Lyndon Hermyle LaRouche Jr. (September 8, 1922 – February 12, 2019) was an American political activist who founded the

LaRouche movement and its main organization, the

National Caucus of Labor Committees (NCLC).

He was a prominent

conspiracy theorist and

perennial presidential candidate.

He began in

far-left

Far-left politics, also known as extreme left politics or left-wing extremism, are politics further to the left on the left–right political spectrum than the standard political left. The term does not have a single, coherent definition; some ...

politics in the 1940s and later supported the

civil rights movement; however, in the 1970s, he moved to the

far-right

Far-right politics, often termed right-wing extremism, encompasses a range of ideologies that are marked by ultraconservatism, authoritarianism, ultranationalism, and nativism. This political spectrum situates itself on the far end of the ...

.

His movement is sometimes described as, or likened to, a

cult

Cults are social groups which have unusual, and often extreme, religious, spiritual, or philosophical beliefs and rituals. Extreme devotion to a particular person, object, or goal is another characteristic often ascribed to cults. The term ...

.

Convicted of fraud, he served five years in prison from 1989 to 1994.

Born in

Rochester, New Hampshire

Rochester is a city in Strafford County, New Hampshire, United States. The population was 32,492 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, making it the List of municipalities in New Hampshire, 6th most populous city in New Hampshire. In ad ...

, LaRouche was drawn to

socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

and

Marxist

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflic ...

movements in his twenties during

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. In the 1950s, while a

Trotskyist

Trotskyism (, ) is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Russian revolutionary and intellectual Leon Trotsky along with some other members of the Left Opposition and the Fourth International. Trotsky described himself as an ...

, he was also a

management consultant

Management consulting is the practice of providing consulting services to organizations to improve their performance or in any way to assist in achieving organizational objectives. Organizations may draw upon the services of management consultant ...

in New York City.

By the 1960s, he became engaged in increasingly smaller and more radical splinter groups. During the 1970s, he created the foundation of the LaRouche movement and became more engaged in conspiratorial beliefs and violent and illegal activities. Instead of the radical left, he embraced

radical right politics and

antisemitism

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

.

At various times, he alleged that he had been targeted for assassination by

Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 19268 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until Death and state funeral of Elizabeth II, her death in 2022. ...

,

Zionist

Zionism is an Ethnic nationalism, ethnocultural nationalist movement that emerged in History of Europe#From revolution to imperialism (1789–1914), Europe in the late 19th century that aimed to establish and maintain a national home for the ...

mobsters, his own associates (who he said had been drugged and brainwashed by

CIA and British spies), in addition to others.

It is estimated that the LaRouche movement never exceeded a few thousand members, but it had an outsized political influence,

raising more than $200 million by one estimate,

and running candidates in more than 4,000 elections in the 1980s.

It was noted for disguising its candidates as conservative Democrats and harassing opponents.

It reached its height in electoral success when Larouchite candidates won the Democratic primaries for the

1986 Illinois gubernatorial election and related state offices; this alarmed Democratic Party officials, whose national spokesman called the Larouchites "kook fringe".

The defeated mainstream Democratic candidates ran in the general election as members of the

Illinois Solidarity Party; the Larouchite Democrats all finished a distant third. Later in the 1980s, as part of the

LaRouche criminal trials, criminal investigations led to convictions of several LaRouche movement members, including LaRouche himself. He was sentenced to 15 years' imprisonment but served only five.

LaRouche was a perennial candidate for

President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal government of t ...

. He ran in every election from 1976 to 2004 as a candidate of third parties established by members of his movement, peaking at around 78,000 votes in the

1984 United States presidential election.

He also tried to gain the Democratic presidential nomination. In the

1996 Democratic Party presidential primaries, he received 5% of the total nationwide vote. In 2000, he received enough primary votes to qualify for delegates in some states, but the

Democratic National Committee

The Democratic National Committee (DNC) is the principal executive leadership board of the United States's Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party. According to the party charter, it has "general responsibility for the affairs of the ...

refused to seat his delegates and barred LaRouche from attending the

Democratic National Convention

The Democratic National Convention (DNC) is a series of presidential nominating conventions held every four years since 1832 by the United States Democratic Party. They have been administered by the Democratic National Committee since the 18 ...

.

Early life

LaRouche was born in Rochester, New Hampshire, the oldest of three children of Jessie Lenore ( Weir) and Lyndon H. LaRouche Sr. His paternal grandfather's family emigrated to the United States from

Rimouski

Rimouski ( ; ) is a city in Quebec, Canada. Rimouski is located in the Bas-Saint-Laurent region, at the mouth of the Rimouski River. It has a population of 48,935 (as of 2021). Rimouski, whose motto is ''Legi patrum fidelis'' (Faithful to ...

, Quebec, whereas his maternal grandfather was born in

Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

. His father worked for the

United Shoe Machinery Corporation in Rochester before the family moved to

Lynn, Massachusetts

Lynn is the eighth-largest List of municipalities in Massachusetts, municipality in Massachusetts, United States, and the largest city in Essex County, Massachusetts, Essex County. Situated on the Atlantic Ocean, north of the Boston city line ...

.

His parents became

Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestantism, Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally ...

after his father converted from

Catholicism

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

. They forbade him from fighting with other children, even in self-defense, which he said led to "years of hell" from bullies at school. As a result, he spent much of his time alone, taking long walks through the woods and identifying in his mind with great philosophers. He wrote that, between the ages of 12 and 14, he read philosophy extensively, embracing the ideas of

Leibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (or Leibnitz; – 14 November 1716) was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat who is credited, alongside Sir Isaac Newton, with the creation of calculus in addition to many ...

and rejecting those of

Hume,

Bacon

Bacon is a type of Curing (food preservation), salt-cured pork made from various cuts of meat, cuts, typically the pork belly, belly or less fatty parts of the back. It is eaten as a side dish (particularly in breakfasts), used as a central in ...

,

Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5 April 1588 – 4 December 1679) was an English philosopher, best known for his 1651 book ''Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influential formulation of social contract theory. He is considered to be one of the founders ...

,

Locke,

Berkeley,

Rousseau, and

Kant

Immanuel Kant (born Emanuel Kant; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German philosopher and one of the central Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works in epistemology, metaphysics, et ...

. He graduated from

Lynn English High School in 1940. In the same year, the Lynn Quakers expelled his father from the group, for reportedly accusing other Quakers of misusing funds, while writing under the pen name Hezekiah Micajah Jones. LaRouche and his mother resigned in sympathy with his father.

University studies, Marxism, marriage

LaRouche attended

Northeastern University

Northeastern University (NU or NEU) is a private university, private research university with its main campus in Boston, Massachusetts, United States. It was founded by the Boston Young Men's Christian Association in 1898 as an all-male instit ...

in

Boston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

and left in 1942. He later wrote that his teachers "lacked the competence to teach me on conditions I was willing to tolerate".

[, p. 3] As a Quaker, he was a

conscientious objector

A conscientious objector is an "individual who has claimed the right to refuse to perform military service" on the grounds of freedom of conscience or religion. The term has also been extended to objecting to working for the military–indu ...

during

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

and joined a

Civilian Public Service camp in lieu of military service. In 1944, he decided to enlist in the

United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

and served with the

Medical Corps

A medical corps is generally a military branch or staff corps, officer corps responsible for medical care for serving military personnel. Such officers are typically military physicians.

List of medical corps

The following organizations are exam ...

in

India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

and

Burma

Myanmar, officially the Republic of the Union of Myanmar; and also referred to as Burma (the official English name until 1989), is a country in northwest Southeast Asia. It is the largest country by area in Mainland Southeast Asia and ha ...

during the

Burma campaign

The Burma campaign was a series of battles fought in the British colony of British rule in Burma, Burma as part of the South-East Asian theatre of World War II. It primarily involved forces of the Allies of World War II, Allies (mainly from ...

. At the end of the war, he was working as a clerk in the

Ordnance Corps, and later described his decision to enlist as the most important decision of his life. In his 1988 autobiography, LaRouche said that being asked to express his views on the death of President

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

to a group of fellow

G.I.s led him to define his "principal lifelong political commitment, that the United States should take postwar world leadership in establishing a world order dedicated to promoting the economic development of what we call today "

developing nations

A developing country is a sovereign state with a less-developed industrial base and a lower Human Development Index (HDI) relative to developed countries. However, this definition is not universally agreed upon. There is also no clear agreemen ...

".

LaRouche wrote that he discussed

Marxism

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflict, ...

in the CO camp, and while traveling home on the SS ''General Bradley'' in 1946, he met Don Merrill, a fellow soldier, also from Lynn, who converted him to

Trotskyism

Trotskyism (, ) is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Russian revolutionary and intellectual Leon Trotsky along with some other members of the Left Opposition and the Fourth International. Trotsky described himself as an ...

. Back in the U.S., he resumed his education at Northeastern University but dropped out.

He returned to Lynn in 1948 and the next year joined the

Socialist Workers Party (SWP) to recruit at the GE River Works there, adopting the name "Lyn Marcus" for his political work.

He arrived in New York City in 1953, where he worked as a

management consultant

Management consulting is the practice of providing consulting services to organizations to improve their performance or in any way to assist in achieving organizational objectives. Organizations may draw upon the services of management consultant ...

. In 1954 he married Janice Neuberger, a member of the SWP. Their son, Daniel, was born in 1956.

Career

1960s

Teaching and the National Caucus of Labor Committees

By 1961, the LaRouches were living on

Central Park West

Eighth Avenue is a major north–south avenue on the west side of Manhattan in New York City, carrying northbound traffic below 59th Street. It is one of the original avenues of the Commissioners' Plan of 1811 to run the length of Manhattan, ...

in

Manhattan

Manhattan ( ) is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the Boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City. Coextensive with New York County, Manhattan is the County statistics of the United States#Smallest, larg ...

, and LaRouche's activities were mostly focused on his career and not on the SWP. He and his wife separated in 1963, and he moved into a

Greenwich Village

Greenwich Village, or simply the Village, is a neighborhood on the west side of Lower Manhattan in New York City, bounded by 14th Street (Manhattan), 14th Street to the north, Broadway (Manhattan), Broadway to the east, Houston Street to the s ...

apartment with another SWP member, Carol Schnitzer, also known as Larrabee. In 1964 he began an association with an SWP faction called the

Revolutionary Tendency, a faction later expelled from the SWP, and came under the influence of British Trotskyist leader

Gerry Healy

Thomas Gerard Healy (3 December 1913 – 14 December 1989) was an Irish-born British political activist, a co-founder of the International Committee of the Fourth International and the leader of the Socialist Labour League and later the Work ...

.

For six months, LaRouche worked with American Healyite leader

Tim Wohlforth, who later wrote that LaRouche had a "gargantuan ego" and "a marvelous ability to place any world happening in a larger context, which seemed to give the event additional meaning, but his thinking was schematic, lacking factual detail and depth." Leaving Wohlforth's group, LaRouche briefly joined the rival

Spartacist League before announcing his intention to build a new

Fifth International

The phrase Fifth International refers to the efforts made by groups of socialists and communists to create a new workers' international.

Previous internationals

There have been several previous international workers' organisations, and the ...

.

[, undated.]

In 1967, LaRouche began teaching classes on Marx's

dialectical materialism

Dialectical materialism is a materialist theory based upon the writings of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels that has found widespread applications in a variety of philosophical disciplines ranging from philosophy of history to philosophy of scien ...

at New York City's Free School,

and attracted a group of students from

Columbia University

Columbia University in the City of New York, commonly referred to as Columbia University, is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Churc ...

and the

City College of New York

The City College of the City University of New York (also known as the City College of New York, or simply City College or CCNY) is a Public university, public research university within the City University of New York (CUNY) system in New York ...

, recommending that they read ''

Das Kapital

''Capital: A Critique of Political Economy'' (), also known as ''Capital'' or (), is the most significant work by Karl Marx and the cornerstone of Marxian economics, published in three volumes in 1867, 1885, and 1894. The culmination of his ...

'', as well as

Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a 19th-century German idealism, German idealist. His influence extends across a wide range of topics from metaphysical issues in epistemology and ontology, to political phi ...

, Kant, and Leibniz. During the

1968 Columbia University protests, he organized his supporters under the name ''

National Caucus of Labor Committees'' (NCLC).

The aim of the NCLC was to win control of the

Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) branchthe university's main activist groupand build a political alliance between students, local residents, organized labor, and the Columbia faculty. By 1973, the NCLC had over 600 members in 25 citiesincluding West Berlin and Stockholmand produced what LaRouche's biographer, Dennis King, called the most literate of the far-left papers, ''New Solidarity''. The NCLC's internal activities became highly regimented over the next few years. Members gave up their jobs and devoted themselves to the group and its leader, believing it would soon take control of America's trade unions and overthrow the government.

1970s

1971: Intelligence network

Robert J. Alexander writes that LaRouche first established an NCLC "intelligence network" in 1971. Members all over the world sent information to NCLC headquarters, which would distribute the information via briefings and other publications. LaRouche organized the network as a series of news services and magazines, which critics say was done to gain access to government officials under press cover. The publications included ''

Executive Intelligence Review'', founded in 1974. Other periodicals under his aegis included ''New Solidarity'', ''Fusion Magazine'', ''21st Century Science and Technology'', and ''Campaigner Magazine''. His news services and publishers included American System Publications, Campaigner Publications, New Solidarity International Press Service, and The New Benjamin Franklin House Publishing Company. LaRouche acknowledged in 1980 that his followers impersonated reporters and others, saying it had to be done for his security. In 1982, ''

U.S. News & World Report'' sued New Solidarity International Press Service and Campaigner Publications for damages, alleging that members were impersonating its reporters in phone calls.

U.S. sources told ''

The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'', locally known as ''The'' ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'' or ''WP'', is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C., the national capital. It is the most widely circulated newspaper in the Washington m ...

'' in 1985 that the LaRouche organization had assembled a worldwide network of government and military contacts, and that his researchers sometimes supplied information to government officials.

Bobby Ray Inman, the CIA's deputy director in 1981 and 1982, said LaRouche and his wife had visited him, offering information about the West German Green Party. A CIA spokesman said LaRouche met Deputy Director John McMahon in 1983 to discuss one of LaRouche's trips overseas. An aide to Deputy Secretary of State

William Clark said when LaRouche's associates discussed technology or economics, they made good sense and seemed qualified. Norman Bailey, formerly with the

U.S. National Security Council, said in 1984 that LaRouche's staff comprised "one of the best private intelligence services in the world. ... They do know a lot of people around the world. They do get to talk to prime ministers and presidents." Several government officials feared a security leak from the government's ties with the movement. According to critics, the supposed behind-the-scenes processes were more often flights of fancy than inside information. Douglas Foster wrote in ''

Mother Jones'' in 1982 that the briefings consisted of disinformation, "hate-filled" material about enemies, phony letters, intimidation, fake newspaper articles, and dirty tricks campaigns. Opponents were accused of being gay or

Nazis

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During H ...

, or were linked to murders, which the movement called "psywar techniques".

From the 1970s to the first decade of the 21st century, LaRouche founded several groups and companies. In addition to the National Caucus of Labor Committees, there was the

Citizens Electoral Council (Australia), the National Democratic Policy Committee, the

Fusion Energy Foundation, and the

U.S. Labor Party. In 1984, he founded the

Schiller Institute in Germany with his second wife, and three political parties therethe ''

Europäische Arbeiterpartei'', ''Patrioten für Deutschland'', and ''

Bürgerrechtsbewegung Solidarität

Bürgerrechtsbewegung Solidarität (BüSo), or the Civil Rights Movement Solidarity, is a German political party founded by Helga Zepp-LaRouche, the widow of U.S. political activist Lyndon LaRouche.

The BüSo is part of the worldwide LaRouche mo ...

''and in 2000 the

Worldwide LaRouche Youth Movement. His printing services included Computron Technologies, Computype, World Composition Services, and PMR Printing Company, Inc, or PMR Associates.

1973: Political shift; "Operation Mop-Up"

LaRouche wrote in his 1987 autobiography that violent altercations had begun in 1969 between his NCLC members and several

New Left

The New Left was a broad political movement that emerged from the counterculture of the 1960s and continued through the 1970s. It consisted of activists in the Western world who, in reaction to the era's liberal establishment, campaigned for freer ...

groups when

Mark Rudd's faction began assaulting LaRouche's faction at Columbia University. Press accounts alleged that between April and September 1973, during what LaRouche called "Operation Mop-Up", NCLC members began physically attacking members of leftist groups that LaRouche classified as "left-protofascists"; an editorial in LaRouche's ''New Solidarity'' said of the

Communist Party that the movement "must dispose of this stinking corpse". Armed with chains, bats, and martial-art

nunchuk sticks, NCLC members assaulted Communist Party, SWP, and

Progressive Labor Party members and

Black Power

Black power is a list of political slogans, political slogan and a name which is given to various associated ideologies which aim to achieve self-determination for black people. It is primarily, but not exclusively, used in the United States b ...

activists on the streets and during meetings. At least 60 assaults were reported. The operation ended when police arrested several of LaRouche's followers; there were no convictions, and LaRouche maintained they had acted in self-defense. Journalist and LaRouche biographer Dennis King writes that the

FBI

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic Intelligence agency, intelligence and Security agency, security service of the United States and Federal law enforcement in the United States, its principal federal law enforcement ag ...

may have tried to aggravate the strife, using measures such as anonymous mailings, to keep the groups at each other's throats. LaRouche said he met representatives of the Soviet Union at the United Nations in 1974 and 1975 to discuss attacks by the Communist Party USA on the NCLC and propose a merger, but said he received no assistance from them. One FBI memo, obtained under the

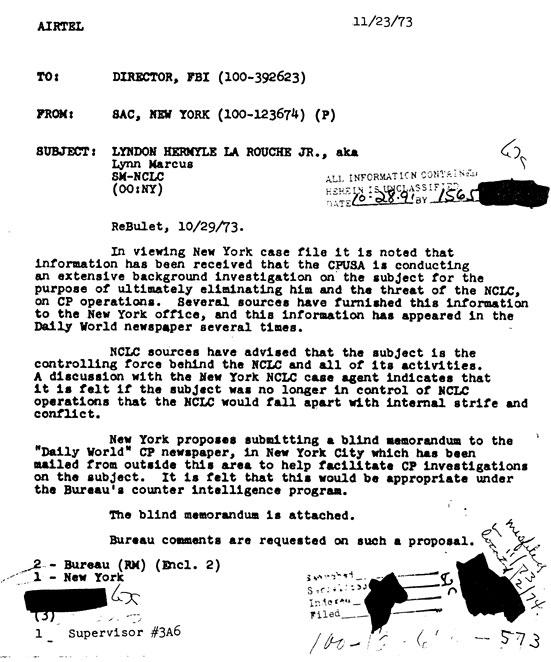

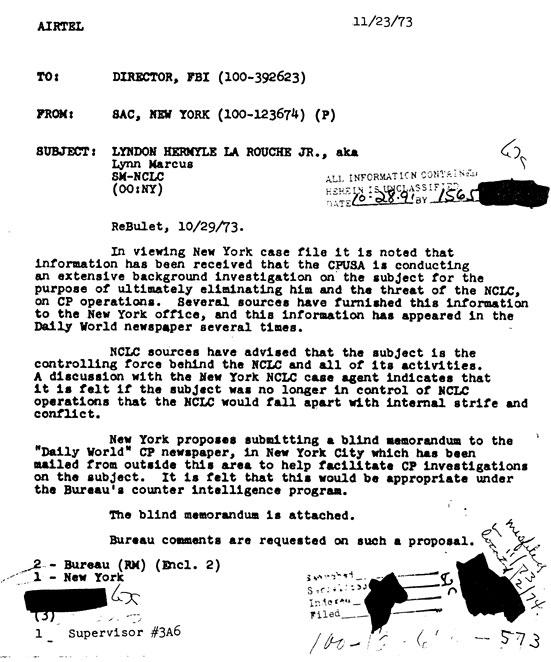

Freedom of Information Act, proposes assisting the CPUSA in an investigation "for the purpose of ultimately eliminating him

aRoucheand the threat of the NCLC" (see image to left).

LaRouche's critics, such as King and

Antony Lerman, allege that in 1973, with little warning, LaRouche adopted more extreme ideas, a process accompanied by a campaign of violence against his opponents on the left, and the development of conspiracy theories and paranoia about his personal safety.

[, p. 212.] According to these accounts, he began to believe he was under threat of assassination from the Soviet Union, the CIA, Libya, drug dealers, and bankers.

[Mintz, December 18, 1987]

. He also established a "Biological Holocaust Task Force", which, according to LaRouche, analyzed the public health consequences of

International Monetary Fund

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is a major financial agency of the United Nations, and an international financial institution funded by 191 member countries, with headquarters in Washington, D.C. It is regarded as the global lender of las ...

(IMF) austerity policies for impoverished nations in Africa, and predicted that epidemics of

cholera

Cholera () is an infection of the small intestine by some Strain (biology), strains of the Bacteria, bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea last ...

as well as possibly entirely new diseases would strike Africa in the 1980s.

[.]

1973: U.S. Labor Party

LaRouche founded the U.S. Labor Party in 1973 as the political arm of the NCLC. At first, the party was "preaching Marxist revolution"; however, by 1977, it shifted from left-wing to

right-wing politics

Right-wing politics is the range of Ideology#Political ideologies, political ideologies that view certain social orders and Social stratification, hierarchies as inevitable, natural, normal, or desirable, typically supporting this position b ...

. A two-part article in ''

The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' in 1979 by

Howard Blum and

Paul L. Montgomery alleged that LaRouche had turned the party (at that point with 1,000 members in 37 offices in North America, and 26 in Europe and Latin America) into an extreme-right,

antisemitic organization, despite the presence of

Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

members. LaRouche denied the newspaper's charges, and said he had filed a $100 million libel suit; his press secretary said the articles were intended to "set up a credible climate for an assassination hit".

The ''Times'' alleged that members had taken courses in how to use knives and rifles; that a farm in upstate New York had been used for guerrilla training; and that several members had undergone a six-day anti-terrorist training course run by

Mitchell WerBell III, an arms dealer and former member of the

Office of Strategic Services

The Office of Strategic Services (OSS) was the first intelligence agency of the United States, formed during World War II. The OSS was formed as an agency of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) to coordinate espionage activities behind enemy lines ...

, who said he had ties to the

CIA. Journalists and publications the party regarded as unfriendly were harassed, and it published a list of potential assassins it saw as a threat. LaRouche expected members to devote themselves entirely to the party, place their savings and possessions at its disposal, and take out loans on its behalf. Party officials decided who each member should live with, and if someone left the movement, the remaining member was expected to live separately from the ex-member. LaRouche questioned spouses about their partner's sexual habits, the ''Times'' said, and in one case reportedly ordered a member to stop having sex with his wife, because it was making him "politically impotent".

[Blum, October 7, 1979]

.

1973: "Ego-stripping" and "brainwashing" allegations

LaRouche began writing in 1973 about the use of certain psychological techniques on recruits. In an article called "Beyond Psychoanalysis", he wrote that a worker's persona had to be stripped away to arrive at a state he called "little me", from which it would be possible to "rebuild their personalities around a new socialist identity", according to ''

The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'', locally known as ''The'' ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'' or ''WP'', is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C., the national capital. It is the most widely circulated newspaper in the Washington m ...

''. ''The New York Times'' wrote that the first such sessionwhich LaRouche called "ego-stripping"involved a German member, Konstantin George, in the summer of 1973. LaRouche said that during the session he discovered that a plot to assassinate him had been implanted in George's mind.

[

He recorded sessions with a 26-year-old British member, Chris White, who had moved to England with LaRouche's former partner, Carol Schnitzer. In December 1973 LaRouche asked the couple to return to the U.S. His followers sent tapes of the subsequent sessions with White to ''The New York Times'' as evidence of an assassination plot. According to the ''Times'', " ere are sounds of weeping, and vomiting on the tapes, and Mr. White complains of being deprived of sleep, food and cigarettes. At one point someone says 'raise the voltage', but aRouchesays this was associated with the bright lights used in the questioning rather than an electric shock." The ''Times'' wrote: "Mr. White complains of a terrible pain in his arm, then LaRouche can be heard saying, 'That's not real. That's in the program'." LaRouche told the newspaper White had been "reduced to an eight-cycle infinite loop with look-up table, with homosexual bestiality". He said White had not been harmed and that a physiciana LaRouche movement memberhad been present throughout.][Montgomery, January 20, 1974]

, p. 51, column 5. White ended up telling LaRouche he had been programmed by the CIA and British intelligence to set up LaRouche for assassination by Cuban exile frogmen.[.]

According to ''The Washington Post'', "brainwashing hysteria" took hold of the movement. One activist said he attended meetings where members were writhing on the floor saying they needed de-programming.[ In two weeks in January 1974, the group issued 41 separate press releases about brainwashing. One activist, Alice Weitzman, expressed skepticism about the claims.

]

1974: Contacts with far-right groups, intelligence gathering

LaRouche established contacts with Willis Carto

Willis Allison Carto (July 17, 1926 – October 26, 2015) was an Far right in the United States, American far-right political activist. He described himself as a Jeffersonian democracy, Jeffersonian and a Right-wing populism, populist, but wa ...

's Liberty Lobby and elements of the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to KKK or Klan, is an American Protestant-led Christian terrorism, Christian extremist, white supremacist, Right-wing terrorism, far-right hate group. It was founded in 1865 during Reconstruction era, ...

in 1974. Frank Donner and Randall Rothenberg wrote that he made successful overtures to the Liberty Lobby and George Wallace

George Corley Wallace Jr. (August 25, 1919 – September 13, 1998) was an American politician who was the 45th and longest-serving governor of Alabama (1963–1967; 1971–1979; 1983–1987), and the List of longest-serving governors of U.S. s ...

's American Independent Party, adding that the "racist" policies of LaRouche's U.S. Labor Party endeared it to members of the Ku Klux Klan. George Michael

George Michael (born Georgios Kyriacos Panayiotou; 25 June 1963 – 25 December 2016) was an English singer-songwriter and record producer. Regarded as a pop culture icon, he is one of the List of best-selling music artists, best-selling rec ...

, in ''Willis Carto and the American Far Right'', says that LaRouche shared with the Liberty Lobby's Willis Carto

Willis Allison Carto (July 17, 1926 – October 26, 2015) was an Far right in the United States, American far-right political activist. He described himself as a Jeffersonian democracy, Jeffersonian and a Right-wing populism, populist, but wa ...

an antipathy towards the Rockefeller family

The Rockefeller family ( ) is an American Industrial sector, industrial, political, and List of banking families, banking family that owns one of the world's largest fortunes. The fortune was made in the History of the petroleum industry in th ...

.[

Gregory Rose, a former chief of counter-intelligence for LaRouche who became an FBI informant in 1973, said that while the LaRouche movement had extensive links to the Liberty Lobby, there was also copious evidence of a connection to the ]Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

. George and Wilcox say neither connection amounted to muchthey assert that LaRouche was "definitely not a Soviet agent" and state that while the contact with the Liberty Lobby is often used to imply links' and 'ties' between LaRouche and the extreme right", it was in fact transient and marked by mutual suspicion. The Liberty Lobby soon pronounced itself disillusioned with LaRouche, citing his movement's adherence to "basic socialist positions" and his softness on "the major Zionist

Zionism is an Ethnic nationalism, ethnocultural nationalist movement that emerged in History of Europe#From revolution to imperialism (1789–1914), Europe in the late 19th century that aimed to establish and maintain a national home for the ...

groups" as fundamental points of difference. According to George and Wilcox, American neo-Nazi

Neo-Nazism comprises the post–World War II militant, social, and political movements that seek to revive and reinstate Nazism, Nazi ideology. Neo-Nazis employ their ideology to promote hatred and Supremacism#Racial, racial supremacy (ofte ...

leaders expressed misgivings over the number of Jews and members of other minority groups in his organization, and did not consider LaRouche an ally. George Johnson, in ''Architects of Fear'', similarly states that LaRouche's overtures to far right groups were pragmatic rather than sincere. A 1975 party memo spoke of uniting with these groups only to overthrow the established order, adding that once that goal had been accomplished, "eliminating our right-wing opposition will be comparatively easy".

Howard Blum wrote in ''The New York Times'' that, from 1976 onward, party members sent reports to the FBI and local police regarding members of left-wing organizations. In 1977, he wrote, commercial reports on U.S. anti-apartheid groups were prepared by LaRouche members for the South African government, student dissidents were reported to the Shah of Iran's Savak secret police, and the anti-nuclear movement was investigated on behalf of power companies.Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to KKK or Klan, is an American Protestant-led Christian terrorism, Christian extremist, white supremacist, Right-wing terrorism, far-right hate group. It was founded in 1865 during Reconstruction era, ...

and the American Nazi Party.Ford Foundation

The Ford Foundation is an American private foundation with the stated goal of advancing human welfare. Created in 1936 by Edsel Ford and his father Henry Ford, it was originally funded by a $25,000 (about $550,000 in 2023) gift from Edsel Ford. ...

among its clients, and that his PMR Associates produced the party's publications and some high school newspapers.[Blum, October 7, 1979](_blank)

.

Around the same time, according to Blum, LaRouche was telling his membership several times a year that he was being targeted for assassination, including by the Queen of the United Kingdom, Zionist mobsters, the Council on Foreign Relations

The Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) is an American think tank focused on Foreign policy of the United States, U.S. foreign policy and international relations. Founded in 1921, it is an independent and nonpartisan 501(c)(3) nonprofit organi ...

, the Justice Department, and the Mossad

The Institute for Intelligence and Special Operations (), popularly known as Mossad ( , ), is the national intelligence agency of the Israel, State of Israel. It is one of the main entities in the Israeli Intelligence Community, along with M ...

.

1975–1976: presidential campaign

In March 1975, Clarence M. Kelley, director of the FBI, testified before the House Appropriations Committee that the NCLC was "a violence-oriented organization of 'revolutionary socialists' with a membership of nearly 1,000 in chapters in some 50 cities". He said that during the previous two years its members had been "involved in fights, beatings, using drugs, kidnappings, brainwashings, and at least one shooting. They are reported to be armed, to have received defensive training such as karate, and to attend cadre schools and training schools to learn military tactics".

In March 1975, Clarence M. Kelley, director of the FBI, testified before the House Appropriations Committee that the NCLC was "a violence-oriented organization of 'revolutionary socialists' with a membership of nearly 1,000 in chapters in some 50 cities". He said that during the previous two years its members had been "involved in fights, beatings, using drugs, kidnappings, brainwashings, and at least one shooting. They are reported to be armed, to have received defensive training such as karate, and to attend cadre schools and training schools to learn military tactics".[Rosenfeld, September 24, 1976]

.

* For Clarence Kelley's statement, se

"Nomination of Hon. Andrew Young as U.S. Representative to U.N."

, Committee on Foreign Relations, January 25, 1977, p. 49.

In 1975, under the name ''Lyn Marcus'', LaRouche published '' Dialectical Economics: An Introduction to Marxist Political Economy'', described by its only reviewer as "the most peculiar and idiosyncratic" introduction to economics he had ever seen. Mixing economics, history, anthropology, sociology and a surprisingly large helping of business administration

Business administration is the administration of a commercial enterprise. It includes all aspects of overseeing and supervising the business operations of an organization.

Overview

The administration of a business includes the performance o ...

, the work argued that most prominent Marxists had misunderstood Marx, and that bourgeois

The bourgeoisie ( , ) are a class of business owners, merchants and wealthy people, in general, which emerged in the Late Middle Ages, originally as a "middle class" between the peasantry and Aristocracy (class), aristocracy. They are tradition ...

economics arose when philosophy took a wrong, reductionist turn under British empiricists like Locke and Hume.[McLemee, Scott]

The LaRouche Youth Movement

, ''Inside Higher Ed

''Inside Higher Ed'' is an American online publication of news, opinion, resources, events and jobs in the higher education sphere. In 2022, Quad Partners, a private equity firm, sold it to Times Higher Education, itself owned by Inflexion Priv ...

'', July 11, 2007matching funds

Matching funds are funds that are set to be paid in proportion to funds available from other sources. Matching fund payments usually arise in situations of charity or public good. The terms cost sharing, in-kind, and matching can be used inter ...

; candidates seeking their party's presidential nomination qualify for matching funds if they raise $5,000 in each of at least 20 states. His platform predicted financial disaster by 1980 accompanied by famine and the virtual extinction of the human race within 15 years, and proposed a debt moratorium; nationalization of banks; government investment in industry especially in the aerospace sector, and an "International Development Bank" to facilitate higher food production. When Legionnaires' disease

Legionnaires' disease is a form of atypical pneumonia caused by any species of ''Legionella'' bacteria, quite often ''Legionella pneumophila''. Signs and symptoms include cough, shortness of breath, high fever, myalgia, muscle pains, and headach ...

appeared in the U.S. that year, he said it was a continuation of the swine flu outbreak, and that senators who opposed vaccination were suppressing the link as part of a "genocidal policy".

His campaign included a paid half-hour television address, which allowed him to air his views before a national audience, something that became a regular feature of his later campaigns. There were protests about this, and about the NCLC's involvement in public life generally. Writing in ''The Washington Post'', Stephen Rosenfeld said LaRouche's ideas belonged to the radical right, neo-Nazi fringe, and that his main interests lay in disruption and disinformation; Rosenfeld called the NCLC one of the "chief polluters" of political democracy. Rosenfeld argued that the press should be "chary" of offering them print or airtime: "A duplicitous violence-prone group with fascistic proclivities should not be presented to the public, unless there is reason to present it in those terms." LaRouche wrote in 1999 that this comment had "openly declared ... a policy of malicious lying" against him.

1977: Second marriage

LaRouche married again in 1977. His wife, Helga Zepp, was then a leading activist in the West German

West Germany was the common English name for the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) from its formation on 23 May 1949 until its reunification with East Germany on 3 October 1990. It is sometimes known as the Bonn Republic after its capital c ...

branch of the movement. She went on to work closely with LaRouche for the rest of her career, standing for election in Germany in 1980 for his ''Europäische Arbeiterpartei'' (European Workers Party), and founding the Schiller Institute in Germany in 1984.

1980s

National Democratic Policy Committee, "October Surprise" theory

From the autumn of 1979, the LaRouche movement conducted most of its U.S. electoral activities as the National Democratic Policy Committee (NDPC), a political action committee. The name drew complaints from the Democratic Party's Democratic National Committee

The Democratic National Committee (DNC) is the principal executive leadership board of the United States's Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party. According to the party charter, it has "general responsibility for the affairs of the ...

. Democratic Party leaders refused to recognize LaRouche as a party member, or to seat the few delegates he received in his seven primary campaigns as a Democrat. In its 2019 obituary of LaRouche, '' New York'' magazine reported that LaRouche's attempts to pose as a Democrat were originally an attempt at a spoiler operation to divide the opponents of Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan (February 6, 1911 – June 5, 2004) was an American politician and actor who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He was a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party a ...

.Bretton Woods system

The Bretton Woods system of monetary management established the rules for commercial relations among 44 countries, including the United States, Canada, Western European countries, and Australia, after the 1944 Bretton Woods Agreement until the ...

, including a gold-based national and world monetary system; fixed exchange rates; and abolishing the International Monetary Fund

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is a major financial agency of the United Nations, and an international financial institution funded by 191 member countries, with headquarters in Washington, D.C. It is regarded as the global lender of las ...

. He supported the replacement of the central bank

A central bank, reserve bank, national bank, or monetary authority is an institution that manages the monetary policy of a country or monetary union. In contrast to a commercial bank, a central bank possesses a monopoly on increasing the mo ...

system, including the U.S. Federal Reserve

The Federal Reserve System (often shortened to the Federal Reserve, or simply the Fed) is the central banking system of the United States. It was created on December 23, 1913, with the enactment of the Federal Reserve Act, after a series of ...

System, with a "national bank"; a war on drug trafficking and prosecution of banks involved in money laundering; building a tunnel under the Bering Strait; the building of nuclear power plants; and a crash program to build particle-beam weapons and lasers, including support for elements of the Strategic Defense Initiative

The Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) was a proposed missile defense system intended to protect the United States from attack by ballistic nuclear missiles. The program was announced in 1983, by President Ronald Reagan. Reagan called for a ...

(SDI). He opposed the Soviet Union and supported a military buildup to prepare for imminent war; supported the screening and quarantine of AIDS

The HIV, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a retrovirus that attacks the immune system. Without treatment, it can lead to a spectrum of conditions including acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). It is a Preventive healthcare, pr ...

patients; and opposed environmentalism, deregulation, outcome-based education, and abortion:

In December 1980, LaRouche and his followers started what came to be known as the " October Surprise" allegation,Iran hostage crisis

The Iran hostage crisis () began on November 4, 1979, when 66 Americans, including diplomats and other civilian personnel, were taken hostage at the Embassy of the United States in Tehran, with 52 of them being held until January 20, 1981. Th ...

to delay the release of 52 American hostages held in Iran, with the aim of helping Reagan win the 1980 United States presidential election

United States presidential election, Presidential elections were held in the United States on November 4, 1980. In a landslide victory, the Republican Party (United States), Republican ticket of former California governor Ronald Reagan and form ...

against Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (October 1, 1924December 29, 2024) was an American politician and humanitarian who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party ...

. The Iranians had agreed to this, according to the theory, in exchange for future weapons sales from the Reagan administration. The first publication of the story was in LaRouche's ''Executive Intelligence Review'' on December 2, 1980, followed by his ''New Solidarity'' on September 2, 1983, alleging that Henry Kissinger

Henry Alfred Kissinger (May 27, 1923 – November 29, 2023) was an American diplomat and political scientist who served as the 56th United States secretary of state from 1973 to 1977 and the 7th National Security Advisor (United States), natio ...

, one of LaRouche's regular targets, had met Iran's Ayatollah Beheshti in Paris, according to Iranian sources in Paris. The theory was later echoed by former Iranian President Abolhassan Banisadr and former Naval intelligence officer and National Security Council member Gary Sick.

1983: Move from New York to Loudoun County

''The Washington Post'' wrote that LaRouche and his wife moved in August 1983 from New York to a 13-room Georgian mansion on a 250-acre section of the Woodburn Estate, near Leesburg, Loudoun County

Loudoun County () is in the northern part of the Virginia, Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. In 2020, the census returned a population of 420,959, making it Virginia's third-most populous county. The county seat is Leesburg, Virgi ...

, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

. The property was owned at the time by a company registered in Switzerland. Companies associated with LaRouche continued to buy property in the area, including part of Leesburg's industrial park, purchased by LaRouche's Lafayette/Leesburg Ltd. Partnership to develop a printing plant and office complex.[

Neighbors said they saw LaRouche guards in camouflage clothes carrying semi-automatic weapons, and the ''Post'' wrote that the house had sandbag-buttressed guard posts nearby, along with metal spikes in the driveway and concrete barriers on the road. One of his aides said LaRouche was safer in Loudoun County: "The terrorist organizations which have targeted Mr. LaRouche do not have bases of operations in Virginia." LaRouche said his new home meant a shorter commute to Washington. A former associate said the move also meant his members would be more isolated from friends and family than they had been in New York.][Mintz, January 13, 1985]

. According to the ''Post'' in 2004, local people who opposed him for any reason were accused in LaRouche publications of being communists, homosexuals, drug pushers, and terrorists. He reportedly accused the Leesburg Garden Club of being a nest of Soviet sympathizers, and a local lawyer who opposed LaRouche on a zoning matter went into hiding after threatening phone calls and a death threat.[ In leaflets supporting his application of concealed weapons permits for his bodyguards in Leesburg, Virginia, he wrote:

Of LaRouche's paramilitary security force, armed with semi-automatic weapons, a spokesperson said that it was necessary because LaRouche was the subject of "assassination conspiracies".

]

1984: Schiller Institute, television spots, contact with Reagan administration

Helga Zepp-LaRouche founded the Schiller Institute in Germany in 1984. In the same year, LaRouche raised enough money to purchase 14 television spots, at $330,000 each, in which he called Walter Mondale

Walter Frederick "Fritz" Mondale (January 5, 1928April 19, 2021) was the 42nd vice president of the United States serving from 1977 to 1981 under President Jimmy Carter. He previously served as a U.S. senator from Minnesota from 1964 to 1976. ...

—the Democratic Party's presidential nominee—a Soviet agent of influence, triggering over 1,000 telephone complaints. On April 19, 1986, NBC's ''Saturday Night Live

''Saturday Night Live'' (''SNL'') is an American Late night television in the United States, late-night live television, live sketch comedy variety show created by Lorne Michaels and developed by Michaels and Dick Ebersol that airs on NBC. The ...

'' aired a sketch satirizing the ads, portraying the Queen of the United Kingdom and Henry Kissinger as drug dealers. LaRouche received 78,773 votes in the 1984 presidential election.

In 1984, media reports stated that LaRouche and his aides had met Reagan administration officials, including Norman Bailey, senior director of international economic affairs for the National Security Council (NSC), and Richard Morris, special assistant to William P. Clark, Jr. There were also reported contacts with the Drug Enforcement Administration

The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) is a Federal law enforcement in the United States, United States federal law enforcement agency under the U.S. Department of Justice tasked with combating illicit Illegal drug trade, drug trafficking a ...

, the Defense Intelligence Agency, and the CIA. The LaRouche campaign said the reporting was full of errors. In 1984 two Pentagon officials spoke at a LaRouche rally in Virginia; a Defense Department spokesman said the Pentagon viewed LaRouche's group as a "conservative group ... very supportive of the administration." White House spokesman Larry Speakes said the Administration was "glad to talk to" any American citizen who might have information. According to Bailey, the contacts were broken off when they became public. Three years later, LaRouche blamed his criminal indictment on the NSC, saying he had been in conflict with Oliver North

Oliver Laurence North (born October 7, 1943) is an American political commentator, television host, military historian, author, and retired United States Marine Corps lieutenant colonel.

A veteran of the Vietnam War, North was a National Sec ...

over LaRouche's opposition to the Nicaraguan Contras. According to a LaRouche publication, a court-ordered search of North's files produced a May 1986 telex from Iran–Contra defendant General Richard Secord, discussing the gathering of information to be used against LaRouche. According to King, LaRouche's ''Executive Intelligence Review'' was the first to report important details of the Iran–Contra affair, predicting that a major scandal was about to break months before mainstream media picked up on the story.

Strategic Defense Initiative

The LaRouche campaign supported Reagan's

The LaRouche campaign supported Reagan's Strategic Defense Initiative

The Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) was a proposed missile defense system intended to protect the United States from attack by ballistic nuclear missiles. The program was announced in 1983, by President Ronald Reagan. Reagan called for a ...

(SDI). Dennis King wrote that LaRouche had been speculating about space-based weaponry as early as 1975. He set up the Fusion Energy Foundation, which held conferences and tried to cultivate scientists, with some success. In 1979, FEF representatives attended a Moscow conference on laser fusion. LaRouche began to promote the use of lasers and related technologies for both military and civilian purposes, calling for a "revolution in machine tool

A machine tool is a machine for handling or machining metal or other rigid materials, usually by cutting, Boring (manufacturing), boring, grinding (abrasive cutting), grinding, shearing, or other forms of deformations. Machine tools employ some s ...

s."[Benedictine, Kirll, and Diunov, Michael]

"The Last Rosicrucian"

Terra-America, April 16, 2012

According to King, LaRouche's associates had for some years been in contact with members of the Reagan administration about LaRouche's space-based weapons ideas. LaRouche proposed the development of defensive beam technologies as a policy that was in the interest of both the U.S. and the Soviet Union, as the alternative to an arms race in offensive weapons and as a generator of spin-off economic benefits. Between February 1982 and February 1983, with the NSC's approval, LaRouche met with Soviet embassy representative Evgeny Shershnev to discuss the proposal. During this period, Soviet economists also began to study LaRouche's economic forecasting model. But after Reagan's public announcement of the SDI in March 1983, Soviet representatives broke off contact with LaRouche and his representatives.Edward Teller

Edward Teller (; January 15, 1908 – September 9, 2003) was a Hungarian and American Theoretical physics, theoretical physicist and chemical engineer who is known colloquially as "the father of the hydrogen bomb" and one of the creators of ...

, a proponent of SDI and X-ray lasers, told reporters in 1984 that he had been courted by LaRouche but had kept his distance. LaRouche began calling his plan the "LaRouche-Teller proposal," though they had never met. Teller said LaRouche was "a poorly informed man with fantastic conceptions."[.]

LaRouche later attributed the collapse of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union was formally dissolved as a sovereign state and subject of international law on 26 December 1991 by Declaration No. 142-N of the Soviet of the Republics of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union. Declaration No. 142-Н of ...

to its refusal to follow his advice to accept Reagan's offer to share the technology. Former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld reported in his 2011 memoir that at a 2001 dinner in Russia with leading officials, he was told by General Yuri Baluyevsky, then the second highest-ranking officer in the Russian military, that LaRouche was the brains behind SDI. Rumsfeld said he believed LaRouche had had no influence on the program, and surmised that Baluyevsky must have obtained the information off the Internet. In 2012 the former head of the Russian bureau of Interpol, General Vladimir Ovchinsky, also described LaRouche as the man who proposed the SDI.

1984: NBC lawsuit

In January 1984, NBC aired a news segment about LaRouche, and in March a "First Camera" report produced by Pat Lynch. The reports called LaRouche "the leader of a violence-prone, anti-Semitic cult that smeared its opponents and sued its critics", as Lynch wrote in 1985 in the ''Columbia Journalism Review

The ''Columbia Journalism Review'' (''CJR'') is a biannual magazine for professional journalists that has been published by the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism since 1961. Its original purpose was "to assess the performance ...

''. In interviews, former members of the movement gave details about their fundraising practices, and alleged that LaRouche had spoken about assassinating President Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (October 1, 1924December 29, 2024) was an American politician and humanitarian who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party ...

. The reports said an investigation by the Internal Revenue Service

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) is the revenue service for the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government, which is responsible for collecting Taxation in the United States, U.S. federal taxes and administerin ...

would lead to an indictment, and quoted Irwin Suall, the Anti-Defamation League's fact-finding director, who called LaRouche a "small-time Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

". After the broadcast, LaRouche members picketed NBC's office carrying signs saying "Lynch Pat Lynch," and the NBC switchboard said it received a death threat against her. Another NBC researcher said someone placed fliers around her parents' neighborhood saying she was running a call-girl ring from her parents' home. Lynch said LaRouche members began to impersonate her and her researchers in telephone calls, and called her "Fat Lynch" in their publications.

LaRouche filed a defamation suit against NBC and the ADL, arguing that the programs were the result of a deliberate campaign of defamation against him. The judge ruled that NBC need not reveal its sources, and LaRouche lost the case. NBC won a countersuit, the jury awarding the network $3 million in damages, later reduced to $258,459, for misuse of libel law, in what was called one of the more celebrated countersuits by a libel defendant. LaRouche failed to pay the damages, pleading poverty, which the judge described as "completely lacking in credibility." LaRouche said he had been unaware since 1973 who paid the rent on the estate, or for his food, lodging, clothing, transportation, bodyguards, and lawyers. The judge fined him for failing to answer. After the judge signed an order to allow discovery of LaRouche's personal finances, a cashier's check was delivered to the court to end the case. When LaRouche appealed, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals, rejecting his arguments, set forth a three-pronged test, later called the "LaRouche test," to decide when anonymous sources must be named in libel cases.

1985–1986: PANIC, LaRouche's AIDS initiative

LaRouche interpreted the AIDS pandemic as fulfillment of his 1973 prediction that an epidemic would strike humanity in the 1980s. According to Christopher Toumey, his subsequent campaign followed a familiar LaRouche pattern: challenging the scientific competence of government experts, and arguing that LaRouche had special scientific insights, and his own scientific associates were more competent than government scientists. LaRouche's view of AIDS agreed with orthodox medicine in that HIV caused AIDS, but differed from it in arguing that HIV spread like the cold virus or malaria, by way of casual contact and insect biteswhich, if true, would make HIV-positive people extremely dangerous. He advocated testing anyone working in schools, restaurants, or healthcare, and quarantining those who tested positive. Some of LaRouche's views on AIDS were developed by John Seale, a British venereological physician who proposed that AIDS was created in a Soviet laboratory. Seale's highly speculative writings were published in three prestigious medical journals, lending these ideas some appearance of being hard science.World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a list of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations which coordinates responses to international public health issues and emergencies. It is headquartered in Gen ...

and Centers for Disease Control

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is the national public health agency of the United States. It is a United States federal agency under the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), and is headquartered in Atlanta, ...

, were accused of "viciously lying to the world," and of following an agenda of genocide and euthanasia.University of California at Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California), is a public land-grant research university in Berkeley, California, United States. Founded in 1868 and named after the Anglo-Irish philosopher George Berkele ...

, the proposal would have required that 300,000 people in the area with HIV or AIDS be reported to public health authorities; might have removed over 100,000 of them from their jobs in schools, restaurants and agriculture; and would have forced 47,000 children to stay away from school.[Kirp, David L]

"LaRouche Turns To AIDS Politics"

, ''The New York Times'', September 11, 1986.

The proposal was opposed by leading scientists and local health officials as based on inaccurate scientific information and, as the public health schools put it, running "counter to all public health principles." It was defeated, reintroduced two years later, and defeated again, with two million votes in favor the first time, and 1.7 million the second. AIDS became a leading plank in LaRouche's platform during his 1988 presidential campaign.

1986: Electoral success in Illinois; press conference allegations

In March 1986, Mark Fairchild and Janice HartLaRouche National Democratic Policy Committee candidateswon the Democratic primary for statewide offices in Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. It borders on Lake Michigan to its northeast, the Mississippi River to its west, and the Wabash River, Wabash and Ohio River, Ohio rivers to its ...

, gaining national attention for LaRouche. The Democratic gubernatorial candidate, Adlai Stevenson III, withdrew his nomination rather than run on the same slate as LaRouche members, and told reporters the party was "exploring every legal remedy to purge these bizarre and dangerous extremists from the Democratic ticket." A spokesman for the Democratic National Committee said it would have to do a better job of communicating to the electorate that LaRouche's National Democratic Policy Committee was unrelated to the Democratic Party.["Win by LaRouche candidate shocks national Democrats"](_blank)

, Associated Press, March 20, 1986. ''The New York Times'' wrote that Democratic Party officials were trying to identify LaRouche candidates in order to alert voters, and asked the LaRouche organization to release a full list of its candidates.

A month later, LaRouche held a press conference to accuse the Soviet government, British government, drug dealers, international bankers, and journalists of being involved in multiple conspiracies. Flanked by bodyguards, he said: "If Abe Lincoln were alive, he'd probably be standing up here with me today," and that there was no criticism of him that did not originate "with the drug lobby or the Soviet operation ..." He said he had been in danger from Soviet assassins for over 13 years, and had to live in safe houses. He refused to answer a question from an NBC reporter, saying "How can I talk with a drug pusher like you?" He called the leadership of the United States "idiotic" and "berserk," and its foreign policy "criminal or insane." He warned of the imminent collapse of the banking system and accused banks of laundering drug money. Asked about the movement's finances, he said "I don't know. ... I'm not responsible, I'm not involved in that."

1986–1988: Raids and criminal convictions

In October 1986, hundreds of state and federal officers raided LaRouche offices in Virginia and Massachusetts. A federal grand jury indicted LaRouche and twelve of his associates on credit card fraud and obstruction of justice. The charges stated that they had attempted to defraud people of millions of dollars, including several elderly people, by borrowing money they did not intend to repay. LaRouche disputed the charges, alleging that they were politically motivated.

," Associated Press, January 27, 1989.

* Mintz, John

, ''The Washington Post'', July 3, 1987.

* Also see Mintz, John. [https://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/washingtonpost/access/73846043.html?dids=73846043:73846043&FMT=ABS&FMTS=ABS:FT&type=current&date=Sep+20%2C+1987&author=John+Mintz&pub=The+Washington+Post+%28pre-1997+Fulltext%29&desc=Inside+the+Weird+World+of+Lyndon+LaRouche&pqatl=google "Inside the Weird World of Lyndon LaRouche"] , ''The Washington Post'', September 20, 1987.

* .mail fraud

Mail fraud and wire fraud are terms used in the United States to describe the use of a physical (e.g., the U.S. Postal Service) or electronic (e.g., a phone, a telegram, a fax, or the Internet) mail system to defraud another, and are U.S. fede ...

involving more than $30 million in defaulted loans; eleven counts of actual mail fraud involving $294,000 in defaulted loans; and a single count of conspiring to defraud the U.S. Internal Revenue Service. He was sentenced to 15 years in federal prison, but was released on parole after serving five years on January 26, 1994.[

The trial judge called LaRouche's claim of a political vendetta "arrant nonsense", and said "the idea that this organization is a sufficient threat to anything that would warrant the government bringing a prosecution to silence them just defies human experience."

Defense lawyers filed unsuccessful appeals that challenged the conduct of the grand jury, the contempt fines, the execution of the search warrants, and various trial procedures. At least ten appeals were heard by the United States Court of Appeals, and three were heard by the U.S. Supreme Court.

Former ]Attorney General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general (: attorneys general) or attorney-general (AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have executive responsibility for law enf ...

Ramsey Clark joined the defense team for two appeals, writing that the case involved "a broader range of deliberate and systematic misconduct and abuse of power over a longer period of time in an effort to destroy a political movement and leader, than any other federal prosecution in my time or to my knowledge."Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

opposed him, because he had invented the Strategic Defense Initiative

The Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) was a proposed missile defense system intended to protect the United States from attack by ballistic nuclear missiles. The program was announced in 1983, by President Ronald Reagan. Reagan called for a ...

. "The Soviet government hated me for it. Gorbachev also hated my guts and called for my assassination and imprisonment and so forth." He asserted that he had survived these threats, because he had been protected by unnamed U.S. government officials. "Even when they don't like me, they consider me a national asset, and they don't like to have their national assets killed."

LaRouche received 25,562 votes in the 1988 presidential election.

1989: Musical interests and Verdi tuning initiative

LaRouche had an interest in classical music up to the period of Brahms. A motto of LaRouche's European Workers' Party is "Think like Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven (baptised 17 December 177026 March 1827) was a German composer and pianist. He is one of the most revered figures in the history of Western music; his works rank among the most performed of the classical music repertoire ...

"; movement offices typically include a piano and posters of German composers, and members are known for their choral singing at protest events and for using satirical lyrics tailored to their targets. LaRouche abhorred popular music; he said in 1980, "Rock was not an accidental thing. This was done by people who set out in a deliberate way to subvert the United States. It was done by British intelligence," and wrote that the Beatles

The Beatles were an English Rock music, rock band formed in Liverpool in 1960. The core lineup of the band comprised John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr. They are widely regarded as the Cultural impact of the Beatle ...

were "a product shaped according to British Psychological Warfare Division specifications."

LaRouche movement members have protested at performances of Richard Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, essayist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most o ...

's operas, denouncing Wagner as an anti-Semite who found favor with the Nazis, and called a conductor "satanic" because he played contemporary music.

In 1989, LaRouche advocated that classical orchestras should use a concert pitch based on A above middle C (A4) tuned to 432 Hz, which the Schiller Institute called the "Verdi pitch", a pitch that Verdi had suggested as optimal, though he also composed and conducted in other pitches such as the French official ''diapason normal'' of 435 Hz, including his ''Requiem'' in 1874.Joan Sutherland

Dame Joan Alston Sutherland, (7 November 1926 – 10 October 2010) was an Australian dramatic coloratura soprano known for her contribution to the renaissance of the bel canto repertoire from the late 1950s to the 1980s.

She possessed a voice ...

, Plácido Domingo

José Plácido Domingo Embil (born 21 January 1941) is a Spanish opera singer, conductor, and arts administrator. He has recorded over a hundred complete operas and is well known for his versatility, regularly performing in Italian, French, ...

, and Luciano Pavarotti

Luciano Pavarotti (, , ; 12 October 19356 September 2007) was an Italian operatic tenor who during the late part of his career crossed over into popular music, eventually becoming one of the most acclaimed tenors of all time. He made numerou ...

, who according to ''Opera Fanatic'' may not have been aware of LaRouche's politics. A spokesman for Domingo said Domingo had simply signed a questionnaire, had not been aware of its origins, and would not agree with LaRouche's politics. Renata Tebaldi and Piero Cappuccilli, who were running for the European Parliament on LaRouche's "Patriots for Italy" platform, attended Schiller Institute conferences as featured speakers. The discussions led to debates in the Italian parliament about reinstating "Verdi" legislation. LaRouche gave an interview to National Public Radio

National Public Radio (NPR) is an American public broadcasting organization headquartered in Washington, D.C., with its NPR West headquarters in Culver City, California. It serves as a national Radio syndication, syndicator to a network of more ...

on the initiative from prison. The initiative was opposed by the editor of ''Opera Fanatic'', Stefan Zucker, who objected to the establishment of a "pitch police," and argued that LaRouche was using the issue to gain credibility.

1990s

Imprisonment, release on parole, attempts at exoneration, visits to Russia

LaRouche began his sentence in 1989, serving it at the Federal Medical Center in Rochester, Minnesota

Rochester is a city in Olmsted County, Minnesota, United States, and its county seat. It is located along rolling bluffs on the Zumbro River's south fork in Southeast Minnesota. At the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the city had a popul ...

. From there he ran for Congress in 1990, seeking to represent the 10th District of Virginia, but he received less than one percent of the vote. He ran for president again in 1992 with James Bevel as his running mate, a civil rights activist who had represented the LaRouche movement in its pursuit of the Franklin child prostitution ring allegations. It was only the second-ever campaign for president from prison. He received 26,334 votes, standing again as the "Economic Recovery" party. For a time he shared a cell with televangelist Jim Bakker. Bakker later wrote of his astonishment at LaRouche's detailed knowledge of the Bible. According to Bakker, LaRouche received a daily intelligence report by mail, and at times had information about news events days before they happened. Bakker also wrote that LaRouche believed their cell was bugged. In Bakker's view, "to say LaRouche was a little paranoid would be like saying that the ''Titanic

RMS ''Titanic'' was a British ocean liner that sank in the early hours of 15 April 1912 as a result of striking an iceberg on her maiden voyage from Southampton, England, to New York City, United States. Of the estimated 2,224 passengers a ...

'' had a little leak."