Kurile Islands on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

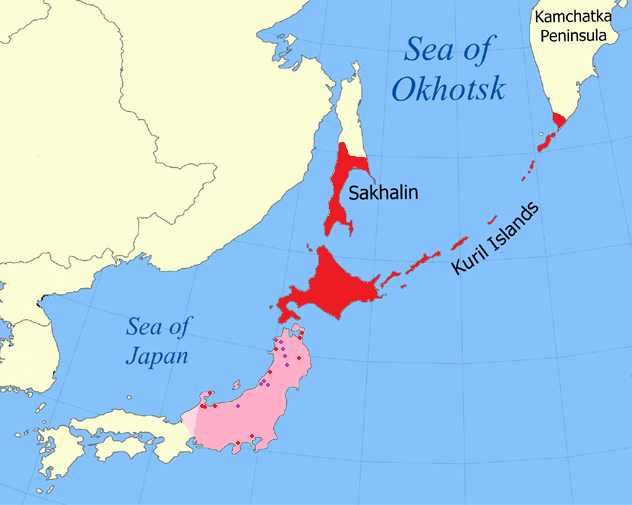

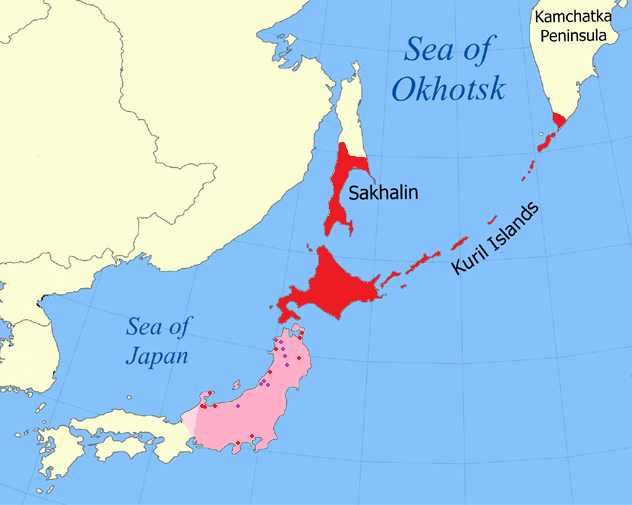

The Kuril Islands or Kurile Islands (; rus, Кури́льские острова́, r=Kuril'skiye ostrova, p=kʊˈrʲilʲskʲɪjə ɐstrɐˈva;

The Kuril Islands form part of the ring of

The Kuril Islands form part of the ring of

The

The

At the very end of the 19th century, the Japanese administration started the forced

At the very end of the 19th century, the Japanese administration started the forced

* American planners had briefly contemplated an invasion of northern Japan from the

* American planners had briefly contemplated an invasion of northern Japan from the

, 19,434 people inhabited the Kuril Islands, of which over 16,700 live on the four disputed islands. These include ethnic

, 19,434 people inhabited the Kuril Islands, of which over 16,700 live on the four disputed islands. These include ethnic

Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

: or ) are a volcanic archipelago

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands, or sometimes a sea containing a small number of scattered islands.

Examples of archipelagos include: the Indonesian Archi ...

currently administered as part of Sakhalin Oblast

Sakhalin Oblast ( rus, Сахали́нская о́бласть, r=Sakhalínskaya óblast', p=səxɐˈlʲinskəjə ˈobləsʲtʲ) is a federal subject of Russia (an oblast) comprising the island of Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands in the Rus ...

in the Russian Far East

The Russian Far East (russian: Дальний Восток России, r=Dal'niy Vostok Rossii, p=ˈdalʲnʲɪj vɐˈstok rɐˈsʲiɪ) is a region in Northeast Asia. It is the easternmost part of Russia and the Asian continent; and is admin ...

. It stretches approximately northeast from Hokkaido

is Japan, Japan's Japanese archipelago, second largest island and comprises the largest and northernmost Prefectures of Japan, prefecture, making up its own List of regions of Japan, region. The Tsugaru Strait separates Hokkaidō from Honshu; th ...

in Japan to Kamchatka Peninsula

The Kamchatka Peninsula (russian: полуостров Камчатка, Poluostrov Kamchatka, ) is a peninsula in the Russian Far East, with an area of about . The Pacific Ocean and the Sea of Okhotsk make up the peninsula's eastern and we ...

in Russia separating the Sea of Okhotsk

The Sea of Okhotsk ( rus, Охо́тское мо́ре, Ohótskoye móre ; ja, オホーツク海, Ohōtsuku-kai) is a marginal sea of the western Pacific Ocean. It is located between Russia's Kamchatka Peninsula on the east, the Kuril Islands ...

from the north Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contine ...

. There are 56 islands and many minor rocks. The Kuril Islands consist of the Greater Kuril Chain

Greater Kuril Chain (russian: Большая Курильская гряда) - A part of the Kuril Islands, the Greater Kuril Chain is a group of islands in the Pacific Ocean. It includes North Kurils, Iturup and Kunashir.

At its south western e ...

and the Lesser Kuril Chain

The Lesser Kuril Chain (russian: Малая Курильская гряда, ja, しょうクリルれっとう or 小千島列島), is an island chain in the northwestern Pacific Ocean. The islands are administered as part of Yuzhno-Kurilsky Dis ...

. They cover an area of around , with a population of roughly 20,000.

The islands have been under Russian administration since their 1945 invasion as the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

towards the end of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. Japan claims the four southernmost islands, including two of the three largest (Iturup

, other_names = russian: Итуру́п; ja, 択捉島

, location = Sea of Okhotsk

, coordinates =

, archipelago = Kuril Islands

, total_islands =

, major_islands =

, area_km2 = 3139

, length_km = 200

, width_km = 27

, coastline =

, highest_moun ...

and Kunashir

, other_names = kz, Kün Ashyr; ja, 国後島

, location = Sea of Okhotsk

, locator_map = File:Kurily Kunashir.svg

, coordinates =

, archipelago = Kuril Islands

, total_islands =

, major_islands =

, area =

, length =

, width = fr ...

), as part of its territory, as well as Shikotan

; ja, 色丹島

, location = Pacific Ocean

, coordinates =

, archipelago = Kuril Islands

, total_islands = 1

, major_islands =

, area_km2 = 225

, length =

, width =

, coastline ...

and the Habomai

; ja, 歯舞群島, Habomai guntō

, location = Pacific Ocean

, coordinates =

, archipelago = Kuril Islands

, total_islands = 10 + several rocks

, major_islands =

, area_km2 = 100

, length =

, ...

islets, which has led to the ongoing Kuril Islands dispute

The Kuril Islands dispute, known as the Northern Territories dispute in Japan, is a territorial dispute between Japan and Russia over the ownership of the four southernmost Kuril Islands. The Kuril Islands are a chain of islands that stretc ...

. The disputed islands are known in Japan as the country's "Northern Territories".

Etymology

The name ''Kuril'' originates from the autonym of the aboriginalAinu

Ainu or Aynu may refer to:

*Ainu people, an East Asian ethnic group of Japan and the Russian Far East

*Ainu languages, a family of languages

**Ainu language of Hokkaido

**Kuril Ainu language, extinct language of the Kuril Islands

**Sakhalin Ainu la ...

, the islands' original inhabitants: ''kur'', meaning 'man'. It may also be related to names for other islands that have traditionally been inhabited by the Ainu people, such as ''Kuyi'' or ''Kuye'' for Sakhalin

Sakhalin ( rus, Сахали́н, r=Sakhalín, p=səxɐˈlʲin; ja, 樺太 ''Karafuto''; zh, c=, p=Kùyèdǎo, s=库页岛, t=庫頁島; Manchu: ᠰᠠᡥᠠᠯᡳᠶᠠᠨ, ''Sahaliyan''; Orok: Бугата на̄, ''Bugata nā''; Nivkh: ...

and ''Kai'' for Hokkaidō. In Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

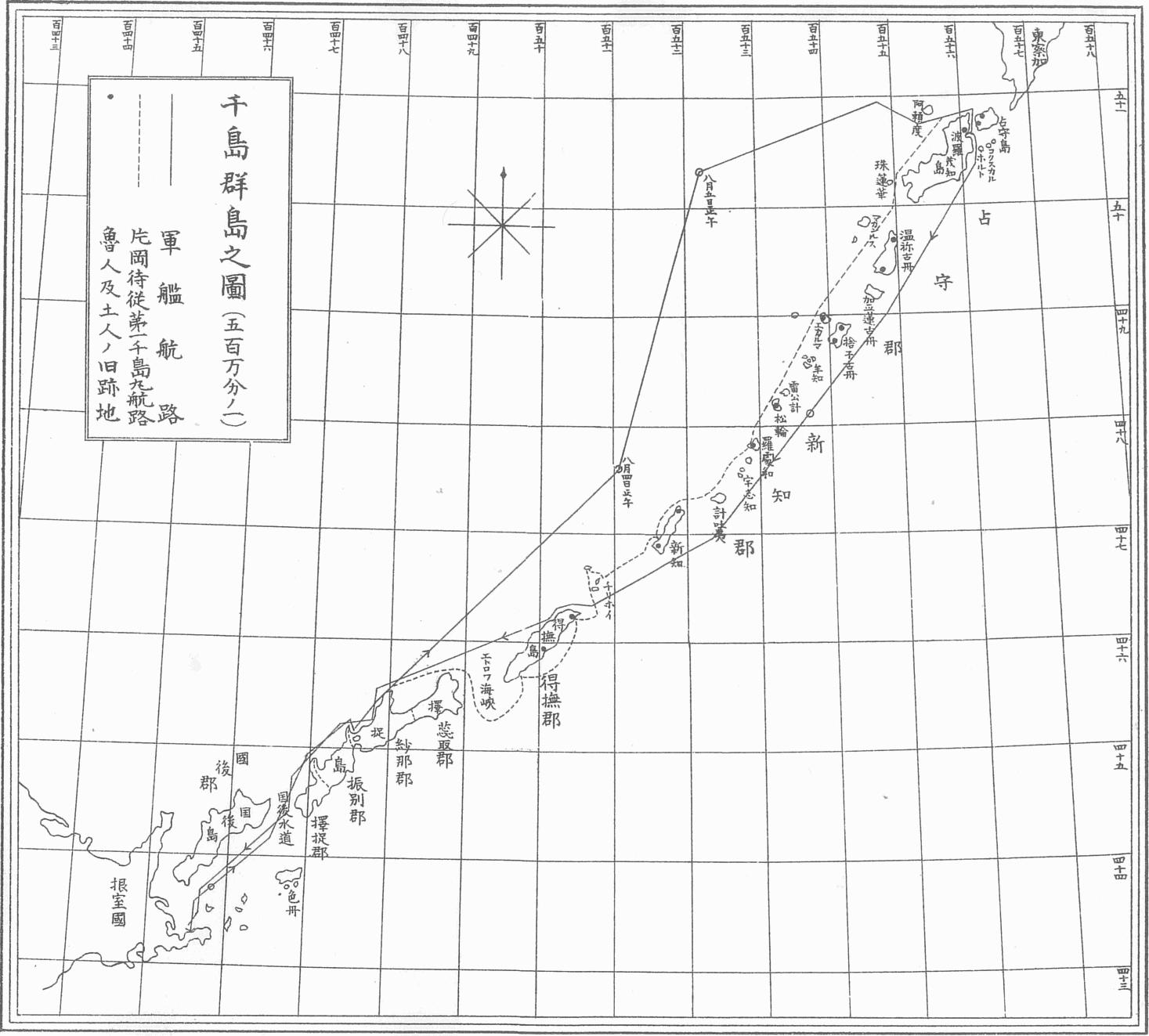

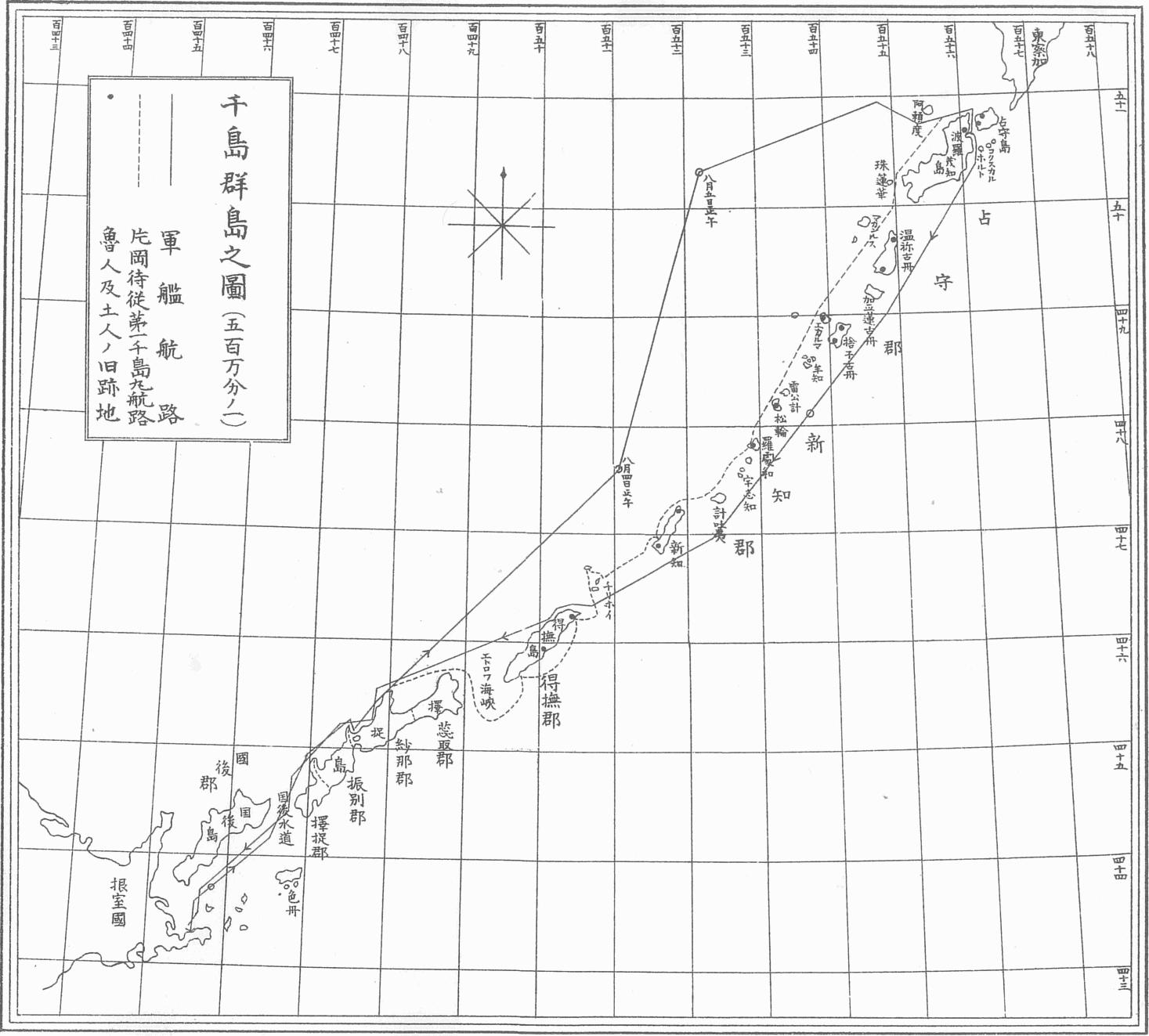

, the Kuril Islands are known as the Chishima Islands (Kanji

are the logographic Chinese characters taken from the Chinese script and used in the writing of Japanese. They were made a major part of the Japanese writing system during the time of Old Japanese and are still used, along with the subse ...

: , literally, 'Thousand Islands Archipelago'), also known as the Kuriru Islands (Katakana

is a Japanese syllabary, one component of the Japanese writing system along with hiragana, kanji and in some cases the Latin script (known as rōmaji). The word ''katakana'' means "fragmentary kana", as the katakana characters are derived f ...

: , literally, ''Kuril Archipelago''). Once the Russians reached the islands in the 18th century they found a pseudo-etymology from Russian ''kurit′'', курить 'to smoke' due to the continual fumes and steam above the islands from volcanoes.

Geography and climate

The Kuril Islands form part of the ring of

The Kuril Islands form part of the ring of tectonic

Tectonics (; ) are the processes that control the structure and properties of the Earth's crust and its evolution through time. These include the processes of mountain building, the growth and behavior of the strong, old cores of continents ...

instability encircling the Pacific Ocean referred to as the Ring of Fire

The Ring of Fire (also known as the Pacific Ring of Fire, the Rim of Fire, the Girdle of Fire or the Circum-Pacific belt) is a region around much of the rim of the Pacific Ocean where many volcanic eruptions and earthquakes occur. The Ring ...

. The islands themselves are summits of stratovolcano

A stratovolcano, also known as a composite volcano, is a conical volcano built up by many layers (strata) of hardened lava and tephra. Unlike shield volcanoes, stratovolcanoes are characterized by a steep profile with a summit crater and p ...

es that are a direct result of the subduction of the Pacific Plate

The Pacific Plate is an oceanic tectonic plate that lies beneath the Pacific Ocean. At , it is the largest tectonic plate.

The plate first came into existence 190 million years ago, at the triple junction between the Farallon, Phoenix, and I ...

under the Okhotsk Plate, which forms the Kuril Trench some east of the islands. The chain has around 100 volcanoes, some 40 of which are active, and many hot springs

A hot spring, hydrothermal spring, or geothermal spring is a spring produced by the emergence of geothermally heated groundwater onto the surface of the Earth. The groundwater is heated either by shallow bodies of magma (molten rock) or by c ...

and fumaroles

A fumarole (or fumerole) is a vent in the surface of the Earth or other rocky planet from which hot volcanic gases and vapors are emitted, without any accompanying liquids or solids. Fumaroles are characteristic of the late stages of volcani ...

. There is frequent seismic activity, including a magnitude 8.5 earthquake in 1963 and one of magnitude 8.3 recorded on November 15, 2006, which resulted in tsunami

A tsunami ( ; from ja, 津波, lit=harbour wave, ) is a series of waves in a water body caused by the displacement of a large volume of water, generally in an ocean or a large lake. Earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and other underwater exp ...

waves up to reaching the California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the ...

coast. Raikoke Island, near the centre of the archipelago, has an active volcano which erupted again in June 2019, with emissions reaching .

The climate on the islands is generally severe, with long, cold, stormy winters and short and notoriously foggy summers. The average annual precipitation is , a large portion of which falls as snow. The Köppen climate classification

The Köppen climate classification is one of the most widely used climate classification systems. It was first published by German-Russian climatologist Wladimir Köppen (1846–1940) in 1884, with several later modifications by Köppen, nota ...

of most of the Kurils is subarctic (''Dfc''), although Kunashir

, other_names = kz, Kün Ashyr; ja, 国後島

, location = Sea of Okhotsk

, locator_map = File:Kurily Kunashir.svg

, coordinates =

, archipelago = Kuril Islands

, total_islands =

, major_islands =

, area =

, length =

, width = fr ...

is humid continental (''Dfb''). However, the Kuril Islands’ climate resembles the subpolar oceanic climate

An oceanic climate, also known as a marine climate, is the humid temperate climate sub-type in Köppen classification ''Cfb'', typical of west coasts in higher middle latitudes of continents, generally featuring cool summers and mild winters ...

of southwest Alaska

Southwest Alaska is a region of the U.S. state of Alaska. The area is not exactly defined by any governmental administrative region(s); nor does it always have a clear geographic boundary.

Geography

Southwest Alaska includes a huge, complex, and ...

much more than the hypercontinental climate of Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym "Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East ( Outer ...

and interior Siberia, as precipitation is heavy and permafrost completely absent. It is characterized by mild summers with only 1 to 3 months above and cold, snowy, extremely windy winters below , although usually above .

The chain ranges from temperate to sub-Arctic climate types, and the vegetative cover consequently ranges from tundra

In physical geography, tundra () is a type of biome where tree growth is hindered by frigid temperatures and short growing seasons. The term ''tundra'' comes through Russian (') from the Kildin Sámi word (') meaning "uplands", "treeless mo ...

in the north to dense spruce

A spruce is a tree of the genus ''Picea'' (), a genus of about 35 species of coniferous evergreen trees in the family Pinaceae, found in the northern temperate and boreal ( taiga) regions of the Earth. ''Picea'' is the sole genus in the sub ...

and larch

Larches are deciduous conifers in the genus ''Larix'', of the family Pinaceae (subfamily Laricoideae). Growing from tall, they are native to much of the cooler temperate northern hemisphere, on lowlands in the north and high on mountains furt ...

forests on the larger southern islands. The highest elevations on the islands are Alaid volcano (highest point: ) on Atlasov Island at the northern end of the chain and Tyatya volcano () on Kunashir Island at the southern end.

Landscape types and habitats on the islands include many kinds of beach and rocky shores, cliffs, wide rivers and fast gravelly streams, forests, grasslands, alpine tundra

Alpine tundra is a type of natural region or biome that does not contain trees because it is at high elevation, with an associated harsh climate. As the latitude of a location approaches the poles, the threshold elevation for alpine tundra gets ...

, crater lake

Crater Lake (Klamath: ''Giiwas'') is a volcanic crater lake in south-central Oregon in the western United States. It is the main feature of Crater Lake National Park and is famous for its deep blue color and water clarity. The lake partly fills ...

s and peat bogs

A bog or bogland is a wetland that accumulates peat as a deposit of dead plant materials often mosses, typically sphagnum moss. It is one of the four main types of wetlands. Other names for bogs include mire, mosses, quagmire, and muskeg; ...

. The soils are generally productive, owing to the periodic influxes of volcanic ash and, in certain places, owing to significant enrichment by seabird

Seabirds (also known as marine birds) are birds that are adapted to life within the marine environment. While seabirds vary greatly in lifestyle, behaviour and physiology, they often exhibit striking convergent evolution, as the same envir ...

guano

Guano (Spanish from qu, wanu) is the accumulated excrement of Seabird, seabirds or bats. As a manure, guano is a highly effective fertilizer due to the high content of nitrogen, phosphate, and potassium, all key nutrients essential for plant ...

. However, many of the steep, unconsolidated slopes are susceptible to landslides and newer volcanic activity can entirely denude a landscape. Only the southernmost island has large areas covered by trees, while more northerly islands have no trees, or spotty tree cover.

The northernmost, Atlasov Island (Oyakoba in Japanese), is an almost-perfect volcanic

A volcano is a rupture in the crust of a planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface.

On Earth, volcanoes are most often found where tectonic plates ...

cone rising sheer out of the sea; it has been praised by the Japanese in haiku

is a type of short form poetry originally from Japan. Traditional Japanese haiku consist of three phrases that contain a ''kireji'', or "cutting word", 17 ''On (Japanese prosody), on'' (phonetic units similar to syllables) in a 5, 7, 5 pattern, ...

, wood-block print

Woodblock printing or block printing is a technique for printing text, images or patterns used widely throughout East Asia and originating in China in antiquity as a method of printing on textiles and later paper. Each page or image is crea ...

s, and other forms, in much the same way as the better-known Mount Fuji

, or Fugaku, located on the island of Honshū, is the highest mountain in Japan, with a summit elevation of . It is the second-highest volcano located on an island in Asia (after Mount Kerinci on the island of Sumatra), and seventh-highes ...

. Its summit is the highest point in Sakhalin Oblast

Sakhalin Oblast ( rus, Сахали́нская о́бласть, r=Sakhalínskaya óblast', p=səxɐˈlʲinskəjə ˈobləsʲtʲ) is a federal subject of Russia (an oblast) comprising the island of Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands in the Rus ...

.

Ecology

Marine

Owing to their location along the Pacific shelf edge and the confluence of Okhotsk Sea gyre and the southwardOyashio Current

, also known as Oya Siwo, Okhotsk or the Kurile current, is a cold subarctic ocean current that flows south and circulates counterclockwise in the western North Pacific Ocean. The waters of the Oyashio Current originate in the Arctic Ocean an ...

, the Kuril islands are surrounded by waters that are among the most productive in the North Pacific, supporting a wide range and high abundance of marine life.

Invertebrates

Invertebrates are a paraphyletic group of animals that neither possess nor develop a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''backbone'' or ''spine''), derived from the notochord. This is a grouping including all animals apart from the chordate ...

: Extensive kelp

Kelps are large brown algae seaweeds that make up the order Laminariales. There are about 30 different genera. Despite its appearance, kelp is not a plant - it is a heterokont, a completely unrelated group of organisms.

Kelp grows in "under ...

beds surrounding almost every island provide crucial habitat for sea urchins

Sea urchins () are spiny, globular echinoderms in the class Echinoidea. About 950 species of sea urchin live on the seabed of every ocean and inhabit every depth zone from the intertidal seashore down to . The spherical, hard shells (tests) of ...

, various mollusks

Mollusca is the second-largest phylum of invertebrate animals after the Arthropoda, the members of which are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 85,000 extant species of molluscs are recognized. The number of fossil species is esti ...

and countless other invertebrates and their associated predators. Many species of squid

True squid are molluscs with an elongated soft body, large eyes, eight arms, and two tentacles in the superorder Decapodiformes, though many other molluscs within the broader Neocoleoidea are also called squid despite not strictly fitting ...

provide a principal component of the diet of many of the smaller marine mammals and birds along the chain.

Fish

Fish are aquatic, craniate, gill-bearing animals that lack limbs with digits. Included in this definition are the living hagfish, lampreys, and cartilaginous and bony fish as well as various extinct related groups. Approximately 95% ...

: Further offshore, walleye pollock, Pacific cod, several species of flatfish

A flatfish is a member of the ray-finned demersal fish order Pleuronectiformes, also called the Heterosomata, sometimes classified as a suborder of Perciformes. In many species, both eyes lie on one side of the head, one or the other migratin ...

are of the greatest commercial importance. During the 1980s, migratory Japanese sardine

"Sardine" and "pilchard" are common names for various species of small, oily forage fish in the herring family Clupeidae. The term "sardine" was first used in English during the early 15th century, a folk etymology says it comes from the ...

was one of the most abundant fish in the summer.

Pinniped

Pinnipeds (pronounced ), commonly known as seals, are a widely range (biology), distributed and diverse clade of carnivorous, fin-footed, semiaquatic, mostly marine mammal, marine mammals. They comprise the extant taxon, extant family (biology ...

: The main pinnipeds were a significant object of harvest for the indigenous populations of the Kuril islands, both for food and materials such as skin and bone. The long-term fluctuations in the range and distribution of human settlements along the Kuril island presumably tracked the pinniped ranges. In historical times, fur seals were heavily exploited for their fur in the 19th and early 20th centuries and several of the largest reproductive rookeries, as on Raykoke

Raikoke (russian: Райкоке, ja, 雷公計島), also spelled Raykoke, is, as of 2019 a Russian uninhabited volcanic island near the centre of the Kuril Islands chain in the Sea of Okhotsk in the northwest Pacific Ocean, distant from the is ...

island, were extirpated. In contrast, commercial harvest of the true seals and Steller sea lion

The Steller sea lion (''Eumetopias jubatus''), also known as the Steller's sea lion and northern sea lion, is a near-threatened species of sea lion in the northern Pacific. It is the sole member of the genus ''Eumetopias'' and the largest of ...

s has been relatively insignificant on the Kuril islands proper. Since the 1960s there has been essentially no additional harvest and the pinniped populations in the Kuril islands appear to be fairly healthy and in some cases expanding. The notable exception is the now extinct Japanese sea lion, which was known to occasionally haul out

Hauling-out is a behaviour associated with pinnipeds (true seals, sea lions, fur seals and walruses) temporarily leaving the water. Hauling-out typically occurs between periods of foraging activity. Rather than remain in the water, pinnipeds hau ...

on the Kuril islands.

Sea otters: Sea otters were exploited very heavily for their pelts in the 19th century, as shown by 19th- and 20th-century whaling catch and sighting records.

Seabirds

Seabirds (also known as marine birds) are birds that are adapted to life within the marine environment. While seabirds vary greatly in lifestyle, behaviour and physiology, they often exhibit striking convergent evolution, as the same environ ...

: The Kuril islands are home to many millions of seabirds, including northern fulmar

The northern fulmar (''Fulmarus glacialis''), fulmar, or Arctic fulmar is a highly abundant seabird found primarily in subarctic regions of the North Atlantic and North Pacific oceans. There has been one confirmed sighting in the Southern Hem ...

s, tufted puffin

The tufted puffin (''Fratercula cirrhata''), also known as crested puffin, is a relatively abundant medium-sized pelagic seabird in the auk family (Alcidae) found throughout the North Pacific Ocean.

It is one of three species of puffin that make ...

s, murres, kittiwakes, guillemot

Guillemot is the common name for several species of seabird in the Alcidae or auk family (part of the order Charadriiformes). In British use, the term comprises two genera: '' Uria'' and '' Cepphus''. In North America the ''Uria'' species a ...

s, auklets, petrel

Petrels are tube-nosed seabirds in the bird order Procellariiformes.

Description

The common name does not indicate relationship beyond that point, as "petrels" occur in three of the four families within that group (all except the albatross ...

s, gull

Gulls, or colloquially seagulls, are seabirds of the family Laridae in the suborder Lari. They are most closely related to the terns and skimmers and only distantly related to auks, and even more distantly to waders. Until the 21st century, ...

s and cormorant

Phalacrocoracidae is a family of approximately 40 species of aquatic birds commonly known as cormorants and shags. Several different classifications of the family have been proposed, but in 2021 the IOC adopted a consensus taxonomy of seven ge ...

s. On many of the smaller islands in summer, where terrestrial predators are absent, virtually every possibly hummock, cliff niche or underneath of boulder is occupied by a nesting bird. Several of the islands, including Kunashir and the Lesser Kuril Chain in the South Kurils, and the northern Kurils from Urup to Paramushir, have been recognised as Important Bird Area

An Important Bird and Biodiversity Area (IBA) is an area identified using an internationally agreed set of criteria as being globally important for the conservation of bird populations.

IBA was developed and sites are identified by BirdLife Int ...

s (IBAs) by BirdLife International

BirdLife International is a global partnership of non-governmental organizations that strives to conserve birds and their habitats. BirdLife International's priorities include preventing extinction of bird species, identifying and safeguarding ...

because they support populations of various threatened

Threatened species are any species (including animals, plants and fungi) which are vulnerable to endangerment in the near future. Species that are threatened are sometimes characterised by the population dynamics measure of ''critical depensa ...

bird species, including many waterbird

A water bird, alternatively waterbird or aquatic bird, is a bird that lives on or around water. In some definitions, the term ''water bird'' is especially applied to birds in freshwater ecosystems, although others make no distinction from seab ...

s, seabird

Seabirds (also known as marine birds) are birds that are adapted to life within the marine environment. While seabirds vary greatly in lifestyle, behaviour and physiology, they often exhibit striking convergent evolution, as the same envir ...

s and wader

245px, A flock of Red_knot.html" ;"title="Dunlins and Red knot">Dunlins and Red knots

Waders or shorebirds are birds of the order Charadriiformes commonly found wikt:wade#Etymology 1, wading along shorelines and mudflats in order to foraging, ...

s.

Terrestrial

The composition of terrestrial species on the Kuril islands is dominated by Asian mainland taxa via migration from Hokkaido andSakhalin

Sakhalin ( rus, Сахали́н, r=Sakhalín, p=səxɐˈlʲin; ja, 樺太 ''Karafuto''; zh, c=, p=Kùyèdǎo, s=库页岛, t=庫頁島; Manchu: ᠰᠠᡥᠠᠯᡳᠶᠠᠨ, ''Sahaliyan''; Orok: Бугата на̄, ''Bugata nā''; Nivkh: ...

Islands and by Kamchatkan taxa from the North. While highly diverse, there is a relatively low level of endemism

Endemism is the state of a species being found in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also found els ...

on a species level.

The WWF divides the Kuril Islands into two ecoregion

An ecoregion (ecological region) or ecozone (ecological zone) is an ecologically and geographically defined area that is smaller than a bioregion, which in turn is smaller than a biogeographic realm. Ecoregions cover relatively large areas o ...

s. The southern Kurils, along with southwestern Sakhalin

Sakhalin ( rus, Сахали́н, r=Sakhalín, p=səxɐˈlʲin; ja, 樺太 ''Karafuto''; zh, c=, p=Kùyèdǎo, s=库页岛, t=庫頁島; Manchu: ᠰᠠᡥᠠᠯᡳᠶᠠᠨ, ''Sahaliyan''; Orok: Бугата на̄, ''Bugata nā''; Nivkh: ...

, comprise the South Sakhalin-Kurile mixed forests

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþaz' ...

ecoregion. The northern islands are part of the Kamchatka-Kurile meadows and sparse forests, a larger ecoregion that extends onto the Kamchatka Peninsula

The Kamchatka Peninsula (russian: полуостров Камчатка, Poluostrov Kamchatka, ) is a peninsula in the Russian Far East, with an area of about . The Pacific Ocean and the Sea of Okhotsk make up the peninsula's eastern and we ...

and Commander Islands

The Commander Islands, Komandorski Islands, or Komandorskie Islands (russian: Командо́рские острова́, ''Komandorskiye ostrova'') are a series of treeless, sparsely populated Russian islands in the Bering Sea located about e ...

.

Because of the generally smaller size and isolation of the central islands, few major terrestrial mammals have colonized these, though red and Arctic

The Arctic ( or ) is a polar region located at the northernmost part of Earth. The Arctic consists of the Arctic Ocean, adjacent seas, and parts of Canada ( Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut), Danish Realm ( Greenland), Finland, Iceland ...

fox

Foxes are small to medium-sized, omnivorous mammals belonging to several genera of the family Canidae. They have a flattened skull, upright, triangular ears, a pointed, slightly upturned snout, and a long bushy tail (or ''brush'').

Twelv ...

es were introduced for the sake of the fur trade in the 1880s. The bulk of the terrestrial mammal biomass is taken up by rodents

Rodents (from Latin , 'to gnaw') are mammals of the order Rodentia (), which are characterized by a single pair of continuously growing incisors in each of the upper and lower jaws. About 40% of all mammal species are rodents. They are na ...

, many introduced in historical times. The largest southernmost and northernmost islands are inhabited by brown bear

The brown bear (''Ursus arctos'') is a large bear species found across Eurasia and North America. In North America, the populations of brown bears are called grizzly bears, while the subspecies that inhabits the Kodiak Islands of Alaska is ...

, foxes

Foxes are small to medium-sized, omnivorous mammals belonging to several genera of the family Canidae. They have a flattened skull, upright, triangular ears, a pointed, slightly upturned snout, and a long bushy tail (or ''brush'').

Twelv ...

, and martens. Leopard

The leopard (''Panthera pardus'') is one of the five extant species in the genus '' Panthera'', a member of the cat family, Felidae. It occurs in a wide range in sub-Saharan Africa, in some parts of Western and Central Asia, Southern Russia ...

s once inhabited the islands. Some species of deer

Deer or true deer are hoofed ruminant mammals forming the family Cervidae. The two main groups of deer are the Cervinae, including the muntjac, the elk (wapiti), the red deer, and the fallow deer; and the Capreolinae, including the ...

are found on the more southerly islands. It is claimed that a wild cat, the Kurilian Bobtail, originates from the Kuril Islands. The bobtail is due to the mutation of a dominant gene. The cat has been domesticated and exported to nearby Russia and bred there, becoming a popular domestic cat.

Among terrestrial birds, raven

A raven is any of several larger-bodied bird species of the genus ''Corvus''. These species do not form a single taxonomic group within the genus. There is no consistent distinction between "crows" and "ravens", common names which are assigned ...

s, peregrine falcon

The peregrine falcon (''Falco peregrinus''), also known as the peregrine, and historically as the duck hawk in North America, is a cosmopolitan bird of prey ( raptor) in the family Falconidae. A large, crow-sized falcon, it has a blue-grey ...

s, some wren

Wrens are a family of brown passerine birds in the predominantly New World family Troglodytidae. The family includes 88 species divided into 19 genera. Only the Eurasian wren occurs in the Old World, where, in Anglophone regions, it is commonl ...

s and wagtail

Wagtails are a group of passerine birds that form the genus ''Motacilla'' in the family Motacillidae. The forest wagtail belongs to the monotypic genus ''Dendronanthus'' which is closely related to ''Motacilla'' and sometimes included therein. ...

s are common.

History

Early history

The

The Ainu people

The Ainu are the indigenous people of the lands surrounding the Sea of Okhotsk, including Hokkaido Island, Northeast Honshu Island, Sakhalin Island, the Kuril Islands, the Kamchatka Peninsula and Khabarovsk Krai, before the arrival of the ...

inhabited the Kuril Islands from early times, although few records predate the 17th century.From the Kamakura period to the Muromachi period, there were Ezo (Ainu) people called Hinomoto from the Pacific coast of Hokkaido to the Kuril region, and Mr. Ando, the Ezo Sateshiku and Ezo Kanrei, was in charge of this ("Suwa Daimyojin Ekotoba"). ). It is said that when turmoil broke out on Ezogashima, he dispatched troops from Tsugaru. Its activities include the Kanto Gomensen, which calls itself the Ando Suigun, and is based in Jusanminato ("Kaisen Shikimoku"), supplying Japanese products to Ezo society and purchasing large quantities of northern products and shipping them nationwide. ("Thirteen Streets").The Matsumae clan, a feudal lord of Japan, became independent from the Ando clan (the family of Goro Ando). The Japanese administration first took nominal control of the islands during the Edo period

The or is the period between 1603 and 1867 in the history of Japan, when Japan was under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate and the country's 300 regional ''daimyo''. Emerging from the chaos of the Sengoku period, the Edo period was character ...

(1603-1868) in the form of claims by the Matsumae clan

The was a Japanese clan that was confirmed in the possession of the area around Matsumae, Hokkaidō as a march fief in 1590 by Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and charged with defending it, and by extension the whole of Japan, from the Ainu "barbarians" ...

. The '' Shōhō Era Map of Japan'' (), a map of Japan made by the Tokugawa shogunate

The Tokugawa shogunate (, Japanese 徳川幕府 ''Tokugawa bakufu''), also known as the , was the military government of Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in ...

in 1644, shows 39 large and small islands northeast of Hokkaido's Shiretoko Peninsula

is located on the easternmost portion of the Japanese island of Hokkaidō, protruding into the Sea of Okhotsk. It is separated from Kunashir Island, which is now occupied by Russia, by the Nemuro Strait. The name Shiretoko is derived from the ...

and Cape Nosappu. A Dutch expedition under Maarten Gerritsz Vries explored the islands in 1643. Russian popular legend has Fedot Alekseyevich Popov

Fedot Alekseyevich Popov (russian: Федот Алексеевич Попов, also Fedot Alekseyev, russian: Федот Алексеев; nickname Kholmogorian, russian: Холмогорец, for his place of birth ( Kholmogory), date of birth un ...

sailing into the area .

Russian Cossacks landed on Shumshu in 1711.

American whaleships caught right whales off the islands between 1847 and 1892. Three of the ships were wrecked on the islands: two on Urup in 1855 and one on Makanrushi in 1856. In September 1892, north of Kunashir Island, a Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eigh ...

n schooner

A schooner () is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than the mainmast. A common variant, the topsail schoo ...

seized the bark ''Cape Horn Pigeon'', of New Bedford

New Bedford (Massachusett: ) is a city in Bristol County, Massachusetts. It is located on the Acushnet River in what is known as the South Coast region. Up through the 17th century, the area was the territory of the Wampanoag Native American pe ...

and escorted it to Vladivostok

Vladivostok ( rus, Владивосто́к, a=Владивосток.ogg, p=vɫədʲɪvɐˈstok) is the largest city and the administrative center of Primorsky Krai, Russia. The city is located around the Zolotoy Rog, Golden Horn Bay on the Sea ...

, where it was detained for nearly two weeks.

Japanese administration

assimilation

Assimilation may refer to:

Culture

*Cultural assimilation, the process whereby a minority group gradually adapts to the customs and attitudes of the prevailing culture and customs

**Language shift, also known as language assimilation, the progre ...

of the native Ainu people. Also at this time the Ainu were granted automatic Japanese citizenship, effectively denying them the status of an indigenous group. Many Japanese moved onto former Ainu lands, including the Kuril islands. The Ainu required to adopt Japanese names, and ordered to cease religious practices such as animal sacrifice and the custom of tattooing. Although not compulsory education, education was conducted in Japanese. Prior to Japanese colonization (in 1868) about 100 Ainu reportedly lived on the Kuril islands.

World War II

* In 1941 AdmiralIsoroku Yamamoto

was a Marshal Admiral of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) and the commander-in-chief of the Combined Fleet during World War II until he was killed.

Yamamoto held several important posts in the IJN, and undertook many of its changes and reor ...

ordered the assembly of the Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, when it was dissolved following Japan's surrender ...

strike-force for the Hawaii Operation attack on Pearl Harbor in Tankan or Hitokappu

Kasatka Bay ( rus, Залив Касатка, Zaliv Kasatka), formerly known by its Japanese name , is a natural harbor at the central part of Iturup, Kuril Islands. It has been controlled by the Soviet Union since the Soviets annexed the Kuril ...

Bay, Iturup

, other_names = russian: Итуру́п; ja, 択捉島

, location = Sea of Okhotsk

, coordinates =

, archipelago = Kuril Islands

, total_islands =

, major_islands =

, area_km2 = 3139

, length_km = 200

, width_km = 27

, coastline =

, highest_moun ...

Island, South Kurils. The territory was chosen for its sparse population, lack of foreigners, and constant fog-coverage. The Admiral ordered the move to Hawaii on the morning of 26 November.

* On 10 July 1943 the first bombardment against the Japanese bases in Shumshu and Paramushir

russian: Парамушир ja, 幌筵島

, native_name_link =

, nickname =

, location = Pacific Ocean

, coordinates =

, archipelago = Kuril Island

, total_islands =

, major_islands =

, area_km2 = 2053

, length_km = 100

, width_km = 20

, ...

by American forces occurred. From Alexai airfield 8 B-25 Mitchell

The North American B-25 Mitchell is an American medium bomber that was introduced in 1941 and named in honor of Major General William "Billy" Mitchell, a pioneer of U.S. military aviation. Used by many Allied air forces, the B-25 served in ...

s from the 77th Bombardment Squadron took off, led by Capt James L. Hudelson. This mission principally struck Paramushir.

* Another mission was flown during 11 September 1943 when the Eleventh Air Force

The Eleventh Air Force (11 AF) is a Numbered Air Force of the United States Air Force Pacific Air Forces (PACAF). It is headquartered at Joint Base Elmendorf–Richardson, Alaska.This unit is not related to the Eleventh Air Force headquarte ...

dispatched eight B-24 Liberator

The Consolidated B-24 Liberator is an American heavy bomber, designed by Consolidated Aircraft of San Diego, California. It was known within the company as the Model 32, and some initial production aircraft were laid down as export models d ...

s and 12 B-25

The North American B-25 Mitchell is an American medium bomber that was introduced in 1941 and named in honor of Major General William "Billy" Mitchell, a pioneer of U.S. military aviation. Used by many Allied air forces, the B-25 served in ...

s. Facing reinforced Japanese defenses, 74 crew members in three B-24s and seven B-25 failed to return. 22 men were killed in action, one taken prisoner and 51 interned in Kamchatka

The Kamchatka Peninsula (russian: полуостров Камчатка, Poluostrov Kamchatka, ) is a peninsula in the Russian Far East, with an area of about . The Pacific Ocean and the Sea of Okhotsk make up the peninsula's eastern and west ...

.

* The Eleventh Air Force implemented other bombing missions against the northern Kurils, including a strike by six B-24

The Consolidated B-24 Liberator is an American heavy bomber, designed by Consolidated Aircraft of San Diego, California. It was known within the company as the Model 32, and some initial production aircraft were laid down as export models d ...

s from the 404th Bombardment Squadron

4 (four) is a number, numeral and digit. It is the natural number following 3 and preceding 5. It is the smallest semiprime and composite number, and is considered unlucky in many East Asian cultures.

In mathematics

Four is the smallest co ...

and 16 P-38

The Lockheed P-38 Lightning is an American single-seat, twin piston-engined fighter aircraft that was used during World War II. Developed for the United States Army Air Corps by the Lockheed Corporation, the P-38 incorporated a distinctive t ...

s from the 54th Fighter Squadron

The 54th Fighter Squadron is an inactive United States Air Force unit. Its last assignment was to the 3d Operations Group, being stationed at Elmendorf Air Force Base, Alaska. It was inactivated on 28 April 2000.

History World War II

Activated ...

on 5 February 1944.

* Japanese sources report that the Matsuwa military installations were subject to American air-strikes between 1943 and 1944.

* The Americans' strategic feint called "Operation Wedlock

Operation or Operations may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* ''Operation'' (game), a battery-operated board game that challenges dexterity

* Operation (music), a term used in musical set theory

* ''Operations'' (magazine), Multi-Man ...

" diverted Japanese attention north and misled them about the U.S. strategy in the Pacific. The plan included air strikes by the USAAF and U.S. Navy bombers which included U.S. Navy shore bombardment and submarine operations. The Japanese increased their garrison in the north Kurils from 8,000 in 1943 to 41,000 in 1944 and maintained more than 400 aircraft in the Kurils and Hokkaidō area in anticipation that the Americans might invade from Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S ...

.

* American planners had briefly contemplated an invasion of northern Japan from the

* American planners had briefly contemplated an invasion of northern Japan from the Aleutian Islands

The Aleutian Islands ( ; ; ale, Unangam Tanangin, "land of the Aleuts"; possibly from the Chukchi ''aliat'', or "island")—also called the Aleut Islands, Aleutic Islands, or, before 1867, the Catherine Archipelago—are a chain of 14 main, ...

during the autumn of 1943 but rejected that idea as too risky and impractical. They considered the use of Boeing B-29

The Boeing B-29 Superfortress is an American four-engined propeller-driven heavy bomber, designed by Boeing and flown primarily by the United States during World War II and the Korean War. Named in allusion to its predecessor, the B-17 Fly ...

Superfortresses, on Amchitka and Shemya bases, but rejected the idea. The U.S. military maintained interest in these plans when they ordered the expansion of bases in the western Aleutians, and major construction began on Shemya. In 1945, plans for a possible invasion of Japan via the northern route were shelved.

* Between 18 August and 31 August 1945 Soviet forces invaded the North and South Kurils.

* The Soviets expelled the entire Japanese civilian population of roughly 17,000 by 1946.

* Between 24 August and 4 September 1945 the Eleventh Air Force of the United States Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

sent two B-24s on reconnaissance missions over the North Kuril Islands with the intention of taking photos of the Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

occupation in the area. Soviet fighters intercepted and forced them away.

In February 1945 the Yalta Agreement

The Yalta Conference (codenamed Argonaut), also known as the Crimea Conference, held 4–11 February 1945, was the World War II meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union to discuss the post ...

promised to the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

South Sakhalin

Karafuto Prefecture ( ja, 樺太庁, ''Karafuto-chō''; russian: Префектура Карафуто, Prefektura Karafuto), commonly known as South Sakhalin, was a prefecture of Japan located in Sakhalin from 1907 to 1949.

Karafuto became t ...

and the Kuril islands

The Kuril Islands or Kurile Islands (; rus, Кури́льские острова́, r=Kuril'skiye ostrova, p=kʊˈrʲilʲskʲɪjə ɐstrɐˈva; Japanese: or ) are a volcanic archipelago currently administered as part of Sakhalin Oblast in the ...

in return for entering the Pacific War against the Japanese during World War II. In August 1945 the Soviet Union mounted an armed invasion of South Sakhalin

Karafuto Prefecture ( ja, 樺太庁, ''Karafuto-chō''; russian: Префектура Карафуто, Prefektura Karafuto), commonly known as South Sakhalin, was a prefecture of Japan located in Sakhalin from 1907 to 1949.

Karafuto became t ...

at the cost of over 5,000 Soviet and Japanese lives.

Russian administration

The Kuril Islands are split into three administrative districts (raion

A raion (also spelt rayon) is a type of administrative unit of several post-Soviet states. The term is used for both a type of subnational entity and a division of a city. The word is from the French (meaning 'honeycomb, department'), and is co ...

s) part of Sakhalin Oblast

Sakhalin Oblast ( rus, Сахали́нская о́бласть, r=Sakhalínskaya óblast', p=səxɐˈlʲinskəjə ˈobləsʲtʲ) is a federal subject of Russia (an oblast) comprising the island of Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands in the Rus ...

:

* Severo-Kurilsky District

Severo-Kurilsky District (russian: Се́веро-Кури́льский райо́н) is an administrative district ( raion) of Sakhalin Oblast, Russia; one of the seventeen in the oblast.Law #25-ZO Municipally, it is incorporated as Severo-Ku ...

( Severo-Kurilsk)

* Kurilsky District (Kurilsk

Kurilsk (russian: Кури́льск; ja, 紗那村 ''Shana-mura'') is a town and the administrative center of Kurilsky District of Sakhalin Oblast, Russia, located on the island of Iturup. Population:

History

Ainu have been known to inhabit ...

)

* Yuzhno-Kurilsky District (Yuzhno-Kurilsk

Yuzhno-Kurilsk (russian: Ю́жно-Кури́льск; ja, 留夜別, ''Ruyobetsu'') is an urban locality (an urban-type settlement) and the administrative center of Yuzhno-Kurilsky District of Sakhalin Oblast, Russia. Population: It is ...

)

Japan maintains a claim to the four southernmost islands of Kunashir

, other_names = kz, Kün Ashyr; ja, 国後島

, location = Sea of Okhotsk

, locator_map = File:Kurily Kunashir.svg

, coordinates =

, archipelago = Kuril Islands

, total_islands =

, major_islands =

, area =

, length =

, width = fr ...

, Iturup

, other_names = russian: Итуру́п; ja, 択捉島

, location = Sea of Okhotsk

, coordinates =

, archipelago = Kuril Islands

, total_islands =

, major_islands =

, area_km2 = 3139

, length_km = 200

, width_km = 27

, coastline =

, highest_moun ...

, Shikotan

; ja, 色丹島

, location = Pacific Ocean

, coordinates =

, archipelago = Kuril Islands

, total_islands = 1

, major_islands =

, area_km2 = 225

, length =

, width =

, coastline ...

, and the Habomai

; ja, 歯舞群島, Habomai guntō

, location = Pacific Ocean

, coordinates =

, archipelago = Kuril Islands

, total_islands = 10 + several rocks

, major_islands =

, area_km2 = 100

, length =

, ...

rocks, together called the ''Northern Territories''.

In addition, the Japanese government claims that the Kuril Islands other than the Northern Territories and South Karafuto, are undetermined areas under international law because the San Francisco Peace Treaty does not specify where they belong and the Soviet Union has not signed it.

On 8 February 2017 the Russian government gave names to five previously unnamed Kuril islands in Sakhalin Oblast

Sakhalin Oblast ( rus, Сахали́нская о́бласть, r=Sakhalínskaya óblast', p=səxɐˈlʲinskəjə ˈobləsʲtʲ) is a federal subject of Russia (an oblast) comprising the island of Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands in the Rus ...

: Derevyanko Island (after Kuzma Derevyanko, ), Gnechko Island (after Alexey Gnechko, ), Gromyko Island (after Andrei Gromyko

Andrei Andreyevich Gromyko (russian: Андрей Андреевич Громыко; be, Андрэй Андрэевіч Грамыка; – 2 July 1989) was a Soviet communist politician and diplomat during the Cold War. He served a ...

, ), Farkhutdinov Island (after Igor Farkhutdinov, ) and Shchetinina Island (after Anna Shchetinina, ).

Demographics

, 19,434 people inhabited the Kuril Islands, of which over 16,700 live on the four disputed islands. These include ethnic

, 19,434 people inhabited the Kuril Islands, of which over 16,700 live on the four disputed islands. These include ethnic Russians

, native_name_lang = ru

, image =

, caption =

, population =

, popplace =

118 million Russians in the Russian Federation (2002 ''Winkler Prins'' estimate)

, region1 =

, pop1 ...

, Ukrainians

Ukrainians ( uk, Українці, Ukraintsi, ) are an East Slavic ethnic group native to Ukraine. They are the seventh-largest nation in Europe. The native language of the Ukrainians is Ukrainian. The majority of Ukrainians are Eastern Or ...

, Belarusians

, native_name_lang = be

, pop = 9.5–10 million

, image =

, caption =

, popplace = 7.99 million

, region1 =

, pop1 = 600,000–768,000

, region2 =

, pop2 ...

, Tatars

The Tatars ()Tatar

in the Collins English Dictionary is an umbrella term for different , Nivkhs, Oroch, and Ainus.

While in Russian sources the islands are mentioned for the first time in 1646, the earliest detailed information about them was provided by the explorer

While in Russian sources the islands are mentioned for the first time in 1646, the earliest detailed information about them was provided by the explorer

names ! scope="col" , Island Group ! scope="col" , Administrative centre /

! scope="col" , Other settlements ! scope="col" data-sort-type="number" , Area ! scope="col" , , - ,

, Harimukotan, Harumukotan , North Kurils , Sunazhma , Severgin Bay , style="text-align: right;" , , style="text-align: right;" , 0 , - , Ekarma , Экарма , , Ekaruma , North Kurils , Kruglyy , , style="text-align: right;" , , style="text-align: right;" , 0 , - , Chirinkotan , Чиринкотан , , , North Kurils , Cape Ptichy , , style="text-align: right;" , , style="text-align: right;" , 0 , - ,

Southern Kuriles / Northern Territories: A Stumbling-block in Russia-Japan Relationship

history and analysis by Andrew Andersen, Department of Political Science, University of Victoria, May 2001 * http://depts.washington.edu/ikip/index.shtml (Kuril Island Biocomplexity Project) * (includes space imagery)

a

Natural Heritage Protection Fund

* http://www.mofa.go.jp/region/europe/russia/territory/index.html

Chishima: Frontiers of San Francisco Treaty in Hokkaido

Short film on the disputed islands from a Japanese perspective

USGS Map showing location of Magnitude 8.3 Earthquake 46.616°N, 153.224°E Kuril Islands region, November 15, 2006 11:14:16 UTC

Pictures of Kuril Islands

Kuril Islands

at

in the Collins English Dictionary is an umbrella term for different , Nivkhs, Oroch, and Ainus.

Russian Orthodox Christianity

Russian Orthodoxy (russian: Русское православие) is the body of several churches within the larger communion of Eastern Orthodox Christianity, whose liturgy is or was traditionally conducted in Church Slavonic language. Most ...

is the main religion. Some of the villages are permanently manned by Russian soldiers (especially in Kunashir

, other_names = kz, Kün Ashyr; ja, 国後島

, location = Sea of Okhotsk

, locator_map = File:Kurily Kunashir.svg

, coordinates =

, archipelago = Kuril Islands

, total_islands =

, major_islands =

, area =

, length =

, width = fr ...

following recent tensions). Others are inhabited by civilians, which are mostly fishers, workers in fish factories, dockers, and social sphere workers (police, medics, teachers, etc.). Recent construction works on the islands attracts a lot of migrant workers from the rest of Russia and other post-Soviet states

The post-Soviet states, also known as the former Soviet Union (FSU), the former Soviet Republics and in Russia as the near abroad (russian: links=no, ближнее зарубежье, blizhneye zarubezhye), are the 15 sovereign states that wer ...

. , there were only 8 inhabited islands out of a total of 56. Iturup Island

, other_names = russian: Итуру́п; ja, 択捉島

, location = Sea of Okhotsk

, coordinates =

, archipelago = Kuril Islands

, total_islands =

, major_islands =

, area_km2 = 3139

, length_km = 200

, width_km = 27

, coastline =

, highest_moun ...

is over 60% ethnically Ukrainian.

Economy

Fishing

Fishing is the activity of trying to catch fish. Fish are often caught as wildlife from the natural environment, but may also be caught from stocked bodies of water such as ponds, canals, park wetlands and reservoirs. Fishing techniques ...

is the primary occupation. The islands have strategic and economic value, in terms of fisheries and also mineral deposits of pyrite

The mineral pyrite (), or iron pyrite, also known as fool's gold, is an iron sulfide with the chemical formula Fe S2 (iron (II) disulfide). Pyrite is the most abundant sulfide mineral.

Pyrite's metallic luster and pale brass-yellow hue giv ...

, sulfur

Sulfur (or sulphur in British English) is a chemical element with the symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms form cyclic octatomic molecules with a chemical formul ...

, and various polymetallic ores. There are hopes that oil exploration will provide an economic boost to the islands.

In 2014, construction workers built a pier and a breakwater in Kitovy Bay, central Iturup, where barges are a major means of transport, sailing between the cove and ships anchored offshore. A new road has been carved through the woods near Kurilsk, the island's biggest village, going to the site of Yuzhno-Kurilsk Mendeleyevo Airport.

Gidrostroy, the Kurils' biggest business group with interests in fishing, construction and real estate, built its second fish processing factory on Iturup island in 2006, introducing a state-of-the-art conveyor system.

To deal with a rise in the demand of electricity, the local government is also upgrading a state-run geothermal power plant at Mount Baransky, an active volcano, where steam and hot water can be found.

Military

The main Russian force stationed on the islands is the 18th Machine Gun Artillery Division, which has its headquarters in Goryachiye Klyuchi onIturup Island

, other_names = russian: Итуру́п; ja, 択捉島

, location = Sea of Okhotsk

, coordinates =

, archipelago = Kuril Islands

, total_islands =

, major_islands =

, area_km2 = 3139

, length_km = 200

, width_km = 27

, coastline =

, highest_moun ...

. There are also Border Guard Service troops stationed on the islands. In February 2011, Russian President Dmitry Medvedev called for substantial reinforcements of the Kuril Islands defences. Subsequently, in 2015, additional anti-aircraft missile systems Tor and Buk

Buk or BUK may refer to:

Places Czech Republic

* Buk (Prachatice District), a municipality and village in the South Bohemian Region

* Buk (Přerov District), a municipality and village in the Olomouc Region

*Buk, a village and part of Jindřichů ...

, coastal defence missile system Bastion, Kamov Ka-52

The Kamov Ka-50 "Black Shark" (russian: Чёрная акула, translit=Chyornaya akula, English: kitefin shark, NATO reporting name: Hokum A) is a Soviet/Russian single-seat attack helicopter with the distinctive coaxial rotor system of ...

combat helicopters and one ''Varshavyanka'' project submarine came on defence of Kuril Islands. During the 2022 Russian Invasion of Ukraine it was reported that parts of the 18th Machine Gun Artillery Division were redeployed to Eastern Ukraine.

List of main islands

While in Russian sources the islands are mentioned for the first time in 1646, the earliest detailed information about them was provided by the explorer

While in Russian sources the islands are mentioned for the first time in 1646, the earliest detailed information about them was provided by the explorer Vladimir Atlasov

Vladimir Vasilyevich Atlasov or Otlasov ( or Отла́сов; between 1661 and 1664 – 1711) was a Siberian Cossack who was the first Russian to organize systematic exploration of the Kamchatka Peninsula. Atlasov Island, an uninhabited volcani ...

in 1697. In the 18th and early 19th centuries, the Kuril Islands were explored by Danila Antsiferov, I. Kozyrevsky, Ivan Yevreinov, Fyodor Luzhin, Martin Shpanberg

__NOTOC__

Martin Spanberg (d. 1761; russian: Мартын Петрович Шпанберг, ''Martyn Petrovich Shpanberg'') was a Danish naval officer in Russian service who took part with his compatriot Vitus Bering in both Kamchatka expedition ...

, Adam Johann von Krusenstern

Adam Johann von Krusenstern (also Krusenstjerna in Swedish; russian: Ива́н Фёдорович Крузенште́рн, tr. ; 10 October 177012 August 1846) was a Russian admiral and explorer, who led the first Russian circumnavigation ...

, Vasily Golovnin

Vasily Mikhailovich Golovnin ( Russian: Василий Михайлович Головнин; , Gulyniki, Ryazan Oblast – , Saint Petersburg) was a Russian navigator, Vice Admiral, and corresponding member of the Russian Academy of Sciences ...

, and Henry James Snow.

The following table lists information on the main islands from north to south:

}

! scope="col" , ja, Name

! scope="col" , Alternativenames ! scope="col" , Island Group ! scope="col" , Administrative centre /

! scope="col" , Other settlements ! scope="col" data-sort-type="number" , Area ! scope="col" , , - ,

Severo-Kurilsky District

Severo-Kurilsky District (russian: Се́веро-Кури́льский райо́н) is an administrative district ( raion) of Sakhalin Oblast, Russia; one of the seventeen in the oblast.Law #25-ZO Municipally, it is incorporated as Severo-Ku ...

,

,

, North Kurils

, North Kurils (Kita-chishima / 北千島)

, Severo-Kurilsk

, Shelikovo, Podgorny, Baikovo

, style="text-align: right;" ,

, style="text-align: right;" , 2,560

, -

, Shumshu

, Шумшу

,

, Shumushu

, North Kurils

, Baikovo

,

, style="text-align: right;" ,

, style="text-align: right;" , 20

, -

, Atlasov

, Атласова

,

, Oyakoba, Araido

, North Kurils

, Alaidskaya Bay

,

, style="text-align: right;" ,

, style="text-align: right;" , 0

, -

, Paramushir

russian: Парамушир ja, 幌筵島

, native_name_link =

, nickname =

, location = Pacific Ocean

, coordinates =

, archipelago = Kuril Island

, total_islands =

, major_islands =

, area_km2 = 2053

, length_km = 100

, width_km = 20

, ...

, Парамушир

,

, Paramushiru, Horomushiro

, North Kurils

, Severo-Kurilsk

, Shelikovo, Podgorny

, style="text-align: right;" ,

, style="text-align: right;" , 2,540

, -

, Antsiferov Antsiferov (feminine form: Antsiferova) is a Russian-language surname derived from the archaic Russian first name "Antsifer" (Анцифер), in turn derived from "Onisifor" (Онисифор, Onesiphorus).

People with the name include:

* Alexei ...

, Анциферова

,

, Shirinki

, North Kurils

, Antsiferov beach

, Cape Terkut

, style="text-align: right;" ,

, style="text-align: right;" , 0

, -

, Makanrushi

, Маканруши

,

, Makanru

, North Kurils

, Zakat

,

, style="text-align: right;" ,

, style="text-align: right;" , 0

, -

, Avos'

, Авось

,

, Hokake, Hainoko

, North Kurils

,

,

, style="text-align: right;" ,

, style="text-align: right;" , 0

, -

, Onekotan

, Онекотан

,

, Onwakotan

, North Kurils

, Mussel

, Kuroisi, Nemo, Shestakov

, style="text-align: right;" ,

, style="text-align: right;" , 0

, -

, Kharimkotan

Kharimkotan (russian: Харимкотан); Japanese 春牟古丹島; Harimukotan-tō, alternatively Harumukotan-tō or 加林古丹島; Karinkotan-tō) is an uninhabited volcanic island located from Onekotan near the northern end of the K ...

, Харимкотан

, , Harimukotan, Harumukotan , North Kurils , Sunazhma , Severgin Bay , style="text-align: right;" , , style="text-align: right;" , 0 , - , Ekarma , Экарма , , Ekaruma , North Kurils , Kruglyy , , style="text-align: right;" , , style="text-align: right;" , 0 , - , Chirinkotan , Чиринкотан , , , North Kurils , Cape Ptichy , , style="text-align: right;" , , style="text-align: right;" , 0 , - ,

Shiashkotan

Shiashkotan (russian: Шиашкотан); ( ja, 捨子古丹島; Shasukotan-tō) is an uninhabited volcanic island near the center of the Kuril Islands chain in the Sea of Okhotsk in the northwest Pacific Ocean, separated from Ekarma by the Ek ...

, Шиашкотан

,

, Shasukotan

, North Kurils

, Makarovka

,

, style="text-align: right;" ,

, style="text-align: right;" , 0

, -

, Lowuschki-Felsen

, Ловушки

,

, Mushiru

, North Kurils

,

,

, style="text-align: right;" ,

, style="text-align: right;" , 0

, -

, Raikoke

Raikoke (russian: Райкоке, ja, 雷公計島), also spelled Raykoke, is, as of 2019 a Russian uninhabited volcanic island near the centre of the Kuril Islands chain in the Sea of Okhotsk in the northwest Pacific Ocean, distant from the is ...

, Райкоке

,

,

, North Kurils

, Raikoke

,

, style="text-align: right;" ,

, style="text-align: right;" , 0

, -

, Matua

, Матуа

,

, Matsuwa

, North Kurils

, Sarychevo

,

, style="text-align: right;" ,

, style="text-align: right;" , 0

, -

, Rasshua

, Расшуа

,

, Rashowa, Rasutsua

, North Kurils

, Arches Point

,

, style="text-align: right;" ,

, style="text-align: right;" , 0

, -

, Srednego

, Среднего

,

, Suride

, North Kurils

,

,

,

, style="text-align: right;" , 0

, -

, Ushishir

, Ушишир

,

, Ushishiru

, North Kurils

, Kraternya

, Ryponkicha

, style="text-align: right;" ,

, style="text-align: right;" , 0

, -

, Ketoy

Ketoy (or ''Ketoi'') (russian: Кетой; Japanese 計吐夷島; Ketoi-tō) is an uninhabited volcanic island located in the centre of the Kuril Islands chain in the Sea of Okhotsk in the northwest Pacific Ocean. Its name is derived from the Ainu ...

, Кетой

,

, Ketoi

, North Kurils

, Storozheva

,

, style="text-align: right;" ,

, style="text-align: right;" , 0

, -

, Kurilsky District

,

,

, Middle Kurils (Naka-chishima / 中千島)

, split between both Japanese groups

, Kurilsk

Kurilsk (russian: Кури́льск; ja, 紗那村 ''Shana-mura'') is a town and the administrative center of Kurilsky District of Sakhalin Oblast, Russia, located on the island of Iturup. Population:

History

Ainu have been known to inhabit ...

, Reidovo, Kitovyi, Rybaki, Goryachiye Klyuchi, Kasatka, Burevestnik, Shumi-Gorodok, Gornyy

, style="text-align: right;" ,

, style="text-align: right;" , 6,606

, -

, Simushir

Simushir (russian: Симушир, ja, 新知島, translit=Shimushiru-tō, ain, シムシㇼ, translit=Simusir), meaning ''Large Island'' in Ainu, is an uninhabited volcanic island near the center of the Kuril Islands chain in the Sea of Okhots ...

, Симушир

,

, Shimushiru, Shinshiru

, North Kurils

, Kraternyy

, Srednaya bay

, style="text-align: right;" ,

, style="text-align: right;" , 0

, -

, Broutona

, Броутона

,

, Buroton, Makanruru

, North Kurils

, Nedostupnyy

,

, style="text-align: right;" ,

, style="text-align: right;" , 0

, -

, Chirpoy

, Чирпой

,

, Chirihoi, Chierupoi

, North Kurils

, Peschanaya Bay

,

, style="text-align: right;" ,

, style="text-align: right;" , 0

, -

, Brat Chirpoyev

, Брат Чирпоев

,

, Chirihoinan

, North Kurils

, Garovnikova

, Semenova

, style="text-align: right;" ,

, style="text-align: right;" , 0

, -

, Urup

, Уруп

,

, Uruppu

, North Kurils

, Mys Kastrikum

, Mys Van-der-Lind

, style="text-align: right;" ,

, style="text-align: right;" , 0

, -

, Other

,

,

,

, North Kurils

,

,

, style="text-align: right;" ,

, style="text-align: right;" , 0

, -

, Iturup

, other_names = russian: Итуру́п; ja, 択捉島

, location = Sea of Okhotsk

, coordinates =

, archipelago = Kuril Islands

, total_islands =

, major_islands =

, area_km2 = 3139

, length_km = 200

, width_km = 27

, coastline =

, highest_moun ...

, Итуруп

,

, Etorofu, Ietorupu

, South Kurils (Minami-chishima / 南千島)

, Kurilsk

Kurilsk (russian: Кури́льск; ja, 紗那村 ''Shana-mura'') is a town and the administrative center of Kurilsky District of Sakhalin Oblast, Russia, located on the island of Iturup. Population:

History

Ainu have been known to inhabit ...

, Reidovo, Kitovyi, Rybaki, Goryachiye Klyuchi, Kasatka, Burevestnik, Shumi-Gorodok, Gornyy

, style="text-align: right;" ,

, style="text-align: right;" , 6,602

, -

, Yuzhno-Kurilsky District

,

,

, South Kurils

, South Kurils

, Yuzhno-Kurilsk

Yuzhno-Kurilsk (russian: Ю́жно-Кури́льск; ja, 留夜別, ''Ruyobetsu'') is an urban locality (an urban-type settlement) and the administrative center of Yuzhno-Kurilsky District of Sakhalin Oblast, Russia. Population: It is ...

, Malokurilskoye, Rudnaya, Lagunnoye, Otrada

Otrada (russian: links=no, Отрада) is a rural locality (a selo) in Kipchak-Askarovsky Selsoviet, Alsheyevsky District, Bashkortostan, Russia. The population was 208 as of 2010. There are 3 streets.

Geography

Otrada is located 30 km sou ...

, Goryachiy Plyazh, Aliger

''Aliger'' is a genus of sea snails, marine gastropod mollusks in the family Strombidae, the true conchs.

''Aliger'' was previously a synonym of '' Lobatus'' Swainson, 1837

Species

Species within the genus ''Aliger'' include:

* †''Aliger dom ...

, Mendeleyevo Mendeleyevo (russian: Менделе́ево) is the name of several inhabited localities in Russia.

Urban localities

*Mendeleyevo, Moscow Oblast, a work settlement in Solnechnogorsky District of Moscow Oblast

Rural localities

* Mendeleyevo, Kal ...

, Dubovoye, Polino, Golovnino

, style="text-align: right;" ,

, style="text-align: right;" , 10,268

, -

, Kunashir

, other_names = kz, Kün Ashyr; ja, 国後島

, location = Sea of Okhotsk

, locator_map = File:Kurily Kunashir.svg

, coordinates =

, archipelago = Kuril Islands

, total_islands =

, major_islands =

, area =

, length =

, width = fr ...

, Кунашир

,

, Kunashiri

, South Kurils

, Yuzhno-Kurilsk

Yuzhno-Kurilsk (russian: Ю́жно-Кури́льск; ja, 留夜別, ''Ruyobetsu'') is an urban locality (an urban-type settlement) and the administrative center of Yuzhno-Kurilsky District of Sakhalin Oblast, Russia. Population: It is ...

, Rudnaya, Lagunnoye, Otrada

Otrada (russian: links=no, Отрада) is a rural locality (a selo) in Kipchak-Askarovsky Selsoviet, Alsheyevsky District, Bashkortostan, Russia. The population was 208 as of 2010. There are 3 streets.

Geography

Otrada is located 30 km sou ...

, Goryachiy Plyazh, Aliger

''Aliger'' is a genus of sea snails, marine gastropod mollusks in the family Strombidae, the true conchs.

''Aliger'' was previously a synonym of '' Lobatus'' Swainson, 1837

Species

Species within the genus ''Aliger'' include:

* †''Aliger dom ...

, Mendeleyevo Mendeleyevo (russian: Менделе́ево) is the name of several inhabited localities in Russia.

Urban localities

*Mendeleyevo, Moscow Oblast, a work settlement in Solnechnogorsky District of Moscow Oblast

Rural localities

* Mendeleyevo, Kal ...

, Dubovoye, Polino, Golovnino

, style="text-align: right;" ,

, style="text-align: right;" , 7,800

, -

, Shikotan

; ja, 色丹島

, location = Pacific Ocean

, coordinates =

, archipelago = Kuril Islands

, total_islands = 1

, major_islands =

, area_km2 = 225

, length =

, width =

, coastline ...

Group

, Шикотан

,

,

, South Kurils

, Malokurilskoye

, Dumnova, Otradnaya, Krabozavodskoye

Krabozavodskoye (russian: Крабозаводское), also known as Anama ( ja, 穴澗; Anama), is a village ('' selo'') in Yuzhno-Kurilsky District of Sakhalin Oblast, Russia.

References

{{Authority control

Rural localities in Sakhalin ...

(formerly Anama), Zvezdnaya

Zvyozdnaya (russian: Звёздная) is a station on the Moskovsko-Petrogradskaya Line of the Saint Petersburg Metro. It was opened on December 25, 1972. It was designed by K.N. Afonskya, A.C. Getskin and V.P. Shuvalova. In the original bluepri ...

, Voloshina Voloshin, Woloshin,Wolloshin, Voloshyn or Woloshyn (Cyrillic: Волошин) is a Ukrainian and Russian masculine surname. It comes from the dated exonym Volokh ("Vlach", "Romanian"). Its feminine forms are Voloshina, Woloshina, Voloshyna or Wolosh ...

, Kray Sveta

, style="text-align: right;" ,

, style="text-align: right;" , 2,440

, -

, Shikotan

; ja, 色丹島

, location = Pacific Ocean

, coordinates =

, archipelago = Kuril Islands

, total_islands = 1

, major_islands =

, area_km2 = 225

, length =

, width =

, coastline ...

Island

, Шикотан

,

,

, South Kurils

, Malokurilskoye

, Dumnova, Otradnaya, Krabozavodskoye

Krabozavodskoye (russian: Крабозаводское), also known as Anama ( ja, 穴澗; Anama), is a village ('' selo'') in Yuzhno-Kurilsky District of Sakhalin Oblast, Russia.

References

{{Authority control

Rural localities in Sakhalin ...

(formerly Anama), Zvezdnaya

Zvyozdnaya (russian: Звёздная) is a station on the Moskovsko-Petrogradskaya Line of the Saint Petersburg Metro. It was opened on December 25, 1972. It was designed by K.N. Afonskya, A.C. Getskin and V.P. Shuvalova. In the original bluepri ...

, Voloshina Voloshin, Woloshin,Wolloshin, Voloshyn or Woloshyn (Cyrillic: Волошин) is a Ukrainian and Russian masculine surname. It comes from the dated exonym Volokh ("Vlach", "Romanian"). Its feminine forms are Voloshina, Woloshina, Voloshyna or Wolosh ...

, Kray Sveta

, style="text-align: right;" ,

, style="text-align: right;" , 2,440

, -

, Other

,

,

,

, South Kurils

,

, Ayvazovskovo

, style="text-align: right;" ,

, style="text-align: right;" , 0

, -

, Khabomai

, Хабомаи

,

, Habomai

, South Kurils

, Zorkiy

, Zelyony, Polonskogo

, style="text-align: right;" ,

, style="text-align: right;" , 28

, -

, Polonskogo

, Полонского

,

, Taraku

, South Kurils

, Moriakov Bay station

,

, style="text-align: right;" ,

, style="text-align: right;" , 2

, -

, Oskolki

, Осколки

,

, Todo, Kaiba

, South Kurils

,

,

,

, style="text-align: right;" , 0

, -

, Zelyony

, Зелёный

,

, Shibotsu

, South Kurils

, Glushnevskyi station

,

, style="text-align: right;" ,

, style="text-align: right;" , 3

, -

, Kharkar

, Харкар

,

, Harukaru, Dyomina

, South Kurils

, Haruka

,

, style="text-align: right;" ,

, style="text-align: right;" , 0

, -

, Yuri

, Юрий

,

, Yuri

, South Kurils

, Kalernaya

,

, style="text-align: right;" ,

, style="text-align: right;" , 0

, -

, Anuchina

, Анучина

,

, Akiyuri

, South Kurils

, Bolshoye Bay

,

, style="text-align: right;" ,

, style="text-align: right;" , 0

, -

, Tanfil'yev

, Танфильев

,

, Suishō

, South Kurils

, Zorkiy

, Tanfilyevka Bay, Bolotnoye

, style="text-align: right;" ,

, style="text-align: right;" , 23

, -

, Storozhevoy

''Storozhevoy'' (russian: link=no, italic=yes, Сторожевой, "guardian" or "sentry") was a Soviet Navy Project 1135 Burevestnik-class anti-submarine frigate (NATO reporting name Krivak I). The ship initially was attached to the Sovie ...

, Сторожевой

,

, Moemoshiri

, South Kurils

,

,

, style="text-align: right;" ,

, style="text-align: right;" , 0

, -

, Rifovyy

, Рифовый

, オドケ島

, Odoke

, South Kurils

,

,

,

, style="text-align: right;" , 0

, -

, Signal'nyy

, Сигнальный

,

, Kaigara

, South Kurils

,

,

, style="text-align: right;" ,

, style="text-align: right;" , 0

, -

, Other

,

,

,

, South Kurils

,

, Opasnaga, Udivitelnaya

, style="text-align: right;" ,

, style="text-align: right;" , 0

, - class="sortbottom"

! colspan="7" style="text-align: right;" scope="row" , Total:

! style="text-align: right;" ,

! style="text-align: right;" , 19,434

See also

*2006 Kuril Islands earthquake

The 2006 Kuril Islands earthquake occurred on November 15 at with a magnitude of 8.3 and a maximum Mercalli intensity of VII (''Very Strong'') and a maximum Shindo intensity of JMA 2. This megathrust earthquake was the largest event in the cen ...

* 2007 Kuril Islands earthquake

The 2007 Kuril Islands earthquake occurred east of the Kuril Islands on 13 January at . The shock had a moment magnitude of 8.1 and a maximum Mercalli intensity of VI (''Strong''). A non-destructive tsunami was generated, with maximum wave am ...

* Chishima Province

was a province of Japan created during the Meiji Era. It originally contained the Kuril Islands from Kunashiri northwards, and later incorporated Shikotan as well. Its original territory is currently occupied by Russia, and its territory was ren ...

* Evacuation of Karafuto and Kuriles

* Invasion of the Kuril Islands

The Invasion of the Kuril Islands (russian: Курильская десантная операция, lit=Kuril Islands Landing Operation) was the World War II Soviet military operation to capture the Kuril Islands from Japan in 1945. The i ...

* Karafuto Fortress

* Karafuto Prefecture