Kōtoku Shūsui on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

, better known by the

In 1903, ''Yorozu Chōhō'' came out in support of war with Russia, as its editor decided to support the upcoming

In 1903, ''Yorozu Chōhō'' came out in support of war with Russia, as its editor decided to support the upcoming

Full text of "Japanese Thought In The Meiji Era Centenary Culture Council Series"

/ref>

e-texts of Kōtoku's works

at

pen name

A pen name or nom-de-plume is a pseudonym (or, in some cases, a variant form of a real name) adopted by an author and printed on the title page or by-line of their works in place of their real name.

A pen name may be used to make the author's na ...

, was a Japanese socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

and anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and Political movement, movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or Social hierarchy, hierarchy, primarily targeting the state (polity), state and capitalism. A ...

who played a leading role in introducing anarchism to Japan in the early 20th century. Historian John Crump described him as "the most famous socialist in Japan".

He was a prominent figure in radical politics in Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

, opposing the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War (8 February 1904 – 5 September 1905) was fought between the Russian Empire and the Empire of Japan over rival imperial ambitions in Manchuria and the Korean Empire. The major land battles of the war were fought on the ...

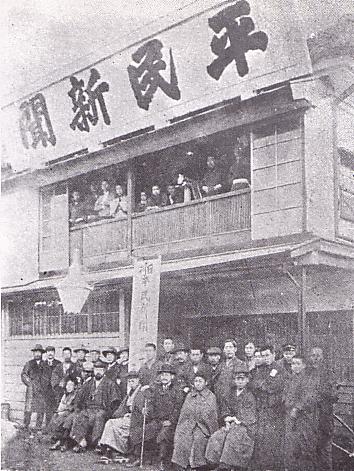

by founding the Heimin-sha group and its associated newspaper, '' Heimin Shinbun''. Due to disregard for state press laws, the newspaper ceased publication in January 1905, and Kōtoku served five months in prison from February to July 1905. He subsequently left for the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

, spending November 1905 until June 1906 largely in California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

, and he came into contact with other prominent anarchist figures such as Peter Kropotkin

Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin (9 December 1842 – 8 February 1921) was a Russian anarchist and geographer known as a proponent of anarchist communism.

Born into an aristocratic land-owning family, Kropotkin attended the Page Corps and later s ...

.

Upon his return, he contributed to a divide within the left-wing movement between moderate social democrats

Social democracy is a social, economic, and political philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy and a gradualist, reformist, and democratic approach toward achieving social equality. In modern practice, s ...

and the more radical advocates of direct action

Direct action is a term for economic and political behavior in which participants use agency—for example economic or physical power—to achieve their goals. The aim of direct action is to either obstruct a certain practice (such as a governm ...

, the latter of whom he supported. The growth of the 'direct action' faction led to the banning of the Japan Socialist Party

The was a major socialist and progressive political party in Japan which existed from 1945 to 1996. The party was the primary representative of the Japanese left and main opponent of the right-wing Liberal Democratic Party for most of its ex ...

in February 1907, and is arguably the beginning of Japan's modern anarchist movement. He was one of the 12 accused who were executed for treason by the Japanese government in the High Treason Incident

The , also known as the , was a socialist-anarchist plot to assassinate the Japanese Emperor Meiji in 1910, leading to a mass arrest of leftists, as well as the execution of 12 alleged conspirators in 1911. Another 12 conspirators who were init ...

in 1911, under suspicion of involvement in a bomb plot to assassinate the Japanese Emperor Meiji

, posthumously honored as , was the 122nd emperor of Japan according to the List of emperors of Japan, traditional order of succession, reigning from 1867 until his death in 1912. His reign is associated with the Meiji Restoration of 1868, which ...

.

Early life

Kōtoku was born in 1871 to a mother who came from a lowersamurai

The samurai () were members of the warrior class in Japan. They were originally provincial warriors who came from wealthy landowning families who could afford to train their men to be mounted archers. In the 8th century AD, the imperial court d ...

family, and to a father who died shortly after his birth. Born in Tosa Province

was a province of Japan in the area of southern Shikoku. Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005). "''Tosa''" in . Tosa bordered on Awa to the northeast, and Iyo to the northwest. Its abbreviated form name was . In terms of the Gokishichidō syst ...

, one of the key supporters of the Meiji Restoration

The , referred to at the time as the , and also known as the Meiji Renovation, Revolution, Regeneration, Reform, or Renewal, was a political event that restored Imperial House of Japan, imperial rule to Japan in 1868 under Emperor Meiji. Althoug ...

, he became influenced by the growing opposition to the new government. Tosa was a hotbed of resistance largely due to the discontent of samurais, whose power was declining, and Kōtoku became at a young age an ardent supporter of the pro-democracy Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world.

The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left. For example, while the political systems ...

.

At the age of 16, his school was destroyed by a typhoon, and he went to Tokyo

Tokyo, officially the Tokyo Metropolis, is the capital of Japan, capital and List of cities in Japan, most populous city in Japan. With a population of over 14 million in the city proper in 2023, it is List of largest cities, one of the most ...

in September 1887 to attend a private school that taught English. There he involved himself in public agitation, driven by the Liberal Party, calling for the abolition of the unequal treaties

The unequal treaties were a series of agreements made between Asian countries—most notably Qing China, Tokugawa Japan and Joseon Korea—and Western countries—most notably the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Italy, the Unit ...

signed between Japan and Western powers, alongside freedom of speech. The government responded by barring more than 500 radicals from coming within seven miles of the Tokyo Imperial Palace

is the main residence of the Emperor of Japan. It is a large park-like area located in the Chiyoda, Chiyoda, Tokyo, Chiyoda district of the Chiyoda, Tokyo, Chiyoda ward of Tokyo and contains several buildings including the where the Emperor h ...

, effectively exiling them from the capital.

As a result of this, he moved to Osaka

is a Cities designated by government ordinance of Japan, designated city in the Kansai region of Honshu in Japan. It is the capital of and most populous city in Osaka Prefecture, and the List of cities in Japan, third-most populous city in J ...

in November 1888, where he became a 'disciple' of the older radical Nakae Chōmin. In the Confucian

Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China, and is variously described as a tradition, philosophy, religion, theory of government, or way of life. Founded by Confucius ...

tradition, Kōtoku was loyal to his 'master', despite his egalitarian beliefs. They returned to Tokyo after an amnesty was issued alongside the new Meiji Constitution

The Constitution of the Empire of Japan ( Kyūjitai: ; Shinjitai: , ), known informally as the Meiji Constitution (, ''Meiji Kenpō''), was the constitution of the Empire of Japan which was proclaimed on February 11, 1889, and remained in ...

of 1889.

Political career

In 1893, Kōtoku became the English translator for the ''Jiyu Shinbun'', the newspaper of a newly reformedLiberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world.

The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left. For example, while the political systems ...

. He left this post in 1895, but still remained under Nakae's tutelage. However, when many liberals united with pro-government supporters of Itō Hirobumi

Kazoku, Prince , born , was a Japanese statesman who served as the first prime minister of Japan from 1885 to 1888, and later from 1892 to 1896, in 1898, and from 1900 to 1901. He was a leading member of the ''genrō'', a group of senior state ...

in 1900 to form the right-wing Rikken Seiyūkai

The was one of the main political party, political parties in the pre-war Empire of Japan. It was also known simply as the ''Seiyūkai''.

Founded on September 15, 1900, by Itō Hirobumi,David S. Spencer, "Some Thoughts on the Political Devel ...

party, Kōtoku became disillusioned with liberalism. He is also described as a radical

Radical (from Latin: ', root) may refer to:

Politics and ideology Politics

*Classical radicalism, the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe and Latin America in the 19th century

*Radical politics ...

or radical-liberal because he supported anti-imperialism and anti-establishment lines, unlike mainstream liberals who defended imperialism at the time.

Socialism

In 1898, he joined the staff of the '' Yorozu Chōhō'' newspaper, wherein he published an article in 1900 condemning war in Manchuria. He published his first book in 1901, titled ''Imperialism,'' ''Monster of the Twentieth Century,'' which was a monumental work in the history of Japanese leftism, criticising both Japanese and Western imperialism from the point of view of a revolutionary socialist. By now a committed socialist, he helped to found theSocial Democratic Party

The name Social Democratic Party or Social Democrats has been used by many political parties in various countries around the world. Such parties are most commonly aligned to social democracy as their political ideology.

Active parties

Form ...

. Despite the party's commitment to parliamentary tactics, it was immediately banned. He wrote another book in 1903, ''Quintessence of Socialism'', acknowledging influence from Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

. He also contributed articles to ''Sekai Fujin'' (''Women of the World''), a socialist women's newspaper.

Anti-war activism

Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War (8 February 1904 – 5 September 1905) was fought between the Russian Empire and the Empire of Japan over rival imperial ambitions in Manchuria and the Korean Empire. The major land battles of the war were fought on the ...

. In protest against this decision, in October 1903 Kōtoku was one of a number of journalists who resigned to found the Heimin-sha group, alongside its associated anti-war '' Heimin Shinbun'' newspaper, which started publication in November.

A year after the founding of ''Heimin Shinbun'', Kōtoku translated and published Marx's ''Communist Manifesto

''The Communist Manifesto'' (), originally the ''Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (), is a political pamphlet written by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, commissioned by the Communist League and originally published in London in 1848. The t ...

'', for which he was fined. The newspaper was soon banned, publishing its last issue in January 1905, and Kōtoku was imprisoned from February to July 1905 for his involvement in the newspaper.

Self-exile

His imprisonment only gave him further opportunities to read leftist literature, and he claimed in August 1905 that "Indeed, I had gone o prisonas a Marxian Socialist and returned as a radical Anarchist." He travelled to the United States in November 1905 and spent until June 1906 in the country. While in America, he spent most of his time in California, and his ideology further radicalised towardsanarcho-communism

Anarchist communism is a far-left political ideology and anarchist school of thought that advocates communism. It calls for the abolition of private real property but retention of personal property and collectively-owned items, goods, and se ...

. He wrote to the anarcho-communist Peter Kropotkin, who gave him permission to translate his works into Japanese in letter dated September 1906. Kōtoku also came into contact with the Industrial Workers of the World

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), whose members are nicknamed "Wobblies", is an international labor union founded in Chicago, United States in 1905. The nickname's origin is uncertain. Its ideology combines general unionism with indu ...

, an anarcho-syndicalist

Anarcho-syndicalism is an anarchist organisational model that centres trade unions as a vehicle for class conflict. Drawing from the theory of libertarian socialism and the practice of syndicalism, anarcho-syndicalism sees trade unions as both ...

union, and became aware of Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman (June 27, 1869 – May 14, 1940) was a Russian-born Anarchism, anarchist revolutionary, political activist, and writer. She played a pivotal role in the development of anarchist political philosophy in North America and Europ ...

's anarchist newspaper '' Mother Earth''.

Before he left California, he founded a Social Revolutionary Party amongst Japanese-American immigrants, which quickly radicalised towards the use of terrorist tactics to bring about the anarchist revolution.

Return to Japan

During his absence, Japanese socialists formed a newJapan Socialist Party

The was a major socialist and progressive political party in Japan which existed from 1945 to 1996. The party was the primary representative of the Japanese left and main opponent of the right-wing Liberal Democratic Party for most of its ex ...

in February 1906. Kōtoku's new, more radical ideas clashed with the parliamentary tactics affirmed by the party, and he advocated for anarchist revolution through direct action rather than electoral strategy. The growth of these ideas led to a split in the party between 'soft' and 'hard' factions (parliamentarians and direct actionists respectively), and the party was banned in February 1907. The growth of the pro-direct action faction is considered the beginning of Japan's modern anarchist movement.

Outside of party politics once more, Kōtoku worked with others to translate and publish Kropotkin's anarcho-communist book ''The Conquest of Bread

''The Conquest of Bread'' is an 1892 book by the Russian anarchist Peter Kropotkin. Originally written in French, it first appeared as a series of articles in the anarchist journal ''Le Révolté''. It was first published in Paris with a pref ...

'', alongside an American anarcho-syndicalist pamphlet ''The Social General Strike''. Unions were banned due to a 1900 law, however, and much anarchist discussion was highly theoretical rather than practical. Nevertheless, Kōtoku was strongly critical of Keir Hardie

James Keir Hardie (15 August 185626 September 1915) was a Scottish trade unionist and politician. He was a founder of the Labour Party (UK), Labour Party, and was its first Leader of the Labour Party (UK), parliamentary leader from 1906 to 1908. ...

when he visited Japan, decrying "Hardie's State Socialism".

Despite being ideologically opposed to hierarchy, Kōtoku was seen as an 'authority' by many younger anarchists due to Japanese cultural norms, and he himself referred to Kropotkin as ''sensei'' (teacher).

High Treason Incident and execution

In 1910, a handful of anarchists, including Kōtoku, were involved in a bomb plot to assassinate the Emperor. The resultantHigh Treason Incident

The , also known as the , was a socialist-anarchist plot to assassinate the Japanese Emperor Meiji in 1910, leading to a mass arrest of leftists, as well as the execution of 12 alleged conspirators in 1911. Another 12 conspirators who were init ...

and trial led to the arrest of hundreds of anarchists, the conviction of 26, and the execution of 12. The trial was rigged by the prosecution, and some of those executed were innocent. The trial and its fallout signalled the start of the of Japanese anarchism, in which left-wing organisations were tightly monitored and controlled, and militants and activists were tailed 24 hours a day by police.

Kōtoku was executed by hanging in January 1911 for treason. His final work was , which he composed in prison. In this book, he claimed that Jesus was a mythical and unreal figure./ref>

Personal life

Even though he had married a decade prior, he began a love affair with Kanno Sugako after her arrest related to the 1908 Red Flag Incident. In November 1908, he was diagnosed with tuberculosis, and began to believe that he did not have long to live. This helped to drive him towards supporting more extremist, violent tactics.See also

* Japanese resistance during the Shōwa period * Oka ShigekiNotes

References

* * * * * * * * * * *External links

e-texts of Kōtoku's works

at

Aozora Bunko

Aozora Bunko (, , also known as the "Open Air Library") is a Japanese digital library. This online collection encompasses several thousand works of Japanese-language fiction and non-fiction. These include out-of-copyright books or works that t ...

{{DEFAULTSORT:Kotoku, Shusui

1871 births

1911 deaths

20th-century anarchists

20th-century executions by Japan

20th-century executions for treason

Anarcho-communists

Executed anarchists

Executed communists

Executed Japanese people

Executed revolutionaries

Japanese anarchists

Japanese communists

Japanese revolutionaries

Japanese socialists

Meiji socialists

People executed for treason against Japan

People executed by Japan by hanging

People from Kōchi Prefecture

People of the Meiji era

Radicals