Stoics believed that the universe operated according to reason, ''i.e.'' by a God which is immersed in nature itself. Of all the schools of ancient ...

emphasized

ethics

Ethics is the philosophy, philosophical study of Morality, moral phenomena. Also called moral philosophy, it investigates Normativity, normative questions about what people ought to do or which behavior is morally right. Its main branches inclu ...

and individual freedom. Cynics "commended and practiced a lifestyle oriented to nature and to reason, which eradicates false passions from the soul (lust, craving, anger) and leads to a simple life without needs." Some Cynics adopted a wandering,

ascetic

Asceticism is a lifestyle characterized by abstinence from worldly pleasures through self-discipline, self-imposed poverty, and simple living, often for the purpose of pursuing spiritual goals. Ascetics may withdraw from the world for their pra ...

way of life that may have influenced

Christian asceticism

Asceticism is a lifestyle characterized by abstinence from worldly pleasures through self-discipline, self-imposed poverty, and simple living, often for the purpose of pursuing spiritual goals. Ascetics may withdraw from the world for their pra ...

.

Stoicism taught

monistic pantheism, according to which a benevolent, impersonal reason (Greek: ) permeates the universe and is the source of human reason. "Because all humans are part of a grand design that is rational, Stoics thought that reason had put everyone... in a place for a purpose", and Stoics strove to live in accordance with reason. One need only obey what Stoics called the

natural law

Natural law (, ) is a Philosophy, philosophical and legal theory that posits the existence of a set of inherent laws derived from nature and universal moral principles, which are discoverable through reason. In ethics, natural law theory asserts ...

to be virtuous. To attain virtue (practical wisdom, moderation, self-control, and justice), a person must become free of the

passions

''Passions'' is an American television soap opera that originally aired on NBC from July 5, 1999, to September 7, 2007, and on DirecTV's The 101 Network from September 17, 2007, to August 7, 2008. Created by screenwriter James E. Reilly and ...

(fear, grief, lust, hate, etc.). Stoicism's ethical teachings and its doctrines of the and natural law had important influences on early

Christian ethics

Christian ethics, also known as moral theology, is a multi-faceted ethical system. It is a Virtue ethics, virtue ethic, which focuses on building moral character, and a Deontological ethics, deontological ethic which emphasizes duty according ...

and thought. The

Apostle Paul

Paul, also named Saul of Tarsus, commonly known as Paul the Apostle and Saint Paul, was a Apostles in the New Testament, Christian apostle ( AD) who spread the Ministry of Jesus, teachings of Jesus in the Christianity in the 1st century, first ...

uses Stoic terminology in

1 Corinthians

The First Epistle to the Corinthians () is one of the Pauline epistles, part of the New Testament of the Christian Bible. The epistle is attributed to Paul the Apostle and a co-author, Sosthenes, and is addressed to the Christian church in Anc ...

when describing the Christian community as a body in which each part is necessary . As described in the

Acts of the Apostles

The Acts of the Apostles (, ''Práxeis Apostólōn''; ) is the fifth book of the New Testament; it tells of the founding of the Christian Church and the spread of The gospel, its message to the Roman Empire.

Acts and the Gospel of Luke make u ...

, Paul used Stoic ideas in his

Areopagus sermon

The Areopagus sermon refers to a sermon delivered by Apostle Paul in Athens, at the Areopagus, and recounted in Acts 17:16–34... The Areopagus sermon is the most dramatic and most fully-reported speech of the missionary career of Saint Paul ...

at

Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

.

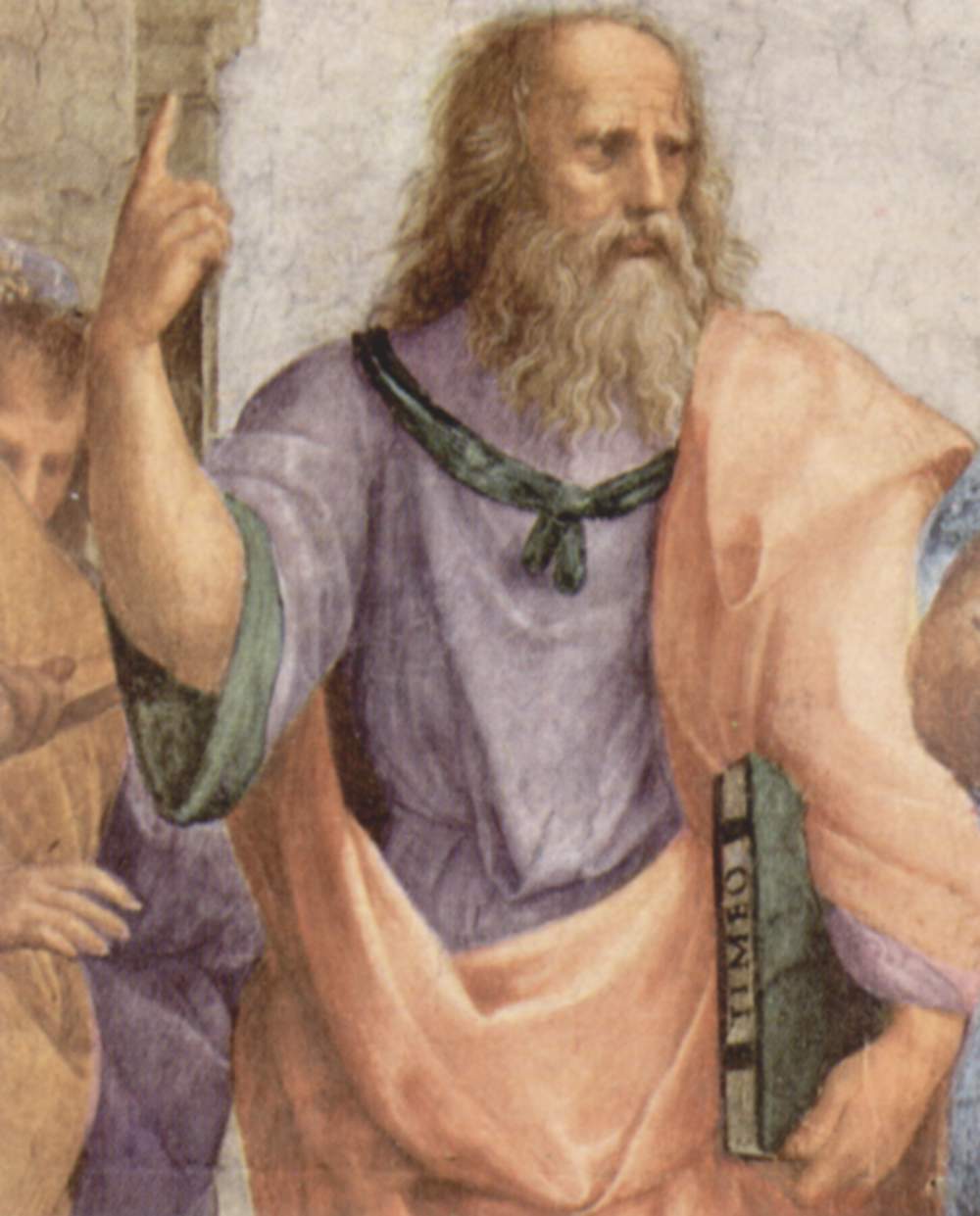

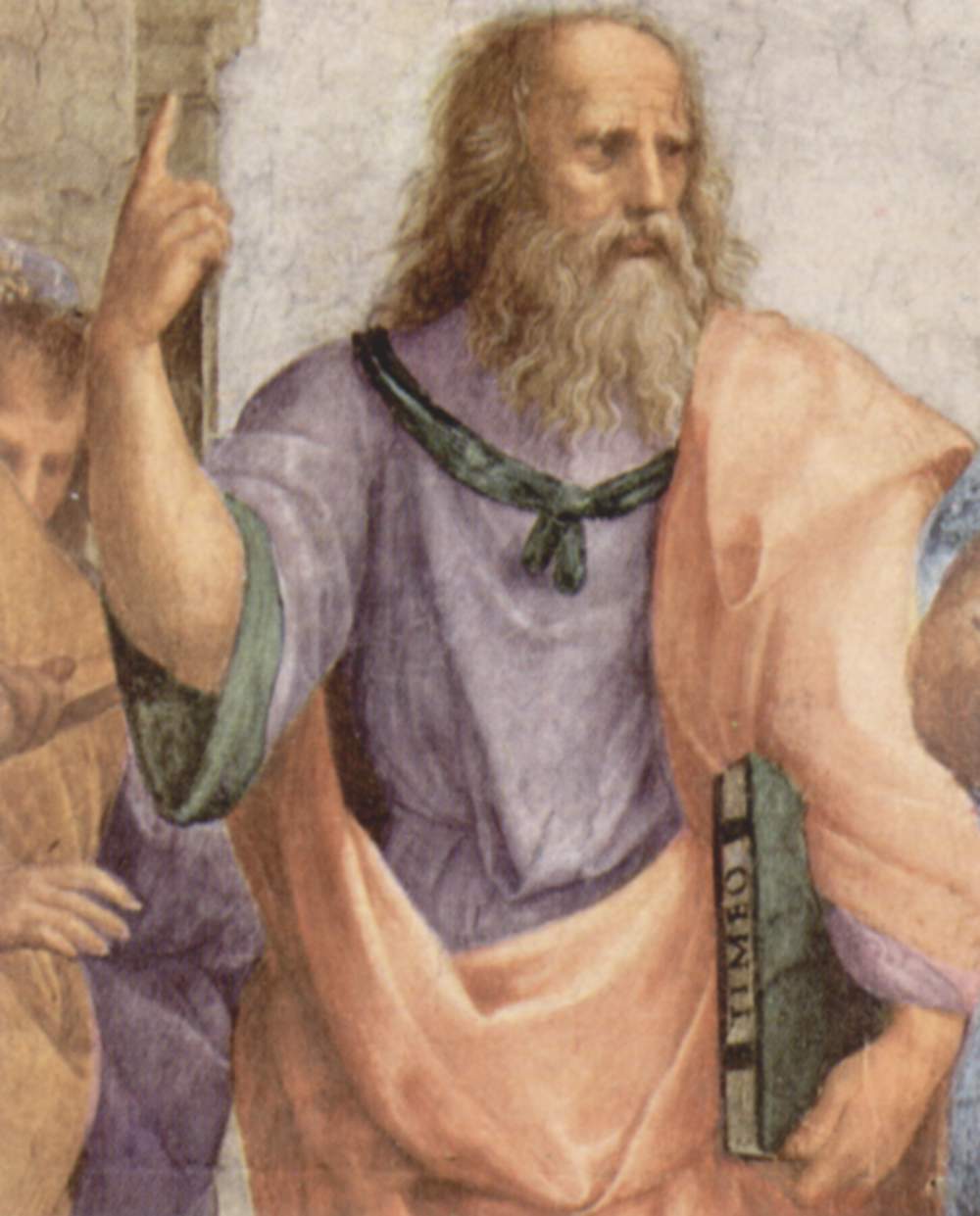

The most important philosophical influence was

Middle Platonism

Middle Platonism is the modern name given to a stage in the development of Platonic philosophy, lasting from about 90 BC – when Antiochus of Ascalon rejected the scepticism of the new Academy – until the development of neoplatonis ...

(68 BC250 AD) and

Neo-Platonism

Neoplatonism is a version of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a series of thinkers. Among the common i ...

(250–500):

* According to the

theory of forms

The Theory of Forms or Theory of Ideas, also known as Platonic idealism or Platonic realism, is a philosophical theory credited to the Classical Greek philosopher Plato.

A major concept in metaphysics, the theory suggests that the physical w ...

, there are two worlds, the

world of ideas and the physical world of perception. The latter experiences change, illusion, and decay. God belongs the world of ideas, which is

intelligible and transcendent. This influenced Christian ideas of the "world" and also

heaven

Heaven, or the Heavens, is a common Religious cosmology, religious cosmological or supernatural place where beings such as deity, deities, angels, souls, saints, or Veneration of the dead, venerated ancestors are said to originate, be throne, ...

and earth.

* Plato's

Idea of the Good

The Form of the Good, or more literally translated "the Idea of the Good" (), is a concept in the philosophy of Plato. In Plato's Theory of Forms, in which Forms are defined as perfect, eternal, and changeless concepts existing outside space and ...

had a significant influence on Christian conceptions of God. In Platonic thought, the supreme deity was perfect and unchangeable. But this supreme god lacked "compassion for human tragedy, because compassion is a passion or emotion" which involves changes in mood. This was a very different deity from the biblical God. While the God of the Bible was

transcendent, he was also passionate and compassionate towards humans. Indeed, the biblical God was constantly intervening in the affairs of Israel. Despite these differences, "there arose the custom, deeply entrenched in some theological circles, of speaking of God in the same terms Plato used to refer to the Idea of the Good: God is

impassive

Apathy, also referred to as indifference, is a lack of feeling, emotion, interest, or concern about something. It is a state of indifference, or the suppression of emotions such as concern, excitement, motivation, or passion. An apathetic in ...

, infinite, incomprehensible, indescribable, and so on."

*

Plato's theory of the soul was used by Christians to defend their own beliefs about immortality and life after death.

*Under the influence of

Platonic epistemology

In philosophy, Plato's epistemology is a theory of knowledge developed by the Greek philosopher Plato and his followers.

Platonic epistemology holds that knowledge of Platonic Ideas is innate, so that learning is the development of ideas buri ...

(theory of knowledge), Christians adopted a distrust of sensory perception as a means of attaining knowledge. Nevertheless, Christians rejected the Platonic idea that learning is actually "recall" or "reminiscence" as this required belief in the pre-existence of souls, which Christians rejected.

Jesus

Sources

Christianity centers on the

life

Life, also known as biota, refers to matter that has biological processes, such as Cell signaling, signaling and self-sustaining processes. It is defined descriptively by the capacity for homeostasis, Structure#Biological, organisation, met ...

and

teachings

A school of thought, or intellectual tradition, is the perspective of a group of people who share common characteristics of opinion or outlook of a philosophy, discipline, belief, social movement, economics, cultural movement, or art movement.

...

of

Jesus of Nazareth

Jesus ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, and many other names and titles, was a 1st-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the central figure of Christianity, the world's largest religi ...

, who lived . In the early years of Christianity,

oral gospel traditions

Oral gospel traditions is the hypothetical first stage in the formation of the written gospels as information was passed by word of mouth. These oral traditions included different types of stories about Jesus. For example, people told anecdotes a ...

would have been important in transmitting memories and stories of Jesus. Biblical scholar

Peter Stuhlmacher writes, "The men and women surrounding Jesus learned his sayings by heart in accordance with the early Jewish pattern, preserved them in their memory, and passed them on to others." Biblical scholar

Bart D. Ehrman

Bart Denton Ehrman (born October 5, 1955) is an American New Testament scholar focusing on textual criticism of the New Testament, the historical Jesus, and the origins and development of early Christianity. He has written and edited 30 books ...

writes, "Stories about Jesus were thus being told throughout the Mediterranean for decades to convert people and to educate those who had converted, to win people to faith and to instruct those who had been brought in; stories were told in evangelism, in education, in exhortation, and probably in services of worship." According to biblical scholar Anthony Le Donne, early Christian communities preserved memories of Jesus by relating them to familiar stories or

types

Type may refer to:

Science and technology Computing

* Typing, producing text via a keyboard, typewriter, etc.

* Data type, collection of values used for computations.

* File type

* TYPE (DOS command), a command to display contents of a file.

* Ty ...

, such as the

son of David.

The oldest surviving written sources about Jesus are 1st-century texts that were later included in the

New Testament

The New Testament (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus, as well as events relating to Christianity in the 1st century, first-century Christianit ...

. The earliest are the seven authentic

Pauline epistles

The Pauline epistles, also known as Epistles of Paul or Letters of Paul, are the thirteen books of the New Testament attributed to Paul the Apostle, although the authorship of some is in dispute. Among these epistles are some of the earliest ext ...

, letters written to various Christian congregations by

Paul the Apostle

Paul, also named Saul of Tarsus, commonly known as Paul the Apostle and Saint Paul, was a Apostles in the New Testament, Christian apostle ( AD) who spread the Ministry of Jesus, teachings of Jesus in the Christianity in the 1st century, first ...

in the 50s AD. The four

canonical gospels

Gospel originally meant the Christian message (" the gospel"), but in the second century AD the term (, from which the English word originated as a calque) came to be used also for the books in which the message was reported. In this sen ...

are

ancient biographies of Jesus' life. The oldest is the

Gospel of Mark

The Gospel of Mark is the second of the four canonical Gospels and one of the three synoptic Gospels, synoptic Gospels. It tells of the ministry of Jesus from baptism of Jesus, his baptism by John the Baptist to his death, the Burial of Jesus, ...

, written . The gospels of

Matthew

Matthew may refer to:

* Matthew (given name)

* Matthew (surname)

* ''Matthew'' (album), a 2000 album by rapper Kool Keith

* Matthew (elm cultivar), a cultivar of the Chinese Elm ''Ulmus parvifolia''

Christianity

* Matthew the Apostle, one of ...

and

Luke

Luke may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Luke (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters with the name

* Luke (surname), including a list of people with the name

* Luke the Evangelist, author of the Gospel of Luk ...

were written . The

Gospel of John

The Gospel of John () is the fourth of the New Testament's four canonical Gospels. It contains a highly schematic account of the ministry of Jesus, with seven "Book of Signs, signs" culminating in the raising of Lazarus (foreshadowing the ...

was written last, around100.

The oral and written transmission that led to the gospels involved eyewitnesses, who would have contributed to the development of the gospel tradition and been consulted as what would become the Gospels took shape. The gospels were likely composed within the lifetimes of various eyewitnesses, including Jesus's own family. However, biblical scholar

Helen Bond

Helen Katharine Bond (born 1968) is a British Professor of Christian Origins and New Testament. She has written many books related to Pontius Pilate, Jesus and Judaism.

Biography

Bond was born in 1968 and raised in the North East of England. S ...

writes that the canonical gospels "clearly reflect the post-Easter reflections of the early church. They were not written by eye-witnesses".

Biblical scholar

Dale Allison

Dale C. Allison Jr. (born November 25, 1955) is an American historian and Christian theologian. His areas of expertise include the historical Jesus, the Gospel of Matthew, Second Temple Jewish literature, and the history of the interpretation ...

notes, "our

Synoptic ospelwriters thought that they were reconfiguring memories of Jesus, not inventing theological tales." However, this does not guarantee the gospels' historical accuracy. As Bond points out, the gospels are not " historical accounts of the life of Jesus" but "are declarations of the true identity of Jesus as Christ and Son of God, written with the intention of encouraging or strengthening the faith of their earliest readers."

Teachings

The four canonical gospels focus on three themes:

# What Jesus taught, particularly the

parables of Jesus

The parables of Jesus are found in the Synoptic Gospels and some of the non-canonical gospels. They form approximately one third of his recorded teachings. Christians place great emphasis on these parables, which they generally regard as the word ...

.

# What Jesus did, particularly the

miracles of Jesus

The miracles of Jesus are the many miraculous deeds attributed to Jesus in Christian texts, with the majority of these miracles being faith healings, exorcisms, resurrections, and control over nature.

In the Gospel of John, Jesus is said to ...

.

# What witnesses said about Jesus.

As

the Christ or "Anointed One" (Greek: ), Jesus is identified as the fulfillment of

messianic prophecies

In Abrahamic religions, a messiah or messias (; ,

; ,

; ) is a saviour or liberator of a group of people. The concepts of ''mashiach'', messianism, and of a Messianic Age originated in Judaism, and in the Hebrew Bible, in which a ''mashiach'' ...

in the Old Testament. Through the accounts of his miraculous

virgin birth, the gospels present Jesus as the

Son of God

Historically, many rulers have assumed titles such as the son of God, the son of a god or the son of heaven.

The term "Son of God" is used in the Hebrew Bible as another way to refer to humans who have a special relationship with God. In Exo ...

. Throughout the New Testament, Jesus is called ("

lord

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power (social and political), power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The appellation can also denote certain persons who hold a title of the Peerage o ...

" in Greek), a word used in the Septuagint translation of the Hebrew Bible for the name of God.

While the

synoptic gospels

The gospels of Gospel of Matthew, Matthew, Gospel of Mark, Mark, and Gospel of Luke, Luke are referred to as the synoptic Gospels because they include many of the same stories, often in a similar sequence and in similar or sometimes identical ...

agree with each other on the broad outlines of Jesus' life, each gospel has its own emphasis. The Gospel of Mark presents Jesus as "the suffering Messiah, the

Son of man who is crucified and later vindicated by God". In Matthew, Jesus is Messiah, Son of David, and a new

Moses

In Abrahamic religions, Moses was the Hebrews, Hebrew prophet who led the Israelites out of slavery in the The Exodus, Exodus from ancient Egypt, Egypt. He is considered the most important Prophets in Judaism, prophet in Judaism and Samaritani ...

. In Luke, he is a prophet and martyr. In John, Jesus is described as God himself. In an appropriation of Greek philosophical concepts, John's Gospel identifies Jesus as the

divine logos by which the world was created: "And the Word became flesh and lived among us, and we have seen his glory" (

John 1:14).

Jesus' message centered on the coming of the

Kingdom of God

The concept of the kingship of God appears in all Abrahamic religions, where in some cases the terms kingdom of God and kingdom of Heaven are also used. The notion of God's kingship goes back to the Hebrew Bible, which refers to "his kingdom" ...

(in

Jewish eschatology

Jewish eschatology is the area of Jewish philosophy, Jewish theology concerned with events that will happen in the Eschatology, end of days and related concepts. This includes the ingathering of the exiled Jewish diaspora, diaspora, the coming ...

a future when God actively rules over the world in justice, mercy, and peace). Jesus urged his followers to

repent

Repentance is reviewing one's actions and feeling contrition or regret for past or present wrongdoings, which is accompanied by commitment to and actual actions that show and prove a change for the better.

In modern times, it is generally seen ...

in preparation for the kingdom's coming. In

Mark 1:15, Jesus proclaims, "The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God is at hand; repent and believe in

the gospel

The gospel or good news is a theological concept in several religions. In the historical Roman imperial cult and today in Christianity, the gospel is a message about salvation by a divine figure, a savior, who has brought peace or other benefi ...

." His ethical teachings included loving one's enemies, not serving both God and

Mammon

Mammon (Aramaic: מָמוֹנָא, māmōnā) in the New Testament is commonly thought to mean money, material wealth, or any entity that promises wealth, and is associated with the greedy pursuit of gain. The Gospel of Matthew and the Gospel of ...

, and not judging others. These ethical teachings are encapsulated in the

Sermon on the Mount

The Sermon on the Mount ( anglicized from the Matthean Vulgate Latin section title: ) is a collection of sayings spoken by Jesus of Nazareth found in the Gospel of Matthew (chapters 5, 6, and 7). that emphasizes his moral teachings. It is th ...

and the

Lord's Prayer

The Lord's Prayer, also known by its incipit Our Father (, ), is a central Christian prayer attributed to Jesus. It contains petitions to God focused on God’s holiness, will, and kingdom, as well as human needs, with variations across manusc ...

.

To Jewish audiences, early preaching focused on Jesus as the fulfillment of Israel's messianic hopes (see for example the

Apostle Peter

An apostle (), in its literal sense, is an emissary. The word is derived from Ancient Greek ἀπόστολος (''apóstolos''), literally "one who is sent off", itself derived from the verb ἀποστέλλειν (''apostéllein''), "to se ...

's sermon in

Acts 2

Acts 2 is the second chapter of the Acts of the Apostles in the New Testament of the Christian Bible. The book containing this chapter is anonymous but early Christian tradition asserted that Luke composed this book as well as the Gospel of Luke ...

). When preaching to Greek audiences, however, Christians appealed to the Greek intellectual tradition. This approach can be seen in the

Areopagus sermon

The Areopagus sermon refers to a sermon delivered by Apostle Paul in Athens, at the Areopagus, and recounted in Acts 17:16–34... The Areopagus sermon is the most dramatic and most fully-reported speech of the missionary career of Saint Paul ...

delivered by the Apostle Paul as described in

Acts 17

Acts 17 is the seventeenth chapter of the Acts of the Apostles in the New Testament of the Christian Bible. It continues the second missionary journey of Paul, together with Silas and Timothy: in this chapter, the Christian gospel is preached in ...

. Citing Ancient Athens, Athenian worship of the Unknown God, Paul proclaims that this god is revealed to humanity through Jesus. Quoting the Athenian poet Aratus, Paul states that in God "we live and move and have our being" (Acts 17:28).

Crucifixion and resurrection

After his cleansing of the Temple, Jesus was arrested, Pilate's court, tried, and Crucifixion of Jesus, crucified. According to John, Jesus dies on the day of preparation for Passover, when the Passover sacrifice was slaughtered in the temple. John understands Jesus to be the Lamb of God and Suffering Servant who takes away the sins of the world (s:Bible (American Standard)/John#Chapter 1, John 1:29, also s:Bible (American Standard)/1 Corinthians#Chapter 5, 1 Corinthians 5:7).

The followers of Jesus believed he appeared to them after his death. The oldest written account of Easter is provided by Paul in 1 Corinthians 15#Resurrection of Jesus, 1 Corinthians 15:3–5. Given his conversion occurred , the tradition he cites must be older than 40 CE. The passage states:

The resurrection of Jesus became the foundation of Christianity. Paul writes, "If Christ has not been raised, then our proclamation is vain, and your faith is also vain" (1 Corinthians 15:14). The gospel accounts conclude with a description of the Ascension of Jesus. The New Testament epistles explain that Jesus makes Salvation in Christianity, salvation possible, and the resurrection confirms the truth of his identity. Through Faith in Christianity, faith, believers experience Union with Christ, union with Jesus and both share in Passion of Jesus, his suffering and the Hope (virtue), hope of his resurrection.

First century

Gentile Christians and Jewish law

The first Christians were Jewish Christian, Jewish Christians, and the center of Christianity was the History of early Christianity#Jerusalem, church in Jerusalem. Acts records that during the 40s and 50sAD there was Circumcision controversy in early Christianity, controversy over circumcision and the place of Gentiles (non-Jews) in the movement. The Judaizers believed that Gentile Christians needed to follow Jewish laws and customs, particularly Circumcision controversy in early Christianity, circumcision, to be saved. Paul, however, argued that no one could be made righteous or Justification (theology), justified by following the law of Moses but only through faith in Jesus, citing the prophet Habakkuk: "he who through faith is righteous shall live" (Habakkuk 2:4, Habbakuk 2:4). At the Council of Jerusalem held in 49AD, it was decided that Gentile believers would not have to undergo circumcision.

The issue remained alive for many years after the Jerusalem council. New Testament sources suggest that James the Just, brother of Jesus and leader of the Jerusalem church still believed the Torah was binding on Jewish Christians. In Galatians 2#Incident at Antioch (2:11–14), Galatians 2:11-14, Paul described "people from James" causing the Saint Peter, Apostle Peter and other Jewish Christians in Antioch to break table fellowship with Gentiles . Joel Marcus, professor of Christian origins, suggests that Peter's own position was somewhere between James and Paul, but that he probably leaned more toward James.

The Epistle of James stresses the importance of the Torah as "the perfect law of liberty" and "the implanted word that is able to save your souls". Marcus comments that in the epistle "little room is left for the saving function of Jesus, who is mentioned only twice, and in an incidental way (1.1, 2:1)."

The influence of the Jerusalem church and its form of Jewish Christianity declined after the First Jewish–Roman War, Jewish revolt of 66–70AD and never recovered. Pauline theology became the mainstream form of Christianity, and "all Christians alive today are the heirs of the Church which Paul created."

Holy Spirit

References to the Holy Spirit in Christianity, Holy Spirit are found in the New Testament, but it is not fully clear how the Spirit relates to Jesus. The term would have been familiar to Jewish Christians . In the Gospel of John, the Spirit descends on Jesus during Baptism of Jesus, his baptism by John the Baptist. Paul speaks of the Spirit often in his letters. The Spirit unites all Christians: "For by one Spirit we were all baptized into one body—Jews or Greeks, slaves or free—and all were made to drink of one Spirit" (1 Corinthians 12:13).

Paul wrote that the Spirit empowers the church with various gifts or . In 1 Corinthians 14, Paul wrote about the practice of ecstatically speaking in tongues (or unknown languages). Acts 2#Verses 1–7, Acts 2:1-13 described how the Spirit descended on the Apostles in the New Testament, Twelve Apostles on the feast of Pentecost and made them speak in foreign languages.

Patristic era

The period between the last New Testament writings () and the Council of Chalcedon (451) is called the patristic era, named for the Church Fathers (, ). The Anglican, Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Lutheran, and Reformed Christianity, Reformed churches consider themselves to be continuations of the patristic tradition.

A large quantity of theological reflection emerged in the early centuries of the Christian church—in a wide variety of genres, in a variety of contexts, and in several languages—much of it the product of attempts to discuss how Christian faith should be lived in cultures very different from the one in which it was born. For instance, a good deal of Greek language literature can be read as an attempt to come to terms with Hellenistic culture. The period sees the slow emergence of orthodoxy (the idea of which seems to emerge from the conflicts between Catholic Christianity and gnosticism, Gnostic Christianity), the establishment of a Biblical canon, debates about the doctrine of the Trinity (most notably between the councils of First Council of Nicaea, Nicaea in 325 and First Council of Constantinople, Constantinople in 381), about Christology (most notably between the councils of Constantinople in 381 and Council of Chalcedon, Chalcedon in 451), about the purity of the Church (for instance in the debates surrounding the Donatists), and about Divine grace, grace, free will and predestination (for instance in the debate between Augustine of Hippo and Pelagius (British monk), Pelagius).

Influential texts and writers in the 2nd century include:

* The collection known as the Apostolic Fathers (mostly 2nd century)

* Justin Martyr (c. 100/114 – c. 162/168)

* Clement of Alexandria (died c. 215)

* Irenaeus of Lyons (c. 130–202)

* Various 'Gnostic' authors, such as Marcion (c. 85-c. 160), Valentinius (c. 100 – c. 153) and Basilides (c. 117–138)

* Some of the texts commonly referred to as the New Testament apocrypha.

Influential texts and writers between c. 200 and 325 (the First Council of Nicaea) include:

* Tertullian (c. 155–230)

* Hippolytus (writer), Hippolytus (died 235)

* Origen (c. 182 – c. 251)

* Cyprian (died c. 258)

* Arius (256–336)

* Other Gnostic texts and texts from the New Testament apocrypha.

Second century

Apostolic Fathers

The earliest Patristics, Patristic writings is a collection known as the Apostolic Fathers. The name was applied to this collection in the 16th century because it was believed that the authors had been trained by the apostles. There is some chronological overlap between the latest writings of the New Testament and the earliest of the Apostolic Fathers. For example, the ''Didache'' was probably written well within the New Testament period.

The collection spans various genres, but the writings share two themes in common: paraenesis (moral teaching) and discussion of Christianity's relationship to Judaism. The collection also reveals the development of distinct theological schools or orientations: Asia Minor and Syria, Rome, and Alexandria. The school of Asia Minor (the Johannine literature, Ignatius of Antioch, Ignatius, Polycarp, and Papias of Hierapolis, Papias) stressed union with Christ for attaining Eternal life (Christianity), eternal life. Roman Christianity (Clement of Rome, Clement and ''The Shepherd of Hermas'') was influenced by Stoicism and stressed ethics and morality. The School of Alexandria, Alexandrian school (''Epistle of Barnabas'') was influenced by

Middle Platonism

Middle Platonism is the modern name given to a stage in the development of Platonic philosophy, lasting from about 90 BC – when Antiochus of Ascalon rejected the scepticism of the new Academy – until the development of neoplatonis ...

and Neoplatonism. It combined a focus on ethics with an allegorical interpretation of the Old Testament in the tradition of Philo.

1 Clement is a letter written around AD 96 by Clement I, the bishop of Rome, to the church in Ancient Corinth, Corinth. While Clement mainly addresses those Corinthians who had become rebellious and divisive, the letter also provides clues to his theology. Several trinitarian formulas are present, such as, "Have we not one God and one Christ and one Spirit of grace, the Spirit that has been poured out on us?" Clement's Christology is characterized by a belief in the pre-existence of Christ. Clement provides the earliest articulation of apostolic succession: the apostles chose holy men to succeed them and these in turn chose their own successors who cannot be deposed by the congregation. He calls these church leaders bishops and deacons; however, he sometimes uses the title ''presbyter'' interchangeably with ''bishop'', indicating that these two offices had not yet become separated.

The ''Didache'' or ''Doctrine of the Twelve Apostles'' is a Ancient church orders, church order or manual probably composed in the late 1st century or early 2nd century in Palestine or Syria. This document provides insight into early Christian liturgy, which is clearly influenced by ancient Jewish practice. It regards immersion baptism as normal but allows for affusion (pouring water over the head), which is the earliest description of an alternative method of baptism. The eucharist is described, but it is not yet separate from the agape feast. In the ''Didache'', prophets are the preeminent leaders of the church with bishops and deacons in subordinate roles. It is possible this arrangement represents "a period of transition between the primitive system of charismatic authority and the hierarchical organization that was slowly developing within the church".

Ignatius of Antioch, Ignatius, the bishop of Antioch, wrote seven surviving letters while traveling as a prisoner to face Christian martyr, martyrdom in Rome. Ignatius wrote to defend belief in the Incarnation (Christianity), incarnation of God in Jesus Christ from Judaizers, who believed Jesus was only a human teacher, and Docetists, who denied the humanity of Jesus. In his Epistle of Ignatius to the Ephesians, Epistle to the Ephesians, Ignatius affirmed both the divinity and humanity of Christ: "There is one Physician: both flesh and spirit, Monogenēs, begotten and unbegotten, in man, God, in death, true life, both from Mary, mother of Jesus, Mary and from God, first passible and then impassible, Jesus Christ our Lord". Ignatius was the first writer to describe the church as ''Catholic (term), catholic'', by which he meant it was whole or complete in contrast to the heretical sects. It is within the church that a person is Union with Christ, united with Christ through the sacraments, especially the eucharist. However, there is no church apart from the bishops, presbyters, and deacons who are the successors to the apostles. Ignatius provided the earliest description of a monarchical bishop, instructing his readers that nothing be done in the church without the bishop's consent, including baptism, the eucharist, and marriage. Ignatius identified the eucharist closely with the death and resurrection of Christ—"it is the flesh of our Saviour Jesus Christ, which flesh suffered for our sins and which the Father raised up". For Ignatius, the eucharist unites the believer to the passion of Christ. He wrote that it was "the medicine of immortality, the antidote which results not in dying but in living forever in Jesus Christ".

The author of the ''Epistle of Barnabas'' used an allegorical interpretation of the Old Testament to harmonize it with Christian teachings. The stories of the Old Testament were understood to be

types

Type may refer to:

Science and technology Computing

* Typing, producing text via a keyboard, typewriter, etc.

* Data type, collection of values used for computations.

* File type

* TYPE (DOS command), a command to display contents of a file.

* Ty ...

that point to the saving work of Jesus. The Apostolic Fathers, all of whom were Gentiles, struggled with the authority of the Old Covenant and the relationship between Judaism and Christianity. The wikisource:Epistle of Barnabas (Lake translation)#CHAPTER_14, ''Epistle of Barnabas'' 14.3-4 claimed the Tablets of Stone, tablets of the covenant were destroyed at Mount Sinai (Bible), Sinai and that Israel had no

covenant

Covenant may refer to:

Religion

* Covenant (religion), a formal alliance or agreement made by God with a religious community or with humanity in general

** Covenant (biblical), in the Hebrew Bible

** Covenant in Mormonism, a sacred agreement b ...

with God.

''The Shepherd of Hermas'' taught that a person could be forgiven once for postbaptismal sin (sins committed after baptism). Hermas also introduced the idea of Works of Supererogation, works of supererogation (to do more than the commandments of God require). This concept would contribute to the later development of the treasury of merit and the Western Christianity, Western Church's penitential system. In ''The Shephard of Hermas'', the Holy Spirit is conflated with the Son of God: "the holy pre-existent Spirit which created the whole creation God made to dwell in flesh that he desired. This flesh therefore in which the Holy Spirit dwelt was subject to the Spirit... He chose this flesh as a partner with the Holy Spirit".

The Apostolic Fathers placed great importance on baptism. According to theologian Geoffrey Hugo Lampe, the Fathers considered baptism to be "the seal with which believers are marked out as God's people, the way of death to sin and demons and of rebirth to resurrection-life, the new white robe which must be preserved undefiled, the shield of Christ's soldier, the sacrament of the reception of the Holy Spirit." The Apostolic Fathers also clearly considered the eucharist to be the center of Christian worship.

Apocryphal literature

During the same time period as the Apostolic Fathers, Christians were also producing works claiming to be ancient Jewish texts. These are considered Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, Old Testament pseudepigrapha, and the most important are:

* ''Ascension of Isaiah''

* ''Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs''

* ''Second Book of Enoch''

The early 2nd century also saw the production of works claiming apostolic origin and are now categorized as New Testament apocrypha, New Testament apocryphal literature:

* ''Gospel of Peter''

* ''Revelation of Peter''

* ''Gospel of the Hebrews''

* ''Epistle of the Apostles''

Greek apologists

In the middle of the 2nd century, Christian apologists wrote to defend the faith against criticism and Persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire, persecution by Roman authorities. In general, the apologists responded to two types of accusations, popular rumors about Christian practices (such as that they ate children or that the lovefeast was actually an orgy) and sophisticated attacks on Christian beliefs (such as that Christians borrowed and corrupted ideas from Greek philosophy). The Greek apologists are:.

* Aristides of Athens

* Justin Martyr

* Tatian

* Athenagoras of Athens

* Theophilus of Antioch

* Hermias (apologist), Hermias

* Epistle to Diognetus

* Melito of Sardis

Justin Martyr is the most important of the 2nd-century apologists. Justin's explanation of Christian beliefs was influenced by Middle Platonism. For him, God the Father was transcendent, and he Monogenēs, begot the logos (Word) who reveals the Father to creation. Christ is the logos and source of all truth. The Greek philosophers of the past only knew the Word partially. But the full truth was revealed to Christians in the person of Jesus Christ. In Justin's ''Dialogue with Trypho'', the Jewish Trypho accused Christians of holding the Mosaic covenant in "rash contempt". Justin distinguishes between different parts of the Old Covenant, saying that Christians kept what was "naturally good, pious, and righteous". Justin also uses typological interpretation to connect events in the Old Testament to Christ. For example, the Passover sacrifice was a type of Christ whose Blood of Christ, blood saves those who believe in him.

Biblical canon

When New Testament authors used the word ''scripture'', they referred to writings in the Old Testament. In a relatively short time, Christian writers began referring to New Testament writings as scripture. Several criteria were used to determine which books belonged in the scriptural Biblical canon, canon:

* used in Christian worship

* reflected tradition thought to be apostolic in origin

* was Catholic (term), catholic (or "universal") in the sense of being in widespread use

By the late 2nd century, there was general agreement on the canonicity of the four gospels, Acts, and the Pauline letters. Origen () used the same 27 books as in the modern New Testament but noted there were disputes over the canonicity of Epistle to the Hebrews, Hebrews, Epistle of James, James, 2 Peter, 2 John, 3 John, and Book of Revelation, Revelation .

In 367, Athanasius, the bishop of Alexandria, included in his Easter letter a list of canonical books identical to the modern New Testament. This list was accepted by the Greek church and the Council of Rome under Pope Damasus I in 382. Athanasius' list was also approved by the Synod of Hippo in 393 and the Council of Carthage (397), Synod of Carthage in 397 in North Africa. By the 5th century, there was common agreement on the New Testament canon in most of the churches.

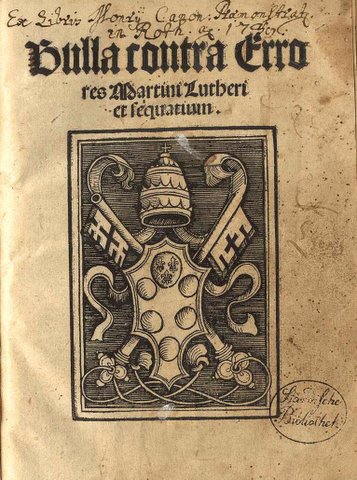

Nicene Creed