King Christian IV on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Christian IV (12 April 1577 – 28 February 1648) was

Christian was born at

Christian was born at

At the death of his father on 4 April 1588, Christian was just 10 years old. He succeeded to the throne, but as he was still under-age a

At the death of his father on 4 April 1588, Christian was just 10 years old. He succeeded to the throne, but as he was still under-age a

Christian took an interest in many and varied matters, including a series of domestic reforms and improving Danish national armaments. New fortresses were constructed under the direction of

Christian took an interest in many and varied matters, including a series of domestic reforms and improving Danish national armaments. New fortresses were constructed under the direction of

In 1618, Christian appointed Admiral

In 1618, Christian appointed Admiral

Christian IV had obtained for his kingdom a level of stability and wealth that was virtually unmatched elsewhere in Europe. Denmark was funded by tolls on the

Christian IV had obtained for his kingdom a level of stability and wealth that was virtually unmatched elsewhere in Europe. Denmark was funded by tolls on the

Sweden was able, thanks to their conquests in the Thirty Years' War, to attack Denmark from the south as well as the east; the Dutch alliance promised to secure them at sea. In May 1643 the Swedish

Sweden was able, thanks to their conquests in the Thirty Years' War, to attack Denmark from the south as well as the east; the Dutch alliance promised to secure them at sea. In May 1643 the Swedish

After the Torstenson War, ''Rigsrådet'' took on an increasing role, under the leadership of

After the Torstenson War, ''Rigsrådet'' took on an increasing role, under the leadership of

His first queen was Anne Catherine of Brandenburg, Anne Catherine. They were married from 1597 to 1612. She died after bearing Christian seven children. In 1615, three years after her death, the king privately married Kirsten Munk, by whom he had twelve children.

In 1632, an English envoy to king Christian IV, then aged 55, primly remarked "Such is the life of that king: to drink all day and to lie with a whore every night".

In the course of 1628, he discovered that his wife, Kirsten Munk, was having a relationship with one of his German officers. Christian had Munk placed under house arrest. She endeavoured to cover up her own disgrace by conniving at an intrigue between Vibeke Kruse, one of her discharged maids, and the king. In January 1630, the rupture became final and Kirsten retired to her estates in

His first queen was Anne Catherine of Brandenburg, Anne Catherine. They were married from 1597 to 1612. She died after bearing Christian seven children. In 1615, three years after her death, the king privately married Kirsten Munk, by whom he had twelve children.

In 1632, an English envoy to king Christian IV, then aged 55, primly remarked "Such is the life of that king: to drink all day and to lie with a whore every night".

In the course of 1628, he discovered that his wife, Kirsten Munk, was having a relationship with one of his German officers. Christian had Munk placed under house arrest. She endeavoured to cover up her own disgrace by conniving at an intrigue between Vibeke Kruse, one of her discharged maids, and the king. In January 1630, the rupture became final and Kirsten retired to her estates in  With his second wife, Kirsten Munk, he had 12 children, though the youngest, Dorothea Elisabeth, was rumoured to be the daughter of Kirsten's lover, Otto Ludwig:

*Stillborn child (b. & d. 1615).

*Unnamed infant (b. & d. 1617).

*Countess Anna Cathrine of Schleswig-Holstein (10 August 1618 – 20 August 1633); married Frands Rantzau.

*Sophie Elisabeth Pentz, Countess Sophie Elisabeth of Schleswig-Holstein (20 September 1619 – 29 April 1657); married Christian on Pentz.

*Leonora Christina Ulfeldt, Countess Leonora Christina of Schleswig-Holstein (8 July 1621 – 16 March 1698); married

With his second wife, Kirsten Munk, he had 12 children, though the youngest, Dorothea Elisabeth, was rumoured to be the daughter of Kirsten's lover, Otto Ludwig:

*Stillborn child (b. & d. 1615).

*Unnamed infant (b. & d. 1617).

*Countess Anna Cathrine of Schleswig-Holstein (10 August 1618 – 20 August 1633); married Frands Rantzau.

*Sophie Elisabeth Pentz, Countess Sophie Elisabeth of Schleswig-Holstein (20 September 1619 – 29 April 1657); married Christian on Pentz.

*Leonora Christina Ulfeldt, Countess Leonora Christina of Schleswig-Holstein (8 July 1621 – 16 March 1698); married

File:Christian IV av CL Jacobsen 2.jpg, Statue of King Christian IV in Oslo

File:Kr-iv-ks ubt.jpeg, Statue of Christian IV in Kristiansand

File:Nyboder 2005-03.jpg, Statue of Christian IV in Copenhagen

File:Frederiksborg slot - Interior 20090818 03.jpg , Bust of Christian IV at Frederiksborg Castle

File:Kong Christian Den Fjerde i Roskilde Domkirke.jpg, Sculpture by Christian IV in Roskilde Cathedral by Bertel Thorvaldsen

File:Chr IV rådhuset Kristianstad.jpg, Statue of Christian IV at the city hall in Kristianstad by Bertel Thorvaldsen

File:Kungamöte-2.JPG, Sculpture of Christian IV meeting the king of Sweden, Gustav II Adolf in Halmstad

Treaty of Bremen

. In Davenport, Frances G. ''European Treaties Bearing on the History of the United States and Its Dependencies''. The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd., 2004.

The Royal Lineage

at the website of the Danish Monarchy

Christian IV

at the website of the Royal Danish Collection *

Harington's account of the drunken masque.

{{Authority control Christian IV of Denmark, 1577 births 1648 deaths 16th-century monarchs of Denmark 17th-century monarchs of Denmark 16th-century Norwegian monarchs 17th-century Norwegian monarchs People from Hillerød Municipality Dukes of Schleswig Dukes of Holstein Denmark–Norway Danish people of the Thirty Years' War Burials at Roskilde Cathedral Extra Knights Companion of the Garter People of the Kalmar War Children of Frederick II of Denmark

King of Denmark

The monarchy of Denmark is a constitutional political system, institution and a historic office of the Kingdom of Denmark. The Kingdom includes Denmark proper and the autonomous administrative division, autonomous territories of the Faroe ...

and Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and t ...

and Duke of Holstein and Schleswig from 1588 until his death in 1648. His reign of 59 years, 330 days is the longest of Danish monarchs

This is a list of Danish monarchs, that is, the kings and queens regnant of Denmark. This includes:

* The Kingdom of Denmark (up to 1397)

** Personal union of Denmark and Norway (1380–1397)

* The Kalmar Union (1397–1536)

** Union of Denmark ...

and Scandinavian monarchies.

A member of the House of Oldenburg

The House of Oldenburg is a Germans, German dynasty with links to Denmark since the 15th century. It has branches that rule or have ruled in Denmark, Iceland, Greece, Norway, Russia, Sweden, the United Kingdom, Duchy of Schleswig, Schleswig, Duchy ...

, Christian began his personal rule of Denmark in 1596 at the age of 19. He is remembered as one of the most popular, ambitious, and proactive Danish kings, having initiated many reforms and projects. Christian IV obtained for his kingdom a level of stability and wealth that was virtually unmatched elsewhere in Europe. He engaged Denmark in numerous wars, most notably the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (80 ...

(1618–1648), which devastated much of Germany, undermined the Danish economy, and cost Denmark some of its conquered territories.

He rebuilt and renamed the Norwegian capital Oslo

Oslo ( , , or ; sma, Oslove) is the capital and most populous city of Norway. It constitutes both a county and a municipality. The municipality of Oslo had a population of in 2022, while the city's greater urban area had a population of ...

as ''Christiania'' after himself, a name used until 1925.

Early years

Birth and family

Christian was born at

Christian was born at Frederiksborg Castle

Frederiksborg Castle ( da, Frederiksborg Slot) is a palatial complex in Hillerød, Denmark. It was built as a royal residence for King Christian IV of Denmark-Norway in the early 17th century, replacing an older castle acquired by Frederick II ...

in Denmark on 12 April 1577 as the third child and eldest son of King Frederick II of Denmark–Norway

Denmark–Norway (Danish and Norwegian: ) was an early modern multi-national and multi-lingual real unionFeldbæk 1998:11 consisting of the Kingdom of Denmark, the Kingdom of Norway (including the then Norwegian overseas possessions: the Faroe I ...

and Sofie of Mecklenburg-Schwerin

Sophia means "wisdom" in Greek. It may refer to:

*Sophia (wisdom)

*Sophia (Gnosticism)

* Sophia (given name)

Places

* Niulakita or Sophia, an island of Tuvalu

* Sophia, Georgetown, a ward of Georgetown, Guyana

* Sophia, North Carolina, an uninco ...

. He was descended, through his mother's side, from king John of Denmark

John (Danish, Norwegian and sv, Hans; né ''Johannes'') (2 February 1455 – 20 February 1513) was a Scandinavian monarch under the Kalmar Union. He was king of Denmark (1481–1513), Norway (1483–1513) and as John II ( sv, Johan II) ...

, and was thus the first descendant of King John to assume the crown since the deposition of King Christian II

Christian II (1 July 1481 – 25 January 1559) was a Scandinavian monarch under the Kalmar Union who reigned as King of Denmark and Norway, from 1513 until 1523, and Sweden from 1520 until 1521. From 1513 to 1523, he was concurrently Duke ...

.

At the time, Denmark was still an elective monarchy

An elective monarchy is a monarchy ruled by an elected monarch, in contrast to a hereditary monarchy in which the office is automatically passed down as a family inheritance. The manner of election, the nature of candidate qualifications, and the ...

, so in spite of being the eldest son Christian was not automatically heir to the throne. But Norway was an hereditary monarchy

A hereditary monarchy is a form of government and succession of power in which the throne passes from one member of a ruling family to another member of the same family. A series of rulers from the same family would constitute a dynasty.

It is h ...

, and electing someone else would result in the end of the union of the crowns

The Union of the Crowns ( gd, Aonadh nan Crùintean; sco, Union o the Crouns) was the accession of James VI of Scotland to the throne of the Kingdom of England as James I and the practical unification of some functions (such as overseas dip ...

. However, in 1580, at the age of 3, his father had him elected Prince and successor to the throne of Denmark.

Young king

At the death of his father on 4 April 1588, Christian was just 10 years old. He succeeded to the throne, but as he was still under-age a

At the death of his father on 4 April 1588, Christian was just 10 years old. He succeeded to the throne, but as he was still under-age a regency council

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state ''pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy, ...

was set up to serve as the trustees of the royal power while Christian was still growing up. It was led by chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

Niels Kaas

Niels Kaas (1535 – 29 June 1594) was a Danish politician who served as Chancellor of Denmark from 1573 until his death. He was influential in the negotiation of the Treaty of Stettin (1570), Peace of Stettin and in the upbringing of Christian ...

and consisted of the '' Rigsraadet'' council members Peder Munk

Peder Munk of Estvadgård (1534–1623), was a Danish navigator, politician, and ambassador, who was in charge of the fleet carrying Anne of Denmark to Scotland. The events of the voyage led to witch trials and executions in Denmark and Scotland ...

(1534–1623), Jørgen Ottesen Rosenkrantz (1523–1596) and Christoffer Valkendorff

Christoffer Valkendorff (1 September 152517 January 1601) was a Danish-Norwegian statesman and landowner. His early years in the service of Frederick II brought him both to Norway, Ösel and Livland. He later served both as Treasurer and ''Stadth ...

(1525-1601). His mother Queen Dowager Sophie, 30 years old, had wished to play a role in the government, but was denied by the council. At the death of Niels Kaas in 1594, Jørgen Rosenkrantz took over leadership of the regency council.

Coming of age and coronation

Christian continued his studies atSorø Academy

Sorø Academy (Danish, ''Sorø Akademi'') is a boarding school and gymnasium located in the small town of Sorø, Denmark. It traces its history back to the 12th century when Bishop Absalon founded a monastery at the site, which was confiscated by ...

where he had a reputation as a headstrong and talented student."Gads Historieleksikon", 3rd edition, 2006. Paul Ulff-Møller, "''Christian 4.''", pp.99–100.

In 1595, the Council of the Realm

The Council of the Realm ( es, Consejo del Reino) was a corporate organ of Francoist Spain, created by the Law of Succession to the Headship of the State of 1947. Within the institutional complex created to hierarchize the regime of Francisco Fran ...

decided that Christian would soon be old enough to assume personal control of the reins of government. On 17 August 1596, at the age of 19, Christian signed his haandfæstning

A Haandfæstning ( Modern da, Håndfæstning & Modern no, Håndfestning, lit. "Handbinding", plural ''Haandfæstninger'') was a document issued by the kings of Denmark from 13th to the 17th century, preceding and during the realm's personal un ...

(lit. "Handbinding" viz. curtailment of the monarch's power, a Danish parallel to the Magna Carta

(Medieval Latin for "Great Charter of Freedoms"), commonly called (also ''Magna Charta''; "Great Charter"), is a royal charter of rights agreed to by King John of England at Runnymede, near Windsor, on 15 June 1215. First drafted by the ...

), which was an identical copy of his father's from 1559.

Twelve days later, on 29 August 1596, Christian IV was crowned at the Church of Our Lady in Copenhagen

Copenhagen ( or .; da, København ) is the capital and most populous city of Denmark, with a proper population of around 815.000 in the last quarter of 2022; and some 1.370,000 in the urban area; and the wider Copenhagen metropolitan ar ...

by the Bishop of Zealand The Diocese of Zealand (Danish: ''Sjællands Stift'') was a protestant diocese in Denmark that existed from 1537 to 1922. The diocese had been formed in 1537 following the Reformation in Denmark–Norway and Holstein, Reformation of Denmark, and wa ...

, Peder Jensen Vinstrup (1549–1614). He was crowned with a new Danish Crown Regalia

Danish Crown Regalia are the symbols of the Danish monarchy. They consist of three crowns, a Sceptre (symbolizing supreme authority), Globus cruciger (an orb symbolizing the earthly realm surmounted by a cross), the Sword of state and an Ampull ...

which had been made for him by Dirich Fyring (1580–1603), assisted by the Nuremberg

Nuremberg ( ; german: link=no, Nürnberg ; in the local East Franconian dialect: ''Nämberch'' ) is the second-largest city of the German state of Bavaria after its capital Munich, and its 518,370 (2019) inhabitants make it the 14th-largest ...

goldsmith, Corvinius Saur.

Marriage

On 30 November 1597, he marriedAnne Catherine of Brandenburg

Anne Catherine of Brandenburg (26 June 1575 – 8 April 1612) was Queen of Denmark and Norway from 1597 to 1612 as the first spouse of King Christian IV of Denmark.

Life

Anne Catherine was born in Halle (Saale) and raised in Wolmirstedt. Her par ...

, a daughter of Joachim Friedrich

Joachim Frederick (27 January 1546 – 18 July 1608), of the House of Hohenzollern, was Prince-elector of the Margraviate of Brandenburg from 1598 until his death.

Biography

Joachim Frederick was born in Cölln to John George, Elector of Brande ...

, Margrave of Brandenburg

This article lists the Margraves and Electors of Margraviate of Brandenburg, Brandenburg during the period of time that Brandenburg was a constituent state of the Holy Roman Empire.

The Mark, or ''March'', of Brandenburg was one of the primary c ...

and Duke of Prussia

The monarchs of Prussia were members of the House of Hohenzollern who were the hereditary rulers of the former German state of Prussia from its founding in 1525 as the Duchy of Prussia. The Duchy had evolved out of the Teutonic Order, a Roman C ...

.

Reign

Military and economic reforms

Christian took an interest in many and varied matters, including a series of domestic reforms and improving Danish national armaments. New fortresses were constructed under the direction of

Christian took an interest in many and varied matters, including a series of domestic reforms and improving Danish national armaments. New fortresses were constructed under the direction of Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

engineers. The Royal Dano-Norwegian Navy

The history of the Danish navy began with the founding of a joint Dano-Norwegian navy on 10 August 1510, when King John appointed his vassal Henrik Krummedige to become "chief captain and head of all our captains, men and servants whom we now h ...

, which in 1596 had consisted of but twenty-two vessels, in 1610 rose to sixty, some of them built after Christian's own designs. The formation of a national army proved more difficult. Christian had to depend mainly upon hired mercenary

A mercenary, sometimes also known as a soldier of fortune or hired gun, is a private individual, particularly a soldier, that joins a military conflict for personal profit, is otherwise an outsider to the conflict, and is not a member of any o ...

troops as was common practice in the times—well before the establishment of standing armies—augmented by native peasant levies recruited for the most part from the peasantry on the crown domains.

Up until the early 1620s, Denmark-Norway's economy profited from general boom conditions in Europe. This inspired Christian to initiate a policy of expanding Denmark-Norway's overseas trade as part of the mercantilist

Mercantilism is an economic policy that is designed to maximize the exports and minimize the imports for an economy. It promotes imperialism, colonialism, tariffs and subsidies on traded goods to achieve that goal. The policy aims to reduce a ...

wave fashionable in Europe. He founded a number of merchant cities, and supported the building of factories. He also built a large number of buildings in Dutch Renaissance

The Renaissance in the Low Countries was a cultural period in the Northern Renaissance that took place in around the 16th century in the Low Countries (corresponding to modern-day Belgium, the Netherlands and French Flanders).

Culture in the Low C ...

style.

Visits to England

His sisterAnne

Anne, alternatively spelled Ann, is a form of the Latin female given name Anna. This in turn is a representation of the Hebrew Hannah, which means 'favour' or 'grace'. Related names include Annie.

Anne is sometimes used as a male name in the ...

had married King James VI of Scotland

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until hi ...

, who succeeded to the English throne

The Throne of England is the throne of the Monarch of England. "Throne of England" also refers metonymically to the office of monarch, and monarchy itself.Gordon, Delahay. (1760) ''A General History of the Lives, Trials, and Executions of All the ...

in 1603. To foster friendly relations between the two kingdoms, Christian paid a state visit to England in 1606. The visit was generally judged to be a success, although the heavy drinking indulged in by English and Danes alike caused some unfavourable comments: both Christian and James had an ability to consume great amounts of alcohol, while remaining lucid, which most of their courtiers did not share. Sir John Harington described an entertainment at Theobalds

Theobalds House (also known as Theobalds Palace) in the parish of Cheshunt in the English county of Hertfordshire, was a significant stately home and (later) royal palace of the 16th and early 17th centuries. Set in extensive parkland, it was a r ...

, a masque of Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, as a drunken fiasco, where most of the players simply fell over from the effects of too much wine. The royal party went to Upnor Castle

Upnor Castle is an Elizabethan artillery fort located on the west bank of the River Medway in Kent. It is in the village of Upnor, opposite and a short distance downriver from the Chatham Dockyard, at one time a key naval facility. The fort was ...

and had dinner aboard the '' Elizabeth Jonas''. At Gravesend, when the royal party was on his ship the ''Admiral'', Christian IV provided a firework display built on a small ship or lighter, which brought tears to eyes of King James, although the effect was somewhat spoiled because the show was held in daylight. After an exchange of gifts Christian sailed home, escorted by Robert Mansell

Sir Robert Mansell (1573–1656) was an admiral of the English Royal Navy and a Member of Parliament (MP), mostly for Welsh constituencies. His name was sometimes given as Sir Robert Mansfield and Sir Robert Maunsell.

Early life

Mansel was a W ...

with the ''Vanguard

The vanguard (also called the advance guard) is the leading part of an advancing military formation. It has a number of functions, including seeking out the enemy and securing ground in advance of the main force.

History

The vanguard derives fr ...

'' and the ''Moon''.

Christian IV visited England again in August 1614, coming incognito to surprise his sister at Denmark House

Somerset House is a large Neoclassical complex situated on the south side of the Strand in central London, overlooking the River Thames, just east of Waterloo Bridge. The Georgian era quadrangle was built on the site of a Tudor palace (" ...

, accompanied only by Andrew Sinclair

Andrew Annandale Sinclair FRSL FRSA (21 January 1935 – 30 May 2019) was a British novelist, historian, biographer, critic, filmmaker, and a publisher of classic and modern film scripts. He has been described as a "writer of extraordinary flu ...

and a page. He had sailed with only three ships and captured some pirates during the voyage. More ships with his Danish courtiers arrived on 5 August. The diplomatic purpose of the visit was kept secret. The Venetian ambassador Antonio Foscarini

Antonio Foscarini (c. 1570 in Venice – April 22, 1622) belonged to the Venetian nobility and was Venetian ambassador to Paris and later to London. He was the third son of Nicolò di Alvise of the family branch of San Polo and Maria Barbarigo di ...

heard that Anne of Denmark had written to him about a dispute with King James. Foscarini described Christian as, "above the average in height, dressed in the French fashion. His nature is warlike".

Exploration and colonies

Despite Christian's many efforts, the new economic projects did not return a profit. He looked abroad for new income. Christian IV's Expeditions to Greenland involved a series of voyages in the years 1605–1607 to Greenland and to Arctic waterways in order to locate the lostEastern Norse Settlement

The Eastern Settlement ( non, Eystribygð ) was the first and by far the larger of the two main areas of Norse Greenland, settled by Norsemen from Iceland. At its peak, it contained approximately 4,000 inhabitants. The last written record from t ...

and to assert Danish sovereignty over Greenland. The expeditions were unsuccessful, partly due to leaders lacking experience with the difficult Arctic ice and weather conditions. The pilot on all three trips was English explorer James Hall. An expedition to North America was commissioned in 1619. The expedition was captained by Dano-Norwegian

Dano-Norwegian (Danish and no, dansk-norsk) was a koiné/mixed language that evolved among the urban elite in Norwegian cities during the later years of the union between the Kingdoms of Denmark and Norway (1536/1537–1814). It is from this ...

navigator and explorer, Jens Munk

Jens Munk (3 June 1579 – June 1628) was a Danish-Norwegian navigator and explorer. He entered into the service of King Christian IV of Denmark-Norway and is most noted for his attempts to find the Northwest Passage.

Early life

Jens Munk ...

. The ships, searching for the Northwest Passage

The Northwest Passage (NWP) is the sea route between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through the Arctic Ocean, along the northern coast of North America via waterways through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. The eastern route along the Arct ...

, arrived in Hudson Bay

Hudson Bay ( crj, text=ᐐᓂᐯᒄ, translit=Wînipekw; crl, text=ᐐᓂᐹᒄ, translit=Wînipâkw; iu, text=ᑲᖏᖅᓱᐊᓗᒃ ᐃᓗᐊ, translit=Kangiqsualuk ilua or iu, text=ᑕᓯᐅᔭᕐᔪᐊᖅ, translit=Tasiujarjuaq; french: b ...

landing at the mouth of Churchill River, settling at what is now Churchill, Manitoba

Churchill is a town in northern Manitoba, Canada, on the west shore of Hudson Bay, roughly from the Manitoba–Nunavut border. It is most famous for the many polar bears that move toward the shore from inland in the autumn, leading to the nickname ...

. However, it was a disastrous voyage, with cold, famine, and scurvy

Scurvy is a disease resulting from a lack of vitamin C (ascorbic acid). Early symptoms of deficiency include weakness, feeling tired and sore arms and legs. Without treatment, decreased red blood cells, gum disease, changes to hair, and bleeding ...

killing most of the crew.

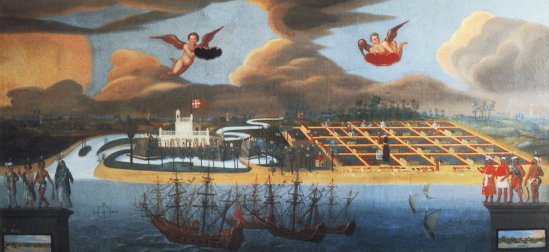

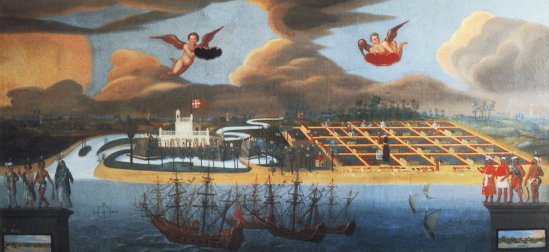

In 1618, Christian appointed Admiral

In 1618, Christian appointed Admiral Ove Gjedde

Ove Gjedde (27 December 1594 – 19 December 1660) was a Danish nobleman and Admiral of the Realm (''Rigsadmiral''). He established the Danish colony at Tharangambadi (Danish: ''Trankebar'') and constructed Fort Dansborg as the base for Da ...

to lead an expedition and establish a Danish colony in Ceylon

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

. The expedition set sail in 1618, taking two years to reach Ceylon and losing more than half their crew on the way. Upon arriving in May 1620, the establishment of a colony in Ceylon failed, but instead the ''Nayak'' of Tanjore (now Thanjavur in Tamil Nadu) turned out to be interested in trading opportunities and a treaty was negotiated granting the Danes the village of Tranquebar

Tharangambadi (), formerly Tranquebar ( da, Trankebar, ), is a town in the Mayiladuthurai district of the Indian state of Tamil Nadu on the Coromandel Coast. It lies north of Karaikal, near the mouth of a distributary named Uppanar of the Kave ...

(or Tarangamabadi) on India's south coast and the right to construct a "stone house" (Fort Dansborg

Fort Dansborg ( da, Dansborg), locally called Danish Fort ( ta, டேனியக் கோட்டை, translit=Ṭēṉiyak kōṭṭai), is a Denmark, Danish fort located in the shores of Bay of Bengal in Tranquebar (Tharangambadi) in the S ...

) and levy taxes. The treaty was signed on 20 November 1620, establishing Denmark's first colony in India. Christian also assigned the privilege establishing the Danish East India Company

The Danish East India Company ( da, Ostindisk Kompagni) refers to two separate Danish-Norwegian chartered companies. The first company operated between 1616 and 1650. The second company existed between 1670 and 1729, however, in 1730 it was re-fo ...

.

Kalmar War

In 1611, he first put his newly organised army to use. Despite the reluctance of ''Rigsrådet'', Christian initiated a war with Sweden for the supremacy of theBaltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from ...

. It was later known as the Kalmar War

The Kalmar War (1611–1613) was a war between Denmark–Norway and Sweden. Though Denmark-Norway soon gained the upper hand, it was unable to defeat Sweden entirely. The Kalmar War was the last time Denmark-Norway successfully defended its ''dom ...

because its chief operation was the Danish capture of Kalmar

Kalmar (, , ) is a city in the southeast of Sweden, situated by the Baltic Sea. It had 36,392 inhabitants in 2010 and is the seat of Kalmar Municipality. It is also the capital of Kalmar County, which comprises 12 municipalities with a total of ...

, the southernmost fortress of Sweden. Christian compelled King Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden

Gustavus Adolphus (9 December Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">N.S_19_December.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="/nowiki>Old Style and New Style dates">N.S 19 December">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="/now ...

to give way on all essential points at the resulting Treaty of Knäred

The Treaty of Knäred ( da, Freden i Knærød, sv, Freden i Knäred) was signed on 21 January 1613 and ended the Kalmar War (1611–1613) between Denmark-Norway and Sweden. The peace negotiations came about under an English initiative. The peace ...

of 20 January 1613. However, despite Denmark's greater strength, the gains of the war were not decisive.

He now turned his attention to the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (80 ...

in Germany. Here, his objectives were twofold: first, to obtain control of the great German rivers— the Elbe

The Elbe (; cs, Labe ; nds, Ilv or ''Elv''; Upper and dsb, Łobjo) is one of the major rivers of Central Europe. It rises in the Giant Mountains of the northern Czech Republic before traversing much of Bohemia (western half of the Czech Repu ...

and the Weser

The Weser () is a river of Lower Saxony in north-west Germany. It begins at Hannoversch Münden through the confluence of the Werra and Fulda. It passes through the Hanseatic city of Bremen. Its mouth is further north against the ports of Bre ...

— as a means of securing his dominion of the northern seas; and secondly, to acquire the secularised German Archdiocese of Bremen

The Prince-Archbishopric of Bremen (german: Fürsterzbistum Bremen) — not to be confused with the modern Archdiocese of Hamburg, founded in 1994 — was an ecclesiastical principality (787–1566/1648) of the Holy Roman Empire and the Catholic ...

and Prince-Bishopric of Verden

The Prince-Bishopric of Verden (german: Fürstbistum Verden, ''Hochstift Verden'' or ''Stift Verden'') was an ecclesiastical principality of the Holy Roman Empire that was located in what is today the state of Lower Saxony in Germany. Verden had be ...

as appanage

An appanage, or apanage (; french: apanage ), is the grant of an estate, title, office or other thing of value to a younger child of a sovereign, who would otherwise have no inheritance under the system of primogeniture. It was common in much o ...

s for his younger sons. He skillfully took advantage of the alarm of the German Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

s after the Battle of White Mountain

), near Prague, Bohemian Confederation(present-day Czech Republic)

, coordinates =

, territory =

, result = Imperial-Spanish victory

, status =

, combatants_header =

, combatant1 = Catholic L ...

in 1620, to secure co-adjutorship of the See of Bremen for his son Frederick Frederick may refer to:

People

* Frederick (given name), the name

Nobility

Anhalt-Harzgerode

*Frederick, Prince of Anhalt-Harzgerode (1613–1670)

Austria

* Frederick I, Duke of Austria (Babenberg), Duke of Austria from 1195 to 1198

* Frederick ...

(September 1621). A similar arrangement was reached in November at Verden. Hamburg was also induced to acknowledge the Danish overlordship of Holstein

Holstein (; nds, label=Northern Low Saxon, Holsteen; da, Holsten; Latin and historical en, Holsatia, italic=yes) is the region between the rivers Elbe and Eider. It is the southern half of Schleswig-Holstein, the northernmost state of German ...

by the compact of Steinburg in July 1621.

Thirty Years' War

Christian IV had obtained for his kingdom a level of stability and wealth that was virtually unmatched elsewhere in Europe. Denmark was funded by tolls on the

Christian IV had obtained for his kingdom a level of stability and wealth that was virtually unmatched elsewhere in Europe. Denmark was funded by tolls on the Øresund

Øresund or Öresund (, ; da, Øresund ; sv, Öresund ), commonly known in English as the Sound, is a strait which forms the Danish–Swedish border, separating Zealand (Denmark) from Scania (Sweden). The strait has a length of ; its width v ...

and also by extensive war-reparations from Sweden. Denmark's intervention in the Thirty Years' War was aided by France and by Charles I of England, who agreed to help subsidise the war partly because Christian was the uncle of both the Stuart king and his sister Elizabeth of Bohemia

Elizabeth Stuart (19 August 159613 February 1662) was Electress of the Palatinate and briefly Queen of Bohemia as the wife of Frederick V of the Palatinate. Since her husband's reign in Bohemia lasted for just one winter, she is called the Win ...

through their mother, Anne of Denmark

Anne of Denmark (; 12 December 1574 – 2 March 1619) was the wife of King James VI and I; as such, she was Queen of Scotland

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the constitutional fo ...

. Some 13,700 Scottish soldiers were to be sent as allies to help Christian IV under the command of General Robert Maxwell, 1st Earl of Nithsdale

Robert Maxwell, 1st Earl of Nithsdale (after 1586 – May 1646), was a Scottish nobleman. He succeeded his brother as 10th Lord Maxwell in 1613, and was created Earl of Nithsdale in 1620. General of Scots in Danish-Norwegian service during the ...

. Moreover, some 6000 English troops under Sir Charles Morgan also eventually arrived to bolster the defence of Denmark though it took longer for these to arrive than Christian hoped, not least due to the ongoing British campaigns against France and Spain. Thus Christian, as war-leader of the Lower Saxon Circle, entered the war with an army of only 20,000 mercenaries, some of his allies from Britain and a national army 15,000 strong, leading them as Duke of Holstein rather than as King of Denmark.

Despite the growing power of Roman Catholics in North Germany, and the threat to the Danish holdings in the Schleswig-Holstein

Schleswig-Holstein (; da, Slesvig-Holsten; nds, Sleswig-Holsteen; frr, Slaswik-Holstiinj) is the northernmost of the 16 states of Germany, comprising most of the historical duchy of Holstein and the southern part of the former Duchy of Sch ...

duchies, Christian for a time stayed his hand. The urgent solicitations of other powers, and his fear that Gustavus Adolphus should supplant him as the champion of the Protestant cause, finally led him to enter the war on 9 May 1625. He also feared that Sweden could use a war to further expand their holdings in the Baltic Sea. Christian embarked on a military campaign which was later known in Denmark and Norway as "The Emperor War" ( da, Kejserkrigen, no, Keiserkrigen).

He had at his disposal from 19,000 to 25,000 men, and at first gained some successes but on 27 August 1626 he was routed by Johan Tzerclaes, Count of Tilly

Johann Tserclaes, Count of Tilly ( nl, Johan t'Serclaes Graaf van Tilly; german: Johann t'Serclaes Graf von Tilly; french: Jean t'Serclaes de Tilly ; February 1559 – 30 April 1632) was a field marshal who commanded the Catholic League (Ge ...

in the Battle of Lutter

The Battle of Lutter (German: ''Lutter am Barenberge'') took place on 27 August 1626 during the Thirty Years' War, south of Salzgitter, in Lower Saxony. A combined Danish-German force led by Christian IV of Denmark was defeated by Johan Tzerclae ...

. Christian had not thoroughly planned the advance against the combined forces of the Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans ( la, Imperator Romanorum, german: Kaiser der Römer) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period ( la, Imperat ...

and the Catholic League, as promises of military support from the Netherlands and England did not materialise."Gads Historieleksikon", 3rd edition, 2006. Paul Ulff-Møller, "''Kejserkrigen''", p.352. In the summer of 1627 both Tilly and Albrecht von Wallenstein

Albrecht Wenzel Eusebius von Wallenstein () (24 September 1583 – 25 February 1634), also von Waldstein ( cs, Albrecht Václav Eusebius z Valdštejna), was a Bohemian military leader and statesman who fought on the Catholic side during the Th ...

occupied the duchies and the whole peninsula of Jutland

Jutland ( da, Jylland ; german: Jütland ; ang, Ēota land ), known anciently as the Cimbric or Cimbrian Peninsula ( la, Cimbricus Chersonesus; da, den Kimbriske Halvø, links=no or ; german: Kimbrische Halbinsel, links=no), is a peninsula of ...

.

Christian now formed an alliance with Sweden on 1 January 1628, as he and Gustavus Adolphus shared the reluctance of German expansion in the Baltic region. Gustavus Adolphus pledged to assist Denmark with a fleet in case of need, and shortly afterwards a Swedo-Danish army and fleet compelled Wallenstein to raise the siege of Stralsund. Thus with the help of Sweden, the superior sea-power enabled Denmark to tide over her worst difficulties, and in May 1629 Christian was able to conclude peace with the emperor in the Treaty of Lübeck

Treaty or Peace of Lübeck ( da, Freden i Lübeck, german: Lübecker Frieden) ended the Danish intervention in the Thirty Years' War (Low Saxon or Emperor's War, Kejserkrigen). It was signed in Lübeck on 22 May 1629 by Albrecht von Wallenstein a ...

, without any diminution of territory. However, the treaty bound Christian not to interfere in the Thirty Years' War any further, removing any Danish obstacles when Gustavus Adolphus entered the war in 1630.

Containment of Sweden

Christian's foreign policy did not suffer from lack of confidence following the Danish defeat in The Thirty Years' War. To compensate for lacking export revenues, and also in order to stifle the Swedish advances in the Thirty Years' War, Christian enacted a number of increases in theSound Dues

The Sound Dues (or Sound Tolls; da, Øresundstolden) were a toll on the use of the Øresund, or "Sound" strait separating the modern day borders of Denmark and Sweden. The tolls constituted up to two thirds of Denmark's state income in the 16th a ...

throughout the 1630s. Christian gained both in popularity and influence at home, and he hoped to increase his external power still further with the assistance of his sons-in-law, Corfitz Ulfeldt

Count Corfits Ulfeldt (10 July 1606 – 20 February 1664) was a Denmark, Danish politician, statesman, and one of the most notorious traitors in Danish history.

Early life

Ulfeldt was the son of the chancellor Jacob Ulfeldt (1567–1630), ...

and Hannibal Sehested, who now came prominently forward.

Between 1629 and 1643 the European situation presented infinite possibilities to politicians with a taste for adventure. However, Christian was incapable of a consistent diplomatic policy. He would neither conciliate Sweden, henceforth his most dangerous enemy, nor guard himself against her by a definite system of counter-alliances. Christian contacted the Roman Catholic part of the Thirty Years' War, and offered to broker a deal with Sweden. However, his mediating was highly skewed in favour of the Holy Roman Emperor, and was a transparent attempt at minimising the Swedish influence in the Baltics."Gads Historieleksikon", 3rd edition, 2006. Paul Ulff-Møller, "''Torstensson-krigen''", pp.658–659. His Scandinavian policy was so irritating and vexatious that Swedish statesmen advocated for a war with Denmark, to keep Christian from interfering in the peace negotiations with the Holy Roman Emperor, and in May 1643, Christian faced another war against Sweden. The increased Sound Dues had alienated the Dutch, who turned to support Sweden.

Torstenson War

Sweden was able, thanks to their conquests in the Thirty Years' War, to attack Denmark from the south as well as the east; the Dutch alliance promised to secure them at sea. In May 1643 the Swedish

Sweden was able, thanks to their conquests in the Thirty Years' War, to attack Denmark from the south as well as the east; the Dutch alliance promised to secure them at sea. In May 1643 the Swedish Privy Council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mon ...

decided upon war; on 12 December the Swedish Field Marshal

Field marshal (or field-marshal, abbreviated as FM) is the most senior military rank, ordinarily senior to the general officer ranks. Usually, it is the highest rank in an army and as such few persons are appointed to it. It is considered as ...

Lennart Torstensson

Lennart Torstensson, Count of Ortala, Baron of Virestad (17 August 16037 April 1651), was a Swedish Field Marshal and military engineer.

Early career

He was born at Forstena manor in Västergötland. His parents were Märta Nilsdotter Posse a ...

, advancing from Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

, crossed the southern frontier of Denmark; and by the end of January 1644 the whole peninsula of Jutland

Jutland ( da, Jylland ; german: Jütland ; ang, Ēota land ), known anciently as the Cimbric or Cimbrian Peninsula ( la, Cimbricus Chersonesus; da, den Kimbriske Halvø, links=no or ; german: Kimbrische Halbinsel, links=no), is a peninsula of ...

was in Swedish hands. This unexpected attack, conducted from first to last with consummate ability and lightning-like rapidity, had a paralysing effect upon Denmark.

In his sixty-sixth year he once more displayed something of the energy of his triumphant youth. Night and day he laboured to levy armies and equip fleets. Fortunately for him, the Swedish government delayed hostilities in Scania

Scania, also known by its native name of Skåne (, ), is the southernmost of the historical provinces of Sweden, provinces (''landskap'') of Sweden. Located in the south tip of the geographical region of Götaland, the province is roughly conte ...

until February 1644, and the Danes were able to make adequate defensive preparations and save the important fortress of Malmö

Malmö (, ; da, Malmø ) is the largest city in the Swedish county (län) of Scania (Skåne). It is the third-largest city in Sweden, after Stockholm and Gothenburg, and the sixth-largest city in the Nordic region, with a municipal populat ...

. The Danish fleet prevented Torstensson crossing from Jutland to Funen

Funen ( da, Fyn, ), with an area of , is the third-largest island of Denmark, after Zealand and Vendsyssel-Thy. It is the 165th-largest island in the world. It is located in the central part of the country and has a population of 469,947 as of ...

, and defeated the Dutch auxiliary fleet which came to Torstensson's assistance at the action of 16 May 1644. Another attempt to transport Torstensson and his army to the Danish islands by a large Swedish fleet was frustrated by Christian IV in person on 1 July 1644. On that day the two fleets encountered at the Battle of Colberger Heide

The Battle of Colberger Heide (also Kolberger Heide or Colberg Heath) took place on 1 July 1644 during the Torstenson War, off the coast of Schleswig-Holstein. The battle was indecisive, but a minor success for the Dano-Norwegian fleet command ...

. As Christian stood on the quarter-deck of the ''Trinity'' a cannon close by was exploded by a Swedish cannonball, and splinters of wood and metal wounded the king in thirteen places, blinding one eye and flinging him to the deck. But he was instantly on his feet again, cried with a loud voice that it was well with him, and set every one an example of duty by remaining on deck till the fight was over. Darkness at last separated the contending fleets; and the battle was drawn.

The Danish fleet subsequently blockaded the Swedish ships in the Bay of Kiel

The Bay of Kiel or Kiel Bay (, ; ) is a bay in the southwestern Baltic Sea, off the shores of Schleswig-Holstein in Germany and the islands of Denmark. It is connected with the Bay of Mecklenburg in the east, the Little Belt in the northwest, ...

. But the Swedish fleet escaped, and the annihilation of the Danish fleet by the combined navies of Sweden and the Netherlands, after an obstinate fight between Fehmarn

Fehmarn (, da, Femern; from Old Wagrian Slavic "''Fe More''", meaning "''In the Sea''") is an island in the Baltic Sea, off the eastern coast of Germany's northernmost state of Schleswig-Holstein. It is Germany's third-largest island, after Rüg ...

and Lolland

Lolland (; formerly spelled ''Laaland'', literally "low land") is the fourth largest island of Denmark, with an area of . Located in the Baltic Sea, it is part of Region Sjælland (Region Zealand). As of 1 January 2022, it has 57,618 inhabitant ...

at the end of September, exhausted the military resources of Denmark and compelled Christian to accept the mediation of France and the Netherlands; and peace was finally signed with the Treaty of Brömsebro on 8 February 1645. Here Denmark had to cede Gotland

Gotland (, ; ''Gutland'' in Gutnish), also historically spelled Gottland or Gothland (), is Sweden's largest island. It is also a province, county, municipality, and diocese. The province includes the islands of Fårö and Gotska Sandön to the ...

, Ösel

Saaremaa is the largest island in Estonia, measuring . The main island of Saare County, it is located in the Baltic Sea, south of Hiiumaa island and west of Muhu island, and belongs to the West Estonian Archipelago. The capital of the island i ...

and (for thirty years) Halland

Halland () is one of the traditional provinces of Sweden (''landskap''), on the western coast of Götaland, southern Sweden. It borders Västergötland, Småland, Scania and the sea of Kattegat. Until 1645 and the Second Treaty of Brömsebro ...

, while Norway lost the two provinces Jämtland

Jämtland (; no, Jemtland or , ; Jamtish: ''Jamtlann''; la, Iemptia) is a historical province () in the centre of Sweden in northern Europe. It borders Härjedalen and Medelpad to the south, Ångermanland to the east, Lapland to the north a ...

and Härjedalen

Härjedalen (; no, Herjådalen or ) is a historical Provinces of Sweden, province (''landskap'') in the centre of Sweden. It borders the Norway, Norwegian county of Trøndelag as well as the provinces of Dalarna, Hälsingland, Medelpad, and Jä ...

, giving Sweden the supremacy of the Baltic Sea.

Norwegian issue

Christian IV spent more time in the kingdom of Norway than any other Oldenburg monarch and no Oldenburg king made such a lasting impression on the Norwegian people. He visited the country a number of times and founded four cities. He also established and took control over one silver mine (Kongsberg

Kongsberg () is a historical mining town and municipality in Buskerud, Viken county, Norway. The city is located on the river Numedalslågen at the entrance to the valley of Numedal. Kongsberg has been a centre of silver mining, arms production ...

), one copper mine (Røros

Røros ( sma, Plaassja, ) is a municipality in Trøndelag county, Norway. The administrative centre of the municipality is the town of Røros. Some of the villages in Røros include Brekken, Glåmos, Feragen, Galåa, and Hitterdalen.

The minin ...

), and tried to make an iron plant with limited success in Eiker. He also restored and restructured the castle Akershus

Akershus () is a traditional region and current electoral district in Norway, with Oslo as its main city and traditional capital. It is named after the Akershus Fortress in Oslo. From the middle ages to 1919, Akershus was a fief and main county ...

, where he invited the people of Norway to the official and age-old installment of the king in 1590, and again in 1610.

When the king was busy overseeing the reparations and re-building of the fortress at Oslo, he lived in the country all summer, and at the same time tried to establish a centre for producing iron at Eiker

Eiker is a traditional district in the county of Buskerud, Norway.

History

Eiker consists of the municipalities of Nedre Eiker and Øvre Eiker. The area is located in the southern part of Buskerud county.

Eiker is an agricultural area with a lo ...

, Buskerud

Buskerud () is a former county and a current electoral district in Norway, bordering Akershus, Oslo, Oppland, Sogn og Fjordane, Hordaland, Telemark and Vestfold. The region extends from the Oslofjord and Drammensfjorden in the southeast to Hardan ...

. History tells he actually ruled the entire kingdom from this area in the summer of 1603.

In 1623, Christian again visited Norway for an entire summer, this time to oversee the foundation of Kongsberg

Kongsberg () is a historical mining town and municipality in Buskerud, Viken county, Norway. The city is located on the river Numedalslågen at the entrance to the valley of Numedal. Kongsberg has been a centre of silver mining, arms production ...

. He was also present in the area in 1624, when Oslo burned in August of that year. The king was able to reach the area in a few weeks, being in Eiker. Over the years, fire had destroyed major parts of the city many times, as many of the city's buildings were built entirely of wood. After the fire in 1624 which lasted for three days, Christian IV decided that the old city should not be rebuilt again. He decided that the new town be rebuilt in the area below Akershus Fortress

Akershus Fortress ( no, Akershus Festning, ) or Akershus Castle ( no, Akershus slott ) is a medieval castle in the Norwegian capital Oslo that was built to protect and provide a royal residence for the city. Since the Middle Ages the fortress h ...

, a castle which later was converted into a palace and royal residence. His men built a network of roads in Akershagen and demanded that all citizens should move their shops and workplaces to the newly built city of Christiania.

Securing the Northern Lands under the Danish-Norwegian Crown

During the fourteenth century the Swedish kings tried to push the areas of their control towards the north, andcontemporary

Contemporary history, in English-language historiography, is a subset of modern history that describes the historical period from approximately 1945 to the present. Contemporary history is either a subset of the late modern period, or it is o ...

maps depicted the now Norwegian coastal areas of Troms

Troms (; se, Romsa; fkv, Tromssa; fi, Tromssa) is a former county in northern Norway. On 1 January 2020 it was merged with the neighboring Finnmark county to create the new Troms og Finnmark county. This merger is expected to be reversed by t ...

and Finnmark

Finnmark (; se, Finnmárku ; fkv, Finmarku; fi, Ruija ; russian: Финнмарк) was a county in the northern part of Norway, and it is scheduled to become a county again in 2024.

On 1 January 2020, Finnmark was merged with the neighbouri ...

as a part of Sweden. The possibly boldest move of any Danish-Norwegian regent was to make a voyage to the Northern Lands to secure these lands under the Danish-Norwegian crown.

Last years and death

After the Torstenson War, ''Rigsrådet'' took on an increasing role, under the leadership of

After the Torstenson War, ''Rigsrådet'' took on an increasing role, under the leadership of Corfitz Ulfeldt

Count Corfits Ulfeldt (10 July 1606 – 20 February 1664) was a Denmark, Danish politician, statesman, and one of the most notorious traitors in Danish history.

Early life

Ulfeldt was the son of the chancellor Jacob Ulfeldt (1567–1630), ...

and Hannibal Sehested. The last years of Christian's life were embittered by sordid differences with his sons-in-law, especially with Corfitz Ulfeldt.

His personal obsession with witchcraft led to the public execution of some of his subjects during the Burning Times. He was responsible for several witch burnings, including 21 people in Iceland, and most notably the conviction and execution of Maren Spliid, who was victim of a witch hunt

A witch-hunt, or a witch purge, is a search for people who have been labeled witches or a search for evidence of witchcraft. The classical period of witch-hunts in Early Modern Europe and Colonial America took place in the Early Modern perio ...

at Ribe and was burned at the Gallows Hill near Ribe

Ribe () is a town in south-west Jutland, Denmark, with a population of 8,257 (2022). It is the seat of the Diocese of Ribe covering southwestern Jutland. Until 1 January 2007, Ribe was the seat of both a surrounding Ribe Municipality, municipali ...

on 9 November 1641.

On 21 February 1648, at his earnest request, he was carried in a litter from Frederiksborg to his beloved Copenhagen

Copenhagen ( or .; da, København ) is the capital and most populous city of Denmark, with a proper population of around 815.000 in the last quarter of 2022; and some 1.370,000 in the urban area; and the wider Copenhagen metropolitan ar ...

, where he died a week later. He was buried in Roskilde Cathedral

Roskilde Cathedral ( da, Roskilde Domkirke), in the city of Roskilde on the island of Zealand (Denmark), Zealand (''Sjælland'') in eastern Denmark, is a cathedral of the Lutheranism, Lutheran Church of Denmark.

The cathedral is the most importan ...

. The chapel of Christian IV had been completed 6 years before the King died.

Cultural king

Christian was reckoned a typical renaissance king, and excelled in hiring musicians and artists from all over Europe. Many English musicians were employed by him at several times, among themWilliam Brade

William Brade (1560 – 26 February 1630) was an English composer, violinist, and viol player of the late Renaissance and early Baroque eras, mainly active in northern Germany. He was the first Englishman to write a canzona, an Italian form ...

, John Bull

John Bull is a national personification of the United Kingdom in general and England in particular, especially in political cartoons and similar graphic works. He is usually depicted as a stout, middle-aged, country-dwelling, jolly and matter- ...

and John Dowland

John Dowland (c. 1563 – buried 20 February 1626) was an English Renaissance composer, lutenist, and singer. He is best known today for his melancholy songs such as "Come, heavy sleep", " Come again", "Flow my tears", " I saw my Lady weepe", ...

. Dowland accompanied the king on his tours, and as he was employed in 1603, rumour has it he was in Norway as well. Christian was an agile dancer, and his court was reckoned the second most "musical" court in Europe, only ranking behind that of Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is ...

. Christian maintained good contact with his sister Anne, who was married to King James. Christian asked Anne to request for him the services of Thomas Cutting, a lutenist employed by Arbella Stewart. His other sister, Elizabeth

Elizabeth or Elisabeth may refer to:

People

* Elizabeth (given name), a female given name (including people with that name)

* Elizabeth (biblical figure), mother of John the Baptist

Ships

* HMS ''Elizabeth'', several ships

* ''Elisabeth'' (sch ...

, was married to the Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they are rank ...

, and artists and musicians travelled freely between the courts.

City foundations

Christian IV is renowned for his many city (town) foundations, and is most likely the Nordichead of state

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international persona." in its unity and l ...

that can be accredited for the highest number of new cities in his realm

A realm is a community or territory over which a sovereign rules. The term is commonly used to describe a monarchical or dynastic state. A realm may also be a subdivision within an empire, if it has its own monarch, e.g. the German Empire.

Etym ...

. These towns/cities are:

* Christianopel, now Kristianopel in Sweden. Founded in 1599 in the then Danish territory of Blekinge

Blekinge (, old da, Bleking) is one of the traditional Swedish provinces (), situated in the southern coast of the geographic region of Götaland, in southern Sweden. It borders Småland, Scania and the Baltic Sea. It is the country's second ...

as a garrison town near the then Danish-Swedish border.

* Christianstad, now Kristianstad in Sweden. Founded in 1614 in the then Danish territory of Skåne

Scania, also known by its native name of Skåne (, ), is the southernmost of the historical provinces (''landskap'') of Sweden. Located in the south tip of the geographical region of Götaland, the province is roughly conterminous with Skåne C ...

.

* Glückstadt

Glückstadt (; da, Lykstad) is a town in the Steinburg district of Schleswig-Holstein, Germany. It is located on the right bank of the Lower Elbe at the confluence of the small Rhin river, about northwest of Altona. Glückstadt is part of the ...

, now in Germany, founded in 1617 as a rival to Hamburg

(male), (female) en, Hamburger(s),

Hamburgian(s)

, timezone1 = Central (CET)

, utc_offset1 = +1

, timezone1_DST = Central (CEST)

, utc_offset1_DST = +2

, postal ...

in the then Danish territory of Holstein

Holstein (; nds, label=Northern Low Saxon, Holsteen; da, Holsten; Latin and historical en, Holsatia, italic=yes) is the region between the rivers Elbe and Eider. It is the southern half of Schleswig-Holstein, the northernmost state of German ...

.

* Christianshavn

Christianshavn (literally, "ingChristian's Harbour") is a neighbourhood in Copenhagen, Denmark. Part of the Indre By District, it is located on several artificial islands between the islands of Zealand and Amager and separated from the rest of th ...

, now part of Copenhagen, Denmark, founded as a fortification/garrison town in 1619.

* ''Konningsberg'' (King's Mountain), now Kongsberg in Norway, founded as an industrial town in 1624 after the discovery of silver ore

Ore is natural rock or sediment that contains one or more valuable minerals, typically containing metals, that can be mined, treated and sold at a profit.Encyclopædia Britannica. "Ore". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 7 Apr ...

s.

* Christiania, now Oslo in Norway. After a devastating fire in 1624 the king ordered the old city of Oslo to be moved closer to the fortification of Akershus slot and also renamed it Christiania. The city name was altered to Kristiania in 1877 and then back to Oslo in 1924. The original town of Christian is now known as ''Kvadraturen'' = ''The Quarters''.

* Christian(s)sand, now Kristiansand in Norway, founded in 1641 to promote trade at the in Southern Norway.

* Røros

Røros ( sma, Plaassja, ) is a municipality in Trøndelag county, Norway. The administrative centre of the municipality is the town of Røros. Some of the villages in Røros include Brekken, Glåmos, Feragen, Galåa, and Hitterdalen.

The minin ...

, now in Norway, founded as an industrial town after the discovery of copper ores.

A short-lived town was:

* Christianspris

Christianspris or ''Frederiksort'' was a Danish fortification somewhat north of the then Danish city of Kiel. In 1632 the Danish king Christian IV initiated the works of making a fortification on a land tongue on the West shore of the Kielerfior ...

, now in Schleswig

The Duchy of Schleswig ( da, Hertugdømmet Slesvig; german: Herzogtum Schleswig; nds, Hartogdom Sleswig; frr, Härtochduum Slaswik) was a duchy in Southern Jutland () covering the area between about 60 km (35 miles) north and 70 km ...

, Germany, founded as a garrison town near Kiel

Kiel () is the capital and most populous city in the northern Germany, German state of Schleswig-Holstein, with a population of 246,243 (2021).

Kiel lies approximately north of Hamburg. Due to its geographic location in the southeast of the J ...

in the then Danish territory of Holstein.

Furthermore, Christian is known for erecting many important buildings in his realm, including the observatory Rundetårn, the stock exchange Børsen, the Copenhagen fortress Kastellet, Copenhagen, Kastellet, Rosenborg Castle, workers' district Nyboder'','' the Copenhagen naval Holmen Church (Holmens Kirke), Proviantgården, a brewery, the Tøjhus Museum arsenal, and two Trinity Churches in Copenhagen and modern Kristianstad, now known as respectively Trinitatis Church and Trinity Church, Kristianstad, Holy Trinity Church. Christian converted Frederiksborg Castle

Frederiksborg Castle ( da, Frederiksborg Slot) is a palatial complex in Hillerød, Denmark. It was built as a royal residence for King Christian IV of Denmark-Norway in the early 17th century, replacing an older castle acquired by Frederick II ...

to a Renaissance palace and completely rebuilt Kronborg Castle to a fortress. He also founded the Danish East India Company

The Danish East India Company ( da, Ostindisk Kompagni) refers to two separate Danish-Norwegian chartered companies. The first company operated between 1616 and 1650. The second company existed between 1670 and 1729, however, in 1730 it was re-fo ...

(''Asiatisk Kompagni'') inspired by the similar Dutch East India Company, Dutch company.

Legacy

When Christian was crowned king, Denmark-Norway held a supremacy over the Baltic Sea, which was lost to Sweden during the years of his reign. Nevertheless, Christian was one of the few kings from theHouse of Oldenburg

The House of Oldenburg is a Germans, German dynasty with links to Denmark since the 15th century. It has branches that rule or have ruled in Denmark, Iceland, Greece, Norway, Russia, Sweden, the United Kingdom, Duchy of Schleswig, Schleswig, Duchy ...

that achieved a lasting legacy of popularity with both the Danish and Norwegian people. As such, he featured in the Danish national play ''Elverhøj''. Furthermore, his great building activities also furthered his popularity.

Christian IV spoke Danish, German, Latin, French and Italian. Naturally cheerful and hospitable, he delighted in lively society; but he was also passionate, irritable and sensual. He had courage, a vivid sense of duty, an indefatigable love of work, and all the inquisitive zeal and inventive energy of a born reformer. His own pleasure, whether it took the form of love or ambition, was always his first consideration. His capacity for drink was proverbial: when he visited England in 1606, even the notoriously hard-drinking English Court were astonished by his alcohol consumption. In the heyday of his youth his high spirits and passion for adventure enabled him to surmount every obstacle with elan. But in the decline of life he reaped the bitter fruits of his lack of self-control, and sank into the grave a weary and brokenhearted old man.

The Christian IV Glacier in Greenland is named after him.

In fiction

*Christian IV is depicted as a brilliant but hard-drinking monarch in the Eric Flint and David Weber alternate-history novels ''1634: The Baltic War'' and ''1637: No Peace Beyond the Line''. *Christian IV is featured several times in the book series ''The Legend of the Ice People''. *Christian IV also features prominently in the novel ''Music and Silence'' by Rose Tremain, which is primarily set in and around the Danish court in the years 1629 and 1630. *Christian IV is depicted as a foul-natured person, but a good king who did a lot to make his realm flourish, by the Danish alternative music band Mew (band), Mew in their song, King Christian (Song), "King Christian". *Christian IV (Danish title: Christian IV - Den sidste rejse (2018) is a biographical movie, focusing on His Majesty King Christian IV's stormy relationship to Kirsten Munk, and the crucial last hours on his journey fromFrederiksborg Castle

Frederiksborg Castle ( da, Frederiksborg Slot) is a palatial complex in Hillerød, Denmark. It was built as a royal residence for King Christian IV of Denmark-Norway in the early 17th century, replacing an older castle acquired by Frederick II ...

to Rosenborg Castle on his deathbed. The turning point is Christian IV's and Kirsten Munk's turbulent marriage with accusations of infidelity and attempted murder.

Issue and private life

His first queen was Anne Catherine of Brandenburg, Anne Catherine. They were married from 1597 to 1612. She died after bearing Christian seven children. In 1615, three years after her death, the king privately married Kirsten Munk, by whom he had twelve children.

In 1632, an English envoy to king Christian IV, then aged 55, primly remarked "Such is the life of that king: to drink all day and to lie with a whore every night".

In the course of 1628, he discovered that his wife, Kirsten Munk, was having a relationship with one of his German officers. Christian had Munk placed under house arrest. She endeavoured to cover up her own disgrace by conniving at an intrigue between Vibeke Kruse, one of her discharged maids, and the king. In January 1630, the rupture became final and Kirsten retired to her estates in

His first queen was Anne Catherine of Brandenburg, Anne Catherine. They were married from 1597 to 1612. She died after bearing Christian seven children. In 1615, three years after her death, the king privately married Kirsten Munk, by whom he had twelve children.

In 1632, an English envoy to king Christian IV, then aged 55, primly remarked "Such is the life of that king: to drink all day and to lie with a whore every night".

In the course of 1628, he discovered that his wife, Kirsten Munk, was having a relationship with one of his German officers. Christian had Munk placed under house arrest. She endeavoured to cover up her own disgrace by conniving at an intrigue between Vibeke Kruse, one of her discharged maids, and the king. In January 1630, the rupture became final and Kirsten retired to her estates in Jutland

Jutland ( da, Jylland ; german: Jütland ; ang, Ēota land ), known anciently as the Cimbric or Cimbrian Peninsula ( la, Cimbricus Chersonesus; da, den Kimbriske Halvø, links=no or ; german: Kimbrische Halbinsel, links=no), is a peninsula of ...

. Meanwhile, Christian openly acknowledged Vibeke as his mistress, and she bore him several more children.

With his first wife, Anne Catherine of Brandenburg

Anne Catherine of Brandenburg (26 June 1575 – 8 April 1612) was Queen of Denmark and Norway from 1597 to 1612 as the first spouse of King Christian IV of Denmark.

Life

Anne Catherine was born in Halle (Saale) and raised in Wolmirstedt. Her par ...

he fathered the following children:

*Stillborn son (1598).

*Frederik (15 August 1599 – 9 September 1599).

*Christian, Prince Elect of Denmark, Christian (10 April 1603 – 2 June 1647).

*Sophie (4 January 1605 – 7 September 1605).

*Elisabeth (16 March 1606 – 24 October 1608).

*Frederick III of Denmark, Frederick III (18 March 1609 – 9 February 1670).

*Ulrik of Denmark (1611–1633), Ulrik (2 February 1611 – 12 August 1633); murdered, Administrator of the Bishopric of Schwerin, Prince-Bishopric of Schwerin as Ulrich III (1624–1633).

With his second wife, Kirsten Munk, he had 12 children, though the youngest, Dorothea Elisabeth, was rumoured to be the daughter of Kirsten's lover, Otto Ludwig:

*Stillborn child (b. & d. 1615).

*Unnamed infant (b. & d. 1617).

*Countess Anna Cathrine of Schleswig-Holstein (10 August 1618 – 20 August 1633); married Frands Rantzau.

*Sophie Elisabeth Pentz, Countess Sophie Elisabeth of Schleswig-Holstein (20 September 1619 – 29 April 1657); married Christian on Pentz.

*Leonora Christina Ulfeldt, Countess Leonora Christina of Schleswig-Holstein (8 July 1621 – 16 March 1698); married

With his second wife, Kirsten Munk, he had 12 children, though the youngest, Dorothea Elisabeth, was rumoured to be the daughter of Kirsten's lover, Otto Ludwig:

*Stillborn child (b. & d. 1615).

*Unnamed infant (b. & d. 1617).

*Countess Anna Cathrine of Schleswig-Holstein (10 August 1618 – 20 August 1633); married Frands Rantzau.

*Sophie Elisabeth Pentz, Countess Sophie Elisabeth of Schleswig-Holstein (20 September 1619 – 29 April 1657); married Christian on Pentz.

*Leonora Christina Ulfeldt, Countess Leonora Christina of Schleswig-Holstein (8 July 1621 – 16 March 1698); married Corfitz Ulfeldt

Count Corfits Ulfeldt (10 July 1606 – 20 February 1664) was a Denmark, Danish politician, statesman, and one of the most notorious traitors in Danish history.

Early life

Ulfeldt was the son of the chancellor Jacob Ulfeldt (1567–1630), ...

.

*Count Valdemar Christian of Schleswig-Holstein (26 June 1622 – 26 February 1656).

*Elisabeth Augusta Lindenov, Countess Elisabeth Auguste of Schleswig-Holstein (28 December 1623 – 9 August 1677); married Hans Lindenov.

*Count Friedrich Christian of Schleswig-Holstein (26 April 1625 – 17 July 1627).

*Christiane Sehested, Countess Christiane of Schleswig-Holstein (15 July 1626 – 6 May 1670); married Hannibal Sehested.

*Hedevig Ulfeldt, Countess Hedwig of Schleswig-Holstein (15 July 1626 – 5 October 1678); married Ebbe Ulfeldt.

*Countess Maria Katharina of Schleswig-Holstein (29 May 1628 – 1 September 1628).

*Dorothea Elisabeth Christiansdatter, Countess Dorothea Elisabeth of Schleswig-Holstein (1 September 1629 – 18 March 1687).

With Kirsten Madsdatter:

*Christian Ulrik Gyldenløve (1611–1640).

With Karen Andersdatter:

*Dorothea Elisabeth Gyldenløve (1613–1615).

*Hans Ulrik Gyldenløve (1615–1645).

With Vibeke Kruse:

*Ulrik Christian Gyldenløve (1630-1658), Ulrik Christian Gyldenløve (1630–1658).

*Elisabeth Sophia Gyldenløve (1633–1654); married Major-General Klaus Ahlefeld.

Gallery

Ancestry

Titles and style

In the 1621 Treaty of The Hague and Treaty of Bremen between Denmark-Norway and the Dutch Republic, Christian was styled "Lord Christian the Fourth, King of list of Danish kings, all Denmark and list of Norwegian kings, Norway, the list of kings of the Goths, Goths and the list of kings of the Wends, Wends, duke of list of dukes of Schleswig, Schleswig, list of dukes of Holstein, Holstein, list of dukes of Stormarn, Stormarn, and list of dukes of Ditmarsh, Ditmarsh, count of list of counts of Oldenburg, Oldenburg and list of counts of Delmenhorst, Delmenhorst, etc.". In Davenport, Frances G. ''European Treaties Bearing on the History of the United States and Its Dependencies''. The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd., 2004.

References

Further reading

* Lockhart, Paul D. ''Denmark in the Thirty Years’ War, 1618–1648: King Christian IV and the Decline of the Oldenburg State'' (Susquehanna University Press, 1996) * Lockhart, Paul D. ''Denmark, 1513–1660: the Rise and Decline of a Renaissance Monarchy'' (Oxford University Press, 2007). * * Scocozza, Benito, ''Christian IV'', 2006External links

The Royal Lineage

at the website of the Danish Monarchy

Christian IV

at the website of the Royal Danish Collection *

Harington's account of the drunken masque.

{{Authority control Christian IV of Denmark, 1577 births 1648 deaths 16th-century monarchs of Denmark 17th-century monarchs of Denmark 16th-century Norwegian monarchs 17th-century Norwegian monarchs People from Hillerød Municipality Dukes of Schleswig Dukes of Holstein Denmark–Norway Danish people of the Thirty Years' War Burials at Roskilde Cathedral Extra Knights Companion of the Garter People of the Kalmar War Children of Frederick II of Denmark