L'huomo Di Lettere on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''L'huomo di lettere difeso ed emendato'' (Rome, 1645) by the Ferrarese Jesuit

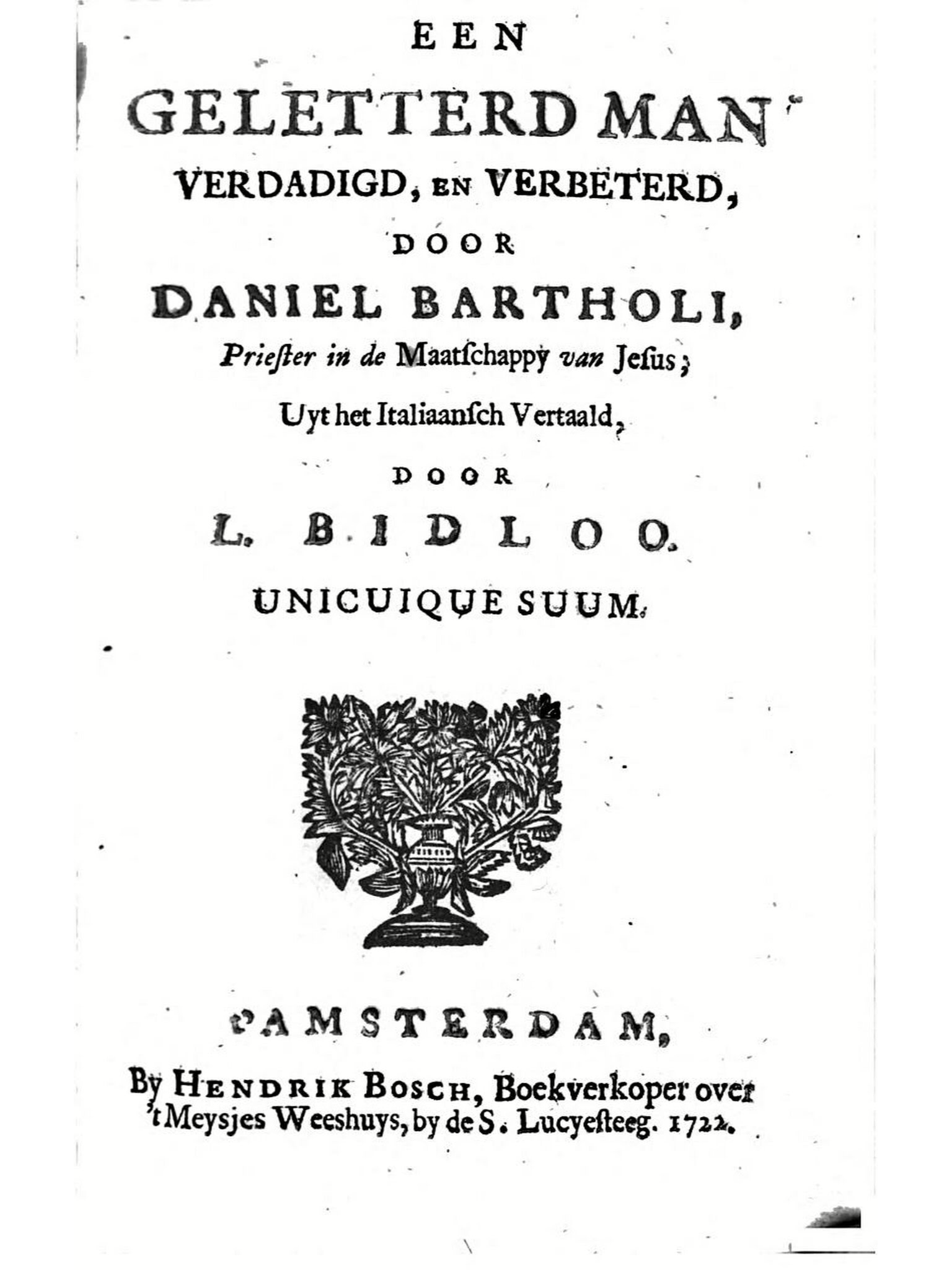

Een Geletterd Man Verdadigd, en Verbeterd door Daniel Bartholi

/ref>

{{DEFAULTSORT:Huomo Di Lettere 1645 books Italian literature Jesuit publications Treatises Works about intelligentsia

Daniello Bartoli

Daniello Bartoli (; 12 February 160813 January 1685) was an Italian Jesuit writer and historiographer, celebrated by the poet Giacomo Leopardi as the "Dante of Italian prose"

Ferrara

He was born in Ferrara. His father, Tiburzio was a chemist as ...

(1608–1685) is a two-part treatise on the man of letters

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and reflection about the nature of reality, especially the nature of society and proposed solutions for its normative problems. Coming from the world of culture, either ...

bringing together material he had assembled over twenty years since his entry in 1623 into the Society of Jesus

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rome. It was founded in 1540 ...

as a brilliant student, a successful teacher of rhetoric and a celebrated preacher. His international literary success with this work led to his appointment in Rome as the official historiographer

Historiography is the study of the methods used by historians in developing history as an academic discipline. By extension, the term "historiography" is any body of historical work on a particular subject. The historiography of a specific to ...

of the Society of Jesus

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rome. It was founded in 1540 ...

and his monumental '' Istoria della Compagnia di Gesu'' (1650–1673).

The entire patrimony of classical rhetoric was centered around the figure of the Ciceronian Orator

An orator, or oratist, is a public speaker, especially one who is eloquent or skilled.

Etymology

Recorded in English c. 1374, with a meaning of "one who pleads or argues for a cause", from Anglo-French ''oratour'', Old French ''orateur'' (14 ...

, the ''vir bonus dicendi peritus'' of Quintilian

Marcus Fabius Quintilianus (; 35 – 100 AD) was a Roman educator and rhetorician born in Hispania, widely referred to in medieval schools of rhetoric and in Renaissance writing. In English translation, he is usually referred to as Quin ...

as the ideal combination of moral values and eloquence. In Jesuit terms this dual ideal becomes '' santità e lettere'' for membership in the emerging Republic of Letters

The Republic of Letters (''Res Publica Litterarum'' or ''Res Publica Literaria'') was the long-distance intellectual community in the late 17th and 18th centuries in Europe and the Americas. It fostered communication among the intellectuals of th ...

. Bartoli confidently asserts the validity of this model represented in his ''huomo di lettere''. In his introduction Bartoli constructs his two part presentation out of a maxim of oratory, that recalls Quintilian

Marcus Fabius Quintilianus (; 35 – 100 AD) was a Roman educator and rhetorician born in Hispania, widely referred to in medieval schools of rhetoric and in Renaissance writing. In English translation, he is usually referred to as Quin ...

, but is of his fashioning: ''"Si qua obscuritas litterarum, nisi quia sed obtrectationibus imperitorum vel abutentium vitio"'' And he effectively dramatizes a tableau of the archetypical Anaxagoras

Anaxagoras (; , ''Anaxagóras'', 'lord of the assembly'; ) was a Pre-Socratic Greek philosopher. Born in Clazomenae at a time when Asia Minor was under the control of the Persian Empire, Anaxagoras came to Athens. In later life he was charged ...

enlightening the ignorant by demystifying the cause of a solar eclipse

A solar eclipse occurs when the Moon passes between Earth and the Sun, thereby obscuring the view of the Sun from a small part of Earth, totally or partially. Such an alignment occurs approximately every six months, during the eclipse season i ...

through his scientific understanding. This is a prelude to the cohort of ancient philosophers he employs as part of his rhetorical agenda to characterize the Senecan ''literatus'' as the model for his philosopher hero, the man of letters. Part I defends the man of letters against the neglect of rulers and fortune and make him a conduit of an intellectual beatitude, ''il gusto dell'intendere'', that is the basis of his moral and social Ataraxia

In Ancient Greek philosophy, ( Greek: , from indicating negation or absence and with the abstract noun suffix ), generally translated as , , , or , is a lucid state of robust equanimity characterized by ongoing freedom from distress and wo ...

. He develops his theme of Stoic superiority under two headings, ''La Sapienza felice anche nelle Miserie'' and ''L'Ignoranza misera anche nelle Felicità'' with regular reference to the Epistulae morales ad Lucilium

' (Latin for "Moral Letters to Lucilius"), also known as the ''Moral Epistles'' and ''Letters from a Stoic'', is a letter collection of 124 letters that Seneca the Younger wrote at the end of his life, during his retirement, after he had worked ...

of Seneca, and exempla

An exemplum (Latin for "example", exempla, ''exempli gratia'' = "for example", abbr.: ''e.g.'') is a moral anecdote, brief or extended, real or fictitious, used to illustrate a point. The word is also used to express an action performed by anot ...

taken from Diogenes Laërtius

Diogenes Laërtius ( ; , ; ) was a biographer of the Greek philosophers. Little is definitively known about his life, but his surviving book ''Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers'' is a principal source for the history of ancient Greek ph ...

, Plutarch

Plutarch (; , ''Ploútarchos'', ; – 120s) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''Parallel Lives'', ...

, Pliny, Aelian Aelian or Aelianus may refer to:

* Aelianus Tacticus, 2nd-century Greek military writer in Rome

* Casperius Aelianus (13–98 AD), Praetorian Prefect, executed by Trajan

* Claudius Aelianus

Claudius Aelianus (; ), commonly Aelian (), born at Pr ...

, with frequent quotations, often unsourced, from Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; 15 October 70 BC21 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Rome, ancient Roman poet of the Augustan literature (ancient Rome), Augustan period. He composed three of the most fa ...

and the poets, and headed by Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; ; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430) was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Africa. His writings deeply influenced the development of Western philosop ...

and Tertullian

Tertullian (; ; 155 – 220 AD) was a prolific Early Christianity, early Christian author from Roman Carthage, Carthage in the Africa (Roman province), Roman province of Africa. He was the first Christian author to produce an extensive co ...

and Synesius

Synesius of Cyrene (; ; c. 373 – c. 414) was a Greek bishop of Ptolemais in ancient Libya, a part of the Western Pentapolis of Cyrenaica after 410. He was born of wealthy parents at Balagrae (now Bayda, Libya) near Cyrene between 370 and 3 ...

among the Christian writers. Part II seeks to emend the faults of the present day writer in 9 chapters under the headings, ''Ladroneccio'', ''Lascivia'', ''Maldicenza'', ''Alterezza'', ''Dapoccaggine'', ''Imprudenza'', ''Ambitione'', ''Avarizia'', ''Oscurita''. He calls on more modern authors in these chapters, such as Oviedo

Oviedo () or Uviéu (Asturian language, Asturian: ) is the capital city of the Principality of Asturias in northern Spain and the administrative and commercial centre of the region. It is also the name of the municipality that contains th ...

, Erasmus

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus ( ; ; 28 October c. 1466 – 12 July 1536), commonly known in English as Erasmus of Rotterdam or simply Erasmus, was a Dutch Christian humanist, Catholic priest and Catholic theology, theologian, educationalist ...

and Cardanus. The final chapter takes particular aim at excesses of the precious baroque

The Baroque ( , , ) is a Western Style (visual arts), style of Baroque architecture, architecture, Baroque music, music, Baroque dance, dance, Baroque painting, painting, Baroque sculpture, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished from ...

style then in vogue and encourages the beginner to profit from the ars rhetorica expounded by Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, orator, writer and Academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises tha ...

in style and composition. His paraenesis

In rhetoric, protrepsis () and paraenesis (παραίνεσις) are two closely related styles of exhortation that are employed by moral philosophy, moral philosophers. While there is a widely accepted distinction between the two that is employed ...

combines a stream of classical ''exempla'' with modern instances of the great Italian explorers, such as his heroes in geography, Columbus

Columbus is a Latinized version of the Italian surname "''Colombo''". It most commonly refers to:

* Christopher Columbus (1451–1506), the Italian explorer

* Columbus, Ohio, the capital city of the U.S. state of Ohio

* Columbus, Georgia, a city i ...

, and astronomy, Galileo

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642), commonly referred to as Galileo Galilei ( , , ) or mononymously as Galileo, was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a poly ...

, and lively references to the modern tradition of Italian letters from Dante

Dante Alighieri (; most likely baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri; – September 14, 1321), widely known mononymously as Dante, was an Italian Italian poetry, poet, writer, and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', originally called ...

, his favorite, to Ariosto

Ludovico Ariosto (, ; ; 8 September 1474 – 6 July 1533) was an Italian poet. He is best known as the author of the romance epic '' Orlando Furioso'' (1516). The poem, a continuation of Matteo Maria Boiardo's ''Orlando Innamorato'', describ ...

and Tasso

TASSO (Two Arm Spectrometer SOlenoid) was a particle detector at the PETRA particle accelerator at the German national laboratory DESY. The TASSO collaboration is best known for having discovered the gluon, the mediator of the strong interaction an ...

.

''Dell'Huomo di lettere difeso ed emendato'' 1645

In 1645 the appearance of Bartoli's first book initiated an international literary sensation. The work, reprinted eight times in the first year, quickly inserted itself in the regional literary debates of the time, with an unauthorized Florentine edition (1645) dedicated toSalvator Rosa

Salvator Rosa (1615 – March 15, 1673) is best known today as an Italian Baroque painter, whose romanticized landscapes and history paintings, often set in dark and untamed nature, exerted considerable influence from the 17th century into the ...

soon challenged by a Bolognese edition (1646) dedicated to Virgilio Malvezzi

Virgilio Malvezzi, Marchese (Marquis) di Castel Guelfo (; 8 September 1595 – 11 August 1654) was an Italian historian, essayist, soldier and diplomat. Born in Bologna, he became court historian to Philip IV of Spain. His work was hugely influent ...

. Over the following three decades and beyond there were another thirty printings at a dozen different Italian presses, especially Venetian, of which half a dozen "per Giunti" with a signature frontispiece title illustration.

Bartoli's literary "how to" book spread its influence well beyond the geographical and literary confines of Italy. During the process of her conversion to Roman Catholicism at the hands of the Jesuits in the 1650s Christina, Queen of Sweden

Christina (; 18 December O.S. 8 December">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 8 December1626 – 19 April 1689), a member of the House of Vasa, was Monarchy of Sweden, Queen of Sweden from ...

specifically requested a copy of this celebrated work be sent to her in Stockholm.

It seems to have fulfilled the Baroque

The Baroque ( , , ) is a Western Style (visual arts), style of Baroque architecture, architecture, Baroque music, music, Baroque dance, dance, Baroque painting, painting, Baroque sculpture, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished from ...

dream of an energetic rhetorical eloquence to which the age aspired. Through its gallery of exemplary stylizations and picturesque moral encouragements it defends and emends not only the aspiring ''letterato'', but also an updated classicism open to modernity, but diffident of excess. The book's international proliferation made it a vehicle of the cultural ascendancy of the Jesuits

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

as modern classicists during the Baroque. Years later, Bartoli provided a revision for the collected edition. After Bartoli's death in 1685 editions of his works continued to appear, particularly in the early nineteenth century when he was idolized for his mastery of language and style. Giacinto Marietti printed an excellent complete edition of Bartoli in Turin between 1825 and 1856.

Translations

In Bartoli's lifetime and beyond, in addition to the host of Italian editions, his celebrated work was translated into six different languages by men of letters of other nationalities, Jesuits and non-Jesuits, illustrating on a European scale the Baroque vogue that Bartoli enjoyed in theRepublic of Letters

The Republic of Letters (''Res Publica Litterarum'' or ''Res Publica Literaria'') was the long-distance intellectual community in the late 17th and 18th centuries in Europe and the Americas. It fostered communication among the intellectuals of th ...

of his time. Ie appeared in 1651 in French, in 1654 in German, in 1660 in English, in 1672 in Latin, in 1678 in Spanish and in 1722 in Dutch.

''La Guide des Beaux Esprits'' 1651

The French translation was first to appear in 1651. It was done by the Jesuit writer Thomas LeBlanc, (1599–1669) upon his return from Italy where the book had made Bartoli famous for his eloquence and erudition. LeBlanc was author of a five-volume commentary on the Psalms of David in Latin and of several pastoral works in French. It first appeared as ''L'Homme de lettres'' (Pont-a-Mousson). In 1654 it was reprinted under the more galant title, ''La Guide des Beaux Esprits'' and as such went through several editions. The fifth printing of 1669 was dedicated to Charles Le Jay, Baron de Tilly, from the ascendantnoblesse de robe

Under the Ancien Régime of France, the Nobles of the Robe or Nobles of the Gown () were French aristocrats whose rank came from holding certain judicial or administrative posts. As a rule, the positions did not of themselves give the holder a t ...

, influential supporters of the Society of Jesus and its colleges

A college (Latin: ''collegium'') may be a tertiary education, tertiary educational institution (sometimes awarding academic degree, degrees), part of a collegiate university, an institution offering vocational education, a further educatio ...

. Timothée Hureau de Livoy (1715–1777), a Barnabite

The Barnabites (), officially named as the Clerics Regular of Saint Paul (), are a religious order of clerics regular founded in 1530 in the Catholic Church. They are associated with the Angelic Sisters of Saint Paul and the members of the Bar ...

priest and lexicographer was the translator of Denina

''Denina'' is a monotypic genus of European mayflies in the family Ephemeridae

Ephemeridae is a family of mayfly, mayflies with about 150 described species found throughout the world except Australia and Oceania.

Description

Ephemerids are g ...

and Muratori. In 1769 his Bartoli translation appeared with critical notes ''L'Homme de lettres, ouvrage traduit de l'italien augmenté de Notes historiques et critiques''

''Vertheidigung der Kunstliebenden und Gelehrten Anständige Sitten'' 1654

In Nürnberg in 1654 a German version appeared anonymously under the title, ''Vertheidigung der Kunstliebenden und Gelehrten anstandigere Sitten,'' The translator, Count Georg Adam von Kuefstein (1605–1656) in his preface signs himself ''Der Kunstliebende,'' his moniker as a member of the prestigious language academy, theFruitbearing Society

The Fruitbearing Society (German Die Fruchtbringende Gesellschaft, lat. ''Societas Fructifera'') was a German literary society founded in 1617 in Weimar by German scholars and nobility. Its aim was to standardize vernacular German and promote it ...

(''Fruchtbringende Gesellschaft'') under whose name and auspices the book was issued. There is a frontispiece title engraving with a shielded angel "''ratio''" defending "''Vertheidigung''" the writer "''eruditio''". Underneath the book on the writing table there is a scroll which surreptitiously spells out the author's name as "D. BAR/TOLI". After the title page come the translator's preface and 11 poetical compositions by other Gesellschaft members including the Nurenberger Georg Philipp Harsdörffer

Georg Philipp Harsdörffer (1 November 1607 – 17 September 1658) was a Jurist, Baroque-period German poet and translator.

Life and career

Georg Philipp Harsdörffer was born in Nuremberg on 1 November 1607 into a patrician family. He studied ...

, ''Der Spielende'', Sigmund von Birken

Sigmund von Birken (25 April 1626 – 12 June 1681) was a German poet of the Baroque. He was born in Wildstein, near Eger, and died in Nuremberg, aged 55.

His pupil, Sibylle Ursula von Braunschweig-Lüneburg wrote part of a novel, ''Die Durchla ...

who oversaw the preparation of the book, Wolf Heimhardt von Hohberg ''Der Sinnreiche'', Cambyse Bianchi del Piano, ''Der Seltene'', from Bologna, who collaborated with Kufstein on the translation, Johan Wilhelm von Stuhlenberg, ''Der Ungluckselige'', Erasmus der Junger von Strahlemberg, ''Der Liedende'', Christoff Dietrick von Schallenberg, ''Der Schallende'' and Harsdörffer's son, Carl Gottfried. These poetic exercises, including a pastoral dialogue, introduce the themes of Bartoli's text. Bartoli's numerous Latin quotations are given here in German, directly along with the citations in the margin. At the end there is an index for subjects and one for persons and finally a helpful list of the classical authorities with page numbers.

''The Learned Man Defended and Reformed'' 1660

During Cromwell'sProtectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a State (polity), state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over ...

in the 1650s many English notables, such as Sir Kenelm Digby

Sir Kenelm Digby (11 July 1603 – 11 June 1665) was an English courtier and diplomat. He was also a highly reputed natural philosopher, astrologer and known as a leading Roman Catholic intellectual and Blackloist. For his versatility, he is ...

gravitated to Rome and were caught up in the vogue of Bartoli's L'huomo di lettere. Digby is said to have made a translation, but this was not printed, though it is mentioned in the foreword of Thomas Salusbury whose translation coincides with the return of Charles II. The London edition of 1660 celebrates the Restoration of the Stuarts

The House of Stuart, originally spelled Stewart, also known as the Stuart dynasty, was a royal house of Scotland, England, Ireland and later Great Britain. The family name comes from the office of High Steward of Scotland, which had been hel ...

with letters of dedication to two of its chief protagonists George Monck

George Monck, 1st Duke of Albemarle (6 December 1608 3 January 1670) was an English military officer and politician who fought on both sides during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. A prominent military figure under the Commonwealth, his support ...

and William Prynne

William Prynne (1600 – 24 October 1669), an English lawyer, voluble author, polemicist and political figure, was a prominent Puritan opponent of church policy under William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury (1633–1645). His views were Presbyter ...

. A connoisseur of Italy and admirer of Bartoli, Thomas Salusbury (ca.1623-ca.1666) was connected with the prominent Anglo-

Welsh Salusbury family

The Salusbury family was an Anglo-Welsh family notable for their social prominence, wealth, literary contributions and philanthropy. They were patrons of the arts and were featured in William Shakespeare's The Phoenix and the Turtle and other wor ...

, whose coat of arms is on the frontispiece engraving of ''The Learned Man''. Some have attributed this translation to the English Jesuit Thomas Plowden. Salusbury followed up with ''Mathematical Collections and Translations'' (1661) of important scientific works by Galileo and his contemporaries The rare second volume of translated treatises (1665) has the first biography of Galileo Galilei

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642), commonly referred to as Galileo Galilei ( , , ) or mononymously as Galileo, was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a poly ...

in English. The title page of ''The Learned Man'' states the work was written by "the happy pen" of p. Daniel Bartolus, S.J. The book was printed by the mathematician and surveyor William Leybourn

William Leybourn (16261716) was an English mathematician and land surveyor, author, printer and bookseller.

Career as a printer

During the late 1640s Robert Leybourn's press in Monkswell Street near Cripplegate, London was occupied with books a ...

and distributed by Thomas Dring, an important London bookseller.

''Character Hominis Literati'' 1672

Louis Janin, S.J. (1590–1672) began as a teacher of classical style in France and spent 15 years in Rome as Latin secretary for the French Assistancy at Jesuit headquarters before he returned to Lyons. There he diligently translated five large volumes of Bartoli's Italian Istoria della Compagnia di Gesu between 1665 and 1671. His Latin version of the ''L'huomo di lettere'' appeared in Lyons in 1672. A second printing appeared in Cologne in 1674 "''opusculum docentibus atque ac discentibus utile ac necessarium''". In 1704 this Latin translation was partially reprinted by the Jesuit Faculty of Theology atUniversity of Wroclaw

A university () is an institution of tertiary education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. ''University'' is derived from the Latin phrase , which roughly means "community of teachers and scholars". Univ ...

(Breslau), recently founded by Leopold I, Holy Roman Emperor

Leopold I (Leopold Ignaz Joseph Balthasar Franz Felician; ; 9 June 1640 – 5 May 1705) was Holy Roman Emperor, King of Hungary, List of Croatian monarchs, Croatia, and List of Bohemian monarchs, Bohemia. The second son of Ferdinand III, Holy Rom ...

. It was issued in honor of its first graduates, four new doctors of theology. To Janin's version was added a second translation into Latin by the Lutheran pastor in the service of Frederick I of Prussia

Frederick I (; 11 July 1657 – 25 February 1713), of the Hohenzollern dynasty, was (as Frederick III) List of margraves and electors of Brandenburg, Elector of Brandenburg (1688–1713) and Duke of Prussia in personal union (Brandenburg–Pr ...

in Prussian Kűstrin, Johann Georg Hoffmann, (1648–1719) ''Homo literatus defensus et emendatus''. It was printed in nearby Frankfurt an der Oder

Frankfurt (Oder), also known as Frankfurt an der Oder (, ; Marchian dialects, Central Marchian: ''Frankfort an de Oder,'' ) is the fourth-largest city in the German state of Brandenburg after Potsdam, Cottbus and Brandenburg an der Havel. With a ...

in 1693. His translation was published by Jeremias Schrey The text contains an excellent system of embedded biblical references. Hoffman became a doctor of Sacred Scripture in 1696.

''El Hombre de Letras'' 1678

''El Hombre de Letras'' (Madrid, 1678) provided an excellent Spanish version by the Aragonese priest-musicianGaspar Sanz

Francisco Bartolomé Sanz Celma (April 4, 1640 ( baptized) – 1710), better known as Gaspar Sanz, was a Spanish composer, guitarist, and priest born to a wealthy family in Calanda in the comarca of Bajo Aragón, Spain. He studied music, theo ...

(1640–1710). Studying music in Italy Sanz read Bartoli's well known treatise. He is today more famous for his compositions and ''Instruccion de Musica sobre la Guitarra Espanola''. The guitar pieces by Sanz are still a central part of the guitar repertory and are most familiar through Joaquin Rodgrigo's Fantasia para un gentilhombre

Fantasia may refer to:

Film and television

* ''Fantasia'' (1940 film), an animated musical film produced by Walt Disney

** ''Fantasia 2000'', a sequel to the 1940 film

* ''Fantasia'' (2004 film), a Hong Kong comedy film

* ''Fantasia'' (2014 ...

. Sanz provides Castilian renderings for the extensive Latin quotations in the text and cites the original texts in the margins. This work was reprinted in Barcelona by Juan Jolis in 1744. The title page mentions a Portuguese translation that has not surfaced. It was printed again in a handsome Madrid edition in 1786.

''Een Geletterd Man Verdadigd en Verbeterd'' 1722

Amsterdam's enterprising and productiveman of letters

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and reflection about the nature of reality, especially the nature of society and proposed solutions for its normative problems. Coming from the world of culture, either ...

, Lambert Bidloo (1638–1724) was, like the Ferrarese Bartoli's father, Tiburzio, an apothecary by profession. As a man of letters

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and reflection about the nature of reality, especially the nature of society and proposed solutions for its normative problems. Coming from the world of culture, either ...

he wrote scientific and poetic works in Latin, as well as in Dutch. Bidloo became an active member of Amsterdam's Mennonite

Mennonites are a group of Anabaptism, Anabaptist Christianity, Christian communities tracing their roots to the epoch of the Radical Reformation. The name ''Mennonites'' is derived from the cleric Menno Simons (1496–1561) of Friesland, part of ...

community when it split in two (1664). His Dutch prose works are concerned mostly with defending the more conservative views of his church, called the "Zonists" and led by Samuel Apostool against the more liberal "Lamist" Mennonites led by Galenus Abramsz de Hann. From his youth on he wrote pamphlets against the laxity of his Lamist opponents, tainted with Socinianism

Socinianism ( ) is a Nontrinitarian Christian belief system developed and co-founded during the Protestant Reformation by the Italian Renaissance humanists and theologians Lelio Sozzini and Fausto Sozzini, uncle and nephew, respectively.

...

. In his old age he set to the challenge of translating Bartoli. His rendering of the Italian work has a beautiful frontispiece engraving (perhaps by the young and talented Jacobus Houbraken

Jacobus Houbraken (25 December 1698 – 14 November 1780) was a Dutch engraver and the son of the artist and biographer Arnold Houbraken (1660–1719), whom he assisted in producing a published record of the lives of artists from the Dutch Gol ...

). The title page proposes the defense and bettering of Bartoli's "lettered" man. Even after Bidloo's death in 1724 Hendrik Bosch, his Amsterdam printer, likely a fellow Mennonite

Mennonites are a group of Anabaptism, Anabaptist Christianity, Christian communities tracing their roots to the epoch of the Radical Reformation. The name ''Mennonites'' is derived from the cleric Menno Simons (1496–1561) of Friesland, part of ...

, would continue publishing the works of the learned chemist. The preface of his translation begins with a dedication to his daughter Maria, his faithful "bibliothecaria". He goes on to recall his first introduction to Bartoli's opuscula as a literary nec plus ultra through his acquaintance with Aloysius Bevilacqua who arrived in the Netherlands to represent pope Innocent XI

Pope Innocent XI (; ; 16 May 1611 – 12 August 1689), born Benedetto Odescalchi, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 21 September 1676 until his death on 12 August 1689.

Political and religious tensions with ...

as nuncio

An apostolic nuncio (; also known as a papal nuncio or simply as a nuncio) is an ecclesiastical diplomat, serving as an envoy or a permanent diplomatic representative of the Holy See to a state or to an international organization. A nuncio is ...

at the Congress of Nijmegen (1677/78), seeking peace for the United Provinces against the invading Louis XIV

LouisXIV (Louis-Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was King of France from 1643 until his death in 1715. His verified reign of 72 years and 110 days is the List of longest-reign ...

. As was the custom, the book is decorated with a garland of laudatory poems by noted literary contemporaries, Pieter Langendijk, Jan van Hoogstraten. Matthaeus Brouwerius, et al. Bidloo provides the section headings of the treatise with chapter numbers. Part I, 1–11; Part II, 1-27./ref>

References and Online Links

''The Man of Letters, Defended and Emended'': An Annotated Modern Translation of ''l'Huomo Di Lettere Difeso Et Emendato'' (1645) from Italian and Latin by Gregory Woods. 2018 @Amazon.comWikisource

''Dell'uomo di lettere difeso ed emendato'' The modernized text comes from the complete ''Opere'' (Marietti, Torino) vol. 28, (1834{{DEFAULTSORT:Huomo Di Lettere 1645 books Italian literature Jesuit publications Treatises Works about intelligentsia