Laws on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Law is a set of rules that are created and are

Law is a set of rules that are created and are

, 410">Dworkin, ''

Definitions of law often raise the question of the extent to which law incorporates morality.

Definitions of law often raise the question of the extent to which law incorporates morality.

John Austin

Later in the 20th century,

Later in the 20th century,

, 410" /> that requires judges to find the best fitting and most just solution to a legal dispute, given their constitutional traditions.  Law is a set of rules that are created and are

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable

An unenforceable contract or transaction is one that is valid but one the court will not enforce. Unenforceable is usually used in contradiction to void (or ''void ab initio'') and voidable. If the parties perform the agreement, it will be valid ...

by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been variously described as a science

Science is a systematic endeavor that Scientific method, builds and organizes knowledge in the form of Testability, testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earli ...

and as the art of justice. State-enforced laws can be made by a group legislature

A legislature is an deliberative assembly, assembly with the authority to make laws for a Polity, political entity such as a Sovereign state, country or city. They are often contrasted with the Executive (government), executive and Judiciary, ...

or by a single legislator, resulting in statutes; by the executive through decree

A decree is a legal proclamation, usually issued by a head of state (such as the president of a republic or a monarch), according to certain procedures (usually established in a constitution). It has the force of law. The particular term used f ...

s and regulation

Regulation is the management of complex systems according to a set of rules and trends. In systems theory, these types of rules exist in various fields of biology

Biology is the scientific study of life. It is a natural science with a ...

s; or established by judges through precedent

A precedent is a principle or rule established in a previous legal case that is either binding on or persuasive for a court or other tribunal when deciding subsequent cases with similar issues or facts. Common-law legal systems place great v ...

, usually in common law

In law, common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law created by judges and similar quasi-judicial tribunals by virtue of being stated in written opinions."The common law is not a brooding omniprese ...

jurisdictions. Private individuals may create legally binding contract

A contract is a legally enforceable agreement between two or more parties that creates, defines, and governs mutual rights and obligations between them. A contract typically involves the transfer of goods, services, money, or a promise to ...

s, including arbitration agreements that adopt alternative ways of resolving disputes to standard court litigation. The creation of laws themselves may be influenced by a constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princip ...

, written or tacit, and the rights

Rights are legal, social, or ethical principles of freedom or entitlement; that is, rights are the fundamental normative rules about what is allowed of people or owed to people according to some legal system, social convention, or ethical th ...

encoded therein. The law shapes politics

Politics (from , ) is the set of activities that are associated with making decisions in groups, or other forms of power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of resources or status. The branch of social science that stud ...

, economics

Economics () is the social science that studies the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and interactions of economic agents and how economies work. Microeconomics analy ...

, history

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the History of writing#Inventions of writing, invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbr ...

and society

A society is a Social group, group of individuals involved in persistent Social relation, social interaction, or a large social group sharing the same spatial or social territory, typically subject to the same Politics, political authority an ...

in various ways and serves as a mediator of relations between people.

Legal systems vary between jurisdictions

Jurisdiction (from Latin 'law' + 'declaration') is the legal term for the legal authority granted to a legal entity to enact justice. In federations like the United States, areas of jurisdiction apply to local, state, and federal levels.

Juri ...

, with their differences analysed in comparative law

Comparative law is the study of differences and similarities between the law ( legal systems) of different countries. More specifically, it involves the study of the different legal "systems" (or "families") in existence in the world, including t ...

. In civil law

Civil law may refer to:

* Civil law (common law), the part of law that concerns private citizens and legal persons

* Civil law (legal system), or continental law, a legal system originating in continental Europe and based on Roman law

** Private la ...

jurisdictions, a legislature or other central body codifies and consolidates the law. In common law

In law, common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law created by judges and similar quasi-judicial tribunals by virtue of being stated in written opinions."The common law is not a brooding omniprese ...

systems, judges may make binding case law through precedent

A precedent is a principle or rule established in a previous legal case that is either binding on or persuasive for a court or other tribunal when deciding subsequent cases with similar issues or facts. Common-law legal systems place great v ...

, although on occasion this may be overturned by a higher court or the legislature. Historically, religious law

Religious law includes ethical and moral codes taught by religious traditions. Different religious systems hold sacred law in a greater or lesser degree of importance to their belief systems, with some being explicitly antinomian whereas other ...

has influenced secular matters and is, as of the 21st century, still in use in some religious communities. Sharia law

Sharia (; ar, شريعة, sharīʿa ) is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition. It is derived from the religious precepts of Islam and is based on the sacred scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran and the ...

based on Islamic principles is used as the primary legal system in several countries, including Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkm ...

and Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in Western Asia. It covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula, and has a land area of about , making it the List of Asian countries by area, fifth-largest country in Asia ...

.

The scope of law can be divided into two domains. Public law

Public law is the part of law that governs relations between legal persons and a government, between different institutions within a State (polity), state, between Separation of powers, different branches of governments, as well as relationship ...

concerns government and society, including constitutional law

Constitutional law is a body of law which defines the role, powers, and structure of different entities within a state, namely, the executive, the parliament or legislature, and the judiciary; as well as the basic rights of citizens and, in fed ...

, administrative law

Administrative law is the division of law that governs the activities of executive branch agencies of government. Administrative law concerns executive branch rule making (executive branch rules are generally referred to as " regulations"), ...

, and criminal law. Private law deals with legal disputes between individuals and/or organisations in areas such as contracts

A contract is a legally enforceable agreement between two or more parties that creates, defines, and governs mutual rights and obligations between them. A contract typically involves the transfer of goods, services, money, or a promise to ...

, property

Property is a system of rights that gives people legal control of valuable things, and also refers to the valuable things themselves. Depending on the nature of the property, an owner of property may have the right to consume, alter, share, r ...

, torts

A tort is a civil wrong that causes a claimant to suffer loss or harm, resulting in legal liability for the person who commits the tortious act. Tort law can be contrasted with criminal law, which deals with criminal wrongs that are punishabl ...

/delicts

Delict (from Latin ''dēlictum'', past participle of ''dēlinquere'' ‘to be at fault, offend’) is a term in civil and mixed law jurisdictions whose exact meaning varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction but is always centered on the notion of ...

and commercial law

Commercial law, also known as mercantile law or trade law, is the body of law that applies to the rights, relations, and conduct of persons and business engaged in commerce, merchandising, trade, and sales. It is often considered to be a bra ...

. This distinction is stronger in civil law

Civil law may refer to:

* Civil law (common law), the part of law that concerns private citizens and legal persons

* Civil law (legal system), or continental law, a legal system originating in continental Europe and based on Roman law

** Private la ...

countries, particularly those with a separate system of administrative courts

Administration may refer to:

Management of organizations

* Management, the act of directing people towards accomplishing a goal

** Administrative Assistant, traditionally known as a Secretary, or also known as an administrative officer, adminis ...

; by contrast, the public-private law divide is less pronounced in common law

In law, common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law created by judges and similar quasi-judicial tribunals by virtue of being stated in written opinions."The common law is not a brooding omniprese ...

jurisdictions.

Law provides a source of scholarly inquiry into legal history

Legal history or the history of law is the study of how law has Sociocultural evolution, evolved and why it has changed. Legal history is closely connected to the development of civilisations and operates in the wider context of social history. C ...

, philosophy, economic analysis

Economics () is the social science that studies the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and interactions of economic agents and how economies work. Microeconomics analyze ...

and sociology

Sociology is a social science that focuses on society, human social behavior, patterns of social relationships, social interaction, and aspects of culture associated with everyday life. It uses various methods of empirical investigation and ...

. Law also raises important and complex issues concerning equality, fairness, and justice

Justice, in its broadest sense, is the principle that people receive that which they deserve, with the interpretation of what then constitutes "deserving" being impacted upon by numerous fields, with many differing viewpoints and perspective ...

.

Philosophy of law

The philosophy of law is commonly known as jurisprudence. Normative jurisprudence asks "what should law be?", while analytic jurisprudence asks "what is law?"Analytical jurisprudence

There have been several attempts to produce "a universally acceptable definition of law". In 1972, Baron Hampstead suggested that no such definition could be produced.Dennis Lloyd, Baron Lloyd of Hampstead

Dennis Lloyd, Baron Lloyd of Hampstead, QC (22 October 1915 – 31 December 1992) was a British jurist, and was created a life peer on 14 May 1965 as Baron Lloyd of Hampstead, ''of Hampstead in the London Borough of Camden''.

He was appointed ...

. ''Introduction to Jurisprudence''. Third Edition. Stevens & Sons. London. 1972. Second Impression. 1975. p. 39. McCoubrey and White said that the question "what is law?" has no simple answer. Glanville Williams

Glanville Llewelyn Williams (15 February 1911 – 10 April 1997) was a Welsh legal scholar who was the Rouse Ball Professor of English Law at the University of Cambridge from 1968 to 1978 and the Quain Professor of Jurisprudence at University ...

said that the meaning of the word "law" depends on the context in which that word is used. He said that, for example, "early customary law

A legal custom is the established pattern of behavior that can be objectively verified within a particular social setting. A claim can be carried out in defense of "what has always been done and accepted by law".

Customary law (also, consuetudina ...

" and "municipal law

Municipal law is the national, domestic, or internal law of a sovereign state and is defined in opposition to international law. Municipal law includes many levels of law: not only national law but also state, provincial, territorial, regional ...

" were contexts where the word "law" had two different and irreconcilable meanings. Thurman Arnold

Thurman Wesley Arnold (June 2, 1891 – November 7, 1969) was an American lawyer best known for his trust-busting campaign as Assistant Attorney General in charge of the Antitrust Division in President Franklin D. Roosevelt's Department of Ju ...

said that it is obvious that it is impossible to define the word "law" and that it is also equally obvious that the struggle to define that word should not ever be abandoned. It is possible to take the view that there is no need to define the word "law" (e.g. "let's forget about generalities and get down to cases").

One definition is that law is a system of rules and guidelines which are enforced through social institutions to govern behaviour. In ''The Concept of Law

''The Concept of Law'' is a 1961 book by the legal philosopher H. L. A. Hart and his most famous work. ''The Concept of Law'' presents Hart's theory of legal positivism—the view that laws are rules made by humans and that there is ...

,'' H.L.A Hart argued that law is a "system of rules"; John Austin John Austin may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* John P. Austin (1906–1997), American set decorator

* Johnny Austin (1910–1983), American musician

*John Austin (author) (fl. 1940s), British novelist

Military

*John Austin (soldier) (1801� ...

said law was "the command of a sovereign, backed by the threat of a sanction"; Ronald Dworkin

Ronald Myles Dworkin (; December 11, 1931 – February 14, 2013) was an American philosopher, jurist, and scholar of United States constitutional law. At the time of his death, he was Frank Henry Sommer Professor of Law and Philosophy at New Y ...

describes law as an "interpretive concept" to achieve justice

Justice, in its broadest sense, is the principle that people receive that which they deserve, with the interpretation of what then constitutes "deserving" being impacted upon by numerous fields, with many differing viewpoints and perspective ...

in his text titled ''Law's Empire

''Law's Empire'' is a 1986 text in legal philosophy by Ronald Dworkin, in which the author continues his criticism of the philosophy of legal positivism as promoted by H.L.A. Hart during the middle to late 20th century. The book introduces Dwork ...

'';Law's Empire

''Law's Empire'' is a 1986 text in legal philosophy by Ronald Dworkin, in which the author continues his criticism of the philosophy of legal positivism as promoted by H.L.A. Hart during the middle to late 20th century. The book introduces Dwork ...Law's Empire

''Law's Empire'' is a 1986 text in legal philosophy by Ronald Dworkin, in which the author continues his criticism of the philosophy of legal positivism as promoted by H.L.A. Hart during the middle to late 20th century. The book introduces Dwork ...

'', 410 and Joseph Raz

Joseph Raz (; he, יוסף רז; born Zaltsman; 21 March 19392 May 2022) was an Israeli legal, moral and political philosopher. He was an advocate of legal positivism and is known for his conception of perfectionist liberalism. Raz spent m ...

argues law is an "authority" to mediate people's interests. Oliver Wendell Holmes said, "The prophecies of what the courts will do in fact, and nothing more pretentious, are what I mean by the law." In his ''Treatise on Law

''Treatise on Law'' is Thomas Aquinas' major work of legal philosophy. It forms questions 90–108 of the ''Prima Secundæ'' ("First artof the Second art) of the ''Summa Theologiæ'', Aquinas' masterwork of Scholastic philosophical theology. ...

,'' Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, OP (; it, Tommaso d'Aquino, lit=Thomas of Aquino; 1225 – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican friar and priest who was an influential philosopher, theologian and jurist in the tradition of scholasticism; he is known wi ...

argues that law is a rational ordering of things which concern the common good that is promulgated by whoever is charged with the care of the community. This definition has both positivist and naturalist elements.

Connection to morality and justice

Definitions of law often raise the question of the extent to which law incorporates morality.

Definitions of law often raise the question of the extent to which law incorporates morality. John Austin John Austin may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* John P. Austin (1906–1997), American set decorator

* Johnny Austin (1910–1983), American musician

*John Austin (author) (fl. 1940s), British novelist

Military

*John Austin (soldier) (1801� ...

's utilitarian

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for all affected individuals.

Although different varieties of utilitarianism admit different charact ...

answer was that law is "commands, backed by threat of sanctions, from a sovereign, to whom people have a habit of obedience".BixJohn Austin

Natural law

Natural law ( la, ius naturale, ''lex naturalis'') is a system of law based on a close observation of human nature, and based on values intrinsic to human nature that can be deduced and applied independently of positive law (the express enacted ...

yers on the other side, such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revol ...

, argue that law reflects essentially moral and unchangeable laws of nature. The concept of "natural law" emerged in ancient Greek philosophy

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BC, marking the end of the Greek Dark Ages. Greek philosophy continued throughout the Hellenistic period and the period in which Greece and most Greek-inhabited lands were part of the Roman Empi ...

concurrently and in connection with the notion of justice, and re-entered the mainstream of Western culture

image:Da Vinci Vitruve Luc Viatour.jpg, Leonardo da Vinci's ''Vitruvian Man''. Based on the correlations of ideal Body proportions, human proportions with geometry described by the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius in Book III of his treatise '' ...

through the writings of Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, OP (; it, Tommaso d'Aquino, lit=Thomas of Aquino; 1225 – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican friar and priest who was an influential philosopher, theologian and jurist in the tradition of scholasticism; he is known wi ...

, notably his ''Treatise on Law

''Treatise on Law'' is Thomas Aquinas' major work of legal philosophy. It forms questions 90–108 of the ''Prima Secundæ'' ("First artof the Second art) of the ''Summa Theologiæ'', Aquinas' masterwork of Scholastic philosophical theology. ...

''.

When having completed the first two parts of his book ''Splendeurs et misères des courtisanes

''Splendeurs et misères des courtisanes'', translated variously as ''The Splendors and Miseries of Courtesans'', ''A Harlot High and Low'', or as ''Lost Souls'', is an 1838-1847 novel by French novelist Honoré de Balzac, published in four initia ...

'', which he intended to be the end of the entire work, Honoré de Balzac

Honoré de Balzac ( , more commonly , ; born Honoré Balzac;Jean-Louis Dega, La vie prodigieuse de Bernard-François Balssa, père d'Honoré de Balzac : Aux sources historiques de La Comédie humaine, Rodez, Subervie, 1998, 665 p. 20 May 179 ...

visited the Conciergerie

The Conciergerie () ( en, Lodge) is a former courthouse and prison in Paris, France, located on the west of the Île de la Cité, below the Palais de Justice. It was originally part of the former royal palace, the Palais de la Cité, which als ...

. Thereafter, he decided to add a third part, finally named ''Où mènent les mauvais chemins'' (''The Ends of Evil Ways''), entirely dedicated to describing the conditions in prison.. In this third part, he states:

Hugo Grotius

Hugo Grotius (; 10 April 1583 – 28 August 1645), also known as Huig de Groot () and Hugo de Groot (), was a Dutch humanist, diplomat, lawyer, theologian, jurist, poet and playwright.

A teenage intellectual prodigy, he was born in Delf ...

, the founder of a purely rationalistic system of natural law, argued that law arises from both a social impulse—as Aristotle had indicated—and reason. Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (, , ; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German philosopher and one of the central Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works in epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and aes ...

believed a moral imperative requires laws "be chosen as though they should hold as universal laws of nature". Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 15 February 1748 O.S. 4 February 1747">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 4 February 1747ref name="Johnson2012" /> – 6 June 1832) was an English philosopher, jurist, an ...

and his student Austin, following David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; 7 May 1711 NS (26 April 1711 OS) – 25 August 1776) Cranston, Maurice, and Thomas Edmund Jessop. 2020 999br>David Hume" ''Encyclopædia Britannica''. Retrieved 18 May 2020. was a Scottish Enlightenment phil ...

, believed that this conflated the "is" and what "ought to be" problem. Bentham and Austin argued for law's positivism

Positivism is an empiricist philosophical theory that holds that all genuine knowledge is either true by definition or positive—meaning ''a posteriori'' facts derived by reason and logic from sensory experience.John J. Macionis, Linda M. ...

; that real law is entirely separate from "morality". Kant was also criticised by Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (; or ; 15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher, prose poet, cultural critic, philologist, and composer whose work has exerted a profound influence on contemporary philosophy. He began his c ...

, who rejected the principle of equality, and believed that law emanates from the will to power

The will to power (german: der Wille zur Macht) is a concept in the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche. The will to power describes what Nietzsche may have believed to be the main driving force in humans. However, the concept was never systematic ...

, and cannot be labeled as "moral" or "immoral".

In 1934, the Austrian philosopher Hans Kelsen

Hans Kelsen (; ; October 11, 1881 – April 19, 1973) was an Austrian jurist, legal philosopher and political philosopher. He was the author of the 1920 Austrian Constitution, which to a very large degree is still valid today. Due to the ris ...

continued the positivist tradition in his book the '' Pure Theory of Law''. Kelsen believed that although law is separate from morality, it is endowed with "normativity", meaning we ought to obey it. While laws are positive "is" statements (e.g. the fine for reversing on a highway ''is'' €500); law tells us what we "should" do. Thus, each legal system can be hypothesised to have a basic norm ('' Grundnorm'') instructing us to obey. Kelsen's major opponent, Carl Schmitt

Carl Schmitt (; 11 July 1888 – 7 April 1985) was a German jurist, political theorist, and prominent member of the Nazi Party. Schmitt wrote extensively about the effective wielding of political power. A conservative theorist, he is noted as ...

, rejected both positivism and the idea of the rule of law because he did not accept the primacy of abstract normative principles over concrete political positions and decisions. Therefore, Schmitt advocated a jurisprudence of the exception (state of emergency

A state of emergency is a situation in which a government is empowered to be able to put through policies that it would normally not be permitted to do, for the safety and protection of its citizens. A government can declare such a state du ...

), which denied that legal norms could encompass all of the political experience.Finn, ''Constitutions in Crisis'', 170–171

Later in the 20th century,

Later in the 20th century, H. L. A. Hart

Herbert Lionel Adolphus Hart (18 July 190719 December 1992), known simply as H. L. A. Hart, was an English legal philosopher. He was Professor of Jurisprudence at Oxford University and the Principal of Brasenose College, Oxford. His ...

attacked Austin for his simplifications and Kelsen for his fictions in ''The Concept of Law

''The Concept of Law'' is a 1961 book by the legal philosopher H. L. A. Hart and his most famous work. ''The Concept of Law'' presents Hart's theory of legal positivism—the view that laws are rules made by humans and that there is ...

''. Hart argued law is a system of rules, divided into primary (rules of conduct) and secondary ones (rules addressed to officials to administer primary rules). Secondary rules are further divided into rules of adjudication (to resolve legal disputes), rules of change (allowing laws to be varied) and the rule of recognition (allowing laws to be identified as valid). Two of Hart's students continued the debate: In his book ''Law's Empire

''Law's Empire'' is a 1986 text in legal philosophy by Ronald Dworkin, in which the author continues his criticism of the philosophy of legal positivism as promoted by H.L.A. Hart during the middle to late 20th century. The book introduces Dwork ...

'', Ronald Dworkin

Ronald Myles Dworkin (; December 11, 1931 – February 14, 2013) was an American philosopher, jurist, and scholar of United States constitutional law. At the time of his death, he was Frank Henry Sommer Professor of Law and Philosophy at New Y ...

attacked Hart and the positivists for their refusal to treat law as a moral issue. Dworkin argues that law is an " interpretive concept",Law's Empire

''Law's Empire'' is a 1986 text in legal philosophy by Ronald Dworkin, in which the author continues his criticism of the philosophy of legal positivism as promoted by H.L.A. Hart during the middle to late 20th century. The book introduces Dwork ...Joseph Raz

Joseph Raz (; he, יוסף רז; born Zaltsman; 21 March 19392 May 2022) was an Israeli legal, moral and political philosopher. He was an advocate of legal positivism and is known for his conception of perfectionist liberalism. Raz spent m ...

, on the other hand, defended the positivist outlook and criticised Hart's "soft social thesis" approach in ''The Authority of Law''.Raz, ''The Authority of Law'', 3–36 Raz argues that law is authority, identifiable purely through social sources and without reference to moral reasoning. In his view, any categorisation of rules beyond their role as authoritative instruments in mediation are best left to sociology

Sociology is a social science that focuses on society, human social behavior, patterns of social relationships, social interaction, and aspects of culture associated with everyday life. It uses various methods of empirical investigation and ...

, rather than jurisprudence.

History

The history of law links closely to the development of

The history of law links closely to the development of civilization

A civilization (or civilisation) is any complex society characterized by the development of a state, social stratification, urbanization, and symbolic systems of communication beyond natural spoken language (namely, a writing system).

C ...

. Ancient Egyptian law, dating as far back as 3000 BC, was based on the concept of Ma'at

Maat or Maʽat ( Egyptian:

mꜣꜥt /ˈmuʀʕat/, Coptic: ⲙⲉⲓ) refers to the ancient Egyptian concepts of truth, balance, order, harmony, law, morality, and justice. Ma'at was also the goddess who personified these concepts, and reg ...

and characterised by tradition, rhetoric

Rhetoric () is the art of persuasion, which along with grammar and logic (or dialectic), is one of the three ancient arts of discourse. Rhetoric aims to study the techniques writers or speakers utilize to inform, persuade, or motivate par ...

al speech, social equality and impartiality. By the 22nd century BC, the ancient Sumerian ruler Ur-Nammu

Ur-Nammu (or Ur-Namma, Ur-Engur, Ur-Gur, Sumerian: , ruled c. 2112 BC – 2094 BC middle chronology, or possibly c. 2048–2030 BC short chronology) founded the Sumerian Third Dynasty of Ur, in southern Mesopotamia, following several centuries ...

had formulated the first law code

A code of law, also called a law code or legal code, is a systematic collection of statutes. It is a type of legislation that purports to exhaustively cover a complete system of laws or a particular area of law as it existed at the time the cod ...

, which consisted of casuistic

In ethics, casuistry ( ) is a process of reasoning that seeks to resolve moral problems by extracting or extending theoretical rules from a particular case, and reapplying those rules to new instances. This method occurs in applied ethics and ju ...

statements ("if … then ..."). Around 1760 BC, King Hammurabi

Hammurabi (Akkadian: ; ) was the sixth Amorite king of the Old Babylonian Empire, reigning from to BC. He was preceded by his father, Sin-Muballit, who abdicated due to failing health. During his reign, he conquered Elam and the city-states ...

further developed Babylonian law

Babylonian law is a subset of cuneiform law that has received particular study due to the large amount of archaeological material that has been found for it. So-called "contracts" exist in the thousands, including a great variety of deeds, Conv ...

, by codifying and inscribing it in stone. Hammurabi placed several copies of his law code throughout the kingdom of Babylon as stelae

A stele ( ),Anglicized plural steles ( ); Greek plural stelai ( ), from Greek language, Greek , ''stēlē''. The Greek plural is written , ''stēlai'', but this is only rarely encountered in English. or occasionally stela (plural ''stelas'' or ...

, for the entire public to see; this became known as the Codex Hammurabi

The Code of Hammurabi is a Babylonian legal text composed 1755–1750 BC. It is the longest, best-organised, and best-preserved legal text from the ancient Near East. It is written in the Old Babylonian dialect of Akkadian language, Akkadian, p ...

. The most intact copy of these stelae was discovered in the 19th century by British Assyriologists

Assyriology (from Greek , ''Assyriā''; and , ''-logia'') is the archaeological, anthropological, and linguistic study of Assyria and the rest of ancient Mesopotamia (a region that encompassed what is now modern Iraq, northeastern Syria, southea ...

, and has since been fully transliterated

Transliteration is a type of conversion of a text from one script to another that involves swapping letters (thus ''trans-'' + '' liter-'') in predictable ways, such as Greek → , Cyrillic → , Greek → the digraph , Armenian → or ...

and translated into various languages, including English, Italian, German, and French.

The Old Testament

The Old Testament (often abbreviated OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew writings by the Israelites. The ...

dates back to 1280 BC and takes the form of moral imperatives as recommendations for a good society. The small Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

city-state, ancient Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh List ...

, from about the 8th century BC was the first society to be based on broad inclusion of its citizenry, excluding women and enslaved people

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

. However, Athens had no legal science or single word for "law", relying instead on the three-way distinction between divine law (''thémis''), human decree (''nomos'') and custom (''díkē''). Yet Ancient Greek law

Ancient Greek law consists of the laws and legal institutions of Ancient Greece.

The existence of certain general principles of law is implied by the custom of settling a difference between two Greek states, or between members of a single state, ...

contained major constitutional

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princip ...

innovations in the development of democracy

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which people, the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation ("direct democracy"), or to choo ...

.

Roman law

Roman law is the legal system of ancient Rome, including the legal developments spanning over a thousand years of jurisprudence, from the Twelve Tables (c. 449 BC), to the '' Corpus Juris Civilis'' (AD 529) ordered by Eastern Roman emperor Jus ...

was heavily influenced by Greek philosophy, but its detailed rules were developed by professional jurists and were highly sophisticated. Over the centuries between the rise and decline of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Medite ...

, law was adapted to cope with the changing social situations and underwent major codification under Theodosius II

Theodosius II ( grc-gre, Θεοδόσιος, Theodosios; 10 April 401 – 28 July 450) was Roman emperor for most of his life, proclaimed ''augustus'' as an infant in 402 and ruling as the eastern Empire's sole emperor after the death of his ...

and Justinian I

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renovat ...

.As a legal system, Roman law has affected the development of law worldwide. It also forms the basis for the law codes of most countries of continental Europe and has played an important role in the creation of the idea of a common European culture (Stein, ''Roman Law in European History'', 2, 104–107). Although codes were replaced by custom

Custom, customary, or consuetudinary may refer to:

Traditions, laws, and religion

* Convention (norm), a set of agreed, stipulated or generally accepted rules, norms, standards or criteria, often taking the form of a custom

* Norm (social), a ...

and case law

Case law, also used interchangeably with common law, is law that is based on precedents, that is the judicial decisions from previous cases, rather than law based on constitutions, statutes, or regulations. Case law uses the detailed facts of a ...

during the Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th or early 6th century to the 10th century. They marked the start of the M ...

, Roman law was rediscovered around the 11th century when medieval legal scholars began to research Roman codes and adapt their concepts to the canon law

Canon law (from grc, κανών, , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its members. It is th ...

, giving birth to the ''jus commune

''Jus commune'' or ''ius commune'' is Latin for "common law" in certain jurisdictions. It is often used by civil law jurists to refer to those aspects of the civil law system's invariant legal principles, sometimes called "the law of the land" i ...

''. Latin legal maxim

A legal maxim is an established principle or proposition of law, and a species of aphorism and general maxim. The word is apparently a variant of the Latin , but this latter word is not found in extant texts of Roman law with any denotation ex ...

s (called brocards) were compiled for guidance. In medieval England, royal courts developed a body of precedent

A precedent is a principle or rule established in a previous legal case that is either binding on or persuasive for a court or other tribunal when deciding subsequent cases with similar issues or facts. Common-law legal systems place great v ...

which later became the common law

In law, common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law created by judges and similar quasi-judicial tribunals by virtue of being stated in written opinions."The common law is not a brooding omniprese ...

. A Europe-wide Law Merchant

''Lex mercatoria'' (from the Latin for "merchant law"), often referred to as "the Law Merchant" in English, is the body of commercial law used by merchants throughout Europe during the medieval period. It evolved similar to English common law as ...

was formed so that merchants could trade with common standards of practice rather than with the many splintered facets of local laws. The Law Merchant, a precursor to modern commercial law, emphasised the freedom to contract and alienability of property. As nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo ...

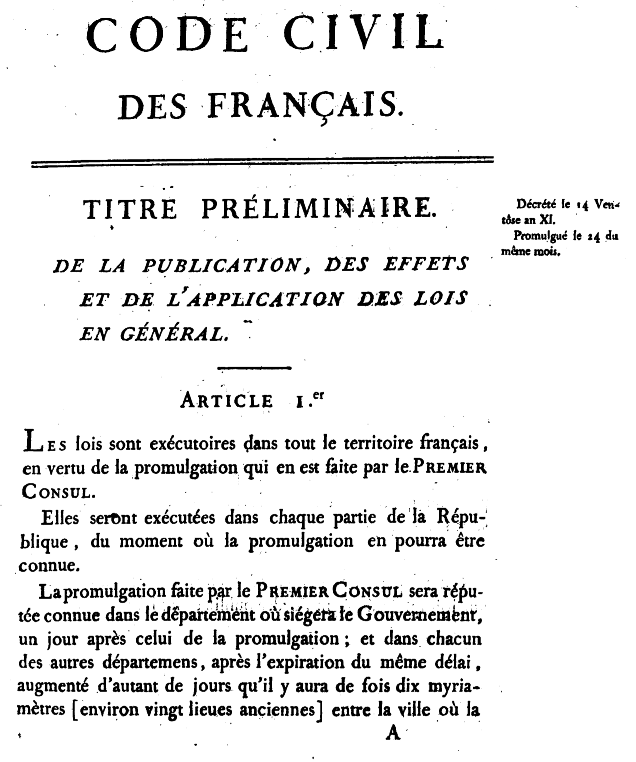

grew in the 18th and 19th centuries, the Law Merchant was incorporated into countries' local law under new civil codes. The Napoleonic

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

and German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

Codes became the most influential. In contrast to English common law, which consists of enormous tomes of case law, codes in small books are easy to export and easy for judges to apply. However, today there are signs that civil and common law are converging. EU law is codified in treaties, but develops through ''de facto'' precedent laid down by the European Court of Justice

The European Court of Justice (ECJ, french: Cour de Justice européenne), formally just the Court of Justice, is the supreme court of the European Union in matters of European Union law. As a part of the Court of Justice of the European Unio ...

.

Ancient

Ancient India

India, officially the Republic of India ( Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the ...

and China represent distinct traditions of law, and have historically had independent schools of legal theory and practice. The ''Arthashastra

The ''Arthashastra'' ( sa, अर्थशास्त्रम्, ) is an Ancient Indian Sanskrit treatise on statecraft, political science, economic policy and military strategy. Kautilya, also identified as Vishnugupta and Chanakya, is ...

'', probably compiled around 100 AD (although it contains older material), and the ''Manusmriti'' (c. 100–300 AD) were foundational treatises in India, and comprise texts considered authoritative legal guidance. Manu's central philosophy was tolerance and Pluralism (political philosophy), pluralism, and was cited across Southeast Asia. During the Muslim conquests in the Indian subcontinent, sharia was established by the Muslim sultanates and empires, most notably Mughal Empire's Fatawa-e-Alamgiri, compiled by emperor Aurangzeb and various scholars of Islam. In India, the Hinduism, Hindu legal tradition, along with Islamic law, were both supplanted by common law when India British Raj, became part of the British Empire. Malaysia, Brunei, Law of Singapore, Singapore and Law of Hong Kong, Hong Kong also adopted the common law system. The eastern Asia legal tradition reflects a unique blend of secular and religious influences. Japan was the first country to begin modernising its legal system along western lines, by importing parts of the Code Civil, French, but mostly the German Civil Code. This partly reflected Germany's status as a rising power in the late 19th century. Similarly, traditional Chinese law gave way to westernisation towards the final years of the Qing Dynasty in the form of six private law codes based mainly on the Japanese model of German law. Today Law of the Republic of China, Taiwanese law retains the closest affinity to the codifications from that period, because of the split between Chiang Kai-shek's nationalists, who fled there, and Mao Zedong's communists who won control of the mainland in 1949. The current legal infrastructure in the People's Republic of China was heavily influenced by Soviet Union, Soviet Socialist law, which essentially inflates administrative law at the expense of private law rights. Due to rapid industrialisation, today China is undergoing a process of reform, at least in terms of economic, if not social and political, rights. A new contract code in 1999 represented a move away from administrative domination. Furthermore, after negotiations lasting fifteen years, in 2001 China joined the World Trade Organization.

Legal systems

In general, legal systems can be split between civil law and common law systems. Modern scholars argue that the significance of this distinction has progressively declined; the numerous legal transplants, typical of modern law, result in the sharing by modern legal systems of many features traditionally considered typical of either common law or civil law.Mattei, ''Comparative Law and Economics'', 71 The term "civil law", referring to the Civil law (legal system), civilian legal system originating in continental Europe, should not be confused with "civil law" in the sense of the civil law (common law), common law topics distinct from criminal law and public law.

The third type of legal system—accepted by some countries without separation of church and state—is religious law, based on scriptures. The specific system that a country is ruled by is often determined by its history, connections with other countries, or its adherence to international standards. The sources of law, sources that jurisdictions adopt as authoritatively binding are the defining features of any legal system. Yet classification is a matter of form rather than substance since similar rules often prevail.

In general, legal systems can be split between civil law and common law systems. Modern scholars argue that the significance of this distinction has progressively declined; the numerous legal transplants, typical of modern law, result in the sharing by modern legal systems of many features traditionally considered typical of either common law or civil law.Mattei, ''Comparative Law and Economics'', 71 The term "civil law", referring to the Civil law (legal system), civilian legal system originating in continental Europe, should not be confused with "civil law" in the sense of the civil law (common law), common law topics distinct from criminal law and public law.

The third type of legal system—accepted by some countries without separation of church and state—is religious law, based on scriptures. The specific system that a country is ruled by is often determined by its history, connections with other countries, or its adherence to international standards. The sources of law, sources that jurisdictions adopt as authoritatively binding are the defining features of any legal system. Yet classification is a matter of form rather than substance since similar rules often prevail.

Civil law

Civil law is the legal system used in most countries around the world today. In civil law the sources recognised as authoritative are, primarily, legislation—especially Codification (law), codifications in constitutions or statutes passed by government—and

Civil law is the legal system used in most countries around the world today. In civil law the sources recognised as authoritative are, primarily, legislation—especially Codification (law), codifications in constitutions or statutes passed by government—and custom

Custom, customary, or consuetudinary may refer to:

Traditions, laws, and religion

* Convention (norm), a set of agreed, stipulated or generally accepted rules, norms, standards or criteria, often taking the form of a custom

* Norm (social), a ...

. Codifications date back millennia, with one early example being the Babylonian law, Babylonian ''Codex Hammurabi

The Code of Hammurabi is a Babylonian legal text composed 1755–1750 BC. It is the longest, best-organised, and best-preserved legal text from the ancient Near East. It is written in the Old Babylonian dialect of Akkadian language, Akkadian, p ...

''. Modern civil law systems essentially derive from legal codes issued by Byzantine Empire, Byzantine Emperor Justinian I

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renovat ...

in the 6th century, which were rediscovered by 11th century Italy. Roman law in the days of the Roman Republic and Empire was heavily procedural, and lacked a professional legal class. Instead a lay magistrate, ''iudex'', was chosen to adjudicate. Decisions were not published in any systematic way, so any case law that developed was disguised and almost unrecognised. Each case was to be decided afresh from the laws of the State, which mirrors the (theoretical) unimportance of judges' decisions for future cases in civil law systems today. From 529 to 534 AD the Byzantine Empire, Byzantine Emperor Justinian I

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renovat ...

codified and consolidated Roman law up until that point, so that what remained was one-twentieth of the mass of legal texts from before. This became known as the ''Corpus Juris Civilis''. As one legal historian wrote, "Justinian consciously looked back to the golden age of Roman law and aimed to restore it to the peak it had reached three centuries before." The Justinian Code remained in force in the East until the fall of the Byzantine Empire. Western Europe, meanwhile, relied on a mix of the Codex Theodosianus, Theodosian Code and Germanic customary law until the Justinian Code was rediscovered in the 11th century, and scholars at the University of Bologna used it to interpret their own laws. Civil law codifications based closely on Roman law, alongside some influences from religious law

Religious law includes ethical and moral codes taught by religious traditions. Different religious systems hold sacred law in a greater or lesser degree of importance to their belief systems, with some being explicitly antinomian whereas other ...

s such as canon law, continued to spread throughout Europe until the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment; then, in the 19th century, both France, with the ''Code Civil'', and Germany, with the ''Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch'', modernised their legal codes. Both these codes influenced heavily not only the law systems of the countries in continental Europe (e.g. Greece), but also the Law of Japan, Japanese and South Korea, Korean legal traditions. Today, countries that have civil law systems range from Russia and Turkey to most of Central America, Central and Latin America.

Anarchist law

Anarchism has been practiced in society in much of the world. Mass anarchist communities, ranging from Rojava, Syria to the United States, exist and vary from hundreds to millions. Anarchism encompasses a broad range of socialist, social political philosophies with different tendencies and implementation. Anarchist law primarily deals with how anarchism is implemented upon a society, the framework based on decentralized organizations and Mutual aid (organization theory), mutual aid, with representation through a form of direct democracy. Laws being based upon their need. A large portion of anarchist ideologies such as anarcho-syndicalism and anarcho-communism primarily focuses on decentralized worker unions, cooperatives and syndicates as the main instrument of society.Socialist law

Socialist law is the legal systems in communist states such as the former Soviet Union and the People's Republic of China. Academic opinion is divided on whether it is a separate system from civil law, given major deviations based on Marxist–Leninist ideology, such as subordinating the judiciary to the executive ruling party.Common law and equity

In Common law#1. Common law as opposed to statutory law and regulatory law, common law legal systems, decisions by courts are explicitly acknowledged as "law" on equal footing with statute law, statutes adopted through the legislative process and with Regulation (law), regulations issued by the Executive (government), executive branch. The "doctrine of precedent", or ''stare decisis'' (Latin for "to stand by decisions") means that decisions by higher courts bind lower courts, and future decisions of the same court, to assure that similar cases reach similar results. In Common law#2. Common law legal systems as opposed to civil law legal systems, contrast, in "civil law (legal system), civil law" systems, legislative statutes are typically more detailed, and judicial decisions are shorter and less detailed, because the judge or barrister is only writing to decide the single case, rather than to set out reasoning that will guide future courts.

Common law originated from England and has been inherited by almost every country once tied to the British Empire (except Malta, Law of Scotland, Scotland, the U.S. state of Louisiana law, Louisiana, and the Canadian province of Quebec law, Quebec). In medieval England, the Norman conquest of England, Norman conquest the law varied shire-to-shire, based on disparate tribal customs. The concept of a "common law" developed during the reign of Henry II of England, Henry II during the late 12th century, when Henry appointed judges that had authority to create an institutionalised and unified system of law "common" to the country. The next major step in the evolution of the common law came when John of England, King John was forced by his barons to sign a document limiting his authority to pass laws. This "great charter" or ''Magna Carta'' of 1215 also required that the King's entourage of judges hold their courts and judgments at "a certain place" rather than dispensing autocratic justice in unpredictable places about the country. A concentrated and elite group of judges acquired a dominant role in law-making under this system, and compared to its European counterparts the English judiciary became highly centralised. In 1297, for instance, while the highest court in France had fifty-one judges, the English Court of Common Pleas had five. This powerful and tight-knit judiciary gave rise to a systematised process of developing common law.

However, the system became overly systematised—overly rigid and inflexible. As a result, as time went on, increasing numbers of citizens petitioned the King to override the common law, and on the King's behalf the Lord Chancellor gave judgment to do what was equitable in a case. From the time of Thomas More, Sir Thomas More, the first lawyer to be appointed as Lord Chancellor, a systematic body of equity grew up alongside the rigid common law, and developed its own Court of Chancery. At first, equity was often criticised as erratic, that it varied according to the length of the Chancellor's foot. Over time, courts of equity developed solid Maxims of equity, principles, especially under John Scott, 1st Earl of Eldon, Lord Eldon. In the 19th century in England, and in West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish, 1937 in the U.S., the two systems were Common law#1870 through 20th century, and the procedural merger of law and equity, merged.

In developing the common law, Common law#Contrasting role of treatises and academic writings in common law and civil law systems, academic writings have always played an important part, both to collect overarching principles from dispersed case law, and to argue for change. William Blackstone, from around 1760, was the first scholar to collect, describe, and teach the common law. But merely in describing, scholars who sought explanations and underlying structures slowly changed the way the law actually worked.

In Common law#1. Common law as opposed to statutory law and regulatory law, common law legal systems, decisions by courts are explicitly acknowledged as "law" on equal footing with statute law, statutes adopted through the legislative process and with Regulation (law), regulations issued by the Executive (government), executive branch. The "doctrine of precedent", or ''stare decisis'' (Latin for "to stand by decisions") means that decisions by higher courts bind lower courts, and future decisions of the same court, to assure that similar cases reach similar results. In Common law#2. Common law legal systems as opposed to civil law legal systems, contrast, in "civil law (legal system), civil law" systems, legislative statutes are typically more detailed, and judicial decisions are shorter and less detailed, because the judge or barrister is only writing to decide the single case, rather than to set out reasoning that will guide future courts.

Common law originated from England and has been inherited by almost every country once tied to the British Empire (except Malta, Law of Scotland, Scotland, the U.S. state of Louisiana law, Louisiana, and the Canadian province of Quebec law, Quebec). In medieval England, the Norman conquest of England, Norman conquest the law varied shire-to-shire, based on disparate tribal customs. The concept of a "common law" developed during the reign of Henry II of England, Henry II during the late 12th century, when Henry appointed judges that had authority to create an institutionalised and unified system of law "common" to the country. The next major step in the evolution of the common law came when John of England, King John was forced by his barons to sign a document limiting his authority to pass laws. This "great charter" or ''Magna Carta'' of 1215 also required that the King's entourage of judges hold their courts and judgments at "a certain place" rather than dispensing autocratic justice in unpredictable places about the country. A concentrated and elite group of judges acquired a dominant role in law-making under this system, and compared to its European counterparts the English judiciary became highly centralised. In 1297, for instance, while the highest court in France had fifty-one judges, the English Court of Common Pleas had five. This powerful and tight-knit judiciary gave rise to a systematised process of developing common law.

However, the system became overly systematised—overly rigid and inflexible. As a result, as time went on, increasing numbers of citizens petitioned the King to override the common law, and on the King's behalf the Lord Chancellor gave judgment to do what was equitable in a case. From the time of Thomas More, Sir Thomas More, the first lawyer to be appointed as Lord Chancellor, a systematic body of equity grew up alongside the rigid common law, and developed its own Court of Chancery. At first, equity was often criticised as erratic, that it varied according to the length of the Chancellor's foot. Over time, courts of equity developed solid Maxims of equity, principles, especially under John Scott, 1st Earl of Eldon, Lord Eldon. In the 19th century in England, and in West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish, 1937 in the U.S., the two systems were Common law#1870 through 20th century, and the procedural merger of law and equity, merged.

In developing the common law, Common law#Contrasting role of treatises and academic writings in common law and civil law systems, academic writings have always played an important part, both to collect overarching principles from dispersed case law, and to argue for change. William Blackstone, from around 1760, was the first scholar to collect, describe, and teach the common law. But merely in describing, scholars who sought explanations and underlying structures slowly changed the way the law actually worked.

Religious law

Religious law is explicitly based on religious precepts. Examples include the Jewish Halakha and Islamic Sharia—both of which translate as the "path to follow"—while Christian canon law also survives in some church communities. Often the implication of religion for law is unalterability, because the word of God cannot be amended or legislated against by judges or governments. However, a thorough and detailed legal system generally requires human elaboration. For instance, the Quran has some law, and it acts as a source of further law through interpretation, ''Qiyas'' (reasoning by analogy), ''Ijma'' (consensus) andprecedent

A precedent is a principle or rule established in a previous legal case that is either binding on or persuasive for a court or other tribunal when deciding subsequent cases with similar issues or facts. Common-law legal systems place great v ...

. This is mainly contained in a body of law and jurisprudence known as Sharia and Fiqh respectively. Another example is the Torah or Old Testament

The Old Testament (often abbreviated OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew writings by the Israelites. The ...

, in the Pentateuch or Five Books of Moses. This contains the basic code of Jewish law, which some Israeli communities choose to use. The Halakha is a code of Jewish law that summarizes some of the Talmud's interpretations. Nevertheless, Israeli law allows litigants to use religious laws only if they choose. Canon law is only in use by members of the Canon law (Catholic Church), Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Anglican Communion.

Canon law

Canon law (from Greek language, Greek ''kanon'', a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical jurisdiction, ecclesiastical authority (Church leadership), for the government of a Christian organisation or church and its members. It is the internal ecclesiastical law governing the Catholic Church (both the Latin Church and the Eastern Catholic Churches), the Eastern Orthodox Church, Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodox churches, and the individual national churches within the Anglican Communion. The way that such church law is legislative power, legislated, interpreted and at times court, adjudicated varies widely among these three bodies of churches. In all three traditions, a Canon (canon law), canon was originally a rule adopted by a church council; these canons formed the foundation of canon law. The Catholic Church has the oldest continuously functioning legal system in the western world, predating the evolution of modern Europeancivil law

Civil law may refer to:

* Civil law (common law), the part of law that concerns private citizens and legal persons

* Civil law (legal system), or continental law, a legal system originating in continental Europe and based on Roman law

** Private la ...

and common law systems. The 1983 Code of Canon Law governs the Latin Church ''sui juris''. The Eastern Catholic Churches, which developed different disciplines and practices, are governed by the ''Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches''. The canon law of the Catholic Church influenced the common law

In law, common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law created by judges and similar quasi-judicial tribunals by virtue of being stated in written opinions."The common law is not a brooding omniprese ...

during the medieval period through its preservation of Roman law

Roman law is the legal system of ancient Rome, including the legal developments spanning over a thousand years of jurisprudence, from the Twelve Tables (c. 449 BC), to the '' Corpus Juris Civilis'' (AD 529) ordered by Eastern Roman emperor Jus ...

doctrine such as the presumption of innocence.

Sharia law

Until the 18th century, Sharia law was practiced throughout the Muslim world in a non-codified form, with the Ottoman Empire's Mecelle code in the 19th century being a first attempt at Codification (law), codifying elements of Sharia law. Since the mid-1940s, efforts have been made, in country after country, to bring Sharia law more into line with modern conditions and conceptions.Anderson, ''Law Reform in the Middle East'', 43 In modern times, the legal systems of many Muslim countries draw upon both civil and common law traditions as well as Islamic law and custom. The constitutions of certain Muslim states, such as Egypt and Afghanistan, recognise Islam as the religion of the state, obliging legislature to adhere to Sharia. Saudi Arabia recognises Quran as its constitution, and is governed on the basis of Islamic law.Saudi Arabia

Until the 18th century, Sharia law was practiced throughout the Muslim world in a non-codified form, with the Ottoman Empire's Mecelle code in the 19th century being a first attempt at Codification (law), codifying elements of Sharia law. Since the mid-1940s, efforts have been made, in country after country, to bring Sharia law more into line with modern conditions and conceptions.Anderson, ''Law Reform in the Middle East'', 43 In modern times, the legal systems of many Muslim countries draw upon both civil and common law traditions as well as Islamic law and custom. The constitutions of certain Muslim states, such as Egypt and Afghanistan, recognise Islam as the religion of the state, obliging legislature to adhere to Sharia. Saudi Arabia recognises Quran as its constitution, and is governed on the basis of Islamic law.Saudi Arabia, Jurist Iran has also witnessed a reiteration of Islamic law into its legal system after 1979. During the last few decades, one of the fundamental features of the movement of Islamic resurgence has been the call to restore the Sharia, which has generated a vast amount of literature and affected Global politics, world politics.Hallaq, ''The Origins and Evolution of Islamic Law'', 1

Legal methods

There are distinguished methods of legal reasoning (applying the law) and methods of interpreting (construing) the law. The former are legal syllogism, which holds sway in civil law legal systems, analogy, which is present in common law legal systems, especially in the US, and argumentative theories that occur in both systems. The latter are different rules (directives) of legal interpretation such as directives of linguistic interpretation, teleological interpretation or systemic interpretation as well as more specific rules, for instance, golden rule or mischief rule. There are also many other arguments and cannons of interpretation which altogether make statutory interpretation possible. Law professor and former United States Attorney General Edward H. Levi noted that the "basic pattern of legal reasoning is reasoning by example"—that is, reasoning by comparing outcomes in cases resolving similar legal questions. In a U.S. Supreme Court case regarding procedural efforts taken by a debt collection company to avoid errors, Justice Sonia Sotomayor, Sotomayor cautioned that "legal reasoning is not a mechanical or strictly linear process". Jurimetrics is the formal application of quantitative methods, especially Probability theory, probability and statistics, to legal questions. The use of statistical methods in court cases and law review articles has grown massively in importance in the last few decades.Legal institutions

The main institutions of law in industrialised countries are independent courts, representative parliaments, an accountable executive, the military and police, bureaucracy, bureaucratic organisation, the legal profession and civil society itself. John Locke, in his ''Two Treatises of Government'', and Charles de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu, Baron de Montesquieu in ''The Spirit of the Laws'', advocated for a separation of powers between the political, legislature and executive bodies. Their principle was that no person should be able to usurp all powers of the State (polity), state, in contrast to the Absolute monarchy, absolutist theory of Thomas Hobbes' ''Leviathan (Hobbes book), Leviathan''.Thomas Hobbes, ''Leviathan''XVII

/ref> Sun Yat-sen's Constitution of the Republic of China, Five Power Constitution for the Republic of China took the separation of powers further by having two additional branches of government—a Control Yuan for auditing oversight and an Examination Yuan to manage the employment of public officials. Max Weber and others reshaped thinking on the extension of state. Modern military, policing and bureaucratic power over ordinary citizens' daily lives pose special problems for accountability that earlier writers such as Locke or Montesquieu could not have foreseen. The custom and practice of the legal profession is an important part of people's access to

justice

Justice, in its broadest sense, is the principle that people receive that which they deserve, with the interpretation of what then constitutes "deserving" being impacted upon by numerous fields, with many differing viewpoints and perspective ...

, whilst civil society is a term used to refer to the social institutions, communities and partnerships that form law's political basis.

Judiciary

A judiciary is a number of judges mediating disputes to determine outcome. Most countries have systems of appeal courts, with an Supreme court, apex court as the ultimate judicial authority. In the United States, this authority is the Supreme Court of the United States, Supreme Court; in Australia, the High Court of Australia, High Court; in the UK, the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom, Supreme Court; in Germany, the ''Bundesverfassungsgericht''; and in France, the ''Cour de cassation (France), Cour de Cassation''. For most European countries the European Court of Justice in Luxembourg can overrule national law, when EU law is relevant. The European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg allows citizens of the Council of Europe member states to bring cases relating to human rights issues before it. Some countries allow their highest judicial authority to overrule legislation they determine to be constitutionality, unconstitutional. For example, in ''Brown v. Board of Education'', the United States Supreme Court nullified many state statutes that had established Racial segregation in the United States, racially segregated schools, finding such statutes to be incompatible with the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. A judiciary is theoretically bound by the constitution, just as all other government bodies are. In most countries judges may only interpretivism (legal), interpret the constitution and all other laws. But in common law countries, where matters are not constitutional, the judiciary may also create law under the doctrine of precedent. The UK, Finland and New Zealand assert the ideal of parliamentary sovereignty, whereby the unelected judiciary may not overturn law passed by a democratic legislature. In communist states, such as China, the courts are often regarded as parts of the executive, or subservient to the legislature; governmental institutions and actors exert thus various forms of influence on the judiciary. In Muslim countries, courts often examine whether state laws adhere to the Sharia: the Supreme Constitutional Court of Egypt may invalidate such laws,Sherif, ''Constitutions of Arab Countries'', 158 and in Iran the Guardian Council ensures the compatibility of the legislation with the "criteria of Islam".Legislature

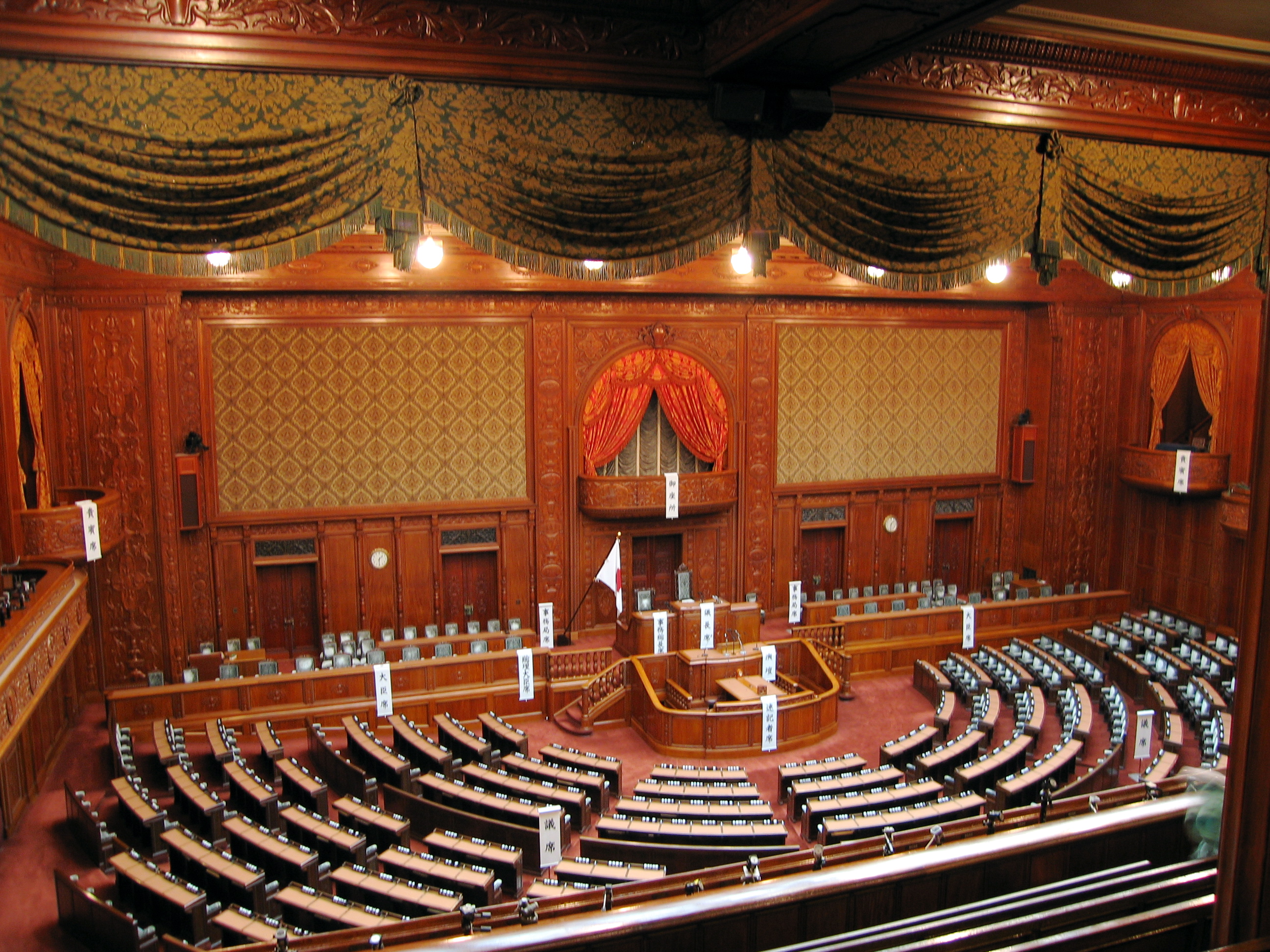

Prominent examples of legislatures are the Houses of Parliament in London, the United States Congress, Congress in Washington, D.C., the Bundestag in Berlin, the Duma in Moscow, the Parliament of Italy, Parlamento Italiano in Rome and the National Assembly of France, ''Assemblée nationale'' in Paris. By the principle of representative government people vote for politicians to carry out ''their'' wishes. Although countries like Israel, Greece, Sweden and China are unicameralism, unicameral, most countries are bicameralism, bicameral, meaning they have two separately appointed legislative houses.Rik

Prominent examples of legislatures are the Houses of Parliament in London, the United States Congress, Congress in Washington, D.C., the Bundestag in Berlin, the Duma in Moscow, the Parliament of Italy, Parlamento Italiano in Rome and the National Assembly of France, ''Assemblée nationale'' in Paris. By the principle of representative government people vote for politicians to carry out ''their'' wishes. Although countries like Israel, Greece, Sweden and China are unicameralism, unicameral, most countries are bicameralism, bicameral, meaning they have two separately appointed legislative houses.Rik