Llewelyn Robert Owen Storey on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Llewelyn Robert Owen Storey (born 5 November 1927; also known as L. R. O. Storey, L. R. Owen Storey, and Owen Storey) is a British

physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe.

Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate ca ...

and electrical engineer

Electrical engineering is an engineering discipline concerned with the study, design, and application of equipment, devices, and systems which use electricity, electronics, and electromagnetism. It emerged as an identifiable occupation in the ...

who has worked and lived most of his adult life in France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan ar ...

. He is known for his research on the Earth's atmosphere

The atmosphere of Earth is the layer of gases, known collectively as air, retained by Earth's gravity that surrounds the planet and forms its planetary atmosphere. The atmosphere of Earth protects life on Earth by creating pressure allowing f ...

, especially whistlers

Whistler may refer to:

* Someone who whistles

Places

Canada

* Whistler, British Columbia, a resort town

** Whistler railway station

** Whistler Secondary School

* Whistler Blackcomb, a ski resort in British Columbia

* Whistler Mountain, British ...

—very low frequency

Very low frequency or VLF is the ITU designation for radio frequencies (RF) in the range of 3–30 kHz, corresponding to wavelengths from 100 to 10 km, respectively. The band is also known as the myriameter band or myriameter wave ...

(VLF) radio waves caused by lightning

Lightning is a naturally occurring electrostatic discharge during which two electrically charged regions, both in the atmosphere or with one on the ground, temporarily neutralize themselves, causing the instantaneous release of an average ...

strikes—and the plasmasphere

The plasmasphere, or inner magnetosphere, is a region of the Earth's magnetosphere consisting of low-energy (cool) plasma. It is located above the ionosphere. The outer boundary of the plasmasphere is known as the plasmapause, which is defined ...

. He was the first person to prove whistlers are caused by lightning strikes and to deduce the plasmasphere's existence. He was heavily involved in designing scientific instruments for FR-1

The Ryan FR Fireball was an American mixed-power (Reciprocating engine, piston and jet aircraft, jet-powered) fighter aircraft designed by Ryan Aeronautical for the United States Navy during World War II. It was the Navy's first aircraft with a ...

, a 1965 French-American satellite, and subsequent studies and experiments using data FR-1 collected.

Early life

Storey was born on 5 November 1927 inCrowborough

Crowborough is a town and civil parish in East Sussex, England, in the Weald at the edge of Ashdown Forest in the High Weald Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, 7 miles (11 km) south-west of Royal Tunbridge Wells and 33 mile ...

, England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

, United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

. He received a Bachelor of Arts degree in natural sciences in 1948 and a PhD in physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which rel ...

in 1953, both from the University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

. He became interested in whistlers

Whistler may refer to:

* Someone who whistles

Places

Canada

* Whistler, British Columbia, a resort town

** Whistler railway station

** Whistler Secondary School

* Whistler Blackcomb, a ski resort in British Columbia

* Whistler Mountain, British ...

during his time as a graduate student. In fact, Storey in his 1953 PhD dissertation was the first person to realize the propagation of VLF radio waves after lightning strikes causes whistlers. Originally published by Stanford University Press, Stanford, California (1965). Around the same time, Storey had posited the existence of whistlers meant plasma

Plasma or plasm may refer to:

Science

* Plasma (physics), one of the four fundamental states of matter

* Plasma (mineral), a green translucent silica mineral

* Quark–gluon plasma, a state of matter in quantum chromodynamics

Biology

* Blood plas ...

was present in Earth's atmosphere, and that it moved radio waves in the same direction as Earth's magnetic field

Earth's magnetic field, also known as the geomagnetic field, is the magnetic field that extends from Earth's interior out into space, where it interacts with the solar wind, a stream of charged particles emanating from the Sun. The magneti ...

lines. From this he deduced but was unable to conclusively prove the existence of the plasmasphere

The plasmasphere, or inner magnetosphere, is a region of the Earth's magnetosphere consisting of low-energy (cool) plasma. It is located above the ionosphere. The outer boundary of the plasmasphere is known as the plasmapause, which is defined ...

, a region of cold plasma extending from the upper ionosphere far into the magnetosphere

In astronomy and planetary science, a magnetosphere is a region of space surrounding an astronomical object in which charged particles are affected by that object's magnetic field. It is created by a celestial body with an active interior dynamo ...

.

After obtaining his doctorate, Storey worked in England, and then Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tota ...

and the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., federal district, five ma ...

, before becoming an employee of the French National Centre for Scientific Research

The French National Centre for Scientific Research (french: link=no, Centre national de la recherche scientifique, CNRS) is the French state research organisation and is the largest fundamental science agency in Europe.

In 2016, it employed 31,63 ...

(''Centre national de la recherche scientifique''; CNRS) in 1959.

Career and research

FR-1: whistlers and the plasmasphere

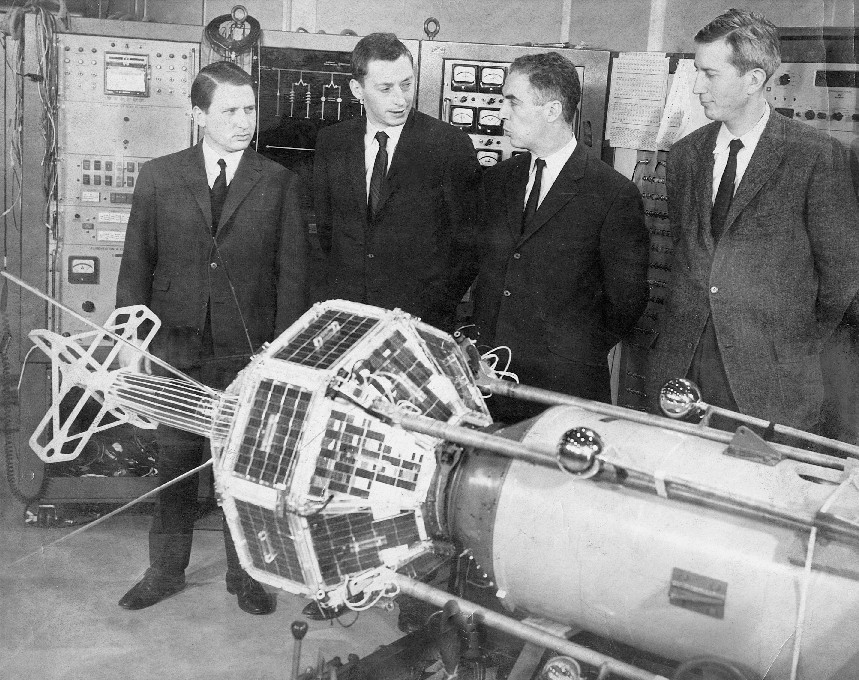

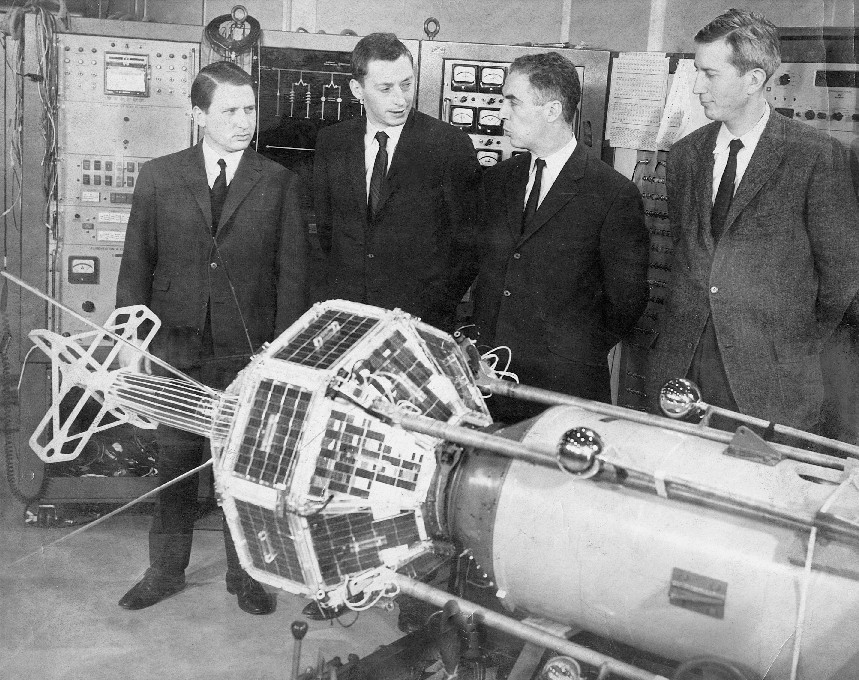

In 1963 Storey became scientific director of the joint French-American FR-1 satellite program. He designed the satellite's scientific instruments, working in concert with Dr. Robert W. Rochelle ofNASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil space program, aeronautics research, and space research.

NASA was established in 1958, succeedi ...

's Goddard Space Flight Center

The Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC) is a major NASA space research laboratory located approximately northeast of Washington, D.C. in Greenbelt, Maryland, United States. Established on May 1, 1959 as NASA's first space flight center, GSFC emp ...

(GSFC).

FR-1 was launched on 6 December 1965. The mission objective was to study the composition and structure of the ionosphere, plasmasphere

The plasmasphere, or inner magnetosphere, is a region of the Earth's magnetosphere consisting of low-energy (cool) plasma. It is located above the ionosphere. The outer boundary of the plasmasphere is known as the plasmapause, which is defined ...

, and magnetosphere

In astronomy and planetary science, a magnetosphere is a region of space surrounding an astronomical object in which charged particles are affected by that object's magnetic field. It is created by a celestial body with an active interior dynamo ...

by measuring the propagation of VLF waves and the local electron density

In quantum chemistry, electron density or electronic density is the measure of the probability of an electron being present at an infinitesimal element of space surrounding any given point. It is a scalar quantity depending upon three spatial ...

of plasma

Plasma or plasm may refer to:

Science

* Plasma (physics), one of the four fundamental states of matter

* Plasma (mineral), a green translucent silica mineral

* Quark–gluon plasma, a state of matter in quantum chromodynamics

Biology

* Blood plas ...

in those atmospheric layers. For the VLF wave experiments, stations located on land in Seine-Port

Seine-Port () is a commune in the Seine-et-Marne department in the Île-de-France region in north-central France.

Demographics

Inhabitants of Seine-Port are called ''Saint-Portais''.

See also

*Communes of the Seine-et-Marne department

The f ...

, France (at the Sainte-Assise transmitter

The Sainte-Assise transmitter (french: Émetteur de Sainte-Assise) is a very low frequency (VLF) radio transmitter and military installation located on the grounds of the in the communes of Seine-Port, Boissise-la-Bertrand, and Cesson in the ...

), and Balboa, Panama

Panama ( , ; es, link=no, Panamá ), officially the Republic of Panama ( es, República de Panamá), is a transcontinental country spanning the southern part of North America and the northern part of South America. It is bordered by Co ...

, transmitted signals at 16.8 kHz and 24 kHz, respectively, while the satellite's magnetic and electric sensors orbiting about away analyzed the magnetic field of the received wave.

Principal researchers who studied both the VLF and electron density data collected by FR-1 included Storey, as well as the French scientists Dr. M. P. Aubry of CNET and Dr. C. Renard. Aubry published his results in 1968, while Storey published initial findings in 1967 before the mission's ultimate end. Northern Irish physicist James Sayers

James Sayers (or Sayer) (1748 – April 20, 1823) was an English caricaturist . Many of his works are described in the Catalogue of Political and Personal Satires Preserved in the Department of Prints and Drawings in the British Museum which h ...

—an electron density expert—was also involved in the electron density experiments.

Data collected by FR-1 helped prove the existence of the plasmasphere. Prior to their work on FR-1, both Aubry and Storey had studied whistlers. From earlier whistler research Storey deduced the existence of the plasmasphere but was unable to conclusively prove it. In 1963 American scientist Don Carpenter

Don Carpenter (March 16, 1931 – July 27, 1995) was an American writer, best known as the author of ''Hard Rain Falling''. He wrote numerous novels, novellas, short stories and screenplays over the course of a 22-year career that took him from ...

and Soviet astronomer

An astronomer is a scientist in the field of astronomy who focuses their studies on a specific question or field outside the scope of Earth. They observe astronomical objects such as stars, planets, moons, comets and galaxies – in either o ...

Konstantin Gringauz

The first name Konstantin () is a derivation from the Latin name '' Constantinus'' ( Constantine) in some European languages, such as Russian and German. As a Christian given name, it refers to the memory of the Roman emperor Constantine the G ...

—independently of each other, and the latter using data from the ''Luna 2

''Luna 2'' ( rus, Луна 2}), originally named the Second Soviet Cosmic Rocket and nicknamed Lunik 2 in contemporaneous media, was the sixth of the Soviet Union's Luna programme spacecraft launched to the Moon, E-1 No.7. It was the first spac ...

'' spacecraft—experimentally proved the plasmasphere and plasmapause

The plasmasphere, or inner magnetosphere, is a region of the Earth's magnetosphere consisting of low-energy (cool) plasma. It is located above the ionosphere. The outer boundary of the plasmasphere is known as the plasmapause, which is defined ...

's existence, building on Storey's thinking. Aubry and Storey's post-1965 studies of FR-1 VLF and electron density data further corroborated this: VLF waves in the ionosphere occasionally passed through a thin layer of plasma into the magnetosphere, normal Normal(s) or The Normal(s) may refer to:

Film and television

* ''Normal'' (2003 film), starring Jessica Lange and Tom Wilkinson

* ''Normal'' (2007 film), starring Carrie-Anne Moss, Kevin Zegers, Callum Keith Rennie, and Andrew Airlie

* ''Norma ...

to the direction of Earth's magnetic field

Earth's magnetic field, also known as the geomagnetic field, is the magnetic field that extends from Earth's interior out into space, where it interacts with the solar wind, a stream of charged particles emanating from the Sun. The magneti ...

.

Later career

After his work on FR-1, Storey headed his own research group which continued studying VLF waves using data gathered the satellite. It transferred to a laboratory inOrléans

Orléans (;"Orleans"

(US) and Paris Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. ...

location in the early 1970s. This group's research focused on developing methods for measuring the properties of space plasmas using (US) and Paris Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. ...

dipole antenna

In radio and telecommunications a dipole antenna or doublet is the simplest and most widely used class of antenna. The dipole is any one of a class of antennas producing a radiation pattern approximating that of an elementary electric dipole w ...

s, and wave distribution function

In physics, mathematics, and related fields, a wave is a propagating dynamic disturbance (change from equilibrium) of one or more quantities. Waves can be periodic, in which case those quantities oscillate repeatedly about an equilibrium (r ...

(WDF) analysis. For the plasma measurement research Storey and his group collaborated with West German

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 O ...

and Swedish

Swedish or ' may refer to:

Anything from or related to Sweden, a country in Northern Europe. Or, specifically:

* Swedish language, a North Germanic language spoken primarily in Sweden and Finland

** Swedish alphabet, the official alphabet used b ...

programs during the International Magnetospheric Study The International Magnetospheric Study (IMS) was proposed in 1970 as a concerted effort to acquire coordinated ground-based, balloon, rocket, and satellite data needed to improve our understanding of the behavior of earth's plasma environment.

P ...

of 1976 to 1979, allowing them to carry out further experiments on rocket

A rocket (from it, rocchetto, , bobbin/spool) is a vehicle that uses jet propulsion to accelerate without using the surrounding air. A rocket engine produces thrust by reaction to exhaust expelled at high speed. Rocket engines work entire ...

s.

In 1983 Storey joined the research faculty of Stanford University's Electrical Engineering Department. From 1987 to 1989 he served as a senior visiting scientist at NASA Headquarters

NASA Headquarters, officially known as Mary W. Jackson NASA Headquarters or NASA HQ and formerly named Two Independence Square, is a low-rise office building in the two-building Independence Square complex at 300 E Street SW in Washington, D.C. ...

in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, and then as a WDF analysis software developer at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center.

Storey retired in 1992. In 1997 he received the IEEE Heinrich Hertz Medal The IEEE Heinrich Hertz Medal was a science award presented by the IEEE for outstanding achievements in the field of electromagnetic waves. The medal was named in honour of German physicist Heinrich Hertz, and was first proposed in 1986 by IEEE Regi ...

for his lifelong research on whistlers.

Personal life

Storey is a member of theAmerican Geophysical Union

The American Geophysical Union (AGU) is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization of Earth, atmospheric, ocean, hydrologic, space, and planetary scientists and enthusiasts that according to their website includes 130,000 people (not members). AGU's ...

. He and his wife live in southern France

Southern France, also known as the South of France or colloquially in French as , is a defined geographical area consisting of the regions of France that border the Atlantic Ocean south of the Marais Poitevin,Louis Papy, ''Le midi atlantique'', A ...

; they have three children together.

See also

*French space program

The French space program includes both civil and military spaceflight activities. It is the third oldest national space program in the world, after the Soviet (now Russian) and American space programs, and the largest space program in Europe.

B ...

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Storey, Llewelyn Robert Owen 1927 births British physicists British electrical engineers British expatriates in the United States British expatriates in Canada British expatriates in France Living people