Marina Tsvetaeva on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

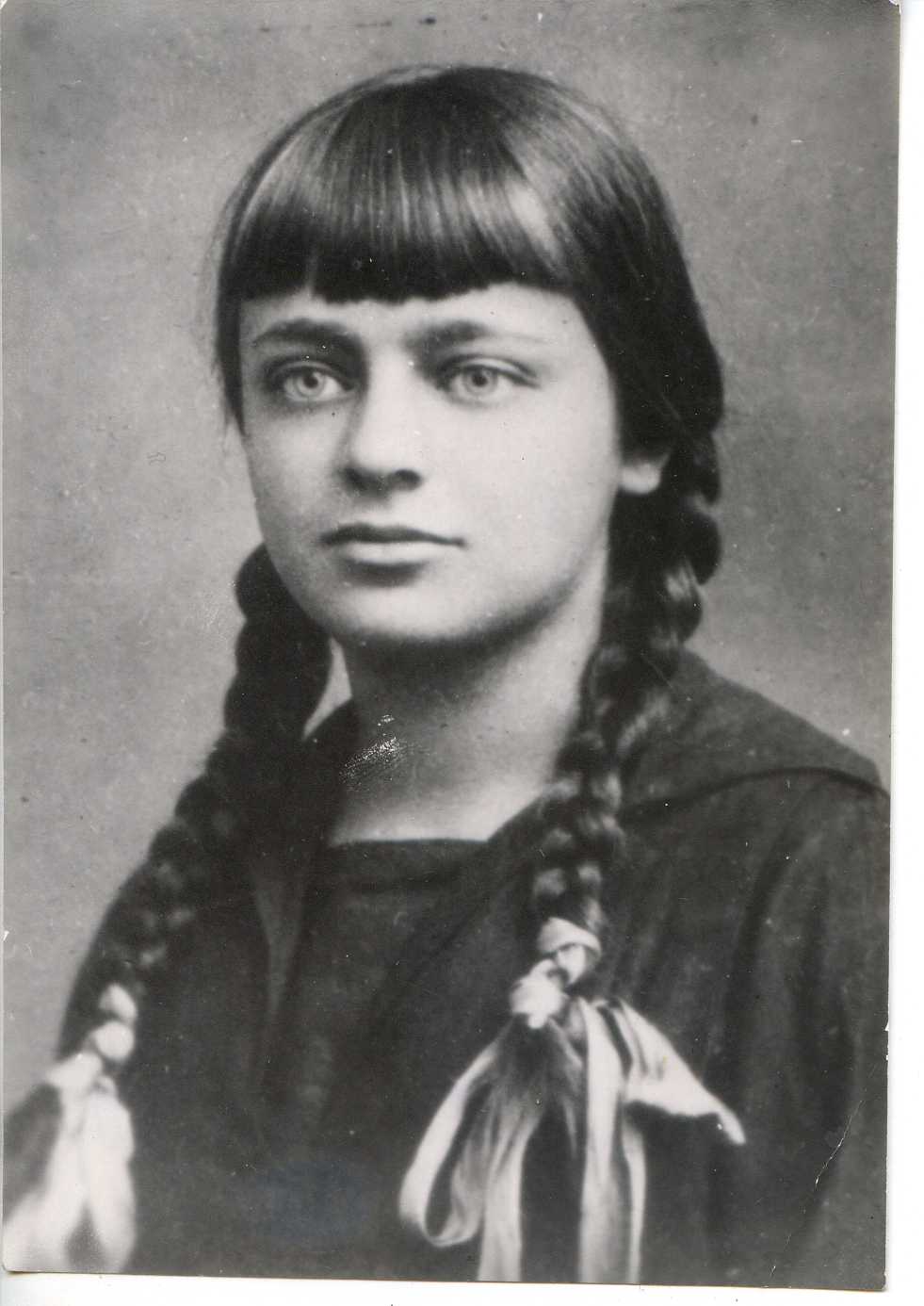

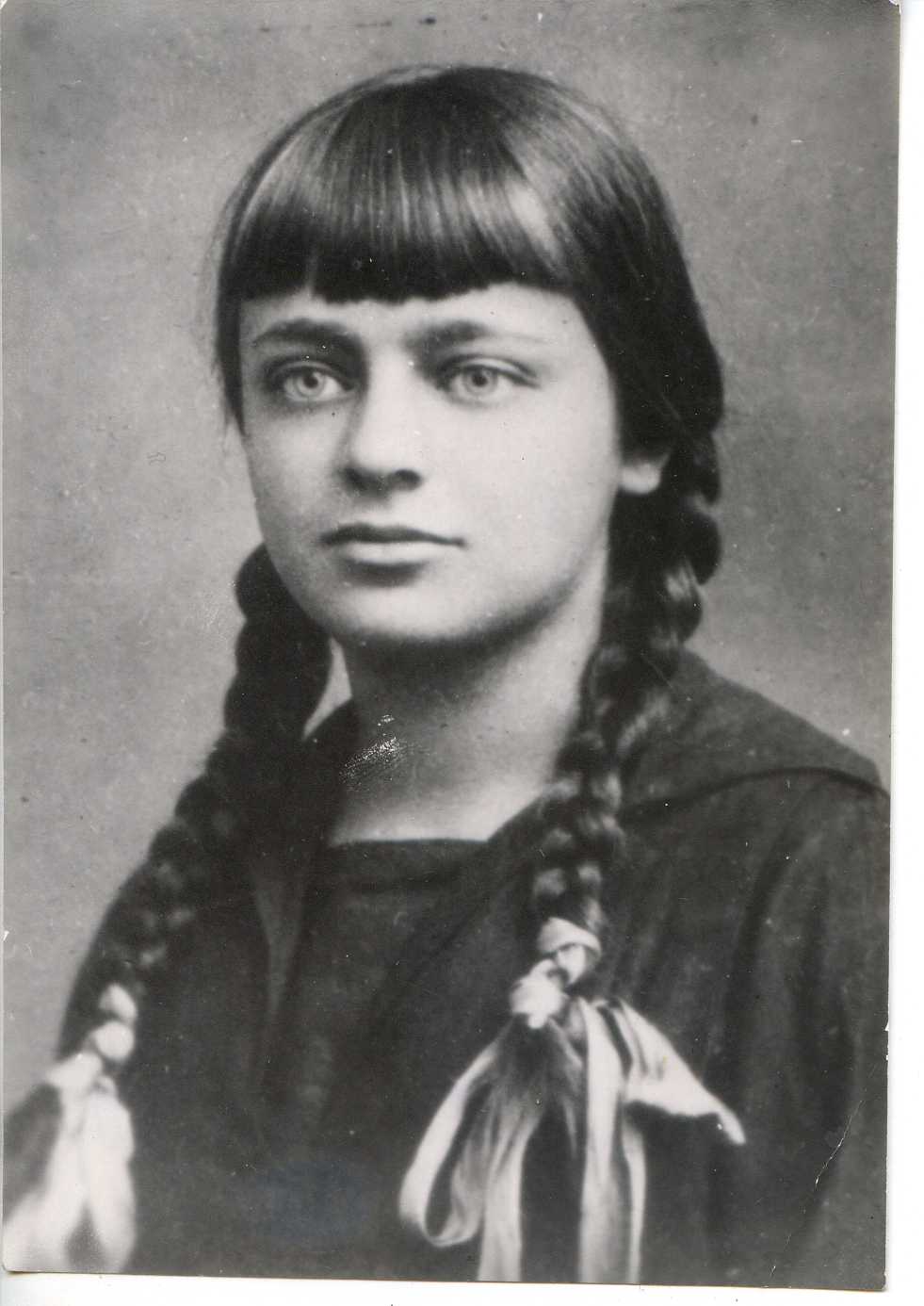

Marina Ivanovna Tsvetaeva ( rus, Марина Ивановна Цветаева, p=mɐˈrʲinə ɪˈvanəvnə tsvʲɪˈta(j)ɪvə, links=yes; 31 August 1941) was a Russian poet. Her work is some of the most well-known in twentieth-century Russian literature."Tsvetaeva, Marina Ivanovna" ''Who's Who in the Twentieth Century''. Oxford University Press, 1999. She lived through and wrote about the

She began spending time at Voloshin's home in the

She began spending time at Voloshin's home in the

In May 1922, Tsvetaeva and Ariadna left

In May 1922, Tsvetaeva and Ariadna left

In 1939, she and her son returned to Moscow, unaware of the reception she would receive. In

In 1939, she and her son returned to Moscow, unaware of the reception she would receive. In

Poetry Foundation

profile

Poetry Academy

profile

"Marina Tsvetaeva, ''Poet of the extreme''"

by Belinda Cooke from ''South'' magazine #31, April 2005. Republished online in the Poetry Library's Poetry Magazines site.

Marina Tsvetaeva biography

at

Heritage of Marina Tsvetayeva

a resource in English wit

a more extensive version in Russian

(in English). {{DEFAULTSORT:Tsvetaeva, Marina 1892 births 1941 suicides 1941 deaths 20th-century Russian women writers Soviet emigrants to Germany German emigrants to Czechoslovakia Diarists from the Russian Empire Women poets from the Russian Empire Suicides by hanging in the Soviet Union University of Paris alumni Russian women diarists Writers from Moscow Russian LGBTQ poets 20th-century Russian poets 20th-century Russian diarists Soviet diarists 20th-century Russian LGBTQ people Soviet women poets Russian women poets Russian satirists Russian satirical poets Russian women satirists

Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution, social change in Russian Empire, Russia, starting in 1917. This period saw Russia Dissolution of the Russian Empire, abolish its mona ...

of 1917 and the subsequent Moscow famine.

Marina attempted to save her daughter Irina from starvation by placing her in a state orphanage in 1919, where Irina died of hunger. Tsvetaeva left Russia in 1922 and lived with her family in increasing poverty in Paris, Berlin and Prague before returning to Moscow in 1939. Her husband Sergei Efron and their daughter Ariadna (Alya) were arrested on espionage charges in 1941, when her husband was executed.

Tsvetaeva died by suicide in 1941. As a lyrical poet, her passion and daring linguistic experimentation mark her as a historical chronicler of her times and the depths of the human condition.

Early years

Marina Tsvetaeva was born inMoscow

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

, the daughter of Ivan Vladimirovich Tsvetaev, a professor of Fine Art at the University of Moscow

Moscow State University (MSU), officially M. V. Lomonosov Moscow State University,. is a public research university in Moscow, Russia. The university includes 15 research institutes, 43 faculties, more than 300 departments, and six branches. Al ...

, who later founded the Alexander III Museum of Fine Arts (known from 1937 as the Pushkin Museum

The Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts (, abbreviated as , ''GMII'') is the largest museum of European art in Moscow. It is located in Volkhonka street, just opposite the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour. The International musical festival Sviatos ...

). Tsvetaeva's mother, , Ivan's second wife, was a concert pianist, highly literate, with German and Polish ancestry. Growing up in considerable material comfort,Feinstein (1993) pix Tsvetaeva would later come to identify herself with the Polish aristocracy.

Tsvetaeva's two half-siblings, Valeria and Andrei, were the children of Ivan's deceased first wife, Varvara Dmitrievna Ilovaiskaya, daughter of the historian Dmitry Ilovaisky. Tsvetaeva's only full sister, Anastasia

Anastasia (from ) is a feminine given name of Greek and Slavic origin, derived from the Greek word (), meaning "resurrection". It is a popular name in Eastern Europe.

Origin

The name Anastasia originated during the Early Christianity, early d ...

, was born in 1894. The children quarrelled frequently and occasionally violently. There was considerable tension between Tsvetaeva's mother and Varvara's children, and Tsvetaeva's father maintained close contact with Varvara's family. Tsvetaeva's father was kind, but deeply wrapped up in his studies and distant from his family. He was also still deeply in love with his first wife; he would never get over her. Likewise, Tsvetaeva's mother Maria had never recovered from a love affair she'd had before her marriage. Maria disapproved of Marina's poetic inclination; Maria wanted her daughter to become a pianist, holding the opinion that Marina's poetry was poor.

In 1902, Maria contracted tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

. A change in climate was recommended to help cure the disease, and so the family travelled abroad until shortly before her death in 1906, when Tsvetaeva was 14. They lived for a while by the sea at Nervi

Nervi is a former fishing village 12 miles (19 km) northwest of Portofino on the Riviera di Levante, now a seaside resort in Liguria, in northwest Italy. Once an independent ''comune'', it is now a ''quartiere'' of Genoa. Nervi is 4 miles ( ...

, near Genoa

Genoa ( ; ; ) is a city in and the capital of the Italian region of Liguria, and the sixth-largest city in Italy. As of 2025, 563,947 people live within the city's administrative limits. While its metropolitan city has 818,651 inhabitan ...

. There, away from the rigid constraints of a bourgeois Muscovite life, Tsvetaeva was able for the first time to run free, climb cliffs, and vent her imagination in childhood games. There were many Russian ''émigré'' revolutionaries residing at that time in Nervi, who may have had some influence on the young Tsvetaeva.

In June 1904, Tsvetaeva was sent to school in Lausanne

Lausanne ( , ; ; ) is the capital and largest List of towns in Switzerland, city of the Swiss French-speaking Cantons of Switzerland, canton of Vaud, in Switzerland. It is a hilly city situated on the shores of Lake Geneva, about halfway bet ...

. Changes in the Tsvetaev residence led to several changes in school, and during the course of her travels she acquired the Italian, French, and German languages. She gave up the strict musical studies that her mother had imposed and turned to poetry. She wrote "With a mother like her, I had only one choice: to become a poet".

In 1908, aged 16, Tsvetaeva studied literary history at the Sorbonne. During this time, a major revolutionary change was occurring within Russian poetry: the flowering of the Russian symbolist movement, and this movement was to colour most of her later work. It was not the theory which was to attract her, but the poetry and the gravity which writers such as Andrei Bely

Boris Nikolaevich Bugaev (, ; – 8 January 1934), better known by the pen name Andrei Bely or Biely, was a Russian novelist, Symbolist poet, theorist and literary critic. He was a committed anthroposophist and follower of Rudolf Steiner. Hi ...

and Alexander Blok

Alexander Alexandrovich Blok ( rus, Алекса́ндр Алекса́ндрович Бло́к, p=ɐlʲɪˈksandr ɐlʲɪˈksandrəvʲɪtɕ ˈblok, a=Ru-Alyeksandr Alyeksandrovich Blok.oga; 7 August 1921) was a Russian lyrical poet, writer, publ ...

were capable of generating. Her own first collection of poems, ''Vecherny Albom'' (''Evening Album''), self-published in 1910, promoted her considerable reputation as a poet. It was well received, although her early poetry was held to be insipid compared to her later work. It attracted the attention of the poet and critic Maximilian Voloshin, whom Tsvetaeva described after his death in ''A Living Word About a Living Man''. Voloshin came to see Tsvetaeva and soon became her friend and mentor.

Family and career

She began spending time at Voloshin's home in the

She began spending time at Voloshin's home in the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

resort of Koktebel ("Blue Height"), which was a well-known haven for writers, poets and artists. She became enamoured of the work of Alexander Blok and Anna Akhmatova

Anna Andreyevna Gorenko rus, А́нна Андре́евна Горе́нко, p=ˈanːə ɐnˈdrʲe(j)ɪvnə ɡɐˈrʲɛnkə, a=Anna Andreyevna Gorenko.ru.oga, links=yes; , . ( – 5 March 1966), better known by the pen name Anna Akhmatova,. ...

, although she never met Blok and did not meet Akhmatova until the 1940s. Describing the Koktebel community, the ''émigré'' Viktoria Schweitzer wrote: "Here inspiration was born." At Koktebel, Tsvetaeva met Sergei Yakovlevich Efron, a cadet in the Officers' Academy. She was 19, he 18: they fell in love and were married in 1912, the same year as her father's project, the Alexander III Museum of Fine Arts, was ceremonially opened, an event attended by Tsar Nicholas II

Nicholas II (Nikolai Alexandrovich Romanov; 186817 July 1918) or Nikolai II was the last reigning Emperor of Russia, King of Congress Poland, and Grand Duke of Finland from 1 November 1894 until his abdication on 15 March 1917. He married ...

. Tsvetaeva's love for Efron was intense; however, this did not preclude her from having affairs, including one with Osip Mandelstam

Osip Emilyevich Mandelstam (, ; – 27 December 1938) was a Russian and Soviet poet. He was one of the foremost members of the Acmeist school.

Osip Mandelstam was arrested during the repressions of the 1930s and sent into internal exile wi ...

, which she celebrated in a collection of poems called ''Mileposts''. At around the same time, she became involved in an affair with the poet Sophia Parnok, who was 7 years older than Tsvetaeva, an affair that caused her husband great grief. The two women fell deeply in love, and the relationship profoundly affected both women's writings. She deals with the ambiguous and tempestuous nature of this relationship in a cycle of poems which at times she called ''The Girlfriend'', and at other times ''The Mistake''. Tsvetaeva and her husband spent summers in the Crimea until the revolution, and had two daughters: Ariadna, or Alya (born 1912) and Irina (born 1917).

In 1914, Efron volunteered for the front and by 1917 he was an officer stationed in Moscow

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

with the 56th Reserve.

Tsvetaeva was a close witness of the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution, social change in Russian Empire, Russia, starting in 1917. This period saw Russia Dissolution of the Russian Empire, abolish its mona ...

, which she rejected. On trains, she came into contact with ordinary Russian people and was shocked by the mood of anger and violence. She wrote in her journal: "In the air of the compartment hung only three axe-like words: bourgeois, Junkers, leeches." After the 1917 Revolution, Efron joined the White Army

The White Army, also known as the White Guard, the White Guardsmen, or simply the Whites, was a common collective name for the armed formations of the White movement and Anti-Sovietism, anti-Bolshevik governments during the Russian Civil War. T ...

, and Marina returned to Moscow hoping to be reunited with her husband. She was trapped in Moscow for five years, where there was a terrible famine.

She wrote six plays in verse and narrative poems. Between 1917 and 1922 she wrote the epic verse cycle ''Lebedinyi stan'' (''The Encampment of the Swans'') about the civil war

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

, glorifying those who fought against the communists. The cycle of poems in the style of a diary or journal begins on the day of Tsar Nicholas II's abdication in March 1917, and ends late in 1920, when the anti-communist White Army was finally defeated. The 'swans' of the title refers to the volunteers in the White Army, in which her husband was fighting as an officer. In 1922, she published a long pro-imperial verse fairy tale, ''Tsar-devitsa'' ("Tsar-Maiden").

The Moscow famine was to exact a toll on Tsvetaeva. With no immediate family to turn to, she had no way to support herself or her daughters. In 1919, she placed both her daughters in a state orphanage, mistakenly believing that they would be better fed there. Alya became ill, and Tsvetaeva removed her, but Irina died there of starvation in 1920. The child's death caused Tsvetaeva great grief and regret. In one letter, she wrote, "God punished me."

During these years, Tsvetaeva maintained a close and intense friendship with the actress Sofia Evgenievna Holliday, for whom she wrote a number of plays. Many years later, she would write the novella "Povest o Sonechke" about her relationship with Holliday.

Exile

Berlin and Prague

In May 1922, Tsvetaeva and Ariadna left

In May 1922, Tsvetaeva and Ariadna left Soviet Russia

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (Russian SFSR or RSFSR), previously known as the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic and the Russian Soviet Republic, and unofficially as Soviet Russia,Declaration of Rights of the labo ...

and were reunited in Berlin with Efron, who she had thought had been killed by the Bolsheviks."Tsvetaeva, Marina Ivanovna" The Oxford Companion to English Literature. Edited by Dinah Birch. Oxford University Press Inc. There she published the collections ''Separation'', ''Poems to Blok'', and the poem ''The Tsar Maiden''. Much of her poetry was published in Moscow and Berlin, consolidating her reputation. In August 1922, the family moved to Prague

Prague ( ; ) is the capital and List of cities and towns in the Czech Republic, largest city of the Czech Republic and the historical capital of Bohemia. Prague, located on the Vltava River, has a population of about 1.4 million, while its P ...

. Living in unremitting poverty, unable to afford living accommodation in Prague itself, with Efron studying politics and sociology at the Charles University

Charles University (CUNI; , UK; ; ), or historically as the University of Prague (), is the largest university in the Czech Republic. It is one of the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, oldest universities in the world in conti ...

and living in hostels, Tsvetaeva and Ariadna found rooms in a village outside the city. She wrote: "We are devoured by coal, gas, the milkman, the baker... the only meat we eat is horsemeat." When offered an opportunity to earn money by reading her poetry, she had to beg a simple dress from a friend to replace the one she had been living in.Feinstein (1993) px

Tsvetaeva began a passionate affair with , a former military officer, a liaison which became widely known throughout émigré circles. Efron was devastated. Her break-up with Rodziewicz in 1923 was almost certainly the inspiration for her '' The Poem of the End'' and "The Poem of the Mountain". At about the same time, Tsvetaeva began correspondence with poet Rainer Maria Rilke

René Karl Wilhelm Johann Josef Maria Rilke (4 December 1875 – 29 December 1926), known as Rainer Maria Rilke, was an Austrian poet and novelist. Acclaimed as an Idiosyncrasy, idiosyncratic and expressive poet, he is widely recognized as ...

and novelist Boris Pasternak

Boris Leonidovich Pasternak (30 May 1960) was a Russian and Soviet poet, novelist, composer, and literary translator.

Composed in 1917, Pasternak's first book of poems, ''My Sister, Life'', was published in Berlin in 1922 and soon became an imp ...

. Tsvetaeva and Pasternak were not to meet for nearly twenty years, but maintained friendship until Tsvetaeva's return to Russia.

In summer 1924, Efron and Tsvetaeva left Prague for the suburbs, living for a while in Jíloviště, before moving on to Všenory, where Tsvetaeva completed "The Poem of the End", and was to conceive their son, Georgy, whom she was to later nickname 'Mur'. Tsvetaeva wanted to name him Boris (after Pasternak); Efron insisted on Georgy. He was to be a most difficult child but Tsvetaeva loved him obsessively. With Efron now rarely free from tuberculosis, their daughter Ariadna was relegated to the role of mother's helper and confidante, and consequently felt robbed of much of her childhood. In Berlin, before settling in Paris, Tsvetaeva wrote some of her greatest verse, including ''Remeslo'' ("Craft", 1923) and ''Posle Rossii'' ("After Russia", 1928). Reflecting a life in poverty and exiled, the work holds great nostalgia for Russia and its folk history, while experimenting with verse forms.

Paris

In 1925, the family settled inParis

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

, where they would live for the next 14 years. At about this time Tsvetaeva had a relapse of the tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

she had previously contracted in 1902. She received a small stipend from the Czechoslovak government, which gave financial support to artists and writers who had lived in Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

. In addition, she tried to make whatever she could from readings and sales of her work. She turned more and more to writing prose because she found it made more money than poetry. Tsvetaeva did not feel at all at home in Paris's predominantly ex-bourgeois circle of Russian émigré writers. Although she had written passionately pro- 'White' poems during the Revolution, her fellow émigrés thought that she was insufficiently anti-Soviet, and that her criticism of the Soviet régime was altogether too nebulous. She was particularly criticised for writing an admiring letter to the Soviet poet Vladimir Mayakovsky

Vladimir Vladimirovich Mayakovsky ( – 14 April 1930) was a Russian poet, playwright, artist, and actor. During his early, Russian Revolution, pre-Revolution period leading into 1917, Mayakovsky became renowned as a prominent figure of the Ru ...

. In the wake of this letter, the émigré paper '' Posledniye Novosti'', to which Tsvetaeva had been a frequent contributor, refused point-blank to publish any more of her work.Feinstein (1993) pxi She found solace in her correspondence with other writers, including Boris Pasternak

Boris Leonidovich Pasternak (30 May 1960) was a Russian and Soviet poet, novelist, composer, and literary translator.

Composed in 1917, Pasternak's first book of poems, ''My Sister, Life'', was published in Berlin in 1922 and soon became an imp ...

, Rainer Maria Rilke

René Karl Wilhelm Johann Josef Maria Rilke (4 December 1875 – 29 December 1926), known as Rainer Maria Rilke, was an Austrian poet and novelist. Acclaimed as an Idiosyncrasy, idiosyncratic and expressive poet, he is widely recognized as ...

, the Czech poet Anna Tesková, the critics D. S. Mirsky and Aleksandr Bakhrakh, and the Georgian émigré princess Salomea Andronikova, who became her main source of financial support. Her poetry and critical prose of the time, including her autobiographical prose works of 1934–7, is of lasting literary importance. But she felt "consumed by the daily round", resenting the domesticity that left her no time for solitude or writing. Moreover her émigré milieu regarded Tsvetaeva as a crude sort who ignored social graces. Describing her misery, she wrote to Tesková: "In Paris, with rare personal exceptions, everyone hates me, they write all sorts of nasty things, leave me out in all sorts of nasty ways, and so on". To Pasternak she complained "They don't like poetry and what am I apart from that, not poetry but that from which it is made. aman inhospitable hostess. A young woman in an old dress." She began to look back at even the Prague times with nostalgia and resent her exiled state more deeply.

Meanwhile, Tsvetaeva's husband Efron was developing Soviet sympathies and was homesick for Russia. Eventually, he began working for the NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (, ), abbreviated as NKVD (; ), was the interior ministry and secret police of the Soviet Union from 1934 to 1946. The agency was formed to succeed the Joint State Political Directorate (OGPU) se ...

, the forerunner of the KGB

The Committee for State Security (, ), abbreviated as KGB (, ; ) was the main security agency of the Soviet Union from 1954 to 1991. It was the direct successor of preceding Soviet secret police agencies including the Cheka, Joint State Polit ...

. Their daughter Alya shared his views, and increasingly turned against her mother. In 1937, she returned to the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

. Later that year, Efron too had to return to the USSR. The French police had implicated him in the murder of the former Soviet defector Ignace Reiss

Ignace Reiss (1899 – 4 September 1937) – also known as "Ignace Poretsky,"

"Ignatz Reiss,"

"Ludwig,"

"Ludwik", "Hans Eberhardt,"

"Steff Brandt,"

Nathan Poreckij,

and "Walter Scott (an officer of the U.S. military intelligence)" ...

in September 1937, on a country lane near Lausanne

Lausanne ( , ; ; ) is the capital and largest List of towns in Switzerland, city of the Swiss French-speaking Cantons of Switzerland, canton of Vaud, in Switzerland. It is a hilly city situated on the shores of Lake Geneva, about halfway bet ...

, Switzerland. After Efron's escape, the police interrogated Tsvetaeva, but she seemed confused by their questions and ended up reading them some French translations of her poetry. The police concluded that she was deranged and knew nothing of the murder. Later it was learned that Efron possibly had also taken part in the assassination of Trotsky's son in 1936. Tsvetaeva does not seem to have known that her husband was a spy, nor the extent to which he was compromised. However, she was held responsible for his actions and was ostracised in Paris because of the implication that he was involved with the NKVD. World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

had made Europe as unsafe and hostile as the USSR. In 1939, Tsvetaeva became lonely and alarmed by the rise of fascism, which she attacked in ''Stikhi k Chekhii'' ("Verses to Czechia" 1938–39).

Last years: Return to the Soviet Union

In 1939, she and her son returned to Moscow, unaware of the reception she would receive. In

In 1939, she and her son returned to Moscow, unaware of the reception she would receive. In Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

's USSR, anyone who had lived abroad was suspect, as was anyone who had been among the intelligentsia before the Revolution. Tsvetaeva's sister had been arrested before Tsvetaeva's return; although Anastasia survived the Stalin years, the sisters never saw each other again. Tsvetaeva found that all doors had closed to her. She got bits of work translating poetry, but otherwise the established Soviet writers refused to help her, and chose to ignore her plight; Nikolai Aseev, whom she had hoped would assist, shied away, fearful for his life and position.

Efron and Alya were arrested on espionage charges in 1941; Efron was sentenced to death. Alya's fiancé was actually an NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (, ), abbreviated as NKVD (; ), was the interior ministry and secret police of the Soviet Union from 1934 to 1946. The agency was formed to succeed the Joint State Political Directorate (OGPU) se ...

agent who had been assigned to spy on the family. Efron was shot in September 1941; Alya served over eight years in prison. Both were exonerated after Stalin's death. In 1941, Tsvetaeva and her son were evacuated to Yelabuga

Yelabuga (also spelled ''Elabuga''; ; ) is a town in the Republic of Tatarstan, Russia, located on the right bank of the Kama River and east from Kazan. Population:

The evolution of name

The name of the city of Yelabuga comes from the T ...

(Elabuga), while most families of the Union of Soviet Writers

The Union of Soviet Writers, USSR Union of Writers, or Soviet Union of Writers () was a creative union of professional writers in the Soviet Union. It was founded in 1934 on the initiative of the Central Committee of the Communist Party (1932) a ...

were evacuated to Chistopol

Chistopol (; ; , ''Çistay'') is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, town in Tatarstan, Russia, located on the left bank of the Kuybyshev Reservoir, on the Kama River. As of the Russian Census (2010), 2010 Census, its population was&nbs ...

. Tsvetaeva had no means of support in Yelabuga, and on 24 August 1941 she left for Chistopol desperately seeking a job. On 26 August, Marina Tsvetaeva and poet Valentin Parnakh applied to the Soviet of Literature Fund asking for a job at the LitFund's canteen. Parnakh was accepted as a doorman, while Tsvetaeva's application for a permission to live in Chistopol was turned down and she had to return to Yelabuga on 28 August.

On 31 August 1941, Tsvetaeva hanged herself in Yelabuga. She left a note for her son Georgy ("Mur"): "Forgive me, but to go on would be worse. I am gravely ill, this is not me anymore. I love you passionately. Do understand that I could not live anymore. Tell Papa and Alya, if you ever see them, that I loved them to the last moment and explain to them that I found myself in a trap."Feiler, Lily (1994). ''Marina Tsvetaeva: the double beat of Heaven and Hell''. Duke University Press. p264

According to the book ''The Death of a Poet: The Last Days of Marina Tsvetaeva'', the local NKVD department tried to force Tsvetaeva to start working as their informant, which left her no choice other than to die by suicide."The Death of a Poet: The Last Days of Marina Tsvetaeva", ''Modern Language Review'', July 2006 by Ute Stock

Tsvetaeva was buried in Yelabuga cemetery on 2 September 1941, but the exact location of her grave remains unknown.

Her son Georgy volunteered for the Eastern Front of World War II and died in battle in 1944. Her daughter Ariadna spent 16 years in Soviet prison camps and exile and was released in 1955. Ariadna wrote a memoir of her family; an English-language edition was published in 2009. She died in 1975.

In the town of Yelabuga, the Tsvetaeva house is now a museum; there is a monument to her. The apartment in Moscow where she lived from 1914 to 1922 is now a museum as well. Much of her poetry was republished in the Soviet Union after 1961, and her passionate, articulate and precise work, with its daring linguistic experimentation, brought her increasing recognition as a major Russian poet.

A minor planet

According to the International Astronomical Union (IAU), a minor planet is an astronomical object in direct orbit around the Sun that is exclusively classified as neither a planet nor a comet. Before 2006, the IAU officially used the term ''minor ...

, 3511 Tsvetaeva, discovered in 1982 by Soviet astronomer Lyudmila Karachkina

Lyudmila Georgievna Karachkina (, born 3 September 1948, Rostov-on-Don) is an astronomer and discoverer of minor planets.

In 1978 she began as a staff astronomer of the Institute for Theoretical Astronomy (ITA) at Leningrad. Her research at the ...

, is named after her.

In 1989, in Gdynia

Gdynia is a city in northern Poland and a seaport on the Baltic Sea coast. With an estimated population of 257,000, it is the List of cities in Poland, 12th-largest city in Poland and the second-largest in the Pomeranian Voivodeship after Gdańsk ...

, Poland, a special-purpose ship was built for the Russian Academy of Sciences

The Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS; ''Rossíyskaya akadémiya naúk'') consists of the national academy of Russia; a network of scientific research institutes from across the Russian Federation; and additional scientific and social units such ...

and named Marina Tsvetaeva in her honor. From 2007, the ship served as a tourist vessel to the polar regions for Aurora Expeditions

Aurora Expeditions is an Australian company that runs cruises, expeditions and tours.

History

The company was founded in 1991 by the Australian climber Greg Mortimer and Margaret Mortimer. It focuses on small groups of travelers. The company's ...

. In 2011, she was renamed and is currently operated by Oceanwide Expeditions as a tourist vessel in the polar regions.

Work

Tsvetaeva's poetry was admired by poets such as Valery Bryusov, Maximilian Voloshin,Osip Mandelstam

Osip Emilyevich Mandelstam (, ; – 27 December 1938) was a Russian and Soviet poet. He was one of the foremost members of the Acmeist school.

Osip Mandelstam was arrested during the repressions of the 1930s and sent into internal exile wi ...

, Boris Pasternak

Boris Leonidovich Pasternak (30 May 1960) was a Russian and Soviet poet, novelist, composer, and literary translator.

Composed in 1917, Pasternak's first book of poems, ''My Sister, Life'', was published in Berlin in 1922 and soon became an imp ...

, Rainer Maria Rilke

René Karl Wilhelm Johann Josef Maria Rilke (4 December 1875 – 29 December 1926), known as Rainer Maria Rilke, was an Austrian poet and novelist. Acclaimed as an Idiosyncrasy, idiosyncratic and expressive poet, he is widely recognized as ...

, and Anna Akhmatova

Anna Andreyevna Gorenko rus, А́нна Андре́евна Горе́нко, p=ˈanːə ɐnˈdrʲe(j)ɪvnə ɡɐˈrʲɛnkə, a=Anna Andreyevna Gorenko.ru.oga, links=yes; , . ( – 5 March 1966), better known by the pen name Anna Akhmatova,. ...

. Later, that recognition was also expressed by the poet Joseph Brodsky

Iosif Aleksandrovich Brodsky (; ; 24 May 1940 – 28 January 1996) was a Russian and American poet and essayist. Born in Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg) in the Soviet Union, Brodsky ran afoul of Soviet authorities and was expelled ("strongly ...

, pre-eminent among Tsvetaeva's champions. Tsvetaeva was primarily a lyrical poet, and her lyrical voice remains clearly audible in her narrative poetry. Brodsky said of her work: "Represented on a graph, Tsvetaeva's work would exhibit a curve – or rather, a straight line – rising at almost a right angle because of her constant effort to raise the pitch a note higher, an idea higher (or, more precisely, an octave and a faith higher.) She always carried everything she has to say to its conceivable and expressible end. In both her poetry and her prose, nothing remains hanging or leaves a feeling of ambivalence. Tsvetaeva is the unique case in which the paramount spiritual experience of an epoch (for us, the sense of ambivalence, of contradictoriness in the nature of human existence) served not as the object of expression but as its means, by which it was transformed into the material of art." Critic Annie Finch

Annie Finch (born October 31, 1956) is an American poet, critic, editor, translator, playwright, and performer and the editor of the first major anthology of literature about abortion. Her poetry is known for its often incantatory use of rhythm, ...

describes the engaging, heart-felt nature of the work. "Tsvetaeva is such a warm poet, so unbridled in her passion, so completely vulnerable in her love poetry, whether to her female lover Sofie Parnak, to Boris Pasternak. ..Tsvetaeva throws her poetic brilliance on the altar of her heart’s experience with the faith of a true romantic, a priestess of lived emotion. And she stayed true to that faith to the tragic end of her life.

Tsvetaeva's lyric poems fill ten collections; the uncollected lyrics would add at least another volume. Her first two collections indicate their subject matter in their titles: ''Evening Album'' (Vecherniy albom, 1910) and ''The Magic Lantern'' (Volshebnyi fonar, 1912). The poems are vignettes of a tranquil childhood and youth in a professorial, middle-class home in Moscow, and display considerable grasp of the formal elements of style. The full range of Tsvetaeva's talent developed quickly, and was undoubtedly influenced by the contacts she had made at Koktebel, and was made evident in two new collections: ''Mileposts'' (Versty, 1921) and ''Mileposts: Book One'' (Versty, Vypusk I, 1922).

Three elements of Tsvetaeva's mature style emerge in the ''Mileposts'' collections. First, Tsvetaeva dates her poems and publishes them chronologically. The poems in ''Mileposts: Book One'', for example, were written in 1916 and resolve themselves as a versified journal. Secondly, there are cycles of poems which fall into a regular chronological sequence among the single poems, evidence that certain themes demanded further expression and development. One cycle announces the theme of ''Mileposts: Book One'' as a whole: the "Poems of Moscow." Two other cycles are dedicated to poets, the "Poems to Akhmatova" and the "Poems to Blok", which again reappear in a separate volume, Poems to Blok (''Stikhi k Bloku'', 1922). Thirdly, the ''Mileposts'' collections demonstrate the dramatic quality of Tsvetaeva's work, and her ability to assume the guise of multiple ''dramatis personae'' within them.

The collection ''Separation'' (Razluka, 1922) was to contain Tsvetaeva's first long verse narrative, "On a Red Steed" ("Na krasnom kone"). The poem is a prologue to three more verse-narratives written between 1920 and 1922. All four narrative poems draw on folkloric plots. Tsvetaeva acknowledges her sources in the titles of the very long works, '' The Maiden Tsar: A Fairy-tale Poem'' (''Tsar-devitsa: Poema-skazka'', 1922) and "The Swain", subtitled "A Fairytale" ("Molodets: skazka", 1924). The fourth folklore-style poem is "Byways" ("Pereulochki", published in 1923 in the collection ''Remeslo''), and it is the first poem which may be deemed incomprehensible in that it is fundamentally a soundscape of language. The collection ''Psyche'' (''Psikheya'', 1923) contains one of Tsvetaeva's best-known cycles "Insomnia" (Bessonnitsa) and the poem The Swans' Encampment (Lebedinyi stan, Stikhi 1917–1921, published in 1957) which celebrates the White Army

The White Army, also known as the White Guard, the White Guardsmen, or simply the Whites, was a common collective name for the armed formations of the White movement and Anti-Sovietism, anti-Bolshevik governments during the Russian Civil War. T ...

.

Emigrant

Subsequently, as an émigré, Tsvetaeva's last two collections of lyrics were published by émigré presses, ''Craft'' (''Remeslo'', 1923) in Berlin and ''After Russia'' (''Posle Rossii'', 1928) in Paris. There then followed the twenty-three lyrical "Berlin" poems, the pantheistic "Trees" ("Derev'ya"), "Wires" ("Provoda") and "Pairs" ("Dvoe"), and the tragic "Poets" ("Poety"). "After Russia" contains the poem "In Praise of the Rich", in which Tsvetaeva's oppositional tone is merged with her proclivity for ruthless satire.

Satire

Satire is a secondary element after lyricism in Tsvetaeva's poetry. Several satirical poems, moreover, are among Tsvetaeva's best-known works: "The Train of Life" ("Poezd zhizni") and "The Floorcleaners' Song" ("Poloterskaya"), both included in After Russia, and The Ratcatcher (Krysolov, 1925–1926), a long, folkloric narrative. The target of Tsvetaeva's satire is everything petty and petty bourgeois. Unleashed against such dull creature comforts is the vengeful, unearthly energy of workers both manual and creative. In her notebook, Tsvetaeva writes of "The Floorcleaners' Song": "Overall movement: the floorcleaners ferret out a house's hidden things, they scrub a fire into the door... What do they flush out? Coziness, warmth, tidiness, order... Smells: incense, piety. Bygones. Yesterday... The growing force of their threat is far stronger than the climax." ''The Ratcatcher'' poem, which Tsvetaeva describes as a ''lyrical satire'', is loosely based on the legend of thePied Piper of Hamelin

The Pied Piper of Hamelin (, also known as the Pan Piper or the Rat-Catcher of Hamelin) is the title character of a legend from the town of Hamelin (Hameln), Lower Saxony, Germany.

The legend dates back to the Middle Ages. The earliest refer ...

. The Ratcatcher, which is also known as The Pied Piper, is considered by some to be the finest of Tsvetaeva's work. It was also partially an act of ''homage'' to Heinrich Heine

Christian Johann Heinrich Heine (; ; born Harry Heine; 13 December 1797 – 17 February 1856) was an outstanding poet, writer, and literary criticism, literary critic of 19th-century German Romanticism. He is best known outside Germany for his ...

's poem ''Die Wanderratten''. The Ratcatcher appeared initially, in serial format, in the émigré journal ' in 1925–1926 whilst still being written. It was not to appear in the Soviet Union until after the death of Joseph Stalin

Death is the end of life; the irreversible cessation of all biological functions that sustain a living organism. Death eventually and inevitably occurs in all organisms. The remains of a former organism normally begin to decompose shor ...

in 1956. Its hero is the Pied Piper of Hamelin who saves a town from hordes of rats and then leads the town's children away too, in retribution for the citizens' ingratitude. As in the other folkloric narratives, The Ratcatcher's story line emerges indirectly through numerous speaking voices which shift from invective, to extended lyrical flights, to pathos.

Tsvetaeva's last ten years of exile, from 1928 when "After Russia" appeared until her return in 1939 to the Soviet Union, were principally a "prose decade", though this would almost certainly be by dint of economic necessity rather than one of choice.

Translators

Translators of Tsvetaeva's work into English include Elaine Feinstein and David McDuff. Nina Kossman translated many of Tsvetaeva's long (narrative) poems, as well as her lyrical poems; they are collected in three books, ''Poem of the End'' (bilingual edition published by Ardis in 1998, by Overlook in 2004, and by Shearsman Books in 2021), ''In the Inmost Hour of the Soul'' (Humana Press, 1989), and ''Other Shepherds'' (Poets & Traitors Press, 2020). Robin Kemball translated the cycle ''The Demesne of the Swans'', published as a separate (bilingual) book by Ardis in 1980. J. Marin King translated a great deal of Tsvetaeva's prose into English, compiled in a book called ''A Captive Spirit''. Tsvetaeva scholar Angela Livingstone has translated a number of Tsvetaeva's essays on art and writing, compiled in a book called ''Art in the Light of Conscience''. Livingstone's translation of Tsvetaeva's "The Ratcatcher" was published as a separate book. Mary Jane White has translated the early cycle "Miles" in a book called "Starry Sky to Starry Sky", as well as Tsvetaeva's elegy for Rilke, "New Year's", (Adastra Press 16 Reservation Road, Easthampton, MA 01027 USA) and "Poem of the End" (The Hudson Review, Winter 2009; and in the anthology Poets Translate Poets, Syracuse U. Press 2013) and "Poem of the Hill", (New England Review, Summer 2008) and Tsvetaeva's 1914–1915 cycle of love poems to Sophia Parnok. In 2002,Yale University Press

Yale University Press is the university press of Yale University. It was founded in 1908 by George Parmly Day and Clarence Day, grandsons of Benjamin Day, and became a department of Yale University in 1961, but it remains financially and ope ...

published Jamey Gambrell's translation of post-revolutionary prose, entitled ''Earthly Signs: Moscow Diaries, 1917–1922'', with notes on poetic and linguistic aspects of Tsvetaeva's prose, and endnotes for the text itself.

Cultural influence

* 2017: ''Zerkalo'' ("Mirror"), American magazine in MN for the Russian-speaking readers. It was a special publication to the 125th Anniversary of the Russian poet Marina Tsvetaeva, where the article "Marina Tsvetaeva in America" was written by Dr. Uli Zislin, the founder and director of the Washington Museum of Russian Poetry and Music, Sep/Oct 2017.Music and songs

In 1973, Soviet composerDmitri Shostakovich

Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich, group=n (9 August 1975) was a Soviet-era Russian composer and pianist who became internationally known after the premiere of his First Symphony in 1926 and thereafter was regarded as a major composer.

Shostak ...

set six of Tsvetaeva's poems in his '' Six Poems by Marina Tsvetayeva''. Later the Russian-Tatar composer Sofia Gubaidulina

Sofia Asgatovna Gubaidulina (24 October 1931 – 13 March 2025) was a Soviet and Russian composer of Modernism (music), modernist Holy minimalism, sacred music. She was highly prolific, producing numerous Chamber music, chamber, Orchestra, orch ...

wrote an ''Hommage à Marina Tsvetayeva'' featuring her poems. Her poem "Mne Nravitsya..." ("I like that..."), was performed by Alla Pugacheva

Alla Borisovna Pugacheva (, ; born 15 April 1949) is a Russian singer and songwriter. Her career began in 1965 and continues to this day, although she retired from performing in 2010 after the international concert tour "Dreams of Love". For her ...

in the film ''The Irony of Fate

''The Irony of Fate, or Enjoy Your Bath!'',; usually shortened to ''The Irony of Fate'', is a 1976 Soviet romantic comedy television film directed by Eldar Ryazanov and starring Andrey Myagkov, Barbara Brylska, Yury Yakovlev and Lyubov Dobrzh ...

''. In 2003, the opera ''Marina: A Captive Spirit'', based on Tsvetaeva's life and work, premiered from American Opera Projects in New York with music by Deborah Drattell and libretto by poet Annie Finch

Annie Finch (born October 31, 1956) is an American poet, critic, editor, translator, playwright, and performer and the editor of the first major anthology of literature about abortion. Her poetry is known for its often incantatory use of rhythm, ...

. The production was directed by Anne Bogart

Anne Bogart (born September 25, 1951) is an American theatre and opera director. She is currently one of the artistic directors of SITI Company, which she founded with Japanese director Tadashi Suzuki in 1992. She is a professor at Columbia Uni ...

and the part of Tsvetaeva was sung by Lauren Flanigan

Lauren Flanigan (born May 18, 1958) is an American operatic soprano who has had an active international career since the 1980s. She enjoyed a particularly fruitful partnership with the New York City Opera, appearing with the company almost every ye ...

. The poetry by Tsvetaeva was set to music and frequently performed as songs by Elena Frolova, Larisa Novoseltseva, Zlata Razdolina and other Russian bards. In 2019, American composer Mark Abel wrote ''Four Poems of Marina Tsvetaeva'', the first classical song cycle of the poet in an English translation. Soprano Hila Plitmann

Hila Plitmann (; born August 9, 1973) is an Israeli-American two-time Grammy Award-winning operatic soprano, songwriter, and actress specializing in the performance of new works.

Career

Education

*Juilliard School of Music: Bachelor of Mus ...

recorded the piece for Abel’s album ''The Cave of Wondrous Voice''.

Tribute

On 8 October 2015,Google Doodle

Google Doodle is a special, temporary alteration of the logo on Google's homepages intended to commemorate holidays, events, achievements, and historical figures. The first Google Doodle honored the 1998 edition of the long-running annual Bu ...

commemorated her 123rd birthday.

Translations into English

* ''Selected Poems'', trans. Elaine Feinstein. (Oxford University Press, 1971; 2nd ed., 1981; 3rd ed., 1986; 4th ed., 1993; 5th ed., 1999; 6th ed. 2009 as ''Bride of Ice: New Selected Poems'') * ''The Demesne of the Swans'', trans. Robin Kemball (bilingual edition, Ardis, 1980) ISBN 978-0882334936 *''Marina Tsvetayeva: Selected Poems'', trans. David McDuff. (Bloodaxe Books, 1987) *"Starry Sky to Starry Sky (Miles)", trans. Mary Jane White. ( Holy Cow! Press, 1988), (paper) and (cloth) *''In the Inmost Hour of the Soul: Poems by Marina Tsvetayeva '', trans. Nina Kossman (Humana Press, 1989) *''Black Earth'', trans. Elaine Feinstein (The Delos Press and The Menard Press, 1992) ISBN I-874320-00-4 and ISBN I-874320-05-5 (signed ed.) *"After Russia", trans. Michael Nayden (Ardis, 1992). * ''A Captive Spirit: Selected Prose'', trans. J. Marin King (Vintage Books, 1994) *''Poem of the End: Selected Narrative and Lyrical Poems '', trans. Nina Kossman (Ardis / Overlook, 1998, 2004) ; Poem of the End: Six Narrative Poems, trans. Nina Kossman (Shearsman Books, 2021) ISBN 978-1-84861-778-0) *''The Ratcatcher: A Lyrical Satire'', trans. Angela Livingstone (Northwestern University, 2000) *''Letters: Summer 1926'' (Boris Pasternak, Marina Tsvetayeva, Rainer Maria Rilke) (New York Review Books, 2001) * ''Earthly Signs: Moscow Diaries, 1917–1922'', ed. & trans. Jamey Gambrell (Yale University Press, 2002) *''Phaedra: a drama in verse; with New Year's Letter and other long poems'', trans. Angela Livingstone (Angel Classics, 2012) *"To You – in 10 Decades", trans. by Alexander Givental and Elysee Wilson-Egolf (Sumizdat 2012) *''Moscow in the Plague Year'', translated by Christopher Whyte (180 poems written between November 1918 and May 1920) (Archipelago Press, New York, 2014), 268pp, *''Milestones (1922),'' translated by Christopher Whyte (Bristol, Shearsman Books, 2015), 122p, *''After Russia: The First Notebook,'' translated by Christopher Whyte (Bristol, Shearsman Books, 2017), 141 pp, *''After Russia: The Second Notebook'', translated by Christopher Whyte (Bristol, Shearsman Books, 2018) 121 pp, *"Poem of the End" in "From A Terrace in Prague, A Prague Poetry Anthology", trans. Mary Jane White, ed. Stephan Delbos (Univerzita Karlova v Praze, 2011) *''Youthful Verses'', translated by Christopher Whyte (Bristol, Shearsman Books, 2021), 114 pp, ISBN 9781848617315 *''Head on a Gleaming Plate: Poems 1917-1918'', translated by Christopher Whyte (Bristol, Shearsman Books, 2022), 120 pp, ISBN 9781848618435 *''Poems'', trans. Alyssa Gillespie (Columbia University Press, forthcoming) *''Three by Tsvetaeva'', trans. Andrew Davis (New York Review Books, 2024)References

Further reading

* Schweitzer, Viktoria ''Tsvetaeva'' (1993) * Mandelstam, Nadezhda ''Hope Against Hope'' * Mandelstam, Nadezhda ''Hope Abandoned'' * Pasternak, Boris ''An Essay in Autobiography''External links

Poetry Foundation

profile

Poetry Academy

profile

"Marina Tsvetaeva, ''Poet of the extreme''"

by Belinda Cooke from ''South'' magazine #31, April 2005. Republished online in the Poetry Library's Poetry Magazines site.

Marina Tsvetaeva biography

at

Carcanet Press

Carcanet Press is a publisher, primarily of poetry, based in the United Kingdom. Originally a student magazine devised by undergraduates collaborating between Oxford and Cambridge, it was refounded in 1969 by Michael Schmidt.

In 2000 it was nam ...

, English language publisher of Tsvetaeva's ''Bride of Ice'' and ''Marina Tsvetaeva: Selected Poems'', translated by Elaine Feinstein.

Heritage of Marina Tsvetayeva

a resource in English wit

a more extensive version in Russian

(in English). {{DEFAULTSORT:Tsvetaeva, Marina 1892 births 1941 suicides 1941 deaths 20th-century Russian women writers Soviet emigrants to Germany German emigrants to Czechoslovakia Diarists from the Russian Empire Women poets from the Russian Empire Suicides by hanging in the Soviet Union University of Paris alumni Russian women diarists Writers from Moscow Russian LGBTQ poets 20th-century Russian poets 20th-century Russian diarists Soviet diarists 20th-century Russian LGBTQ people Soviet women poets Russian women poets Russian satirists Russian satirical poets Russian women satirists