Kenneth Bainbridge on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

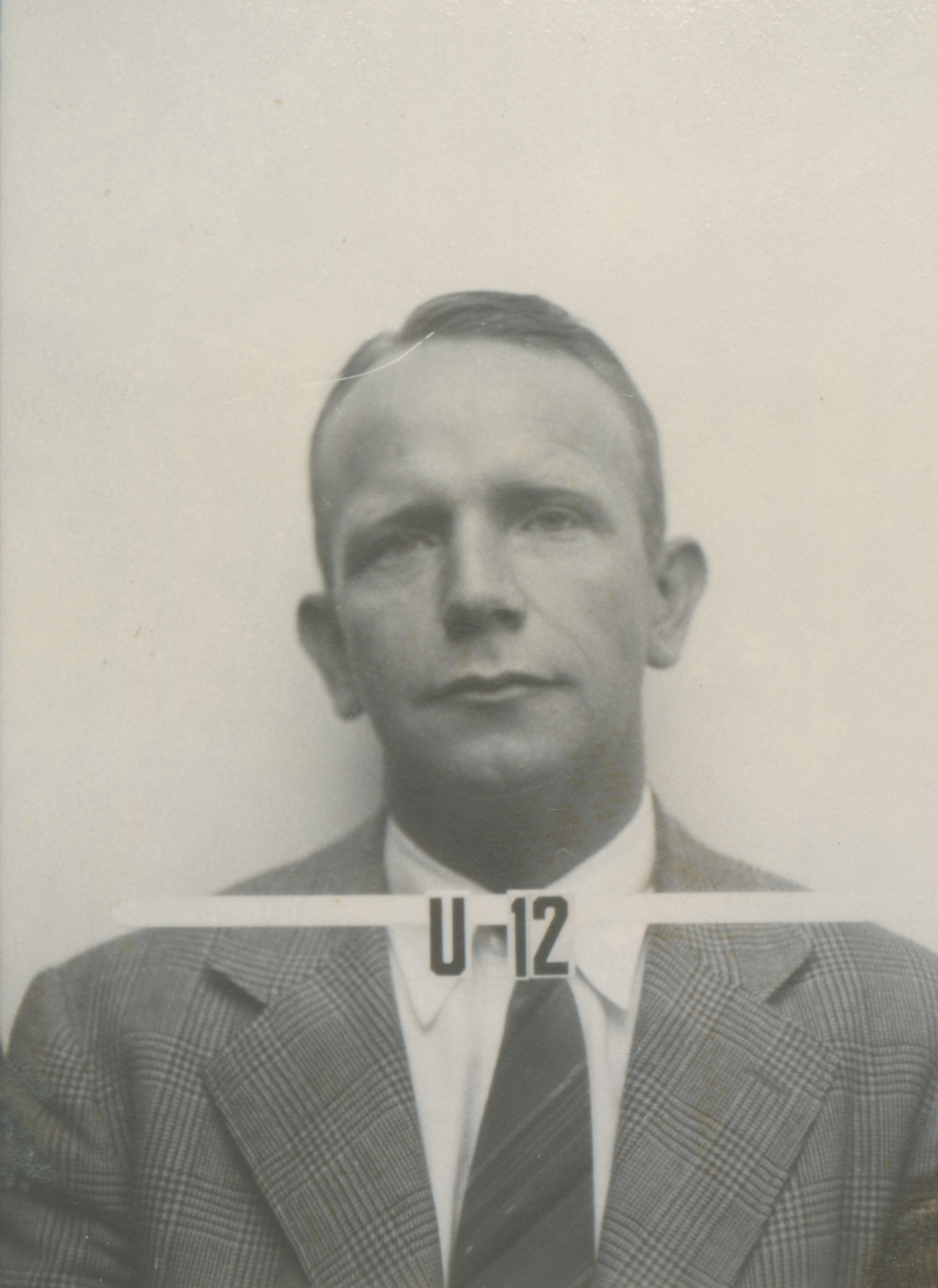

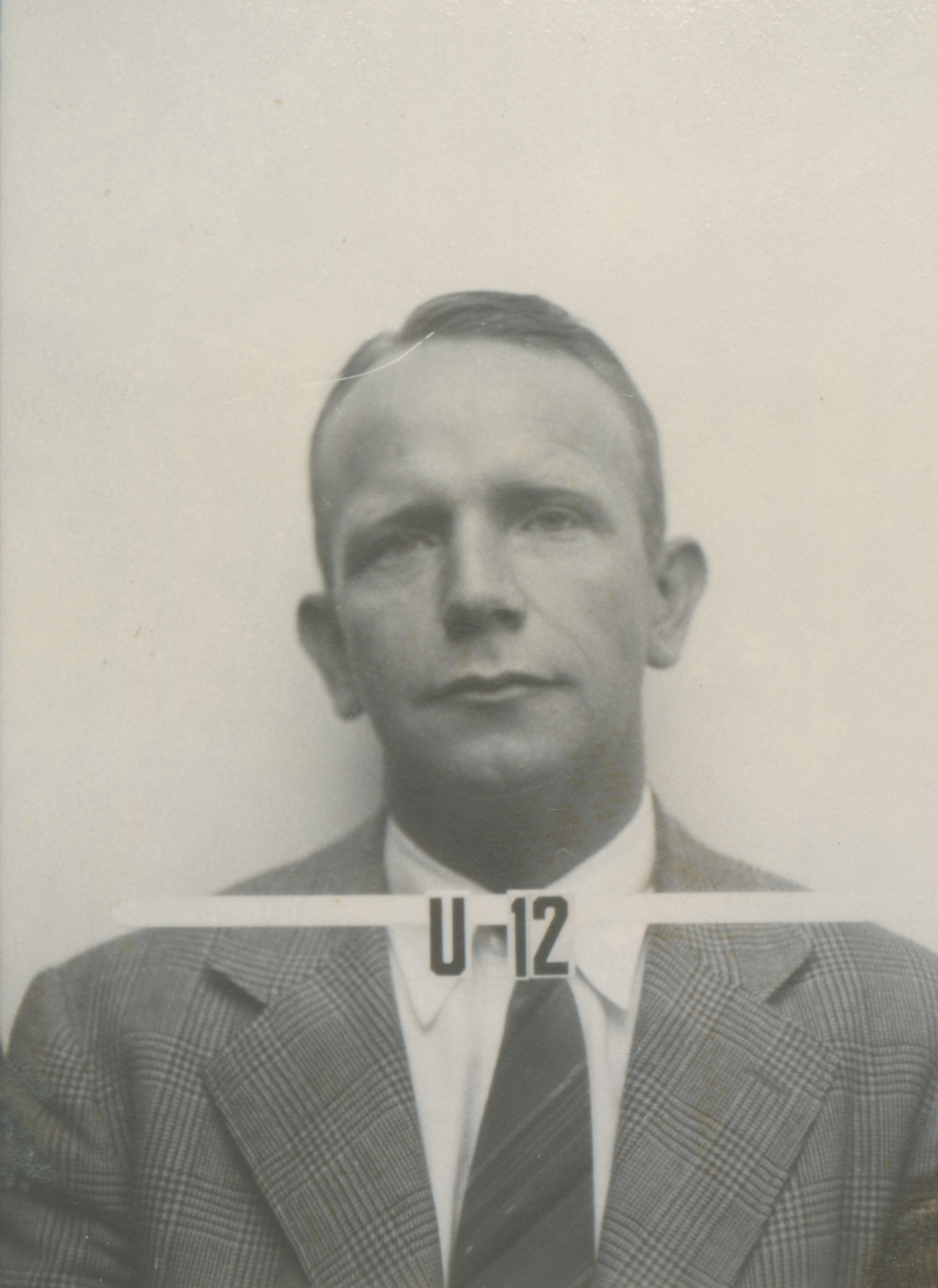

Kenneth Tompkins Bainbridge (July 27, 1904 – July 14, 1996) was an American physicist at

https://id.lib.harvard.edu/ead/hua23003/catalog Accessed May 8, 2024. He was educated at

In September 1940, with

In September 1940, with

Oral History interview transcript for Kenneth Bainbridge on 16 March 1977, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library and Archives - Session IOral History interview transcript for Kenneth Bainbridge on 23 March 1977, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library and Archives - Session II

{{DEFAULTSORT:Bainbridge, Kenneth 1904 births 1996 deaths American nuclear physicists Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Harvard University faculty Horace Mann School alumni Manhattan Project people Mass spectrometrists MIT School of Engineering alumni People from Cooperstown, New York Princeton University alumni Articles containing video clips Scientists from New York (state) Fellows of the American Physical Society

Harvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

who worked on cyclotron

A cyclotron is a type of particle accelerator invented by Ernest Lawrence in 1929–1930 at the University of California, Berkeley, and patented in 1932. Lawrence, Ernest O. ''Method and apparatus for the acceleration of ions'', filed: Januar ...

research. His accurate measurements of mass differences between nuclear isotopes allowed him to confirm Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein (14 March 187918 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist who is best known for developing the theory of relativity. Einstein also made important contributions to quantum mechanics. His mass–energy equivalence f ...

's mass–energy equivalence

In physics, mass–energy equivalence is the relationship between mass and energy in a system's rest frame. The two differ only by a multiplicative constant and the units of measurement. The principle is described by the physicist Albert Einstei ...

concept. He was the Director of the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program undertaken during World War II to produce the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada.

From 1942 to 1946, the ...

's Trinity nuclear test, which took place July 16, 1945. Bainbridge described the Trinity explosion as a "foul and awesome display". He remarked to J. Robert Oppenheimer

J. Robert Oppenheimer (born Julius Robert Oppenheimer ; April 22, 1904 – February 18, 1967) was an American theoretical physics, theoretical physicist who served as the director of the Manhattan Project's Los Alamos Laboratory during World ...

immediately after the test, "Now we are all sons of bitches." This marked the beginning of his dedication to ending the testing of nuclear weapons and to efforts to maintain civilian control of future developments in that field.

Early life

Kenneth Tompkins Bainbridge was born inCooperstown, New York

Cooperstown is a village in and the county seat of Otsego County, New York, United States. Most of the village lies within the town of Otsego, but some of the eastern part is in the town of Middlefield. Located at the foot of Otsego Lake in ...

, on July 27, 1904. He had one older brother and one younger brother.Papers of Kenneth T. Bainbridge, 1873, 1923-1996, HUGFP 152. Harvard University Archives. Horace Mann School

Horace Mann School (also known as Horace Mann or HM) is an American private, independent college-preparatory school in the Bronx, founded in 1887. Horace Mann is a member of the Ivy Preparatory School League, educating students from the New Yo ...

in New York. While at high school he developed an interest in ham radio

Amateur radio, also known as ham radio, is the use of the radio frequency spectrum for purposes of non-commercial exchange of messages, wireless experimentation, self-training, private recreation, radiosport, contesting, and emergency communi ...

which inspired him to enter Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a Private university, private research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Established in 1861, MIT has played a significant role in the development of many areas of moder ...

(MIT) in 1921 to study electrical engineering

Electrical engineering is an engineering discipline concerned with the study, design, and application of equipment, devices, and systems that use electricity, electronics, and electromagnetism. It emerged as an identifiable occupation in the l ...

. In five years he earned both Bachelor of Science

A Bachelor of Science (BS, BSc, B.S., B.Sc., SB, or ScB; from the Latin ') is a bachelor's degree that is awarded for programs that generally last three to five years.

The first university to admit a student to the degree of Bachelor of Scienc ...

(S.B.) and Master of Science

A Master of Science (; abbreviated MS, M.S., MSc, M.Sc., SM, S.M., ScM or Sc.M.) is a master's degree. In contrast to the Master of Arts degree, the Master of Science degree is typically granted for studies in sciences, engineering and medici ...

(S.M.) degrees. During the summer breaks he worked at General Electric

General Electric Company (GE) was an American Multinational corporation, multinational Conglomerate (company), conglomerate founded in 1892, incorporated in the New York (state), state of New York and headquartered in Boston.

Over the year ...

's laboratories in Lynn, Massachusetts

Lynn is the eighth-largest List of municipalities in Massachusetts, municipality in Massachusetts, United States, and the largest city in Essex County, Massachusetts, Essex County. Situated on the Atlantic Ocean, north of the Boston city line ...

and Schenectady, New York

Schenectady ( ) is a City (New York), city in Schenectady County, New York, United States, of which it is the county seat. As of the United States Census 2020, 2020 census, the city's population of 67,047 made it the state's ninth-most populo ...

. While there he obtained three patents related to photoelectric tubes.

Normally this would have been a promising start to a career at General Electric, but it made Bainbridge aware of how interested he was in physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

. Upon graduating from MIT in 1926, he enrolled at Princeton University

Princeton University is a private university, private Ivy League research university in Princeton, New Jersey, United States. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth, New Jersey, Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the List of Colonial ...

, where Karl T. Compton, a consultant to General Electric, was on the faculty. While at Princeton, Bainbridge created his first mass spectrograph, came up with methods for identifying elements, and started studying nuclei. In 1929, he was awarded a Ph.D. in his new field, writing his thesis on "A search for element 87 by analysis of positive rays" under the supervision of Henry DeWolf Smyth.

Early career

Bainbridge enjoyed a series of prestigious fellowships after graduation. He was awarded a National Research Council, and then a Bartol Research Foundation fellowship. At the time theFranklin Institute

The Franklin Institute is a science museum and a center of science education and research in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It is named after the American scientist and wikt:statesman, statesman Benjamin Franklin. It houses the Benjamin Franklin ...

's Bartol Research Foundation was located on the Swarthmore College

Swarthmore College ( , ) is a Private college, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Swarthmore, Pennsylvania, United States. Founded in 1864, with its first classes held in 1869, Swarthmore is one of the e ...

campus in Pennsylvania, and was directed by W. F. G. Swann, an English physicist with an interest in nuclear physics

Nuclear physics is the field of physics that studies atomic nuclei and their constituents and interactions, in addition to the study of other forms of nuclear matter.

Nuclear physics should not be confused with atomic physics, which studies th ...

. Bainbridge spent four years (1929-1933) at the Franklin Institute’s Bartol laboratories and during his time there Bainbridge learned how to take subtle and difficult mass measurements. Bainbridge married Margaret ("Peg") Pitkin, a member of the Swarthmore teaching faculty, in September 1931. They had a son, Martin Keeler, and two daughters, Joan and Margaret Tomkins.

In 1932, Bainbridge developed a mass spectrometer

Mass spectrometry (MS) is an analytical technique that is used to measure the mass-to-charge ratio of ions. The results are presented as a '' mass spectrum'', a plot of intensity as a function of the mass-to-charge ratio. Mass spectrometry is us ...

with a resolving power of 600 and a relative precision of one part in 10,000. He used this instrument to verify Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein (14 March 187918 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist who is best known for developing the theory of relativity. Einstein also made important contributions to quantum mechanics. His mass–energy equivalence f ...

's mass–energy equivalence

In physics, mass–energy equivalence is the relationship between mass and energy in a system's rest frame. The two differ only by a multiplicative constant and the units of measurement. The principle is described by the physicist Albert Einstei ...

, E = mc2. Since Bainbridge was the first to successfully test Einstein’s theory of the equivalence of mass and energy, he was awarded the Louis Edward Levy Medal. Francis William Aston wrote that:

In 1933, Bainbridge was awarded a prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship

Guggenheim Fellowships are Grant (money), grants that have been awarded annually since by the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, endowed by the late Simon Guggenheim, Simon and Olga Hirsh Guggenheim. These awards are bestowed upon indiv ...

, which he used to travel to England and work at Ernest Rutherford

Ernest Rutherford, 1st Baron Rutherford of Nelson (30 August 1871 – 19 October 1937) was a New Zealand physicist who was a pioneering researcher in both Atomic physics, atomic and nuclear physics. He has been described as "the father of nu ...

's Cavendish Laboratory

The Cavendish Laboratory is the Department of Physics at the University of Cambridge, and is part of the School of Physical Sciences. The laboratory was opened in 1874 on the New Museums Site as a laboratory for experimental physics and is named ...

at Cambridge University

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

. While there he continued his work developing the mass spectrograph, and became friends with the British physicist John Cockcroft

Sir John Douglas Cockcroft (27 May 1897 – 18 September 1967) was an English nuclear physicist who shared the 1951 Nobel Prize in Physics with Ernest Walton for their splitting of the atomic nucleus, which was instrumental in the developmen ...

. Also, during Bainbridge’s time in Cambridge, he produced very advanced mass spectrographs and ended up becoming a leading expert in the field of mass spectroscopy. It was at Cambridge when Bainbridge first began to work with nuclear chain reactions.

When his Guggenheim fellowship expired in September 1934, he returned to the United States, where he accepted an associate professorship at Harvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

. He started by building a new mass spectrograph that he had designed with at the Cavendish Laboratory. Working with J. Curry Street, he commenced work on a cyclotron

A cyclotron is a type of particle accelerator invented by Ernest Lawrence in 1929–1930 at the University of California, Berkeley, and patented in 1932. Lawrence, Ernest O. ''Method and apparatus for the acceleration of ions'', filed: Januar ...

. They had a design for a cyclotron provided by Ernest Lawrence

Ernest Orlando Lawrence (August 8, 1901 – August 27, 1958) was an American accelerator physicist who received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1939 for his invention of the cyclotron. He is known for his work on uranium-isotope separation for ...

, but decided to build a cyclotron instead.

Bainbridge was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (The Academy) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, and other ...

in 1937. His interest in mass spectroscopy led naturally to an interest in the relative abundance of isotopes

Isotopes are distinct nuclear species (or ''nuclides'') of the same chemical element. They have the same atomic number (number of protons in their nuclei) and position in the periodic table (and hence belong to the same chemical element), but ...

. The discovery of nuclear fission

Nuclear fission is a reaction in which the nucleus of an atom splits into two or more smaller nuclei. The fission process often produces gamma photons, and releases a very large amount of energy even by the energetic standards of radioactiv ...

in uranium-235

Uranium-235 ( or U-235) is an isotope of uranium making up about 0.72% of natural uranium. Unlike the predominant isotope uranium-238, it is fissile, i.e., it can sustain a nuclear chain reaction. It is the only fissile isotope that exists in nat ...

led to an interest in separating this isotope. He proposed using a Holweck pump to produce the vacuum necessary for this work, and enlisted George B. Kistiakowsky and E. Bright Wilson to help. There was little interest in their work because research was being carried out elsewhere. Bainbridge ended up bringing his Holweck pump to government authorities in Washington D.C., however the government authorities claimed that scientists working for the government were already working on a process of isotope separation and that he should discontinue his work using the Holweck pump for isotope separation

Isotope separation is the process of concentrating specific isotopes of a chemical element by removing other isotopes. The use of the nuclides produced is varied. The largest variety is used in research (e.g. in chemistry where atoms of "marker" n ...

. In 1943, their cyclotron was requisitioned by Edwin McMillan

Edwin Mattison McMillan (September 18, 1907 – September 7, 1991) was an American physicist credited with being the first to produce a transuranium element, neptunium. For this, he shared the 1951 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Glenn Seaborg.

...

for use by the U. S. Army. It was packed up and carted off to Los Alamos, New Mexico

Los Alamos (, meaning ''The Poplars'') is a census-designated place in Los Alamos County, New Mexico, United States, that is recognized as one of the development and creation places of the Nuclear weapon, atomic bomb—the primary objective of ...

.

World War II

In September 1940, with

In September 1940, with World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

raging in Europe, the British Tizard Mission

The Tizard Mission, officially the British Technical and Scientific Mission, was a delegation from the United Kingdom that visited the United States during World War II to share secret research and development (R&D) work that had military applicat ...

brought a number of new technologies to the United States, including a cavity magnetron

The cavity magnetron is a high-power vacuum tube used in early radar systems and subsequently in microwave ovens and in linear particle accelerators. A cavity magnetron generates microwaves using the interaction of a stream of electrons wit ...

, a high-powered device that generates microwave

Microwave is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelengths shorter than other radio waves but longer than infrared waves. Its wavelength ranges from about one meter to one millimeter, corresponding to frequency, frequencies between 300&n ...

s using the interaction of a stream of electron

The electron (, or in nuclear reactions) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary charge, elementary electric charge. It is a fundamental particle that comprises the ordinary matter that makes up the universe, along with up qua ...

s with a magnetic field

A magnetic field (sometimes called B-field) is a physical field that describes the magnetic influence on moving electric charges, electric currents, and magnetic materials. A moving charge in a magnetic field experiences a force perpendicular ...

. This device, which promised to revolutionize radar

Radar is a system that uses radio waves to determine the distance ('' ranging''), direction ( azimuth and elevation angles), and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It is a radiodetermination method used to detect and track ...

, demolished any thoughts the Americans had entertained about their technological leadership. Alfred Lee Loomis of the National Defense Research Committee

The National Defense Research Committee (NDRC) was an organization created "to coordinate, supervise, and conduct scientific research on the problems underlying the development, production, and use of mechanisms and devices of warfare" in the U ...

established the Radiation Laboratory

The Radiation Laboratory, commonly called the Rad Lab, was a microwave and radar research laboratory located at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, Massachusetts. It was first created in October 1940 and operated until 3 ...

at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a Private university, private research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Established in 1861, MIT has played a significant role in the development of many areas of moder ...

to develop this radar technology. In October, Bainbridge became one of the first scientists to be recruited for the Radiation Laboratory by Ernest Lawrence. Bainbridge spent two and a half years at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Radiation laboratory working on radar development. The scientists divided up the work between them; Bainbridge drew pulse modulators. Working with the Navy, he helped develop high-powered radars for warships. Then from March 1941 to May 1941, Bainbridge was sent to England to discuss radar development with the English. While he was in England, he was able to see firsthand the various radar equipment that the British had installed being used in combat. Also, while in England Bainbridge met with British scientists and learned about the British’s efforts in developing an atomic bomb. When Bainbridge returned to the United States, he reported to the United States about the British's plans to build an atomic bomb. Bainbridge then continued to work on the development of radar technology at M.I.T.. Bainbridge eventually became the lead of a division of the lab that was responsible for ship-borne interception control radar, ground systems search and warning class radar, ground-based fire control radar, microwave early warning radar, search and fighter control radar, and fire control radar. Many of these radar technologies would find their way onto aircraft carriers

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and hangar facilities for supporting, arming, deploying and recovering shipborne aircraft. Typically it is the capital ship of a fl ...

fighting the Japanese in the Pacific as the war went on.

In May 1943, Bainbridge joined Robert Oppenheimer

J. Robert Oppenheimer (born Julius Robert Oppenheimer ; April 22, 1904 – February 18, 1967) was an American theoretical physicist who served as the director of the Manhattan Project's Los Alamos Laboratory during World War II. He is often ...

's Project Y at Los Alamos. He initially led E-2, the instrumentation group, which developed X-ray instrumentation for examining explosions. In March 1944, he became head of a new group, E-9, which was charged with conducting the first nuclear test. In Oppenheimer's sweeping reorganization of the Los Alamos laboratory in August 1944, the E-9 Group became X-2. He also worked on developing designs for the uranium Little Boy

Little Boy was a type of atomic bomb created by the Manhattan Project during World War II. The name is also often used to describe the specific bomb (L-11) used in the bombing of the Japanese city of Hiroshima by the Boeing B-29 Superfortress ...

design dropped on Hiroshima

is the capital of Hiroshima Prefecture in Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 1,199,391. The gross domestic product (GDP) in Greater Hiroshima, Hiroshima Urban Employment Area, was US$61.3 billion as of 2010. Kazumi Matsui has b ...

and the plutonium Fat Man

"Fat Man" (also known as Mark III) was the design of the nuclear weapon the United States used for seven of the first eight nuclear weapons ever detonated in history. It is also the most powerful design to ever be used in warfare.

A Fat Man ...

design used on Nagasaki

, officially , is the capital and the largest Cities of Japan, city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

Founded by the Portuguese, the port of Portuguese_Nagasaki, Nagasaki became the sole Nanban trade, port used for tr ...

. Additionally, Bainbridge also helped in the development of methods to determine the trajectories of the atomic bombs.

In March 1945, Bainbridge was given the position of director of the Trinity Test. Bainbridge was tasked with finding a site that was flat in order to be able to take accurate measurements of the explosion. The site also had to be unnoticeable for security reasons, but decently close to Los Alamos. Bainbridge ended up finding a site that was approximately 200 miles away from Los Alamos, located in the Alamogordo Gunnery Range. Bainbridge along with his assistant director, John Williams who was also a physicist planned and oversaw the construction of the needed facilities at the test site. The facilities consisted of observation bunkers, hundreds of miles of wiring, miles of paved roads, as well as housing. Additionally, Bainbridge played a role in the development of bomb detonator equipment and setting up equipment for measuring the yield of the explosion. On July 16, 1945, Bainbridge and his colleagues conducted the Trinity nuclear test. "My personal nightmare", he later wrote, "was knowing that if the bomb didn't go off or hangfired, I, as head of the test, would have to go to the tower first and seek to find out what had gone wrong." To his relief, the explosion of the first atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear weapon), producing a nuclear expl ...

went off without such drama, in what he later described as "a foul and awesome display". He turned to Oppenheimer and said, "Now we are all sons of bitches." After the conclusion of the Trinity test Bainbridge co-wrote the official account of the Trinity test that was given to the United States government.

Bainbridge was relieved that the Trinity test had been a success, relating in a 1975 ''Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

The ''Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists'' is a nonprofit organization concerning science and global security issues resulting from accelerating technological advances that have negative consequences for humanity. The ''Bulletin'' publishes conte ...

'' article, "I had a feeling of exhilaration that the 'gadget' had gone off properly followed by one of deep relief. I wouldn't have to go to the tower to see what had gone wrong."

For his work on the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program undertaken during World War II to produce the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada.

From 1942 to 1946, the ...

, Bainbridge received two letters of commendation from the project's director, Major General Leslie R. Groves, Jr. He also received a Presidential Certificate of Merit for his work at the MIT Radiation Laboratory.

Postwar

Bainbridge returned to Harvard after the war, and initiated the construction of a synchro-cyclotron, which has since been dismantled. Also, upon arriving back at Harvard, Bainbridge created a larger mass spectrograph. Utilizing his new device, Bainbridge was able to establish the existence of theneutrino

A neutrino ( ; denoted by the Greek letter ) is an elementary particle that interacts via the weak interaction and gravity. The neutrino is so named because it is electrically neutral and because its rest mass is so small ('' -ino'') that i ...

, which is a basic component of matter

In classical physics and general chemistry, matter is any substance that has mass and takes up space by having volume. All everyday objects that can be touched are ultimately composed of atoms, which are made up of interacting subatomic pa ...

that had eluded scientists for some time. From 1950 to 1954, he chaired the physics department at Harvard. During those years, he drew the ire of Senator Joseph McCarthy

Joseph Raymond McCarthy (November 14, 1908 – May 2, 1957) was an American politician who served as a Republican Party (United States), Republican United States Senate, U.S. Senator from the state of Wisconsin from 1947 until his death at age ...

for his aggressive defense of his colleagues in academia. As chairman, he was responsible for the renovation of the old Jefferson Physical Laboratory, and he established the Morris Loeb Lectures in Physics. He also devoted a good deal of his time to improving the laboratory facilities for graduate students. During Bainbridge’s remaining years at Harvard, he continued to work towards finding new mechanisms to obtain precise yields of atomic mass

Atomic mass ( or ) is the mass of a single atom. The atomic mass mostly comes from the combined mass of the protons and neutrons in the nucleus, with minor contributions from the electrons and nuclear binding energy. The atomic mass of atoms, ...

es.

Throughout the 1950s, Bainbridge remained an outspoken proponent of civilian control of nuclear power

Nuclear power is the use of nuclear reactions to produce electricity. Nuclear power can be obtained from nuclear fission, nuclear decay and nuclear fusion reactions. Presently, the vast majority of electricity from nuclear power is produced by ...

and the abandonment of nuclear testing

Nuclear weapons tests are experiments carried out to determine the performance of nuclear weapons and the effects of Nuclear explosion, their explosion. Nuclear testing is a sensitive political issue. Governments have often performed tests to si ...

. In 1950 he was one of twelve prominent scientists who petitioned President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. As the 34th vice president in 1945, he assumed the presidency upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt that year. Subsequen ...

to declare that the United States would never be the first to use the hydrogen bomb

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H-bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a lo ...

. Bainbridge retired from Harvard in 1975.

Bainbridge's wife Margaret died suddenly in January 1967 from a blood clot in a broken wrist. He married Helen Brinkley King, an editor at William Morrow in New York City, in October 1969. She died in February 1989. A scholarship was established at Sarah Lawrence College

Sarah Lawrence College (SLC) is a Private university, private liberal arts college in Yonkers, New York, United States. Founded as a Women's colleges in the United States, women's college in 1926, Sarah Lawrence College has been coeducational ...

in her memory. He died at his home in Lexington, Massachusetts

Lexington is a suburban town in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States, located 10 miles (16 km) from Downtown Boston. The population was 34,454 as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. The area was originally inhabited by ...

, on July 14, 1996. He was survived by his daughters from his first marriage, Joan Bainbridge Safford and Margaret Bainbridge Robinson. He was buried in the Abel's Hill Cemetery on Martha's Vineyard

Martha's Vineyard, often simply called the Vineyard, is an island in the U.S. state of Massachusetts, lying just south of Cape Cod. It is known for being a popular, affluent summer colony, and includes the smaller peninsula Chappaquiddick Isla ...

, in a plot with his first wife Margaret and his son Martin. His papers are in the Harvard University Archives.

In popular culture

In the 2023 film ''Oppenheimer'', he is portrayed byJosh Peck

Joshua Michael Peck (born November 10, 1986) is an American actor, comedian, and YouTuber. Peck began his career as a child actor, appearing in the film Snow Day (2000 film), ''Snow Day'' (2000) and the Nickelodeon sketch comedy series ''The Ama ...

.

See also

* Bainbridge mass spectrometerNotes

References

* * * *External links

Oral History interview transcript for Kenneth Bainbridge on 16 March 1977, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library and Archives - Session I

{{DEFAULTSORT:Bainbridge, Kenneth 1904 births 1996 deaths American nuclear physicists Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Harvard University faculty Horace Mann School alumni Manhattan Project people Mass spectrometrists MIT School of Engineering alumni People from Cooperstown, New York Princeton University alumni Articles containing video clips Scientists from New York (state) Fellows of the American Physical Society