Lunar Orbit Rendezvous on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Lunar orbit rendezvous (LOR) is a process for landing humans on the Moon and returning them to Earth. It was utilized for the Apollo program missions in the 1960s and 1970s. In a LOR mission, a main spacecraft and a smaller lunar lander travel to

Lunar orbit rendezvous (LOR) is a process for landing humans on the Moon and returning them to Earth. It was utilized for the Apollo program missions in the 1960s and 1970s. In a LOR mission, a main spacecraft and a smaller lunar lander travel to

The main advantage of LOR is the spacecraft payload saving, due to the fact that the propellant necessary to return from lunar orbit back to Earth need not be carried as dead weight down to the Moon and back into lunar orbit. This has a multiplicative effect, because each pound of "dead weight" propellant used later has to be propelled by more propellant sooner, and also because increased propellant requires increased tankage weight. The resultant weight increase would also require more thrust for lunar landing, which means larger and heavier engines.

Another advantage is that the lunar lander can be designed for just that purpose, rather than requiring the main spacecraft to also be made suitable for a lunar landing. Finally, the second set of life support systems that the lunar lander requires can serve as a backup for the systems in the main spacecraft.

The main advantage of LOR is the spacecraft payload saving, due to the fact that the propellant necessary to return from lunar orbit back to Earth need not be carried as dead weight down to the Moon and back into lunar orbit. This has a multiplicative effect, because each pound of "dead weight" propellant used later has to be propelled by more propellant sooner, and also because increased propellant requires increased tankage weight. The resultant weight increase would also require more thrust for lunar landing, which means larger and heavier engines.

Another advantage is that the lunar lander can be designed for just that purpose, rather than requiring the main spacecraft to also be made suitable for a lunar landing. Finally, the second set of life support systems that the lunar lander requires can serve as a backup for the systems in the main spacecraft.

When the Apollo Moon landing program was started in 1961, it was assumed that the three-man command and service module combination (CSM) would be used for takeoff from the lunar surface, and return to Earth. It would therefore have to be landed on the Moon by a larger rocket stage with landing gear legs, resulting in a very large spacecraft (in excess of ) to be sent to the Moon.

If this were done by

When the Apollo Moon landing program was started in 1961, it was assumed that the three-man command and service module combination (CSM) would be used for takeoff from the lunar surface, and return to Earth. It would therefore have to be landed on the Moon by a larger rocket stage with landing gear legs, resulting in a very large spacecraft (in excess of ) to be sent to the Moon.

If this were done by

Dr.

Dr.  In the following months, NASA did just that, and to the surprise of many both inside and outside the agency, LOR quickly became the front runner. Several factors decided the issue in its favor. First, there was growing disenchantment with the idea of

In the following months, NASA did just that, and to the surprise of many both inside and outside the agency, LOR quickly became the front runner. Several factors decided the issue in its favor. First, there was growing disenchantment with the idea of

*The proposed Soviet lunar landing plan, using the

*The proposed Soviet lunar landing plan, using the

lunar orbit

In astronomy, lunar orbit (also known as a selenocentric orbit) is the orbit of an object around the Moon.

As used in the space program, this refers not to the orbit of the Moon about the Earth, but to orbits by spacecraft around the Moon. The ...

. The lunar lander then independently descends to the surface of the Moon, while the main spacecraft remains in lunar orbit. After completion of the mission there, the lander returns to lunar orbit to rendezvous and re- dock with the main spacecraft, then is discarded after transfer of crew and payload. Only the main spacecraft returns to Earth.

Lunar orbit rendezvous was first proposed in 1919 by Ukrainian engineer Yuri Kondratyuk, as the most economical way of sending a human on a round-trip journey to the Moon.

The most famous example involved Project Apollo's command and service module

The Apollo command and service module (CSM) was one of two principal components of the United States Apollo spacecraft, used for the Apollo program, which landed astronauts on the Moon between 1969 and 1972. The CSM functioned as a mother sh ...

(CSM) and lunar module (LM), where they were both sent to a translunar flight in a single rocket stack. However, variants where the landers and main spacecraft travel separately, such as the lunar landing plan proposed for Shuttle-Derived Heavy Lift Launch Vehicle and Golden Spike

The golden spike (also known as The Last Spike) is the ceremonial 17.6-karat gold final spike driven by Leland Stanford to join the rails of the first transcontinental railroad across the United States connecting the Central Pacific Railroad ...

, are also considered as Lunar Orbit rendezvous.

Advantages and disadvantages

Advantages

The main advantage of LOR is the spacecraft payload saving, due to the fact that the propellant necessary to return from lunar orbit back to Earth need not be carried as dead weight down to the Moon and back into lunar orbit. This has a multiplicative effect, because each pound of "dead weight" propellant used later has to be propelled by more propellant sooner, and also because increased propellant requires increased tankage weight. The resultant weight increase would also require more thrust for lunar landing, which means larger and heavier engines.

Another advantage is that the lunar lander can be designed for just that purpose, rather than requiring the main spacecraft to also be made suitable for a lunar landing. Finally, the second set of life support systems that the lunar lander requires can serve as a backup for the systems in the main spacecraft.

The main advantage of LOR is the spacecraft payload saving, due to the fact that the propellant necessary to return from lunar orbit back to Earth need not be carried as dead weight down to the Moon and back into lunar orbit. This has a multiplicative effect, because each pound of "dead weight" propellant used later has to be propelled by more propellant sooner, and also because increased propellant requires increased tankage weight. The resultant weight increase would also require more thrust for lunar landing, which means larger and heavier engines.

Another advantage is that the lunar lander can be designed for just that purpose, rather than requiring the main spacecraft to also be made suitable for a lunar landing. Finally, the second set of life support systems that the lunar lander requires can serve as a backup for the systems in the main spacecraft.

Disadvantage

Lunar-orbit rendezvous was considered risky as of 1962, becausespace rendezvous

A space rendezvous () is a set of orbital maneuvers during which two spacecraft, one of which is often a space station, arrive at the same orbit and approach to a very close distance (e.g. within visual contact). Rendezvous requires a precise ...

had not been achieved, even in Earth orbit. If the LM could not reach the CSM, two astronauts would be stranded with no way to get back to Earth or survive re-entry into the atmosphere. The fear proved to be unfounded, as rendezvous was successfully demonstrated in 1965 and 1966 on six Project Gemini

Project Gemini () was NASA's second human spaceflight program. Conducted between projects Mercury and Apollo, Gemini started in 1961 and concluded in 1966. The Gemini spacecraft carried a two-astronaut crew. Ten Gemini crews and 16 individual ...

missions with the aid of radar and on-board computers. It was also successfully done each of the eight times it was tried on Apollo missions.

Apollo Mission mode selection

When the Apollo Moon landing program was started in 1961, it was assumed that the three-man command and service module combination (CSM) would be used for takeoff from the lunar surface, and return to Earth. It would therefore have to be landed on the Moon by a larger rocket stage with landing gear legs, resulting in a very large spacecraft (in excess of ) to be sent to the Moon.

If this were done by

When the Apollo Moon landing program was started in 1961, it was assumed that the three-man command and service module combination (CSM) would be used for takeoff from the lunar surface, and return to Earth. It would therefore have to be landed on the Moon by a larger rocket stage with landing gear legs, resulting in a very large spacecraft (in excess of ) to be sent to the Moon.

If this were done by direct ascent

Direct ascent is a method of landing a spacecraft on the Moon or another planetary surface directly, without first assembling the vehicle in Earth orbit, or carrying a separate landing vehicle into orbit around the target body. It was proposed as ...

(on a single launch vehicle

A launch vehicle or carrier rocket is a rocket designed to carry a payload (spacecraft or satellites) from the Earth's surface to outer space. Most launch vehicles operate from a launch pad, launch pads, supported by a missile launch contro ...

), the rocket required would have to be extremely large, in the Nova

A nova (plural novae or novas) is a transient astronomical event that causes the sudden appearance of a bright, apparently "new" star (hence the name "nova", which is Latin for "new") that slowly fades over weeks or months. Causes of the dramati ...

class. The alternative to this would have been Earth orbit rendezvous, in which two or more rockets in the Saturn class would launch parts of the complete spacecraft, which would rendezvous in Earth orbit before departing for the Moon. This would possibly include a separately launched Earth departure stage, or require on-orbit refueling of the empty departure stage.

Wernher von Braun

Wernher Magnus Maximilian Freiherr von Braun ( , ; 23 March 191216 June 1977) was a German and American aerospace engineer and space architect. He was a member of the Nazi Party and Allgemeine SS, as well as the leading figure in the develop ...

and Heinz-Hermann Koelle Heinz-Hermann Koelle (22 July 1925, in Danzig, Free City of Danzig – 20 February 2011, in Berlin, Germany) was an aeronautical engineer who made the preliminary designs on the rocket that would emerge as the Saturn I. Closely associated wi ...

of the Army Ballistic Missile Agency

The Army Ballistic Missile Agency (ABMA) was formed to develop the U.S. Army's first large ballistic missile. The agency was established at Redstone Arsenal on 1 February 1956, and commanded by Major General John B. Medaris with Wernher von ...

presented lunar orbit rendezvous, as an option for reaching the moon efficiently, to the heads of NASA, including Abe Silverstein

Abraham "Abe" Silverstein

NASA.gov. Retrieved September 17, 2009. (September 15, 1908June 1, 2001) was an American engine ...

, in December 1958. During 1959 NASA.gov. Retrieved September 17, 2009. (September 15, 1908June 1, 2001) was an American engine ...

Conrad Lau

Conrad Albert 'Connie' Lau (February 8, 1921 – April 18, 1964) was an American aeronautical engineer, inventor, and executive. Lau led or contributed to the development of a number of important aircraft and spacecraft projects.

Early life ...

of the Chance-Vought Astronautics Division supervised a complete mission plan using lunar orbit rendezvous which was then sent to Silverstein at NASA in January 1960. Tom Dolan

Thomas Fitzgerald Dolan (born September 15, 1975) is an American former competition swimmer, two-time Olympic champion, and former world record-holder.

Dolan grew up in Arlington, Virginia. He attended the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, wh ...

, who worked for Lau, was sent to explain the company's proposal to NASA engineers and management in February 1960. This alternative was then studied and promoted by Jim Chamberlin

James Arthur Chamberlin (May 23, 1915 – March 8, 1981) was a Canadian engineer who contributed to the design of the Canadian Avro Arrow, NASA's Gemini spacecraft and the Apollo program. In addition to his pioneering air and space efforts, he ...

and Owen Maynard

Owen Eugene Maynard (October 27, 1924 – July 15, 2000) was a Canadians, Canadian engineer who contributed to the designs of the Canadian CF-105 Avro Arrow jet interceptor, and of NASA's Apollo program, Apollo Lunar Module (LM). Maynard was a mem ...

at the Space Task Group

The Space Task Group was a working group of NASA engineers created in 1958, tasked with managing America's human spaceflight programs. Headed by Robert Gilruth and based at the Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia, it managed Project Me ...

in the 1960 early Apollo feasibility studies. This mode allowed a single Saturn V

Saturn V is a retired American super heavy-lift launch vehicle developed by NASA under the Apollo program for human exploration of the Moon. The rocket was human-rated, with multistage rocket, three stages, and powered with liquid-propellant r ...

to launch the CSM to the Moon with a smaller LEM. When the combined spacecraft reaches lunar orbit

In astronomy, lunar orbit (also known as a selenocentric orbit) is the orbit of an object around the Moon.

As used in the space program, this refers not to the orbit of the Moon about the Earth, but to orbits by spacecraft around the Moon. The ...

, one of the three astronauts remains with the CSM, while the other two enter the LEM, undock and descend to the surface of the Moon. They then use the ascent stage of the LEM to rejoin the CSM in lunar orbit, then discard the LEM and use the CSM for the return to Earth. This method was brought to the attention of NASA Associate Administrator Robert Seamans

Robert Channing Seamans Jr. (October 30, 1918 – June 28, 2008) was an MIT professor who served as NASA Deputy Administrator and 9th United States Secretary of the Air Force.

Birth and education

He was born in Salem, Massachusetts, to Pauli ...

by Langley Research Center

The Langley Research Center (LaRC or NASA Langley), located in Hampton, Virginia, United States of America, is the oldest of NASA's field centers. It directly borders Langley Air Force Base and the Back River on the Chesapeake Bay. LaRC has fo ...

engineer John C. Houbolt, who led a team to develop it.

Besides requiring less payload, the ability to use a lunar lander designed just for that purpose was another advantage of the LOR approach. The LEM's design gave the astronauts a clear view of their landing site through observation windows approximately above the surface, as opposed to being on their backs in a Command Module lander, at least above the surface, able to see it only through a television screen.

Developing the LEM as a second crewed vehicle provided the further advantage of redundant critical systems (electrical power, life support, and propulsion), which enabled it to be used as a "lifeboat" to keep the astronauts alive and get them home safely in the event of a critical CSM system failure. This was envisioned as a contingency, but not made a part of the LEM specifications. As it turned out, this capability proved invaluable in 1970, saving the lives of the Apollo 13

Apollo 13 (April 1117, 1970) was the seventh crewed mission in the Apollo space program and the third meant to land on the Moon. The craft was launched from Kennedy Space Center on April 11, 1970, but the lunar landing was aborted aft ...

astronauts when an oxygen tank explosion disabled the Service Module.

Advocacy

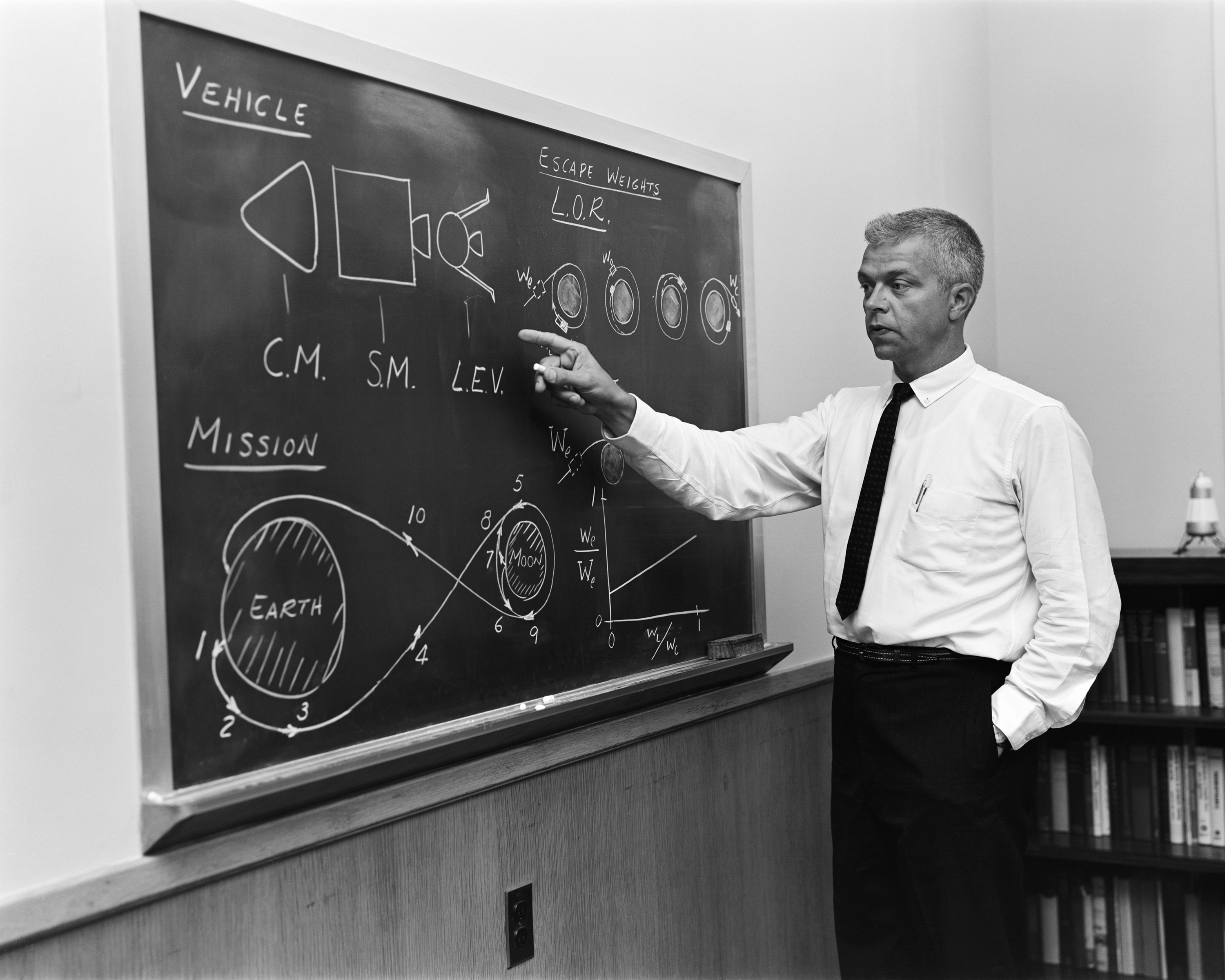

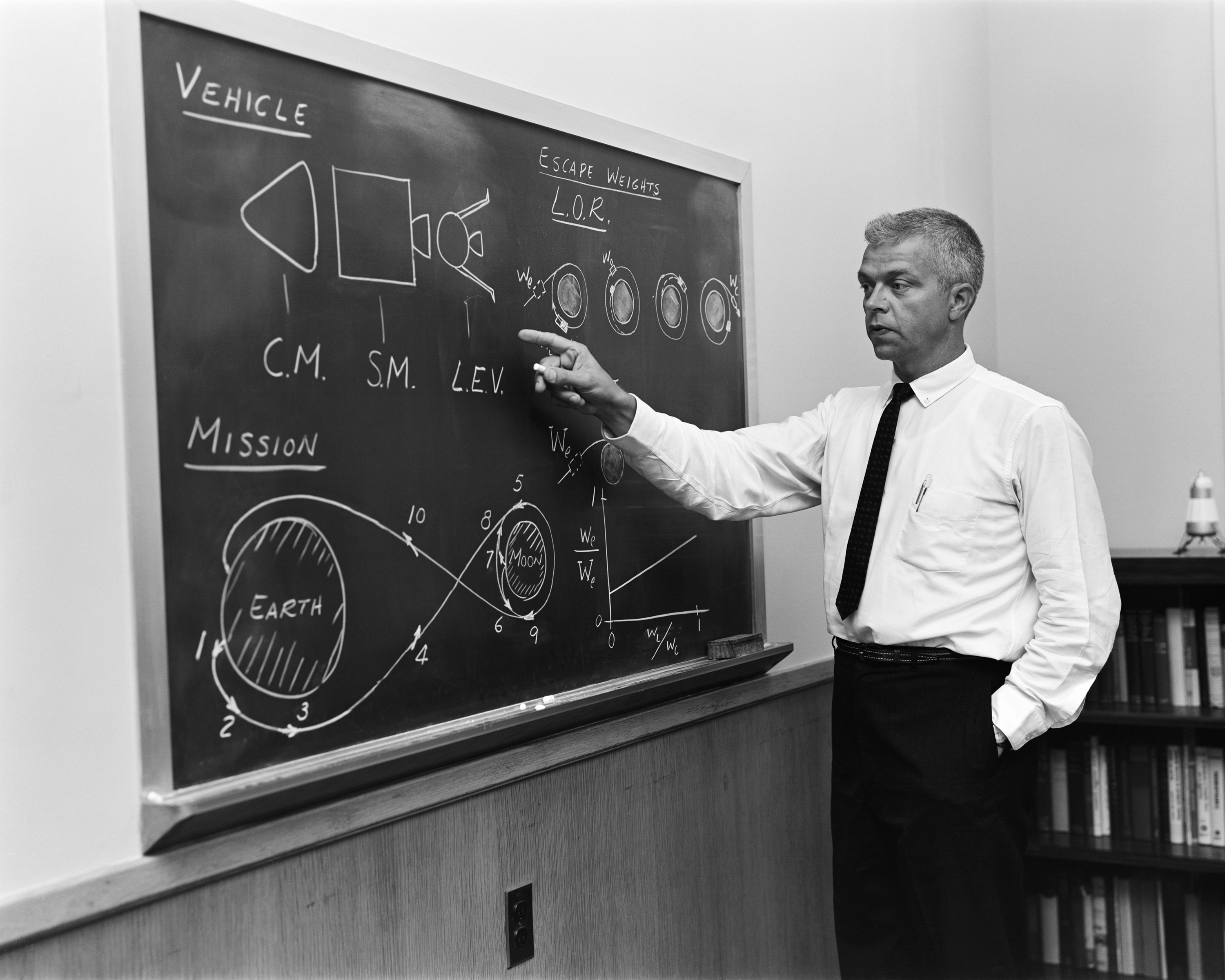

Dr.

Dr. John Houbolt

John Cornelius Houbolt (April 10, 1919 – April 15, 2014) was an aerospace engineer credited with leading the team behind the lunar orbit rendezvous (LOR) mission mode, a concept that was used to successfully land humans on the Moon and return t ...

would not let the advantages of LOR be ignored. As a member of Lunar Mission Steering Group, Houbolt had been studying various technical aspects of space rendezvous

A space rendezvous () is a set of orbital maneuvers during which two spacecraft, one of which is often a space station, arrive at the same orbit and approach to a very close distance (e.g. within visual contact). Rendezvous requires a precise ...

since 1959 and was convinced, like several others at Langley Research Center

The Langley Research Center (LaRC or NASA Langley), located in Hampton, Virginia, United States of America, is the oldest of NASA's field centers. It directly borders Langley Air Force Base and the Back River on the Chesapeake Bay. LaRC has fo ...

, that LOR was not only the most feasible way to make it to the Moon before the decade was out, it was the only way. He had reported his findings to NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil space program, aeronautics research, and space research.

NASA was established in 1958, succeeding t ...

on various occasions but felt strongly that the internal task forces (to which he made presentations) were following arbitrarily established "ground rules." According to Houbolt, these ground rules were constraining NASA's thinking about the lunar mission—and causing LOR to be ruled out before it was fairly considered.

In November 1961, Houbolt took the bold step of skipping proper channels and writing a nine-page private letter directly to associate administrator Robert C. Seamans. "Somewhat as a voice in the wilderness," Houbolt protested LOR's exclusion. "Do we want to go to the Moon or not?" the Langley engineer asked. "Why is Nova, with its ponderous size simply just accepted, and why is a much less grandiose scheme involving rendezvous ostracized or put on the defensive? I fully realize that contacting you in this manner is somewhat unorthodox," Houbolt admitted, "but the issues at stake are crucial enough to us all that an unusual course is warranted."

It took two weeks for Seamans to reply to Houbolt's letter. The associate administrator agreed that "it would be extremely harmful to our organization and to the country if our qualified staff were unduly limited by restrictive guidelines." He assured Houbolt that NASA would in the future be paying more attention to LOR than it had up to this time.

In the following months, NASA did just that, and to the surprise of many both inside and outside the agency, LOR quickly became the front runner. Several factors decided the issue in its favor. First, there was growing disenchantment with the idea of

In the following months, NASA did just that, and to the surprise of many both inside and outside the agency, LOR quickly became the front runner. Several factors decided the issue in its favor. First, there was growing disenchantment with the idea of direct ascent

Direct ascent is a method of landing a spacecraft on the Moon or another planetary surface directly, without first assembling the vehicle in Earth orbit, or carrying a separate landing vehicle into orbit around the target body. It was proposed as ...

due to the time and money it was going to take to develop a diameter Nova rocket

A nova (plural novae or novas) is a transient astronomical event that causes the sudden appearance of a bright, apparently "new" star (hence the name "nova", which is Latin for "new") that slowly fades over weeks or months. Causes of the dramat ...

, compared to the diameter Saturn V

Saturn V is a retired American super heavy-lift launch vehicle developed by NASA under the Apollo program for human exploration of the Moon. The rocket was human-rated, with multistage rocket, three stages, and powered with liquid-propellant r ...

. Second, there was increasing technical apprehension over how the relatively large spacecraft demanded by Earth-orbit rendezvous would be able to maneuver to a soft landing on the Moon. As one NASA engineer who changed his mind explained: The business of eyeballing that thing down to the Moon really didn't have a satisfactory answer. The best thing about LOR was that it allowed us to build a separate vehicle for landing.The first major group to change its opinion in favor of LOR was

Robert Gilruth

Robert Rowe Gilruth (October 8, 1913 – August 17, 2000) was an American aerospace engineer and an aviation/space pioneer who was the first director of NASA's Manned Spacecraft Center, later renamed the Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center.

He worked ...

's Space Task Group, which was still located at Langley but was soon to move to Houston as the Manned Spacecraft Center

The Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center (JSC) is NASA's center for human spaceflight (originally named the Manned Spacecraft Center), where human spaceflight training, research, and flight control are conducted. It was renamed in honor of the late U ...

. The second to come over was Wernher von Braun

Wernher Magnus Maximilian Freiherr von Braun ( , ; 23 March 191216 June 1977) was a German and American aerospace engineer and space architect. He was a member of the Nazi Party and Allgemeine SS, as well as the leading figure in the develop ...

's team at the Marshall Space Flight Center

The George C. Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC), located in Redstone Arsenal, Alabama (Huntsville postal address), is the U.S. government's civilian rocketry and spacecraft propulsion research center. As the largest NASA center, MSFC's first ...

in Huntsville, Alabama

Huntsville is a city in Madison County, Limestone County, and Morgan County, Alabama, United States. It is the county seat of Madison County. Located in the Appalachian region of northern Alabama, Huntsville is the most populous city in t ...

. These two powerful groups, along with the engineers who had originally developed the plan at Langley, persuaded key officials at NASA Headquarters, notably Administrator James Webb, who had been holding out for direct ascent, that LOR was the only way to land on the Moon by 1969. Webb approved LOR in July 1962. The decision was officially announced at a press conference on July 11, 1962. President Kennedy's science adviser, Jerome Wiesner

Jerome Bert Wiesner (May 30, 1915 – October 21, 1994) was a professor of electrical engineering, chosen by President John F. Kennedy as chairman of his Science Advisory Committee (PSAC). Educated at the University of Michigan, Wiesner was assoc ...

, remained firmly opposed to LOR.

Other plans using LOR

*The proposed Soviet lunar landing plan, using the

*The proposed Soviet lunar landing plan, using the N1 rocket

The N1/L3 (from , "Carrier Rocket"; Cyrillic: Н1) was a super heavy-lift launch vehicle intended to deliver payloads beyond low Earth orbit. The N1 was the Soviet counterpart to the US Saturn V and was intended to enable crewed travel to the ...

, LK Lander and Soyuz 7K-LOK

The Soyuz 7K-LOK, or simply LOK (russian: Лунный Орбитальный Корабль, translit=Lunniy Orbitalny Korabl meaning "Lunar Orbital Craft") was a Soviet crewed spacecraft designed to launch men from Earth to orbit the Moon, deve ...

, would have used a similar LOR mission profile.

*The Constellation program

The Constellation program (abbreviated CxP) was a crewed spaceflight program developed by NASA, the space agency of the United States, from 2005 to 2009. The major goals of the program were "completion of the International Space Station" and a " ...

would have used a combination of EOR

The ''Ear'' rune of the Anglo-Saxon runes, Anglo-Saxon futhorc is a late addition to the alphabet. It is, however, still attested from epigraphical evidence, notably the Thames scramasax, and its introduction thus cannot postdate the 9th century ...

and LOR for Moon landing.

* The Artemis program

The Artemis program is a robotic and human Moon exploration program led by the United States' National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) along with three partner agencies: European Space Agency (ESA), Japan Aerospace Exploration ...

plans to use LOR to land humans on the lunar south pole

The lunar south pole is the southernmost point on the Moon, at 90°S. It is of special interest to scientists because of the occurrence of water ice in permanently shadowed areas around it. The lunar south pole region features craters that ar ...

region.

In popular culture

Episode 5 of the 1998television miniseries

A miniseries or mini-series is a television series that tells a story in a predetermined, limited number of episodes. "Limited series" is another more recent US term which is sometimes used interchangeably. , the popularity of miniseries format h ...

''From the Earth to the Moon

''From the Earth to the Moon: A Direct Route in 97 Hours, 20 Minutes'' (french: De la Terre à la Lune, trajet direct en 97 heures 20 minutes) is an 1865 novel by Jules Verne. It tells the story of the Baltimore Gun Club, a post-American Civil W ...

'', "Spider", dramatizes John Houbolt

John Cornelius Houbolt (April 10, 1919 – April 15, 2014) was an aerospace engineer credited with leading the team behind the lunar orbit rendezvous (LOR) mission mode, a concept that was used to successfully land humans on the Moon and return t ...

's first attempt to convince NASA to adopt LOR for the Apollo Program in 1961, and traces the development of the LM up to its first crewed test flight, Apollo 9

Apollo 9 (March 313, 1969) was the third human spaceflight in NASA's Apollo program. Flown in low Earth orbit, it was the second crewed Apollo mission that the United States launched via a Saturn V rocket, and was the first flight of the ful ...

, in 1969. The episode is named after the Apollo 9 Lunar Module.

See also

*Lunar orbit insertion

In astronomy, lunar orbit (also known as a selenocentric orbit) is the orbit of an object around the Moon.

As used in the space program, this refers not to the orbit of the Moon about the Earth, but to orbits by spacecraft around the Moon. The ...

*Trans-lunar injection

A trans-lunar injection (TLI) is a propulsive maneuver used to set a spacecraft on a trajectory that will cause it to arrive at the Moon.

History

The first space probe to attempt TLI was the Soviet Union's Luna 1 on January 2, 1959 which wa ...

*Trans-Earth injection

A trans-Earth injection (TEI) is a propulsion maneuver used to set a spacecraft on a trajectory which will intersect the Earth's sphere of influence, usually putting the spacecraft on a free return trajectory.

The maneuver is performed by a ro ...

Notes

References

Citations

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

{{Use American English, date=June 2019 Spaceflight concepts Apollo program Space rendezvous