KoŇõciuszko Uprising on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The KoŇõciuszko Uprising, also known as the Polish Uprising of 1794 and the Second Polish War, was an uprising against the

The KoŇõciuszko Uprising, also known as the Polish Uprising of 1794 and the Second Polish War, was an uprising against the

On 24 March 1794,

On 24 March 1794,  To destroy the still weak opposition, Russian Empress

To destroy the still weak opposition, Russian Empress  Despite the promise of reforms and quick recruitment of new forces, the strategic situation of the Polish forces, which consisted of 6,000 peasants, cavalry, and 9,000 soldiers, was still critical. On 10 May the forces of

Despite the promise of reforms and quick recruitment of new forces, the strategic situation of the Polish forces, which consisted of 6,000 peasants, cavalry, and 9,000 soldiers, was still critical. On 10 May the forces of  Although the opposition in

Although the opposition in

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

and the Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (german: Königreich Preußen, ) was a German kingdom that constituted the state of Prussia between 1701 and 1918.Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. Re ...

led by Tadeusz KoŇõciuszko

Andrzej Tadeusz Bonawentura KoŇõciuszko ( be, Andr√©j Tad√©vuŇ° Banavient√ļra Kasci√ļŇ°ka, en, Andrew Thaddeus Bonaventure Kosciuszko; 4 or 12 February 174615 October 1817) was a Polish Military engineering, military engineer, statesman, an ...

in the Polish‚ÄďLithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish‚ÄďLithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi-confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Crown of the Kingdom of ...

and the Prussian partition

The Prussian Partition ( pl, Zab√≥r pruski), or Prussian Poland, is the former territories of the Polish‚ÄďLithuanian Commonwealth acquired during the Partitions of Poland, in the late 18th century by the Kingdom of Prussia. The Prussian acquis ...

in 1794. It was a failed attempt to liberate the Polish‚ÄďLithuanian Commonwealth from external influence after the Second Partition of Poland

The 1793 Second Partition of Poland was the second of three partitions (or partial annexations) that ended the existence of the Polish‚ÄďLithuanian Commonwealth by 1795. The second partition occurred in the aftermath of the Polish‚ÄďRussian W ...

(1793) and the creation of the Targowica Confederation

The Targowica Confederation ( pl, konfederacja targowicka, , lt, Targovicos konfederacija) was a confederation established by Polish and Lithuanian magnates on 27 April 1792, in Saint Petersburg, with the backing of the Russian Empress Cather ...

.

Background

Decline of the Commonwealth

By the early 18th century, themagnates of Poland and Lithuania

The magnates of Poland and Lithuania () were an aristocracy of Polish-Lithuanian nobility ('' szlachta'') that existed in the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and, from the 1569 Union of Lublin, in the Polish‚ÄďLit ...

controlled the state ‚Äď or rather, they managed to ensure that no reforms would be carried out that might weaken their privileged status (the "Golden Freedoms

Golden Liberty ( la, Aurea Libertas; pl, ZŇāota WolnoŇõńá, lt, Auksinńó laisvńó), sometimes referred to as Golden Freedoms, Nobles' Democracy or Nobles' Commonwealth ( pl, Rzeczpospolita Szlachecka or ''ZŇāota wolnoŇõńá szlachecka'') was a pol ...

"). Through the abuse of the '' liberum veto'' rule which enabled any deputy to paralyze the Sejm

The Sejm (English: , Polish: ), officially known as the Sejm of the Republic of Poland (Polish: ''Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej''), is the lower house of the bicameral parliament of Poland.

The Sejm has been the highest governing body of t ...

(Commonwealth's parliament) proceedings, deputies bribed by magnates or foreign powers or those simply content to believe they were living in an unprecedented "Golden Age", paralysed the Commonwealth's government for over a century.

The idea of reforming the Commonwealth gained traction starting from the mid-17th century. It was, however, viewed with suspicion not only by its magnates but also by neighboring countries, which were content with the deterioration of the Commonwealth and abhorred the thought of a resurgent and democratic power on their borders. With the Commonwealth Army reduced to around 16,000, it was easy for its neighbors to intervene directly (The Imperial Russian Army

The Imperial Russian Army (russian: –†—ÉŐĀ—Ā—Ā–ļ–į—Ź –ł–ľ–Ņ–Ķ—Ä–įŐĀ—ā–ĺ—Ä—Ā–ļ–į—Ź –įŐĀ—Ä–ľ–ł—Ź, tr. ) was the armed land force of the Russian Empire, active from around 1721 to the Russian Revolution of 1917. In the early 1850s, the Russian Ar ...

numbered 300,000; The Prussian Army and Imperial Austrian Army

The Imperial-Royal or Imperial Austrian Army (german: Kaiserlich-königliche Armee, abbreviation "K.K. Armee") was strictly speaking, the armed force of the Holy Roman Empire under its last monarch, the Habsburg Emperor Francis II, although in r ...

, 200,000 each).

Attempts at reform

A major opportunity for reform presented itself during the "Great Sejm

The Great Sejm, also known as the Four-Year Sejm ( Polish: ''Sejm Wielki'' or ''Sejm Czteroletni''; Lithuanian: ''Didysis seimas'' or ''KetveriŇ≥ metŇ≥ seimas'') was a Sejm (parliament) of the Polish‚ÄďLithuanian Commonwealth that was held in War ...

" of 1788‚Äď92. Poland's neighbors were preoccupied with wars and unable to intervene forcibly in Polish affairs. Russia and Austria were engaged in hostilities with the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, –ěőłŌČőľőĪőĹőĻőļőģ őĎŌÖŌĄőŅőļŌĀőĪŌĄőŅŌĀőĮőĪ, OthŇćmanikńď Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

(the Russo-Turkish War, 1787‚Äď1792 and the Austro-Turkish War, 1787‚Äď1791); the Russians also found themselves simultaneously fighting in the Russo-Swedish War, 1788‚Äď1790. A new alliance between the Polish‚ÄďLithuanian Commonwealth and Prussia seemed to provide security against Russian intervention, and on 3 May 1791 the new constitution was read and adopted to overwhelming popular support.

With the wars between Turkey and Russia and Sweden and Russia having ended, Empress Catherine

, en, Catherine Alexeievna Romanova, link=yes

, house =

, father = Christian August, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst

, mother = Joanna Elisabeth of Holstein-Gottorp

, birth_date =

, birth_name = Princess Sophie of Anhal ...

was furious over the adoption of the new constitution, which she believed threatened Russian influence in Poland. Russia had viewed Poland as a ''de facto'' protectorate. "The worst possible news has arrived from Warsaw: the Polish king has become almost sovereign" was the reaction of one of Russia's chief foreign policy authors, Alexander Bezborodko

Prince Alexander Andreyevich Bezborodko (russian: –ö–Ĺ—Ź–∑—Ć –ź–Ľ–Ķ–ļ—Ā–įŐĀ–Ĺ–ī—Ä –ź–Ĺ–ī—Ä–ĶŐĀ–Ķ–≤–ł—á –Ď–Ķ–∑–Ī–ĺ—Ä–ĺŐĀ–ī–ļ–ĺ; 6 April 1799) was the Grand Chancellor of Russian Empire and chief architect of Catherine the Great's foreign policy aft ...

, when he learned of the new constitution. Prussia was also strongly opposed to the new constitution, and Polish diplomats received a note that the new constitution changed the Polish state so much that Prussia did not consider its obligations binding. Just like Russia, Prussia was concerned that the newly strengthened Polish state could become a threat and the Prussian foreign minister, Friedrich Wilhelm von Schulenburg-Kehnert, clearly and with rare candor told the Poles that Prussia did not support the constitution and refused to help the Commonwealth in any form, even as a mediator, as it was not in Prussia's state interest to see the Commonwealth strengthened as it could threaten Prussia in the future. The Prussian statesman Ewald von Hertzberg

Ewald Friedrich Graf von Hertzberg (2 September 172522 May 1795) was a Prussian statesman.

Early life

Hertzberg, who came of a noble family which had been settled in Pomerania since the 13th century, was born at Lottin (present-day LotyŇĄ, a ...

expressed the fears of European conservatives: "The Poles have given the ''coup de gr√Ęce'' to the Prussian monarchy by voting a constitution", elaborating that a strong Commonwealth would likely demand the return of the lands Prussia acquired in the First Partition.

Second Partition of Poland

The Constitution was not adopted without dissent in the Commonwealth itself, either. Magnates who had opposed the constitution draft from the start, namelyFranciszek Ksawery Branicki

Franciszek Ksawery Branicki (1730‚Äď1819) was a Polish nobleman, magnate, French count, diplomat, politician, military commander, and one of the leaders of the Targowica Confederation. Many consider him to have been a traitor who participated wit ...

, StanisŇāaw Szczńôsny Potocki

Count StanisŇāaw Szczńôsny Feliks Potocki (; 1751‚Äď1805), of the PiŇāawa coat of arms, known as Szczńôsny PotockiE. Rostworowski, Potocki StanisŇāaw Szczńôsny (Feliks) herbu Pilawa, n:Polski SŇāownik Biograficzny, t. XXVIII, WrocŇāaw‚ÄďWarsza ...

, Seweryn Rzewuski

Seweryn Rzewuski (; 13 March 1743 in Podhorce – 11 December 1811 in Vienna) was a Polish nobleman, writer, poet, general of the Royal Army, Field Hetman of the Crown, Voivode of Podolian Voivodeship and one of the leaders of the Targowica ...

, and Szymon Szymon is a Polish version of the masculine given name Simon.

Academics

* Szymon Askenazy ‚Äď a historian and diplomat who served as the first Polish representative at the League of Nations

* Szymon Datner ‚Äď a Polish-Jewish historian and anti-Na ...

and J√≥zef Kossakowski, asked Tsaritsa Catherine to intervene and restore their privileges such as the Russian-guaranteed Cardinal Laws The Cardinal Laws ( pl, Prawa kardynalne) were a quasi-constitution enacted in Warsaw, Polish‚ÄďLithuanian Commonwealth, by the Repnin Sejm of 1767‚Äď68. Enshrining most of the conservative laws responsible for the inefficient functioning of the Co ...

abolished under the new statute. To that end these magnates formed the Targowica Confederation

The Targowica Confederation ( pl, konfederacja targowicka, , lt, Targovicos konfederacija) was a confederation established by Polish and Lithuanian magnates on 27 April 1792, in Saint Petersburg, with the backing of the Russian Empress Cather ...

. The Confederation's proclamation, prepared in St. Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, –°–į–Ĺ–ļ—ā-–ü–Ķ—ā–Ķ—Ä–Ī—É—Ä–≥, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ňąsankt p ≤…™t ≤…™rňąburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914‚Äď1924) and later Leningrad (1924‚Äď1991), i ...

in January 1792, criticized the constitution for contributing to, in their own words, "contagion of democratic ideas" following "the fatal examples set in Paris". It asserted that "The parliament ... has broken all fundamental laws, swept away all liberties of the gentry

Gentry (from Old French ''genterie'', from ''gentil'', "high-born, noble") are "well-born, genteel and well-bred people" of high social class, especially in the past.

Word similar to gentle imple and decentfamilies

''Gentry'', in its widest c ...

and on the third of May 1791 turned into a revolution and a conspiracy." The Confederates declared an intention to overcome this revolution. We "can do nothing but turn trustingly to Tsarina Catherine, a distinguished and fair empress, our neighboring friend and ally", who "respects the nation's need for well-being and always offers it a helping hand", they wrote. The Confederates aligned with Catherine and asked her for military intervention. On 18 May 1792 the Russian ambassador to Poland, Yakov Bulgakov, delivered a declaration of war to Polish Foreign Minister Joachim Chreptowicz

Joachim Chreptowicz pseud.: ''Jeden z wsp√≥Ňāziomk√≥w'' (4 January 1729, Jasieniec near Navahradak ‚Äď 4 March 1812), of OdrowńÖŇľ Coat of Arms, was a Polish-Lithuanian nobleman, writer, poet, politician of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, marshal ...

. Russian armies entered Poland and Lithuania on the same day, starting the Polish‚ÄďRussian War of 1792

The Polish‚ÄďRussian War of 1792 (also, War of the Second Partition, and in Polish sources, War in Defence of the Constitution ) was fought between the Polish‚ÄďLithuanian Commonwealth on one side, and the Targowica Confederation (conservat ...

. The war ended without any decisive battles, with a capitulation signed by Polish King StanisŇāaw August Poniatowski, who hoped that a diplomatic compromise could be worked out.

King Poniatowski's hopes that the capitulation would allow an acceptable diplomatic solution to be worked out were soon dashed. With new deputies bribed or intimidated by the Russian troops, a new session of parliament, known as the Grodno Sejm

Grodno Sejm ( pl, Sejm grodzieŇĄski; be, –ď–į—Ä–į–ī–∑–Ķ–Ĺ—Ā–ļ—Ė —Ā–ĺ–Ļ–ľ; lt, Gardino seimas) was the last Sejm (session of parliament) of the Polish‚ÄďLithuanian Commonwealth. The Grodno Sejm, held in autumn 1793 in Grodno, Grand Duchy of Li ...

, took place, in fall 1793. On 23 November 1793, it concluded its deliberations under duress, annulling the constitution and acceding to the Second Partition. Russia took , while Prussia took of the Commonwealth's territory. This event reduced Poland's population to only one-third of what it was before the partitions began in 1772. The rump state was garrisoned by Russian troops and its independence was strongly curtailed. Such an outcome was a giant blow for the members of the Targowica Confederation

The Targowica Confederation ( pl, konfederacja targowicka, , lt, Targovicos konfederacija) was a confederation established by Polish and Lithuanian magnates on 27 April 1792, in Saint Petersburg, with the backing of the Russian Empress Cather ...

, who saw their actions as a defense of the centuries-old privileges of the magnates, but now were regarded by the majority of the Polish population as traitors.

Growing unrest

The Polish military was widely dissatisfied with the capitulation, most commanders considering it premature;Tadeusz KoŇõciuszko

Andrzej Tadeusz Bonawentura KoŇõciuszko ( be, Andr√©j Tad√©vuŇ° Banavient√ļra Kasci√ļŇ°ka, en, Andrew Thaddeus Bonaventure Kosciuszko; 4 or 12 February 174615 October 1817) was a Polish Military engineering, military engineer, statesman, an ...

, Prince Józef Poniatowski

Prince J√≥zef Antoni Poniatowski (; 7 May 1763 ‚Äď 19 October 1813) was a Polish general, minister of war and army chief, who became a Marshal of the French Empire during the Napoleonic Wars.

A nephew of king Stanislaus Augustus of Poland (), ...

and many others would criticize the king's decision and many, including KoŇõciuszko, resigned their commission shortly afterward. After the Commonwealth defeat in that war and the rescinding of the Constitution, the Army was reduced to about 36,000. In 1794 Russians demanded a further downsizing of the army to 15,000. The dissent in the Polish Army was one of the sparks that would lead to the coming conflict.

The King's capitulation was a hard blow for KoŇõciuszko, who had not lost a single battle in the campaign. By mid September he was resigned to leave the country, and he departed Warsaw in early October. KoŇõciuszko settled in Leipzig

Leipzig ( , ; Upper Saxon: ) is the most populous city in the German state of Saxony. Leipzig's population of 605,407 inhabitants (1.1 million in the larger urban zone) as of 2021 places the city as Germany's eighth most populous, as wel ...

, where many other notable Polish commanders and politicians formed an émigrée community. Soon he and some others began preparing an uprising against Russian rule in Poland. The politicians, grouped around Ignacy Potocki

Count Roman Ignacy Potocki, generally known as Ignacy Potocki (; 1750‚Äď1809), was a Polish nobleman, member of the influential magnate Potocki family, owner of Klementowice and Olesin (near Kur√≥w), a politician, writer, and office holder. H ...

and Hugo KoŇāŇāńÖtaj

Hugo Stumberg KoŇāŇāńÖtaj, also spelled ''KoŇāŇāńÖtay'' (pronounced , 1 April 1750 ‚Äď 28 February 1812), was a prominent Polish constitutional reformer and educationalist, and one of the most prominent figures of the Polish Enlightenment. He s ...

, sought contacts with similar opposition groups formed in Poland and by spring 1793 had been joined by other politicians and revolutionaries, including Ignacy DziaŇāyŇĄski. While KoŇāŇāńÖtaj and others had begun planning for the uprising before meeting KoŇõciuszko, his support was a major boon for them, as he was, at that time, among the most popular individuals in the entire Poland.

In August 1793 KoŇõciuszko returned to Leipzig where he was met with demands to start planning for the uprising; however, he was worried that an uprising would have little chance against the three partitioners. In September he would clandestinely cross the Polish border to conduct personal observations, and to meet some sympathetic high-ranking officers in the remaining Polish Army, including general J√≥zef Wodzicki. The preparations in Poland were slow and he decided to postpone the outbreak, and left for Italy, planning to return in February. However, the situation in Poland was changing rapidly. The Russian and Prussian governments forced Poland to again disband the majority of her armed forces and the reduced units were to be drafted into the Russian army. Also, in March the tsarist agents discovered the group of revolutionaries in Warsaw and started arresting notable Polish politicians and military commanders. KoŇõciuszko was forced to execute his plan earlier than expected, and on 15 March 1794 he set off for Krak√≥w

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 1596 ...

.

On 12 March 1794, General Antoni MadaliŇĄski, the commander of 1st Greater Polish National Cavalry Brigade (1,500 men) decided to disobey the order to demobilise, advancing his troops from OstroŇāńôka

, image_flag = POL OstroŇāńôka flag.svg

, image_shield = POL OstroŇāńôka COA.svg

, pushpin_map = Poland Masovian Voivodeship#Poland

, pushpin_label_position = bottom

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name =

, subdivision_type1 = ...

to Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 1596 ...

.Storozynski, A., 2009, The Peasant Prince, New York: St. Martin's Press, This sparked an outbreak of riots against Russian forces throughout the country. The Russian garrison of Kraków was ordered to leave the city and confront Madalinski, which left Kraków completely undefended, but also foiled Kosciuszko's plan to seize their weapons.

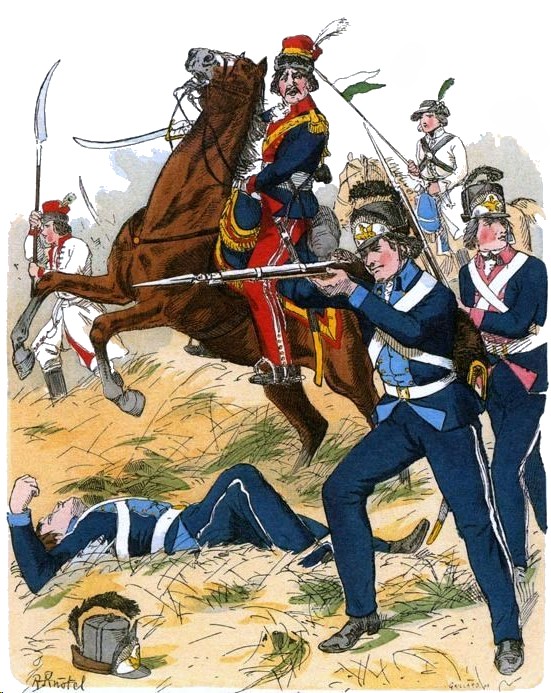

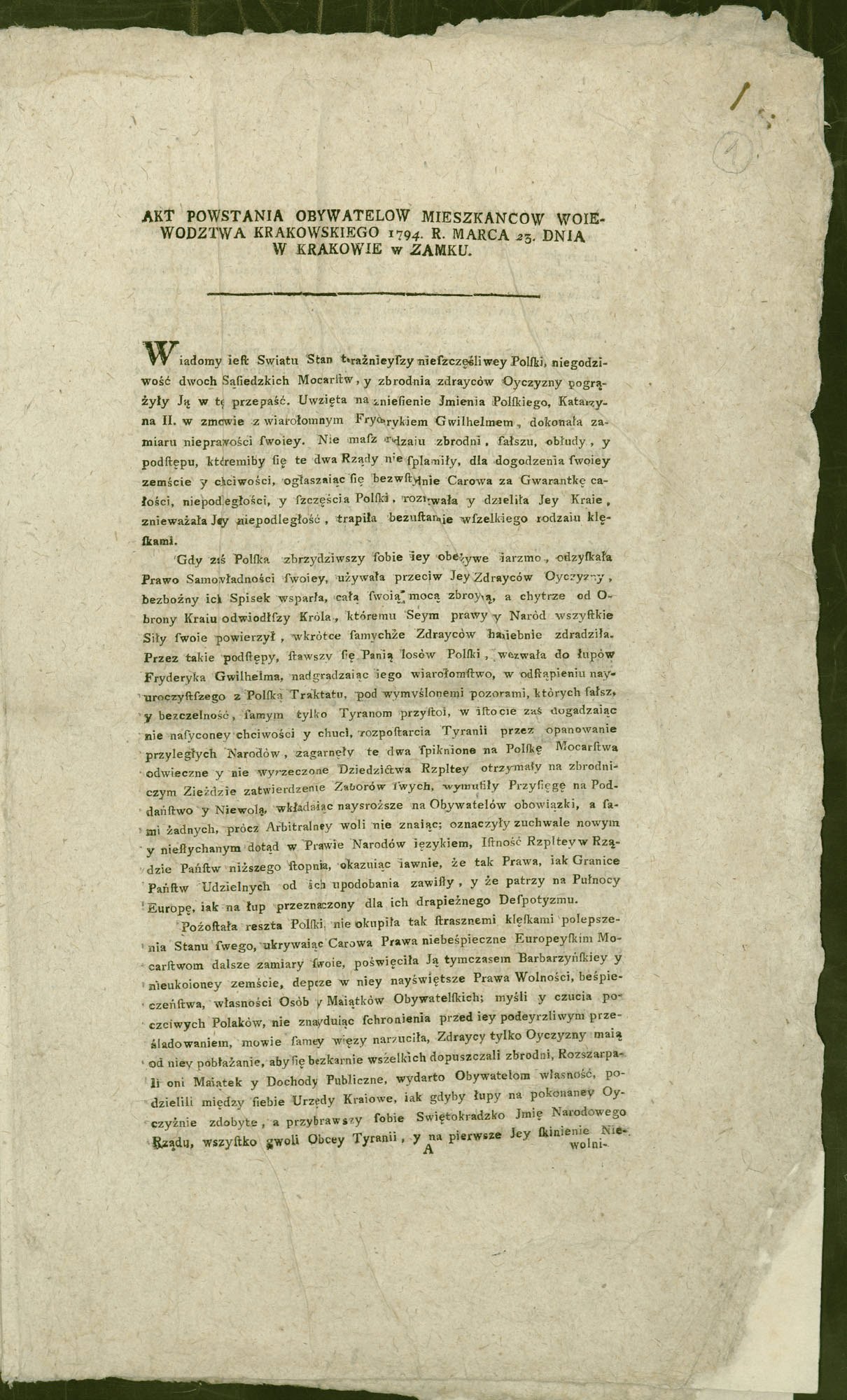

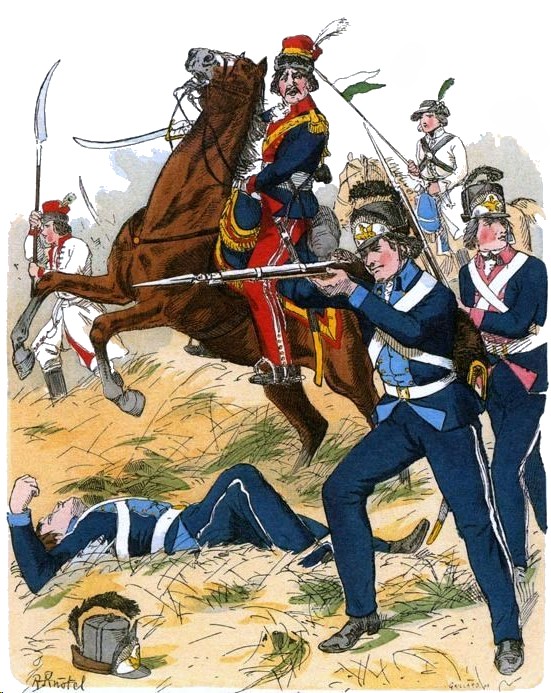

Uprising

On 24 March 1794,

On 24 March 1794, Tadeusz KoŇõciuszko

Andrzej Tadeusz Bonawentura KoŇõciuszko ( be, Andr√©j Tad√©vuŇ° Banavient√ļra Kasci√ļŇ°ka, en, Andrew Thaddeus Bonaventure Kosciuszko; 4 or 12 February 174615 October 1817) was a Polish Military engineering, military engineer, statesman, an ...

, a veteran of the Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

in the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 ‚Äď September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, announced the general uprising in a speech in the Kraków town square and assumed the powers of the Commander in Chief of all of the Polish forces. He also vowed

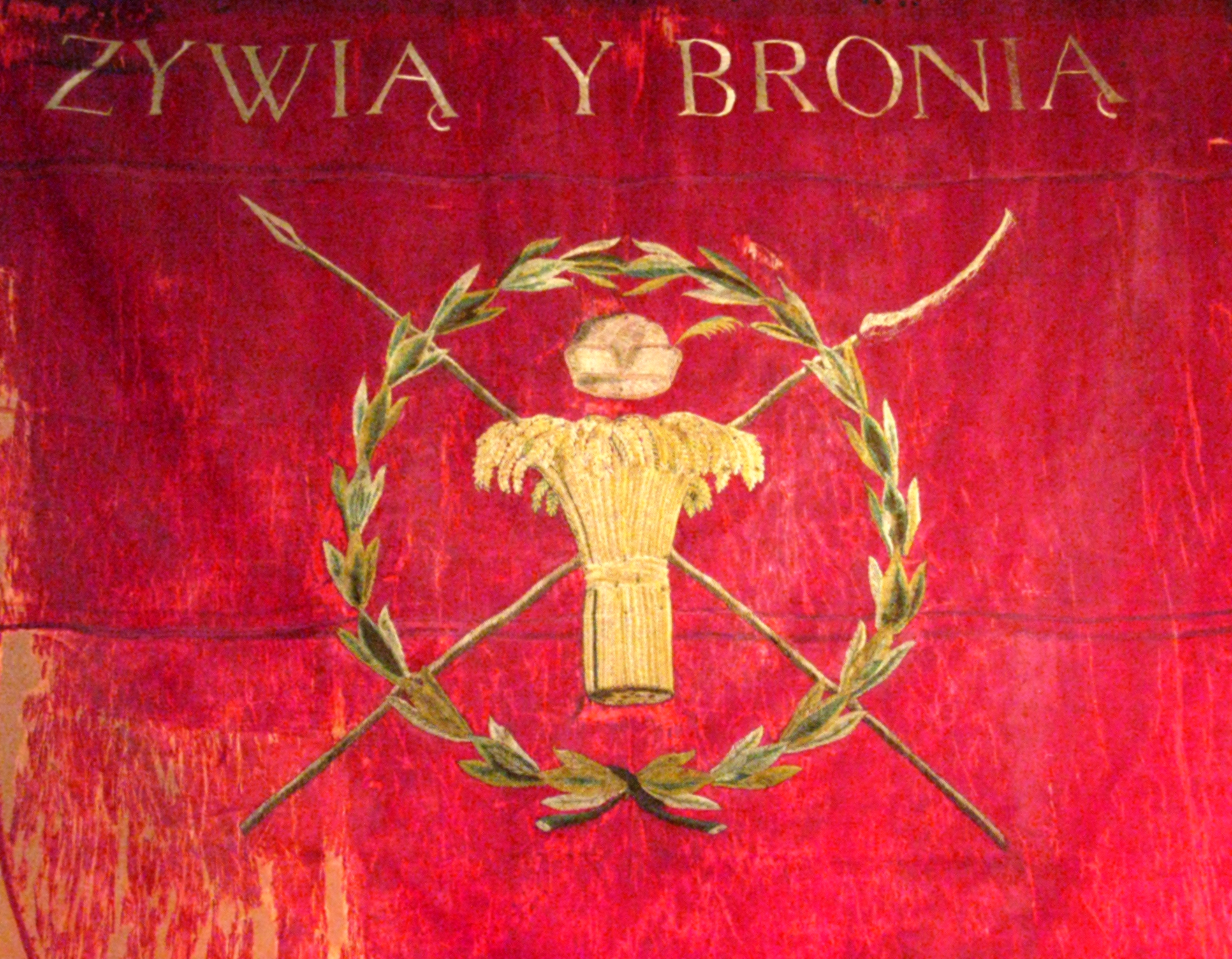

In order to strengthen the Polish forces, KoŇõciuszko issued an act of mobilisation, requiring that every 5 houses in Lesser Poland

Lesser Poland, often known by its Polish name MaŇāopolska ( la, Polonia Minor), is a historical region situated in southern and south-eastern Poland. Its capital and largest city is Krak√≥w. Throughout centuries, Lesser Poland developed a s ...

delegate at least one able male soldier equipped with ''carbine

A carbine ( or ) is a long gun that has a barrel shortened from its original length. Most modern carbines are rifles that are compact versions of a longer rifle or are rifles chambered for less powerful cartridges.

The smaller size and lighte ...

, pike

Pike, Pikes or The Pike may refer to:

Fish

* Blue pike or blue walleye, an extinct color morph of the yellow walleye ''Sander vitreus''

* Ctenoluciidae, the "pike characins", some species of which are commonly known as pikes

* ''Esox'', genus of ...

, or an axe

An axe ( sometimes ax in American English; see spelling differences) is an implement that has been used for millennia to shape, split and cut wood, to harvest timber, as a weapon, and as a ceremonial or heraldic symbol. The axe has ma ...

''. KoŇõciuszko's Commission for Order in Krak√≥w recruited all males between 18 and 28 years of age and passed an income tax. The difficulties with providing enough armament for the mobilised troops made KoŇõciuszko form large units composed of peasants armed with scythe

A scythe ( ) is an agricultural hand tool for mowing grass or harvesting crops. It is historically used to cut down or reap edible grains, before the process of threshing. The scythe has been largely replaced by horse-drawn and then tractor mac ...

s, called the "scythemen".

Catherine the Great

, en, Catherine Alexeievna Romanova, link=yes

, house =

, father = Christian August, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst

, mother = Joanna Elisabeth of Holstein-Gottorp

, birth_date =

, birth_name = Princess Sophie of Anhal ...

ordered the corps of Major General Fiodor Denisov to attack Krak√≥w. On 4 April both armies met near the village of RacŇāawice. In what became known as the Battle of RacŇāawice KoŇõciuszko's forces defeated the numerically and technically superior opponent. After the bloody battle the Russian forces withdrew from the battlefield. KoŇõciuszko's forces were too weak to start a successful pursuit and wipe the Russian forces out of Lesser Poland. Although the strategic importance of the victory was close to none, the news of the victory spread fast and soon other parts of Poland joined the ranks of the revolutionaries. By early April the Polish forces concentrated in the lands of Lublin and Volhynia

Volhynia (also spelled Volynia) ( ; uk, –í–ĺ–Ľ–łŐĀ–Ĺ—Ć, Volyn' pl, WoŇāyŇĄ, russian: –í–ĺ–Ľ—čŐĀ–Ĺ—Ć, Vol√Ĺn Ļ, ), is a historic region in Central and Eastern Europe, between south-eastern Poland, south-western Belarus, and western Ukraine. Th ...

, ready to be sent to Russia, joined the ranks of KoŇõciuszko's forces.

On 17 April in Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officia ...

, the Russian attempt to arrest those suspected of supporting the insurrection and to disarm the weak Polish garrison of Warsaw under Gen. StanisŇāaw Mokronowski

StanisŇāaw Mokronowski (1761-1821) was a prominent member of the Polish landed gentry of Bogoria coat of arms. A general of the Polish Army and a royal Chamberlain Mokronowski took part in both the Polish‚ÄďRussian War of 1792 (War in the Defe ...

by seizing the arsenal at Miodowa

Miodowa (lit. ''Honey Street'') is a street in Warsaw's Old Town. More precisely, it links the Krakowskie (Cracow Suburb) Street in with KrasiŇĄski Square. It is also the name of a street in the Kazimierz district in Krak√≥w.

History

In the ...

Street resulted in an uprising against the Russian garrison of Warsaw, led by Jan KiliŇĄski

Jan KiliŇĄski (1760 in Trzemeszno - 28 January 1819 in Warsaw) was a Polish soldier and one of the commanders of the KoŇõciuszko Uprising. A shoemaker by trade, he commanded the Warsaw Uprising of 1794 against the Russian garrison stationed in W ...

, in the face of indecisiveness of the King of Poland

Poland was ruled at various times either by dukes and princes (10th to 14th centuries) or by kings (11th to 18th centuries). During the latter period, a tradition of free election of monarchs made it a uniquely electable position in Europe (16t ...

, StanisŇāaw II Augustus Stanislav and variants may refer to:

People

*Stanislav (given name), a Slavic given name with many spelling variations (Stanislaus, Stanislas, StanisŇāaw, etc.)

Places

* Stanislav, a coastal village in Kherson, Ukraine

* Stanislaus County, Cali ...

. The insurgents were aided by the incompetence of Russian ambassador and commander, Iosif Igelström, and the chosen day being the Thursday of Holy Week

Holy Week ( la, Hebdomada Sancta or , ; grc, ŠľČő≥őĮőĪ őļőĪŠĹ∂ őúőĶő≥ő¨őĽő∑ Šľôő≤őīőŅőľő¨Ōā, translit=Hagia kai Megale Hebdomas, lit=Holy and Great Week) is the most sacred week in the liturgical year in Christianity. In Eastern Churches, w ...

when many soldiers of the Russian garrison went to the churches for the Eucharist

The Eucharist (; from Greek , , ), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. According to the New Testament, the rite was instit ...

not carrying their arms. Finally, from the onset of the insurrection, the Polish forces were aided by the civilian population and had surprise on their side as they attacked many separate groups of soldiers at the same time and the resistance to Russian forces quickly spread over the city. After two days of heavy fighting the Russians, who suffered between 2,000 and 4,000 casualties out of an initial 5,000 strong garrison, were forced to leave the city. A similar uprising was started by Jakub JasiŇĄski

Jakub Krzysztof JasiŇĄski ( lt, JokŇębas Kristupas Jasinskis) of Rawicz Coat of Arms, Rawicz Clan (24 July 1761, in Wńôglew near Pyzdry in Greater Poland ‚Äď 4 November 1794, in Warsaw, Poland) was a Polish‚ÄďLithuanian Commonwealth, Polish genera ...

in Vilnius

Vilnius ( , ; see also other names) is the capital and largest city of Lithuania, with a population of 592,389 (according to the state register) or 625,107 (according to the municipality of Vilnius). The population of Vilnius's functional urb ...

on 23 April and soon other cities and towns followed. The massacre of unarmed Russian soldiers attending the Easter service was regarded as a "crime against humanity

Crimes against humanity are widespread or systemic acts committed by or on behalf of a ''de facto'' authority, usually a state, that grossly violate human rights. Unlike war crimes, crimes against humanity do not have to take place within the c ...

" by Russians and was a cause of vengeance later, during the siege of Warsaw.: "In every living being our embittered soldiers saw the murderer of our men during the uprising in Warsaw‚Ķ It cost a lot of effort for the Russian officers to save these poor people from the revenge of our soldiers‚Ķ At four o'clock the terrible revenge for the slaughter of our men in Warsaw was complete!‚ÄĚ: "During the assault on Praga the rage of our troops, who were burning with revenge for the treacherous slaughter of our comrades by the Poles, reached extreme limits‚ÄĚ.

On 7 May 1794, KoŇõciuszko issued an act that became known as the "Proclamation of PoŇāaniec

The Proclamation of PoŇāaniec (also known as the PoŇāaniec Manifesto; pl, UniwersaŇā PoŇāaniecki), issued on 7 May 1794 by Tadeusz KoŇõciuszko near the town of PoŇāaniec, was one of the most notable events of Poland's KoŇõciuszko Uprising, and th ...

", in which he partially abolished serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which develop ...

in Poland, granted civil liberty

Civil liberties are guarantees and freedoms that governments commit not to abridge, either by constitution, legislation, or judicial interpretation, without due process. Though the scope of the term differs between countries, civil liberties ma ...

to all peasants and provided them with state help against abuses by the nobility. Although the new law never fully came into being and was boycotted by much of the nobility, it also attracted many peasants to the ranks of the revolutionaries. It was the first time in Polish history that the peasants were officially regarded as part of the ''nation

A nation is a community of people formed on the basis of a combination of shared features such as language, history, ethnicity, culture and/or society. A nation is thus the collective identity of a group of people understood as defined by those ...

'', the word being previously equivalent to ''nobility''.

Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''PrŇęsa'' or ''PrŇęsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

(17,500 soldiers under General Francis Favrat), crossed the Polish borders and joined the 9,000 Russian soldiers operating in northern Poland. On 6 June KoŇõciuszko was defeated in the Battle of Szczekociny

The Battle of Szczekociny was fought on the 6 June 1794 near the town of Szczekociny, Lesser Poland, between Poland and the combined forces of the Russian Empire and Kingdom of Prussia. Polish forces were led by Tadeusz KoŇõciuszko, and the Russ ...

by a joint Russo-Prussian force and on 8 June General J√≥zef ZajńÖczek

Prince J√≥zef ZajńÖczek (; 1 November 1752 ‚Äď 28 August 1826) was a Polish general and politician.

ZajńÖczek started his career in the Army of the Polish‚ÄďLithuanian Commonwealth, an aide-de-camp to hetman Franciszek Ksawery Branicki. He ...

was defeated in the Battle of CheŇām. Polish forces withdrew towards Warsaw and started to fortify the city under directions from Kosciuszko and his 16,000 soldiers, 18,000 peasants and 15,000 burghers. On 15 June the Prussian army captured Krak√≥w unopposed. Warsaw was besieged

Besieged may refer to:

* the state of being under siege

* ''Besieged'' (film), a 1998 film by Bernardo Bertolucci

{{disambiguation ...

by 41,000 Russians under General Ivan Fersen and 25,000 Prussians under King Frederick William II of Prussia

Frederick William II (german: Friedrich Wilhelm II.; 25 September 1744 ‚Äď 16 November 1797) was King of Prussia from 1786 until his death in 1797. He was in personal union the Prince-elector of Brandenburg and (via the Orange-Nassau inherita ...

on 13 July. On 20 August, an uprising in Greater Poland

Greater Poland, often known by its Polish name Wielkopolska (; german: Gro√üpolen, sv, Storpolen, la, Polonia Maior), is a Polish historical regions, historical region of west-central Poland. Its chief and largest city is PoznaŇĄ followed ...

started and the Prussians were forced to withdraw their forces from Warsaw. The siege was lifted by 6 September when the Prussians and Russians had both withdrawn their troops.

Lithuania

Lithuania (; lt, Lietuva ), officially the Republic of Lithuania ( lt, Lietuvos Respublika, links=no ), is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. Lithuania ...

was crushed by Russian forces ( Vilnius was besieged and capitulated on 12 August), the uprising in Greater Poland achieved some success. A Polish corps under Jan Henryk DńÖbrowski

Jan Henryk DńÖbrowski (; also known as Johann Heinrich DńÖbrowski (Dombrowski) in German and Jean Henri Dombrowski in French; 2 August 1755 ‚Äď 6 June 1818) was a Polish general and statesman, widely respected after his death for his patri ...

captured Bydgoszcz

Bydgoszcz ( , , ; german: Bromberg) is a city in northern Poland, straddling the meeting of the River Vistula with its left-bank tributary, the Brda. With a city population of 339,053 as of December 2021 and an urban agglomeration with more ...

(2 October) and entered Pomerania

Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze; german: Pommern; Kashubian: ''P√≤m√≤rsk√ī''; sv, Pommern) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The western part of Pomerania belongs to ...

almost unopposed. Thanks to the mobility of his forces, General DńÖbrowski evaded being encircled by a much less mobile Prussian army and disrupted the Prussian lines, forcing the Prussians to withdraw most of their forces from central Poland. However, the Poles did not stay long in Prussian territories, and soon retreated to Central Poland.

Meanwhile, the Russians equipped a new corps commanded by General Aleksandr Suvorov

Alexander Vasilyevich Suvorov (russian: –ź–Ľ–Ķ–ļ—Ā–įŐĀ–Ĺ–ī—Ä –í–į—Ā–łŐĀ–Ľ—Ć–Ķ–≤–ł—á –°—É–≤–ĺŐĀ—Ä–ĺ–≤, Aleks√°ndr Vas√≠l'yevich Suv√≥rov; or 1730) was a Russian general in service of the Russian Empire. He was Count of Rymnik, Count of the Holy ...

and ordered it to join up with the corps under Ivan Fersen near Warsaw. After the Battle of Krupczyce (17 September) and the Battle of Terespol

The Battle of Brest, also known as the Battle of Terespol, was a battle between Russian imperial forces and Polish rebels south-west of Brest (near the village of Terespol), present-day Belarus, on 19 September 1794. It was part of the KoŇõcius ...

(19 September), the new army started its march towards Warsaw. Trying to prevent both Russian armies from joining up, KoŇõciuszko mobilised two regiments from Warsaw and with General Sierakowski's 5,000 soldiers, engaged Fersen's force of 14,000 on 10 October in the Battle of Maciejowice

The Battle of Maciejowice was fought on 10 October 1794, between Poland and the Russian Empire.

The Poles were led by Tadeusz KoŇõciuszko. KoŇõciuszko with 6,200 men, who planned to prevent the linking of three larger Russian corps, commanded b ...

. KoŇõciuszko was wounded in the battle and was captured by the Russians, who sent him to Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, –°–į–Ĺ–ļ—ā-–ü–Ķ—ā–Ķ—Ä–Ī—É—Ä–≥, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ňąsankt p ≤…™t ≤…™rňąburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914‚Äď1924) and later Leningrad (1924‚Äď1991), i ...

.

The new commander of the uprising, Tomasz Wawrzecki, could not control the spreading internal struggles for power and ultimately became only the commander of weakened military forces, while the political power was held by General J√≥zef ZajńÖczek

Prince J√≥zef ZajńÖczek (; 1 November 1752 ‚Äď 28 August 1826) was a Polish general and politician.

ZajńÖczek started his career in the Army of the Polish‚ÄďLithuanian Commonwealth, an aide-de-camp to hetman Franciszek Ksawery Branicki. He ...

, who in turn had to struggle with both the leftist liberal Polish Jacobins

Polish Jacobins (or Huguenots) was the name given to a group of late 18th century radical Polish politicians by their opponents.

Polish Jacobins formed during the Great Sejm as an offshoot of the "KoŇāŇāńÖtaj's Forge" (''KuŇļnia KoŇāŇāńÖtajska'') ...

and the rightist and monarchical nobility.

On 4 November the joint Russian forces started the Battle of Praga

The Battle of Praga or the Second Battle of Warsaw of 1794 was a Russian assault on Praga, the easternmost suburb of Warsaw, during the KoŇõciuszko Uprising in 1794. It was followed by a massacre (known as the Massacre of Praga) of the civilia ...

, after the name of the right-bank suburb of Warsaw where it took place. After four hours of brutal hand-to-hand fighting, the 22,000-strong Russian forces broke through the Polish defences and Suvorov allowed his Cossacks to loot and burn Warsaw. Approximately 20,000 were murdered in the Praga massacre. Zajaczek fled wounded, abandoning the Polish army.

On 16 November, near Radoszyce, Wawrzecki surrendered. This marked the end of the uprising. The power of Poland was broken and the following year the third partition of Poland

The Third Partition of Poland (1795) was the last in a series of the Partitions of Poland‚ÄďLithuania and the land of the Polish‚ÄďLithuanian Commonwealth among Prussia, the Habsburg monarchy, and the Russian Empire which effectively ended Polish ...

took place, after which Austria

Austria, , bar, √Ėstareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

, Russia and Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''PrŇęsa'' or ''PrŇęsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

annexed the remainder of the country.

Aftermath

After the failure of the KoŇõciuszko Uprising, Poland ceased to exist for 123 years, and all of its institutions were gradually banned by the partitioning powers. However, the uprising also marked the start of modern political thought in Poland andCentral Europe

Central Europe is an area of Europe between Western Europe and Eastern Europe, based on a common historical, social and cultural identity. The Thirty Years' War (1618‚Äď1648) between Catholicism and Protestantism significantly shaped the area' ...

. KoŇõciuszko's Proclamation of PoŇāaniec

The Proclamation of PoŇāaniec (also known as the PoŇāaniec Manifesto; pl, UniwersaŇā PoŇāaniecki), issued on 7 May 1794 by Tadeusz KoŇõciuszko near the town of PoŇāaniec, was one of the most notable events of Poland's KoŇõciuszko Uprising, and th ...

and the radical leftist Jacobins

, logo = JacobinVignette03.jpg

, logo_size = 180px

, logo_caption = Seal of the Jacobin Club (1792‚Äď1794)

, motto = "Live free or die"(french: Vivre libre ou mourir)

, successor = Pa ...

started the Polish leftist movement. Many prominent Polish politicians who were active during the uprising became the backbone of Polish politics, both at home and abroad, in the 19th century. Also, Prussia had much of its forces tied up in Poland and could not field enough forces to suppress the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

, which added to its success and briefly restored a Polish state.

In the lands of partitioned Poland, the failure of the uprising meant economic catastrophe, as centuries-old economic market

Market is a term used to describe concepts such as:

*Market (economics), system in which parties engage in transactions according to supply and demand

*Market economy

*Marketplace, a physical marketplace or public market

Geography

*Märket, an ...

s became divided and separated from each other, resulting in the collapse of trade

Trade involves the transfer of goods and services from one person or entity to another, often in exchange for money. Economists refer to a system or network that allows trade as a market.

An early form of trade, barter, saw the direct excha ...

. Several bank

A bank is a financial institution that accepts deposits from the public and creates a demand deposit while simultaneously making loans. Lending activities can be directly performed by the bank or indirectly through capital markets.

Because ...

s fell and some of the few manufacturing centres established in the Commonwealth were closed. Reforms made by the reformers and Kosciuszko, aimed at easing serfdom, were revoked. All the partitioning powers heavily taxed their newly acquired lands, filling their treasuries at the expense of the local population.

The schooling system was also degraded as the schools in those territories were given low priority. The Commission of National Education

The Commission of National Education ( pl, Komisja Edukacji Narodowej, KEN; lt, Edukacinńó komisija) was the central educational authority in the Polish‚ÄďLithuanian Commonwealth, created by the Sejm and King StanisŇāaw II August on October 14 ...

, the world's first Ministry of Education, was abolished, because the absolutist governments of the partitioning powers saw no gain in investing in education in the territories inhabited by restless Polish minorities. The creation of educational institutions in the partitions became very difficult. For example, an attempt to create a university in Warsaw was opposed by the Prussian authorities. Further, in the German and Russian partitions, all remaining centers of learning were subject to Germanisation

Germanisation, or Germanization, is the spread of the German language, German people, people and German culture, culture. It was a central idea of German conservative thought in the 19th and the 20th centuries, when conservatism and ethnic nationa ...

and Russification

Russification (russian: —Ä—É—Ā–ł—Ą–ł–ļ–į—Ü–ł—Ź, rusifikatsiya), or Russianization, is a form of cultural assimilation in which non-Russians, whether involuntarily or voluntarily, give up their culture and language in favor of the Russian cultur ...

; only in territories acquired by Austria was there relatively little governmental intervention in the curriculum

In education, a curriculum (; : curricula or curriculums) is broadly defined as the totality of student experiences that occur in the educational process. The term often refers specifically to a planned sequence of instruction, or to a view ...

. According to S. I. NikoŇāajew, from the cultural point of view the partitions may have given a step forward towards the development of national Polish literature

Polish literature is the literary tradition of Poland. Most Polish literature has been written in the Polish language, though other languages used in Poland over the centuries have also contributed to Polish literary traditions, including Latin, ...

and arts, since the inhabitants of partitioned lands could acquire the cultural developments of German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

and Russian Enlightenment

The Russian Age of Enlightenment was a period in the 18th century in which the government began to actively encourage the proliferation of arts and sciences, which had a profound impact on Russian culture. During this time, the first Russian unive ...

.NikoŇāajew, S. I. Od Kochanowskiego do Mickiewicza. Szkice z historii polsko-rosyjskich zwińÖzk√≥w literackich XVII‚ÄďXIX wieku / TŇāum. J. GŇāaŇľewski. Warszawa: Neriton, 2007. 319 s. (Nauka o Literaturze Polskiej za GranicńÖ, t. X)

The conditions for the former Polish elite were particularly harsh in Russian partition. Thousands of Polish ''szlachta'' families who supported KoŇõciuszo's uprising were stripped of their possessions and estates, which were awarded to Russian generals and favourites of the St. Petersburg court. It is estimated that 650,000 former Polish serfs were transferred to Russian officials in this manner. Some among the nobility, especially in Lithuanian and Ruthenia

Ruthenia or , uk, –†—É—ā–Ķ–Ĺ—Ė—Ź, translit=Rutenia or uk, –†—É—Ā—Ć, translit=Rus, label=none, pl, RuŇõ, be, –†—É—ā—ć–Ĺ—Ė—Ź, –†—É—Ā—Ć, russian: –†—É—ā–Ķ–Ĺ–ł—Ź, –†—É—Ā—Ć is an exonym, originally used in Medieval Latin as one of several terms ...

n regions of the former Commonwealth, were expelled to southern Russia, where they were subject to Russification. Other nobles were denied their nobility status by Russian authorities, which meant loss of legal privileges and social status

Social status is the level of social value a person is considered to possess. More specifically, it refers to the relative level of respect, honour, assumed competence, and deference accorded to people, groups, and organizations in a society. Stat ...

, significantly limiting any possibility of a career in administration or the military - the traditional career paths of Polish nobles. It also meant that they could not own any land, another blow to their former noble status. But for Orthodox Christian

Orthodoxy (from Greek: ) is adherence to correct or accepted creeds, especially in religion.

Orthodoxy within Christianity refers to acceptance of the doctrines defined by various creeds and ecumenical councils in Antiquity, but different Churche ...

peasants of Western Ukraine

Western Ukraine or West Ukraine ( uk, –ó–į—Ö—Ė–ī–Ĺ–į –£–ļ—Ä–į—ó–Ĺ–į, Zakhidna Ukraina or , ) is the territory of Ukraine linked to the former Kingdom of Galicia‚ÄďVolhynia, which was part of the Polish‚ÄďLithuanian Commonwealth, the Austria ...

and Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, –†–Ķ—Ā–Ņ—É–Ī–Ľ–ł–ļ–į –Ď–Ķ–Ľ–į—Ä—É—Ā—Ć, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by R ...

, the partition may have brought the decline of religious oppression by their formal lords, followers of Roman Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwide . It is am ...

.

However, Orthodox Christians were only a small minority in Eastern Belarus at that time; the prevailing majority of the country's population was Eastern rite Catholics. Peasants were flogged

Flagellation (Latin , 'whip'), flogging or whipping is the act of beating the human body with special implements such as whips, Birching, rods, Switch (rod), switches, the cat o' nine tails, the sjambok, the knout, etc. Typically, flogging ...

just for mentioning the name of KoŇõciuszko and his idea of abolishing serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which develop ...

. Platon Zubov

Prince Platon Alexandrovich Zubov (russian: –ü–Ľ–į—ā–ĺ–Ĺ –ź–Ľ–Ķ–ļ—Ā–į–Ĺ–ī—Ä–ĺ–≤–ł—á –ó—É–Ī–ĺ–≤; ) was the last of Catherine the Great's favourites and the most powerful man in the Russian Empire during the last years of her reign.

Life

The princ ...

, who was awarded estates in Lithuania, was especially infamous, as he personally tortured to death many peasants who complained about worsening conditions. Besides this, the Russian authorities conducted heavy recruiting for the Russian army

The Russian Ground Forces (russian: –°—É—Ö–ĺ–Ņ—É—ā–Ĺ—č–Ķ –≤–ĺ–Ļ—Ā–ļ–į ÔŅĹ–í Sukhoputnyye voyska V, also known as the Russian Army (, ), are the Army, land forces of the Russian Armed Forces.

The primary responsibilities of the Russian Gro ...

among the population, which meant a practically lifelong service. Since the conditions of serfdom in former Poland due to the exploitation by nobility and arendator

In the history of the Russian Empire, and Polish‚ÄďLithuanian Commonwealth, arendator (literally "lease holder") (, ) was a person who leased fixed assets, such as land, mills, inns, breweries, or distilleries, or of special rights, such as the r ...

s were already severe, discussion exists on how partitions influenced the life of common people.

See also

* Supreme National Council *Polish Uprisings

This is a chronological list of military conflicts in which Polish armed forces fought or took place on Polish territory from the reign of Mieszko I (960‚Äď992) to the ongoing military operations.

This list does not include peacekeeping operation ...

* Battle of Praga

The Battle of Praga or the Second Battle of Warsaw of 1794 was a Russian assault on Praga, the easternmost suburb of Warsaw, during the KoŇõciuszko Uprising in 1794. It was followed by a massacre (known as the Massacre of Praga) of the civilia ...

* the painting ''RacŇāawice Panorama

The ''RacŇāawice Panorama'' (Polish: ''Panorama RacŇāawicka'') is a monumental (15 √ó 114 meter) cycloramic painting depicting the Battle of RacŇāawice, during the KoŇõciuszko Uprising. It is located in WrocŇāaw, Poland. The painting is one of ...

''

Notes

References

External links

{{DEFAULTSORT:Kosciuszko Uprising Resistance to the Russian Empire Conflicts in 1794 Tadeusz KoŇõciuszko 1794 in the Polish‚ÄďLithuanian Commonwealth Polish‚ÄďLithuanian Commonwealth‚ÄďRussian Empire relations