Marine prokaryotes on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Marine prokaryotes are marine

Past species have also left records of their evolutionary history. Fossils, along with the comparative anatomy of present-day organisms, constitute the morphological, or anatomical, record. By comparing the anatomies of both modern and extinct species, paleontologists can infer the lineages of those species. However, this approach is most successful for organisms that had hard body parts, such as shells, bones or teeth. Further, as prokaryotes such as bacteria and archaea share a limited set of common morphologies, their fossils do not provide information on their ancestry.

Prokaryotes inhabited the Earth from approximately 3–4 billion years ago. No obvious changes in morphology or cellular organisation occurred in these organisms over the next few billion years. The eukaryotic cells emerged between 1.6 and 2.7 billion years ago. The next major change in cell structure came when bacteria were engulfed by eukaryotic cells, in a cooperative association called

Past species have also left records of their evolutionary history. Fossils, along with the comparative anatomy of present-day organisms, constitute the morphological, or anatomical, record. By comparing the anatomies of both modern and extinct species, paleontologists can infer the lineages of those species. However, this approach is most successful for organisms that had hard body parts, such as shells, bones or teeth. Further, as prokaryotes such as bacteria and archaea share a limited set of common morphologies, their fossils do not provide information on their ancestry.

Prokaryotes inhabited the Earth from approximately 3–4 billion years ago. No obvious changes in morphology or cellular organisation occurred in these organisms over the next few billion years. The eukaryotic cells emerged between 1.6 and 2.7 billion years ago. The next major change in cell structure came when bacteria were engulfed by eukaryotic cells, in a cooperative association called  The history of life was that of the

The history of life was that of the

The words prokaryote and eukaryote come from the Greek where ''pro'' means "before", ''eu'' means "well" or "true", and ''karyon'' means "nut", "kernel" or "nucleus". So etymologically, prokaryote means "before nucleus" and eukaryote means "true nucleus".

The division of life forms between prokaryotes and eukaryotes was firmly established by the microbiologists Roger Stanier and C. B. van Niel in their 1962 paper, ''The concept of a bacterium''. One reason for this classification was so what was then often called ''blue-green algae'' (now called

The words prokaryote and eukaryote come from the Greek where ''pro'' means "before", ''eu'' means "well" or "true", and ''karyon'' means "nut", "kernel" or "nucleus". So etymologically, prokaryote means "before nucleus" and eukaryote means "true nucleus".

The division of life forms between prokaryotes and eukaryotes was firmly established by the microbiologists Roger Stanier and C. B. van Niel in their 1962 paper, ''The concept of a bacterium''. One reason for this classification was so what was then often called ''blue-green algae'' (now called  The earliest evidence for life on earth comes from

The earliest evidence for life on earth comes from  A stream of airborne microorganisms, including prokaryotes, circles the planet above weather systems but below commercial air lanes. Some peripatetic microorganisms are swept up from terrestrial dust storms, but most originate from marine microorganisms in sea spray. In 2018, scientists reported that hundreds of millions of viruses and tens of millions of bacteria are deposited daily on every square meter around the planet.

Microscopic life undersea is diverse and still poorly understood, such as for the role of

A stream of airborne microorganisms, including prokaryotes, circles the planet above weather systems but below commercial air lanes. Some peripatetic microorganisms are swept up from terrestrial dust storms, but most originate from marine microorganisms in sea spray. In 2018, scientists reported that hundreds of millions of viruses and tens of millions of bacteria are deposited daily on every square meter around the planet.

Microscopic life undersea is diverse and still poorly understood, such as for the role of

File:Trichodesmium_bloom_off_Great_Barrier_Reef_2014-03-07_19-59.jpg, Bloom of the filamentous cyanobacteria '' Trichodesmium''

File:Potomac river eutro.jpg,

File:Synechococcus PCC 7002 DIC.jpg, '' Synechococcus'', a widespread marine cyanobacterium

File:Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942 electron micrograph showing carboxysomes.jpeg, Carboxysomes appearing as polyhedral dark structures within a species of ''Synechococcus''

The tiny (0.6'' '' μm) marine cyanobacterium ''

The

The

File:RT8-4.jpg, Eocytes may be the most abundant of marine archaea

File:Halobacteria with scale.jpg,

'' Nanoarchaeum equitans'' is a species of marine archaea discovered in 2002 in a

'' Nanoarchaeum equitans'' is a species of marine archaea discovered in 2002 in a

Viruses parasiting MGII are classified as magroviruses * Marine Group III (MG-III): also marine Euryarchaeota, Marine Benthic Group D * Marine Group IV (MG-IV): also marine Euryarchaeota

* Phototrophy is a particularly significant marker that should always play a primary role in bacterial classification.

* Aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria (AAPBs) are widely distributed marine

* Phototrophy is a particularly significant marker that should always play a primary role in bacterial classification.

* Aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria (AAPBs) are widely distributed marine

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Depending on their latitude and whether the bacteria are north or south of the equator, the Earth's magnetic field has one of the two possible polarities, and a direction that points with varying angles into the ocean depths, and away from the generally more oxygen rich surface. Aerotaxis is the response by which bacteria migrate to an optimal oxygen concentration in an oxygen gradient. Various experiments have clearly shown that

Phototrophic metabolism relies on one of three energy-converting pigments:

Phototrophic metabolism relies on one of three energy-converting pigments:

File:Alvinella pompejana01.jpg, The "hairy" backs of Pompeii worms are colonies of symbiotic bacteria.

File:Hesiocaeca methanicola noaa.jpg, '' Hesiocaeca methanicola'' lives at great depths on methane ice and appear to survive in symbiosis with bacteria which metabolize the

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Most of the volume of the world ocean is in darkness. The processes occurring within the thin illuminated surface layer (the photic layer from the surface down to between 50 and 170 metres) are of major significance to the global biosphere. For example, the visible region of the solar spectrum (the so-called photosynthetically available radiation or PAR) reaching this sunlit layer fuels about half of the

Most of the volume of the world ocean is in darkness. The processes occurring within the thin illuminated surface layer (the photic layer from the surface down to between 50 and 170 metres) are of major significance to the global biosphere. For example, the visible region of the solar spectrum (the so-called photosynthetically available radiation or PAR) reaching this sunlit layer fuels about half of the  The diagram on the right shows links among the ocean's

The diagram on the right shows links among the ocean's

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

bacteria

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one Cell (biology), biological cell. They constitute a large domain (biology), domain of Prokaryote, prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micr ...

and marine archaea

Archaea ( ) is a Domain (biology), domain of organisms. Traditionally, Archaea only included its Prokaryote, prokaryotic members, but this has since been found to be paraphyletic, as eukaryotes are known to have evolved from archaea. Even thou ...

. They are defined by their habitat as prokaryote

A prokaryote (; less commonly spelled procaryote) is a unicellular organism, single-celled organism whose cell (biology), cell lacks a cell nucleus, nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Ancient Gree ...

s that live in marine environments, that is, in the saltwater of seas or oceans or the brackish

Brackish water, sometimes termed brack water, is water occurring in a natural environment that has more salinity than freshwater, but not as much as seawater. It may result from mixing seawater (salt water) and fresh water together, as in estuari ...

water of coastal estuaries

An estuary is a partially enclosed coastal body of brackish water with one or more rivers or streams flowing into it, and with a free connection to the open sea. Estuaries form a transition zone between river environments and maritime environm ...

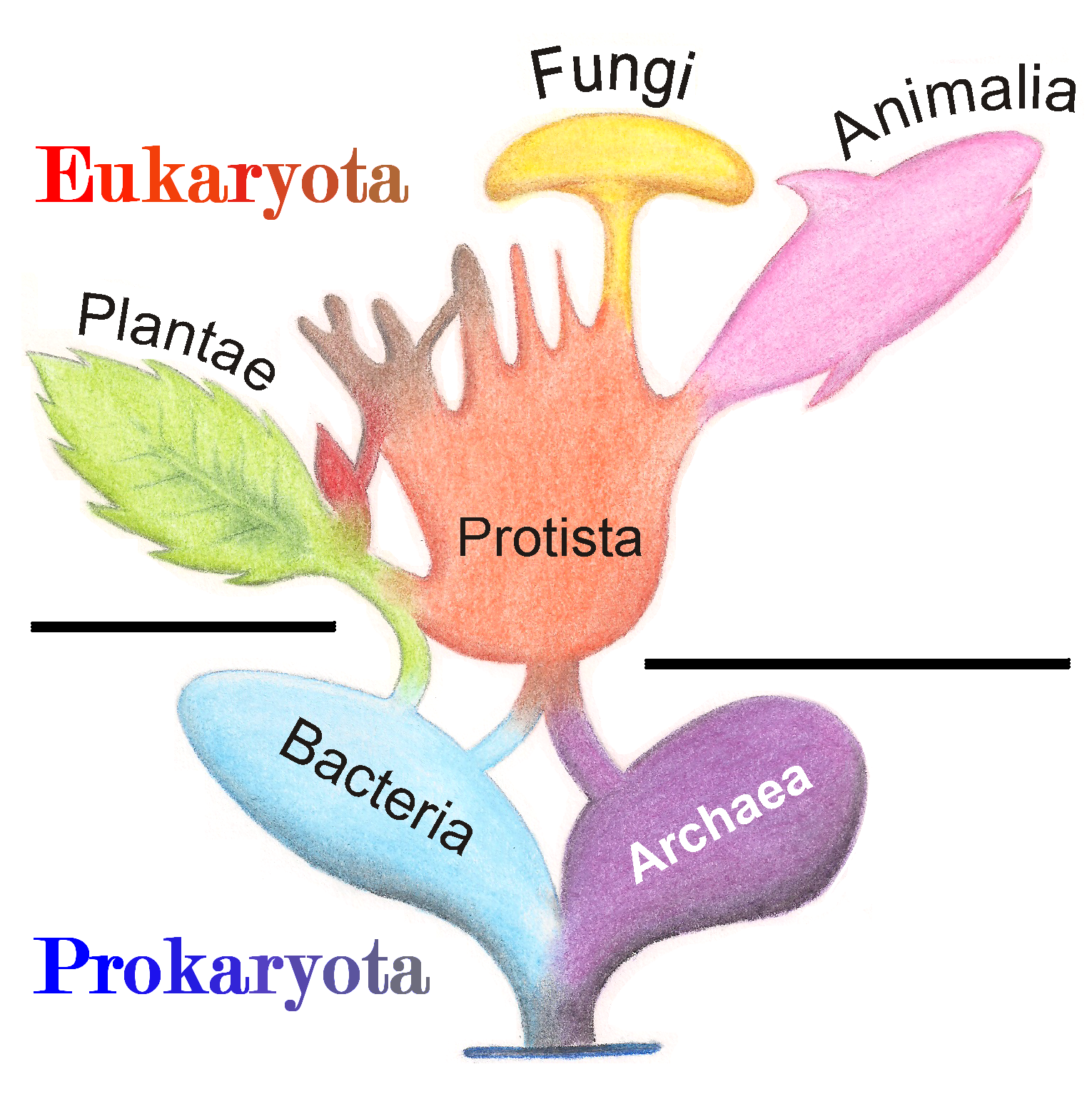

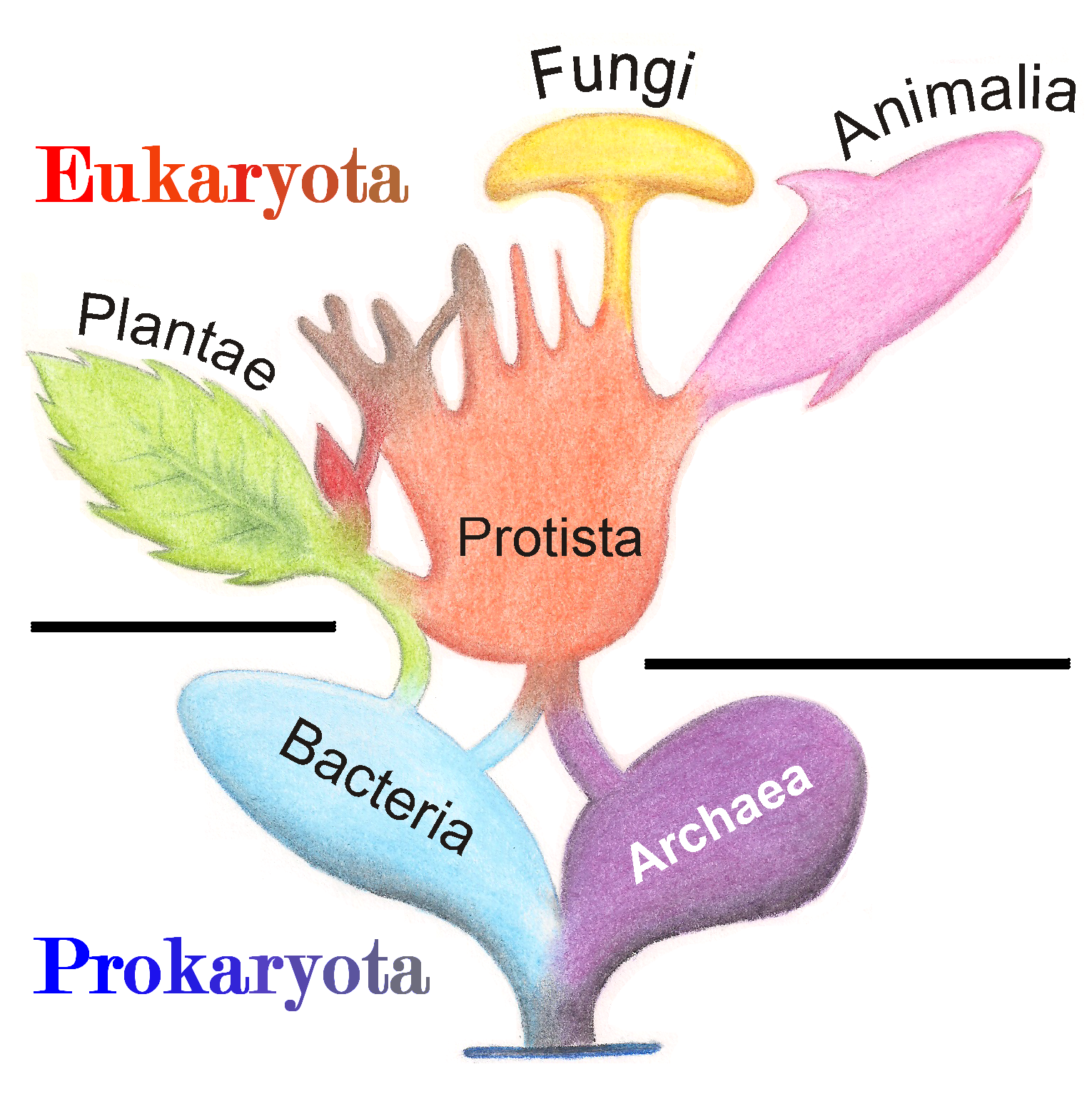

. All cellular life forms can be divided into prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Eukaryote

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the Domain (biology), domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose Cell (biology), cells have a membrane-bound cell nucleus, nucleus. All animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms ...

s are organism

An organism is any life, living thing that functions as an individual. Such a definition raises more problems than it solves, not least because the concept of an individual is also difficult. Many criteria, few of them widely accepted, have be ...

s whose cells have a nucleus enclosed within membranes, whereas prokaryotes are the organisms that do not have a nucleus enclosed within a membrane. The three-domain system

The three-domain system is a taxonomic classification system that groups all cellular life into three domains, namely Archaea, Bacteria and Eukarya, introduced by Carl Woese, Otto Kandler and Mark Wheelis in 1990. The key difference from ea ...

of classifying life adds another division: the prokaryotes are divided into two domains of life, the microscopic bacteria and the microscopic archaea, while everything else, the eukaryotes, become the third domain.

Prokaryotes play important roles in ecosystem

An ecosystem (or ecological system) is a system formed by Organism, organisms in interaction with their Biophysical environment, environment. The Biotic material, biotic and abiotic components are linked together through nutrient cycles and en ...

s as decomposer

Decomposers are organisms that break down dead organisms and release the nutrients from the dead matter into the environment around them. Decomposition relies on chemical processes similar to digestion in animals; in fact, many sources use the word ...

s recycling nutrients. Some prokaryotes are pathogen

In biology, a pathogen (, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of"), in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a Germ theory of d ...

ic, causing disease and even death in plants and animals. Marine prokaryotes are responsible for significant levels of the photosynthesis

Photosynthesis ( ) is a system of biological processes by which photosynthetic organisms, such as most plants, algae, and cyanobacteria, convert light energy, typically from sunlight, into the chemical energy necessary to fuel their metabo ...

that occurs in the ocean, as well as significant cycling of carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalence, tetravalent—meaning that its atoms are able to form up to four covalent bonds due to its valence shell exhibiting 4 ...

and other nutrients

A nutrient is a substance used by an organism to survive, grow and reproduce. The requirement for dietary nutrient intake applies to animals, plants, fungi and protists. Nutrients can be incorporated into cells for metabolic purposes or excret ...

.

Prokaryotes live throughout the biosphere

The biosphere (), also called the ecosphere (), is the worldwide sum of all ecosystems. It can also be termed the zone of life on the Earth. The biosphere (which is technically a spherical shell) is virtually a closed system with regard to mat ...

. In 2018 it was estimated the total biomass

Biomass is a term used in several contexts: in the context of ecology it means living organisms, and in the context of bioenergy it means matter from recently living (but now dead) organisms. In the latter context, there are variations in how ...

of all prokaryotes on the planet was equivalent to 77 billion tonne

The tonne ( or ; symbol: t) is a unit of mass equal to 1,000 kilograms. It is a non-SI unit accepted for use with SI. It is also referred to as a metric ton in the United States to distinguish it from the non-metric units of the s ...

s of carbon (77 Gt C). This is made up of 7 Gt C for archaea and 70 Gt C for bacteria. These figures can be contrasted with the estimate for the total biomass for animals on the planet, which is about 2 Gt C, and the total biomass of humans, which is 0.06 Gt C. This means archaea collectively have over 100 times the collective biomass of humans, and bacteria over 1000 times.

There is no clear evidence of life on Earth during the first 600 million years of its existence. When life did arrive, it was dominated for 3,200 million years by the marine prokaryotes. More complex life, in the form of crown eukaryotes, did not appear until the Cambrian explosion a mere 500 million years ago.

Evolution

TheEarth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to Planetary habitability, harbor life. This is enabled by Earth being an ocean world, the only one in the Solar System sustaining liquid surface water. Almost all ...

is about 4.54 billion years old. The earliest undisputed evidence of life on Earth dates from at least 3.5 billion years ago, during the Eoarchean

The Eoarchean ( ; also spelled Eoarchaean) is the first Era (geology), era of the Archean, Archean Eon of the geologic record. It spans 431 million years, from the end of the Hadean Eon 4031 annum, Mya to the start of the Paleoarchean Era 3600 M ...

Era after a geological crust started to solidify following the earlier molten Hadean

The Hadean ( ) is the first and oldest of the four geologic eons of Earth's history, starting with the planet's formation about 4.6 billion years ago (estimated 4567.30 ± 0.16 million years ago set by the age of the oldest solid material ...

Eon. Microbial mat

A microbial mat is a multi-layered sheet or biofilm of microbial colonies, composed of mainly bacteria and/or archaea. Microbial mats grow at interfaces between different types of material, mostly on submerged or moist surfaces, but a few surviv ...

fossils

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

have been found in 3.48 billion-year-old sandstone

Sandstone is a Clastic rock#Sedimentary clastic rocks, clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of grain size, sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate mineral, silicate grains, Cementation (geology), cemented together by another mineral. Sand ...

in Western Australia

Western Australia (WA) is the westernmost state of Australia. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to the south, the Northern Territory to the north-east, and South Australia to the south-east. Western Aust ...

.

Past species have also left records of their evolutionary history. Fossils, along with the comparative anatomy of present-day organisms, constitute the morphological, or anatomical, record. By comparing the anatomies of both modern and extinct species, paleontologists can infer the lineages of those species. However, this approach is most successful for organisms that had hard body parts, such as shells, bones or teeth. Further, as prokaryotes such as bacteria and archaea share a limited set of common morphologies, their fossils do not provide information on their ancestry.

Prokaryotes inhabited the Earth from approximately 3–4 billion years ago. No obvious changes in morphology or cellular organisation occurred in these organisms over the next few billion years. The eukaryotic cells emerged between 1.6 and 2.7 billion years ago. The next major change in cell structure came when bacteria were engulfed by eukaryotic cells, in a cooperative association called

Past species have also left records of their evolutionary history. Fossils, along with the comparative anatomy of present-day organisms, constitute the morphological, or anatomical, record. By comparing the anatomies of both modern and extinct species, paleontologists can infer the lineages of those species. However, this approach is most successful for organisms that had hard body parts, such as shells, bones or teeth. Further, as prokaryotes such as bacteria and archaea share a limited set of common morphologies, their fossils do not provide information on their ancestry.

Prokaryotes inhabited the Earth from approximately 3–4 billion years ago. No obvious changes in morphology or cellular organisation occurred in these organisms over the next few billion years. The eukaryotic cells emerged between 1.6 and 2.7 billion years ago. The next major change in cell structure came when bacteria were engulfed by eukaryotic cells, in a cooperative association called endosymbiosis

An endosymbiont or endobiont is an organism that lives within the body or cells of another organism. Typically the two organisms are in a mutualism (biology), mutualistic relationship. Examples are nitrogen-fixing bacteria (called rhizobia), whi ...

. The engulfed bacteria and the host cell then underwent coevolution, with the bacteria evolving into either mitochondria or hydrogenosomes. Another engulfment of cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria ( ) are a group of autotrophic gram-negative bacteria that can obtain biological energy via oxygenic photosynthesis. The name "cyanobacteria" () refers to their bluish green (cyan) color, which forms the basis of cyanobacteri ...

l-like organisms led to the formation of chloroplasts in algae and plants.

The history of life was that of the

The history of life was that of the unicellular

A unicellular organism, also known as a single-celled organism, is an organism that consists of a single cell, unlike a multicellular organism that consists of multiple cells. Organisms fall into two general categories: prokaryotic organisms and ...

prokaryotes and eukaryotes until about 610 million years ago when multicellular organisms began to appear in the oceans in the Ediacaran

The Ediacaran ( ) is a geological period of the Neoproterozoic geologic era, Era that spans 96 million years from the end of the Cryogenian Period at 635 Million years ago, Mya to the beginning of the Cambrian Period at 538.8 Mya. It is the last ...

period. The evolution of multicellularity occurred in multiple independent events, in organisms as diverse as sponge

Sponges or sea sponges are primarily marine invertebrates of the animal phylum Porifera (; meaning 'pore bearer'), a basal clade and a sister taxon of the diploblasts. They are sessile filter feeders that are bound to the seabed, and a ...

s, brown algae

Brown algae (: alga) are a large group of multicellular algae comprising the class (biology), class Phaeophyceae. They include many seaweeds located in colder waters of the Northern Hemisphere. Brown algae are the major seaweeds of the temperate ...

, cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria ( ) are a group of autotrophic gram-negative bacteria that can obtain biological energy via oxygenic photosynthesis. The name "cyanobacteria" () refers to their bluish green (cyan) color, which forms the basis of cyanobacteri ...

, slime mould

Slime mold or slime mould is an informal name given to a polyphyletic assemblage of unrelated eukaryotic organisms in the Stramenopiles, Rhizaria, Discoba, Amoebozoa and Holomycota clades. Most are near-microscopic; those in the Myxogastria ...

s and myxobacteria

The myxobacteria ("slime bacteria") are a group of bacteria that predominantly live in the soil and feed on insoluble organic substances. The myxobacteria have very large genomes relative to other bacteria, e.g. 9–10 million nucleotides except ...

. In 2016 scientists reported that, about 800 million years ago, a minor genetic change in a single molecule called GK-PID may have allowed organisms to go from a single cell organism to one of many cells.

Soon after the emergence of these first multicellular organisms, a remarkable amount of biological diversity appeared over a span of about 10 million years, in an event called the Cambrian explosion. Here, the majority of types

Type may refer to:

Science and technology Computing

* Typing, producing text via a keyboard, typewriter, etc.

* Data type, collection of values used for computations.

* File type

* TYPE (DOS command), a command to display contents of a file.

* Ty ...

of modern animals appeared in the fossil record, as well as unique lineages that subsequently became extinct. Various triggers for the Cambrian explosion have been proposed, including the accumulation of oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

in the atmosphere

An atmosphere () is a layer of gases that envelop an astronomical object, held in place by the gravity of the object. A planet retains an atmosphere when the gravity is great and the temperature of the atmosphere is low. A stellar atmosph ...

from photosynthesis.

Background

cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria ( ) are a group of autotrophic gram-negative bacteria that can obtain biological energy via oxygenic photosynthesis. The name "cyanobacteria" () refers to their bluish green (cyan) color, which forms the basis of cyanobacteri ...

) would cease to be classified as plants but grouped with bacteria.

In 1990 Carl Woese

Carl Richard Woese ( ; July 15, 1928 – December 30, 2012) was an American microbiologist and biophysicist. Woese is famous for defining the Archaea (a new domain of life) in 1977 through a pioneering phylogenetic taxonomy of 16S ribosomal ...

''et al.'' introduced the three-domain system

The three-domain system is a taxonomic classification system that groups all cellular life into three domains, namely Archaea, Bacteria and Eukarya, introduced by Carl Woese, Otto Kandler and Mark Wheelis in 1990. The key difference from ea ...

. The prokaryotes were split into two domains, the archaea and the bacteria, while the eukaryotes become a domain in their own right. The key difference from earlier classifications is the splitting of archaea from bacteria.

The earliest evidence for life on earth comes from

The earliest evidence for life on earth comes from biogenic

A biogenic substance is a product made by or of life forms. While the term originally was specific to metabolite compounds that had toxic effects on other organisms, it has developed to encompass any constituents, secretions, and metabolites of p ...

carbon signatures and stromatolite

Stromatolites ( ) or stromatoliths () are layered Sedimentary rock, sedimentary formation of rocks, formations (microbialite) that are created mainly by Photosynthesis, photosynthetic microorganisms such as cyanobacteria, sulfate-reducing micr ...

fossils discovered in 3.7 billion-year-old rocks. In 2015, possible "remains of biotic life" were found in 4.1 billion-year-old rocks. In 2017 putative evidence of possibly the oldest forms of life on Earth was reported in the form of fossilized microorganism

A microorganism, or microbe, is an organism of microscopic scale, microscopic size, which may exist in its unicellular organism, single-celled form or as a Colony (biology)#Microbial colonies, colony of cells. The possible existence of unseen ...

s discovered in hydrothermal vent

Hydrothermal vents are fissures on the seabed from which geothermally heated water discharges. They are commonly found near volcanically active places, areas where tectonic plates are moving apart at mid-ocean ridges, ocean basins, and hot ...

precipitates that may have lived as early as 4.28 billion years ago, not long after the oceans formed 4.4 billion years ago, and not long after the formation of the Earth 4.54 billion years ago.

Microbial mats of coexisting bacteria

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one Cell (biology), biological cell. They constitute a large domain (biology), domain of Prokaryote, prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micr ...

and archaea

Archaea ( ) is a Domain (biology), domain of organisms. Traditionally, Archaea only included its Prokaryote, prokaryotic members, but this has since been found to be paraphyletic, as eukaryotes are known to have evolved from archaea. Even thou ...

were the dominant form of life in the early Archean Eon and many of the major steps in early evolution are thought to have taken place in this environment. The evolution of photosynthesis

Photosynthesis ( ) is a system of biological processes by which photosynthetic organisms, such as most plants, algae, and cyanobacteria, convert light energy, typically from sunlight, into the chemical energy necessary to fuel their metabo ...

around 3.5 Ga resulted in a buildup of its waste product oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

in the atmosphere, leading to the great oxygenation event beginning around 2.4 Ga.

The earliest evidence of eukaryotes dates from 1.85 Ga, and while they may have been present earlier, their diversification accelerated when they started using oxygen in their metabolism

Metabolism (, from ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run cellular processes; the co ...

. Later, around 1.7 Ga, multicellular organism

A multicellular organism is an organism that consists of more than one cell (biology), cell, unlike unicellular organisms. All species of animals, Embryophyte, land plants and most fungi are multicellular, as are many algae, whereas a few organism ...

s began to appear, with differentiated cells performing specialised functions.

A stream of airborne microorganisms, including prokaryotes, circles the planet above weather systems but below commercial air lanes. Some peripatetic microorganisms are swept up from terrestrial dust storms, but most originate from marine microorganisms in sea spray. In 2018, scientists reported that hundreds of millions of viruses and tens of millions of bacteria are deposited daily on every square meter around the planet.

Microscopic life undersea is diverse and still poorly understood, such as for the role of

A stream of airborne microorganisms, including prokaryotes, circles the planet above weather systems but below commercial air lanes. Some peripatetic microorganisms are swept up from terrestrial dust storms, but most originate from marine microorganisms in sea spray. In 2018, scientists reported that hundreds of millions of viruses and tens of millions of bacteria are deposited daily on every square meter around the planet.

Microscopic life undersea is diverse and still poorly understood, such as for the role of virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living Cell (biology), cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea. Viruses are ...

es in marine ecosystems. Most marine viruses are bacteriophage

A bacteriophage (), also known informally as a phage (), is a virus that infects and replicates within bacteria. The term is derived . Bacteriophages are composed of proteins that Capsid, encapsulate a DNA or RNA genome, and may have structu ...

s, which are harmless to plants and animals, but are essential to the regulation of saltwater and freshwater ecosystems. They infect and destroy bacteria and archaea in aquatic microbial communities, and are the most important mechanism of recycling carbon in the marine environment. The organic molecules released from the dead bacterial cells stimulate fresh bacterial and algal growth. Viral activity may also contribute to the biological pump

The biological pump (or ocean carbon biological pump or marine biological carbon pump) is the ocean's biologically driven Carbon sequestration, sequestration of carbon from the atmosphere and land runoff to the ocean interior and seafloor sedim ...

, the process whereby carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalence, tetravalent—meaning that its atoms are able to form up to four covalent bonds due to its valence shell exhibiting 4 ...

is sequestered in the deep ocean.

Marine bacteria

Bacteria

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one Cell (biology), biological cell. They constitute a large domain (biology), domain of Prokaryote, prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micr ...

constitute a large domain of prokaryotic

A prokaryote (; less commonly spelled procaryote) is a single-celled organism whose cell lacks a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Ancient Greek (), meaning 'before', and (), meaning 'nut' ...

microorganism

A microorganism, or microbe, is an organism of microscopic scale, microscopic size, which may exist in its unicellular organism, single-celled form or as a Colony (biology)#Microbial colonies, colony of cells. The possible existence of unseen ...

s. Typically a few micrometre

The micrometre (English in the Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth English as used by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures; SI symbol: μm) or micrometer (American English), also commonly known by the non-SI term micron, is a uni ...

s in length, bacteria have a number of shapes, ranging from spheres to rods and spirals. Bacteria were among the first life forms to appear on Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to Planetary habitability, harbor life. This is enabled by Earth being an ocean world, the only one in the Solar System sustaining liquid surface water. Almost all ...

, and are present in most of its habitat

In ecology, habitat refers to the array of resources, biotic factors that are present in an area, such as to support the survival and reproduction of a particular species. A species' habitat can be seen as the physical manifestation of its ...

s. Bacteria inhabit soil, water, acidic hot springs, radioactive waste

Radioactive waste is a type of hazardous waste that contains radioactive material. It is a result of many activities, including nuclear medicine, nuclear research, nuclear power generation, nuclear decommissioning, rare-earth mining, and nuclear ...

, and the deep portions of Earth's crust

Earth's crust is its thick outer shell of rock, referring to less than one percent of the planet's radius and volume. It is the top component of the lithosphere, a solidified division of Earth's layers that includes the crust and the upper ...

. Bacteria also live in symbiotic

Symbiosis (Ancient Greek : living with, companionship < : together; and ''bíōsis'': living) is any type of a close and long-term biolo ...

and parasitic relationships with plants and animals.

Once regarded as plant

Plants are the eukaryotes that form the Kingdom (biology), kingdom Plantae; they are predominantly Photosynthesis, photosynthetic. This means that they obtain their energy from sunlight, using chloroplasts derived from endosymbiosis with c ...

s constituting the class ''Schizomycetes'', bacteria are now classified as prokaryotes

A prokaryote (; less commonly spelled procaryote) is a single-celled organism whose cell lacks a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Ancient Greek (), meaning 'before', and (), meaning 'nut' ...

. Unlike cells of animals and other eukaryote

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the Domain (biology), domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose Cell (biology), cells have a membrane-bound cell nucleus, nucleus. All animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms ...

s, bacterial cells do not contain a nucleus and rarely harbour membrane-bound organelle

In cell biology, an organelle is a specialized subunit, usually within a cell (biology), cell, that has a specific function. The name ''organelle'' comes from the idea that these structures are parts of cells, as Organ (anatomy), organs are to th ...

s. Although the term ''bacteria'' traditionally included all prokaryotes, the scientific classification

image:Hierarchical clustering diagram.png, 280px, Generalized scheme of taxonomy

Taxonomy is a practice and science concerned with classification or categorization. Typically, there are two parts to it: the development of an underlying scheme o ...

changed after the discovery in the 1990s that prokaryotes consist of two very different groups of organisms that evolved

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

from an ancient common ancestor. These evolutionary domains are called ''Bacteria'' and ''Archaea

Archaea ( ) is a Domain (biology), domain of organisms. Traditionally, Archaea only included its Prokaryote, prokaryotic members, but this has since been found to be paraphyletic, as eukaryotes are known to have evolved from archaea. Even thou ...

''.

The ancestors of modern bacteria were unicellular microorganisms that were the first forms of life to appear on Earth, about 4 billion years ago. For about 3 billion years, most organisms were microscopic, and bacteria and archaea were the dominant forms of life. Although bacterial fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserve ...

s exist, such as stromatolite

Stromatolites ( ) or stromatoliths () are layered Sedimentary rock, sedimentary formation of rocks, formations (microbialite) that are created mainly by Photosynthesis, photosynthetic microorganisms such as cyanobacteria, sulfate-reducing micr ...

s, their lack of distinctive morphology prevents them from being used to examine the history of bacterial evolution, or to date the time of origin of a particular bacterial species. However, gene sequences can be used to reconstruct the bacterial phylogeny

A phylogenetic tree or phylogeny is a graphical representation which shows the evolutionary history between a set of species or Taxon, taxa during a specific time.Felsenstein J. (2004). ''Inferring Phylogenies'' Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, M ...

, and these studies indicate that bacteria diverged first from the archaeal/eukaryotic lineage.

Bacteria were also involved in the second great evolutionary divergence, that of the archaea and eukaryotes. Here, eukaryotes resulted from the entering of ancient bacteria into endosymbiotic

An endosymbiont or endobiont is an organism that lives within the body or cells of another organism. Typically the two organisms are in a mutualistic relationship. Examples are nitrogen-fixing bacteria (called rhizobia), which live in the root ...

associations with the ancestors of eukaryotic cells, which were themselves possibly related to the Archaea

Archaea ( ) is a Domain (biology), domain of organisms. Traditionally, Archaea only included its Prokaryote, prokaryotic members, but this has since been found to be paraphyletic, as eukaryotes are known to have evolved from archaea. Even thou ...

. This involved the engulfment by proto-eukaryotic cells of alphaproteobacteria

''Alphaproteobacteria'' or ''α-proteobacteria'', also called ''α-Purple bacteria'' in earlier literature, is a class of bacteria in the phylum '' Pseudomonadota'' (formerly "Proteobacteria"). The '' Magnetococcales'' and '' Mariprofundales'' ar ...

l symbionts to form either mitochondria

A mitochondrion () is an organelle found in the cells of most eukaryotes, such as animals, plants and fungi. Mitochondria have a double membrane structure and use aerobic respiration to generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is us ...

or hydrogenosomes, which are still found in all known Eukarya. Later on, some eukaryotes that already contained mitochondria also engulfed cyanobacterial-like organisms. This led to the formation of chloroplast

A chloroplast () is a type of membrane-bound organelle, organelle known as a plastid that conducts photosynthesis mostly in plant cell, plant and algae, algal cells. Chloroplasts have a high concentration of chlorophyll pigments which captur ...

s in algae and plants. There are also some algae that originated from even later endosymbiotic events. Here, eukaryotes engulfed a eukaryotic algae that developed into a "second-generation" plastid. This is known as secondary endosymbiosis.

Bacteria grow to a fixed size and then reproduce through binary fission

Binary may refer to:

Science and technology Mathematics

* Binary number, a representation of numbers using only two values (0 and 1) for each digit

* Binary function, a function that takes two arguments

* Binary operation, a mathematical o ...

, a form of asexual reproduction

Asexual reproduction is a type of reproduction that does not involve the fusion of gametes or change in the number of chromosomes. The offspring that arise by asexual reproduction from either unicellular or multicellular organisms inherit the f ...

. Under optimal conditions, bacteria can grow and divide extremely rapidly, and bacterial populations can double as quickly as every 9.8 minutes.

'' Pelagibacter ubique'' and its relatives may be the most abundant microorganisms in the ocean, and it has been claimed that they are possibly the most abundant bacteria in the world. They make up about 25% of all microbial plankton

Plankton are the diverse collection of organisms that drift in Hydrosphere, water (or atmosphere, air) but are unable to actively propel themselves against ocean current, currents (or wind). The individual organisms constituting plankton are ca ...

cells, and in the summer they may account for approximately half the cells present in temperate ocean surface water. The total abundance of ''P. ubique'' and relatives is estimated to be about 2 × 1028 microbes. However, it was reported in ''Nature

Nature is an inherent character or constitution, particularly of the Ecosphere (planetary), ecosphere or the universe as a whole. In this general sense nature refers to the Scientific law, laws, elements and phenomenon, phenomena of the physic ...

'' in February 2013 that the bacteriophage

A bacteriophage (), also known informally as a phage (), is a virus that infects and replicates within bacteria. The term is derived . Bacteriophages are composed of proteins that Capsid, encapsulate a DNA or RNA genome, and may have structu ...

HTVC010P, which attacks ''P. ubique'', has been discovered and is probably the most common organism on the planet.

'' Roseobacter'' is also one of the most abundant and versatile microorganisms in the ocean. They are diversified across different types of marine habitats, from coastal to open oceans and from sea ice to sea floor, and make up about 25% of coastal marine bacteria. Members of the '' Roseobacter'' genus play important roles in marine biogeochemical cycles and climate change, processing a significant portion of the total carbon in the marine environment. They form symbiotic relationships which allow them to degrade aromatic compounds and uptake trace metals. They are widely used in aquaculture and quorum sensing. During algal blooms, 20–30% of the prokaryotic community are Roseobacter.

The largest known bacterium, the marine ''Thiomargarita namibiensis

''Thiomargarita namibiensis'' is a gram-negative, Facultative anaerobic organism, facultative anaerobic, coccus, coccoid bacterium found in South Africa's ocean sediments of the continental shelf of Namibia. The genus name ''Thiomargarita'' mean ...

'', can be visible to the naked eye and sometimes attains .

Cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria ( ) are a group of autotrophic gram-negative bacteria that can obtain biological energy via oxygenic photosynthesis. The name "cyanobacteria" () refers to their bluish green (cyan) color, which forms the basis of cyanobacteri ...

were the first organisms to evolve an ability to turn sunlight into chemical energy. They form a phylum (division) of bacteria which range from unicellular to filamentous and include colonial species. They are found almost everywhere on earth: in damp soil, in both freshwater and marine environments, and even on Antarctic rocks. In particular, some species occur as drifting cells floating in the ocean, and as such were amongst the first of the phytoplankton

Phytoplankton () are the autotrophic (self-feeding) components of the plankton community and a key part of ocean and freshwater Aquatic ecosystem, ecosystems. The name comes from the Greek language, Greek words (), meaning 'plant', and (), mea ...

.

The first primary producers that used photosynthesis were oceanic cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria ( ) are a group of autotrophic gram-negative bacteria that can obtain biological energy via oxygenic photosynthesis. The name "cyanobacteria" () refers to their bluish green (cyan) color, which forms the basis of cyanobacteri ...

about 2.3 billion years ago. The release of molecular oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

by cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria ( ) are a group of autotrophic gram-negative bacteria that can obtain biological energy via oxygenic photosynthesis. The name "cyanobacteria" () refers to their bluish green (cyan) color, which forms the basis of cyanobacteri ...

as a by-product of photosynthesis induced global changes in the Earth's environment. Because oxygen was toxic to most life on Earth at the time, this led to the near-extinction of oxygen-intolerant organisms, a dramatic change which redirected the evolution of the major animal and plant species.

Cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria ( ) are a group of autotrophic gram-negative bacteria that can obtain biological energy via oxygenic photosynthesis. The name "cyanobacteria" () refers to their bluish green (cyan) color, which forms the basis of cyanobacteri ...

blooms can contain lethal cyanotoxin

Cyanotoxins are toxins produced by cyanobacteria (also known as blue-green algae). Cyanobacteria are found almost everywhere, but particularly in lakes and in the ocean where, under high concentration of phosphorus conditions, they reproduce exp ...

s.

Prochlorococcus

''Prochlorococcus'' is a genus of very small (0.6 μm) marine cyanobacteria with an unusual pigmentation ( chlorophyll ''a2'' and ''b2''). These bacteria belong to the photosynthetic picoplankton and are probably the most abundant photosyn ...

'', discovered in 1986, forms today an important part of the base of the ocean food chain

A food chain is a linear network of links in a food web, often starting with an autotroph (such as grass or algae), also called a producer, and typically ending at an apex predator (such as grizzly bears or killer whales), detritivore (such as ...

and accounts for much of the photosynthesis of the open ocean and an estimated 20% of the oxygen in the Earth's atmosphere. It is possibly the most plentiful genus on Earth: a single millilitre of surface seawater may contain 100,000 cells or more.

Originally, biologists classified cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria ( ) are a group of autotrophic gram-negative bacteria that can obtain biological energy via oxygenic photosynthesis. The name "cyanobacteria" () refers to their bluish green (cyan) color, which forms the basis of cyanobacteri ...

as an algae, and referred to it as "blue-green algae". The more recent view is that cyanobacteria are bacteria, and hence are not even in the same Kingdom as algae. Most authorities exclude all prokaryotes

A prokaryote (; less commonly spelled procaryote) is a single-celled organism whose cell lacks a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Ancient Greek (), meaning 'before', and (), meaning 'nut' ...

, and hence cyanobacteria from the definition of algae.

Other bacteria

Other marine bacteria, apart from cyanobacteria, are ubiquitous or can play important roles in the ocean. These include the opportunistic copiotroph, '' Alteromonas macleodii''.Marine archaea

The

The archaea

Archaea ( ) is a Domain (biology), domain of organisms. Traditionally, Archaea only included its Prokaryote, prokaryotic members, but this has since been found to be paraphyletic, as eukaryotes are known to have evolved from archaea. Even thou ...

(Greek for ''ancient'') constitute a domain and kingdom of single-celled microorganism

A microorganism, or microbe, is an organism of microscopic scale, microscopic size, which may exist in its unicellular organism, single-celled form or as a Colony (biology)#Microbial colonies, colony of cells. The possible existence of unseen ...

s. These microbes are prokaryotes

A prokaryote (; less commonly spelled procaryote) is a single-celled organism whose cell lacks a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Ancient Greek (), meaning 'before', and (), meaning 'nut' ...

, meaning they have no cell nucleus

The cell nucleus (; : nuclei) is a membrane-bound organelle found in eukaryote, eukaryotic cell (biology), cells. Eukaryotic cells usually have a single nucleus, but a few cell types, such as mammalian red blood cells, have #Anucleated_cells, ...

or any other membrane-bound organelle

In cell biology, an organelle is a specialized subunit, usually within a cell (biology), cell, that has a specific function. The name ''organelle'' comes from the idea that these structures are parts of cells, as Organ (anatomy), organs are to th ...

s in their cells.

Archaea were initially classified as bacteria

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one Cell (biology), biological cell. They constitute a large domain (biology), domain of Prokaryote, prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micr ...

, but this classification is outdated. Archaeal cells have unique properties separating them from the other two domains of life, Bacteria and Eukaryota

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the Domain (biology), domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose Cell (biology), cells have a membrane-bound cell nucleus, nucleus. All animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms ...

. The Archaea are further divided into multiple recognized phyla

Phyla, the plural of ''phylum'', may refer to:

* Phylum, a biological taxon between Kingdom and Class

* by analogy, in linguistics, a large division of possibly related languages, or a major language family which is not subordinate to another

Phy ...

. Classification is difficult because the majority have not been isolated in the laboratory and have only been detected by analysis of their nucleic acid

Nucleic acids are large biomolecules that are crucial in all cells and viruses. They are composed of nucleotides, which are the monomer components: a pentose, 5-carbon sugar, a phosphate group and a nitrogenous base. The two main classes of nuclei ...

s in samples from their environment.

Bacteria and archaea are generally similar in size and shape, although a few archaea have very strange shapes, such as the flat and square-shaped cells of ''Haloquadratum walsbyi

''Haloquadratum walsbyi'' is a species of Archaea in the genus ''Haloquadratum'', known for its square shape and halophilic nature.

First discovered in a brine pool in the Sinai Peninsula of Egypt, ''H. walsbyi'' is noted for its flat, square- ...

''. Despite this morphological similarity to bacteria, archaea possess gene

In biology, the word gene has two meanings. The Mendelian gene is a basic unit of heredity. The molecular gene is a sequence of nucleotides in DNA that is transcribed to produce a functional RNA. There are two types of molecular genes: protei ...

s and several metabolic pathway

In biochemistry, a metabolic pathway is a linked series of chemical reactions occurring within a cell (biology), cell. The reactants, products, and Metabolic intermediate, intermediates of an enzymatic reaction are known as metabolites, which are ...

s that are more closely related to those of eukaryotes, notably the enzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different mol ...

s involved in transcription and translation

Translation is the communication of the semantics, meaning of a #Source and target languages, source-language text by means of an Dynamic and formal equivalence, equivalent #Source and target languages, target-language text. The English la ...

. Other aspects of archaeal biochemistry are unique, such as their reliance on ether lipid

In biochemistry, an ether lipid refers to any lipid in which the lipid "tail" group is attached to the glycerol backbone via an ether, ether bond at any position. In contrast, conventional glycerophospholipids and triglycerides are triesters. St ...

s in their cell membrane

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of a cell from the outside environment (the extr ...

s, such as archaeols. Archaea use more energy sources than eukaryotes: these range from organic compounds

Some chemical authorities define an organic compound as a chemical compound that contains a carbon–hydrogen or carbon–carbon bond; others consider an organic compound to be any chemical compound that contains carbon. For example, carbon-co ...

, such as sugars, to ammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic chemical compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the chemical formula, formula . A Binary compounds of hydrogen, stable binary hydride and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinctive pu ...

, metal ions

A metal () is a material that, when polished or fractured, shows a lustrous appearance, and conducts electricity and heat relatively well. These properties are all associated with having electrons available at the Fermi level, as against n ...

or even hydrogen gas

Hydrogen is a chemical element; it has symbol H and atomic number 1. It is the lightest and most abundant chemical element in the universe, constituting about 75% of all normal matter. Under standard conditions, hydrogen is a gas of diatomi ...

. Salt-tolerant archaea (the Haloarchaea

Haloarchaea (halophilic archaea, halophilic archaebacteria, halobacteria) are a class of prokaryotic archaea under the phylum Euryarchaeota, found in water saturated or nearly saturated with salt. 'Halobacteria' are now recognized as archaea r ...

) use sunlight as an energy source, and other species of archaea fix carbon; however, unlike plants and cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria ( ) are a group of autotrophic gram-negative bacteria that can obtain biological energy via oxygenic photosynthesis. The name "cyanobacteria" () refers to their bluish green (cyan) color, which forms the basis of cyanobacteri ...

, no known species of archaea does both. Archaea reproduce asexually by binary fission

Binary may refer to:

Science and technology Mathematics

* Binary number, a representation of numbers using only two values (0 and 1) for each digit

* Binary function, a function that takes two arguments

* Binary operation, a mathematical o ...

, fragmentation, or budding

Budding or blastogenesis is a type of asexual reproduction in which a new organism develops from an outgrowth or bud due to cell division at one particular site. For example, the small bulb-like projection coming out from the yeast cell is kno ...

; unlike bacteria and eukaryotes, no known species forms spore

In biology, a spore is a unit of sexual reproduction, sexual (in fungi) or asexual reproduction that may be adapted for biological dispersal, dispersal and for survival, often for extended periods of time, in unfavourable conditions. Spores fo ...

s.

Archaea are particularly numerous in the oceans, and the archaea in plankton

Plankton are the diverse collection of organisms that drift in Hydrosphere, water (or atmosphere, air) but are unable to actively propel themselves against ocean current, currents (or wind). The individual organisms constituting plankton are ca ...

may be one of the most abundant groups of organisms on the planet. Archaea are a major part of Earth's life and may play roles in both the carbon cycle

The carbon cycle is a part of the biogeochemical cycle where carbon is exchanged among the biosphere, pedosphere, geosphere, hydrosphere, and atmosphere of Earth. Other major biogeochemical cycles include the nitrogen cycle and the water cycl ...

and the nitrogen cycle

The nitrogen cycle is the biogeochemical cycle by which nitrogen is converted into multiple chemical forms as it circulates among atmosphere, atmospheric, terrestrial ecosystem, terrestrial, and marine ecosystems. The conversion of nitrogen can ...

. Thermoproteota

The Thermoproteota are prokaryotes that have been classified as a phylum (biology), phylum of the domain Archaea. Initially, the Thermoproteota were thought to be sulfur-dependent extremophiles but recent studies have identified characteristic T ...

(also called Crenarchaeota or eocytes) are a phylum of archaea thought to be very abundant in marine environments and one of the main contributors to the fixation of carbon.

Halobacteria

Haloarchaea (halophilic archaea, halophilic archaebacteria, halobacteria) are a class (biology), class of prokaryotic archaea under the phylum Euryarchaeota, found in water Saturated and unsaturated compounds, saturated or nearly saturated with ...

, found in water near saturated with salt, are now recognised as archaea.

File:Haloquadratum walsbyi00.jpg, Flat, square-shaped cells of the archaea ''Haloquadratum walsbyi

''Haloquadratum walsbyi'' is a species of Archaea in the genus ''Haloquadratum'', known for its square shape and halophilic nature.

First discovered in a brine pool in the Sinai Peninsula of Egypt, ''H. walsbyi'' is noted for its flat, square- ...

''

File:Methanosarcina barkeri fusaro.gif, ''Methanosarcina barkeri

''Methanosarcina barkeri'' is the type species of the genus ''Methanosarcina'', characterized by its wide range of substrates used in methanogenesis. While most known methanogens produce methane from H2 and CO2, ''M. barkeri'' can also dismutate ...

'', a marine archaea that produces methane

Methane ( , ) is a chemical compound with the chemical formula (one carbon atom bonded to four hydrogen atoms). It is a group-14 hydride, the simplest alkane, and the main constituent of natural gas. The abundance of methane on Earth makes ...

File:Thermophile bacteria2.jpg, Thermophile

A thermophile is a type of extremophile that thrives at relatively high temperatures, between . Many thermophiles are archaea, though some of them are bacteria and fungi. Thermophilic eubacteria are suggested to have been among the earliest bacte ...

s, such as '' Pyrolobus fumarii'', survive well over .

'' Nanoarchaeum equitans'' is a species of marine archaea discovered in 2002 in a

'' Nanoarchaeum equitans'' is a species of marine archaea discovered in 2002 in a hydrothermal vent

Hydrothermal vents are fissures on the seabed from which geothermally heated water discharges. They are commonly found near volcanically active places, areas where tectonic plates are moving apart at mid-ocean ridges, ocean basins, and hot ...

. It is a thermophile

A thermophile is a type of extremophile that thrives at relatively high temperatures, between . Many thermophiles are archaea, though some of them are bacteria and fungi. Thermophilic eubacteria are suggested to have been among the earliest bacte ...

that grows in temperatures at about . ''Nanoarchaeum'' appears to be an obligate symbiont on the archaeon '' Ignicoccus''. It must stay in contact with the host organism to survive since ''Nanoarchaeum equitans'' cannot synthesize lipids but obtains them from its host. Its cells are only 400 nm in diameter, making it one of the smallest known cellular organisms, and the smallest known archaeon.

Marine archaea have been classified as follows:See especially Fig. 4 in

* Marine Group I (MG-I or MGI): marine Nitrososphaerota

The Nitrososphaerota (syn. Thaumarchaeota) are a phylum of the Archaea proposed in 2008 after the genome of '' Cenarchaeum symbiosum'' was sequenced and found to differ significantly from other members of the hyperthermophilic phylum Thermopr ...

with subgroups Ia (aka I.a) up to Id

* Marine Group II (MG-II): marine Euryarchaeota

Methanobacteriota is a phylum in the domain Archaea.

Taxonomy

The phylum ''Methanobacteriota'' was introduced to prokaryotic nomenclature in 2023. It contains following classes:

*Archaeoglobi Garrity & Holt (2002)

*Halobacteria Grant ''et al ...

, order Poseidoniales with subgroups IIa up to IId (IIa resembling Poseidoniaceae, IIb resembling Thalassarchaceae)Viruses parasiting MGII are classified as magroviruses * Marine Group III (MG-III): also marine Euryarchaeota, Marine Benthic Group D * Marine Group IV (MG-IV): also marine Euryarchaeota

Trophic mode

Prokaryote metabolism is classified into nutritional groups on the basis of three major criteria: the source ofenergy

Energy () is the physical quantity, quantitative physical property, property that is transferred to a physical body, body or to a physical system, recognizable in the performance of Work (thermodynamics), work and in the form of heat and l ...

, the electron donor

In chemistry, an electron donor is a chemical entity that transfers electrons to another compound. It is a reducing agent that, by virtue of its donating electrons, is itself oxidized in the process. An obsolete definition equated an electron dono ...

s used, and the source of carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalence, tetravalent—meaning that its atoms are able to form up to four covalent bonds due to its valence shell exhibiting 4 ...

used for growth.

Marine prokaryotes have diversified greatly throughout their long existence. The metabolism of prokaryotes is far more varied than that of eukaryotes, leading to many highly distinct prokaryotic types. For example, in addition to using photosynthesis

Photosynthesis ( ) is a system of biological processes by which photosynthetic organisms, such as most plants, algae, and cyanobacteria, convert light energy, typically from sunlight, into the chemical energy necessary to fuel their metabo ...

or organic compound

Some chemical authorities define an organic compound as a chemical compound that contains a carbon–hydrogen or carbon–carbon bond; others consider an organic compound to be any chemical compound that contains carbon. For example, carbon-co ...

s for energy, as eukaryotes do, marine prokaryotes may obtain energy from inorganic compound

An inorganic compound is typically a chemical compound that lacks carbon–hydrogen bondsthat is, a compound that is not an organic compound. The study of inorganic compounds is a subfield of chemistry known as ''inorganic chemistry''.

Inorgan ...

s such as hydrogen sulfide

Hydrogen sulfide is a chemical compound with the formula . It is a colorless chalcogen-hydride gas, and is toxic, corrosive, and flammable. Trace amounts in ambient atmosphere have a characteristic foul odor of rotten eggs. Swedish chemist ...

. This enables marine prokaryotes to thrive as extremophile

An extremophile () is an organism that is able to live (or in some cases thrive) in extreme environments, i.e., environments with conditions approaching or stretching the limits of what known life can adapt to, such as extreme temperature, press ...

s in harsh environments as cold as the ice surface of Antarctica, studied in cryobiology

Cryobiology is the branch of biology that studies the effects of low temperatures on living things within Earth's cryosphere or in science. The word cryobiology is derived from the Greek words κρῧος ryos "cold", βίος ios "life", and λ ...

, as hot as undersea hydrothermal vent

Hydrothermal vents are fissures on the seabed from which geothermally heated water discharges. They are commonly found near volcanically active places, areas where tectonic plates are moving apart at mid-ocean ridges, ocean basins, and hot ...

s, or in high saline conditions as (halophile

A halophile (from the Greek word for 'salt-loving') is an extremophile that thrives in high salt

In common usage, salt is a mineral composed primarily of sodium chloride (NaCl). When used in food, especially in granulated form, it is more ...

s). Some marine prokaryotes live symbiotic

Symbiosis (Ancient Greek : living with, companionship < : together; and ''bíōsis'': living) is any type of a close and long-term biolo ...

ally in or on the bodies of other marine organisms.

* Phototrophy is a particularly significant marker that should always play a primary role in bacterial classification.

* Aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria (AAPBs) are widely distributed marine

* Phototrophy is a particularly significant marker that should always play a primary role in bacterial classification.

* Aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria (AAPBs) are widely distributed marine plankton

Plankton are the diverse collection of organisms that drift in Hydrosphere, water (or atmosphere, air) but are unable to actively propel themselves against ocean current, currents (or wind). The individual organisms constituting plankton are ca ...

that may constitute over 10% of the open ocean microbial community. Marine AAPBs are classified in two marine ('' Erythrobacter'' and '' Roseobacter'') genera. They can be particularly abundant in oligotrophic conditions where they were found to be 24% of the community. These are heterotrophic

A heterotroph (; ) is an organism that cannot produce its own food, instead taking nutrition from other sources of organic carbon, mainly plant or animal matter. In the food chain, heterotrophs are primary, secondary and tertiary consumers, but ...

organisms that use light to produce energy, but are unable to utilise carbon dioxide as their primary carbon source. Most are obligately aerobic, meaning they require oxygen to grow. Current data suggests that marine bacteria have generation times of several days, whereas new evidence exists that shows AAPB to have a much shorter generation time. Coastal/shelf waters often have greater amounts of AAPBs, some as high as 13.51% AAPB%. Phytoplankton also affect AAPB%, but little research has been performed in this area. They can also be abundant in various oligotrophic conditions, including the most oligotrophic regime of the world ocean. They are globally distributed in the euphotic zone and represent a hitherto unrecognized component of the marine microbial community that appears to be critical to the cycling of both organic and inorganic carbon in the ocean.

* Purple bacteria:

* Zetaproteobacteria: are iron-oxidizing neutrophilic chemolithoautotrophs, distributed worldwide in estuaries and marine habitats.

* Hydrogen oxidizing bacteria are facultative autotrophs that can be divided into aerobes and anaerobes. The former use hydrogen

Hydrogen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol H and atomic number 1. It is the lightest and abundance of the chemical elements, most abundant chemical element in the universe, constituting about 75% of all baryon, normal matter ...

as an electron donor

In chemistry, an electron donor is a chemical entity that transfers electrons to another compound. It is a reducing agent that, by virtue of its donating electrons, is itself oxidized in the process. An obsolete definition equated an electron dono ...

and oxygen as an acceptor while the latter use sulphate or nitrogen dioxide as electron acceptor

An electron acceptor is a chemical entity that accepts electrons transferred to it from another compound. Electron acceptors are oxidizing agents.

The electron accepting power of an electron acceptor is measured by its redox potential.

In the ...

s.

Motility

Motility

Motility is the ability of an organism to move independently using metabolism, metabolic energy. This biological concept encompasses movement at various levels, from whole organisms to cells and subcellular components.

Motility is observed in ...

is the ability of an organism

An organism is any life, living thing that functions as an individual. Such a definition raises more problems than it solves, not least because the concept of an individual is also difficult. Many criteria, few of them widely accepted, have be ...

to move independently, using metabolic energy.

Flagellar motility

Prokaryotes, both bacteria and archaea, primarily useflagella

A flagellum (; : flagella) (Latin for 'whip' or 'scourge') is a hair-like appendage that protrudes from certain plant and animal sperm cells, from fungal spores ( zoospores), and from a wide range of microorganisms to provide motility. Many pr ...

for locomotion.

* Bacterial flagella are helical filaments, each with a rotary motor at its base which can turn clockwise or counterclockwise. They provide two of several kinds of bacterial motility.

* Archaeal flagella are called ''archaella'', and function in much the same way as bacterial flagella. Structurally the archaellum is superficially similar to a bacterial flagellum, but it differs in many details and is considered non- homologous.

The rotary motor model used by bacteria uses the protons of an electrochemical gradient

An electrochemical gradient is a gradient of electrochemical potential, usually for an ion that can move across a membrane. The gradient consists of two parts:

* The chemical gradient, or difference in Concentration, solute concentration across ...

in order to move their flagella. Torque

In physics and mechanics, torque is the rotational analogue of linear force. It is also referred to as the moment of force (also abbreviated to moment). The symbol for torque is typically \boldsymbol\tau, the lowercase Greek letter ''tau''. Wh ...

in the flagella of bacteria is created by particles that conduct protons around the base of the flagellum. The direction of rotation of the flagella in bacteria comes from the occupancy of the proton channels along the perimeter of the flagellar motor.

Some eukaryotic cells also use flagella—and they can be found in some protists and plants as well as animal cells. Eukaryotic flagella are complex cellular projections that lash back and forth, rather than in a circular motion. Prokaryotic flagella use a rotary motor, and the eukaryotic flagella use a complex sliding filament system. Eukaryotic flagella are ATP-driven, while prokaryotic flagella can be ATP-driven (archaea) or proton-driven (bacteria).

Twitching motility

Twitching motility

Twitch may refer to:

Biology

* Muscle contraction

** Convulsion, rapid and repeated muscle contraction and relaxation

** Fasciculation, a small, local, involuntary muscle contraction

** Myoclonic twitch, a jerk usually caused by sudden muscle co ...

is a form of crawling bacterial motility used to move over surfaces. Twitching is mediated by the activity of hair-like filaments called type IV pili which extend from the cell's exterior, bind to surrounding solid substrates and retract, pulling the cell forwards in a manner similar to the action of a grappling hook. The name ''twitching motility'' is derived from the characteristic jerky and irregular motions of individual cells when viewed under the microscope.

Gliding motility

Gliding motility is a type of translocation that is independent of propulsive structures such asflagella

A flagellum (; : flagella) (Latin for 'whip' or 'scourge') is a hair-like appendage that protrudes from certain plant and animal sperm cells, from fungal spores ( zoospores), and from a wide range of microorganisms to provide motility. Many pr ...

or pili. Gliding allows microorganisms to travel along the surface of low aqueous films. The mechanisms of this motility are only partially known. The speed of gliding varies between organisms, and the reversal of direction is seemingly regulated by some sort of internal clock. For example, the apicomplexans are able to travel at fast rates between 1–10 μm/s. In contrast '' Myxococcus xanthus'' bacteria glide at a rate of 5 μm/min.

Swarming motility

Swarming motility is a rapid (2–10 μm/s) and coordinated translocation of a bacterial population across solid or semi-solid surfaces, and is an example of bacterial multicellularity and swarm behaviour. Swarming motility was first reported in 1972 by Jorgen Henrichsen.Non-motile

Non-motile species lack the ability and structures that would allow them to propel themselves, under their own power, through their environment. When non-motile bacteria are cultured in a stab tube, they only grow along the stab line. If the bacteria are mobile, the line will appear diffuse and extend into the medium.Taxis: Directed motion

Magnetotaxis

Magnetotactic bacteria orient themselves along the magnetic field lines ofEarth's magnetic field

Earth's magnetic field, also known as the geomagnetic field, is the magnetic field that extends from structure of Earth, Earth's interior out into space, where it interacts with the solar wind, a stream of charged particles emanating from ...

. This alignment is believed to aid these organisms in reaching regions of optimal oxygen concentration. To perform this task, these bacteria have biomineralised organelle

In cell biology, an organelle is a specialized subunit, usually within a cell (biology), cell, that has a specific function. The name ''organelle'' comes from the idea that these structures are parts of cells, as Organ (anatomy), organs are to th ...

s called magnetosomes that contain magnetic crystal

A crystal or crystalline solid is a solid material whose constituents (such as atoms, molecules, or ions) are arranged in a highly ordered microscopic structure, forming a crystal lattice that extends in all directions. In addition, macros ...

s. The biological phenomenon of microorganisms tending to move in response to the environment's magnetic characteristics is known as magnetotaxis

Magnetotaxis is a process implemented by a diverse group of Gram-negative bacteria that involves orienting and coordinating movement in response to Earth's magnetic field. This process is mainly carried out by microaerophilic and anaerobic bacter ...

. However, this term is misleading in that every other application of the term taxis

A taxis (; : taxes ) is the motility, movement of an organism in response to a Stimulus (physiology), stimulus such as light or the presence of food. Taxes are innate behavioural responses. A taxis differs from a tropism (turning response, often ...

involves a stimulus-response mechanism. In contrast to the magnetoreception of animals, the bacteria contain fixed magnets that force the bacteria into alignment—even dead cells are dragged into alignment, just like a compass needle.

Marine environments are generally characterized by low concentrations of nutrients kept in steady or intermittent motion by currents and turbulence. Marine bacteria have developed strategies, such as swimming and using directional sensing–response systems, to migrate towards favorable places in the nutrient gradients. Magnetotactic bacteria utilize Earth's magnetic field to facilitate downward swimming into the oxic–anoxic interface, which is the most favorable place for their persistence and proliferation, in chemically stratified sediments or water columns. Modified text was copied from this source, which is available under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Depending on their latitude and whether the bacteria are north or south of the equator, the Earth's magnetic field has one of the two possible polarities, and a direction that points with varying angles into the ocean depths, and away from the generally more oxygen rich surface. Aerotaxis is the response by which bacteria migrate to an optimal oxygen concentration in an oxygen gradient. Various experiments have clearly shown that

magnetotaxis

Magnetotaxis is a process implemented by a diverse group of Gram-negative bacteria that involves orienting and coordinating movement in response to Earth's magnetic field. This process is mainly carried out by microaerophilic and anaerobic bacter ...

and aerotaxis work in conjunction in magnetotactic bacteria. It has been shown that, in water droplets, one-way swimming magnetotactic bacteria can reverse their swimming direction and swim backwards under reducing conditions (less than optimal oxygen concentration), as opposed to oxic conditions (greater than optimal oxygen concentration).

Regardless of their morphology, all magnetotactic bacteria studied so far are motile by means of flagella. Marine magnetotactic bacteria in particular tend to possess an elaborate flagellar apparatus which can involve up to tens of thousands of flagella. However, despite extensive research in recent years, it has yet to be established whether magnetotactic bacteria steer their flagellar motors in response to their alignment in magnetic fields. Symbiosis

Symbiosis (Ancient Greek : living with, companionship < : together; and ''bíōsis'': living) is any type of a close and long-term biological interaction, between two organisms of different species. The two organisms, termed symbionts, can fo ...

with magnetotactic bacteria has been proposed as the explanation for magnetoreception in some marine protists. Research is underway on whether a similar relationship may underlie magnetoreception in vertebrate

Vertebrates () are animals with a vertebral column (backbone or spine), and a cranium, or skull. The vertebral column surrounds and protects the spinal cord, while the cranium protects the brain.

The vertebrates make up the subphylum Vertebra ...

s as well. The oldest unambiguous magnetofossils come from the Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 143.1 to 66 mya (unit), million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era (geology), Era, as well as the longest. At around 77.1 million years, it is the ...

chalk beds of southern England, though less certain reports of magnetofossils extend to 1.9 billion years old Gunflint Chert.

Gas vacuoles

Some marine prokaryotes possess gas vacuoles. Gas vacuole are nanocompartments freely permeable to gas which allow marine bacteria and archaea to control theirbuoyancy

Buoyancy (), or upthrust, is the force exerted by a fluid opposing the weight of a partially or fully immersed object (which may be also be a parcel of fluid). In a column of fluid, pressure increases with depth as a result of the weight of t ...

. They take the form of spindle-shaped membrane-bound vesicles, and are found in some plankton

Plankton are the diverse collection of organisms that drift in Hydrosphere, water (or atmosphere, air) but are unable to actively propel themselves against ocean current, currents (or wind). The individual organisms constituting plankton are ca ...

prokaryotes, including some ''Cyanobacteria