Malayan Peoples' Anti-Japanese Army on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Malayan Peoples' Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA) was a

The British Military Administration (BMA) formally took over control of Malaya on 12 September 1945. The British army saw the MPAJA guerrillas as a hindrance to their tasks of establishing law and order in the country and was anxious to demobilise the MPAJA as soon as possible. Fearing that the MPAJA might challenge British authority, the British army ordered all MPAJA units to concentrate in certain centres and to come under its overall command. Force 136 officers would continue to be liaison officers with the MPAJA. The BMA also declared the MPAJA no longer operational after 12 September, although they were allowed to remain armed until negotiations were finalised for their disarmament. Additionally, the MPAJA was not allowed to conduct further extrajudicial punishment on collaborators without permission from the British authorities.

The British Military Administration (BMA) formally took over control of Malaya on 12 September 1945. The British army saw the MPAJA guerrillas as a hindrance to their tasks of establishing law and order in the country and was anxious to demobilise the MPAJA as soon as possible. Fearing that the MPAJA might challenge British authority, the British army ordered all MPAJA units to concentrate in certain centres and to come under its overall command. Force 136 officers would continue to be liaison officers with the MPAJA. The BMA also declared the MPAJA no longer operational after 12 September, although they were allowed to remain armed until negotiations were finalised for their disarmament. Additionally, the MPAJA was not allowed to conduct further extrajudicial punishment on collaborators without permission from the British authorities.

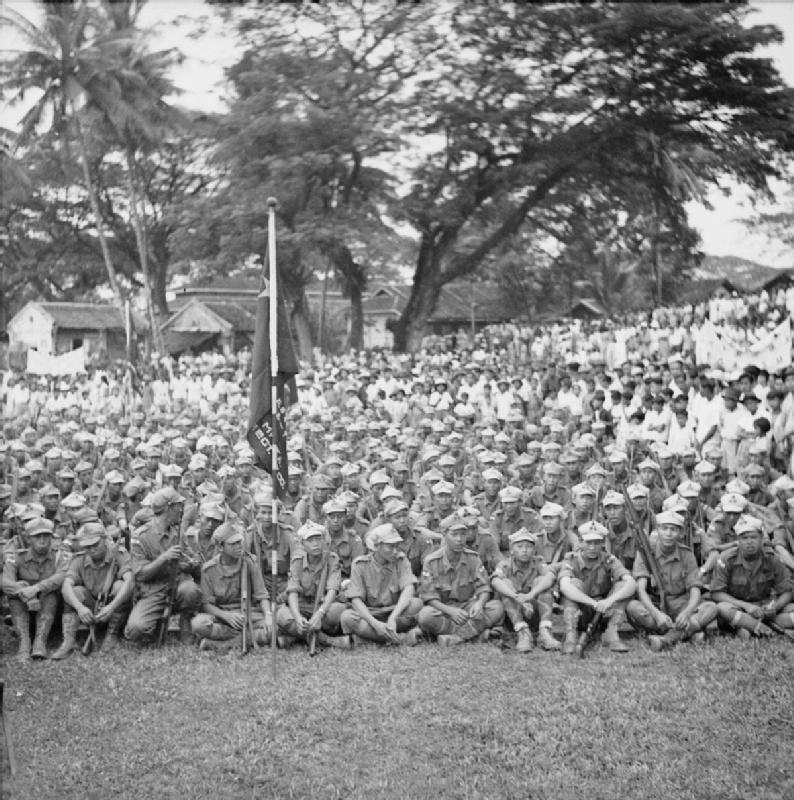

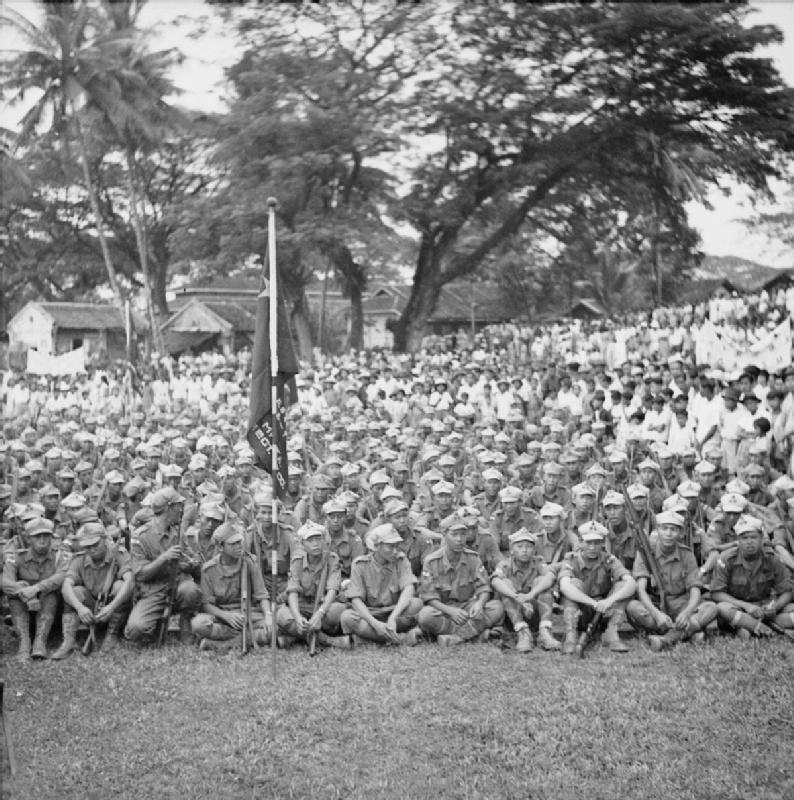

The MPAJA was formally dissolved on 1 December 1945. A gratuity sum of $350 was paid to each disbanded member of the MPAJA, with the option for him to enter civilian employment or to join the police, volunteer forces or the Malay Regiment. 5,497 weapons were handed in by 6,800 guerrillas in demobilisation ceremonial parades held at MPAJA headquarters around the country. However, it was believed that the MPAJA did not proceed to disarm with full compliance. British authorities discovered that most of the surrendered arms were old-type weapons and suspected that the MPAJA hid the newer weapons in the jungles. One particular incident reinforced this suspicion when the British army stumbled upon an armed Chinese settlement that had its own governing body, military drilling facilities and flag while conducting a raid on one of the old MPAJA encampments. Members of this settlement opened fire at the British soldiers on sight, and the skirmish ended with one Chinese man dead.

The MPAJA was formally dissolved on 1 December 1945. A gratuity sum of $350 was paid to each disbanded member of the MPAJA, with the option for him to enter civilian employment or to join the police, volunteer forces or the Malay Regiment. 5,497 weapons were handed in by 6,800 guerrillas in demobilisation ceremonial parades held at MPAJA headquarters around the country. However, it was believed that the MPAJA did not proceed to disarm with full compliance. British authorities discovered that most of the surrendered arms were old-type weapons and suspected that the MPAJA hid the newer weapons in the jungles. One particular incident reinforced this suspicion when the British army stumbled upon an armed Chinese settlement that had its own governing body, military drilling facilities and flag while conducting a raid on one of the old MPAJA encampments. Members of this settlement opened fire at the British soldiers on sight, and the skirmish ended with one Chinese man dead.

communist

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, di ...

guerrilla army that resisted the Japanese occupation of Malaya from 1941 to 1945 in World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. Composed mainly of ethnic Chinese guerrilla fighters, the MPAJA was the largest anti-Japanese resistance group in Malaya. Founded during the Japanese invasion of Malaya, the MPAJA was conceived as a part of a combined effort by the Malayan Communist Party (MCP) and the British colonial government, alongside various smaller groups to resist the Japanese occupation. Although the MPAJA and the MCP were officially different organisations, many saw the MPAJA as a ''de facto'' armed wing of the MCP due to its leadership being staffed by mostly ethnic Chinese communists.Lee, T. H. (1996). The Basic Aims or Objectives of the Malayan Communist Movement. In T. H. Lee, ''The Open United Front: The Communist Struggle in Singapore'' (pp. 2–29). Singapore : South Seas Society. Many of the ex-guerrillas of the MPAJA would later form the Malayan National Liberation Army

The Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA) was a Communist guerrilla army that fought for Malayan independence from the British Empire during the Malayan Emergency (1948–1960) and later fought against the Malaysian government in the Commun ...

(MNLA) and resist a return to pre-war the normality of British rule of Malaya during the Malayan Emergency

The Malayan Emergency, also known as the Anti–British National Liberation War, was a guerrilla warfare, guerrilla war fought in Federation of Malaya, Malaya between communist pro-independence fighters of the Malayan National Liberation Arm ...

(1948–1960).

Background

Rise of anti-Japanese sentiments and the Malayan Communist Party

Anti-Japanese feelings among the Chinese community in Malaya first began in 1931, with the Japanese invasion and annexation of Manchuria. This escalation in Japanese imperial expansion occurred alongside the Great Depression, during which thousands of Malayan workers were left unemployed. The country's large workforce of Chinese and Indian immigrants that had previously fueled the rubber industry's regional boom suddenly found themselves out of work. The Chinese Communist Party leveraged these economic conditions to help spread their revolutionary ideology in the country. Driven by political, racial, and class solidarity, young Chinese immigrants joined the growing Malayan Communist Party (M.C.P.) in greater numbers than most other demographic groups . Throughout the 1930s, the policies of the M.C.P. and other Malayan revolutionary organizations grew increasingly anti-Japanese, fueled by further escalations in Japanese imperial expansion. Anti-Japanese sentiments among the Malayan populace reached new heights when Japan declared war on China in 1937, which increased the membership and political influence of the M.C.P.Forming a united front

While being anti-Japanese, the MCP was also involved in its local struggle against British Imperialism in Malaya. However, political developments in 1941 prompted the MCP to withhold its hostilities against the British and seek co-operation instead. First of all, war between theSoviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

and Germany had made the Soviets join the Allies against the Axis powers

The Axis powers, originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis and also Rome–Berlin–Tokyo Axis, was the military coalition which initiated World War II and fought against the Allies of World War II, Allies. Its principal members were Nazi Ge ...

which included Japan. Additionally, the Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT) is a major political party in the Republic of China (Taiwan). It was the one party state, sole ruling party of the country Republic of China (1912-1949), during its rule from 1927 to 1949 in Mainland China until Retreat ...

(KMT) and the Chinese Communist Party

The Communist Party of China (CPC), also translated into English as Chinese Communist Party (CCP), is the founding and One-party state, sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Founded in 1921, the CCP emerged victorious in the ...

(CCP) had formed a united front against the Japanese invasion in mainland China. As a communist organisation closely associated with the CCP and the Soviet Union, the MCP had to alter its stance towards the British as the Soviets and CCP became wartime allies with them. Secondly, the MCP viewed the imminent Japanese invasion of Malaya as a greater threat than the British.Cheah, B. (1983). ''Red Star Over Malaya.''

Singapore: Singapore University Press. Therefore, an offer of mutual co-operation against a potential Japanese aggression was first made in July 1941 to the British. However, the offer was rejected as British officials felt that recognising the MCP would give them an unnecessary boost in legitimising its nationalist

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation,Anthony D. Smith, Smith, A ...

agendaBan, K. C., & Yap, H. (2002). ''Rehearsal for''

War: The Underground War against the Japanese.'' Singapore: Horizon Books.''

Nevertheless, the eventual Japanese invasion of Malaya on 8 December 1941 presented the MCP another opportunity to seek co-operation with the British. After the Japanese forces made rapid gains against the British defences in Malaya, the MCP came out publicly to support the British war effort, encouraging Malayan Chinese to pledge their assistance to the British. As the British faced further military setbacks with the sinking of its battleships ''Prince of Wales'' and ''Repulse'', the British finally accepted the MCP's offer of assistance on 18 December 1941. A secret meeting was held in Singapore between British officers and two MCP representatives, one of whom was Lai Teck, the MCP's secretary general.

The agreement between the MCP and the British was that the MCP would recruit, and the British would provide training to resistance groups. Also, the trained resistance fighters would be used as the British Military Command saw fit. The recruits were to undergo training in sabotage and guerrilla warfare at the 101 Special Training School (STS) in Singapore, operated by the Malayan wing of the London-based Special Operations Executive (SOE). On 19 December 1941, the MCP also brought together various anti-Japanese groups, organisations such as the KMT and the Chinese Chamber of Commerce, under a broad front called the "Overseas Chinese Anti-Japanese Mobilisation Federation" (OCAJMF) with Tan Kah Kee as the leader of its "Mobilisation Council".Cooper, B. (1998). The Malayan Communist Party (MCP)

and the Malayan People's Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA). In B. Cooper, ''Decade of''

Change: Malaya and the Straits Settlements 1936–1945'' (pp. 426–464).''

Singapore: Graham Brash. The OCAJMF became a platform to recruit Chinese volunteer soldiers to form an independent force, which would be later known as Dalforce. The MCP contributed the most soldiers to Dalforce, although it had also received volunteers from the KMT and other independent organisations. Dalforce was disbanded upon Singapore's surrender to the Japanese on 14 February 1942.

MPAJA during the Japanese occupation (1942–1945)

Birth of the Malayan People's Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA)

The 101 Special Training School may be regarded as the birthplace of the MPAJA. A total of 165 party members were selected by the MCP to participate in the training, which began on 21 December 1941. The training was rushed, with individual courses lasting only ten days and a total of 7 classes. Receiving only basic training and poorly-equipped, these graduated recruits would be sent across the peninsula to operate as independent squads. The first batch of 15 recruits was sent nearKuala Lumpur

Kuala Lumpur (KL), officially the Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur, is the capital city and a Federal Territories of Malaysia, federal territory of Malaysia. It is the largest city in the country, covering an area of with a census population ...

, where they had some success in disrupting Japanese communication lines in northern Selangor

Selangor ( ; ), also known by the Arabic language, Arabic honorific Darul Ehsan, or "Abode of Sincerity", is one of the 13 states of Malaysia. It is on the west coast of Peninsular Malaysia and is bordered by Perak to the north, Pahang to the e ...

. However, many were killed within the first few months of fighting, but the surviving ones went on to form the core leadership of the MPAJA and train new recruits. In March 1942, after liaising with the Central Committee of the MCP, these graduates of the 101 STS would officially form the First Independent Force of the MPAJA.

Going underground

The MCP decided to go underground as British defences collapsed quickly in the face of the Japanese army's onslaught. A policy of armed resistance throughout the occupation was declared by all top-ranking MCP members at a final meeting in Singapore in February 1942. This decision proved beneficial to the MCP's political and military advancement, as they were the only political organisation prepared to commit itself to a policy of active anti-Japanese insurgency. After the fall of Singapore resistance forces were cut off from external assistance. The lack of proper equipment and training had forced the MPAJA to go on the defensive. Hanrahan describes the early months of the MPAJA as "''an all-out struggle for bare survival. Most of the Chinese guerillas were ill-prepared, both mentally and physically, to live in the jungle, and the toll from disease, desertions, enemy attacks and insanity increased by the day''". At the end of 18 months, an estimated one-third of the entire guerrilla force perished. Nevertheless, the harsh and brutal treatment of the Chinese by the Japanese occupation forces drove many Chinese to the relative safety of the jungle. The desire for revenge against the Japanese inspired many young Chinese to enlist with the MPAJA guerrillas, thus ensuring a steady supply of recruits to maintain the resistance effort despite suffering from heavy losses.Lai Teck's betrayal and the Batu Caves massacre

Unbeknownst to the leadership of the MCP, the MCP Secretary-General and MPAJA leader Lai Teck was a double agent working for the British Special Branch. Subsequently, he became triple-agent working for the Japanese after his arrest by the '' Kempeitai'' in early March 1942. There were many different accounts of how Lai Teck was caught by the ''Kempeitai'' and his subsequent agreement to collaborate with the Japanese. In his book ''Red Star Over Malaya,'' Cheah Boon Keng describes Lai Teck's arrest as such: : "''Lai Teck was arrested by the Kempeitai in Singapore in early March 1942. Through the interpreter Lee Yem Kong, a former photographer in Johor, Major Onishi and Lai Teck struck a bargain. They agreed that Lai Teck would give the names of the MCP's top executives and gather them in one place where they could be liquidated by the Japanese. In return, Lai Teck's life would be spared and he could earn a considerable sum of money. Towards the end of April he walked out of Kempeitai headquarters 'a free man with a bundle of dollars in his pocket'. Contact was thereafter to be established at a certain cafe in Orchard Road, or Lai Teck would call on his bicycle at the home of Lee Yem Kong, who acted as interpreter for Warrant Officer Shimomura, the man present to receive all information.''" In August 1942 Lai Teck arranged for a full meeting which included the MCP's Central Executive Committee, state party officials, and a group leaders of the MPAJA at the Batu Caves, about ten miles from Kuala Lumpur. The party meeting was then held in a small village near the caves. At daybreak of 1 September 1942, Japanese forces surrounded and attacked the village where the MCP and MPAJA leaders were resting. Caught by surprise, the ambush ended with 92 members of the resistance dead. Among those who were killed, 29 were top-ranking party officials which included 4 MPAJA "Political Commissars". The Batu Caves Massacre had effectively wiped out the entire pre-war leadership of the MCP and influential members of the MPAJA.Revival and expansion

The untimely deaths in the MCP and MPAJA hierarchy provided an opportunity for a new breed of leaders to emerge. Among this new generation of leaders wasChin Peng

Chin Peng (21 October 1924 – 16 September 2013), born Ong Boon Hua, was a British Malaya, Malayan Communism, communist politician, Guerrilla warfare, guerrilla leader, and revolutionary, who was the leader and commander of the Malayan Commun ...

, who would eventually become leader of the MCP and one of the key figures in the post-war conflict with the British government of Malaya. Another individual would be Liao Wei-chung, also known as Colonel Itu, who commanded the MPAJA 5th Independent Regiment from 1943 till the end of the war.

By late 1943 many of the veteran Japanese soldiers were replaced by fresh units which were less successful in executing counter-insurgency operations against the MPAJA. Meanwhile, the MPAJA were able to gain sympathy and widespread support among the Chinese communities in Malaya, who supplied them with food, supplies, intelligence and also fresh recruits. The main link and support organisation which backed the MPAJA was the Malayan People's Anti-Japanese Union (MPAJU). The MPAJU pursued an open policy of recruiting people regardless of race, class, and political belief as long as they were against the Japanese regime. Therefore, members of the MPAJU were not necessarily Chinese or communists.

The MPAJA recruited manpower by organising volunteer units called the Ho Pi Tui (Reserves) in villages, towns and districts. These volunteers were not required to leave their local areas unless they were called up. After a 2-month course in the jungle, they were sent back to their villages and left under the control of village elders or other trusted community representatives to provide self-defense in the villages. By the end of 1944, the MPAJA had increased their membership to over 7,000 soldiers.

Contact with Force 136

After the fall of Singapore, the MPAJA had lost contact with the British command in Southeast Asia. The British attempted to reestablish communications by landing army agents in Malaya by submarine. The first party, consisting of Colonel John Davis and five Chinese agents from the Special Operations Executive organisation called Force 136, landed on the Perak coast on 24 May 1943 from a Dutch submarine. Other groups followed, including Lim Bo Seng, a prominent Straits-born Chinese businessman and KMT supporter who volunteered to join the Force 136 Malayan Unit. On 1 January 1944, MPAJA leaders arrived at the Force 136 camp at Bukit Bidor and entered into discussions with the Force 136 officers.Tie, Y., & Zhong, C. (1995). An Account of the Anti-Japanese War Fought Jointly by the British Government and MPAJA. In C. H. Foong, & C. Show, ''The Price of Peace: True Accounts of the Japanese Occupation'' (pp. 45–63). Singapore: Asiapac Books. The MPAJA agreed to accept the British Army's orders while the war with Japan lasted in return for arms, money, training, and supplies. It was also agreed that at the end of the war, all weapons supplied by Force 136 would be handed back to British authorities, and all MPAJA fighters would disarm and return to civilian life. However, Force 136 was unable to keep several pre-planned rendezvous with its submarines, and had lost its wireless sets; the result was that Allied command did not hear of the agreement until 1 February 1945, and it was only during the last months of the war that the British were able to supply the MPAJA by air. Between December 1944 and August 1945, the number of air drops totalled more than 1000, with 510 men and £1.5 million worth of equipment and supplies parachuted into Malaya.End of Japanese occupation

For the MPAJA, the period from 1944 until the end of the war in August 1945 was characterised as one of both "consolidation" and continued growth. With the Japanese surrender on 15 August 1945, an "interregnum" followed which marked a period of lawlessness and unrest before the delayed arrival of the British forces. During this time, the MPAJA focused its efforts on seizing control of territory across Malaya and punishing "collaborators" of the Japanese regime. Many of the "collaborators" were ethnic Malays, many of whom the Japanese employed as policemen. Although the MCP and MPAJA consistently espoused non-racial policies, the fact that their members came predominantly from the Chinese community caused their reprisals against Malays who had collaborated to be a source of racial tension. As a result, interracial clashes involving the Chinese-dominated MPAJA and Malay settlers were frequent. For example, the Malays in Sungai Manik inPerak

Perak (; Perak Malay: ''Peghok'') is a States and federal territories of Malaysia, state of Malaysia on the west coast of the Malay Peninsula. Perak has land borders with the Malaysian states of Kedah to the north, Penang to the northwest, Kel ...

, fought with the MPAJA and local Chinese settlers after the MPAJA attempted to take over Sungai Manik and other neighbouring towns. Fighting continued until the arrival of the British army in September.

Post-war

Return of British rule

The British Military Administration (BMA) formally took over control of Malaya on 12 September 1945. The British army saw the MPAJA guerrillas as a hindrance to their tasks of establishing law and order in the country and was anxious to demobilise the MPAJA as soon as possible. Fearing that the MPAJA might challenge British authority, the British army ordered all MPAJA units to concentrate in certain centres and to come under its overall command. Force 136 officers would continue to be liaison officers with the MPAJA. The BMA also declared the MPAJA no longer operational after 12 September, although they were allowed to remain armed until negotiations were finalised for their disarmament. Additionally, the MPAJA was not allowed to conduct further extrajudicial punishment on collaborators without permission from the British authorities.

The British Military Administration (BMA) formally took over control of Malaya on 12 September 1945. The British army saw the MPAJA guerrillas as a hindrance to their tasks of establishing law and order in the country and was anxious to demobilise the MPAJA as soon as possible. Fearing that the MPAJA might challenge British authority, the British army ordered all MPAJA units to concentrate in certain centres and to come under its overall command. Force 136 officers would continue to be liaison officers with the MPAJA. The BMA also declared the MPAJA no longer operational after 12 September, although they were allowed to remain armed until negotiations were finalised for their disarmament. Additionally, the MPAJA was not allowed to conduct further extrajudicial punishment on collaborators without permission from the British authorities.

Disbandment of the MPAJA

The MPAJA was formally dissolved on 1 December 1945. A gratuity sum of $350 was paid to each disbanded member of the MPAJA, with the option for him to enter civilian employment or to join the police, volunteer forces or the Malay Regiment. 5,497 weapons were handed in by 6,800 guerrillas in demobilisation ceremonial parades held at MPAJA headquarters around the country. However, it was believed that the MPAJA did not proceed to disarm with full compliance. British authorities discovered that most of the surrendered arms were old-type weapons and suspected that the MPAJA hid the newer weapons in the jungles. One particular incident reinforced this suspicion when the British army stumbled upon an armed Chinese settlement that had its own governing body, military drilling facilities and flag while conducting a raid on one of the old MPAJA encampments. Members of this settlement opened fire at the British soldiers on sight, and the skirmish ended with one Chinese man dead.

The MPAJA was formally dissolved on 1 December 1945. A gratuity sum of $350 was paid to each disbanded member of the MPAJA, with the option for him to enter civilian employment or to join the police, volunteer forces or the Malay Regiment. 5,497 weapons were handed in by 6,800 guerrillas in demobilisation ceremonial parades held at MPAJA headquarters around the country. However, it was believed that the MPAJA did not proceed to disarm with full compliance. British authorities discovered that most of the surrendered arms were old-type weapons and suspected that the MPAJA hid the newer weapons in the jungles. One particular incident reinforced this suspicion when the British army stumbled upon an armed Chinese settlement that had its own governing body, military drilling facilities and flag while conducting a raid on one of the old MPAJA encampments. Members of this settlement opened fire at the British soldiers on sight, and the skirmish ended with one Chinese man dead.

Post-disarmament influence

Nevertheless, after the formal demobilisation of the MPAJA, associations for demobilised personnel, known as the Malayan Peoples Anti-Japanese Ex-Service Comrades Association, were established in areas where regiments had operated. The president and vice-president of the associations were the same men who commanded the MPAJA regiments in their respective areas. In other words, the leadership structure of these veteran clubs mirrored that of the former MPAJA. Although there was no direct evidence that all leaders of these associations were communists, representatives of these veteran clubs participated in meetings with communist-sponsored groups that passed political resolutions. Cheah Boon Keng argues that these ex-guerrilla associations would later become well-organised military arms for the MCP during its open conflict with the BMA in 1948.Organisation

Organisational set-up

Between 1942 and 1945, the MPAJA had a total of 8 independent regiments as follows: All eight independent regiments took orders from the Central Military Committee of the MCP. Therefore, the MPAJA was ''de facto'' controlled by the Communist leadership. Each MPAJA regiment comprised five or six patrols, and the average regimental strength was between 400 and 500 members. The 5th Regiment was considered the strongest under the leadership of Chin Peng, then-Perak State Secretary of the MCP, and Colonel Itu (aka Liao Wei Chung).Membership and life in the MPAJA

There was no class distinction in the MPAJA. Each member addressed each other simply as "comrade", including the Chairman of the Central Military Committee. Although the MPAJA was directly controlled by the MCP leadership, many members were not communists, contrary to popular belief. Many had signed up for the MPAJA because of their resentment towards the Japanese army's brutal treatment of civilians. When not engaged in guerrilla activities, a typical life in an MPAJA camp consisted of military drilling, political education, cooking, collection of food supplies, and cultural affairs. The soldiers organised gatherings and invited residents, particularly the young, to participate in singing and drama events. Whenever these activities were going on, guards armed with machine-guns would be stationed at main exits of villages to keep a look-out for Japanese soldiers. The objectives of such activities was to demonstrate the strength of the group and instill public confidence. Personal accounts by British army officers who lived side by side with MPAJA guerrillas during the war revealed MPAJA cadres as "disciplined people" who had "great seriousness of purpose". The MCP/MPAJA leader,Chin Peng

Chin Peng (21 October 1924 – 16 September 2013), born Ong Boon Hua, was a British Malaya, Malayan Communism, communist politician, Guerrilla warfare, guerrilla leader, and revolutionary, who was the leader and commander of the Malayan Commun ...

, was also labelled as a man "with a reputation for fair dealing". Also, the MPAJA in Perak was said to enjoy good relations with the aborigines, or Orang Asli

The Orang Asli are a Homogeneity and heterogeneity, heterogeneous Indigenous peoples, indigenous population forming a national minority in Malaysia. They are the oldest inhabitants of Peninsular Malaysia.

As of 2017, the Orang Asli accounted f ...

, who "held a party for MPAJA forces" on New Year's Eve.

While the MPAJA was officially a multi-racial organisation, membership was made up predominantly by Chinese. Mandarin was the ''lingua franca

A lingua franca (; ; for plurals see ), also known as a bridge language, common language, trade language, auxiliary language, link language or language of wider communication (LWC), is a Natural language, language systematically used to make co ...

'' of the MPAJA, although concessions to the Malay, Tamil, and English languages were made in some of the propaganda news-sheets published by the MPAJA's propaganda bureau. Nevertheless, there were token numbers of Malay and Indians among their ranks. In Lim Pui Huen's book, ''War and Memory in Malaysia and Singapore'', an Indian war survivor Ramasamy recalled that "in the plantations, news of guerilla activities were often a great joy to the ndian

Ndian is a Departments of Cameroon, department of Southwest Region, Cameroon, Southwest Region in Cameroon. It is located in the humid tropical rainforest zone about southeast of Yaoundé, the capital.

History

Ndian division was formed in 1975 ...

laborers", and that the Indian MPAJA leaders like "Perumal and Muniandy were looked upon… as heroes because they punish the estate ''kirani''".Lim, P., & Wong, D. (2000). ''War and Memory in Malaysia and Singapore.'' Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

The total strength of the MPAJA at the time of demobilisation was said to be between 6,000 and 7,000 soldiers.

Objectives of the MPAJA

The true objectives of the MPAJA remains a debatable issue. While officially the MPAJA was an organisation formed to resist the Japanese invasion, the true motives behind its formation has often been touted by historians as an elaborate ploy by MCP to create an armed force that would resist British imperialism after the end of the Japanese Occupation of Malaya. In Ban and Yap's book ''Rehearsal for War: The Underground War against the Japanese'', both authors argued that "while the MCP cooperated with the British against the more immediate threat from the Japanese, it never detracted from its aim of seizing power" and that its ultimate aim "right from the formation of the party in April 1930… is a communist Malaya". Although the MPAJA was officially a separate organisation from the MCP, it was claimed that "from the start the Malayan Communist Party sought to exert an authoritarian and direct control…with Liu Yao as Chairman to oversee the activities and direction of the MPAJA". The Central Military Commission, which was "reorganized to take full control of the MPAJA", was headed by MCP leaders "Lai Teck, Liu Yao and Chin Peng". Furthermore, the MPAJA deliberately kept "open and secret field units", whereby "portions of the MPAJA field units were carefully kept out of sight, husbanded as reserves for a future conflict." One example was the comparison between the "open" 5th Independent Regiment based in Perak which was the strongest and most active in Malaya, and the "secret" 6th Regiment in Pahang which was as well-equipped but "had a less aggressive stance". In fact, according to Ban and Yap, "within a year of the fall of Malaya it was obvious o the MCP�� that the return of the British was inevitable" and that the "MCP was ready to contend with its former colonial rulers." Although "clashes between the MPAJA and the Japanese Occupation Army occurred, these never threatened the overall Japanese control of the peninsula" as the "MPAJA was conserving its resources for the real war against colonialism once the Japanese were evicted." Therefore, the authors suggest that the MPAJA's main enemy was all along the British, and its main purpose was to wrestle independence from the British rather than to resist the Japanese. Cheah Boon Kheng's ''Red Star Over Malaya'' also echos Ban and Yap's argument. Cheah acknowledges that the MPAJA was under control of the MCP, with the "Central Military Committee of the MCP acted as supreme command of the MPAJA." Cheah also agrees that the MCP harboured hidden motives while agreeing to co-operate with the British against the Japanese by holding on to its "secret strategy of ‘Establish the Malayan Democratic Republic'", "ready to take advantage of the opportunity to expel the British from Malaya as soon as practicable". On the other hand, historian Lee Ting Hui argues against the popular notion that the MCP had planned to use the MPAJA to invoke an armed struggle against the British. In his book ''The Open United Front: The Communist Struggle in Singapore'' he asserts that the MCP "was pursuing the objective of a new democratic revolution" and had "preferred to operate in the open and in conformity with the law". The MCP had adopted Mao Tze Dong's strategy of a "peaceful struggle", which was to take over the countryside and get "workers, peasants and others" to conduct "strikes, acts of sabotage, demonstrations, etc." Following Mao's doctrine, the MPAJA would "forge alliance with its secondary enemy against the primary enemy" in which secondary enemy referred to the British and the primary enemy was the Japanese. Therefore, during the war, the "MCP's only target was the Japanese".Contribution to the war

Casualty figures provided by both MPAJA and Japanese sources differed greatly: With regards to the MPAJA's contribution to the war, here are some assessments given by historians: Cheah, in his assessment of the military results of the MPAJA insurgency, says that "British accounts have reported that the guerrillas carried out a number of military engagements against Japanese installations. The MPAJA's own account claims its guerrillas undertook 340 individual operations against the Japanese during the occupation, of which 230 were considered "major" efforts – "major" meaning involving an entire regiment." The MPAJA claimed to have eliminated 5,500 Japanese troops while losing 1,000 themselves. The Japanese claimed that their losses (killed and wounded) were 600 of their own troops and 2000 local police, and that the MPAJA losses were 2,900. Cheah believes that the Japanese report is probably more reliable, although only approximate. Ban and Yap agree with Cheah in his figures, mentioning that the MPAJA "claimed it had eliminated 5,500 Japanese soldiers and about 2,500 'traitors' while admitting that they had lost some 1,000 men". On the other hand, the Japanese released their "own figures of 600 killed or wounded and 2,000 casualties from their volunteer forces". They also claimed to have "killed some 2,900 members of the MPAJA". However, Ban and Yap feel that the Japanese might have "under-reported their casualties as the MPAJA had always been depicted as a band of ragged bandits who could pose no threat to the Imperial Army". Also, they noted that towards the end of the war the "guerrillas were matching the Japanese blow for blow" and "Japanese records admitted that they suffered some 506 casualties in one of the attacks while 550 guerrillas were killed". Cooper mentions similar casualty figures of both MPAJA and Japanese accounts in his book ''Decade of Change: Malaya and the Straits Settlements 1936–1945'', but nevertheless suggests that the “value of the MPAJA to the Allied cause is debatable” and describes their strategy as “tantalizing he Japanese invariably disappearing into the depths of the jungle whenever the Japanese tried to engage them” because they were “little or no match against the Japanese”. He goes even further to add that the MPAJA's contribution “is no more than a minor irritant and certainly no strategic threat to the Japanese". On the other hand, Tie and Zhong felt that "if the atomic bomb had not put an abrupt end to the 'war and peace' problems, the anti-Japanese force could have achieved even more".References

{{Authority control Anti-Japanese resistance movement in Malaya during World War II British Malaya Communism in Malaysia Former armies by country Japanese occupation of Singapore Military units and formations of British Malaya in World War II Military wings of communist parties South-East Asian theatre of World War II World War II resistance movements