Kingdom Of Hawai'i on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Hawaiian Kingdom, also known as the Kingdom of Hawai╩╗i ( Hawaiian: ╔Ť ╔Éw╦łpuni h╔Ö╦łv╔Éj╩öi, was an archipelagic country from 1795 to 1893, which eventually encompassed all of the inhabited

Like his predecessor, Lunalilo failed to name an heir to the throne. Once again, the legislature of the Hawaiian Kingdom held an election to fill the vacancy. Queen Emma, widow of Kamehameha IV, was nominated along with David Kal─ükaua. The 1874 election was a nasty campaign in which both candidates resorted to mudslinging and innuendo. Kal─ükaua became the second elected King of Hawai╩╗i but without the ceremonial popular vote of Lunalilo. The choice was controversial, and U.S. and British troops were called upon to suppress rioting by Queen Emma's supporters, the '' Emmaites''.

Kal─ükaua officially proclaimed that his sister, Lili╩╗uokalani, would succeed to the throne upon his death. Hoping to avoid uncertainty, Kal─ükaua listed a line of succession in his will, so that after Lili╩╗uokalani the throne should succeed to Princess Victoria Ka╩╗iulani, then to Queen Consort

Like his predecessor, Lunalilo failed to name an heir to the throne. Once again, the legislature of the Hawaiian Kingdom held an election to fill the vacancy. Queen Emma, widow of Kamehameha IV, was nominated along with David Kal─ükaua. The 1874 election was a nasty campaign in which both candidates resorted to mudslinging and innuendo. Kal─ükaua became the second elected King of Hawai╩╗i but without the ceremonial popular vote of Lunalilo. The choice was controversial, and U.S. and British troops were called upon to suppress rioting by Queen Emma's supporters, the '' Emmaites''.

Kal─ükaua officially proclaimed that his sister, Lili╩╗uokalani, would succeed to the throne upon his death. Hoping to avoid uncertainty, Kal─ükaua listed a line of succession in his will, so that after Lili╩╗uokalani the throne should succeed to Princess Victoria Ka╩╗iulani, then to Queen Consort

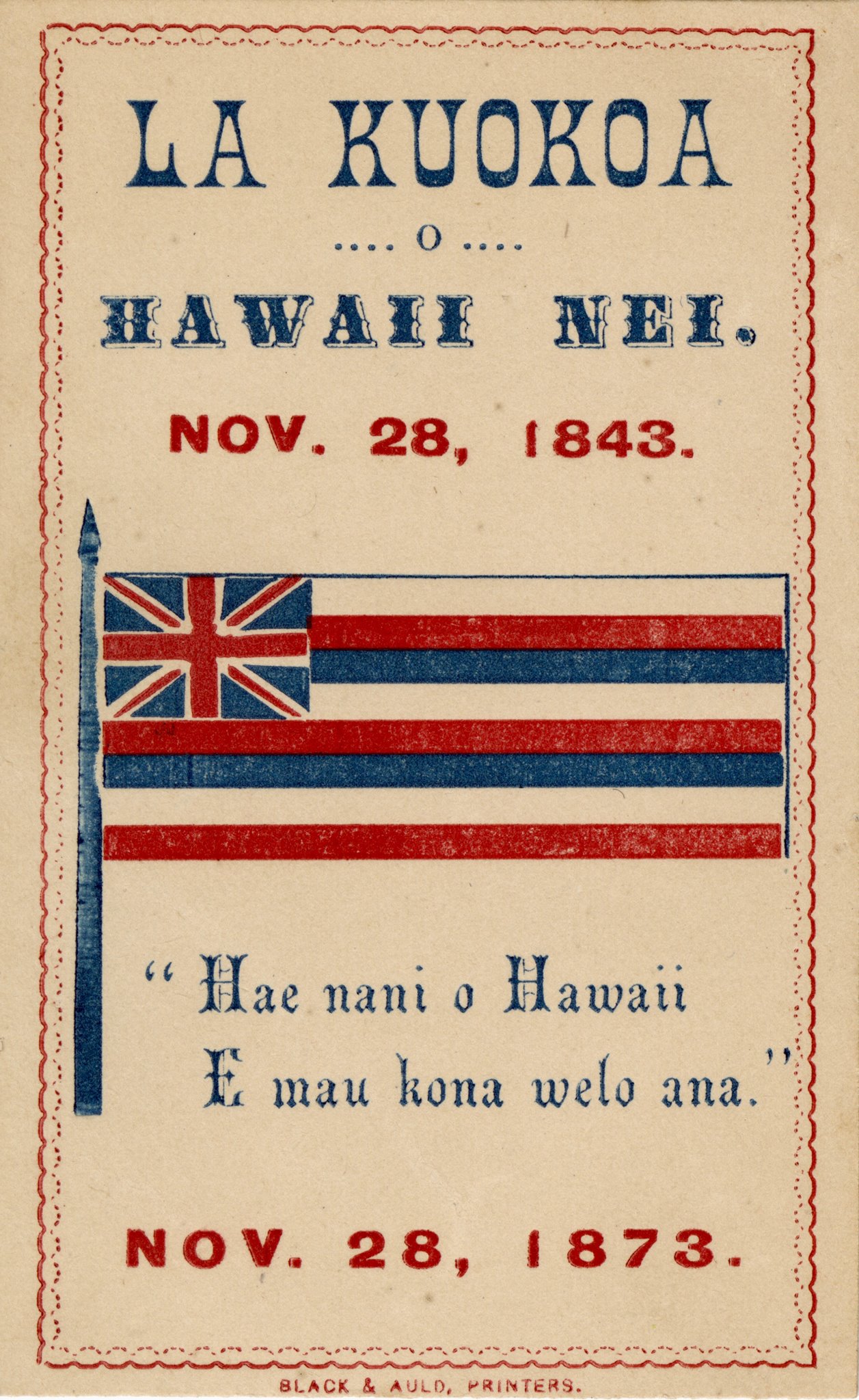

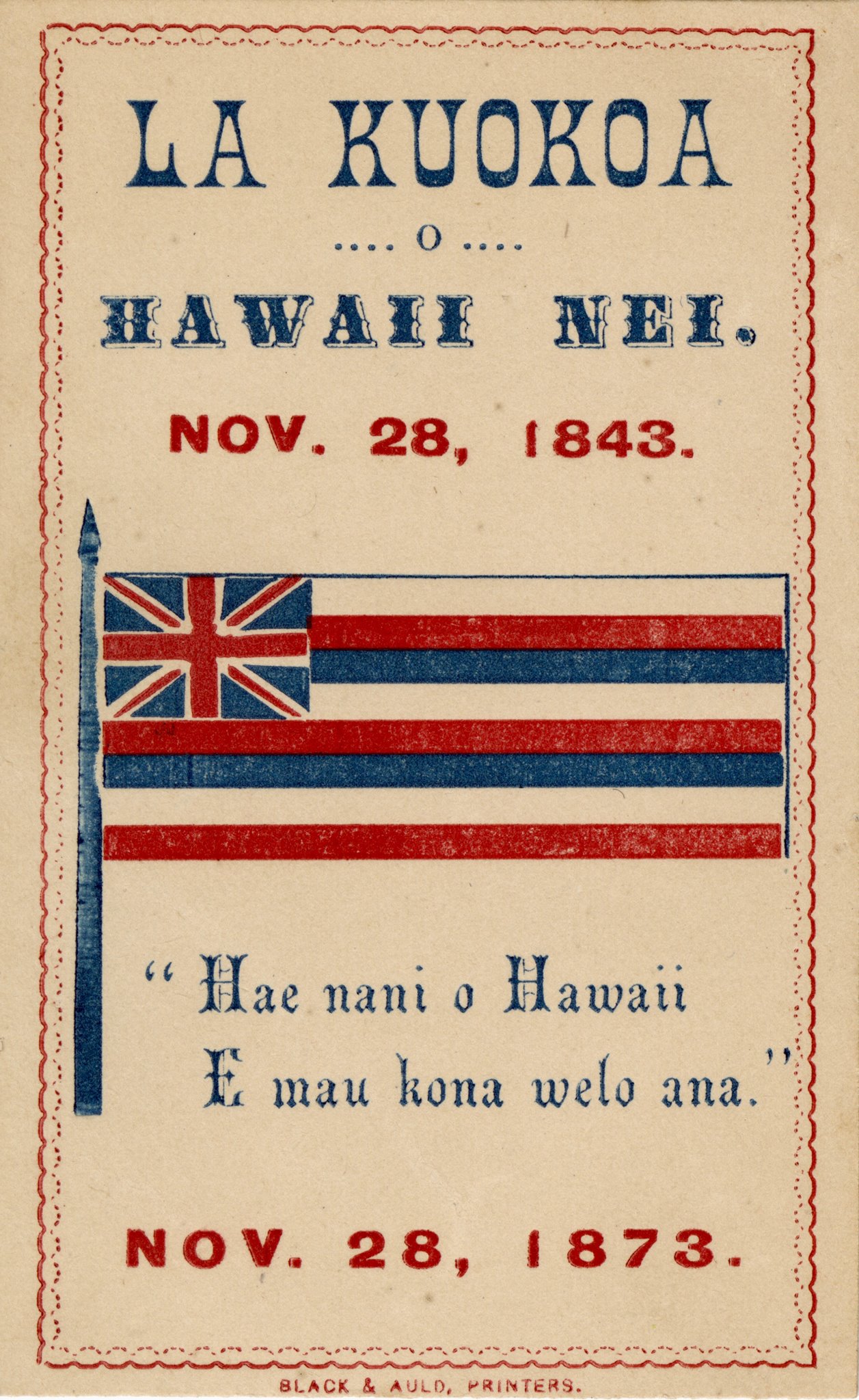

On November 28, 1843, at the Court of London, the British and French governments formally recognized Hawaiian independence. The "Anglo-Franco Proclamation", a joint declaration by France and Britain, signed by King Louis-Philippe and Queen Victoria, assured the Hawaiian delegation:

On November 28, 1843, at the Court of London, the British and French governments formally recognized Hawaiian independence. The "Anglo-Franco Proclamation", a joint declaration by France and Britain, signed by King Louis-Philippe and Queen Victoria, assured the Hawaiian delegation:

Kingdom of Hawaii

at DCStamps {{DEFAULTSORT:Hawaiian Kingdom Pre-statehood history of Hawaii Former countries of the United States Former monarchies of Oceania States and territories established in 1795 States and territories disestablished in 1893 Former kingdoms Christian states Island countries 1795 establishments in Hawaii 1893 disestablishments in Hawaii Kingdom Former regions and territories of the United States Former monarchies

Hawaiian Islands

The Hawaiian Islands () are an archipelago of eight major volcanic islands, several atolls, and numerous smaller islets in the Pacific Ocean, North Pacific Ocean, extending some from the Hawaii (island), island of Hawaii in the south to nort ...

. It was established in 1795 when Kamehameha I

Kamehameha I (; Kalani Pai╩╗ea Wohi o Kaleikini Keali╩╗ikui Kamehameha o ╩╗Iolani i Kaiwikapu kau╩╗i Ka Liholiho K┼źnui─ükea; to May 8 or 14, 1819), also known as Kamehameha the Great, was the conqueror and first ruler of the Kingdom of Hawaii ...

, then Ali╩╗i nui of Hawaii, conquered the islands of O╩╗ahu, Maui

Maui (; Hawaiian language, Hawaiian: ) is the second largest island in the Hawaiian archipelago, at 727.2 square miles (1,883 km2). It is the List of islands of the United States by area, 17th-largest in the United States. Maui is one of ...

, Moloka╩╗i, and L─üna╩╗i

L─ünai is the sixth-largest of the Hawaiian Islands and the smallest publicly accessible inhabited island in the chain. It is colloquially known as the Pineapple Island because of its past as an island-wide pineapple plantation. The island's o ...

, and unified them under one government. In 1810, the Hawaiian Islands were fully unified when the islands of Kaua╩╗i

Kauai (), anglicized as Kauai ( or ), is one of the main Hawaiian Islands.

It has an area of 562.3 square miles (1,456.4 km2), making it the fourth-largest of the islands and the 21st-largest island in the United States. Kauai lies 73 mi ...

and Ni╩╗ihau

Niihau (Hawaiian language, Hawaiian: ), anglicized as Niihau ( ), is the seventh largest island in Hawaii and the westernmost of the main islands. It is southwest of Kauai, Kauai across the Channels of the Hawaiian Islands#Kaulakahi Channel, Ka ...

voluntarily joined the Hawaiian Kingdom. Two major dynastic families ruled the kingdom, the House of Kamehameha

The House of Kamehameha ''(Hale O Kamehameha)'', or the Kamehameha dynasty, was the reigning royal family of the Hawaiian Kingdom, Kingdom of Hawaii, beginning with its founding by Kamehameha I in 1795 and ending with the death of Kamehameha V in ...

and the House of Kal─ükaua

The House of Kal─ükaua, or Kal─ükaua Dynasty, also known as the Keawe-a-Heulu line, was the reigning family of the Hawaiian Kingdom, Kingdom of Hawai╩╗i under Kal─ükaua, King Kal─ükaua and Lili╩╗uokalani, Queen Lili╩╗uokalani. They assumed power ...

.

The kingdom subsequently gained diplomatic recognition from European powers and the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

. An influx of European and American explorers, traders, and whalers soon began arriving to the kingdom, introducing diseases such as syphilis

Syphilis () is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium ''Treponema pallidum'' subspecies ''pallidum''. The signs and symptoms depend on the stage it presents: primary, secondary, latent syphilis, latent or tertiary. The prim ...

, tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

, smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by Variola virus (often called Smallpox virus), which belongs to the genus '' Orthopoxvirus''. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (W ...

, and measles

Measles (probably from Middle Dutch or Middle High German ''masel(e)'', meaning "blemish, blood blister") is a highly contagious, Vaccine-preventable diseases, vaccine-preventable infectious disease caused by Measles morbillivirus, measles v ...

, leading to the rapid decline of the Native Hawaiian population. In 1887, King Kal─ükaua

Kal─ükaua (David La╩╗amea Kamanakapu╩╗u M─ühinulani N─üla╩╗ia╩╗ehuokalani Lumialani Kal─ükaua; November 16, 1836 ÔÇô January 20, 1891), was the last king and penultimate monarch of the Kingdom of Hawai╩╗i, reigning from February 12, 1874, u ...

was forced to accept a new constitution after a coup d'├ętat

A coup d'├ętat (; ; ), or simply a coup

, is typically an illegal and overt attempt by a military organization or other government elites to unseat an incumbent leadership. A self-coup is said to take place when a leader, having come to powe ...

by the Honolulu Rifles, a volunteer military

A volunteer military system or all-volunteer military system (AVMS) is a military service system that maintains the military only with applicants without conscription. A country may offer attractive pay and benefits through military recruitment t ...

unit recruited from American settlers. Queen Lili╩╗uokalani

Queen Lili╩╗uokalani (; Lydia Lili╩╗u Loloku Walania Kamaka╩╗eha; September 2, 1838 ÔÇô November 11, 1917) was the only queen regnant and the last sovereign monarch of the Hawaiian Kingdom, ruling from January 29, 1891, until the overthrow of th ...

, who succeeded Kal─ükaua in 1891, tried to abrogate the new constitution. She was subsequently overthrown in a 1893 coup engineered by the Committee of Safety, a group of Hawaiian subjects who were mostly of American descent, and supported by the U.S. military. The Committee of Safety dissolved the kingdom and established the Republic of Hawaii

The Republic of Hawaii (Hawaiian language, Hawaiian: ''Lepupalika o Hawaii'' epup╔Ö╦łlik╔Ö o h╔Ö╦łv╔Éj╩öi was a short-lived one-party state in Hawaii, Hawaii between July 4, 1894, when the Provisional Government of Hawaii had Black Week (H ...

, intending for the U.S. to annex the islands, which it did on July 7, 1898, via the Newlands Resolution

The Newlands Resolution, , was a joint resolution passed on July 7, 1898, by the United States Congress to annexation, annex the independent Republic of Hawaii. In 1900, Congress created the Territory of Hawaii.

The resolution was drafted by R ...

. Hawaii became part of the U.S. as the Territory of Hawaii

The Territory of Hawaii or Hawaii Territory (Hawaiian language, Hawaiian: ''Panalāʻau o Hawaiʻi'') was an organized incorporated territories of the United States, organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from Apri ...

until it became a U.S. state

In the United States, a state is a constituent political entity, of which there are 50. Bound together in a political union, each state holds governmental jurisdiction over a separate and defined geographic territory where it shares its so ...

in 1959.

In 1993, the United States Senate

The United States Senate is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the upper house, with the United States House of Representatives, U.S. House of Representatives being the lower house. Together, the Senate and ...

passed the Apology Resolution

Public Law 103-150, informally known as the Apology Resolution, is a Joint Resolution of the U.S. Congress adopted in 1993 that "acknowledges that the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii occurred with the active participation of agents and citiz ...

, which acknowledged that "the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawai╩╗i occurred with the active participation of agents and citizens of the United States" and "the Native Hawaiian people never directly relinquished to the United States their claims to their inherent sovereignty as a people over their national lands, either through the Kingdom of Hawai╩╗i or through a plebiscite or referendum." Opposition to the U.S. annexation of Hawaii played a major role in the creation of the Hawaiian sovereignty movement

The Hawaiian sovereignty movement () is a grassroots political and cultural campaign to reestablish an autonomous or independent nation or kingdom of Hawaii out of a desire for sovereignty, self-determination, and self-governance.

Some group ...

, which calls for Hawaiian independence from American rule.

History

Origin

Hawaii was originally settled by Polynesian voyagers from theMarquesas Islands

The Marquesas Islands ( ; or ' or ' ; Marquesan language, Marquesan: ' (North Marquesan language, North Marquesan) and ' (South Marquesan language, South Marquesan), both meaning "the land of men") are a group of volcano, volcanic islands in ...

or Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian language, Tahitian , ; ) is the largest island of the Windward Islands (Society Islands), Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia, an overseas collectivity of France. It is located in the central part of t ...

. The date of their first arrival is uncertain. Early archaeological studies suggested they may have arrived as early as the 3rd century CE, while more recent analyses suggest that they did not arrive until around 900ÔÇô1200 CE. The islands were governed as independent chiefdoms.

In ancient Hawai╩╗i, society was divided into multiple classes. Rulers came from the ''ali╩╗i'' class with each island ruled by a separate ''ali╩╗i nui''. These rulers were believed to come from a hereditary line descended from the first Polynesian, Papa, who became the earth mother goddess of the Hawaiian religion. Captain James Cook

Captain (Royal Navy), Captain James Cook (7 November 1728 ÔÇô 14 February 1779) was a British Royal Navy officer, explorer, and cartographer famous for his three voyages of exploration to the Pacific and Southern Oceans, conducted between 176 ...

was the first European to encounter the Hawaiian Islands, on his Pacific third voyage (1776ÔÇô1780). He was killed at Kealakekua Bay

Kealakekua Bay is located on the Kona coast of the island of Hawaii about south of Kailua-Kona. Settled over a thousand years ago, the surrounding area contains many archeological and historical sites such as religious temples ( heiaus) an ...

on Hawai╩╗i Island in 1779 in a dispute over the taking of a longboat. Three years later the island passed to Kalani╩╗┼Źpu╩╗u

Kalani┼Źpuu-a-Kaiamamao (c. 1729 ÔÇô April 1782) was the ali╩╗i nui (supreme monarch) of the island of Hawai╩╗i. He was called ''Terreeoboo, King of Owhyhee'' by James Cook and other Europeans. His name has also been written as Kaleiopuu.

Bio ...

's son, K─źwala╩╗┼Ź, while religious authority was passed to the ruler's nephew, Kamehameha.

In 1782, the warrior chief who became Kamehameha the Great, started a military campaign to unite the islands that would last 15 years. He established the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1795 with the help of western weapons and advisors, such as John Young and Isaac Davis. Although successful in attacking both O╩╗ahu and Maui

Maui (; Hawaiian language, Hawaiian: ) is the second largest island in the Hawaiian archipelago, at 727.2 square miles (1,883 km2). It is the List of islands of the United States by area, 17th-largest in the United States. Maui is one of ...

, he failed to annex Kaua╩╗i

Kauai (), anglicized as Kauai ( or ), is one of the main Hawaiian Islands.

It has an area of 562.3 square miles (1,456.4 km2), making it the fourth-largest of the islands and the 21st-largest island in the United States. Kauai lies 73 mi ...

, hampered by a storm and a plague that decimated his army. In 1810 Kaua╩╗i's chief swore allegiance to Kamehameha. The unification ended ancient Hawaii

Ancient Hawaii is the period of Hawaiian history preceding the establishment in 1795 of the Kingdom of Hawaii by Kamehameha the Great. Traditionally, researchers estimated the first settlement of the Hawaiian islands as having occurred sporad ...

an society, transforming it into a constitutional monarchy

Constitutional monarchy, also known as limited monarchy, parliamentary monarchy or democratic monarchy, is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in making decisions. ...

in the manner of European systems. The Kingdom thus became an early example of monarchies in Polynesian societies as contacts with Europeans increased. Similar political developments occurred (for example) in Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian language, Tahitian , ; ) is the largest island of the Windward Islands (Society Islands), Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia, an overseas collectivity of France. It is located in the central part of t ...

, Tonga

Tonga, officially the Kingdom of Tonga, is an island country in Polynesia, part of Oceania. The country has 171 islands, of which 45 are inhabited. Its total surface area is about , scattered over in the southern Pacific Ocean. accordin ...

, Fiji

Fiji, officially the Republic of Fiji, is an island country in Melanesia, part of Oceania in the South Pacific Ocean. It lies about north-northeast of New Zealand. Fiji consists of an archipelago of more than 330 islandsÔÇöof which about ...

, and New Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmassesÔÇöthe North Island () and the South Island ()ÔÇöand List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

(see the M─üori King Movement

M─üori or Maori can refer to:

Relating to the M─üori people

* M─üori people of New Zealand, or members of that group

* M─üori language, the language of the M─üori people of New Zealand

* M─üori culture

* Cook Islanders, the M─üori people of the Co ...

).

Kamehameha dynasty (1795ÔÇô1874)

From 1810 to 1893 two major dynastic families ruled the Hawaiian Kingdom: theHouse of Kamehameha

The House of Kamehameha ''(Hale O Kamehameha)'', or the Kamehameha dynasty, was the reigning royal family of the Hawaiian Kingdom, Kingdom of Hawaii, beginning with its founding by Kamehameha I in 1795 and ending with the death of Kamehameha V in ...

(1795 to 1874) and the Kal─ükaua dynasty (1874ÔÇô1893). Five members of the Kamehameha family led the government, each styled as ''Kamehameha'', until 1872. Lunalilo

Lunalilo (William Charles Lunalilo; January 31, 1835 ÔÇô February 3, 1874) was the sixth monarch of the Kingdom of Hawaii from his election on January 8, 1873, until his death a year later.

Born to Kek─üuluohi and High Chief Charles Kana╩╗in ...

() was a member of the House of Kamehameha through his mother. Liholiho (Kamehameha II

Kamehameha II (November 1797 ÔÇô July 14, 1824) was the second king of the Hawaiian Kingdom, Kingdom of Hawaii from 1819 to 1824. His birth name was Liholiho and full name was Kalaninui kua Liholiho i ke kapu ╩╗Iolani. It was lengthened to Kala ...

, ) and Kauikeaouli (Kamehameha III

Kamehameha III (born Kauikeaouli) (March 17, 1814 ÔÇô December 15, 1854) was the third king of the Kingdom of Hawaii from 1825 to 1854. His full Hawaiian name was Keaweaweula K─źwala┼Ź Kauikeaouli Kaleiopapa and then lengthened to Keaweaweula K ...

, ) were direct sons of Kamehameha the Great.

During Liholiho's (Kamehameha II) reign (1819ÔÇô1824), the arrival of Christian missionaries and whalers accelerated changes in the kingdom.

Kauikeaouli's reign (1824ÔÇô1854) as Kamehameha III, began as a young ward of the primary wife of Kamehameha the Great, Queen Ka╩╗ahumanu, who ruled as Queen Regent

In a monarchy, a regent () is a person appointed to govern a state because the actual monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge their powers and duties, or the throne is vacant and a new monarch has not yet been dete ...

and ''Kuhina Nui

Kuhina Nui was a powerful office in the Kingdom of Hawaii from 1819 to 1864. It was usually held by a relative of the king and was the rough equivalent of the 19th-century European office of Prime Minister or sometimes Regent.

Origin of the offi ...

'', or Prime Minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

until her death in 1832. Kauikeaouli's rule of three decades was the longest in the monarchy's history. He enacted the Great Mahele of 1848, promulgated the first Constitution (1840) and its successor (1852) and witnessed cataclysmic losses of his people through imported diseases.

Alexander Liholiho, Kamehameha IV, (r. 1854ÔÇô1863), introduced Anglican

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

religion and royal habits to the kingdom.

Lot, Kamehameha V (r. 1863ÔÇô1872), struggled to solidify Hawaiian nationalism in the kingdom.

Succession crisis and monarchical elections

Dynastic rule by the Kamehameha family ended in 1872 with the death of Kamehameha V. On his deathbed, he summoned High ChiefessBernice Pauahi Bishop

Bernice Pauahi P─ük─ź Bishop KGCOK RoK (December 19, 1831 – October 16, 1884) was an '' alii'' (noble) of the royal family of the Kingdom of Hawaii and a well known philanthropist.

Ancestry, birth and early life

Pauahi was born in Hon ...

to declare his intentions of making her heir to the throne. Bernice refused the crown, and Kamehameha V died without naming an heir.

Bishop's refusal to take the crown forced the legislature to elect a new monarch. From 1872 to 1873, several relatives of the Kamehameha line were nominated. In the monarchical election of 1873, a ceremonial popular vote and a unanimous legislative vote, William C. Lunalilo, grandnephew of Kamehameha I, became Hawai╩╗i's first of two elected monarchs. His reign ended due to his early death from tuberculosis at age 39.

Upon Lunalilo's death, David Kalakaua defeated Kamehameha IV's widow, Queen Emma, in a contested election, beginning the second dynasty.

Kal─ükaua dynasty

Like his predecessor, Lunalilo failed to name an heir to the throne. Once again, the legislature of the Hawaiian Kingdom held an election to fill the vacancy. Queen Emma, widow of Kamehameha IV, was nominated along with David Kal─ükaua. The 1874 election was a nasty campaign in which both candidates resorted to mudslinging and innuendo. Kal─ükaua became the second elected King of Hawai╩╗i but without the ceremonial popular vote of Lunalilo. The choice was controversial, and U.S. and British troops were called upon to suppress rioting by Queen Emma's supporters, the '' Emmaites''.

Kal─ükaua officially proclaimed that his sister, Lili╩╗uokalani, would succeed to the throne upon his death. Hoping to avoid uncertainty, Kal─ükaua listed a line of succession in his will, so that after Lili╩╗uokalani the throne should succeed to Princess Victoria Ka╩╗iulani, then to Queen Consort

Like his predecessor, Lunalilo failed to name an heir to the throne. Once again, the legislature of the Hawaiian Kingdom held an election to fill the vacancy. Queen Emma, widow of Kamehameha IV, was nominated along with David Kal─ükaua. The 1874 election was a nasty campaign in which both candidates resorted to mudslinging and innuendo. Kal─ükaua became the second elected King of Hawai╩╗i but without the ceremonial popular vote of Lunalilo. The choice was controversial, and U.S. and British troops were called upon to suppress rioting by Queen Emma's supporters, the '' Emmaites''.

Kal─ükaua officially proclaimed that his sister, Lili╩╗uokalani, would succeed to the throne upon his death. Hoping to avoid uncertainty, Kal─ükaua listed a line of succession in his will, so that after Lili╩╗uokalani the throne should succeed to Princess Victoria Ka╩╗iulani, then to Queen Consort Kapi╩╗olani

Kapi╩╗olani (December 31, 1834 ÔÇô June 24, 1899) was the queen of the Kingdom of Hawai╩╗i as the consort of M┼Ź╩╗─ź (king) Kal─ükaua, who reigned from 1874 until his death in 1891, when she became known as the Dowager Queen Kapi╩╗olani. Dee ...

, followed by her sister Princess Po╩╗omaikelani, then Prince David La╩╗amea Kaw─ünanakoa, and finally Prince Jonah K┼źhi┼Ź Kalaniana╩╗ole

Jonah K┼źhi┼Ź Kalaniana╩╗ole (March 26, 1871 ÔÇô January 7, 1922) was a prince of the Kingdom of Hawai╩╗i until it was overthrown by a coalition of American and European businessmen in 1893. He later went on to become the delegate of the Territo ...

. However, the will was not a proper proclamation according to kingdom law. Protests objected to nominating lower ranking ali╩╗i who were not eligible to the throne while high ranking ali╩╗i were available who were eligible, such as High Chiefess Elizabeth Keka╩╗aniau

Elizabeth Keka╩╗aniau La╩╗anui Pratt, full name Elizabeth Keka╩╗aniauokalani Kalaninuiohilaukapu Kekaikuihala La╩╗anui Pratt (September 11, 1834 ÔÇô December 20, 1928), was a Hawaiian high chiefess (ali╩╗i) and great-grandniece of Kamehameha I, ...

. However, Queen Lili╩╗uokalani held the royal prerogative and she officially proclaimed her niece Princess Ka╩╗iulani as heir. She later proposed a new constitution in 1893, but it was never ratified by the legislature.

Kal─ükaua's prime minister Walter M. Gibson indulged the expenses of Kal─ükaua and attempted to establish a Polynesian Confederation, sending the "homemade battleship" Kaimiloa to Samoa in 1887. It resulted in suspicion by the German Navy

The German Navy (, ) is part of the unified (Federal Defense), the German Armed Forces. The German Navy was originally known as the ''Bundesmarine'' (Federal Navy) from 1956 to 1995, when ''Deutsche Marine'' (German Navy) became the official ...

.

Bayonet Constitution

The 1887 Constitution of the Hawaiian Kingdom was drafted by Lorrin A. Thurston, Minister of Interior under King Kal─ükaua. The constitution was proclaimed by the king after a meeting of 3,000 residents, including an armed militia demanded he sign or be deposed. The document created aconstitutional monarchy

Constitutional monarchy, also known as limited monarchy, parliamentary monarchy or democratic monarchy, is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in making decisions. ...

like that of the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

, stripping the King of most of his personal authority, empowering the legislature and establishing a cabinet government. It became known as the "Bayonet Constitution" over the threat of force used to gain Kal─ükaua's cooperation.

The 1887 constitution empowered the citizenry to elect members of the House of Nobles (who had previously been appointed by the King). It increased the value of property a citizen must own to be eligible to vote above the previous Constitution of 1864. It also denied voting rights to Asians who comprised a large proportion of the population (a few Japanese and some Chinese who had previously become naturalized

Naturalization (or naturalisation) is the legal act or process by which a non-national of a country acquires the nationality of that country after birth. The definition of naturalization by the International Organization for Migration of the ...

lost voting rights). This limited the franchise to wealthy native Hawaiians and Europeans. The Bayonet Constitution continued allowing the monarch to appoint cabinet ministers, but took his power to dismiss them without approval from the Legislature.

Lili╩╗uokalani's Constitution

In 1891, Kal─ükaua died and his sister Lili╩╗uokalani assumed the throne. She came to power during an economic crisis precipitated in part by theMcKinley Tariff

The Tariff Act of 1890, commonly called the McKinley Tariff, was an act of the United States Congress framed by then-Representative William McKinley, that became law on October 1, 1890. The tariff raised the average duty on imports to almost 50% ...

. By rescinding the Reciprocity Treaty of 1875, the new tariff eliminated the previous advantage Hawaiian exporters enjoyed in trade to U.S. markets. Many Hawaiian businesses and citizens felt the lost revenue, and so Lili╩╗uokalani proposed a lottery

A lottery (or lotto) is a form of gambling that involves the drawing of numbers at random for a prize. Some governments outlaw lotteries, while others endorse it to the extent of organizing a national or state lottery. It is common to find som ...

and opium licensing to bring in additional revenue. Her ministers and closest friends tried to dissuade her from pursuing the bills, and these controversial proposals were used against her in the looming constitutional crisis.

Lili╩╗uokalani wanted to restore power to the monarch by abrogating the 1887 Constitution. She launched a campaign resulting in a petition to proclaim a new Constitution. Many citizens and residents who in 1887 had forced Kal─ükaua to sign the "Bayonet Constitution" became alarmed when three of her cabinet members informed them that the queen was planning to unilaterally proclaim her new Constitution. Some members were reported to have feared for their safety for not supporting her plans.

Overthrow

In 1893, local businessmen and politicians, composed of six non-native Hawaiian Kingdom subjects, five American nationals, one British national, and one German national, all of whom were living in Hawai╩╗i, overthrew the regime and took over the government. Historians suggest that businessmen were in favor of overthrow and annexation to the U.S. in order to benefit from more favorable trade conditions. United States Government Minister John L. Stevens summoned a company of uniformed U.S. Marines from the and two companies of U.S. sailors to Honolulu to take up positions at the U.S. Legation, Consulate and Arion Hall on the afternoon of January 16, 1893. This deployment was at the request of the Committee of Safety, which claimed an "imminent threat to American lives and property." Stevens was accused of ordering the landing on his own authority and inappropriately using his discretion. Historian William Russ concluded that "the injunction to prevent fighting of any kind made it impossible for the monarchy to protect itself." On July 17, 1893, Sanford B. Dole and his committee took control of the government and declared itself theProvisional Government of Hawaii

The Provisional Government of Hawaii (abbr.: P.G.; Hawaiian language, Hawaiian: ''Aupuni K┼źikaw─ü o Hawai╩╗i'') was proclaimed after the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom on January 17, 1893, by the 13-member Committee of Safety (Hawaii), Co ...

"to rule until annexation by the United States". The Provisional Government was reorganized as the Republic of Hawaii

The Republic of Hawaii (Hawaiian language, Hawaiian: ''Lepupalika o Hawaii'' epup╔Ö╦łlik╔Ö o h╔Ö╦łv╔Éj╩öi was a short-lived one-party state in Hawaii, Hawaii between July 4, 1894, when the Provisional Government of Hawaii had Black Week (H ...

in 1894; Dole served as president of both. The committee and members of the former government both lobbied in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

for their respective positions.

President Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was the 22nd and 24th president of the United States, serving from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. He was the first U.S. president to serve nonconsecutive terms and the first Hist ...

considered the overthrow to have been an illegal act of war; he refused to consider annexation and initially worked to restore the queen to her throne. Between December 14, 1893, and January 11, 1894, a standoff known as the Black Week occurred between the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

, the Empire of Japan

The Empire of Japan, also known as┬áthe Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was the Japanese nation state that existed from the Meiji Restoration on January 3, 1868, until the Constitution of Japan took effect on May 3, 1947. From JapanÔÇôKor ...

and the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

against the Provisional Government to pressure them into returning the Queen. This incident drove home the message that President Cleveland wanted Queen Lili╩╗uokalani's return to power. On July 4, 1894, the Republic of Hawaii was requested to wait for the end of President Cleveland's second term. While lobbying continued during 1894, the royalist faction amassed an army 600 strong led by former Captain of the Guard Samuel Nowlein. In 1895 they attempted the 1895 Wilcox rebellion

The 1895 Wilcox rebellion or the Counter-Revolution of 1895 was a brief war from January 6 to January 9, 1895, that consisted of three battles on the island of Oahu, Republic of Hawaii. It was the last major military operation by royalists who Op ...

. Lili╩╗uokalani

Queen Lili╩╗uokalani (; Lydia Lili╩╗u Loloku Walania Kamaka╩╗eha; September 2, 1838 ÔÇô November 11, 1917) was the only queen regnant and the last sovereign monarch of the Hawaiian Kingdom, ruling from January 29, 1891, until the overthrow of th ...

was arrested when a weapons cache was found on the palace grounds. She was tried by a military tribunal of the Republic, convicted of knowledge of treason, and placed under permanent house arrest.

On January 24, 1895, while under house arrest Lili╩╗uokalani

Queen Lili╩╗uokalani (; Lydia Lili╩╗u Loloku Walania Kamaka╩╗eha; September 2, 1838 ÔÇô November 11, 1917) was the only queen regnant and the last sovereign monarch of the Hawaiian Kingdom, ruling from January 29, 1891, until the overthrow of th ...

was forced to sign a five-page declaration as "Liliuokalani Dominis", not written by her, which states that she formally abdicated the throne. This was to be in return for the release and commutation of the death sentences of her jailed supporters, including Minister Joseph N─üwah─ź, Prince Kaw─ünanakoa, Robert William Wilcox and Prince Jonah K┼źhi┼Ź.

The Republic of Hawaii was dissolved and the Hawaiian Islands were annexed by the United States by the Joint Resolution to Provide for Annexing the Hawaiian Islands to the United States, known as the "Newlands Resolution

The Newlands Resolution, , was a joint resolution passed on July 7, 1898, by the United States Congress to annexation, annex the independent Republic of Hawaii. In 1900, Congress created the Territory of Hawaii.

The resolution was drafted by R ...

".

Economic, social, and cultural transformation

Economic and demographic factors in the 19th century reshaped the islands. Their consolidation opened international trade. Under Kamehameha (1795ÔÇô1819),sandalwood

Sandalwood is a class of woods from trees in the genus ''Santalum''. The woods are heavy, yellow, and fine-grained, and, unlike many other aromatic woods, they retain their fragrance for decades. Sandalwood oil is extracted from the woods. Sanda ...

was exported to China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

. That led to the introduction of money and trade throughout the islands.

Following Kamehameha's death, succession was overseen by his principal wife, Ka╩╗ahumanu

Ka╩╗ahumanu (March 17, 1768 ÔÇô June 5, 1832) (''"the feathered mantle"'') was queen consort and acted as regent of the Kingdom of Hawai╩╗i as Kuhina Nui. She was the favorite wife of King Kamehameha I and also the most politically powe ...

, who was designated as regent over the new king, Liholiho, who was a minor.

Queen Ka╩╗ahumanu eliminated various prohibitions ( kapu) governing women's behavior. She allowed men and women to eat together and women to eat bananas. She also overturned the old religion in favor of Christianity. The missionaries developed a written Hawaiian language

Hawaiian (', ) is a critically endangered Polynesian language of the Austronesian language family, originating in and native to the Hawaiian Islands. It is the native language of the Hawaiian people. Hawaiian, along with English, is an offi ...

. That led to high levels of literacy in Hawai╩╗i, above 90 percent in the latter half of the 19th century. Writing aided in the consolidation of government. Written constitutions were developed.

In 1848, the Great M─ühele was promulgated by King Kamehameha III

Kamehameha III (born Kauikeaouli) (March 17, 1814 ÔÇô December 15, 1854) was the third king of the Kingdom of Hawaii from 1825 to 1854. His full Hawaiian name was Keaweaweula K─źwala┼Ź Kauikeaouli Kaleiopapa and then lengthened to Keaweaweula K ...

. It instituted official property rights, formalizing the customary land tenure system in effect prior to this declaration. Ninety-eight percent of the land was assigned to the ali╩╗i

The ali╩╗i were the traditional nobility of the Hawaiian islands. They were part of a hereditary line of rulers, the ''noho ali╩╗i''.

Cognates of the word ''ali╩╗i'' have a similar meaning in other Polynesian languages; in M─üori it is pronoun ...

, chiefs or nobles, with two percent to the commoners. No land could be sold, only transferred to a lineal descendant.

Contact with the outer world exposed the natives to a disastrous series of imported plagues such as smallpox. The native Hawaiian population fell from approximately 128,000 in 1778 to 71,000 in 1853, reaching a low of 24,000 in 1920. Most lived in remote villages.

American missionaries converted most of the natives to Christianity. The missionaries and their children became a powerful elite by the mid-19th century. They provided the chief advisors and cabinet members of the kings and dominated the professional and merchant class in the cities.

The elites promoted the sugar

Sugar is the generic name for sweet-tasting, soluble carbohydrates, many of which are used in food. Simple sugars, also called monosaccharides, include glucose

Glucose is a sugar with the Chemical formula#Molecular formula, molecul ...

industry

Industry may refer to:

Economics

* Industry (economics), a generally categorized branch of economic activity

* Industry (manufacturing), a specific branch of economic activity, typically in factories with machinery

* The wider industrial sector ...

. Americans set up plantations after 1850. Few natives were willing to work on them, so recruiters fanned out across Asia and Europe. As a result, between 1850 and 1900, some 200,000 contract laborers from China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

, Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

, the Philippines

The Philippines, officially the Republic of the Philippines, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. Located in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of List of islands of the Philippines, 7,641 islands, with a tot ...

, Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, is a country on the Iberian Peninsula in Southwestern Europe. Featuring Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point in continental Europe, Portugal borders Spain to its north and east, with which it share ...

and elsewhere worked in Hawai╩╗i under fixed term contracts (typically for five years). Most returned home on schedule, but many settled there. By 1908 about 180,000 Japanese workers had arrived. No more were allowed in, but 54,000 remained permanently.

Military

The Hawaiian army and navy developed from the warriors of Kona under Kamehameha I. The army and navy used both traditionalcanoe

A canoe is a lightweight, narrow watercraft, water vessel, typically pointed at both ends and open on top, propelled by one or more seated or kneeling paddlers facing the direction of travel and using paddles.

In British English, the term ' ...

s and uniforms including helmets made of natural materials and loincloth

A loincloth is a one-piece garment, either wrapped around itself or kept in place by a belt. It covers the genitals and sometimes the buttocks. Loincloths which are held up by belts or strings are specifically known as breechcloth or breechclo ...

s (called the ''malo'' ) as well as Western technology such as artillery cannons, muskets and ships and Western-style organization such as military uniforms and a military rank system. European advisors were treated well and became Hawaiian citizens. When Kamehameha died in 1819 he left his son Liholiho a large arsenal with tens of thousands of soldiers and many warships. This helped put down the revolt at Kuamo╩╗o later in 1819 and Humehume's rebellion on Kaua╩╗i in 1824.

The military shrank with the population under the onslaught of disease, so by the end of the Kamehameha dynasty the Hawaiian navy was severely reduced, having a few outdated ships and the army consisted of a few hundred troops. After a French invasion that sacked Honolulu

Honolulu ( ; ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Hawaii, located in the Pacific Ocean. It is the county seat of the Consolidated city-county, consolidated City and County of Honol ...

in 1849, Kamehameha III sought defense treaties with the United States and Britain. During the Crimean War

The Crimean War was fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the Second French Empire, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Kingdom of Sardinia (1720ÔÇô1861), Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont fro ...

, Kamehameha III declared Hawai╩╗i a neutral state. The United States government put strong pressure on Kamehameha IV to trade exclusively with the United States, threatening to annex the islands. To counter this threat Kamehameha IV and Kamehameha V pushed for alliances with other foreign powers, especially Great Britain. Hawai╩╗i claimed uninhabited islands in the Pacific, including the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands

The Northwestern Hawaiian Islands also known as the Leeward Hawaiian Islands, are a series of islands and atolls located northwest of Kauai and Niihau, Niihau in the Hawaiian Islands, Hawaiian island chain. Politically, these islands are part of ...

, many of which conflicted with American claims.

The royal guards were disbanded under Lunalilo

Lunalilo (William Charles Lunalilo; January 31, 1835 ÔÇô February 3, 1874) was the sixth monarch of the Kingdom of Hawaii from his election on January 8, 1873, until his death a year later.

Born to Kek─üuluohi and High Chief Charles Kana╩╗in ...

after a barracks revolt in September 1873. A small army was restored under King Kal─ükaua

Kal─ükaua (David La╩╗amea Kamanakapu╩╗u M─ühinulani N─üla╩╗ia╩╗ehuokalani Lumialani Kal─ükaua; November 16, 1836 ÔÇô January 20, 1891), was the last king and penultimate monarch of the Kingdom of Hawai╩╗i, reigning from February 12, 1874, u ...

but failed to stop the 1887 Rebellion by the Missionary Party. The U.S. maintained a policy of keeping at least one cruiser

A cruiser is a type of warship. Modern cruisers are generally the largest ships in a fleet after aircraft carriers and amphibious assault ships, and can usually perform several operational roles from search-and-destroy to ocean escort to sea ...

in Hawai╩╗i. On January 17, 1893, Lili╩╗uokalani, believing the U.S. military would intervene if she changed the constitution, waited for the to leave port. Once it was known that Lili╩╗uokalani was revising the constitution, the ''Boston'' returned and assisted the Missionary Party in her overthrow. Following the establishment of the Provisional Government of Hawaii

The Provisional Government of Hawaii (abbr.: P.G.; Hawaiian language, Hawaiian: ''Aupuni K┼źikaw─ü o Hawai╩╗i'') was proclaimed after the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom on January 17, 1893, by the 13-member Committee of Safety (Hawaii), Co ...

, the Kingdom's military was disarmed and disbanded.

French Incident (1839)

Under Queen Ka╩╗ahumanu's rule, Catholicism was illegal in Hawai╩╗i, and in 1831 French Catholic priests were deported. Native Hawaiian converts to Catholicism claimed to have been imprisoned, beaten and tortured after the expulsion of the priests. Resistance toward the French Catholic missionaries continued underKuhina Nui

Kuhina Nui was a powerful office in the Kingdom of Hawaii from 1819 to 1864. It was usually held by a relative of the king and was the rough equivalent of the 19th-century European office of Prime Minister or sometimes Regent.

Origin of the offi ...

Ka╩╗ahumanu II.

In 1839 Captain Laplace of the French frigate ''Art├ęmise'' sailed to Hawai╩╗i under orders to:

:''Destroy the malevolent impression which you find established to the detriment of the French name; to rectify the erroneous opinion which has been created as to the power of France; and to make it well understood that it would be to the advantage of the chiefs of those islands of the Ocean to conduct themselves in such a manner as not to incur the wrath of France. You will exact, if necessary with all the force that is yours to use, complete reparation for the wrongs which have been committed, and you will not quit those places until you have left in all minds a solid and lasting impression.''

Under the threat of war, King Kamehameha III

Kamehameha III (born Kauikeaouli) (March 17, 1814 ÔÇô December 15, 1854) was the third king of the Kingdom of Hawaii from 1825 to 1854. His full Hawaiian name was Keaweaweula K─źwala┼Ź Kauikeaouli Kaleiopapa and then lengthened to Keaweaweula K ...

signed the Edict of Toleration on July 17, 1839, agreeing to Laplace's demands. He paid $20,000 in compensation for deporting the priests and the incarceration and torture of converts. The kingdom proclaimed:

:''That the Catholic worship be declared free, throughout all the dominions subject to the King of the Sandwich Islands; the members of this religious faith shall enjoy in them the privileges granted to Protestants.''

The Roman Catholic Diocese of Honolulu

The Diocese of Honolulu () is a Latin Church ecclesiastical territory or diocese for the state of Hawaii in the United States. It is a suffragan diocese in the ecclesiastical province of the metropolitan Roman Catholic Archdiocese of San Francisc ...

returned and as reparation Kamehameha III donated land for a church.

Invasions

Paulet Affair (1843)

On February 13, 1843. Lord George Paulet of theRoyal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

warship , entered Honolulu Harbor and demanded that King Kamehameha III cede the islands to the British Crown. Under the frigate's guns, Kamehameha III surrendered to Paulet on February 25, writing:

"Where are you, chiefs, people, and commons from my ancestors, and people from foreign lands? Hear ye! I make known to you that I am in perplexity by reason of difficulties into which I have been brought without cause, therefore I have given away the life of our land. Hear ye! but my rule over you, my people, and your privileges will continue, for I have hope that the life of the land will be restored when my conduct is justified. Done at Honolulu, Oahu, this 25th day of February, 1843. Kamehameha III Kekauluohi"Gerrit P. Judd, a missionary who had become the minister of finance for the Kingdom, secretly arranged for J.F.B. Marshall to be sent to the United States, France and Britain, to protest Paulet's actions. Marshall, a commercial agent of Ladd & Co., conveyed the Kingdom's complaint to the vice consul of Britain in Tepec. Rear Admiral Richard Darton Thomas, Paulet's commanding officer, arrived at Honolulu harbor on July 26, 1843, on from

Valpara├şso

Valpara├şso () is a major city, Communes of Chile, commune, Port, seaport, and naval base facility in the Valpara├şso Region of Chile. Valpara├şso was originally named after Valpara├şso de Arriba, in CastillaÔÇôLa Mancha, Castile-La Mancha, Spain ...

, Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in western South America. It is the southernmost country in the world and the closest to Antarctica, stretching along a narrow strip of land between the Andes, Andes Mountains and the Paci ...

. Admiral Thomas apologized to Kamehameha III for Paulet's actions, and restored Hawaiian sovereignty on July 31, 1843. In his restoration speech, Kamehameha III declared that ''"Ua Mau ke Ea o ka ╩╗─Çina i ka Pono

''Ua Mau ke Ea o ka ─Çina i ka Pono'' () is a Hawaiian language, Hawaiian phrase, spoken by Kamehameha III, and adopted in 1959 as the state motto. It is most commonly translated as "the life of the land is perpetuated in righteousness." An alte ...

"'' (The life of the land is perpetuated in righteousness), the motto of the future State of Hawaii. The day was celebrated as ''L─ü Ho╩╗iho╩╗i Ea'' ( Sovereignty Restoration Day).

French invasion (1849)

In August 1849, French admiral Louis Tromelin arrived inHonolulu Harbor

Honolulu Harbor, also called ''Kulolia'' and ''Ke Awa O Kou'' and the Port of Honolulu, is the principal seaport of Honolulu, Hawaii, Honolulu and the Hawaii, State of Hawaii in the United States. From the harbor, the Honolulu County, Hawaii, City ...

with the ''La Poursuivante'' and ''Gassendi''. De Tromelin made ten demands to King Kamehameha III

Kamehameha III (born Kauikeaouli) (March 17, 1814 ÔÇô December 15, 1854) was the third king of the Kingdom of Hawaii from 1825 to 1854. His full Hawaiian name was Keaweaweula K─źwala┼Ź Kauikeaouli Kaleiopapa and then lengthened to Keaweaweula K ...

on August 22, mainly that full religious rights be given to Catholics, (Catholics enjoyed only partial religious rights). On August 25 the demands had not been met. After a second warning, French troops overwhelmed the skeleton force and captured Honolulu Fort, spiked the coastal guns and destroyed all other weapons they found (mainly muskets and ammunition). They raided government buildings and general property in Honolulu, causing $100,000 in damage. After the raids the invasion force withdrew to the fort. De Tromelin eventually recalled his men and left Hawai╩╗i on September 5.

Foreign relations

Anticipating foreign encroachment on Hawaiian territory, King Kamehameha III dispatched a delegation to the United States and Europe to secure recognition of Hawaiian independence. Timoteo Ha╩╗alilio, William Richards and Sir George Simpson were commissioned as joint ministers plenipotentiary on April 8, 1842. Simpson went to Great Britain while Ha╩╗alilio and Richards traveled to the United States. The Hawaiian delegation secured the assurance of Hawaiian independence by U.S. presidentJohn Tyler

John Tyler (March 29, 1790 ÔÇô January 18, 1862) was the tenth president of the United States, serving from 1841 to 1845, after briefly holding office as the tenth vice president of the United States, vice president in 1841. He was elected ...

on December 19, 1842. They then met Simpson in Europe to secure formal recognition by the United Kingdom and France. On March 17, 1843, King Louis Philippe of France recognized Hawaiian independence at the urging of King Leopold I of Belgium

Leopold I (16 December 1790 ÔÇô 10 December 1865) was the first king of the Belgians, reigning from 21 July 1831 until his death in 1865.

The youngest son of Francis, Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, Leopold took a commission in the Imperial Rus ...

. On April 1, 1843, Lord Aberdeen, on behalf of Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 ÔÇô 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in January 1901. Her reign of 63 year ...

, assured the Hawaiian delegation, "Her Majesty's Government was willing and had determined to recognize the independence of the Sandwich Islands under their present sovereign."

Anglo-Franco Proclamation

On November 28, 1843, at the Court of London, the British and French governments formally recognized Hawaiian independence. The "Anglo-Franco Proclamation", a joint declaration by France and Britain, signed by King Louis-Philippe and Queen Victoria, assured the Hawaiian delegation:

On November 28, 1843, at the Court of London, the British and French governments formally recognized Hawaiian independence. The "Anglo-Franco Proclamation", a joint declaration by France and Britain, signed by King Louis-Philippe and Queen Victoria, assured the Hawaiian delegation:

Her Majesty the Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and His Majesty the King of the French, taking into consideration the existence in the Sandwich Islands (Hawaiian Islands) of a government capable of providing for the regularity of its relations with foreign nations, have thought it right to engage, reciprocally, to consider the Sandwich Islands as an Independent State, and never to take possession, neither directly or under the title of Protectorate, or under any other form, of any part of the territory of which they are composed. The undersigned, Her Majesty's Principal Secretary of State of Foreign Affairs, and the Ambassador Extraordinary of His Majesty the King of the French, at the Court of London, being furnished with the necessary powers, hereby declare, in consequence, that their said Majesties take reciprocally that engagement. In witness whereof the undersigned have signed the present declaration, and have affixed thereto the seal of their arms. Done in duplicate at London, the 28th day of November, in the year of our Lord, 1843.Hawai╩╗i was the first non-European indigenous state whose independence was recognized by the major powers. The United States declined to join France and the United Kingdom in this statement, even though PresidentABERDEEN Aberdeen ( ; ; ) is a port city in North East Scotland, and is the List of towns and cities in Scotland by population, third most populous Cities of Scotland, Scottish city. Historically, Aberdeen was within the historic county of Aberdeensh .... .S.br/> ST. AULAIRE. .S.ref name="503-517">

John Tyler

John Tyler (March 29, 1790 ÔÇô January 18, 1862) was the tenth president of the United States, serving from 1841 to 1845, after briefly holding office as the tenth vice president of the United States, vice president in 1841. He was elected ...

had verbally recognized Hawaiian independence. In 1849 the United States formally recognized Hawaiian independence.

November 28, ''L─ü K┼ź╩╗oko╩╗a'' (Independence Day), became a Hawaiian national holiday to celebrate the recognition. The Hawaiian Kingdom entered into treaties with most major countries and established over 90 legations and consulates.

Princes and chiefs who were eligible to be rulers

In 1839, King Kamehameha III created the Chief's Children's School (Royal School) and selected of the 16 highest-ranking ali╩╗i to be eligible to rule and gave them the highest education and proper etiquette. They were required to attend boarding school under the direction of Amos Starr Cooke and his wife. The eligible princes and chiefs:Moses Kek┼ź─üiwa

Moses Kek┼ź─üiwa (July 20, 1829 ÔÇô November 24, 1848) was a member of the royal family of the Kingdom of Hawaii.

Early life and family

Kek┼ź─üiwa was born on July 20, 1829, in Honolulu, as noted by American merchant Stephen Reynolds, who ca ...

, Alexander Liholiho, Lot Kamehameha, Victoria Kam─ümalu

Victoria Kam─ümalu Ka╩╗ahumanu IV (November 1, 1838 ÔÇô May 29, 1866) was ''Kuhina Nui'' of Hawaii and its crown princess. Named Wikolia Kamehamalu Keawenui Ka╩╗ahumanu-a-Kek┼źana┼Ź╩╗a and also named Kalehelani Kiheahealani, she was mainly refe ...

, Emma Rooke, William Lunalilo, David Kal─ükaua, Lydia Kamaka╩╗eha, Bernice Pauahi, Elizabeth Keka╩╗aniau

Elizabeth Keka╩╗aniau La╩╗anui Pratt, full name Elizabeth Keka╩╗aniauokalani Kalaninuiohilaukapu Kekaikuihala La╩╗anui Pratt (September 11, 1834 ÔÇô December 20, 1928), was a Hawaiian high chiefess (ali╩╗i) and great-grandniece of Kamehameha I, ...

, Jane Loeau, Abigail Maheha, Peter Young Kaeo, James Kaliokalani, John Pitt K─źna╩╗u and Mary Pa╩╗a╩╗─üina, officially declared by King Kamehameha III in 1844.

Territorial extent

The Kingdom formed in 1795. In the Battle of Nu╩╗uanu Kamehameha conqueredMaui

Maui (; Hawaiian language, Hawaiian: ) is the second largest island in the Hawaiian archipelago, at 727.2 square miles (1,883 km2). It is the List of islands of the United States by area, 17th-largest in the United States. Maui is one of ...

, Moloka╩╗i and O╩╗ahu. Kamehameha I

Kamehameha I (; Kalani Pai╩╗ea Wohi o Kaleikini Keali╩╗ikui Kamehameha o ╩╗Iolani i Kaiwikapu kau╩╗i Ka Liholiho K┼źnui─ükea; to May 8 or 14, 1819), also known as Kamehameha the Great, was the conqueror and first ruler of the Kingdom of Hawaii ...

had conquered Maui and Moloka╩╗i five years prior in the Battle of Kepaniwai. They were abandoned when the Big Island became at risk and later reconquered by the aged King Kahekili II of Maui. His domain then comprised six of the major islands of the Hawaiian chain. With Kaumuali╩╗i's peaceful surrender, Kaua╩╗i and Ni╩╗ihau joined the kingdom. Kamehameha II

Kamehameha II (November 1797 ÔÇô July 14, 1824) was the second king of the Hawaiian Kingdom, Kingdom of Hawaii from 1819 to 1824. His birth name was Liholiho and full name was Kalaninui kua Liholiho i ke kapu ╩╗Iolani. It was lengthened to Kala ...

assumed de facto control of Kaua╩╗i and Ni╩╗ihau when he kidnapped Kaumuali╩╗i, ending his vassal rule over the islands.

In 1822, Queen Ka╩╗ahumanu and her husband King Kaumuali╩╗i traveled with Captain William Sumner to find N─źhoa, as her generation had only known of it through songs and myths

Myth is a genre of folklore consisting primarily of narratives that play a fundamental role in a society. For scholars, this is very different from the vernacular usage of the term "myth" that refers to a belief that is not true. Instead, the ...

. King Kamehameha IV

Kamehameha IV (Alekanetero ╩╗Iolani Kalanikualiholiho Maka o ╩╗Iouli K┼źnui─ükea o K┼źk─ü╩╗ilimoku; Anglicisation, anglicized as Alexander Liholiho) (February 9, 1834 ÔÇô November 30, 1863), reigned as the List of Hawaiian monarchs, fourth monar ...

later sailed there to officially annex the island. Kamehameha IV and Kal─ükaua would later claim other islands in the Hawaiian Archipelago, including Holoikauaua or Pearl and Hermes Atoll, Mokumanamana or Necker Island, Kau┼Ź or Laysan, PapaÔÇś─üpoho or Lisianski Island, H┼Źlanik┼ź or Kure Atoll, Kauihelani or Midway Atoll

Midway Atoll (colloquialism, colloquial: Midway Islands; ; ) is a atoll in the North Pacific Ocean. Midway Atoll is an insular area of the United States and is an Insular area#Unorganized unincorporated territories, unorganized and unincorpo ...

, K─ünemiloha╩╗i or French Frigate Shoals

The French Frigate Shoals (Hawaiian language, Hawaiian: K─ünemilohai) is the largest atoll in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, located about northwest of Honolulu, Hawaii, Honolulu. Its name commemorates France, French explorer Jean-Fran ...

, Naluk─ükala or Maro Reef and P┼źh─ühonu or Gardner Pinnacles, as well as Palmyra Atoll

Palmyra Atoll (), also referred to as Palmyra Island, is one of the Line Islands, Northern Line Islands (southeast of Kingman Reef and north of Kiribati). It is located almost due south of the Hawaiian Islands, roughly one-third of the way be ...

, Johnston Atoll

Johnston Atoll is an Unincorporated territories of the United States, unincorporated territory of the United States, under the jurisdiction of the United States Air Force (USAF). The island is closed to public entry, and limited access for mana ...

and Jarvis Island

Jarvis Island (; formerly known as Bunker Island or Bunker's Shoal) is an uninhabited coral island located in the South Pacific Ocean, about halfway between Hawaii and the Cook Islands. It is an Territories of the United States#Unincorporated u ...

. Several of these islands had been claimed by the United States under the Guano Islands Act of 1856. The Stewart Islands (Sikaiana

Sikaiana (formerly called the Stewart Islands) is a small atoll NE of Malaita in Solomon Islands in the south Pacific Ocean. It is almost in length and its lagoon, known as Te Moana, is totally enclosed by the coral reef. Its total land surfa ...

Atoll) near the Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands, also known simply as the Solomons,John Prados, ''Islands of Destiny'', Dutton Caliber, 2012, p,20 and passim is an island country consisting of six major islands and over 1000 smaller islands in Melanesia, part of Oceania, t ...

, were ceded to Hawai╩╗i in 1856 by its residents, but the cession was never formalized.

Royal estates

Early in its history, the Hawaiian Kingdom was governed from coastal towns on the islands of Hawai╩╗i and Maui ( L─ühain─ü). During the reign of Kamehameha III, a capital was established in Honolulu. Kamehameha V decided to build a royal palace fitting the Hawaiian Kingdom's new-found prosperity and standing with the royals of other nations. He commissioned the building of the palace at Ali╩╗i┼Źlani Hale. He died before it was completed. Later, the Supreme Court of the State of Hawai╩╗i occupied the building. David Kal─ükaua shared the dream of Kamehameha V to build a palace, and desired the trappings of European royalty. He commissioned the construction of╩╗Iolani Palace

The Iolani Palace () was the royal residence of the rulers of the Kingdom of Hawai╩╗i beginning with Kamehameha III under the Kamehameha Dynasty (1845) and ending with Queen Lili╩╗uokalani (1893) under the Kal─ükaua Dynasty. It is located i ...

. In later years, the palace served as his sister's makeshift prison, the site of the official raising of the U.S. flag during annexation, and then territorial governor's and legislature's offices, ultimately becoming a museum.

Palaces and royal grounds

Many Hawaiian royal residences remain extant.See also

* Cabinet of the Hawaiian Kingdom * Church of Hawaii *Hawaiian sovereignty movement

The Hawaiian sovereignty movement () is a grassroots political and cultural campaign to reestablish an autonomous or independent nation or kingdom of Hawaii out of a desire for sovereignty, self-determination, and self-governance.

Some group ...

* HawaiiÔÇôTahiti relations

* Legal status of Hawaii

*List of bilateral treaties signed by the Hawaiian Kingdom

Many bilateral treaties were signed by the Hawaiian Kingdom.

Under Kamehameha III

* United States of America, December 23, 1826 (Treaty)

* United Kingdom, November 13, 1836 (Lord E. Russell's Treaty)

* France, July 17, 1839 (Captain LaPlace's Con ...

*List of missionaries to Hawaii

This is a list of missionaries to Hawaii. Before European exploration, the Hawaiian religion was brought from Tahiti by Pa╩╗ao according to oral tradition. Notable missionaries with written records below are generally Christians, Christian.

Pr ...

* Privy Council of the Hawaiian Kingdom

*Supreme Court of Hawaii

The Supreme Court of Hawaii is the highest court of the State of Hawaii in the United States. Its decisions are binding on all other courts of the Hawaii State Judiciary. The principal purpose of the Supreme Court is to review the decisions ...

* United States federal recognition of Native Hawaiians

* Coat of Arms of the Hawaiian Kingdom

* Kamoamoa

References

Bibliography

*Further reading

* * * * * * ** ** ** * * * * * *External links

* * (Part 1) * (Part 2)Kingdom of Hawaii

at DCStamps {{DEFAULTSORT:Hawaiian Kingdom Pre-statehood history of Hawaii Former countries of the United States Former monarchies of Oceania States and territories established in 1795 States and territories disestablished in 1893 Former kingdoms Christian states Island countries 1795 establishments in Hawaii 1893 disestablishments in Hawaii Kingdom Former regions and territories of the United States Former monarchies