M'Naghten Rule on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The M'Naghten rule(s) (pronounced, and sometimes spelled, McNaughton) is a legal

The M'Naghten rule(s) (pronounced, and sometimes spelled, McNaughton) is a legal

Criminal Procedure (Insanity and Unfitness to Plead) Act 1991

provides that a jury shall not return a special verdict that "the accused is not guilty by reason of insanity" except on the written or oral evidence of two or more registered medical practitioners of whom at least one has special experience in the field of mental disorder. This may require the jury to decide between conflicting medical evidence which they are not necessarily equipped to do, but the law goes further and allows them to disagree with the experts if there are facts or surrounding circumstances which, in the opinion of the court, justify the jury in coming to that conclusion.

Criminal Procedure (Insanity) Act 1964

(as amended): # Where the sentence for the offence to which the finding relates is fixed by law (e.g. murder), the court must make a hospital order (see section 37

*

M'Naghten Rule – FindLaw

{{English criminal law navbox Criminal defenses Forensic psychology English criminal law English law Insanity in law Rules 1843 in British law Mental health legal history of the United Kingdom

The M'Naghten rule(s) (pronounced, and sometimes spelled, McNaughton) is a legal

The M'Naghten rule(s) (pronounced, and sometimes spelled, McNaughton) is a legal test

Test(s), testing, or TEST may refer to:

* Test (assessment), an educational assessment intended to measure the respondents' knowledge or other abilities

Arts and entertainment

* ''Test'' (2013 film), an American film

* ''Test'' (2014 film) ...

defining the defence of insanity that was formulated by the House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the lower house, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. One of the oldest ext ...

in 1843. It is the established standard in UK criminal law. Versions have been adopted in some US states, currently or formerly, and other jurisdictions, either as case law

Case law, also used interchangeably with common law, is a law that is based on precedents, that is the judicial decisions from previous cases, rather than law based on constitutions, statutes, or regulations. Case law uses the detailed facts of ...

or by statute

A statute is a law or formal written enactment of a legislature. Statutes typically declare, command or prohibit something. Statutes are distinguished from court law and unwritten law (also known as common law) in that they are the expressed wil ...

. Its original wording is a proposed jury instruction

Jury instructions, also known as charges or directions, are a set of legal guidelines given by a judge to a jury in a court of law. They are an important procedural step in a trial by jury, and as such are a cornerstone of criminal process in many ...

:

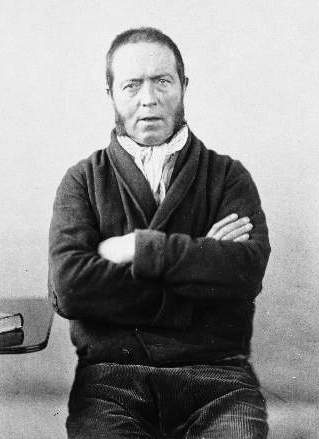

The rule was created in reaction to the acquittal in 1843 of Daniel M'Naghten on the charge of murdering Edward Drummond. M'Naghten had shot Drummond after mistakenly identifying him as the British Prime Minister Robert Peel

Sir Robert Peel, 2nd Baronet (5 February 1788 – 2 July 1850), was a British Conservative statesman who twice was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (1834–1835, 1841–1846), and simultaneously was Chancellor of the Exchequer (1834–183 ...

, who was the intended target. The acquittal of M'Naghten on the basis of insanity, a hitherto unheard-of defence ''per se'' in modern form, caused a public uproar, with protests from the establishment and the press, even prompting Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 year ...

to write to Robert Peel calling for a "wider interpretation of the verdict". The House of Lords, using a medieval right to question judges, asked a panel of judges presided over by Sir Nicolas Conyngham Tindal, Chief Justice of the Common Pleas

The chief justice of the common pleas was the head of the Court of Common Pleas, also known as the Common Bench, which was the second-highest common law

Common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body ...

, a series of hypothetical questions about the defence of insanity. The principles expounded by this panel have come to be known as the "M'Naghten Rules". M'Naghten himself would have been found guilty if they had been applied at his trial.

The rules so formulated as ''M'Naghten's Case'' 1843 10 C & F 200, or variations of them, are a standard test for criminal liability in relation to mentally disordered defendants in various jurisdictions, either in common law

Common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law primarily developed through judicial decisions rather than statutes. Although common law may incorporate certain statutes, it is largely based on prece ...

or enacted by statute

A statute is a law or formal written enactment of a legislature. Statutes typically declare, command or prohibit something. Statutes are distinguished from court law and unwritten law (also known as common law) in that they are the expressed wil ...

. When the tests set out by the rules are satisfied, the accused may be adjudged "not guilty by reason of insanity" or "guilty but insane" and the sentence may be a mandatory or discretionary, but usually indeterminate, period of treatment in a secure hospital facility, or otherwise at the discretion of the court, depending on the country and the offence charged, instead of a punitive disposal.

Historical development

There are various justifications for the exemption of the insane from criminal responsibility. When mental incapacity is successfully raised as a defence in a criminal trial it absolves a defendant from liability: it appliespublic policies

Public policy is an institutionalized proposal or a decided set of elements like laws, regulations, guidelines, and actions to solve or address relevant and problematic social issues, guided by a conception and often implemented by programs. T ...

in relation to criminal responsibility by applying a rationale of compassion

Compassion is a social feeling that motivates people to go out of their way to relieve the physical, mental, or emotional pains of others and themselves. Compassion is sensitivity to the emotional aspects of the suffering of others. When based ...

, accepting that it is morally

Morality () is the categorization of intentions, decisions and actions into those that are ''proper'', or ''right'', and those that are ''improper'', or ''wrong''. Morality can be a body of standards or principles derived from a code of conduc ...

wrong to punish a person if that person is deprived permanently or temporarily of the capacity to form a necessary mental intent that the definition of a crime requires. Punishment of the obviously mentally ill by the state may undermine public confidence in the penal system. A utilitarian

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for the affected individuals. In other words, utilitarian ideas encourage actions that lead to the ...

and humanitarian approach suggests that the interests of society are better served by treatment.

Historically, insanity was seen as grounds for leniency. In pre-Norman times in England there was no distinct criminal code – a murderer could pay compensation to the victim's family under the principle of "buy off the spear or bear it". The insane person's family were expected to pay any compensation for the crime. In Norman times, insanity was not seen as a defence in itself, but a special circumstance in which the jury would deliver a guilty verdict and refer the defendant to the King for a pardon

since they are without sense and reason and can no more commit a tort or a felony than a brute animal, since they are not far removed from brutes, as is evident in the case of a minor, for if he should kill another while under age he would not suffer judgment.In ''R v Arnold'' 1724 16 How St. Tr. 765, the test for insanity was expressed in the following terms

whether the accused is totally deprived of his understanding and memory and knew what he was doing "no more than a wild beast or a brute, or an infant".The next major advance occurred in '' Hadfield's Trial'' 1800 27 How St. Tr. 765, in which the court decided that a crime committed under some delusion would be excused, only if it would have been excusable had the delusion been true. This would deal with the situation, for example, when the accused imagines he is cutting through a loaf of bread, whereas in fact he is cutting through a person's neck. Each jurisdiction may have its own standards of the insanity defence. More than one standard can be applied to any case based on multiple jurisdictions.

M'Naghten rules

TheHouse of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the lower house, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. One of the oldest ext ...

delivered the following exposition of the rules:

the jurors ought to be told in all cases that every man is to be presumed to be sane, and to possess a sufficient degree of reason to be responsible for his crimes, until the contrary be proved to their satisfaction; and that to establish a defence on the ground of insanity, it must be clearly proved that, at the time of the committing of the act, the party accused was labouring under such a defect of reason, from disease of the mind, as not to know the nature and quality of the act he was doing; or, if he did know it, that he did not know he was doing what was wrong.The central issue of this definition may be stated as, "Did the defendant know what he was doing, or, if so, that it was wrong?", and the issues raised have been analysed in subsequent appellate decisions.

Presumption of sanity and burden of proof

Sanity is arebuttable presumption

In law, a presumption is an "inference of a particular fact". There are two types of presumptions: rebuttable presumptions and irrebuttable (or conclusive) presumptions. A rebuttable presumption will either shift the burden of production (requ ...

and the burden of proof is on the party denying it; the standard of proof is on a balance of probabilities, that is to say that mental incapacity is more likely than not. If this burden is successfully discharged, the party relying upon it is entitled to succeed. In Lord Denning's judgement in '' Bratty v Attorney-General for Northern Ireland'' 1963 AC 386, whenever the defendant makes an issue of his state of mind, the prosecution can adduce evidence of insanity. However, this will normally only arise to negate the defence case when automatism or diminished responsibility

In criminal law, diminished responsibility (or diminished capacity) is a potential defense by excuse by which defendants argue that although they broke the law, they should not be held fully criminally liable for doing so, as their mental funct ...

is in issue.

In practical terms, the defence will be more likely to raise the issue of mental incapacity to negate or minimise criminal liability. In ''R v Clarke'' 1972 1 All E R 219 a defendant charged with a shoplifting

Shoplifting (also known as shop theft, shop fraud, retail theft, or retail fraud) is the theft of goods from a retail establishment during business hours. The terms ''shoplifting'' and ''shoplifter'' are not usually defined in law, and genera ...

claimed she had no ''mens rea

In criminal law, (; Law Latin for "guilty mind") is the mental state of a defendant who is accused of committing a crime. In common law jurisdictions, most crimes require proof both of ''mens rea'' and '' actus reus'' ("guilty act") before th ...

'' because she had absent-mindedly walked out of the shop without paying because she suffered from depression. When the prosecution attempted to adduce evidence that this constituted insanity within the Rules, she changed her plea to guilty, but on appeal the Court ruled that she had been merely denying mens rea

In criminal law, (; Law Latin for "guilty mind") is the mental state of a defendant who is accused of committing a crime. In common law jurisdictions, most crimes require proof both of ''mens rea'' and '' actus reus'' ("guilty act") before th ...

rather than raising a defence under the Rules and her conviction was quashed. The general rule was stated that the Rules apply only to cases in which the defect of reason is substantial.

Disease of the mind

Whether a particular condition amounts to a disease of the mind within the Rules is not a medical but a legal question to be decided in accordance with the ordinary rules of interpretation. It seems that any disease which produces a malfunctioning of the mind is a disease of the mind and need not be a disease of the brain itself. The term has been held to cover numerous conditions: The courts have clearly drawn a distinction between internal and external factors affecting a defendant's mental condition. This is partly based on risk of recurrence, whereby the High Court of Australia has expressed that the defence of automatism is unable to be considered when the mental disorder has been proved transient and as such not likely to recur. However, the distinction between insanity and automatism is difficult because the distinction between internal and external divide is difficult. Many diseases consist of a predisposition, considered an internal cause, combined with a precipitant, which would be considered an external cause. Actions committed while sleepwalking would normally be considered as "non-insane automatism", but often alcohol and stress trigger bouts of sleepwalking and make them more likely to be violent. The diabetic who takes insulin but does not eat properly – is that an internal or external cause?Nature and quality of the act

This phrase refers to the physical nature and quality of the act, rather than the moral quality. It covers the situation where the defendant does not know what he is physically doing. Two common examples used are: * The defendant cuts a woman's throat under the delusion that he is cutting a loaf of bread, * The defendant chops off a sleeping man's head because he has the deluded idea that it would be great fun to see the man looking for it when he wakes up. The judges were specifically asked if a person could be excused if he committed an offence in consequence of an insane delusion. They replied that if he labours under such partial delusion only, and is not in other respects insane, "he must be considered in the same situation as to responsibility as if the facts with respect to which the delusion exists were real". This rule requires the court to take the facts as the accused believed them to be and follows ''Hadfield's Trial'', above. If the delusions do not prevent the defendant from having mens rea there will be no defence. In ''R v Bell'' 1984 Crim. LR 685, the defendant smashed a van through the entrance gates of a holiday camp because "It was like a secret society in there, I wanted to do my bit against it" as instructed by God. It was held that, as the defendant had been aware of his actions, he could neither have been in a state of automatism nor insane, and the fact that he believed that God had told him to do this merely provided an explanation of his motive and did not prevent him from knowing that what he was doing was wrong in the legal sense.Knowledge that the act was wrong

The interpretation of this clause is a subject of controversy among legal authorities, and different standards may apply in different jurisdictions. "Wrong" was interpreted to mean ''legally'' wrong, rather than ''morally'' wrong, in the case of ''Windle'' 1952 2QB 826; 1952 2 All ER 1 246, where the defendant killed his wife with an overdose ofaspirin

Aspirin () is the genericized trademark for acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) used to reduce pain, fever, and inflammation, and as an antithrombotic. Specific inflammatory conditions that aspirin is ...

; he telephoned the police and said, "I suppose they will hang me for this." It was held that this was sufficient to show that although the defendant was suffering from a mental illness, he was aware that his act was wrong, and the defence was not allowed.

Under this interpretation, there may be cases where the mentally ill know that their conduct is legally prohibited, but it is arguable that their mental condition prevents them making the connection between an act being legally prohibited and the societal requirement to conform their conduct to the requirements of the criminal law.

As an example of a contrasting interpretation in which defendant lacking knowledge that the act was ''morally'' wrong meets the M'Naghten standards, there are the instructions the judge is required to provide to the jury in cases in New York State when the defendant has raised an insanity plea as a defence:

... with respect to the term "wrong", a person lacks substantial capacity to know or appreciate that conduct is wrong if that person, as a result of mental disease or defect, lacked substantial capacity to know or appreciate either that the conduct was against the law or that it was against commonly held moral principles, or both.There is other support in the authorities for this interpretation of the standards enunciated in the findings presented to the House of Lords regarding M'Naghten's case:

If it be accepted, as can hardly be denied, that the answers of the judges to the questions asked by the House of Lords in 1843 are to be read in the light of the then existing case-law and not as novel pronouncements of a legislative character, then the ustralianHigh Court's analysis in ''Stapleton's Case'' is compelling. Their exhaustive examination of the extensive case-law concerning the defence of insanity prior to and at the time of the trial of M'Naughten establishes convincingly that it was morality and not legality which lay as a concept behind the judges' use of "wrong" in the M'Naghten rules.

Offences of strict liability

In ''DPP v Harper'' (1997) it was held that insanity is not generally a defence tostrict liability

In criminal and civil law, strict liability is a standard of liability under which a person is legally responsible for the consequences flowing from an activity even in the absence of fault or criminal intent on the part of the defendant.

Und ...

offences. In this instance, the accused was driving with excess alcohol. By definition, the accused is sufficiently aware of the nature of the activity to commit the ''actus reus'' of driving and presumably knows that driving while drunk is legally wrong. Any other feature of the accused's knowledge is irrelevant.

Function of the jury

Section 1 of the United KingdomsCriminal Procedure (Insanity and Unfitness to Plead) Act 1991

provides that a jury shall not return a special verdict that "the accused is not guilty by reason of insanity" except on the written or oral evidence of two or more registered medical practitioners of whom at least one has special experience in the field of mental disorder. This may require the jury to decide between conflicting medical evidence which they are not necessarily equipped to do, but the law goes further and allows them to disagree with the experts if there are facts or surrounding circumstances which, in the opinion of the court, justify the jury in coming to that conclusion.

Sentencing

Under section 5 of the United Kingdom'Criminal Procedure (Insanity) Act 1964

(as amended): # Where the sentence for the offence to which the finding relates is fixed by law (e.g. murder), the court must make a hospital order (see section 37

Mental Health Act 1983

The Mental Health Act 1983 (c. 20) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It covers the reception, care and treatment of mentally disordered people, the management of their property and other related matters, forming part of the me ...

) with a restriction order limiting discharge and other rights (see section 41 Mental Health Act 1983

The Mental Health Act 1983 (c. 20) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It covers the reception, care and treatment of mentally disordered people, the management of their property and other related matters, forming part of the me ...

).

# In any other case the court may make:

#* a hospital order (with or without a restriction order);

#* a supervision order; or

#* an order for absolute discharge.

Criticisms

There have been four major criticisms of the law as it currently stands: * Medical irrelevance – The legal definition of insanity has not advanced significantly since 1843; in 1953 evidence was given to the Royal Commission on Capital Punishment that doctors even then regarded the legal definition to be obsolete and misleading. This distinction has led to absurdities such as ** even though a legal definition suffices, mandatory hospitalisation can be ordered in cases of murder; if the defendant is not ''medically'' insane, there is little point in requiring medical treatment. ** Article 5 of theEuropean Convention on Human Rights

The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR; formally the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms) is a Supranational law, supranational convention to protect human rights and political freedoms in Europe. Draf ...

, imported into English law by the Human Rights Act 1998

The Human Rights Act 1998 (c. 42) is an Act of Parliament (United Kingdom), Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom which received royal assent on 9 November 1998, and came into force on 2 October 2000. Its aim was to incorporate into UK law the ...

, provides that a person of unsound mind may be detained only where proper account of objective medical expertise has been taken. As yet, no cases have occurred in which this point has been argued.

* Ineffectiveness – The rules currently do not distinguish between defendants who represent a public danger and those who do not. Illnesses such as diabetes and epilepsy can be controlled by medication such that sufferers are less likely to have temporary aberrations of mental capacity, but the law does not recognise this.

* Sentencing for murder – A finding of insanity may well result in indefinite confinement in a hospital, whereas a conviction for murder may well result in a determinate sentence of between ten and 15 years; faced with this choice, it may be that defendants would prefer the certainty of the latter option. The defence of diminished responsibility in section 2(1) of the Homicide Act would reduce the conviction to voluntary manslaughter with more discretion on the part of the judge in regards to sentencing.

* Scope – A practical issue is whether the fact that an accused is labouring under a "mental disability" should be a necessary but not sufficient condition for negating responsibility i.e. whether the test should also require an incapacity to understand what is being done, to know that what one is doing is wrong, or to control an impulse to do something and so demonstrate a causal link between the disability and the potentially criminal acts and omissions. For example, the Irish insanity defence comprises the M'Naghten Rules and a control test that asks whether the accused was debarred from refraining from committing the act because of a defect of reason due to mental illness (see ''Doyle v Wicklow County Council'' 1974) 55 IR 71. The Butler Committee recommended that proof of severe mental disorder should be sufficient to negate responsibility, in effect creating an irrebuttable presumption of irresponsibility arising from proof of a severe mental disorder. This has been criticised as it assumes a lack of criminal responsibility simply because there is evidence of some sort of mental dysfunction, rather than establishing a standard of criminal responsibility. According to this view, the law should be geared to culpability

In criminal law, culpability, or being culpable, is a measure of the degree to which an agent, such as a person, can be held morally or legally responsible for action and inaction. It has been noted that the word ''culpability'' "ordinarily has ...

not mere psychiatric diagnosis.

Alternative rules

Theinsanity defence

The insanity defense, also known as the mental disorder defense, is an affirmative defense by excuse in a criminal case, arguing that the defendant is not responsible for their actions due to a psychiatric disease at the time of the criminal act ...

article has a number of alternative tests that have been used at different times and places. As one example, the ALI test replaced the M'Naghten rule in many parts of the United States for many years until the 1980s; when, in the aftermath of John Hinckley shooting US President Ronald Reagan, many ALI states returned to a variation of M'Naghten.

Case law

*'' People v. Drew''In popular culture

The M'Naghten rules are at the focus ofJohn Grisham

John Ray Grisham Jr. (; born February 8, 1955) is an American novelist, lawyer, and former politician, known for his best-selling legal thrillers. According to the Academy of Achievement, American Academy of Achievement, Grisham has written 37 ...

's legal thriller '' A Time to Kill''. The M'Naghten rules apply in the US State of Mississippi

Mississippi ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Alabama to the east, the Gulf of Mexico to the south, Louisiana to the s ...

, where the plot is set, and using them is the only way for the lawyer protagonist to save his client.

See also

*Insanity defence

The insanity defense, also known as the mental disorder defense, is an affirmative defense by excuse in a criminal case, arguing that the defendant is not responsible for their actions due to a psychiatric disease at the time of the criminal act ...

* Policeman at the elbow

*

References

Notes Bibliography * Boland, F. (1996). "Insanity, the Irish Constitution and the European Convention on Human Rights". 47 ''Northern Ireland Legal Quarterly'' 260. * * Butler Committee. (1975). ''The Butler Committee on Mentally Abnormal Offenders'', London: HMSO, Cmnd 6244 * * * Gostin, L. (1982). "Human Rights, Judicial Review and the Mentally Disordered Offender". (1982) ''Crim. LR'' 779. * The Law Reform Commission of Western Australia. ''The Criminal Process and Persons Suffering from Mental Disorder'', Project No. 69, August 1991*

External links

M'Naghten Rule – FindLaw

{{English criminal law navbox Criminal defenses Forensic psychology English criminal law English law Insanity in law Rules 1843 in British law Mental health legal history of the United Kingdom