John Wolryche on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Wolryche (c.1637–1685) was a lawyer and politician of

Wolryche, John (c.1637–85), of Dudmaston Hall, Quatt, Salop.

– Authors: J. S. Crossette / John. P. Ferris * Thomas Wolryche of

Wolryche (Woolridge), Thomas (1598–1668), of Dudmaston, Salop.

– Author: Simon Healy. Initially a client of his uncle,

While he was still completing his Cambridge degree, Wolryche's name was entered on the admission register at

While he was still completing his Cambridge degree, Wolryche's name was entered on the admission register at

''Much Wenlock''

– Author: J. S. Crossette Now Wolryche stood on

''Forester, William (1655–1718), of Dothill Park, Salop.''

– Author: J. S. Crossette He was once again named a member of the elections and privileges committee.

''Complete Baronetage, Volume II, 1625–1649''

Exeter: William Pollard. Accessed 10 June 2014 at Internet Archive. *C R J Currie (Editor), A P Baggs, G C Baugh, D C Cox, Jessie McFall, P A Stamper (1998).

''A History of the County of Shropshire: Volume 10 – Munslow Hundred (part), The Liberty and Borough of Wenlock''

Institute of Historical Research. Accessed 11 June 2014. *Reginald J. Fletcher (1901)

''The Pension Book of Gray's Inn 1569–1669''

Printed at the Chiswick press and published by order of the Masters of the bench. Accessed at Internet Archive, 10 June 2014. *Reginald J. Fletcher (1910)

''The Pension Book of Gray's Inn 1669–1800''

Printed at the Chiswick press and published by order of the Masters of the bench. Accessed at Internet Archive, 10 June 2014. * Joseph Foster (188

''The Register of Admissions to Gray's Inn 1521–1889''

Hansard. Accessed at Internet Archive, 10 June 2014. * *Oliver Garnett (2005). ''Dudmaston'', The National Trust, . * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Wolryche, John 1637 births 1685 deaths Alumni of Christ's College, Cambridge Members of Gray's Inn Lawyers from Shropshire English MPs 1680–1681 English MPs 1681 English landowners Younger sons of baronets Politicians from Shropshire

landed gentry

The landed gentry, or the ''gentry'', is a largely historical British social class of landowners who could live entirely from rental income, or at least had a country estate. While distinct from, and socially below, the British peerage, th ...

background who represented Much Wenlock

Much Wenlock is a market town and parish in Shropshire, England, situated on the A458 road between Shrewsbury and Bridgnorth. Nearby, to the northeast, is the Ironbridge Gorge, and the new town of Telford. The civil parish includes the villag ...

in the House of Commons of England

The House of Commons of England was the lower house of the Parliament of England (which incorporated Wales) from its development in the 14th century to the union of England and Scotland in 1707, when it was replaced by the House of Commons of ...

in two parliaments of Charles II. He was a moderate Whig, opposing the succession of James II but avoiding involvement in conspiracies.

Background and education

John Wolryche was the 5th son, but 3rd surviving son, ofHenningWolryche, John (c.1637–85), of Dudmaston Hall, Quatt, Salop.

– Authors: J. S. Crossette / John. P. Ferris * Thomas Wolryche of

Dudmaston Hall

Dudmaston Hall is a 17th-century country house in the care of the National Trust in the Severn Valley, Shropshire, England.

Dudmaston Hall is located near the village of Quatt, a few miles south of the market town of Bridgnorth, just off the ...

, near Bridgnorth

Bridgnorth is a town in Shropshire, England. The River Severn splits it into High Town and Low Town, the upper town on the right bank and the lower on the left bank of the River Severn. The population at the 2011 Census was 12,079.

History

B ...

, a substantial landowner in south and east Shropshire

Shropshire (; alternatively Salop; abbreviated in print only as Shrops; demonym Salopian ) is a landlocked historic county in the West Midlands region of England. It is bordered by Wales to the west and the English counties of Cheshire to th ...

.Thrush and FerrisWolryche (Woolridge), Thomas (1598–1668), of Dudmaston, Salop.

– Author: Simon Healy. Initially a client of his uncle,

Edward Bromley

Sir Edward Bromley (1563–2 June 1626) was an English lawyer, judge, landowner and politician of the Elizabethan and Jacobean periods. A member of a Shropshire legal and landed gentry dynasty, he was prominent at the Inner Temple and became ...

, Wolryche had been MP for Much Wenlock. He became an ardent royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of governme ...

in the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

and was military governor of Bridgnorth, before being sequestered and forced to compound

Compound may refer to:

Architecture and built environments

* Compound (enclosure), a cluster of buildings having a shared purpose, usually inside a fence or wall

** Compound (fortification), a version of the above fortified with defensive struct ...

for £730.

*Ursula Ottley, daughter of Thomas Ottley of Pitchford, Shropshire. She was a sister of Francis Ottley, a key leader in the royalist seizure of power in Shropshire and military governor of Shrewsbury

Shrewsbury ( , also ) is a market town, civil parish, and the county town of Shropshire, England, on the River Severn, north-west of London; at the 2021 census, it had a population of 76,782. The town's name can be pronounced as either 'Sh ...

John Wolryche was educated initially at the grammar school

A grammar school is one of several different types of school in the history of education in the United Kingdom and other English-speaking countries, originally a school teaching Latin, but more recently an academically oriented secondary school ...

in Stone, Staffordshire

Stone is a canal town and civil parish in Staffordshire, England, north of Stafford, south of Stoke-on-Trent and north of Rugeley. It was an urban district council and a rural district council before becoming part of the Borough of Staffor ...

. He was admitted as a pensioner

A pensioner is a person who receives a pension, most commonly because of retirement from the workforce. This is a term typically used in the United Kingdom (along with OAP, initialism of old-age pensioner), Ireland and Australia where someone of p ...

, i.e. a fee-paying student, at Christ's College, Cambridge

Christ's College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. The college includes the Master, the Fellows of the College, and about 450 undergraduate and 170 graduate students. The college was founded by William Byngham in 1437 as ...

, aged 16, on 19 May 1653 – a fair guide to his birth date. He matriculated

Matriculation is the formal process of entering a university, or of becoming eligible to enter by fulfilling certain academic requirements such as a matriculation examination.

Australia

In Australia, the term "matriculation" is seldom used now. ...

in the same year and went on to graduate BA in 1656-7.

Legal training and career

While he was still completing his Cambridge degree, Wolryche's name was entered on the admission register at

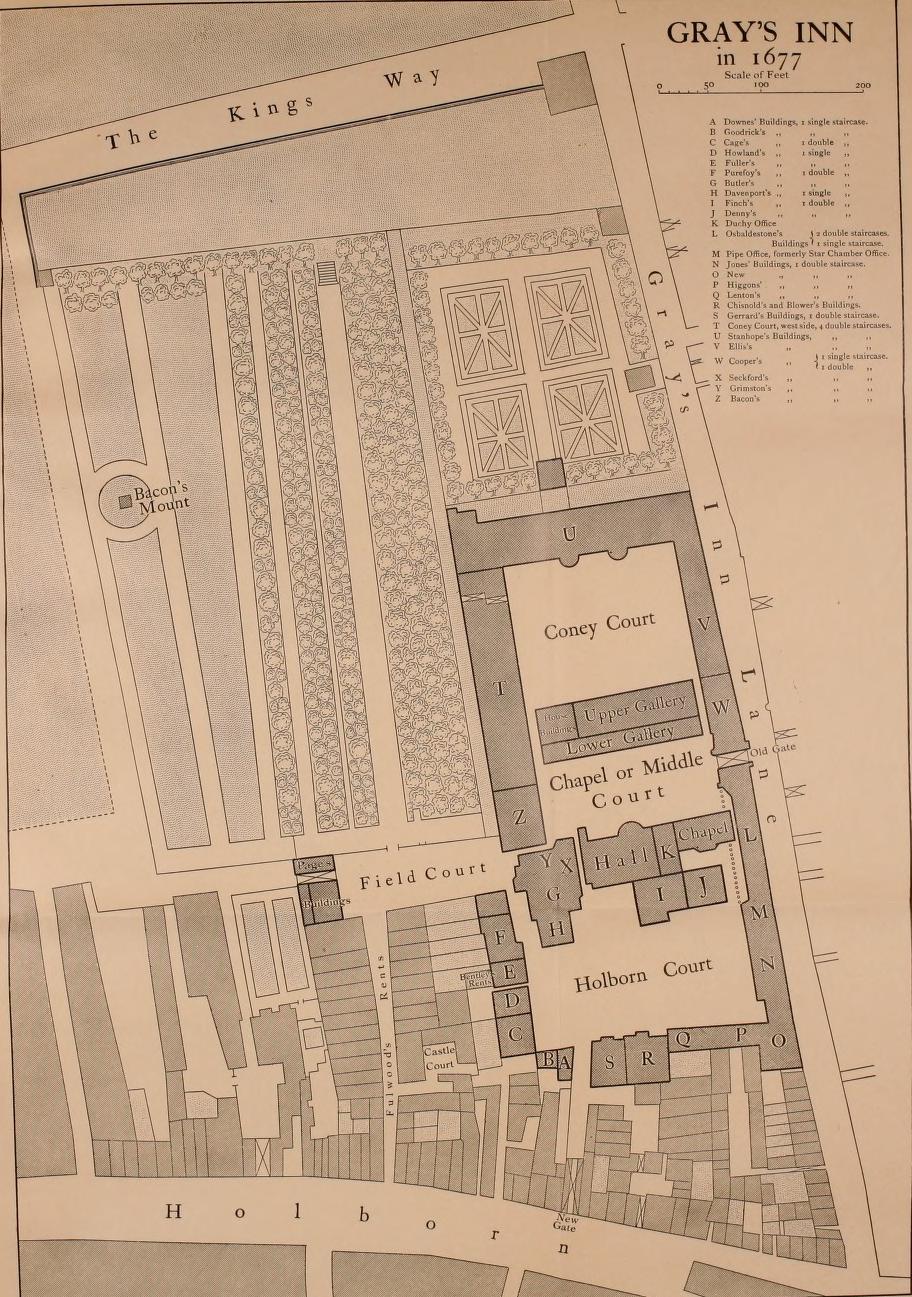

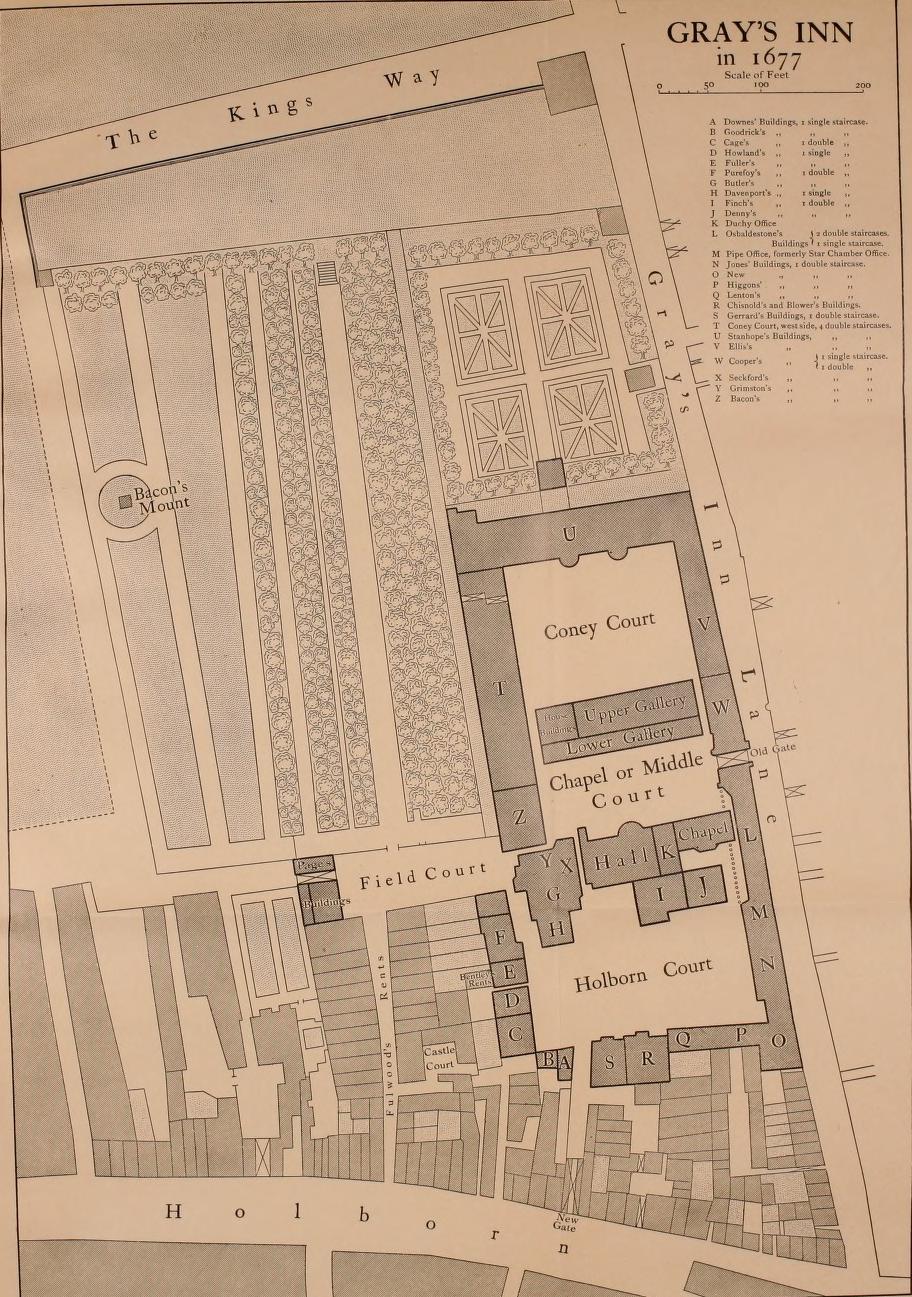

While he was still completing his Cambridge degree, Wolryche's name was entered on the admission register at Gray's Inn

The Honourable Society of Gray's Inn, commonly known as Gray's Inn, is one of the four Inns of Court (professional associations for barristers and judges) in London. To be called to the bar in order to practise as a barrister in England and Wale ...

on 6 December 1655. This was an unusual choice for his family: his father, Edward Bromley, Francis Ottley and many other relatives were members of the Inner Temple

The Honourable Society of the Inner Temple, commonly known as the Inner Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court and is a professional associations for barristers and judges. To be called to the Bar and practise as a barrister in England and Wal ...

. Unlike Sir Thomas, John Wolryche was not expecting to become a major landowner and took his legal studies seriously.

On 25 November 1661, the Pension or governing council ordered that Wolryche be called to the bar

The call to the bar is a legal term of art in most common law jurisdictions where persons must be qualified to be allowed to argue in court on behalf of another party and are then said to have been "called to the bar" or to have received "call to ...

, as part of a large batch of students, on condition that he deposit £4 as surety for performing his bar moot. He seems to have taken chambers at his Inn

Inns are generally establishments or buildings where travelers can seek lodging, and usually, food and drink. Inns are typically located in the country or along a highway; before the advent of motorized transportation they also provided accommo ...

: he was listed as occupying a room on the third storey of Cage's Buildings in 1668. In 1670 he received the degree of Doctor of Civil Law

Doctor of Civil Law (DCL; la, Legis Civilis Doctor or Juris Civilis Doctor) is a degree offered by some universities, such as the University of Oxford, instead of the more common Doctor of Laws (LLD) degrees.

At Oxford, the degree is a higher ...

from Oxford University

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

. In 1676 he was appointed recorder

Recorder or The Recorder may refer to:

Newspapers

* ''Indianapolis Recorder'', a weekly newspaper

* ''The Recorder'' (Massachusetts newspaper), a daily newspaper published in Greenfield, Massachusetts, US

* ''The Recorder'' (Port Pirie), a news ...

of Bridgnorth – a post he held until his death. On 26 November 1680 the Pension of Gray's Inn admitted him to the Grand Company of Ancients, its body of most learned and experienced members.

Landowner

Sir Thomas Wolryche had owned about 6,000 acres, centred on his seat of Dudmaston, atQuatt

Quatt is a small village in Shropshire, England in the Severn Valley. The civil parish, formally known as Quatt Malvern, has a population of 219 according to the 2001 census, reducing to 200 at the 2011 census.

It lies on the A442 south of Brid ...

, to the south of Bridgnorth. The estates were destined for his eldest son, Francis Wolryche, but he was considered incapable of managing them because of mental illness. Hence Sir Thomas settled them on John in trust. Sir Thomas died in 1668 and John Wolryche obtained a private act

Proposed bills are often categorized into public bills and private bills. A public bill is a proposed law which would apply to everyone within its jurisdiction. This is unlike a private bill which is a proposal for a law affecting only a single p ...

of Parliament in 1673 to confirm his position. Dudmaston was a substantial property, probably a fortified manor house

A manor house was historically the main residence of the lord of the manor. The house formed the administrative centre of a manor in the European feudal system; within its great hall were held the lord's manorial courts, communal meals w ...

, rated for taxation purposes as having 24 hearths in 1673. John Wolryche began building a new house near Quatt church in the 1680s but it was not completed in his lifetime and ultimately became the dower house

A dower house is usually a moderately large house available for use by the widow of the previous owner of an English, Scottish or Welsh estate. The widow, often known as the "dowager", usually moves into the dower house from the larger family h ...

.Garnett, p.25 The present hall was built for his son, Thomas, in the 1690s.

From 1668 Wolryche played a more significant role in the county, taking positions appropriate to his status as a prominent landowner. In 1669 he was made a freeman

Freeman, free men, or variant, may refer to:

* a member of the Third Estate in medieval society (commoners), see estates of the realm

* Freeman, an apprentice who has been granted freedom of the company, was a rank within Livery companies

* Free ...

of Bridgnorth. The following year he became a Justice of the Peace

A justice of the peace (JP) is a judicial officer of a lower or ''puisne'' court, elected or appointed by means of a commission ( letters patent) to keep the peace. In past centuries the term commissioner of the peace was often used with the sa ...

. He was a commissioner for assessment, a key post in imposing taxation locally, from 1673–80. Like his father, he became a captain of the militia, a post that led to his appointment as a Deputy Lieutenant of Shropshire in 1683.

Political career

Candidate at Bridgnorth

Wolryche first stood for Parliament on 21 February 1679 atBridgnorth

Bridgnorth is a town in Shropshire, England. The River Severn splits it into High Town and Low Town, the upper town on the right bank and the lower on the left bank of the River Severn. The population at the 2011 Census was 12,079.

History

B ...

, where he had been recorder, or chief legal official, a post which might have been expected to give him an advantage. However, in standing for election he was challenging the might of the Whitmores. Wolryche's father, Sir Thomas, had been a close friend and business partner of Sir Thomas Whitmore, 1st Baronet

Sir Thomas Whitmore, 1st Baronet (28 November 1612 – 1653) was an English politician who sat in the House of Commons of England between 1640 and 1644. He supported the Royalist side in the English Civil War.

Biography

Whitmore was the son o ...

: Whitmore resided at Bridgnorth Castle

Bridgnorth Castle is a castle in the town of Bridgnorth, Shropshire. It is a scheduled monument, first listed in 1928.

History 12th century

The castle was founded in 1101 by Robert de Belleme, the son of the French Earl, Roger de Montgomery, wh ...

while Wolryche was governor of the town. This association was not inherited by the next generation. Sir William Whitmore, 2nd Baronet

Sir William Whitmore, 2nd Baronet (6 April 1637 – 30 March 1699) was an English politician who sat in the House of Commons of England, House of Commons from 1661 to 1699.

Whitmore was the eldest son of Sir Thomas Whitmore, 1st Baronet of ...

had represented Bridgnorth in the House of Commons ever since 1661 and was to do so until his death in 1699: he regarded the borough seats as at his disposal. His brother, Sir Thomas Whitmore, had taken the second seat in a by-election in 1663, after a fierce contest, in which 182 new freemen were made in the six weeks before the poll. There seems to have been similar chicanery on this occasion, as Wolryche submitted a petition complaining of manipulation by the bailiff

A bailiff (from Middle English baillif, Old French ''baillis'', ''bail'' "custody") is a manager, overseer or custodian – a legal officer to whom some degree of authority or jurisdiction is given. Bailiffs are of various kinds and their offi ...

s after his defeat, but it was not reported.

The Whitmores were both broadly acceptable to the court and Thomas especially was reviled by Shaftesbury

Shaftesbury () is a town and civil parish in Dorset, England. It is situated on the A30 road, west of Salisbury, near the border with Wiltshire. It is the only significant hilltop settlement in Dorset, being built about above sea level on a ...

, who was working for the exclusion

Exclusion may refer to:

Legal or regulatory

* Exclusion zone, a geographic area in which some sanctioning authority prohibits specific activities

* Exclusion Crisis and Exclusion Bill, a 17th-century attempt to ensure a Protestant succession in En ...

of Charles II's Catholic brother, James, Duke of York

James VII and II (14 October 1633 16 September 1701) was King of England and King of Ireland as James II, and King of Scotland as James VII from the death of his elder brother, Charles II, on 6 February 1685. He was deposed in the Glorious Re ...

from succession to the throne. Wolryche stood explicitly for the "country party," opposed to the court.

MP for Much Wenlock

The short-livedHabeas Corpus Parliament

The Habeas Corpus Parliament, also known as the First Exclusion Parliament, was a short-lived English Parliament which assembled on 6 March 1679 (or 1678, Old Style) during the reign of Charles II of England, the third parliament of the King's re ...

of spring 1679 took the country further into political crisis and the king sought a way out of the impasse by calling for fresh elections in the summer. Wolryche had learnt from his earlier experience and decided to seek election elsewhere. Previously the Wolryche estates had been a key support to their parliamentary ambitions. Sir Thomas Wolryche had been MP in three parliaments for Much Wenlock

Much Wenlock is a market town and parish in Shropshire, England, situated on the A458 road between Shrewsbury and Bridgnorth. Nearby, to the northeast, is the Ironbridge Gorge, and the new town of Telford. The civil parish includes the villag ...

, a constituency in which the Wolryches held two considerable estates: the large manor of Hughley and the nearby estate of Presthope. John too chose to try his luck electorally at Much Wenlock. At the February elections, Sir George Weld had stood in for his son, John, who was tainted by his support for the now disgraced Earl of Danby

Earl of Danby was a title that was created twice in the Peerage of England. The first creation came in 1626 in favour of the soldier Henry Danvers, 1st Baron Danvers. He had already been created Baron Danvers, of Dauntsey in the County of Wiltsh ...

, and had been elected alongside the increasingly radical William Forester.Henning''Much Wenlock''

– Author: J. S. Crossette Now Wolryche stood on

slate

Slate is a fine-grained, foliated, homogeneous metamorphic rock derived from an original shale-type sedimentary rock composed of clay or volcanic ash through low-grade regional metamorphism. It is the finest grained foliated metamorphic rock. ...

with Forester, sharing electoral expenses, which totalled £124 9s. They used the same methods employed by their enemies, the Whitmores, having a large number of new burgesses enrolled. As a result, in an election held on 27 August, they defeated Weld and Sir Francis Lawley, 2nd Baronet

Sir Francis Lawley, 2nd Baronet (c. 1630 – 25 October 1696) was an English courtier and politician who sat in the House of Commons between 1659 and 1679.

Lawley was the son of Sir Thomas Lawley, 1st Baronet of Spoonhill, near Much Wenlock, Shr ...

. However, the parliament was prorogued and did not assemble until October of the following year.

In this Exclusion Bill Parliament

The Exclusion Bill Parliament was a Parliament of England during the reign of Charles II of England, named after the long saga of the Exclusion Bill. Summoned on 24 July 1679, but prorogued by the king so that it did not assemble until 21 Octob ...

, which lasted only three months, Wolryche was appointed to the important committee on elections and privileges, as well as a committee to investigate the Peyton affair. Sir Robert Peyton was a republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

and member of the Green Ribbon Club

The Green Ribbon Club was one of the earliest of the loosely combined associations which met from time to time in London taverns or coffeehouses for political purposes in the 17th century. The green ribbon was the badge of the Levellers in the Eng ...

, which had expelled him when he tried to reach a personal reconciliation with the Duke of York. Rash remarks he had made in the presence of Elizabeth Cellier

Elizabeth Cellier, commonly known as Mrs. Cellier or 'Popish Midwife' (c. 1668 – c. 1688), was a notable Catholic midwife in seventeenth-century England. She stood trial for treason in 1679 for her alleged part in the 'Meal-Tub Plot' against ...

then led to arrest for high treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

, release, accusations of involvement in the "Meal Tub Plot", and subsequent appearance at the bar of the House of Commons. He was expelled from the House.

Wolryche was re-elected for Much Wenlock on 18 February 1681 and represented it in the so-called Oxford Parliament, which sat for just a week. Again he was accompanied by Forester, who was now deeply involved with Shaftesbury and the embryonic Whig party.Henning''Forester, William (1655–1718), of Dothill Park, Salop.''

– Author: J. S. Crossette He was once again named a member of the elections and privileges committee.

The Rye House Plot

The failure of the opposition to secure an exclusion bill was followed by theRye House Plot

The Rye House Plot of 1683 was a plan to assassinate King Charles II of England and his brother (and heir to the throne) James, Duke of York. The royal party went from Westminster to Newmarket to see horse races and were expected to make the ...

, in which radical Whigs allegedly conspired to ambush the king and his brother. After the discovery of the plot in June 1683, Wolryche was one of the deputy lieutenants ordered to search for arms in Shropshire, despite his oppositional record. One of those implicated was Forester, who was found to have concealed a considerable quantity or arms and ammunition.

Death

Wolryche survived for only a few months into the reign of James II. He died of smallpox and was buried in St Andrew's church at Quatt on 17 June 1685. His heir was his eldest son Thomas. However, as his elder brother Sir Francis had no male heirs, Thomas succeeded to both the lands and the title on his death in 1688.Marriage and family

Around 1670 Wolryche married Mary Griffith, daughter ofMatthew Griffith

Matthew Griffith (1599? – 1665) was an English clergyman.

Early life and education

Griffith was born in London in or before 1599. He studied at Brasenose College, Oxford, later moving to Gloucester Hall, where he graduated with a Bachelor of A ...

(c.1599–1665). A militant and vituperative royalist, Griffith had been chaplain to Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

during the civil war and was made master of the Temple Church

The Temple Church is a Royal peculiar church in the City of London located between Fleet Street and the River Thames, built by the Knights Templar as their English headquarters. It was consecrated on 10 February 1185 by Patriarch Heraclius of J ...

in the reign of Charles II. Mary, according to her epitaph, was cultured and an accomplished singer and lute

A lute ( or ) is any plucked string instrument with a neck and a deep round back enclosing a hollow cavity, usually with a sound hole or opening in the body. It may be either fretted or unfretted.

More specifically, the term "lute" can ref ...

nist. She was about 33 years of age when she married Wolryche and was the widow of George Elphick, a Sussex landowner. She died in childbirth, aged 41, in 1678, and was commemorated by an impressive monument in Quatt parish church. She had already borne two sons, including Thomas, destined to become the third of the Wolryche baronets.

Family tree

Notes

References

* *George Edward Cokayne (1900)''Complete Baronetage, Volume II, 1625–1649''

Exeter: William Pollard. Accessed 10 June 2014 at Internet Archive. *C R J Currie (Editor), A P Baggs, G C Baugh, D C Cox, Jessie McFall, P A Stamper (1998).

''A History of the County of Shropshire: Volume 10 – Munslow Hundred (part), The Liberty and Borough of Wenlock''

Institute of Historical Research. Accessed 11 June 2014. *Reginald J. Fletcher (1901)

''The Pension Book of Gray's Inn 1569–1669''

Printed at the Chiswick press and published by order of the Masters of the bench. Accessed at Internet Archive, 10 June 2014. *Reginald J. Fletcher (1910)

''The Pension Book of Gray's Inn 1669–1800''

Printed at the Chiswick press and published by order of the Masters of the bench. Accessed at Internet Archive, 10 June 2014. * Joseph Foster (188

''The Register of Admissions to Gray's Inn 1521–1889''

Hansard. Accessed at Internet Archive, 10 June 2014. * *Oliver Garnett (2005). ''Dudmaston'', The National Trust, . * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Wolryche, John 1637 births 1685 deaths Alumni of Christ's College, Cambridge Members of Gray's Inn Lawyers from Shropshire English MPs 1680–1681 English MPs 1681 English landowners Younger sons of baronets Politicians from Shropshire